CHAPTER 11

Marriage, Family, and Kinship in India

India is a multicultural society with several tribal groups and different religions. Such a demographic composition makes the institution of the family a very complex phenomenon. Families in India are both patriarchal (those in which authority flows from the father) and matriarchal (those in which authority flows from the mother). These determine rules regarding lineage and descent, residence, inheritance, and incest. Differences also exist with regard to the composition of the family.

In most treatments of Indian society, what is described as the Indian family is usually a portrayal of the ‘ideal Hindu’ family. Apart from the fact that ‘real’ Hindu families in modern India do not correspond to the ‘ideal’, such portrayals fail to describe the institutions of family and marriage among other groups residing in India—the Christians, the Parsees, the Muslims, and the more than 700 tribal groups residing in different corners of the Indian subcontinent.

In this chapter, we shall briefly refer to the matrilineal as well as patrilineal families relative to India.

Matrilineal Families In India

Matrilineal families are found in South India and in the Northeast. The Khasis of Jayantia Hills and the Garos are the best-known examples of matrilocal and matrilineal societies. The Nayars of Malabar in the state of Kerala are famous both for the practice of polyandry—which is now on the decline—and matriliny. The tribe of Kadars of Cochin is also matriarchal.

We shall briefly describe the family system among the Khasis, Garos, and the Nayars.

The Khasis

The Khasi family is known as Iing. A typical Iing consists of a mother, her husband, her unmarried sons, her married daughters, their husbands and children. In matrilineal families such as the Khasi, it is the husbands who come to stay with their wives. And the male children leave upon their marriage to stay in the houses of their wives. This pattern is called matrilocal residence. The males contribute to the family income and give their earnings to their mothers, or to their sisters, and not to their own children, who belong to a different Iing. The youngest daughter is the heiress, following the principle of ultimo geniture. She acts as the priestess of the family to lead all family rituals, including the post-death ceremonies, which include cremation of the dead and interring of the bones into the common sepulchre—a family tomb. Elder daughters of the family are despatched to new places after their marriage. These new houses are usually in the same compound. Only the youngest daughter lives in the mother’s Iing as custodian of the house, and is responsible for family worship. Thus, she receives a larger share in the family property. The extended group of interconnected Iings is called a kur—a clan.

The Garo

The Garos are also matrilocal. The extended family is called machong. A man leaves his machong after marriage to live in the machong of his wife. He becomes a member of her machong, and also adopts the name of her clan. Likewise, the children of his sister live in his mother’s machong, and belong to her clan. Garo also follow the principle of ultimogeniture, through which the youngest daughter becomes the heiress-apparent. She is called nokna-dona. Her husband is called nokrom. Husbands of other daughters are called chowari. While any of the daughters can be nominated a nokna-dona, it is usually the youngest daughter who is chosen to inherit the family property. Other daughters move out to reside in separate households within the same compound, with their husbands. The preferred form of marriage is for a nokna to marry her Father’s Sister’s Son (FaSiSo). In the event of the death of nokna’s father, her mother is free to marry. But if this marriage takes place, then there remains the possibility of the mother producing yet another daughter. In that case, the present nokna will have to surrender her rights to the younger sister, and move out of her mother’s house, like her elder sisters, to give way to her younger sister, who then becomes the nokna-dona. To avoid such a crisis in the management of property, her husband—the nokrom—is required to marry his Wife’s Mother (WiMo). Usually this woman is the widow of the boy’s FaBr—this suggests that among the Garo, a person can marry his parallel cousin (FaBrDa) and is thus obliged to marry his WiMo upon the latter getting widowed. Thus, in such situations, a person becomes the husband of both the mother and the daughter at the same time.

The Nayars

The Khasis and the Garos of the Northeast are tribal people. Many of them have adopted Christianity, but the British allowed them to practice customary law regarding the matrilineal inheritance of property and descent. The Nayars of Kerala are Hindus. They are known to have allowed the practice of polyandry. It is said that matriarchy allows the possibility of polyandry in the same way that patriarchy is associated with polygyny.

The matrilocal residence of Nayars is called taravad. Unlike the Khasis and the Garos, taravad did not allow the daughters’ husbands to live with them. The husbands were allowed to visit their wives at night after dinner, and leave them in the morning before break-fast. A taravad consists of the female members and their brothers and children. The family authority, however, rests with the eldest male member of the household, who is called a karnavar. He is allowed to bring in his wife to stay with him, but not his children, who stay with his mother’s taravad.

Marriage among the Nayars was always a loose arrangement. There are two forms of marriage among them. One is called Sambandham and the other, Tali-kettu Kalyanam. A Nayar woman could have a Sambandham not only with a member of her own caste, but also with males of higher castes, like Brahmins and Kshatriyas. Such a union was formalized with a gift of clothes by the bridegroom. However, such a marriage was never binding, and the woman was free to marry anyone else without any formal dissolution of the Sambandham. The husband was not obliged to provide maintenance to his divorced wife.

Tali-kettu Kalyanam is another form of marriage that is held before a girl attains puberty. Tali is a small piece of gold which is tied by the suitor round the neck of the girl. A boy belonging to the matriclan—called enangar—is chosen for this ceremony. His party is received by the girl’s taravad. The girl’s brother washes the feet of the tali-tier, after which the tali is tied. The taravad hosts a grand feast and the ceremony continues for four days. On the fourth day, the boy and the girl are seated in a hall or a compound where, in the presence of the village people, the girl tears off the new dress of the bridegroom. This signifies the end of the union between the two. However, the girl observes a 15-day pollution when her tali-tier dies. But after the Tali-kettu Kalyanam, the girl is allowed to live a free life with regard to sex. She could have several visiting husbands. This is why the Nayar family was called polyandrous.

Recent studies have suggested several changes in the taravad structure. Due to the trends of modernization and industrialization, there is a greater degree of mobility, and so one finds virilocal wives (wives residing with their husbands) and uxorilocal husbands (husbands coming to live with their wives). The factors responsible for virilocal residence are: employment in a town, inability of the husband to visit his wife’s house in a different place, poor health of the mother or sister, making it obligatory for the man to stay in his taravad and ask his wife to join him, etc. Similarly, uxorilocal residence is facilitated by the following factors: the wife’s household (called Veedu—a smaller unit within the taravad) not having an elder man to run the affairs, or when a male kin of the wife leaves for an urban area for employment. As a result of these changes, there are now instances of children taking the name of their father and avoiding the taravad name. Families are now a mix of matriliny and patriliny.

Leela Dube (1923–2012) (Courtesy: © Sanket Atal)

The Mophlas present a unique case—a Muslim community found both in Kerala and in the Lakshadweep and Minicoy islands. These converts from Hinduism have carried matriliny into Islam. Leela Dube and two of her students have studied them and produced monographs on this community.

This is how Leela Dube describes the matrilineal unit in the island of Kalpeni.

A taravad is a group of individuals of both sexes who can trace their descent by a common genealogy from an ancestress in the unbroken female line. The depth of this matrilineage ranges from three to six or even more generations. Every taravad has a name which is used by its members as a prefix to their personal names. Birth in a taravad gives a member the right to a share in the taravad property which consists mainly of land, trees, boats, and buildings.

This right passes through female members; a male member has only usufructuary1 rights over the taravad property (Dube, 1969: 28–29).

Taravad is an exogamous unit, and may consist of either a single domestic group (called Pira) or several domestic groups. Matrilineally linked, two or more taravads constitute a Kudumbam.

