CHAPTER ONE

![]()

THE

STATE

OF

LUXURY

![]()

Theories and definitions for

superlative goods in an

ever-changing marketplace

RETHINKING LUXURY

Clear definitions of luxury are rare,

but most agree that you know

it when you see it. Luxury is as much

about the story and mystique

surrounding the product as it is about

the product itself. A high price and

scarcity are not the only components

of luxury. Consumers need to

be buying into a story or history.

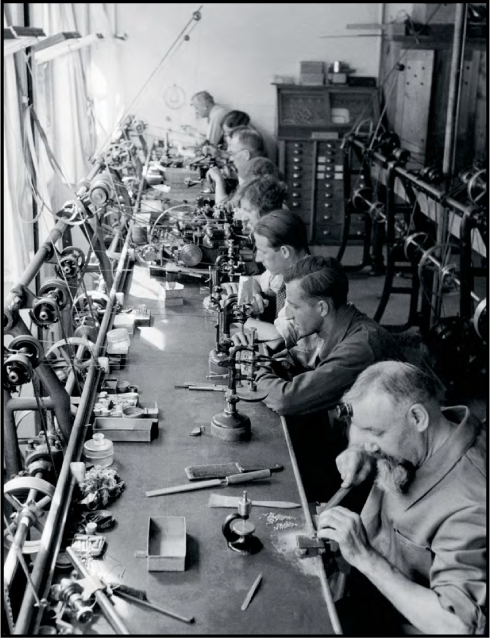

A watch can rely on mechanical

works developed over a century ago

that are impossible to replicate

with computers and lasers today.

Entire generations may have

fretted over the perfect stitching

and leather for a shoe.

Many define luxury as almost anything that is not essential. “Some people think that luxury is the opposite of poverty. It’s not. Luxury is the opposite of vulgarity,” as Coco Chanel famously remarked. She defined luxury as a coat with a silk or fur lining that only the owner knows about. Luxury consumers express themselves and show their self-image through their purchases. Someone who buys a single watch, a single super-luxury car or goes on a once-in-a-lifetime trip clearly knows what they want. They are displaying their ability to afford that product or service, and showing everyone that they have made a conscious selection.

Luxury is curated. Luxury is for connoisseurs. It is not only the price that makes a product luxurious. Its attributes do as well. Everything about a luxury product or service should cater to those who know why a luxury product is what it is, and how it came to be. Luxury products are exceptional from concept to realisation. They have superlative attributes. Aluminium or steel should not be used in place of titanium. An unthinking robot should not replace a trained, passionate craftsman. Luxury is not about cost, but is about demanding and owning something exceptional. Those attributes, to some degree, should contribute to the price.

Many raw materials carry hefty price tags because they are either rare or difficult to obtain. Many luxury items are not primarily about the most expensive materials. They are manufactured using exactly the right materials for the job: leather from a specific breed of animal, the ideal metal, a little-used oil. The materials are then assembled by artisans who are even more passionate about the items than their purchasers. These are craftsmen who often work with the same tools that have been used for decades. If they use more modern tools, they have good reason to do so and can explain why the new technology leads to a superior product.

This is what defines luxury and distinguishes it from premium or even mass-market brands. Luxury products are, at least in theory, the very best a product can possibly be. And that means they tend to take time and resources to produce, creating a scarcity of supply and exclusivity of ownership. Also, luxury contains many grey areas that obscure an objective definition. Luxury is subjective and relative, and involves a range of immaterial aspects. And that is exactly the way it should be. Luxury is, and always will be, deeply individual. The infographic on pages 18 and 19 helps illuminate the differences between premium and luxury goods.

LUXURY STORIES

Compelling stories, more than mere facts, convey a certain passion, a sensuality that brings the product to life for the buyer. Luxury products spark emotion, offering more than indulgence. These emotions are based on the soul of a product, its story. This is why there is a terrific story behind almost all luxury brands.

Patek Philippe watches are an excellent example. The company’s history goes back to 1839, when Antoine Norbert de Patek began making watches in Geneva. At the time, Patek was just doing what craftsmen in Geneva did best, which was making watches. The company’s story is therefore tied to more than just its own history. It is also tied to Geneva’s history and Switzerland’s past. Jean Adrien Philippe joined in 1851, and the company has made watches ever since. While ownership changed hands in the early 20th century, the importance of tradition was not lost. If you are a Patek Philippe owner, you already know all this. That is the point. You have not bought just a watch, you have also bought a tiny piece of Switzerland along with the technology and timeless design.

