Chapter Fourteen

Marketing Ethics*

We commence this chapter with the role of marketing in bringing products of great value to humankind. The chapter also details some norms in marketing ethics, with examples of practice as well as infraction. We then look at the darker side of marketing also—its role in bringing out products of harm to the society. In this milieu some firms bring out good products, even though there are no market compulsions to do so and at times even at a cost to the firm. A few other firms are compelled to move away from products that are harmful to the society due to either actions by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or legislation. We also examine the Indian context in which marketing ethical capacity and infraction is fostered. Later, we deliberate on some guidelines and norms that could build marketing ethics of high standard. Towards the end of this chapter we elaborate on how marketing ethics is not just concerned about bringing out safe products but also concerned about the process of delivering the product—namely, how firms advertise, promote, distribute and price the products and examine areas within marketing, citing examples, of good and bad ethical practices. It is however, not the objective of this chapter to prescribe corrective actions for ethical infractions.

ROLE OF MARKETING

Positive role of marketing

Marketing is performing a remarkable role in developing and delivering products of great value to the society—such as computers, mechanized vehicles, safe and healthy drinking water, and housing solutions. It seeks to understand the needs of consumers and delivers a product or a service that satisfies the need. In fact, astute marketing is about uncovering even unstated or latent needs of consumers, making him or her aware of those needs and delivering a product or a service to satisfy those needs.

Steelcase, an office furniture manufacturer, set up video cameras at various businesses and analysed the tapes looking for patterns of behaviour and motion. The company came to a conclusion that employees who work in teams would be able to work most effectively if they work collaboratively and privately. This resulted in the creation of modular office units that permit people to work in teams as well as alone.1

Marketing’s contribution in services is equally valuable. Evolving effective campaigns in containing many a world’s scourge, for example, AIDS, polio, etc. are noteworthy. Banking, financial services and insurance solutions, healthcare, etc, are other areas in services where marketing has provided solutions to diverse consumer needs. For instance, the State Bank of India’s diverse banking, financial and insurance products serve innumerable Indians even in the remote corners of rural India. The services of Housing Development Finance Corporation (HDFC) in providing housing solutions worth one trillion rupees to about 2.7 million customers is equally noteworthy.

Negative Role of Marketing

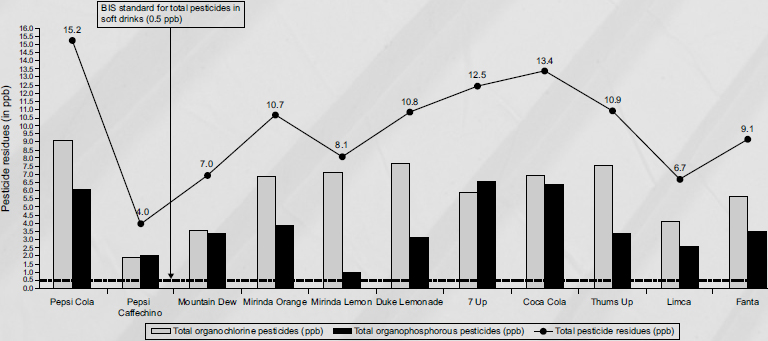

But there is a darker side to marketing too. It makes and sells unsafe products. For instance, Coke and Pepsi in India are selling colas that contain harmful pesticides exceeding 140 times the BIS standards. When consumed it may have several side effects, including cancer and genetic impairment of the foetus.2 Plastic bags are known to harm the environment since they are not biodegradable. Many well-intended products for adults, such as iron supplements, are not packed as ‘child-proof’ rendering them unsafe for children with possible risks including fatality. The darker side of marketing is evident even in services. Scores of quacks tout miracle medicines impairing body organs permanently or even causing fatality. Banks compromise confidentiality by selling their customer-lists to telemarketers who intrude into the privacy of customers.

Voluntary Adherence to High Marketing Ethics

Yet there are many examples of marketers adhering to high ethical standards even when there is no market compulsion to do so. A good example is Merck’s development and distribution3 of a drug for river blindness or onchocerciasis. It is caused by the bites of black flies found in some fast-flowing rivers of Africa and Latin America. River blindness is accompanied by intense itching and eventual blindness: two outcomes that dramatically affect the quality and duration of life. In 1978, the World Health Organization estimated that 340,000 people were blind because of onchocerciasis and 18 million or more were infected. There were no safe treatments and no financial incentives to develop drugs for some of the world’s poorest populations. Merck discovered ivermectin as a possible remedy for river blindness. However, it faced an unattractive market. Yet it went ahead and developed the drug called Mectizan, and was ready to market the drug for free. Again it faced problems in distribution. Merck organized this as well. Merck has till date donated more than a billion tablets, benefiting more than 45 million people.

Closer at home the story of Alacrity Housing.* It offered to pay liquidated damages to customers in case of delay in the completion of a housing project, even when the delay might have been attributed to delayed clearances from various governmental authorities. This practice was and is still unparalleled in the annals of housing solutions business in the world. It has to be read in combination with the fact that Alacrity Housing would never pay any bribe to government authorities for such clearances in spite of the fact that bribing is the norm in construction industry.

Ethics Due to Market Compulsions

We can also observe many ethical practices due to market compulsions. Marketers are moving away from guns and cigarettes due to public demands (e.g., pressures from NGOs like the Centre for Science and Environment) and government restrictions. Many of them are becoming increasingly aware of marketing ethics and are moving towards healthier and safer products. Wills, a brand of cigarettes from ITC, on its own volition, withdrew from sponsoring the Indian Cricket Team. Advertisers form codes of advertising ethics. Such activism by NGOs, government, and judicial initiatives impels one to think whether the age-old philosophy ‘Let the buyer beware’ has changed to ‘Let the seller beware’.

Does it then mean that if there was no pressure from the NGOs and government, firms can continue to market harmful products for which there is sufficient demand? Kotler4 addresses this issue by delving into a different interpretation of the central axiom of marketing—‘satisfy customers’. History bears out the fact that firms that satisfy their target consumers stay in business and make profits while those that do not perish. Kotler then restates the axiom to be “give the customer what he wants,” and implies a corollary “Don’t judge what the customer wants.” The corollary raises two public interest concerns:

- What if the customer wants something that is not good for him or her?

- What if the product or service, while good for the customer, is not good for the society or other groups?

Addictive or compulsive consumption is not only observed in cigarettes, but also in innocuous products such as gutkhas,† burgers, chocolates, and soft drinks. In services, such addiction can be seen in gambling, Internet surfing/chatting and video games. In a general sense, even shopping is a known addiction; the so-called shop-a-holic finds release in this behaviour in much the same ways as alcoholics or drug users do.5 Some products that are good for the consumer but are not good for the society are asbestos, lead paint, fuel-guzzling automobiles, etc. What should firms engaged in such businesses do? Are these firms engaged in products that are acceptable to the society? It is indeed not easy to answer such questions. Some may find nothing unethical in marketing such products while others may find the practice objectionable.

Shift From Emphasis on Products to Process

We deliberated on some products that are good for the society and some bad. The issue of marketing ethics is not limited to the provision of ethical or unethical products alone. Marketing ethics also deals with how such products are delivered to the customers. Marketing is an organizational function and a set of processes for creating, communicating and delivering value to customers, and for managing customer relationships in ways that benefit the organization and its stakeholders6 (our emphasis). Marketing achieves this through various processes such as the product development, packaging, branding, advertising, promoting, selling, distributing, pricing and customer servicing. Determinants of the appropriate value such as

- what the product should be,

- how it is manufactured,

- its appropriate price,

- its appropriate form of packaging,

- how it is distributed and delivered to the customers,

- how it is communicated to the customers,

- the kind of incentives provided to the customers for first trial and repeat purchase of products, and

- the appropriate division of the realized value among the stakeholders, etc.

are all areas in marketing laden with subjective value judgments of what is right and wrong. Clearly, the scope of marketing ethics encompasses not only the outcome of the product but also on the process of delivering the outcome.

