CHAPTER 5

Social Groups: Conceptual Framework

Society is a complicated web of social relationships that are both formal and informal. These relationships exist between (i) two or more individuals, (ii) between individuals and groups, and (iii) between different groups.

The entire community, or even society as a whole, is a group; in fact, these entities can be seen as a ‘group of groups’. A society’s interactional field consists of groups—formal and informal, of alliances and coalitions, and social networks. They form the structure of a society.

Groups exist as relatively permanent entities. Individual members come and go. The arrival of new members or the departure of old ones changes the demography and actual composition of the group, but the continuity of the group remains intact. We have elaborated this point in Chapter 4 while discussing the concept of society.

Let us understand this feature through an example. In the India of today, there are many who were not around in, say, 1947; and many who were there then are gone now—they are either dead or have left the country to settle abroad. But these movements have not diminished the identity of India as a society. In the same fashion, a group’s life can be longer or shorter than the life span of any particular member. Although groups are relatively permanent, they can also cease functioning and new groups can emerge. The longevity of groups differs; groups such as a society have greater longevity, but other groups within the society may have a shorter life span, depending on the purpose for which they are constituted. The birth and death of groups, or changes in their membership profiles, are part of the dynamics of social change.

In this chapter, we shall elaborate upon the concepts of group, alliances, coalitions, and networks.

What Is A Group?

There is no dispute in calling society a ‘Group’. However, we must make it clear that while every society is a group, not every group is a society. A society is a special type of group; it shares the characteristics of a group, but possesses additional characteristics that are found only within it.

A football team, a club, a political party, an assembly of people, a picnic party, a family, and similar other collectivities are all groups. The common point between them is that each contains a plurality of interacting individuals. The individuals can simultaneously be members of other groups.

Groups generally disallow members from being members of other groups of the same type. A member of a particular society, for example, cannot be a member of another society. Similarly, a follower of a particular religion cannot follow another religion at the same time. But a person can choose to opt for citizenship of another society or membership to another faith. However, dual membership is not permitted. While a system of dual citizenship1 does exist in some countries, such dualities come with certain restrictions, for example, it may waive the precondition of obtaining a visa, but not allow the dual citizen to vote, as voting right is restricted to only one country.

Since a person at any given point in time is a member of several groups of different types, the duration of that person’s active participation in any group may be limited. Participation in other groups requires people to be mobile. However, a person is identified with that group in which s/he spends most of her/his time. A politician may be identified with the political party to which he belongs, but he may also be a member of a literary club, head a governing board of an academic institution, and be a functionary in an NGO. But he will still be known by his status as a member of the political party to which he belongs—the Congress, or BJP, or BSP, or Trinamool, or CPI.

Take yet another example of students in a class in college. The class consists of all students studying the same subject. The teacher taking the class also becomes a member with a definite set of role expectations. However, the teacher moves from one class to the other after the lecture. Similarly, a student goes to another class after the period is over. Student Malti may have chosen economics, sociology, and Hindi literature. Another student, Sakshi, may have a different combination, where Hindi might be replaced by geography or English literature. Thus, both Malti and Sakshi have sociology and economics in common, but belong to other classes for the other optional courses chosen by them. The composition of each subject class will, thus, differ in terms of the student population, and the teachers teaching those courses. These classes may be composed of students of both sexes, or of any one sex, and the relationship between students in the context of the class is governed by the core concern of the class, namely, receiving tuition from the teacher.

Constant interactions in class may also result in the formation of informal friendship groups; students coming from the same native place, or speaking the same mother tongue, or residing in the same hostel, or sharing some other common interest (cricket, or poetry, or political preference) tend to develop such groups with more frequent interactions.

Compare a group within a society with society itself. A society is also composed of people of both sexes—this is not necessary for every group—and the members are in constant interaction. However, a society differs from other groups because of its exclusive membership—an individual cannot be a member of another society; if a person resides in another society, s/he is regarded as an ‘outsider’ or a ‘migrant’ in that society. If s/he decides to become a member, her/his membership from the society of origin is transferred, and s/he is then ‘naturalized’. Thus, a society is an all-encompassing arena of social interaction, and most other groups form its parts, as sub-systems.

The classificatory category ‘group’ is a term broader than society. Its definition comprises of those general attributes that are applicable to all kinds of groups. Additional characteristics help to make the group much more specific. This is the general principle of classification. To illustrate, let us take the term ‘furniture’. This term refers to all types of furniture—tables, chairs, stools, etc. A chair is a piece of furniture, but all pieces of furniture are not chairs. In the same way, while all the cases mentioned above are groups, each has a distinctive character. A picnic party is a special group, organized for the ex-press purpose of going out for a picnic. A class, similarly, is a group organized with the purpose of providing tuition in a given subject to a plurality of students. A society also fulfils every criterion to be classified as a group, but possesses some distinctive features in addition to the basic characteristics of a group.

Groups can be as large as a society, or as small as two individuals in a well-defined, permanent relationship. Groups within society are therefore sub-systems of a society, in the sense that its membership is drawn from within the society. The group functions within the broad framework of the society and maintains its relations both with other groups and with non-members.

Groups can also be formed at a supra-national level. The United Nations, for example, is a group. We often read about G-77, or G-9, or G-20,2 or the Non-Aligned Group. These are groups at the international level, comprising a set of countries—77 or nine or 20—who come together for a common cause. Thus, groups can be formed by individuals or by agencies. Of course, participants always remain individuals—either in their personal capacity, or as representatives of an agency, an organization, or even a society.

Some groups have wide-ranging areas of interaction, while others have very specific and specialized, and thus limited, areas of interaction.

Groups may be formal or informal. A member of a society participates in both types of groups. In formal groups, participation is basically of two types: persons participate (i) as members—either voluntary, or as employees of the formal group; and (ii) as clients of the organization, for example, a citizen visiting a government office, a customer going to a firm, or a representative of another firm visiting his counterparts. The second type of interaction may be called interaction between an outsider and a group or its designated representative; the interacting parties, in this case, do not form a permanent group.

‘A social group arises when a series of interpersonal relationships, which may be defined as sets of reciprocally adjusted habitual responses, binds a number of participant individuals collectively to one another’ (Murdock, 1949: 3). A group is thus a complex of social relationships between two or more individuals operating in a given frame of reference. The analysis of a group would require focus on individuals who constitute the collectivity, the goals, the means and the conditions under which the group operates to achieve its goals. Thus, a group represents a special type of relationship. On a broader canvas, we can say that social relationships vary from tenuous and transitory interactions to ‘permanent’ systems of interaction. Parties to a social relationship may be friendly or unfriendly. The relationship between opposing armies is also a social relationship. But a group is formed only when the relationships are complementary and cooperative.

