11

Case Study: Three Steps for Bringing Risk Management Back in House

Interviewee: Renee Reimer J.D., Chief Risk & Legal Operations Officer, Memorial Hermann Health System

Interviewer: Christopher Ketcham, Ph.D., CPCU, CRM, CIC, CFP®, Formerly Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Houston Downtown, Houston, Texas; Garnet Valley, Pennsylvania

Date: November 30, 2012

11.1 MEMORIAL HERMANN

Memorial Hermann (MH) is a 107-year-old not-for-profit healthcare system in the greater Houston Texas community. The area served by MH today has a population base of 6.14 million, which is expected to grow to 6.71 million by 2016. MH is one of the largest not-for-profit healthcare system in the state of Texas and has a 23.5% market share [Note: using 2011 data] in the Expanded Greater Houston Metropolitan Service Area (MSA1) for inpatient services through 12 hospitals. MH also has other service operations in 171 locations. The MH package of services includes: inpatient hospital delivery services, outpatient ambulatory services, home health, drug rehabilitation and alcohol treatment, and retail services including diagnostic, laboratory, sports medicine, rehabilitation, and imaging. MH's trauma center is one of the nation's busiest. In addition MH operates one of the only air ambulance services in the region and has its own health insurance company providing health benefits for its employees and others.

The Federal government in the US requires hospitals to measure and report patient safety and other clinical indicators to show not only that hospitals comply with various standards, and regulations but also to provide consumers and others with comparative quality clinical outcomes data to make informed choices about medical care. Having excellent performance indicators is becoming critical to hospital accreditation and reputation. These measures of quality and patient safety are public information and are used by various governmental agencies and healthcare quality improvement organizations. MH has been recognized as a national leader in quality and patient safety. MH was awarded the 2012 Eisenberg Patient Safety Award by the National Quality Forum (NQF) and the Joint Commission. The award recognized MH as a national leader in delivering safe, effective healthcare with a patient-centered focus. Thompson Reuters recognized MH as one of America's top 5 Large Health Systems and also among the top 15 health systems in the nation in quality in 2012. The Delta Group recognized MH as America's number one quality hospital for overall care for the last two consecutive years. Seven years in a row MH has been cited as being one of healthcare's “100 Most Wired”. MH is also classified as a distinguished healthcare system because of its clinical excellence. Four MH hospitals are listed among America's 50 Best Hospitals by HealthGrades®, ranking among the top 1 percent in the nation. Six MH hospitals are listed among America's 100 Top Hospitals® by Thompson Reuters.

Memorial Hermann is the result of a 1997 merger of two not-for-profit health systems in the Houston area. At the time of the merger each of the two systems had a risk management department. However, leadership at that time decided that it was prudent to outsource risk management to a third party administrator. This was the case until 2009 when Renee Reimer was hired as the chief risk officer, responsible for risk management and insurance services for the organization. Her boss, the chief legal officer, asked Reimer to study whether continuing to outsource risk management in whole or in part was still a good idea. This case is a summary of the process taken by Reimer and her team when it was determined that risk management should be brought back in house.

11.2 THE DECISION TO BRING RISK MANAGEMENT BACK IN HOUSE

MH's risk management function had been outsourced to a single TPA (third party administrator) firm for approximately ten years. The TPA managed the claims function and provided loss control and other services. There were TPA employees on site acting as a corporate risk management department for the health system and interfacing with a risk liaison in each hospital. Shortly before Reimer joined MH, the general counsel, known within MH as the chief legal officer, who had been with MH for almost three years when Reimer joined the organization, commissioned an independent assessment of the risk management function as he was uncertain whether the TPA model was an effective risk management structure for MH. When asked to study whether the existing model was the best way for MH to manage risk, Reimer not only reviewed the findings of that independent study from the outside firm but also did her own assessment. An attorney in the state of Texas, Reimer has almost 30 years of legal experience, with approximately half of those years spent specifically in healthcare.

The studies suggested that the circumstances that led to the initial outsourcing decision no longer existed. Second, MH had grown considerably in size and complexity to warrant both a high level of direct accountability by a senior leader and their own team, and a strategic approach to the management and mitigation of risks. A third critical factor that these studies uncovered was that the outsourcing model, while effective in handling claims, was less effective in proactive data mining and trend analysis that could be used to create actionable risk and quality initiatives to prevent or mitigate risk events in the future.

