Chapter Three

Ethical Dilemmas, Sources and Their Resolutions

WHAT IS AN ETHICAL DILEMMA?

An ethical dilemma is a moral situation in which a choice has to be made between two equally undesirable alternatives. Dilemmas may arise out of various sources of behaviour or attitude, as for instance, it may arise out of failure of personal character, conflict of personal values and organizational goals, organizational goals versus social values, etc. A business dilemma exists when an organizational decision maker faces a choice between two or more options that will have various impacts on (a) the organization’s profitability and competitiveness, and (b) its stakeholders. “In situations of this kind, one must act out of prudence to take a better decision. As we can see, many of these ethical choices involve conflicts of values”. According to Louis Alvin Day,1 these conflicts can arise on different levels. “Sometimes, there is an inner conflict involving the application of general societal values”. A production manager, when asked to produce a commodity by his company may face an ethical dilemma, when he knows that it will harm the large number of consumers who buys and uses the same. Sometimes, there may arise a conflict between general societal values, as in the case of minimizing harm to others and professional values. For example, news reporters may willingly hide a sacrilege a mob committed in a place of worship if they feared that it would result in a communal frenzy and mass slaughter. “Ethical dilemmas involve problem solving situations in which decision rules are often vague or in conflict”.2 The outcome of an ethical decision cannot be predicted with any degree of accuracy or precision. We cannot be sure whether we have made the right decision; nor can any one tell us so. There is neither a magic formula nor a software available to find a solution to this problem. Even the most astute businesspersons do commit ethical mistakes while deciding business issues. In such cases, people have no other alternative but to think well and deeply before they make decisions and once decided, to take the responsibility for such decisions.

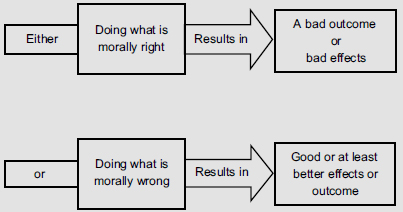

A person’s intentions and what factors would prompt him or her to take the final decision are the “last steps in the ethical decision making process”.3 When persons’ intentions and their final decisions are at variance with one another, they may feel guilty for what they have done. Businesspersons and professionals come across several such situations in their lives. An advertising agent may be asked by the director of a mediocre B-school to draft an advertisement for admission stating that since its inception, the institute has 100 per cent placement. Though the advertiser knows it to be untrue, he or she may be prompted to draft and release the blatantly untrue advertisement due to extraneous factors. The advertiser’s refusal to release the advertisement would mean loss of business, income and loss of a big client, all of which would affect the bottom-line of the company’s business. The management may argue that as an advertising agency, they were expected to act according to the wishes of their client. Personally, the advertiser may also be affected if he or she disagrees with the boss, which might adversely impact his or her career and income. These external factors might influence his or her decision in favour of a resolution to his or her ethical dilemma (Fig. 3.1). This decision might be unethical though the agent knows it is morally wrong. Such wrong decisions may lead to a feeling of guilt in a person.

Fig. 3.1 Structure of Ethical Dilemma

HOW ETHICAL DILEMMAS IN BUSINESS AFFECT THE STAKEHOLDERS?

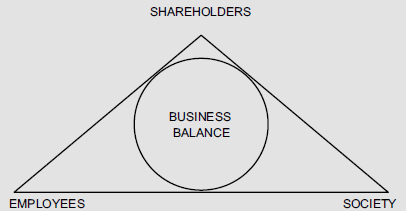

Ethical dilemmas in business can be best explained by the triangle in Fig. 3.2 with the stakeholders as its vertices. The stakeholders in this case can be broadly classified into shareholders, employees and the society at large.

Shareholders are the real owners of the company through their shareholdings in the firm. They expect a decent return on their investments (ROI). Corporations have to repay them for the opportunity costs they have incurred in investing in their firm. They have to be compensated through dividends, bonuses, bonus shares etc. In many corporations, the management is predominantly loaded with promoter family members holding a few shares. For instance, before the Indian economy opened up many promoter families had as little as 1.5–3 per cent shareholdings in the companies they had promoted, while the rest of the capital was contributed by the public, government-owned financial institutions and others. These promoter families, all the same, ran the corporations as if they were their personal fiefdoms and resorted to ‘asset-stripping’ and siphoned off the profits. The shareholders are given a raw deal in spite of their higher stockholdings.

In other cases, corporations themselves indulge only in bettering the interests of the shareholders leaving the employees and the society high and dry. Such companies devote themselves entirely in furthering the interests of the promoter families and their shareholders. The employees are given a raw deal. One look at the employee attrition rate would be an eye-opener.

At the other extreme, in some organizations, employees become militant and demand huge bonuses even when the organization itself is facing severe losses. The unions demand huge bonuses every year and at the slightest provocation go on strikes, forcing the embattled management to declare lock-outs causing huge financial losses, and losses in market share. There had been numerous such instances in India. In Kerala and West Bengal several industries had to be closed because of communist-led militant trade unions. Even elsewhere, in Mumbai and Coimbatore, hundreds of cotton textile mills had to be closed because of high workers’ demands even when these units were running into losses.

Society can be construed as creditors, competitors, suppliers, distributors and the common public in and around the organization. Corporations have to pay their suppliers on time. They have to repay their creditors due instalments of capital and the interests in time. They have to have partnership relations with their distributors, wholesalers and retailers so that all of them benefit from the channel partnership.

Fig. 3.2 Ethical dilemma in business

Corporations owe a lot to the society at large. A corporation, for instance, utilizes the infrastructure, resources, trained manpower and a host of other things provided by the society. So it has to repay with gratitude what it receives from the society. After all, the organization is there because the society allows it to be there. It is because managements have understood the logic behind this reasoning that they are coming forward increasingly to show their concern for public welfare, especially those of the disadvantaged sections of society in and around their facilities, and some of them, even beyond.

When there is an equitable distribution of wealth among all the three, namely, the shareholders, employees and the society, there will be peace and harmony and all-round well being. The corporation will earn the goodwill and the support from all of them. If this balance is tilted in favour of anyone in particular, then the corporation will be in trouble ultimately.

CORPORATE DILEMMA OVER ETHICAL BEHAVIOUR

Several corporate managements are in a dilemma whether it is worth their while to act ethically and practice corporate governance in their companies. Investing in ethical practices and being fair to all stakeholders will cost the corporates dearly. Therefore, most of them are in a dilemma. Moreover, in business, more than elsewhere, we are faced with moral and ethical dilemmas daily. We are faced with moral choices not only between right and wrong, but also between right and right. An ethics poster in Boeing said it all: “Between right and wrong there is a troublesome grey area.” According to Joseph Badaracco4 “We have all experienced situations in which our professional responsibilities unexpectedly come into conflict with our deepest values. We are caught in a conflict between right and right. And no matter which options we choose, we feel like we’ve come up short.”

