CHAPTER THREE

![]()

EAST

IS

THE

NEW

WEST

![]()

Adapting a Eurocentric

luxury market to Asian dynamics

and demands

RETHINKING LUXURY

She is not just China’s first high-profile

first lady. A professional singer,

Peng Liyuan is collecting an impressive

number of firsts that go beyond her

public role and illustrate the newfound

confidence of the Asian powerhouse.

Peng began making headlines abroad

as she accompanied her husband,

Chinese president Xi Jinping, on his

first state trips abroad. What

observers noticed as she stepped off the

plane was that she was clothed

entirely by high-end Chinese designers.

Where the country’s elite had

previously looked westward

for inspiration, Peng announced the

arrival of Chinese designers

on the international luxury market.

The ascension of China as both a buying and selling power was a trend France’s Hermès decided to embrace in 2008 by launching a new luxury brand for the Chinese market. The brand would be produced by Chinese designers, aimed at Chinese luxury buyers and would have production based in China. Although the trend was clear in 2008, no one expected the Chinese market and its consumers to become such an important component of the global luxury market as quickly as it did. In 2012, the Chinese luxury market became the biggest in Asia, surpassing Japan, and the second largest in the world. Wealthy Chinese from Greater China (including Macau, Hong Kong and Taiwan) spent an estimated €27 billion on luxury items in that year, about 12 per cent of the total €212-billion market. The country is home only to about one-third of the Asian population, but it mints thousands of millionaires a year and its super-rich are steadily increasing in number. This creation of new money is driving the demand for luxury products among the Chinese, and the emergence of a new shopping class already has broad implications for the market. As noted in our opening chapter, the traditional logic in luxury is that the market is immune to swings in both taste and economies. Luxury, the logic goes, sets the agenda. Buyers follow. But that logic may now be outdated. The next Asian – or even Chinese – generation may have completely different tastes and demands than previous generations. There are already signs that they have different desires, and Hermès’ move seems to acknowledge that paradigm shift.

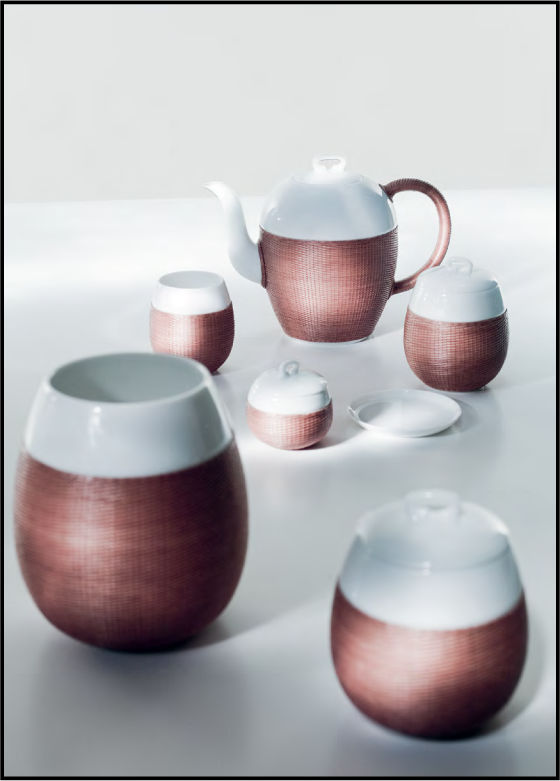

Hermès launched its new brand with a single store in Shanghai. The interior is covered in hexagonal white fabric that adds a soft, bright texture to the walls and highlights the store’s light, wood-grain furniture. The furnishings have no sharp edges and are often curved. The brand, Shang Xia, was created from the ground up by Shanghai designer Jiang Qiong Er and means “up-down” in Mandarin, an obvious reference to yin and yang. Designer Jiang has said she wants to recast old crafts in a new light to ensure subsequent generations appreciate the products. “I believe that the rise of the Chinese economy will foster craftsmanship and design, but it will take some patience,” Jiang says. “We believe this may become a crucial component in responding to global demographic changes and an economic shift in the luxury market: adapting to once-foreign Asian tastes and cultures as Asian consumers gain self-confidence and become comfortable in their role as trendsetters.”