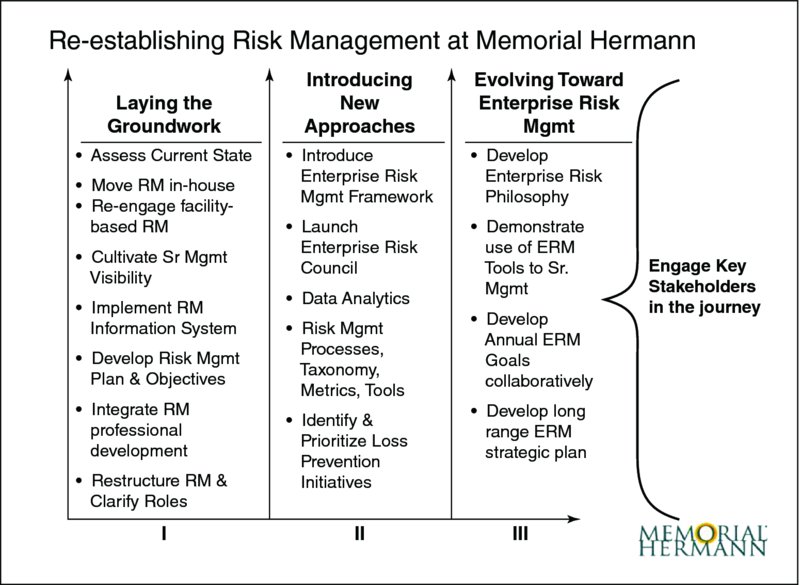

Reimer and MH began a three-step approach to re-establish a risk management function in the organization and create a strategic approach to management of risks. Step one was laying the groundwork or a design–build phase to create the foundation for a high functioning internal risk management department including adding the necessary business intelligence data structure. Step two was the introduction into the organization of an enterprise risk management (ERM) framework and the establishment of an enterprise risk council at the highest level of the organization. Step three, which was launched in 2011 and continues today, is focused on the maturation of the ERM approach to risk identification and management at a strategic level as well as the expansion of and integration of ERM principles throughout the organization. Work in 2013 will consider how to improve the quantification of the impact of various risks to MH in order to move beyond a financial impact “score” and to a narrative description methodology for better articulation of the potential impact of key organizational risks. Figure 11.1 outlines the three-step approach Memorial Hermann has used to reestablish the risk management function and engage ERM.

Figure 11.1 Re-establishing the Risk Management at Memorial Hermann. Reproduced by permission. Copyright © 2013 Memorial Hermann. All rights reserved.

11.3 STEP ONE – LAYING THE GROUNDWORK: RE-ESTABLISH RISK MANAGEMENT

Risk management had not disappeared from MH. Each hospital had talented and experienced registered nurse clinical risk liaisons focused primarily on working on the day-to-day patient safety clinical risk issues for their individual hospital. There was the centralized risk control function of the TPA and claims were being competently managed and resolved when turned over to the TPA, yet there was minimal interaction between the individual hospital-based risk liaisons or alignment of risk management initiatives across the health system. There was insufficient appreciation of the value of bringing the risk management staff together for professional development or collaborative work. Risk management had low visibility amongst senior leaders in the organization. The insurance services and risk transfer program, while managed competently by on-site TPA staff for many years, had also grown more complex requiring the expertise of more skilled and experienced insurance services professionals.

When the relationship with the TPA was terminated Reimer was still a new employee at MH. She turned to the vision, brand promise and cultural values espoused by the organization for guidance in how to proceed in re-establishing the risk management function within the organization to create the necessary alignment. MH had an aspirational vision to be “best of the best.” MH values the whole over the individual parts of the system to advance health and deliver the best possible health solutions. Enterprise-wide thinking is a key consideration for any organization that wants to embark upon an enterprise risk strategy. If an organization continues to maintain independent risk silos then it will be difficult to build an approach that can be engaged throughout the organization.

Reimer saw that the key strategies of the company known as “Big Dots” would be a good place to begin the alignment of risk. This was also helpful because when she introduced ERM to the organization, what had been developed to date in the risk management function was consistent with what would be necessary to the development of a strong ERM program.

MH's “Big Dots” align with its current vision and brand promise as shown in Figure 11.2. Vision – be the pre-eminent health system in the US by advancing the health of those we serve through our physicians, employees and other partners to deliver best health solutions while we relentlessly pursue quality and value. Brand Promise – We advance health. Overall the structure of strategy is organized around three dimensions:

- Care delivery.

