CHAPTER 6

Communities, Associations, and Formal Organizations

In the previous chapter, we have talked about primary groups and small groups. Here we turn to relatively larger groups: communities, associations, and formal organizations.

A community is a group of groups, whereas associations and organizations are formal groups.

The Concept of Community

Community is a commonly used word, but it connotes several meanings. Some people use it almost as a synonym of society; others use it for a geographically distinct local community or for a group of people who are of the same origin. In the West, it has also been used for ‘total institutions’ such as prison or mental asylum—as an extension, the term has also been used for residential schools.

To quote Jessie Bernard: ‘Four classical paradigms encompass most of what we know about the sociology of the community…’(Bernard, 1973: 8). These were:

- Ecological Paradigm: ‘which explained how populations have distributed themselves, how the resulting settlements have become spatially structured, and how the structural components have varied sociologically. The “exemplar” model here was the city of Chicago.’

- Ranked-status or social class paradigm: Its exemplar model was the study of the Yankee City.1

- Power Paradigm: Study of power relations in a community.2

- Gemeinschaft and gesselschaft,3 focusing on spatial aspects of settlements.

Of the four types, the first three concentrated mainly on single and urban communities, while the fourth paradigm classified the communities in terms of their habitat into rural and urban.

In all of these usages, the community was defined in terms of locale, common ties among people inhabiting the area, and social interaction between them, whether it was to divide the society in terms of classes or ranks, or to classify the communities in terms of the pattern of settlement. There are studies of different patterns of urban and rural settlements, or power structure, or the nature of social relationships.

Community studies, as they developed in the United States, focused on the city and studied distribution, sub-community social structure, urbanization, reorganization, and social disorganization. Most settlements in America are urban; some have populations as low as 12 to 15 families. Even the communities that are called villages have nothing in common in terms of attributes found in the villages in developing countries.4

Anthropologists treated tribes as communities living in small hamlets and villages, and studied their way of life. In the 1960s, when village studies were in vogue in India, this term—community—was quite often used as a qualifier—village community, that is, village as a community.

The term ‘community’ has variously been defined, particularly by the American rural sociologists. A strong Community Development Movement (CDP) in the Unites States in the 1950s made this concept very crucial. But the communities addressed by the movement were mainly urban communities. Of course, some communities were called villages, but their profiles were basically urban, and in no way comparable to the villages in countries like India.

The word community assumed special significance in India when in the 1950s the government launched a massive programme for the upliftment of villages at the prompting of American experts—Albert Mayer and Douglas Ensminger. This was called CDP and focused on village communities.

It should be mentioned that most sociologists working in the rapidly urbanizing and industrializing Western society began to take the position that community—as a meaningful social structure—has only a historical significance. Following Simmel’s distinction of gemeinschaft and gesselschaft, these scholars argued that community traits were to be found in gemeinschaft and that the urbanizing society corresponds closely to gesselschaft. But there were others, like Harold F. Kaufman, who thought that community-type structures also exist in urban settings, and deserve to be studied because of their significance in planning community development.

Concern for community, both in the United States and in India, in the 1950s and 1960s drew some scholars to conceptualize the term community. But most American authors focused on their own society and generated a definition for community that was applicable in their context.

To understand the conceptual crisis, it is important to understand the difference in the two societies—America and India.

American society is basically a society populated by migrants who generally settled in urban conglomerates. The native Americans—called Red Indians—were pushed into reserved areas. Thus, the New World residents drawn from different cultural contexts—mainly European—had to struggle to develop a community life within the city context. The ‘creation of a community’ and its ‘development’ was the key issue for American planners and policy makers.

In contrast to the US, India represented a host of village communities of great vintage. Here, it was not the question of ‘creating’ communities, but of ‘developing already existing communities’ by removing their backwardness and enlarging their cognitive horizons. The effort was intended to relate these communities with the wider world of the great civilization of India. Thus, despite having the same name, the CDP addressed two different issues in the two countries. In India, it meant the development of rural villages with a view to linking them with the wider Indian society. In the United States, it meant developing community life amongst people of common origins in the newly created urban settlements as a spatial community with networks of communication and interaction. Additionally, migrant groups originating from the same culture area but located in different parts of the city also felt the need to develop a ‘community’ of their own—for example, Italians in Chicago, or Puerto Ricans in New York.

Definition of the concept of Community

George A. Hillary Jr., of the University of Kentucky, Lexington, collected 94 definitions of community to analyse their content and produced an excellent paper titled ‘Definitions of Community: Areas of Agreement’.5 Hillary did not attempt to find out the number of times any particular definition has been used,6 but concentrated on various formulations. He identified 16 different concepts in 22 combinations in these definitions. He discovered that 69 of the 94 definitions were ‘in accord that social interaction, area, and a common tie or ties’ are important elements of community life; of these, the first two, namely, social interaction and area, have a much higher frequency. In another study, Hillary Jr. attempted to find common characteristics of a community in 15 different settlements in different countries.

From all this, he concluded that a community is a field of social interactions, covering all aspects of social life, for people of known membership. Its visibility is enhanced when the members occupy the same habitat. In other words, a common habitat may give rise to community life, or a series of social interactions create a mental space for this special group which may ultimately begin to live together. This can also be seen in big towns in India. People who come from the same region tend to live in the same area and the place also gets a name that reflects this linkage. In Delhi, to take just one example, people from Bengal generally prefer to live in a colony called Chittranjan Park (or CR Park); similarly, Ramakrishnapuram was initially inhabited by people from South India. In a study of Pols7 in Ahmedabad, Harish Doshi8 mentioned that people hailing from the same village tend to live together in such Pols. These settlers have created institutions identical to those prevalent in their parent village, and have thus re-created the village community in the midst of an urban conglomerate. Since such settlements meet most of the social needs of the inhabitants, they function as ‘islands’ in the town, but remain linked with the wider community in several ways, mainly through their participation in the urban economy as workers or as petty shopkeepers.

A community is in some ways, a replica of the wider society. In this sense, one can say that a society is a community of communities. For small societies, where the members live in a limited space and have mostly face-to-face contacts, the terms ‘society’ and ‘community’ are used interchangeably.

Robert Redfield enumerated the following characteristics of the little community:9

- Quality of distinctiveness: where the community begins and where it ends is apparent. The distinctiveness is apparent to the outside observer and is expressed in the group consciousness of the people of the community.

- Smallness: ‘So small that either it itself is the unit of personal observation or else, being somewhat larger and yet homogenous, it provides in some part of it a unit of personal observation fully representative of the whole …. A compact community of four thousand people in Indian Latin-America can be studied by making direct personal acquaintance with one section of it.’

- Community is … ‘homogenous’. Activities and states of mind are alike for all persona in corresponding sex and age positions; and the career of one generation repeats that of the preceding. So understood, homogenous is equivalent to ‘slow-changing’.

- As a fourth defining quality, it may be said that the community we have in mind is self-sufficient and provides for all or most of the activities and needs of the people in it. ‘The little community is a cradle-to-the grave arrangement.’

Redfield’s definition of the little community is aptly applicable to small societies—particularly tribal societies, but Indian scholars working on villages have also found it useful. Combining it with his definition of peasant society, sociologists have treated the village as a little community that is ‘isolable’, although not completely isolated or insulated from other units of the wider society. This definition helped scholars to carry out holistic studies of the villages in India, as an extension of the anthropological approach. It may be noted that even a small tribe lives in a number of small settlements—which can be called villages—and they are studied holistically in terms of the area in which these settlements are spread. The small settlement is not the unit of study, and the entire tribe spread in a number of such hamlets is regarded by the anthropologists as constituting a community. Those who studied Indian villages also talked of the ‘unity’ and ‘extensions’ of the village to take account of the interactions of the distinctive village community with other villages in the region, and with the country as a whole.