Running through the characteristic features of a society, we can locate the attributes common to all groups.

A well-defined territory, our first characteristic, is not necessary for all groups. This, however, is not to deny the designation of group to an entity that has a territorial base.

The second characteristic, namely, that it consists of persons, is valid. But note that while a society’s membership has to be bi-sexual, allowing for sexual reproduction (of course, in accordance with well-defined norms), a group’s composition may, or may not, comprise both sexes; not all groups are self-generating entities in terms of the renewal of membership.

As members of a group, each individual is recognized as the bearer of a common status, that of a ‘member’. Of course, within this group members may occupy different positions, such as president, secretary, treasurer, coordinator, etc. An aggregate of people may be found in a togetherness situation and in a group situation.

While people in a group also come together, all aggregates of people who come together do not constitute a group. For example, people travelling in a bus are together, but they do not automatically form a group.3 It is when togetherness gives rise to a ‘sense of belonging’ that a group is formed. For example, if the people travelling in a bus feel irritated by the behaviour of the conductor and somehow join hands to voice their discontent against him, they move towards a group formation. They might halt the bus, sit on strike, shout slogans, or write a joint petition against the conductor, which they submit to higher transport authorities—all these actions would pave the way towards group formation. Similarly, all office-goers from a given colony may agree to hire a chartered bus on a monthly basis, and thus form a group of bus travellers.

Thus propinquity, social proximity, and a commonality of interests are essential for group formation.

Informal groups have loosely defined boundaries. In the case of a formal group, the boundaries are somewhat well defined. A group’s social boundary is carved by its members. Members are distinguished from non-members. The selection of a group may or may not depend upon its members’ preferences. One may prefer to seek admission to a prestigious school, but may not get admission for one reason or the other; in such a case, the student joins an institution where seats are available. In both cases, the new member enters as a stranger, but gradually becomes a familiar face and develops his own friendships within the formal setting.

In formal groups, membership is acquired through a procedure, after which a membership ID is granted. But in many groups, there is no such identification. Confirmation of membership is done by (i) self-definition, and (ii) definition by ‘others’. These others are of two kinds: (a) those who are also members, and (b) those who are not members. A person becomes a member of a group when he announces his affiliation, and this affiliation is acknowledged by others belonging to that group, as well as by those who do not belong to it. When there is correspondence in the three sets of responses, the membership of a person is firmly established.

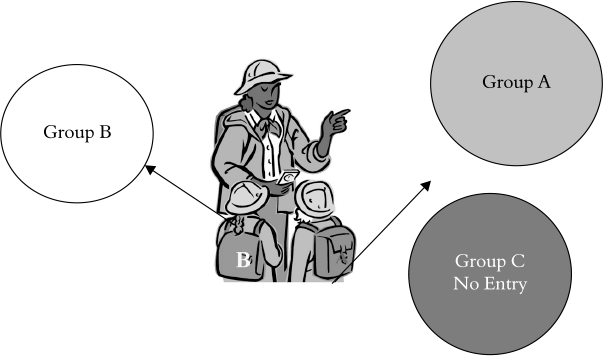

An example: If a person says that he resides in Colony A, confirmation is then sought by verifying whether other residents of Colony A accept him as a resident, and whether residents of other colonies also state that the person in question belongs to Colony A, and not to their respective colonies (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Individual as Member and Non-member of Groups

Note: The person is claiming that he belongs to Group A. This will be confirmed when (i) those who belong to Group A allow him entry; (ii) those of groups B and C say that he does not belong to their respective groups, and—this is important—that he belongs to Group A.

A member is thus an insider. Non-members, likewise, are outsiders in the context of a particular group. In 1906, William Graham Sumner made popular the distinction between an in-group and an out-group. In common parlance, people refer to ‘we’ and ‘they’. This ‘we-ness’ is the characteristic of an in-group. It must, however, be stressed that orientation towards any out-group is not always hostile. Members on the margins of a group might be ambivalent towards the in-group and somewhat favourable in their attitude towards an out-group. Thus, the degree of ‘we-ness’ may vary among members of an in-group. The more coherent and integrated groups will have a high degree of ‘we-ness’. The degree of ‘groupness’ depends upon the extent of interaction between its members. It may be less in a newly formed group or in a group on the verge of liquidation. It is, however, also possible that a newly formed group might possess a high degree of ‘we-ness’; this is quite often the case in a break-away group. Renegades4 are generally more committed to the new group than are the original members. There is a saying in Hindi: ‘Naya Bhil Musalman Banta hai to din men das baar namaz padhata hai’—which literally means that a new religious convert offers prayers many more times than older members of the faith.

It must again be stressed that while all groups are a complex of social relationships, not all social relationships can be termed groups. For a social relationship to become a group, it is essential that it have a certain degree of permanence, with frequent interactions. When two individuals meet casually in a marketplace, they enter into a transient relationship. But when they start meeting frequently with a common intent, the relationship transforms into a group. A boy and a girl may date and develop a relationship, but they become a group—a married couple—only after their wedding, which bestows a certain degree of permanence on their relationship.

Groups also change their characters. A married couple, for example, is a group, a conjugal unit. It transforms itself into a family when the couple have a child.5 The transformation of a conjugal unit into a family changes the nature of that particular group.

There is another point: while the composition and character of a ‘real’ group might change, the structural categories remain, and are peopled by another set of individuals. A particular conjugal unit of Mr Y and Mrs A may transform into a family when they have a child S—born to them or adopted by them. But their move to a family does not imply a disappearance of the conjugal unit. The same is true of the sociological category of family. A particular family may disintegrate through separation, death of a member, or divorce. But the structural category of family continues to exist. That is why it is said: a family is dead, long live the family.

A group is differentiated from a crowd in the sense that while a crowd is an assemblage of people, it is not a permanent unity with a well-defined pattern of interaction and criteria for membership.

