CHAPTER 8

Structural–Functional Analysis

Introduction

Let us begin with a summary of the main points elaborated in the previous chapters.

As a study of the social sphere, sociology is concerned with those empirical systems that involve interactions of a plurality of individuals. These interactions—between two or more individuals (regular or casual), or between individual/s and a group, or between groups—follow a pattern governed by a society’s culture. Individuals interacting with each other in diverse settings constitute a collectivity, whose own boundaries are defined by the membership, thus transforming it into a social system with members who have set positions that give them a status and outline their roles. Thus, a system of rights and obligations is an inherent part of any social organization. The same structure exists in different societies, which are distinct only because of their specific culture, which provides patterns of meanings in terms of values, norms, organized knowledge and beliefs, and ways of expression—linguistic and symbolic.

To recapitulate: A social system is

- Made up of a plurality of interacting individuals.

- They operate in a situation that has a physical or environmental aspect.

- They are oriented towards the system, and are motivated ‘in terms of a tendency to the “optimization of gratification”’.

- The situation of interaction is ‘defined and mediated in terms of a system of culturally structured and shared symbols’ (Parsons, 1952: 5–6).

Sociologists make a distinction between social system, personality system, and culture system. When we analyse a social system, we deal with an individual not as a personality system, but as an occupant of a particular status that defines his duties and responsibilities towards others operating in the system in question. Personality, on the other hand, consists of the totality of an individual’s statuses in various social groups and the peculiarities of that individual’s behavioural patterns—his likes and dislikes, whether he is introverted or extroverted, his psychological make-up, which itself is developed through participation in various situations of interaction. Similarly, cultural system is different from the social system, although it is also a product of the interactions of a plurality of individuals. However, it is independent of them and outlives the lives of particular individuals. Culture is learned, it is transmitted, and it is shared. ‘Culture is on the one hand the product of, on the other hand a determinant of, systems of human interaction’ (Parsons, 1952: 15).

Functional Prerequisites And Requisites

For any system to function—that is, to become operational—there are some requirements to be fulfilled. They may be called preconditions. What are they?

A social system consists of interacting individuals. For a system to operate, therefore, it is essential that it has a regular supply of individuals to serve as actors. The first prerequisite for a social system is thus provision of membership. Members are actors who belong to it. Without membership, a social system is only a blueprint. Of course, the system lays down conditions for membership; it spells out in its charter (written or unwritten) who can become a member, and who is not permitted to become one. This is the recruitment dimension. Not only must a system have individuals who are ready to become members, it must also have norms concerning the replacement of members who retire, expire, voluntarily decide to quit, or are rusticated.

Implicit in this is also a condition: the system should ensure that neither the biological organism of its members nor their personality system is adversely affected. In other words, the system’s milieu should be compatible with the functioning of the members as individual beings. A social system has to adapt to provide for the minimum needs of individual actors. To take an example, for a society to exist, it would be necessary that the people constituting it survive—nutrition and physical safety will have to be ensured. Since humans are mortals, a society should have mechanisms for replacing those who die out. Social systems are thus required to address the problems of recruitment and replacement.

Once membership is assured, it is imperative that the system puts in mechanisms for keeping members oriented to the system. To quote Parsons, there ‘is the need to secure adequate participation of a sufficient proportion of these actors in the social system, that is, to motivate them adequately to the performances which may be necessary if the social system in question is to persist or develop’. The system should motivate people to become a part of itself, and continue to remain active. Members must also be motivated to act positively to further the cause of the system, fulfilling its expectations. If they become frustrated and engage in disruptive behaviour, the system might collapse, or at least become weak. In other words, it is important to ensure that there exist among a system’s members a considerable degree of conformity to the goals of the organization, and commitment to fulfilling role expectations.

This would require ‘a minimum of control over potentially disruptive behaviour’, and a system of gratification for actors to keep them motivated.

This aspect has been criticized by some scholars on the grounds that the structural functional theory is status quoist. This is, in fact, a misconception. What the theory suggests is that a system would collapse if there is no mechanism of control, or if there is no gratification of the needs of its individual members. There is a hidden message stating that if anyone wishes to engineer a demolition of a particular social system, it should attack its gratification system or weaken its control mechanisms. The theory is neutral in this regard, and is capable of explaining the continuance of a system or its downfall. Criminology, for example, will qualify as a science only when it can be used not only by those responsible for maintaining law and order, but also by criminals who want to dodge the system and threaten the populace. Another prerequisite, then, is the proper socialization of the people, so that as actors they can play their roles according to prescribed norms.

