12Language in the Media: The Process Perspective

Abstract: Drawing on a case study of newswriting at Télévision Suisse Romande, this chapter presents media linguistics as a subdiscipline of applied linguistics (AL), dealing with a distinctive field of language use. Language in the media is characterized by specific environments, functions, and structures. Medialinguistic research, however, tends to overcome disciplinary boundaries and collaborate with neighboring disciplines such as psychology, sociology, politology, and cultural studies. In multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary collaboration, it contributes to the development of empirically-grounded studies of mediatized language use and solves practical problems. The chapter first outlines such a practical problem. After explaining key concepts of media lingustics, it focuses on the linguistics of newswriting and four related research methods. Finally, it discusses the value media linguistics can add to both theory and practice of language use and the media.

Keywords: media linguistics, newswriting, progression analysis, public discourse, transdisciplinarity

1The LEBA case study: Staging the story by changing one word

How do communication professionals get their messages across?117 Why does news production change in increasingly multilingual environments? And, very generally, what is the role of language in a globally connected, multi-semiotic, and mediatized world? Answering such questions on empirical grounds requires medialinguistic approaches. Often, these approaches combine theories and methods from (applied) linguistics on the one hand and media and communication studies on the other. Also, media linguistic research tends to integrate practitioners’ views in transdisciplinary projects. Such endeavors result in systematic reflections of the value that findings can add to both theory and practice – and in empirically based practical measures such as training journalists for improving their writing processes and advising media institutions for improving their policies.

In this chapter, I use an example from my research to illustrate key concepts and procedures of media linguistics. The example is outlined in the next paragraphs and further developed throughout the text, when I explain questions of combining disciplines (2), epistemological interests of linguistics of newswriting (3), a set of complementary research methods (4) and outcomes for theory and practice (5).

Public service broadcasting companies are among the most important broadcasting companies in Europe. The Swiss public broadcaster, SRG SSR, has the highest ratings in the country. As a public service institution, SRG SSR has to fulfill a federal, societal, cultural, and linguistic mandate: promote social integration by promoting public understanding between social groups such as urban and rural, poor and rich, lay persons and experts, immigrants and citizens. As a media enterprise, though, SRG SSR is subject to market and competitive forces. Losing audience would mean losing public importance and legitimacy for public funding. The Idée Suisse research project, used as an example in this chapter, investigated how those working for the broadcaster deal with these two key expectations they experience as basically contradictory.

Epistemologically, the researchers aimed at reconstructing promoting public understanding as the interplay of situated linguistic activity with social structures throughout levels and timescales, from the minutes and hours of writing processes in the newsroom to the years and decades of societal change. The research question and the theoretical approach led to four project modules, focusing on media policy (module A), media management (B), media production (C), and media reflection (D). The result of this procedure was a detailed insight into stakeholders’ conflicting expectations and stances. Media policy expects public media to promote public understanding through their communicational offers, whereas media management considers implementing the mandate as infeasible or irrelevant in the face of market pressures. Grounded in these data, the mid-range theory of promoting public understanding was developed (cf. Perrin 2013, 8).

A key inference from this theory is that, for the case of SRG SSR, if solutions of bringing together public and market demands cannot be revealed in the management suites of the organization, they have to be looked for in the newsrooms. This meant a focus on journalistic practices in the second phase of the project. Therefore, module C of the research project (i.e., journalists’ media production), focused on observable text production activity. 120 newswriting processes were analyzed and contextualized with knowledge about: explicit editorial norms of text production; writers’ individual and organizational situations; and writers’ individual and shared language awareness. One example of this linguistic newsroom ethnography is the LEBA case.

The LEBA case study investigates the production of a news piece about demonstrations in Lebanon. These demonstrations occurred in a context of ethnic and religious diversity as well as expansion plans of neighboring countries repeatedly threatening national unity in Lebanon. In 2005, the Lebanese Prime Minister, Rafik Hariri, was killed in a bomb attack, and on February 14, 2007, the second anniversary of the assassination was commemorated with a national demonstration in Beirut. Télévision Suisse Romande started covering the topic in the noon issue of their daily news program, “Téléjournal”. While European media often report on politically motivated violence in Lebanon, the journalist R.G. highlighted peaceful aspects of the demonstrations in his news piece. The LEBA case illustrates the medialinguistic key concept of recontextualization (Part 1.1). Also, and more importantly, it documents the emergence and implementation of the idea to change one particular word and use it as a leitmotif of a news piece (1.2).

1.1Focus on recontextualization and intertextual chains

A first detail from the LEBA case that matters for the present chapter is the intertextual chain the journalist draws on. In his new item, R.G. integrates quotes, utterances from protesters in Lebanon, which are recorded by a video journalist (VJ) and then selected and modified by, first, a Lebanese television station; second, global newswires; third, Swiss national television SRG SSR; and fourth, the “Téléjournal” (TJ) newsroom (Fig. 1). Step by step, the utterance is recontextualized, shifted from one context to another. In this process, the protesters’ utterances are repeatedly reconstructed and thus nested in textual and communicative environments. These environments are influenced by agents and their stance(s) throughout the media system (cf. Perrin 2012).

1.2Focus on routine and emergence

At the 9:30 morning conference of the “Téléjournal” newsroom team on February 14, 2007, R.G. received the assignment to prepare an item about demonstrations in Lebanon for the noon edition of the “Téléjournal”. He found the deadline tight, which helped him concentrate on the main topic: tens of thousands of demonstrators from all over Lebanon streaming into Beirut on the second anniversary of the killing of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. They were protesting against the possibility of renewed civil war that would partition their country among neighboring countries and, above all, Syria’s influence. So far there had been no violence.

In an early phase in the writing process, R.G. wrote the voiceover for an introductory scene. The scene shows how people travelled en masse to the demonstration by boat. Finding these boats in the video material surprised him, he says. In his very first sentence, R.G. refers to another fact new to him: as he just learns from the news service, the Lebanese had that day off. So the beginning of the product was shaped by details that were new to the experienced journalist.

He then took a closer look at the pictures that were new to him and made a revision of a word that turned out to be the pivot point of the whole writing process. In the first sentence of the second paragraph, R.G. had first talked about an expressway to describe the direct route over the Mediterranean Sea, “la voie express de la méditerranée”. While interweaving the text with the images, R.G. realized that a tranquil path, “la voie tranquille”, would better fit the slow journey of a boat. So he deleted “express” and inserted “tranquille” instead.

With “tranquille” R.G. found the leitmotif of his item. In the retrospective verbal protocol recorded after the writing process (cf. below, Part 4.1), R.G. says that he loves the adjective because it corresponds not only to the image of the boats but also to the tranquility of the demonstration. He expects the “tranquil” to resonate in the minds of the audience. Just as consciously, he talks about using the term “drapeau libanais”, the Lebanese flag, as a symbol of the demonstrators’ desire for political independence.

Working with these visually attractive leitmotifs, R.G. overcame the critical situation of using brash stereotypes when under time pressure. Instead of catering to the market and resorting to predictable images that could overshadow publicly relevant developments, he absorbed his source material, listened to what was being said, and discerned what was important in the pictures. By doing so, he was able to discover a gentle access to the topic that allowed him to produce a coherent and fresh story and at the same time managed to reflect the political finesse required by his TV station’s mandate of promoting public understanding.

2Disciplines and beyond: Outlining media linguistics

The problem of promoting public understanding under time pressure illustrates that media constitute a socially important area of activity whose language use can differ from the use in other areas. This language use in media – and in a narrower sense, in journalistic media – is the focus of interest of media linguistics. In such an understanding, media linguistics is the subdiscipline of (applied) linguistics that deals with the relationship between language and media (e. g., Burger 2008; Perrin 2013).

