CHAPTER 4

Contours of Culture

Living in groups is a characteristic that humans share with other animals, particularly primates. Some animals lower than Homo Sapiens (meaning intelligent being) are also found to be gregarious, having some sort of group life. Even ants are found to have social organization!

What distinguishes Man from other biological beings, however, is his capacity to build culture. Society among humans is unique in that its identity is defined by its culture. The human population of the world is divided into several societies, but each society is distinct from the others in terms of its culture. It is this additional feature that distinguishes a human society from societies of lower-level animals.

Most of the behaviour of infra-human beings is instinctive—it is ingrained in their genes, so to speak; it is the same irrespective of their surroundings. Chimpanzees, gorillas, or orangutans1—the highly developed apes regarded as distant cousins of Man, also called primates—are also found to be ‘social’ in the sense that they interact with their small group, mostly comprising of kin. They have some capacity to ‘learn’ and even ‘invent’—of course, mainly through juxtaposition. But in their case, too, most of their behaviour is biologically conditioned. Chimpanzees anywhere, for example, will have the same pattern of social organization. Not so with Man.

Man—the Culture-bearing And Culture-building Animal

It is only Man whose behaviour is largely learnt and, therefore, differs from society to society. He has an enormous capacity to learn, to forget, and to relearn. A child of Indian parentage brought up, say, in an African tribal setting, will acquire the culture of the place of his habitation; similarly, a Nuer or a Bushman Hottentot child nurtured in India will have almost nothing in common save racial features with his or her parental society. It is the culture of India, or of the Nuer or Bushman Hottentots, that defines the society of those geographical locations. Even when the group as a whole, or part of it, changes its locale, it carries with it its own culture, expressed in terms of both visible and invisible traits: the dressing pattern, the food habits, the language, the religion and rituals, values and beliefs, etc.

More than that, a human group has a tremendous capacity to adapt to different types of environments and to continually enrich culture through the acts and innovations of its members. A living culture is a constantly changing phenomenon.

Man has been a great inventor. He is not merely a recipient of what nature offers; he transforms the natural gifts to his advantage. In doing so, he also damages the environment. It is Man who is held responsible for the current crisis related to climate change.

We shall now attempt to draw the contours of culture in this chapter.

Let us begin by elaborating the point regarding the biological gifts of Man that made him a culture-building and culture-bearing animal.

Consider the large number of languages that humans have invented: we are told that some 10,000 years ago, when the world was populated by around only five to 10 million people—just about half the population of Delhi/NCR (National Capital Region), there were as many as 15,000 spoken languages,2 one for each indigenous community. It is said that language changes after a radius of 5 km.

The Atlas of the World’s Languages lists 6,796 languages spoken today. With the same vocal chord, Man is capable of speaking any of these languages. In India, most educated people speak two to three languages. True, the number of languages is shrinking because some of them are dying, or are in disuse; their number, though, is still larger than the number of nation-states. In India alone, besides the languages recognized by the Constitution of India, there are several dialects that are still spoken; the 1991 Census of India put the number of languages/dialects spoken in India at 1,576.

Language is but one aspect of culture. The variety of cultural traits and complexes is indeed immense. It is this attribute of Man as a culture-building animal—Man the Toolmaker—that is distinctive, and is the most influential in the life of any individual.

A more concrete example is that of clothes. The types of headgear used by men and women in different cultures, and even in the same culture by people of different statuses, are varied.

Social behaviour in a group is limited, on the one hand, by the biological constraints of individuals, and on the other, by cultural conditioning. At birth a human child is a biological brute; he is transformed into a social animal through socialization and enculturation.3

In social sciences, the nature versus nurture controversy is now almost gone. One cannot say that whatever Man has by way of culture is determined by his natural environment or by his biological make-up; nor can one say that culture has no connections with the biosphere in which man operates. The point is that even within the same environment and the same biological make-up, man has developed different cultural patterns. Take the case of headgear. In the same environment, some people wear a turban while others do not, and even those who wear a turban do not tie it in the same fashion. A Sikh turban is different from a Mewari pagdi and a Rajasthani safa.

Traditional attire of a Rajasthan village woman: covering the head with sari

(Source: © Anthropological Survey of India)

Even people of the same ethnic group or caste, living in the same region may wear the turban differently. One finds a variety of turban styles in Rajasthan; the same is true of different sects of Sikhism—the Namdharis and the Akalis, for example, wear their turbans in specific colours (white and blue respectively) and tie them differently. Similarly, in Mewar, the king used to wear a sanga—shahi pagdi on festive occasions, which was different from that worn on ordinary days. Even there, one finds variations in the manner in which it is tied by different people, as well as in the colours worn. A white pagdi is worn by a person who has lost his father; a colourful turban, with gold decorations, suggests that the person wearing it is a bridegroom, or one connected to the royal family.

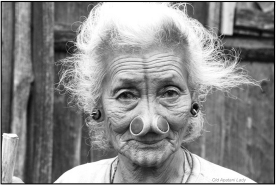

Apatani woman

Just as people wear different attires in the same environment, they also wear the same attire in different environments. Despite the heat, a regular suit is worn on formal occasions when a simple kurta and pyjama4 would be more comfortable. Thus, it is the prevailing cultural norms that dictate behaviour.

Biological Gifts To Man

Culture is, thus, exclusively the creation of man, and is not spurred by instincts. However, it must be admitted that there are some biological features in man that have facilitated the creation of cultures. Students of man have listed five biological gifts that have made man a creator and transmitter of culture.

The first of these gifts is emancipation of hands from locomotion. Animals, including primates that are closer kin of man, use their four limbs—we call them legs and hands—for locomotion. Apes alternate between straight walking and walking on all fours. Man alone is able to walk on his two legs and cover long distances.

This emancipation has endowed him with the second gift, namely, erect posture. Since legs alone are needed for locomotion, man is able to stand erect and gain a height. His hands are freed to perform some of the tasks that were earlier done by the long snout, particularly for exploring the surroundings for food and conveying it to the mouth. Since the hands were freed from locomotion, they developed differently than the feet among the humans. The fingers became opposable to the thumb, and thus developed prehensility—the ability to pluck a fruit, hold an item, and even fashion a tool, or to scribble.

Mewari pagdi (turban)

This development is associated with the change in the function of the eye. With a protruding snout, the two eyes were distanced by an intervening broad nose—so useful in lower animals to assist in smelling the food because of highly developed olfactory senses. As the function of food surveillance was taken away by the hands, and as the erect posture made the eyes far removed from the ground, the snout in man shrunk. This made the human nose much smaller (thus,less smell sensitive) and the gap between the two eyes was bridged to facilitate a stereoscopic vision.

Rather than the two eyes viewing things along the snout, they could see the same item together, thus moving from a myopic vision to a presbyopic vision or farsightedness.5

The shrinking of the area covered by the nose and snout provided space spared for the enlargement of the head that encases the brain. The bigger size of the brain facilitates ‘reasoning’ and ‘memorizing’. Thus, the fourth gift to Man is his reasoning brain.

