3

Select and Implement the Appropriate Risk Management Technique

Risk treatment occurs after risks have been identified, evaluated and assessed. Treatment can include avoidance, acceptance, mitigation, transfer (for example, insurance), separate, and optimize and exploit. ERM often produces novel risks that require novel treatment. What organizations are beginning to understand is that proper treatment can be used not just to reduce the cost of loss but also increase the bottom line. Examples of exploitation include venturing into niche markets where others have been unable to control loss, or using risk control techniques to increase reputation and by doing so increase revenue and the acquisition of more profitable business.

3.1 RISK TO REPUTATION

Sophie Gaultier-Gaillard

Associate Professor at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University, Paris

Jean-Paul Louisot

Formerly Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Directeur pédagogique du CARM Institute, Paris, France

Jenny Rayner

Director of consulting firm Abbey Consulting

Warren Buffett (Chairman and CEO, Berkshire Hathaway) once said: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that you'll do things differently.” The teachings to draw from this quote are manifold. Firstly, it demonstrates that risk is a social construct (Douglas and Wildawsky, 1982). Secondly, it shows that people tend to perceive it as a threat and totally miss the dual aspect of risk, i.e. the potential opportunities. Thirdly, it implies that people should react and learn from past errors and improve their behavior.

But is this what happens in real life? At the start of the twenty-first century managing reputational risk has become a major preoccupation for businesses in the private, public and not-for-profit sectors. A survey conducted by Aon in 20071 rated damage to reputation as the number one global business risk, although half of the survey's respondents said they were not prepared for it.

In the aftermath of the Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat and other corporate catastrophes, more stringent corporate governance and regulatory compliance requirements, strengthened regulator powers, the growing influence of pressure groups and rising stakeholder expectations have sharpened the focus on business reputation. Added to this, the advent of real-time global telecommunications and 24/7 media scrutiny and social media can result in an apparently minor incident in a far-flung part of a company's operations hitting the international headlines and provoking a major crisis.

Enjoying a good reputation yields many rewards: not least the continuing trust and confidence of customers, investors, suppliers, regulators, employees and other stakeholders, the ability to differentiate the business and create competitive advantage. A bad reputation, conversely, can result in a loss of customers, unmotivated employees, shareholder dissatisfaction and ultimately the demise of the business itself.

The challenge of managing reputation and its associated risks is well illustrated by the Warren Buffett quote at the start of this article. Hard-earned reputations can be surprisingly fragile and can be tarnished or irrevocably damaged as a result of a moment's lapse of judgment or an inadvertent remark. That is why it is so vital to manage risks to reputation as rigorously as more tangible and quantifiable risks to the business.

3.1.1 What is Reputation?

This question is worth asking because there is still some confusion between brand and reputation. Here we reserve the word “reputation” to cover all aspects of the stakeholders' perception of an organization, whereas the name “brand” applies more to a specific product or service. Therefore, a company's reputation may incorporate several brands and be influenced by them. It is therefore of interest to the “reputation scholar” to study brand building and maintaining. A recent study2 shed an interesting light on a five-stage process stressing for brands attributes similar to those described here for reputation:

- Differentiation: How to stand out from competition?

- Positioning: Why do consumers and employees need this new product in their lives?

- Personality: How is the message communicated to employees and consumers? Are they involved in a dialogue through a consultation process?

- Vision: How do we convince consumers and employees of the high-minded values embedded in the brand?

- Added value: What do the consumers and the employees get, that they could not with another product (competition/substitution)?

According to the Compact Oxford English Dictionary, reputation is “the beliefs or opinions that are generally held about someone or something”. Depending on the field studied, reputation may have different meanings (Gaultier-Gaillard and Louisot, 2006) but always constitutes an intangible asset. The main question should then be to determine what makes a good reputation. The theory is simple: an organization enjoys a good reputation when it consistently meets or exceeds the expectations of its stakeholders. A bad reputation results when the organization's words or deeds fall short of stakeholder expectations. This concept is expressed in the reputation equation in Figure 3.1 below.

Figure 3.1 The Reputation Equation3

Stakeholder expectations are shaped by their beliefs about what a business is and what it does. These beliefs are influenced by what the business says about itself and by what others say about it. Stakeholders then measure their actual experience of how the business acts against their expectations.

A good reputation is achieved when there is congruence between a business's purpose, its goals and values (what it professes to be), its conduct and actions (what it does in practice) and the experience and expectations of its stakeholders. Maintaining a good reputation therefore requires continuing identification and management of emerging gaps between experience and expectations and between claims and reality using a risk-oriented approach.

3.1.2 Why is Reputation Valuable?

A business's reputation is valuable on two counts: first, its intrinsic current value as an intangible asset and secondly, its ability to create – or destroy – future value.

Reputation will not appear as a separate item on a business's balance sheet but generally represents a significant proportion of the difference between market value and book value (minus any quantifiable intangibles such as trademarks and licences). As total intangibles now often account for some 75% or more of market value, reputation is, for many businesses, their single greatest asset.

A good reputation not only underpins a business's continuing licence to operate, but provides it with a licence to expand and generate new partnerships and income streams, for example, by helping to secure preferred partner status on future projects or by enabling premium pricing for products and services. Reputation is often not only a business's single greatest current asset but also a potential source of competitive advantage and a key determinant of future business success (see Figure 3.2).

|

Reputation may impact:

|

Figure 3.2 Reputation impact on stakeholders' behavior

Reputation is also a critical business differentiator. As Alan Greenspan, former US Federal Reserve Chairman, has observed: “In today's world, where ideas are increasingly displacing the physical in the production of economic value, competition for reputation becomes a significant driving force propelling our economy forward. Manufactured goods often can be evaluated before the completion of a transaction. Service providers, on the other hand, usually can offer only their reputations.”4 This is particularly true of service industries where the end product is invisible, as the present crisis illustrates clearly and gives an ironical twist to Greenspan's assertion. Insurers, for example, are in the business of promising to pay out on a claim at an unspecified date in the future. The policyholder cannot assess the insurer's willingness and ability to fulfil the promise at the time of purchase and may have insufficient grasp of the fine detail of a complex policy. Their purchase decision can therefore only be made based on the business's reputation and the level of trust and confidence it engenders. If the business's reputation is eroded, and stakeholder trust and confidence diminish as a result, the insurer may find that policyholders rush to surrender their policies.

The queues of customers desperate to withdraw savings outside Northern Rock's branches in August 2007, jammed telephone lines and a website crash are a graphic example of how quickly stakeholder trust can evaporate and a corporate reputation can crumble amidst rumors of financial difficulties. British Government assurances did little to restore public confidence and this first run on a British bank since Victorian times led ultimately to the temporary nationalization of Northern Rock and attacks on the reputations of the Bank of England and the Financial Services Authority, the company's regulator.

