2

Risk Assessment

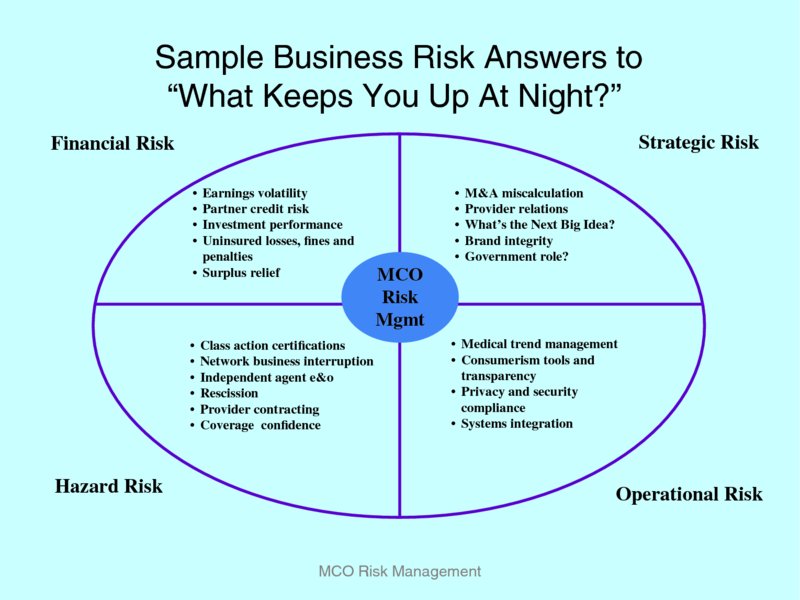

In the risk assessment step the enterprise identifies the critical risks to strategy, it analyses and evaluates these critical risks and it prioritizes the critical risks. Risk assessment has been the traditional focus of many risk managers for decades. However, in ERM critical risks include all risks whether operational, competitive, financial, regulatory or from other sources. Finally both positive and negative risks are considered in the context of their criticality as it could affect the strategy.

2.1 RISK QUANTIFICATION: CORNERSTONE FOR RATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT

Jean-Paul Louisot

Formerly Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Directeur pédagogique du CARM Institute, Paris, France

Laurent Condamin, Ph.D

Consultant and CEO ELSEWARE1

Patrick Naim

Consultant and Partner ELSEWARE

Enterprise-wide risk management (ERM) is a key issue for boards of directors worldwide. Its proper implementation ensures transparent governance with all stakeholders' interests integrated into the strategic equation. Furthermore, risk quantification is the cornerstone of effective risk management, at the strategic, tactical, and operational level, covering finance as well as ethics considerations. Both downside and upside risks (threats and opportunities) must be assessed to select the most efficient risk control measures and to set up efficient risk financing mechanisms. Only thus will an optimum return on capital and a reliable protection against bankruptcy be ensured, i.e. long-term sustainable development.

Within the ERM framework, each individual operational entity is called upon to control its own risks, within the guidelines set up by the board of directors, whereas the risk financing strategy is developed and implemented at the corporate level to optimize the balance between threats and opportunities, systematic and non-systematic risks, pre- and post-loss financing and finally retention and transfer.

However, those risk reduction measures, including risk avoidance, that entail substantial investments and financial impacts may have to be decided at the top management level for approval within the global financial strategy.

However daunting the task, each board member, each executive and each field manager must be equipped with the toolbox enabling them to quantify the risks within his/her jurisdiction to the fullest possible extent and thus make sound, rational and justifiable decisions, while recognizing the limits of the exercise. Beyond traditional probability analysis, used by the insurance community since the 18th century, the toolbox offers insight into new developments like Bayesian expert networks, Monte Carlo simulation, etc., with practical illustrations on how to implement them within the three steps of risk management: diagnostic, treatment and audit.

Recent progress in risk management shows that the risk-management process needs to be implemented in a strategic, enterprise-wide manner, and therefore, account for conflicting objectives and trade-offs. This means that risk can no longer be limited to the downside effect; the upside effect must also be taken into account. The central objective of global risk management is to enhance opportunities while curbing threats, i.e. driving up stockholders' value, while upholding other stakeholders' expectations. Therefore, risk quantification has become the cornerstone of effective strategic and enterprise-wide risk management.

2.1.1 Why Is Risk Quantification Needed?

The volatile context within which organizations must operate today calls for a dynamic and proactive vision aimed at achieving the organization's mission, goals and objectives under any stress or surprise. It requires a new expanded definition of “risks”. The “new” risk manager must think and look beyond the organization's frontiers, more specifically to include all the economic partners and indeed all the stakeholders of the organization. Special attention must be devoted to the supply chain, or procurement cloud, and the interdependences of all parties.

The ISO 31000:2009 standard provides a very broad definition of risk as the impact of uncertainties on the organization's objectives. It provides a road map to effective ERM (enterprise-wide risk management) rather than a compliance reference; this is why the principles and framework provide a track to explore.

But whatever the preferred itinerary, all managers will need to develop a risk register and quantify the possible or probable consequences of risks to make rational decisions that can be disclosed to the authorities and the public. In many circumstances the data available are not reliable and complete enough to open the gates for traditional probability and trend analysis, other toolboxes may be required to develop satisfactory quantification models to help decision makers include a proper evaluation of uncertainty in any strategic or operational decision.

As a reminder, we believe that the cornerstone of risk management is the risk management process completed by a clear definition of what is a risk or exposure:

- The definition of an exposure: resource at risk, peril, and consequences.

- The 3-step risk management process: diagnostic of exposures (risk assessment), risk treatment, and audit (monitor and review), the risk treatment step being further broken down into design, development, and implementation phases of the risk management program.

Therefore, quantification is the key element for strategic – or holistic – risk management, as only a proper evaluation of uncertainties allows for rational decision-making. Only a robust perspective on risk could support the design of a risk management program, both at tactical and strategic levels, for implementation at the operational level. One of the key tasks of the risk manager is to design a risk management program and have it approved.

2.1.2 Causal Structure of Risk

Risks are situations where damaging events may occur but are not fully predictable. Recognizing some degree of unpredictability in these situations means that events must be considered as random. But randomness does not mean that these events can't be analyzed and quantified!

Most of the risks that will be considered throughout this book are partially driven by a series of factors, or drivers. These drivers are conditions or causes that would make the occurrence of the risk more probable, or more severe.

From a scientific viewpoint, causation is the foundation of determinism: identifying all the causes of a given phenomenon would allow prediction of the occurrence and unfolding of this event. Similarly, the probability theory is the mathematical perspective on uncertainty. Even in situations where an event is totally unpredictable, the laws of probability can help to envision and quantify the possible futures. Knowledge is the reduction of uncertainty – when we gain a better and better understanding of a phenomenon, the random part of the outcome decreases compared to the deterministic part.

Some authors introduce a subtle distinction between uncertainty and volatility, the latter being an intrinsic randomness of a phenomenon that cannot be reduced. In the framework of deterministic physics, there is no such thing as variability, and apparent randomness is only the result of incomplete knowledge. Invoking Heisenberg's “uncertainty principle” in a discussion on risk quantification seems disproportionate. But should we do it, we understand the principle as stating that the ultimate knowledge is not reachable, rather than that events are random by nature:

“In the sharp formulation of the law of causality (if we know the present exactly, we can calculate the future) it is not the conclusion that is wrong but the premise.” (W. Heisenberg, 1969)

Risk management is maturing into a fully-fledged branch of managerial sciences dealing with the handling of uncertainty with which any organization is confronted, due to more or less predictable changes in the internal and external context in which they operate, as well as evolutions in their ownership and stakeholders that may modify their objectives.