Sikh turban worn by the former Indian Prime Minister

The last and final gift from biology to Man is the faculty of articulated speech. Man’s vocal chords are capable of producing an infinite number of sounds. Of this immense capability, any particular individual is able to utilize only a miniscule to be able to speak a few languages. However, if we take humanity as a whole, this capability made it possible to invent so many languages. That is why a child of Chinese parentage, brought up in a tribal society of Africa, learns to speak that society’s language and may not be able to utter any Chinese. People from South India, born and brought up, say, in Delhi, are thus, fluent in Hindi or Punjabi and in English, but might falter in their so-called mother tongue. Language is learnt; it is not hereditarily transmitted via the genes. Aryan and Dravidian are the names of languages and do not connote the race of their respective speakers. In this sense, it is technically wrong to call Aryan and Dravidian as races.6

Safa worn by the Gujar leader

Alongside these exclusive gifts of biology to man is one debility, or yet another hidden gift. The human child is a hopelessly dependent creature. It takes much longer time for a human infant to stand on its own feet compared to other animals. This necessitates child care and longer company of the adults in the family. Tiger cubs, for example, take only a few days to be on their own, of course, under the tutelage of their mother; children of monkeys and apes take a little longer, but in the case of humans, the period of child care extends to more than five years—by this time, a dog might become a grandfather; and in a few more months/years might even leave the world for ever. In contrast, a child of 12 does not even complete his first entrance examination to enter the college!

This gift of dependency is conducive to group life, and the development of emotional bonds. Common living creates a ground for collective action and for sharing information and for making inventions, the elements of culture.

(Courtesy: © Rachita Atal)

Taken together, these gifts make it possible for man to manage his relations with nature, negotiate his interactions with other members of his group and with outsiders, and deal with the realm of the unknown, the supernatural.

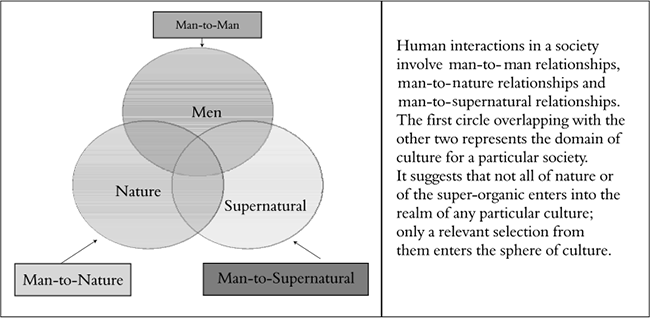

It is the manner of handling these three areas of interaction that differ from one society to another. And it is this that is technically called ‘culture’. Thus, culture is the product of man's interactions with other men, with nature, and with the realm of the unknown—the supernatural (see Figure 4.1). In other words, all three systems of interaction—the society and the polity, the economy, and the religious system—are governed by cultural norms of behaviour that are unique to the society concerned.

Figure 4.1 Human Interactions in Society

As we have said, the ‘seeds of cultural capacity’ are also found in some lower-grade primates, particularly the great apes—chimpanzee, gorilla, and the orang utans. It has been shown, through careful investigation of these human cousins, that

[T]hey possess the capacity to perceive the applicability of the observed phenomena to the attainment of desires: invention. They apply sticks as levers and stones as hammers; they fit sticks together to extend their reach; they use them as vaulting poles to extend their jumping capacities—and as jabbing rods to annoy unwary hens about the ape farm …. Such patterns are not inborn. They are not instinctive; they are proto-cultural, the stuff out of which culture develops (Hoebel, 1958: 71).

However, apes could not create culture because they have a short memory and they lack the skills to communicate their experience (lack of language) to the new members of the family. Transmission of culture from one generation to another is thus possible only among human societies.

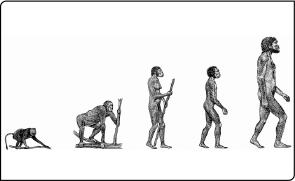

When humans emerged with progressive evolution, they possessed better biological gifts that those mentioned above. With their erect posture and prehensility of their hands, they had a better capacity to fashion tools; stereoscopic vision helped them focus on the finer points of the artefact; the faculty of articulated speech enabled them to convey their experience to others; and the enlarged brain has the capacity to reason and to remember. Not only can man memorize, he also has the capacity to forget. This latter capacity allows him to learn new things: learning, forgetting, and re-learning are essential processes in the growth and spread of knowledge—the cultural capital. No doubt man is intelligent, but living in isolation, he might remain a stupid animal, an idiot; intelligence develops only in the company of other men. Speech is also a general trait; though highly developed in man, it is also found in rudimentary forms in other animals. Similarly, sociability is a trait that is common among many animals. But it is culture that man alone possesses, and that makes a great difference, placing man at the top of the evolutionary ladder.

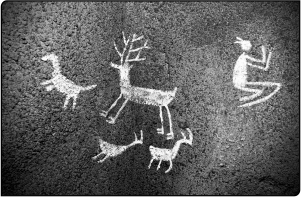

Beginnings Of Culture

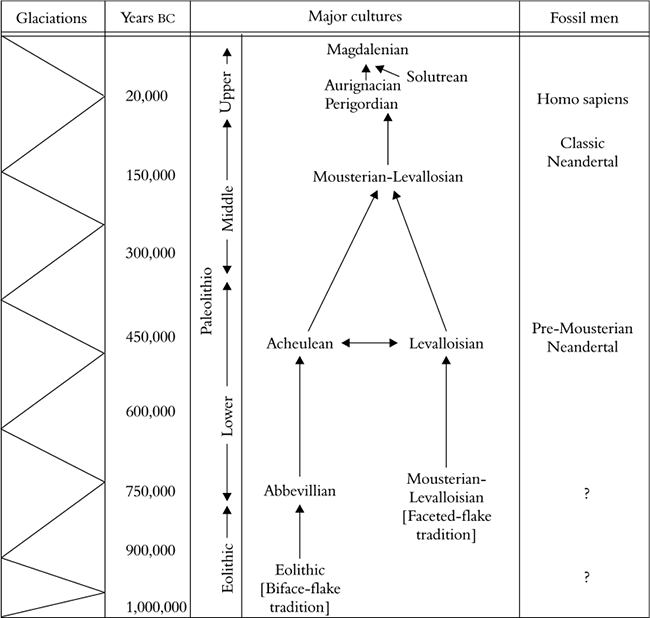

Preliterate societies, with no written history, passed on information from one generation to another through oral communication. Anthropologists working with them had the difficult task of documenting their material and non-material culture. Archaeologists working on long-disappeared cultures unearthed the origins of culture by developing the skills to read or hear stories from fossils, and from the broken evidence of material culture left behind. Their research places the dawn of culture at about one million years BC, naming it the Eolithic Stage—meaning the dawn of the Stone Age. This gave rise to the Palaeolithic Stage or the Old Stone Age with the arrival of the Abbevillian and Mousterian cultures, which constituted the Lower Palaeolithic Stage. The Middle Palaeolithic Stage corresponds with the arrival of the Neanderthal man, who invented the Acheulean-Levalloisian culture. These submerged into the Mousterian-Levalloisian, and ultimately into the Magdalenian in the final stages of the Old Stone Age. The next stage of evolution is marked by the New Stone Age or the Neolithic Age, with further refinements of the stone tools used by man for hunting and food-making. Figure 4.2 shows the chronology of the Palaeolithic Age reconstructed by archaeologists. The evidence of these cultures is mostly Euro-centric, and scattered. However, stages are determined in terms of refinements in tool-making and the geological strata in which they were found.

