4Television Text Types

Abstract: Research on language and communication in television is usually based on classifications of different text types which can differ notably from each other depending on the research focus and cultural context. Years ago, Jost (1997) underlined the fact that the question of text types had not as yet been resolved, and this is still true today since the progression of media communication strategies has even accelerated. In view of the vast number of research fields and approaches, the scope of this article is not to provide an exhaustive inventory of television text types. Instead, I shall summarize the most important approaches in order to identify factors, underlying assumptions and research perspectives leading to the different categorizations. Classification criteria and recent changes such as the internal heterogeneity of television text types will be discussed. Furthermore, special attention will be paid to their historical nature and to the dynamic relationship between text types and language use. The article will focus on those aspects of television text types that might be particularly relevant for French language use in this medium.

Keywords: classification criteria, fictional and non-fictional worlds, genres, heterogeneity of text types, historical nature, language and communication in television, media communication strategies, newscasts, production, reception, television text types, text types and language use

1Introduction

It is generally accepted that there is no such thing as a special language which one might refer to as “television language”, however the language usage we encounter when we switch on the television varies greatly depending on the program we choose (cf. Reinke 2004; Schmitz 2004). It is thus important to take a closer look at television text types as an extra-linguistic factor influencing the way language is used in this particular medium.

Anyone who is expecting to find, in this article, an exhaustive inventory of television text types, including a complete list of criteria allowing one to differentiate among them as well as a description of their respective characteristics will be disappointed. Indeed, one could almost say that there are as many television text types as scholars studying this phenomenon, giving rise to distinct classifications depending on the scholar’s special background and respective research interests.32 In fact, the question of television text types and genres has been investigated by scholars coming from different fields of study such as film, communication, philosophy, sociology, linguistics, etc. Furthermore, these terms are used in various social circumstances with different meanings: the film industry relies on genres for self-definition or scheduling, audiences use the same term to organize fan-based events or in everyday conversations, academics use it to circumscribe research projects, etc. (cf. Mittell 2001, 3). It would therefore be impossible to provide a complete overview of the numerous typologies and theoretical approaches to television text types. I shall nevertheless attempt to bring some degree of order to the huge amount of what has so far been said about television text types and highlight what constitute, in my opinion, the main aspects that should concern the readers of this manual – undergraduate, graduate and doctoral students as well as academic teaching staff of the Romance languages and philology who are familiarizing themselves for the first time with this field. My choices are of course influenced by my own scientific background as a German and French Canadian romanist/sociolinguist who is interested in language use in television. I shall thus focus on those aspects of television text types that might be relevant for French language use in this medium. However, as television is a striking illustration of the penetration of American culture in Europe where successful American formats have been adopted everywhere (cf. Bourdon 2001), the article will focus on general transnational characteristics valid for French television text types rather than unique national particularities.33

2Discriminating between similar concepts

The first problem one encounters when studying television text types is that they are not always called just that: one comes across terms such as text type, genre and format in English, type de texte, genre and format in French and Textsorte, Genre, Gattung and Format in German, to mention only the most common ones. They all seem to signify more or less the same thing and are often freely interchanged.34 Sometimes one of the terms is even used to define another:

“The word genre comes from the French (and originally Latin) word for ‘kind’ or ‘class’. The term is widely used in rhetoric, literary theory, media theory, and more recently linguistics, to refer to a distinctive type of ‘text’” (Chandler 1997, 1).

“Annonçons donc de prime abord que, pour nous, un genre est un type de texte […]” (Charaudeau 1997a, 84).35

More broadly speaking, it is all about elaborating a typology that would allow us to categorize a very complex reality of texts into groups on the basis of shared characteristics that differentiate them from others.

Entitling this chapter text types and not genres or formats reflects a certain theoretical position, that is to say a text-based linguistic view that extends the concept of text to all kinds of language production, be it written or spoken, and also takes into account the importance of screen images in constructing meaning (cf. Lüger/Lenk 2008, 12; Burger 2000, 615). Therefore, I shall use the term text in its broader sense to define all kinds of texts transmitted via television. However, I shall use text types and genre as synonyms depending on the more common usage within a particular source.

Even if genre, text type, format and Gattung are often used as synonyms, there appear to be some distinctions. There is a large consensus that the concept of genre has its origins in the Aristotelian Greco-Roman rhetorics and the subsequent theory of literary genres. The study of literary genres such as poetry, prose and drama, and moreover of numerous subgenres, are still part of school curricula all over the world. Later, genre was applied to other art forms as well as to radio and then television, continually extending its meaning and adapting to the needs of the new media. Such changes have accelerated over the last decades. Schaeffer (1986) uses the term categories généalogiques [‘genealogical categories’] to describe this tradition of fitting new creations into historical categories. Adopting the notion of genre to television represents a certain continuity with the tradition of literary genres, although television and literary genres are not identical.36 The closest similarities can be found within fictional genres. This might explain why the notion of genre sometimes seems to be reserved for film genres (e. g., western, comedy, science-fiction), whereas text types more often refer to non-fictional television texts (e. g., news, reports, magazines).37 The latter distinction might have been established in analogy to the more common usage of the term genre for literary texts as opposed to text type for texts in everyday communication (cf. Dammann 2000, 547). From a linguistic point of view, these text types could also be studied using text linguistic and interactional approaches. These would be based on the distinction between discourse genres as social construction in context as opposed to text types as a mode of organization of a text without contextual considerations (cf. Bakhtine 1984; Adam 1992). Accordingly, Jolicoeur (2014) uses text types when referring to the televisual product and genre when referring to a social norm across all stages of production, programming, and reception and whose interpretation ultimately leads to a standardization of text types.

Sometimes, genre and format are also not adequately discriminated one from the other (cf. Türschmann/Wagner 2011, 8; Keane/Fung/Moran 2007, 63). Hickethier (2002, 90) believes that the notion of genre is, more and more, being replaced by the notion of format, which refers rather to the specific form of a program and stems from the commercialization and internationalization of the television market. It describes a concept of program that has been imported and is protected by copyright and licenses. The format is purchased by a television channel and adapted to different national audiences, these adaptations being limited by a contract and, compared to genres, is less susceptible to alteration (cf. Mikos 2008, 268). The most famous example is the quiz show “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” that has been imported from the USA and copied in 67 territories around the world employing the same form (cf. Keane/Fung/Moran 2007, 101). Whereas the presenter, the candidates and the questions vary from one country to another, the basic rules and the spatial arrangements are the same (cf. Mikos 2008, 269). As a purely economically-motivated phenomenon that can nevertheless be assigned to a genre, this article will not further discuss the particularities of formats, but will deal solely with genres and text types.

