CHAPTER 7

Social Interaction and Social Structure: Status and Role

Preliminary Remarks

The social sphere consists of the interactions of pluralities of human individuals. These interactions lead to the formation of social systems and account for their continuity as well as change. That is why, in sociological analysis, we do not focus on the individual as a biological being, or even as a personality. These are the fields of specialization for physical anthropologists and psychologists, respectively. Both biology and psychology, of course, influence the performance of the individual as a culture bearing and a culture creating actor interacting with his/her counterparts. It is this latter aspect of role playing that is the concern of sociology.

In sociology we treat an individual as one carrying a bag of statuses and performing various roles associated with them. As a member of a social group, including society, an individual is a bundle of statuses.

We shall introduce the interdisciplinary perspective in the analysis of the social system that is drawn principally from biology, psychology, and cultural anthropology, and integrated into sociology. It is because of this integrated approach to understanding the social sphere in its totality that some sociologists prefer to designate society as a socio-cultural system. As Parsons would clarify, the focus of the analysts of the social system is on the conditions involved in the interaction of actual human individuals who constitute concrete collectivities with determinate membership. As against this, the focus of the analysts of the ‘cultural’ system is ‘on the patterns of meaning, e.g., of values, of norms, of organized knowledge and beliefs, of expressive form’.1 That is the reason why we had discussed the key concepts of society and culture in two separate chapters.

It is through institutionalization that integration of the two systems—society and culture— is achieved. Institutionalization is to be understood in terms of creating permanent structures—as subsystems within a society—and the values and norms governing their functioning.2

In Chapter 5, we talked of the groups and sub-groups that are the key components of a society. Like the society, they are also collectivities composed of individuals as members.

In this chapter we shall first focus on the individuals—as status holders—who are the basic ingredient of any social system. Then, we shall proceed to examine other aspects of institutionalization.

Individuals As Status Holders And Role Players

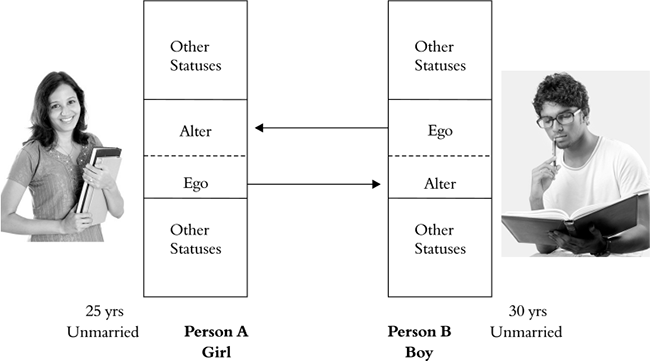

When two persons ‘interact’ with each other, each interacting person (called technically an ego) takes account of the other party (called technically alter). The ‘alter’ is not merely a physical object, but a person with a congeries of statuses, related attitudes, expectations, and with the capacity to pass judgement. The ego takes note of all these while transacting business with alter. Similarly, assuming the role of an ego, the alter takes note of all these features of his alter. In this sense, an interaction is a transaction where both parties don the roles of ego and alter by turn.

The action initiated by individual (A) as an ego depends on the manner in which (A) perceives the other party—individual (B) called alter; similarly, the response of (B)—the alter—[while responding (B) becomes the ego] depends on how he/she (B) interprets the message and the status of the sender (A). The action of each of the two parties is thus based (i) on his/her attitude towards the other, and (ii) his/her expectations about the other’s possible reactions to him. Any wrong perceptions would lead to a crisis in the relationship. This is true when one is interacting with an unknown person, or with an acquaintance (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Situation of Social Interaction

There is an oft told story of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar. One of his admirers expressed the desire to personally pay him visit. He informed Vidyasagar of the schedule of his visit— the date, the train, and the time of arrival. The visitor arrived by train at the appointed time. While climbing out of the first class compartment, he yelled for a coolie, but none was in sight. So he had to unwillingly unload his baggage onto the platform. A dhoti-clad passerby offered to carry his baggage. The visitor accepted the offer. Upon reaching his destination the visitor took out his wallet to pay the porter. At that time, the stranger told him that he was Vidyasagar, and that he had come to the station only to receive him. The visitor felt sorry at the disrespect he had shown. But Vidyasagar calmed him.

There are several such stories associated with Vidyasagar. To quote one more instance: Vidyasagar learnt that a person of poor means had died in a distant locality and the widow did not have the means to arrange for her husband’s funeral. Not intending to hurt the self-pride of the widow, Vidyasagar visited the house incognito and told the widow that he had come to return part of the money that he had borrowed from her husband, and was indeed very sorry to learn of his sudden demise. He gave a bundle of notes to the widow with the promise that the remainder of the sum that he owed would be repaid soon. The widow believed Vidyasagar and accepted the money that helped her arrange the funeral.