Palaeolithic man in the middle

(Source: © Dorling Kindersley)

Palaeolithic tools 4,00,000 years

Venus of Willendorf: Palaeolithic age

Wild horse on the walls of Lascaux Caves: Upper Palaeolithic

(Source: © Marcio Jose Bastos Silva.Shutterstock)

Figure 4.2 The Dawn of Culture: The Palaeolithic Age

Source: Hoebel, 1958: 79

Needless to say, these are the cultural developments associated with the origin of man, and are thus not society-specific developments which occurred later with the accumulation of knowledge and formation of larger groups and dispersion of man in different ecological zones. What we refer to here are civilizational developments.

As evolution progressed and as the stock of knowledge increased with experience in handling tools, further refinements occurred in tool-making. From stone tools made from the core or flints, our ancestors started making finer tools such as harpoons and staghorns with eye, and even painted pebbles. The Neolithic stage saw man becoming an architect. He started building houses and settlements for relatively permanent stay. Vessels were built of ceramics for storage and even pottery was invented. At the burial grounds, they built dolmens7 and stonehenges, and menhirs. These are the visible products of early Man’s actions. Archaeological discoveries of these sites help us learn about some aspects of the culture our ancestors lived. The stones and the tools carry the untold story of mankind’s development.

However, all this discussion about our past and about the origin of culture is at a much higher level—it concerns humanity as a whole. It tells us how humans are different from other animals. It narrates the stages of development and evolutionists have debated their unilinearity or multilinearity. Scholars have also tried to explain the simultaneous occurrence of similar artefacts in terms of either direct contact or stimulus diffusion.

Living Cultures Of Man: Evolutionary Ladder

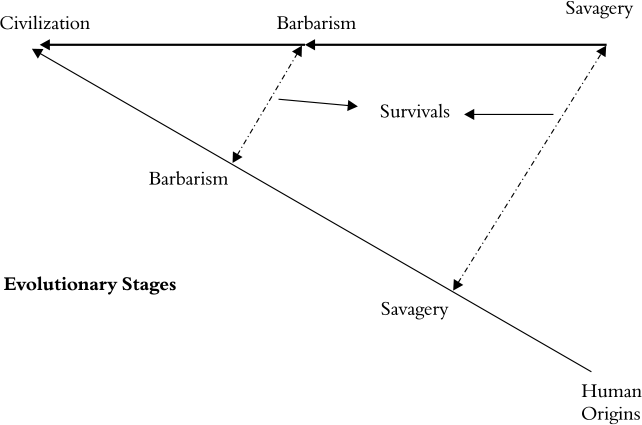

A new line of research that took social and cultural anthropologists to our primitive contemporaries8 gave prime focus to living cultures. Those following the evolutionary approach regarded these primitive communities/tribes living in isolated existence as the contemporary representatives of the culture that we ‘moderns’ might have lived. Their approach can be illustrated thus (see Figure 4.3):

Figure 4.3 Evolution of Contemporary Cultures

They argue that civilization has moved from the stage of savagery to barbarism to civilization. But there are some societies that are still barbaric, or savage. In both time or space, the movement is from savagery to barbaric to civilization. Evolutionists consider these stages as given, and every society has to move from one stage to another. We shall elaborate this line of thinking when we discuss social and cultural change. Suffice it to say that evolutionists amongst social anthropologists approached the present-day tribal societies with that specific theoretical orientation.

Other cultural anthropologists were amazed by the enormous diversity in cultural patterns, even those associated with the fulfilment of basic human needs. It is this concern that led them to develop a theory of culture as ‘superorganic’, and promote cultural relativism as a scientific ethic.

It was British sociologist Herbert Spencer who described culture as ‘Superorganic’, to differentiate between the natural environment of inorganic and organic materials. Originally, the earth possessed only inorganic matter. It took several million years for organic matter to occur and evolve into homo sapiens. And it took several thousand years for Man to develop a society-specific superorganic to build cultures and much longer still to fashion civilizations. Social sciences now use the word culture for this superorganic pool, which is derived from the German word kultur.

The concept of cultural relativism:

[H]olds that any cultural phenomenon must be understood and evaluated in terms of the culture of which it forms part. … We, the students of culture, live in our culture, are attached to its values, and have a natural human inclination to become ethnocentric over it, with the result that, if unchecked, we would perceive, describe, and evaluate other cultures by the forms, standards, and values of our own, thus preventing fruitful comparison and classification (Kroeber, 1965: 1033).

Definition Of Culture

The concept of culture is one of the significant contributions of the discipline of anthropology to the understanding of society in an interdisciplinary perspective, meticulously developed by Talcott Parsons and his co-authors. Since sociology is the study of the social sphere, the concept of culture is central to its concerns.

Studying far-off, pre-literate societies, anthropologists were alerted to the great diversity in human behaviour.

To take a simple example, when two known acquaintances meet, how do they greet each other? In France, they greet by kissing the cheeks of each other, in India and in Thailand they greet with folded hands, saying ‘namaste’ or ‘sawadi khap’ (both linked to the Indian civilization), in other parts of Europe and in America, the two parties shake hands. ‘An Andaman Islander from the Bay of Bengal ... weeps copiously when he greets a good friend whom he has not seen for a long time’—something similar happens when an Indian family from Mewar, Rajasthan, receives a near kin returning home after a long period of absence. In India, farewell is generally ‘tearful’; when the bride is sent off after the wedding, all relatives of the bride weep—a complete contrast to the ceremonies preceding the send-off, which are colourful and joyous.

All actions that become rooted in one’s culture and are followed almost instinctively might have originated randomly, but each society makes an effort to reduce such behaviour to ordered patterns. Such standardization of behaviour is technically called ‘institutionalization’ or norm-setting, which is then followed by members of a society as a matter of course, as learnt and internalized behaviour. These norms become part of culture.

This conception of culture is different from the everyday use of the word. In common parlance, we use the term for sophistication; for the way of life of the ‘high society’; for arts, music, and literature that require special skills to perform or create, and are generally considered beyond the reach of the ordinary. That is how the government has a separate ministry for culture,9 under which come the academies of fine arts and literature. But this is a narrow and elitist usage of the word culture. Culture is not a museum of tradition or of artefacts.

The social science usage of the term, adopted from anthropology, is different. It is used for all forms of invented behaviour:

[T]hat are not biologically predetermined by any hereditary set of the organism. Though the biological imperatives of hunger, sex, and bare-bones survival are limiting factors which man may never totally ignore, he is free to experiment with many different ways of meeting these needs (Hoebel, 1958: 7).

Culture, then, is the sum total of integrated learned behaviour patterns which are characteristic of the members of a society and which are therefore not the result of biological inheritance. Edward Tylor defined culture in his 1871 publication, a definition that is still valid, although there are numerous definitions of the concept.10 According to Tylor, culture is ‘that complex whole which included knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and other capabilities acquired by man as a member of society’. Thus, in a technical sense, the concept of culture is much broader, not limited to the knowledge pool of a cultivated minority—the elite—and does not mean only the ‘good’ things. The skill of cheating in a game of cards, called ‘chaukdi’, is as much cultural—as it is knowledge learnt by people who play the game—as the art of singing a classical song. Culture, in the sociological sense, does not signify personal refinement. Thus, the culture of a society is ‘comprehensive’, in the sense that it relates to all aspects of social life of a given society, and thus makes the group ‘self-sufficient’. Tylor’s definition also implies that it is ‘cumulative’ in the sense that all the patterns invented by a group at any particular point in time become part of the collective memory of the group and are transmitted from one generation to another. In the process, some of these receive primacy, others may become dormant, and the people living that culture might add some more elements to it either through invention or discovery, or through the emulation of an outside reference group. This is called the process of diffusion—elements of one culture diffusing into another through culture contact. Thus, while every culture is unique in the sense that all the cultural patterns are neatly integrated into it—making it more than the sum of its traits—each culture consists of elements that are indigenous to it and those that have been borrowed from the outside, but integrated into it. In the process, these traits may change their form, their usage, and even their meaning. A watch, for instance, might not only serve as a time keeper or reminder, but as a part of the jewellery.