SLEEPING DRAGON

Yet the future of the luxury market is Asian, whether it is selling products in the eastern continent or catering to Asian shoppers in markets such as the United States and Europe. In the past, Europe, with its centuries-old traditions, was always king. But that was yesterday’s world. Once-silent populations that are gaining a voice, combined with new flows of money, means luxury consumers are becoming more Asian, with cultural and familial roots often alien to traditional European makers of luxury products and services. Luxury consumers have traditionally longed for purchases that are steeped in European craftsmanship, but we believe that is changing. For now, Asian buyers are still sticking to traditional European luxury, but there is plenty of room for new brands or even the emergence of unexpected tastes – Korea’s ascension as a cultural bastion is one such surprise. For us, East is the new West.

When we talk about the East, in large part we are talking about China. The country’s rise from a sizeable and boisterous outpost of communism to a capitalist bulwark has created a gold rush for the luxury industry. The country took over the pole position much faster than even experts predicted. In 2005, Japan was still the Asian luxury leader and affluent Chinese were only spending one-tenth as much as their Japanese peers. Just seven years later, the Chinese began pulling away from Japanese luxury consumers. China’s turbo growth has sparked a rocket-propelled expansion of luxury spending. Although China lags Germany in the number of total high net worth individuals, it has more mid- and ultra-high net worth individuals, illustrating the country’s swift ascension. It’s not just dominating because it is the biggest fighter in the ring. China’s well-heeled consumers are unique. The reason is basic: the government still keeps a tight grip on free speech, but allows its citizens to spend the money flowing into the country nearly unfettered. This translates to consumers who are eager to express themselves through purchases, since they are allowed few other forms of expression. The Chinese are transitioning into a mature market and are moving away from the conspicuous consumption segment of luxury buying, putting them on the lookout for sophisticated brands. More detailed information on the size of Asia’s luxury markets is shown on the infographic on page 70, and we take a look at the leading position China’s consumers have taken in the infographic on page 73. We believe the studies show the Chinese are outpacing everyone in the world when it comes to how highly they value luxury. Affluent Chinese shoppers assign much more meaning to luxury purchases than their counterparts in the West. It is almost as if they are asserting a new identity, and money is the empowering factor. China’s luxury shoppers are also younger than their counterparts in the West. We discovered that about 45 per cent of the country’s luxury spending comes from people under 35, compared with 28 per cent in Western Europe.

A NEW INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

It is no secret that younger shoppers are more willing to part with their wealth than older, more conservative consumers. Age distribution is not the only differentiating factor for Chinese consumers. Luxury has become so important to the country’s nouveau riche that high-end spending has seeped down to income groups that can barely afford it. We also found that households with annual incomes equivalent to just under $40,000 are regularly buying luxury products. And, above them, upper-middle-class households now make up about 12 per cent of the country’s luxury purchases. The country is going through a huge transformation. “What they’re going through from the consumption perspective is like what we went through in the Industrial Revolution,” says Brian Buchwald, CEO of the Bomoda media venture targeting affluent Chinese fashion consumers.

Since Chinese consumers are so aware of what those around them are aware of, non-traditional luxury brands have a challenging time. Chinese consumers prefer to buy brands others are talking about – or have told them about. The top three luxury fashion brands for the Chinese are Chanel, Louis Vuitton and Gucci. The Chinese are also very cautious shoppers. This is why having a strong presence in the country is vital. Local stores or events allow hesitant buyers the opportunity to see and feel potential purchases before taking an exclusive item home. Initial purchases of a specific brand are almost always done in China, but shopping abroad is also on the increase. Luxury brands are already doing an excellent job of responding. Heavyweights such as Gucci and Hermès have expanded their networks of Chinese stores into the double digits, having had just a handful in the past. We address the importance of bricks-and-mortar retail for luxury in chapter six.