Since the people of Kalpeni are Muslims, they follow both traditional matrilineal rules and the Islamic law of inheritance (Sharia). It may be noted that Islamic law says that the daughter’s share should be half of a son’s share. The wives get one-eighth of the whole property, and one-fourth if the man has no children. Due to the combination of matriliny with Islam, the property is divided into two types: Velliarcha Swoth or Friday property and Thingalarcha Swoth or Monday property. The former is passed on matrilineally, and the latter according to Islamic law.

Monday property (Thingalarcha Swoth) is mainly acquired when a man buys, with his personal earnings, some property in his own name, or when a man or a woman or a group of siblings inherit some property through the Sharia, or when a man, as the sole survivor, is the only effective claimant to the property in possession of his matrilineal group (Dube, 1969: 36).

The Patrilineal Families With Special Reference To The Hindu Family

Even among the Hindus, wide variations are found in the institution of family in different regions. Professor Irawati Karve was the first sociologist to contribute to our understanding of the structure of Indian society by publishing in 1953 a monumental work on Kinship Organization in India.2 Karve brought out the differences in the social system of northern India and southern India. She was perhaps the first to hint at the practice of village and regional exogamy in northern India, and elaborated the concept of Seem Seem na Bhaichara, which is associated with Khap exogamy. We have explained this in the previous chapter.

Irawati Karve (1905–1970) (Courtesy: © Yogesh Atal)

The typology of the family discussed in Chapter 9 is relevant here. Due to the multi-cultural character of Indian society, examples of various types of family are available in India. Apart from monogamy, the commonest form of marriage throughout the world, irrespective of religion or nationality, examples of polygamy—both polygyny and polyandry—abound in India.

Polygynous families are found not only among Muslims, but also amongst the Hindus, particularly in parts of North India, where widows are remarried to the brothers of their husbands. This practice is called Levirate.3 However, such a union becomes polygynous only when the man marrying the widow is already married. But when this marriage takes place between the widow and the bachelor brother of the dead man, it is only an instance of levirate. Instances of the husband marrying his wife’s sister are also found, either as a second wife or after the death of his first wife. This practice is called Sororate. It becomes a case of sororal polygyny only when the man does not wait for the death of his wife to marry her younger sister; in such cases, both sisters share a common husband.

Polyandry is the opposite of polygyny. Families where a woman is married to several husbands at the same time are called polyandrous. The famous example of a polyandrous family in India is that of the Pandavas—the heroes of the Mahabharat—who had Draupadi as a common wife. Like the Pandavas, the husbands can be brothers, making such a marriage fraternal (or adelphic) polyandry. Such form of marriage is still to be found— although it is giving way to monogamy—amongst the Khasas of the Jaunpur–Bawar area in the state of Uttarakhand and the Todas of the Nilgiri Hills. The Nayars of Kerala also practised polyandry; it is now on the wane among them. Polyandry is also found among the Tiyan, the Kota, the Iravan, and the Ladakhi Bota. The Toda and the Nayar also allow non-fraternal polyandry, in which the husbands of the same woman do not have to be related. The wife spends her time in turn with each husband. Among the Todas, where non-fraternal polyandry occurs, the paternity of a child is determined socially. Irrespective of who the biological father of the child is, any of the husbands may accept the responsibility of siring the child. To announce fatherhood in Toda society, the sociological father retires with his pregnant wife in the nearby jungle where, in the presence of his tribesmen, he performs a customary bow and arrow ceremony. Such a practice is needed because the Toda have a mix of matriarchal and patriarchal families—residence being maternal and inheritance paternal. This practice—of the husband leading the life of an invalid along with his pregnant wife—is technically called couvade.

There are references in the ancient literature of the Hindus to permission being granted to a woman to have an extra-marital relationship with a person in order to beget a child and continue the family line. This practice was given the name Niyoga (appointment).4 Under Niyoga, ‘the marital relations between the two were temporary and restricted. They lasted till the signs of pregnancy were visible or at the most … till two children were born’ (Kapadia, 1959: 60). No privileged intimacy existed between the partners and

[C]onjugal rights were sanctioned only to secure an heir to the deceased. That this conjugal relation was allowed only for the continuation of the line is confirmed by the fact that a widow who was either barren, past child-bearing, or very aged was not allowed to resort to niyoga. Likewise, a person who was sickly was not commissioned to beget in niyoga (ibid.).

A famous instance is that of Bhishma, who was approached by his stepmother to marry the widows of Vichitravirya who had died childless, thus creating a crisis vis-à-vis the continuation of the line of Shantanu (father of Bhishma and Vichitravirya). While Bhishma found nothing wrong with his mother asking him to marry his younger brother’s widows, he did not comply because of his vow to remain celibate. As an alternative, he sought the services of the great sage Vyas to beget children by the widows of his stepbrother. Had Bhishma agreed to the proposal and married his brother’s widows, it would have been an instance of senior levirate. The alternative opted for was a case of Niyoga.

Some groups also follow a pattern of preferred marriages. For example, in the South, marriage between the mother’s brother (Mama) and his elder sister’s daughter (Bhanji) is a preferred form. Similarly, marriages are also preferred with the Mother’s Brother’s Daughter (MoBrDa: Mameri Bahin) and the Father’s Sister’s Daughter (FaSiDa: Fuferi Bahin), or with the Mother’s Brother’s Son (MoBrSo) and the Father’s Sister’ Son (FaSiSo). Both are instances of cross-cousin marriages.

In the Hindu South and amongst Christians and several tribal groups of India, cross-cousin marriages are generally preferred, but amongst the Hindus of North India, these are tabooed and regarded as incest. The Muslims allow even parallel cousin marriages, along with other preferred marriages such as cross-cousin marriages and marriages between MoBr and SiDa.

Writing about the southern zone, Irawati Karve has enumerated the following taboos (Karve, 1965: 224):

- A man can marry his elder sister’s daughter but not his younger sister’s daughter. The Brahmins are, however, an exception to this rule.

- Widow remarriage is allowed (except amongst Brahmins), but not levirate. A widow cannot marry her husband’s brother. This taboo is observed in Tamil Nadu, Andhra, Karnataka, and Kerala.

- A person is not allowed to marry his Mother’s Sister’s Daughter (MoSiDa).

- The complicated kinship arising in a family owing to maternal-uncle–niece (MoBr with SiDa) marriage and cross-cousin marriage sometimes result in two people being related to each other in more ways than one. There may be one relationship where a marriage would be ordinarily forbidden, while from another angle the relationship may be one in which a marriage usually does take place.

Family in Hindu Scriptures

Hindu scriptures also recognize three functions of the family, namely, reproduction—particularly the importance of a male progeny—performance of rites, and gratification of sexual needs (putra prapti, dharma karya, and rati, respectively). Rati (or Kaam or sex) is called Brahmanand Sahodar (brother of eternal pleasure). Upon the completion of the first Ashrama,5 that of Brahmcharya, the person begins his family life with marriage. The sacred fire kindled at marriage beckons a person to enter domestic life, in which he is expected to perform five great sacrifices called yagna in order to expiate the sins that he would commit as a householder. Symbolically, these sins are committed at the stable (where domestic animals are kept; Pashusthaanam), hearth (Chulli), grinding stone (Peshani), broom (Upaskar), and the water vessel (Udkumbha). The five yagnas are as follows:

- Brahma yagna: This is supposed to be done to pay off the debts to one’s gurus—the debt is called Rishi Rin. This debt is paid off through teaching and studying.