In 1937, Ralph Linton published an article titled One Hundred Per Cent American. The purpose of the article was to demonstrate the phenomenon of diffusion through which cultures add to their material repertory, and thereby change and develop. The imaginatively crafted article describes an average American’s daily routine from the time he wakes up till he catches the train to go to his place of work. Right from the morning coffee—the brew and the bowl—through the newspaper and cigar to the sleeping bed, most of the items used by Americans have their origins elsewhere. And yet they have become an integral part of the way of life of an American. The 100 per cent American is the one who leads his life on almost 100 per cent borrowed material cultural elements. This is how Linton concludes his essay:11

As he scans the latest editorial pointing out the dire results to our institutions of accepting foreign ideas, he will not fail to thank a Hebrew God in an IndoEuropean language that he is one hundred percent (decimal system invented by the Greeks) American (from Americus Vespucci, Italian geographer).

The point Linton makes is that the arrival of elements from abroad did not erode the identity of American culture. All cultures, be they small or big, enrich their stock through inventions and borrowing, and it is these processes that bring about changes in living cultures.

Attributes Of Culture

Let us now enumerate the key characteristics of culture.

- Culture is universal: By this,it is meant that culture is a distinguishing feature of all human societies, past or present. Animals lower than man may have group, that is, social, life, but it is man alone who has culture irrespective of the size of the society, or the level of its development. There are certain activities of man that are present everywhere, and yet they are not biologically determined. Similarly, culture is found in all sorts of natural environments in which man has created his habitat. George Peter Murdock (1943) surveyed the literature pertaining to several societies of the world and prepared a list of practices found common in them. The list is given in the Box 4.1.

Of several items, the one that Murdock mentions is language. Heredity has given us the ability to speak, that is, to produce a multitude of meaningful sounds. But not all cultures speak the same language. From this enormous capacity, people of a given culture are able to utter only a limited number of sounds; and any particular member of that society masters a selection from this limited number. And all this is learned, not biologically inherited. Even in the same society, speakers of the language continually modify not only the words, but also the syntax and grammar. In the process, several new words are coined and old words go into disuse. The Hindi that is spoken today is very different from the one spoken by the promoters of Khadi Boli. The way Indians speak English is very different from the way the Americans, the British, or the Filipinos speak. In today's parlance, with the arrival of the computer, several new words have been coined that our forefathers, if they were to return to this earth, will find hard to understand—blog, Google, e-mail, SMSing, uploading, and so on. The vocabulary that students have now invented at their school is another case in point. See Appendix 4.2 for examples of student vocabulary.

Box 4.1 Universally Found Social Practices

age grading

games

music

athletic sports

gestures

mythology

bodily adornment

gift giving

numerals

calendar

government

obstetrics

cleanliness training

greetings

penal sanctions

community organization

hair styles

personal names

cooking

hospitality

population policy

cooperative labour

housing

postnatal care

cosmology

hygiene

pregnancy usages

courtship

incest taboos

property rights

dancing

inheritance rules

population of

decorative art

ioking

supernatural beings

divination

kin groups

puberty customs

dream interpretation

kinship

religious ritual

education

nomenclature

residence rules

eschatology

language

sexual restriction

ethics

law

soul concepts

ethnobotany

luck superstitions

status differentiation

etiquette

magic

surgery

faith healing

marriage

fool making

family feasting

meal times

frade

fire making

medicine

visiting

folklore

modesty concerning

weaning

food taboos

natural functions

weather control

funeral rites

mourning

- Culture is unique: Although culture is universal, it is unique to each society. Each culture, as was said earlier, is a product of innovation and diffusion. But each culture screens all elements coming from abroad before granting them entry, and upon their acceptance, these elements are suitably accommodated within the cultural fabric of the host society. The presence of a common trait in both societies need not necessarily mean their common origin, or their common function or meaning.

As an example, take hospitality, which is a common element in culture. How hospitality is offered to a visiting guest differs from society to society. Warriors, coming as invaders to India, had to first confront the locals and even indulge in violent wars. But once settled, a different orientation guided the behaviour of the inhabitants toward them. From conflict to accommodation, and finally assimilation, Indian culture has been enriched through these associations, and transformed into a pan-Indian civilization, facilitating the emergence of several sub-cultures, or regional cultures. We regard a guest as a god: Atithi Devo Bhav. Accordingly, we offer a good welcome to the visitor. But we will not go as far as the Eskimos living in snow-clad environs would, where

[H]ospitality to a lone traveller always includes food and shelter, and in some cases may include a female sleeping partner. Such a custom is followed only with the consent of the parties concerned, namely both husband and the wife. If such hospitality is extended, its rejection is considered an insult to the woman and the host. The man is head of the house and sexual irregularities without his consent are severely punished. Thus there are rules of behaviour in sex matters, and in no sense is there promiscuity (Ogburn and Nimkoff, 1958: 59).

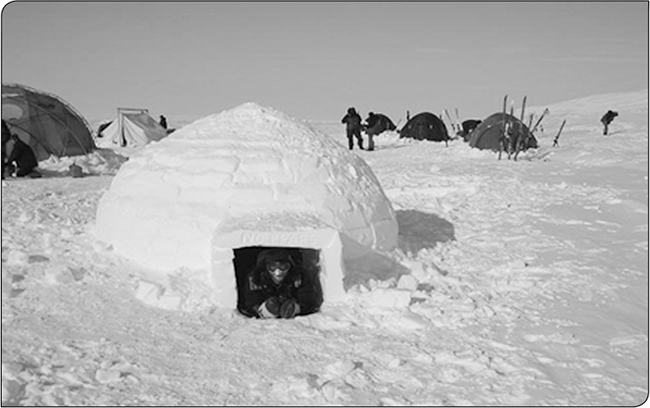

The Eskimos living in Greenland provide a good contrast to life lived on the plains. Living in snow-clad areas, Eskimos have developed architecture to survive in such a cold climate. Their Igloos are dome-shaped and made of snow, and yet are very warm.

They have also developed techniques of hunting in the snow, of transportation using a sledge, and the use of bone and stone in fashioning weapons and other tools. But they also have their own religion and social structure.

An elderly Eskimo, unable to hunt or be of use, often goes way to die alone, or voluntarily asks to be left behind when the family moves on, particularly if the food supply is short and one more person to feed is likely to be a danger to the group. Or, failing voluntary action, the group may decide to leave the old one behind to die alone (ibid.: 59).

