CHAPTER 20

Fashioning the Future

Why Future Studies?

When the world was fast approaching the threshold of the twenty-first century, it was gripped with a feeling that the present century would soon become part of the past.

The impending departure of the twentieth century invoked scholars to shift their orientation from the present to the future. There was increasing scholarly activity in this new terrain. From the earlier engagement (i) in unravelling the mysteries of the unknown past and creating a credible history of our ancestry, and (ii) investigating the cultural and social diversities of the present and planning strategies to overcome development deficits, many scholars became interested in questions concerning ‘what will be’ or ‘what should be’ our future—the future of the globe and of the individual societies on earth. They began focusing on the future.

The anticipation of the year 2000 prompted a three-fold research activity: (i) reviewing the past to gauge the trends of change and learn the lessons from past experience to improve performance by modifying or changing the strategy of development; (ii) predicting the future shape of the globe in the light of emerging trends; and (iii) constructing desirable images of the future.

In his 1989 essay titled The End of History,1 Francis Fukuyama predicted the fall of the Berlin wall and said that large-scale wars over fundamental values would no longer arise, since all prior contradictions are resolved and all human needs satisfied. In a way, he propounded the concept of endism.

While the Berlin Wall did fall and the Soviet Block did collapse, the world has, however, not come to an end. But the fear of such an end has begun to haunt us. The crisis of climate change has again promoted futuristic studies relative to the life of earth itself. People are prognosticating that the end is not far. The film 2012 sent shock waves. Some biosphere experts are predicting that the world will come to an end within a century. Global warming is being caused both by the emission of carbon dioxide from the earth and the fast depletion of the thermosphere that protects the earth from the direct assault of the sun’s rays. A solar tsunami is being predicted. Concern for the future is becoming all too prominent.

There is in evidence a concern and a will to fashion a future of our liking by stemming the unwanted trends and initiating desirable ones. The fast disappearing past and prospects of an indeterminate future spurred new lines of investigation. No one would wish to enter an uncertain and unknown future; certainly not the undesirable future.

The future began to attract not only philosophers and social activists and leaders, but also the various empirical sciences, natural and social. Social sciences as we know them were late to arrive on the academic scene, and their candidature as science continues to be debatable even today. It is argued that an academic endeavour qualifies to be a science only when it is able to predict with considerable accuracy. That is why questions were, and still are, raised as to whether sociology—or for that matter, any other social science—qualifies to be a science.

It is important to understand what is meant by prediction. All societies and all thinking men indulge in the speculative arena of the future. The astrologers and astronomers of different schools developed their techniques of predictions. Our calendars are based on such calculations and we are told in advance about the phases of the moon, about eclipses, and other episodes that have a predictable recurrence. We also have the so-called astrologers, palmists, Tarot card readers and numerologists who make predictions in daily newspapers. People approach them to learn about their own future or to know whether their dreams will come true. But these are always questioned. One can compare the predictions for a single day for a single zodiac sign in different newspapers to find out how conflicting the predictions are. It is through acts of commission and omission that the news about predictions diffuses. Generally, people omit those predictions which do not come through and relay those that somehow correspond to their expectations. Those who have faith in astrology attribute failure in prediction to the calibre of the astrologer and not to the so-called science of astrology.

Sciences, on the other hand, make predictions about recurrent behaviour, based on systematic observation and exacting experimentation. They also extrapolate the prevailing statistical trends to move into the future. There are several areas that have been beyond observations and, therefore, the predictions relative to them are at best hypotheses. From this standpoint, different sciences have different powers of prediction.

Social sciences have, over the years, developed skills both in theorizing and investigating with methodological sophistry. This has paved the way for a new science of futurology. Future Studies has become a new academic specialty built on the cutting edges of various social science disciplines.

Key Concerns regarding the Future of Cultures

Future Studies is a field that deals with the unknown. Its concern is, says Masini, ‘… not so much to be able to predict specific events but to indicate alternative paths to future’ (Masini, 1993: 1). Gaston Berger, a French Future thinker, emphasized the need for future thinking through the simile of a speeding car. He said that when you ride the car that runs faster, you need stronger headlights to avoid pitfalls and forestall the danger of the car colliding with any obstructions.

How do we approach the question about the future of cultures? Perhaps it may be better to ask: why are we concerned about the future of culture? Is it because we are interested in knowing the shape of things to come? Or, are we worried about the fate of cultures? The latter question implies that cultures, that is, traditional cultures, will vanish under the onslaught of modernizing influences brought about by rapidly advancing science and technology.

There are people who are worried about the manner in which the present is shaping. The present social crisis is attributed to the wrong prescriptions suggested by outside experts. They glorify the past and wish to change the course of society’s functioning to enable a return to the traditional shell. This is one version of the strategy for fashioning the future—to make the future resemble the past of the society. There are others who suggest, for example, that the present is split into two unequal parts—the rich and the poor, the modern and the traditional, the rural and the urban. Indian society is, according to them, stratified into India and Bharat, and they want the country to be the latter, thereby decrying the modern, industrial, literate section of this vast country. For them, the real India is rural India. This might either mean a return to the past, or a clarion call to take effective steps to transform Bharat into India. But if India represents a departure from tradition, what shall be the image of Bharat? The ambivalence in such protestations is evident.

The key concern is expressed in questions such as these: Will economic and technological progress destroy the cultural diversity and bastardize our cultures? Will we witness a return of intolerant chauvinism that would make cultures retreat into their shells? Will there be a judicious fit between the old and the new? Where are we going? Can we change the course? These are all related to the domain of the future. Social scientists, who began addressing these and similar questions, are taking Footsteps into the Future.2

It may be said that the future shift in intellectual orientation is, in a way, linked to the societal commitment to development. Begun as a process of decolonization—which was negative in its orientation—development became, in the countries of the so-called Third World, an ideology for rapid planned and directed culture change. Newly independent nations began to move in a predetermined direction with defined goals and targets and preconceived strategies. The planners and administrators took on the role of fashioners of the future. Developing countries got involved in the revolution of rising expectations. The West served as the reference group and even proxied many decisions. Westernization and modernization became synonyms of development.