Both these are instances of mistaken identity that guided the interaction. The situation would have been different had the real identity of Vidyasagar known to the two parties—the visitor at the railway platform and the widow. The visitor could not recognize Vidyasagar and mistook him for a poor villager. Vidyasagar did not disclose his identity but recognized the visitor. The visitor suffered huge embarrassment. Similarly, it is quite possible that the widowed woman might have refused the monetary assistance had she known that the donor was a well-known philanthropist.

Robert Bierstedt has quoted a similar story from the United States in his book, The Social Order. The story concerns the doctor who, upon completing his examination of a young woman, said,

‘Mrs. Jones, I have very good news for you.’

‘My name,’ the young woman replied, ‘is Miss Jones, not Mrs Jones,’

‘In that case,’ said the doctor, ‘I’m afraid I have very bad news for you.’

‘This is not a very good story’, says Bierstedt, ‘body but it does illustrate the importance of status. The same physiological condition that in one status would be good news is bad news in another’ (Bierstedt, 1963: 257–58).

These small stories hint at a major sociological truism. A proper dialogue between two parties occurs only when their relative statuses and associated expectations are correctly known to each other. Mistaken identities lead to wrong behaviour.

Comparable situations appear constantly, if less dramatically, in the lives of all of us. A significantly large number of the social interactions between people in a complex society … are status interactions and not personal interactions. A contemporary college student, for example, has social relations with barbers, bank tellers, bus drivers, ticket takers, registrars, and deans. It is of vital importance to recognise that he can, and probably does, have social relationships with al of these people without knowing their names or indeed anything about them–except their status. Nor, in turn, do they need to know his name or anything about him–except his status (Bierstedt,1963: 258).

It is for this reason that people carry status indicators with them.

One good example of a status indicator is that of dress diacriticals. The dress we wear announces our status as male or female. Men and women dress differently. In traditional India, a Hindu woman’s status as unmarried, married, or a widow could be told by the type of dress worn by her. Similarly, people of different Hindu sects could be identified by the type of tilak (sandalwood paste marking) on the forehead. Circumcision among the Muslims distinguished them from the Hindus, and has been used as an identity indicator. A burqua distinguished a Muslim woman from Hindu one. Dresses also served to distinguish people of different regions even within the same country. A ban was imposed in France some 200 years ago prohibiting women from wearing trousers in Paris. It stipulated that any Parisiene wishing to ‘dress like a man’ must seek permission from the city’s main police station3 In the changed circumstances, many of these traditional dress diacriticals are disappearing, and yet the so-called ‘unisex’ dresses also have some subtle clues to assist in the identification of the sex of the wearer. An obvious example is the placement of buttons on shirts and jackets—male dresses have them on the right side, female dresses on the left.

Situation Of Social Interaction

Negotiating a social relationship can also be understood by way of another example.

A person has to negotiate a distance to reach a desired destination. Thus the person is an actor (a traveller), and the destination is his/her goal. To reach the destination, he has to cover a distance, symbolized by the road. The distance can be covered either on foot, or by a motorized vehicle. The amount of time taken in negotiating that distance would depend upon the speed of the vehicle, amount of traffic on the road, traffic lights, and the weather. Thus, the effort to cover the distance is influenced by the ‘means’ one employs to reach the destination, the ‘conditions’ (man-made and nature-made) on the pathway, and the mental frame of the actor-traveller. See the number of concepts that are invoked in this simple act: actor, goal, means (when an actor has choice-options), conditions (over which the actor has no control, and they remain unchangeable; the moment they can be altered, they move to the category of means), traffic rules, and state of mind (influenced by his social status and experience of immediate previous actions and interactions, and past experience of travelling). A sociological analysis of a short journey undertaken by our actor in this story would require covering all the above-mentioned concepts.

This is, in essence, the Theory of Social Action, propounded by Talcott Parsons and his associates, and which shaped the sociological orientation, giving it an interdisciplinary character—combining the insights provided by previous work in the fields of sociology, anthropology, and social psychology.

In sociological analysis, the ‘essential starting point is the conception of two (or more) individuals interacting in such a way as to constitute an interdependent system’, writes Parsons (1965: 41). Sociological analysis does not focus on the individual as a person,4 but on his particular status vis-à-vis his alter (counterpart) in an interaction system. In other words, the unit of analysis is ‘status’ and not the individual. In this sense, as a status holder, an individual is a component of the system constituted by two or more status holders of the same or different rank, or specialization. When we analyse a social system, we see the participants in terms of the ‘status’ (defined by the role expectations) or ‘position’ (rank in the hierarchy within the system) they hold, and not as a totality of the statuses that each individual occupies at a particular point in time.