Some German authors oppose Genre to Gattungen, even though they are commonly used as synonyms (cf. Dammann 2000, 548; Türschmann/Wagner 2011, 8). Nevertheless, Genre is sometimes considered as a subcategory of Gattung (cf. Mikos 2008, 263; Hickethier 2002, 63). Genres are defined on the basis of content, whereas Gattung is defined on the basis of the representational mode (e. g., motion picture, documentary film) and its utilization (e. g., advertising film, educational film; cf. Hickethier 2002, 63). A good example would be the crime genre that is characterized by a specific storyline based on a crime and the solving of it. This genre is found in different Filmgattungen (e. g., motion picture, animated movie); furthermore, it can be found in other media (e. g., in novels, as radio drama; cf. Hickethier 2002, 63). For the purpose of this article, the distinction between Genre and Gattung is not relevant as the English and French language do not make such a distinction.

With regard to television, genres and text types enable producers, the audience as well as researchers to classify the elements of a complex program within a precise category. But “practitioners and the general public make their own labels (de facto genres) quite apart from those of academic theorists” (Chandler 1997, 2). Even among scholars, the question of text types/genres has not yet been resolved. Within the French context, a thematic issue of the journal Réseaux (№ 81, 1997) proposed some theoretical approaches that are still valid (cf. Jost 1997; Charaudeau 1997a). Identifying a specific genre or text type is a difficult task,38 even more so because of the use of different classification criteria, their ongoing changes and their internal heterogeneity. For these reasons, the following sections will focus on the latter aspects.

3Approaches to television text types: A trend towards functional approaches

3.1General remarks – Overlapping labels

There is often considerable theoretical disagreement regarding the definition of specific genres (cf. Chandler 1997, 1). This is due to the fact that different approaches deal with the same phenomenon. In the following section, I will summarize a number of different approaches, but will avoid labeling or naming them as this would create a somewhat artificial classification. In actual fact, we do not deal with established or recognized schools of thought, but rather with different, sometimes individual attempts to categorize television genres or text types. Schmidt (2003, 165) distinguishes two main approaches in the history of genre theory: typological and functional (cf. also Mittell 2001, 4s.). According to Schmidt, typological approaches endeavor to deliver exact definitions of each genre and to integrate them into a hierarchical system of supra-, sub- and neighboring genres. They determine genres on the basis of characteristics of what is offered by the media, but exclude the relationship between media and public. Functional approaches, on the contrary, try not to define what genres are, but how they function.

Another problem is that typological approaches do not always exclude the functioning of genres, but analyze them more in relation to their textual characteristics. On the other hand, some functional approaches might also lead to a typology of genres. Of course, one could seek to categorize the approaches in terms of their dominant characteristics, but the same label is sometimes used to describe different approaches, or different labels are used to describe similar approaches. In this respect, some of the approaches, as a common denominator, focus on what is offered by the producers and how it is interpreted by the audience. They could be called “functional” or “pragmatic” since they refer to the actual use of genres and to the construction of meaning in a specific context, but they could also be called “constructivist” to give more weight to the latter aspect. Finally, Schmidt (2003, 165) himself recognizes that functional approaches offer many possibilities for investigating how a genre operates in the public arena.

3.2Text types from the viewpoint of production and reception

Many classifications of television text types and genres are based on patterns and conventions of content and form that guide the producers and create expectations on the part of the audience, thus influencing reception (cf. Lochard/Soulange 1998, 91). However, such categorizations are often ambiguous, as some TV productions might correspond to one genre in content and to another in form. In some cases, the same program could even be attributed to different genres, or the same classification criteria might be employed to identify different genres (cf. Chandler 1997, 2; Charaudeau 1997a, 82; Jost 2009, 40s.). Therefore, most of the recent approaches to genres focus not only on the structure of television production and programming, but also on spectator habits and expectations (cf. Mikos 2008). Within this perspective, the standardizations regarding form and content depend upon technical, economic, political and legal constraints as well as on dramaturgical, narrative and artistic tools (cf. Mikos 2008, 262). The relationship between producers and audience thus becomes a critical factor in any analysis of television text types: “A basic model underlying contemporary media theory is a triangular relationship between text, its producers and its interpreters” (Chandler 1997, 5).

Identifying a text belonging to a specific genre might awaken the interest of a spectator or, on the contrary, provoke a negative attitude. Genres thus also incorporate the producer’s assumptions concerning their audience in terms of social criteria, beliefs, taste, reactions, etc. Thus, they insure the loyalty of their audience and the TV ratings, “The relative stability of genres enables producers to predict audience expectations” (Chandler 1997, 5). In this respect, genres allow producers to make a profit with their product. A new genre emerges when a film or a program was particularly successful, so that producers will try to repeat such success by adopting similar patterns of narration and presentation. By doing so, they create a standardization that ensures an economic advantage (cf. Mikos 2008, 263). For many recent authors, the main function of genres is to aid the public to make sense of the broadcast, that is to say, by offering meaning and to “provide frameworks within which texts are produced and interpreted” (Chandler 1997, 5). A prominent example is Schmidt’s (2003) theory of genre39 that distances itself from the actual classification offered by the media and defines genres according to cognitive and communicative schema with an orientation function (cf. Schmidt 2003). This functional approach does not question what genres are, but instead how people deal with them, i.e., the meaning cannot be found in the object itself (the media product itself), but is attributed by the audience depending on the social context (cf. Schmidt/Weischenberg 1994, 212). Linking a text to a specific genre directs its reception and interpretation and the construction of meaning. For example, recognizing a given text as fictional instead of non-fictional results in a different understanding of its meaning. The distinction between fictional and nonfictional texts is in fact a very fundamental one that can be found in almost every typology. However, it is not in itself sufficient, as we shall see in the following paragraphs.