Perhaps the greatest benefit of a “good” reputation is its capacity to provide a reserve of goodwill (often called “reputational capital” or “reputational equity”) that can help the business withstand future shocks and crises. Such reputational capital, which underpins stakeholder trust and confidence, can act as a buffer at times of crisis and persuade stakeholders to give a business the benefit of the doubt and a second chance. In the case of Northern Rock, the shock was too severe, should have been predicted and had too immediate an effect on customers for the bank to weather the storm.

3.1.3 The Stakeholder Perspective: Who Counts?

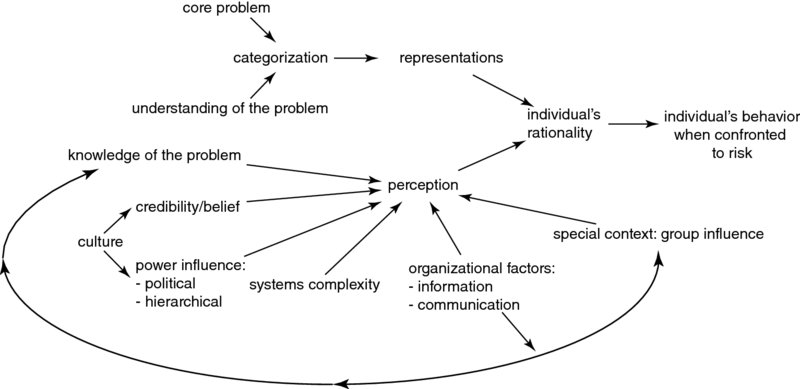

As the key to a good reputation is meeting stakeholder expectations, it is vital to establish who your most significant stakeholders are, what expectations they have of you and how they currently perceive you. Only then can you pinpoint any gaps and start to correct them. You might start by listing and then prioritizing your business's stakeholders – both internal (employers) and external (shareholders, investors, suppliers, customers, regulators, analysts, insurers, government, etc.). The relative importance of stakeholders will vary between sectors. For example, in heavily regulated sectors such as financial services the regulator is likely to be a key stakeholder. It also is vital to consider a sufficiently broad range of stakeholders to ensure that no major interest group is neglected, as the sole omission may prove to be the source of an unidentified killer risk. Their expectations depend on the sum of their perceptions and their representations. As reputational risk is a social construct, their expectations on reputational risk are also a social construct (see Figure 3.3).

3.3

3.3

Figure 3.3 Risks and perception5.

Once you have identified the main characteristics of the context where your stakeholders are, your prime focus should be on key players: those critical stakeholders with whom it is vital to maintain an active two-way dialogue so you can continuously track what they are thinking and saying about your business and what they expect of you, both now and in the future. Only in this way can a business truly identify not only its vulnerabilities but also opportunities to create competitive advantage.

3.1.4 Reputational Risk: Risk or Impact? Threat or Opportunity?

There is no such thing as reputational risk – only risks to reputation. The term “reputational risk” is a convenient catchall for all those risks, from whichever source, that can impact reputation. The source could be legal non-compliance, a data security lapse, an unexpected profit warning or unethical behavior in the boardroom.

This broad interpretation of reputational risk has a growing following compared with the school of thought that classifies reputational risk as a discrete class of risk in itself that should be isolated and managed. It requires a business to assess all risks for potential reputational impact and ensures that risks to reputation are fully integrated into the core business risk management framework, are reported alongside other business risks and receive attention from the right person at the right level. Reputational risks are not simply parcelled up and handed to the public relations department for action, although PR can play an important supporting role.

When discussing reputational risk, many organizations consider only the downside threats that could damage corporate reputation. However, uncertainty can also have positive outcomes and can present business opportunities, which, if exploited, can create competitive advantage and added value for a business. Climate change is a potential business threat but many firms have spotted and exploited the flip-side opportunity to create a competitive edge by developing green technologies and promoting themselves as environmental leaders in their sector.

Reputational risk can be defined as:

Any action, event or situation that could adversely or beneficially impact an organization's reputation.

3.1.5 Key Sources of Reputational Risk

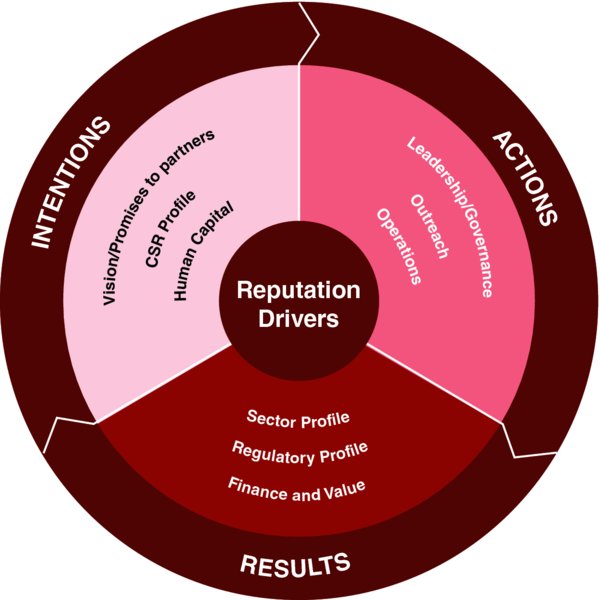

The most crucial step in managing reputational risk is the initial identification of those factors that could impact reputation, either positively or negatively. But there remains the question of finding a starting point. You may wish to consider the key drivers of reputation as defined by several well-respected reputation surveys around the world5 as they are likely to be the most fertile sources of reputational risk. These are distilled into nine drivers of reputation and sources of reputational risk in Figure 3.4.

3.4

3.4

Figure 3.4 Reputation drivers and source of risk. Reproduced with permission. Rayner, J. (2003). Managing Reputational Risk: Curbing threats, leveraging opportunities. Chichester: Wiley.

A useful question to tease out risks to reputation is: What newspaper headline would you least like to see about your business? And what event or situation could trigger it?

With increasingly complex supply chains and partnership arrangements and a wide range of customers in different sectors and territories, today's businesses need to consider all risks within the extended enterprise. Risks to reputation cannot be outsourced and should be borne and managed actively by the business itself. If a supplier's sub-contractor is found to be using child labor or a toll manufacturer slips a cheap toxic ingredient into a supposedly “green” product formulation the reputation of the company marketing the product will be tarnished, as companies including Nike and Mattel have learned to their cost.