- Pitra yagna: This is done to appease the spirits of the ancestors through offerings of food and water—called Tarpan.

- Dev yagna: This is to propitiate family deities through oblations offered to the sacred fire—Havan.

- Bhoot yagna: Food is offered to alleviate and propitiate wandering spirits to keep them happy and prevent them from harming family members.

- Nri yagna: This is performed by extending hospitality to guests and strangers—also known as Atithi6 Pujanam.

These chores are performed by the family as part of the function of the institution, and the scriptures prescribe them as a route to permanent happiness—Nityanand. The head of the family and his wife are expected to have their meals after performing all the rites honouring the guru, the gods, the ancestors, the family deity, guests/strangers in the home, and the servant (Bhritya). The Hindu tradition, as presented in the sacred texts, teaches humility, respect for other human beings, including the servant, and reminds one of one’s debt to teachers and ancestors. Central to all these activities is the spirit of sacrifice. It is always the most precious things that are offered to the fire in the havan—clarified butter (ghee) is symbolic of this. In this sense, Hindus regard the house as a temple of tradition, and a place where its members practice the three shastras—Dharmshastra, Arthshastra, and the Kaamshastra (religion, economics, and the science of love). As many as 40 different rites de passage, according to grihya sutra, are performed in the family, ranging from the foetus-laying ceremony (garbhadhan) through initiation (upnayan), marriage (vivah) and death (antyeshti).

Traditionally, there were 40 important rites associated with the Hindu marriage, beginning with betrothal (vaagdaan) to the entry of the bride in the house (vadhu pravesh). We cannot go into the details of all the rituals here as our interest is on the structural aspects, and not on the ethnographic description of how a Hindu marriage is conducted, with all its cultural nuances.

Hindu society is characterized as a caste society. This means that the society consists of several castes as units, and that the interaction between them has created a system of relationships. It is the caste units in this system that practice endogamy; in other words, a caste system is a system of interaction between endogamous units. The caste is the minimal unit below which endogamy is not practised. A caste, as a living social group, is defined by its endogamous boundary. Caste membership consists only of those families that marry within the group. To say that Hindus are endogamous, or that Indians are endogamous, has no sociological meaning, because in that sense every society is endogamous—the Thais marry Thais, Sri Lankans marry Sri Lankans, and so on. A society becomes a caste society when there is a plurality of castes. It is in this sense that a tribe does not qualify as a caste society despite being endogamous. However, if any tribe has endogamous divisions within it, then it is also, structurally speaking, a caste system. Alternatively, an endogamous tribe can become a caste unit if it resides with similar endogamous groups, as is the case with most Indian tribes who live side by side with Hindu castes, and who have also adopted (or who claim to follow) Hinduism. That is how many groups—either indigenous tribes or migrant hordes from abroad—came within the caste fold and were enumerated as such by census authorities until 1931—after which the government decided to drop the enumeration of caste in censuses. The 1931 census listed people by religion and by castes. The tribals who converted to other religions were separated from the non-converts, who were classed as animists7—and therefore as ‘tribal’.

A caste as an endogamous unit is divided into exogamous units like family, the larger family (also called joint family), lineage and gotra. In most sociological literature, the word gotra is treated as a synonym for clan. But in popular language, people use clan and lineage as synonyms, considering clan as somewhat larger; at times, clan becomes a synonym of the joint family or a kutumb or kunaba. Madan has hinted at this anomaly and prefers to use the word gotra (see Madan, 1962). The word gotra is used by people for different entities, all of them exogamous. People have a general belief that marriage within the same gotra is forbidden, and they abide by it. However, there is no unanimity as to which group constitutes a gotra. The suffix other than the caste name used in a person’s name is generally believed to be that of gotra—and onomastic analysis would suggest that this suffix might either be an eponymous clan, or a local nomenclature, or a family title (such as Majumdar, Bhandari, Khajanchi, Mantri, Chitnis, etc.)

What is gotra? Etymologically, this term is derived from the word gau, meaning cow. A cattle shed was called a gotra. Since people sharing a common cattle shed lived together, they were part of a family and, therefore, exogamous. There are others who believe that it refers to the cattle shed belonging to a particular sage—rishi—regarded as the family guru; all those associated with this sage as disciples or followers, or as direct descendants, used the name of the sage as a suffix to their name. Gotra nomenclature is, thus, a part of the Brahmanical system. This gotra is also called a rishi gotra or arsh (derived from rishi)—eponymous—and is differentiated from laukik gotra (meaning a lower-level formation). The latter is sometimes called got (‘t’ as in Tamil). In different parts of the country, it is known by several names such as Illam, Kul, Mool, Phed, Pangat, That, Kuri, Khel, Benk, Aspat, Avatank.

Rishi Gotra: Hindu mythology tells us that the eight sons of Brahma founded the basic eight gotras after their names. These are Kashyap, Vashishta, Agastya, Bhrigu, Gautam, Bhardwaj (also bracketed with Angira), Atri and Vishwamitra. In addition to these eight, 10 others were founded by some Kshatriyas who converted to Brahmanism. Their descendants continued to add innumerable other gotras as time passed. The interesting point is that gotras are not exclusive to castes belonging to the Brahman Varna. Other castes have also adopted them, either in their quest for a higher status in society or to copy the Brahmanical model.

Population growth over the years has resulted in the breakdown of extended families and the creation of newer units. It is common knowledge that memory begins to falter after five or six generations, and with the departure of elders, the past history of the family also sinks into oblivion. That is why it is hard for people to trace their line of descent from a common ancestor. The rishi gotra is a much broader and older category. However, these gotra names are quite frequently used as suffixes, particularly by people belonging to the castes of the upper Varnas; there is no way, though, of verifying the claim. Having a common eponymous clan does not, therefore, mean an immediate agnatic relationship. People living far apart, and even belonging to different endogamous groups—called Jatis—may have a common rishi gotra name.

Laukik Gotra: Rishi gotra is often ignored while negotiating a marriage, because of the lack of clarity and difficulty in judging the veracity of the claim. It is the laukik gotra—ephemeral, or ‘this-worldly’ clan name—that serves as the reference unit. The nomenclature of these ephemeral gotra names has a varied etymology. For example:

- Some gotra names (used as suffixes) are derived from the name of the original habitat. In Maharashtra, many gotra names end with the word ‘kar’; the prefix to such names is always the name of a habitat such as Padgaonkar, Mangeshkar, Mulgaonkar, etc. Similarly, names such as Phatwaria, Indoria, Singhania, Kedia, etc., indicate that their ancestors came from Phatwar, Indore, Singhan, or Ked, respectively.

Here, it may be interesting to mention that in the south, some groups follow a different pattern where neither the caste nor the gotra name is indicated in the personal name. For example, take the name of the famous Indian sociologist M. N. Srinivas. In this name, the letter M stands for the city of Mysore, from where he hailed, and N represents his father’s name—Narsimhachari. It is the last name—Srinivas—that was his proper name. The American tradition of calling intimates by the first name cannot be followed in this case, because everybody called the professor by his real name—which is the last part of his name rather than the first. Calling him Mysore (the full form of M) would be ridiculous. One can say that in South India, the last name of the person is the first name. As against this, another sociologist from West Bengal, one with a French name—Andre Béteille—can be addressed by his first name, ‘Andre’. However, it must be mentioned that in the South, some people carry their caste names as well—such as Aiyer, Aiyangar, Namboodiripad, etc.