3.3Genres between fictional and non-fictional worlds

We probably owe one of the most detailed discussions of the relationship between the fictional and non-fictional world to the internationally-known French scholar Jost (1997; 2003; 2009; 2011). His classification system positions television within the arts of image and sound (cf. Lochard/Soulange 1998, 93). In his initial writings, he adopts a strict audience-based perspective and conceives the genre as a promise (“La promesse des genres”) regarding the relationship between image and reality/authenticity. This promise guides the spectator in his perception and understanding of what is viewed. According to Jost (2011, 24), static definitions of genre that are independent of their use would mislead the interpretability as the same broadcast might be seen as fiction, documentary or artwork, depending on which particular elements of the audiovisual material are selected. Based on the assumption that the evidence for reality or fiction is not an inherent part of the object but of the subject,40 he proposes a classification of genres according to three modalities of utterance (modes d ’énonciation): (1) the informative mode (mode informatif) that reports the truth and indicates how the assertions can be proved, (2) the fictive mode (mode fictif) where the only rule is coherence within the created universe, and (3) the ludic mode (mode ludique) that creates its own rules (cf. Jost 1997, 22; 2011, 25).

Fig. 1 shows the dynamic character of this model on a macro level,41 and allows us to situate, on a micro level, the “classic” genres such as news, talk shows, documentaries, etc. as well as incorporate future genres (cf. Jost 2011, 26). Finally, the interpretation of a program depends on which of the modes is recognized by the spectator. An example reported by Jost (2011, 26) is the case of the faked 2006 Belgium television news program that announced the separation of Belgium into two independent states. The audience reaction varied from fear to laughter depending on the spectator’s ability to uncover the farce.42

In response to the critics of his model as well as to the events of 9/11 and to the adaptation of “Big Brother” in France (fr. “Loft Story”), Jost (2011, 28) modified the criteria of modes into that of worlds (mondes). In fact, the model in Fig. 1 has a disadvantage in that it presupposes some knowledge about genres and their discursive characteristics (cf. Jost 2011, 28). In the revisited model, such knowledge is not required; instead of a narrative model, the perspective becomes semiotic. It takes into account that the spectators first perceive the object that is represented by the image and only thereafter appreciate its narrative structure. This means that the first reflex of a spectator is to determine if the images refer to our real world (le monde réel) or not. We willingly oppose the fictive world (le monde fictif) to the real world and are ready to accept events that we would not believe to be possible in the latter (cf. Jost 2009, 42). Finally, the ludic world (monde ludique) invokes either the real or the fictive world and refers to itself (cf. Jost 2009, 44). In this model, it is the sign that is interpreted through its reference to a real or fictive object; or it itself becomes the object.

The new model also considers the producers’ point of view. With the arrival of reality TV, the above mentioned promise concerning the relationship between image and reality becomes fuzzy, e. g., “Loft Story” was promoted by sometimes highlighting its authentic, and at other times its fictive or ludic character. Similarly, misinterpreting the faked Belgium newscast about Flanders’ independence was only possible because, according to the producers, the audience had not learned to understand images and took the attributed genre for granted, i.e., spectators normally believe that a program labeled as news is indeed anchored in the real world (cf. Jost 2011, 32).

Attributing a program to a specific genre is also linked to legal and economic interests (cf. Jost 2009, 46s.). For example, the French channel TF1 must dedicate 16% of its net profits earned during the previous year to new original or European programming, scheduled between 8 and 9 PM, among which 120 hours must comprise new French fiction (cf. Jost 2009, 46). France Télévision is obligated to broadcast at least one cultural program every day in the early evening (cf. Jost 2009, 47). Consequently, defining a program as being fiction or cultural would allow the channels to fulfill these obligations. Jost (2009, 47) also shows, using the example of the casting show “Popstars”, how broadcasting companies use and manipulate the genre concept in order to be eligible to obtain production funds (Compte de soutien à l’industrie des Programmes) which exclude entertainment type programs. In the case of “Popstars”, the show has been classified as a documentary, that is to say, its relationship to the real world has been overemphasized while its affiliation to the fictive and ludic world is undermined. Obviously, attributing a given program to a specific genre becomes a matter of economic relevance. Ultimately, the spectator should be wary of the proposed categorization of a program, should confront it with what he or she views on the screen, and question the authority of the broadcast companies (cf. Jost 2011, 34).

3.4Text types in the information domain

Approaches involving a text-based linguistic and discourse-analytical orientation deal mainly with the informative domain (cf. Charaudeau 1997a; Burger 2000; 2004; Lüger/Lenk 2008). Although they primarily focus on the textual or discursive characteristics or on the narrative structure of texts, they do this in relation to text function and intention and also consider various pragmatic aspects.43

Within the French context, Charaudeau’s (1997a; 1997b; 22011) discourse-analytical approach has to be mentioned here and will be outlined in the following pages. He also deals exclusively with media information and offers a typology that applies to press, radio and television. Charaudeau (1997a, 91) explicitly rejects approaches that use the categories of function (associated with the three traditional television functions to inform, to entertain, and to educate), effects (emotional, cognitive), and modes (informative, fictive, ludic). According to him, they are too general and overlap each other, mainly because of the dual aim of every media information discourse of being both credible and able to capture audience attention.

Although Charaudeau (1997a) focuses on the components of texts and offers a hierarchical typology including genres and subgenres, it would be shortsighted to simply label his approach as “typological” in opposition to “functional”44 since the text properties are analyzed against the background of their discursive functioning. Charaudeau actually tries to reconcile the two approaches and emphasizes the precautions one needs to take before importing typological genres into television (cf. also Charaudeau 1997b). He describes genres as text types and texts as the result of a speech act produced by a subject in a situation of contractual social exchange (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 85). The “communication contract” (contrat de communication) depends on situational constraints that allow speakers a degree of legitimacy as subjects. As in any other act of communication, media communication is interactive and contractual. This is because the meaning depends on the exchange between production and reception as well as on norms and conventions allowing a certain reciprocal understanding and the negotiation of meaning (cf. Charaudeau 1991, 11).45 The meaning of a text thus depends on the enunciative intention (finalité-visée énonciative), on the identity of the individual speakers (identité des partenaires de l’échange), the theme or subject matter (propos) and the specific material and physical circumstances in the exchange (dispositif) (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 85).