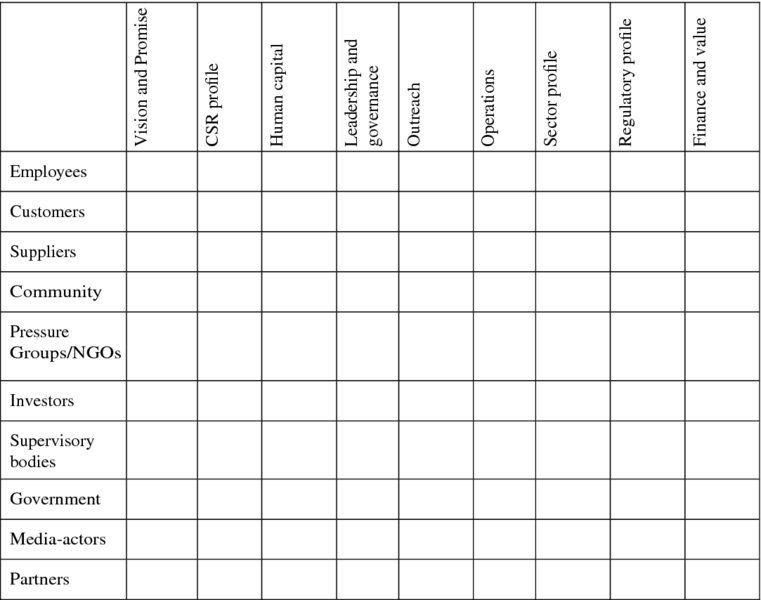

A good starting point is to consider each of the nine drivers of reputation in the light of the stakeholder group(s) that have an interest in it. This can be mapped on a reputation risk driver/stakeholder matrix (illustrated by Figure 3.5) to produce a “heat map” highlighting potential reputational hot spots that warrant further attention.

Figure 3.5 Stakeholders/reputation drivers. Reproduced with permission. Rayner, J. (2003) Managing Reputational Risk: Curbing threats, leveraging opportunities. Chichester: Wiley.

Each of the nine drivers of reputation must be examined in more detail, so as to understand better the interactions between them and to identify potential dissonances (see the article in this text on the Cindynic approach).

3.1.6 Implementing Risk Management for the Risks to Reputation

As the Cindynic framework indicates8 and the cases illustrate9 the risk management for risks to reputation is based on a few simple principles and trust of others is at the heart of any strategy. However, if the strategy seems relatively easy to develop, risk management for reputation is above all an art of execution and therefore some key elements to ensure success, or at least avoid abysmal failure can be summarized here.

3.1.7 Evaluating and Prioritizing Reputational Risks

“While reputation is ‘intangible’, damage to an institution's reputation (and the resulting loss of consumer trust and confidence) can have very tangible consequences – a stock price decline, a run on the bank, a ratings downgrade, an evaporation of available credit, regulatory investigations, shareholder litigation etc.”10

What makes risks to reputation particularly difficult to evaluate is the random nature of its occurrence. Often, an issue deemed minor by a business can cause severe reputational damage, whereas an apparently major issue can pass without comment. Geography can also play a part. A minor event at a distant manufacturing site in a developing country may attract little or no media or stakeholder interest, whereas that same event in the business's heartland can provoke a reputational storm.

An assessment of reputational impact also needs to take into account the resilience of corporate reputation. This will depend on the amount of “reputational capital” built with stakeholders and the nature and extent of the issue or risk. Was this a predictable and preventable incident, such as anti-competitive activity, bribery condoned by senior management or an accident resulting from blatant disregard for human safety? If so, stakeholders are unlikely to be forgiving. Or was it an unforeseeable occurrence, which could not have been avoided, such as 9/11 or natural disaster where stakeholders will be sympathetic? Even after such catastrophic events stakeholders expect businesses to learn and adapt. So, post 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, investors, regulators and customers now require businesses to have risk management systems and business continuity plans in place to counter the effect of such risks.

Another challenge in assessing impacts on reputation is that the initial impact of a risk crystallizing may be relatively small, perhaps a fine resulting from a minor breach of regulations. However, this may chip away insidiously at stakeholder trust. A series of minor bad news stories can have a cumulative effect whereby a “tipping point” is reached, after which stakeholders suddenly lose confidence, the business's share price plummets and current and all past misdemeanors are raked over in the ensuing media frenzy making it very difficult to recover.

Oil and gas company, BP, enjoyed a formidable reputation with investors and other stakeholders under the leadership of its much-admired former CEO Lord John Browne. Its hard-won reputation allowed it to withstand a number of crises in the early 2000s. However, the death of 15 workers and injury of 500 others when overfilled storage tanks exploded at BP's Texas City refinery in the US resulted in a massive loss of confidence in the company, a top-management shake-out and a new strategic approach.

Understanding precisely how stakeholders perceive your business at any point in time can help you judge whether you are approaching your reputational tipping point, where just one more bad news story could push you over the brink, and to evaluate reputational impact and respond accordingly.

It may be possible to place a monetary value on reputational risk, for example, via loss of future contracts/income; cost of loss of licence to operate; impact on Net Present Value (NPV); impact on share price; or impact on brand value. However, these cannot be applied to all reputational risks. Many businesses therefore use a qualitative approach to initially assess reputational impact (see Table 3.1, which uses a four-level scale), alongside financial and other relevant impact criteria. Both the short-term and longer-term impacts of a risk on the business's reputation should be considered, including the effect on stakeholder behavior and hence on the future value of the business.

Table 3.1 Assessing impact on reputation

| Low | Moderate | High | Very High |

| Local complaint/recognition | Local media coverage | National media coverage | International media coverage |

| Minimal change in stakeholders' confidence | Moderate change in stakeholder confidence | Significant change in stakeholder confidence | Dramatic change in stakeholder confidence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.1.8 Developing Risk Responses

The appropriate response to a risk impacting reputation will depend on its source (safety, project management, acquisition, IT security, and supply chain labor practices), whether it is a threat or an opportunity, its expected impact, the exposure relative to the business's risk appetite, whether the risk is treatable and the cost of treatment. The right response may be a zero tolerance accident regime, recruitment of a professional project manager, more rigorous due diligence covering ethical standards and commercial practices, enhanced security standards or independent third party audits of suppliers and sub-contractors. Suppliers and contractors themselves are now often required to abide by a business's code of conduct and core standards as part of their contractual relationship so they do not bring it into disrepute.

Risk responses should be designed to bridge gaps between reality and perception, between experience and expectations. They may therefore also include improving communications to certain stakeholder groups or helping to shape stakeholder expectations so they are more closely aligned with what the business can realistically deliver.

However good a business's risk management systems, there will always be an unforeseen crisis or risk that cannot be mitigated. Having an “off the shelf” generic crisis plan, which is proven, well rehearsed and can be quickly adapted and invoked to suit specific circumstances is an essential contingency measure to minimize reputational damage. The nature of the risk event needs to be carefully considered when mounting a response; a huge damage limitation exercise in the case of a self-inflicted wound such as loss of data due to poor internal security will be ineffective.

3.1.9 Monitoring and Reporting

Once risks to reputation have been identified and responses designed and implemented, the risk should be regularly monitored by management to ensure they are having the desired effect. The trick with risks to reputation is to build in early warning indicators that will provide advance warning of an impending crisis while there is still time to take corrective action. Systematic review of complaint trends may point to a product performance weakness, which can be dealt with long before disgruntled customers resort to litigation. Data on safety near misses, if collected and analysed with the right mindset, may provide vital insights into an impending fatal accident.