To sum up, a community, understood as a group of people living together in a given geographical space, does not cater to ‘this or that particular interest’10 but provides for ‘the basic conditions of a common life’. It is a miniature form of society. In fact, small societies are generally referred to as ‘communities’ because their members are spread over a limited area and they virtually maintain primary relationships with other residents of that area. For most primitive tribes, authors have used the term tribal communities when in fact they were talking of societies. One can say that a large society consists of several local communities—villages, towns and cities—and even regions whereas a small society is a community by itself.

The word community is also used as an extension of the same phenomenon, for people with a common ethnic origin, but dispersed from the original habitat. What unites them is the community sentiment. Thus, we may say that locality, or community sentiment, or both, are the bases for defining a community. It is in this sense that people also talk of caste, or a group of castes, having the same name but hailing from different parts of the country, as a community. References to Yadavs or the Muslim community are instances of this phenomenon. Ethnic communities, or religious groups, or local communities are thus examples of what some sociologists call ‘ascriptive solidarities’. The Indian Diaspora in any country are referred to as an Indian community, particularly when they are substantial in number and share a common colony or a ward. In the same sense, people talk of the Italian community in the city of Chicago, or the Bengali community in the city of Delhi. A regional community known by the region (Bengali or Marwari or Tamil) from which it originates is an ascriptive solidarity. Other people living in the same neighbourhood, however, do not form part of that regional community and feel somewhat alienated. In such communities, one can also find a replica of the regional culture.

Formal Groups: Associations and Organizations

Other than communities and primary and secondary relationships is the vast territory of groups—small and large, and formal and informal. We have discussed small groups at some length in our previous chapter. Here we focus our attention on the relatively large formal groups, that are mostly secondary groups.

We may mention here that in recent decades, the concept of non-formal has also come into vogue, particularly in the field of education. To overcome the difficulties of providing education through formal schooling to those who are either adults, or those children who find it difficult to stop participating in the family economy to attend a regular school, a system of non-formal education was devised under UNESCO auspices. Students learning under this scheme do not follow the formal system of learning by attending schools, or using the prescribed textbooks and appearing for examinations. As they do not follow formal procedure, such a practice is called non-formal. However, norms have also developed for this type of arrangement. In other words, the non-formal is also technically a formalized activity. Non-formal, in this context, is used in the sense of being ‘different from the formal’.

Association

Groups that are formal are known by the generic term association. However, a distinction is also made between an association and an organization. An association is generally, but not necessarily, voluntary, whereas an organization is generally, but not necessarily, involuntary. As societies grow large, several of the activities are performed outside of the family in well-organized structures by people who develop various skills and expertise. The functioning of such groups turns formal particularly when these groups become sufficiently large and a complicated system of division of labour evolves within the group. Groups are also formed in order to attain specific goals or to fulfil special needs. Such groups are more often voluntary, and the membership to them is governed by rules and regulations developed by the participating members.

Associations, in this sense, serve as a means to pursue certain specified goals. They are formed when individuals are unable to attain their goals without the help of others. For example, playing a game requires two or more players. These can be played with neighbours casually in non-formal settings. But for certain games you need paraphernalia such as balls, nets, a proper playground, and someone to ensure the proper management of all this. In such a situation, players may come together to form an association, or some entrepreneur may launch a club and invite membership to it. This is a cooperative pursuit that is neither spontaneous nor casual or customary (for example, an activity associated with a festival).

When a group is created expressly for the purpose of pursuing some interests as a collectivity, it becomes an association. People may name it a club, or a society, or an association, or even a party. A trade union, or a political party, is also an example of an association. In this sense, an association is different from a community. A community may have several associations with differing membership. A member of a community selects the associations of which he/she would like to be a member. Thus, no single individual in a community, and therefore in a society, is a member of all the associations within it, and it is not necessary for any person to always remain a member of any particular association. The doors of an association are open both for entry and exit; of course, every association has its own ‘gate-keepers’ to allow entry, and also to throw someone out if found undesirable or if one becomes ineligible, for example, a person would lose his membership to a bachelors’ club upon his getting married. Similarly, age might be a criterion for eligibility; individuals lose their membership when they cross the required age limit; one cannot remain a member of a youth club if the age limit has been crossed; similarly, one cannot join a senior citizens’ club if one has not qualified as a senior citizen in terms of the required age.

The concept of association is also used in a somewhat broader sense to distinguish between an institution and an association. An association refers to a group of people who are in league for some or several common interests, whereas an institution refers to normative practice. For example, take the case of marriage and family. We will never call marriage an association, it is an institution through which the association called family is created. For those who are born into the family, it is an involuntary association as they had no choice in becoming its member, but for the husband or the wife, it might be a voluntary group if they were given the choice to select their partner. In a patrilineal family, the daughter loses her membership in the parental family when she is married into another family, of which she then becomes the member.11 In this sense, some scholars regard family as a replica of the community, and also fit to be named an association. ‘We belong to associations but not to institutions’ say MacIver and Page (1955: 15). ‘Association denotes membership; institution denotes a mode or means of service’(ibid.: 16).

This is a fine distinction. We must, however, be aware of the fact that the word institution is also used for certain types of associations, such as hospital, schools, colleges, university. Comparing one with the other, we quite often say this is a better (or otherwise) institution. In saying so, we refer not only to the associational aspect of it, but also the ‘culture’ of that organization—the norms, the activities, the overall performance that gives it a specific identity. It is in this sense that a person held in high esteem is eulogized by the sentence: ‘He is an institution by himself’. But all these are literary niceties, and should not be confused with sociological concepts.12

Formal Organizations: Bureaucracy

Large-scale organizations tend to become formal and bureaucratic. Organizations are generally known by the explicit goals they are expected to attain. In governments and in private companies, the executive wings represent the bureaucracy of the organization. People manning them are supposed to be trained specialists and are appointed to carry out the tasks of the organization spelt out by the (i) top leadership—elected representatives in the case of democracies, and rulers in the case of authoritative regimes; and (ii) the company heads (including the board of directors) in the case of private business firms. Bureaucracies are thus found in large-scale organizations in the religious, political, and economic sectors of society. Bureaucracies perform a dual role of organizing the work—distribution of roles and responsibilities, creating norms of behaviour within the system and developing norms for dealing with the wider system of society of which it is a sub-system. It is in this sense that formal organizations are a special type of association. A voluntary organization—an NGO,13 for example—needs a small bureaucratic structure to maintain its records and handle the accounts, while its workers might be voluntary workers. A club is another example where the membership is voluntary; people join the club to meet their specific goals, and may opt out of it when they want. Such a club also has a small bureaucracy to handle its membership-related issues. In contrast to this, a government department is a bureaucratic organization which might have the responsibility of carrying out specific activities. In that connection, it might be expected to interact with the public: to attend to their grievances, to clear their applications, to grant them subsidies, to issue them ration cards or driving licences, etc. All this work requires a clearly laid out procedure, a set of rules and a code of conduct for the officials. Such offices are easily identified as bureaucracies.

The use of the adjective ‘formal’ for such groups suggests that these are different from the personal, informal groups. As societies grow large, the problems of their governance and of maintaining ‘law and order’ require handling them in a well-defined manner. Even in a small group such as family, there are some rules of behaviour that are passed on from one generation to other and are observed with a certain degree of sanctity. Thus, the relationship between husband and wife, between husband’s father and son’s wife, and between father and son are governed by the norms of society. But family being a primary group, members have face-to-face relationships and several of their daily interactions are of an informal nature.