Similarly, a group is different from a category. Women, youth, farmers, workers, students are categories and not groups. They are referred to as groups in statistical terms, or as collectivities bearing some common characteristic/s. There are no gatekeepers for vocational categories to verify the credentials of those entering its folds. And people falling within these categories can belong to different groups. This is also true for the category of women, which is based on gender; however, it will be wrong to assume that they form a single group. Even when groups are formed on the basis of a specified characteristic, such as being a woman, or a farmer, or black, not all people bearing that characteristic automatically become members of that group. They have to express their desire to become a member, and the authorities of the group in question have to accept their eligibility. A terrorist group, to take yet another example, may consist of people belonging to one faith, but not all people pursuing that faith become members of that terrorist group. The criteria of self-definition and definition-by-others will have to be employed to determine the membership of any particular individual to the group in question. This cannot be done for a category. When political leaders mobilize people belonging to a particular category, they take the first step towards converting that category into a group.

It is quite likely that a category might transform into a group with varying degrees of permanence. For example, ‘students’ constitute a category, but students of a particular college, or of the city, may form their own Association. In such cases, membership is obtained from the category of students. In the Indian context, one is familiar with the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) or the Students Federation of India (SFI), for instance, students of a given college or university may be divided in terms of their membership to any of these groups; that is to say, a college or a university may have wings of the ABVP and SFI, and students may opt to join any of them or remain unattached.

We also notice that many associations provide membership, even offer leadership, to persons who technically do not belong to that category. In India, politicians have assumed the leadership of trade unions. V. V. Giri, one of our past presidents, was known as a trade union leader. Similarly, George Fernandes led the trade union of railway workers, although he was never a railway employee. The President of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) need not be a cricketer himself. Non-sportspersons may head the olympic association’s national chapters.

It can, therefore, be said that a group is defined by three characteristics—continuous interaction, cooperation, and a sense of belonging; of course, these are highly variable. The intensity of interaction may differ; cooperation is generally crossed by conflict, giving rise to factions or dissident groups within a group; and the sense of belongingness, the ‘we-ness’ may vary from member to member. Variations in the three attributes found in a group help us classify groups into different types. Due to the varying presence of these three attributes, it can be said that actual groups demonstrate different stages of ‘groupness’. While a highly integrated group is clearly visible and observable, a group with limited and infrequent interaction defies easy identification. Several informal groups are those in which members do not know that they are operating in a group setting. Researchers employ the technique of sociometry6 to unearth such informal groups within formal groups, like a school class, a branch of an office, etc.

It is participation in different groups that shape an individual’s personality. Obviously, the amount of influence a group exerts on a particular member depends on the degree of that member’s involvement in the activities of that particular group. Not only do groups influence the personality make-up of their individual members, members also equally influence the character of the group through their participation and contribution.

When the volume of interaction with outsiders increases, the formal organization has to come up with innovative ways to handle the excess work, resulting in a reorganization of the various departmental activities, introduction of a machine culture (computers, for example), and amendment in the prescribed procedure.

This is clearly visible in the field of education. Entrance tests are now conducted jointly for a number of identical institutions of higher learning during admissions; and online tests are administered to eliminate poor candidates and invite a select number of applicants for the final interview. This was not necessary earlier, when the number of aspirants for higher education was limited compared to the number of seats available.

Sociological research has also drawn attention to the fact that while the statuses and structure of the groups may remain the same, their culture gets defined by the actual occupants of the various statuses within the organization/group. This is true of both formal and informal organizations. For example, while the structure of a cricket team remains the same—the number of players, the team hierarchy in terms of skipper and vice skipper, etc., the specialization in various departments such as bowling, fielding, and batting—teams are differentiated in terms of the person-sets, that is, by those who occupy particular positions or who play particular roles. It is this assessment that determines their worth in an auction like that of the Indian Premier League (IPL)7 where Sachin Tendulkar or M. S. Dhoni, or Ishant Sharma are offered huge sums because of their good performances on the cricket field, either as batsman or bowler. This fact has led some sociologists to distinguish between prestige and esteem; prestige is derived from official status, but esteem is earned by a status occupant from his performance. A prime minister, to take another instance, is judged as good or bad, or strong or weak in terms of his/her performance, and that determines the esteem s/he commands among the electorate.

Elaborating this point, Johnson says:

[A] group does not cease to exist when its members leave one another temporarily. If the football player goes home early from the dance in order to keep in training, he is acting at the moment as a member of the football squad. Thus the football team exists continuously, even though the duties of its members do not require their attention at every moment. At times, a particular group membership is quiescent or dormant in one’s personality, but during those times it is still ready to assert its claims, so to speak, if a proper occasion should arise (Johnson, 1960: 6).

Using the IPL example, we know that Rahul Dravid—a prominent Indian cricketer—returned from South Africa during the May 2009 matches to be with his pregnant wife who was due to deliver; but he went back soon after and joined the team again. In South Africa, he could not forget his status as a husband, and back home, he was keenly following the IPL series. The two groups influenced his behaviour and performance in the two status positions he held simultaneously.

Every individual plays a given role at a particular time, but also vicariously performs other roles attached to his/her other statuses. An individual is thus a bundle of statuses, and the roles associated with them shape that individual’s personality. We shall elaborate this aspect of social structure in Chapter 7.

Group Size And Type Of Interactions

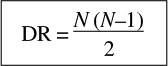

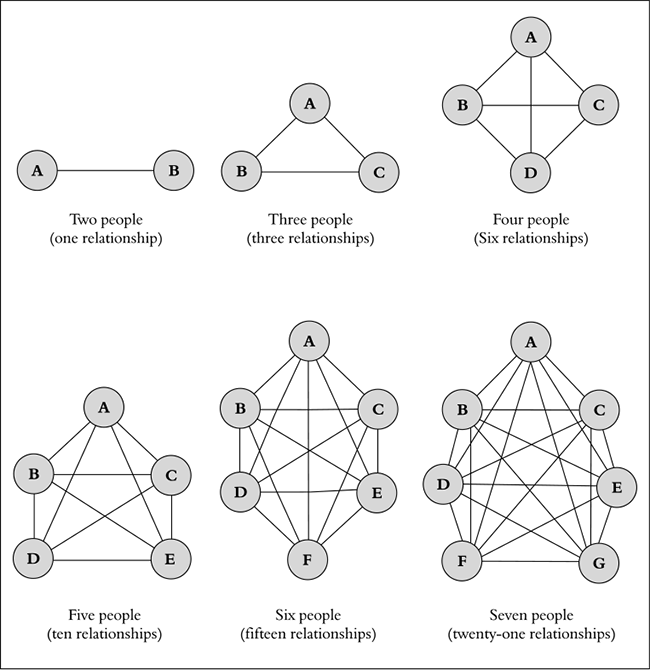

The size of a group influences the web of relationships within it. The larger the group, the greater the sets of interpersonal interactions and the more complicated the nature of its organization. A two-person group has the smallest number of interacting lines. As the size increases, so does the number of relationship structures. Sociometric charts are used to investigate such patterns. Such dyadic relationships (paired relationships) in any group depend upon the number of persons forming the group. The logically possible dyadic8 relationships in any group can be determined by using the formula:

in which N stands for number of people in a group, and DR stands for dyadic relationships.