This does not mean luxury products cannot evolve or change. They can, and often do, embrace the future. But they also must remain faithful to the past. Indeed, luxury products should be shown to grow within the framework of their brand. Think of Hermès, which started selling its famous scarf after being known for decades only for leather goods. And after having excelled at writing instruments, Montblanc added watches and fashion accessories to its portfolio. Or Porsche, which constantly pushes the boundaries of how much technology a car can contain.

A SHORT HISTORY OF LUXURY

Luxury is present in the earliest manifestations of human culture and society. That’s because all humans have the same intrinsic needs and desires, and it is our desires that lead to luxury. The definition of luxury has evolved as our needs are satisfied by advancing technology, wealth and hygiene. But people have always wanted a little more than they had before. And they have always coveted rewards for victories. Luxury has always been controversial.

Luxury and affluence can be found in the objects buried in the earliest graves. The first indications are the number and size of items buried along with a body. Some graves are more complex than others from the same time period, and include more items. Graves began not only to include excessive numbers of items, but also individual markings. These markings link the body of the deceased to a specific group, creating a sense of uniqueness. A key component of luxury is this sense of exclusivity.

Luxury was present in the tombs and pyramids of Egypt and played a role in the epic struggle between Athens and the oligarchy of Sparta. A couple of hundred years later in Rome, politicians fretted over conspicuous consumption and passed laws designed to rein in public expressions of wealth.

Sometimes the evolution of seemingly unrelated aspects of life had a surprising impact on luxury. Martin Luther’s reformation of the Christian church stirred emotions throughout Europe. In the 16th century, that inspiration arrived in Geneva. Luxury was evident in the outward display of wealth by church leaders and politicians. These people believed God wanted them to surround themselves with luxury, since they were selected by God to be at the top. Geneva played a major role in this opulence since it had many skilled jewellers. However, John Calvin saw these trappings as unnecessary. God did not care about materialism, he argued. Resistance on the part of the wealthy ultimately led to revolution. In the French Revolution and in Switzerland, the people installed politicians more in keeping with Calvin’s reformist outlook. Consequently, much conspicuous consumption was outlawed and many jewellers were out of a job. It is now widely believed this is the reason Geneva’s jewellers, skilled with their hands but lacking an income, moved into watchmaking. Switzerland today is synonymous with high-end watchmaking and has a centuries-old tradition that reaches all the way back to Calvin’s Geneva.

The bandwidth of top-level products

Luxury and premium brands differ from each other in the way they are designed and manufactured, as well as in the values they reflect.

Source: Roland Berger Strategy Consultants

Later, the unbridled wealth brought on by the Industrial Revolution helped galvanise a sense of luxury. For the first time, aristocrats and merchants were no longer the only consumers able to afford luxury. Plant managers and inventors suddenly also found themselves with the budgets necessary to go luxury shopping, dramatically expanding the market for well-made products. And, as more people moved to the cities to work, Western class systems were simplified. Those at the top end of the middle classes were also able to afford some luxuries.

THE RISE OF LUXURY BRANDS

Early on, luxury was often defined by rare minerals or spices from abroad. The discovery of the New World was in part driven by an attempt to gain easier access to rare spices. But as culture and society matured during the Renaissance and in early modern Europe, so did the concept of luxury. The affluent increasingly wanted rare things, just as aristocrats and royalty had before them, and they wanted these things crafted into exquisite items by artisans – gowns, for example, or extravagant horse coaches. Because of the growing customer base that came with Industrial Revolution and urbanisation, these manufactured products became sought after by much larger groups. As a consequence, in the 20th century the luxury market as we now know it was formed.

Individual manufacturers had worked for monarchs and aristocrats in the past. But now, luxury customers were a market, and a market requires both larger quantities of products and orientation as to which products are suitable for distinction. That’s why luxury became brand-based, as defined by many of the companies and designers we still talk about today.