Igloo: The house of an Eskimo

Both aspects of social behaviour among the Eskimo—hospitality extended to the guests and the attitude towards the elderly and towards death—differ markedly from many other cultures, where different norms of hospitality and different constructions of eschatology apply. However, cool scientific objectivity demands that they not be viewed from our cultural perspective and be discarded as ‘bad’ or undesirable practices. This is what we mean by cultural relativism. Each culture, being unique, has its own standards of judging an act as bad or good or desirable.

- Culture is carried and made manifest by a group/society: As was said earlier, culture is the product of a group; that group can be society as a whole, or a group within society. When it is of the latter type, it may be called a sub-culture. In India, we often talk of regional cultures, of tribal cultures, and even of Hindu and Muslim cultures. But this should not be confused with ‘society’. A society is ‘people’, a culture is the ‘way of life’ of that people. To quote Herskovits: ‘A culture is the way of life of a people, while a society is the organized aggregate of individuals who follow a given way of life. A society is composed of people; the way they behave is their culture.’ This is an important difference. Individuals constituting a group or a society may die or migrate; the migrants may carry some elements of a culture that gives them an identity, but the culture remains and moulds the behaviour of people who replace the ones who leave and this replacement is both through birth and immigration. Those who immigrate also bring some elements of their parent culture, and thus enrich the culture of the society of their adoption.

- A living culture is not static, it is constantly changing: It is true that culture is socially inherited. A child is born into the culture of its parents and right from its birth, is inducted into it. But those who live that culture also enrich it through innovation and borrowing from other cultures in a variety of ways. For example, those trained in cooking add to the cuisine by experimenting with different combinations of spices or vegetables, and thus add to the cuisine and to culinary art. Painters and artists similarly develop new art forms. As speakers of a language, many changes are introduced either in the manner of speaking, pronunciation, abridgement of words or acronyms, use of words drawn from foreign language—Hindi today contains so many words from Arabic, Persian, and English, and now from the vocabulary associated with IT products—computers, mobile phones, and other gadgets. The composite culture of twenty-first century India is indeed very different from eighteenth-century India, and yet it is distinctly Indian. Appendix 4.2 contains words that are new to the student vocabulary, and are practically unknown to students who had passed out from the same university some two decades ago.

- Culture is superorganic: The word superorganic is understood in three different senses:

- Herbert Spencer meant the phenomena that are directly dependent upon the organic and vary with the latter. In other words, it is a process that supervenes over organic evolution.

- Other scholars use the term to indicate that cultural evolution is not limited by man’s organic structure. They refer to Man’s unique psychological capabilities.

- Alfred Kroeber—the leading proponent of the concept of culture—takes it beyond the psychological frontier. He said that culture is not only superorganic, but also superpsychic. He argued that mentality relates to the individual, whereas culture is non-individual. ‘Civilization is not mental action itself, it is carried by men without being in them.’

It must be said that for long, there has been debate concerning the role of biological and geographic factors, some highlighting their key significance and others discarding such claims. However, both were extremist positions, and both should be recognized as integral elements in the making of a culture. It is true that they play a limiting role and not a determining one. But culture influences them too. The kind of food we eat affects our anatomy and physiology. Many diseases now occurring in present-day society are man-made, and are likely to increase in the near future, changing the profile of the burden of disease of a given society. If the fear of tobacco causing cancer has reduced the incidence of public smoking, long durations of work in front of computers and at odd hours in the call centres is adversely affecting life and marriages of such persons. HIV, swine flu, impotency and old age diseases (geriatrics) are gifts of the globalizing world.

- Culture is integrated: A culture is more than the sum total of its traits and complexes. The various elements of culture interface with each other directly or vicariously and form an integral part of it. The presence of the same element—particularly a material cultural element—in two different cultures does not mean that it has identical functions or meanings. Foreign tourists who buy tribal or ethnic products and place them in their drawing rooms do not carry the culture of the place from which these originate. For them, these products serve the function of museumization. In the originating culture, they might be part of the religious practice or of daily use in the kitchen; in the culture of its exporter, they may become show pieces in drawing rooms. The purchase of these items is motivated by factors such as their exotic character, primitiveness, or as an example of folk art. It may also be guided by the humanitarian consideration of helping ‘poor craftsmen’. However, bringing them into the market may seriously affect the cultural fabric of the community, might even alienate some, or create a rich– poor divide that might not be so prominent in a tribal social structure.

This consequence alerts us to the fact that cultures change as a result of interactions, both between members of a society and with non-members—with visitors, or when natives visit other societies.

Integration also suggests that different aspects of culture are so intertwined that any change brought about in any part of culture has wide-ranging ramifications that affect the other parts in different ways and to different degrees. The arrival of loudspeakers and microphones—products of modern technology invented abroad—affected not only the manner of organizing large public gatherings for political purposes in India, but also the working of our temples and mosques. In Indonesia, for example, morning Azans are broadcast on loudspeakers installed throughout the city. Big religious congregations are held in India where the voice of the religious preacher can be heard through loudspeakers, while they can be seen on the large screens posted in different parts of huge assembly halls; they are also telecast live, reaching large audiences even beyond the country. The popularity of religious leaders like Ramdev or Murari Bapu has been greatly facilitated by the arrival of the TV, and their appearances have rekindled interest in religious thought and practices like yoga even among those who had earlier taken pride in declaring themselves ‘secular’.

Culture is thus to be seen as an integrated whole. All elements, even the minor ones, play an integrative role.

Children’s games and nursery rhymes undoubtedly reinforce the norms and values of a culture, often ending with rather explicit ‘lessons’ about appropriate and inappropriate behaviour. Similarly, ceremonies such as weddings, funerals, and confirmations prepare participants for new social roles and reduce the shock of change which might threaten social continuity. Sociologists agree that no culture can be logically divided into separate parts for analysis and be truly understood. Every part of the culture is intertwined with others and contributes to the culture as a whole (Schaffer and Lamm, 1998: 80).

Components Of Culture

A culture consists of elements or traits, complexes, norms, and institutions.

The smallest unit of culture is a trait or an element. It is a pattern of behaviour or a material product of such behaviour that is easily identifiable. Each item of the material culture, be it in the kitchen or the drawing room or the marketplace, is an element or trait of culture, not in terms of its physical attributes, but in terms of the behaviour pattern associated with it. A rolling pin—belan—is used in India and in several western bakeries. But the belan in Indian households has quite a different status than it does in the bakery. Indians associate it with the ‘wife’ because she is also the ‘chef’ in the household, and is used in many jokes related to husband– wife relationships where this rolling pin becomes the symbol of alleged husband bashing!

A network of closely connected traits/elements/patterns is called a ‘cultural complex’. A dance form is a good example. In this complex are involved many cultural elements such as dress, ornaments, music, musicians, musical instruments, stage, lighting, audience, and so on. It is in the totality of all this in a particular combination that dance becomes a cultural complex.

A higher level includes various norms, patterns, and complexes, and is called an ‘institution’. A marriage is an institution in this sense. The institution of marriage varies from culture to culture in terms of the structure of cultural traits and complexes, and the norms and values associated with them. While marriage denotes a union of the male and the female for mating and parenting, the manner in which it is conducted differs from society to society. It is society’s norms that govern the choice of a mate—who can, and who cannot, marry; the timing of the ceremony, and everything that is done to effect a marriage.

The organization of components in a culture can be understood in terms of a hierarchy. Norms that are to be followed by all are called universals. These constitute the core of culture.