Those in business come across several ethical problems that cause ethical dilemmas. For instance,

- They feel that there is lack of clear linkage between business ethics and financial success; they know of several instances where unethical businesspersons flourish and often enjoy fruits of others’ labour, while many others, scrupulously honest and ethical, have failed in their businesses and fallen by the wayside; there is no magical formula that would help in resolving such a dilemma.

- They are not clear as to how much they should invest in the business ethics system; they would like to know how much is good enough.

- They are unclear about the right balance between business ethics and the investment required for the same; many business concerns may be at a loss to know when and where to strike a balance in the allocation of time, efforts and resources between the two.

- The seemingly long gestation periods and the lack of short-term gains also is an obstacle. Investments in ethical business may be large, in diverse areas and multi-dimensional. They may bear fruits after a very long time. For instance, companies that are working in restoring ecological balance, may have to wait very long to know the fruits of their labour. Sometime, it may be even a fruitless wait.

SOURCES OF ETHICAL PROBLEMS

According to Keith Davis and William C Frederick5 ethical challenges in business take several forms and raise different kinds of ethical dilemmas. Ethical challenges and their attendant dilemmas may arise due to (i) failure of personal character; (ii) conflict of personal values and organizational goals; (iii) organizational goals versus social values; (iv) hazardous, but popular products. Added to these, there may arise other ethical challenges when corporations cross boundaries and become multinational companies. Newer technologies, diverse religious, cultural and social beliefs, different economic systems, political systems and ideologies may bring in their own dilemmas and problems. The issues and problems confronting business are large, varied and ever growing. Different functions of management (marketing, production, financial, human resource management, sales, service, etc.) throw up different problems and dilemmas. “The primary tasks for business are to be aware of the ethical dimension, to learn how to reason ethically as well as economically, and to incorporate ethical considerations into the firms’ operations”.6

Failure of Personal Character

A major source of ethical problems is failure of personal character. Companies, through no fault of their own, may recruit workers whose personal values are not desirable, without knowing the workers’ background. When they recruit their employees, they look for people with educational qualifications and experience that will match their job profiles. If the recruiters know that among otherwise qualified persons, some are undesirable, they will weed them out, but it is very difficult to spot persons with unethical qualities or to anticipate them to be so in future or to measure their ethical nature. Without such knowledge if recruiters take them in, those employees ‘may embezzle funds, steal supplies from the company, pad expense accounts, take unjustified leave, shirk obligations to fellow-workers, take bribes for favouring suppliers, use inside information for their personal benefit and to the detriment of others.’ Such unethical persons reflect the manner of their upbringing, early family and childhood experience, the type of schools they attended, the friends they had, and values of their immediate society. Since business does not have an ‘ethics screen’, if it recruits and employs some such persons, it is not to be blamed for the situation.

Conflict of Personal Values and Organizational Goals

Another source of conflict that gives rise to an ethical dilemma is when the company uses methods or pursues goals unacceptable to the manager or an executive. A typical example was that of George Couto, a marketing executive of the pharmaceutical giant, Bayer AG. In 2003, the company hatched a conspiracy to overcharge the American Medicaid programme for the antibiotic Cipro. Thanks to Couto’s effort to let the country know of the conspiracy, Bayer AG pleaded guilty to the criminal charge and paid a fine of $257 million when Couto’s exposure brought to the knowledge of public authorities (Food and Drug Administration) that Bayer AG used to relabel Cipro and sell it to another pharmaceutical company, Kaiser Permanente, with a different identification number so that it could claim more money from the Medicaid programme.

In this case, Couto’s personal values conflicted with the goal of Bayer, which was to profit by overcharging the Medicaid programme by duping the authorities. He had heard Helge Wehmeier, head of Bayer’s US Operations say in a compulsory ethics training programme: “You will never be alone in adhering to the high standards of the law” (in following ethical business) and continued “should you feel prodded, speak to a lawyer or call me. I am serious about that”.7 Couto’s conscience revolted against the hypocrisy of the top management. He wrote a short memo to his boss questioning him how the company reconciled the Medicaid practice with the company’s expectation of all employees adhering to the spirit and letter of the law. No one replied to his note. So, Couto went to a law firm which agreed to represent him and filed a law suit against Bayer in early 2000. He also quit the company soon after.

In most cases, companies resort to unethical practices due to the following two reasons:

- intensive competitive pressures; and

- exclusive focus on economic goal of making profit.

Employees like George Couto were not trouble makers but, in fact, trouble shooters. Their personal values and goals of their companies threw up an ethical dilemma.

Organizational Goals Versus Social Values

Activities of a company may be considered unethical by the stakeholders, due to changing social scenario or milieu. In a fast-changing situation, a company may find itself at odds against changing social values. For instance, the social and cultural mores that prevailed in India before 1991 when the economy was shackled by controls and licenses, were very orthodox and conservative. Organizations followed a hierarchical set up. Senior executives could be addressed only as ‘Sirs’. Hours of work were generally fixed from 9 am to 5 pm. Employees were expected to come to office well dressed. Men and women employees rarely mixed, kept a respectable distance from one another. Women rarely, if ever, worked during nights. But can we visualize such a situation today in many of our modern offices? The situation has now totally changed and if any organization managed by arch-conservatives insists on a model dress code, 9 to 5 working hours, expects juniors to address senior executives as ‘Sirs’, resorts to moral policing, etc., there will be a virtual riot in its premises!

Keith Davis et al.8 point out some instances wherein some companies anticipate shifts in values and attitudes of people and try to align themselves with these to avoid ethical conflicts and dilemmas. “Procter & Gamble withdrew its Relytampon promptly when its use was linked statistically to some deaths and Johnson & Johnson cleared all retail shelves of its Tylenol analgesic within days of the discovery that some containers have been poisoned.”9 Both companies acted with alacrity with a view to protecting their reputations in the market place as responsible companies and being aware of the high value placed by the public on consumer safety. Obviously, they were praised for their ethical alertness.

Thus, Procter & Gamble withdrew its product, which was linked to some user deaths, while Johnson & Johnson cleared all retail shelves of its Tylenol analgesic within days of the discovery that some containers had cyanide poison traces and had caused deaths. Though both companies were in no way directly responsible for the tragic deaths, they decided that in matters of life and death, it is better to be proactive than reactive, even though these withdrawals cost these companies dearly in money, but in the long run, they made up all losses and preserved their trust with the stakeholders.