However, expectations have led to frustrations because of the mixed gains of development. It was a mistake, it is now realized to blindly imitate the West. Development did not succeed in homogenizing the world. Traditions did not, however, oblige their obituary writers. The process of development, in fact, created greater disparities. It broadened the divide between the rich and the poor, and falsified many tenets of modernization. Alongside of modernization grew the process of revival and resurgence of tradition and even of religious fundamentalism. The new forces ushered in by the revolution in the field of Information Technology broke the walls of insularity and opened out fresh apertures to link one society with the other. Today the world is described as a global village, fulfilling the prediction of Marshal McLuhan.

Those who take a pessimistic view of the future of cultures feel that all cultures will lose their pristinity through hybridization and will be reduced to their ornamental roles. The optimists, on the other hand, feel that cultural communities will plunge into their indigenous roots and come up with their own recipes for survival and advancement.

The narrow specialists of culture—the so-called culture people such as prehistorians, archaeologists, the traditionalists and the fundamentalists—are at best preservationists. They have mostly engaged themselves in the rediscovery of the past and its glorification through sheer adumbrationism. They are worried about the dilapidation of physical structures (such as monuments) because of their gross neglect, or about the damages done to them by natural hazards or irresponsible human actions. Their guiding motto is to preserve, protect, and renovate. Change does not exist in their vocabulary. Culture, to them, is a mere museum of tradition.

The first generation of anthropologists regarded all forms of culture contacts with the outside world as disruptive of the ‘primitive’ way of life and, therefore, wanted the primitives to maintain their status quo; they were dubbed as advocates of anthropological zoos. Their protests against culture contacts notwithstanding, what has happened even with regard to tribal groups the world over is quite astonishing: no tribe has remained completely insulated from the outside world, maintaining its pristine, exotic existence; and many of the material cultural traits of various non-Western societies have travelled far and wide to become showpieces in modern drawing rooms. There is a discernible trend towards what may be called the ‘museumization’ of drawing rooms in so-called modern societies.

Cultural specialists, including many anthropologists, hold the view that the cultures of developing countries have been the victims of development. The development specialists, on the other hand, have attributed all the failures of planned development programmes to culture; they regard culture as an obstacle to development.

Anthropological literature exhibits a peculiar ambivalence towards change. It is significant to note that while ethnological theories have focused on evolution and diffusion, earlier ethnographies of particular tribal groups did not assign any space to the description and analysis of change occurring in them. These monographs were written in the idiom of the eternal present; tribal communities were regarded by them as no-change or slow-change societies. It is only in the late 1940s that some anthropologists began ending their ethnographies with a postscript on change. Fuller studies of change in tribal and village communities are rather recent, started somewhere in the mid-1950s when newly independent countries initiated an era of planned and directed socio- cultural change. The term ‘Directed Culture Change’ was evolved to signify exogenous changes—changes brought from without. The analysts of directed culture change either attributed costly failures of any innovation to the neglect of the cultural factor, or impressed upon the planners and administrators the need for a holistic view of culture and an assessment of the ramifying influence of change brought about in a particular sector of social life.

Interestingly enough, whatever we have by way of literature on the culture-development interface3 is mainly anecdotal. There are narrations of (mainly) failures, highlighting the importance of cultural factors. But no guidelines exist as to how to plan a change that will not meet with failure. Wisdom in hindsight can only provide an awareness of the importance of cultural variables, but cannot equip a social scientist to offer readymade recipes to planners of change. Similarly, planners have also not yet improved their planning protocol to incorporate the cultural variable in the planning process to ensure that it will not be a hindrance.

Future Studies

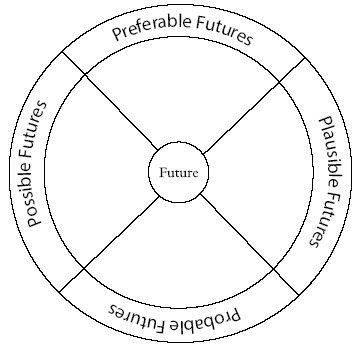

It needs to be emphasized that worrying about the future is only human. Scholars have built utopias. Scholars still feel the need to know about the past and the present as a basis for looking into the future, but are worried about the fact that our desires and our fears about the future often do not correspond to our knowledge and even contradict it. The dilemma is in terms of the possibles and the desirables. Futurists also believe that the only space on which humans can have an impact is the future (Masini, 1993: 7). Masini quotes Antonio Alonso Concheiro to the effect that the past belongs to memory, the present to action, and the future to imagination and will. Futurists also believe that there is not one future, but many possible futures. In other words, we have to think of future in plural terms. If we plan for a single future for the entire human community, according to our wishes and values, it will then amount to colonizing the future. Masini used these driving principles to suggest that the future can be seen in terms of the Possible, the Probable, the Plausible, and the Preferable. See Figure 20.1.

In the writings of others, there is also a mention of the inevitable future, closer to what Masini has called the plausible future. But inevitable is the one that is most likely to occur, come what may. Population explosion, or changes in the age pyramid, for example, will belong to this category. Malthus said long ago that while food supplies increase at the arithmetic rate, population follows the principle of geometric progression. It can safely be said that the population figure of tomorrow will definitely be larger than what it is today. India’s population today—crossing one billion—was at one time the size of the entire population on planet Earth. But now it is less than one-fifth of the world's total. In the future, despite all the efforts towards family planning, there will be more than six billion people inhabiting the earth. There may be differences in what the exact figure in the year 2025 or 2030; it is sure that it would be much higher than the present total. An UN study said that the global population would swell to 9.6 billion in 2050. Similarly, thanks to human intervention and successes in the field of medicine, it is inevitable that people will live longer and thus, the size of our senior citizenry will go on increasing. It is estimated that the number of people aged 60 and above would catapult from 841 million now to two billion in 2050 and nearly three billion in 2100. One can also predict that this single change in the demographic profile will change the configuration of the burden of disease.

