4

Conducting a Culture Sprint

Singtel Group is Southeast Asia’s largest telecommunications company. Through fully owned operations in Singapore and Australia and substantial investments in operators in markets such as India (Airtel), Indonesia (Telkomsel), Thailand (AIS), and the Philippines (Globe), it has about 700 million mobile subscribers. Over the past few years it has made substantial investments to build a portfolio of digital businesses in new markets like mobile advertising and cybersecurity. In mid-2018 its group chief human resources officer Aileen Tan framed up a different challenge. “I press a button on my phone, and a car appears. I press a different one and food arrives. I can instantaneously initiate a video call with friends around the world. To the consumer, these innovative services are like magic. And we enable that magic,” she said. “But inside the organization we have papers and forms and processes and structures and rules. Why can’t we be as innovative internally as the market demands externally?”

Remember, it took Destin Sandlin eight months on his own to unlearn how to ride a bike. The DBS story took place over a decade. Was there a way, Tan wondered, to focus and accelerate the culture change journey? She decided to experiment by focusing on the culture of the team closest to her, the Group HR team. Every movement must start somewhere, she posited. What better place to start a culture movement in a large organization than the 150-person-strong Group HR team? After all, this team touches every business unit and employee in the organization.

This chapter borrows the metaphor of a sprint from the agile movement, which originated as an approach to dramatically accelerate software development and has spread as an approach to accelerate a broader set of initiatives. A sprint, performing an integrated set of activities in a tightly defined period of time, follows the agile principles of delivering working software frequently and responding to change over following a plan. At Singtel, that meant developing an alpha version of a culture of innovation within six weeks. The anchor of the sprint was a two-day activation session. People had a chance to follow innovative behaviors on the first day and BEANstorm to encourage those behaviors on the second.1

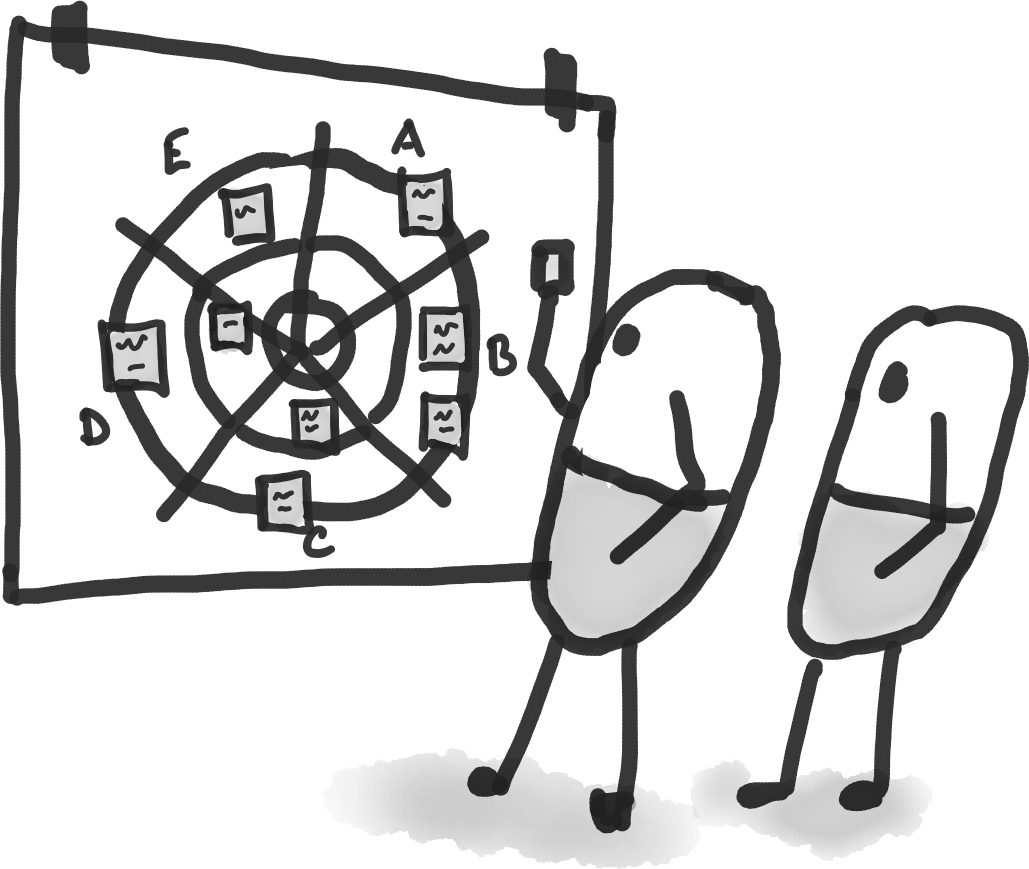

We’ll detail the work that preceded and followed the activation session, the session itself, and the key lessons learned. This will be the most detailed chapter in the book, which we hope enables you to execute a similar sprint with your team, group, or department.2 Figure 4-1 provides a map to guide you through the chapter. At the center is the relationship between the sprint, the activation session, the BEANstorm, and the work after the activation session. The figure references the four steps we followed to create BEANs in Hyderabad and maps how activities in this chapter connect to those steps.3

