3

Hacking Habits

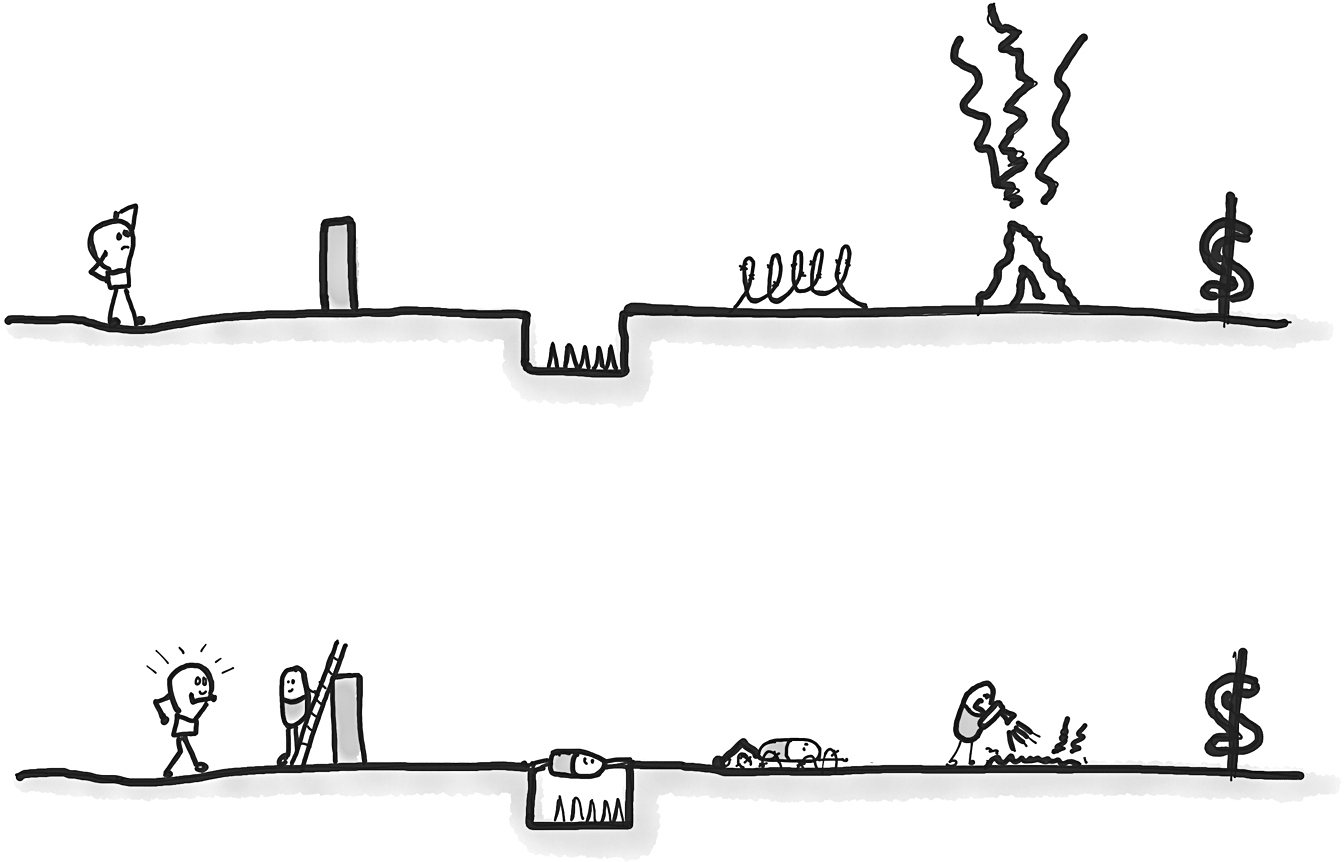

Destin Sandlin had a simple question: How hard would it be to unlearn to ride a bike? So, the host of Smarter Every Day, a popular educational series on YouTube, asked a welder he knew to do something kind of strange: to change Sandlin’s bike so that when he turned his handlebars right, the bike would go to the left, and vice versa. Sandlin was an engineer who understood the mechanics of bike riding and an avid rider who was well trained to handle a bike. How hard could it be?

Very hard, it turns out. “The challenge is much more complex than it might seem,” a summary by the Arbinger Institute noted. “Several intricate processes—balance, coordination, steering, pedaling, and more—come together in the action of riding a bicycle. Our brains must precisely direct and coordinate each of these complex processes, meaning that learning how to ride a backwards bicycle requires a complete rewiring of the neural pathways associated with bike riding.”

Use BEANs to bust the status quo.