As a subdiscipline situated between the theoretical and the applied variants of linguistics, media linguistics is guided by theory and practice. Guided by theory, it uses data from media settings to answer research questions raised by linguistics itself, such as language change in everyday contexts. Guided by practice, it clarifies problems of media practice with linguistic tools – and in doing so also assesses the scope of the theory (e. g., Candlin/Sarangi 2004, 3). The scientific discipline and professional field are therefore related to one another as shown below (Fig. 2).

Media linguistics, guided by theoretical research interests, can use insights from cases such as LEBA to investigate, for example, how language users deal with other people’s utterances. More generally, theoretically-oriented media linguistics analyses how production conditions of, e. g., journalistic media influence language use within these media, and, in reverse, how language use also influences the use and ultimately the social meaning of media, e. g., in journalism (e. g., Bell/Garrett 1998; Boyd-Barret 1994; Cotter 2010; Fairclough 1995; Fowler 1991; Kress 1986; Montgomery 2007). Guided by practice, it can search for language use that, for example, helps journalists handle quotes or leitmotifs in ways that foster public understanding.

From both theoretical and practical perspectives, all media-linguistic research can be situated in an internal (Part 2.1) and an external (2.2) structure of the discipline.

2.1Internal structure of media linguistics

So what is the primary interest of media linguistics? Fig. 3 (below) provides a schematic answer. It shows the field of language use in public discourse. The field is categorized into key issues of medialinguistic research. They specify and connect types of users, activities, and linguistic descriptions of language.

–Language users: the participants in public communication are the sources, the media producers, the target audiences, and the general public. Sources, media producers, and target audiences are directly involved in journalistic communication. The general public is involved indirectly, for instance when they participate in media blogs or talk to journalists or sources after reading, viewing, or listening (e. g., Lacey 2013) to media items (scope 1).

–Language activity: journalistic communication often restricts language users to either producer or receiver roles. Media producers, for example, tell stories (e. g., Salmon 2007) in close interaction with their professional enculturation (e. g., Marchetti/Ruellan 2001), and target audiences receive them (scopes 2 and 3). In communicative events such as research interviews or blogs, however, quick switching between producer and receiver roles is common (e. g., Messner/DiStaso 2008).

–Language description: linguistics considers language synchronically, at one point in time, or diachronically, over the course of time. A synchronic description can explain journalistic genres from a linguistic perspective (e. g., Lüger 1977; scope 4). A diachronic description can reveal language change over centuries (e. g., Studer 2008; Coupland 2014) or show whether and how one language influences another – e. g., how the language of sources can influence the language of journalistic media (scope 5).

2.2External structure of media linguistics

Scientific disciplines can be not only too wide for specific research, but also too narrow (e. g., Meyerhoff 2003; Sarangi/Van Leeuwen 2003). Inquiries into suitable methodology or into language use in journalistic media, for example, extend beyond media linguistics in general or the linguistics of newswriting in particular. They call for approaches that reach across several disciplines (e. g., Rampton 2008).

–In multidisciplinary research, scientific disciplines cooperate by addressing shared research questions. In the Idée Suisse project for example, writing research and methodology share their interest in methods to capture writing processes at the workplace. Their contributions to a methodological framework complement each other. Methodology brings in knowledge about triangulating methods; writing research contributes knowledge about key logging at computer workplaces, such as at the journalists’ desk and the cutting room in the LEBA case (cf. below, Part 4.2).

–In interdisciplinary research, scientific disciplines collaborate by addressing shared research questions and also by developing methods or theories together. The mid-range theory of promoting public understanding (cf. above, Part 1), for example, draws on integrated knowledge from linguistics, sociology and journalism studies. Throughout the Idée Suisse project, scientific disciplines collaborated to explain conditions and consequences of writing practices (writing research) in journalism (journalism studies) as a socially relevant (sociology) field of language use (applied linguistics).

–In transdisciplinary research, scientific disciplines collaborate with non-scientific fields in order to create shared knowledge and solve real-world problems, such as how public service media could and actually do promote public understanding. Identifying experienced journalists’ knowledge and making it available (through transformational processes such as generalization, exemplification, etc.) for an entire media organization, such as in the Idée Suisse project, requires the involvement and participation of practitioners throughout the project. Only then can professionals’ everyday theories be accessed and developed, leading to concerted, solution-oriented theory building.

The above three types of pluridisciplinarity are logically connected: multidisciplinary collaboration allows for the interdisciplinary developments which are needed for transdisciplinary solutions to practical problems. Solving problems such as promoting public understanding in a multilingual and multicultural country usually requires the knowledge of more than one scientific discipline.

3Epistemological interests: The example of linguistics of newswriting

Compared to theoretical or applied linguistics in general, media linguistics is a narrow subdiscipline. However, upon closer view it still addresses a huge variety of research fields. Investigating language change in the context of news media is quite different from analyzing media interviews. The production of news is yet another research field, with specific research questions, methods, and theoretical approaches. It is the application field of the linguistics of newswriting.

In other words, the linguistics of newswriting is the area within media linguistics that investigates the linguistically-based practices of professional news production (e. g., Perrin 2003; Van Hout/Jacobs 2008; Perrin 2013), such as in the LEBA case. The social setting that the linguistics of newswriting is interested in is the newsroom. The relevant contextual resources are the global and local newsflows, media organizations, and public discourse (e. g., Machin/Niblock 2006; Van Dijk 2001).

The key language users in the linguistics of newswriting are the journalists and editors as individuals and editorial teams or media organizations as collectives. They are in close contact with sources and in permanent indirect contact with their audiences. Social media accelerate and intensify interaction between these agent groups.

The linguistic activity highlighted in the linguistics of newswriting is collaborative writing. In a narrow understanding, writing is limited to the production of written language. In a broader sense, it encompasses all linguistically-based editing at the interface of text, sound and pictures. In addition, writing processes include reading phases, e. g., reading source texts.

All these processes take time. Therefore, the linguistics of newswriting considers the dynamics of text production. In a large timeframe, workflows in the newsroom are analyzed. In a medium timeframe, writing sessions to produce a particular news piece are investigated. In a narrow timeframe, the focus is on single decisions and their consequences during the writing process, such as the change from “express” to “tranquille” in the LEBA case.

Guided by practice, the linguistics of newswriting clarifies and solves problems of media practice with linguistic tools. In doing so, it also assesses the scope of the theories applied. The LEBA case, for example, has shown how an experienced journalist as a “reflective practitioner” (cf. Schön 1983) used a leitmotif to bridge policy and market expectations. He acted according to the mid-range theory of promoting public understanding. Exploiting such findings to solve practical problems requires knowledge transformation.

As an object of knowledge generation and transformation in research projects, newswriting is shaped by the epistemological interests of the disciplines involved. Depending on epistemological interests, it has been conceptualized, for example, as language use (Part 3.1), as writing at work (3.2), or as providing media content (3.3). The gap left by the three disciplines is the analysis of journalistic writing activities in context (4).