Map of activities described in chapter 4

Numbers in parenthesis connect activities to process steps followed in Hyderabad

Preparing for the Activation Session

While it might seem tempting to jump straight into a brainstorming activity, our experience suggests that four activities (summarized in table 4-1) help maximize the impact of a more comprehensive activation session. The first two, determining desired behaviors and diagnosing the current state to identify blockers, match the first two process steps described in Hyderabad. The next two, identifying activation-session case studies and preparing for the activation session, set the session up for success.

|

Specific step |

Description |

|

|

Determine desired behaviors |

Pick the desired behaviors you want to encourage, with a default view of the five behaviors from chapter 1. |

|

|

Diagnose the current state and identify blockers |

Identify potential blockers that are inhibiting your ability to follow the desired behaviors. |

|

|

Identify day-one activation-session case studies |

Identify specific problems to solve to showcase the impact of following the desired behaviors. |

|

|

Create material and form working teams |

Create customized stimuli and determine key champions and sponsors for small-group work. |

Determine Desired Behaviors

Remember, a culture of innovation is one in which the behaviors that drive innovation success come naturally. A critical component of the culture sprint is to determine the specific behaviors you seek to encourage. While there might be some temptation to develop a custom set of desired behaviors, for the purposes of developing an alpha culture, we find it helps to start either with the generic behaviors defined in chapter 1 (be curious, customer-obsessed, collaborative, adept in ambiguity, and empowered) or with other already-agreed-upon desired behaviors.4 For Singtel we picked the five generic behaviors.

Diagnose the Current State and Identify Blockers

The activation session will have the most impact if you come into it with a perspective about the behaviors you currently follow, the ones you do not, and the biggest blockers.

There are three specific ways to diagnose the current state and determine what actually are your organization’s day-to-day behaviors. A good starting point is to take either qualitative comments from existing organizational culture surveys or publicly available comments by current or former employees on sites like Glassdoor. Inputting text into one of the many word-cloud generator apps or websites quickly and effectively generates a visual map of employee perceptions about the current culture. Do words related to the desired behaviors appear frequently? Or does it look more like the word cloud in chapter 2, which prominently featured words like “fear,” “inertia,” and “bureaucracy”?

A second technique is to conduct one-on-one interviews. For Singtel we interviewed a cross section of the HR team. We interviewed those in business partner roles who interacted with the business units and those with more internal functions, such as payroll. We interviewed people with decades of tenure and people who had joined within the last two years. We interviewed Singtel lifers and people with prior experience at multinational companies; those who had worked only in Singapore and those who had significant overseas experience; highly engaged and enthusiastic team members and those more prone to express skepticism. This variety ensured divergent perspectives and helped us avoid the risk of anchoring on the strongly held views of a minority.

We asked interviewees to state a handful of one- to three-word answers to the question, “How would you describe our culture today?” As always, it is good to seek examples and anecdotes to add specificity and richness to the diagnosis. For example, one interviewee described how, when they were dealing with a personal issue, they received a care package from Tan and the leadership team. That is a potential strength to build on, as caring about the team could easily extend to caring about the team and the customer.

Finally, you can administer a diagnostic survey. That can be as simple as asking people the degree to which they regularly follow the five innovation behaviors. The appendix has two other surveys you can use: a simple, somewhat tongue-in-cheek way to assess the “status of your relationship with innovation” or a more comprehensive culture-of-innovation survey. The comprehensive survey, which we used both at Singtel and DBS, explores four areas:

- To what degree do employee perceptions match what you would expect to see in a strong culture of innovation? Perception-related barriers indicate that people think innovative behaviors are not worth their time or effort because, at best, they will have little impact and, at worst, they risk being punished.

- To what degree are people following specific behaviors? The survey asks questions about the last time people followed behaviors tied to desired ways of working, such as praising someone for taking a risk at work. Have they never done it? Have they done it sometime in their life? Within the last year? Within the last month? Within the last week?

- To what degree do people have the specific skills to do these behaviors well? While self-reporting has its problems, the survey asks people to rate themselves on more than a dozen enabling skills, such as experiment design and execution.

- To what degree are there enablers in place that would help innovative behaviors stick and scale? The survey asks a range of questions that look at the systems and structures that fight against the shadow strategy (some of these systems and structures are detailed in more depth in part II).