Sandlin’s first ride went nowhere. It took him eight months of practicing five minutes a day before he could successfully ride the backwards bike. Then, of course, when he got back on a normal bike, he again went nowhere. Fortunately, it took only about twenty minutes for Sandlin to re-remember how to ride the normal bike.1

Now changing habits in an organizational context is quite different than in Sandlin’s experiment. Riding a bike is deeply imprinted in muscle memory, requiring hard conscious work to unpack and unlearn. Few, if any, people spent their childhood running spreadsheet analyses, trusting market research over firsthand customer experience, or demanding answers when they should be asking questions. Still, the point remains: changing habits is hard. The shadow strategy descends and makes a well-intentioned organization functionally immovable. To learn how to encourage innovation behaviors, you have to hack habits with BEANs (behavior enablers, artifacts, and nudges). This chapter will detail key lessons from habit-change literature and share examples of some of our favorite BEANs. The companion case study that follows will then show the effectiveness of the conscious creation of BEANs at a DBS development center in Hyderabad.

Lessons from Habit-Change Literature

The previous DBS case study detailed a program called MOJO, created to improve meetings and encourage collaboration.2 Why does MOJO work? It rips a page out of the habit-change literature. Over the past few decades, psychologists have pinpointed why it is so hard to change habits and have provided a range of practical tools to facilitate habit change. Their way of thinking about change has now crossed over into mainstream culture via influential books such as Switch by Chip and Dan Health, Nudge by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg, and Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman.

Similarly, our journey to the BEAN concept started by devouring the literature and studying historical habit-change programs. For example, one of the world’s most successful habit-change programs, Alcoholics Anonymous, highlights themes that appear in the literature. Founded in 1935 by Bill Wilson and Dr. Robert Smith, over the past eighty-five years, the program has helped millions of people battle addictions to alcohol. The core of the program is simple, supported by mantras such as “one day at a time.” The AA program recognizes how hard habit change is, so it attacks the problem on multiple fronts. Every member has a sponsor with whom they interact regularly, and members are encouraged to shape their living contexts to remove temptation: avoid meeting friends at bars, remove the booze from your house, and so on. The heart of the AA program is communal—at meetings, members work together to help each other—and is supported by physical artifacts such as tokens, which they earn when they achieve certain milestones.

Another successful program that follows a similar pattern is Weight Watchers, which in 2018 rebranded itself WW as part of a move from weight management to wellness management. Founded in 1963 in Queens, New York, by Jean Nidetch, WW is the most widely used weight management program in the world today, with more than 4 million active members. The points system at the core of the program simplifies the sometimes-complicated challenge of calorie counting and portion control. But more critical is the powerful social shaping that occurs during its meetings. Points and specific menu items help, but the meetings serve as the social glue that holds the program together.

These two programs—AA and WW—provide solid examples of how to modify an existing habit, while gaming companies show how to create new ones. It starts by following Atari founder Nolan Bushnell’s maxim that games should be “easy to learn and difficult to master.” That makes it easy for people to start and hard for them to stop playing a game, turning it into a habit. Games also typically have communal elements, where you can compete head-to-head or compare your score and progress to others. A variety of rewards motivate you to keep progressing. And, of course, there are sights and sounds that engage you with the game. When these factors come together, they result in amazingly addictive (and profitable) games such as Super Mario, Candy Crush, Pokémon Go, Angry Birds, and Fortnite. If it sometimes seems like the world is turning into a huge video game, it is because research shows that badges, rewards, and charts showing progress actually work.

Three themes connect these examples. First, habit change requires engaging both people’s rational, logical side and their emotional, intuitive side. Second, habit change requires a multifront battle. Consider how AA and WW use a combination of mantras, nudges, and social interactions to change people’s patterns. Third, the science of motivation shows how goal-setting, achievement, and social comparison and encouragement reinforce desired behaviors.

The enemy of innovation inside most organizations is institutionalized inertia that is reinforced in systems and norms. The antidote to inertia is to break old habits and form new ones. While most habit-change literature has focused on individual behaviors, such as stopping smoking, eating better, getting more regular exercise, and learning new skills, we posited that the principles of successful habit formation and change would be just as applicable to organizations.

As such, a few years ago a team at Innosight started to collect examples of interventions that promoted better innovation habits inside organizations. In the end, we collected more than one hundred examples, which we found in client organizations, in case studies from the Innovation Leader information service, and in corporate cultural documents compiled by Tettra, a Boston-area startup.

We picked the acronym BEAN because, like MOJO, the most successful programs combine the following:

- Behavior enablers: Direct ways to encourage and enable behavior change

- Artifacts: Physical or digital objects to reinforce behavior change

- Nudges: Indirect ways to encourage and enable behavior change

In the book Switch, Chip and Dan Heath borrow a Buddhist metaphor to describe the process of behavior change. They talk about a rider on an elephant going down a path. While the rider, representing the rational mind, might want to move in a new direction, the elephant, representing the emotional mind, continues to thoughtlessly trundle down the existing path. How, then, do you drive change?