3.1Newswriting as language use

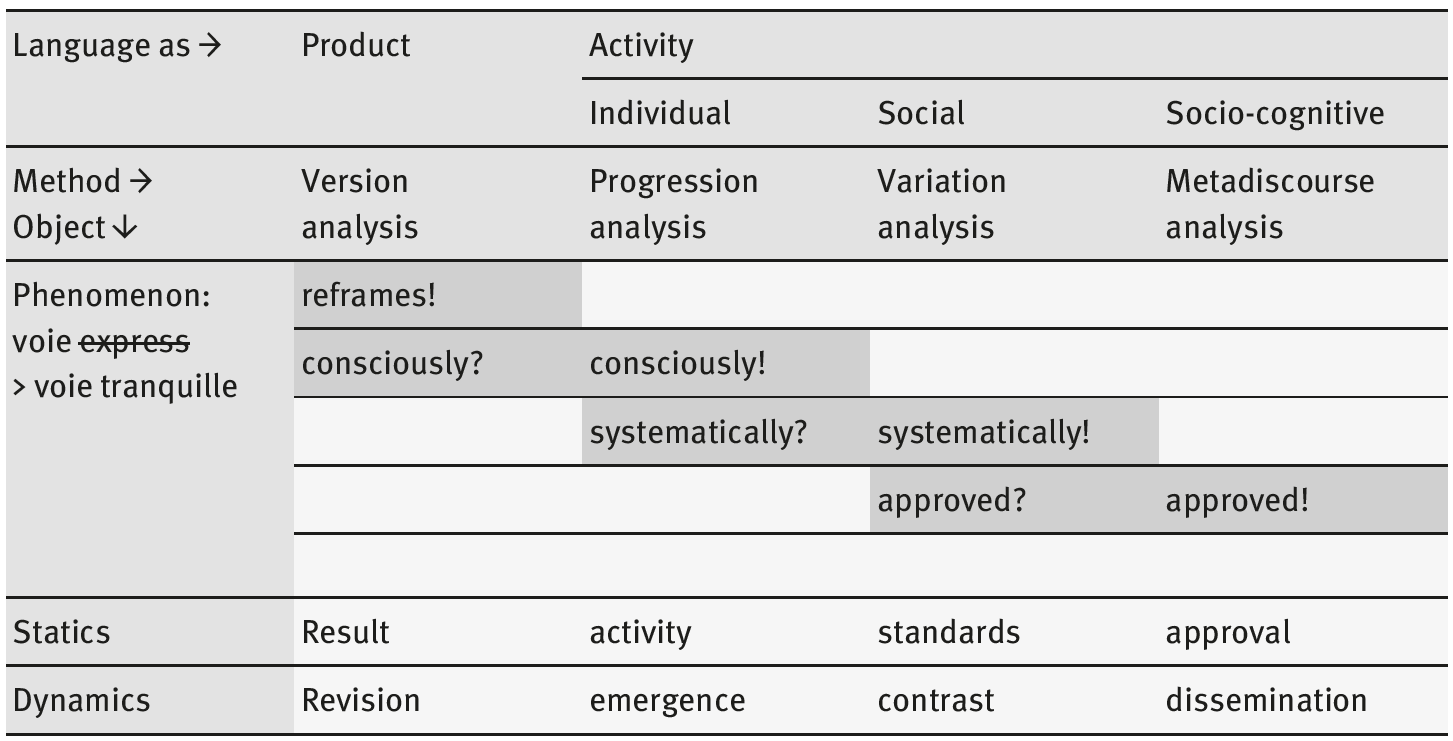

Researching language use means first and foremost examining stretches of verbal signs. They are the result of language use and form the basis for new language use. That is how language production, products and comprehension interact as “structured social contexts within which people seek to pursue their interests” (Sealey/Carter 2004, 18). The processes of language use can be investigated as individual cognitive activity, as social activity, or as socio-cognitive activity (Fig. 4).

For the leitmotif and the quotes in the LEBA case, this fourfold approach to language (e. g., Brumfit 2001, 55s.; Cicourel 1975; Filliettaz 2002; Leont’ev 1971; Vygotsky 1978) means:

–As stretches of language used, the quotes of the leitmotif appear in a news piece and are implicitly or explicitly related to former texts and contexts. Whereas the audience can see and hear where the quotes come from, most of them will not link the tranquil way to express way, which is what the boat connection is called in the region the item reports on.

–As cognitively based activity, the use of the leitmotif provides evidence of the journalist’s knowledge about dramaturgy, stereotypes, metaphors, and the region his item covers.

–As a socially-based activity, it shows that other journalists reproduce narratives and stereotypes, in this case about the violence in Lebanon.

–As an individually reflected socio-cognitive activity, finally, the leitmotif and the approval of it in the subsequent newsroom conference show how individuals can willingly vary or even change the narratives reproduced in newsrooms and societies.

3.2Newswriting as writing at work

Writing research conceptualizes writing as the production of texts, as cognitive problem solving (e. g., Cooper/Matsuhashi 1983), and as the collaborative practice of social meaning making (e. g., Burger 2006; Gunnarsson 1997; Lillis 2013; Prior 2006). The present state of research (e. g., Jakobs/Perrin 2014) results from paradigm shifts (e. g., Schultz 2006) including a first one from products to processes and a second one from the lab to the field.

–In a first paradigm shift, the focus of interest moved from the product to the process. Researchers started to go beyond final text versions and authors’ subjective reports about their writing experience (e. g., Hay 1993; Hodge 1979; Pitts 1982). Draft versions from different stages in a writing process were compared. Manuscripts were analyzed for traces of revision processes, such as cross-outs and insertions. This approach is still practiced in the field of literary writing, where archival research reveals the genesis of masterpieces (e. g., Bazerman 2008; Grésillon 1997).

–A second paradigm shift took research from the laboratory to “real life” (cf. Van der Geest 1996). Researchers moved from testing subjects with experimental tasks (e. g., Rodriguez/Severinson-Eklundh 2006) to workplace ethnography (e. g., Bracewell 2003), for example to describe professionals’ writing expertise (e. g., Beaufort 2005, 210). Later, ethnography was complemented by recordings of writing activities (e. g., Latif 2008), such as keylogging. The first multimethod approach that combined ethnography and keylogging at the workplace was progression analysis (cf. Part 4.1).

Writing research in the field of journalism sees newswriting as a reproductive process in which professionals contribute to “glocalized” (cf. Khondker 2004) newsflows by transforming source texts into public target texts, such as with the protesters’ posters and spoken utterances in the LEBA case (cf. above, Fig. 1). This happens at collaborative digital workplaces (e. g., Hemmingway 2007), in highly standardized formats and timeframes, and in recursive phases such as goal setting, planning, formulating, revising, and reading. Conflicts between routine and creativity, or speed and accuracy, are to be expected.

Based on such knowledge from writing research, writing education develops contextualized models of good writing practice, evaluates writing competence according to these models, and designs writing courses (e. g., Jakobs/Perrin 2008; Jones/Stubbe 2004; Olson 1987; Surma 2000).

3.3Newswriting as providing content for journalistic media

Communication and media studies foreground the media aspect of newswriting and reflect on the nature of the media concept in general. In a very broad view, many things can serve as a medium in communication: a sound wave carrier such as the air, a status symbol such as a car, or a system of signs such as the English language. In a stricter sense, a medium is a technical means or instrument to produce, store, reproduce, and transmit signs. However, this definition is still very broad. Media could mean all technical communication media such as postcards, the intranet, and even a public address system. Every form of communication except face-to-face conversations uses such technical tools.

–Media in the sense used here means news media. A news medium is a technical means used to produce and publish communication offers of public importance under economic conditions (e. g., Luhmann 21996). With this focused media concept, media linguistics refers to an independent and socially relevant field of language application, similar to forensic, clinical, or organizational linguistics. News medium is socially, economically, and communicatively more strictly defined than medium.

–Communication offers of public importance contribute to the production of public knowledge and understanding in societies whose “institutions of opinion” (cf. Myers 2005) reach far. Abandoning the stereotype of violent people in Lebanon, and realizing that demonstrations there can be tranquil and peaceful, such as in the LEBA case, fosters social understanding in a regionally (e. g., Androutsopoulos 2010) and globally (e. g., Blommaert 2010) connected world.

–Economic conditions means the obligation to create value as a “constrained author” (cf. Reich 2010) in work-sharing, technology-based (e. g., Pavlik 2000; Plesner 2009), and routinized (e. g., Berkowitz 1992) production processes (e. g., Baisnée/Marchetti 2006). The protesters’ quotes go through an intertextual chain of economic value production. At each station, journalists select source materials, revise them, and sell them to new addressees (Fig. 1).

–To publish means the professional activity of disseminating “content” (e. g., Carpentier/De Cleen 2008) outside of the production situation, to audiences unknown as individuals. The “Téléjournal” newsroom addresses an audience that can only be described statistically, using sampling techniques and projections.