Figure 20.1 The Terms of Future Studies

Table 20.1 Population Growth in Terms of Billions.

Year |

Number of Years for Adding Another Billion |

Billion |

|---|---|---|

1800 |

1 |

|

1927 |

127 |

2 |

1960 |

33 |

3 |

1974 |

14 |

4 |

1987 |

13 |

5 |

1999 |

12 |

6 |

2011 |

12 |

7 |

2025 |

14 |

8 |

2043 |

18 |

9 |

2083 |

40 |

10 |

Table 20.1 summarizes the increasingly lesser number of years in adding another billion people. The world population was one billion in 1800, it took 127 years to double. The two billion world population has become 7 billion in 2011, and by the year 2043, it will be 9 billion. This is an enormous growth despite all efforts at family planning and birth control. This is a factor beyond our control and is almost inevitable unless the world experiences a major catastrophe that annihilates large chunk of people—a deadly disease, a nuclear onslaught, or a solar tsunami.

The Contributions of Alvin Toffler

Regarded as the most influential futurist, Alvin Toffler is credited to have woken us up from our slumber of complacence and given us future shocks through his writings since the 1970s. It is important to pay tribute to this sociologist-cum-journalist for his contributions to future thinking.

Published in 1970, Future Shock, his first book on the future, became an instant best seller. Toffler summarized his thesis thus: by the end of the twentieth century, millions of people will experience an abrupt collision with the future. Affluent, educated citizens of the world’s technically advanced nations will fall victim to tomorrow’s most menacing malady: the disease of change. Unable to keep up with the supercharged pace of change, many people will plunge into Future Shock. He called the impact of the high pace of change the accelerative thrust, for which the entire world was totally unprepared. He pointed out the dangers caused by tampering with the chemical and biological stability of the human race, and emphasized the need for both individuals and societies to learn to adapt and manage the processes of rapid social and technological change.

The book, however, not only warns the readers about the impending crisis, but also offers strategies for survival. He devoted chapters on coping with tomorrow, education in the future tense, taming technology and the strategy of social futurism. The need of the hour, according to Toffler, was to develop the individual’s ability to cope to be able to adapt to continual change in the economy and society. Assumptions, projections, images of futures would need to become integral parts of every individual’s learning experience.

He criticized the education system for facing backwards towards a dying system, rather than looking forward to the emerging social scenario. Regarding technology, Toffler put forward the view that a ‘powerful strategy in the battle to prevent mass future shock ... involves the conscious regulation of scientific advance’. Overall, he recommended serious efforts to anticipate the likely consequences of technological developments and to prepare ourselves to confront them. Technology cannot be permitted to rampage through society. In the final chapter on the strategy of social futurism, Toffler proposed some social innovations to ameliorate change. In this context, he emphasized the need for developing a sensitive system of social indicators geared to measuring the achievement of social and cultural goals. This he regarded as an absolute pre-requisite for post-technocratic planning and change management.

Following Future Shock, Toffler came out with another book titled The Third Wave (1980), in which he divided human history into three waves:

- The First Wave of massive change was caused by the Agrarian Revolution, which encouraged many hunting and food-gathering cultures to adopt the new system of domestication of plants and animals.

- The Second Wave was manifested in terms of the Industrial Revolution. Toffler writes: ‘The Second Wave Society is industrial and based on mass production, mass distribution, mass consumption, mass education, mass media, mass recreation, mass entertainment, and weapons of mass destruction. You combine those things with standardization, centralization, concentration, and synchronization, and you wind up with a style of organization we call bureaucracy.’ The main components of the Second Wave society are nuclear family, factory-type education system and the corporation.

- The Third Wave in Toffler’s formulation is bringing about the post-industrial society.

Toffler’s allusion to the three great civilizations as products of the three waves does not suggest that they occur in sequence, one after the other, in any given culture, as was implicit in the writings of unilinear evolutionists. There are some societies that are still going through the agricultural revolutionary phase; there are others where the agricultural and industrial phases co-exist; similarly, there is co-existence of industrial and information civilizations in many.

The post-industrial society, in Toffler’s formulation, exhibits diversity in lifestyles. Bureaucracies are being replaced by Ad-hocracies4 which adapt quickly to changes. Information is a new material for workers, who are renamed cognitarians in place of proletarians. Mass customization now offers the possibility of cheap and personalized production. In this phase, the gap between producer and consumer narrows. The producer has also become the consumer, and for such a configuration, Toffler coined the term ‘Prosumers’. Prosuming entails a third job where the corporations outsource their labour not to other countries, but to the unpaid consumer. When we do our own banking through ATM instead of a teller or trace our own postal packages on the Internet instead of relying on the courier, we play the role of a prosumer. People in aging societies have begun using new medical technologies for self-diagnosis, such as checking diabetes or even analysing stool and urine. In fact, many are self-administering therapies. This is significantly changing the profile of the health industry.

Toffler’s books can be seen as conceptualizations of the emerging trends and documentation of the consequences of changing technologies on the social, economic, and political lives of societies. Based on these trends, Toffler has attempted prognostications. In fact, he alerts his readers that the continuation of present trends is leading us to the future, which would be startlingly different from the present and would pose different sets of problems for human existence.