China is a growing force in luxury consumption

The luxury market in Greater China, including Macau, Hong Kong and Taiwan, has already surpassed Japan.

Asian luxury goods market, figures from 2012, estimate in billions of euros

Source: Altagamma Foundation, Worldwide Luxury Markets Monitor, 2013

Once away from home, Chinese shoppers are more prone to acquisitions, with good reason. High customs duties raise the price of luxury goods at domestic stores. When looking at China, companies should assume that customs charges will add about 30 per cent to the cost of goods there – but a number of factors can actually boost that disparity to as much as 70 per cent. For small accessories and incidentals, those fees do not mean much to the rich. However, when that fee is added to the bill for a leather coat, watch or car, it can put it out of reach or desirability. Chinese consumers know that opting to buy elsewhere can even pay for itself. They would often rather spend that 30 per cent on an airfare and a hotel in Paris. The Chinese Ministry of Commerce knows that customs duties are scaring away consumers, and several years ago debated drastic reductions. However, officials worried that changing the fees could be seen as favouring the rich, leading to inaction. Although the government cut tariffs on some imports, such as powdered milk in 2012, it’s still collecting high fees on luxury items.

The high cost of shopping at home has created some differences in where the country’s luxury shoppers spend their money. The majority of them still shop in mainland China, despite the tariffs. Only a small minority entirely eschews the domestic market. However, about half of Chinese luxury customers shop abroad and at home. This makes them a powerful force. Most of this “shopping abroad” still takes place in Hong Kong and Macau, but Europe is a shopping destination that is on the radar of a rapidly increasing number of Chinese luxury customers.

CHINESE LUXURY IS GLOBAL LUXURY

Although technically the Chinese still spend most of their luxury cash within China, interest is continually growing in shopping in Europe as well as in the United States, which remains the world’s number one luxury market. Tourist shoppers are a demographic that should not be ignored when trying to attract consumer attention in Europe. Why? Some analysts believe Italy’s Prada got half of its European sales (excluding Italy) from Chinese tourists in 2012. That buying boost helped increase the fashion house’s 2012 European sales by one-third. Luxury companies must also consider nearby Asian markets to lure in Chinese shoppers. Places such as Singapore and South Korea have special sway among affluent Chinese consumers.

Consider the popularity of the song Gangnam Style and its accompanying video – many young Chinese consider Psy and his K-Pop ilk much hipper than their once-dominant Japanese counterparts. Indeed, part of what is attractive to young people has always been finding trends from somewhere previously ignored by their parents. The intrusion of South Korean culture into China has meant a blessing for the South Korean tourist industry, with the number of visits growing strongly each year. That is partly the result of expanding wealth but must also be related to Chinese interest in South Korean culture.

Greater China – including Macau, Hong Kong and Taiwan – is a vital market for foreign luxury companies. While traditional luxury brands have succeeded by simply showing up with retail stores and heavy online presences, many, like Hermès, are trying unique approaches to skim the buoyant Chinese market even more. Hermès’ rival Kering has taken an even more direct approach to expansion in the Chinese market: buying customers. In late 2012, the company acquired a majority of local jeweller Qeelin. It did not say how much it paid but maintains the company is profitable and well-positioned with 14 stores in China. Its jewellery goes for between HK$20,000 (€2,000) and HK$300,000 (€30,000) and is even available in Europe and Japan. In our opinion, acquisitions can be an excellent means of getting into China. Local brands such as watchmakers Shanghai Watch or Seagull have yet to realise their full potential and can benefit from the unique perspective and expertise of a larger company.

The unbridled growth of the Chinese luxury market has not gone unnoticed by the Chinese Communist Party. After a leadership change in 2012, the party cracked down on spending by government officials, leading to a drop in spending, both on luxury gifts and on services for administrators used to a lavish, state-sponsored lifestyle. While the anti-corruption and anti-conspicuous consumption campaign had a direct effect on luxury revenue, there were hints that the party might in the future do more to influence the luxury sector.