Institutionalization of norms within the system is another functional prerequisite. Here, norms mean ways of doing things. Institutionalization is a process through which certain ways of doing things in a given social system find ready acceptance by a large number of its members. Not only are these accepted, but they are also internalized by members as part of their personality system. Norms carry sanctions—rewards and punishments, or systems of gratification and deprivation. Those who follow norms—the institutionalized ways of doing things—are rewarded in a situation of interaction; and those who do not are made to suffer punishment (monetary or physical), withdrawal from interaction (ostracism), adverse commentary, etc. A situation of interaction involves the processes of gratification and deprivation. Thus, norms constitute an important part of the culture of the social system. In fact, it is culture that provides a social system with a distinct identity. And it is culture, that is distinctively human.

There is another prerequisite for the proper functioning of a social system, namely, the maintenance of cultural norms. In terms of structure, a family as a social system is the same in all societies; however, what makes an Indian family different from, say, an American family—or within India, a Hindu family from a Muslim family—is the wider culture within which the family functions. A social system has to be compatible with the culture in which it operates. But when it cuts off from mainstream culture and creates its own world by insulating members from the influence of the culture of the wider society, it becomes a deviant or a secessionist group. A gang of dacoits is an example of a deviant social system operating within its own ‘sub-culture’ and posing a threat to the wider society; an example of a secessionist group is that of agitators for Khalistan, who wanted to secede from India and create their own Khalsa land. Such groups face the continual challenge of being wiped out or liquidated by powerful forces of society; however, if the secessionists succeed in their venture, they create an independent society of their own by drawing new boundary lines.

Every system develops a mechanism of social control. However, this is not to suggest that social systems do not provide space for alternatives. Systems allow for orderly change, and all systems gradually move away from the original blueprint. The best simile is the individual himself as a biological being. He grows from a newborn to an adolescent and then an adult, and finally, a senior citizen. Each phase of this change radically alters personality and appearance, and yet these changes occur within the original skeletal frame and without any loss in identity. Structural–functional analysis also focuses on the changes occurring in the system.

Cultural patterns consist of belief systems, systems of expressive symbolism, and systems of value-orientation.

Another prerequisite is the institutional integration of action elements. In order for a system to function, it is necessary that its various are well integrated, and no conflicting demands are made by various sub-systems. Conflicting demands may create confusion and disrupt the smooth functioning of the system. As we have noted earlier, integration implies interconnectedness. Any action in any part of the system has ramifications in every other part.

It is only by virtue of internalization of institutionalized values that a genuine motivational integration of behaviour in the social structure takes place, that the ‘deeper’ layers of motivation become harnessed to the fulfilment of role expectations. It is only when this has taken place to a high degree that it is possible to say that a social system is highly integrated, and that the interest of the collectivity and the private interests of its constituent members can be said to approach coincidence (Parsons, 1952: 42).1

However, it must be said that total integration is an ideal position. In reality, different systems exhibit different degrees of integration, ranging from high to very low.

Parsons has classified institutions into three types as follows (ibid.: 58):

- Relational institutions (defining reciprocal role-expectations independent of interest content).

- Regulative institutions (defining the limits of the legitimacy of ‘private’ interest-pursuit with respect to goals and means).

- Instrumental (integration of private goals with common values, and definition of legitimate means).

- Expressive (regulating permissible expressive actions, situations, persons, occasions, and canons of taste).

- Moral (defining permissible areas of moral responsibility to personal code or sub-collectivity).

- Cultural institutions (defining obligations to the acceptance of culture patterns—converting private acceptance into institutionalized commitment).

- Cognitive beliefs

- Systems of expressive symbols

- Private moral obligations.

Understood in this sense, institutionalization is the process of integration and interpretation of social and cultural systems.