Judgment can be applied to decision making in risk-related issues, but rational and transparent processes called for by good governance practices require that risks be quantified to the fullest extent possible. When data are insufficient, unavailable or irrelevant, expertise must be called upon to quantify impacts as well as likelihoods. This is precisely what this chapter is about. It will guide the reader through the quantification tools appropriate at all three steps of the risk management process: diagnostic to set priority; loss control and loss financing to select the most efficient methods with one major goal – long-term value to stakeholders – in mind; and audit to validate the results and improve the future.

2.1.3 Increasing Awareness of Exposures and Stakes

The analysis of recent major catastrophes outlines three important features of risk assessment. First, major catastrophes always hit where and when no one expects them. Second, it is often inaccurate to consider they were fully unexpected, but rather that they were consciously not considered. Third, the general tendency to fight against risks that have already materialized leaves us unprepared for major catastrophes.

A sound risk assessment process should not neglect any of these points. What has already happened could strike again; and it is essential to remain vigilant. What has never happened may happen in the future, and therefore we must analyze potential scenarios with all available knowledge.

The Bayesian approach to probabilities can bring an interesting contribution to this problem. The major contribution of Thomas Bayes to scientific rationality was to clearly express that uncertainty is conditioned to available information. In other words, risk perception is conditioned by someone's knowledge.

Using the Bayesian approach, a probability (i.e. a quantification of uncertainty) cannot be defined outside an information context. Roughly speaking, “what can happen” is meaningless. I can only assess what I believe is possible. And what I believe possible is conditioned by what I know. This view is perfectly in line with an open approach of risk management. The future is “what I believe is possible”. And “what I know” is not only what has already happened but also all available knowledge about organizations and their risk exposure. Risk management starts by knowledge management.

2.1.4 Risk Quantification for Risk Control

Reducing the risks is the ultimate objective of risk management, or should we say reducing some risks. Because risks cannot be totally suppressed – as a consequence of the intrinsic incompleteness of human knowledge – risk reduction is a trade-off.

Furthermore, even when knowledge is not the issue, it may not be “worth it” for an organization to attempt a loss reduction exercise, at least not beyond the point when the marginal costs and the marginal benefits are equal. Beyond that point it becomes uneconomical to invest in loss control. Then two questions will have to be addressed:

- At the microeconomic level: how to handle the residual risk, including the treatments through risk financing.

- At the macroeconomic level: or should we say at the societal level, in the situation left as is by the individual organization, are there any externalities, risks or cost to society not borne in the private transaction? In such a case the authorities may want to step in through legislation or regulation to “internalize” the costs so that the organization is forced to reconsider its initial position. A clear illustration is the environment issue: many governments and some international conventions have imposed drastic measures to clean the environment that have forced many private organizations to reconsider their pollution and waste risks.

Beyond the macro-micro distinction, there are individual variations on the perception of risk by each member of a given group; each group and the final decisions may rest heavily on the perception of risk by those in charge of the final arbitration. This should be kept in mind throughout the implementation of the risk management process. Why do people build in natural disaster prone areas without really taking all the loss reduction measures available, while at the same time failing to understand why the insurer will refuse to offer them the cover they want or at a premium they are willing to pay?

Every individual builds his own representation that dictates his perception of risks and the structural invariants in his memory help in understanding the decision he reached. His reasoning is based on prototypes or schemes that will influence the decision he reaches. In many instances, decisions are made on a thinking process based on analogies: they try to recall previous situations analogous to the one they are confronted with. Therefore, organizing systematic feedback at the unit level and conducting local debriefing should lead to a better grasp of the local risks and a treatment more closely adapted to the reality of the risks to which people are exposed.

This method should partially solve the paradox we have briefly described above, as the gradual construction of a reasonable perception of risk in all should lead to more rational decisions.4

There remains to take into account the pre-crisis situation when the deciders are under pressure and where the time element is a key to understanding sometimes disastrous decisions. Preparing everyone to operate under stress will therefore prove key to the resilience of any organization.

From a quantitative point of view, the implementation of any risk control measure will:

- Change the distribution of some risk driver, either at the exposure, occurrence, or impact level;

- Have a direct cost, related to the implementation itself; and

- Have an indirect or opportunity cost, related to the potential impact on the business.

Therefore, the cost of risks is the sum of three elements: accident losses, loss control cost, and opportunity cost.5 These elements are of course interrelated. Reaching the best configuration of acceptable risks is therefore an optimization problem, under budget and other constraints. From a mathematical point of view, this is a well-defined problem.

Of course, since loss reduction actions have an intrinsic cost, there is no way to reduce the cost of risks to zero. Sometimes, the loss control action is simply not worth implementing. The opportunity cost is also essential: ignoring this dimension of the loss control would often result in a very simple optimal solution – reducing the exposure to zero, or in other words, stopping the activity at risk! This loss control method is called avoidance, and will be discussed further.

As we will see, the quantitative approach to risks is a very helpful tool for selecting the appropriate loss control actions. But here we must be very careful as four categories of drivers can be identified:

- Controllable drivers can be influenced by a decision.

- Predictable drivers cannot really be influenced by a decision, but their evolution can be predicted to some extent.

- Observable drivers cannot be influenced, nor predicted. They can only be observed after the facts, a posteriori. Observable drivers should not normally be included in a causal risk model, since they cannot be used as levers to reduce impacts. On the other hand, they are helpful to gain a better understanding of risk and as some of these drivers are measurable they assist in piloting the risk.

- Hidden drivers cannot be measured directly, not even a posteriori, but may be controlled to some extent.

When a first set of risk models is created during the risk assessment phase, the use of observable and hidden drivers would generally be limited to the initial risk assessment, simply because they cannot assist in the evaluation of the impact of proposed loss reduction measures.

For instance, when dealing with terrorist risks, the hostility of potential terrorists cannot be measured. When dealing with operational risks, the training level and the workload of the employees certainly impact the probability of a mistake. However, this dependency is very difficult to assess. But should these drivers be ignored in risk reduction? Should a state ignore the potential impact of a sound diplomacy or communication to reduce terrorist exposure? Should a bank neglect to train its employees when striving to improve the quality of service and reduce the probability of errors?

Simply said, we must recognize that causal models of risks are partial. And, although using this type of models is a significant improvement when dealing with risk assessment, they should only be considered as a contribution when dealing with risk reduction.

2.1.5 Risk Quantification for Risk Financing

Risk financing is part of the overall medium- and long-term financing of any organization. Therefore, its main goal is derived from the goals of the finance department, i.e. maximizing return while avoiding bankruptcy, in terms of obtaining the maximum return on investments for the level of risk acceptable to the directors and stockholders. In economic terms, that means riding on the efficient frontier.

To reach this goal the organization can use a set of tools aimed at spreading through time and space the impact of the losses it may incur, and more generally taking care of the cash flows at risk. However, deciding whether it can retain or must transfer the financial impact of its risks cannot be based merely on a qualitative assessment of risks. A quantitative evaluation of risks is necessary to support the selection of the appropriate risk financing instruments, to negotiate a deal with an insurer or understand the cost of a complex financing process.