- Health solutions.

- Physician integration.

The Big Dots are distributed into six categories:

- Quality and Safety.

- Patients.

- Operational Excellence.

- Growth.

- People.

- Physicians.

Figure 11.2 Brand compass outlining Memorial Hermann's vision, brand promise, and culture. Copyright © 2013 Memorial Hermann. All rights reserved.

Some of the individual Big Dots include:

- High reliability patient care.

- Advancing inpatient quality and safety – the physician dimension.

- Employee safety culture – safe work environment.

- Patient, physician, employee and member satisfaction.

- Expand number of covered lives (members) in insurance program.

- Medicare improvement – reduction in Medicare opportunity days.

- In-network utilization – keeping customers within the MH system.

- Market share growth – care delivery.

- Medical Home expansion – expanding the primary care medical home network.

As with any good strategic plan, the Big Dots are reassessed each year but must align with the overall strategic plan.

When the risk management function was re-established it was determined that it would report up through the general counsel via the chief risk officer. Reimer is in charge of both the day-to-day operations of the system's legal department under the direction of the chief legal officer as well as responsible for the risk management department. There are fourteen people in RM in the corporate office responsible for five key functional areas: (1) claims and litigation management; (2) loss control and prevention; (3) risk data analytics; (4) insurance services and risk transfer; (5) emergency management; and (6) system policy and procedure governance. Thirteen risk managers are located “in the field” covering individual hospitals and the outpatient ambulatory care facilities and services. Further, three additional people devote a portion of their time as risk liaisons to be an additional set of “eyes and ears” or “boots on the ground” in the outpatient care areas. Field risk managers are RNs but unlike traditional hospital risk management departments their scope of responsibility is not just clinical but includes ERM.

Risk Management departments in many organizations have traditionally reported through finance. Reimer believes that for MH, risk management is more effective reporting through legal because so many of the issues associated with risk management at MH have a legal or regulatory dimension. From the beginning of the re-establishment of the risk management department it was determined that the chief risk officer (CRO) should be an attorney. In addition to the CRO, the RM department has three attorneys, including an RN-JD, and a paralegal. The senior leaders at MH are called chiefs. Reimer is also a chief and sits on the president's council. As a result, risk management is visible at the highest levels of the organization. Being involved at the highest level of the organization has helped to facilitate the re-establishment of the risk management program and made it possible for an ERM program to be implemented.

In addition to owning a health insurance company providing health benefits for its employees and external member customers, MH owns a Cayman incorporated captive insurance company through which it self-insures its healthcare professional liability (malpractice coverage), general liability, auto liability and employee injuries.

But that is today. When Reimer reestablished the risk management department her first objective was to obtain data for better decision making, clarify roles, fill leadership gaps, and implement key processes to ensure that the risk management function was operating effectively with regard to the basics of risk management (risk identification, loss control, claims analysis, and insurance/risk transfer). Reimer began by meeting with senior leaders from across the healthcare system to apprise the leaders of her assessment of the current state of RM, to provide them with a vision for the future, and to engage them in supporting the alignment of the field risk managers with the new re-established corporate RM function. In transitioning away from the TPA model, a new claims management information system was needed as well as replacement of an internally developed and designed risk identification variance system. The claims management and variance reporting systems now in place not only enable claims capture and payment but also produces relevant data reports for risk analysis and proactive risk mitigation initiatives.

MH had not utilized loss control in any structured way and its insurance needs were more complex so Reimer began a process of shoring up loss control and insurance services by bringing in new professionals to the organization. Reimer brought in data analysts to begin the process of analyzing incidents and claims for causes, outcomes, and prevention and mitigation opportunities. Field risk managers were brought together on a monthly basis with the corporate office risk management team for professional development, common risk issues discussion, and for alignment of risk objectives. The risk manager role was expanded beyond clinical risk management to encompass an ERM approach and new job descriptions developed. Reserve guidelines and risk management plans were also developed and documented and Reimer brought in more attorneys and RNs into the function.

Reimer established a Claims Authority Group (CAG). The CAG includes, the chief financial officer, chief risk officer, chief legal officer, and chief medical officer. CAG meets on an ad hoc basis to discuss only claims reserved above one million dollars. One of Reimer's attorneys is tasked with presenting an assessment of the case in a confidential written pre-trial or pre-mediation summary. During the review process, the attorney asks the CAG to make a decision on the claim and either authorize a settlement amount or direct that the case proceed to trial. The benefits of using a CAG are two-fold. First, the decision is made by a senior team of leaders who are most likely to appreciate the potential broader implications of the claim beyond its financial impact. Second, these large claims make senior leaders aware of the cumulative impact of risks to the organization and have served to raise the visibility of the risk management function and alert the organization to important risk mitigation opportunities.