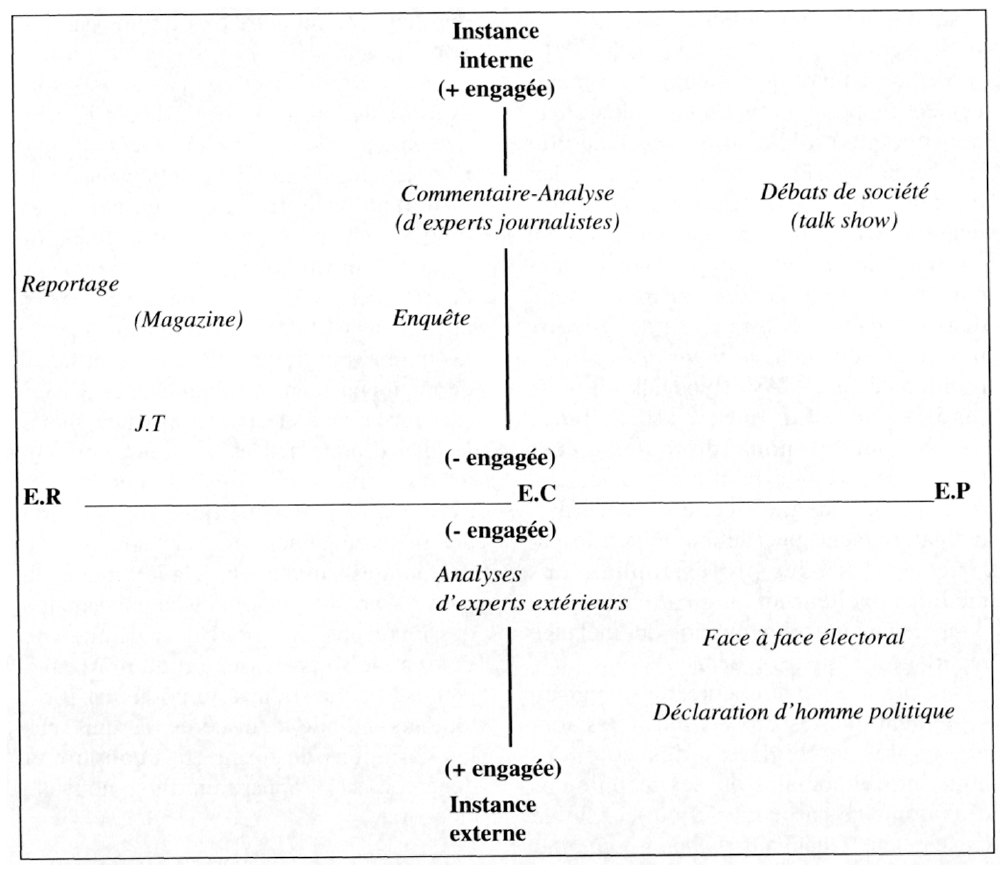

While a model integrating many variables reflects the complexity of genres at the cost of intelligibility, a model based upon few variables would be rather reductive. For this reason, Charaudeau (1997a, 87) suggests building a basic typology capable of embedding successive typologies as represented in Fig. 2. For him,

“[…] hors quelques rares textes entièrement codifiés (comme les textes sacrés), tout texte est composite du point de vue discursif, et donc un type de texte ne peut être défini que comme une classe de propriétés semblables, c’est-à-dire un représentant abstrait des textes qui sont censés y correspondre. On n’a affaire ici qu’à un positionnement doublement relatif des types: d’une part par rapport aux pôles des deux axes, d’autre part les uns par rapport aux autres” (Charaudeau 1997a, 90).46

On the horizontal axis of this basic typology (Fig. 2) are situated three zones of discursive modes (modes discursifs): the “reported event” on the left side (E.R = événement rapporté), the “provoked event” on the opposite side (E.P. = événement provoqué) and in-between the “commented event” (E.C. = événement commenté). These modes concern the general handling of the information, allowing us to define a reportage within the reported event, a debate within the provoked event and an editorial within the commented event since the latter may relate to either the one or the other explaining causes, motives, intentions, etc.

The vertical axis opposes the actual entity of the enunciators (instances énonciatrices): the “internal entity” (instance interne) belongs to the media itself (e. g., a journalist), the “external entity” (instance externe) has its origin outside of the media (e. g., an expert, a politician). The continuum between the two identifies the respective degree of commitment, i.e., the enunciator more or less expresses their own opinion. For example, commitment is related to the identification of the news source or to the manner by which the word is given to the protagonists.

Combining the above-mentioned discursive modes with another text component – the topic – would allow us to define subgenres, e. g., we would be able to differentiate between different kinds of debate depending on whether the topic is cultural, political or scientific.

Considering the characteristics of the scenic setup (dispositif scénique) that further specifies a given text within its material component would allow us to differentiate genres according to the media support (press, radio, television). An important particularity of television is the combination of the two semiological systems: sound and image. The confluence and combination of both, the characteristics of the televisual setup and the two semiological materials, determine the specificity of television text types as opposed to other media text types. This is why television texts have to be studied as multisemiotic and multimodal phenomena. Here non- and paraverbal elements are not simply added to the verbal text, but all interrelate in different ways and contribute thus to the construction of meaning (cf. Houdebine-Gravaus 1991; Lüger/Lenk 2008, 16).47 The setup also contributes to the process of constructing meaning: filming, framing, angle of view, cutting techniques and the arrangement of elements in the studio all produce different perceptions of what is shown and can influence audience interpretation (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 92). Regarding the discourse, Charaudeau (1997a, 92) identifies five utterance types: description, explanation, testimony, proclamation and contradiction. Finally, he attributes three functions to the image: designation (in order to create effects of authenticity), figuration (in order to create effects of verisimilitude) and visualization (in order to create effects of discovering the truth). The combination of these features and their relative dominance generate highly complex television text types.

4The dynamic and historical nature of genres and text types

As cultural conventions carrying meaning and based on a reciprocal relationship between producers and audience, genres are closely linked to social context and undergo constant change. They obey economic pressure and public expectations in order to attract an audience and depend on the dominant ideologies of a historical period reflecting social and cultural values (cf. Chandler 1997, 4; Mikos 2008, 264). They also take in changes in communication conventions, e. g., one can observe changes in the way of interviewing politicians, facilitating a debate or presenting news (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 90). But their change is also related to the evolution of technologies that offer more and more possibilities in staging (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 90). Finally, every new text contributes to some variation and change of the genre it belongs to.