The question is to identify the benefits of building a model which quantifies the global cost of risks, thus providing the risk manager with a tool that allows him to test several financing scenarios: the benefits of quantification to enhance the process of selection of a risk financing solution. Financing is the third leg of risk management based on the initial diagnostic and after all reasonable efforts at reducing the risks have been selected. Risk financing, even more than risk diagnostic or reduction, requires an accurate knowledge of your risks. “How much will you transfer?” and “How much will you retain?” are questions about quantities, the answers to which obviously require fairly precise figures.

Insurance premiums are set on the basis of quantitative models developed by the actuaries of insurance and reinsurance companies. Thus, insurance companies presumably have an accurate evaluation of the cost of your (insurable) risks. The problem is to ensure a balanced approach at the negotiation table. It is not conceivable to have a strong position when negotiating your insurance premiums equipped with only a qualitative knowledge of your risks. You may try, but it will be difficult for you to convince an insurer.

A complex financing program is usually expensive to set up, and sometimes to maintain; therefore the organization must make sure that the risks to be transferred are worth the effort. As part of their governance duties, the board of directors will expect from the finance director a convincing justification of the proposed program both in terms of results and efforts.

Any decision concerning the evaluation or the selection of a financing tool must be based on a quantified knowledge of your risks. Defining the appropriate layers of risk to be retained, transferred, or shared involves a clear understanding of the distribution of potential losses. Deciding whether you are able to retain a €10 million loss requires that you at least know the probability of occurrence of such a loss.

Before developing any risk financing programs, the first decision concerns what risks must be financed. This issue should be addressed during the diagnostic step. Diagnostic has been extensively developed in a previous article. This step provides a model for each loss exposure and sometimes a global risk model. This model quantifies:

- The probability of occurrence of a given peril;

- The distribution of losses should the peril occur; and

- The distribution of the cumulated losses over a given period.

Developing and implementing a risk financing solution involves being able, at least, to measure beforehand the cost of retention and the cost of transfer and this is possible only by combining the risk model and a mathematical formalization of the financing tool cost.

2.1.6 Conclusion

Risk quantification is essential for risk diagnostic, risk control and risk financing. All steps of the risk management process involve indeed an accurate knowledge of the risks an organization has to face and of the levers it could use to control risks, and finally what remains to be financed.

However, under certain circumstances, an organization could still rely on qualitative assessment to identify and control its risks. For risk financing, qualitative assessment is definitely not adequate to deal with evaluating premiums, losses volatility, etc. An accurate quantification of risks is necessary for a rational risk financing.

Several motivations lead the risk manager to address the quantification of risks:

- Financial strategy: Any organization should know if its financing program is well suited for the threats it has to face, and the opportunities it may want to seize. Financing program features must be linked to the distribution of potential losses that have to be covered, and of the potential needs to finance new unexpected projects. Answers to these two questions cannot be based on qualitative assessment of risks. Quantitative risk models are the basic tools to run an efficient analysis of this issue.

- Insurance purchasing: When an organization has to negotiate with insurers or insurance brokers, it has to be aware of the risks it wants to transfer and more precisely of the distribution of the potential losses that could be transferred. If the insurers rely on internal quantitative models generally based on actuarial studies or on expert knowledge (especially for disaster scenarios), the organization should have a more accurate knowledge of its own risks, at least for exceptional events which would not be represented in insurance companies' databases. Therefore both insurers and organizations must share their knowledge to build an accurate model of risks.

- Program optimization: The optimization of an existing financing program or the design and selection of a new one require building quantitative models. In the first case, the quantitative model will help to identify the key financing features required to improve the organization coverage. In the second case, plugging the different financing alternatives with the risk model will give the organization a clear view of the risks it would have to retain and transfer.

However, modeling the risks may prove insufficient if we want to address the three challenges listed above. We also have to model the financing program. A general framework can be developed where any financing program can be considered as a set of elementary financing blocks and then used as a base model for the present financing program. This model should suffice for many of the classical financing tools – self-insurance and informal retention, first line insurance, excess insurance, retro-tariff insurance, captive insurer, cat bonds – but it should be adapted to take into account a complex financing set up.

But even if an organization did its best and built an accurate model of risks and financing tools and even if it is able to evaluate the theoretical premium it should pay, the market will decide the actual price the organization should pay to transfer its risks. This market may be unbalanced for some special risks. When the insurance offer is tight, actual premiums could differ from theoretical primes calculated by models. This does not invalidate the need for accurate quantification as, even if the final cost of transfer depends on the insurance market, the organization should be aware of that fact and assess the difference. Also, the liquidity of the insurance markets is likely to increase as they become connected with the capital markets. The efficiency of these markets leads us to expect that the price to be paid for risk transfer will tend to be the “right” one.

Reference

W. Heisenberg (1969), Der Teil und das Ganze. Munich: Piper. English: Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversations. A.J. Pomerans, trans. (New York: Harper & Row).

2.2 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CINDYNICS

Georges-Yves Kervern

Formerly Ancien Élève de l'Ecole Polytechnique, and founder of Cindynics

Jean-Paul Louisot

Formerly Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Directeur pédagogique du CARM Institute, Paris, France

One of the major difficulties for a risk manager is not only to identify and quantify the emerging risks, the known-unknowns, but also to imagine those that are not yet emerging, the unknown-unknowns. For that brainstorming exercise there is no relying on past events, on data bank and mathematical models that have no basis to be developed. Even systems safety approaches fall short of a total vision as they incorporate human elements as components of the system with their own rate of failure, but fail to really take account of what is now known as the “human factor”. The human element is part of the system, but he acts also to modify it for his benefit. Understanding everyone's motivation and point of view is essential to foresee what may contribute to future risks, opportunities and threats.

It is with this objective in view that some French scientists and executives, led by Georges-Yves Kervern, developed a new approach to foreseeing, rather than forecasting, future developments when they imagined the “hyperspace of danger” and founded what they called Cindynics.

Since the early 1990s, a group of practitioners gathered around Jean-Luc Wybo, a professor at the École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris, to develop practical examples of using Cindynics to understand past complex events and project their findings for future action and decision making. Their application included “Explosion”, for example, the explosion at the AZF factory on September 22, 2001 in France; “Pollution”, like that on the beaches of Brittany, “Social Unrest” events, as occurred in the suburbs in France, to name but a few.

Some trace the first step in Cindynics6 to the earthquake in Lisbon. Science starts where beliefs fade. The earthquake in Lisbon in 1755 was the source of one of the most famous polemic battles between Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The main result was the affirmation that mankind was to refuse fate. This is reflected in Bernstein's7 comment “Risk is not a fate but a choice.”

In a way, the Lisbon episode may well be the first public manifestation of what is essential in managing risks: a clear refusal of passively accepting “fate”, a definite will to actively forge the future through domesticating probabilities, thus reducing the field of uncertainty.

However, since the financial crisis of 2008, black swans or fat tails represent a major challenge to all professionals in charge of the management of organization. Clearly, the traditional approaches to identifying and quantifying uncertainties based on probability or trend analysis are at a loss in a world that changes fast and may be subject to unexpected, and sometimes unsuspected ruptures.

As a matter of fact, these “dangerous or hazardous” situations can develop into opportunities or threats depending on how the leadership can anticipate them and exploit them for the benefit of their organization, and its growth in a resilient society.