4Methods: Combining perspectives on language use

When focusing on newswriting, media linguistics needs research methods to generate data about writing activities in complex contexts. The next sections present the four research methods applied in the Idée Suisse and related research projects, using them as examples of how to investigate newswriting practices as windows onto cognitive and societal structures and processes. These methods are: version analysis (Part 4.1), progression analysis (4.2), variation analysis (4.3), and metadiscourse analysis (4.4). In the Idée Suisse and similar projects, such methods are often triangulated in a multimethod approach (4.5).

4.1Tracking intertextual chains with version analysis

Linguistics investigates first and foremost stretches of language, linguistic products (e. g., McCarthy 2001, 115). From this product perspective (cf. above, Part 3.1), a media linguistics that focuses on what is special in newswriting will emphasize the intertextual chains within news flows: new texts are quickly and constantly created from earlier ones. What happens to the linguistic products in this process can be determined with version analysis.

Version analysis is the method of collecting and analyzing data in order to reconstruct the changes that linguistic features undergo in intertextual chains. The basis for comparing versions is text analysis. Version analyses trace linguistic products and elaborate on the changes in text features from version to version throughout intertextual chains. The quotes from the protesters in the LEBA item, for example, have been serially processed by at least five stations of intertextual reporting and, at the same time, of economic value production (Part 1.1). Some prominent medialinguistic studies draw on version analyses to reveal how news changes throughout the intertextual chains (e. g., Van Dijk 1988; Bell 1991, 56ss.; Luginbühl et al. 2002; Robinson 2009; Lams 2011).

A frequent variant of version analysis compares text versions before and after revision processes. Newswriting analyses can contrast, for example, text versions at four production states: after drafting, after the journalist’s office sessions, after video editing, and after speaking the news in the booth. A minimal, non-comparative variant of version analysis is the text analysis of a single version, with implicit or explicit reference to other versions that were not explicitly analyzed (e. g., Ekström 2001). This variant of version analysis is widespread in the framework of critical discourse analysis (Van Dijk 2001; cf. also critiques by Stubbs 1997 or Widdowson 2000).

Comparing various versions of finished texts is sufficient to gain knowledge about how texts are adapted from version to version. However, version analysis fails to provide any information about whether the journalists were conscious of their actions when re-contextualizing or engaging in other practices of text production; whether the practices are typical of certain media with certain target audiences; or whether the issues associated with those practices are discussed and negotiated in the editorial offices. To generate such knowledge, additional methodological approaches are required.

4.2Tracing writing processes with progression analysis

Linguistics can treat language as an interface between situated activity and cognitive structures and processes. From this cognitive perspective (Part 3.1), a media linguistics interested in the particularities of newswriting will emphasize individuals’ language-related decisions inside and outside the newsrooms. What exactly do individual journalists do when they create customized items at the quick pace of media production? What are they trying to do, and why do they do it the way they do? This is what progression analysis captures.

Progression analysis is the multimethod approach of collecting and analyzing data in natural contexts in order to reconstruct text production processes as a cognitively controlled and socially anchored activity. It combines ethnographic observation, interviews, computer logging, and cue-based retrospective verbalizations to gather linguistic and contextual data. The approach was developed to investigate newswriting (e. g., Perrin 2003; Sleurs/Jacobs/Van Waes 2003; Van Hout/Jacobs 2008) and later transferred to other application fields of writing research, such as children’s writing processes (e. g., Gnach et al. 2007) and translation (e. g., Ehrensberger-Dow/Perrin 2009). With progression analysis, data are obtained and related on three levels.

Before writing begins, progression analysis determines through interviews and observations what the writing situation is (e. g., Quandt 2008) and what experience writers draw on to guide their actions. Important factors include the writing task, professional socialization, and economic, institutional, and technological influences on the work situation. In the Idée Suisse project, data on the self-perception of the journalists investigated were obtained in semi-standardized interviews about their psychobiography, primarily in terms of their writing and professional experience, and their workplace. In addition, participatory and video observations were made about the various kinds of collaboration at the workplace.

During writing, progression analysis records every keystroke and writing movement in the emerging text with keylogging (e. g., Flinn 1987; Lindgren/Sullivan 2006; Spelman Miller 2006) and screenshot recording programs (e. g., Degenhardt 2006; Silva 2012) that run in the background of the text editing programs the journalists usually use, for instance behind the user interfaces of the news editing system in the “Téléjournal” newsroom. The recording can follow the writing process over several workstations and does not influence the performance of the editing system or the journalist. It reveals changes made throughout a text production process, such as replacing “express” by “tranquille”.

When the writing is done, progression analysis records what the writers say about their activities. Preferably immediately after completing the writing process, writers view on the screen how their texts came into being. While doing so, they continuously comment on what they did when writing and why they did it. An audio recording is made of these cue-based retrospective verbal protocols (RVP). This level of progression analysis opens a window onto the mind of the writer. The question is what can be recognized through this window: certainly not the all of the decisions and only the decisions that the author actually made, but rather the decisions that an author could have made in principle (e. g., Camps 2003; Ericsson/Simon 1993; Hansen 2006; Levy/Marek/Lea 1996; Smagorinsky 2001). The RVP is transcribed and then encoded as the author’s verbalization of aspects of his or her language awareness: writing strategies, and conscious writing practices, such as using leitmotifs in a news item.

The data of these three stages complement each other to provide a multiperspective, vivid picture of the object of study. In sum, progression analysis allows researchers to consider all the revisions to the text as well as all the electronic resources accessed during the production process; to trace the development of the emerging media item; and, finally, to reconstruct collaboration at media workplaces from different perspectives. The main focus of progression analysis, however, is the individual’s cognitive and manifest processes of writing. Social structures such as public mandates, organizational routines, and editorial policies are reconstructed through the perspectives of the individual agents involved: the writers under investigation. If editorial offices or even media organizations are to be investigated with respect to how they produce their texts as a social activity, then progression analysis has to be supplemented by two other methods: variation analysis and metadiscourse analysis.

4.3Revealing audience design with variation analysis

Linguistics can treat language as an interface between situated activity and social structures and processes. From this social perspective (Part 3.1), a media linguistics interested in the particularities of newswriting will focus on how social groups such as editorial teams customize their linguistic products for their target audiences. Which linguistic means, e. g., which gradient of formality, does an editorial office choose for which addressees? This is what variation analysis captures.

Variation analysis is the method of collecting and analyzing text data to reconstruct the special features of the language of a certain discourse community. The basis for comparing versions is discourse analysis. Variation analyses investigate the type and frequency of typical features of certain language users’ productions in certain kinds of communication situations, such as newswriting for a specific audience. What variation analysis discerns is the differences between the language used in different situations by the same users (e. g., Koller 2004) or by various users in similar situations (e. g., Fang 1991; Werlen 2000).

In the Idée Suisse project, variation analyses show systematic differences between the three news programs investigated. The relation of item length and cuts, for example, document a higher pace of pictures in the French “Téléjournal” (4.5 sec. on average between visible cuts) than in the German “Tagesschau” (8.5 sec.) and “10 VOR 10” (7 sec.). Similarly, variation analyses can reveal whether language properties of the newscast “Tagesschau” and the newsmagazine “10 VOR 10”, competing in the same German television program of the Swiss public broadcaster, differ according to their program profiles.

Such broadly-based variation analysis is able to show the special features of the language used in certain communities or media. However, what the method gains in width compared with a method such as progression analysis, it loses in depth. Why a community prefers to formulate its texts in a certain way and not another cannot be captured by variation analysis. It would be possible to regain some of that depth by using a procedure that examines not only the text products, but also the institutionalized discourses connected with them – the comments of the community about its joint efforts.