Whatever diagnostic tool you use, you should be able to identify clear and obvious areas to address. For example, Singtel has a reputation for expecting very buttoned-up analysis to back up decisions. What do you do, one interviewee wondered, with an innovative idea about which data simply didn’t exist? Would it expose the person who submitted the idea to fierce questioning that they couldn’t answer? Another issue that emerged was a top-down directive culture that inhibited HR leaders from feeling empowered to deliver the digital future.

Identify Day-One Activation-Session Case Studies

Culture change and the value it creates can be hard to grasp. At best, it is vague and, at worst, it can be called “woolly,” “nebulous,” or even “airy-fairy.” How can you help people viscerally understand why culture change, and, more specifically, granular changes to ways of working, are worth the time and investment? Nothing substitutes for the firsthand experience of seeing how desired behaviors help to solve real organizational problems. So this step involves identifying case studies—namely, specific problems facing the organization—that will be addressed during the activation session.

As Richard Pascale famously said, “Adults are more likely to act their way into a new way of thinking than to think their way into a new way of acting.” As such, we worked with the HR team to identify real problems that people could work on during the first day of the activation session. We wanted people to experience the tomorrow culture where innovative behaviors were second nature. Showing how these behaviors drove tangible progress against real problems—problems they cared about solving—helped them understand the value of adopting new behaviors, making the BEANstorm resonate more deeply.

Ideally, selected problems have three characteristics. First, they should be material. Second, they should be bounded tightly enough to allow teams to make material progress in a short time. Third, they should be open-ended enough that there is space to explore alternative solutions. In Singtel’s case, we identified problems statements—questions starting with “how might me”—like the following:

- How might we provide an awesome first-day onboarding experience for any new joiner?

- How might we engage more deeply with alumni?

- How might we maximize the impact of the recently renovated employee collaboration space for which the HR team is responsible?

For each problem, we developed a one-page overview of the problem to share with working teams. We also identified real “customers” that teams could talk to in order to gain deeper insight about the problem (discussed more below).

Create Material and Form Working Teams

The final piece of prework involves two activities. The first is to create relevant material. For Singtel, we created packs for each participant that detailed the desired innovation behaviors, explained the problem they would be working on, and summarized key lessons from the diagnostic work. We also created “BEAN cards” to serve as stimuli.5 Finally, we designed detailed instruction guides and capture templates.6

The second prework activity is to form the working teams for the session. At Singtel, each team had a mix of roles and tenures. We spread Tan’s leadership team across the working teams. We told these leaders that they should be team sponsors and would assume responsibility for driving the solutions created on day one of the workshop. Critically, we told them that they should be in “coaching” mode, which fit with the overall theme of shifting toward a more empowered culture. We also identified a small group of “catalysts,” who we spread among the teams, to be responsible for carrying the work beyond the activation session.

Our experience suggests that this prework can be done in around a month. As mentioned, that requires agreeing to use the “generic” view of a culture of innovation described in this book. Sometimes, though, it is necessary to take more of an outside-in view of what it will take to succeed in a changing competitive environment, which requires external research and discussions with senior leadership. But however you choose to approach it, keep the metaphor of a sprint in mind—you aren’t seeking to create a perfect culture; rather, you are trying to put multiple elements together rapidly, to see what works and what doesn’t.

The Activation Session

The two-day activation session is the central component of a culture-of-innovation sprint. The first day provides a chance to experience a culture of innovation by using the five behaviors (or whatever specific behaviors you chose during the prework) to make tangible progress on real business problems. On the second day, the group BEANstorms to overcome identified blockers and make those ways of working habitual. That’s a lot of words, so let’s return to Singtel to see and feel a session in action.

Day One: Living Innovation

Forty-two Singtel Group HR members gathered in August 2018 for a two-day activation session. A design principle was to reinforce the idea of BEANs by using BEANs during the activation session. So Tan kickstarted the session by using an adapted version of Amazon’s Future Press Release (described in chapter 3). Tan’s future press release outlined how the HR team had led the way in creating the culture now deemed the “secret sauce” to Singtel Group’s overall success in digital transformation. This different approach to opening a work-related gathering piqued interest straightaway, as participants realized this would not be “just another workshop.”