Handling Functional Problems: The Agil Model

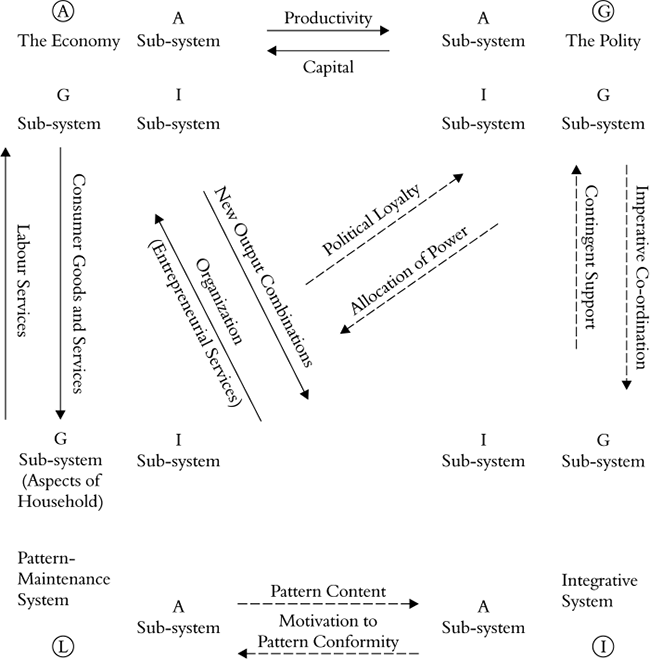

Consolidating all the ideas mentioned above, Parsons talks of four functional problems or requisites, namely, (i) Adaptation, (ii) Goal attainment, (iii) Integration, and (iv) Latency 2 or Pattern maintenance—abbreviated as the AGIL paradigm.

Parsons subscribes to the view that the action generated within any given social system is in part directed toward its external situation and in part toward its internal situation …. The external–internal dichotomy is one axis. Consistent with his earlier means-ends formulation, he also sees some activity as instrumental in that its product represents the means to a goal, and not the goal itself, whereas the other is consummatory in that the product per se of the activity (or the activity itself) represents goal attainment. The instrumentalconsummatory dichotomy is the second axis, which upon intersection with the external–internal axis describes four general areas of activity … (Loomis and Loomis, 1963: 315).3

This is shown in Figure 8.1

Figure 8.1 Parsons’ AGIL Representation

This model was initially proposed for society as a social system. However, since other groups within society are also social systems, the model is equally applicable to them. To quote Parsons, ‘A committee, a work group, or even a family clearly do not constitute in the usual sense, societies. But equally clearly they are, for purposes of sociological theory, social systems’ (1954: 70). Activities occurring in any social system will contribute to each of the four cells in Table 8.1, although its emphasis may lie in one of four cells to justify its primary placement in that cell. Thus, family as a group falls primarily in the L cell,but also contains all four patterns. As Parsons explicates:

… the differentiation of familial roles by generation is a special case of the external–internal differentiation in its hierarchical version, with the parental generation performing the external roles; differentiation by sex is a special case of the instrumental-consummatory line of differentiation … the masculine role performs … primarily instrumental functions … the feminine … primarily the consummatory ... (1959: 9–10).

The four cells are occupied by four functional sub-systems. Cell A represents the Economy dimension; Polity belongs to Cell G, where organizations oriented towards the generation and allocation of power—most organs of the government, even banking and corporate aspects of some systems—are placed. Cell I consists of those organizations and sub-systems that perform mainly an integrative function, such as courts (because they are involved in the institutionalization of norms), which are also involved in the task of minimizing conflict, and health institutions (which act to return the sick to a healthy and normal status). Cell L includes those groupings that contribute to pattern maintenance or tension management, such as temples, churches and mosques, schools, family, and kinship groups.

As stated earlier, such placement is only analytical. Various groups or sub-systems contribute to the functional imperatives of sub-systems in cells other than those in which they are placed. Moreover, a functioning social system implies boundary interchanges. Thus, none of these cells, or the sub-systems within each of them, is a closed system. What happens within each sub-system is affected not only by what happens within that sub-system, but also by what happens elsewhere in the total social system. Actions in the field of polity influences economy and occurrences in economy influence the polity. The system should motivate people to join it and continue to remain active. People should also be motivated to act positively to further the cause of the system, thereby fulfilling its expectations. If they get frustrated and engage in disruptive behaviour, the system might collapse; or at least be weakened. In other words, it is important to ensure that its members conform to the goals of the organization and remain committed to fulfilling role expectations. The system has mechanisms to promote commitment and ensure conformity. Maintaining law and order is a requisite of all systems; those that fail are the ones that face dissolution.