4.4Investigating language policy making with metadiscourse analysis

Linguistics can treat language as an interface between situated activity and cognitive and social structures and processes. From this socio-cognitive perspective (Part 3.1), a media linguistics interested in the particularities of newswriting will focus on editorial metadiscourse such as quality control discourse at editorial conferences or negotiations between journalists, anchors, and cutters. What do the various stakeholders think about their communicational offers? How do they evaluate their activity in relation to policies – and how do they reconstruct and alter those policies?

Metadiscourse analysis is the method of collecting and analyzing data in order to reconstruct the socially- and individually-anchored (language) awareness in a discourse community. The basis for analyzing the metadiscourse of text production is conversation and discourse analysis.

Metadiscourse analyses investigate spoken and written communication about language and language use. This includes metaphors used when talking about writing (e. g., Gravengaard 2012; Levin/Wagner 2006), explicit planning or criticism of communication measures (e. g., Peterson 2001), the clarification of misunderstandings and conversational repair (e. g., Häusermann 2007), and follow-up communication by audiences (e. g., Klemm 2000). In all these cases, the participants’ utterances show how their own or others’ communicational efforts and offers have been perceived, received, understood, and evaluated. The analysis demonstrates how rules of language use are explicitly negotiated and applied in a community.

In the LEBA case, due to a computer crash, the journalist lacks the time to discuss his item with the cutter. In other case stories from the Idée Suisse project, however, cutters challenge the journalists’ ethics and aesthetics or appear as critical audience representatives. On a macro-level of the project, interviews and document analyses reveal policy makers’ and media managers’ contradictory evaluation of and expectations towards the broadcasters’ – and the journalists’ – ability to promote public understanding.

The focus of metadiscourse analysis, thus, scales up from negotiations about emerging texts at writers’ workplaces to organizational quality control discourse and related discussions in society at large. Integrating metadiscourse analyses extends the reach of progression analysis from a single writer’s micro activity to societal macrostructures.

4.5Combining perspectives with multimethod approaches

The four above approaches each capture overlapping facets of newswriting from their own perspectives, e. g., the source material, the work context, the thought patterns, the sequences of revisions in the writing process, the text products, the news programs, the editorial mission statement and policy, and the internal and external evaluation and development of norms. Within these facets, each approach has its own focus (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6 illustrates the interplay of the four methods by using the leitmotif example from the LEBA case where the journalist changes “voie express” to “voie tranquille” (cf. above, Part 1.2).

–A micro version analysis comparing the first and the last version of the corresponding sentence shows the difference: one word has changed. The researcher interprets this revision as a reframing of the boat’s speed and, in a wider context, of the activities the media item reports.

–However, only progression analysis provides evidence that the journalist consciously changed the word to use it as a leitmotif. Moreover, progression analysis indicates that this idea emerged when the experienced journalist was surprised by details from the source materials he carefully read and watched.

–A variation analysis contrasting processes and products by experienced and less experienced journalists then can reveal experience to be a strong predictor for success in handling critical situations and for results with a high potential to promote public understanding.

–A metadiscourse analysis, finally, can show whether the journalist’s emergent solution is approved in the following editorial conference, and whether it corresponds, on a macro-level, to the expectations of both media managers and policy makers. Such successful emergent solutions deserve to be disseminated through knowledge transformation measures.

The methodological discussion has shown that newswriting is accessible from four perspectives and that each perspective calls for suitable methods. Questions about cognitive practices, for instance, can only be addressed using insights into cognitive relationships; the same is true for social practices and their interactions. Investigating stretches of language in a “one size fits all approach” (Richardson 2007, 76) is not enough – it cannot explain what is special about journalistic news production (e. g., Philo 2007) and fails to reveal structures that “cannot be directly observed” (Ó Riain 2009, 294).

5Outcome: Adding value through knowledge transformation

Doing media linguistics in order to identify good practices, as in the LEBA case, only makes sense if stakeholders are interested in the resulting knowledge – and share their knowledge successfully (Part 5.1). Transforming and sharing knowledge between a scientific discipline, such as applied linguistics, and a professional discipline, such as journalism, requires different understandings of knowledge to be clarified. Theorists condense systematic knowledge into theories that allow for systematic contextualization and reflection (5.2). Professional knowledge, in contrast, is oriented towards practical solutions, but tends to suffer from a lack of overall perspective (5.3). Media linguistics aims at mapping the two approaches (5.4).

5.1Making tacit knowledge explicit

If applied linguistics wants to contribute to solving practical problems (e. g., AILA 2011), such as promoting public understanding in a context of contradictory expectations, it has to generalize empirical findings and formulate suggestions. Generalizing consists of, for example, translating experienced practitioners’ tacit knowledge into mid-range theories about what works under which conditions (cf. Pawson/Tilley 1997). Formulating suggestions, in reverse, consists of finding ways to help practitioners learn from others and from theory. This is what is termed knowledge transformation in applied research (e. g., Gibbons 1994; Wiesmann et al. 2008).

For such knowledge transformation, technical terms and practical formulations have been developed. The transformation terminology symbolizes, on a small scale, the value a change of perspective adds to both theory and practice: developing tools to ground the theoretically conceivable in empirical experience – and to open practice to the unfamiliar, unexpected, but basically conceivable.

Practical solutions emerge when experienced journalists tackle complex and unexpected problems in critical situations within their daily routines. In an organization such as the broadcaster in the Idée Suisse project, SRG SSR, such solutions are not part of explicit organizational knowledge that management and staff can draw on, but have to be developed based on tacit knowledge (e. g., Agar 2010; Polanyi 1966). Locating and transforming this knowledge for the whole of SRG SSR would augment the potential of organizational success in terms of both economic interests and public demands.

However, before micro findings from writing research at the workplace can be related to social findings, the organizational understandings have to be clarified (e. g., Kelly-Holmes 2010, 28ss.). This is what the Idée Suisse project did at the interface of its micro- and macro-analyses. Four approaches of framing the discrepancy between policy expectations and management positions were evaluated. The one considered most appropriate, the tacit knowledge frame, calls for organizational knowledge transformation. Such transformation draws on knowledge derived from the bottom of the organization.

5.2Framing divergence

In the Idée Suisse project, a contradiction that was identified served as a trigger for further research and knowledge transformation. The approach was based on assumptions developed in the framework of Transdisciplinary Action Research (e. g., Hirsch Hadorn et al. 2008; Jantsch 1972; Lewin 1951). A basic assumption in this framework is systemic congruence: an organization succeeds if it wants and is able to do what it has to do. In other words: An organization’s situated activity can only be internally functional (i.e., contribute to the organization’s survival and growth), if it also is externally functional (i.e., it meets environmental needs). This notion can be explained by contrasting the chosen tacit knowledge frame with its opposites: the hypocrisy frame, the consonance/dissonance frame, and the functional dysfunction frame (Fig. 7).

In the hypocrisy frame, organizations such as SRG SSR only survive due to their inner “hypocrisy” (cf. Brunsson 22002): these organizations are exposed to contradictory expectations from their environments. To survive, they have to respond to all of these contradictory expectations – with integrative talk but contradictory outputs, and with actions far removed from talk, provided by different, incongruently acting organizational units and roles. From an internal point of view, nothing needs to be changed, as long as no external stakeholder really commits the organization to doing what it is expected to do. However, public service media are being increasingly scrutinized by external stakeholders – conditions are less than ideal for SRG SSR to survive in the hypocrisy frame.

In the consonance/dissonance frame, all of the units and levels of an organization should focus on and reach the same target. In this frame, the frustration of the management in the face of the perceived gap between public mandate and market demands would be taken as failure: In its decisions and actions, the SRG SSR management more or less fails to do what it claims in its public relations statements and what it is expected to do. By being externally dysfunctional, it is also internally dysfunctional. The global interpretation of the divergent project findings from modules A and B would be failure – difficult, if not impossible to change. In this frame, the end of public service media and all other institutions experiencing similar tensions would simply be a matter of time. The fact that such institutions survive shows that the consonance/dissonance frame is too simplistic.