The group then had a chance to live each of the five innovation behaviors to solve their selected problem, summarized in table 4-2.7

|

Behavior |

Description |

|

|

Collaboration |

Set teams up for success by reinforcing the collaborative behaviors needed to solve real organizational problems. |

|

|

Customer obsession |

Help teams truly understand what job to be done (problem) they are solving for their customer and why. |

|

|

Curiosity |

Help teams tap into their innate curiosity, question the status quo, and ultimately develop great solutions to the problem they have been assigned. |

|

|

Adeptness in ambiguity |

Help teams uncover the assumptions behind their solutions so they can navigate and de-risk key uncertainties. |

|

|

Empowerment |

Provide ways to accelerate the progress of shortlisted ideas while recognizing the efforts of those that fell short. |

LIVING “COLLABORATIVE.” Once the teams spent fifteen minutes orienting themselves to their problems, they had a chance to actively experience collaboration. It started by defining how they wanted to work together as a team in ways that accentuate collaboration. To surface and subsequently amplify the team’s various talents and experiences, each team member shared their unique “superpower.” This led to some introspection and humor as people gainfully explained their various powers to their newly acquainted team members. Next, they reflected on how the various superpowers shared could help them collaborate better as a team. The exercise sometimes uncovers surprises, like the lawyer who writes poetry, or hidden skills, like the HR representative who studied finance and has experience in financial modeling.8

At this point another infused BEAN came into play: DBS’s MOJO program (detailed in the DBS case study after chapter 2). Each team appointed a meeting owner (MO) and joyful observer (JO) to ensure more effective discussions and collaborations. The sidebar “Natalie’s Favorite Ice Breakers” has additional tips for encouraging session members to enter into “collaborative” and “customer-obsessed” modes.

LIVING “CUSTOMER OBSESSION.” To help the teams better understand the problems they were solving they next followed the behavior of customer obsession. We shared the foundational concept of the job to be done: the fundamental problem a customer is trying to solve in a given circumstance (described in more depth in several of Innosight’s books). We also shared practical tips to discover jobs to be done during customer discussions, such as:

- Ask why, then ask it again. (This helps get to underlying causality.)

- Start broad to understand the context.

- Ask neutral, nonleading questions.

- Do not provide multiple choices; just pause.

- Be precise: set a limit of ten words to a question.

- Trust actions over statements: encourage stories or ask for a demonstration.

This wasn’t abstract instruction. Each team then received a profile of a real customer they would meet, a simple interview guide to help prompt probing questions, and a template to capture the answers.9 For example, the interview guide for the team solving the onboarding issue prompted them to get the customer to walk them through her own onboarding process, step by step, describing her emotions and digging into specific frustrations to help them identify places to innovate.

Armed with these guides, each team set off to various parts of the building to meet and interview real customers about their real business problems. Alumni came to share their views with the alumni team, the onboarding team interviewed employees who had joined that month, and so on. These customer interviews helped each team to build fundamental insights and to frame the problems they were solving from the perspectives of the customers they were serving—an imperative for the customer-obsessed organization.

Natalie’s Favorite Ice Breakers

Natalie has extensive experience designing and executing experiences for Innosight clients and colleagues. In addition to the “playlist” icebreaker described in chapter 3, she likes using the two openers detailed below to help would-be BEANstormers get into collaborative and customer-obsessed modes.

The first icebreaker is a simple way to help participants to get to know each other while also entering into customer-obsessed mode. Have every member of a group write down his or her favorite show, podcast, and book on a whiteboard wall with their name next to it. You don’t even need to have a formal debriefing to discuss the list items; people can ask each other during breaks why they like the shows, podcasts, or books they do to learn more about them. You get a surprising amount of energy from this activity and a nice artifact at the end.

Another powerful exercise is called the “river of life.” In this exercise, people pair up and spend fifteen minutes jotting down key moments of life, both highs and lows, along a winding river that serves as a more visual way to display a timeline. Then each member spends another fifteen minutes sharing their river with their partner. The listening partner must ask no questions but listen actively to understand what the other person values and feels is important. Once the fifteen minutes is up, the partners swap roles. The activity ends with the partners taking turns sharing what they heard as the other person’s values and motivators. This is an effective way to quickly learn about another person and to practice the active-listening skills necessary for effective interviewing.

LIVING “CURIOSITY.” With the job to be done now clear, teams embraced curiosity to develop innovative solutions. Each team received prepared stimuli to help them broaden their thinking and question the status quo. The stimuli included HR trends, technologies, and relevant case studies from organizations that had created innovative solutions to similar problems. For example, the onboarding team considered trends such as rising employee expectations and the role that a technology solution—such as one that enabled verified electronic signing of employment contracts—could play in their solution. An inspiring case study outlining how L’Oréal’s culture app assists its 11,000 yearly new-hires to understand, decode, and master their unique company culture supplemented this. Case studies help reinforce the idea that the curious seek inspiration from those who have solved their problems before, whether they are in related fields or in fields as unrelated as cosmetics is to telecommunications.

To develop and prioritize solutions to a customer job to be done, teams referenced the stimuli and followed the same structured “diverge to converge” ideation process that Innosight uses in its innovation consulting work. There is no great secret to this process, but our experience leads to three practical suggestions:

- Give people a few minutes to think on their own, which helps to avoid groupthink and creates a broad base of different ideas.

- Give people more than one chance to develop and edit ideas.

- Keep the timing tight to keep energy high. Better to leave people wanting more than to have them get bored!