In so many reputational disasters the early signs were missed, sidelined or ignored. If spotted early enough and dealt with promptly by involving relevant specialist personnel (legal department, safety advisers or public relations) at an early stage, a crisis can be averted or even turned to reputational advantage.

Risk information needs to reach the right people (both internally and externally) at the right time if it is to have the desired effect. Timely and accurate reporting of reputational risks is an important, and often neglected, aspect of the reputation risk management process.

3.1.10 Roles and Responsibilities

Who should be the custodian of a business's reputation? Ultimately the CEO supported by the board of directors, but everyone working for an organization bears some responsibility for safeguarding and enhancing the business's reputation. This includes suppliers, contractors and other partners. All need to be made aware of the value of the business's reputation – and of the risks facing it – so each can play their part as reputational ambassadors.

The CEO and Board should set an appropriate tone through a corporate vision, values and clearly articulated risk appetite, which inform decision making and prescribe behaviors throughout the business and its supply chain. If awareness of reputational and other risks can be raised sufficiently the warning signs are more likely to be spotted and corrective action taken before a crisis strikes.

External non-executive and independent directors can play a particularly crucial role by using their broad experience to constructively challenge the business's risk profile. Have the right risks been identified? Have key stakeholders been consulted? Is anything missing? Has reputational impact been correctly assessed or is the business deluding itself?

Management's role is to continuously scan their area of operation for threats and opportunities that could impact business reputation; record and assess them; design, put in place and operate appropriate responses; monitor their effectiveness and hence the changing status of risks; and report to senior management and the board.

Risk management personnel can ensure that the risk management system is functioning well and that the data within it is updated regularly so timely and accurate reports can be generated to inform decision making.

An internal audit function can assist by providing independent assurance to the Board and management on the effectiveness of the risk management system and on whether individual key risks are being managed appropriately within the risk appetite set by the Board.

Public relations and communication staff can also play a critical role by monitoring and evaluating stakeholder perceptions and expectations to inform the risk management process, particularly in the evaluation of reputational impact and design of appropriate responses to mitigate threats and leverage opportunities. PR can help to design stakeholder engagement processes that not only help the business to keep in tune with the changing stakeholder mood, but also provide the opportunity to shape stakeholder opinion and minimize any perception/expectation gaps. The PR department should be involved sufficiently early in the process to make a difference; summoning PR at the eleventh hour when a crisis is about to erupt is not good risk management!

As suppliers and logistics personnel are often in the front line interacting daily with customers and communities, they too, if properly harnessed can become effective ambassadors for the business by working to enhance its reputation.

3.1.11 Overcoming the Barriers to Effective Reputation Risk Management

So why, when risk to reputation is rated the number one risk to business today, do so many organizations struggle to manage it effectively? A full 62% of companies in the Economist Intelligence Unit Risk of Risks11 survey maintain that reputational risk is harder to manage than other types of risk.

There are several reasons for this:

- Low awareness of the true value of reputation as a key intangible asset and driver of business success and the need to safeguard and enhance it.

- Lack of awareness of potential sources of reputational risks so they can be identified and managed actively.

- Lack of clarity on ownership and consequently regarding reputational risk as a category of risk in itself, which is the preserve of the PR department. Defining reputational risk as anything that could impact reputation, either positively or negatively, can help to ensure that risks affecting reputation are mainstreamed, actioned at source and attract attention at the right level.

- Underestimating the impact of risks to reputation by focusing exclusively on short-term financial impact. Thinking that if you can't quantify the impact precisely it's not worth managing. A guesstimate of reputational impact, involving the right people and based on sound management judgment can make a big difference.

- Having a defensive, downside focus on threats; neglecting the positive upsides of reputational risk and failing to capture and exploit opportunities to boost reputation.

3.1.12 Building Resilience Through Sustainable Reputation: The Way Forward

“You can't build a reputation on what you're going to do” (Henry Ford)

Reputations are ever shifting and potentially transient; they need to be painstakingly built and carefully nurtured. Businesses must be constantly vigilant, not only thinking about reputation when things go wrong, but actively managing risks to reputation all the time. Reputation risk management is both an “inside out” and an “outside in” challenge.

The starting point is setting out your stall “inside out” by defining a clear vision and values, backed up by policies and procedures which will guide behaviors and inform decision making throughout the business and its supply chain. This will also enable your stakeholders to know what you stand for, what your goals are and how you plan to achieve it so they know what to expect.

The second part of the challenge is “outside in”: keeping in close touch with major stakeholders and systematically tracking their evolving perceptions and expectations so gaps are minimized, emerging trends are spotted early and opportunities to offer new products and services in new ways in new markets are exploited.

Stakeholder expectations of businesses and their reputations have never been so high; being authentic, being “the real thing” has never been so important. The concept is far from new, but the way it's handled by businesses is quite new. The corporate responsibility (CR) and sustainable development (SD) agendas have clearly modified the traditional economic role of firms and added aims to their strategies. Nowadays businesses must integrate all their stakeholders, not only shareholders. In this way, they try to create competitive advantage and improve their reputation by the addition of an ethics element. Reputation must always be adapted to the context if it is to be resilient and sustainable. It is all the more crucial that perceived reputation is taken into account, for perception is reality in the minds of stakeholders. It is not enough to be sure of one's actions but the organization must also monitor carefully the image perceived by its stakeholders, even if it is subjective. This bias may be the source of many dissonances between the value put into reputation and the perceived value, which is the only “real” value at the end of the day.

3.1.13 Reputational Risk Management – A Vital Element of an ERM Program

The International experts gathered in Davos in January 2009 for the World Economic Forum seem to have developed a new concept: “The Financial Crisis has demonstrated that risk management is not enough; it is imperative now to develop risk governance.” And John Drzik, the CEO of Oliver Wyman even adds: “For Risk Management to be efficient it must be approached in a strategic prospective, not a mere compliance exercise.” The need for such a stance clearly shows the damages caused by the rush to compliance, be it called Sarbanes-Oxley, COSO 2 or by any other name. Any time brainstorming is replaced by box ticking there is a minefield ahead!

These high profile individuals, among whom many serve in several boards worldwide, and may even sit in risk and audit committees, have even produced the solution: “Risk governance is about asking the right questions to the right persons so that it can be assured that the risks taken are within the boundaries of the organization's risk appetite.” Sounds familiar? The Davos delegates had to take the measure of the economic turmoil of the world to reinvent in 2009 the global and integrated management of risks that the professionals have developed for over a decade and ERM; no doubt they will need many more years to reinvent business intelligence systems to provide the “reasonable assurance” that the information received, transformed and released to all parties is of the highest quality. As a matter of fact “risk management” did not make it in Davos in 2010 or 2011, but the risk review for 2012 and 2013 risks to reputation is to be high on boards' agendas.