Behavior enablers are direct ways to help the rider learn how to influence the elephant. A behavior enabler details the new script you want to follow and provides tangible, direct support to follow that script. To borrow language from Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, a behavior enabler engages “System 2,” the slow, deliberate part of decision-making, which constitutes about 2 percent of our thinking. More specifically, behavior enablers might involve the following:

- Developing a routine or ritual, such as the “check in” that the MO follows in each meeting

- Having access to a coach or counselor, like AA’s sponsor

- Building a wider community, such as those in the AA and WW meetings, to help directly reinforce the new behavior

- Creating simple checklists or user guides, like AA’s twelve-step program or WW’s points system

Nudges are indirect ways to support behavior change. In the elephant metaphor, a nudge changes the path itself, so the elephant moves in a new direction without consciously thinking about it. In Kahneman’s language, nudges engage “System 1”—our fast, unconscious, automatic thinking system. In an organizational context, that might involve things like:

- Using what is known as “choice architecture” by making the desired behavior the “default choice” (such as in the famous example where the percentage of people who choose to be organ donors is almost completely explained by whether it is the default choice when applying for a driver’s license)

- Having reminders (such as the notifications that wearable gadgets provide when you sit for too long)

- Creating and sharing stories (like the ones told at AA meetings)

- Using physical office design to facilitate specific behavior (similar to how AA suggests removing temptations from the house)

- Publishing “leaderboards” or providing other forms of comparison (a staple of any catchy game)

Finally, artifacts are the physical and digital reinforcers that connect the first two ideas. They are the signposts that help the rider remember what he or she needs to do. Example artifacts include:

- Prizes and trophies that recognize the new behavior (like the coins AA members earn to recognize a certain number of days of sobriety)

- Physical avatars that reinforce desired changes (such as the wizard Gandalf at DBS, which connects to DBS’s aspiration to positively compare itself to Google, Amazon.com, Netflix, Apple, LinkedIn, and Facebook)

- Tokens (like the wizard hat and staff that DBS sometimes has at meetings to reinforce the Gandalf metaphor)

- Pictures and visuals that serve as background reminders

- Physical objects that sit on desks or in conference rooms

BEANs at Innosight

As the language and the toolkit around BEANs began to emerge, Natalie, Scott, and Andy realized that Innosight had built two BEANs to support important change efforts.3

At the end of each year, Innosight has one-on-one discussions to get feedback from clients. A few years ago, as the leadership team reviewed the verbatims from client interviews, a surprising insight emerged. Innosight leaders had always assumed that the reason they won head-to-head battles against bigger consulting companies rested in its unique intellectual property or thought leadership. Yes, clients said, that wasn’t unimportant, but everyone had some kind of intellectual property. What made Innosight different, clients said, was Innosight itself. There was just something different in how Innosight teams showed up and worked with clients. “They are a thought partner, invested in our success, fun to work with and humble but confident. Innosight genuinely wants to be driving impact,” one client said. “They are a delightful group to work with. They have a great culture,” another noted. This led to the leadership team’s dusting off and refining a set of underlying values that had been formed early in Innosight’s history but largely forgotten.

How does an organization encourage people to recurrently live the behaviors behind values like humility, transparency, collaboration, and inclusivity? The Innosight Different BEAN attacked this problem on multiple fronts. An anchor of the BEAN is an award given out by Innosight’s managing partner every December. Behavior enablers include sharing detailed descriptions of the values and desired behaviors and the annual routine of seeking award nominations via a simple SurveyMonkey survey. Select stories are shared at Innosight’s year-end gathering, posted on Innosight’s internal website, and fed to year-end reviewers to be captured and memorialized during the annual review process. There are many artifacts, including most notably:

- A physical award (which Andy won in 2014 and Natalie won in 2015!)

- A set of custom-created cartoons that now hang in Innosight’s headquarters in Lexington, Massachusetts, and are included in pitch documents

- A video on Innosight’s intranet that shows the values in action

- Rotating digital screens in the Innosight headquarters lobby, which greet visitors with values cartoons and Innosight impact stories

- Small desktop flip-books with additional cartoons that illustrate what it looks like when Innosight doesn’t live up to its values4

Innosight provides further nudges for leaders to live up to Innosight Different by regularly running employee surveys that include questions about the degree to which leaders model the values.