Personal Beliefs Versus Organizational Practices

In recent times, ethical dilemmas in organizations arise when they employ multi-racial and multi-religious employees. Several organizations are accused of racial discriminations and gender bias in the work place and have been paying fines of billions of dollars or as out-of-court settlements. In the United States, mega corporations like Boeing have paid huge payments ‘for gender bias and racial profiling’. Infosys Technologies paid its former employee Reka Maximovitch $3 million in compensation in an out-of-court settlement ‘for alleged verbal sexual harassment, unwanted sexual advancements and unlawful termination of employment’ against the company and Phaneesh Murthy, the highest paid America-based executive of Infosys.10 In India too, there have been instances when companies run by a majority community organize religious functions in their premises in which persons belonging to other faiths are made not only to contribute towards expenses but also take part in religious rituals. Though these issues have not been brought out openly because of possible repercussions, they do add to the simmering discontent of the minorities. Though the country has adopted secularism, there are clear signs in public offices showing that it is not put into practice by a majority of officials. When people in power, be it in the public sector or private sector, show and display covertly or overtly their religious affiliations, it does send a wrong signal to all employees and to the public who have to frequent those offices. Several ethical dilemmas may arise because of this.

Production and Sale of Hazardous but Popular Products

In our society, there are a number of harmful products that is produced and sold to their users notwithstanding the fact that a vast majority of people is aware of their harmful effects. People know that smoking cigarettes causes cancer, excessive drinking causes accidents and liver problems, use of drugs causes both psychological and mental problems, and yet these products are being produced and consumed. Is this practice ethical?

Ethicists may pose a very relevant question: Those who defend sale of many harmful and obnoxious products argue that in a free society consumers use these products on their own volition, without any outside compulsion. Producers only cater to the consumers’ demands. If due to ethical considerations, these products are banned, it will create a black market leading to adulteration, profiteering and several undesirable consequences. Additionally, it will cause unemployment and loss of incomes to families. If for instance, companies like ITC Ltd. that produces cigarettes, and United Breweries Ltd. that manufactures and sells liquor are to be closed, will it not throw thousands of its employees out of their jobs? What, then, happens to their families? On the other hand, there are others who argue that allowing business people to produce these harmful products increase social costs through higher health and insurance costs. Therefore, it calls for strong social controls on businesses that produce and sell these risk items such as alcohol, cigarettes and harmful drugs.

Where does the ethical burden lie, when business sells products known to be actually or potentially harmful to society?

“A cigarette is a roll of tobacco, fire at one end, and a fool at the other,” said G.B. Shaw. Cigarettes cause a series of diseases: lung cancer, heart disease, circulatory disorders and yet companies like Philip Morris and ITC produce billions of cigarette sticks, sell them and make huge profits. Likewise, alcohol causes vehicular mishaps, irreversible brain damage, kidney failure, accentuates heart problems, and results in cirrhosis of the liver. Yet not only are companies like United Breweries permitted to manufacture liquor, sell and make money, but many state governments like Tamil Nadu have their own distribution outlets to sell it. The ostensible purpose is, of course, that the money thus earned is badly needed to provide welfare measures for the poor. But this reasoning does not seem to make any sense when it is known that it is mostly the recipients belonging to the very same poor families who waste their incomes and destroy their health through heavy drinking. Often, they drink with the money and the resources provided by the government, leaving their families penniless and starving.

Is the principle of caveat emptor in mercantile law to be adapted suitably in all these cases? Even that is now being relegated in view of consumer rights! Should individual rights and free choice override social costs? Could drunken drivers and carefree smokers deprive others of their legitimate rights to life and safety? Even items like hard drugs, dynamite and guns—could free trading in these be ethical? Will the ineffective Statutory Warning in the form of an inscription on the cigarette packet ‘Smoking is Injurious to Health’ legitimatize the unethical business?

Other Ethical Challenges

There are other unethical practices that are too many to enumerate. Some of the sample practices are

- price fixing and profiteering due to monopoly, and often artificially created scarcity;

- shifting unfair shares to the producer stakeholders and employees;

- discriminatory wage structure;

- using up scarce and irreplenishable industrial resources and raw materials;

- shifting or locating business at the cost of society; and

- overworking women and children.

WHY DOES BUSINESS HAVE A NEGATIVE IMAGE?

We have already noted that “Competitive pressures, individual greed, and differing cultural contexts generate ethical issues for organisational managers.”11 Further, in almost every organization some people will have the inclination to behave unethically (the ethical egoist)—necessitating systems to ensure that such behaviour is either stopped or detected (after unethical behaviour occurs) and remedied. Business has always been portrayed negatively by media, books, and movies. According to Batstone, “less than two percent of Americans rated US companies as excellent Corporate Citizen” in 2003. When companies do some good, they are hardly highlighted, while any wrongdoing by them is heavily publicized. There are several reasons why business has to confront ethical issues. When consumers in particular, and people in general observe that most of the businessmen have only one objective, namely, the single minded pursuit of profit even at the cost of consumers’ legitimate interests; when they try to profiteer; create artificial scarcity to charge a premium price for their goods and services; use low-quality inputs, do not honour their warranties and guarantees; use the media to hoodwink the hapless and uninformed consumers; damage wantonly the ecology and environment and resort to suppressio veri, suggestio falsi, people are prone to have a negative image of business. There are also many enterprises that are honest, scrupulous in their dealings and are passionately involved in community welfare and environmental protection, but they are not publicized much by the media. It seems to appear to the general public that such ethical enterprises are exceptions rather than the rule.

WHY BUSINESSES SHOULD ACT ETHICALLY?

There are a number of reasons why business should act ethically:

- to meet stakeholder expectations (and protect business reputations),

- to prevent harm to the general public,

- to build trust with key stakeholder groups,

- to protect themselves from abuse from unethical employees and competitors,

- to protect their own employees, and

- to create an environment in which workers can act in ways consistent with their values.

HOW CORPORATIONS OBSERVE ETHICS TO REDUCE DILEMMAS?

Organizations have started to implement ethical behaviour by publishing in-house codes of ethics that are to be strictly followed by all their associates. They have started to employ people with a reputation for high standards of ethical behaviour in the top levels. They have started to incorporate consideration of ethics into performance reviews. Corporations that want to popularize good ethical conduct have started to reward ethical behaviour. Most of these corporations conduct an ethics audit and at the same time they are continually looking for more ways to be more ethical.

CODE OF PERSONAL ETHICS FOR EMPLOYEES

Most company codes list the following values that are expected from their employees:

- Respect confidential information to which you have access.

- Maintain high standard of professional responsibility.

- Avoid being placed in situations involving conflict of interest.

- Act with integrity.

- Do not discriminate against anybody or anything on any bias.

- Maintain professional relations based on mutual respect for individuals and organizations.

- Be committed to the goals of the organization.

- Do not give up your individual professional ethics.

HOW TO CREATE AN ETHICAL WORKING ENVIRONMENT?

- Make the decision to commit to ethics.

- Recognize that you are a role model by definition, by your action, and by your values.

- Assume the responsibility for instilling ethical behaviour.

- Articulate your values.

- Train your staff.

- Encourage open communication.

- Be consistent.

- Abide by the laws of the land.

HOW DOES A COMPANY ESTABLISH ETHICAL STANDARDS?