- Some last names denote the family title or the profession of the person. Titles such as Bhandari (store keeper), Khajanchi (treasurer), Paneri (water supplier), Purohit (priest), Deshpande (village priest), or Deshmukh (village head) are used as surnames and are treated as, or understood as, gotras.

- Immigrant groups from abroad were known by the race or ethnic groups of their origin. For example, the Kushans and the Huns were ethnic groups, but these appellations have become gotras (exogamous units) in specific regional contexts. Kashanas and Huns are gotra names among the Gujar in Rajasthan. These names indicate different origins of the people who now claim to belong to a common caste, Gujar. It can be surmised that as ethnic goups, the Kushans and Huns must have been endogamous units in their respective places of origin. But as settlers in India, they must have moved as families or lineages to different parts of the country. Their families continued to be identified by their ethnic name, but because they were lineally related, such small groups became exogamous as gotras—using the local parlance—and were merged within the occupational group of cattle herders who were locally called Gujars, or a variant of this appellation. This is an example of how the name of an endogamous group was used to denote the sub-system of exogamy within the broader category.

It is important to note that although people use either the first and the last names or first, second and last names, the last name is not always the gotra name. People use either the rishi gotra, or the laukik gotra, or the family title as their last name. Then there are those who use their caste names. One also finds that within the same family, different members choose to use different last names. The father may use the caste name, the son may use the rishi gotra or the laukik gotra, or a self-styled pen name. In addition, there are instances of people using the term of address for the Varna category. For example, Brahmin and Kshatriya are varna names, but they remain as terms of reference; they are rarely used as last names. But the terms of address for people of the Brahman and Kshatriya varnas are ‘Sharma’ and ‘Varma’, respectively. These can be used by any person of the Brahmin or Kshatriya varna, irrespective of his or her caste within the varna. In fact, many people who did not originally belong to these castes have begun using these terms. People belonging to the carpenter (Suthar) and barber (Nai) castes often use ‘Sharma’, and some people of the Kayastha caste cluster (Kayasthas are not a single caste; they have castes such as Bhatnagar, Mathur and Srivastava) use ‘Varma’ as their surname. Many have given up caste or gotra names and use only the first two names—the last name being Singh, Prasad, Chandra, etc. In such cases, it is difficult to ascertain the caste of the person. Among the Sikhs, the last name is usually ‘Singh’, but some Sikhs prefer to use their village name as the last name (examples: Pratap Singh Kairon, Prakash Singh Badal). With so many different ways of naming, an analyst has to be very careful in properly designating the category manifested by the last name. Keeping this in mind, the current crisis regarding gotra marriages in the state of Haryana and adjoining regions is not easy to resolve. It should also be said that such anomalies existed even before 1931, when censuses included caste enumeration; and generalizations based on them are not very dependable, particularly given the poor competence of census enumerators in matters of categories related to caste.

Those using different laukik gotras may agree to a marital alliance; it is not uncommon, however, to later discover that the two parties also claim to belong to the same Rishi gotra. This does cause some embarrassment. In such circumstances, precedence is given to the laukik gotra, and the common eponymous clan name is ignored. Exogamy is generally observed at the level of laukik gotra. Prevalent among the Dumals in Orissa are three different exogamous categories called barga (occupational), mitti (territorial) and got (totemic). While contracting a marriage, people make sure that at least one of these is different.

Pravara: Brahmanical literature also refers to pravara. The word means ‘the excellent ones’. Those following the Vedic tradition were required to recite the names of the Pravaras—1, 2, 3, or 5 but not 4—while invoking the god of fire to accept the oblations and transmit them to the gods. In olden times, it was said that a gotra was divided into gana s (sub-gotras), and each gana had a list of its pravaras.

It is said that a scholar named Baudhayan organized the gotras and pravaras into a system of exogamous clans. As an illustration, we take the case of Agastya gotra. Table 11.1 shows the ganas and pravaras of this gotra.

Table 11.1 Agastya Gotra

Gana |

Pravara |

|---|---|

1. Idhamwah |

Agastya, Dardahchyuta, Aidhamwah |

2. Sambhawah |

Agastya, Dardahchyuta, Sambhawah |

3. Somwah |

Agastya, Dardahchyuta, Somwah |

4. Yagyawah |

Agastya, Dardahchyuta, Yagyawah |

5. Agasti |

Agastya, Mahendra, Mayobhuv |

6. Paurnabhas |

Agastya, Paurnabhas, Paran |

7. Himodak |

Agastya, Hemvarchi, Hemodak |

In Jamdagni gotra, each gana had five pravaras, three of which were common, namely, Bhargava, Chyavan and Apnavaan. Similarly, the Gautam gotra had Gautam and Angiras as common pravaras in its ganas; and Bharadwaj gotra had Angiras, Barhaspatya, and Bhardwaj pravaras in all its ganas. However, these distinctions are now almost forgotten by many who write these as gotra names. Instances abound of marriages held between people bearing the same eponymous clan name.

Referring to this prevalent confusion, Madan writes:

Under the influence of Indologists, the sociologists and social anthropologists working in India have regarded the gotra to be the same as clan; consequently, the two terms are generally used as synonyms. But it is doubtful if the Brahmanic gotra is a grouping of kin, or a clan (Madan, 1962: 104).

Analysing his material on Kashmiri Pandits, Madan further remarks:

Suffice it here to state that the Pandits are divided into many gotras, and the members of each such category are named after one or more pseudo-historical or mythological founding sages from whom they claim descent. But the members of the same gotra do not regard themselves as kin in the normal sense of the term. A man’s gotra name is the same as that of his father and other male agnates, but a married woman belongs to her husband’s gotra. Membership of a gotra, which is acquired by boys at the time of ritual initiation, and by girls at the time of marriage, entails no other mutual rights and obligations between the members except that they shall not enter into marital alliances. In other words, a man should not obtain a wife for himself, his sons, or other wards, who are his agnates, from a family which has the same gotra name as his own (ibid.).

However, as stated earlier, the rule of rishi gotra exogamy is violated quite often. This had happened even in the small Kashmiri village that Madan studied. To quote Madan:

Though the Pandits usually avoid marriages within the gotra, they are not inflexible if a match is eminently desirable …. Two courses are open in such circumstances. Either the marriage takes place and is followed by expiatory rites; or, more often, the bride is given away in marriage by her mother’s brother who acts in place of her father.

In fact, the rules are more stringent regarding the laukik gotra. In the state of Haryana, the Jat community follows these rules stringently and abhors the idea of marriage within a gotra—and the gotra they refer to is not the rishi gotra. In addition to gotra, they also observe exogamy at the level of Khaps.

Marriage within the same Khap is considered incest and the Khap Council metes out severe punishment—they may ask the couple to break the marital tie, or they may ostracize the groom’s family. It may take the extreme form of honour killing, generally by relatives of the girl.

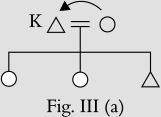

There is an additional decideratum with regard to the rule of exogamy, and is followed more commonly. Brahmanic literature refers to it as the rule of Sapinda. According to this rule,

[A] man should not marry a woman who is a Sapinda (literally, connected by having in common particles of one body (Mayne, 1953: 147) of his mother or father. This rule excludes marriage between ego and his (or her) own agnates of six ascendant generations, and his (or her) mother’s agnates of four ascendant generations (Madan, 1962: 105).