France’s Hermès is an excellent example of how a luxury company evolved based on its strengths. In the early 19th century, founder Thierry Hermès was astonished at the number of horses in Paris. Knowing that good equipment was vital for horse riding, he launched a workshop that crafted saddles and riding gear that were used by the rich and royalty alike. The company created its trademark scarf in the 20th century and added handbags, which would eventually be made famous by Grace Kelly. Adapting its knowledge of leather goods to make inroads into the luxury market, Hermès then became one of the bulwarks of the industry, allowing its products to evolve along with culture. Still, the horse in its trademark reminds everyone of its history. Even if one does not know the history, the Hermés trademark certainly conjures up images of 19th century gentry.

Today there is a variety of luxury companies with differing business models. Three big luxury conglomerates play the largest role in defining modern luxury: LVMH Group, Richemont and Kering (formerly PPR). They offer products from some of the best-known luxury brands, such as LVMH’s Louis Vuitton, Richemont’s Cartier and Kering’s Gucci. LVMH also owns Dom Pérignon Champagne and jeweller Bulgari. Richemont sells Alfred Dunhill products and Jaeger-LeCoultre watches. Kering has Girard-Perregaux watches and Bottega Veneta fashion. And though these conglomerates have been incorporating more and more brands over the years, there are still independent companies, such as Chanel, Ermenegildo Zegna or Brunello Cucinelli. Often they are family run. There are plenty of exceptional porcelain manufacturers, such as Meissen and the Porzellan Manufaktur Nymphenburg in Germany.

In the 1960s, luxury became a darling of the media. There were TV shows about mansions and private jets that showed how the other half lived. In the hedonistic 1980s, everyone yearned for luxury. It was the time of Reaganomics and movies such as Oliver Stone’s Wall Street – of unbridled fascination with status, brands and logos. Luxury became mainstream and familiar to the masses. But in the 1990s, values and society changed after a world economic crisis. Conspicuous consumption and logo-mania became frowned upon in many Western markets. So luxury evolved to be more about aesthetics and adding that certain something to a consumer’s life. Experiences, combined with a product’s history, now link the buyer to something greater than the product itself. Because luxury is more than ever associated with expressing one’s self, it also reflects divergent lifestyles. Luxury is varied and different for everyone. For proof, just look at the number of luxury brands. And it is difficult to categorise the brands beyond what they produce. Luxury is more than just fashion, watches and jewellery. Luxury covers broad categories, today including many layers of service and, for some, even spirituality. The most common luxury segments today are:

– Fashion and accessories

– Cosmetics and perfume

– Watches and jewellery

– Automobiles

– Wine, champagne and spirits

– Home furnishings

– Yachts

– First-class and private aviation

– Electronics

– Writing instruments

– Art

– Musical instruments

– Hotels

– Restaurants

– Food

We see four distinct business models by which luxury companies operate in these segments. The first is a brand that has its own personality and that makes consumers want to pay above and beyond the product’s materials or function. These products are seen as the gold standard of their categories: Montblanc pens, for example. In our second model, products are assembled by true master craftsmen using materials that command a price tag out of reach for most. Bugatti comes to mind. The third relies on investments in patents and technology or by closely following how a product is used. Here Leica cameras are a good example. In our fourth business model, we see companies tightly controlling distribution and requiring consumers to apply in advance to buy their products. Some customers have had to wait years for their Hermès Birkin bag. This way companies create exclusivity and maintain their brand’s image, enticing buyers into their often lavish stores for a complete buying experience.

THE LUXURY MARKET

Luxury is relatively immune to swings in economic fortune in comparison to other industries. In the past 15 years, the market for personal luxury goods has more than doubled in size. The market stalled following the stock market crash and the subsequent terrorism attack in New York in 2001, but it did not contract. After catching its breath, the luxury market continued to expand until 2008, when the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy threw global economies into a tailspin. It is little wonder this economic disaster hit the luxury market. It contracted in 2008 and 2009, but only to ricochet in 2010 with 13 per cent growth, and has continued to grow since then, emerging stronger than before the credit crisis. These figures are based on numbers gathered by a study published by the Altagamma Foundation and refer to the personal luxury market, which is essentially items that can be worn, from fashion to watches to perfume. That market is worth more than €200 billion now, but excludes key products such as cars, travel and wine. Folding in those items as well as home furnishings, yachts and food, the market balloons to more than €700 billion but still does not include aviation. And the overall market continues growing dynamically, even when regions such as Japan have problems.