In the functional dysfunction frame, disappointing communication is seen as an excellent trigger for meta-communicative follow-up communication – and communication is what communities are built on. The apparent paradox, in other words, is that even by violating public expectations, the media in general and public media in particular contribute to public discourse and integration. From an external point of view, nothing would have to be changed, even though it may be less than motivating to work for a media organization whose output quality does not matter. In a wider context of “deliberative” democracies (cf. Habermas 1992), media are considered to offer reasonable communicational contributions to public discourse (e. g., Schudson 2008). By such a rationale, quality matters – and is enabled and ensured by public funding. Limiting public media’s role to functional dysfunction would fall short.

In the tacit knowledge frame, at least single exponents succeed in doing what the organization has to do. Through situated activity in seemingly contradictory social settings, they develop emergent solutions bridging internal with external expectations. For the case of SRG SSR, this could mean that exponents such as experienced journalists develop and apply sophisticated strategies, practices, and routines of language use that meet both organizational and public needs at the same time. In doing so, they fill the gap left by the management. Sharing their knowledge would benefit the whole organization in bridging market pressure and policy expectations.

5.3Macro-level recommendations

In a tacit knowledge frame, management can foster workplace conditions that facilitate knowledge transformation instead of constraining it. From the Idée Suisse findings, the project team drew the following five macro-level recommendations for policy makers and media managers.

–Plan dynamically. Not surprisingly, a naïve view of language planning as topdown implementation of policies falls short. Setting language policy – language “policing” – is better understood as the interplay of policy and practice (cf. Blommaert et al. 2009, 203; Kelly-Holmes/Moriarty/Pietikäinen 2009, 228). Preferred language use is oriented to shared goals and grounded in shared attitudes, knowledge, and methods. More surprisingly, neither media policy-makers nor media management seem to be aware of these problems related to attempts at top-down policy making. Frustration on both sides – mandate is unrealistic vs. SRG SSR is lazy – could be overcome by a more integrative, dynamic view of policy making.

–Integrate practitioners. Practicing language policy making dynamically and comprehensively means integrating those involved, as stakeholders of both the problems and the solutions. As could be shown in the Idée Suisse project, experienced journalists contribute to promoting public understanding by emergent solutions based on their tacit knowledge. Locally, they prove that public mandate and market demands can be bridged with appropriate attitudes, knowledge, and methods. Knowing more about their approaches could help on three levels: first, it enables other practitioners to learn from their experience in the organization; second, it allows the management to develop and radiate a positive, non-hypocritical view of the mandate; third, it shows the organization acting a public service provider; and finally, it helps media policy to legitimize public funding in the public interest.

–Foster emergent solutions. Media policy-makers and media management need not know in detail how the mandate can be fulfilled. As one of the expert interviewees said, promoting public understanding starts in the newsrooms. However, there is no justification for media policy-makers and management not to know how to foster this creative approach to demanding challenges in the organization and particularly in the newsrooms. This is where research can make a contribution.

–Transform knowledge. If existing knowledge has not yet been released, then knowledge experts can help to identify and transform it. Researchers at the interface of applied linguistics and research frameworks such as ethnography and Transdisciplinary Action Research are experienced at revealing “what works for whom in what circumstances” (e. g., Sealey/Carter 2004, 197, drawing on Pawson/Tilley 1997), on reflecting on the “transferability” of such situated knowledge (cf. Denzin/Lincoln 22000, 21s.), and at returning the knowledge to the organization in understandable and sustainable generalized forms, for example as ethnographically-based narratives and typologies of critical situations and good practices.

–Scale up. If a knowledge transformation approach is promising on the level of internal multilingualism (i.e., promoting public understanding between societal groups such as the politically informed vs. uninformed), it is even more necessary on the level of external multilingualism (i.e., communication and understanding across linguistic regions). The interviews from the Idée Suisse project’s macro-level modules A and B show that the SRG SSR management has been disappointed by practically all organizational measures taken at this level. For many media managers, practicing (external) multilingualism means wasting economic resources and frightening the audience away. Again, more subtle, case-sensitive solutions from the ground floor are in high demand – even more so in the face of media convergence and increasing multilingualism in glocalized and translocal newsflows (e. g., Perrin 2011) as well as local diversity (e. g., Kelly-Holmes/Moriarty/Pietikäinen 2009, 240).

Thus, the conditions for emergent solutions in newsteams need to be systematically improved top-down by media policy and media management, and the tacit knowledge involved must be systematically identified bottom-up at the workplaces and then made available to the whole organization. Based on these recommendations, the Idée Suisse stakeholders working in media policy, media management, media practice, and media research have established follow-up measures for knowledge transformation, such as systematic organizational development, consulting, coaching, and training.

5.4Conclusion: Providing evidence that the process perspective matters

In this chapter, the mandate of promoting public understanding has illustrated the social relevance of newswriting as a driver of public discourse and societal integration. News that reaches diverse audiences simultaneously can foster discourse across social and linguistic boundaries. How to do this was the research question of the Idée Suisse project used as an example throughout the chapter – and is a key question for media linguistics. It is merely by facing such language-related problems that we can add social value and provide evidence that research in general and laborious approaches such as process analyses matter.

6References

Agar, Michael H. (2010), On the ethnographic part of the mix. A multi-genre tale of the field, Organizational Research Methods 13:2, 286–303.

AILA (2011), What is AILA, <http://www.aila.info/en/about.html> (04.11.2016).

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2010), The study of language and space in media discourse, in: Peter Auer/Jürgen E. Schmidt (edd.), Language and space. An international handbook of linguistic variation, vol. 1, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, 740–759.

Baisnée, Olivier/Marchetti, Dominique (2006), The economy of just-in-time television newscasting: Journalistic production and professional excellence at Euronews, Ethnography 7:1, 99–123.

Bazerman, Charles (2008), Theories of the middle range in historical studies of writing practice, Written Communication 25:3, 298–318.

Beaufort, Anne (2005), Adapting to new writing situations. How writers gain new skills, in: Eva-Maria Jakobs/Katrin Lehnen/Kirsten Schindler (edd.), Schreiben am Arbeitsplatz, Wiesbaden, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 201–216.

Bell, Allan (1991), The language of news media, Oxford, Blackwell.

Bell, Allan/Garrett, Peter (edd.) (1998), Approaches to media discourse, Oxford, Blackwell.

Berkowitz, Daniel (1992), Non-routine news and newswork. Exploring a what-a-story, Journal of Communication 42:1, 82–94.

Blommaert, Jan (2010), The sociolinguistics of globalization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert, Jan, et al. (2009), Media, multilingualism and language policing. An introduction, Language Policy 8:3, 203–207.

Boyd-Barret, Oliver (1994), Language and media, in: David Graddol/Oliver Boyd-Barret (edd.), Media texts: Authors and readers, Clevedon, Multilingual Matters, 22–39.

Bracewell, Robert J. (2003), Tasks, ensembles, and activity. Linkages between text production and situation of use in the workplace, Written Communication 20:4, 511–559.

Brumfit, Christopher (2001), Individual freedom in language teaching. Helping learners to develop a dialect of their own, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Brunsson, Nils (22002), The organization of hypocrisy. Talk, decisions and actions in organizations, Oslo, Abstrakt forlag/Copenhagen Business School Press.

Burger, Marcel (2006), Le discours des médias comme forme de pratique sociale: l’enjeu des débats télévisés, in: Roger Blum (ed.), Wes Land ich bin, des Lied ich sing: Medien und Politische Kultur, Bern, Institut für Medienwissenschaften, 287–298.

Burger, Marcel (2008), Une analyse linguistique des discours médiatiques, in: Marcel Burger (ed.), L’analyse linguistique des discours des médias: théories, méthodes en enjeux. Entre sciences du langage et sciences de la communication et des médias, Québec, Nota Bene, 7–38.

Camps, Joaquim (2003), Concurrent and retrospective verbal reports as tools to better understand the role of attention in second language tasks, International Journal of Applied Linguistics 13:2, 201–221.