Consider the mathematical number of relationships among two to seven people .... (T)wo people form a single relationship; adding a third person results in three relationships; adding a fourth person yields six. Increasing the number of people every new individual can interact with everyone already there. Thus, by the time seven people join one conversation, twenty-one ‘channels’ connect them (Macionis, 2005: 168–69).

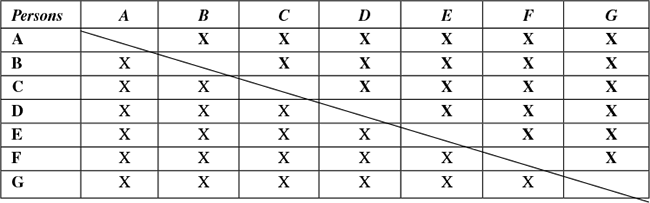

To demonstrate this, let us construct a 7 × 7 matrix (see Table 5.1).

It will be noticed that on each side of the diagonal are 21 boxes marked with X—the total number of possible dyadic relationships in a seven-member group. Although one can stretch this and work out such relationships in any size of the group, in reality many of those logical boxes will remain empty in terms of actual interactions. Thus, this technique is employed only for small group research. Diagrammatically, this can be shown in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 Group Size and Relationships

Source: Macionis, 2005: 168

Table 5.1 Mathematical Number of Relationships Between Two to Seven People

Sub-groups

When a group is created within a group, it becomes a sub-group, and the actions of the members of this sub-group remain primarily oriented towards the main group. The activities carried out within the sub-group are specialized and are functional for the larger group of which it is a part. But the formal group, particularly the larger one, allows or facilitates the formation of several small informal groups or friendship circles. In an office, one may notice that during lunch break, a small number of officers of identical9 rank assemble to have lunch together, and share their lunches. The lunch session also gives them an opportunity to engage in conversation on a wide variety of topics, not all necessarily linked to their office. These lunch groups discuss personal and familial problems, national and international affairs, and at times, intellectual topics as well. Thus, such a group, composed of the members of a common formal group—a bureaucracy—is not a strict sub-group of the former, but is primarily united by that bond.

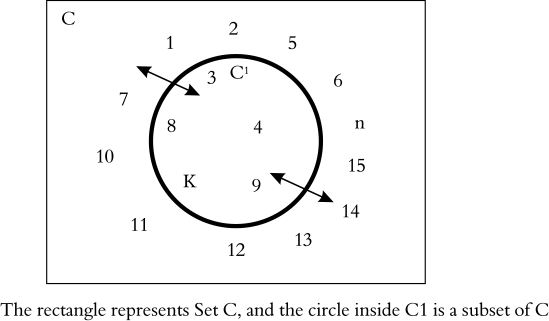

When a sub-group becomes self-contained and insulates itself from the main group, it begins to assume the characteristics of a group; when the insulation creates an insurmountable boundary, the original group’s boundaries are also redefined through the exclusion of the portion of insulated boundary of the former sub-group. This can be explained through a Venn diagram.

Suppose there are four groups called A, C, C1 and C2. In order for C1 and C2 to be proper subsets of Group C, it would be necessary for each element of C to also be an element of C1 and C2. In other words, a subset always falls within the boundary of the set. But when a group begins to share the elements of two or more sets, it heralds the beginning of a new formation of the set—as a hybrid progeny. In terms of set theory, this may be written thus:

Let there be a group called C.

In this case, C1 is a subset of C because the elements of C1 are contained in C (see Figure 5.3).

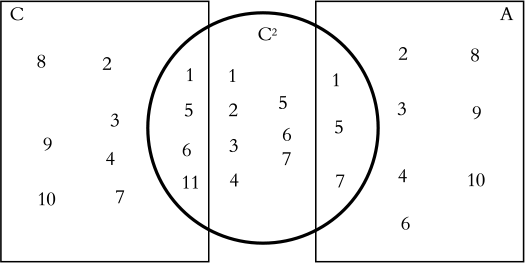

But suppose there is another group, C2, such that it has the following internal structure:

In that case, it may be a breakaway group either of Group A or Group C, trying to move into the other group and deserting the parent group (see Figure 5.4). Such a group is not, strictly speaking, a sub-group of either, but is a processual product of secession and aspiration to join another group, or become marginalized and form a group of its own.

Thus, it emerges that a person can be a member of a number of groups at the same time. Of course, membership to any particular group gets activated when the person participates in that group; otherwise it remains dormant.

It should be remembered that such dual membership depends on the kind of groups we are referring to. Some groups allow such dual membership in the same domain. Other groups belonging to different domains, have no problem with multiple memberships. Non-resident Indians now being granted dual citizenship—that of their country of residence and that of India—offer a good example. Such people are given a Person of Indian Origin (PIO) card or an Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) card.10

Figure 5.3 Rectangle Representing Set C

Figure 5.4 Set C, Set C2, and Set A

Note: C2 is neither a subset of C, nor of A, though some of its members are drawn from C and A, respectively. In this case, 1, 5, 6, and 11 of Set C constitutes a subset of C; similarly, 1, 5, and 7 of Set A are a subset of A. But these two subsets, plus the remainders of Set C2, constitute the different set we have called C2..

Each of us can supply examples of multiple memberships as we all belong to several groups at any given point in time. An individual ‘I’ belongs to her family, her class at school (if the school is treated as a group, then class becomes a sub-group), a playgroup, a political party, and so on. In this sense, an individual is regarded as a bundle of statuses and roles. It is like ‘well-wrapped sliced bread’; while each slice represents a status, the entire piece is identified as bread. Since the statuses remain more or less stationary but their occupants change, sociologists focus on statuses and positions in groups rather than on individuals as analytical categories. The personality of an individual—which is the subject matter of psychology—is shaped by a person’s participation in various groups.