It is very necessary these days for organizations to establish ethical standards so that their workers have least doubts as to what their company stands for. Most companies in advanced countries and some even in developing countries have developed their own codes of conduct which provide some ethical standards for their employees. Such codes of conduct may not help in resolving every ethical issue that arises but they help employees and executives deal with ‘ethical dilemmas by prescribing or limiting specific activities’. It should be emphasized here that it is not enough for a company to merely have the codes of ethics, but these should be effectively communicated to employees so that they are aware of them and abide by them. The effectiveness of the exercise, of course, will depend on how serious the top management is in implementing them, and the good example they set in observing them. In a widely reported instance in Wipro Technologies, a very senior executive who had put in long years of service in the company and had contributed significantly to its growth had to be dismissed because he claimed in his travel expenses more than his due.12 Disciplinary actions like this send a strong signal that the company means business in expecting ethical behaviour from its employees and it will get it in a large measure. Generally, taking such a severe action against one of the senior most executives will cause a serious ethical dilemma to the management and resolving it in a manner that Wipro’s top brass did is an abject lesson in ethical management.

Think and reflect about yourself, about the management, about the people, and about the relationship and the values you wish to incorporate. Create time for thinking and reflection. Periodically take time off to reflect and consider ‘where I am’, ‘where I have to go’ and ‘how I am going there’.

WALTON’S SIX MODELS OF BUSINESS CONDUCT

To understand business conduct, Walton13 has classified it into six models.

- The Austere Model: It gives almost exclusive emphasis on ownership interest and profit objectives.

- The Household Model: Following the concept of an extended family, the model emphasizes employee jobs, benefits and paternalism.

- The Vendor Model: In this model, consumer interests, tastes and rights dominate the organization.

- The Investment Model: This model focuses on the organization as an entity and thus on long-term profits and survival. In the name of enlightened self-interest, it gives some recognition to social investments along with economic ones.

- The Civic Model: Its slogan is ‘corporate citizenship’. It goes beyond imposed obligations, accepts social responsibility and makes a positive commitment to social needs.

- The Creative Model: This model encourages the organization to become a creative instrument, serving the cause of an advanced civilization with a better quality of life. Employees in such organizations behave and perform as artists, building their own creative ideas into actions, resulting in new contributions not originally contemplated.

These six models may be thought of as points on a continuum from low to high social responsibility. As a result, employees become proud of their company’s performance, and develop a sense of belonging and creativity.

Regardless of the model adopted by an organization, one of its most important jobs is to establish and blend its value together so that it becomes a consistent, effective system that is known and accepted by the fair primary claimant groups—investors, employees, customers and society, including government.

The system must be strong enough to withstand changes by partisan pressure groups but flexible enough to move with the changing society.

The primary responsibility of management is to reduce conflict areas among different claimants for sharing benefits of business and to bring about harmony of interest among diverse stakeholder groups.

Frederick C. Crawford14 has rightly expressed this idea thus: Management stands in the middle of a triangle. At the lower right corner is labour, with a rope round the management’s right leg yanking for raises. At the lower left corner is capital, with a rope round management’s left leg, yanking for dividends. The top corner, the market corner, is the worse. It has a rope round the management’s neck like a noose yanking for ever bigger bargains.

It is necessary, therefore, that an enlightened management must continuously balance the diverse objectives without allowing any conflict to arise between two or more objectives.

HOW TO RESOLVE AN ETHICAL PROBLEM?

Is it a Policy, Decision or an Action?

Is it ethical or unethical?

To resolve these questions that create a dilemma, ask three questions

- Utility: Does its benefits exceed cost (shareholder)?

- Rights: Does it respect human rights (society)?

- Justice: Does it distribute benefits and burdens evenly (employees)?

Answers to these questions in the affirmative will be the first step in the process of solving ethical problems.

HOW TO RESOLVE ETHICAL DILEMMAS?

Ethical issues take centre-stage in organizations today as managers, executives and employees face increasingly complex decisions. Most of these decisions are made in an organizational environment with different value systems, moral philosophies, competitive pressure and political ideologies, all of which provide ample opportunity for misconduct. Ferrel et al.15 quote a KPMG survey in 2000 which revealed that 76 per cent of the nearly 24,000 workers covered in the survey indicated that they had observed violations of the law or of company standards during the previous year. With such abundance of opportunities for unethical behaviour, “companies are vulnerable to both ethical problems and legal violations if their employees do not know how to make the right decisions”.16 Therefore, it is absolutely necessary that each company puts in place an ethics programme and makes it known to all its employees so that they know its values, mission and vision and comply with the policies and codes of conduct, all of which create its ethical climate. Many MNCs and several Indian companies have such ethics programmes and their employees are being made aware of the ethical values they stand for. To a great extent, this awareness reduces ethical dilemmas.

There are two basic approaches in resolving ethical dilemmas: deontological and teleological. Under the deontological (action-oriented) approach, an ethical standard is consistent with the fact that it is performed by a rational and free person. These are the inalienable rights of human beings and reflect the ‘characteristic and defining features of our nature’. These fundamental moral rights are inherent in our nature and are universally recognized as part of human beings, defining their very nature. These fundamental human characteristics are, inter alia, rights to fairness, equality, honesty, integrity, justice and the respect of our dignity.17 If we follow a deontological outlook while analysing an ethical dilemma, we are led to a much narrow focus. We confront such questions as: ‘Which actions are inherently good?’ ‘Does it respect the basic rights of everyone involved?’ ‘Does it avoid deception, coercion and manipulation?’ ‘Does it treat people equitably?’

Ethicists are of the view that the major problem with this approach is its inflexibility and uncompromising stance. There could be occasions when people may lie to help someone in dire straits. A co-worker may feign ignorance if the management makes a big fuss about the loss of worthless scrap of asbestos when he or she knows that one of his or her colleagues has taken them to provide roof material for inhabitants of several hutments who otherwise would suffer when it rained cats and dogs. It may produce more good than harm. Likewise, a person may steal a loaf of bread to feed a group of hungry children. A deontological approach to either of these cases will still condemn these acts.

The other approach to ethical dilemmas and their resolution lies in teleological (results-oriented) ethics. This approach to ethics takes a pragmatic, commonsense, layman’s approach to ethics. According to this school of thought, “The moral character of actions depends on the simple, practical matter of the extent to which actions actually help or hurt people. Actions that produce more benefits than harms are ‘right’; those that don’t are ‘wrong’”.18 A teleological approach to the above mentioned examples will tend to condone those acts of charity.

When we analyse an ethical dilemma in the context of these two approaches with a view to finding a solution to it, then we see the basic elements converge in determining the ethical character of our actions. While one school of thought points to the actions, the other points to the results that arise from the actions. Between them they reflect a wide spectrum of internal and external factors of human action that have moral consequence. While the deontological and teleological approaches to ethical issues seem to contradict each other in theory, in practice they complement each other. In the process of identifying and finding pragmatic solutions to ethical dilemmas, we should not ignore either of them, since each acts as a check on the limitations of the other.19

From these two philosophical standpoints to ethics, we can draw two methods for resolving ethical dilemmas; one that focuses on the practical consequences of what can be done, and the other that focuses on the actions. While the first school of thought argues that as long as no harm is done, there is nothing wrong, the other considers that some actions are always wrong. Which of these two is the right approach to resolve an ethical dilemma has been at the centre of debate among ethicists for centuries, with no definite answer in sight. However, many of them do agree, as pointed out earlier, that both approaches provide complementary strategies to help solve ethical problems. The Center for Ethics and Business20 offers ‘a brief, three-step strategy’ in which both the deontological and teleological approaches converge.