Candlin, Christopher N./Sarangi, Srikant (2004), Making applied linguistics matter, Journal of Applied Linguistics 1:1, 1–8.

Carpentier, Nico/De Cleen, Benjamin (edd.) (2008), Participation and media production. Critical reflections on content creation, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Cicourel, Aaron Victor (1975), Discourse and text. Cognitive and linguistic process in studies of social structures, Versus 12:2, 33–84.

Cooper, Charles/Matsuhashi, Ann (1983), A theory of the writing process, in: Margaret Martlew (ed.), The psychology of written language, Chichester et al., Wiley, 3–39.

Cotter, Colleen (2010), News talk. Shaping the language of news, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Coupland, Nikolas (2014), Language change, social change, sociolinguistic change: A meta-commentary, Journal of Sociolinguistics 18:2, 277–286.

Degenhardt, Marion (2006), CAMTASIA and CATMOVIE. Two digital tools for observing, documenting and analysing writing processes of university students, in: Luuk Van Waes/Mariëlle Leijten/Chris Neuwirth (edd.), Writing and digital media, Amsterdam/Boston/London, Elsevier, 180–186.

Denzin, Norman K./Lincoln, Yvonna S. (22000), Introduction. The discipline and practice of qualitative research, in: Norman K. Denzin/Yvonna S. Lincoln (edd.), Handbook of qualitative research, London, Sage, 1–28.

Ehrensberger-Dow, Maureen/Perrin, Daniel (2009), Capturing translation processes to access metalinguistic awareness, Across Languages and Cultures 10:2, 275–288.

Ekström, Mats (2001), Politicians interviewed on television news, Discourse & Society 12:5, 563–584.

Ericsson, K. Anders/Simon, Herbert A. (1993), Protocol analysis. Verbal reports as data, rev. ed., Cambridge, MIT Press.

Fairclough, Norman (1995), Media discourse, London, Arnold.

Fang, Irving (1991), Writing style differences in newspaper, radio and television news, Minnesota, Center for Interdisciplinary Studies of Writing, University of Minnesota.

Filliettaz, Laurent (2002), La parole en action. Éléments de pragmatique psycho-sociale, Québec, Nota Bene.

Flinn, Jane Z. (1987), Case studies of revision aided by keystroke recording and replaying software, Computers and Composition 5:1, 31–44.

Fowler, Roger (1991), Language in the news, London/New York, Routledge.

Gibbons, Michael (1994), The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies, London, Sage.

Gnach, Aleksandra, et al. (2007), Children’s writing processes when using computers. Insights based on combining analyses of product and process, Research in Comparative and International Education 2:1, 13–28.

Gravengaard, Gitte (2012), The metaphors journalists live by. Journalists’ conceptualisation of newswork, Journalism 13:8, 1064–1082.

Grésillon, Almuth (1997), Slow: work in progress, Word & Image 13:2, 106–123.

Gunnarsson, Britt-Louise (1997), The writing process from a sociolinguistic viewpoint, Written Communication 14:2, 139–188.

Habermas, Jürgen (1992), Drei normative Modelle der Demokratie: Zum Begriff deliberativer Demokratie, in: Herfried Münkler (ed.), Die Chancen der Freiheit. Grundprobleme der Demokratie, München/Zürich, Piper, 11–24.

Hansen, Gyde (2006), Retrospection methods in translator training and translation research, Journal of Specialised Translation 5, 2–40.

Häusermann, Jürg (2007), Zugespieltes Material. Der O-Ton und seine Interpretation, in: Harun Maye/Cornelius Reiber/Nikolaus Wegmann (edd.), Original / Ton. Zur Mediengeschichte des O-Tons, Konstanz, UVK, 25–50.

Hay, Louis (1993), Les manuscrits au laboratoire, in: Louis Hay (ed.), Les Manuscrits des écrivains, Paris, Hachette (CNRS Éditions), 122–137.

Hemmingway, Emma (2007), Into the newsroom. Exploring the digital production of regional television news, London, Routledge.

Hirsch Hadorn, Gertrude, et al. (2008), The emergence of transdisciplinarity as a form of research, in: Gertrude Hirsch Hadorn et al. (edd.), Handbook of transdisciplinary research, Berlin, Springer, 19–39.

Hodge, Bob (1979), Newspapers and communities, in: Roger Fowler et al. (edd.), Language and control, London, Routledge, 157–174.

Jakobs, Eva-Maria/Perrin, Daniel (2008), Training of writing and reading, in: Gert Rickheit/Hans Strohner (edd.), The Mouton-De Gruyter handbooks of applied linguistics. Communicative competence, vol. 1, New York, de Gruyter, 359–393.

Jakobs, Eva-Maria/Perrin, Daniel (2014), Introduction and research roadmap. Writing and text production, in: Eva-Maria Jakobs/Daniel Perrin (edd.), Handbook of writing and text production, vol. 10, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, 1–24.

Jantsch, Erich (1972), Towards interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in education and innovation, in: Leo Apostel et al. (edd.), Interdisciplinarity: Problems of teaching and research in universities, Paris, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 97–121.

Jones, Deborah/Stubbe, Maria (2004), Communication and the reflective practitioner. A shared perspective from sociolinguistics and organisational communication, International Journal of Applied Linguistics 14:2, 185–211.

Kelly-Holmes, Helen (2010), Rethinking the macro-micro relationship. Some insights from the marketing domain, International Journal of the Sociology of Language 202, 25–39.

Kelly-Holmes, Helen/Moriarty, Máiréad/Pietikäinen, Sari (2009), Convergence and divergence in Basque, Irish and Sámi media language policing, Language Policy 8:3, 227–242.

Khondker, Habibul Haque (2004), Glocalization as Globalization. Evolution of a sociological concept, Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology 1:2, 12–20.

Klemm, Michael (2000), Zuschauerkommunikation. Formen und Funktionen der alltäglichen kommunikativen Fernsehaneignung, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang.

Koller, Veronika (2004), Businesswomen and war metaphors: “Possessive, jealous and pugnacious”?, Journal of Sociolinguistics 4:1, 3–22.

Kress, Gunther (1986), Language in the media. The construction of the domains of public and private, Media, Culture & Society 8:4, 395–419.

Lacey, Kate (2013), Listening publics. The politics and experience of audiences in the media age, Cambridge, Polity Press.

Lams, Lutgard (2011), Newspapers’ narratives based on wire stories. Facsimiles of input?, Journal of Pragmatics 43:7, 1853–1864.

Latif, Muhammed M. (2008), A state-of-the-art review of the real-time computer-aided study of the writing process, International Journal of English Studies 8:1, 29–50.

Leont’ev, Aleksej A. (1971), Sprache, Sprechen, Sprechtätigkeit, Stuttgart et al., Kohlhammer.

Levin, Tamar/Wagner, Till (2006), In their own words: Understanding student conceptions of writing through their spontaneous metaphors in the science classroom, Instructional Science 34:3, 227–278.

Levy, C. Michael/Marek, J. Pamela/Lea, Joseph (1996), Concurrent and retrospective protocols in writing research, in: Gert Rijlaarsdam/Huub Van den Bergh/Michael Couzijn (edd.), Theories, models and methodology in writing research, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 542–556.

Lewin, Kurt (1951), Field theory in social science, New York, Harper Row.

Lillis, Theresa (2013), The sociolinguistics of writing, Edinburg, Edinburgh University Press.

Lindgren, Eva/Sullivan, Kirk (2006), Analysing online revision, in: Kirk Sullivan/Eva Lindgren (edd.), Computer keystroke logging and writing. Methods and applications, Amsterdam, Elsevier, 157–188.

Lüger, Heinz-Helmut (1977), Journalistische Darstellungsformen aus linguistischer Sicht. Untersuchungen zur Sprache der französischen Presse mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des “Parisien libéré”, Dissertation, Freiburg im Breisgau.