Familial wealth allowed many previous luxury consumers to continue spending through the crisis and, as their portfolios recovered, to expand their outlays as economies also returned to health. Some major shifts are underway in global markets and they, too, helped contribute to the recovery. Fresh millionaires are minted daily in Asia. Economic and demographic shifts are also changing a once-staid luxury market. We discuss these changes in greater detail in chapter three. But suffice it to say, emerging economies are driving growth in spending among the wealthy.

The United States remains the world’s biggest luxury market. Among luxury’s established, mature markets, Japan, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland are the cornerstones. They are markets we all know. Of the BRIC countries, China and Russia are the ones to watch. Greater China is the second-largest luxury market and will increasingly steal the limelight. Brazil is home to shoppers quite willing to spend on luxury, but the market remains small compared to the segment leaders. India’s luxury market is certainly growing, but the country often has its own, unique definition of luxury. Indian customers are unusually fond of local brands, making marketing difficult for international players.

These markets are all set to develop very differently. America’s luxury market reflects its reputation as being dynamic and open, and it was the industry’s major growth leader in 2013. Europe continues to suffer from the same economic woes that have plagued it for nearly a decade, but with its rich history in luxury, Europe is a popular destination for Asian luxury travellers, and many European markets still have room for growth. Using a yardstick that measures luxury spending against gross domestic product, France and Italy are well above the saturation level, and the German luxury market is currently half of that. This suggests the size limits of a luxury market may also be cultural, not just economic.

It is not surprising that one of the fastest-growing regions for luxury is the Middle East. The region’s booming economies have required plenty of foreign assistance, and foreign tastes have come along with it. Coupled with increasing international travel, the luxury market in parts of the Middle East continues to expand. In just a few years, it will have doubled. Still, the Middle East is also suffering from political instability, adding a dose of volatility. Despite recent problems, Brazil will continue to lead the charge in South America where its luxury spending mirrors the growth of its economy. Although it is currently stagnating, Japan is Asia’s second-largest luxury market and should be treated as a mature, saturated market.

Luxury has come a long way since its earliest days where it ended in the graves of ancestors. It has evolved along with man and created its own place in our world. While globalisation is making that world smaller, it’s also creating new opportunities for luxury brands. This includes sharing formerly regional manufacturing traditions with the entire world, and opening new stores in previously unexplored areas. Europe has traditionally been the epicentre of the luxury world. But that epicentre is slowly moving. In the next chapters, we look more deeply into the evolution of the luxury market and especially at the consumers who define it.

THE HISTORICAL LOOK OF LUXURY

Defining luxury can be difficult. Many argue that they know it when they see it. Here we present a selection of historical items that we feel reflect our ideal of luxury.

1341 – 1323 BCE

Tutankhamun

Luxury has likely been around as long as man.

For historians and archaeologists, graves such as Tutankhamun’s offer clues about past extravagance.

1400

Ming vase

Luxury spending is shifting to Asia but the luxury market is nothing new to the region. This Ming vase dates to the 15th century and now sells for millions.

1435 – 1489

Hans Waldmann

Hans Waldmann, a war hero and Zurich mayor, fought against conspicuous displays of luxury but failed to act as a role model. His hypocrisy led to his execution by beheading on April 6, 1489.

This 1937 statue attempts to restore his reputation.

1512

The Sistine Chapel

The Catholic church has always been good at luxury. Not everyone could hire Michelangelo as interior decorator.

1600

Harpsichord

Only the wealthy could afford a handmade instrument as complex as the harpsichord. Many of those who composed for it were funded by royalty.

1837

Hermès saddle

Thierry Hermès began by making tack for Parisians in 1837.

His company still does.

TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Patek Philippe

Switzerland’s watchmaking culture arose from the country’s 15th-century obsession with eliminating outward signs of wealth.

Bored jewellers began to focus on tourbillons.

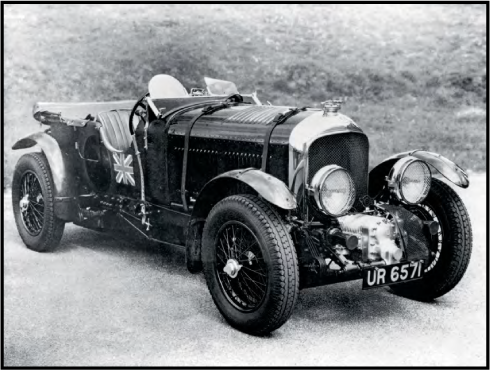

1929

Bentley

This Bentley “Birkin Blower” got its name from the compressor installed on its engine for speed.