Issues of marketing ethics involving the processes are many. For instance, it can be argued that

- Marketing provides compelling stories to keep up with the Joneses. ‘Neighbour’s envy, owner’s pride’ impels Onida, a brand of popular TV

- Marketing targets children directly, bypassing parents, even though children cannot discern and make reasoned choices. A famous toy store in Chennai, redesigned its store layout to be more children-friendly and provided ‘kid’s shopping cart’ which moved the power of decision making from the parents to children.

- Marketing misleads and uses deception to persuade consumers to buy products and services. A South India based brand of inner garments declares that it uses ‘pro-skin technology’.

- Marketing intrudes into the privacy of consumers. Direct marketing can be seen as a case in point.

Is Coca-Cola or Pepsi an unsafe product? Is Onida TV compelling consumers to keep up with the Joneses? Is direct marketing an intrusion into the privacy of consumers? It appears, there exists a thin line between a normal and acceptable marketing practice and unethical behaviour. What is right and what is wrong is difficult to determine.

DEFINING MARKETING ETHICS

Marketing Ethics as a Right or Wrong Action

The same difficulty in precisely defining the terms ethics or business ethics is encountered in defining the term marketing ethics also. Briefly, marketing ethics means a standard by which a marketing action may be judged ‘right’ or ‘wrong’.7 A right marketing action is expected to contribute to the overall societal gain both in the short and the long run. Easily it can be noticed that there can be no precise definition of what is right and wrong. Seldom would everyone in a society agree to what a right or wrong marketing action is.

What is right or wrong is a collective perception of a society or a group; in some sense the moral standards. Then marketing ethics can also be defined as how moral standards are applied to marketing decisions, behaviours, and institutions.8 In the United States, the American Marketing Association (www.marketingpower.com), having many academicians and firms of repute as members, has a published code of marketing ethics. In India, this role could be easily donned by some leading B-school or marketing management association. For instance, the Loyola Centre for Business Ethics and Corporate Governance at the Loyola Institute of Business Administration, India has formulated a written code of ethical marketing practices.

Ethics and Law

Ethics and law are closely connected but hardly the same. Before we delve into the subject, let us understand the differences between the terms ‘ethical practice’, ‘unethical practice’, ‘legal activity’ and ‘illegal activity’.

The terms ‘ethical practice’ and ‘unethical practice’ though understood by most as opposites, are conceptually two different constructs or two different words. The same goes with the set of words ‘legal activity’ and ‘illegal activity’. The notions ‘unethical practice’ and ‘illegal activity’ are clearer, sharper, and more concrete than notions of ‘ethical’ and ‘legal’, respectively. It is possible to have a clear meaning of the words ‘illegal’ and ‘unethical’ than the words ‘legal’ and ‘ethical’.

It is easier to understand what is illegal than what is legal. For instance, failing to print the maximum retail price on the packaging, colluding to keep up price, etc., is illegal. However, we understand what is legal to be all those activities that are not classifiable as ‘illegal’. Law seems to lay down clearly what is illegal and sets a punishment for such activities. In this sense, law can be understood as codes of minimum moral standards infraction of which attracts punishment. Usually, what is illegal is considered unethical too; but we will discuss some exceptions to this soon.

Similarly, what is unethical is also easier to understand than what is ethical. Unethical practice would be that which in a marketing exchange alters the entitlements of either the buyer or the seller in such a way that it is at the expense of the other. For instance, raising the price by a per cent and offering that as a discount to attract customers is an unethical practice. This is because, the practice offers pseudo utility to the customer and extra profits to the seller. Further, actions by marketers that in some sense take advantage of the customers’ good faith can be considered as unethical. For instance, doctors often prescribe a host of tests in laboratories, not all of which are a necessity. In this case, the consumer reposes good faith on the doctor and is in no position to verify if the tests are a necessity or not. It can be clearly seen in the two examples cited here that both of these unethical practices are not illegal.

Unlike how legal activities are all those that are not designated as illegal, ethical practices are not just all those practices that are not considered unethical. The words ethical practice is a lot richer in meaning. Consider the example of Merck discussed above. If the firm chose not to manufacture and distribute Mectizan free of cost to alleviate the sufferings of millions of poor people, it has committed no unethical practice. Thus ethics can be understood as codes of high moral standards, the adoption and action of which leads to overall societal good. We discuss more on the richer aspects of the word ‘ethics’ in a later section, ‘Normative Ethics’.

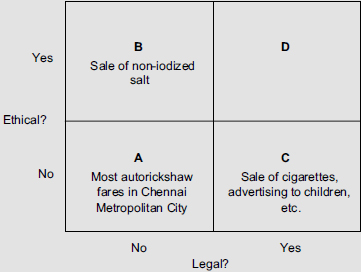

The above can be summed up using a quadrant analysis. See Figure 14.1.9

As it can be easily seen from the figure, the scope of ethics goes beyond the law. Understanding cell A is easy. It represents a combination of marketing action that is at once unethical and illegal. For example, the Chennai city autorickshaws seldom use the fare meters installed in the vehicles and demand arbitrary and much higher than legally prescribed rates. Cell B represents cases of marketing action that is ethical but illegal. For example, it is illegal to sell non-iodized salt in India. However, one can easily buy non-iodized salt in India in many shops and that would not be considered unethical at all while iodized salt may be considered better. Cell C represents cases of legal but unethical marketing actions. For instance, sale of cigarettes is legal but is considered unethical to smoke. Cell D requires no elucidation.

Figure 14.1 Ethics and Law

Effect of Time

If the law perfectly matches the moral conscience of a society, then what is illegal will be unethical too and vice-versa. But this is rarely so. Ethics change over time. While the moral conscience of the society is constantly under change, law lags behind due to delays in codification and enactment by the government(s). For example, trading of opium was earlier considered legal and ethical.** However, today it is both illegal and unethical since the society has discovered the many negative side effects of opium consumption. Sale of cigarettes is considered legal and many may consider it unethical. May be over time, even sale of cigarettes, like opium, will both be illegal and unethical.

Tacit and Explicit Codes of Ethics

Lastly, a right or wrong marketing action can either be expressly stated in some ethics code book (explicit), or can be unexpressed and intuitively understood and practised (tactic).††

To sum up, marketing ethics then can denote expressed and unexpressed standards of fair and ethical dealings in marketing which the conscience of the community may progressively develop over time.10

It is easy to see that understanding the history of the society, especially that of the proximate stakeholders in a marketing exchange—namely, the firm, the shareholders or owners, the customers, the suppliers, the middlemen, the government, etc.—is important for understanding the state of marketing ethics in that society. We will now briefly discuss the context of the Indian economy with respect to marketing ethics.

THE CONTEXT OF INDIAN ECONOMY

Indian economy is still at the crossroads of free market and state controlled enterprises. Whatever be the rationale for such a system, it does matter with respect to marketing ethics and ethical infraction. Demand has traditionally been stifled by a license raj (read supply restrictions) and we still suffer its hangover. For example, two decades ago, STD rates were as high as Rs 30 using a state-owned telecom firm. Today it is just a rupee in the same firm but under a much more liberated communications industrial system. Now, was the pricing of phone calls ethical by the state-run enterprises? Is it ethical now? Even private sector firms thrived in a climate of unethical marketing practices. Consider the scenario two decades back when interest-free deposits amounting to several millions were paid by consumers to book a scooter, a two-wheeler, or a car to manufacturers such as Bajaj or Maruti. Waiting periods for delivery often mounted to several months, at times even to years. At one point in time, interest earned from such deposits for sale of scooters or cars was a lucratively large proportion of total earnings for some manufacturers. Unethical marketing practices of state-owned enterprises abound even today. For example, consumers have to suffer substandard railway services or poor choice of variety or relatively high prices. These unethical marketing practices extend into many state-controlled enterprises that hardly face competition, for example, public transport systems such as the city and mofussilbuses, electric supply undertakings, etc.