It is very important development as it is likely that non-executive board members will feel the need to gain the competencies to do a good job at monitoring risk management activities in their organizations all the more with the transposition of the European directive11 4, 7 and 8 in national laws, as was done in France in 2008; the responsibility for managing risks really rests on the board and the executives. At their level the issue is long-term sustainable growth and the key asset is reputation.

To be successful and sustainable, i.e., to achieve a sound level of resilience, any business needs to enjoy the trust and confidence of all its stakeholders and that can be achieved only when its actions are in harmony with its words. In practice, that requires integrating into the overall strategy the key elements of trust building: corporate governance, risk management, corporate social responsibility and reputation management.

Although stakeholder trust is important for all industries, it is vital for financial institutions, food industry, water supply, pharmaceutical, hospitals, to name but a few at a time when there is:

- Public anger: backcloth of public spending cuts, rising unemployment, food safety compromised, etc.

- Criticism of government policy and sanction voting in several developed countries.

- Increased government, regulators, scrutiny.

- Creation of independent commissions to supervise industries in the public eye.

- Threat of increased regulation/structural form (financial sector, food and drug, etc.).

- The exploding influence of social media.

- Growing investors/rating agency interest in sound risk management (ERM).

- Mandatory disclosure of “principal risks and uncertainties” in listed company annual reports, and regulator wielding of reputational sanctions.

Through their own analysis of the context in which their organization operates or pressured by new legislations, like the 8th directive on governance in the European Union, practitioners, directors and officers have become aware of the need for a global corporate risk management strategy. However, there seems to be a mushrooming of new “silos” in risk management such as sustainable development risk management, procurement risk management, marketing risk management, etc. In view of the social demand and the development of the CSR (corporate social responsibility) an integrated approach to risk management is not an option but a necessity. Trust can be gained, preserved, and enhanced only through transparency and ethical behavior. This is why, in any organization, and even more for publicly traded companies, reputation risk management has become the cornerstone to the desired integration, provided executives and board members are aware that a reputation must be built both “inside out” and “outside in.”

Furthermore, a corporate reputation serves as a reservoir of goodwill to draw upon when challenges and difficulties arise. More than ever in this time of crisis, triggered by a justified drop of confidence in the financial sector, executives must strive to build an authentic business:

“A defining feature of an authentic business is that its profound and positive purpose shines through every aspect of what it does, whether paying invoices (claims), parting with a member of staff, or presenting at a conference” (Crofts, 2005).

Ethical conduct is the core ingredient of trust, hence of reputation. As several situations illustrated individual lapses are always possible but they may uncover systemic risks. Such situations can be drawn from events that took place from the beginning of the century:

- In 2001, the ENRON debacle brought the demise of Arthur Anderson, shaking the entire audit community resulting in the Sarbanes-Oxley12 legislation in the USA.

- In 2007/2009, the financial crisis generating an economic crisis put the banking system on the spotlight.

- In 2011 several drug scandals shook the pharmaceutical industry.

- In 2013, when the mad cow disease had become history, a scandal on the horse meat mixed in all-beef prepared food evidenced that even top brands products were produced in the same factories as store brands and that may prove to have a long-term effect on “top brand reputations”.

As the financial industry has experienced since the summer of 2007, and more recently the food and pharmaceutical industries, individual lapses are always possible, but they may uncover systemic risks. Therefore, we must stress how important it is for any organization to prepare for a disaster, should it strike. In a recently published book on corporate integrity the authors stress that:

“As we found with Hurricane Katrina, being unprepared can cause a disaster that is far greater than the damage caused by the underlying event. The ethical disaster risks facing organizations today are significant and the reputational damage caused can be far greater for those companies that find themselves unprepared for an Ethical Misconduct Disaster. Although we can't predict an ethical disaster, we can and must prepare for one.”13

However, as important as ethics are, we have seen there are many drivers to reputation and many stakeholders whose confidence has to be nurtured and simple common sense would not allow to make sound decisions in such a complex network of intertwined relationships. This is the reason why a model to pilot efficient reputation was needed. Left to their own devices, decision makers would typically “tend to avoid the problem [of interacting criteria] by constructing independent (or supposed to be so) criteria”.14 The same expert points out that:

“the distinguishing feature of a fuzzy integral is that it is able to represent a certain kind of interactions between criteria, ranging from redundancy (negative interaction) to synergy (positive interaction).”

The model for managing risk to reputation is based on nine drivers described earlier. The model is complemented by a kit which can:

- Provide an objective assessment of the nine drivers and an evaluation for the global reputation index, synthesis without loss of information (in this case, it even provides additional insight), and produce analysis tools resulting in an efficient handle on the drivers identified as having the optimal impact on the global reputation index, hence optimizing resilience for a given budget of resources allocated.

- Produce analysis tools resulting in an efficient handle on the drivers identified as having the optimal impact on the global reputation index, hence optimizing resilience for a given budget of resources allocated.

Furthermore the process of data collection is greatly enhanced by using a semantic engine best designed to capture even low noises in the evolution of stakeholders' perception hence all aspects of the reputation, even beyond the e-reputation. It is worth stressing that each driver need be assessed only once before any aggregation, i.e. at level 3 in the model.

This model will equip the board of directors, or governing body, with the tool box that will allow them to best utilize their talent for the benefit of the organization as the optimal solution provided will rely heavily on their own competencies and insight. However, this will require an ongoing effort on the part of the organization. The reputation index at a given point in time provides less information than its evolution through time and this is precisely why it provides a tool to monitor reputation investments at the strategic decision level. Therefore there is no doubt that this index monitoring process will represent an ongoing cost if the optimal return on the initial investment is sought.

Some may question the complexity of the model and it is true that it relies on “expert opinions” but initially only for each branch and in some cases for each organization. However, individual board members need not grasp the complex relationship between the different drivers as it is the model itself that will generate them. This is precisely why it provides additional information through the aggregation processes, contrary to what would happen with a weighted arithmetic mean that would destroy information. Thus, the expertise of the board will be enhanced by the model rather than replaced by its use.

The final word we borrow from Madeleine Albright, former Secretary of State of the US, while addressing the subject of risks of war, terrorism and deadly pandemics and reflecting on her work during the Clinton administration. At a Marsh breakfast during the RIMS convention in Honolulu on April 25, 2006, she gave this essential piece of advice to risk management and business leaders regarding crisis, which are in the end the times of trial for reputation:

“Decisions are only as good as the information you have …Although the crisis for which you prepare may never happen, one will happen …Being prepared for a crisis is never a waste of time.”

References and Further Reading

Crofts, N. (2005) How To Create and Run Your Perfect Business. Oxford: Capstone Publishing.

Douglas, M. and Wildavsky, A. (1982) Risk and culture: an essay on the selection of technical and environmental dangers. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fischhoff, B., Gonzalez, R. M., Small, D. A., and Lerner, J. S. (2003) Judged terror risk and proximity to the World Trade Center. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 26(2–3), pp. 137–151.