Following Third Wave, Toffler came out again, after a decade’s cogitation, with another book named Power Shift. Rather than elaborately summarizing this highly readable book of 580 pages, we excerpt its main thrust from the blurb:

While headlines today focus on the tremendous shifts of power at the global level, Toffler says that equally significant, but largely unnoticed, shifts of power are taking place in the intimate, everyday world we inhabit—the world of super-markets and hospitals, banks and business offices, television or telephones. Power shifts are transforming finance, politics, and the media, together creating a now radically different society. The very nature of power is changing …. Toffler, for the first time, defines this entire new system of wealth creation.

Toffler believes that wealth today is created (i) everywhere (globally), (ii) nowhere (cyberspace), and (iii) out there (outer space). Global positioning satellites allow just-in-time (JIT) productivity in all fields, be it air-traffic control, weather forecasts to assist agriculture, or use of credit cards or the ATM machines. Toffler also predicted the inauguration of the paperless office and the prospect of human cloning.

Toffler identified three sources of power, namely violence, wealth and knowledge. Viewing this in a time frame, one could say that in the beginning of human civilization, it was violence, or muscle power, that was the only source of power; later, accumulation of wealth became the source of additional power, and in due course of time, knowledge began investing power. Toffler says that

the sword or muscle, the jewel or money, and mirror or mind together form a single interactive system. Under certain conditions each can be converted into the other. A gun can get you money or can force secret information from the lips of a victim. Money can buy you information—or a gun. Information can be used to increase either the money available to you … or to multiply the force at your command … (Toffler, 1990: 13).

Muscle, money, and mind are thus the sources of power. Power shift implies that it is mind—that is, knowledge—that is becoming the storehouse of power. This is what we mean by the emergence of the knowledge society. The key premise of the sociology of knowledge is that Knowledge is Power. Today, when the international community talks of ‘empowerment’, it underlines the importance of literacy and education in the first instance.

Today we talk of knowledge society. The Government of India has, in recognition of this fact, set up a Knowledge Commission. ‘Because knowledge—including art, science, moral values, information (and misinformation)—now provides the key raw material for wealth creation, today’s power struggles reach deep into our minds, psyches, and personal lives.’

A reader may consider these criticisms of the present. But a discerning reader may applaud the profundity of these predictions made nearly 20 years ago. Toffler’s futuristic exercises can be treated as forewarnings of the impending future.

Daniel Bell on Post-Industrial Society

In 1973, Daniel Bell published The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting. That book was not exactly a criticism of industrial society, but a forecasting in the linear narrative about the shape of things to come. Bell argued that post-industrialism would be information-led and service-oriented. He listed the following three components of such a society:

- a shift from manufacturing to services

- the centrality of the new science-based industries

- the rise of new technical elites and the advent of a new principle of stratification.

Bell differentiated between three aspects of post-industrial society:

- data, or information describing the empirical world;

- information, or the organization of that data into meaningful systems and patterns such as statistical analysis; and

- knowledge, understood as the use of information to make judgements.5

The phrase post-industrial society was also understood by some scholars as an invitation to think of the ‘extra-industrial’ path of development. It was cogently argued by many scholars from the Third World that the present woes of the industrially developed world—environmental pollution, energy crisis, and fast depletion of non-renewable natural resources—can be avoided only when developing societies, with their own problem of high population growth rates, opt for a route that would modernize them without having to damage the environment any further. Maintaining bio-diversity and using renewable resources of energy such as the wind and sun were highlighted in the World Congress on Environment held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in the 1990s. Such an approach was also regarded as post-modern or extra-industrial.

Definition and Characteristics of Futures Studies

There are several definitions of this new discipline. Daniel Bell, in his book, The Coming of Post Industrial Society (1973), identified three approaches to the future:

- By social extrapolations from the past and the present into the future.

- By studying historical and fundamental elements of social change, which implies a careful historical analysis, in order to identify the dominant trends.

- By choices, as parts of specific frames of reference, from which trends are projected into the future.

Masini talks about the specific characteristics of futures studies. She mentions transdisciplinarity, complexity, globality, normativity, scientificity, dynamicity, and participation as the key distinguishing features of such studies. We shall briefly explain them.

- Transdisciplinarity: This is a subject that goes beyond the boundaries of a single discipline. But it differs from interdisciplinarity in the sense that the subject is not approached from the perspectives of different disciplines, but holistically in a paradigm that has judiciously integrated elements from various disciplines to become a new discipline by itself.

- Complexity. This characteristic refers to the complexity of the content and uncertainty of future occurrences.

- Globality. This is understood as related to the entire planet earth. The problems are global though their manifestation, and their gravity, may differ from society to society. All societies are concerned with the future, but all are going to have culture and region-specific futures; however, all are aware of the global ramifications of the local occurrence. An earthquake or a tsunami in one part of the world variously affects all other parts of the globe.

- Normativity. ‘In futures studies, normativity indicates the relations of these studies with specific values, desires, wishes or needs of the future.’ Defined this way, futures studies are much more than mere extrapolative studies.

- Scientificity. Generally, it is believed that ‘whatever is experimental, repeatable, and hence foreseeable is scientific. In referring to, or examining, the future, we are … examining something which has yet to occur and which, therefore, has been neither experimented, verified nor repeated.’ But Masini argues that it is not the subject matter that makes a discipline scientific—offering explanations and making predictions—it is the way we approach knowledge.

- Dynamicity. ‘No other discipline is required to change, in relation to changes in reality, as much as future studies …. The concept of living in uncertainty, of accepting error, of living in a complex situation, of needing to understand continuous change implies the need for futures studies to follow and understand such dynamic changes.’

- Participation. Futures studies insist on the participation of everyone who has to move into the future. The actors of the future—the young people especially— ‘must participate in the choice and the building of their own future’ (all quotes from Masini, 1993: 15–26).