When the economy is in recession, it significantly affects the functioning of the government. If elections take place at such a time, their outcome is also affected. Similarly, the outcome of elections reflects on the Sensex. Rising religious fundamentalism in a multi-religious society poses a threat to the integration of that society by creating conditions conducive to communal violence, terrorist activities, and even cross-border atrocities.

Analytically separable sub-systems of society, or even a social organization at the level of a sub-system, are thus closely interrelated. This can be diagrammatically shown in Figure 8.2.

Figure 8.2 Interrelations Between Sub-systems of a Society

Talcott Parsons and Neil J. Smelser4 demonstrated in their book Economy and Society the interface between economy and other sub-systems of society. Figure 8.3 is very helpful in understanding the linkages between various sub-systems. It focuses particularly on linkages from the vantage point of economy as a primary sub-system:

‘Since a society is a social system, it has the four problems of pattern maintenance and tension management, adaptation, goal attainment, and integration’ (Johnson, 1960: 57). The functional sub-systems are, however, abstract.

Figure 8.3 Boundary Interchanges between the Primary Sub-systems of a Society

For example, the ’economy’ is the functional subsystem that deals with the adaptive problem of the society. But this ‘economy’ is not composed of a definite number of groups .... It is not, for example, made up of business firms exclusively; for if we define the economy as the subsystem that produces goods and services … then obviously families also produce goods and services and are thus part of the economy. Moreover, business firms are not exclusively economic organizations, for they also make contributions to the solution of the other three ‘problems’ of society .… The economy is [therefore] the adaptive subsystem of the society in the sense that it produces goods and services that can be used for a wide variety of purposes—purposes of the government, of families, of business organizations, and of groups of other types (ibid.).

The actual social sub-systems are classified in terms of their main contribution to one of the four functional problems, and are called primary.

It must be noted that this scheme is operative both at the system and the sub-system level. Each sub-system in any of the four cells also has AGIL functions, in the absence of which the system will fail (or cease) to operate.

Functional sub-systems can be distinguished from structural ones. While functional sub-systems are not composed of concrete groups, a structural sub-system is. Family, clans, and neighbourhoods are all examples of structural sub-systems. These structures are characterized by four elements: sub-groups, statuses with various accompanying roles, regulative norms, and cultural values. These structures differ in terms of their size and number of subgroups, the overlapping of sub-groups, the number of occupants in different status positions, and the distribution of facilities and rewards among types of sub-groups and various status occupants.

This scheme also insists that sub-systems within a system should not be treated as closed systems. If such insular systems survive, they become self-sufficient in themselves and thus secede from the parent system. The creation of the new nation of Pakistan after the partition in 1947 can be regarded as the result of such insulation. Again, the creation of Bangladesh from Pakistan was a clear case of insulation, made possible through geographical separation. The formation of new castes from the original four varnas is yet another example of the same process. However, it must be admitted that there can never be total insulation. Every society keeps its apertures open to let in external flows, but guards them well so as not to be overtaken by them. It is on the operation of the twin mechanisms of insulation and apertures (see Atal, 1973) that the integration of a group and its distinct identity depends. In concrete situations, integration is always a matter of degree.

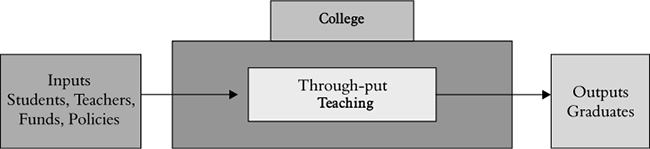

Input–output Model

The linkage between different sub-systems can also be shown through an input–output model (see Figure 8.4). Any sub-system receives inputs from the wider social system, which are then processed within the sub-system. The process is technically known as throughput, and is delivered to the wider social system as outputs.