When people move outside of their family and of their neighbourhood, to interact with people who are not so close, their interactions are governed by formal patterns of behaviour. Any agency that is created to meet the demands of a populace has to develop some mechanism to ensure that the deals are just and delivery is efficient. Such agencies are created in accordance with the goals and the work within it is divided amongst its workers in terms of their skills. They are trained to know their duties and responsibilities and also the ‘ways of doing’ their job satisfactorily. The social relationships within the organization, and with the ‘general public’ approaching it as a ‘client’, are more impersonal. The church, the state, the various departments of the government, the business houses, the factories, and the school, among others, are all examples of formal organizations. Even an association needs an outfit to run its business. The office of the association is a formal organization that is run by the paid (or honorary) staff who are different from its members. And the business of the office runs along bureaucratic principles.

Bureaucracy, although generally associated with governmental organizations, is a feature that characterizes any formal organization. It is in this sense that we say that corporate offices also have their own bureaucratic structures—a hierarchy of top decision makers, managers and workers, and standard working practices, rules and regulations. Even a church is said to have a bureaucracy. What the word signifies is the point that all big and complex organizations have to evolve the norms of their functioning so that there is no dependence on any given individual. Clearly laid out rules and procedures ensure predictability, and lessen the dependence on any particular official: a new incumbent is expected to follow the same procedure and rules, and therefore, a change in personnel does not, at least in theory, affect the working of the organization. In other words, the routinization of charisma results in bureaucratic procedures; the charisma is transferred from an individual to the chair so that any occupant of the given chair wears the same charisma. As a consequence, the actions become predictable. A person submitting an application knows how it will be processed and how much time will be taken to get a response from the organization.

The word ‘bureau’ signifies ‘office’; therefore, bureaucracy means rule of the office, or of the officers. Through inference, it is used for governmental and semi-governmental offices and secretariats, although the norms of an office are also to be found in other formal organizations such as a factory or a school. Usually, in common parlance, the word bureaucracy is used in a pejorative sense, implying the hurdles caused by the officers who adhere strictly to the rules. In other words, bureaucracy is generally perceived to be a hallmark of inefficiency, of routine work with no place for innovation or deviation from the norm. But as a conceptual tool, bureaucracy stands for impersonality, efficiency, and supremacy of norms and rules in the attainment of organizational goals.

To Recapitulate

With the increasing complexities of governments emerged large-scale formal organizations. The larger the society, the greater are the number of structures and more complicated their hierarchies. A small village community gets linked to a tehsil and district-level administration, which is part of the provincial government, and the various provincial governments function under a central government. Such an intricate system of power distribution requires a clear-cut definition of duties and responsibilities, and powers. With the arrival of the Industrial Revolution in the West, bureaucracy gained its importance in other fields as well. The need was felt to create rational structures to ensure efficiency.

Max Weber, who conceptualized this concept, talked of three types of authority.

The validity to their claims to legitimacy may be based on:

- Rational grounds—resting on a belief in the ‘legality’ of patterns of normative rules and the right of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands (legal authority);

- Traditional grounds—resting on an established belief in the sanctity of immemorial traditions and the legitimacy of the status of those exercising authority under them (traditional authority); or finally,

- Charismatic grounds—resting on devotion to the specific and exceptional sanctity, heroism or exemplary character of an individual person, and of the normative patterns or order revealed or ordained by him (charismatic authority).14

Weber argued that running large-scale organizations requires rational–legal authority. A government is able to function only when its legitimacy is recognized. At various levels, formal organizations are created to meet the specific needs of the people. They cannot run on an ad hoc basis. The people should know the manner of their functioning and the powers and responsibilities of their functionaries.

Weber recounted the following characteristics of a bureaucracy:

- Division of labour. In a formal organization, there exists division of labour. The work is divided into several components, both in terms of sequencing and specialization, and people are recruited to perform those special functions. These are called official duties and they develop a certain specialization in the employees. The basis of selection of candidates is technical qualifications, and these are tested through examination or interviews. The important thing about the bureaucracy is that the officers are appointed and not elected. The top position may be held by an elected person, but that person is not regarded as a bureaucrat. Thus, a minister in the government is an elected representative, but his ministry’s work is carried out by the bureaucracy. That is why a bureaucrat is regarded as an ‘old horse’ compared to the ministers, who come and go. In day-to-day functioning, the minister acts on the advice of the bureaucrats. In a bureaucracy, people climb up the ladder both through training and experience, that is, merit.

- Hierarchy of authority. Implicit in the division of labour is the point that a formal organization is manned by people with different skills and a varied range of experience. Accordingly, they are placed in the official hierarchy where the top position is held by the key decision maker and policy planner. That officer is assisted by experts deputed at the senior level, and the administrative staff that carries out the instructions, maintains office records and manages the finances of the organization. Below them are lower-level staff divided into supervisory responsibility and workers and helpers. Every bureaucracy has established rules for probation, promotion and retirement. An official is subject to strict control and discipline in the exercise of his duties. The offices are organized on the principle of hierarchy, where the lower office operates under the supervision of the higher office.

- Rules and regulations. All formal organizations have set rules and procedures to guide the workers and officers. Since these are written and documented, they are available to anyone in the organization. They are part of institutional memory. As such, the organization continues to function even when any particular officer or worker is either transferred to another position or another place, or leaves the organization for god. Strict adherence to rules is regarded as important for the efficient functioning of the organization. ‘The participants’ orientation to common rules is a source of predictability of behaviour, hence of rationality, for any one person’s rationality in action is severely limited unless he can count on what others will do in particular circumstances’ (Johnson, 1960: 291).

- Impersonality. The work of the organization is carried out in an impersonal way, that is, personal likes or dislikes are not allowed to hamper the task of the organization. In other words, no personal considerations are allowed in a bureaucracy to ensure that it does not get corrupt or that its means are diverted to meet other ends. Not only do the organizations have rules and regulations, but these are also regarded as supreme and emphasis is placed on adherence to them. Of course, rules are also regularly reviewed and amended, but they need to be followed diligently. The rules are framed with a view to facilitating the attainment of the organization’s goals and ensuring that individual workers or officers do not deviate from them. In a way, it is an extension of the principle of a machine. Once a machine is assembled it functions in a well-defined manner, and any change of sequencing or timing might hamper its performance or cause damage to the person handling it. A well-run machine meets its productivity goals; a bureaucracy is also expected to be efficient in the same manner.

Seen in this manner, a bureaucracy is a rationally organized social structure. Its various activities are rationally linked to each other and are oriented towards the goals of the organization. Weber’s conceptualization of bureaucracy follows the model of a machine. Just as machines operate without any feelings and follow the process without any distraction or outside influence, the administrative machine is also supposed to be somewhat dehumanized—in the sense that it treats its clients without love or hate.

In the introductory paragraph to the essay on ‘Bureaucratic Structure and Personality’, Robert Merton has listed all the characteristics of a bureaucracy present in Weber’s formulation. We reproduce them as itemized characteristics here, to serve as a summary of what was said above:

- The various hierarchized statuses ‘inhere a number of obligations and privileges closely defined by limited and specific rules’.

- ‘Each of these offices contains areas of imputed competence and responsibility’.

- Authority ‘inheres in the office and not in the particular person who performs the official role’.

- ‘Official action ordinarily occurs within the framework of pre-existing rules of the organization’.

- The system ‘involves a considerable degree of formality and clearly defined social distance between the occupants of these positions’.