Methodology for Futures Studies

Futures Studies are carried out both by subjective and systemic methods and objective methods. We shall briefly allude to them here.

Subjective or Intuitive Methods

When the studies rely on the knowledge, experience, talent and intuitions of the experts, the studies are said to be based on subjective or intuitive methods. Masini lists four such methods (1993: 78–79):

- ‘Panels of experts present their experiences face to face, in an open and unstructured manner’;

- ‘Brainstorming among experts, developed in a series of meetings based on simple rules and geared mainly to stimulating an open discussion. It is a process that tends to explain but not to solve’;

- ‘The Delphi method’; and

- ‘The cross-impact matrix’—a more complex form of the Delphi method. In this method, the experts remain anonymous and never actually meet, so as to avoid problems of leadership …. They are contacted by telephone or mail or by whatever other technique. The reliability of the consensus will be related to the possibility and feasibility of the event’ (Masini, 1993: 79). The cross-impact matrix, was ‘thought of in recognition of the fact that forecasts of future events, when made in isolation from one another, fail to take their mutual effects into systematic consideration and thus lack a degree of refinement whose addition … might well increase their reliability’ (Helmer, 1983: 159).

Objective Methods

The basic method of objective forecasting is called extrapolation. This method is used to indicate the exponential growth of linear forecasting in time, rapid logistic growth at the start, and cyclical growth. Population growth, as we indicated earlier, is projected in terms of exponential growth. Making various assumptions about the growth rate—based on the trends of fertility, mortality, and migration—the population of the coming decades is projected by the demographers. For example, the doubling time of population is calculated by dividing 70 years by the rate of growth. If the growth rate is 2 per cent, then the population will double in 35 years (70/2 = 35).

Trend extrapolations are done in several ways. For example:

- Morphological Analysis. This method is used to examine all possible variables and analyse them in their possible combinations.

- Historical Analogies. In this case the unit of analysis is the phenomenon, and the extrapolation is made on the basis of the characteristics of the phenomenon.

- Scenario Building. This ‘is a method that can be extrapolative or normative …. According to some futurists, scenarios are systematic methods since they are based on interrelated variables’ (p. 77). The difficulty in having sufficient reliable data hampers building dependable scenarios. But their flexibility allows the scenario builder to make mid-course changes. Scenarios, however, should be distinguished from imaginary alternative descriptions because they lack logic and are built on the basis of values, which may even be idiosyncratic.

A landmark study in the area of futures is The Global 2000, submitted in 1981 as a Report to the President of the United States, which analysed worldwide data on demographic growth, natural resources, and the environment. That study prompted many countries of the world to attempt similar exercises relative to their respective societies. In fact, this book laid down the foundations for futuristic studies. This was the study that alerted people worldwide to the problems of deforestation, increasing shortages of water resources, depletion of mineral wealth, general climate change, and the destruction of biological diversity. These are the themes that became the key subject matter for research and reflection in all sciences—including the social sciences—and provided key slogans for action to the international community under the aegis of the United Nations.

Vision for India 2020: Summary of a Massive Exercise

In 1998, a book titled India 2000: A Vision for the New Millennium, authored by A. P. J. Abdul Kalam6 in collaboration with Y. S. Rajan, was published. Prior to this, there were several exercises to anticipate the India of the year 2000. One such exercise was attempted by Iqbal Narain and Surendra K. Gupta (1989). It will serve no purpose now to examine the extrapolations made then, as we have already crossed the year 2000 and have completed the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Kalam acknowledges that India had made simultaneous progress in many fields since her independence. But

‘many of our vital socio-economy and other sectors began to have a greater dependence on foreign sources for innovation or technology …. Space research and a few other areas developed more as islands of confidence rather than as movements for developing core industrial and technological competencies’ (1998: 47).

Kalam argued that there is an immediate need for developing a technology vision that is based on the premise that we have to promote the growth of indigenous technology and develop self-reliance.

The authors recognized that India was encountering two problems originating from the external milieu:

- Large-scale strengthening of our neighbours through supply of arms and clandestine support to their nuclear and missile programmes.

- All efforts to weaken our indigenous technology growth through control regimes and dumping of low-tech systems, accompanied with high commercial pitch in critical areas (p. 20).

These problems are related to changes in the nature of warfare and its effects on human welfare. Up to the 1990s, warfare was weapon-driven; this led to the proliferation of conventional, nuclear, and biological weapons. They perceived that the next phase would lead to economic warfare, in which market forces would be controlled through high technology.

In developing the Vision for the India of the year 2020, Kalam underlined the point that India is not expansionist, because Indians possess greater tolerance, have less discipline and lack the sense of retaliation, demonstrate flexibility in accepting outsiders, show adherence to hierarchy, and lay greater emphasis on personal safety over adventure. But the authors declare that they ‘… are not advocating xenophobia nor isolation. But all of us have to be clear that nobody is going to hold our hands to lead us into the “developed country club”’ (Kalam, 1998: 24).

To develop the vision based on these premises, Kalam took the initiative, as the chief of Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO), to establish Technology Information Forecasting and Assessment Council, TIFAC in short. TIFAC involved various stake holders—the government, the industries, users, scientific and technological institutions, financial institutions, and intellectuals. A total of 500 experts were directly involved in this exercise; additionally, inputs were also received from 5,000 people from different walks of life. The council was assigned the task of looking ahead at the technologies emerging worldwide and picking those technology trajectories which were relevant for India.

The Council focused on 16 crucial sectors, listed below:

- Agro-food industries

- Road transportation

- Civil aviation

- Waterways

- Electric power

- Telecommunications

- Advanced sensors

- Engineering industries

- Electronics and communications

- Materials and processing

- Chemical processing industries

- Food and agriculture

- Life sciences and bio-technology

- Healthcare

- Strategic industries

- Services

For each of these sectors, TIFAC set up the following objectives:

- Provide directions for national initiatives in science and technology to realize a Vision for India up to 2020;

- Provide a strong basis for policy framework and investment for R&D in the government and the private sector; and

- Contribute to the development of an integrated S&T policy, both at the state and national levels.