It must be said, however, that some scholars use these words—status, position, and role– as interchangeable, and designating a common phenomenon. This is confusing and must be avoided. Each of these words is a concept with a clearly defined meaning and, thus, not a synonym of any other two. Therefore, for purposes of clarity we shall make a distinction between status, social position, and role.

Concept Of Status And Role

In earlier sociological literature, status was used as a synonym of a person’s overall standing. MacIver, for example, used the word status in his discussion on class, and talks about various ‘bases of status’ such as birth and wealth, mode of living, occupational advantage, political power, etc. For him, status denoted one’s class or caste. This usage is no different from the way people commonly talk of ‘status’, with its connotations of influence, fame, or wealth. Several authors used status and role as interchangeable terms. In fact, many use the word Role when in fact they are talking about status. Even Talcott Parsons never bothered to insist on this distinction.

Johnson, on the other hand, uses social position as a generic term that consists of two parts: status and role. For him, status refers to the ‘rights’ associated with the position occupied by an individual in a social system and role refers to the ‘obligations’ that a status occupant has towards the system concerned. The members of a social system are differentiated according to the social position they occupy.

A social position is thus a complex of rights and obligations. A person is said to ‘occupy’ a ‘position’ if he has a certain cluster of obligations and enjoys a certain cluster of associated rights within a social system. These two are called role (referring to obligations) and status (referring to rights). The role structure of a group is the same thing as its status structure, because what is role from the point of view of one member is status from the point of view of others. This is shown in Figure 7.2.

Rather than making a distinction between position and status in each system of interaction, we would prefer to keep the concept of position at a higher pedestal—in terms of the overall standing of the person on society determined by the totality of statuses of any given individual. Merton has called such a totality a status set; we shall now explicate this concept.

As stated earlier, the term status is not used here in the popular sense meaning prestige or position or general standing. Popularly used phrases, such as status of ‘women’ or of ‘scheduled castes’ or of ‘scheduled tribes’ refer to general prestige; they should not be confused with the sociological concept of status.

Every status, in sociological terms, is part of an individual’s identity in specific arenas of social interaction. The first condition of any situation of interaction is that the parties involved in it must know who the other party is; a wrong identification of the status of the other party can lead to disastrous consequences in terms of interaction. To explain it further: while ‘status of woman’ is a non-technical use of the term, ‘woman’ is a status based on gender, and this status invokes socially acceptable behaviour toward the status occupant. Mistaking a woman for a man or vice versa can lead the other party to wrongful behaviour and result in confrontation or social disapprobation.5

To take the point further, the person, besides being a woman, also has several other status—a daughter, a college student or a lecturer, a fiancée, a passenger in a bus (temporary status), to list a few. The same would be true of any individual—male or female.

It is in this sense that we talk of an individual as a ‘bundle of statuses’, recognizing the point that not all statuses are activated simultaneously, and some statuses remain constantly present. Being an Indian or an American, a male or female, young or old are ‘backdrop statuses’ that influence the performance of the status holder in other capacities/statuses. Thus, while those working in BPOs—call centres—have a common status, a woman is treated differently, because of her status as a woman.6

Each status has associated rights for its incumbent, and also has its obligations—a status occupant is ‘obliged to’ perform those tasks, these constitute the role/s. In most cases, performances of these roles require a receiving party, which forms the ‘counter status’—the alter of the ego, the actor or status occupant in question. In theatrical language, an actor is seen as ‘playing the role’ of .... Here, the word role signifies status: hero, king, villain, a notable, a father, etc. Since it is in that capacity (read status) that he ‘acts’, the focus is, quite naturally on playing (meeting his obligations), and therefore, the ‘role’ dimension is specified. Here, the word role means the totality of actions associated with a particular status assigned to an actor in a drama or a film or a serial. In day-to-day language it may sound absurd to say that a particular actor is ‘playing’ the status of … (you do not play but occupy the status, and from that position you play different roles vis-à-vis your counterparts). Thus, role is an essential component of status.