Luginbühl, Martin, et al. (2002), Medientexte zwischen Autor und Publikum. Intertextualität in Presse, Radio und Fernsehen, Zürich, Seismo.

Luhmann, Niklas (21996), Die Realität der Massenmedien, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag.

Machin, David/Niblock, Sarah (2006), News production. Theory and practice, London, Routledge.

Marchetti, Dominique/Ruellan, Denis (2001), Devenir journalistes. Sociologie de l’entrée dans le marché du travail, Paris, Documentation française.

McCarthy, Michael (2001), Issues in applied linguistics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Messner, Marcus/DiStaso, Marcia W. (2008), The source cycle. How traditional media and weblogs use each other as sources, Journalism Studies 9:3, 447–463.

Meyerhoff, Miriam (2003), “But is it linguistics?” Breaking down boundaries, Journal of Sociolinguistics 7:1, 65–77.

Montgomery, Martin (2007), The discourse of broadcast news: A linguistic approach, London, Routledge.

Myers, Greg (2005), Applied linguists and institutions of opinion, Applied Linguistics 26:4, 527–544.

Ó Riain, Sean (2009), Extending the ethnographic case study, in: David Byrne/Charles C. Ragin (edd.), The SAGE handbook of case-based methods, London, Sage, 289–306.

Olson, Lyle D. (1987), Recent composition research is relevant to newswriting, Journalism Educator 42:3, 14–18.

Pavlik, John (2000), The impact of technology on journalism, Journalism Studies 1:2, 229–237.

Pawson, Ray/Tilley, Nick (1997), Realistic evaluation, London, Sage.

Perrin, Daniel (2003), Progression analysis (PA). Investigating writing strategies at the workplace, Journal of Pragmatics 35:6, 907–921.

Perrin, Daniel (2011), Language policy, tacit knowledge, and institutional learning. The case of the Swiss national broadcast company, Current Issues in Language Planning 4:2, 331–348.

Perrin, Daniel (2012), Stancing. Strategies of entextualizing stance in newswriting. Discourse, Context & Media 1:2–3, 135–147.

Perrin, Daniel (2013), The linguistics of newswriting, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, Benjamins.

Perrin, Daniel/Grésillon, Almuth (2014), Methodology. From speaking about writing to tracking text production, in: Daniel Perrin/Eva-Maria Jakobs (edd.), Handbook of writing and text production, vol. 10, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter, 79–114.

Peterson, Mark Allen (2001), Getting to the story. Unwriteable discourse and interpretive practice in American journalism, Anthropological Quarterly 74:4, 201–211.

Philo, Greg (2007), Can discourse analysis successfully explain the content of media and journalistic practice?, Journalism Studies 8:2, 175–196.

Pitts, Beverley J. (1982), Protocol analysis of the newswriting process, Newspaper Research Journal 4, 12–21.

Plesner, Ursula (2009), An actor-network perspective on changing work practices: Communication technologies as actants in newswork, Journalism 10:5, 604–626.

Polanyi, Michael (1966), The tacit dimension, Garden City (NY), Doubleday.

Prior, Paul (2006), A sociocultural theory of writing, in: Charles A. MacArthur/Steve Graham/Jill Fitzgerald (edd.), Handbook of writing research, New York, Guilford, 54–66.

Quandt, Thorsten (2008), News tuning and content management. An observation study of old and new routines in German online newsrooms, in: Chris Paterson/David Domingo (edd.), Making online news. The ethnography of new media production, New York, Lang, 77–97.

Rampton, Ben (2008), Disciplinary mixing: Types and cases, Journal of Sociolinguistics 12:4, 525–531.

Reich, Zvi (2010), Constrained authors: Bylines and authorship in news reporting, Journalism 11:6, 707–725.

Richardson, John E. (2007), Analysing newspapers. An approach from critical discourse analysis, Houndmills, Palgrave.

Robinson, Sue (2009), A chronicle of chaos. Tracking the news story of hurricane Katrina from The Times-Picayune to its website, Journalism 10:4, 431–450.

Rodriguez, Henry/Severinson-Eklundh, Kerstin (2006), Visualizing patterns of annotation in document-centered collaboration on the web, in: Luuk Van Waes/Mariëlle Leijten/Chris Neuwirth (edd.), Writing and digital media, Amsterdam/Boston/London, Elsevier, 131–144.

Salmon, Christian (2007), Storytelling, la machine à fabriquer des histoires et à formater les esprits, Paris, La Découverte.

Sarangi, Srikant/Van Leeuwen, Theo (2003), Applied linguistics and communities of practice. Gaining communality or losing disciplinary autonomy?, in: Srikant Sarangi/Theo Van Leeuwen (edd.), Applied linguistics and communities of practice, London, Continuum, 1–8.

Schön, Donald A. (1983), The reflective practitioner. How professionals think in action, New York, Basic Books.

Schudson, Michael (2008), Why democracies need an unlovable press, Cambridge, Polity Press.

Schultz, Katherine (2006), Qualitative research on writing, in: Charles A. MacArthur/Steve Graham/Jill Fitzgerald (edd.), Handbook of writing research, New York, Guilford, 357–373.

Sealey, Alison/Carter, Bob (2004), Applied linguistics as social science, London/New York, Continuum.

Silva, Mary Lourdes (2012), Camtasia in the classroom. Student attitudes and preferences for video commentary or Microsoft Word comments during the revision process, Computers and Composition 29:1, 1–22.

Sleurs, Kim/Jacobs, Geert/Van Waes, Luuk (2003), Constructing press releases, constructing quotations: A case study, Journal of Sociolinguistics 7:2, 135–275.

Smagorinsky, Peter (2001), Rethinking protocol analysis from a cultural perspective, Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 21, 233–245.

Spelman Miller, Kristvan (2006), Keystroke logging. An introduction, in: Kirk Sullivan/Eva Lindgren (edd.), Computer keystroke logging and writing. Methods and applications, Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1–9.

Stubbs, Michael (1997), Critical comments on Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), in: Ann Ryan/Alison Wray (edd.), Evolving models of language, Clevedon, Multilingual Matters, 100–116.

Studer, Patrick (2008), Historical corpus stylistics. Media, technology and change, London, Continuum.

Surma, Anne (2000), Defining professional writing as an area of scholarly activity, Text 4:2, <http://www.textjournal.com.au/oct00/surma.htm> (04.11.2016).

Van der Geest, Thea (1996), Studying “real life” writing processes. A proposal and an example, in: C. Michael Levy/Sarah Ransdell (edd.), The science of writing. Theories, methods, individual differences, and applications, Mahwah, Erlbaum, 309–322.

Van Dijk, Teun A. (1988), News analysis. Case studies of international and national news in the press, Hillsdale/London, Erlbaum.

Van Dijk, Teun A. (2001), Multidisciplinary CDA. A plea for diversity, in: Ruth Wodak/Michael Meyer (edd.), Methods of critical discourse analysis, Los Angeles, Sage, 95–120.

Van Hout, Tom/Jacobs, Geert (2008), News production theory and practice. Fieldwork notes on power, interaction and agency, Pragmatics 18:1, 59–86.

Vygotsky, Lew S. (1978), Mind in society. The developments of higher psychological processes, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Werlen, Iwar (2000), “Zum Schluss das Wetter”. Struktur und Variation von Wetterberichten im Rundfunk, in: Jürg Niederhauser/Stanislaw Szlek (edd.), Sprachsplitter und Sprachspiele, Bern et al., Lang, 155–170.

Widdowson, Henry G. (2000), On the limitations of linguistics applied, Applied Linguistics 21:1, 3–35.

Wiesmann, Urs, et al. (2008), Enhancing transdisciplinary research. A synthesis in fifteen propositions, in: Gertrude Hirsch Hadorn et al. (edd.), Handbook of transdisciplinary research, Berlin, Springer, 433–441.