Another suggestion is to ask people specific questions that can open up new avenues for exploration. For example, you might ask workshop attendees to consider the following:

- How might we address pain points or frustrations?

- How might we enhance what is currently working?

- What would “awesome” look and feel like?

- How might digital technologies help?

LIVING “ADEPTNESS IN AMBIGUITY.” At this stage each team had a solution on paper. But every innovative solution is partially right and partially wrong. The trick to successful innovation is to figure out, as quickly and cheaply as possible, which parts are which. This requires navigating strategic uncertainty through disciplined identification of critical assumptions and rigorous experimentation.

And so, the participants experienced what it was like to experience adeptness in ambiguity. They received a quick dose of innovation theory on assumptions (drawing on content from Scott’s book The First Mile) and undertook exercises to practice identifying and organizing assumptions. The teams identified their biggest assumptions about their solutions and considered the impact it would have if those assumptions were wrong. High-uncertainty, high-impact assumptions need tackling first, so teams designed experiments that could address those critical assumptions. By the end of this activity, each team had completed a simple template describing their idea, a version of which appears in figure 4-2.

Idea capture template

LIVING “EMPOWERMENT.” An empowered team exercises initiative to make decisions confidently and takes responsibility for their actions. To reinforce this empowerment, Tan had pre-agreed to implement at least one solution from the group, under the sponsorship and guidance of the selected team’s senior leadership representative.

Each team pitched their proposed solutions. Some simple yet highly effective ideas emerged. For example, the team creating an awesome onboarding experience learned that new joiners often arrived early on their first day. Then they sat and waited in the reception area, unclear of what was in front of them. The experience increased the anxiety that naturally accompanies a first day. So the team decided to issue new joiners, before their first day, a coupon for the café located in the reception area. This provided a double benefit, showing hospitality and filling an otherwise nerve-wracking time. This idea could also be expanded to connect several people being onboarded on the same day, so that the first cup of coffee could be a shared experience with someone in the same position. After all, the company’s raison d’être is to help people connect and communicate!

Day One Summary

After the applause died down for the teams whose solutions were approved to become projects, it was time for another BEAN. A cool box, previously hidden at the back of the room, emerged, and smaller boxes of popsicles (ice lollies in local vernacular) were taken out of it and handed to the teams selected by Tan. Next, boxes of premium ice creams, made by a well-loved brand, emerged. The twist? The “better” prize went to teams that “failed” the challenge. While popsicles versus premium ice cream runs the risk of being gimmicky, it highlighted an important point. A key environmental component to encourage innovative ways of working is psychological safety, in which intelligent failure is rewarded, not punished (more on this in chapter 7). The joy on the faces of those teams devouring premium ice creams while the winners diligently digested their popsicles admittedly amused the coauthors leading the session.

The first day concluded with two key messages. First, these behaviors are practical and powerful ways to develop and implement solutions to real problems, or—in the language in this book—to do something different that creates value. As such, the group left that day energized and committed to following the new behaviors. Second, these ways of working were not everyday habits inside Singtel Group HR. The next day explored why that was the case and what to do about it.

Day Two: BEANstorming

The second day of the activation session began with an energetic room committed to catalyzing culture change. The same teams that had spent the previous day living innovation to solve real HR business problems now turned their energy to creating BEANs that would hardwire these ways of working into their culture, becoming everyday behaviors and habits and unleashing the group’s latent innovation energy.

Each team had a broad way of working that it would focus on during the day (e.g., curiosity). After a quick grounding on the components of a culture of innovation, the teams went through a defined process where they got (even more) specific about desired behaviors, named detailed behavioral blockers, and then brainstormed about and refined their BEANs before pitching them to the group. Table 4-3 summarizes these activities.

A BEANstorm can help to hardwire behaviors into habits.

GET GRANULAR ABOUT DESIRED BEHAVIORS. The first step of the BEANstorm process requires teams to get granular, turning their allocated behavior from a lofty term into specific ways of working that fit their organizational context. For example, the team tasked with the curiosity behavior defined more specific ways of working such as not being complacent, being open to new ideas, and adopting a learning mindset. Each team had a detailed report from the culture of innovation survey to guide the discussion. Teams then got even more specific, describing what it would look like if they followed this behavior on a day-to-day basis in HR. For example, an HR leader adopting a learning mindset would strive for continuous individual improvement and regularly upskill himself.

|

Activity |

Description |

|

|

Get granular about desired behaviors |

Define and prioritize specific behaviors to encourage (“It would be great if we could …”). |

|

|

Identify behavioral blockers |

Identify and share what stands in the way of regularly following desired behaviors (“But instead we …”), with a particular focus on existing behaviors or habits. |

|

|

Brainstorm and refine BEANs |

Complete simple templates and get rapid feedback from other teams about how to encourage the identified behaviors and overcome the selected blockers (“So we should …”). |

|

|

Pitch and select winning BEANs |

Have each team pitch their BEAN and select winners for implementation. |

If a team got stuck in this activity, they were encouraged to complete the statement, “It would be great if we could …,” as precisely as possible. The goal here is to establish a behavior versus a state of mind, so you want verbs, which result from saying, “We will do this,” versus nouns, which result from saying, “We are this.” The more specific, the better. For example, one group working on collaboration started with “We will break silos” as a desired behavior before going deeper to state, “We will staff project teams with representatives from at least three functions.”