The First Friday BEAN reinforces a conscious effort to improve connectivity and collaboration across Innosight. In normal times, Innosight’s consultants spend a significant amount of time on the road, working side by side with its clients.5 While this helps Innosight deliver against a core value of impact, it can inhibit community connectivity. First Friday is a ritual in which a significant portion of Innosight’s North American and European employees gather in sessions nine times per year, with each session recorded and posted to the intranet for time-zone-challenged colleagues in Asia. One key nudge to encourage collaboration at these sessions is to have assigned seating to support the formation of new relationships. Interestingly, one of the surprising benefits Natalie and Scott noticed about the virtualization of life in the first half of 2020 is attendance to First Friday went up; there was no longer a divide between people in the room and people out of the room, and virtual breakout rooms made it easy to spur discussion.

Innosight has experimented with other ways to encourage collaboration, as well, which could someday turn into more fully formulated BEANs. For example, to create more connections, Innosight invites people participating in a training event or workshop to share their favorite song and artist before the session. Then a snippet of each person’s song is played before and after breaks, with the group guessing whose song it is. Once the person is revealed, he or she shares what it is that makes the song special to him or her. It is a fun to way to accelerate the process of people getting to know each other, and at the end of the program you have a playlist.6

What Makes a Successful BEAN

What makes a BEAN work? Studying the literature and looking at BEANs that work suggest six key ingredients.7

SIMPLICITY: Make it easy to adopt and remember.

Want to exercise more? Leave your running shoes by your bed before you go to sleep. Want a patient to remember to take medication? Ensure it is in a blister pack with the days of week on it. We’re willing to bet you’ll remember MOJO months after reading this book! Habit change is hard, so make it as simple as possible to start, which does mean spending time thinking of a memorable name for your BEAN.

PRACTICALITY: Connect it to existing routines.

The fewer things you have to change, the better. One of the biggest benefits of electric toothbrushes, for example, is a timer that turns the toothbrush off after the two minutes that dentists recommend. Behavior change with no thinking required! In the case of DBS, MOJO didn’t require a completely new routine; it docked into an existing one—meetings already exist. They start and they (sometimes after what seems like forever) end.

REINFORCEMENT: Create physical and digital reminders.

As memorable as the name MOJO is, in the early days of any program, it is easy for people to revert to old habits and simply not take the time to appoint a MO, name the JO, check in, and check out. So when you walk into a conference room at DBS, you see visual cues—fun cubes that people can play with on tables and checklists on the wall—that serve as reminders of the MOJO program. These kinds of physical reminders help to nudge people to participate in the program.

ORGANIZATIONAL CONSISTENCY: Ensure it links to objectives, processes, systems, and values.

One of the most cited papers in the change literature is Steven Kerr’s 1975 classic, “On the Folly of Rewarding A, While Hoping for B.”8 Effective BEANs don’t encourage people to do one thing if the company rewards them for something else or punishes them for that behavior.

UNIQUENESS: Create something fun and social and support it with stories and legends.

The name MOJO causes you to pause and say, “Tell me more.” The name is easy to remember. Tying it to meetings ensures it is done in communal settings. Sharing stories (like the JO who provides feedback in verse or the brave JO who provided feedback to the senior leader) helps spread the idea.

TRACKABILITY: Build it in a way that it can be adjusted, measured, and scaled.

While there is a spirit of fun and creativity in MOJO, it is serious business: DBS tracks the effectiveness of meetings and knows that meetings with MOJO have double the effectiveness of those that don’t. These measures allow DBS to track and improve MOJO. In 2018 DBS introduced a smartphone app (an early iteration of which is available in the public app store), both to aid in MOJO’s application and to capture data that allows DBS to further improve the program.

A Few of Our Favorite BEANs

Hacking day-to-day habits with BEANs is a key way to drive a culture of innovation. The text below discusses some of our favorite BEANs, grouped by the five behaviors described in chapter 1 (these BEANs are summarized in table 3-1), and includes prompting questions to help you create your own BEANs to encourage each behavior. Part II of the book details more than 20 additional BEANs, and the appendix has a list of 101 interventions in our “bag of BEANs.” Further information about BEANs is available at www

|

Behavior |

BEAN |

Description |

Behavior enabler |

Artifact |

Nudge |

|||||

|

Curiosity |

DBS’s Gandalf Scholarship |

Employees can receive S$1,000 (US$740) to study any topic of interest, as long as they teach it back to the organization |

A step-by-step application guide |

A companion website with videos of “teach-backs” |

The name itself, which is a nudge toward DBS’s culture-change “avatar” |

|||||

|

Customer obsession |

Amazon.com’s Future Press Release |

The practice of describing ideas via “future press releases” from a customer perspective |