Take the example of a college as a sub-system of the education system of society, the education system itself being a sub-system of the wider social system. The college has a faculty and administrative staff recruited from the available manpower and gets its paraphernalia produced by other sectors; its student clientele—the key input—is produced by lower-level schools as an output. A fixed number of years of schooling at the college transforms these school-leavers into graduates, who leave the system as outputs. The courses offered within the college, standards of teaching and examinations, and the overall management of the system are conditioned by the external environment. The courses are designed by the university to which the college is affiliated, and student preferences for courses are governed by the market demand for skills, or general preference pattern of the youth. Similarly, teaching within the college depends on the quality of teaching staff the college is able to attract, and the level of job satisfaction it provides in terms of salary and perks, compared to other professions. In all such matters, the sub-system of the college is influenced by occurrences in the wider social system in varied fields such as economy, polity, and academics. Sociological investigation of any social structure—society as a whole, any local community (village or city, or even a mohalla), any organization (a factory, a school, or a club)—requires such an orientation to gain a meaningful understanding of the phenomena.

Functional Analysis

The focus in structural analysis is on the elements of patterning that are relatively constant. This is not to deny the significance of change. For example, the structure of the Indian polity is well defined in our constitution. The division between the executive, the judiciary, and legislative bodies, fundamental rights, and the party system are constant. But within these constants, Indian polity has changed while functioning for over six decades. From a one-party dominance system of governance, it entered into an era of coalition without changing the constitution. Structural analysts pay particular attention to equilibrium. Any system that might deviate from its path has to return to its normal course. There are in-built mechanisms in every social system to take care of deviations and help the system return to normality.

This is similar to the process of homeostasis found in living beings. Through this process, the system either comes to terms with the exigencies imposed by a changing environment, or undergoes structural change; in case of failure, it experiences a dissolution of its boundary-maintaining mechanism. A human body, for example, undergoes this process when it falls ill for some time and then returns to normalcy. There is a popular saying, ‘if you treat a cold, you will be better within seven days; if you don’t, it will take a week’. This is indeed a reference to homeostasis, to inner forces that bring back the body back to normalcy.

Functional reference relates to the dynamic dimension of social structure. Beginning with the relative givenness of the structure—the constants—sociological analysis proceeds to examine the behaviour of the structure in exigencies caused by factors external to that social structure. The focus of the functional analyst, on the other hand, is on the consequences of actions of elements of the social structure.

The Concept of Function

Robert Merton—student and later a colleague of Talcott Parsons—took this line of theoretical formulation forward. Proposing his paradigm of functional analysis, Merton said, ‘Functional analysis is at once the most promising and possibly the least codified of contemporary orientations to problems of sociological interpretation’ (1957: 19). This has happened because ‘Too often, a single term has been used to symbolize different concepts, just as the same concept has been symbolized by different terms.’ In sociological literature, terms like use, utility, purpose, motive, intention, aim, and consequences have been used almost as synonyms of function. Similarly, the term function has been used to denote at least five different concepts:

- Used for some public gathering or festive occasion.

- As equivalent to occupation.

- Used to refer to the activities assigned to incumbents of a social status, and more particularly to the occupant of an office or political position. This is why an official is called a functionary.

- The word has ‘its most precise significance in mathematics, where it refers to a variable considered in relation to one or more other variables in terms of which it may be expressed or on the value of which its own value depends. This conception, in a more extended (and often more imprecise) sense, is expressed by such phrases as functional interdependence and functional relations, so often adopted by social scientists.’

- ‘Stemming in part from the native mathematical sense of the term, this usage is more often explicitly adopted from the biological sciences, where the term function is understood to refer to “vital or organic processes considered in respects in which they contribute to the maintenance of the organism”.’

Merton also reviewed the three interconnected postulates commonly adopted by functional analysts. These postulates hold:

- ‘that standardized social activities or cultural items are functional for the entire social or cultural system’—Postulate of the Functional Unity of Society;

- ‘that all such social and cultural items fulfil sociological functions’—Postulate of Universal Functionalism; and

- ‘that these items are consequently indispensable’—Postulate of Indispensability.