It was one of the most advanced cars of its time and is now part of Ralph Lauren’s collection.

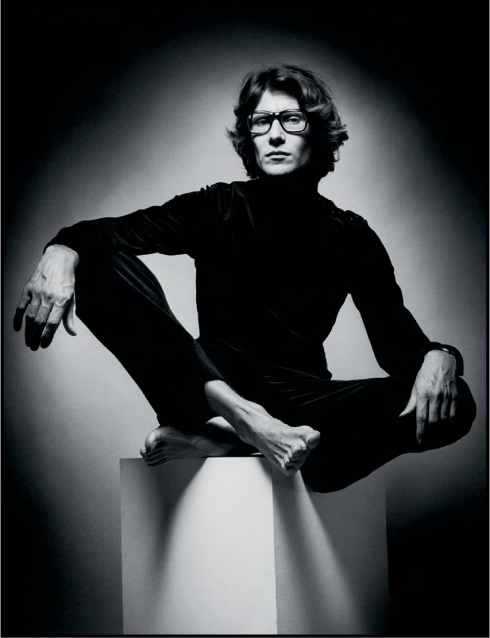

1936 – 2008

Yves Saint Laurent

The French fashion icon challenged social mores and advertising practices while giving a face to luxury in 1971.

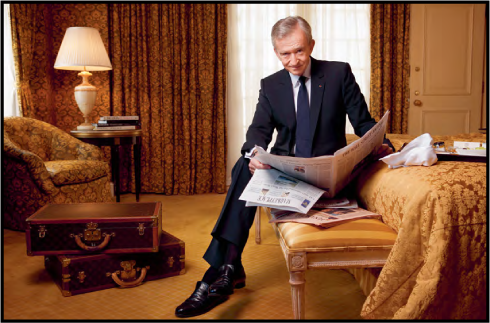

2013

Bernard Arnault

One of the faces of modern luxury is Bernard Arnault, the CEO who has crafted conglomerate LVMH as carefully as his artisans craft its products.

“The fragmentation of the luxury market presents considerable opportunities.”

An interview with Armando Branchini, executive director of Fondazione Altagamma, a foundation promoting Italian luxury brands.

We want to talk about recent developments in luxury marketing and cast a look into the near future. So the first question is: How have the Internet and digital communication changed the way luxury brands engage with their customers?

The breakthrough revolution is that two-way communication between luxury brands and customers is now possible.

Does this mean that the Internet reduces the mystery and exclusivity associated with luxury brands?

As a matter of fact, I believe that entering a traditional bricks-and-mortar store still gives customers the opportunity to experience a brand’s philosophy, its identity and its values. Any company offering products and services today of course has to be prepared to communicate properly what constitutes its value proposition. It’s difficult to have a value proposition if it’s unknown, if it isn’t properly communicated. I believe that myth rather than mystery is the appropriate term to use. Myth is the first of the symbolic values of a brand of a company. But you can’t sell a luxury product if it’s cloaked in mystery.

At the same time, far more people today are talking about luxury, say in the world of fashion blogging.

I believe that this is a sign of maturity and transparency, which is not a trade-off with authenticity. As luxury brands are promising values, it is mandatory for them to be in a position of maintaining such promises. The big challenge of the Internet and social media is the fact that it opens the doors for two-way communication, which has traditionally been in one direction only, from the company to the public. Today, tools such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and blogs make customers much more autonomous and independent. This means that they, the customers, play a greater role and can be seen as “prosumers”, in the sense that they are not just consumers, but that they are much more concerned and more knowing about products, product comparisons, price comparisons and so on. This is a much more mature market that is challenging the most conservative of the luxury brands. But that gives much more support and potential for growth to those companies that are the best performers in the use of digital tools.

Is it more difficult today to have loyal customers when your competitor is just one mouse click away?

Loyalty is a challenging issue in any case. This is true both for the bricks-and-mortar context as well as for the digital age.

Why have some luxury brands been reluctant to embrace the trend towards digital?