Status Set and Role Set

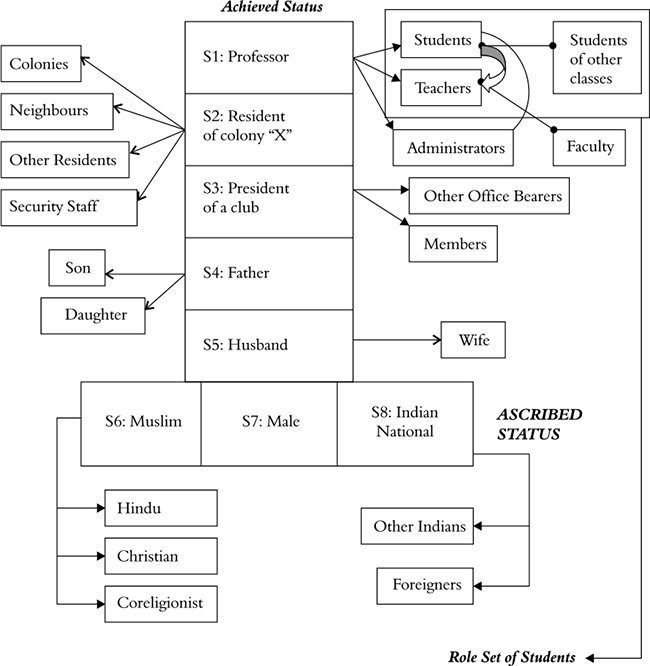

This concept of status set was introduced by Robert Merton. It indicates the totality of statuses that any individual has at any particular point in time, and makes every person unique. No two individuals would have the same composition or the same occupants in counter positions. It is this set that makes the individual a ‘bundle of statuses’. In a way, it is this set, or a selection of statuses from it, that gives an individual a social position, also known as a ‘station’ in society. Of course, not all status of an individual carry similar weight in determining the social position—the ‘class’—but they all influence the public image of the person. One configuration of the status set of a University Professor (Master Status) can be something as shown in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3 Status Set of a University Professor

This totality—there may be several more (for example, brother, son, membership to other professional bodies, etc.)—constitutes the status set of this imaginary person. Each of the boxes represents a status, and one may say that the combined weightage of some of these statuses gives this person a social position—a standing in society, a particular station. Each of these statuses has both rights and obligations. Some of these obligations are towards the others in the social system from where the status is granted. The vertical or horizontal7 listing constitutes a status set. And the counter statuses associated with each status block signify the range of obligations that a status occupant has by virtue of this occupancy. This is shown in Figure 7.4.8

For purposes of simplifying the Mertonian concept of status set, Loomis and Loomis have taken only four status of an actor. One of the status is that of a university teacher that involves, again as illustration, obligations vis-à-vis other (i) teachers, and (ii) students. Roles associated with these two counter statuses constitute a role-set. To quote Merton:

Figure 7.4 Schematic Diagram of Merton’s Social Structure Elements

Source:Charles P. Loomis and Zona K. Loomis, Modern Social Theories (1963: 282)

[A] particular social status involves, not a single associated role, but an array of associated roles. This is a basic characteristic of social structure. This fact of structure can be registered by a distinctive term role-set, by which I mean that complement of role relationships which persons have by virtue of occupying a particular social status. As one example, the single status of medical student entails not only the role of a student in relation to his teachers, but also an array of other roles relating the occupant of that status to other students, nurses, physicians, social workers, medical technicians etc. Again: the status of public school teacher has its distinctive role-set, relating the teacher to his pupils, to colleagues, the school principal and superintendent, the Board of Education, and, on frequent occasion, to local patriotic organizations, to professional organization of teachers, Parent-Teachers Associations, and the like (Merton, 1964: 369).

[T]he role-set differs from the structural pattern which has long been identified by sociologists as that of ‘multiple roles’. For in the established usage, multiple roles refer to the complex of roles associated, not with a single social status, but with the various statuses (often, in differing institutional spheres) in which individuals find themselves–the roles, for example, connected with the distinct statuses of teacher, wife, mother, Catholic, Republican, and so on. We designate this complement of social statuses of an individual as his status-set, each of the statuses in turn having its distinctive role-set …. The concepts of role-set and of status-set are structural and refer to parts of the social structure at a particular time …. The patterned arrangements of role-sets, status-sets and statussequences can be held to comprise the social structure (ibid.: 369–70).

Merton maintains that (see Figure 7.5).

… operating social structures must somehow manage to organize these sets and sequences of statuses and roles so that an appreciable degree of social order obtains, sufficient to enable most of the people most of the time to go about their business of social life without having to improvise adjustments anew in each newly confronted situation (ibid).

Figure 7.5 Status Set and Role Set

Source: Macionis, 2005: 143

These refinements of the concepts of status and role are useful in the analysis of the processes of integration. These elaborations lead a researcher to attempt answers to questions such as:

- ‘Which social processes tend to make for disturbance or disruption of the role-set, creating conditions of structural instability?’

- ‘Through which social mechanisms do the roles in the role-set become articulated so

that conflict among them becomes less than it would otherwise be?’9

In attempting to provide tentative answers to these, and similar questions, Merton (1964: 371–79)10 identified some of the mechanisms that help to reduce the situations of conflict in a social system. These are:

Mechanism of differing intensity of role involvement among those in the role-set. In any situation of interaction, the involvement of people varies, and hence, different persons in the role-set participate with different degrees of intensity. For example, in a parent–teacher association of the school, the involvement of each parent is mainly related to his or her child, whereas the principal of the school has a much greater involvement as this happens to be her key status. In such a situation, conflicts may occur between the principal and the leaders from among the parents. At home, parents have equal involvement vis-à-vis their children; and thus, there is greater possibility of a role conflict.