Gaultier-Gaillard, S. and Louisot, J.-P. (2006) Risks to reputation: A global approach, The Geneva Papers, The International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics.

3.2 DISTURBANCE MANAGEMENT

Jean-Paul Louisot

Formerly Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Directeur pédagogique du CARM Institute, Paris, France

There are many definitions of risk management because organizations deal differently with how they cope with uncertainty, enhance opportunities and curb threats. However, the core mission of risk management is to ensure the organization's long-term resilience. Therefore, knowing how to manage situations that differ substantially for the expected, exceptional situations is a key competency for a risk management professional. Too often, the whole toolbox is summarized in one term: crisis management.

However, not all disturbances that may touch an organization are of such amplitude that they could trigger a crisis. Therefore any organization must develop a taxonomy of the situations it may be confronted with that may require prior thinking and/or preparation to be handled with optimal efficiency. These situations may present the organization with a threat to curb, or an opportunity to enhance.

The basic concept used here is derived from an article published in the Harvard Business Review.15 In this article the authors outline a framework for decision making in complex systems they call Cynefin. The Cynefin framework is a scale of disturbance levels from low to high: simple or nominal; complicated; complex, chaos. The Cynefin framework can be extended to disturbance management in the context of ERM.

Level 1 – Simple or Nominal State

This is the state for which the system has been developed and set up and based on “best practices” for optimal efficiency. It is characterized by stable and clearly identified causal relationships, slow evolution, order and accomplishment. The main pitfall would be to become complacent if nothing happens.

Level 2 – Complicated State

This is the state, within the confidence interval, where expertise and good practices prevail where multiple answers are possible and several solutions must be analyzed. It is the time when non-conventional wisdom may prove essential. The main pitfall would be to delay decision making until the best is identified.

Level 3 – Complex State

This is the state where new and innovative solutions may have to be tested. Feedback from the experience will provide the learning curve necessary to understand causal relationships. The key is to be ready to embrace creativity and innovation and adopt new management models. The pitfall would be to attempt a straight return to prior situation without analyzing the new context.

Level 4 – Chaos State

This is the state where ruptures may evolve into crisis, while offering real opportunities if top management proves able to make swift decisions. The situations are evolving quickly and it is impossible to discern stable causal relationships; no manageable schemes are identifiable. It is the time for transparent and genuine communication, but based on schemata developed with stakeholders prior to the event, as there is no time to engage at this stage. The time may prove ideal to implement a new business model as deep uncertainty facilitates change management. The main pitfall would be to charge ahead without prior restoration of some order by returning the system to a level three.

As mentioned above the level of disturbance identified will dictate the optimal course of action for management. The adequate reaction from the local or top management will depend on the level identified and can be described as follows:

Level 1 – Simple or Nominal State

This state represents the equilibrium of the system but it is basically an unstable equilibrium around which the system oscillates constantly.

Level 2 – Complicated State

This is a state that any organization may experience regularly that remains within the expected interval. This is why it is important that operational managers, field managers, be responsible for managing daily variations by implementing “good practices” rather than the nominal best practices. This supposes that managers are granted the authority to make the necessary changes and have the expertise to understand what to do in any given situation.

Level 3 – Complex State

This is a state where managing the “accidental” system oscillations, or disturbances, is beyond the daily routine of field managers. Ensuring continuity is the key mission of the operational managers but it requires the preparation and rehearsal of a business continuity plan.

Level 4 – Chaos State

When the required level of “continuity” cannot be achieved at the operational level, it falls on top management to act because the rupture may threaten to develop into a full-blown crisis. The directors' responsibility is to maintain the organization's RESILIENCE through strategic redeployment planning.

In the case of scenarios or exposures that might generate disturbances at level three or four, the preparation of the business units consists of the following steps:

- Elaborate the scheme that will insure continuous operations for all the departments, whatever may happen to current facilities (business continuity planning). Develop alternative strategies where necessary that may preserve the essential of the organization's strategic goals and objectives when continuity cannot be preserved (“survival planning”).

- Identify the critical resources vital to the daily operations of departments, define concrete prevention measures to preserve them, evaluate costs (investment, maintenance and operational) and implement. The critical resources are those that condition the survival of the organization.

- Search for temporary relocation or alternate sourcing for all critical processes, departments, and/or facilities and define procedures to monitor evolution (regular updating) and evaluate costs involved.

- Define temporary equipment and communication devices required in case of an emergency, where to get them and the costs associated.

These solutions must be approved by top management, developed in a crisis manual provided to all managers involved in the implementation, but also explained and rehearsed with all involved in their implementation should the need arise. Detail is essential as to practical measures to be implemented; communication channels with the crisis management team must be clearly identified and open at all times.

During the course of this process, risk control measures vital for the continuity of operations will be elaborated at the same time that the exposures are identified, analyzed, and evaluated. The final risk control program will have to take into account the cost/benefit analysis to be approved by the finance department.

This process may seem to depart from the traditional risk management process as defined in most textbooks. However, it is totally in line with the ERM concept that calls for a portfolio approach at the operational level where all risk owners must provide simultaneous answers to two fundamental questions for the risk management professional:

- What risk am I exposed to? This is answered by developing a risk assessment and a risk matrix to rank the exposures.

- How can I secure the objectives? This is the object of the disturbance management (business continuity planning).

But risk professionals and the crisis management team must always keep in mind that the CEO is the ultimate risk manager of any organization, especially in the case of level four disturbances and disturbances with level four potential. This is the reason why the risk management professional must be positioned as an internal consultant to the executive committee. In such a set-up, the CRO (chief risk officer) is but the “threat shadow” of the “opportunity” chief executive officer: the ultimate risk owner who can make sure all risks are turned into opportunities wherever possible within the risk appetite defined by the board.

Both continuity and survival planning must be coherent plans including prevention measures, temporary alternatives, sub-contracting and purchasing, redundancies and robust and available sources of funds that will enable the organization to survive and reach its goals under most circumstances. This new framework takes into account the level of disturbance; and crisis management is the ultimate tool when the situation is verging on chaos to ensure resilience and continued sustainable growth.

To summarize, the complicated state requires the organization to provide enough leeway to operational managers to navigate daily variations, whereas “emergency situations” (complex states) call for the implementation of business continuity planning. In a rupture situation (chaos state) the event(s) may develop into full bloom crisis and call for strategic redeployment planning.

3.2.1 Business Continuity Planning

The guidelines provided here are sufficient to develop an “in house version” of business continuity planning (BCP) catering to the specific needs of the organization. Depending on the level of disruption, starting up production is the key mission, but a host of questions remain to be answered, e.g., Where? How? When?

There are international and national standards to help organizations develop proper BCP operations, some of which are certifiable, like the ISO 22301 for which several vendors are available. Many organizations have appointed “continuity officers” within their RM department.