Step 1: Analyse the Consequences

Assuming that the resolution to the ethical dilemma is to be found within the confines of law—ethical dilemmas that arise in business should be resolved at least within the bare minimum of law and legal framework as otherwise it will lead to a sort of mafia business—one has to look at the consequences that would follow one’s proposed actions. And when one has several options to choose from, there will be an array of consequences connected with each of such options, both positive and negative.

Before one acts, answers to the following questions will help find the type of action that can be contemplated:

- Who are the beneficiaries of your action?

- Who are likely to be harmed by your action?

- What is the nature of the ‘benefits’ and ‘harms’?

The answer to this question is important because some benefits may be more valuable than others.

Letting one enjoy good health is better than letting one enjoy something which gives trivial pleasure.

Likewise, some ‘harms’ are less harmful than others.

- How long or how fleetingly are these benefits and harms likely to exist?

After finding answers for each of one’s actions, one should identify the best mix of benefits or harms.

Step 2: Analyse the Actions

Once you identified the best possible option, concentrate on the actions. Find out how your proposed actions measure against moral principles such as ‘honesty, fairness, equality, respect for the dignity and rights of others, and recognition of the vulnerability of people who are weak, etc.’ Then there are questions of basic decency and general ethical principles and conflicts between principles and the rights of different people involved in the process of choice of the options that have to be considered and answered in one’s mind.

After considering all these possible factors in the various options, it is sensible to choose the one which is the least problematic.

Step 3: Make a Decision

Having considered all factors that lead to choices among various options, analyse them carefully and then take a rational decision.

This three-step strategy should give one at least some basic understanding to resolve an ethical dilemma.

SUMMARY

An ethical dilemma is a moral situation in which a choice has to be made between two equally undesirable alternatives. A business dilemma exists when an organizational decision maker faces a choice between two or more options that impacts on (a) the organization’s profitability and competitiveness, and (b) its stakeholders. Businesspersons and professionals come across several such situations in their lives.

Ethical challenges in business take several forms and raise different kinds of ethical dilemmas. These dilemmas may arise due to (i) failure of personal character; (ii) conflict of personal values and organizational goals; (iii) organizational goals versus social values; and (iv) hazardous, but popular products.

There are several reasons why business has to confront ethical issues. When consumers observe that most of the businessmen have only one objective, namely, the single minded pursuit of profit even at the cost of consumers’ legitimate interests; when they try to profiteer; create artificial scarcity to charge a premium price for their goods and services; use low quality inputs, do not honour their warranties; use the media to hoodwink the hapless and uninformed consumers; damage wantonly the ecology and environment by adopting a policy of suppressio veri, suggestio falsi, people are prone to have a negative image of business.

Ethical issues take centre-stage in organizations today as managers, executives, and employees face increasingly complex decisions. Most companies in advanced countries and some even in developing countries have started to implement ethical behaviour by publishing in-house codes of ethics that are to be strictly followed by all their associates. With an abundance of opportunities for unethical behaviour, ‘companies are vulnerable to both ethical problems and legal violations if their employees do not know how to make the right decisions’.

When faced with an ethical dilemma, two basic approaches—deontological and teleological—are used. While the deontological and teleological approaches to ethical issues seem to contradict each other in theory, in practice they complement each other. According to Kenneth Blanchard and Norman Vincent Peale,21 authors of The Power of Ethical Management, there are three questions one should ask oneself whenever one is faced with an ethical dilemma, and grapples to find a solution for it.

- Is it legal? In other words, will the person be violating any criminal laws, civil laws or common laws by engaging in this activity? If it is not legal, the decision is not ethical.

- Is it balanced? Is it fair to all parties concerned both in the short term as well as in the long term? Is this a win-win situation for those directly as well as indirectly involved?

- Is it right? Most of us know the difference between right and wrong, but when we are placed in a piquant situation, how does this decision make you feel about yourself? Are you proud of yourself in making this decision? Would you like others to know you made the decision yourself?

Most of the time, when dealing with ‘grey decisions’, just one of these questions may crop up. But by taking the time to reflect on all the three, you will often find that the answer is very clear.

KEY WORDS

Ethical dilemma • Personal values • Organizational goals • Social values • Profitability • Competitiveness • Decision making process • Return on investments • Equitable distribution of wealth • Goodwill • Financial success • Gestation period • Conflict of values • Orthodox and conservative • Proactive versus reactive • Repercussions • Caveat Emptor· Price fixing • Competitive pressures • Individual greed • Ethical working environment • Ethical standards • Beneficiaries of action • Grey decisions.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What is an ethical dilemma? When does it arise in an organization? Who are the stakeholders impacted by ethical dilemma in business?

- What are the sources of ethical problems in business? How can these be resolved?

- Why does business have a negative image? How can a company establish ethical standards?

FURTHER READINGS

1. Bayer’s Record Fraud, available at http://multinationalmonitor.org/mm2003/03may/may03front.html

2. Center for Ethics and Business, available at www.lmu.edu/Page20711.aspx

3. Keith Davis and William C. Frederick, Business and Society: Management, Public Policy, Ethics, 5th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983).

4. O. C. Ferrel, John Paul Fraedrich, and Linda Ferrel (2005). Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making and Cases, 6th ed. (New Delhi: Bizantra, 2006).

5. Josephson Institute of Ethics, “Making Sense of Ethics”, available at www.josephsoninstitute.org/MED/MED-6beingperson.htm

Case Study

HLL’S FOLLY: MERCURY SPILL IN KODAIKANAL

(This case study is based on reports in the print and electronic media, and is meant for academic purpose only. The author has no intention to sully the image either of the corporate or the executives discussed herein.)

INTRODUCTION

On March 2001, more than 400 residents of Kodaikanal, an idyllic hill station on the Western Ghats in the south of India, caught the multinational Hindustan Lever Ltd (HLL) redhanded when they found a dumpsite with toxic mercury-laced waste from the company’s thermometer factory located in the heart of the town. “The 7.4 ton stockpile of crushed mercury-containing glass was found in torn sacks, spilling onto the ground in a busy scarp yard located near a school.”1 “The expose marked the beginning of an ongoing saga of dishonesty and botched cover-up efforts”2 by Unilever’s Indian subsidiary, Hindustan Lever Ltd.