Mechanism of differences in the power of those involved in a role-set. This is an extension of the same point. In an association, office holders enjoy more power than the ordinary members, and this reduces the chances of conflict.

Mechanism of insulating role-activities from observability by members of the role-set. When the role performance is disallowed to be observed, those not observing are prevented from commenting—favourably or unfavourably. A classroom is a good example. The role of the teacher is observable only to the students in the class, but not to other colleagues; hence, there is less chance of conflict between teachers on matters related to the classroom.

Mechanism making for observability by members of the role-set of their conflicting demands upon the occupants of a social status. In those circumstances where conflicting demands are made by members of the role-set, the best option for the status occupant is to make his/her performance observable to others in the role set to appreciate his/her dilemma. A teacher seen checking homework in the staff room makes it observable to other peers that the party concerned is busy, and not able to attend to their other demands. (It sends the message: Don’t you see how much work I have? How can I accept additional responsibility?)

Mechanism of social support by others in similar social statuses with similar difficulties of coping with an unintegrated role-set. People of identical status suffering from a common set of conflicting demands from other members of the role-set organize themselves to resist the conflicting demands made by others in the role-set.

Abridging the role-set, involving disruption of role-relationships. Another mechanism related to limiting the size of the role-set so that the volume of demands made and the cluster of differing demands become manageable.

Ascribed And Achieved Status

Statuses are of two types: Ascribed and Achieved.

Ascribed Status

An ascribed status is an assigned status. It is given by the society or the social group, without regard to any particular or unique abilities or qualities of an individual. This is also called status by birth. Our gender, nationality, parentage, race or caste, religion, and even our age are ascribed statuses, in the sense that we have not chosen them; they came by birth. Of course, some of these statuses can be changed. For example, our nationality can be changed by seeking nationality of another country which makes us a ‘naturalized citizen’ of the adopted country. When British India was partitioned into two nation-states upon attaining independence from colonial rule, people residing in the areas that went to Pakistan automatically became nationals of the new-found state, losing their Indian nationality; and the Indian nationals became aliens in the land that was previously part of India, but now belongs to a new found country.

Similarly, religion is changeable through conversion or proselytization. Now modern medicine has also made it possible to change one’s gender! There is a third gender which was untile recently enumerated as ‘male’ in India, though there were distinct feminine dresses and spoke a feminine tongue. The Government of India put them in the category of ‘other gender’.

Characteristics that have a biological base are generally unchangeable, and are thus ascribed and given social and cultural meaning. Even a condition such as epilepsy in a person has been culturally defined in some societies as visitation of a spirit or a deity, and the epileptic patient derives an ascriptive status from that condition.

We must also note that a similar ascriptive status may have different meanings in different societies. A woman in a matrilineal society and a woman in a patrilineal society carries the same ascriptive status associated with gender, but the rights and privileges attached with this status vary in the two systems and even in different matrilineal and patrilineal societies. In Hindu society, for example, a woman is compared to a devi—a goddess. Amongst the Hindu, during the navratri period—nine days of fasting observed both by males and females— young virgins are worshipped. In Nepal, a Hindu girl-child is chosen and kept in a temple where she is worshipped as a living goddess. Devotees visit the temple to pay obeisance to her. She remains a virgin for the entire life.

The long history of protests in South Africa against Apartheid, and social movements in India to safeguard the interests of the dalits (scheduled caste and other backward class people) and the scheduled tribes are examples of efforts to erase distinctions based on ascriptive status. However, it is also interesting to note that as a consequence of positive discrimination favouring such groups, the people belonging to them have opted for the retention of that status. Also other ascriptive groups who had succeeded in ascending the hierarchical ladder are being prompted to return to their original ‘status’ or even claim a lower status, thus, preferring to maintain the ascriptive status.

Achieved Status

An achieved status, by definition, is the reflection of a person’s achievement. A person has to earn that status; it is not just given on the basis of one’s pedigree. In other words, it is not dynastic or hereditary. All the status in the public domain are, thus, acquired by a person, that is, through achievement, not by birth, that is, through ascription. When any public status is ascribed, such as that of a king, it is an ascribed status, and is not available to anyone else; but a revolt against the throne may result in installing the leader of the coup as the new king; but again, it becomes an ascribed status for his heir-apparent.

Even the marital status of a person is an achieved status. Through marriage a person becomes a husband or a wife, and achieves ‘in-law’ statuses (son-in-law, brother-in-law, or daughter-in-law, sister-in-law) all at once, which are technically called affinal relations. Similarly, a person becomes a student, a hosteller, an employee, a club member, member of a student body: All these are achieved statuses.