Options constitute alternatives and are placed just outside the core. Thus, an Indian can either formally wear a suit with a tie, or a bandgala, or a shervani, or go in a dhoti-kurta—all these options are open. If, however, one of these becomes compulsory, it would enter the core and become a universal. For a long time, wearing a sari was the norm for an Indian woman—a universal—but now it has become an alternative as women all over the country make choices between a sari, a salwar-suit, or jeans and a shirt. From being a universal, sari has become one of the alternatives.

Then there are elements and complexes that are specific to certain statuses or sub-systems. These are called specialities. The manner in which newly married women dress, with a profusion of jewellery, vermilion in their hair partings, bright bangles, etc., can be called an attribute of a bride—a speciality. These specialities are known to other members of the group, but they would not use them as they are not part of their pattern of behaviour. It is in this sense that we can identify the universal traits of all Indians irrespective of the region to which they belong, because they are the integrating elements of Indian society and culture. It is the regional specificities that distinguish them, for example, the use of regional languages, regional cuisine, regional festivals, etc. It must also be said that efforts at fostering integration have universalized many regional traits. The common Indian cuisine of India has in its inventory Tandoori dishes from Punjab, the Idli-Dausa from the South, the Dhokla from Gujarat, and the Sandesh-Rasgolla from Bengal.

The cohesive strength of a society is in part a product of the relative proportion of universals to specialties. In any analysis of society and culture, it is absolutely essential, in the interest of clarity and accuracy, never to generalize from the norms of a subgroup to make statements about the society as a whole, unless it has been observed that the norms of the subgroup are also characteristic of the whole (Hoebel, 1958: 168).

At this point, it will also be appropriate to make a distinction between ideal and real culture. Before the arrival of sociology and anthropology in India, most descriptions of Indian society were made by the so-called Indologists. These scholars did not make any distinction between Indian society and Hindu society. India was treated as a ‘caste’ society, and the system of caste was explained in terms of what an ancient sage, Manu, had written in the Manusmriti. Foreigners learning about Indian society through such writings contrasted their society as ‘class society’, and decried the caste system as bad and undesirable. Without going into the merits or demerits of the caste system at this juncture, what can be said is that old scriptures, particularly the Smritis, were written as prescriptive modules in the language of ‘should’ and ‘ought’, or in a proscriptive mode as don’ts. As such, these commentaries and treatises are not ‘descriptions’ of the actually existing situation of olden times. They are the collected inventories of ‘desirables’; they read like a blueprint, as guidelines. In other words, they can at best be taken as depictions of an ideal culture. The extent to which the ideal was realized by Indian society at any particular point in time is a matter of speculation in the absence of good descriptive accounts of the life led by our ancestors. Some later-day scholars compared present-day societies against the Manu model to identify the differences. However, many of them made the mistake of taking the ideal as the real of the past, and regarding the present as a departure from the past, denoting a change that has occurred in the interregnum, and not as a difference between the ideal and the real.

Historians feel that when proscriptions are offered, there might be a better chance of rightly assuming that the proscribed practice had prevailed once upon a time. ‘Do not eat meat’ or ‘practice vegetarianism’ can be an indication that people of that time were meat-eaters, and therefore, they were sermonized into giving up these practices. But we can only guess at whether positive prescriptions were ever followed. Finally, it must be said that Indian society is not a synonym for Hindu society, and therefore, what might be true of Hindu society would not be applicable to the other religious communities inhabiting India.

The difference between ideal and real culture can also be seen in another way. Fieldworkers have always found a difference between what people think they do, what they say they do, and what they actually do. Statements made by informants about any cultural pattern are generally closer to the ideal and the desirable, and people depart from it in real life. We quote a passage from Bronislaw Malinowski, who worked among the Trobriand Islanders in the Pacific. In his book on Crime and Custom in Savage Society (1926), Malinowski gave an apt illustration of the views on clan incest:

If you were to inquire into the matter among the Trobrianders, you would find that … the natives show horror at the idea of violating the rules of exogamy and that they believe that sores, disease, and even death must follow clan incest. [But] from the point of view of the native libertine, survasova (the breach of exogamy) is indeed a specially interesting and spicy form of erotic experience. Most of my informants would not only admit but actually did boast about having committed this offense or that of adultery (kaylasi); and I have many concrete, well-attested cases on record (Malinowski, 1926: 79).

Indian children are similarly taught to respect elders and treat parents as demi-gods. When Indians are asked about this, they give the same standard reply. However, it is not a secret how often this norm is violated. Daily newspapers carry stories of ill-treatment meted out to senior citizens by their own progeny. They even take over the property of their parents once it is bestowed to them and turn the parents out to lead a life of destitution. Of course, this is an extreme case; but one can cite several instances of day-to-day interactions in which parents are humiliated. The difference between the ideal and the real is indeed present and noticeable.

The Phenomenon Of Sandwich Culture

The concept of culture that we have discussed was evolved by scholars studying uni-cultural societies—small tribal societies that were regarded as non-changing, western societies sharing a common civilization, and large indigenous societies of the East having a civilizational spread. Such large societies became some sort of melting pot in which regional and religious cultures merged and became sub-cultures. India has been described as an indigenous civilization which developed a great tradition and allowed little traditions to flourish. The interactions between the two traditions resulted in some local traditions becoming widely accepted and part of the great tradition, and some of great traditions being redefined at lower levels or going out of use completely. These processes were named Universalization and Parochialization, respectively (Marriott, 1955). These processes were seen as operating within a culture.

Very little attention was, however, paid to the diaspora communities. The Chinese and the Indians are the two groups that are ubiquitous in the sense that they are to be found in almost all countries of the world and in substantial numbers. While these groups have succeeded to a remarkable degree in accommodating themselves in the societies of their migration, they have also retained their cultural identities. However, their unique identity neither corresponds to their parent culture nor to the host culture. In a multicultural milieu—now a feature of most societies of the world, thanks to the process of globalization—the cultures of the migrant groups defy their classification as a sub-culture. A multicultural society is by definition a society with many cultures. However, these cultures are to be seen somewhat differently as operating within the overall umbrella of the distinct culture of the host society.

While scholars differ in their assessment of the degree and extent to which institutions transplanted from India into other cultures by Indian immigrants have retained their originality, they all seem to hint at the continued presence of ‘Indianness’. It is this phenomenon that seems to provide these migrant communities with an identity distinct from other groups in the plural societies of their relocation. They have carried the norms of behaviour with them and reactivated several structural and cultural features of their parent culture while making adjustments and adopting local customs, thus striking a new equation—a consequence of sandwiching. The different equations provide different profiles and distinguish them not only from the non-Indians of the host society, but also from other overseas Indians, and the Indians in India.

The era of globalization is characterized by the increasing mobility of people across cultures. This has led to the formation of what may be termed sandwich cultures (see Atal, 1989). Migrant groups evolve their own mechanisms to preserve their cultural identity and yet develop interfaces with the culture of the host society. The emerging culture of the immigrants is the result of sandwiching the forces of the host culture and the parent culture. Since people have moved to different cultures across the world, the sandwich cultures of peoples originating from the same country also differ from one host country to another. The existence of sandwich cultures makes native cultures more diverse and heterogeneous.