Once each team established a long list of both broad and specific behaviors, they prioritized the one behavior they felt would have the greatest impact on their culture if established as an everyday ritual or habit. Prioritization is important. The more specific the behavior, the easier it is to create high-impact BEANs. Trying to solve for multiple behaviors risks overly complicated BEANs. Getting granular helps to maximize impact.

IDENTIFY BEHAVIORAL BLOCKERS. At this point, each team had defined with some specificity ways of working that encapsulated the given behavior and had described what that would look and feel like in practice. They next turned their attention to describing what is currently blocking these behaviors. In other words, why aren’t these behaviors happening already? The group brought up and discussed blockers that many readers will likely find familiar, such as being overly metric-oriented (key performance indicators, or KPIs, in the case of Singtel), jumping straight to solutions, and being afraid to make mistakes. Not to be a broken record, but the more granular you make the blocker, the better. We see people frequently start with blockers like “We don’t have time” or “We don’t have proper training.” These kinds of superficial blockers seem easy to fix. For example, if you lack skills, either invest in training, hire new people who have those skills, or form a team of experts to accelerate progress. Our experience shows, however, that blockers are typically more subtle. Culture is complicated and interdependent. If you don’t get under the surface, interventions won’t work. In other words, if you give people more time, they will often fill it by continuing to do things the wrong way. If you train them in new skills, they often won’t use them, because they don’t fit existing routines. And so on. What you want to identify is what we call a “behavioral blocker.” In other words, your goal is to follow behavior A (“It would be great if we could …”). But, instead, you are following behavior B (“But instead we …”).10 If you are brainstorming about blockers and you hear someone say something superficial, ask, “Why do we do this?” or “Can you be more specific?” For example, one group we worked with said fear was blocking its desire to be adept in ambiguity. Digging deeper surfaced their fear that a leader might ask for more data on an idea, which would lead to more work. So in meetings, instead of proposing that they test an idea, which they worried would bring extra work, they would sit silently.11

Clearly, the more crisply you identify what is blocking the desired behaviors, the easier it is to develop a high-impact way to overcome it. Discussing blockers can be difficult, however, because instead of focusing on positive, affirmative behaviors, participants are looking at the challenges, which means the conversation can easily become despondent and discouraging. It is hard to discuss something that is often subtle or even countercultural. So bring some levity to it. For Singtel, we built a wall. We told each person to pick up a tissue box that had been spray-painted brick-red and yellow. Each person wrote down the biggest blocker to his or her own target behavior on the brick and signed it. Then as Pink Floyd’s “Just Another Brick in the Wall” started playing, each person came forward and ceremoniously placed a brick on the ever-rising wall. As you can imagine, forty-two-plus (because several enthusiasts made more!) tissue boxes stacked on the floor creates a reasonably sized wall. And the group physically dismantling the wall at the end of a day of BEANstorming is a powerful moment. Further, the ritual of group construction brought the blockers to life and created the opportunity for another ritual: at the end of the day, people could retrieve their bricks and place them on their desks. There, the bricks would serve not only as a handy source of tissue but as a daily reminder of the blockers they were striving to overcome. (For another approach to surface and describe blockers, see the sidebar “Surfacing Blockers at DBS.”)

BRAINSTORM AND REFINE BEANS. Each team now knew what it needed to do: find a way to encourage a specific behavior or overcome one of the blockers in the wall that occupied a significant amount of space in the room. At this point, we formally introduced the idea of a BEAN. Of course, people had used BEANs such as Amazon.com’s Future Press Release, DBS’s MOJO, and our popsicle and premium ice cream prizes, but we had consciously avoided going deep into BEANs until this moment. We described what BEANs are, why they work, and what the elements of a successful BEAN are, drawing on the material detailed in chapter 3.

Teams then followed the same basic diverge-and-converge process used the day before to create solutions to their business problems. Each team received customized stimuli, including relevant videos and a curated “bag of BEANs.” The bag contained cards that showcased examples of organizations from around the world that had created BEANs relevant to behaviors and specific ways of working. For example, the “adeptness in ambiguity” team might consider Spotify’s Fail Wall, which publicly shares a team’s failure so that others can learn from it. As Pablo Picasso famously said, “Good artists copy, great artist steal.”