On the same day, during HLL’s chairman’s annual review meeting held in the headquarters in Mumbai, “a query came from N Jayaraman of Corporate Watch, an NGO, whether there had been any disposal of mercury contamination waste along with broken thermometer and ground glass from HLL’s thermometer plant in Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu”.3 The company also learnt that earlier that day several Kodaikanal residents led by a few non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including representatives of Greenpeace staged protests outside the plant.

It was estimated that more 32,000 potentially affected people lived in Kodaikanal. Ten workers had died at the factory while it was functioning. Greenpeace, a global NGO committed to environment protection, claimed that the deaths were linked to mercury poisoning. Symptoms reported by ex-workers were fatigue, headaches, nausea and other stomach dysfunctions, blurred vision, skin complaints including burns and dermatitis, respiratory disorders, kidney dysfunction, central nervous system problems such as loss of memory, tremors, depressions and some report of seizure disorders. The ex-workers claimed that many of them got these symptoms after they were employed at the factory which had been functioning in Kodaikanal since 1983.

HISTORY OF THE HLL FACTORY

Hindustan Lever’s thermometer plant at Kodaikanal had a chequered history. The factory which was originally in New York was shutdown for environmental reasons. US-based Chesebrough Pond’s relocated its aging mercury thermometer factory from Watertown, New York to Kodaikanal in 1983. Kodaikanal is a verdant hill station in the upper Palani Hills in southern Tamil Nadu. The town measures 21 sq km, with a population of 32,000. The factory was acquired by Unilever, after it bought Chesebourgh Pond’s owner of HLL, which is Unilever’s 51 per cent owned Indian subsidiary. The factory was said to be the largest thermometer plant in the world. Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) giant, imported all the mercury and glass for the thermometers from the United States, and exported all the finished thermometers to the US-based Faichney Medical Co. which in trun exported them to markets in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Germany and Spain.

Mercury is a toxic metal, which when converted into deadlier forms such as methyl mercury and released into the environment could cause tremendous health problems to people living nearby and even far away. The factory that manufactured glass mercury thermometers for exports was split into two main areas—the first area converted glass tubing into empty thermometers, stems and bulbs. The second area filled them with mercury, marked the scale, sealed the end and packed. Both areas, working with glass, generated considerable quantities of scarp. Glass scrap from the first area was sent for recycling to the glass merchants. Glass from the second area containing mercury was first treated (crushed and heated) to recover the mercury. The remaining scrap was sold to recyclers unlawfully and in breach of the company’s operating policies.

All water from the plant was led to a dedicated effluent treatment plant. Sludge from the effluent treatment plant was dried, packed in plastic drums and stored in the pit on site under cover. During the investigations, it was also found that the factory buried glass scrap on the site after appropriate regulatory approvals.

The Pambar stream that runs through the forests below the back wall of the factory flows down to the Kumbhakarai waterfalls, a popular tourist bathing site. Below the waterfalls, the stream surpasses into canals flowing from the Vaigai dam that irrigates lands down south. The slopes where the wastes are dumped are part of the Pambar Shola watershed, draining water through the Pambar river. This small river eventually ends in the plains leading up to the temple city of Madurai.

DAMAGE TO WORKERS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Before the HLL thermometer factory was shut down on the orders of the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board (TNPCB), it was reported that between 600 and 800 workers were exposed to mercury due to unsafe working conditions and the willful negligence of the HLL management in not warning employees about the dangers of mercury. Mahendra Bapu, President of the Pond’s-HLL Ex-Mercury Worker’s Welfare Association claimed: “HLL has caused irreparable damage to the health of the workers. More than 20 workers between the age group 22 and 35 years have died due to poisoning from the factory”4 over the past 18 years. Besides, workers who were directly exposed to the hazardous toxic metal, thousands of people in the vicinity of the factory suffered from “skin diseases, premature graying, incessant headaches, stomach pain, kidney problems and blood in the urine.”5

Moreover, what was difficult to understand was the fact that HLL, subsidiary of Unilever that was a signatory to the UN Global Compact principles discontinued occupational safety measures at the factory from 1985, that is, the second year of operation. Besides, the only warning given to the workers by the management was ‘wash hands before eating’, without giving any inkling to the uneducated workers the hazardous nature of the work they were engaged in, thereby covertly endangering their lives. Another problem was that the poisonous vapour carrying mercury traveled far beyond the factory fence, encircled the entire Kodaikanal town that is dependent on tourism and boarding schools and contaminated the Pambar Shola and the scenic lake.

HLL also had to bear a vicarious responsibility to its criminal negligence of its worker’s safety and health hazards of citizens of the town inasmuch as it refused to provide any credible information on mercury use and its disposal at the factory, despite repeated requests by TNPCB. This prevented timely remedial measures, as independent analysts could not verify the claims of HLL’s consultants that mercury releases posed no danger to the town’s people and environment.

HLL’S RESPONSE TO COMPLAINTS

Despite legitimate concerns of the workers and Kodaikanal citizens regarding the adverse health effects of workers and factory neighbours, HLL sought to dismiss the complaints. The company’s responses to the mercury-dumping controversy were ‘characterized by denials, cover-ups, untruths and a singular lack of transparency.’ After denying in March 2001 of any mercury waste leaving the factory and admitting that the factory keeps meticulous records of all mercury inventories, the company accepted later that it shipped out a load of 5.3 tonnes of mercury-bearing waste to a scrap yard in Kodiakanal.6 However, independent verification by activists showed that the actual quantity of mercury waste sent out of the factory to the Kodaikanal scarp yard was 7.4 tonnes. Subsequently, HLL admitted to having systematically sold over 98 tonnes of those toxic factory wastes to various parts of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

Though HLL was very defensive at the early stages, with local and Greenpeace activists becoming more vociferous in their complaints against the company to the public and TNPCB, the company responded quickly, transparently and even aggressively. HLL duly informed TNPCB of the details of mercury disposal. The persons responsible for the breach of the company’s well laid waste disposal policy were identified and penalized, the penalty depending on the severity of the offence committed. A new factory manager, R. John George, who knew the local language, Tamil, and who had no reason to defend the past actions of the factory administration was appointed.

Following the directive of TNPCB, manufacturing operations were suspended on 8 March 2001. Earlier, in 1999 itself the glass scarp that was stored in old and worn-out shed known as the ‘bakery’ till 1998 was shifted to a safe and secure place. The factory personnel rendered jobless in the wake of suspension of work in the factory were employed for verifying weights and packing of glass scrap.

An environmental audit was commissioned by HLL on 11 March 2001. It appointed the well-known URS Dames & Moore (URS) of Australia to conduct a detailed environmental audit. URS admitted that the estimated discharge of mercury to the Pambar Shola forest was approximately 300 kg. The HLL-appointed consultant also said that another 700 kg of mercury waste were released through air-borne emissions.