An in-meeting ritual of reviewing press releases versus PowerPoint decks |

Physical memos |

The meeting design |

|||||

|

Collaboration |

Boehringer Ingelheim’s Lunch Roulette |

An easy-to-use website to set up “lunch dates” with new people |

Step-by-step instructions on the website |

Collateral describing the program |

Gamification via the roulette analogy, which encourages participation |

|||||

|

Adeptness in ambiguity |

Tata’s Dare to Try |

An annual prize and public recognition for teams that failed but learned something valuable |

Prize guidelines that provide detailed descriptions of desired behaviors |

A physical trophy |

Supporting materials that spread stories about past winners |

|||||

|

Empowerment |

Adobe’s Kickbox |

A physical box with step-by-step experiment guides and a prepaid $1,000 debit card |

Checklists, tools, and the debit card |

A physical “box” given to participants |

A kit that contains “levels,” to nudge continued participation |

CURIOSITY. Another example of a well-crafted BEAN from DBS is the Gandalf Scholarship. As part of its aspiration to favorably compare with companies like Google and Apple, DBS set a goal of becoming a learning organization that constantly questioned the status quo. Historically, it ran leadership development in a traditional way, pushing in-class learning to identified employees, who were then encouraged to learn things that directly helped them improve their day-to-day work. The Gandalf Scholarship flipped the model on its head. Now, any employee can apply to receive S$1,000 (about US$740) to spend on a project of his or her choice—a course, books, a conference—that supports DBS’s goal of becoming a learning organization. The only condition is that scholarship winners must teach what they’ve discovered to their colleagues. As of fall 2019, the bank granted more than 100 scholarships in areas from artificial intelligence to storytelling for managers, with the average recipient teaching close to an additional 300 people. DBS has recorded many of these “teach-backs” and posted them on an online channel with related articles and other information, creating virtual artifacts that have been viewed more than ten thousand times. The bank estimates that each dollar it spends on the scholarship has a positive impact on thirty times as many employees as a dollar spent on traditional training.

Questions to consider: How can you help make sure your team doesn’t get stuck in a rut? How can you encourage people to discover new things, even those that seem to be disconnected to their day jobs?

CUSTOMER OBSESSION. One of Amazon.com’s stated missions is to be the world’s most customer-centric company. A ritual to reinforce this mission relates to how Amazon managers propose new ideas. At most companies, ideas are detailed in PowerPoint documents replete with facts and figures. The thicker the deck, the better the idea. At Amazon.com, instead of a PowerPoint deck, managers create a Future Press Release that they imagine will accompany the launch of the finished product. The press release doesn’t start with the idea; it works backwards from the customer job to be done. And it must contain frequently asked questions, which again encourages the idea submitter to look at the world through the customer’s eyes. When it comes time to discuss the idea, rather than have the idea presented, meeting attendees silently read the press release before engaging in discussion.

Questions to consider: How can you make sure your team takes a customer-first perspective? What visual cues can you create? Are there regular questions or idea description mechanisms like Amazon.com’s future release that can help?

COLLABORATION. When David Thompson worked in the US arm of pharmaceutical manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim (BI), he created an innovative way to inspire internal collisions that foster collaboration. Thompson’s idea came from a problem all of us have encountered. He entered the corporate cafeteria one day and noticed his usual lunch companions weren’t there—and he didn’t recognize any of the other faces in the room. He envisioned—and then in two days, with help from a friend, prototyped—a simple website where people could find random lunchmates. They called the idea Lunch Roulette. Participants who sign up indicate the dates they are interested in participating and the locations they are willing to travel to. The click of a button then creates a match and an automatic calendar invite. Upon its rollout, hundreds of people immediately signed up, including the CEO. “A lot of times, a CEO only talks with someone who has been prescribed for them. With Lunch Roulette, he doesn’t know who he’ll be paired with and neither does the other person,” Thompson said. “Both can learn something from the other. After all, if we don’t have people who can learn both up and down, then we have the wrong people in both levels.”

Questions to consider: How can you encourage physical or virtual collaboration? Are there ways to make it easier for people to meet and work together?

ADEPTNESS IN AMBIGUITY. Being adept in ambiguity requires being able to handle the inevitable false steps, fumbles, and, yes, failures that come along with innovation. A powerful BEAN that helps to reinforce this tolerance comes from the Tata Group, India’s largest conglomerate. Every year the company holds a celebration honoring innovation accomplishments across its sprawling collection of business units, which range from tea to IT consulting to automobiles. One of the most coveted awards given at that gathering is called Dare to Try. As the name connotes, it goes to a team that failed but in an intelligent way. In the company’s words, “Showcasing a growing culture of risk-taking and perseverance across Tata companies.… [Dare to Try] recognizes and rewards the most novel, daring and seriously attempted ideas that did not achieve the desired results.” Dare to Try is a substantial program, attracting hundreds of applications annually. Promotions for it help nudge innovative behaviors like embracing risk and tolerating failure. The award itself—a trophy—and the highly visible public summary of the event are artifacts that effectively reinforce Tata’s innovation culture.