The traditional BCP process is split into two phases with the first one aimed at stabilizing the situation, and the second at restarting the operations as soon as possible, if needed, on a temporary basis. The two stages are:

- Emergency stage.

- Restart stage.

The following provides information of how to develop the two stages.

Stage 1 “Emergency”

As soon as the event is threatening, or striking, emergency measures must be activated. These emergency measures aim at:

Protecting people:

- Call and guide public emergency services (firefighters, etc.).

- Verify all safety equipment.

- Warning to neighbors (if necessary).

Protecting reputation:

- Crisis communication with all parties involved:

- Public authorities.

- The general public.

- Economic partners (customers, suppliers and sub-contractors).

- Stockholders (and financial analysts).

- Media.

Protecting physical assets:

- Guard the site.

- Organize salvage operations.

Stage 2 “Restart Production”

Production must resume but how it resumes will depend upon the marketing plan. There remain some important points to cover:

Site: Are there other facilities available?

- Plant and equipment? (the same, identical, new technology?)

- Machinery (performances, delivery time).

- Equipment (replacement, rebuild).

Supply chain:

- Origin.

- Quality.

- Costs.

Logistic:

- Transportation and routes.

- Packaging and shipment of production.

It is essential to evaluate the maximum downtime acceptable for any “vital resource” as the cost of restoration likely will be high with a goal of short downtime. In many cases approaching “start-up” as a project may prove to be efficient especially with a PERT (Project Evaluation and Review Technique).

Business Continuity Planning is developed and implemented by the operational managers and risk owners but should follow the process and objectives provided by the risk management office, and be audited regularly. However, local situations and context must be taken into account to develop BCP for each of the local “killer” scenarios, i.e. the situation that could result in an unacceptable downtime from the overall organization's perspective.

3.2.2 Strategic Redeployment Planning (SRP)

Strategic Redeployment Planning is a process that must be conducted by top management, C-suite and/or board when the situation leads to a rupture – chaotic state. The key to success in the SRP implementation phase is to equip the leaders with the competencies to make decisions under stress and duress.

The leaders must concentrate their attention on:

The evaluation of the situation of the organization

- Can persons and assets be secured?

- Can production continuity be insured?

- Is our reputation at stake?

- The organization resilience (based on the available information) i.e. could the organization survival be in jeopardy in the medium or long run although it might limp along in the short term?

Can the existing “business model” survive?

- Should a “new” business model be developed and implemented?

- Investigate all the options open to the company.

- Place sentries and scouts to capture “low noises” as the risk owners on the field may be able to see early signs that the context is changing, and gathered at the headquarters level, they may provide crucial information dictating to revise the strategy before any generalized disturbance appears.

- Create a team spirit to survive even the worst tempest.

When the situation reaches the “chaos” disturbance level, returning to a pre-event status is generally not feasible. Therefore, top management will be called upon to define a new course of action based on the information gathered in the proper receptacle. An organization experiencing a chaos disturbance will add two phases to the BCP: strategic review and communication.

Phase 1 “Strategic Review”

Evaluate impact on reputation and/or market share of temporary withdrawal for the market?

- Customer loyalty?

- Suppliers and sub-contractors loyalty?

- Window of opportunity for old or new competitors?

New Marketing Strategy (needed or not needed?)

NOT NEEDED:

- The organization to stick to its traditional products and markets.

- Set priorities (managing limited output).

What lines of business, products (or services)?

What customer segments?

- For low priority products, evaluate:

- When there is temporary halt of production: conditions for re-entry on the market.

- When halt of production is final: commercial impact (synergies?)

- Financial impact.

- Compensation for loss of revenues (new products, new clients, new countries?)

NEEDED:

- The organization redeploys its resources to cater to new markets and customer needs.

- (Evaluate competencies and develop a new strategy).

- How, substitution?

- Commercial action.

- How to restore profit growth?

- (Evaluate competencies and develop a new strategy).

Phase 2 “Communication”

Beyond crisis communication, which is a part of the emergency procedures in Phase 1, maintaining or restoring the long-term reputation is a necessity that requires attention beyond the crisis itself:

- Maintain permanent link with “news media”.

- Keep in touch with local authorities and professional associations.

- Keep all employees and sales force updated on progress and development.

- Treat all suppliers and sub-contractors as partners in good and bad times alike.

- Use all means possible to build and consolidate customers loyalty (including speedy delivery of orders even in difficult times).

- Keep stockholders informed.

This will require special efforts in the case of a strategic redeployment decided in Phase 2.

3.2.3 Specific Elements Common to BCP and SRP

Two elements are common to the two levels of planning: crisis communication and emergency fund.

Crisis Communication

The preceding remarks on crisis development clearly point to the fact that in post-event redeployment planning, the impact on the environments with which the organization interacts is a determining factor in pulling through the crisis. It is essential to differentiate between planned post-event survival and crisis management. According to French specialists, the term “crisis” should be used only in a situation where all the organization's processes and milestones are destroyed, leaving an empty field where no forward planning provides answer to the exceptional circumstances encountered.

In situations like those involving Union Carbide in Bhopal and Perrier (when the bottles were allegedly contaminated with pollution and had to be recalled in the USA, depriving the company permanently of its exclusivity in the top market for sparkling waters), the entire organization is put in jeopardy. Reputation or brand name can be permanently compromised. Therefore, under such circumstances, nothing short of a company-wide mobilization with the help of economic partners is necessary to preserve and even boost reputation.

In any situation where reputation is at stake, it must be remembered that reputation ultimately rests in the continuing trust and confidence of the stakeholders. Therefore, some rules must be adhered to in communication with all: credibility and transparency (speak the truth) are the key to success:

- Credibility, like trust, takes a long time to earn and a short time to lose. However, crisis communication success is based on long established trust relationships with the news media, involving years of hard work.

- Transparency can only result from a long learning process by top executives so that they can feel at ease with (sometimes tough) questioning journalists. Executives appointed to communicate with the media must know how to give quick direct answers to direct questions. Not everyone has the competencies and talent to confront the media. Specifically, the CEO may not be the right person. Who will be in charge of communication with the media and other stakeholders must be determined before any crisis.

An important reminder: time is of the essence in any crisis situation. The chain of events that cause and develop with the crisis is always rooted in the quick pace of alterations of some key factors. Time is particularly important in the degradation of the information: a delay in media confrontation may pave the way to rumors that may continue spreading, especially through social media, even after they have been dispelled with data and better information, especially with the impact of social media. The media carry an “emotional way” to get public attention. And also remember that bad news sells more than good news for commercial media.

But any amount of advance planning is never enough. Prepared and informed executives will have to improvise as the crisis develops; but sound improvisation is the result of much advance preparation and executives must be well trained in making decisions under uncertainty and stress. Sound risk control measures explained ahead of time to employees, economic partners and news media would build credibility, a “good citizen”, “sound management” image that will be rewarded in time of a crisis. Also, through a “crisis scenario” drill the members of the “crisis management team” will be trained in reacting positively and to be efficient leaders under stress.