Reimer reasons that leaders most often make decisions based on data and numbers. Therefore risk management began to show claims data to a broader audience of executives and tasked the in-house risk management attorneys to review all cases resolved in the concluding year and prepare and present a report for senior leadership at each of the business segments. The report included what the claim was about, the reserve, what was paid, and what was learned. The CEOs and senior leadership in the divisions had not seen this data before, but quickly learned how the information could be used to better manage risks in their areas of accountability. She explained how risk managers review and triage over seventeen thousand variance reports annually although very few ultimately result in claims or suits.

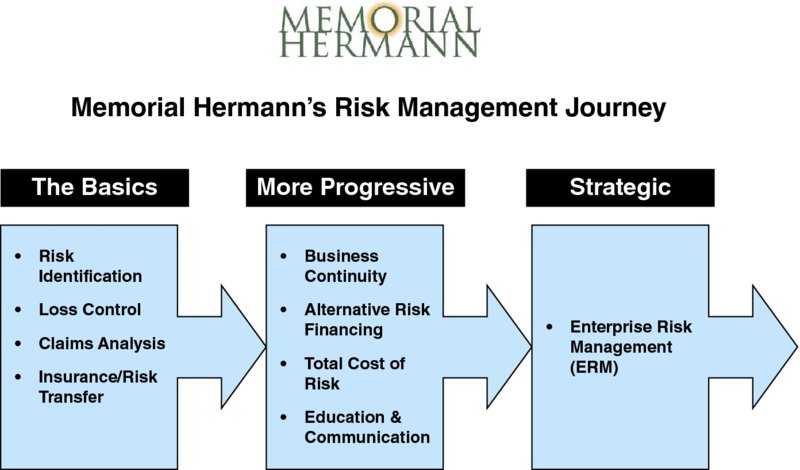

However, just having the basics of the risk management function operating effectively was not enough. Gathering and presenting data was not enough. Developing good risk management practices in the field was not enough. Reimer reasoned that there were risks that a traditional risk management department was not likely to be able to address at the operational level. She determined that an ERM approach at the highest strategic level was an important next step. Figure 11.3 demonstrates the risk management journey at Memorial Hermann and the three risk management approaches that are now in place.

Figure 11.3 Risk Management Journey. Copyright © 2013 Memorial Hermann. All rights reserved.

11.4 SECOND STEP – INTRODUCING NEW APPROACHES: THE ERM COUNCIL

Even before establishing the ERM Council, Reimer began to introduce the concept of ERM to senior executives. MH did not have a forum to look across the organization to assess interrelated risks and potential impact on the organization or how multiple risks could correlate. She determined that an advisory group of executives should serve together as a coordinating body to look at diverse risks to the organization from whatever source. The advisory group is called the ERM Council and was chartered to look more expansively and from a strategic point of view at risks in order to understand the interrelatedness and cumulative impact on the organization. The council, formed in 2010, consists of executives who have a broad depth of knowledge and expertise in their own areas of accountability but also know the MH strategic objectives. They have the knowledge, authority and influence to be able to assess risks at a strategic level, prioritize the importance of a risk on the organization and assess the potential impact of such risks. Second, they have the ability to bring resources to strategic risk issues and focus the organization on key critical risks. The council includes the System's:

- Chief Medical Officer.

- Chief Financial Officer.

- Chief Legal Officer.

- Chief Operations Officer.

- Chief Information Officer.

- Strategic Planning Officer.

- Marketing & Communications Officer.

- Chief of Facilities.

- Chief Risk Officer.

- Community Benefits Officer.

- Internal Audit and Compliance Officer.

- CEO of the owned insurance company.

- 2 physician organization chiefs (physician network/ACO and employed physicians).

- 3 CEOs of the largest hospitals in the system.

- Chief Human Resources officer.

This council represents individuals who have the greatest influence and understanding of MH. The council meets three to four times each year.