One has to understand the possibilities for moral development and enhancement of marketing ethics in the context of the environment and the players in the marketing exchange system.

- Corrupt governments: ‘Yatha raja, thatha praja’ goes an age-old Sanskrit maxim which means the ruled will be like the rulers. India suffers corrupt politicians and a political system that easily paves way for unethical and illegal marketing practices.

- Archaic laws: India still battles with age old laws that have far outlived their utility. Major acts that govern trade are at least a century old. For instance, the Indian Contract Act was enacted in 1872 and the Negotiable Instruments Act in 1881. The spirit of the law is held by various judgments and is known as Common Law. Common Law is the minimum ethical standard evolved over time. However sadly, such ‘common law’ is beyond the reach of anybody other than the lawyers. Lastly, we still apply laws where a rickshaw puller is legally barred from owning another rickshaw.

- Lax implementation of existing laws: Inept governments, at times hand in glove with nefarious forces, coupled with a slow judicial process, paves way for grave illegal activities. Where it is the norm to play illegal, expectations of ethical practices are akin to expecting probity from a hardened thief.

- Lackadaisical consumers: Most consumers are unaware of their rights. Even if consumers are aggrieved, the culture of tolerance guides acceptance of the sub-standard. The problem is only acerbated in the rural areas.

- Lack of competition: Most industries face competition only recently. Yet demand far outstrips supply in many industries. This leads to delivery of sub-standard items at high prices and poor service.

- Very few independent monitors: Very few independent monitors such as the Common Cause (www.commoncauseindia.org) founded by S. D. Shourie exists in India for fostering ethical capacity and working against ethical infractions.

Clearly, from the above, a strong stage is set for ethical infraction. There neither appears to be an incentive, nor does it appear to be feasible to be ethical. Each player in the system contributes to ethical infraction in many ways. It starts in the b-schools that coach the future managers-to-be.

Marketing academicians in teaching, consulting or research work often give a ‘go by’, to consumers’ interests. Foundations of such leanings away from consumers’ interests are in (1) the traditional view that students are after all being trained to be employees of marketers and hence leanings towards marketers’ perspective are important, and (2) the marketing educator’s own lack of ethical capacity in marketing. Let us take a closer look at these two factors:

- Leanings towards marketers’ perspective: Research on consumer behaviour is used to teach students as to how that knowledge helps a marketer perform better at the market place. Evidently in training students, academicians take the marketers’ perspective rather than the consumers’. Consider why marketers often resort to bundling of products—the usual euphemism is ‘combo deals’. It lies in the knowledge, researched by academicians and imparted as education to the students, that consumers usually overvalue a bundle more than its individual parts. To explain, take two products A and B that the consumers value individually at Rs 10 and Rs 5, respectively. Research confirms that consumers would usually value the bundle comprising products A and B more than Rs 15. So the firm stands to gain offering products in bundles rather than individually. The issues of ethics here are subtle. Should the marketing academicians take the side of consumers or the marketers or is there a mid path? Some argue that the b-schools exist to train future employees or entrepreneurs and hence it is only expected that the firms’ perspective be taken.

- Low ethical capacity among academicians: The second cause of ethical infraction is due to low ethical capacity among the marketing faculty. Ethical capacity here would include knowledge of marketing ethics, the ability to identify situations of ethics infraction in practice and the motivation to disseminate such knowledge.

Lack of ethical capacity is not a problem with academicians alone. Marketing managers are notoriously ill-informed about the law.11 In any case we have made a case earlier that law may be even inadequate. Therefore, it is important at this juncture to discuss some norms in marketing that go much beyond the minimum moral standard called the law and guide the marketing actions in such a way that they can be called maximum moral standards.

NORMATIVE MARKETING ETHICS

Organization culture plays an important role in building ethical capacity and ethical thinking in marketing. Existence of a champion, who values ethical conduct, preferably among the top management, is crucial for fostering an organization culture that values ethics. Such a champion preferably must be young. Says N. R. Narayana Murthy, ex Chairman known for championing ethical practices at Infosys, quoting Bernard Shaw: “If you’re not an idealist in your 20s you have no heart, if you’re an idealist in your 40s you have no brain”.12

Ethics must become a part of the marketing planning process. For example, one way to instil reasonable ethical values and develop moral standards in the culture of the organization is “by using the culturally established values of an average family as a guide in determining what its reaction to society ought to be”.13 That is to say, a marketer must make and market only those products he/she would feel comfortable and safe when his/her own family uses them.

Ethics in marketing can be improved if one could deliberate on what virtues are.14 For example, thinking how the customers are being affected by each product is a good start. Marketers should not market products that retard character or virtue development. Consider the TV ad of Parle G biscuits that shows a young boy from the spectators signalling to a chess player a move that the player interprets as the winning one, but which results in a loss. The subsequent scene shows the player spying the young boy shaking hands with the opponent player and obviously is left feeling cheated. The caption shows the boy to be a genius. Ethical slips made by the brand are obvious: it shows deception and cunning as the measures of genius.

Ethical capacity is fostered when one has a caring orientation, a desire to be responsive to the interests of those likely to be affected.15 For instance, a marketer has an obligation to consider whether a consumer can make an informed choice; this means understanding whether the consumer has such capability, information, and choice. Marketers must promote consumers’ interests even without a market pressure to do so. Marketing to children and underprivileged rural sections of the society has to be carefully done.

The norms indicated above are not exhaustive at all. However, they set the stage to discuss marketing ethics in a broader context. We shall now examine this subject in detail.

AREAS IN MARKETING ETHICS

In a general sense, marketers must accept overall responsibility for the consequences of their actions. They must ensure that their decisions, recommendations, and actions serve and satisfy all the stakeholders in the society. For instance, consider the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) rule introduced in May 2006 mandating all telecom firms to ensure proof of identity and address of all new customers who apply for pre- and post-paid mobile connections. The new rule was set after the Indian intelligence inputs to the Government of India that many pre-paid mobile connection that were easily procured earlier without any proof of identity and address were being misused by terrorists and the underworld for various nefarious purposes. Now it becomes the responsibility of every telecom firm, however impractical or costly, to verify the identity and address of millions of customers who had secured pre-paid mobile connections even before the rule came into effect.

In some sense, it is difficult to codify this overall responsibility. Consider another case, that of the famous Napster, USA, an online firm that helped consumers to swap music. A slew of music production firms from the recording industry filed lawsuits against Napster, for damages running into millions of dollars, on the charge that Napster helped music piracy since it facilitated such exchange. Napster’s main argument was that, while it’s online facilities could be used just like a tape recorder or a CD burner for piracy of music, it could not be held liable for customers’ illegal action. There are some who strongly argue that Napster is liable since it knew that its Web site would be misused for such intellectual property infringements. There are many who also argue that Napster cannot be held accountable since it is the customers who had misused the site for illegal purposes, and not the former.16

The proximate stakeholders in any current or potential exchange are usually the customers, dealers (retailers, wholesalers, stockists, etc.), logistics firms, the concerned firm’s interests (shareholders), the salesmen (and other employees), the suppliers and the tax authorities. Arguably, marketing ethics should guide a marketers action in such a way that a marketing action.

- Shall not do any harm knowingly.

- Shall not knowingly promote conflict of interest.

- Is honest and fair, and perceived to be honest and fair in serving consumers or clients and other stakeholders.

- Is seen to be discharged in good faith to all the parties concerned.