Human factors are a key factor in the anticipation and development of such situations. Although it is essential that decision-makers learn to make decisions under uncertainty, it is far from sufficient to prepare for the black swans. Furthermore, system safety approaches that consider the human component as a physical element fall short of taking into account the fact that humans are part of a complex system that they influence and try to change to their benefit; and the system can be affected and modified even through a simple act of observation.

In such a volatile situation, the concepts developed as early as the late 1980s could prove very valuable if properly used and translated into practical tools, even though they may appear at first to be too conceptual for practical application. As a matter of fact the concepts of “Cindynic situation” and “hyperspace of danger” allow for the identification of divergences between groups of stakeholders in a given situation and thus allow for the anticipation of “major uncertainties” and to be able to work on them to reduce their likelihood and/or their negative consequences (threats) while enhancing the positive consequences (opportunities).

This scientific approach to perils and hazards was initiated in December 1987 when a conference was called at the UNESCO Palace. The name “Cindynics” was coined from the Greek word “kindunos”, meaning hazard. Many industrial sectors were in a state of shock after major catastrophes like Chernobyl, Bhopal, and Challenger. They offered an open field for experience and feedback looping. Since then, Cindynics continues to grow through teaching in many universities in France and abroad. The focal point is a conference organized every other year. Many efforts have been concentrated on axiology and attempts at objective measures. Before his death in December 2008, Professor Georges-Yves Kervern reviewed the presentation that follows (see bibliography) in the light of the most recent developments in Cindynics through the various Conferences, until September 2008.

2.2.1 Basic Concepts

The first concept, situation requires a formal definition. This in turn can be understood only in the light of what constitutes a peril and hazards study. According to the modern theory of description, a hazardous situation (Cindynic situation) can be defined only if:

The field of “hazards study” is clearly identified by

- Limits in time (life span).

- Limits in space (boundaries).

- Limits of the actors' networks involved.

The perspective of the observer studying the system. At this stage of the development of the sciences of hazards, the perspective can follow five main dimensions.

-

First dimension: Memory, history – Statistics (the space of statistics)

This consists of all the information contained in the data banks of the large institutions, feedback from experience (Electricity of France power plants, Air France flights incidents, forest fires monitored by the Sophia Antipolis Centre of the École des Mines de Paris, claims data gathered by insurers and reinsurers).

-

Second dimension: Representations and models drawn from facts – Epistemic (the space of models)

This is the scientific body of knowledge that allows for the computation of possible effects using physical and chemical principles, material resistance, propagation, contagion, explosion and geo-Cindynic principles (inundation, volcanic eruptions, earthquake, landslide, tornadoes and hurricane, for example).

-

Third dimension: Goals and objectives – Teleological (the space of goals)

This requires a precise definition by all the actors, and networks involved in the Cindynic situation of their reasons for living, acting and working.

In truth, it is an arduous and tiresome task to express clearly why we act as we act, what motivates us. However, it is only too easy to identify an organization that “went overboard” only because it lacked a clearly defined target. For example, there are two common objectives for risk management “survival” and “continuity of customer (public) service”. These two objectives lead to a fundamentally different Cindynic attitude. The organization, or its environment, will have to harmonize these two conflicting goals. It is what we call “social transaction”, which is hopefully democratically solved.

-

Fourth dimension: Norms, laws, rules, standards, deontology, compulsory or voluntary, controls, etc. – Deontological (the space of rules)

This includes all the normative sets of rules that make life possible in a given society. For example, the need for a highway code was felt as soon as there were too many automobiles to make it possible to rely on courtesy of each individual driver: the code is compulsory and makes driving on the road reasonably safe and predictable. The rules for behaving in society, like how to use a knife or a fork when eating, are aimed at reducing the risk of injuring one's neighbor as well as a way to identify social origins.

On the other hand, there are situations in which the codification is not yet clarified. For example, skiers on the same track may be of widely different expertise thus endangering each other. In addition some use equipment not necessarily compatible with the safety of others (cross country skis and snowboards, etc.). How to conduct a serious analysis of accidents on skiing domains? Should experience-drawn codes be enforced? How can rules be defined if objectives are not clearly defined beforehand? Should we promote personal safety or freedom of experimentation?

-

Fifth dimension: Value systems – Axiological (the space of values)

It is the set of fundamental objectives and values shared by a group of individuals or other collective actors involved in a Cindynic situation.

As an illustration, when the forefathers declared that “the motherland is in danger”, the word motherland, or “patria” (hence the word patriot), meant the shared heritage that, after scrutiny, can be best summarized in the fundamental values shared. The integrity of this set of values may lead the population to accept heavy sacrifices. When the media use the word apocalyptic or catastrophic, they often mean a situation in which our value system is at stake.

Figure 2.1 Hyperspace of Danger – the result of the look.

These five dimensions, or spaces, can be represented on a five-axis diagram and Figure 2.1 is a representation of the “hyperspace of danger”.

In combining these five dimensions in a different way – these five spaces – one can identify some traditional fields of study and research.

Combining facts (statistics) and models gives the feedback loop so crucial to most large corporations' risk managers.

Combining objectives, norms and values leads to practical ethics. Social workers have identified authority functions in this domain. These functions are funded on values that frame the objectives and define norms that they enforce hereafter. If there is no source of authority to enforce the norms, daily minor breaches will soon lead to major breaches and soon the land will dissolve into a primitive jungle.

This new extended framework provides a broader picture that allows visualizing the limitations of the actions too often conducted with a narrow scope. Any hazard study can be efficient only if complete, i.e. extended to all the actors and networks involved in the situation. Then, the analysis must cover all of the five dimensions identified above.

2.2.3 Dysfunctions

The first stage of a diagnostic to be established as described above consists in identifying the networks and their state in the five dimensions or spaces of the Cindynic model. The next step will be to recognize the incoherencies, or dissonances, between two or several networks of actors involved in a given situation.

These dissonances must be analyzed from the point of view of each of the actors. It is therefore necessary to analyze dissonances in each dimension and between the dimensions. In this framework, the risk control instrument we call prevention is aimed at reducing the level of hazard in any situation. In a social environment, for example, some actors may feel that an “explosion is bound to occur”. This is what is called the Cindynic potential. The potential increases with the dissonances existing between the various networks on the five spaces.

A prevention campaign will apply to the dissonances: an attempt at reducing them without trying to homogenize all five dimensions for all the actors. A less ambitious goal will be to attempt to develop for each dimension a “minimum platform” shared by all the actors' networks thus ensuring a common set of values as a starting point. In other words, it is essential to find:

- Figures, facts or data, accepted by the various actors as a statistical truth.

- Some models, as a common body of knowledge.

- Objectives, that can be shared by the various actors.

- Norms, rules or deontological principles that all may agree to abide by.

- Values, to which all may adhere, like solidarity, no exclusion, transparency and truthfulness.

The minimum foundation is to establish a list of points of agreement and points of disagreement. Developing a common list of points of disagreement is essential.

The definition of these minimum platforms is the result of:

- Lengthy negotiations between the various actors' networks; and, more often

- One particular network that acts as a catalyst or mediator. It is the coordinator of the prevention campaign for the entire situation.

The “defiance” between two networks, face to face, has been defined as a function of the dissonances between these two networks following the five dimensions. Establishing confidence, a trusting relationship, will require the reduction of the dissonances through negotiations, which will be the task of the prevention campaign. This process can be illustrated by three examples.

Family systematic therapy: Dr. Catherine Guitton8 focused her approach on dissonances between networks:

- The family requesting therapeutic help.