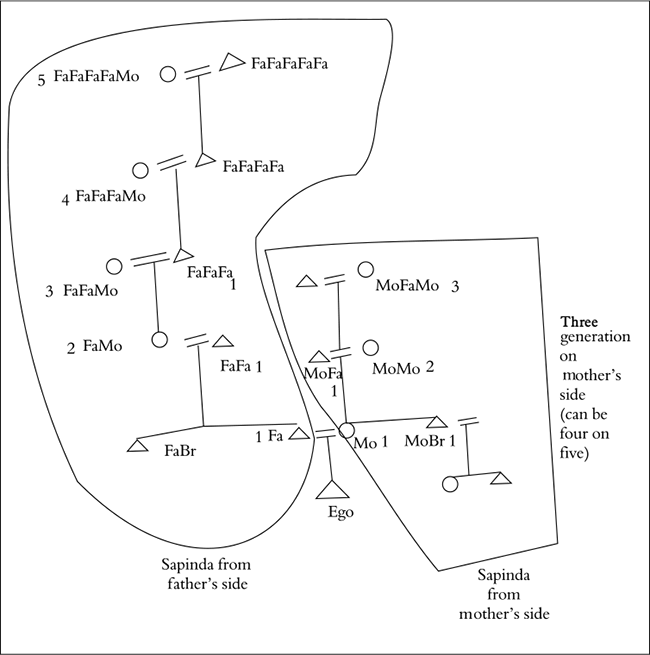

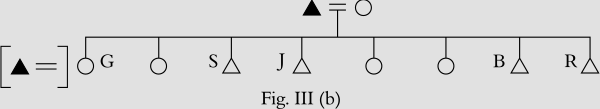

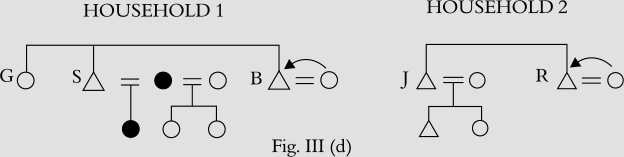

Sapinda rules thus forbid marriage between near kins of an individual from both sides. The concept of pinda is very crucial. In Sanskrit, it has four meanings, all of which convey the sense of contiguity. A Pinda is a kind of ball made by compressing or heaping together particles. It is made either of cooked rice or the rough flour of wheat and barley, and is offered to the dead by close kin as part of the funeral rites. Pinda also means the human body, and thus children are the sapinda of their parents. Since gene transmission can be traced to several ascending generations, all of those thus related are regarded as part of the same Pinda. This word also refers to the property inherited by the descendants. A village or hamlet is also referred to as Pinda. Since members of a lineage usually reside in the same village, they belong to the same Pinda, and hence marriage between them is tabooed. Figure 11.1 illustrates how sapindas are identified.

Figure 11.1 Identifying Sapindas

Figure 11.1 shows the sapinda relations of the ego on both sides. It is important to note that on both sides, the ascending generation line follows the female gotra path. In a patrilineal family, the gotra of the ego would be the same as that of his Fa, FaFa, FaFaFa …; similarly, the premarital gotra of the Mother would be the same as that of her Fa, FaFa, FaFaFa …. It is only the gotra of ego’s FaMo, FaFaMo, FaFaFaMo, and of the MoMo, MoFaMo that changes. In this illustration, we have gone up to three generations on the mother’s side of the ego, and five generations on the father’s side. This gets extended among more conservative people up to seven generations on the father’s side and five generations on the mother’s side. Since the number of rishi gotras is limited, people use the laukik gotras to outline the limits of exogamy on the sapinda path. The other point is that Sapindas vary with the ego. Siblings will have the same Sapinda but not cousins, as their line from the mother’s side cannot be the same, provided that uncles of ego have also married in the same family as ego’s father.

In many parts of North India, people generally avoid four gotras, namely, that of father, mother, father’s mother, and mother’s mother. Taking the bridegroom and the bride together, there will be eight gotras. Suppose the boy’s gotras are A (Fa), B (Mo), C (FaMo), and D (MoMo), and the girl’s four corresponding gotras are likewise L, M, N, and P. It will then be possible to show that in the fourth generation, the composition of four gotras on either side can be the same as in the first generation. See how it works:

ABCD = LMNP

The son from this union will have A (Fa), L (Mo), B (FaMo), M (MoMo).

A scene from Gujjar Panchayat

Second generation: ALBM = CNDP (this marriage can take place because the four gotras are different).

Their product will be ACLN.

Third generation: ACLN = BDMP (this marriage can take place because the four gotras are different).

Their product will be ABCD.

Fourth generation: marriage can be ABCD = LMNP (this marriage can take place because the four gotras are different, and is the same composition as the first generation).

Similar variations are found among other groups and in different regions of this vast country. Agrawals,8 for example, are said to be divided into 18 exogamous divisions. The Rajputs, belonging to the Kshatriya varna, are divided into four Vanshas (lineage will be a smaller term for this; Vansha is used for a successive line of descent); they claim to have descended from the Sun, the Moon, the Fire, and the Serpent, and are called Suryavanshi, Chandravanshi, Agnivanshi, and Nagvanshi, respectively. The Suryavanshis are divided into Guhilot, Kachhwaha, and Rathore; the Agnivanshis are divided into four sub-divisions, of which Chauhan and Parmar are more prominent. There are further sub-divisions such as the Shaktavat or Chundawat. The pattern of exogamy among them is different.

It is important to delink gotra from vansha. This Sanskrit word is used for bamboo. As a simile, it is used for the successive line of descent from father to son. In royal families, it is used to determine succession following the principle of primogeniture. The eldest son is the heir-apparent. When the king has more than one son, then only that son who is in the direct ancestral line is picked out as belonging to a vansha; the others are not counted—this is similar to the way the bamboo grows straight in nodes. Vansha is thus a linear arrangement to determine the line of descent. As against this, the term kul refers to the patric family in its entirety. It is an aggregate of kins in a great family, suggesting a genealogical link but not necessarily a common residence, despite living in the same locale. When kuls became larger and members dispersed to other places, new kuls were formed, and gradually the distance from the original kul increased. It is the various kuls born out of a common ancestor in the remote past that may have a common gotra. In due course of time, some kul descendants might forget the gotra name and use only the kul name as a suffix to their names. In such cases, the new suffix might take the place of a gotra, and marriages between persons of the original gotra and the new gotra may take place. Exogamy is observed at the level of vansha and kul.

We have earlier mentioned the practice of village exogamy prevalent in North India. This is reported in most ethnographies as relative to village India. To quote Madan, ‘Generally speaking, the Pandits of a village prefer to give their daughters in marriage in nearby villages, though not in their own village … proximity facilitates mutual visiting and prevents the withering away of affective ties’ (Madan, 1965: 110). However, when ‘it comes to bringing a daughter-in-law into one’s home, marital alliances with relatively distant villages are not disfavoured too much’. But they do not encourage intra-village alliances. The

Pandits say that for a family to have their sonya in their own village is unwelcome for several reasons. Firstly, an easy and quick access to her natal household stands in the way of a woman’s speedy acceptance of her conjugal chulha as her home, and consequently retards her assimilation into it. Secondly, sonya are expected to have formal relations with each other, at least during the first few years of the relationship …. Finally, the Pandits say that it is conducive to better relations … if they do not know of the skeletons in each other’s cupboards …. Therefore, sonyas in one’s village are said to be as unwelcome as ‘boulders in the yard and a flood in the garden’ (ibid.: 111–12).