- Is in line with pre established schedules of equitable fee including the payment or receipt of usual, customary and or legal compensation for marketing exchanges.

- Delivers products and services that are safe and fit for their intended uses.

- Does not deceive—especially the communications about the products and services.

- Can quickly and systematically redress greviances; for example, customer complaints management system.

- Adheres to all applicable laws and regulations.

The above tenets generally and universally lead to ethical marketing actions. Now we shall turn to specific areas in marketing that elucidate the above.

Product Development

First, the products and services have to be safe. Then they must be fit for their intended use. The marketer must disclose all substantial risks associated with products and service usage. It may include identification of any product component substitution that might materially change the product or impact on the buyer’s purchase decisions. Similarly, extra cost-added features should be identified. For example, a model of a car may be sold at some price, But a component inside, for example, the battery or AC, may be from a different constituent brand, such as Exide/Amaron, or Denso/Delphi. These sub-brands/components have different replacement prices, lifetime, time of replacement, etc. The manufacturers and service customers are aware of this fact, and such component substitution is decided based on the lowest OEM prices offered by companies.

Clearly, products such as cigarettes, ‘pan masalas’, plastic bags, guns, etc. are seen to be increasingly unethical to produce and market since they are unsafe. It is illegal to use plastic bags in major metropolitan cities. It is easy to say that these products may be banned ‘here and now’; but taking into consideration the millions of people who are employed in these industries, and the other negative side effects societies are compelled to resort to ‘slow death’ strategies. Marketers face resistances like ‘sin taxes’, mandatory warnings on side effects of consumption, ban on advertising, restrictions in usage or consumption in public places, etc., that make such products unattractive in the long run.

Marketers can also be ‘suggested’ to turn to make current products safer. In other words, they can be made to resort to alternatives that are safer. Such ‘suggestions’ can be from consumer opinion, public outcry, government sanctions, or even competitors moves, etc. For example

- Goizuetta,‡ the erstwhile CEO of Coke, in the 1980s redefined competition of Coke to be water and not Pepsi, setting a scorching pace of growth for Coke in cola markets. He even remarked in 1996 that PepsiCo was turning out be increasingly irrelevant to Coca-Cola Inc. But, PepsiCo turned the competitive heat against Coke not just in cola markets but predominantly and ironically in water. PepsiCo’s Aquafina brand of packaged water is number one in world markets. Coke was forced to enter into packaged water markets, a much safer alternative to cola.17

- Safer products from consumer opinion, by way of changes in preferences. These could be in terms of the lighter Diet Coke, etc.

- Government imposes higher taxes for non-filtered cigarettes. This forces firms to focus more on filtered cigarettes that reduce the chances of lung cancer.

- Public outcry and court intervention forced Delhi Transport Corporation to introduce safer buses. It now increasingly plies buses that run on alternative fuels like compressed natural gas (CNG) instead of diesel. It has introduced buses that are friendly to the physically handicapped.

There are many cases of marketers making products safer or marketing safer alternatives on their own volition, thus displaying ethical marketing action:

- Child locks in doors of cars; airbags in cars, etc.

- Child-proof bottle lids for products that are dangerous to children, for example, bottles of some drugs—they open clockwise.

- De-materialization of physical shares into electronic form to prevent theft and to secure other benefits.

- Many products have moved from plastic bottles to Tetra-packs that are environmentally safer.

- Star Vijay channel carries a message on the negative effects of consumption of alcohol or cigarettes whenever any scene on the air has a person drinking or smoking.

Safety is a concept that requires constant renewal of its meaning to understand the full impact in the sense of marketing ethics. For instance, in India, these marketing actions go on whether it is unethical or illegal or both:

- ‘Appy Fizz’ apple juice is packed in a bottle that resembles a champagne bottle. Children can get carried away by such packaging that paves way for easier adoption of alcoholic drinks later. Another such example is candy designed like a cigarette.

- Mono-sodium-glutamate, MSG, is a flavour enhancer in many products. It is known to have many adverse reactions, including stomach upset and allergy, and the controversy that it may be carcinogenic is still raging. In India, this product is known as ‘aginomoto’, but is in fact a brand of MSG.

- Most public and private transport vehicles carry more passengers than their stipulated capacity.

- Some motorbike brands tout its racing capacity as its unique selling proposition (USP). It is known that most metropolitan traffic cannot bear such high speeds—either it is impossible due to heavy traffic or it is likely to be unsafe for the user.

- Many popular movies carry gory fight sequences by its popular heroes, treat women in low esteem, popularize stray societal excesses as if they were the norm, etc. The negative impact of popular cinema on the society is a subject unto itself.

- Several agricultural products use harmful chemicals. Sometimes they are also genetically tampered for taste, variety and abundance in production and marketed without careful study of its side effects on consumption.

- The same product is sometimes packaged differently for different distribution channels.

Let us now examine areas in product development beyond the issue of product safety. Hastening of product obsolescence, product bundling, component substitutions, provision of unwanted features with a view to sway customers, etc. are some areas worthy of discussion.

Firms hasten the obsolescence of products by managing the timing of arrival of new products/models/styles. For instance, arrival of new models in mobile phones often impels repeat buy among the youth segment, who discard their older models much before their functional utility is diminished.

Banks in India, especially the private banks, have encouraged their customers to migrate from in-branch banking to automated teller machines (ATMs) due to the fractional cost of servicing the client through ATMs. ATM facilities are often free of charge to an account holder. Due to such encouragement and its relative advantages, customers have enthusiastically adopted the ATMs. Consider how bundling of such popular free services with less popular priced products lead to an unethical practice. ICICI Bank offers its international debit card bundled with ATM facilities for an annual fee. While customers predictably want just the ATM card, the bundling with the debit card leaves the customer with no choice but to ‘pay’ for a product that he or she does not want. Incidentally, ICICI Bank offers credit cards, a better substitute to their debit cards, to most customers on a life-time free basis.

Often, consumers face products that are priced cheap initially but its spares and consumables are priced high. An example of such captive product pricing technique is ink jet printers being priced far cheaper in relation to its cartridges. Caterpillar makes high profits in the aftermarket by pricing its parts and services high.18 Or consider optional-feature pricing where at times the base version is priced very attractive; but some add-on feature will be padded with profits. For instance, in popular makes of digi-cams, the base version is fitted with a 16 MB RAM chip that most consumers may find inadequate while using. The upgrades to higher RAM chips such as 256 MB or so are priced steep.

Sometimes customers get swayed in by a feature in a product that a firm knows that consumer will very rarely use, for example, camera in cell phones. Or sometimes consumers get features that they have not bargained for: for example, a consumer pays to watch a movie at a theatre, but unethically, advertisements are featured first. Similar questions of ethics are raised in pay channels—can the broadcaster air advertisements that the consumer has not paid to watch?

Pricing

Cost is a fact, price is a fiction. Price is the money a consumer is to pay for the value of goods and services received. Not engaging in price fixing, or practising predatory pricing, and disclosing the full price associated with any purchase can be considered ethical marketing. The following are often considered unethical:

- Increase prices and then discount—engage in bogus ‘sale’.

- Introduction discount for new customers. Reader’s Digest often resorts to such pricing.

- High prices for captive customers or on renewal for existing customers.

- Low product price but very high service costs. Consider washing machines that cost about Rs 10,000 but whose annual maintenance contract (AMC) cost about Rs 2,000. If there is no AMC, then it may cost about Rs 750 for a mere visit to diagnose the problem; additionally one would have to pay for the spares purchased.

- Cross subsidize products or services.

- Promoting ordinary product as a luxury one.

- Bundled price for fast moving products with slow moving ones.

- High prices during shortages. For example, many vegetable vendors would charge very high prices on old produce during transport strike.

- Predatory pricing: To heavily discount the offering, and drive competitors out of business—then hike prices.