- The family reunited with the addition of two therapists.

When healing is reached on the patient pointed to by the family, the result was obtained thanks to work on the dissonances rather than a direct process on the patients themselves.

Adolescents and violence: Dr. M. Monroy's9 research demonstrates that violence typically found in the 15–24 age group is related to a tear, a disparity along the five dimensions. This system can be divided into two sub-systems between which a tremendous tension builds up.

- The traditional family with its set of facts, models, goals, norms and values.

- An antagonistic unit conceived by the adolescent, opposed, often diametrically and violently, to the “family tradition”.

These dissonances can lead the adolescent to a process of negotiation and aggression with violent phases in which he will play his trump card, his own life. From this may stem aggressions, accidents and even, sometimes, fatal solutions of this process of scission, specific to adolescence.

The case of the religious sects: It is during this process of scission that the success of some sects in attracting an adolescent following may be found. Their ability to conceal from the adolescents their potential dangers comes from the fact they sell them a ready-made “turn-key” hyperspace. The kit, involving all five dimensions, is provided when the adolescent is ripe. As a social dissident, any adolescent needs to develop his own set of references in each of the five dimensions.

Violence in the sects stems from the fact that the kit thus provided is sacred. The sacredness prevents any questioning of the kit. Any escape is a threat to the sacredness of the kit. Therefore, it must be repressed through violence, including brainwashing and/or physical abuse or destruction, as befits any totalitarian regimes that have become masters in large-scale violence.

In a recent book on the major psychological risk (see Bibliography) where the danger genesis in family is analyzed according to the Cindynic framework, Dr. M. Monroy tries to grasp all the issues by numbering all the actors involved in most of these situations.

| Network I | Family |

| Network II | Friends and peers |

| Network III | Schooling and professional environment |

| Network IV | Other risk takers or stakeholders (bike riders, drug users, delinquents) |

| Network V | Other networks embodying political and civilian society (Sources of norms, rules and values) |

| Network VI | Social workers and therapists |

This list of standard networks allows spotting the dissonances between them that build the Cindynic potential of the situation.

In the case of exposures confronting an organization, an analysis of the actors' networks according to the five dimensions facilitates the identification of the “deficits” specific to the situation. For example, the distances between what is and what should be provides an insight of what changes a prevention campaign should bring about. These deficits should be identified through a systemic approach of hazardous situations. It can be:

- Total absence of a dimension or even several (no data available).

- Inadequate content of a dimension (an objective such as “let us have fun”).

- Degeneration, most often a disorder, of a dimension (Mafia model in Russia).

- Blockade in a plan combining two dimensions:

- Blockade of feedback from experience (dimensions statistics and models).

- Ethical blockade of authority functions insuring that rules are respected in the social game (dimensions norms and values).

- Disarticulated hyperspace in the five dimensions creating isolation, lack of cohesiveness between the dimensions. (Fiefdoms splitting a corporation).

These deficits always appear in reports by commissions established to inquire on catastrophes. It is striking to realize how all these reports' conclusions narrow down to a few recurring explanations.

How do these situations change? Situations with their dissonances and their deficits “explode” naturally unless they change slowly under the leadership of a prevention campaign manager.

In the first case, non-intentional actors of change are involved. The catastrophic events taking place bring about a violent and sudden revision of the content of the five dimensions among the networks involved in the “accident”. Usually all five dimensions are modified: revised facts, new models, new goals, implicit or explicit, new rules, and new values.

In the second case, that all organizations should prefer, the transformer chooses to act as such. He is the coordinator of the negotiation process that involves all the various actors in the situation. Deficits and dissonances are reduced through “negotiation” and “mediation”. The Cindynic potential is diminished so that it is lower than the trigger point (critical point) inherent to the situation.

2.2.3 General principles and axioms

Exchanges between different industrial sectors, Cindynic conferences and the research on complexity by Professor Le Moigne10 (University of Aix en Provence, derived from the work of Nobel Prize winner, Herbert A. Simon11) have developed some general principles. The Cindynic axioms explain the emergence of dissonances and deficits.

- CYNDYNIC AXIOM 1 – RELATIVITY: The perception of danger varies according to each actor's situation. Therefore, there is no “objective” measure of danger. This principle is the basis for the concept of situation.

- CINDYNIC AXIOM 2 – CONVENTION: The measures of risk (traditionally measured by the vector Frequency – Severity) depend on convention between actors.

- CINDYNIC AXIOM 3 – GOALS DEPENDENCY: Goals are directly impacting the assessment of risks. The actors in the networks may have conflicting perceived objectives. It is essential to try to define and prioritize the goals of the various actors involved in the situation (insufficient clarification of goals is a current pitfall in complex systems).

- CINDYNIC AXIOM 4 – AMBIGUITY: This states that there is always a lack of clarity in the five dimensions. It is a major task of prevention to reduce these ambiguities.

-

CINDYNIC AXIOM 5 – AMBIGUITY REDUCTION: Accidents and catastrophes are accompanied by brutal transformations in the five dimensions. The reduction of the ambiguity (or contradictions) of the content of the five dimensions will happen when they are excessive. This reduction can be involuntary and brutal, resulting in an accident, or voluntary and progressive achieved through a prevention process.

The theories by Lorenz on chaos and Prigogine on bifurcations offer an essential contribution at this stage. It should be noted that this principle is in agreement with a broad definition of the field of risk management. It applies to any event generated or accompanied by a rupture in parameters and constraints essential to the management of the organization.

- CINDYNIC AXIOM 6 – CRISIS: This states that a crisis results from a tear in the social fabric. This means a dysfunction in the networks of actors involved in a given situation. Crisis management exists in an emergency reconstitution of the networks. It should be noted that this principle is in agreement with the definition of a crisis as included here above and the principle of crisis management stated.

- CINDYNIC AXIOM 7 – AGO-ANTAGONISTIC CONFLICT: Any therapy is inherently dangerous. Human actions, medications are accompanied with inherent dangers. There is always a curing aspect, reducing danger (cindynolitic), and an aggravating factor, creating new danger (cindynogenetic).

The main benefit of the use of these principles is to reduce the time lost in fruitless unending discussions on:

- The accuracy of the quantitative evaluations of catastrophes – Quantitative measures result from conventions, scales or unit of measures (axiom 2);

- Negative effects of proposed prevention measures – In any action positive and negative impacts are intertwined (axiom 7).

2.2.4 Perspectives

In a Cindynic approach, hazard can be characterized by:

- Various actors' networks facing hazardous situations.

- The way they approach the whole situation.

- The structuring of these approaches following the 5 dimensions (Statistics, models, objectives, norms and values).

- The identification of “dissonances” between the various actors' networks.

- The deficits that impact the dimensions.

Dissonances and deficits follow a limited number of “Cindynic principles” that can be broadly applied. They also offer fruitful insights to measures to control exposures that impact the roots of the situation rather than, as is too often the case, reduce only the superficial effects.

For more than a decade now, the approach has been applied with success to technical hazards, acts of God and more recently on psychological hazards in the family and in the city. It can surely be successfully extended to situations of violence (workplace, schools, neighborhoods, etc.). In some cases, it will be necessary to revisit the 7 principles to facilitate their use in some specific situations.

The objective is clear: Situations that could generate violence should be detected as early as possible, they should then be analyzed thoroughly, their criticality reduced and, if possible, eliminated.