- ‘Such formality … serves to minimize friction’. ‘Moreover, formality facilitates the interaction of the occupants of offices despite their (possibly hostile) private attitudes towards one another. In this way, the subordinate is protected from the arbitrary action of his superior, since the actions of both are constrained by a mutually recognized set of rules’.15

What distinguishes a formal organization from informal groups, then, is the point that these organizations are established to accomplish certain specified goals. These goals could be temporal or long range. We must also differentiate between (i) the relevance of these goals for particular individuals/clients, and (ii) their relevance for the continuance of the organization. We know that for particular individuals, any organization may be of relevance for a particular purpose or period. When their personal goals are fulfilled, they retire from the organization. Their place is taken by others who have similar interests. For example, a school is an organization that is set up to provide education. Students admitted to it remain in it until their goal of receiving education, provided by the given institution, is attained. Upon their passing out—graduating from the school—their positions are filled up by a new set of aspirants. Thus, for students, the utility of the organization is limited for a period, but the utility of the school for the society continues. In this sense, the changing demographic profile of an organization does not mean the discontinuity of the institution. We must therefore distinguish between the goals of the participating individuals and the goals of the organization as such. Similarly, organizational goals can also be divided into main and subsidiary goals.

Some scholars also suggest that organizations may have both manifest and latent goals. A private educational institution—a school or a college—is manifestly created for imparting education, but the latent goal of the organization might be to ‘make money’, and therefore such institutions—particularly the surrogate educational institutions—engage in money-making activities that may be even unethical.16 Charging capitation fees, awarding degrees that are fake, running courses for which proper authorization is not obtained, underpaying the teaching staff, and for this purpose, hiring ill-trained teachers, are such activities that are part of the latent structure of corruption and are carried out to fulfil the unstated goals.

There are organizations that do not have an explicitly formulated ideology. In business firms and corporate organizations, scholars have worked hard to unravel the ideology by carrying out systematic content analyses of the annual reports, speeches of the presidents of the companies in the meetings of the boards of governors, or in the meetings of their shareholders, in the orders and instructions issued by the management to the staff and workers, and in their advertisements. Business firms are generally flexible with respect to their organizational goals, as they respond to the changing economic and political environments.

Writing about governmental bureaucracies, Merton says:

Most bureaucratic offices involve the expectation of life-long tenure .... Bureaucracy maximizes vocational security. The function of security of tenure, pensions, incremental salaries and regularized procedures of promotion is to ensure the devoted performance of official duties, without regard for extraneous pressures. The chief merit of bureaucracy is its technical efficiency, with a premium placed on precision, speed, expert control, continuity, discretion, and optimal returns on input. The structure is one which approaches the complete elimination of personalized relationships and non-rational considerations (hostility, anxiety, affectual involvements, etc.) (Merton, 1964: 196).

Business firms continually face the problems of turnover of their personnel, technically known as the ‘attrition’ phenomenon. People who are professionally sound generally tend to be occupationally mobile, as their skills have a high market demand. Those who prefer to remain organizationally loyal rise in the hierarchy on grounds of seniority and loyalty, but their inter-organizational mobility remains rather limited. In the universities, teachers move from lectureship to professorship via the position of reader, mainly on the basis of the number of years served in a particular position; but if any university lecturer wishes to move to another university for a higher position, his/her candidature is examined not only in terms of the number of years of experience, but also in terms of research publications and overall image in the profession. Efficiency-oriented organizations also insist on better performance and skill enhancement while promoting an employee to a higher position.

Organizations are also judged in terms of effectiveness and efficiency. Ideally, every organization strives to be both effective and efficient. An organization is regarded as effective when it is able to attain the goals for which it was set up. It is regarded as efficient when the goals are attained with a favourable net balance of consequences in terms of time, energy, and money; when there are savings in terms of these three variables and yet the goals are properly attained, the structure is regarded as both effective and efficient.

An effective organization is one that has (i) high productivity, (ii) needed flexibility in terms of its approach to rules and to structures, and (iii) capacity to adjust to changes in the external milieu. The organization must be able to efficiently handle internal conflicts and inter-organizational strains. Internal conflicts arise because of the inevitable growth of informal groups. The management must have its radars in action to continuously assess the changing situation and take timely action to resolve the crises, rather than allow them to grow and interrupt the normal processes. Such actions demand a flexibility of approach. A good administrator goes beyond structural variables to accommodate personality factors and changes in the external environment.

An organization is thus viewed not as a closed system, but as an open system with its interfaces with the wider social system. An organization is connected to a variety of other organizations and groups. This networking differs from organization to organization. When we talk of a government department, the department is related with other departments of the government—more closely with some, less so with others. Intergovernmental transfers provide linkages between them at the level of individuals. Similarly, specific departments relate with specific organizations in the public sector. The Ministry of Human Resource Development, for example, has direct links with the University Grants Commission(UGC), The Central Board of School Education (CBSE), The National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), the various universities (Central and State, Private and Deemed) and colleges, the IITs and IIMs. They will be part of the organizational structure of the HR ministry. But for each individual university or college, the links with other similar institutions will have a distinctive profile. Those that would constitute the organizational set of a particular institution have their own organizational set in which, other than that particular institution, there would be organizations that may not be a part of the organizational set of the second institute.

Concept of nation-set

In 1968, Yogesh Atal developed the concept of nation-set along similar lines. The concept of organizational set is an extension of the same phenomenon. In an article titled ‘Subordinate State System and the Nation State: Tools for the Analysis of External Milieu’,17 Atal distinguished between four different types of nation-sets, namely:

- Contiguous boundary nation-set

- Common interest nation-set

- Membership-role nation-set

- Non-membership nations: the out-groups

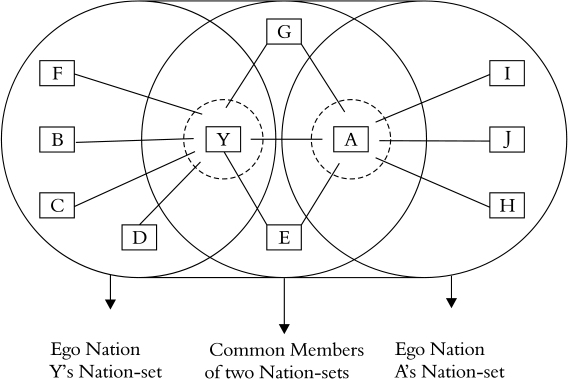

Figure 6.1 illustrates the contiguous boundary nation-sets of two countries, Y and A.

Figure 6.1 Contiguous Boundary Nation-sets of Two Countries

Figure 6.1 shows two nations, called Y and A. It will be seen that both countries have two different nation-sets, and only a few of them are common to the two. In the same fashion, two offices located in the same city might have different sets of their counterparts with whom to interact. It is this nature of the organizational set that gives an organization its typical identity. Take two private schools18 in a town. The kind of students each attracts, the location of the school, and the private individuals or groups financially supporting the institution constitute each school’s network and determine its status in the society. It is these connections with the outside world that influence the inner workings of an organization. For the study of an organization, it is therefore essential to study not only its internal structure, but also its network of organizational relationships. It should also be stressed that organizations are also linked with other organizations via their own workers. Thus, workers in a factory may belong to different labour unions run by different political parties. Thus, political parties indirectly influence the functioning of the organization.

All these relationships—networks and interactions—change the sociology of the organization in question. An organizational structure is a formal blueprint. It gets changed by the social organization that develops when the blueprint is translated into a living organization.