This brings us to another logical inference. The participation of an individual in any group setting is influenced not only by what happens within the group, but also by the totality of other memberships held by that particular individual. The performance of a player in the field, for example, is not only affected by the attitude and behaviour of others in the team, or the rival team, or field conditions, but also on the other engagements of the player in other groups. If the father of a given player is on his death-bed, the latter’s concentration in the game might naturally be affected. The presence or absence of the player’s sweetheart in the stadium may have an effect on the player’s performance. Thus, other groups vicariously intervene in the functioning of a particular group, and in the participation of its member. When an officer’s behaviour on a given day is somewhat rude, his subordinates might attribute it to a bad start at home—perhaps a quarrel with the wife!

It must be stressed that an individual’s personality is shaped by the kind of statuses he holds and the roles he plays relative to each status.11 In different situations relevant statuses come into play when others become secondary and lie dormant. While playing cricket, for example, Sachin Tendulkar’s image of a master-blaster reigns supreme, while his other statuses as an Indian citizen, a husband, owner of a prestigious restaurant, and so on remain secondary, although not inconsequential; even these statuses, and the roles associated with them, influence this player’s performance on the cricket field. We know that when Sachin was playing cricket in England, he received the news of his father’s death and had to rush back to India to attend the funeral and perform the associated rites. This affected his participation in the game. Playing against Pakistan certainly evokes the Indianness in the Indian cricketer, and loyalty towards his country in the Pakistani player. National pride, although not part of the package for the game of cricket, does surreptitiously enter the frame of reference of individual players, and influences their performance in the field.

Hence, a group continues to exist even when its members ‘are not gathered together in the same place, in one another’s physical presence’ (Johnson, 1960: 6).

Membership in different groups gives an individual different statuses. However, any individual is known publicly by one of his statuses, which is called the dominant status. Taking the example of a cricketer, we can say that M. S. Dhoni or Sachin Tendulkar is known primarily as a cricketer representing India. Their other membership statuses remain somewhat subdued. Sonia Gandhi is known as the president of the Congress Party, and Lal Krishna Advani as a BJP leader. The heir-apparent of a Maharana is known as Kunwar Sahib.

The dominant status affects the participation of individuals in other groups; however, these other memberships are regarded as secondary to the principal (or dominant) status.

To Recapitulate

Let us summarize the main points that emerged from the preceding discussion:

- Although a group consists of people, in sociological terms it ‘consists of certain persons in their capacity as members’. For example, a cricketer is not just a player; he belongs to a family, a religious group, a school, a country, a corporate group (for example, Rahul Dravid is an employee of the Bank of Baroda). He participates in many friendships, clubs, or neighbourhood activities. His/her action in all these groups is not part of his/her participation in the cricket team. However, any individual is a well-integrated personality, and his various memberships affect his performance, behaviour, sub-group formation, etc., in different settings.

- A group does not cease to exist when its members leave one another temporarily. The departure of certain members—due to death or migration or resignation—may change the profile of the group, but does not threaten its existence.

- The group, understood as a ‘social system’, is a system of interaction, different from groups understood as an aggregate of persons.

- The same criteria may be applied to distinguish between a group and a sub-group. A sub-group is a subset within the group, but is carved out in terms of certain specific attributes—older versus younger members, male and female members, etc.

- The members of a social system are differentiated according to the social positions they occupy. A social position is a complex of rights and obligations. A person is said to ‘occupy’ a ‘position’ if s/he has a certain cluster of obligations and enjoys a certain cluster of associated rights within a social system. These are known as role (referring to obligations) and status (referring to rights). The role structure of a group is the same as its status structure, because a role from the point of view of one member is actually status from the point of view of others.

- A group should be differentiated from alliances and networks. An alliance may be a group of groups, where constituents maintain their individual identities and yet agree to cooperate with other alliance members on a commonly agreed agenda. A network, on the other hand, constitutes the totality of social relationships of an individual or a group vis-à-vis other individual/s or groups in a given context. There will be several occasions in the course of our understanding of social systems to explicate these distinctions further.

Typology Of Groups

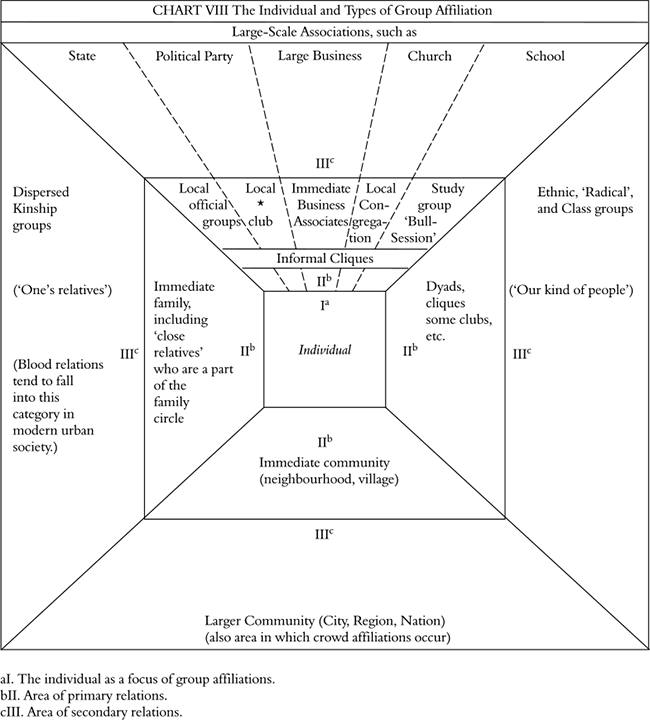

Groups can be classified in terms of size—large or small; the degree of their organization— informal, semi-formal, or formal; the quality of social interaction—intimate or impersonal; the range of group interests—specific or diffused. From the point of view of an individual, a group may be the one to which s/he belongs or does not belong—in-group and out-group. Figure 5.5 shows how an individual in a given society is related to various types of groups.

Primary And Secondary Groups

An essential distinction is made between primary and secondary groups. The concept of primary group was first introduced by Charles Hooton Cooley (1909). He defined it as a ‘small group whose members share personal and enduring relationships’. The family offers an excellent example of a primary group because it is tightly integrated and performs the basic function of socializing the newborn, and thus develops in them an attachment for it.

Figure 5.5 The Individual and Types of Group Affiliation

Source: MacIver and Page, 1955: 223

The concept of primary group was further elaborated by MacIver and Page. They regarded the primary group ‘as the nucleus of all social organization’. They further specified:

The simplest, the first, the most universal of all forms of association is that in which a small number of persons meet ‘face-to-face’ for companionship, mutual aid, the discussion of some question that concerns them all, or the discovery and execution of some common policy. The face-to-face group is the nucleus of all social organization and … is found in some form within the most complex systems—it is the unit cell of the social structure. The primary group in the form of family initiates us into the secrets of society. It is the group through which, as playmates and comrades, we first give creative expression to our social impulses. It is the breeding ground of our mores, the nurse of our loyalties. It is the first and generally remains the chief focus of our social satisfactions. In these respects the face-to-face12 group is primary in our lives (1955: 218–19).