Cindynics offer a scientific approach to anticipate risks, act and improve the management of risks. Thus, they offer a new perspective to the risk management professional, they dramatically enlarge the scope of his/her action in line with the trend towards holistic or strategic risk management while providing an enriched set of tools for a rational action at the roots of danger.

Bibliography

Kervern, G-Y. (1993) La Culture Réseau (Ethique et Ecologie de l'entreprise), Paris: Editions ESKA.

Kervern, G-Y. (1994) Latest Advances in Cindynics. Economica.

Kervern, G-Y. (1995) Éléments fondamentaux des cindyniques. Economica.

Kervern, G-Y. and Rubise, P. (1991) L'archipel du danger. Introduction aux cindyniques. Economica.

Kervern, G-Y. and Boulenger, P. (2008) CINDYNIQUES Concepts et mode d'emploi. Economica.

Kervern, G-Y. The Evil Genius in Front of the Risk Science: The Cindynics. Risque et génie civil. Colloque, Paris, France (08/11/2000).

Wybo, J-L. et al., Introduction aux Cindyniques. Paris (France): ESKA, 1998.

2.3 RISK ASSESSMENT OR EXPOSURE DIAGNOSTIC

Jean-Paul Louisot

Formerly Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Directeur pédagogique du CARM Institute, Paris, France

2.3.1 Foreword

The purpose of this article is to zoom in on a subject not really addressed in the RM Standards published worldwide, including ISO 31000; it proposes a practical tool for identifying, analysing and prioritizing the portfolio of exposures, and opportunities, as well as threats that confront any organization that envisions its future.

The “space of exposure” will prove a powerful tool for all embarking in the ERM (Enterprise-wide journey) to help “lift the fog of uncertainties in decision making and implementing” to paraphrase a recurring theme in Felix Kloman's12 conferences and presentations.

2.3.2 Threats and Opportunities: How to deal with uncertainty in a changing world?

The future is never known with certainty, “Who knows what tomorrow will bring?” but managing organizations means making decisions, enlightened by information drawn from different methods that shed light on the future.

For a long time, men have tried to improve tomorrow by influencing the forces that guide the future, or by offering sacrifices to the gods. It was only at the end of the seventeenth century, that Pascal and Fermat and their successors, including Bernoulli, started developing ways to open the gates to the future by drawing from past and present experiences. Probability and trend analysis were the first approaches to see through the “cloud of unknowing”.13

During the last decade of the twentieth century, the development of risk management, resting on more elaborate forecasting models, seems to have focused on only the downside aspect of risk, the threats, and has slowly put aside the upside, usually called “opportunities”. Confronted with the uncertainties of the future, organizations are rediscovering that “threats” and “opportunities” – the yin and the yang of risk – represent two sides of the same coin.

It has never been more important that directors and officers, as well as investors, remember the basics of economic and financial theories. Risk is inherent to the undertaking of any human endeavor. Indeed, it is the acceptance of a significant level of risk that provides the type of return on investment that is expected by investors. The theory of finance defines the expected rate of return as the sum of two components:

Basic return, of the risk less investment (usually measured by the US treasury bond rate of similar maturity); and

The risk premium, i.e. an additional return that the investor deserves for having accepted a higher volatility of profit, to enhance some societal goal, like improved technology, a new drug, etc.

Of course, all volatilities are not “equal”. Traditionally, scientific authors distinguish between probabilistic future (risk) and non-probabilistic future (hazard).

Most of the time, deciders are in the first situation (risk) when they have enough reliable data to compute law of probability or draw a trend line for future events and can define confidence intervals, i.e. limits between the likely and the unlikely future. For example, in analysing past economic conditions, it should be possible to have a reasonable idea of the numbers of cars to be sold in the EU, in the US or in Australia. The booming and recent Chinese market may not lend itself easily to this type of reliable trending. While an automobile company can predict with a fair degree of precision its mature market, forecasts are far more volatile in emerging markets. Therefore, there is a higher risk to market cars in emerging markets, but the reward may be much higher in case of success.

On the other hand, when launching a new model, especially if some defects are revealed in the first year of sales, it is much more difficult to justify the investments if reliable forecasts can prove the existing models will be profitable. Banks have experienced a similar situation when they embarked on the management of operational risks to comply with the new Basel II14 requirements. When no data bank is at hand, experts' opinions will have to be formalized using a Bayesians network15 approach and scenarios.

As a matter of fact the above examples might be considered as incorrect for looking only at the negative side of risks. However, operational risks are also a significant opportunity for competitive advantage for the banks that invest more than others in this endeavor. Not only are banks likely to “save” on internal funds, they may even gain expertise that could benefit their clients in the longer term.

A current trend in risk-management is to minimize risk silos in order to reach a real global optimization of the management of risk, taking into account for each unit, each process, each project both threats and opportunities. The organization is analysed as a portfolio of risks with an upside and downside that must be optimized, much as an investor would optimize a personal portfolio of shares.

In practice, this integration of all risks is achieved more easily for the financial consequences at the risk financing level. More and more economic actors consider their risk financing exercise as part of their overall long-term financial strategy. However, it is possible to integrate risk assessment and loss control provided all in charge (at whatever level) are included in the risk management process. This integrated approach is now called ERM and within ERM the managers become “risk owners”. The globalization of risk management is ensured through the principle of subsidiarity: the directors and officers should deal only with the exposures that have impact on the strategy, assured that the risk management process implemented throughout the organization will take care of “minor” threats and seize “tactical” opportunities. That should sound familiar to many in Australia, as this is a fundamental tenet of management guidelines in the Australian/New Zealand Framework (companion to AS/NZ 4360 used in various versions since 1995 and finally replaced since 2009 by the adoption of ISO 31000 under the name AS/NZ 31000:2009).

What Do We Mean by Risk?

Risk management, risk mitigation and risk financing – indeed the word “risk” is used by all risk management professionals as well as by many others in their daily life. But do we really know what we mean by risk? The Australian RM standard states, “…the chance of something happening that will have an impact on objectives”, whereas ISO 31000 proposes an even wider definition: “the effect of uncertainties on objectives”. But this is not the final word because there are other common understandings of the word risk.

Risk (pure, speculative, hybrid)

This definition is most commonly used by specialists, which is compatible with the definition of risk in the ISO 31000:2009 standard, depending on the nature of the consequences involved.

Systematic and Unsystematic Risk

Systematic risk (i.e. non diversifiable) is the result of non-hazardous causes that may happen simultaneously. That means that it does not lend itself to diversification. As an example, all economic actors can be affected by a downturn in the economy or a rise in interest rates.

Unsystematic risk (i.e. diversifiable) is the result of hazardous causes and lends itself to probabilistic approaches. They are specific to each individual economic entity and offer the possibility to build a “balanced portfolio” of risk sharing. Therefore, insurance cover might be designed to cover them.

Insurable Risk

This is a more restrictive definition as it refers to an event for which there is an insurance market. Furthermore the work “risk” is used commonly by insurance specialists to refer to the entity at risk, the peril covered, the quality of the entity risk management practices (level of risk), and the overall assessment of a site (“good risk for its category”).

One must be cautious because this commonly used word may have totally different meanings for different individuals. This requires all involved to be aware of that diversity when communicating and consulting in the boardroom or with different stakeholders.