The emergence of new genres can be explained by applying the prototype theory of cognitive science to media studies. According to Hickethier (2002, 71), a very successful individual case becomes the starting-point for the birth of a specific genre. Its prototypical nature stems from its patterns of narration and presentation that differ considerably from those that existed previously. Forms and structures of this popular prototype are reproduced and new variants are created that are linked to each other by resemblance. The new set of variants constitutes a specific genre (cf. Hickethier 2002, 71). However, from the audience perspective, the prototype as the best member of a category is not traced back to the emergence of a genre, but is based on the concrete viewing experience (cf. Mikos 2008, 265). This is why personal affinities, cultural norms and social criteria influence which prototype comes to mind (cf. Mikos 2008, 267).

Considering genres as a set of variants related by similarity also means that, with time, the variants move further away from the prototype until the new products are so different that they can no longer be considered as variants. Consequently, genres are transformed, new genres and sub-genres emerge and others are no longer pursued because they have lost popularity. Also, endless multiplication of genres is self-limiting since they bring order by organizing huge amount of texts into simpler categories (cf. Hickethier 2002, 74). These changes, however, do not occur abruptly, but rather bit by bit, respecting the communicative contract.

The most striking recent development concerns the trend towards mixed genres, often referred to as hybrid genres, that make the unambiguous classification of a text under a single genre difficult, even impossible (cf. Mikos 2008, 270). However, the use of the designation mixed genres is inconsistent. Most of the time, it refers to a mixing of Jost’s “worlds”, e. g., docu-fiction (real + fictive world), infotainment (real + ludic world; cf. Jost 2009, 50). This is the meaning that Veyrat-Masson (2008) uses in her analysis of a very specific case of hybrid genres: the television programs that pretend to reconstruct the past and to be close to specific historical events, but that, at the same time, mix fiction and reality, documents and references (cf. Veyrat-Masson 2008, 5). The mixing of fictional and non-fictional genres has become particularly frequent and sometimes represents a source of irritation for the audience (cf. Jost 2009, 41). While the mixing of reality and fiction in the case of programs that deal with historical topics serves to attract the audience and to awaken their interest in history, it becomes a crucial matter since it touches on our perception of the past and the truth of what constitutes our collective memory, our group identity and even political issues (cf. Veyrat-Masson 2008, 6).

Hybrid genres can be “additive” or “integrated” (Kilborn 2003, 12). Whereas additive forms display influences from different genres (e. g., in magazines), integrated forms combine different genre elements into new forms (e. g., reality shows). Additive forms appeared already in the 1980s and were a direct response to the new habit of “zapping”, made possible through the television remote control; they enable people to instantly embark on an ongoing program and are aimed at reaching different audience target groups. Integrated forms such as reality shows are a more recent marketing strategy in search of satisfying the everlasting need for innovation. They stem from growing economic constraints as a result of competition between channels, of changes in the status of media organizations and of modifications in the regulations governing cable TV. Finally, such mixing might be observable when there is discordance between the topic and the manner in which it is treated (cf. Jost 2009, 51) or simply in a mingling of public and private topics as is the case in reality and talk shows (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 100).

Other changes concern the increase in contact with the audience, creating an illusion of friendliness and connivance in contrast to the greater distance that existed formerly between the media and public. Furthermore, there is a tendency toward a continuous flow of similar programs so that everybody can feel “at home” as opposed to the earlier tradition of scheduling well-defined and targeted scheduled appointments for different audience groups. Correspondingly, one can observe a trend towards the shortening of programs and a kind of “clip” form (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 99; Charaudeau 22011, 195; Duccini 1998, 5).

All these recent changes are symptoms of the transition since the 1980s from the so-called paleo-TV (paléo-télévision) towards a neo-TV (néo-télévision, cf. Eco 1985).48 This transformation was a result of the influence of American media culture leading to the emergence of private channels and, accordingly, to growing competition in the French television landscape (cf. Lochard/Boyer 1998, 67; Bourdon 2001). While paleo-TV is characterized by an asymmetric and hierarchical relationship between the television and its more passive audience, neo-TV focuses more on relating with the public as active citizen-spectators (cf. Jost 1997; Duccini 1998). It should be noted that this evolution has often been criticized since paleo-TV had an explicit educational purpose (cf. the three “classical” functions of TV – to inform, to educate, to entertain), whereas neo-TV, whose main goal is that of seducing and amusing the audience, is seen as being mainly commercially oriented.

5The television newscast as a prototypical text type

As television newscasts (le journal télévisé = JT) are generally considered a prototypical text type (cf. Lebsanft 2001, 294), it is particularly interesting to verify how the most salient characteristics of television text types can be applied to them.

Newscasts are a perfect example for the above mentioned hybrid genres. Contemporary television news integrates many different text types such as reports, interviews, etc. Burger (2000; 2004) highlights the existence of large formats that integrate the traditional text types as components and that correspond to the “additive form”. A common type in television is represented by the magazine. Burger (2000; 2004) postulates a multilevel structure: On the “macro-level”, he situates the magazine as a whole (e. g., the news journal as a whole), on the “meso-level”, each contribution (e. g., thematic sections such as national/international) and, on the “micro-level”, each element/text type within each contribution (e. g., presentation, film report, commentary).

On the vertical axis of Charaudeau’s typological model (cf. Fig. 2), the newscast would be situated in the upper half corresponding to the “internal entity” because everything is coordinated and carried out by the media personnel in charge. However, with respect to commitment, it is situated rather low on this axis due to the requirement of objectivity (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 94; 22011, 192).

On the horizontal axis, the newscast is strongly in line with the “reported event” according to an ideal communicative contract which postulates that news reports facts as they really are. Journalistic objectivity is obviously an ideal. As described by different theories on media studies (e. g., gatekeeping, agenda setting), other individual, organizational and institutional constraints will influence the selection of the information in order to draw attention to certain facts considered to be of “public interest” at the expense of others (cf. Shoemaker/Vos 2009; McCombs/Shaw 1972).

Still, the newscast includes all discursive modes: invited experts comment on events and debates between social protagonists are provoked. Finally, the particularity of newscasts in comparison with other genres resides in two dominant aspects: its intent (propos) and the identity and interrelation of the partners (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 94; 22011, 192).

The first aspect (intent) concerns the here and now: a newscast cuts what has happened in the public domain during the temporal unit of a day; it is thus based on a thematic fragmentation imposed by the media (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 94; 22011, 193). Depending on the topics, news can further be subdivided into “hard news” (e. g., central political, economic and cultural topics) and “soft news” (e. g., gossip, accidents, scandals considered of human interest) as well as spot news (e. g., crimes; cf. Burger 2004, 211; Lüger 21995, 94 ss.).