The first meeting in 2010 was an introduction to the concept of ERM. Before the meeting Reimer sent seminal articles on enterprise risk management to the council to read. During that meeting Reimer also introduced members to the basic goals of risk management and the concept of risk as uncertainty. She explained that this council had a broad perspective of the organizational strategies and would have a unique understanding of the major business areas of the company. As a group they could look at risks from a big picture view. Combining their experience, data, and intuition, they would be the team to assess the critical risks to strategy that affect the organization over time. They would develop in a formalized manner, using an ERM framework, an integrated picture of risks and they would then serve as the champions of helping MH develop a unified approach for risk action planning.

The ERM Council considers ERM as both a decision making process and analytic framework. The council is tasked with considering business risks from an enterprise portfolio perspective. They use simple tools like an online survey tool to identify potential risks, facilitated group sessions to prioritize and rank risks, heat maps to identify the priorities, and facilitated small group meetings to fully articulate the identified risks, risk triggers, consequences, and current controls in place.

The committee's charter was clear: their focus was strategic. They needed to develop at the strategic level a common language and methodology for the identification and management of strategic business risks based on their collective perspectives of the risk tolerance of the organization in the context of the strategic objectives. They considered risks within a three-year horizon in order to concentrate their view and limit their attention on critical business risks that will affect the organization in the calculable future. In essence the committee is tasked with assessing: What are the risks to our organization achieving its strategic goals over the next three years?

11.5 THE THIRD STEP – EVOLVING TOWARDS ENTERPRISE RISK MANAGEMENT: NARRATIVE RISK DESCRIPTION

Part of the third step in MH's process to reinstitute the risk management program is the development of a narrative approach for expressing the potential impact of certain risks, which cannot be adequately or accurately reflected by a numeric or quantitative method. As this is a step that has just been embarked upon there are no results. However, the concept of a narrative approach to risk management may not be familiar to many risk managers.

Traditionally risk management has used a quantitative approach to defining risks, probability or likelihood and impact severity in terms of financial costs. Narrative knowledge has found its way into law, medicine and other professions and it deserves consideration in risk management. The narrative approach to medicine uses narrative to explain complex events (Charon, 2001a, 2001b, 2005, 2007). Medical events not only include the physical malady but also the person, their circumstances, and their environment. The need for narrative is no different in risk management. Events or incidents often require that the issues be put into context or have complex origins, which may have antecedents that may have contributed to the event or incident. Nor are all assets of an organization easily quantified. Reputation is a good example of a risk that is often viewed as an intangible and therefore difficult to quantify and best expressed through narrative reporting when numerical expression can be unreliable. For hospitals the narrative in risk management could be constructed similarly to that of medicine. First is active listening. The second is putting into writing what happened, beyond the basics of the incident. What was the environment at the time; were there emotional issues that surrounded the event or incident; and what happened in the days, weeks, or moments that led to the event? The third is sharing the narrative with those affected by it whether it is an individual or an entire organization.

Nor is the narrative just for ex post facto analysis of events. Narrative can be used to describe critical risks that the organization faces. This is important for multiple reasons. First, the narrative can more fully explain the problem and how it might produce loss. Second, many people are more attuned and responsive to stories because they help individuals to visualize the concept. Third, narratives more fully describe the circumstances of the organization and may lead management to understand risk more holistically in association with attitudes, aptitudes, and environment that may produce or exacerbate losses.

The narrative in risk management has received limited attention in the literature but is something that should be more fully researched and considered.

11.6 TANGIBLE RESULTS AT MH

The council initially identified sixty potential risks in operations, financial, reputation, hazard, environmental, legal, and regulatory areas. These 60 risks were prioritized by impact on the organization. As a result of the impact assessment the list was distilled down to 12 critical risks. After a facilitated process of fully articulating the critical risks, the council assigned a champion for each of the 12 risks and asked the champions and their teams to provide the council with a more in-depth view of each risk, current controls or risk mitigation efforts, and to develop an action plan designed to minimize the risk impact or likelihood.

One of the top strategic risks identified by the council was the significant and increasing uninsured population and the resulting impact on the healthcare system. Texas leads the nation in uninsured residents and only 53% of Texas employers provide health insurance for their employees. In the Houston area alone, more than 31% of the population does not have health insurance and 72% of the uninsured are employed by small employers who do not offer healthcare coverage, or whose coverage options are unaffordable. Many of the uninsured tend not to get healthcare on a routine basis to manage chronic conditions and more than half of all patients entering emergency centers are seeking care that could be provided in a community based clinic, overcrowding emergency facilities and delaying care for the truly critically ill. MH is a primary healthcare safety net in the Houston area communities for the uninsured but as their numbers increase, the safety net is stretched to its breaking point.