Merton regarded these as overstatements. An examination of the first postulate led him to conclude that ‘one cannot assume full integration of all societies’. Integration is a matter of degree. One can talk of highly integrated or highly disintegrated societies, but there is no empirical evidence of a totally integrated one. In employing functional analysis, one will have to look to those specified social units that are served by given social functions, and cultural items should be seen to have multiple consequences, not all of them functional. Moreover, consequences may be different for different groups, and therefore, there is a need to work out the net balance of consequences.

Commenting on the second prevalent postulate, According to Merton, ‘Although any item of culture or social structure may have functions, it is premature to hold unequivocally that every such item must be functional’. This postulate gained currency when evolutionists were talking of survivals, which have lost their utility and were treated as part of the past; functional analysts insisted on attributing a function to each article of culture, refuting the theory of survivals.

The same train of thought led to the postulate of indispensability of all cultural items or practices. Malinowski, for example, argued that ‘… in every type of civilization, every custom, material object, idea and belief fulfils some vital function, has some task to accomplish, represents an indispensable part within a working whole’ (1926a: 132). The indispensability postulate connotes two propositions:

- the indispensability of certain functions; and

- the indispensability of existing social institutions or cultural forms.

Both meanings rule out the possibility of functional alternatives, equivalents, or substitutes. Merton refutes the charge that functional analysis is conservative. He does this by challenging existing postulates and suggesting an objective framework—a paradigm—that takes note not only of function but also of dysfunction, and applying this dichotomy to functions that are both manifest and latent. Functional analysis is thus neither conservative nor radical. In fact, it helps to analyse the change that occurs in a social and cultural system. It is wrong to regard functionalism as ‘anti-change’ and thus supportive of the ‘status quo’. Since anthropologists studied preliterate societies that were slow-changing, and thus appeared tradition-bound, their attention was drawn to this aspect of continuity and their theoretical formulation reflected this feature, giving the impression that they resisted change. Brilliant analyses of social change attempted by sociologists using the structural–functional frame of reference are, in this regard, a strong rebuttal to the allegation.

Manifest and Latent Functions

The action framework, as stated earlier, suggests that an action is taken with a view to achieving a certain goal. And to attain the goal, an actor is required to adopt culturally approved means.

When the stated intention—or motivation—results in the attainment of the desired goal (consequence), it is a manifest function of the action. ‘Manifest functions are those objective consequences contributing to the adjustment or adaptation of the system which are intended and recognized by the participants in the system’ (Merton, 1957: 51).

However, sometimes the consequences of an action are the ones that were neither intended nor recognized. Such consequences are termed latent functions.

This formulation helps us avoid confusing motives with functions. It is also a reminder of the fact that motive and function vary independently. This distinction (i) ‘clarifies the analysis of seemingly irrational social patterns’; (ii) ‘directs attention to theoretically fruitful fields of inquiry’; (iii) ‘precludes the substitution of naïve moral judgements for sociological analysis’; and (iv) directs attention towards the discovery of latent functions to further enrich sociological theory.

Functions and Dysfunctions

Functions, whether manifest or latent, are seen as consequences of any partial structure, be it a sub-group, a status-role combine, a social norm, or a cultural value or practice. These consequences can be either good or disastrous for the system. There is also a possibility that the consequences may be neutral, in the sense that they will neither fulfil any social need (by contributing to the smooth working of the system) nor adversely affect the system. Consequences of any sub-system that contributes to the fulfilment of one or more needs of a social system are generally called functions—in a positive sense. Since the term function is employed for all types of consequences, positive functions are often termed eufunctions. Functions that hinder the fulfilment of one or more needs of the system and are thus disruptive or negative are called dysfunctions. Those that are neutral in character are referred to as non-functions.

Since manifest functions are those that correspond with stated intentions that are socially recognized, they are all eufunctions. It is mainly latent functions that can be either of the three. Thus, not all latent functions are dysfunctional.

We can present the classification of functions in the manner shown in Figure 8.5.