We have earlier mentioned that such a practice is confined to small villages, as most people residing in it are close relatives and are thus bound by rules of lineage or gotra exogamy.

This somewhat detailed explication of the concept of exogamy associated with the Hindu caste system should be enough to drive home the point that caste is a pervading concept; however, the manner in which it regulates marriage differs a great deal. The only generalization that can be made is that within each caste that functions as an endogamous unit, there are exogamous divisions known by different names; they function to ensure that marriages among socially defined closed kin are not contracted. We may also mention that there is also the practice of hypergamy, called Anulom, which allows the boy of a socially recognized upper group to marry a girl from the lower stratum. Such an arrangement can be within a larger caste divided into the so-called sub-castes,9 or it can be between a group of castes adjacent to each other on the social ladder. Scriptures also refer to the opposite of this practice as Pratilom (hypogamy) in which a girl of the upper stratum marries a lower-class boy.

A Note on the Joint Family

In this book, we have used the term extended family with its sub-types as vertical or lateral or both kind of extensions. In India, the word joint family is commonly used and is often mentioned as the key characteristic of Hindu society, in addition to caste and village. Implicit in this is that ‘joint family is the norm for familial institutions in India’. Witnessing the increasing number of simple families—that is, nuclear families—it is generally lamented that the processes of modernization have led to the dissolution of the joint family.

The notion of joint family is that of a group that is substantially large and is composed of people of more than one generation. At times, it corresponds to the kul or kutumb, or khandan. Analysts of the Indian family have suggested that there is a need to distinguish between an ideal type and the actually existing structures. An emotional bond and physical togetherness are also separable concepts. Similarly, there is a need to distinguish between a sociological reality and a jural-legal entity.

This is a field in which A. M. Shah has done commendable work and we shall draw mainly from his contributions. A selection of his critical essays published as Family in India10 is our source.

The Varied Usages of the Term Joint Family

Shah hinted at the lack of uniformity, and difficulties arising there from, in the usage of the term joint family.

- Joint family means two or more simple (nuclear) families living together. The extensions can be patrilineal or matrilineal. The problem in this usage is regarding the ‘limit of extension’. Shah questions the view of jurist J. D. Mayne, who wrote in 1906 that ‘There can be no limit to the number of persons of whom a Hindu joint family consists, or to the remoteness of their descent from the common ancestor, and consequently to the distance of their relationship from each other’.

A.M. Shah (Born 22 August 1931)

- Many writings talk of limits of extension in terms of ‘generation’—a three or four-generation family. Shah argues that

There is … no unanimity about the meaning of generation or about the method of counting the number of generations. In some writings the number of generations refers to both the dead and the living generations, and in some others, only to living generations. Some include, others do not, the common ancestor’s generation in the number of generations … For example, it is quite accurate to describe a group composed of a man, his sons, and sons’ sons as a three generation group, if all of them are alive and if the common ancestor’s generation is included in the number. However, frequently a group including only living brothers and their sons but excluding the brothers’ dead father is described as a three-generation group because the dead ancestor’s generation is included in the number of generations. Frequently, it is also not clear whether daughters are included among patrilineal descendents (1998: 18–19).

- It is not clear whether generation has any reference to the wives of patrilineal descendents. A good example is of a family composed of a widow, her sons, and grandsons, which is frequently described as a two-generation group and not a three-generation one.

- ‘How should we describe a group composed of a male ego, his wife, their son and his wife (but not son’s child)?’ Since a nuclear family is also a two-generation group, how do we differentiate between a nuclear family and a joint family on the basis of generations? If three generations are needed, then how do we term the joint living of two nuclear families of brothers?

Shah regards any unit larger than the elementary family as a joint family. There is a wide range of possible types of composition. If we add to an elementary family, even one person not belonging to it should be considered, strictly speaking, as constituting a joint family. Thus, for example, considering the father in an elementary family as ego, the addition of his widower father, or widowed mother, unmarried, divorced, or widowed brother or sister, son’s wife or daughter’s husband, would bring about a joint family. It is important to realize that the addition of any one of these relatives means an addition of more than one relationship, for example, the addition of the son’s wife means the addition of relationships not only between the son and his wife but also between father-in-law and daughter-in-law and mother-in-law and daughter-in-law.… The structure of the household becomes more and more complex when more and more categories of relatives are included …. [A] household including one married son has a different configuration than that of a household including two or more married sons …. (p. 21).

Shah is making the important point that the joint family is not a single type. If ‘we use the term joint family for the household group, then our aim should be the analysis of household life in its entirety, and if this is the aim, the classification of households should take into account all the relatives in a household’ (p. 22). The three classifications taken from three field-based studies also indicate several types of joint families, confirming the argument advanced by Shah.

In almost all the writings on the Indian family the household of the maximum depth11 is described as a multifunctional group, all its members living under one roof, eating food cooked at one hearth, holding property in common, pooling incomes in a common fund, incurring expenses from the same fund, participating in common family worship, and working under the authority of the senior most member (ibid.: 23).

Such a unit also exists, but it is more an ideal model than a reality. As Shah puts it:

[T]here would also be cases in which the members of the defined genealogical unit are divided into separate households, but are holding property in common, carrying on joint occupational activities, and participating in some common rituals and ceremonies. Even this is a simplified description, because household separation may coincide with separation of property and occupational activities but not of ritual and ceremonial activities (ibid.: 23).

The fact is that only a few families correspond to the ideal. Other families remain interrelated in a variety of ways. These units are different in structural terms, but remain united by some cultural norms and emotional ties. According to Shah, joint ownership of property is a legal concept and needs to be distinguished from the sociological conception of family.

Family in Contemporary India

As was mentioned in Chapter 10, there are several ways of classifying the family. It is not possible to provide statistics at the all-India level of the exact percentages of the family that is nuclear, polygynous or joint, that is extended. Moreover, extensions of the family differ in their social composition and demographic structure (sex, age, marital status, etc.). The most significant statistic that is available relates to the size of the family, as enumerated by the various decennial censuses. We also have data from individual field studies at the micro level to give us some idea of the composition of the families.

Before we refer to the all-India statistics, we can provide data from three empirical studies carried out by (i) N. K. Das12 among the Nagas (Zounuo Keyhonuo Nagas) of the North east; (ii) T. N. Madan among the Pandits in rural Kashmir; and (iii) Yogesh Atal in two villages of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, respectively. From this, we can get an idea of the types of family commonly found in India.

Zounuo Keyhonuo Nagas (Angami Nagas)

Das carried out the study in a village called Viswema—a settlement of nearly 549 households. While the word kilokhro is used for the family, the basic domestic group is called misokeswe, which ‘is a unit of food consumption and property owenership’. The prefix miso refers to a hearth, and the people sharing a common miso constitute a misokeswe. In this society, ‘families are not counted on the basis of the existence of houses, but on the basis of the existence of misos (hearths).…’

Das has used the term ‘family’ for a kingroup and ‘household’ for the basic domestic group that we have called a family. He also uses homestead and household as synonyms. But the point that he makes clear is that large families may live under a common roof but have separate hearths. Misokeswe is, in fact, a nuclear family. When two related nuclear families live under one roof but have separate hearths, that bigger unit is called kilokhro. A stem family-like situation is part of the domestic cycle, which ultimately gets separated.