Surfacing Blockers at DBS

As part of helping DBS purposefully shape the culture at Hyderabad, Innosight commissioned Tom Fishburne to create customized cartoons. (Tom is a Harvard Business School graduate who runs a boutique agency that develops cartoons for business purposes.) One cartoon he created shows a harried executive addressing a group of people, saying, “Does anyone else have a hypothesis they would like to test?” Meanwhile, the previous responder to his question squats in the corner in shame. This resonated with Singaporeans, in particular, as this is a traditional school punishment for bad behavior in that locale. Another illustration shows an executive assistant at his desk, holding out his phone’s receiver to an executive rushing past him toward a full conference room. The assistant says, “The voice of the customer is on line two.” The hassled executive responds, “Take a message. We’re having a meeting on customer obsession.” A meeting on a topic crowds out actually doing the topic? Golden.

Cartoon DBS used to highlight meetings as a blocker to customer obsession.

Source: Tom Fishburne, Marketoonist.

The cartoons themselves were a great way to start discussions about how DBS would really become adept in ambiguity and customer-obsessed, but the process of coming up with them was just as important. We had a cross-functional team of DBS leaders who all cared about shaping the bank’s culture. Tom led them in conversation to uncover specific stories that showcased DBS’s falling short of its aspiration of being a 28,000-person startup. Their discussion time was candid and critical, but it was also filled with laughter as people recounted the day-to-day foibles that are all too typical inside organizations. The team left engaged and eager to solve the problems, and the resulting cartoons made it safe for broader groups to engage in conversations whenever they saw executives clinging to old ways.

In a 2018 TED talk, Fishburne shared his perspective about the power of humor in business contexts. “I think that what gets in the way is fear. I think it is exactly the same fear that keeps us from trying new things, keeps us stuck in the status quo, and holds us back from doing our best work,” he said. “And I think that a sense of humor is one of the most important, but completely overlooked, tools in business. If we really want to overcome that fear, we have to learn to laugh at ourselves.”

By the end of a high-energy forty-five-minute session, each team had completed an initial template outlining the behavior they wanted to encourage (“It would be great if we could …”), the behavioral blocker they needed to overcome (“But instead we …”), a sketch of the BEAN, and a description of how it combined behavior enablers, artifacts, and nudges to drive change. A version of the BEAN template appears in figure 4-3.

BEAN capture template

Armed with their draft BEANs, each team then followed a “speed-dating” process to get rapid feedback. Two “BEANbassadors” were appointed by each team to rotate around the room and showcase their BEANs to receive feedback from their colleagues against five questions:

- Can we imagine implementing this BEAN within Singtel Group HR?

- Will people have sufficient incentives to incorporate the BEAN into day-to-day life?

- Can we imagine using the BEAN repeatedly?

- Will it be effective in driving behavioral change?

- How will we define and measure the success of the BEAN?

After digesting the feedback, teams refined the BEANs and developed plans to operationalize them. Teams detailed how they would launch their BEAN and how they would track and measure it.

PITCH AND SELECT WINNING BEANS. Finally, each team pitched their resulting BEAN to their colleagues and Tan. We encouraged the groups to bring energy to the pitch by role-playing a skit that brought their BEAN to life (and brought a bit of levity to a reasonably grueling two days). Singtel Group HR leaders evaluated the most feasible, high-impact BEANs and approved those that met the criteria to progress.

Time for one last BEAN infusion! This time the Innosight team introduced an adapted version of Adobe’s Kickbox (described in chapter 3). The “Singtel Group HR Kickbox” that each winning BEANstorming team received contained a half day of leave for each team member, which they could devote to developing the idea further, another half day of paid time off as a reward, and a S$500 credit to fund the BEAN’s refinement.

One example BEAN included an idea to reinforce customer obsession. The behavior the team wanted to encourage was to bring the voice of the customer (in this case, Singtel employees) into every HR discussion. The behavioral blocker identified was that Singtel typically started discussions with questions like “What are we planning on doing?” and not “What problem are we trying to solve?” or “For whom are we solving that problem?” As a result, the HR team too frequently succumbed to overly inward thinking. The core behavior enabler was a proposed ritual to make sure that every meeting included discussion around the question, “Who Is The Customer Here?” (which forms the memorable acronym WITCH). In addition, they would seek to answer, “What is the concern?” and “What is the conclusion?” The WITCH acronym lent itself to multiple artifacts to reinforce the idea. A few months after the workshop, employee laptops began to don WITCH stickers that featured a witch’s hat as a visible reminder (and a nice nudge) that everyone has a customer and that this customer has jobs to be done that need solving. Around eighteen months after the activation session, Tan told Scott and Andy at a catch-up meeting that she believed the WITCH BEAN was having a significant impact on the HR group, and she shared stories reinforcing its power to focus them on constructive discussions around the customer, the concern, and the conclusion, in turn ensuring more effective and efficient decision-making.