Every person has a combination of ascribed and achieved statuses. Depending upon the situation of interaction, any of these statuses gets primacy. Even in situations where a person’s achieved status is needed, the ascribed status of a person may be brought into the picture to reinforce or weaken the position of the person (see Figures 7.6 and 7.7). Complaints of nepotism in government departments are an example of this. Where two candidates, for example, have an equal achieved status (in terms of qualifications or marks obtained in an examination) required for eligibility for ‘interview’, a candidate might be chosen on the basis of his/her ascribed status as an additional criterion. The reservation criterion in government jobs for persons of SC or ST status is a case in point. Similarly, a child of a dignitary (ascribed status) may be given special treatment in an official transaction; he may be allowed to jump the queue, say in a hospital, or in a theatre.

Meira Kumar Formar Lok Sabha Speaker

(Source:© www.indiatodayimages.com)

In political circles in India, the debate regarding democracy versus dynasty can sociologically be seen as a conflict between ascribed and achieved status. In the Fifteenth Lok Sabha (House of People in the Indian Parliament), a lady Speaker was chosen for the first time. Commenting on this, Sagarika Ghose, a journalist, wrote the following in The Hindustan Times of 10 June 2009:

The speeches made by the PM and other ministers during the election of Meira Kumar as Speaker were telling. We were not told about the qualities of Kumar or her unique suitability for the post of custodian of the Lok Sabha. Only Kumar’s virtues as a ‘Dalit’. ‘Daughter of Jagjivan Ram’ and a ‘woman’ were extolled, as if birth and background were sufficient justifications for such a crucial constitutional office ….

In the above text, read ascribed status for ‘virtues’ and achieved status for ‘qualities’ and ‘suitability’. The author is hinting at the precedence given to ascribed status over achieved status in the a democratic polity of India.12 Even Meira Kumar herself acknowledged this fact in an interview given to The Times of India (15 June 2009, New Delhi edition). This is what she said: ‘ours is a “janmapradhan” (read: giving precedence to ascription) and not “karmapradhan” (read: giving precedence to achievement) society. All achievements (emphasis added)—character, learning, sacrifice—are incomplete till your caste (that is, ascribed status) is revealed.’ This is a good example of the usefulness of the concepts of ascribed and achieved status.

Figure 7.6 Status-set of Individual ‘A’ and Associated Role Sets

Figure 7.7 Ascribed Status and Achieved Status

Status Exit Or Role Exit

Contrary to ascribed statuses, which remain unaltered as seen above, achieved statuses can be lost or taken away. Meira Kumar had to resign from the ministership to which she was sworn in only a few days ago in order to be a candidate for the position of speaker. A political party, likewise, may also cancel the membership of a leader on the grounds of defection or disobedience. A medical practitioner can lose his/her licence to practice if found indulging in unethical practices.13

Also, some of the achieved statuses can be time-bound. One remains and retains an Non-Resident Indian (NRI) status only so long as one lives abroad. Upon his/her final return to India, he/she loses that status; of course he/she might earn the status of a former NRI—an ex-NRI.

The significance of this aspect of status (namely former status) has recently been recognized and is conceptualized as role exit or status exit. Attention to this feature was first drawn by Helen Rose Fuchs Ebaugh in 1988, in her book Becoming an Ex: The Process of Role Exit.14 Ebaugh developed this concept based on her personal experience and supplemented it with a series of 185 interviews. Ebaugh left the life of a Catholic nun to become a wife, mother, and a professor of sociology. As an ‘ex’ nun, she experienced difficulties in creating a new identity of her own as her past continued to overwhelm later statuses.

She conducted an enquiry to find out whether what she personally experienced was common to other instances of role exit. Drawing on interviews with ex-convicts, ex-alcoholics, divorced people, mothers without custody of their children, ex-doctors, ex-cops, retirees, ex-nuns, and even transsexuals, she came out with an inventory of role changes involved in the process of a voluntary exit from a particular ‘role’ (we would substitute ‘status’ for it). The status exit process involves disillusionment with a particular identity, search for an alternative status, turning points that trigger a final decision to exit, and finally creation of an identity as an Ex.

We had earlier mentioned that people carry status—the master status—even after they retire. A retired Colonel or Brigadier is always addressed as Col. Sahib or Brigadier Sahib even after his retirement.15 A professor is addressed as professor after his exit from the university campus—after retirement or after taking a new assignment in the government or the corporate sector. In this sense, a status exit—which Ebaugh would call a role exit— does not always mean an end of that status. With the prefix ‘Ex’ (whether used as term of address or not), the vacated status continues to be a part of the status-set of an individual, of course as a past referent.