Initially, many companies were in a “wait and see” mode, concerned that the Internet might compromise some traditional luxury values, such as exclusivity and experience. In the last five years, however, two developments occurred. Technology, firstly, created a greater opportunity for the use of multimedia. Rather than simply using drawings or pictures, companies could now use music and movies, for example, to promote events and cultural initiatives. A second and more important factor that occurred in the real rather than in the digital world was a generational shift. The baby boomers, which for 40 years had been the main pillar of consumption for the luxury brands, now account for less than 50 per cent of the overall market. That means, in turn, that more than 50 per cent of customers belong to Generation X and Y. These are much younger customers who are accustomed to using digital tools.

One consequence is that there’s an increasing demand for authenticity and transparency. Would you say that one way for luxury brands to approach this is to become even better storytellers? Do you have to tell stories differently on the Internet?

The Internet has indeed generated new opportunities for storytelling. For example, customers were able via web stream to take part in the Fendi fashion show on the Great Wall of China. Another example: the Burberry fashion shows in Milan, which could also be streamed across the world. Storytelling is not based on technology, but on media. A proliferation of media, in other words, dramatically increases the opportunities for storytelling.

Talking about transparency and authenticity – are luxury brands under pressure today to deliver more sustainable products?

Absolutely. But for me this is unrelated to the Internet. Sustainability has never been a major issue for personal luxury goods. The only concerns in Europe were related to certain industrial phases of woollen fibre products, namely washing, and hide tanning. But from the 1970s, the European Commission issued very strict regulations controlling these activities. It is not correct to perceive of high-luxury brands as companies that endanger the environment.

But doesn’t this mean that luxury companies should do a better job at communicating their sustainable behaviour?

I believe that they should consider sustainability to be a given. If you are Gucci, you don’t compete with Louis Vuitton, Ferragamo or Chanel on the business of sustainability. You compete on different elements, such as quality or style identity. The final consumer makes his or her choice based on such elements.

How does the emergence of the Chinese and Asian economies change the luxury markets?

China and Asia will remain important pillars of the development of luxury consumption – around 7 per cent of global personal luxury products are purchased in China while about 15 per cent are purchased by Chinese outside of China, mainly in Europe and the United States. Due to the policies of frugality of the new Chinese president, we see some decline in demand in the domestic market, but final purchases of Chinese customers outside of China are as high as expected. Chinese demand for luxury products has increased significantly, particularly over about the last five years, as people are looking for status. But at the same time, an important part of the finer clientele, who are clever men and women, is truly sophisticated. As such, the learning curve, from “bling-bling” to sophistication, has been much shorter in China than it had been in Russia or even in Japan during the 1970s.

![]()

The big challenge of the Internet and social media is the fact that it opens the doors for two-way communication, from the company to the public.

![]()

Would you say that there is a general trend towards less conspicuous consumption and more real values?

There is a general trend, which is also happening in the more mature markets. An example would be the success of Bottega Veneta, a company that has never subscribed to “logomania”. Having long bought products with the Louis Vuitton or Gucci monogram on them, customers today have become more discerning, looking for sophistication and niche products. This is a structural element in the consumption of superior quality products and services.

Does the typical luxury customer still exist or are target groups becoming increasingly fragmented?

Of course they are increasingly becoming fragmented. Today we assume there are 14 to 16 main profiles of different luxury consumers. In 2012, 50 per cent of purchases in Milan were made by Italian people and the other half by tourists. In Paris and London, only 40 per cent of the purchases were made by locals and the rest by tourists.

In a nutshell, how should brands react to this increasing fragmentation?

If you are a good marketing manager, you are in a position to be able to deal with complexity. The fact that there are so many profiles presents a complication to your life, but it also presents considerable opportunities.

![]()

Having long bought products with the Louis Vuitton or Gucci monogram on them, customers today have become more discerning, looking for sophistication and niche products.

![]()

Luxury brands have always been great about creating experience around their products. Now we increasingly see experience becoming the product.

This is typical of the baby boomers. Rather than being interested in possession, they desire experience. This is strongly related to the curve of their existence: at a younger age, material possessions may play a more central role, while advanced age may encourage alternative preferences. It sometimes takes ages to realise that there is more to luxury than possessing cars or jewels.

Will this become more important in times of economic crisis and increasing pressure for sustainability?

Younger people are still interested in owning. Their time horizons are inclined to years and years of consumption. When the time horizon changes, with age, experience becomes more important.