Questions to consider: How can you condition people for the ambiguity that accompanies innovation? How can you publicly and loudly celebrate learning versus privately and quietly punishing failure?

EMPOWERMENT. One common complaint from would-be innovators is the chain of approvals they need to do anything. While that problem can often be largely perceptual, it also can be a very real innovation inhibitor. The Adobe Kickbox is a purpose-built BEAN to empower employees at the 20,000-person software company. Successful applications receive a red box that’s about the size of an encyclopedia (if you are reading this and are younger than thirty years old, ask your parents).9 Crack open the box and you will see a range of tools designed to facilitate developing prototypes for ideas. Most critically, the box contains a $1,000 prepaid debit card that can be spent without asking for anyone’s approval. In its first few years, Adobe granted 1,000 Kickboxes. That’s $1 million in investment, but it is also 1,000 experiments that otherwise would not have been run. Many of those experiments have gone nowhere, but some have informed new product development or highlighted acquisitions opportunities.

How can you help people progress an idea? Are there process shortcuts that can help to more quickly move ideas from paper to reality?

One Last Note

The case study that follows will detail a simple process to create a BEAN, and the next chapter will provide a front-row seat to one organization’s six-week sprint to create the alpha version of a culture of innovation within their HR community. Before getting there, however, we’d like to make one last point: one mistake we see people make sometimes is confusing BEANs (ways to encourage a new behavior) and innovations (something different that creates value).

In September 2019, Scott and Andy were getting ready to share some of the content from this book at a large gathering of HR professionals in Australia. As stimuli for the discussion, they had the US Innosight team create a two-minute video of Innosight new hires describing challenges and opportunities of the onboarding process. For example, one new hire described the stress of trying to quickly remember everyone’s name. “One of the things that was a challenge is I am one new person coming in, and there are a hundred people that I am going to meet over the course of a matter of weeks,” he said. “This one-hundred-to-one problem is actually really stressful, to try to remember everyone you met. You might run into someone getting a cup of coffee and think to yourself, ‘They seem familiar. I think I have met that person before. But I don’t remember their name.’ So actually, it is quite a lot of stress.”

It’s not hard to imagine a range of innovative ways to address this “one-time” stress. For example, imagine creating a simple app in which a new hire could tick off employees that they have met, helping them keep better track of new faces. Or, to push the imagination a bit, consider an augmented-reality solution that brought up someone’s profile on a whiteboard whenever they entered a room. Those kinds of solutions help to solve a single problem. That’s innovation—something different that creates value. But there’s perhaps a bigger issue at work: what’s behind the new hire’s angst could also be a lack of deep connection in the community. The recurring behavior to encourage, then, could be to get to know people as humans. Boehringer Ingelheim’s Lunch Roulette encourages that behavior. Or consider a suggestion from an Innosight team during an office gathering: Have a table in the café set up as the “Eat with me” table. Ideally this would be a wooden farmhouse table that is larger and more inviting than the normal café tables. It would bear an “Eat with me” sign and possibly include a whiteboard to list topics for discussion. People across the firm would be able to sign up to sit at the table, to ensure there was always someone there for new hires or others who wanted a lunch buddy. There would be reminders of the table in regular company emails, and it could be pointed out on office tours as well. As such, this project has the potential to be a powerful combination of a behavior enabler (the whiteboard with topics and instructions), an artifact (the physical table), and a nudge (reminder emails and tracking).

Innovation solves a problem; BEANs enable innovation.

BEANs and innovations are both valuable things. But they are different things. Be clear when you are seeking to solve a problem versus when you are trying to encourage a behavior.

Chapter Summary

- Fighting against institutionalized inertia requires pulling a page from the habit-change playbook to shape day-to-day behavior. Specifically, hack habits with BEANs: behavior enablers, artifacts, and nudges.

- Behavior enablers are direct, tangible ways to support behavior change, such as recurring rituals, checklists, and dedicated coaches. Nudges are indirect, intangible ways to make behavior change easy, such as office design and leaderboards. Artifacts, such as prizes, pictures, and stories, connect the two by physically and digitally reinforcing the change.

- Successful BEANs are simple, practical, reinforced, organizationally consistent, unique, and trackable.

- Our favorite BEANs include DBS’s Gandalf Scholarship (which encourages curiosity), Amazon.com’s Future Press Release (which reinforces customer-centricity), Boehringer Ingelheim’s Lunch Roulette (which aids collaboration), Tata’s Dare to Try program (which helps it to be adept in ambiguity), and Adobe’s Kickbox (which empowers employees).