- Form cartels to keep up prices. This is traditionally called price-fixing. Though it is illegal in many countries, many firms engage in it covertly. For instance.19

- Samsung, Infineon and Hynix Semiconductor formed a cartel to fix the price of dynamic random access memory (DRAM) chips.

- Between 1997 and 2000, 13 perfume brands including L’Oreal, Pacific Creation Perfumes, Chanel, LVMH’s Sephora and Hutchison Whampoa’s Marionnaud, and three vendors engaged in price collusion.

- Many retailers pass off products above MRP.

- Most autorickshaws demand high fares, regardless of the legal fares that they are allowed to charge.

- Winner’s curse: auctions are known to elicit higher prices from the consumers. This is particularly relevant with Internet-based marketing that involves bidding.

Placing (Distribution)

Distribution of products and services is transporting them from manufacturing point to the stockist, wholesalers, retailers and thence to consumers. Distribution is managing the forward flow of goods and services to the consumer and reverse flow of money from the consumer. Distribution is managed by an organized network of agencies and institutions. Recent trends are that with retailing getting more organized, their power with the manufacturing firms is increasing. For instance, arrival of firms like Spencer’s Daily, Reliance Retail, Lifestyle, etc., has shifted balance of power from manufacturing firms to retailers.

Not manipulating the availability of a product or service for the purpose of exploitation and not using coercion or undue influence on the marketing channel are certain norms of ethical marketing action. The reverse can also be considered: a large channel or retailer can coerce a manufacturer to consider unethical terms because of its large consumer base.

- Major firms coercively push a slow moving product along with a fast moving one to the retailer.

- Firms often have direct sales departments that bypass established retailers.

- Many retailers sell products that have crossed expiry date.

- Most drug stores would give innumerable drugs without prescription from a qualified doctor.

- Products are moved in unsafe vehicles—for example, cooking gas cylinders are moved in vehicles that are not designed to carry them and often they lack fire safety equipment in case of emergency.

Promotions (Advertising)

H. G. Wells once commented “Advertising is legalized lying”. Advertising uses media like the print, TV radio, billboards, etc. Ethical marketing action is avoiding false and misleading advertising. Concerns are about puffery, exaggeration, concealment of information, and psychological manipulation.

- Surrogate advertising:

- Most liquor firms carry ads of products like golfing equipment, apple juice, or soda water with prominent display of the name of the liquor brand without any reference to liquor. ITC withdrew from sponsoring the India cricket team through its Wills brand; reasons apparently are of ethics.

- Pan Parag, Chutki, and Ranjigandha are brands of pan masala (non-tobacco based) and gutkha (tobacco based). These brands freely air their brands on all media without adequately differentiating between their tobacco and non-tobacco versions. Health Ministry does not opine such ads as surrogate advertising.20

- Using irrelevant attributes in ads: Nirma used to promote its washing cake with the tagline ‘Zyada jhaag, zyada safedi—more froth, more whitening capabilities. When it was pointed out that frothing in no manner enhances product performances, Nirma and many other such brands withdrew those ads. Use of irrelevant attributes in ads abound. The italicized attributes here below are irrelevant

- Polo, a mint with a hole.

- Pears transparent Soap.

- Fair & Lovely Fairness Soap with fairness beads.

- False claims: Many B-schools claim 100 per cent placements even though in truth many seats might have been filled through not so ethical means.

The main purpose of advertising is to create awareness of the product, persuade the consumer to consider the brand favourably and remind the consumer of its existence periodically. The greatest challenge for an ad is to get noticed in a clutter of ads. Advertising professionals facing this challenge think they have a license to do anything that will make their ads noticed. But, in the bargain promotion of good quality of life, not affecting the sentiments of certain segments, culture or society is given a go by. Consequently, these professionals are often under fire for upsetting the socio-cultural-religious sensitivities and sensibilities of consumers. A research21 shows that among the important issues deliberated in advertisement ethics are use of deception in advertisements, advertising to children, racial and sexual stereotyping, advertisements affecting values of the society, use of sexual themes, advertisements affecting material wants of society and the use of fear appeals:

- Use of deception:

- Advertisers pay the search engine companies to have their products and services listed ‘high’ in the search results. Thus the listings look like information from an objective database selected by an objective algorithm. But really they are paid ads in disguise and are deception.

- Some22 opine that IIPM, a B-school with branches in several cities in India, uses in its ads good rankings of any one of its branches as if it were rankings for all its branches.

- Advertising to children: Issues23 here are very complicated and immensely serious.

- Average children under the age of 5 years cannot distinguish between commercials and programs.

- Advertisements directed to children under eight are inherently unfair, as children are unable to evaluate product claims and they trust the source of the claims.

- Children between 8 and 10 years of age can be made anxious by ads, as they know ads do not always tell the truth. Children also are aware that they do not always know when ads are truthful or not.

- Children are vulnerable to ‘host selling’ techniques (i.e., sales messages by hosts or characters from programs). These messages have authority for children.

- Children can be misled or deceived by technique (size, shape, speed, performance) used to display products to best advantage.

- Racial stereotyping: Consider ads that portray Sikhs or Parsis in ways that may negatively affect their sentiments. Or consider usage of attractive women in ads that has little connection to the product.

- Affecting values of a society: Consider the ad for Hyundai Santro’s Zip Drive that featured popular cine actor Shah Rukh Khan, zipping zig-zag to be ahead of a heavy traffic. Obviously, the brand fails to convey the importance of orderly and lane driving.

- Use of sexual themes:

- Consider the brand ‘FCUK’, originally ‘French Connection United Kingdom’ vendor of youth fashion, shoes and fragrances. It is known for its controversial ads in public places. For instance, a full page ad blared—“World’s Biggest FCUK”, announcing the opening of its biggest store to date.

- Recall the July 1995 ad for Tuff shoes that used actors Milind Soman and Madhu Sapre in a tight embrace wearing just the shoes and a python covering the bare essentials. It created a furore and the matter is sub-judice.

- Use of fear appeals:

- Life insurance firms often use fear appeals targeted at women suggesting dire consequences upon the husband’s death lest one is not insured.

- A popular fairness cream brand promotes itself by using the fear of rejection at an interview merely because one is dark skinned.

Other Promotional Activities (i.e., Excluding Advertising):

Besides advertising, firms resort to many other forms of promotions. One set of promotional tactics is to induce the customer to try or buy more of the product in a direct way. Tactics include ‘buy one get one free’, ‘Rupee off’, money off on next purchase, toys inside chips bags, free coupons, gifts, rebates, games, competition that involve slogan writing, customer loyalty programs, etc. The other set of promotions includes the way customers are induced to consider the product at the point of purchase. These include point of purchase display, danglers, store layout, etc. Promotions must not be examples of manipulations or misleads.

- Targeting child consumers is often considered a case for sales promotions that are manipulative. The main idea was to shift the focus from the parents to the children. Children may not be able to take decisions in their best interest and can be given to impulses. For example,

- A popular toy store re-laid the store layout in such a way that children could handle the products themselves, designed store carts that children could use, etc.

- The so called ‘junk foods’ often resort to promotions of freebies that are highly manipulative. For example, children often want potato chips for the toys that are promoted.

- Several ‘impulse buy’ products such as chocolates and candies are kept near the cash counters. It bears out of consumer research that for such products purchase resistance is the least when there is ‘cash in the hand’ or when the consumer is about to pay for other purchases.

- One promotion technique that may be considered unethical is the ‘loss leader strategy’. In this, one major attractive product is priced at a loss or with no profits. Consumers are stimulated to such pricing, albeit initially only for that product. But eventually, they do end up buying several other products from the store that are more profitable.

- The latest of the promotion techniques is to recruit a select set of customers themselves who generate positive word of mouth with other prospective customers, without disclosing such connection to the promoting firm.