However, the CEO may view such activities as costly and fail to see the value creation. The “next door syndrome” is also common: dire events happen only to the “others” because they did not have proper R&D, proper marketing, proper quality management or proper safety and environment management. The risk manager must develop enough understanding of the decision makers' psychology to assess how they will take to crisis preparation activities and have a sound plan on how to respond to negative reactions.

And it is true, nobody wants to live through a crisis and it may well be in many cases an investment without an obvious return. It may require the auditors to come up with a method to measure the added resilience gained by the organization in order to evaluate a return on investment. However, the requirement for corporate governance may, and compliances may prove to be, the best way to justify efforts and resources deployed to develop sound crisis management.

It is not always easy to define what would be the best attitude towards crisis management. Bertrand Robert and Daniel Verpeaux (FRANCOM group) in an unpublished manuscript titled “Crisis Communication”, define several attitudes using different “caricatures” that may reflect different organizational cultures:

- The wellness doctor: a global approach is aimed at patient health without waiting for any symptom of illnesses. In time of a crisis, there is no time to build confidence in dealings with the public and the media; it is the time to harvest the fruit of patient prior efforts.

- The lawyer: a essential quality is to listen and understand the victims' point of view in order to build an efficient defense strategy in line with the legal environment.

- The preacher: a faith strong enough to remove the mountains of taboos and superstition, and facilitate team sharing and efforts.

- The marine officer: is on the battlefield with his/her troops and takes part in all the combat drilling.

- The gardener: knows that plants need time to grow (“leave time to time”, the late French president, François Mitterrand, was fond of saying). He/she cultivates his/her media network to build a strong image in the time of peace to capitalize on when the time of duress comes.

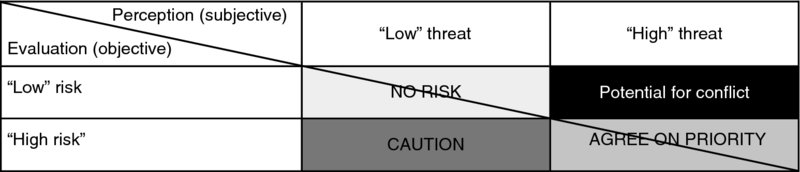

In a matter of reputation, image, or loyalty, one must remember that proper and timely communication is essential. However, the subjective reality (emotions, feelings) is often more important than the objective reality (hard facts). This is the reason why the perception of hazards by the community in which an entity is established is a crucial element of any communication strategy about hazards and perils. The extent to which hazards and perils are perceived and evaluated in a crisis can be summed up in Figure 3.6.

Figure 3.6 Perception and evaluation of hazards and perils.

That means that the risk assessment must address these questions of risk perception as well. The exposures cannot be viewed in a closed system (the entity) but must do so from the point of view of and in context with the organization's stakeholders (including economic partners, stakeholders, and the society at large).

Therefore, the risk manager professional must be able to develop a matrix similar to Figure 3.6 for any “sensitive issues”, that are significant for the public, pressure groups or the elected officials. Understanding stakeholders' perception and sensitivity is a necessary step in the development of an effective preventive communication strategy with the proper priority (message content, target groups, media, etc.).

One of the key ingredients to any good communication is a feedback loop. A crisis is not a time when “authority” can dictate a “truth” that will be automatically accepted by a passive public. The public wants to be an active partner and feedback channels must be established to allow the authority to reconsider their position to reflect public expectations. At all times, security measures must take this into account and diffuse public anxiety, remembering that the level of anxiety reflects the perceived risk and not scientific evidence to measure risk “objectively”.

Risk control measures that the stakeholders do not adhere to may prove inefficient, even if these measures are recommended by scientific experts or are in compliance with legal and regulatory requirements. The public must adhere to the project that the organization is promoting, adopt the entity and live in osmosis with it: the public is the main partner and it is for the public to decide if an appropriate level of safety is reached.

It is the level at which the public trust and confidence is preserved that will ensure the organization's resilience. This opens the new field of business ethics where one must always ask the question “should I do this” rather than the more mundane question of the past “could I do it”, i.e. what I do may be “legal” but if it is perceived as unethical by the stakeholders, the organization's reputation will be at stake.

Emergency Funds

Post-event redeployment planning, like any industrial or commercial project, must translate into budget and cash flows forecasts. The cash flow elements are crucial because in difficult time new sources of funds are not easily acquired unless they have been secured ahead of time. The aftermath of a large incident may last from 6 to 24 months or longer; therefore sources and uses of funds forecast should be established on a monthly basis for up to two years (or more) following a “crisis”. The net deficit is precisely the amount of funds, month by month, that has to be secured through these new sources of funds from lenders, insurers, and others. But this is precisely the core mission of risk financing.

3.2.4 Summary

While preparing for a crisis is key to any organization's long-term survival, not all disturbances are at a level that would require implementing a crisis plan. Reacting appropriately to match the disturbance level is essential so that operational managers and risk owners have the responsibility to manage the risks within their area of command. They must also have the authority to implement temporary measures to respond to daily deviations from the optimal situation, and develop a business continuity plan in order to navigate through complex situations and limit the consequences for the organization and its main partners.

The presentation on level of disturbance can be used to “coach” risk owners in how to engage and apply appropriate risk management techniques and BCP processes. More than “compliance issues”, they constitute a toolkit that helps them cope with situations and optimize their performance in cases outside of their comfort zone (complex state).

However, there are chaotic situations that require top management attention and sound preparation to make appropriate and effective decisions under stress with only limited information. The framework developed as a strategic exercise before any event is called the strategic redeployment plan and it should be designed to prepare for alternate courses to protect the goals and objectives, or mission of the organization to the extent possible in the new context created by the event.

In all situations, responding to the public's perceived risks through open and straightforward two-way communication is essential. Building trust and confidence with media, and social media, will prove essential in times of tumult and upheaval.

Two situations may illustrate this fact. When Perrier was confronted with traces of benzene in their “perfect” water, a swift reaction to recall all bottles in the channels of distribution was a costly proposal; however Perrier needed to regain market share of high-end mineral waters. Swift reaction helped Perrier regain a sizeable share of the market because public confidence was restored.

By the same token, companies that have failed to answer the public have suffered, if only temporarily. Two recent examples are relevant: British Petroleum after the Gulf of Mexico explosion; and Toyota after repeated brake failures. In the long run, however, both changed their strategic response and were able to build on their otherwise strong image and rebound both in the public opinion and in the stock exchange.

However, there is a word of caution about disturbance management from Paul Coehlo in a forthcoming work where he summarizes the key to resilience for any organization: “Discipline is important but it needs to leave open doors and windows to intuition and the unexpected.”16