The married women are the spouses of the male agnates of the household. On marriage a woman is brought into her father-in-law’s household but the process of household extension, in normal conditions, does not continue further. After the marriage of the second son the household necessarily segments (Das, 1993: 41).

The elder son moves out to establish his own hearth, and the younger son continues to live with the parents. While the authority of the elder son is respected, in this society it is the younger son who acquires the parental house and a larger portion of the landed property. This is a modified version of ultimogeniture, very similar to the one prevalent among the matrilineal Khasis and the Garos of the Northeast. A Naga myth reinforces the process of such separation. Nagas regard the living of three married woman in the same household as inauspicious as it affects the family fortune in three ways: ‘ kezekesuo (quarrel), kechukenyii (sickness), and setsusezie (poverty)’.

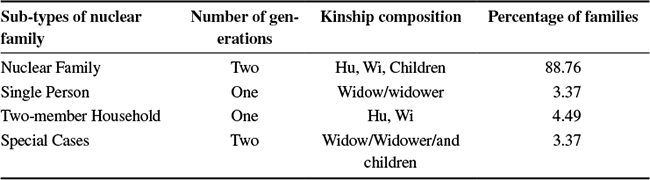

In his sample, Das found that 89 per cent families were nuclear and only 11 per cent were extended. However, in the basic category of the nuclear family, Das has used four sub-types. The distribution of the 89 families is given in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2 Distribution of Families under the Nuclear Category

The 11 cases of the extended family consist of nuclear families of father and the son, and in some instances the inclusion of widowed daughters and their children.

Family in a Kashmir Village

Madan has used the word ‘household’ for the unit that shares a common hearth, and family (called chulha, meaning hearth) for a group of households who share a common name ‘and often even by all or most of the families belonging to a common patrilineage’ (Madan, 1956–57). Using the term family, Madan further writes that ‘unrelated families and households also may have a common name.’ Such family names are called kram or zat. Most pandits use these names as suffixes. Unlike Nagas, where the hearth defines the boundary of a family as a unit, the word chulha (which is literally the hearth) in Kashmir represents a grouping of agnatic kinsmen: ‘grandfathers and grandsons, fathers and sons, uncles and nephews, siblings and cousins’ and the wives of the married male members, and unmarried daughters.13

T. N. Madan (Born 12 August 1933) (Courtesy: © T. N. Madan)

The 87 households, with a population of 522 persons, in Madan’s village live in 59 houses (architectural units). The size of the households varies between 1 and 18. According to his calculations,

[F]irstly, 362 persons, representing 69.3 per cent of the Pandits of the village, live in households with one to nine members, and the number of such households is14 74, or over four-fifths of the total. Secondly, the mean average size is six and the mode five. And thirdly, there is only one household with as many as 18 members. One of the main characteristics of the Pandit household thus is its small size (Ibid.: 57–58).

In further analysis, Madan has suggested that family extension is a temporal phenomenon, a part of the developmental cycle of the domestic group—a point that is also made by Das with regard to the Nagas.

In the following box, a case study of the developmental cycle from Madan’s monograph is reproduced.

A CASE STUDY FROM A KASHMIR VILLAGE

T.N. Madan

Family and Kinship: A Study of the Pandits of Rural Kashmir. Revised and enlarged edition, published in 1989 by Oxford University Press, New Delhi, pp. 59–61.

Keshavanand was the adopted son of Vasanand, the fourth mahant. His marriage, arranged by his father, took place in 1895. When the latter died in 1906, Keshavanand’s succession to the mahantship was challenged hy Shivanand, another claimant to the office, on the ground that a married householder could not become the mahant. The government, on being appealed to by both the parties, decided against Keshavanand, and his rival became the new mahant.

Vasanand had owned two landed estates, one in his own name and the other on behalf of the goddess Uma. (Under Hindu law a divinity represented by an idol, shrine, or temple can own property.) Keshavanand inherited part of the former estate, and built himself a new house (incidentally, the first four-storeyed house in the village) in which he took up residence with his wife, two daughters and a son.

By 1914 Keshavanand’s wife had borne him two more daughters and two more sons. In that year the eldest daughter was married. Four years later, a son, the last of Keshavanand’s children, was born. Meanwhile, his eldest daughter had become a childless widow and had returned to live with her parents.

Keshavanand’s second daughter’s marriage took place in 1919, his first son’s and third daughter’s in 1923; and his second son’s and fourth daughter’s in 1928. In 1936, when Keshavanand died, his second son was already a father, so that the former’s death reduced a paternal-fraternal extended family into a fraternal extended family.

Two years later the elder brother’s wife died. In 1939 the third brother married, and a year later the eldest brother remarried in 1942 their widowed mother died reducing the generation depth from three to two.

In 1946 the youngest brother’s marriage took place. Later that year dissensions led to the partition of the chulah. The first and the third brothers, their wives and the former’s children, and the widowed sister of the brothers, formed one partitive household, and the rest of the members of the unpartitioned chulah formed the second household. Both, however continued to live in the same house.

In 1948, both these households broke up into four separate households; the widowed sister continued to live with the eldest brother. Five years later (in 1953) the youngest brother amalgamated his household with that of his eldest brother. No further developments have taken plate since then.

Family in the Villages of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh

Yogesh Atal studied two villages, one from Rajasthan and the other from Madhya Pradesh, in the late 1950s (see Table 11.3). These small multi-caste villages had a population of 501 and 369, respectively, and they lived in 96 and 91 families. In both villages, while the number of simple families—that is nuclear families had a relatively high percentage (45.8 per cent and 31.9 per cent respectively), the number of extended families was also quite large. But if the incomplete families—that is, nuclear families in the making or the residual nuclear families are added, then the cluster of simple families, including potential and nugatory nuclear families and the residual ones, is quite high—60 and 56 per cent, respectively. The average size of the family in the Rajasthan village is 5.23, and in the Madhya Pradesh village is 4.06. What is significant is the considerable number of extended families, and in them vertically or vertically-laterally extended families are predominant, suggesting that lateral extension is less prominent and remains a temporary phase.

Table 11.3 Family Types and Their Incidence in Two Villages of Rajasthan and MP

Note: This table is made by combining data from two tables in Atal, 1979, second edition, Tables 3 and 5, pp. 86, 89. This is done to make comparison possible.

Family Types on the Basis of Census Enumeration

To get an all-India picture, we take recourse to the census data. Unfortunately, census records do not provide information about the relationship structure within the household. What we have is information about the size of the family.

In census definitions, the word household is generally used in place of the family. All those living in the same house and sharing a common hearth are included in the definition of the family or household. Such a definition gives an idea of the size of the family, but not of its composition in terms of kinship. As an aside, it should also be said that in earlier censuses, sometimes social and sometimes structural (that is architectural) definitions were used. Social definition focused on the number of persons sharing a hearth, the structural definition, on the other hand, included persons living in the same house. Thus, some states used the ‘social’ definition while others used the ‘structural’ definition. This made the data somewhat non-comparable. But from the 1951 census onwards, the definition of the ‘household’ has remained uniform. A household is defined as a ‘group of persons who lived together in the same house and took their meals from a common kitchen’.

A comparison of the average household size between 1911 and 1961 is given in Table 11.4.