Ebaugh has argued that the experience of becoming an ex is common to most people in modern society. Unlike individuals in earlier cultures—who usually spent their entire lives in one marriage, one career, one religion, one geographic locality—people living in today’s world tend to move in and out of many statuses. These are important ‘passages’ or ‘turning points’ in a person’s life, and they need to be studied sociologically. It could be a good subject matter of study among the senior citizens, whose numbers are going to go up in the coming years.16

A status exit is thus a process that begins while the person occupies a particular status. An exit is caused when a person is not happy or is disillusioned with that position, or when the norms of the organization necessitate the departure of the status occupant. A student enrolled in a school prepares for his exit when he/she is in the final year of the school; an employee begins preparing for his/her exit around the age of retirement; or a person begins to worry about his exit when the system throws him/her out for one reason or the other— the extreme case will be of a criminal who is condemned to death and awaits his hanging. Also, release of a convict from jail is an instance of status exit which poses crisis for the convict re-enter normal social life.

The circumstances leading towards an exit may vary, as do the feelings of the exiting status occupant in the first stage. The second stage is what Ebaugh calls, search for the alternatives. Again, this is guided by the circumstances that induce the process of exit. Departure from the system, that is, leaving the status, is another crucial stage both for the person exiting and the social system from which one exits. Farewell parties or exit rituals as well as features associated with dislocation and relocation are important parts of the social interaction process at this stage. The creation of a new identity, or entering a new role, is the final phase, which also differs from case to case depending on the type of exit. A bachelor getting married faces a different kind of crisis of adjustment than, say, a nun choosing to give up her nun-hood and entering into the lifestyle of a commoner as a wife, and a mother—the Ebaugh story. In the latter case, a person may be regarded as a deviant and therefore, may invite abnormal attention and social scrutiny or disapprobation.

A person undergoing this process encounters problems of relocation in the social space, creation of a new identity, and reviewing the range of alternatives. It should also be mentioned that the use of the prefix ‘former’ or ‘ex’ not only alters status, but also provides a hint to participants in a situation of interaction about the kind of treatment expected by that occupant. A retired IAS official visiting a government department does receive special treatment. So do retired professors, ministers, and other status holders in various situations of interaction. That is the reason why a retired person mentions his former master status after his name in his visiting card.

Status exit is also associated with rise in the hierarchy, or as the next step in the life cycle. Lecturers becoming readers, or readers becoming professors shed their previous designations—they are never called ex-lecturer or ex-reader. But a professor taking the role of a dean or a vice chancellor continues to be called a professor. This dignified term is a public status—in the sense that the common man in the street does not distinguish between a lecturer and a reader or a professor, and addresses all teachers in a college or a university as professors. Thus, lecturer and reader in the context of a college or a university are private status—status used internally.

Master Status

While any person occupies several statuses at any given point in time, he or she is publicly known by one of the statuses. Such a status is usually derived from one’s occupational status—a teacher or professor, a director of a company, a political leader, a minister, a clerk, etc. In childhood, a person is identified with the status of the father or the mother, while other statuses are disregarded. Master statuses can also change with time. In India, a lecturer is publicly addressed as professor, but soon upon getting a Ph.D. degree, his status changes and people begin addressing him/her as ‘Doctor Sahib’,17 although he remains a lecturer.

As mentioned above, it is necessary to make a distinction between public and private status. By private status is meant a specific status within an organization; public status is the generalized status as perceived by the people outside the organization. For example, university teachers are stratified in terms of their status as tutors, lecturers/assistant professors, readers/associate professors, and professors. But outside the system, a university teacher is deferentially referred to as ‘professor’, internal ranking notwithstanding. Similarly, cabinet ministers, ministers of state with independent charge, and ministers of state in the Indian cabinet are all addressed as ‘ministers’ by the public, and even by the media. The detailed nomenclature of their position is an internal matter.

In many situations of interaction, one of the ascribed statuses of an individual assumes the character of master status. A queue meant for women or for senior citizens invokes the status of a person as a ‘woman’ or a ‘senior citizen’ (aged 60 and above); all other statuses of the incumbent in that context become subsidiary. The status of ‘disabled’ is yet another example; at times it signifies bias against people with disabilities, as reflected in the choice of a spouse or while giving a job. In India, occupational castes undertaking menial jobs—including scavenging—were placed at the lower levels of the hierarchy and treated as ‘untouchables’ (denying social interaction with proximity). In their cases, their caste gave them the master status, ignoring their achieved statuses as skilled craftsmen or graduates. On this ground, the reservation policy followed by the Indian government is built and continually supported; the past of these castes is highlighted to justify their status as Dalits (oppressed), notwithstanding the change in the status of many in those castes due to education, income and a new occupational status. Similarly, racism prevailed on the basis of a master status determined by the colour of the skin.

In the modern sector, it is status in the employment or business sector that serves as a master status.