- An innovation solves a problem, while a BEAN encourages a behavior.

1. Interestingly, it took his six-year-old son, who had less to unlearn and the higher neuroplasticity that comes with youth, only two weeks to learn how to ride a backwards bike.

2. It was only a couple pages ago, but if you are a nonlinear reader, here is the synopsis: The “MO” in MOJO is the meeting owner who sets the agenda and ensures wide participation. The “JO” is the joyful observer who intervenes if people are distracted and who provides public feedback to the MO. The program has saved hundreds of thousands of labor hours and helped dramatically improve the degree to which DBS employees feel their voices are heard in meetings.

3. One thing we consistently see is that groups will tell us they don’t innovate. We then give our definition of innovation (something different that creates value), and they realize they absolutely do innovate. They just didn’t have the language for it. Similarly, we bet your organization has a BEAN or two that has helped to change or reinforce culture. Let us know if we are right, as we’d love to add more ideas into the bag of BEANs.

4. Scott’s favorite cartoon is of a client buried under PowerPoint slides that have been dumped from a truck. The tagline reads, “Now that’s impact!”

5. And, of course, while this book is being written, Innosight consultants are spending all of their time at home interacting with colleagues and clients through videoconferences.

6. Natalie stole this idea from a healthcare client. She recalls that one client picked a Metallica song that helped her through the last mile of a marathon, another loved Broadway musicals, and yet another loved country music because it reminded her of her family’s ranch in Wyoming. At an offsite in October 2019, Scott picked Pearl Jam’s “Betterman” (specifically the live version played in the August 7, 2016, concert in Fenway Park), and Andy picked “Agadoo” by Black Lace. Okay, he actually didn’t, but this is a test from Scott to see if Andy would read the footnotes during the review process. He did. The song he actually selected was “Whole of the Moon” by The Waterboys.

7. Yes, the text that follows forms the acronym SPROUT. One reviewer felt that they had reached acronym overload at this stage in the manuscript, so we chose to have it as a gift to our dear footnote readers.

8. The notes section in the back of this book has the formal reference for Kerr’s work. The footnote is to acknowledge one of our favorite reviewers, who caught that there was a typo here reporting the paper was published in 1995. “I can report with complete objectivity that 1975 is in fact the very best year to be born in,” the reviewer noted. A previous version of the manuscript described how Scott was born in that year, and that might have accelerated our efforts to figure out who this anonymous reviewer was, except he directly emailed us the thirteen pages of (hugely useful) comments he had on this book. Thanks, Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg!

9. Please note that Adobe employees do have to apply to receive a Kickbox, so there is still a filter. That was a caveat missed by the CEO of a 10,000-person firm that heard Scott describe the program at a company offsite. Inspired by the story, he followed Scott on stage to announce that everyone at the company would receive $1,000 to experiment. The CFO, with whom he had not conferred before making the proclamation, looked on in horror, as the $10 million commitment would blow a hole in the budget. The firm deftly managed to keep the essence of the leader’s intent while putting up enough guardrails that the program’s implementation didn’t unintentionally lead to the need to cost cut!

BEANs are a powerful way to encourage desired behaviors and overcome key blockers. Consider how DBS used BEANs at a purpose-built development center in Hyderabad, India. The new center was taking over previously outsourced operations, such as the design and support of customer-facing mobile applications, and it presented the company with the opportunity to build a more entrepreneurial culture from scratch.

The center’s office design mimicked what you’d see at any hot, young tech venture, with open space, snack bars, and, of course, the obligatory foosball table. Its recruitment processes, borrowed from innovative companies like Netflix, were designed to attract distinctive talent. But when the lights went on, it quickly became clear that employees’ day-to-day experiences had little of that startup feeling. The engineers fell into well-worn routines, working methodically and avoiding fast-paced experimentation. DBS leaders in Singapore continued to treat Hyderabad like an arm’s-length vendor versus a set of colleagues seeking to advance a common mission. While employee engagement scores weren’t terrible, they were notably short of DBS’s aspiration.

To turn things around, a group of Innosight consultants and DBS Technology & Operations change agents (which we’ll call the culture team) decided to develop BEANs that would disrupt the unwanted habits and promote new and better ones. The team followed a four-step process (chapter 4 explores this process in even greater detail).

1. Get Granular about Desired Behaviors

The culture team outlined what kind of organizational traits needed to be encouraged at Hyderabad. DBS had already identified the need to be agile, learning-oriented, customer-obsessed, data-driven, and experimental. The culture team went deeper to list more specific behaviors under each of these categories. For example, under “Experimental,” were aspirational statements such as “We rapidly test new ideas,” “We practice lean experimentation,” and “We fail cheap, we fail fast, and we learn even faster.”