This reality must be kept in mind when communicating about risks, whatever the media or audience. Any “risk management” professional should be always aware of one of the main challenges and hazards of risk awareness and understanding: how risk is perceived by stakeholders and decision makers is more important than any “scientific” assessment of risk. Recommendation: Whenever possible avoid using such an uncertain word; another, less common, should be substituted: exposure, threat, opportunity, peril, impact, etc., are acceptable alternatives but there is a caveat here as well – the use of any term depends on which facet of “risk” is the subject of the discussion! Sometimes, a specifically crafted professional word needing some explanation may prove safer than a commonly used word that may be understood differently within a group. A common taxonomy of terms is vital not only for understanding but also in developing consistent data across the organization.

What is an Exposure?

The word “risk” has several meanings and can be misleading when used in a professional context, especially in the case of an organization communicating on risks with a broader audience. Therefore, practitioners and academics in risk management need to define a more precise concept. This is what George Head, who developed the Associate in Risk Management designation, attempted with the word “exposure” as early as 1975. However Head's definition considered only the downside of risks. A new definition more appropriate for today's global approach is required:

An exposure is characterized by the consequences on its objectives resulting from the occurrence of an unexpected (random) event that modify the resources of an organization.

This definition allows for an exposure to be clearly identified with three factors:

- Risk Object: The resource “at risk” that the organization needs to reach its goals and missions. We have defined 5 classes of resources: Human, Technical, Information, Partners and Finance as well as the expression “Free” for those taken from the environment without a payment (externalities)(these classes are reviewed below).

- Random Event (Peril): It is “what” may happen that would modify permanently or temporarily the level of the organizational resources resulting either in an opportunity (sudden increase in the level or quality of the resource) or a threat (sudden decrease in the level or quality of the resource). The likelihood of the event will lead to a measure of the “frequency”.

- Potential Impact (Severity): Most organizations strive to quantify the financial impact of the exposure identified through the resources “at risk” and random events. However, the goals and objectives of a given organization are not all necessarily translatable in financial terms. For example: ethics and corporate social responsibilities must be also taken into account. However, one should keep in mind that the “severity” is nearly always measured in financial terms.

However, it should be noted that not all consequences touch only the organization under

study; therefore, especially for the downside risk, it is essential to distinguish:

- Primary & Secondary damages: i.e. the impact on the organization itself and its resources through a loss of assets or potential loss of revenues.

- Tertiary damages: i.e. the impacts on all third parties and the environment. Special attention should be given to impacts on the organization's partners (both downstream, customers or clients, upstream, suppliers or subcontractors, and temporary for special projects). The analysis should extend to all consequences and not be limited to liabilities, as long-term consequences with no immediate legal implication can prove costly, specifically for reputation. On the other hand “tertiary damages” involving contractual, tort or penal liabilities will impact the organization's resources through its executives, employees, finances and even its “social licence to operate”.

- “Quaternary” damages: those long-term impacts on the trust and confidence of “stakeholders” that may eventually taint or destroy the organization's reputation, and its “social licence to operate”.

In a complete analysis, the upside risk should be included, as the threats to one organization may well create an opportunity for another organization!

Once the concept of “exposure” is clearly mastered, it provides a model to develop a systematic approach to managing risks. As a result, any organization will be seen as a portfolio of exposures, with a special attention to those that represent challenges to the optimal implementation of a strategy. The risk register suggested by the Australian standards appears as a list of “risk assets”. Therefore, the decision tools developed in finance for the management of investment portfolios – the portfolio theory – are pertinent towards implementing a rational decision making process in risk management that will ultimately lead to sound governance.

Once again, the concept of exposure constitutes a step towards the integration of risk management in an organization's strategic process by leveraging opportunities and mitigating threats, not only as they are anticipated at the development stage but also as they materialize along the path of the implementation towards achieving strategic goals.

What are the Resources at Risk?

Any organization can be defined as a dynamic combination of resources pulled together to reach its goals and objectives. Therefore, developing and communicating these objectives is at the heart of any risk management, indeed any management, exercise. This is the reason why, for risk management purposes, we have defined an organization as a portfolio of exposures, both threats and opportunities, to be managed in the most efficient manner to reach these goals and objectives under any circumstances. Within the context of a competitive economy, efficiency means either to reach the most ambitious objectives with the available resources or reach the assigned goals with as little resource as possible.

While many would agree on this simple approach, it must be determined how many classes of resources should be considered. The model proposed here is limited to a small number of classes, five, that will take into account practically all the resources involved in the management of an organization, which can be used to list the resources in a specific organization. This will permit a systematic and global identification because the classes of exposures will be directly linked to the classes of resources. Each of these classes calls for specific forms of loss control measures. Thus, the five classes of resources are as follows:

- H = Human: This includes all personnel linked to the organization through a labor or an executive contract. Their specific experiences and competencies are an asset for the organization although they are not always assessed and valued in the accounts. For this resource, elements like age, gender, and marital status that may have an impact on the actual capacities should be carefully monitored. In other words, the exposure associated with the human resources should be investigated both as key persons, and labor costs, or social liability (pensions and employee benefits). The main element to risk management is linked with what is now usually known under the term “knowledge management” and sometimes talent management. Therefore, it does not refer only to technical skills but also to social skills and attitude that are essential to embedding risk management throughout an organization.

- T = Technical: These are buildings, equipment and tools, i.e. all physical assets under the direct control of the organization. The legal status of those assets is of secondary importance; the organization may own, lease, rent them or simply keep them for a third party. What is essential is that the organization has complete responsibility for those items. Even if there are contractual terms over how to manage them, the organization is completely in charge of the management of risks to them and from them.

-

I = Information: All the information that flows throughout the organization, in whatever form (electronic, paper, and human brains). This may cover information concerning the organization itself, information regarding others (medical files for patients in a hospital) but also what others may want to try to know, and what the organization wants to know about others (economic intelligence of different forms). Also included are intangibles like goodwill, credit score, rating agency evaluation, and other financial or cross-discipline metrics.

Furthermore, the ability to do business depends on the trust established with others: the perception that all the stakeholders have of the organization is an essential “asset”, the risks to reputation have become an important item in boards' risk agendas.

- P = Partners (upstream and downstream): They are all the economic partners that the organization is intertwined with (and recognized by the World Economic Forum) and specifically upstream (suppliers, service providers and sub-contractors), and downstream (customers and distribution channels). Of those some are key, those without which the organization could not continue to operate, or operate efficiently, and they must be identified clearly if the dependencies on the supply chain are to be treated appropriately. It is an essential source of exposure in an economy where outsourcing has become so important. In some organizations they include volunteers contributing their time and talent, sometimes money, to the organization.

- F = Financial: This comprises all the financial streams that flow in and out of the organization, short-term (cash, liquid assets, short-term liabilities) and medium or long-term (capital and reserve, long-term debt, project financing, etc.). In other words, all the risks linked with the financial strategy of the organization and the balance between return and solvency.

- Free Resources = However, the analysis would fall short if the organization did not take into account its non-contractual exchanges with the environment, i.e. those resources that the organization does not pay directly for and yet that could prevent it from operating smoothly. In other terms, these “free resources” that do not appear in the organization accounting books and yet are essential: air quality, access to sites, social licence to operate, etc. Further investigation of those would be warranted.

2.3.3 How to Manage the Risks Derived From Partners' Resources?

Market globalization has generated ever more complex webs that link many organizations worldwide through the externalization process. The large conglomerate has become more and more focused on conception, marketing and assembling parts from all over the world. Many smaller or medium size organizations are only one cog in a very complex supply network.