The basic point is that primary groups are spontaneous, and such groups emerge into the most complex organizations.

The nature of the face-to-face group … is revealed most adequately in the detached form where the members come freely together, not as representatives or delegates constitute, defined, and limited to allotted tasks by predetermined arrangements, but spontaneously and apart from executive direction. A group which of its own initiative comes together for debate or study or conference meets this requirement more fully then, say, the class that assembles in a college lecture room; so do the informal cliques of workers in a factory more fully represent the primary group principle than the formal divisions established by the factory’s organizational plan (ibid.: 219).

A primary group is, thus, small in size and consists of people from similar backgrounds, who come together with limited self-interest and in the spirit of cooperative participation. However, it is important to remember that the phrase ‘face-to-face’ should not be taken literally. While a ‘face-to-face’ relationship is essential for a primary group to exist, not all such relationships are of a primary character. A boss and his secretary have a regular ‘face-to-face’ relationship, but they do not constitute a primary group. Of course, a continuous interaction between them might result in an ‘off-office’ relationship, which may then qualify as a primary group. Moreover, even within the office culture small informal groups may be formed on the basis of ‘face-to-face’ relationships. Small group research has focused on groups within groups that are informal in character. Sociometric analysis is deployed to unearth such groups, as they are not formally recognized and are not ordinarily known. It is common knowledge that when students register for a course, they belong to a class as sophomores, where they begin as strangers; however, in due course of time, small groups are formed among them and friendships develop. This may be due to the frequency of contact, common interests (games, or music, or sharing a common room in the hostel, etc.), or a common language. Participation in such groups affects the quality of participation in the formal group called class, or even the college. It was the discovery of such groups (in the 1930s) and their influence on productivity in an industrial firm that virtually gave birth to Industrial Sociology and the Sociology of Management. The famous study of the ‘Bank-Wiring Observation Room’ carried out at the Hawthorne Electric Company became a classic reference in management sciences.13

The above example suggests that primary groups continue to exist even in complex societies, and spring up even in formal organizations. In fact, the larger the group, the greater the chances of primary groups forming, as people come to know only a few members of the larger group at a personal level.

The concept of secondary group appears as a residual category, in the sense that all groups that are not primary are secondary. They tend to be large and impersonal and are organized around specific goals or activities. For any particular individual, participation in a secondary group is generally limited to a short term. A college student joins a particular class—a secondary group—which s/he quits after clearing the examination. The class shall remain but its membership will change radically over a period of time. The number of such groups is much larger compared to one’s primary group. No person can afford to have too many primary groups, but may belong to several secondary groups as interactions in them tend to be limited and goal specific. Members of a primary group have a personal orientation; those in a secondary group are united by goal orientation.

Macionis has clarified the differences between the two types of groups in the following manner as shown in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Primary Groups and Secondary Groups: A Summary

Primary Group |

Secondary Group |

|

|---|---|---|

Quality of Relationships |

Personal orientation |

Goal orientation |

Duration of Relationships |

Usually long term |

Variable: often short term |

Breadth of Relationships |

Broad; usually involving many activities |

Narrow; usually involving few activities |

Subjective Perception of Relationships |

As ends in themselves |

As means to an end |

Examples |

Families, circles off riends |

Co-workers, political organizations |

Source: Macionis, 2006: 165

In-group And Out-group

The distinction between in-group and out-group is also from the point of view of individuals participating in a group. Members of a group regard it as an in-group and view groups in which they do not participate as out-groups. The size of these groups is of course variable, from very small to very large. In this sense, an in-group is a ‘we-group’ and an out-group is a ‘they-group’. Based on the principle of membership, this distinction is helpful in the analysis of group behaviour—expressing solidarity towards the group to which we belong, and categorizing those who belong to an out-group, generally by stereotyping them. ‘In simpler language, we tend to react to in-group members as individuals, to those in the out-group as members of a class or category. We tend to notice the differences between those who are in our in-groups and to notice only the similarities of those in the out-group’ (Bierstedt, 1963: 307).

Sociologists also make distinctions between (i) large and small groups, (ii) formal and informal, (iii) long-lived and short-lived groups, (iv) voluntary and involuntary groups, (v) horizontal groups and vertical or hierarchical groups, (vi) independent and dependent groups, and (vii) open and closed groups. This kind of dyadic classification placed within a single matrix can lead to innumerable boxes, making the typology futile and unusable. Till date, there has been no satisfactory classification that can convert the diffused property spaces into manageable categories.

One concept, namely, reference groups advanced by Robert Merton, has attracted great attention because of its enormous theoretical potential. We shall briefly introduce this concept here.

Reference Group

It is obvious that the number of groups to which an individual belongs is comparatively smaller than the number of those groups of which s/he is not a member. It is only from the point of view of a given actor that groups can be classified into membership or non-membership groups. These serve as reference groups, that is, points of reference for shaping ones attitudes, evaluations, and behaviour (Merton, 1964: 233). That is why reference groups are, in principle, innumerable (ibid.).14 When Merton developed the theory of reference groups in collaboration with Alice S. Rossi, sociologists were focusing their attention only on membership groups while analysing the influence groups have on an individuals personality and behaviour. It was The American Soldier, a work carried out during World War II and published in two volumes (authored by S. A. Stouffer et al., and published in 1949 by Princeton University Press), that provided Merton with the stimulus to develop his theory of reference groups by reanalysing The American Soldier data on Relative Deprivation.

Relative deprivation occurs only when people compare their situation vis-à-vis others. Compared to those who are better placed, a person feels deprived, but compared to those who are lower than him in status or riches, he feels superior, while it is the other party that suffers from relative deprivation. This is the sense in which a distinction is made between absolute poverty and relative poverty.