Figure 8.5 Classification of Functions

There is yet another aspect, not, however, made explicit by Merton, which relates to intentions. Like functions, intentions too can be both manifest and latent. In such circumstances, when a consequence matches a latent intention, it is similar to manifest function, although it is placed in the category of latent functions. Such a consequence can also be positive or negative. An unstated intention such as this is referred to as hidden agenda. Policy makers and planners make explicit their goals in politically correct language, but might also simultaneously pursue another agenda that hinders the attainment of the stated goal and leads to latent dysfunctions. When Community Development Programmes were launched in India in the 1950s, their stated aim was to uplift rural India by removing poverty, improving agricultural practices, promoting literacy, and ensuring better health. An assessment and evaluation of this massive programme found that the rich had become richer while the poor remained poor in the villages. The menace of poverty has still not been eliminated, despite more than six decades of development focusing mainly on rural India. Critics allege that it has been the hidden agenda of the elite and powerful to keep the poor poor; and thus it is not a failure of planning, as things worked according to the hidden agenda and succeeded in attaining the goal of benefiting the few and impoverishing the majority.

It is important to emphasize that latent functions are not always dysfunctional. Functional theory suggests that latent functions can be eufunctional, dysfunctional, or even non-functional. Take the example of the policy of ‘reservations’ enacted by the Indian Constitution. The intention of the constitution-makers was to pay special attention to relatively oppressed groups by listing them in two different schedules—one for the lower/ depressed castes (now widely known as Dalit) and the other for tribal groups—in order to improve their overall living conditions and social position and erase the caste distinctions that perpetuated untouchability. Besides special developmental programmes for these communities and the areas inhabited by them, provisions were also made to ‘reserve’ seats for them in educational institutions, government jobs, and in state and central legislative bodies. As a consequence of this action, the condition of these groups has improved over the years, and there is a visible presence of people belonging to these categories in the public domain, some occupying high positions in ministerial, gubernatorial, and other high-ranking assignments. These can be regarded as manifest functions. However, the policy of reservations has been under constant attack on several counts. It is argued that ‘positive discrimination’ in favour of SCs and STs has resulted in ‘negative discrimination’ against those who do not belong to such groups, but who deserve to be rewarded on the basis of merit. It is also said that this practice has led to the development of a ‘vested interest’ in these groups to remain backward. Even the Supreme Court has hinted that the creamy layer among these groups, which has emerged as a consequence of these measures, is now pocketing all the benefits, which do not reach the really deserving. Rather than paving the way for the eradication of caste, these measures have fostered caste solidarities and created rifts between the so-called upper castes and Dalits—a trend that is dysfunctional as it engenders animosity rather than amity. It is such a combination of eufunctions and dysfunctions that a net balance of consequences needs to be computed.

Functional Equivalents or Alternatives

Functional theory insists that no mechanism is indispensable. The same function can be obtained through some other mechanism. These other mechanisms are alternatives or functional equivalents.Take marriage, for example. Marriage is an institution that gives social recognition to mating on a regular basis, and defines certain obligations for the parties involved. In the same society, different groups can have different ways to conduct a marriage. Even the same group can choose from various alternatives. A Hindu, for example, might get married in an elaborate Hindu ceremony, or go to an Arya Samaj temple and tie the knot in Vedic tradition, or simply go to a temple and exchange garlands with the deity and priest as witnesses (so often portrayed in films), or have a court marriage. These are functional equivalents of a marriage ceremony. A widow remarriage, likewise, can either be elaborate or be a simple ritual of ‘offering a sari’ and paying a monetary tribute to the family of the widow’s late husband.

Giving gifts as dowry has been an old practice in India. The original intention was to give the bride a ‘parting gift’; it was different from the ‘bride price’ prevalent in many tribal societies, where the price—value—is paid by the aspiring bridegroom as compensation for taking away a member of the family. Dowry was not meant as compensation, as the party losing a member was not at the receiving end. Dowry served the function of maintaining good relations and enhancing the prestige of the bride. But with passing times, it became dysfunctional, in the sense that instead of accepting it as a social gesture, the bridegroom’s family came to regard it as their right, and began making unreasonable demands. The demands continued to be made even after a few years of marriage, with non-compliance leading to wife-beating, torture, and quite often dowry deaths—brides committing suicide or being killed by the husband and the in-laws. A cultural tradition that had eufunctions has now degenerated into an ugly practice, and become dysfunctional for the family.

These instances—of course, many more can be added from our day-to-day experience— also hint at the changes that occur in a social system, many of which are associated with the consequences of individual and group performance, and the conflicting demand structures of various status positions simultaneously held by single individuals.

Functional analysis is thus helpful in analysing social deviation and change.