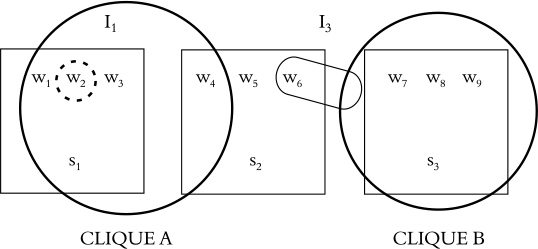

In this regard, a landmark study was carried out in the 1930s in the United States by Fritz Jules Roethlisberger and W. J. Dickson.19 This study was carried out in the Hawthorne Electric company under the leadership of Elton Mayo, where it uncovered the presence of a series of informally functioning primary groups, which bear an impact on the productivity of the company. Relations between non-supervisory occupational groups, such as connector wiremen and selector wiremen, wiremen and soldermen, and wiremen and soldermen in relation to truckers as well as to inspectors were investigated. Occupants of all these status functioning in the Bank Wiring Observation Room were ‘differentiated into five gradations, ranging from highest to lowest in the following order: inspectors, connector wiremen, selector wiremen, soldermen, and trucker’. Researchers collected data about informal activities such as playing games, participation in controversies about windows (to be kept open or closed), job trading, helping one another, and friendships and antagonisms. Based on the responses to these questions, sociograms were prepared. The authors came to the conclusion that:

- ‘these people were not integrated on the basis of occupation’; in other words, there were no occupational cliques.

- From all the areas covered for observation, it emerged that there existed two cliques, one of which was located towards the front of the room, the other towards the back.

- There were two cliques, but certain individuals remained away from them. However, the authors emphasize the point that it does not mean that there was no solidarity between the two cliques, or between the cliques and the outsiders. The main point was that this clique formation was a result of continuous interaction amongst the occupants of various statuses put together in a single work site, and was not the part of the official blueprint.

This study laid the foundation for the new sub-discipline of organizational behaviour in the general field of management. It emphasized the point that it is just not enough to know the formally spelt-out contours of an organization to diagnose any human relations problem that it might be facing. One needs to investigate the existence of informal groupings within an organization to attend to the key management problems.

To sum up, Hawthorne studies made four general conclusions:

- The aptitudes of individuals are imperfect predictors of job performance.

- Informal organization affects productivity. Discovering a group life among the workers, the studies showed that the relations that supervisors develop with workers tend to influence the manner in which the workers carry out instructions.

- Work-group norms affect productivity. Work groups unknowingly evolve norms of what is ‘a fair day’s work’.

- The workplace is a social system.20

Figure 6.2 suggests that any formal organization tends to develop an informal culture, which begins to have an impact on the functioning of the formal organization. Since this culture is the result of interaction between individuals occupying different positions, it remains unique to that organization only and is changed with the change of persons. It is the person-set that creates and nurtures the informal culture. Two similar offices of the same company, or of a government department, will have different informal cultures.

Figure 6.2 Internal Organization of the Group in the Bank Wiring Observation Room

Bureaucracy in Operation: The Pathology and Dysfunctions

Several scholars working on the functioning of bureaucracy have noted, however, that any concrete case of a bureaucratic organization departs from the ideal type as outlined by Weber. Such departures could be eufunctional, dysfunctional or non-functional for the organization. While we shall elaborate these concepts later in Chapter 8, it will be sufficient to mention that any conceived plan or structure is influenced by the people involved in it. It is found that any action taken in accordance with the stated intention might not lead to the same set of consequences. These consequences need not always be bad (dysfunctional) for the system concerned; they may be either helpful (eufunctional) or neutral in the sense that they neither contribute to its efficiency nor make it inefficient (non-functional). Scholars worried about the obstructive role of bureaucracy focused on the demonics21 of bureaucracy, which is part of the dynamics22 of the process inherent in the functioning of the system.

Merton argues that the ‘bold outlines’ of bureaucracy emphasize ‘the positive attainments and functions of bureaucratic organization’, and ‘almost wholly’ neglect the internal stresses and strains of such structures (1957: 197). The community at large, however, notices the ‘imperfections’ and regards the bureaucrat as a ‘horrid hybrid’. In this regard, Merton alludes to (i) the concept of ‘trained incapacity’ advanced by Veblen,23 (ii) Dew-ey’s24 notion of occupational psychoses, and (iii) Warnotte’s view of ‘professional deformation’.25

Trained incapacity refers to that state of affairs in which one’s abilities function as inadequacies or blind spots. Actions based upon training and skills which have been successfully applied in the past may result in inappropriate responses under changed conditions .... In general, one adopts the measures in keeping with one’s past training and, under new conditions which are not recognized as significantly different, the very soundness of the training may lead to the adoption of the wrong procedures. Again, in Burke’s26 almost echolalic phrase, ‘people may be unfitted by being fit in an unfit fitness’; their training may become an incapacity (ibid.: 198).27

As noted, the central emphasis of bureaucracy is on the discipline, understood in terms of strict adherence to rules and procedures so that there is no place for any personal considerations. The actions of the officers follow a predictable line.

If the bureaucracy is to operate successfully, it must attain a high degree of reliability of behaviour, an unusual degree of conformity with prescribed patterns of action …. Discipline can be effective only if the ideal patterns are buttressed by strong sentiments which entail devotion to one’s duties, a keen sense of limitation of one’s authority and competence, and methodical performance of routine activities.

All bureaucracies make arrangements to inculcate and reinforce these sentiments.

Merton argues that emphasis on these values causes ‘transference’ of these sentiments ‘from the aims of the organization onto the particular details of behaviour required by the rules’. In such circumstances, the means devised to attain the aims gain precedence and the officials tend to strictly adhere to them. The rules are the means, but in the enthusiasm for conformity to norms, the means gain an almost religious sanctity. Officers forget the intention behind the rules. When the aims are undermined and the means worshipped, the aims suffer. This is what Merton refers to as Displacement of Goals, where ‘an instrumental value becomes a terminal value’.

One can find myriad examples of this process in practically every organization. Lawrence J. Peter published a satirical book in collaboration with Raymond Hull—a playwright—in 1968 with the title The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong. The book opens with a very simple example of a school teacher who is fed up with bureaucratic procedures within his institution and responds to an advertisement for a similar job in another school.28 His application is returned by the advertisers as it was not sent by ‘registered post’, as required. The teacher then decided to retain his present job as he was convinced that all organizations are alike in terms of bureaucratic procedures. What this instance tells us is the fact that sticklers to rules disregard the intention behind a set procedure. Asking applicants to send applications by ‘registered post’ was meant to ensure that the application did not get lost in transit. But when an application has already reached the destination, the insistence on the procedure suggests that the means devised for ensuring receipt became a goal by itself for those who were in charge of receiving the applications. A good and eligible candidate was thus not considered for the job. This is an apt instance of displacement of goals.

Each one of us can furnish from personal experience several examples of rule worship that reach a level of absurdity. Some examples from the Indian setting are given below.

- There is a rule that any person going on a sabbatical has to furnish a certificate stating that ‘he is alive’ in order to claim the salary from the parent organization. A most quoted instance is that of a university teacher who had gone to USA on a sabbatical. Not knowing why his salary for the month of July was not paid to him while he received payments for subsequent months, he wrote to the Registrar of his university about the arrears. The Registrar wrote back saying that a medical certificate stating that he was alive in that month had not been received. Now, if the Registrar was writing to him in the month of, say, October, isn’t it logical to assume that the person was alive in July? Don’t his certificates for the later months cover the past in this regard? Can a person who is ‘alive’ in October be ‘dead’ in July? Obviously the Registrar was a worshipper of the rules, and did not apply his mind. He needed the certificate to complete the file by following the set procedure.