Luxury consumers are becoming increasingly Asian

Chinese consumers now make up one-quarter of all the luxury customers in the world. Almost one-quarter of luxury consumers are European.

* Rest of the world

Source: Altagamma Foundation Luxury Goods Worldwide Market Study, 2012

Officials have said they are concerned about the rift between the country’s rich and poor (or even super-rich and super-poor) and, in February 2013, banned advertisements of ostentatious goods and services on the country’s state television and radio stations. The ads, it said, “publicised incorrect values and helped create a bad social ethos.” Since this is the second time in two years the party has imposed such a prohibition, the direction the country’s leadership is taking should not be ignored. Companies should consider both the party’s moves against luxury brands and the previously mentioned moves to reconsider tolls because they are a sort of yin and yang. While there is political concern about the rift between the rich and the poor, the party has also made changes that favour commerce.

FROM ONLY CHILD TO STEPCHILD: JAPAN

After being on the centre stage of the global luxury segment for decades, Japan and Japanese buyers have fallen from the limelight in just a matter of years. The Japanese luxury market has a great history. It began blossoming in the 1970s as the rich went abroad and brought home hand-made treasures exuding quality and tradition. However, the exuberance that once made the country an emerging luxury market has now created a saturated one. Worse yet, like Japanese wealth, that market is deteriorating. Currently the world’s third largest economy, Japan may slip to fourth by 2050, according to predictions by HSBC. While China is on an upswing, Japan appears to be at least stalling. However, even though the country has just a fraction of the population of China, it still has plenty of money, and money being spent. The spotlight may no longer be on the country, but the Japanese luxury market is only slightly behind China.

Luxury brands have not – and should not – give up on Japan. Burberry, along with Prada and Hermès, has twice as many stores in Japan as it does in, for example, the United States. Japanese customers account for about 13 per cent of Louis Vuitton fashion and leather goods sales, and 40 per cent of well-heeled Japanese own a Vuitton product. The Japanese market is also at the most advanced of the four basic stages of luxury evolution. It is in the final, meaningful stage that is defined by shoppers who live within and are comfortable navigating the luxury lifestyle and markets. Luxury products in Japan are part of daily life. In Japan, there is no more discovery or exuberance. Affluent Japanese consumers have been spending big on products and services for as long as they remember and they know what they like – and what they do not like. In this stage, there is very little room for convincing a buyer to try something new or different. To be sure, consumers at this stage still spend on luxury – and they spend plenty – but they are the ones in the driver’s seat, deciding on which direction they want to take.

Satisfied that they know what they are buying and what they want, Japanese, like many modern luxury shoppers, are now more concerned with the experience of shopping – or buying experiences in the form of services. This perhaps explains the high numbers of retail stores in Japan and the sheer size of its market. Retail can create a unique experience for consumers buying shoes, watches or even cars. Mere spending is not enough of a thrill anymore. Now a V-12 car has to be delivered at a race track and a haute couture dress should come directly from the designer’s atelier after the buyer sits front row at a fashion show – all expenses covered by the brand. We talk more about the importance of delivering an experience in chapter seven. Many brands have already embraced these consumers. Gucci built not just a flagship store, but a flagship building in Ginza that features a cinema for restored Italian classics. Cosmetics company Shiseido created the Shiseido Parlour, with an art gallery, restaurant and tea room. Other brands opt for special VIP sales or one-off events for loyal customers to emphasise an air of exclusivity, or create a sense that buyers are brand insiders helping to guide the trend. However, the move to offer more in Japan has not always paid off. Versace abandoned the market in 2009 after an expansion failed, but it’s back now.

Then there is the evolution of Japanese consumers themselves. The next generation is very different than their predecessors, in part because of the confidence created by generations of wealth. Where their parents demanded proven quality, robust materials and a history of craftsmanship, Japan’s modern luxury consumers are not afraid to mix and match between high-end products and their more mainstream, lower-cost brethren. If rich Japanese people are more concerned with what they think of a product than how they are perceived while using it, then it is likely that they would pass that sense, at least partially, on to their children. Today in Japan, being an informed buyer is knowing what is worth spending money on and where frugality highlights your buying intelligence. Rich young Japanese shoppers mix trips to Lamborghini, Prada and Hermès with stops at Uniqlo and luxury outlets.