The task forces used various techniques of forecasting such as brainstorming sessions, preparation of perspectives and scenarios, delphi rounds, nominal group techniques and workshops. Each task force looked at the economic and social ends, gauged consumer trends and global technology trends, identified broad areas of advantage, compared world indices (of yields and productivity). It also investigated the key driving forces and major impediments. Based on these exercises, the task forces prepared guidelines for the future. Vision reports prepared by each task force made wide-ranging suggestions for action: (i) simple modification of policies; (ii) improvement of administrative procedures; (iii) introduction of simple technology practices; and (iv) mastery of new and emerging complex technologies.

The book selected five sectors for building the vision for India. They are:

- Food, Agriculture, and Processing;

- Materials;

- Chemical Industries;

- Manufacturing for the Future;

- Services as People’s Wealth;

- Strategic Industries; and

- Healthcare for All.

Kalam believes that technology is the main driver of economic development. India has to answer the question: How do we handle the tactics of economic and military dominance in this new form? They firmly assert that ‘Nations are built by imagination and untiring enthusiastic efforts of generations.’ Furthermore, ‘Any organization, society, or even a nation without a VISION is like a ship cruising on the high seas without any aim or direction’ (Kalam, 1998: 21).

Kalam gives credit to Mahatma Gandhi for his vision of a free India. That was the first vision. The second vision is offered in this book: ‘Let us, collectively, set the second national vision of developed India.’ This Vision, the authors assert, ‘is possible and can materialize in 15–20 years’.

Kalam envisions India of the year 2020 as a country of developed status. The following are the characteristics of the developed status:

- major transformation of our national economy to make it one of the largest economies in the world;

- countrymen live well above the poverty line, have a high standard of health and education;

- national security reasonably assured; and

- core competence in certain major areas gets enhanced significantly to produce quality goods (both for internal consumption and for exports).7

It is argued that all these features will bring about the overall prosperity of the country. The key to reach the developed status lies in our technological strength. The prerequisite for this is building and strengthening our national infrastructure. We have to build around our existing strengths. We have a vast pool of talented scientists and technologies and we have abundant natural resources. To begin with, we will have to concentrate on the development of key areas, namely, agricultural production, food processing, materials, computer software and biotechnologies. The common link to bring about this transformation is the human resource. Authors recommend the development of various endogenous technological strengths. According to them, ‘Technologies are primarily manifestations of human experience and knowledge and thus are capable of further creative development, under enabling environments’ (Kalam, 1998: 123).

Kalam lists the following indicators of well-being of the people:

- Overall nutritional status;

- Availability of good nutrition during various phases of their growth and lives;

- Average life expectancy;

- Reduction in infant mortality rate;

- Availability of sanitation;

- Availability of drinking water and its quality;

- Quantum of living space—broad categories of human habitat;

- Incidence of various diseases, dysfunctions, disorders, and disabilities;

- Access to medical facilities;

- Literacy;

- Availability of schools and educational facilities;

- Various levels of skills to cope with fast-changing economic and social demands.

In identifying these indicators of developed status, the authors opine that while aggregated indicators are important, it does not make sense to achieve a developed status without a major and continuing upliftment of all Indians who exist today and of the many more millions who would be added in the years to come’ (p. 3). People should all have a secure and enjoyable ‘present’ and also be in a position to look forward to a better ‘future’.

In order to reach the developed status, Kalam has listed the major tasks to be done:

- To remove India’s poverty.

- To provide health for All.

- To provide good education and skills for All.

- To provide employment opportunities for All.

- To be a net exporter.

- To be self-reliant in national security and improve on all these in the future.

In achieving this, Kalam pointed out the following core competencies that India has in abundance (Kalam, 1998: 50–51):

- India’s human resource base is one of the greatest core competencies.

- The Natural Resource base.

- Excellent base for living resources: very rich bio-diversity, abundant sunshine, varied agro-climatic conditions—from arctic cold to tropical green to bare deserts, and plenty of rainfall.8

Without going into more technical details of each individual sector, we summarize the Vision Statement (ibid.: 269–71):

- India should become a developed nation by the year 2020.

- Developed India means that it will be one of the five biggest economic powers, with self-reliance in national security.

- Several steps in the field of agriculture will have to be taken in this regard. Particularly

- Capitalize on the agricultural core strengths and establish a major value-adding agro-food industry for export as well. This would need the absorption of surplus labour for an efficient agricultural production and distribution system.

- Around the agro-food sector should be grown engineering industries and services and businesses.

- Capitalize on the vast mineral wealth—steel, aluminium, titanium, and rare earths.

- The chemical industry should be transformed into a global technological innovator in clean processes and specialty chemicals.

- We should use marine resources and take advantage of bio-diversity.

- There has to be a resurgence of the engineering industry—machine tools, textiles, foundry, electrical machinery, transport equipment so that by the year 2010, India becomes a net exporter of technology and a world leader in embodied software for manufacturing and design.

- India should emerge as a global leader in the services sector.

- Attention should also be paid to the strategic sectors. The confluence of civilian and defence technologies should yield a good peace dividend.

- Attention to the health of the people is vital.

- There is a need for speedier growth of the infrastructure: energy in terms of supply of quality electric power, improvement and extension of roads, waterways, airways, ports, telecommunications, and enhanced rural connectivity.

- Role of the panchayats in this regard has not only to be acknowledged, but must be devised to make their participation in fulfilling this vision more meaningful and effective.

Kalam is of the view that this strategy is workable. His hope is based on the following enabling factors:

- A large part of our population is young and wants a change.