- An officer living very close to the airport suggested to his administrative officer that it would be economical for him to take a taxi for the airport rather than using the official car, as it would involve overtime payment to the driver, excessive use of fuel– from the office to his residence and then to the airport and back to the office. But it was denied on the ground that taxi fare could not be paid, as officers are paid on the basis of mileage at official rates, which is much less than the taxi fare. While rejecting the suggestion, what was ignored was that the use of an official car would incur greater costs than the taxi fare. It is interesting to note that the same officer was entitled to full taxi fare when an official vehicle was not available!

- A senior officer from Delhi was supposed to go to Pune. In the 1970s, there was no direct flight from Delhi to Pune and the passenger had to go via Mumbai, making a night halt. Since there was no ‘official work’ in Mumbai, the officer was denied any expenses for the Mumbai stopover, requiring the officer to spend his own money. The finance officer then came up with a solution that the officer concerned should ‘invent’ some official work in Mumbai to justify his claim! It could be a letter to be delivered to the chairman of his Board. In fact, any pretext would have done.

- It was reported in the newspapers of 30 January 2010 that an erring businessman (belonging to Uma Precision Limited) in Aurangabad was levied a penalty of

5,000 from the Commissioner (Appeals), which was paid. It was later discovered that a mistake had occurred as the earlier order had fixed a penalty of

5,000 from the Commissioner (Appeals), which was paid. It was later discovered that a mistake had occurred as the earlier order had fixed a penalty of  5011,

5011,  11 more than the amount remitted. In order to recover this small sum from the party, proceedings were initiated to challenge the order of the Commissioner (Appeals) and for that purpose to approach the Customs, Excise and Services Tax Appeallate Tribunal (CESTAT) in Mumbai. For this purpose, a superintendent-level officer from Aurangabad visited Mumbai on at least two occasions—once while filing the case with CESTAT and the second time on the day of hearing. The officer was entitled to second-class air-conditioned train fare and food allowance. The entire exercise took three years and a good amount of paper work involving several hours of office time. But after all this, CES-TAT turned down the prayer. The government spent nearly

11 more than the amount remitted. In order to recover this small sum from the party, proceedings were initiated to challenge the order of the Commissioner (Appeals) and for that purpose to approach the Customs, Excise and Services Tax Appeallate Tribunal (CESTAT) in Mumbai. For this purpose, a superintendent-level officer from Aurangabad visited Mumbai on at least two occasions—once while filing the case with CESTAT and the second time on the day of hearing. The officer was entitled to second-class air-conditioned train fare and food allowance. The entire exercise took three years and a good amount of paper work involving several hours of office time. But after all this, CES-TAT turned down the prayer. The government spent nearly  3,000 and three years to recover the paltry sum of

3,000 and three years to recover the paltry sum of  11 from the erring businessman, but failed in its mission. This shows how rule worship leads to inefficiency and financial loss. It was not worth the exercise for

11 from the erring businessman, but failed in its mission. This shows how rule worship leads to inefficiency and financial loss. It was not worth the exercise for  11. The officer concerned should have applied his discretion and closed the file.

11. The officer concerned should have applied his discretion and closed the file.

All these instances hint at the unimaginative use or interpretations of the rule. The intention to prevent misuse and economize office expenses is disregarded and obstacles created in the smooth discharge of duties. Such examples abound when a common man approaches a governmental bureaucracy.

Peter derived a more general principle from similar examples for his proposed ‘Science of Hierarchiology’. The Peter Principle says that in any hierarchy, an employee tends to rise to his or her level of incompetence. Employees who are perfectly competent at one level are automatically promoted regardless of their ability to do the job they are promoted to, or whether they wish to be promoted. Such people attain their level of incompetence with the rise in the hierarchy.

Peter argued that in due course of time, most management positions within a bureaucracyare filled by those who are incompetent. They attain superior positions by being rather good at their current position, but are rendered incompetent at the higher level. This is also the case where promotions are given on the basis of seniority and not competence. In the Indian setting, where most government appointments are life-long, that is, until the age of retirement—a person feels secure in his or her job after the period of probation, and awaits promotion on the basis of seniority and not the competence needed for handling upper-end jobs. Such individuals are generally doomed to fail, but they cannot be removed or downgraded. That is why seniority-based promotions in the universities in India have brought incompetence to the top academic positions. Peter says that senior officials mask their incompetence using various tricks, by using giant desks, inventing incomprehensible acronyms, blaming others for failure, sycophancy, and various other ways of cheating. Reaching one’s level of incompetence is also an illustration of the phenomenon of ‘trained incapacity’ mentioned earlier.

There is another dimension of the bureaucratic rigmarole that Parkinson has pointed out, which is popularly known as Parkinson’s Law.29 He also developed a ‘coefficient of inefficiency’. From his own experience as a bureaucrat, he came to the conclusion that there is no relation between the number of officials and the quantity of work in a particular office. He coined the famous phrase: ‘Work expands so as to fill the time available for its expansion’. It is generally the case that an official wants to multiply his subordinates, and not the rivals, and the officials make work for each other. There are several instances of committees and commissions set up by the government to give reports within a stipulated time, but in most cases the tenure of such offices is extended ad nauseam. Parkinson gave the example of the expansion of the foreign office of the British government at a time when its colonial regime was constantly shrinking.

The assumption that strict adherence to rules increases efficiency has also been challenged by certain actions taken in the public sphere in India. Indian political culture evolved several ways of lodging its protest. The most innovative way was to announce a strike following the work-to-rule strategy. In the 1970s, the Trade Union of Railway employees resorted to such a strategy and caused a total disruption of services. Invoking Weber, one should have raised the query: how can ‘work-to-rule’ lead to inefficiency? Weber’s ideal type suggests that rigorous adherence to rules is necessary for the efficient functioning of the bureaucracy. Obviously, the union leaders and railway employees were not challenging Weber, but were hinting at the work norms evolved by them, which facilitated their work and improved their efficiency. In other words, such strikes were a reminder to the superiors that there are deficiencies in the rules, and that departure from them was necessary to attain the goals. One area of contradiction revealed by that strike was in the conflicting goals and rules of two of its important departments, namely traffic and security. The primary goal of the traffic department was: come what may, trains must run punctually. The security department, on the other hand, insisted: come what may, proper security precautions—as prescribed—must be taken, even if delay occurs in the running of the trains. Since the trains before the strike were mostly running on time, it was obvious that some of the security procedures must have been bypassed; and during the strike, strict observance of these procedures resulted in enormous delays, and brought the railways to a halt. Political analysts and even social scientists did not receive this message from the striking employees, who thus unwittingly put Weber in the dock.

In terms of research, this seems to be a grey area; research on the role of rules and procedures invites attention.

Merton put forth the view that over-conformity in a bureaucratic organization can be traced to structural sources.

The process may be briefly recapitulated. (1) An effective bureaucracy demands reliability of response and strict devotion to regulations. (2) Such devotion to the rules leads to their transformation into absolutes; they are no longer conceived as relative to a set of purposes. (3) This interferes with ready adaptation under special conditions not clearly envisaged by those who drew up the general rules. (4) Thus, the very elements which conduce toward efficiency in general produce inefficiency in specific instances. Full realization of the inadequacy is seldom attained by members of the group who have not divorced themselves from the meanings which the rules have for them. These rules in time become symbolic in cast, rather than strictly utilitarian (1957: 200).

Bureaucracy and Nation-Building: A Post script

Bureaucracy assumed additional importance in the context of developing countries. While the western scholarship focussed on particular formal organizations either within the government or in the corporate sector to witness the functioning of the bureaucracy and relating it to efficiency and effectiveness, bureaucracy was, and is, viewed in the context of the countries of the developing world as the executive wing of the governments—colonial governments, monarchies, and dictatorial regimes. The word bureaucracy, in such contexts, refers to the top bureaucrats who run the affairs of the government.