The concept of sandwich culture is applicable at several levels:

- At the country level:

The culture of the entire country may be a result of the process of sandwiching between the powerful pressures from two or more civilizations. Thailand offers a good example of this type, which has emerged as a result of sandwiching between the Indian (mainly Buddhist) and Chinese civilizations. The language (vocabulary and the script) and religion (including the institution of monarchy) represent the influence of Indian civilization (see Desai, 1980). Its food habits, some patterns of dress, and tonality in language as well as business ethic is derived from the Chinese. However, the Thai culture is a distinct identity, and not a sub-system of either the Chinese or the Indian cultures. Its orientation to India and China is not comparable to the opposing processes of host and parent cultures. Thai culture is an emergent form that has assimilated elements of the two external influences with the native Thai culture.

- Within the country level:

- Immigrant communities: People of Indian or Chinese origin, for example, settled in other countries offer instances of immigrant communities. Sandwich cultures are created among them. It is this culture that is transmitted to the newer batch of immigrants who come and settle in the same locality as add-ons or replacements. The old inhabitants ‘socialize’ and ‘enculturate’ the newcomers, and thus make their adjustment in a strange environment relatively smooth. These groups define their own areas of interaction, create aperture points for an interface with the host culture, and set up their membership boundaries.

- Autochthonous communities: These groups overwhelmed by invading immigrants also develop sandwich cultures as a result of a breakdown in their isolation. The modern Maori in New Zealand, the aboriginals in Australia, and the several tribal communities in India exemplify this type.

- Frontier groups: Communities located on the frontiers of a given political system receive influences from the neighbouring country with whom they have a frontier in common. For example, the residents of Southern Thailand exhibit a mix of Thai and Malay cultures.

- Refugee communities: They constitute another type with a potential for a sandwich culture.

- Returnee culture: There is a recent phenomenon of reverse migration, also called ‘sea-turtling’. These people exhibit a peculiar ambivalence. Back in their parent country, they locate themselves in a distinct colony that is modelled after the country of their migration. Many of these people possess dual passports. In their case, the interactions with the parent culture increase and that of the host culture decline, and yet the host culture continues to be their positive reference group, and they live in the hope of returning one day. In their own country of origin, they create a mini-country of their migration. If Indians settled in Singapore created a ‘Little India’ on Sirangoon Road, Indians returning from the US and settling in the city of Bengaluru have created a mini-USA in Adarsh Palm Meadows in Whitefield.

A sandwich culture, in a restricted sense, is a culture of the outside group settled in a different country/setting, and is the product of opposing pressures from the parent and host cultures. Although it cannot be completely insulated from the culture of the host society, it is created when members are able to retain their boundaries in terms of membership. It keeps its apertures open to both the parent society and the host society, and thus influences flow from both sides, thereby shaping a distinct cultural fabric with warp and woof drawn from the two cultures.

The following are the characteristics of a sandwich culture:

- It is a culture that emerges as a consequence of twin pressures—that of the original parent culture and the strange culture. When this occurs within the same habitat, it is seen more as an instance of culture change, where the arriving culture might invade or overwhelm the native culture. In these cases, the original culture represents the ‘past’ or the ‘ideal’ culture, and external elements are seen as evidence of modernity. When it occurs in a strange setting—the country of migration—the original culture remains the ‘parent culture’, and the culture of the country of migration becomes the ‘host culture’. The host culture may be hospitable or hostile; and it is this feature that determines the character of the emerging sandwich culture.

- People living a sandwich culture possess a ‘double identity’12 as Indian-American, Thai-Chinese, etc. And they exhibit a certain degree of ambivalence and have a double orientation. When an Indian NRI stays in the US he misses India, and when he visits India, he misses the United States.

- A sandwich culture develops in a country only when there is a critical mass of people from another culture. When individual families move to another country, they are either absorbed into the host culture or remain foreigners (who are seen as sojourners).

- Sandwich cultures created by people from the same stock vary from country to country, depending on (i) the attitude of the host country, (ii) the amount of exposure to the parent culture, and (iiii) the amount of exposure to the host culture. These can be measured in terms of insulators and apertures—such as language, endogamy, food habits, racial prejudice, and an urge to return to their roots. When we talk of a sandwich culture within the same country of origin, this can be seen in terms of the integration of a community into the mainstream. Several revival movements, now couched in terms of ethnicity, are indicators to return to the past, to the original, to stress on indigeneity. These movements result in rediscovering and reviving old traditions and discarding some of the traits adopted from the wider culture.

The concept of sandwich culture helps in understanding the process of globalization in sociological terms. It offers a helpful paradigm for the study of the diaspora.

This phenomenon is easily visible amongst the Thais, Koreans, Malaysians, and Pakistanis. In his book on Cubans settled in Miami, The Exile, David Rieff talks of ‘Cuba in the heart of Miami’, and describes the lives of Miami’s Cubans as ‘torn between the imagined Eden of their homeland and America’s irresistible attraction’. A very different view of a sandwich culture can be had in a fascinating history of the Chinese in America, by Iris Chang. The blurb of the book calls it an epic story

that spans 150 years … [that] tells of a people’s search for a better life—the determination of the Chinese to forge an identity and a destiny in a strange land, to help build their adopted country, and often against great obstacles, to find success.

Now, with the opening of Mainland China, it is possible that the ‘sea turtle’ phenomenon has unravelled in the case of the American Chinese. Non-resident Indians returning to India for work also offer an excellent opportunity to study the phenomenon of return migration—sea-turtling. Although living in India, many of them have settled in newly developed colonies that are like alien islands in an Indian sea.

Appendix 4.1

American anthropologist Ralph Linton wrote the following essay, which appeared in the American Mercury in 1937. Published half a decade before ‘globalization’ became a buzz word, it humorously illustrates how everyday routine in modern America is the sum of years of global human ingenuity.

One Hundred Per cent American

There can be no question about the average American’s Americanism or his desire to preserve this precious heritage at all costs. Nevertheless, some insidious foreign ideas have already wormed their way into his civilization without his realizing what was going on. Thus dawn finds the unsuspecting patriot garbed in pajamas, a garment of East Indian origin; and lying in a bed built on a pattern which originated in either Persia or Asia Minor. He is muffled to the ears in Un-American materials: cotton, first domesticated in India; linen, domesticated in the Near East; wool from an animal native to Asia Minor; or silk whose uses were first discovered by the Chinese. All these substances have been transformed into cloth by methods invented in Southwestern Asia. If the weather is cold enough he may even be sleeping under an eiderdown quilt invented in Scandinavia.

On awakening he glances at the clock, a medieval European invention, uses one potent Latin word in abbreviated form, rises in haste, and goes to the bathroom. Here, if he stops to think about it, he must feel himself in the presence of a great American institution; he will have heard stories of both the quality and frequency of foreign plumbing and will know that in no other country does the average man perform his ablutions in the midst of such splendor. But the insidious foreign influence pursues him even here. Glass was invented by the ancient Egyptians, the use of glazed tiles for floors and walls in the Near East, porcelain in China, and the art of enameling on metal by Mediterranean artisans of the Bronze Age. Even his bathtub and toilet are but slightly modified copies of Roman originals. The only purely American contribution to tile ensemble is tile steam radiator, against which our patriot very briefly and unintentionally places his posterior.