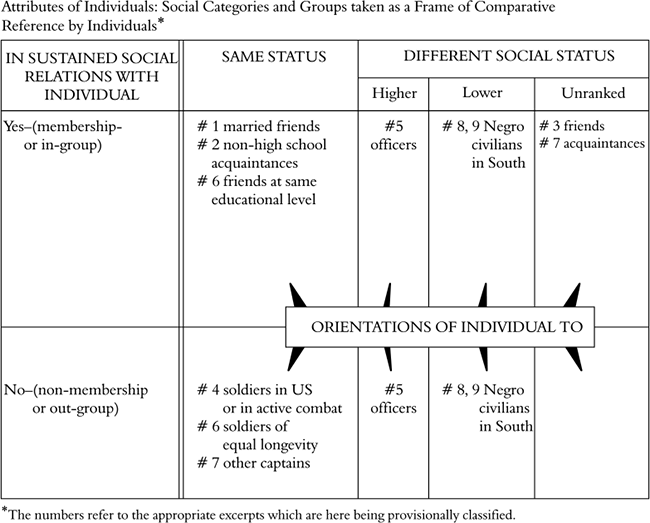

It is this concept that led Merton to investigate the groups with which people compared their own situation. From the first volume of The American Soldier, Merton excerpted nine instances where respondents expressed relative deprivation. Proceeding inductively, Merton found ‘that the frames of reference for the soldiers under observation … were provisionally assumed to be of three kinds’. These were:

- ‘comparison with the situation of others with whom [subjects] were in actual association, in sustained relations’ (people in the same job, acquaintances, etc);

- comparison ‘with those men who are in pertinent respect of the same social status or in the same social category’ (for example, a captain in the army comparing his lot with other captains not necessarily in direct social interaction); and

- comparison ‘with those who are in some pertinent respect of different status or in a different social category’ (for example, a non-combat soldier with combat men).

The presence of sustained social relations between the individual and those taken as a basis for comparison indicates that they are to this degree, in a common membership group or in-group, and their absence, that they are in a non-membership group or out-group. When it comes to comparative status, the implied classification is slightly more complex: the individuals comprising the base of comparison may be of the same status as the subject, or different, and if different, the status may be higher, lower, or unranked (Merton, 1964: 211–12).

These ‘array of reference points’ are shown in Figure 5.5, where only two variables are chosen to build the matrix: the fact of sustained relationship and status of the respondent vis-à-vis his counterparts.

It is generally granted that the groups of which an individual is a member serve as that person’s reference group, as the actions of that person are oriented towards it. However, reference group theory suggests, as is clear from the analysis of the data from The American Soldier, that the person also compares his or her behaviour with persons belonging to other groups, of which s/he is not a member. And it is this territory of numerous non-membership groups that has been explored by the evolving reference group theory.

Any person’s orientation to any other group, which s/he does not belong to, depends on whether that person is interested in becoming a member of that group, and whether s/he is eligible for membership. Depending on these criteria, we may build a matrix.

Summarizing the Mertonian exposition, Johnson states:

For members of a particular group, another group is a reference group if any of the following circumstances prevail:

- Some or all of the members of the first group aspire to membership in the second

group (the reference group) (see Table 5.3).

Table 5.3 Group-defined Status of Non-members

Non-members 'Attitude toward Membership

Eligible for Membership

Ineligible

Aspire to belong

Candidate for membership

Marginal man

Indifferent to Affiliation

Potential member

Detached non-member

Motivated not to belong

Autonomous non-member

Antagonistic non-member (out-group)

Source: Merton, 1964: 290

Figure 5.6 Attributes of Individuals, Social Categories and Groups

- The members of the first group strive to be like the members of the reference group in some respect, or to make their group like the reference group in some respect.

- The members of the first group derive some satisfaction from being un-like the members of the reference group in some respect, and strive to maintain the difference between the groups or between themselves and the members of the reference group.

- Without necessarily striving to be like or unlike the reference group or its members, the members of the first group appraise their own group or themselves using the reference group or its members as a standard for comparison (Johnson, 1960: 39–40).

Thus, reference group behaviour is reflected in (i) striving for admission, (ii) emulation, (iii) conferral of superiority, and (iv) simple comparison. It may also be a combination of different types. In terms of the eligibility criteria, those motivated to join can either be ‘candidates for membership’ if they are eligible, or remain marginal if they do not satisfy the eligibility criteria. Indifferent yet eligible persons are regarded as ‘potential’ members in the event that they are motivated to join; but those who are both indifferent and ineligible remain detached from the non-membership group. The eligible but not motivated remain ‘autonomous non-members’, while those who are ineligible and critical of the reference group will be antagonistic. For persons of both categories, the group in question is a negative reference group.

Let us take some examples of each.

Students passing the CBSE examination aspire to gain admission in reputed institutions of higher learning. However, admissions there are governed by the twin criteria of pass percentage and entrance test scores. Those fulfilling both conditions are candidates for admission; others who have scored less than the prescribed marks in both examinations remain marginal, hoping to gain admission if the scores are lowered.

There might be some students who qualify but are not interested in joining a particular course, say medicine (as they want to join an IT course). They can be regarded as ‘potential’ candidates who could be persuaded to join; others, who are neither eligible nor interested in medicine, are examples of ‘detached non-members’.

There might also be those who are amply eligible but are not at all interested, say, in becoming a doctor; they would fall under the category of autonomous non-members, in the sense that no purpose would be served in trying to motivate them.

Those criticizing the medical profession without fulfilling the eligibility criteria are classed as antagonistic.

A good example of reference group behaviour is found in the Indian caste system. Hinduism, being a very old religion, has continuously accommodated several groups within its fold and enlarged its membership. New groups entering the Hindu fold found their places in the Hindu caste hierarchy, based on the four-fold varna system. New entrants followed the customs and practices that suited them, and pursued their traditional occupations even after the merger. Although there is no centralized authority to grant newcomers any particular status, it was determined in the context of specific localities by the participating groups, who developed norms for commensality and social and ritual distance. Due to this fluidity, groups chose to either remain where they were, or to move up or down the ladder of caste hierarchy.

Castes located on the lower rungs of the hierarchy treated upper castes as their reference groups, and tried to emulate their behaviour and lifestyle in the hope of moving up the hierarchical ladder. They did so by renaming themselves and eschewing some habits such as drinking alcohol and eating meat. The adoption of vegetarianism and teetotalism, and the following of other Brahmanical practices became a feature at the beginning of the twentieth century. Depending on their main vocation, they claimed their place in the kshatriya (warrior) or the brahmin or vaishya varna. Sometimes people of the same stock located themselves differently in different regions.