The second aspect (identity and interrelation) relates mainly to the role played by the announcers who have a pivotal role and organize the newscast. With their greetings they open the newscast and establish contact between the studio and the audience. They build up the image of personalized commentators expressing themselves as if they were appealing directly to every individual spectator. Moreover, they ensure the link between the referential world and the audience. They hold the reins in their hands, function as guides throughout the newscast, invite and take back the conversation, run reports and interview invited guests and experts, schedule an appointment for the next day, etc. (Charaudeau 1997a, 94; 22011, 193; cf. also Bourdon 2001, 225).49 Martel describes the role of the “anchorman” as a way of “personifying news”, i.e.

“[…] c’est recourir à un support humain, non pas comme un simple intermédiaire de transmission entre l’information et le public, mais comme un lieu privilégié d’émergence, d’incarnation de la nouvelle permettant au téléspectorat d’interpréter l’information comme étant inscrite dans l’humanité, le caractère humain du présentateur s’attachant d’emblée à la nouvelle, l’humanisant” (Martel 2002, 1).50

Whereas simply reading the news establishes a certain distance with the audience who would thus feel less concerned by the events, the anchorman ensures an interactional relationship between himself and the public. He not only reports the events, but becomes a “discursive personality” (personnalité discursive), a TV star who relates the perception of the world to his own. Personifying news thus implies the building of a human image favoring the emergence of the news (cf. Martel 2002, 1).

Finally, all of these characteristics demonstrate that the newscast type of genre only delivers a world of events created by itself. Consequently, it is all about establishing the illusion of realism rather than the real truth and it is this “making believe” that defines a newscast (cf. Charaudeau 1997a, 95; 22011, 194). In this regard, the position of the newscast (JT) in the lower left angle of Jost’s model (cf. Fig. 1) could be questioned.

However, the role of an announcer as “anchorperson” has not always been such. In France, the traditional news format of the 1950/1960s was characterized by an invisible presenter or by a succession of more than one presenter within the same newscast.51 In no way was the announcer responsible for the program; his function was reduced to reading the news, and he was not required to establish any form of relationship with the audience. This might be explained by a rejection of the star system, considered incompatible with the seriousness and objectivity of information (cf. Bourdon 2001, 222). The “anchorman”52 was imported from the USA in the 1970s; TF1 introduced this type of presenter in each of its three newscasts in 1975, but one had to wait until 1981 before the anchorman also took on the role of chief editor (cf. Bourdon 2001, 225s.). These changes in the role of the announcer appeared along with the reorganization of the television landscape, including the opening up to the private sector, the multiplication of channels and the greater dependence on advertising revenues (cf. Duccini 1998, 67). Importing the American anchorman-model was thus a consequence of commercialization and the growing competition between channels since the anchorman, through his voice and image, became a distinctive feature of the newscast and insured the loyalty of the audience (cf. Martel 2002, 1; Duccini 1998, 6). Nowadays, it represents the predominant model all over the world, with only few exceptions like the German ARD-news where the announcer has no editorial responsibilities but simply acts as “speaker” (cf. Bourdon 2001, 226).

6Television text types and language

As already mentioned, the “raison d’être” of an article about television text types in a “Manual of Romance Languages in the Media” is the relationship between text types and language use in this medium. Even though a special television language does not exist, one can observe some tendencies in the manner in which language is used and what is selected from the linguistic repertory (cf. Schmitz 2004, 33). It is beyond the scope of the present article to discuss in detail the language use in television which depends on many other factors such as its multimodal character (cf. Houdebine-Gravaus 1991; Lebsanft 2001, 298; Lüger/Lenk 2008, 16) and the particular production process (cf. Holly 2002, 2455). For further details, the interested reader should consult the publications of the International Colloquium “Le français parlé dans les médias” (e. g., Broth et al. 2007; Martel 2010; Burger/Jacquin/Micheli 2010) as well as the recent collective work by Mauroni/Piotti (2010).53 However, here some salient features linked to the relationship between language and text types will be mentioned in brief.

As we have seen in this article, television is a highly complex composition of text types/genres and it is not surprising that this heterogeneity is also reflected in the language use. Any attempt to identify the role of language in television communication has to take into account television text types as unique linguistic expressions of television communication (cf. Lebsanft 2001, 293).

If one asks a “normal” spectator (one not particularly interested in linguistic questions) about the most salient feature of language use in television, there is a good chance that he would point to television as being responsible for the so-called deterioration of language, i.e., the negative influence of television on language use in general (cf. Lebsanft 2001, 293; Schmitz 2004, 26; Reinke 2004; 2005). For many spectators, television serves as a model in language matters and should reflect the standard variety because of its public character. Nevertheless, the requirements for creativity and originality linked to the competitive environment, the commercial pressure, the shifting from a more informative to a more entertaining television format, etc. have resulted in rapid modifications of media text types as well as in steady language innovations (cf. Lüger/Lenk 2008, 15). This tendency has certainly accelerated with the appearance of neo-TV oriented towards the audience. As television tries to approach everyday experiences, conversational text types are more and more favored, such as those illustrated by the increase in talk shows and interviews. It would thus be particularly interesting to pursue research from an interactional perspective such as undertaken by Thompson (1995), Scollon (1998), Hutchby (2005) and Martel (2008). The result of this is a proliferation of non-standard language forms (cf. Holly 2002, 2456; Reinke 2004 and 2005; Martel et al. 2010).

The categorization of text types/genre becomes of crucial interest in nuancing this idea related to the increase in more informal language varieties and in arguing against the supposed degradation of language quality. By applying the theory and methods of language variation to television text types (cf. Labov 1976; Koch/Oesterreicher 22011), one can actually observe language variation depending on text types/genres similar to that occurring in everyday situations (cf. Reinke 2004 and 2005; Martel et al. 2010). Finally, if while it is true that, globally, a huge amount of informal language forms can be identified within television communication, it is also true that they are governed according to similar norms that govern language use in daily life (cf. Reinke 2004 and 2005). Professional television speakers use their communicative abilities to exploit the possibilities offered by the linguistic variation and to dose the frequency of informal variants according to their socio-stylistic values. The use and dosage of these forms contributes to simulating an authentic relationship with the audience (cf. Martel et al. 2010, 103). Of course, investigating how the discursive entities and the extralinguistic conditions determine verbalization (cf. Lebsanft 2001, 297) also means that television language can be considered as a “secondary orality”, i.e., it is based on the written word and prepared in such a way as to imitate or stage spontaneity (cf. Koch/Oesterreicher 22011; Holly 2002, 2455). However, within the constraints of the medium, actual language use depends on the communicative intention and hence on the text type (cf. Lebsanft 2001, 298; Reinke 2004).