The assigned champion for the uninsured patient project developed a five-prong action plan. One of those initiatives was to expand an emergency center navigator pilot program in a hospital campus emergency center to help uninsured patients begin the process of obtaining a medical home for care of their future non-critical but chronic or acute illnesses more affordably and conveniently. The healthcare navigator connects them with lower-cost community healthcare providers who can provide a medical home for future healthcare concerns. The navigator follows up with each patient to ensure that they have used the referral and are satisfied with the care they received. As a part of this action plan, three hospitals created a primary care center next to each of their emergency centers to care for patients with non-critical care needs that could be appropriately treated in this care setting. One of the hospitals found in the first few months that 34 percent of patients presenting to their emergency center could be appropriately cared for in the primary care facility; and it was 43 percent at a second hospital. The three participating hospitals have experienced a combined 79 percent reduction in non-critical emergency room visits since the program began. This is a win–win for both the patient and the hospital. The patient receives appropriate high quality care and the hospital has a lower uninsured cost burden for non-critical care provided in the hospital emergency center.

Traditional operational risk management would not have considered the strategic business risk to the organization of the growing uninsured population nor would it have the authority or likely even the capability to propose options to mitigate this significant risk. While the uninsured initiatives cannot make the problem go away it is making the costs to the organization less significant. What is also important is that the ERM council is made up of key individuals who (1) understand the strategic direction of the enterprise, (2) represent most major segments in the enterprise, and (3) have significant decision-making and budgetary authority to make changes happen. They meet regularly not only to continually reassess the critical risks that face the medical system but also to report on progress in each of the initiatives that is associated with critical risk. Reimer periodically informs the system's board as well as the team of risk managers and others of the identified strategic critical risks and the projects in play to mitigate and manage the risks. As a result the council's work is distributed throughout the organization. The work of the ERM Council also highlights how an organization can accomplish risk mitigation without engaging in silo thinking. The uninsured problem solutions required the engagement of many different departments and disciplines both at the local and organizational level. The side-by-side emergency room–primary care concept required a reorganization of hospital services, new ways of screening, regulatory consideration, and reallocation of physician and nursing staff. Without silo thinking the organization was able to develop new procedures and programs in a very short period of time because affected parties worked together to put the enterprise first and turf second.

11.7 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR OTHER RISK MANAGERS

Reimer suggested that there is no cookie-cutter approach to risk management even to similar organizations in the same industry. Every enterprise is different in what it does, its approach to the business, and its culture. Therefore each risk management program will be unique.

Second, Reimer was new to the organization when she was asked to rebuild the risk management function. She could not learn the intricacies of MH in the short period of time she had on the job. Instead, she has had to engage people who know the organization well and her role has become to facilitate and to engage the organization's leadership to take ownership of the enterprise's strategic risks. She has worked to bring alignment to the work of the nurse risk managers so that collectively the risk management team looks beyond just clinical risk issues and considers a broader enterprise risk management approach to their work.

Reimer explained that the risk management group in any organization has to shine some light on what risk managers do, provide data to leaders, and engage leadership in a dialogue regarding strategic risks. When management is engaged on risk issues the organization's view towards risk management will change.

11.8 QUESTIONS FOR STUDENTS AND PRACTITIONERS

- How could a narrative approach be used to better identify and assess risks that are not easily quantified?

- MH identified one of its greatest risks as the cost of the growing uninsured population. In keeping with its mission of quality care it realigned its services to make these less costly. What other non-traditional strategic risks do you think that the ERM Council could have identified?

- Outsourcing of services has its place in risk management. However, it may not be the total solution. What would be the circumstances under which an organization could consider to outsource some of its risk management function? What would be the controls and assurances that an organization should put in place to make sure that what has been outsourced meets the continuing needs of the organization and is consistent with its strategy, vision, and brand promise?

NOTES

REFERENCES

- Charon, R. (2001a). Narrative medicine. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(15), p. 1897.

- Charon, R. (2001b). Narrative medicine: form, function, and ethics. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134(1), p. 83.

- Charon, R. (2005). Narrative medicine: Attention, representation, affiliation. Narrative, 13(3), pp. 261–270.

- Charon, R. (2007). What to do with stories: the sciences of narrative medicine. Canadian Family Physician, 53(8), p. 1265.