- Another technique is to influence consumers to buy more stock that have quick shelf life. For instance, iodine content in salt deteriorates quickly. If consumers are made to buy more of the salt by inducements or offers, the packet that is consumed later will be of lesser value to consumer.

- One of the greatest concerns in this Internet era is the problem of pop-ups, cookies and spam.24 E-mail marketing, may be considered as intruding into the privacy of people.

- Use of prizes, chances and other similar techniques may be unethical if it increases the instincts to gamble.

BEYOND THE FOUR PS

Marketing ethics goes beyond the four Ps—product development, pricing, placing, promotion—discussed above. A few more aspects are discussed hereunder:

- Keeping information about the stakeholders confidential.

- Consider the case of a bank selling its customer list containing phone numbers and addresses to a communications firm that makes a contact by phone or mail to market its product.

- Some large firms often pass their client list to other divisions for cross-selling or up-selling. For instance, a bank’s insurance division may dip into the credit card’s customer list for prospecting. One or two such stray calls may not be uncomfortable to a customer; but consider a bank with ten different divisions and each dipping into the same list for prospecting. ICICI Bank recently announced that if its customers want privacy, they may log into their Web site or write to them for exclusion from such prospecting.

- Revealing the price and other terms of the lowest bidder/supplier to another preferred bidder/supplier with a view to awarding the contract to the latter is unethical.

- In marketing research/intelligence, it would be ethical to

- not sell in the guise of research;

- not subject respondents to undue mental stress in the name of research; it should not have permanent damage to any faculty of the respondent;

- maintain integrity by not misrepresenting or omitting pertinent research data;

- not hire competitors’ employees or induce competitor information by corrupting the competitor’s employees. The latter is unethical intelligence gathering.

SUMMARY

Marketing ethics denotes expressed and unexpressed standards of fair and ethical dealings in marketing which the conscience of the community may progressively develop over time. Marketing-ethical capacity would include knowledge of marketing ethics, the ability to identify situations of ethics infraction in practice, and the motivation to disseminate such knowledge. Unfortunately in India, widespread corruption, low societal moral standards, archaic laws, inept governments, slow judicial process, lack of competition, lackadaisical consumers and the way B-schools train students with marketers’ perspective leaves little room for ethical capacity in marketing to foster.

Marketing ethics and building of ethical capacity can be fostered by having a corporate culture that values ethics and a system to institutionalize and integrate ethical thinking in marketing planning. Marketing planners must articulate on virtues and not market products that retard character and denigrate value systems. Marketers must have a caring orientation and deliberate whether the customers can make informed choices.

There are many examples of firms practicing ethical marketing in India in spite of compulsions to do the contrary. There are equally many examples of firms that market unethically. Unethical marketing practices can be seen in all areas of marketing: viz. in product development, advertising, other promotional techniques, pricing, distribution, etc.

Ethics in marketing would include making safer products, not using deceptive or misleading advertisements, not indulging in hard sell, not using coercion on channel partners to push products, and not engaging in price fixing—in short, fair and honest dealings that have the customers’ and other stakeholders’ interests in mind.

KEY WORDS

Marketing ethics • Safe products • Latent needs • Financial and insurance products • Telemarketers • Safe treatments • Financial incentives • Housing solutions • Satisfying customers • Corollary • Addictive or compulsive consumption • Organizational Function • Product Development • Packaging • Branding • Advertising • Promoting • Selling • Distributing • Pricing and customer servicing • ‘Smash’ brand • ‘Pro-skin technology’ • Direct marketing • Maximum retail price • Minimum moral standards • Normative Ethics • Legal and Ethical • Shareholders • Owners • The middlemen • Liberated communications • Unethical marketing practices • State owned enterprises • Marketers’ perspective • Organization culture • Ethical capacity • Championing ethical practices • Informed choice • Proximate stakeholders • Substantial risks • Mandatory warnings • Scorching pace of growth • Flavour enhancer • Appropriate capacity • Harmful chemicals • ‘Junk’ older models • Add-on-feature • Marketing channel • Racial stereotyping • Manipulative • Impulse buy products • Marketing planners

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- What is marketing ethics? How does the element of time impact the current understanding of what is ethical in marketing?

- Visit American Marketing Association’s web site www.marketingpower.com, read the code of marketing ethics and comment.

- Compare and contrast P&G India’s ‘Purposes, Values and Principles’ (www.pg-india.com/hhcl/pvp.htm) with that of the code of marketing ethics of American Marketing Association (www.marketingpower.com).

- What is the difference between tacit and explicit codes of marketing ethics?

- How is marketing ethics different from laws that govern marketing practices?

- What is ethical capacity within the ambit of marketing ethics? Why is ethical capacity among marketing practitioners low?

- Some believe that practitioners of marketing can be trained in marketing ethics, while a few others opine that since marketing ethics is highly correlated to personal ethics, ethical capacity in marketing cannot be improved through training. Comment.

- Do you think the central axiom of marketing ‘ satisfy consumers ’ may lead to unethical marketing? Explain.

- List some marketing practices under each of the four Ps of marketing that you think are unethical in nature. Reason out why.

FURTHER READING

1. HDFC Awards and Accolades, 1999, available at www.hdfc.com/we_awards.asp

Case Study

THE COLA CONUNDRUM

(This case study is based on reports in the print and electronic media, and is meant for academic purpose only. The author has no intention to sully the image of the corporate or executives discussed)

COCA-COLA’S GENESIS AND GROWTH

Coca-cola was concocted by pharmacist John Pemberton and was first introduced as a health tonic in Atlanta, Georgia in 1885. The company claimed that its drink was a sugary medicine with several health benefits and that it could treat headaches, impotence and morphine addiction. The drink was an instant hit and became hugely popular after the company decided to serve it to soldiers serving overseas in the Second World War. Presently, the company operates almost in all countries of the world selling as many as 12,500 drinks every second. It has a slew of products with a global reach such as Sprite, Fanta and Lilt. The company makes an annual profit of approximately US$ 15 billion and has a huge marketing budget of US$ 2 million per annum.

Coca-Cola has a rather morbid history in several countries where it operates. Coke is entangled in disputes across Asia and the Americas. The company’s bottlers were fined heavily in Mexico for violation of anti-monopoly laws. In Colombia, eight employees of Coke bottling plants have been murdered and 48 went into hiding. In Pakistan, it illegally dismissed employees who called a strike, and in Turkey, riot police have been accused of violently dispersing peaceful protesters over the sacking of union leaders. In Peru and Chile, workers at its subsidiaries have gone on strike over complaints about working hours and intimidation. In Russia, it is accused by War on Want, an anti-poverty charity based in London, for opposing union organization. It is not surprising that the firm is one of the most heavily unionized multinationals in the world.

All these accusations, of course, are rejected by Coca-Cola, which insists it follows the highest ethical standards, working closely with the United Nations, trade unions and environment groups to improve its practices, and promotes the latest technical innovations. “The Coca-Cola Company exists to benefit and refresh everyone it touches,” the corporation states in its latest code of conduct.

Notwithstanding all these controversies, Coke is still the top global brand. In August 2006, Interbrand, the global brand consultancy firm and Businessweek announced the list of 100 best global brands of 2006. Coca-Cola with a brand value of around one-tenth the GDP of India (US$67 billion), has retained its position at the top despite a 1 per cent drop in its brand value.