Gucci Ginza Café

Gucci’s flagship store in Tokyo’s Ginza District is much more than just a shop: the integrated brand experience includes a gallery and a Gucci café which serves cake branded with the company’s logo.

We see brand diversification as a good example of how to react to a saturated luxury market. Confident in its position at the top of the luxury ladder in Japan, Burberry created Japan-only brands to appeal even more to fickle youth with less money in their pockets than their parents. Burberry Black Label and Blue Label offer clothes and accessories at a discount to their parent brand – as much as 90 per cent on some items, such as handbags. In the eyes of some, these items then no longer qualify as luxury, but if the products can be produced at a significant discount without compromising quality, it is money Burberry would not otherwise be getting from the selective buyers. Arguments can be made about diluting brands and images. However, it is a trick Lanvin is also trying with Lanvin en Bleu and Lanvin Collection. These two Japan-only brands are positioned lower and cheaper, hoping to keep some of the money away from Uniqlo. Nor does this stop at individual brands. Outlet malls are a common sight in Japan, with 39 throughout the country and the biggest debuting in 2012, near Tokyo in Kisarazu. Who is there? The list of who is not may be shorter.

THE BROADBAND SUPERPOWER: SOUTH KOREA

Another Asian luxury market we note is South Korea, which has posted strong growth for nearly a decade, though its market remains about one-third the size of Greater China’s. The country’s blossoming cultural influence is the first reason to pay attention to South Korea. The country has not just made it onto the radar of China’s wealthy, it has made it onto the radar of almost everyone. Sure, that is in part thanks to the fascinating pop star Psy. But it is also because the country’s mass-market consumer items are household names alongside other Asian competitors. Brands such as Samsung, LG and Hyundai have piqued the curiosity of international consumers. Even tourism is booming. South Korea is equally famous for its upmarket luxury multi-label stores, where shoppers find suits by Armani, shoes by Salvatore Ferragamo and Gucci sunglasses in one large store or mall. Luxury Hall West and Luxury Hall East, both located in Seoul’s affluent Apgujeong-dong district, are the most notable examples for this popular concept.

South Korea is also enjoying an economic renaissance, with ambitious companies hoping to secure its position as an electronics powerhouse. The country is also attractive to luxury marketers because of its willingness to embrace the Internet. Luxury companies can reach Korean consumers without leaving home by establishing a Korean web presence that remains true to their brand image and level of opulence. And Koreans love luxury. One reason is because they want to reward themselves for working exceptionally long hours – about 5 per cent of an affluent consumer’s budget is spent on luxury items, one percentage point higher than their Japanese peers. “There is a remarkable focus on supplying branded, individualistic clothing products, rather than the ultra-cheap basics you might expect from their equivalents in the West. Koreans shop online at eBay’s Gmarket for basics and go to the stores for their bling,” says Christian Oliver, a Financial Times columnist in Seoul.

Asia and Asian consumers are the new look of luxury. Their pocketbooks and cultures will shape the future of affluent buying. Their tastes currently mirror the traditional tastes and brands of luxury. After all, luxury is steeped in history. It is a way to buy into a past that was more careful and potentially more exclusive. Asia may be changing that. The emergence of China as a super shopping power must mean change – it is a different culture with a different background and an odd political structure that allows capitalism within communism. We aren’t just saying East is the new West because it has a nice ring to it.

HOW TO…

Four strategies for successful

e-commerce in China

It seems obvious that the world’s most rapidly growing market for luxury products would also be an ideal playing field for e-commerce. However, as some overly enthusiastic entrepreneurs have discovered, it is just as easy to miscalculate the needs of this powerful new audience. Here are four pointers to help companies make it over the finish line.