Apart from the environmental audit by URS, HLL also engaged the services of an acknowledged international expert in the eco-toxicology of mercury, Dr P N. Vishwanathan, to study the environmental and health aspects relating to Kodai thermometer factory. However, unlike URS scientists, this former Director of Industrial Toxicology Research Centre of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR-ITRC), Lucknow, found no evidence to risks caused by mercury either to humans or environment.

Another survey among former employees of HLL by Dr Mohan Isaac of Bangalore-based community health cell noticed symptoms consistent with mercury exposure among some of the participants, and recommended that based on the available data, a thorough investigation of the potential health hazards be made.

All the surveys and studies made both by HLL and activists offered conflicting views about the exact nature and impact of the mercury waste on workers and the immediate community of the Kodai thermometer factory.

HLL EXITS FROM THERMOMETER PRODUCTION

Hindustan Lever Ltd also decided, in principle, in January, 2001 to exit from the thermometer business. The company said in a statement, that it was quitting the business because it is not core to the company. “The company’s core business is the manufacture and marketing of soaps, detergents, skin care products, deodorants and fragrances, food and beverages”.7

Moreover, in response to complaints from former workers and NGOs, including Greenpeace activists, the TNPCB ordered the factory to close down and clean up the toxic mess the company had created. TNPCB also directed HLL to decontaminate the site and its surroundings to global standards. The company also was under great pressure from the public and government to cart away the mercury waste. The company sent back at least 300 tonnes of the toxic material to the United States in 2006.

ROLE OF NGOs IN MAKING HLL REDRESS PUBLIC GRIEVANCES

If unlike Union Carbide (now Dow Chemicals) in Bhopal, HLL saw reason rather early in the period of public agitation and took corrective measures, it was because of the active role of NGOs spearheaded by Greenpeace activists. The NGOs left no stones unturned to mobilize public opinion and to pressure TNPCB and the Tamil Nadu government to compel HLL to make amends for its acts of commission and omission in the unlawful disposal of the hazardous toxic waste and in the exposure of its workers to potentially dangerous work environment. It was the NGOs that galvanized workers, concerned citizens and environmental activists to force the factory to suspend operations in March 2001, after discovering that the company had dumped the mercury-contaminated waste at several public locations. The NGOs were also responsible to form the Tamil Nadu Alliance Against Mercury (TAAM), which tried to identify and contain contaminated soil. They were also behind several measures initiated by TNPCB to set up a special Hazardous Waste Management Committee (HWMC) to monitor the complete site remediation by HLL, after removing the mercury-laden broken thermometers and crushed glass. Greenpeace campaigners Ameer Shahul and Navroz Mody took the lead in canvassing for remediation measures by HLL and later initiated the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) investigation. On examination DAE found that the atmospheric levels of mercury near the factory was 1.32 micrograms per cubic meter (1.32 μg/m3), which was about 1000 times more than what is generally found in uncontaminated areas.8

The NGOs were also behind the former workers approaching the Supreme Court of India in 2005, demanding compensation from HLL for the loss of their jobs and the health hazards they suffered. The apex court appointed a Monitoring Committee to study the issue and report it to the court. The Supreme Court Monitoring Committee in turn has acknowledged mercury-related health damage of workers and community residents: “The situation at HLL is extremely serious in nature. There can be no two opinions that remediation and rehabilitation of the natural environment and of workers and others are both urgently required”.9

The NGOs and their activists by their incessant and continued demands and demonstrations ensured that the livelihood of workers was not jeopardized by HLL’s negligent and irresponsible behaviour, a detailed investigation was made into the extent and nature of pollution caused by the mercury waste inside the factory and the outside environment; the ongoing threat to the adjacent school children and the nearby community was eliminated by forcing HLL to clean up the dumpsite; the damage to the health and safety of the workers, past and present was properly assessed and compensated adequately; and that HLL accepted both the responsibility and the financial liability for the damages caused to the workers, the community and ecology of the Kodai town and the surroundings hills.

The most laudable part of the NGOs role is the novel and dramatic manner in which they kept the mercury waste spill issue alive throughout, by using a variegated set of measures available to them. They shouted slogans and showcased placards during HLL’s annual general meetings on 13 June 2003 and 29 June 2004; they bound themselves by chain to the HLL Chennai branch office on 15 November 2002; they enlisted constantly the support and sympathy of the general public to the cause they were fighting through issue of leaflets, and organizing demonstrations and meetings. They also very effectively used the Greenpeace Web site, photo albums, seminars and anniversaries on a regular and timely basis so that the issue is not forgotten by all the stakeholders—the former HLL employees, Kodaikanal town’s concerned citizens, environmentalists, TNPCB and the Tamil Nadu Government.

As pointed out earlier, there have been conflicting reports from teams of HLL-appointed as well as NGO-commissioned professional experts as to whether the unlawful disposal of mercury wastes have caused damages to the health and safety of humans and environment, but the NGOs were convinced that the spread of mercury wastes had done considerable harm to both.

WHERE DOES THE TRUTH LIE?

Two scientific studies, made after the closure of the Kodai factory in March 2001, have shown high levels of mercury contamination within the town, in the forests, and in locations as far as the beautiful and nature-made lake, 20 km from Kodaikanal. The studies also revealed that the Pambar Shola forests, acknowledged as one of the bio-diversity hotspots of the world were also adversely affected.

Scientists from the National Centre for Compositional Characterization of Materials (CCCM), a DAE institute had reported the incidence of atmospheric mercury in some areas outside the HLL factory site in Kodaikanal. The concentrations of mercury up to 1.32 μg/m3 was reported to be about a thousand times higher than in the areas that were not contaminated.

HLL responded to this finding by saying that the findings of the report were at “variance with the data collected by independent foreign consultants” and that the levels detected were “much lower than 50 mg limit prescribed under the factory rules.”10

Obviously, the statements made by HLL betray its lack of understanding of mercury as a serious toxic hazard.

A study conducted by Greenpeace Research Laboratories reported considerable amounts of mercury along the hills surrounding Kodaikanal Lake to the west of the factory and in the Vattakanal and Pambar Sholas. The study showed the distance to which the impact could be felt. “The manifold increases in accumulated mercury in the elevated lichen samples give an indication of potential impacts on ecosystems at these locations. Plants that accumulate atmospheric mercury are likely to form part of the diet of fauna living in the vicinity. Through such processes, mercury can be transferred into the wider ecosystem, possibly bio-accumulating in certain species.”11 The findings of the Greenpeace report was similar to a study conducted by the DAE.

HLL meanwhile, continued to deny responsibility based on the insufficient data provided by their study teams for any mercury impact on the health of workers at the plant, or of the surrounding community or environment. These studies led HLL to deny that their mercury could be responsible for the death of 10 young men working in the factory. But eventually, the company which had earlier denied all charges against its thermometer factory of dumping mercury waste illegally has finally admitted that the 5.3 tonnes of mercury-containing glass wastes currently lying at the Munjikal scrap yard in Kodaikanal came from their factory.