These figures indicate that the size of the household is increasing rather than decreasing. In other words, there are more persons per household today than in the beginning of the twentieth century. This signifies that while the joint family may have been the ideal form of family, in actual fact such families were not the norm. An average size of 4.6 can include husband, wife, and two or more children—such a composition cannot qualify for a joint family. Furthermore, the data also refute the western generalization that increasing urbanization leads to a reduction in the size of the family. Henry Orenstein used census data from 1867 through 1951 to conclude that industrialization and westernization have not decreased the average size of the household. Similarly, a study of Pune city by Richard Lambert also found that the average size of the family of those working in industrial enterprises was larger (5.2) compared to the average family size of the town of Pune (4.5). Again, the larger size in the industrial area need not reflect the pattern of joint family. Other studies suggest that rural migrants to urban areas tend to accommodate fellow villagers or distant kin in their households.

Table 11.4 Average Size of Household, 1911–91 (Based on calculations made by Henri Orenstein and A. M. Shah)

Year |

Average size |

|---|---|

1911 |

4.6 |

1921 |

4.6 |

1931 |

4.8 |

1941 |

5.0 |

1951 |

5.0 |

1961 |

5.08 |

1971 |

5.42 |

1981 |

5.55 |

1991 |

5.51 |

Analysing the household data from various censuses, Shah reached similar conclusions. The increasing average size of the family is attributed by him, and rightly so, to the increase in the life expectancy, ‘from 32.5 to 55.4 years for men and from 31.7 to 55.7 years for women during the period 1941–50 to 1981–85’. As a consequence, ‘the proportion of the aged people (60 years and above) in the total population has increased from 5.50 in 1951 to 6.42 in 1981. The ratio of the number of elderly persons to the number of children, called the index of ageing, also increased from 13.7 for every 100 children in 1961 to 16.2 in 1981.… In other words, it is the older people rather than children who have contributed to the increasing average size of household’ (1998: 68). From this, it can be concluded, as did Shah, that there is a rising number of joint households.

Using the data from the study conducted by C. Chakravorty and A. K. Singh on House-hold Structures in India—Census 1991, carried out under the auspices of the Registrar General of India, Shah has drawn a table to indicate the incidence of different types of family, which is reproduced in Table 11.5

The analysis suggests that the number of nuclear households—complete or potential or nugatory—is somewhat larger, constituting 54.02 per cent. But the joint households of different types are a significant 45.98 per cent. This data dismisses the general impression of the corrosion of the joint family. The 1981 data do indicate the fact that the percentage of the nuclear households is somewhat larger in urban than in rural (58.9 per cent and 52.52 per cent respectively) areas; but the difference is too small, whether we considered nuclear households or joint households. In this regard, the distinction made by Shah between a family and a household is significant. It is at the level of a household that we notice the jointness of living not corresponding to the ideal of a joint family. The household structures are small in terms of numbers and limited in terms of kinship composition, and this does not seem to be a new phenomenon. But in terms of kin solidarity at the emotional level, and visibility during special occasions, the ideal of joint family still holds good. Social scientists—not only sociologists, but also demographers and economists—have thus found this distinction between household and family helpful in social analysis.

Table 11.5 Households by Kinship Composition in India, 1981

Composition |

Per cent |

Nuclear household |

54.02 |

Single member |

5.80 |

Head and spouse |

4.98 |

Head and spouse with unmarried children |

38.74 |

Head without spouse but with unmarried children |

4.50 |

Joint household |

45.98 |

Head and spouse with or without unmarried children but with other relations who are not currently having spouse |

16.48 |

Head without spouse but with other relations of whom only one is having spouse |

3.50 |

Head without spouse, with or without unmarried children, but with other unmarried/separated/divorced/widowed relations |

5.61 |

Head and spouse with married son(s)/daughters(s) and their spouse, and/or parents, with or without other not currently married relation(s). Head without spouse but with at least two married sons/daughters and their spouses, and/or parents, with or without other not currently married relations |

16.62 |

Head and spouse with married brother(s)/sister(s) and their spouses, with or without other relations(s), including married relations. Head without spouse but with at least two married brothers/sisters and their spouses, with or without other relations. |

3.60 |

Other households not covered elsewhere |

0.17 |

Total |

100.00 |

Source: Census of India 1981a: 4–9; Chakravorty and Singh 1991: Table 2.2.

A. M. Shah is firmly of the view that the norm of joint family continues. He put forward two arguments:

One, that up until 1951, coinciding roughly with the end of British rule in India, the emphasis on joint household was greater among higher castes and classes, who formed a small section of the society, than among lower castes and classes, who constituted the vast majority of the population. And two, that while this emphasis appears to have declined in recent times mainly in the professional class, drawn mainly from among higher castes in large cities, it has increased among the masses in rural as well as urban areas. In statistical terms, the upward trend among the latter has more than offset the downward trend among the former to such an extent that the overall change in the society is upward. This is the reverse of the long established belief not only among the intelligentsia in general but also among many social scientists that the joint family is disintegrating (1998: 4).

We must, however, note a certain shift in the pattern of socialization. When families were living jointly—in the sense that they were sharing a common habitat even when establishing separate hearths—the male as a father figure was viewed differently. Living in the midst of elders, the newly married boy of the family employed considerable discretion in showing his intimacy in public towards his spouse, and felt shy of announcing his paternity. He maintained a certain distance from his own child, leaving the responsibility on the shoulders of other elders in the family, or on the elder cousins of the newborn. Instances galore where the father of the newborn fondling his own child in privacy would drop the child from his lap upon the entrance of an elder on the scene. As psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar writes, ideology demands that in order to preserve family cohesion, a father be restrained in the presence of his own child and divide his interest and support equally among his own and his brothers’ children. Moreover, many a young father was embarrassed to hold his infant child in front of older family members since this fruit of his loins was clear evidence of activity in that particular region.15

Upon enquiry regarding the paternity of the child the typical response is: ‘this is yours’—a different version of teknonymy. ‘Playing with or taking of their infant and small sons is not what fathers do, their major role lying in the disciplining of the child’, adds Kakar. That is why mothers threaten the erring child by saying that they would then report to the father. The father’s image in the traditional pattern was that of a disciplinarian and punishment-giver.

Whether such behaviour is a result of the value of keeping the sexual act a secret—performed discreetly—or of sharing the values of the joint family that foster family solidarity is a different matter. But this certainly prevented the father’s direct involvement in the child’s early socialization, and introduced the new entrant to the larger world of the joint family. In the traditional system, as Kakar highlights, the father’s role becomes prominent when he takes the son as an apprentice to his place of work and tutors him in the family vocation.

Both ideologies of fatherhood—one having its source in the structure of the larger family and the other in parenting roles and obligations based on gender—have decisively weakened in middle class families16.… Middle class fathers have begun to provide early emotional access to the son, not only attenuating the overheated quality of mother-son bond, but also laying the foundations for a less hierarchical and closer father-son relationship.

The geographical distance created by the dispersal of families has certainly affected the emotional bond that existed in families that lived jointly, sharing a common space. It is, however, more visible in terms of economic independence, involvement of other actors and agencies in the process of socialization, and in the occupational profile of the members of the family. This has also affected the families belonging to those castes that were identified in terms of their ‘traditional’ occupations. Those families that continue with their traditional occupations of their respective castes may still follow the older pattern, but the newly emerging middle class among these castes exhibit new features. What I. P. Desai said of the family long ago still holds true: ‘Joint family is dead, long live the joint family’.