2. Identify Behavioral Blockers

Next the culture team looked for things that were getting in the way of the desired behaviors. To uncover these, members sat in on staff meetings, conducted diagnostic surveys, interviewed center employees confidentially one on one, and reviewed “day in the life” journals that developers kept for a week.

The team was specifically looking for existing habits and behavior patterns that were inhibiting innovation. For example, among other issues, the culture team found that many employees felt that they jumped into work without discussing its context, so they lacked an understanding of how their project fit with the broader strategy, what was expected of each person working on the project, and so on. Some employees also felt that candidly surfacing problems was taboo, so they stewed in silent frustration. Meanwhile, developers reported being stretched so thin that they lacked time to innovate, but deeper exploration revealed the real problem: a lack of clear guidelines for how to prioritize a seemingly never-ending list of requests.

3. Design BEANs

The culture team then designed ways to eliminate the blockers. To get things going, it facilitated two two-day workshops with senior leaders, one in Hyderabad and the other in Singapore. After discussing the desired behaviors and their blockers, participants broke into small groups for structured brainstorming. Each group was given examples of BEANs from other organizations for inspiration, and to devise new ones, they used a simple template to specify the behaviors sought, the habits blocking those behaviors, and the behavior enablers and nudges that would help employees break through the blockers (chapter 4 has a sample capture template). All participants then reassembled to review the fifteen ideas for BEANs and voted on a few to implement.

Here are three interventions that were created to tackle lack of context, candor, and prioritization at the center:

LACK OF CONTEXT. This blocker reinforced employees’ sense that their business-as-usual approach was good enough. The BEAN targeting it was a Culture Canvas inspired by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur’s canvas that maps out the key elements of a business model. The Culture Canvas is, likewise, a simple one-page, poster-size template. On it, project teams articulate their business goals and codify team roles and norms. Filling it out helps them gain a clearer sense of expectations, organizational context, and who does what. Giving teams clarity about their goals and the scope to push boundaries further empowers their entrepreneurial spirit. The resulting physical artifacts, which include photos and signatures from members, serve as a visual reminder of the team members’ commitments.

LACK OF CANDOR. A BEAN called Team Temp was devised to liberate employees to speak up when they saw problems. The web-based app, to be used at the first meeting of the week, gauges a project team’s mood by inviting members to anonymously describe how they’re feeling by entering a score from 1 (highly negative) to 10 (highly positive) and writing a single word that best describes their mood. This quickly reveals if the team has an issue (a string of 1s and 2s is pretty telling) and prompts a discussion—led by the team leader—about what’s going on and how it can be addressed. Because the app tracks team sentiment over time, it also gauges whether interventions are working.

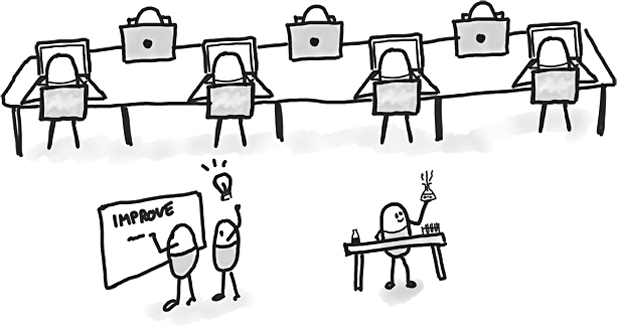

LACK OF PRIORITIZATION. To bust this blocker, the culture team created the 70:20:10 BEAN. Inspired by Google’s practices, it gives software developers explicit permission to spend 70 percent of their time on day-to-day work, 20 percent on work-improvement ideas, and 10 percent on experiments and pet projects. By formally freeing up chunks of time for unspecified experimentation, 70:20:10 encourages innovative thinking. To reinforce it, the cultural team also created a ritual in which developers share what they’ve learned from their experimental projects with one another.

4. Refine and Implement BEANs

Pilot teams in Hyderabad tested a handful of BEANs, including the three detailed above. Their impact was carefully measured and improvements were made along the way. Ineffective BEANs were discarded, and effective ones were rolled out more broadly and tracked. As a result of the 70:20:10 BEAN, for example, teams automated several previously manual processes, shaving hours off of key tasks, and developed other innovations. (The initial version of the MOJO app described in chapter 3 came out of one developer’s experimentation time.) Meanwhile, leaders increased the amount of time they spent walking the halls and modeling the new ways of working.

A year after the interventions began, employee surveys showed that workers’ engagement scores at Hyderabad had increased by 20 percent and that customer-centricity had risen significantly. In 2018 LinkedIn named the development center one of the top twenty-five places to work in India, and in 2019 the bank won a prestigious Zinnov award for being “a great place to innovate.”