- Those earlier blocking change are now in favour of it.

- Licence-quota Raj is substantially dismantled, resulting in the unleashing of a large amount of entrepreneurial talent and adventurous spirit.

- The young are looking for jobs outside of the government.

- Explosive growth of television has given worldwide exposure to the common man.

- There is a growth in criticism of the pervasive corruption, mindless bureaucracy and greedy politicians.

- Hopes are raised by the post-liberalization of the economy.

- Many have tasted the benefits of economic growth and the resultant difference, and this has triggered their imagination.

- There has been substantial devolution of power to the states and to the Panchayats.

Kalam sounds confident that the India of the year 2020 would be sufficiently different from the India of the 1990s, and would be moving in the direction that he has recommended through this book, which is based on a cool analysis of the trends and of the potential of India, both in terms of human resources and the natural capital.

Final Comment

Investigating the future is like entering the arena of the unknown. Those who distinguished between science and philosophy suggested that the latter is a scheme of knowing the unknown and speculating about the not-knowable. Science focussed on the known and the empirical and researched its structure and functioning. Its predictions related to the behaviour of these known agents of nature through repeated experimentation and identification of the uniformity of responses. Those that remain beyond the reach of science are explained by extensions of logic or wild imagination (call them un-testable hypotheses), or acts of God (non-rational beliefs) that are beyond questioning by the believer.

It is essential that we develop our powers of prediction of at least those features that will arrive almost inevitably. Moreover, we can even establish our own blueprints of the future society, and take steps to realize that architecture. In the light of such inevitabilities, and the realizable prophesies—and not the unattainable utopias—we have to reorder our priorities and plan our efforts. It is for the thinking people to speculate about which prophecies would be fulfilled and which cancelled. One must, however, admit the enormous possibilities of unintended consequences, which could be functional, dysfunctional, or simply non-functional for the society.

Despite differences in approach, there is an emerging consensus that there is no going back to our cultural shells by isolating and insulating cultures from each other. Cultural oysters are no longer possible. The opening out, intercultural dialogue, and cross-cultural fertilization have brought into play two seemingly contradictory processes of (i) globalization and (ii) localization or indigenization. The coexistence of these processes is, in fact, indicative of the resilience of cultures. There is a need to know how these twin processes relate and operate in different cultural settings and how new equations are worked out. The fact remains that while cultures are no longer completely insulated, the opening up of apertures9 has not uprooted them. They are able to maintain their core and retain their identity.

There is a need to establish a relationship between the concepts of ‘Change’ and ‘Future’. Both concepts are diachronic. In earlier writings, change was seen as pastoriented, whereas future was considered forward-looking. In such a distinction, change was regarded as rooted in history, and the future was dependent upon our powers of prediction. Analysts of change often indulged in the glorification of the past; prognosticians of the future tended to exaggerate the glory of their vision of the future or decry the prospects of an unwanted future. Those concerned with the future either talk of appropriating the PAST, or of displacing the PRESENT, or of colonizing the FUTURE. In a broader sense, the concept of change covers past, present, and the future; the methodology of investigation, however, differs from one orientation to another.

Are our visions of the future and their propagation attempts towards the colonization of the future? And can we really colonize it, given the existence of several variables that tend to influence any cultural change? Who determines what is good or bad for a given society? The conspiracy allegation implicit in our critiques of the past and the present is based on our wisdom of hindsight. Any vision of the future prepared by any group can be seen as an imposition, yet another instance of conspiracy—of the group or the country or the ideological outfit.

There has been ample criticism of the West as a colonizer responsible for destroying Asian cultures; but the fact is that the West itself is disintegrating in some respects and that despite a spate of changes in Asian cultures, their cores are still intact.

Asia is home to major civilizations and religions; it is indeed a cultural mosaic. All Asian societies and cultures are simultaneously experiencing the twin processes of globalization and indigenization. The universal desire for change notwithstanding, societies are making an equally emphatic assertion of their respective cultural identities. The forces of change have not transformed cultures even into look-alike societies. Industrializing Thailand cannot be mistaken for Taiwan, or the roaring tiger of South Korea for Japan. What one witnesses in Asian cultures is a growing heterogeneity—a queer mixture of tradition and modernity: jumbo jets and bullock carts; mosques and science labs; traditional attire and western paraphernalia. Through the exposure to the wider world, each culture has certain elements of a global culture which itself is now greatly differentiated rather than being merely ‘western’. The migration of people and their settlement in other cultures has given rise to what I have called, Sandwich Cultures—sandwiched between the forces of the parent culture and the host culture. It is not only Japan or China that has come to, for example, Bangladesh or India, but Bangladesh and India have also reached these destinations. Chinese restaurants in different lands, to take another example, have popularized Chinese food, but in each country Chinese food tastes different because of its adaptation to the local taste. The way English is spoken by the people of different countries demonstrates cultural ingenuity to adapt outside elements. Cultures have shown remarkable degrees of resilience to withstand the onslaught of outside forces like bamboos, they have bent in the face of storms but have not broken.

Fears do exist in terms of the possibilities that open out with each technological advancement. Some people argue that the growth of science heralded the end of Nature, that genetic engineering now heralds the end of Culture, and that robotics in the future will cause the end of Species. This is a horrible scenario for the future, which no one will like to enter. However, it must be stressed that whatever is technologically feasible is not always socially desirable and culturally acceptable. To the same innovation, different cultures respond differently. While it is true that technology has helped in widening the cognitive horizons and enlarging the range of choices, its global hegemonic blanket is incapable of shrouding all cultural specificities. What uses a given technology is put to is still very much dependent on the people. The resurgence and revival of tradition alongside of development places question marks on the conspiracy theory that blames the North for all the ills of development.