In the criticism of the bureaucracy in developing countries, the focus is not so much on the internal working of the system as on the attitude of the top bureaucrats in managing the affairs of the state and in maintaining law and order. These bureaucracies were trained during colonial rule to keep the ‘subjects’ under control, and therefore, created rules and procedures to obstruct the work of the common man. The rule structure was created on the premise of distrust: Distrust everybody unless and until he proves trustworthy. Bureaucracy in this sense was seen as anti-people and the bureaucrat was seen as an agent of the ruler, and a loyalist of the regime. In India, the British ruled the country first by a cadre trained in England for the Indian Civil Service (ICS), which initially consisted only of the British nationals under whom the Indians worked on a hierarchy of subordinate positions. With the attainment of independence from British rule, the Government replaced the ICS with the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and other ancillary services. Gradually, the ICS was weaned out with the retirement of the officers. The early IAS officers, however, treated the ICS bosses as role models, and followed their style of functioning despite the redefinition of their roles with additional charges.

Although law and order continues to be the responsibility of governmental bureaucracy, they were charged with the additional responsibility of participating in the task of social and economic development and in nation-building. During the British regime, the bureaucrats were treated as the ‘mai-baap’ (parents) of the people, but in the changed scenario of a democratic polity, they had to redefine their role as ‘servants of the people’. Ambivalence was quite understandably apparent amongst those bureaucrats whom India inherited from the British Raj. For them, it was a period of transition. Recalling the past behaviour, common men treated the oldies in the bureaucracy with certain amount of disdain, regarding them as representatives of the Raj.

However, credit must be given to the Indian bureaucracy, which tried hard to adjust to the new milieu. Commenting on the performance of the Indian bureaucracy in the 1960s, S. C. Dube acknowledged that ‘Despite the pathologies and dysfunctions from which Indian bureaucracy–as it was inherited from the British rule–has suffered, it has made positive contribution towards achieving developmental goals of independent India’ (Dube, 1966: 348).

He had a ‘word of honest praise for its role in facing horrendous situations efficiently in maintaining a degree of national cohesion, and in putting on its feet a nationwide economic development’. But he also pointed many of its shortcomings. These are listed below:

- In the area of economic development the Indian bureaucracy initially remained hesitant and unsure. As a result, its standard of performance and levels of achievements have not been ‘equal to its reputation’.

- The structure and ethos of the bureaucracy was suited more for the maintenance of law and order than for massive nation-building.

- Bureaucracy’s ‘adaptation to the emerging milieu has been beset with organizational incompatibilities, psychological resistances, and value conflicts’.

- ‘It suffers from certain lags and finds itself unable to grapple with the new challenges with ease and confidence. The bureaucrat had difficulties working with technocrats on equal terms, as he was trained to work as a superior rather than as a colleague’. The paternal–authoritarian approach has so mentally conditioned him that he cannot run partnership projects in their intended and overtly articulated spirit.

A bureaucrat is trained as a generalist so he can take up any assignment. In the Indian bureaucracy, transfers are made from one ministry to another and the officer is expected to perform equally well. Of course, some bureaucrats tend to develop a certain expertise in the area of their liking and manage to spend more time in that particular department. However, the programmes of development require specialist knowledge in planning, execution, and evaluation. For this, technocrats are recruited on par with senior bureaucrats. This gives rise to conflicts, where the generalist-administrator points out the lack of administrative acumen in the technocrat and the technocrat highlights the lack of technical competence in the bureaucrat. India’s development plans faced these difficulties. Dube was a witness to this process as he was inducted to assist in the massive programme of community development as a social scientist. Thus, what he has written about the bureaucracy is based on his ‘participant observation’.

Apart from the tensions between the technocrat and the bureaucrat, the latter also had to work under multiple political pressures, which put his efficiency to severe test. Politicians serving as ministers had to work to please and satisfy the public on the one hand, and depend on the bureaucrats working under them to meet the demands of the electorate. With a long and assured tenure the bureaucrats carry the bag of experience where politicians are like the ‘birds of passage’ who come and go with every election. It is the bureaucracy that ensures the continuity of administration and is thus, indispensable, despite its shortcomings. In such circumstances, the bureaucracy is characterized by the following symptoms, according to Dube:

- Failure to take decisions at the appropriate level

- Passing the buck

- Roping in others in decision-making

- Making unequivocal recommendations30

- Anticipating what the boss wants and acting accordingly, although he knows what can be done

- Rationalization of failures

- Underplaying the essentials and magnifying the grandiose

- Outright sycophancy

Dube highlights the point that

old procedures are cumbersome and ponderous and the interminable journeys of files and cases from level to level, and from department to department, are necessarily time consuming, and at the same time new norms calling for speed and despatch are still amorphous and, therefore, uncertain. (Dube, 1966: 343–51).

Dube wrote all this more than 30 years ago. There have been several changes and improvements in the bureaucratic structure and in the personnel. Introduction of computers and other features of information technology has helped in clearing several bottlenecks. A majority of bureaucrats are those who are young and who have not seen the colonial rule or early phases of Indian bureaucracy in independent India. Their orientation and training are geared to meet the new requirements. They are also exposed to the outer world and to the processes of globalization. Several examples of wellmotivated officers trying to improve governance are frequently reported,31 and yet a Hong Kong-based survey published in Indian newspapers on 4 June 2009 says that ‘Indian Babus are the Worst in Asia’ (see Mail Today, Hindustan Times, or Times of India, 4 June 2009). Even the new government has promised to improve governance, and drive out the corruption that is rampant in government offices at all levels, which is an admission of the pathology that exists in the Indian bureaucracy. Corruption is a subject for some serious research; its structural roots need to be investigated to cleanse the system.32

One point is certain, that is, bureaucracy continues to be a necessary evil. It departs in all circumstances from the Weberian model and yet bureaucracy is essential for managing large-scale organizations and the affairs of the state.

Alliances, Coalitions, and Networks

We have noted that formal groups also allow the formation of informal groups within them. Since these groups are informal, they do not figure in the formal structure. But they inevitably emerge in all the formal groups—recent or old—and significantly influence their functioning. It is the identification of such informal groups within a formal group and the manner of their functioning that has been an area of sociological research, popularly covered by the term ‘organizational behaviour’. The findings of such research have greatly contributed to the science of management. Informal groups also operate in community settings.

Short-lived Alliances at the Level of Individuals

This distinction between permanent groups and short-lived (ephemeral) alliances is important. Some students of village India focused on factionalism and studied relatively permanent factions, though they were informal in character.

While studying group dynamics in an Indian village, anthropologist Oscar Lewis33 talked of permanent factions. He defined them as ‘small cohesive groups within castes which are locus of power and decision-making’ (1958: 195). Studies in other villages revealed that such groups exist with membership drawn from a number of castes. Also, new alliances are formed for meeting exigencies in which people join from different factions. People get divided on an issue, and those following a common line support each other. But on yet another issue, the supporters or opposers may combine differently. Thus, an individual may simultaneously belong to two different short-lived, that is, ephemeral alliances which may cut across caste lines or even family lines. The latter phenomenon suggests that such alliances are goal specific and people cross their boundaries. Of course, where the factions are antagonistic such temporal floor-crossing might not occur.34

Alliances occur both at the level of individuals who join to form a short-lived group to meet a particular exigency, and at the level of groups. The best example of this process is offered by the emerging Indian political system.