This process was facilitated by the new institution of the decennial censuses, introduced by the British. The census also recorded the castes of respondents. Once listed, the caste title became official. Since census enumerators had no way of verifying the claim, they recorded the caste as reported. That system of enumeration has several flaws, which become obvious when the data are judged in terms of the sociological definition of caste. Here it is sufficient to say that lower castes treated upper castes as their positive reference groups, and many of them succeeded in getting their varna category changed while retaining their caste. This pattern of upward mobility was aptly described by M. N. Srinivas, a pioneering Indian sociologist, as Sanskritization. This was the first major concept that Indian sociology offered, and it provides a good example of reference group behaviour.

Although Srinivas did not allude to reference group theory, his discussion of the process of Sanskritization suits this theory perfectly. Implicit in his statement is the point that lower castes treat higher castes as a positive reference group, which they emulate because of the prestige associated with it. Through such behaviour, they do not seek to enter a higher caste, but move from one varna category to another as a group. Thus it is emulation and not striving for admission; comparing their lifestyles with those of the upper castes, the lower group may decide to give up some practices (such as non-vegetarianism and alcohol) and adopt certain upper-caste practices to change their profile. On occasion, the upper castes might discourage such efforts to maintain their superiority and political and economic dominance. But field studies suggest that this process was widespread. Such an upward mobility was always possible, particularly in the middle rungs of the hierarchy. A lower caste succeeded, in a generation or two, in climbing up by adopting certain practices and by sanskritizing its ritual and pantheon. Tribal groups that were not part of Hinduism came to be treated as castes when they adopted Hindu practices and began interacting with other local castes. Since Hinduism is polytheistic, these groups continued to worship their deities with some added rituals. Along with these new entrants, Hinduism continued to absorb local cultural beliefs. This is the reason why the local caste system represents a unique hierarchy of castes, jatis. In two different cultural areas, the same caste (jati) may have two different positions in the hierarchy, brought about by differences in their Sanskritization.

Srinivas is of the view that the second varna, namely, kshatriya, has been the most open. It has accommodated all kinds of groups that had the effective possession of political power. ‘He who became chief or king had to become a kshatriya, whatever his origins.’ A bard provided a genealogy linking the chief with a well-known kshatriya lineage, or even to the sun or the moon (Surya Vanshi or Chandra Vanshi). The lifestyle of the newly coronated king had to correspond with the Kshatriya way of life, duly supported by brahmin priests. Brahmins have always been predisposed to revere power, and they helped in legitimizing the chief’s authority. Various sects as well as pilgrim centres have acted as agents of Sanskritization.

Srinivas has mentioned two forms of caste mobility. One, ‘in which a jati adopted, over a generation or two, the name and other attributes of a regionally prestigious dominant caste which was not highly Sanskritized’; and two, ‘in which a Jati called itself a Brahman or kshatriya or vaisya (usually with a prefix), and this was accompanied by appropriate changes in its dietary, style of life, and ritual’.

We cannot go into the debate that this concept (which also prompted other sociologists to introduce similar concepts such as Kulinization or Kshatriyaization) generated here. The new concepts introduced also hint at reference group behaviour. It might be useful here to suggest a reverse process to sanskritization that has gained currency in recent times. The policy of reservation and the special privileges now being granted by the Government of India to the so-called lower strata of society somehow halted the process of Sanskritization, and even encouraged the previous parvenu groups to return to their original status in order to take advantage of the benefits. Rather than shedding the old derogatory names, the groups now take pride in calling themselves Dalit (oppressed—a term British officers used in the censuses). Thus, groups that served as positive reference groups and encouraged upward mobility have now become negative reference groups, giving rise to antagonistic feelings.

A recent instance of this process is provided by the Gujar movement in Rajasthan. This group, which is, in fact, a cluster of groups carrying the same name, but separated from each other through endogamous boundaries and even religion, succeeded in raising its status during the colonial period. Most of its men who wanted to join the government opted for jobs in the army. Yet another group, the Meenas, who were initially identified with the Bhil tribals in southern Rajasthan, followed the same trajectory. Their namesakes in eastern Rajasthan were, however, given a prefix, jagirdar—landlords. But when the Constitution of free India was promulgated with a provision for special privileges for Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes (STs and SCs), all Meenas were included in the ST category. This provoked the Gujars who, feeling relatively deprived in comparison, demanded that they be included in the ST category. Thus, the castes covered under the umbrella term Gujar, which had somehow succeeded in moving up the caste hierarchy and so were not listed as tribals in the British Censuses, demanded a move back to the ST category. This was a clear case of reverse Sanskritization.

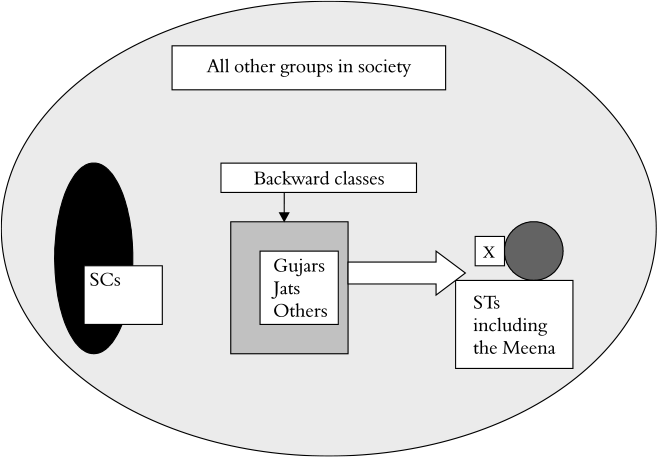

We need not dwell here on the merits of the case, but can just hint at reference group behaviour. This is illustrated in Figure 5.7.

The broader circle represents the total population of Rajasthan, the black circle consists of castes listed in the scheduled caste category, the dark grey circle represents the tribal population of the state (around 12 per cent), and the light gray rectangle represents the castes recognized as backward castes. These three distinct groups enjoy the privileges that came with being backward, which included reserved seats in government jobs, educational facilities, etc. The Gujars regard the ST category as a positive reference group and are seeking entry by claiming a tribal status, thereby opting to eschew the status of a caste hitherto enjoyed by them. They are highlighting features in their social organization that ‘appear to them’ to be tribal; however, the tribals are resisting their admission. Amongst tribals, the Meena are the most opposed, and the Gujars are now comparing their lifestyle with that of the Meena to suggest an identical social history and status. The Meena, though, have enjoyed far greater benefits by being included in the ST category, and they feel ‘relatively deprived’. They have yet another demand: ‘if we do not qualify, then Meena does not either; therefore, if we are denied entry, then oust the Meena as well’. This is a perfect example of reference group orientation.

Figure 5.7 Reference Group Orientation of Backward Classes in India