COMPANY PROFILE

Coca-Cola, the world’s largest selling soft drink manufacturer, came to India for the second time in 1993 revitalizing the Indian soft drink market. Coca-Cola was India’s leading soft drink until 1977 when it was ‘kicked out’ of India after a new Janata Government ordered the company to turn over its secret formula for Coca-Cola and dilute its stake in its Indian unit as required by the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA). The company refused to oblige the government and preferred to leave the country. In 1993, the company (along with PepsiCo) returned in pursuance of India’s liberalization policy. On its return in 1993, it took over ownership of the nation’s top soft-drink brands and bottling network and established an iconic status in the minds of Indian consumers. Coca-Cola bought out for Rs 3500 million a clutch of popular indigenous soft drinks brands including Thums Up, Gold Spot, Limca, Citra and Maaza from Parle’s Chauhan brothers, which enabled them to corner immediately 66 per cent market share. By 2005, Coke and Pepsi together held 95 per cent market share of soft-drink sales in India. Coca-Cola India is among the country’s top international investors, having invested more than US$ 1 billion within a decade of its presence and another US$ 100 million in 2003 for its operations. Since 1993, Coca-Cola India has made significant investments to build and continually consolidate its business in the country, including new production facilities, waste water treatment plants, distribution systems and marketing channels. The vast Indian operation comprises 25 wholly company-owned bottling operations and another 24 franchisee-owned bottling operations. That apart, a network of 21 contract-packers also manufactures a range of products for the company.

The company’s claim is that it has given consumers the pleasure of world-class drinks to fill up their hydration, refreshment and nutrition needs and that it has also been instrumental in giving an exponential growth to job opportunities. With virtually all the goods and services required to produce and market Coca-Cola being made in India, the company directly employs approximately 6,000 people, and indirectly creates employment for more than 125,000 people in related industries through their vast procurement, supply and distribution system. These are only some of the facts that speak about Coca-Cola’s commitment to its long-term growth as an integral player in the Indian economy.

COCA-COLA’S CLAIM OF ETHICAL BUSINESS

Coca-Cola’s claim to ethical business is reflected in the following measures it has initiated.

Code of Business Conduct

To reaffirm commitment to ethical behaviour as an organization and as individuals, Coca-Cola issued a revised code of business conduct in 2002 to every employee worldwide. This code continues to serve as a guide to company’s actions, advancing and protecting core values of Honesty, Integrity, Diversity, Quality, Respect, Responsibility and Accountability. It presents the information in clear, easy-to-understand terms, adding procedural guidelines that establish steps for investigating and addressing possible violations of the code. It also extends its scope to the conduct of company directors, as well as employees and officers. These changes and additions make The Coca-Cola Company Code of Business Conduct, a powerful resource for protecting the company’s reputation for integrity.

Environment Policy1

Coca-Cola India is in the business of beverages that refresh people and carry out their operations in ways that protect, preserve and enhance the environment. Coke’s activities are guided by Coca-Cola eKOsystem, which provides a framework to transform this principle into actions.

The environment policy of Coca-Cola, which has been communicated to all associates of the company, promises to operate the company’s facilities taking into account all applicable environment safety and health rules. The company also avows to put in place ecologically sound objectives and targets, with a view to integrating a review mechanism for all essential elements of the company’s management. It would be the policy of the company to conserve water, energy, and fuel resources by finding ways and means of improved usage while reducing wastage to the bare minimum. As a policy, the company would promote the collection of used PET bottles through awareness programmes, and by getting better prices for the consumer for the bottles. It would try to obtain help from private, public and governmental organizations to solve environmental problems. The company promises to see that advertisements are carefully evaluated so as to avoid eco-sensitive areas, and would ensure that advertisements are not placed on historical monuments, places of worship, political buildings and structures. It would also be the avowed policy of the company to use environmentally friendly cooling equipment.

With regard to fleet operations, the company would ensure proper maintenance, improve and track fuel efficiency, and reduce waste so as to minimize environmental repercussions.

The company’s procurements policies would be such that the packaging materials used would have minimum environmental impact. The company would also ensure that all operations are eco-management system and ISO 140001 compliant.

The company’s environmental policy would be made available to the public and those who are interested in going through it.

Supplier Guiding Principles

Coca-Cola Company expects its suppliers to follow the following principles, as suppliers of products and services to the company:

Built on the Compliance of Perfection The Coca-Cola Company’s reputation claims that it is built on trust. Their business associates around the world know how they are committed to managing business with a consistent set of values that represent the highest standards of quality, integrity, excellence, compliance with the law and respect for the unique customs and cultures in communities where they operate. They seek to develop relationships with suppliers that share similar values and conduct business in an ethical manner.

Relationships Built on Good Corporate Citizenship As part of ongoing effort to develop and strengthen their relationships with suppliers, the company has introduced the Supplier Guiding Principles Programme for direct suppliers to the company. The Supplier Guiding Principles Programme is based on the belief that good corporate citizenship is essential to their long-term business success and that it must be reflected in their relationships and actions in the marketplace, the workplace, the environment and the community.

Shared Values, the Foundation of Relationships Recognizing that there are differences in laws, customs and economic conditions that affect business practices in various parts of the world, The Coca-Cola Company believes that shared values must serve as the foundation for relationships between them and the suppliers. The Supplier Guiding Principles restate the company’s requirements and emphasize good workplace policies that comply with applicable environmental laws and with local labour laws and regulations.

Workplace Practices The Coca-Cola Company supports fair employment practices with employees with a commitment to human rights, at the workplace. It provides a safe working environment and abides by all applicable labour laws in countries addressing working hours, compensation, and employees’ rights to choose whether to be represented by third parties, and to bargain collectively. It creates a workplace where individuals are treated with dignity, fairness and respect. It recognizes value, respects and celebrates the cultural differences and diversity of the background and thought of employees.

Communication The Coca-Cola Company expects sup pliers to communicate these Guiding Principles for Suppliers to their employees. These principles should be provided in the local language and posted in an accessible place. The company also expects suppliers to develop and implement appropriate business mechanisms to monitor compliance with these guiding principles.

Work Environment The company expects suppliers to judge their employees and contractors based upon their ability to do their jobs and not upon their physical and/or personal characteristics or beliefs, affirming the principle of no unlawful discrimination based on race, colour, gender, religion, national origin or sexual orientation.

Health and Safety The company expects suppliers to provide a safe workplace with policies and practices in place to minimize the risk of accidents, injury, and exposure to health risks.

Child and Forced Labour; Abuse of Labour The company neither expects their suppliers to employ anyone under the legal working age nor to condone physical or other unlawful abuse or harassment, or the use of forced or other compulsory labour in any of their operations.

Wages and Benefits The company expects suppliers to compensate their employees fairly and competitively relative to their industry in full compliance with applicable local and national wage and hour laws, and to offer opportunities for employees to develop their skills and capabilities.

Collective Bargaining In the event their employees have lawfully chosen to be represented by third parties, the company expects their suppliers to bargain in good faith and not to retaliate against employees for their lawful participation in labour organization activities.

Environmental Practices

The Coca-Cola Company expects suppliers to conduct business in ways that protect and preserve the environment. At a minimum, they expect suppliers to meet applicable environmental laws, rules and regulations in their operations in the countries in which they do business.

Compliance with Laws and Regulations

At a minimum, suppliers to the Coca-Cola Company and suppliers authorized by the company will be required to meet the following standards with respect to their operations as a whole:

- Supplier will comply with all applicable laws, rules, regulations and requirements in the manufacture and distribution of the company’s products and supplies, and in providing services to the company

- Child labour: Supplier will not use child labour as defined by local law

- Forced labour: Supplier will not use forced or compulsory labour

- Abuse of labour: Supplier will not physically abuse labour

- Collective bargaining: Supplier will respect employees’ rights to choose whether to be represented by third parties and to bargain collectively in accordance with local law

- Wages and benefits: Wages and benefits will comply with local law

- Working hours and overtime: Working hours and overtime will comply with local law

- Health and safety: Working conditions will comply with local regulations

- Environment: Supplier will comply with all applicable environmental laws

These minimum requirements will become part of all new or renewed commercial agreements between the Coca-Cola Company and their direct suppliers. Suppliers must be able to demonstrate their compliance with these requirements at the request of and to the satisfaction of The Coca-Cola Company. The Company has the right to inspect any site involved in work for it, and any supplier that fails to satisfy the company of its compliance is subject to termination of any agreements between it and the company.