In most situations, we are confronted with a network of partners rather than a chain, indeed a cloud when the frontiers are not completely defined. This is the reason why procurement risk management has become the backbone of most organizations producing goods and services, while their production relies on an ever-expanding number of outsourced tasks.

Therefore, what “partners' resources” encompass are raw materials, parts, equipment and services as well as distribution networks on which organizations depend on a daily basis for their own operations. These resources can be grouped in three distinct categories:

- Upstream resources: These are purchased by suppliers, service providers and sub-contractors, and delivered to production sites by transporters.

- Lateral resources: These are goods and services provided to clients and that are integrated in complex systems, projects and products, of which your own contribution is part. You may not know them and yet there is a de facto solidarity that links you together. As an illustration you may produce tires that match a given sort of wheel and when the manufacturer goes bankrupt, your client does not need your tires anymore.

- Downstream resources: These are customers or intermediaries, including distribution networks and the transporters that deliver the goods, and financial institutions that guarantee the successful conclusion of transactions.

It is essential to clearly identify all the elements of this class of resources while conducting a risk management assessment as the same principles apply but with a major difference that the three categories have in common: the organization is dependent for its own security on the actions and attitudes that it cannot monitor daily as is the case for the resources under its direct command. In other words, consciously or unconsciously, the organization has “transferred” to a third party an essential part of its risk management activity. Therefore, the crucial question in procurement risk management is to find ways to ensure the organization's overall resilience should one of the “partners' resources” fail to be delivered, in time and to the quality desired.

The basic rule of thumb is not to be too dependent on one given partner, be it a supplier or a customer. Basic common sense applies here: “Don't put all your eggs in the same basket.” Most recommend having at least two or three sources at all time. However, this is not always possible, especially when there is a very advanced technology, patents, or some very specific know-how that can only be obtained from one source. Furthermore, the multiple sources must be balanced against the cost of maintaining several suppliers, with the advantage of them entering a competition to retain the organization's business. Finally, there is increased risk of information leaks if the relationship involves sharing trade secrets of any sort.

Beyond, this basic principle, the same rule applies upstream and downstream, which could be called the “3 Cs” rule.

- Choose – You must choose carefully the partners you want to do business with. First, you must evaluate if the products or services offered meet your needs in quality, quantity and timely delivery. Then you must investigate their financial strength, because a partner that would fail rapidly would be of no use. Furthermore, it is essential to assess their “ethical compatibility” with your own values, specifically those you stress when exchanges with stakeholders take place (one must remember that a major sports good manufacturer went through a difficult period in 1998 during the Football World Cup when it was revealed in the media that a supplier of a supplier was using underpaid, underage children to produce the balls).

- Contract – The quality of risk management throughout the partner's operations must be contractually sealed. It is even more imperative because there is no universally accepted standard so far, contrary to quality. It must provide for your access to site and documentation to ensure that proper risk management is designed and implemented. Also, the contract should resolve ahead of their occurrence any potential conflicts so that the partnership can remain harmonious even through difficult times. For many organizations, too much time is devoted by lawyers to defining the products or services involved in a contract, too little to solving conflicts ahead of time.

- Control – It is essential that staff regularly meet with the organization's partners and be kept informed of developments to make sure they remain the reliable sources its leaders wish to deal with. You must be aware of major changes in their leadership, their ownership, their environment and their strategy.

As far as lateral resources are concerned, unless you are a project leader, which is rarely the case for small or medium size organizations, they are typically partners you have not chosen and you may have no contract with whereas each of them has a contract with the leader. Therefore, the only way to ensure the quality of the risk management is through your common partner, project leader, large firm, etc. In your dealings with the team leader, you should have access to the list of all those involved in the project you share.

Finally, remember that when you transfer risks, you are still socially responsible for the well-being of those who are stakeholders in the overall process. If a member of the team betrays their trust, all the members of the team will suffer. In other terms, risks to reputation are never transferred!

2.3.4 Are There Any “Free” Resources? Taking into Account Externalities

In our global economy, who would dare to claim that there are resources that we do not pay for? Clearly any organization needs both internal and external resources that have been detailed in a previous question. By external we mean those exchanged with the economic partners both up and down stream. These resources are paid for. However, there are also non-transactional exchanges with the environment that are essential for the organization's development, even its survival. These resources received from the environment without direct financial compensation are labeled “free resources” insofar as they do not appear on the organization's accounting documents. However, the term environment is too broad and in each situation should be investigated:

- Physical environment: Comprising air, water and earth.

- Political, legal and social environment: This requires looking at all of the aspects of life conditions and society organization, including cultural differences.

- Competitive environment: This entails looking at all aspects of the current competition, technological breakthrough, and shift in consumers' tastes, but also substitutes for the organization's products and services. Furthermore, one should always analyse the reason for the appeal of our offering; the notion of “magnet site” allows for the investigation of the circumstances outside of our management sphere that are key to our success.

These exchanges represent what economists call “externalities” that are not part of any contractual transaction with economic partners. Remember that these externalities can be positive (society receives a benefit from a private transaction, which is additional to the private transaction), or negative (society incurs a cost additional to the private transaction). It should be noted that the domain of these externalities may vary from country to country; in terms of pollution, the development of codes to protect the environment has forced the “internalization” of the costs of cleaning sites or restricting contaminant releases as private producers have seen some “social costs” transferred to their operation.

It is crucial for any organization planning to diversify or enter new markets in any locale to be aware of its needs for “free resources” as they may not be available in the prospective locations and/or countries involved. More precisely, a very successful SME might well be unaware of the specific circumstances that led to success in its original location that may not be found in the proposed sites, or lost in the case of fusion or acquisition.

The concept can be illustrated with some specific situations keeping in mind that these are only common cases and that each individual organization must conduct a systematic analysis of its circumstances:

- There are industrial processes that use substantial amounts of “cooling water”; the water is released downstream with no chemical or biological pollution, but at a higher temperature than the intake upstream. Have we imagined extreme winters (the river is frozen), summers (a temperature that is too high does not allow for a correct biological exchange or fish cannot survive at the release temperature for lack of oxygen)? In a new proposed location, is there upstream a chemical plant that could release toxics with potential damage to our installation, or a production interruption?

- Throughout the plant, the air must be of a quality compatible with human life and even satisfying local ordinances regarding “workplace conditions”. Is there a neighboring plant that could release a toxic cloud? On the other hand some production processes require the atmosphere to be totally cleaned of any dust. Is it possible that very fine particles would slip through our filters polluting our products (like optical lenses or medical devices)?

- A single historic bridge is the only direct route to a factory. After a minor earthquake, concerns are raised as to its long-term robustness. Local authorities decide to limit its access to trucks of less than 5 metric tonnes. It may be that the new route from a key supplier to the factory is so much longer that delays and costs increases make the plant “uneconomical” with no easy remedy.

- Production in a new country, with substantial gains on wages and salary costs: but is the country politically sound? Is there any threat of nationalization should an opposition party seize power? Will the “social and political” climate remain favorable to foreign investment?

- The precaution principle14 is now incorporated into the French constitution. It is not yet clear what the consequences will be for the corporation whose domicile or activities are in France. Could it be that innovative products sold in France will in the future come from foreign companies?

- Local cultures may have an impact on the way business is conducted, be it only working hours. When entering a new country, a new province, has the organization questioned its commercial and human resources practices to align them with local customs, even beyond mere compliance to local legislation?