1. Foster relationships with brands

As we have established in this chapter, Chinese customers largely prefer European-made luxury goods with a long history of excellence and are intensely loyal to their favourite brands. By that token, they will also be more likely to give credit to brands that have made their reputation in the West. In fact, trust is one of the deciding factors in making online purchases. Or rather, distrust. Research into the buying habits of luxury consumers has shown that while close to two-fifths of these shoppers in China already use the Internet to gain information about products, only 8 per cent of them go online to spend money. That reluctance is rooted in the fact that China is still thought of as a hotbed for fakes – even by the Chinese. Paying for a luxury item online, only to receive a counterfeited product in the mail, has discouraged people from making purchases.

2. Make service a priority

Getting the product to the customer quickly and, better yet, free of charge, is a good start. But the service should not end there. Apply the same rigour to after-delivery care. Thecorner.cn has a call centre to deal with anything from availability of product to returns. Additionally, a sound and easy-to-navigate payment process is vital for catering to customers’ convenience. In the grand scheme of things, it might not seem like a big deal for a company to implement these structures, but it can make a huge difference in determining their success. It is also vital to present a website in Chinese that matches Chinese tastes. Customers there expect websites to be flashy and complex – almost gaudy by Western standards. The small details make the difference.

3. Start now

It was only in 2010 that Emporio Armani opened for e-commerce in China, the first Western fashion brand to do so, with a small band of others following suit and companies exploring options for multi-brand e-commerce. But since then the number of people who make at least one luxury purchase per year has quadrupled, and total luxury spending has gone up 50 per cent. Investors are picking up on this shifting attitude. In February 2013, a consortium led by Saudi prince Alwaleed bin Talal invested $400 million in homegrown Chinese startup 360buy.com. The advantage for first-movers that overcomes their hesitation at putting up the money lies not just in gaining ground on competitors, but in having time to work on and perfect the business model, making it run smoothly before the rest of the field can catch up. Because here is another number: the Chinese online market is projected to grow by more than six times by 2015.

4. Use local social media networks

Social media is more important in China than in most other markets. The country often operates according to “guanxi”, a Chinese word for personal network. The Chinese rely on their own personal network to make buying decisions, and value highly the opinions of those closest to them. Since social networks can be seen as a digital extension of guanxi, they should be an integral part of every marketing project. Forget the usual suspects here, as the country has its own social networks, which vary depending on age. The largest – and youngest – is Qzone, a favourite among older children and teens. RenRen appeals to those in their twenties, while Sina Weibo reaches people firmly in their careers. Marketers should focus on the social media site that fits them best – and do everything in Chinese.

“We’re not conquering, we’re offering.”

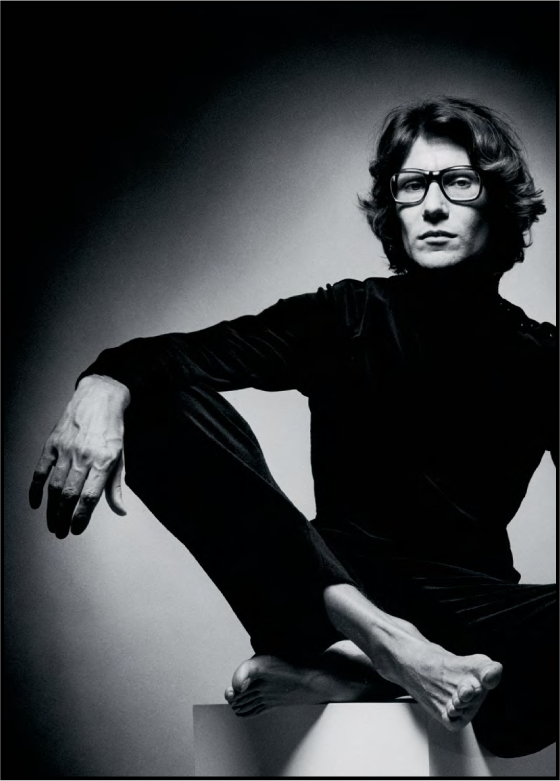

An interview with Jiang Qiong Er, CEO of Shang Xia, the Chinese luxury brand of Hermès, which now also has a Paris boutique.