In an official communication to Greenpeace, the company promised “to track and retrieve other such shipments that have been sent to various locations outside the factory, and to clear the wastes that were found to be dumped in the watershed forests behind the factory wall.”12 Though TAAM, rallying against the company’s unlawful practice welcomed these admissions, were legitimately upset that HLL had not apologized to the community. Many environmental and NGOs (Box 3.1) have demanded justice from HLL for their folly. However, it is only fair to point out that this was the first time a major company has actually accepted a part of its faults openly.

ULTIMATE DEMAND TO GOVERNMENT

The coalition of ex-workers, community representatives of Kodaikanal, and Greenpeace demanded that

- The government should initiate legal action against HLL for lying to a statutory body like TNPCS and providing false information, and for destroying evidence in a matter concerning the lives and health of hundreds of workers, their families and many thousands more who reside in the vicinity of the factory or those who might have come into contact with mercury.

- The government should take serious action against the Inspectorate of Factories, who for 18 years failed in their assigned duty to find any traces of mercury at the factory site or beyond, thus jeopardizing the lives of workers and the environment.

- The government should initiate, at HLL’s expense, independent long-term studies to monitor the impact of mercury on this fragile hill-forest ecosystem, the town and the people. The mercury in the forests could have far reaching implications both in the town of Kodaikanal and downstream Palani and Vaigai, as pointed by the DAE and Greenpeace studies.

- The government should order, at HLL’s expense, an independent inquiry on the impact of mercury on the health of the workers, their families and other susceptible members of the community, and initiate long-term monitoring and treatments for detoxification of affected populations.

- The government should find ways and means of compensating families of the ten dead workers and affected community members for loss of earning capacity, damages for mercury contamination and long-term health remediation, and

- The government should ensure that the mercury retrieved from HLL’s wastes is permanently destroyed and not released once again in another unsuspecting part of the developing world.

BOX 3.1 YSC PROTEST FOR KODAIKANAL WORKERS

The Youth for Social Change (YSC) activists staged a protest in Chennai against Hindustan Unilever Ltd accusing the company of not taking any steps to clean the environment even after seven years of shutting down its mercury thermometer plant in Kodaikanal. They alleged that at least thousand workers were exposed to the mercury contamination and no compensation has been made to any of them. The YSC members left after submitting a petition to the company representatives.14

CONCLUSION

There has been ample evidence to prove that the mercury emitted from the HLL plant had far greater and wider impacts than the experts commissioned by HLL were prepared to reveal. And yet, five years after being caught, HLL is yet to submit complete clean-up protocols to the TNPCB. If it were in a developed country, HLL would have been forced to clean-up and remediate such a disaster site immediately, using the best international standards and practices.

Besides, as pointed out by J. Arunachalam, head of the DAE centre, mercury is still prevalent in the atmosphere because the discarded factory scarps and contaminated vegetation re-emit absorbed mercury.13 The loss to the environment is huge. Thousands of people, especially workers, their families and other relatives, have been unsuspecting victims of the persistent dangers posed by HLL’s inadequate commitment to transparency, or concern for public health and environment.

Hindustan Lever’s behaviour violates the environmental principles of the UN Global Compact such as supporting a precautionary approach to environmental challenges, undertaking initiatives to promote environmental responsibility and promoting the diffusions of environmental technologies. Unilever, the parent organization of HLL is a prominent signatory of Global Compact. If HLL and Unilever stand by these high principles, they should ensure they put these principles into practice in every conceivable situation relating to their closed factory at Kodaikanal.

KEYWORDS

Idyllic hill station • Stockpile of scrap • Stomach dysfunctions • Dermatitis • Respiratory disorders • Kidney dysfunctions • Central nervous system • Seizure disorders • Willful negligence • Hazardous toxic metal • Premature greying • Lack of transparency • Meticulous records • Independent verification • Occupational safety measures • Giving any inkling • Credible information • Timely remedial measures • Manufacturing operations • Safe and secure place • Environmental audit • Eco-toxicology • Potential health hazards • Non-government organizations • Greenpeace activists • Acts of commission and omission • Biomonitoring of mercury • Multinationals • Health hazards • Uncontaminated areas.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Trace the history of the establishment of Kodaikanal thermometer factory and how it came into the adverse view of the NGOs, the public and the TNPCB?

- How did Hindustan Lever Ltd respond to the initial complaints of various stakeholders that the company had adopted a callous attitude towards the disposal of hazardous mercury-laden waste? What type of strategy did the company adopt when it realized that the entire fault lay in the carelessness of the factory’s administration?

- What was the role of NGOs in bringing to light HLL’s dumping of mercury waste in various parts of Kodaikanal locality? To what extent were they able to get justice to the affected workers and the general public?

- Explain in your own words the HLL Kodaikanal mercury spill controversy. What is the present status of the controversy?

- What kind of roles have NGOs such as Greenpeace India, played in bringing to the open the issue of HLL’s spill of toxic mercury waste in and around Kodaikanal hills? Did it have the desired impact, in your view?

- How would you reconcile diametrically opposite views held by HLL-assigned scientists and those appointed by the government and NGOs about the quantity and the toxic nature of the spilled mercury waste and its impact on the frail ecology of Kodai hills? Was there any meeting point at all between these two viewpoints?

FURTHER READINGS

1. Bureau, “Greenpeace Charges HLL With Toxic Dumping at TN Plant,” Hindu Business Line, 21 June 2001, available at www.blonnet.com/2001/06/21/stories/02212575.htm

2. Bureau, “Hindustan Lever Has Decided to Discontinue Manufacture of Mercury Thermometers at Its Kodaikanal Factory,” 20 June 2001, available at www.timesofindia.com

3. Bureau, “HLL to Stop Production at Kodaikanal Plant,” 20 June 2001, available at www.timesofindia.com/200601/20busi6.htm

4. Greenpeace, “Greenpeace Accuses Unilever of Negligence Over Mercury Poisoning of Indian Tourist Resort,” 7 March 2001, available at http://archive.greenpeace.org/pressreleases/toxics/2001mar7.html

5. Greenpeace, “Hindustan Lever Admits to Dumping of Mercury-Containing Wastes,” 22 March 2001, available at www.greenpeace.org/india/press/releases/hindustan-lever-admits-to-dump

6. Greenpeace, “Tamil Nadu Groups Launch Alliance Against Mercury and Lever,” 28 March 2001, available at www.greenpeace.org/india/press/releases/tamilnadu-groups-lauch-allianc

7. Greenpeace, “Unilever Admits to Toxic Dumping; Will Clean Up, But Not Come Clean,” 19 June 2001, available at http://archive.greenpeace.org/pressreleases/toxics/2001jun19.html

8. Nityanand Jayaraman, “Unilever’s Mercury Fever, Inconsistencies Galore, A Timeline on Unilever’s Mercury Dumping in India,” Corpwatch.org, 4 October 2001.

9. Sheila Mathrani, “Greens Force Hind Lever to Close Kodaikanal Plant,” The Economic Times, 29th June 2001.