There are several unintended consequences of the development process. The reinforcement of the cultural identity is one of them. Modern media have done a great deal to revive and diffuse tradition. People have become mobile—both physically and psychologically. Not only do they cross cultural boundaries, they are also enabled to travel into the corridors of their cultural past.

Change has now become a key concept and its inevitability is recognized. It is acknowledged that the desire for change is universal; all societies—big or small, modern or primitive, western or non-western—share this desire. At the same time, one also notices a new-found attachment to one’s own culture; there is in evidence an effective assertion of cultural identity. No society would wish to lose its cultural roots. No culture would allow itself to be engulfed by another dominant culture. These two tendencies—desire for change and keenness to maintain identity—have resulted in the increasing modernization of societies on the one hand, and the revival and resurgence of tradition on the other. Forces of change have not homogenized the globe into a common culture. Individual cultures have certainly changed and expanded, both in material and non-material terms, but they have not lost their identities. Religion and tradition have constantly tried to establish new equations with external forces of change. There is an accretion of new cultural elements—either invented within or innovated from the outside; simultaneously, there is also an attrition of some old cultural traits—deliberately or otherwise.

One may ask: Does the disappearance of certain cultural traits amount to the destruction of a culture? If the answer is in the affirmative, we may pose the question: How does the culture grow? Or, is culture just another name for the deadwood? Changes occurring in the ambit of culture do not always erase its identity; they may, however, confuse its identification. Accretion and attrition are the processes that operate in all living cultures; that is how they grow and express their vitality.

The phenomenon of cultural continuity has challenged the homogenization hypothesis. While individual cultures are experiencing vast changes, they are not becoming similar, not even look-alike. Even their own homogeneity has suffered; they are becoming heterogeneous both in terms of their demographic composition, and cultural constitution. The so-called World Culture’s monocultural stance is no longer tenable. The plausible perspective is to view both culture and future in their plurality. No single future can be imposed on all cultures. Cultures have the ingenuity to respond to changes and bring about new equations between the old and the new.

In this sense, we cannot talk of the future (in singular) of cultures (in plural). Of course, there will be a single, empirical future of a given culture, but scholars may present alternative scenarios—these would be in the nature of prescriptions and not predictions. Similarly, predictive futurists may sound optimistic or pessimistic depending upon the premises of their prediction. That is why we use both culture and future as plurals in this discourse. Plurality goes even further: most nation-societies are plural, both in terms of ethnic composition and cultural constitution, thanks to decades of culture contact which is now greatly accelerated by the modern means of rapid transportation and communication. Each society consists of multiple layers of culture. At least three strata can be easily identified:

- Universal, international (global) culture of science and technology, modern industry, bureaucracy, transport and communication, the emerging Infosphere;

- Emergent national culture, deriving civilizational base and giving the country its cultural identity; and

- Regional and local, parochial cultures; sandwich cultures—cultures of migrant groups, which emerge as a result of sandwiching between the forces of the parent culture and the host country culture.

Asia has proved the falsity of the dichotomy between tradition and modernity. They are not polar opposites. There are elements of modernity in tradition, and modernization has helped in the propagation of tradition. The rise of ethnic restaurants, the modernization of the architecture of mosques and temples, the popularization of mythical epics through their televization are cases in point. Jumbo jets have not replaced the bullock cart as a mode of transport; allopathy has not made Indian Ayurved or the Chinese acupuncture redundant; while forks and knives are used by the non-Chinese to eat Chinese food, chopsticks are likewise employed by the Chinese and the Japanese while eating western cuisine. It seems that the coexistence principle has overshadowed the replacement and transplantation paradigm of western development. There is a symbiosis of the elements of tradition and modernity, and since traditions represent a given culture’s uniqueness, the symbiosis has resulted in different profiles of emergent cultures in different societies. Cultures will not be dead, they will be different both from their past, and from other cultures. What is difficult to foretell is the exact chemistry of this difference. What can be predicted, however, is the outcome of irreversible trends—trends that cannot be halted, and are therefore inevitable. For example, in the case of Asia it can be said that it is inevitable that literacy levels will rise in the near future; that urbanization and industrialization will further accelerate; that the information revolution will transform the styles of management—both of governments and private business; that environmental pollution and depletion of natural resources will increasingly become difficult to stem; that there will be more people inhabiting the region; and that there will be more scientism in our mode of thinking.

What appears possible are the following: stabilization of population growth around a 1 per cent level; near total literacy by the year 2010; rise of mixed economies and the virtual collapse of communism; greater democratization of political regimes; continuation of poverty and widening disparities; continued global and regional conflicts; rise of religious fundamentalism and parochial loyalties; emergence of stronger supra-national forms of co-operation (process of epigenesis). As to what is desirable, there cannot be a consensus. This will remain only an intellectual pastime of the pundits of the future. Real societies do not blindly accept prescriptions.

There is nothing strange in culture change. What a culture retains and what it gives up, or what it receives from the outside after a thorough cultural screening and redefinition, is a complicated process. Living cultures do not oblige spectators who would like to put the culture on stage, or make it a showpiece, an anthropological zoo. It is common knowledge that tourists arriving in traditional societies to observe exotic cultures have been primarily responsible for disturbing their status quo. But such disturbance may not be regarded as dysfunctional by those who live that culture. Surely, their culture will not remain the same, but changes in it need not be symptomatic of an impending demise. And views may differ on what is good or bad; what the outsiders may like to retain may be the one that the insiders would like to discard, and vice versa.

It can be said that all cultures in the future will look different from what they are today with changes in the profiles of their demography and literacy, and with the continuing onslaught of technology and its attendant ramifications. But they will remain, and remain different with their own identities. Similarities in material culture—the externalia—will not obliterate differences in values and ways of life. There will not be a single future for the globe, nor will there be a single global culture.

Multiple cultures will have multiple futures.

Heterogeneity will prevail.