Quality—Business Objective

The Coca-Cola Company exists to benefit and refresh everyone it touches. For them, quality is more than just something they taste or see or measure. It shows in their every action. The company relentlessly strives to exceed the world’s ever-changing expectations because keeping high quality promise in the marketplace is their highest business objective and their enduring obligation. “Consumers across the globe choose Coke brand of refreshment more than a billion times every day because Coca-Cola is

- The Symbol of Quality

- Customer and Consumer Satisfaction

- A Responsible Citizen of the World”.2

Promise

The basic propositions of Coca-Cola’s business is simple, solid and timeless. When they bring refreshment, value, joy and fun to the company’s stakeholders, then they successfully nurture and protect their brands, particularly Coca-Cola. That is key to fulfilling their ultimate obligation to provide consistently attractive returns to the owners and to their business.

WORLD ENVIRONMENT FOUNDATION AWARDS 2005

The World Environment Foundation (WEF) awarded the prestigious Golden Peacock (Environmental Management) Award 2005 (GPEMA) to the Coca-Cola bottling plant at Kaladera near Jaipur in recognition of its world-class environment practices. Coca-Cola India’s ultra-modern ISO 14001 certified bottling plant in the state of Rajasthan won this top award in the medium-scale food and beverage category from amongst more than 17 entries. Some of the environmental performance monitors are: energy use, water use, wastewater discharge, compliance with government regulations and positive impact on local community.

The GPEMA is designed to encourage and recognize the effective implementation of environmental management system. The Coca-Cola Quality System (TCCQS) is an all encompassing management system (Total Quality) covering environment management and other business aspects such as safety and loss prevention (SLP), product quality, packaging quality, process capability improvement and customer satisfaction.

COCA-COLA’S UNETHICAL PRACTICES

The forgoing passages express the claims of the Coca-Cola Company about the ethical manner in which they do their business. However, there have been several complaints against the manner of the company’s operations and its business in India.

Lack of Transparency and Accountability

The question of transparency and disclosure in accounting presentation becomes more acute in the case of public limited companies that are accountable to their shareholders. What if the companies are not listed on the stock exchanges and there is no accountability to the investors? This leads us to a pertinent question. Is this the reason why several multinationals desist from listing in the Indian bourses? Companies ranging from Cadburys to Philips have de-listed themselves and some of the major Indian MNCs like Pepsi and Coke have chosen to stay away form the Indian stock exchanges. Only if they are listed they will have to adhere to Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement, under which they have to abide by corporate governance practices such as integrity, transparency, full disclosure of financial and non-financial information, etc.

From a larger national perspective, delisting of well-managed companies depletes the wealth creation capacity in the Indian stock markets. Stock markets are important creators of wealth and also act as barometers of corporate performance. Being listed increases the transparency and disclosure levels of companies. Markets provide an automatic regulatory mechanism. For instance, not much is known about the financial health of the two cola giants, Coca-Cola and Pepsi. One can only make estimates. In fact, the fear of disclosure may be one of the reasons why Coke is reluctant in coming out with an IPO for more than the past 10 years despite tremendous pressure from the government.

Reluctance of getting listed by many multinationals such as Coca-Cola in Indian capital market is seen with suspicious eyes.

- Listing of the company brings transparency in its operations and accounting policies. Unlisting of companies enables enough flexibility to companies to hide their unethical decisions and wrong policies.

- Listing is essential as it curtails the unethical practices followed by companies to kill competition. For example, if Pepsi and Coca-Cola are listed companies then it will give a true picture of the manufacturing cost of concentrates vis-à-vis the pricing policies followed by these cola majors to create strong entry barriers for new players.

- Listing of companies makes managements more accountable to interested groups, as the management is expected to justify its actions and results achieved, in every general meeting. Once de-listed, the company would escape the scrutiny of the investors, analysts and the media.

Lack of Ethics in Marketing

Multinationals such as Pepsi and Coca-Cola have been accused of adopting unethical marketing practices such as the following:

- Offering products/services against the broader interests of the society. Not every product is useful to all.

- Discriminatory pricing: Uniform pricing is not followed and some customers end up paying more than others for the same product product/service.

- Making tall claims in advertising

- Deceptive sales promotions

- Targeting inappropriate audiences such as children who are gullible and quick to develop brand loyalty, impressed by colourful television visuals and catchy jingles.

Unhealthy Practices

As the largest seller of soft drinks in the world, the Coca-Cola Company has been the subject of various allegations such as monopolistic practices and racist employment practices. In India, the company has provoked a number of boycotts and protests as a result of its perceived low health and hygiene standards and adverse impact on the environment. A survey of 16 Coca-Cola bottling plants in the country showed that the effluent sludge of eight was found to have high levels of cadmium, lead and chromium. The contamination by these elements was much more in excess to the acceptable Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) standards.3

Unhealthy Nature of Colas

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in Mumbai has advised schools to ban the sale of colas, and also prevent any advertisement of aerated drinks in their premises. FDA Commissioner Ramesh Kumar warned that soft drinks cause obesity and tooth decay, besides posing other health risks due to the presence of chemicals, such as Lindane, a confirmed cancer-causing chemical, Malathion, DDT and chlorpyrifos.

American epidemiologists have reported recently that colas are associated with bone mineral density loss and their consumption may increase osteoporosis risk for older women. Osteoporosis is a disease of porous and brittle bones that causes higher susceptibility to bone fractures. Katherine Tucker, director of epidemiology at Tufts University, and her team of researchers reported that in women, cola consumption was associated with lower bone mineral density, regardless of factors such as age, menopausal status, total calcium and vitamin D intake, or use of cigarettes or alcohol. However, the researchers did not see an association with bone mineral density loss for women who drank carbonated beverages that were not cola.4

Practices Inimical to Stakeholder Interests

Challenged at Shareholders Meeting The Coca-Cola Company came under attack on 20 April 2006 at its shareholder meeting for not disclosing the full extent of the liabilities the company has incurred in India.5 The company was challenged for misleading its shareholders.

Misleading Public on Water Issues The Coca-Cola Company places full page advertisements in campus newspapers across the United States—suggesting that the company is a leading steward of water resources, though the facts tell a very different story, a story of an extremely unsustainable relationship with water, especially in developing countries like India and Colombia.6

University of Michigan Acts Against Coca-Cola In a massive victory for the campaign to hold Coca-Cola accountable, the University of Michigan has suspended business with the Coca-Cola Company in December 2005 because of the company’s egregious human rights and environmental practices in India and Colombia. The victory came after a prolonged campaign by students at Michigan to sever business ties with the company until it cleans up its act in India and Colombia.7

Speaking Tour Action Against Coca-Cola From 4 to 19 April, 2005 a speaking tour to hold Coca-Cola accountable was held through public events on the East Coast including New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Philadelphia to bring attention to Coca-Cola’s crimes against humanity, particularly in Colombia and India. The tour stopped at Coca-Cola’s shareholder meeting in Wilmington on April 19. April 2005 had been designated as the month of action against the Coca-Cola Company for its crimes against humanity, and a series of events was held around the world to demand justice for Coca-Cola affected communities.8

Coca-Cola Challenged on Human Rights Abuses The Coca-Cola Company’s shareholder’s meeting was taken over by shareholder activists strongly condemning Coca-Cola’s crimes in India and Colombia. Speaker after speaker brought attention to Coca-Cola’s major liabilities in India and Colombia. College and university students, in particular, have played a key role in bringing the campaign to the limelight.9