For a number of years after the attainment of independence, our political system was described as a ‘One-party Dominant System’. The Congress party at that time was such a dominant party. Those who felt frustrated within the party moved out to form rival political parties. But being small and having a limited following, they were initially unable to replace the ruling group. And the larger party had favourable conditions within it to split into factions, which were designated as ruling and dissident groups. Power alternated between them and they became the functional equivalent of a two-party system.

With the flowering of a democratic culture, the parties emerging outside of the Congress umbrella grew in strength, either as regional parties or national parties. These replaced the ‘One-party Dominant System’ by a new format of coalitions, called alliances. Since the last decades of the twentieth century, Indian politics has entered the coalition era.

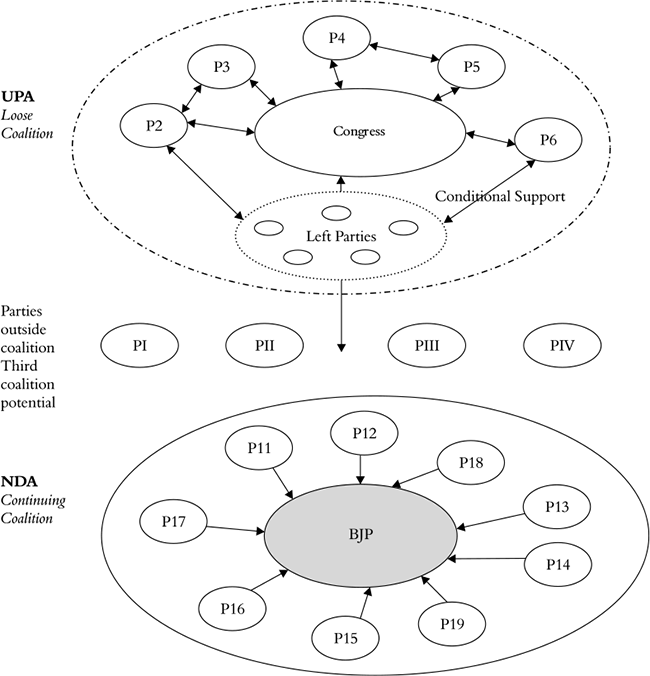

There are two major alliances at work, namely, National Democratic Alliance (NDA) and United Progressive Alliance (UPA). Each of these alliances consists of a number of political parties. While the parties entering such alliances continue to maintain their individual identities, the Alliance35 itself functions as a supra-party group based on a Common Minimum Programme (CMP).

The membership of these alliances keeps fluctuating, and the individual parties maintain their individual identities. The coalition politics had earlier seen the merger of various non-Congress parties in a bid to form a common front and a common party. Bhartiya Jan Sangh—the key rival party—also joined this new outfit. But this new party called Janata Party36 also failed to contain all the merged parties within its fold, and the Jan Sangh constituent came out of it to form a new party with the old membership, and named it Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP).37

At the time of the 1999 general elections, the BJP took lead in creating an alliance and decided to fight the elections under this umbrella. This was named NDA. It was joined by more than 20 parties who agreed on the CMP and developed a seat sharing arrangement.

In the next general elections for the parliament, held after five years, NDA fought the elections with a similar strategy but could not get a winning majority. Its rival, the Congress Party, also did not get a clear mandate, and therefore decided to go for a post-election coalition with a CMP, and endorsed the participation of a number of left-leaning and self-proclaimed ‘secular’ parties. This coalition was named UPA.

To recapitulate

A coalition is a strategic alliance formation between organizations. following are the key characteristics of a coalition:

- It is an interacting group of groups or of individuals

- It is deliberately constructed by the participating groups for a specific purpose with a Common Minimum Programme (CMP). In the Indian case, both the political coalitions—Congress-led UPA and BJP-led NDA—agreed to work together on the basis of the CMP.

- Such a coalition is somewhat independent of the structures of participating formal organizations.

- Also, it has very little of a formal internal structure.

- It is issue-oriented, as expressed in its CMP. And the participating units have the option of quitting, as also of criticizing individual coalition partners on their actions that are not part of the CMP.

Networks

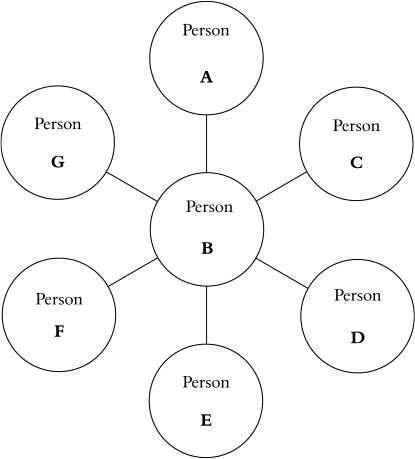

Networks are different from groups and alliances. Since an individual interacts with a number of people who belong to different groups, all such groups are part of that individual’s network. In this sense, no two individuals have the same network composition. In a network, each nodal point has its own range of network ties. Each participant in a network is a centre for his/her network, which spreads like a ‘snowball’. Thus, each person in a particular network has his/her own range of interconnecting links, part of which may be common with any other member of the network.

This is true even in the context of a family. Each member of the family has his or her social network, which is unique in the sense that it cannot be the same even of two brothers or two sisters. While members of the family are linked to each other, their outside contacts cannot be the same. Upon marriage, the daughter of the family enters a new family, that of her husband, and creates extensions of her network in that direction; another daughter of the family will similarly have extensions on the side of her husband. Members of their parental family will surely have relationships with the members of these networks, but the type of relationship will differ: the daughter will assume the role of a wife or a daughter-in-law, or a sister-in-law; but her father will be recognized in her family of marriage as the father-of-the-son’s wife, or father-of-brother’s wife. The status differential influences the nature of participation in any given network. The daughter might also have in her network her friends, or colleagues in the office (if she is working), or co-artists (if she is an artist or an actor), but none of these would figure in the network of her own sister or mother.

With the arrival of information technology, new opportunities have been opened up for social networking. The spread of computer culture and the availability of mobile phones means that people are constantly engaged in verbal interactions and are keeping in touch with each other even when they are physically at great distances from one another. The hurdles of geography are minimized by the information highways.

But social networking is used by the new generation in a different sense altogether. Shiv Visvanathan38 admits that as ‘an old fashioned sociologist one would think it dealt with the excitement around social capital, trust, about entrepreneurship that leverages ties and old affinities’. But this term is part of a new technological patio, a jargon, and conveys a different meaning altogether. ‘As a public domain, says Visvanathan, ‘social networking is a new fabric of relationships which has still to find its theorists ....’ Somewhat sarcastically, Visvanathan admits that this networking has different sets of rituals. ‘Earlier you met and chatted, now you just type. Hugs and satire have been replaced by virtual poke and hug-me applications … Only time could dictate the character of a friend ....’ Online quizzes and polls now define a social character.

(Source: Facebook and Twitter)

Way back in 1997, the first social networking site was created and was named sixdegrees. com. It disappeared in the year 2000. Three years later, in March 2003, another site, Friendster, was launched. Then came MySpace in August 2003, followed by Orkut in January 2004, and Facebook in February of the same year. This new site has become the most popular and the biggest social networking site, with more than 300 million users throughout the world by September 2009; it is claimed that there are on an average 217 friends for a Facebook user. In August 2014, India had 100 million alive users of Facebook. It is the second country after USA. There are 84 million users in India who access the networking site from their mobile phones.

Tweeting is yet another format for networking. Through it, messages reach much faster and throughout the world. Political and corporate house battles are now fought with the help of these innovations, which have changed the very meaning of privacy and secrecy. There are several networking sites in operation. One source lists as many as 205 such sites with varying membership and worldwide spread.

This is illustrated in Figure 6.3.