In this bathroom the American washes with soap invented by the ancient Gauls. Next he cleans his teeth, a subversive European practice which did not invade America until the latter part of the eighteenth century. He then shaves, a masochistic rite first developed by the heathen priests of ancient Egypt and Sumer. The process is made less of a penance by the fact that his razor is of steel, an iron-carbon alloy discovered in either India or Turkestan. Lastly, he dries himself on a Turkish towel.

Returning to the bedroom, the unconscious victim of un-American practices removes his clothes from a chair, invented in the Near East, and proceeds to dress. He puts on close-fitting tailored garments whose form derives from the skin clothing of the ancient nomads of the Asiatic steppes and fastens them with buttons whose prototypes appeared in Europe at the Close of the Scone Age. This costume is appropriate enough for outdoor exercise in a cold climate, but is quite unsuited to American summers, steam-heated houses, and Pullmans. Nevertheless, foreign ideas and habits hold the unfortunate man in thrall even when common sense tells him that the authentically American costume of gee string and moccasins would be far more comfortable. He puts on his feet stiff coverings made from hide prepared by a process invented in ancient Egypt and cut to a pattern which can be traced back to ancient Greece, and makes sure that they ire properly polished, also a Greek idea. Lastly, he tics about his neck a strip of bright-coloured cloth which is a vestigial survival of the shoulder shawls worn by seventeenth century Croats. He gives himself a final appraisal in the mirror, an old Mediterranean invention, and goes downstairs to breakfast.

Here a whole new series of foreign things confronts him. His food and drink are placed before him in pottery vessels, the proper name of which—China—is sufficient evidence of their origin. His fork is a medieval Italian invention and his spoon a copy of a Roman original. He will usually begin the meal with coffee, an Abyssinian plant first discovered by the Arabs. The American is quite likely to need it to dispel the morning-after effects of overindulgence in fermented drinks, invented in the Near East; or distilled ones, invented by the alchemists of medieval Europe. Whereas the Arabs took, their coffee straight, he will probably sweeten it with sugar, discovered in India; and dilute it with cream, both the domestication of cattle and the technique of milking having originated in Asia Minor.

If our patriot is old-fashioned enough to adhere to the so-called American breakfast, his coffee will be accompanied by an orange, domesticated in the Mediterranean region, a cantaloupe domesticated in Persia, or grapes domesticated in Asia Minor. He will follow this with a bowl of cereal made from grain domesticated in the Near East and prepared by methods also invented there. From this he will go on to waffles, a Scandinavian invention with plenty of butter, originally a Near Eastern cosmetic. As a side dish he may have the egg of a bird domesticated in Southeastern Asia or strips of the flesh of an animal domesticated in the same region, which has been salted and smoked by a process invented in Northern Europe.

Breakfast over, he places upon his head a moulded piece of felt, invented by the nomads of Eastern Asia, and, if it looks like rain, puts on outer shoes of rubber, discovered by the ancient Mexicans, and takes an umbrella, invented in India. He then sprints for his train–the train, not sprinting, being in English invention. At the station he pauses for a moment to buy a newspaper, paying for it with coins invented in ancient Lydia. Once on board he settles back to inhale the fumes of a cigarette invented in Mexico, or a cigar invented in Brazil. Meanwhile, he reads the news of the day, imprinted in characters invented by the ancient Semites by a process invented in Germany upon a material invented in China. As he scans the latest editorial pointing out the dire results to our institutions of accepting foreign ideas, he will not fail to thank a Hebrew God in an Indo-European language that he is a one hundred percent (decimal system invented by the Greeks) American (from Americus Vespucci, Italian geographer).

Appendix 4.2

The Times of India, 4 June 2009 published a list of words freshly coined by the students, forming as if a new DU Dictionary. These words and their meanings are reproduced here.

DU Dictionary

Univ Meaning: Delhi University. University of Delhi, isn’t that a lengthy name? Univ is more like it—short and cool.

Campus Meaning: North Campus. While campus is a generic term in DU, the word means only and only North Campus. Do not make the mistake of calling the South Campus by the same name.

KNags Meaning: Kamla Nagar. One of the hippest markets near the Campus. KNags is your one-stop complex for books, branded clothes and even a small flea market.

CBats Meaning: Chole Bhature; Eating Chole Bhature is so out of fashion. Cool people eat CBats.

GJams Meaning: Gulab Jamuns. After CBats, if your sweet tooth is nagging you, what better way to indulge than by gorging on some GJams? And for god’s sake, don’t call them Gulab Jamuns!

Soc (pronounced as Sock) Meaning: A cultural or departmental group which is called a society. Once you are in the univ, you’d have to be a part of a dance, music or literary Soc.

Res Meaning: The college hostels are popularly called Res, probably a short form of residents. Also, a resident of the college hostel is called a Res.

Amma Meaning: Hostel warden—never mind the gender. It’s not because they remind you of your mother, but hostel wardens are generally referred to as Amma as they keep a check on the students and try to make sure that the res follow rules.

Vella Meaning: A person who has nothing to do in life and is simply whiling away time. Vellagiri, the act of being Vella.

CATing Meaning: If you are preparing for CAT then you are CATing.

Dope-chi Meaning: A person who takes drugs or who looks like s/he takes drugs. A shabby hairdo (which is the in-thing at the Univ these days), black or grey T shirt, dark thick kajal (for girls), chappals, and a gait that says ‘Whatever, man!’ are the traits that mark a Dope-chi. Most of them are loners, who like to keep to themselves and are rock music fans.

BTMs (short for Behenji-Turned-Mod) Meaning: Girls who were behenjis by DU standards when they were freshers but have undergone a sea change over the years. However, a DU student says, it’s not too hard to trace BTMs in the campus as they still speak with their native accent. Also, their attitude is a dead giveaway.

Biyatch Meaning: Distorted version of B**ch. This word comes in handy when you have to abuse a good friend of yours, pyar se. What’s more, the term can be used for both boys and girls. You obviously can’t call your friend a b**ch, right?

Dramchi Meaning: A drama queen or a melodramatic person, also, someone who cooks up stories.

Yava Meaning: It’s something like embarrassment. Whenever you find yourself in a situation when you don’t know what to do, or when someone asks you some embarrassing question, the answer for which you don’t have, or when someone pulls your leg and you don’t know how to react, you become Yava.

Khapeter Meaning: When you fall short of words to describe someone who’s very mischievous, you simply call him or her a Khapeter.

Here are few more words that would come in handy when you are in DU

Jahnkees: People who overdress and especially boys who wear ekdum tight shirt and faded lose pants and sport bleached hair.

Ricks: For rickshaws

Sutta: For cigarettes, joints and dope

Adda: Hangouts

Some other code words have recently become part of the vocabulary of the Teens to outwit their elders. Here is a sample:

FWB |

Friends with Benefits: It is used for the friends of the opposite sex who fulfil needs without commitment, with no demands, and no problems. |

UMFRIEND |

Boyfriend |

LMAO |

Laughing my Ass Off |

ILU |

I Love You |

ITILU |

I think I Love You |

THUD |

Depressing |

8 |

Oral Sex |

SEXTING |

Sexual Text Message |

@@@ |

[SMS] Parents are nearby |

C-P |

Feeling Sleepy |

BF vs. GF |

Casual hugging of boyfriend, but not in front of your parents |

PLENTY CHOICE |

Multiple Dating |

BASIC INSTINCT |

First step: Kissing; Second step: Kissing and Hugging; Home Run = Sex. |