7Conclusion

As we have seen in this article, many aspects have to be taken into account when investigating television text types and these could not all be included. Because interdisciplinary communication is lacking, it is difficult to summarize all existing approaches. Instead, I have selected two important approaches within the French research tradition, those of Jost and Charaudeau. While the first places television genres within the tradition of pre-existing audiovisual forms, the latter concentrates on the specificities of television information. However, both situate text types/genres along a continuum. Even though the notion of television text type/genre poses many problems, we have seen that it is very useful since it offers practical advantages for both producers and spectators as well as methodological advantages for researchers; it also represents a reality in people’s minds since spectators will always attempt to understand and categorize what they see on the screen. One main problem is the absence of interdisciplinary communication between scholars coming from different disciplinary backgrounds who do not always share their results. A quick look at the reference list of most publications on this subject confirms that scholarly exchange only occurs within the boundaries of each discipline. This makes it difficult to obtain a comprehensive understanding of this very complex phenomenon. Bringing together, through a more global approach, scholars working on television text types/genres would thus be one of the most urgent desiderata.

8References

Adam, Jean-Michel (1992), Les textes: types et prototypes. Récit, description, argumentation, explication et dialogue, Paris, Nathan.

Adamzik, Kirsten (2007), Die Zukunft der Text(sorten)linguistik. Textsortennetze, Textsortenfelder, Textsorten im Verbund, in: Ulla Fix/Stephan Habscheid/Josef Klein (edd.), Zur Kulturspezifik von Textsorten, Tübingen, Stauffenburg, 15–30.

Aschenberg, Heidi (2002), Historische Textsortenlinguistik – Beobachtungen und Überlegungen, in: Martina Drescher (ed.), Textsorten im romanischen Sprachvergleich, Tübingen, Stauffenburg, 153–170.

Bakhtine, Mikhaïl (1984), Esthétique de la création verbale, traduit du russe par Alfreda Aucouturier, Paris, Gallimard.

Bourdon, Jérôme (1988), Propositions pour une sémiologie des genres audiovisuels, Quaderni 4 – Les mises en scènes télévisuelles, 19–36.

Bourdon, Jérôme (2001), Genres télévisuels et emprunts culturels. L’américanisation invisible des télévisions européennes, Réseaux 107, 211–236.

Broth, Mathias, et al. (edd.) (2007), Le français parlé des médias. Actes du colloque de Stockholm 8–12 juin 2005, Stockholm, Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis.

Burger, Harald (2000), Textsorten in den Massenmedien, in: Klaus Brinker et al. (edd.), Text- und Gesprächslinguistik: ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung, vol. 1, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, 614–628.

Burger, Harald (2004), Mediensprache. Eine Einführung in Sprache und Kommunikationsformen der Massenmedien, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter.

Burger, Marcel/Jacquin, Jérôme/Micheli, Raphaël (edd.) (2010), Les médias et le politique. Actes du colloque “Le français parlé dans les medias”, Lausanne, 1–4 septembre 2009, Lausanne, Centre de linguistique et des sciences du langage, <http://www.unil.ch/clsl/page81503.html> (19.10.2016).

Casetti, Francesco (2001), Filmgenres, Verständigungsvorgänge und kommunikativer Vertrag, Montage-av: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Geschichte audiovisueller Kommunikation 10:2, 155–173.

Chandler, Daniel (1997), An introduction to Genre Theory, <http://visual-memory.co.uk/daniel/Documents/intgenre/chandler_genre_theory.pdf > (19.10.2016).

Charaudeau, Patrick (1991), Contrats de communication et ritualisations des débats télévisés, in: Patrick Charaudeau (ed.), La Télévision. Les débats culturels “Apostrophes”, Paris, Didier Érudition, 11–35.

Charaudeau, Patrick (1997a), Les conditions d’une typologie des genres télévisuels d’information, Réseaux 15:81, 79–101.

Charaudeau, Patrick (1997b), Le discours d’information médiatique. La construction du miroir social, Paris, Nathan.

Charaudeau, Patrick (22011), Les médias et l’information. L’impossible transparence du discours, Bruxelles, De Boeck.

Dammann, Günter (2000), Textsorten und literarische Gattungen, in: Klaus Brinker et al. (edd.), Text- und Gesprächslinguistik: ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung, vol. 1, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, 546–561.

Dimter, Matthias (1981), Textklassenkonzepte heutiger Alltagssprache, Tübingen, Niemeyer.

Duccini, Hélène (1998), La télévision et ses mises en scènes, Paris, Nathan.

Dufiet, Jean-Paul (2009), Manipulation et information fictionnelle, Communication 27:2, 133–149.

Große, Ernst Ulrich/Seibold, Ernst (1994), Typologie des genres journalistiques, in: Ernst Ulrich Große/Ernst Seibold (edd.), Panorama de la presse parisienne. Histoire et actualité, genres et langages, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang, 32–55.

Eco, Umberto (1985), Tv: la trasparenza perduta, in: Umberto Eco, Sette anni di desiderio. Cronache 1977–1983, Milano, Bompiani, 163–179.

Ekman, Paul/Sorenson, E. Richard/Friesen, Wallace V. (1969), Pan-Cultural Elements in Facial Display of Emotions, Science 164, 86–88.

Fix, Ulla (2008), Texte und Textsorten – sprachliche, kommunikative und kulturelle Phänomene, Berlin, Frank & Timme.

Hickethier, Knut (2002), Genretheorie und Genreanalyse, in: Jürgen Felix (ed.), Moderne Film Theorie, Mainz, Bender, 62–96.

Holly, Werner (2002), Fernsehspezifik von Präsentationsformen und Texttypen, in: Joachim-Felix Leonhard et al. (edd.), Medienwissenschaft. Ein Handbuch zur Entwicklung der Medien und Kommunikationsformen, vol. 3, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, 2452–2464.

Houdebine-Gravaus, Anne-Marie (1991), La mise en scène gestuelle, in: Patrick Charaudeau (ed.), La Télévision. Les débats culturels “Apostrophes”, Paris, Didier Érudition, 93–101.