Shang Xia is considered to be China’s first domestic luxury brand. Why aren’t there many others?

Shang Xia is walking on a new path. We actually don’t position ourselves as a luxury brand, even though people often say that we are. Shang Xia is a brand of 21st-century fine living, where contemporary design meets Chinese heritage crafts. It’s new and it will need quite a long time to develop. We hope there will be more companions walking the same path as we are. That way our Chinese inheritance could be continued in a healthy and substantial way.

How did it all start?

I was introduced to traditional Chinese art when I was little, and had the opportunity to explore it in different fields of art. As I understood more and more about Chinese craftsmanship and the deft skills of craftsmen over the years, I was truly touched by the power and beauty of their work. Over time, I developed a dream to share this appreciation with the world. In 2006, I told Patrick Thomas, CEO of Hermès, and Pierre-Alexis Dumas, artistic director of Hermès, about my vision and we decided to create this new baby called Shang Xia. It took us a few years to build the team, searching for the finest craftsmen throughout China, and interpret it with contemporary design. In 2009 Shang Xia was officially founded in Shanghai, with its first worldwide boutique opening in Beijing in September 2010.

Right now most Chinese luxury customers seem to be interested in European brands, products and heritage. Will they start embracing their own tradition more?

We definitely see more and more Chinese customers at Shang Xia. As a matter of fact, our Beijing boutique caters to up to 70 per cent Chinese customers, embracing their heritage and culture. I believe that emotion is the key to one’s art of living. The finest touch of craftsmanship, innovative design and contemporary lifestyle are all linked by a personal touch. Without a true emotional understanding this link is disconnected. The inheritance of our culture and fine art will lead Chinese customers to come along the way with us as they’re searching to fulfil their emotional demands.

![]()

I believe that emotion is the key to one’s art of living. The finest touch of craftsmanship, innovative design and contemporary lifestyle are all linked by a personal touch.

![]()

Could the tables even be turned soon and Chinese and other Asian luxury brands start conquering Europe?

I wouldn’t use the word “conquer”. I would call it an offering. The Western world has a long history of appreciating culture and art from the East. So the revival of contemporary Chinese craftsmanship and design will also be shared and appreciated by international citizens, without doubt. The question is not about turning tables. The question is about time. Unfortunately, in the past 100 years China has faded from the cultural continuum. I believe that the rise of the Chinese economy will foster craftsmanship and design, but it will take some patience. When we opened our first overseas boutique in Paris in September 2013, we didn’t want to do it big, but we wanted to do it well.

Should more European luxury brands form collaborations such as the one between you and Hermès? If so, what’s the secret to a successful one?

I can only share what Shang Xia is keen to achieve. We are not another branch of Hermès, but we share the same value of pursuing the best quality. And we produce almost all of our objects in China, such as finely wrought homewares and elegant clothes, including sculptural dresses made from hand-felted cashmere in a centuries-old process with its typical attention to detail.

Flagship Bejing boutique

Shang Xia works to create a modern Chinese aesthetic in both its products and its stores.

Local craftsmen

The company employs native artisans to create superlative products based on Chinese traditions but using fresh designs.

![]()

Nowadays, more people want something different. In the first 30 years of economic development, the Chinese did not have the opportunity to pursue these desires.

![]()

The Chinese luxury market comes with its own unique challenges. Many are concerned about the rift between the country’s rich and poor. Are you seeing a political or cultural backlash against luxury spending, especially for Western brands?

For a while, Western luxury brands have been making inroads with the most fashion forward of the country’s sizable population that has an appetite for luxury. However, the perception is slowly changing as many homegrown, high-end brands are being developed, often with a traditional bent and sophisticated designs. People used to desire anything from a luxury brand. Nowadays, more people want something different. In the first 30 years of economic development, the Chinese did not have the opportunity to pursue this desire. It was about fulfilling basic needs, not going hungry, not being cold. Now, we’ve started to return to our cultural roots. In the last five years, people have started to realise the importance of creativity and quality in China.