Status Sequence And Role Sequence

Within a particular organization an individual climbs the ladder and goes on to assume more and different responsibilities. Such promotions represent changes in designation. A movement from a lecturer to a reader and on to professor, and then to dean and to vice chancellor represents a sequence of statuses. There are also statuses that come first and other statuses add on to them, but do not replace the already existing ones. Thus, a girl is first a daughter, then a wife, then a mother and a grand mother. And she continues to have this set of statuses while adding new ones in this stream.

Status Conflict And Role Conflict

We have already alluded to the conflicts relative to statuses and roles earlier. Following Merton, it is suggested that a distinction be made between status conflict and role conflict.

Quite often role conflict is illustrated by the example of a judge in whose court his son appears as a convict. Such a situation creates a crisis for the judge; should he behave as a judge or as a father? This is not an example of role conflict. This is an example of status conflict, in the sense that judge and father are two separate statuses in the status-set of the person whose master status is that of a judge. A son is not a part of the role-set of a judge; similarly, a convict is not a part of the role-set of a father. In the role-set of the judge, his son appears as a convict. It is therefore a mistake to call this an instance of ‘role conflict’. Here, a person’s two statuses from his total status set are involved and the status occupant is faced with the conflicting demands made by the two statuses: as a father, the status demands that he should protect his son; as a judge, the status demands that he should remain impartial and objective in his judgement and ruling. This conflict can be resolved either by the status occupant’s refusal to handle the case as a judge, or by remaining neutral and not allowing extraneous factors (the fact of the culprit being his son) to influence his decision and judgement.

Role conflict, on the other hand, occurs within each of the statuses when counter statuses associated with that status, and constituting the role set, make conflicting demands on the status occupant and thus affect his role performance. As was said earlier, a role-set consists of those social positions that are structurally related to ego’s particular status, out of several statuses in his status-set. For instance, the role-set of a university teacher consists of his students, and his other colleagues in the department, and other employees of the university. Similarly, the role-set of a judge consists of other judges, the convict, the aggrieved party, the lawyers, the witnesses, and the observers. When these members of the role-set make conflicting demands on the judge in this case, or on the university teacher in the above case, they create for the judge, or the university teacher, a situation of role conflict. For example, if a teacher is asked by the head of the department to do other chores when she is expected to conduct her class, a situation of conflict will arise: the status occupant has to decide what is more important, taking the class or doing the job assigned by the head of the department. Such conflicts arise because the persons composing ego’s role-set occupy somewhat different positions from that of the ego and from one another. Consequently, their perspectives and interests are not quite the same. While they may agree on ego’s role obligations, they are likely to stress different things and make different interpretations.

Summary

All social groups, including the society, are arenas of social interaction; individuals engage in such interactions as occupants of specific statuses. Thus, for sociological analysis, it is not the individual but status that is the basic unit. This is the positional aspect of a situation of social interaction, focusing on the location of the ‘actor in question’ in the social system ‘relative to other actors’. The other aspect is processual. It focuses on ‘what the actor does in his relations with others’ in a given social system. This aspect is called role. It is in this sense that Parsons suggests that each actor in a situation of interaction is an object of orientation (other actors are oriented to the actor, and their actions amount to playing a role) and is oriented to other actors (plays a role from that position). Parsons instructs: ‘It should be made clear that statuses and roles, or the status-role bundle, are not in general attributes of the actor, but are units of the social system … the status-role is analogous to the particle of mechanics, not to mass or velocity’ (Parsons, 1952: 25). Thus, while individuals occupying a particular status may change—either due to death, or resignation, or promotion—the status remains relatively permanent as part of the social structure. It is in this sense that the saying ‘the King is dead, long live the King’ should be understood. For example, the position of the President of India, or of the prime minister, is a permanent feature of the Indian political system; however, its occupants have been changing over time. The role-sets associated with these positions also remain constant compared to their occupants.

Sociology focuses on the social actor seen as a ‘composite bundle of statuses and roles’, and not on the personality of an individual, which is in the realm of psychology. From the above, we can identify four different units of the social system:

- Social Act: it is performed by a social actor (status holder) and is oriented to one or more actors, holding counter statuses.

- Status-Role: ‘organized subsystem of acts of the actor or actors occupying given reciprocal statuses and acting toward each other in terms of given reciprocal orientations’ (ibid.: 26).

- Actor as a Social Unit: ‘the organized system of all the statuses and roles referable to him as a social object and as the “author” of a system of role activities’ (status-set and role-sets) (ibid.)

- Collectivity: the group also acts as an actor and as objects when a statement, for example, is made in the name of the group and not of any particular actor. When it is said ‘My government’ or ‘My team’, the reference is made to the collectivity, and not to any particular individual. The speech of the President of India before the parliament, for example, is not the ‘personal’ statement of the person occupying the position of President of India, but a statement on behalf of the government of the day.