Hutchby, Ian (2005), Conversation analysis and the study of broadcast talk, in: Kristine L. Fitch/Robert E. Sanders (edd.), Handbook of Language and Social Interaction, Mahwah (N.J.), Erlbaum, 437–460.

Jolicoeur, Martin (2014), Le politicien entre stratégies et contraintes: l’analyse conversationnelle et l’analyse du discours pour revisiter la problématique des genres en communication publique, Colloque annuel des Journées de linguistique, Québec, CIRAL.

Jost, François (1997), La promesse des genres, Réseaux 15:81, 11–31.

Jost, François (2003), La télévision du quotidien. Entre réalité et fiction, Bruxelles, De Boeck.

Jost, François (2009), Comprendre la télévision et ses programmes, Paris, Colin.

Jost, François (2011), “Mode” oder “monde”? Zwei Wege zur Definition von Fernsehgenres, in: Jörg Türschmann/Birgit Wagner (edd.), TV global. Erfolgreiche Fernseh-Formate im internationalen Vergleich, Bielefeld, Transcript, 19–35.

Keane, Michael/Fung, Anthony/Moran, Albert (2007), New Television, Globalisation, and the East Asian Cultural Imagination, Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press.

Kilborn, Richard (2003), Staging the Real. Factual TV programming in the Age of “Big Brother”, Manchester/New York, Manchester University Press.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (22011), Gesprochene Sprache in der Romania, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter.

Labov, William (1976), Sociolinguistique, traduit de l’anglais par Alain Kihm, Paris, Minuit.

Lebsanft, Franz (2001), Sprache und Massenkommunikation, in: Günter Holtus/Michael Metzeltin/Christian Schmitt (edd.), Lexikon der Romanistischen Linguistik, vol. I,2: Methodologie Tübingen, Niemeyer, 292–304.

Lochard, Guy/Boyer, Henri (1998), La communication médiatique, Paris, Seuil.

Lochard, Guy/Soulange, Jean-Claude (1998), La communication télévisuelle, Paris, Colin.

Lüger, Heinz-Helmut (21995), Pressesprache, Tübingen, Niemeyer.

Lüger, Heinz-Helmut/Lenk, Hartmut E. H. (2008), Kontrastive Medienlinguistik. Ansätze, Ziele, Analyse, in: Heinz-Helmut Lüger/Hartmut E.H. Lenk (edd.), Kontrastive Medienlinguistik, Landau, Verlag Empirische Pädagogik, 11–28.

Martel, Guylaine (2002), Personnifier l’information, Communication au 70e Congrès annuel de l’Association canadienne-française pour l’avancement des sciences (Acfas), Université Laval, Québec (mai 2002).

Martel, Guylaine (2004), Humaniser les téléjournaux. Les lieux privilégiés du journalisme d’interaction au Québec, Les Cahiers du journalisme 13, 182–205.

Martel, Guylaine (2008), Un point de vue interactionnel sur la communication médiatique, in: Marcel Burger (ed.), L’analyse linguistique des discours médiatiques. Entre sciences du langage et sciences de la communication, Québec, Nota bene, 113–133.

Martel, Guylaine (ed.) (2010), Mises en scène du discours médiatique, Numéro spécial: Communication 27:2.

Martel, Guylaine, et al. (2010), Variations sociodiscursives dans la mise en scène de l’information télévisée, in: Wim Remysen/Diane Vincent (edd.), Hétérogénéité et homogénéité dans les pratiques langagières: mélanges offerts à Denise Deshaies, Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 87–114.

Mauroni, Elisabetta/Piotti, Mario (edd.) (2010), L’italiano televisivo. 1976–2006, Firenze, Accademia della Crusca.

McCombs, Maxwell E./Shaw, Donald L. (1972), Agenda-Setting-Function of Mass Media, The Public Opinion Quarterly 36:2, 176–187.

Mikos, Lothar (2008), Film- und Fernsehanalyse, Konstanz, UVK.

Mittell, Jason (2001), A cultural approach to television genre theory, Cinema Journal 40:3, 3–24.

Nies, Fritz (1978), Das Ärgernis “Historiette”. Für eine Semiotik der literarischen Gattungen, Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 89, 421–439.

Reinke, Kristin (2004), Sprachnorm und Sprachqualität im frankophonen Fernsehen Québecs. Untersuchung anhand phonologischer und morphologischer Variablen, Tübingen, Niemeyer.

Reinke, Kristin, en coll. avec Luc Ostiguy (2005), La langue à la télévision québécoise: aspects sociophonétiques, Québec, Office québécois de la langue française.

Rusch, Gebhard/Hauptmeier, Helmut (1988), Projektbericht Mediengattungstheorie, SFB 240, Universität Siegen.

Schaeffer, Jean-Marie (1986), Du texte au genre, in: Gérard Genette/Tristan Todorov (edd.), Théorie des genres, Paris, Seuil, 179–205.

Schmidt, Siegfried J. (2003), Kognitive Autonomie und soziale Orientierung. Konstruktivistische Bemerkungen zum Zusammenhang von Kognition, Kommunikation, Medien und Kultur, Münster, LIT.

Schmidt, Siegfried J./Weischenberg, Siegfried (1994), Mediengattungen, Berichterstattungsmuster, Darstellungsformen, in: Klaus Merten/Siegfried J. Schmidt/Siegfried Weischenberg (edd.), Die Wirklichkeit der Medien, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 212–236.

Schmitz, Ulrich (2004), Sprache in modernen Medien. Einführung in Tatsachen und Theorien, Themen und Thesen, Berlin, Schmidt.

Scollon, Ron (1998), Mediated Discourse as Social Interaction. A Study of News Discourse, London, Longman.

Shoemaker, Pamela J./Vos, Tim P. (2009), Gatekeeping Theory, New York, Routledge.

Thompson, John B. (1995), The Media and Modernity. A Social Theory of the Media, Cambridge, Polity Press.

Türschmann, Jörg/Wagner, Birgit (2011), Vorwort, in: Jörg Türschmann/Birgit Wagner (edd.), TV global. Erfolgreiche Fernseh-Formate im internationalen Vergleich, Bielefeld, Transcript, 7–16.

Veyrat-Masson, Isabelle (2008), Télévision et histoire, la confusion des genres. Docudramas, docufictions et fictions du réel, Bruxelles, De Boeck.