Keys to Success

The Singtel example shows that there are three key factors to a successful two-day activation session and BEANstorm.

FIRST, PROVE WHY CULTURE MATTERS BEFORE SOLVING CULTURE. People must live new behaviors before they design ways to encourage and enable them. Just because almost everyone intuitively understands the importance of culture does not mean that everyone is willing to dedicate time to progressing culture. Providing firsthand experience about the power of particular behaviors is the best way to convince people of the importance of BEANstorming in order to enable those behaviors.

SECOND, GET GRANULAR. The more specific the behavior, the more specific the blocker, the better the BEAN. BEANs work well when targeting a specific behavior, such as bringing the voice of the customer into meetings, instead of targeting a broader way of working, such as customer obsession.

THIRD, INFUSE BEANS WHEN CREATING BEANS. A great BEANstorm should include BEANs. These not only make the BEANstorm more fun and engaging, but they reinforce the idea that a great BEAN has power to improve the way we work.

After the Activation Session

It is tempting to declare victory after a great activation session. Recall, however, the fourth step in the process described in the Hyderabad case study: implementation. Even the best preparation and most engaging BEANstorm will leave you with, at best, rough output. That’s why we often call the session that contains the BEANstorm an “activation session.” A typical BEANstorm creates merely kernels of what might become truly great BEANs. As people reenter the host organization, their enthusiasm for planned interventions can dissipate as the shadow strategy descends and they revert to old habits.

Finishing a culture-of-innovation sprint requires that shortlisted BEANs are refined, tested, modified, and, if successful, launched and scaled. That means that there needs to be a person and, at best, a team accountable for executing and continually improving the BEANs based on data. In addition, this can’t be the thirty-fifth responsibility of someone who already has too many things on her plate. It must be someone’s top priority.12

In Singtel’s case, a small team of catalysts iterated and implemented the workshop BEANs, such as WITCH and ideated new BEANs. The team also developed innovative ways to communicate concepts discussed in the workshop to the broader HR community. They engaged a local music artist to create a jingle that made their ways of working more memorable. Finding ways to make new language and concepts easy to remember helped to reinforce understanding and further fuel culture change.

The end of the sprint doesn’t end the culture change journey; it simply marks the beginning of the next stage of the journey. The sprint itself starts with generic desired behaviors, surfaces blockers that are typically still somewhat superficial, and develops a handful of BEANs. Interventions focus narrowly on a single team, group, or department, and the constrained time and focus mean avoiding deep work on supporting systems and structures. Therefore, the beta stage of the process moves from being a sprint to executing pilots that expand to more places in the organization. At this stage, people work on customizing behaviors, determining the “blockers behind the blockers,” building additional BEANs, and developing an understanding of the supporting infrastructure required to nurture the culture of innovation. Work then becomes more formalized, with people settling into recurring roles. Following the pilot stage is the full launch, where you develop a repeatable playbook that shows how to identify and launch new BEANs, stand up the infrastructure that will be necessary to reinforce identified behavior change (including people formally responsible for setting up the infrastructure and managing culture on an ongoing basis), and bust through key blockers.

DBS used a tool called the Culture Radar to help with its culture change journey. Based on a concept created by the company Thoughtworks to track emerging technology, DBS plotted each BEAN experiment on a paper chart consisting of concentric circles. Each segment on the radar corresponded to a target behavior, and each circle represented where the experiment was being run. To use the chart, Paul’s team placed each BEAN in a segment with the related target behavior. A BEAN in its experimental stage that was being piloted with a single team would go near the outer edge of the radar. Over time, Paul and his team would review the radar on a regular basis. BEANs moved closer to the center as their adoption increased, until they made it to the bullseye, representing companywide adoption. Unsuccessful BEANs were removed from the chart. This visualization made it easy to track progress, identify gaps, and reinforce the expectation that not all BEANs would succeed. And the Culture Radar is, of course, a BEAN itself.

Table 4-4 summarizes the stages of the culture change journey, and tools and inspiration to help with that journey are included in part II. Finally, the appendix describes key themes from the culture change literature.

|

Alpha/Sprint |

Beta/Pilot |

Full launch |

||||

|

Implementation focus |

Narrow (a single team, department, or function) |

Expanding (two to three teams, departments, or functions) |

Expansive |

|||

|

Behaviors |

Broad behaviors taken as given (five innovation behaviors); specific behaviors defined at a rough level |

Customized broad behaviors and more-detailed specific behaviors |

Codification of behaviors in a culture playbook |

|||

|

Blockers |

Identification of one to three clear and obvious surface-level blockers |

Identification of “blockers behind the blockers” informing supporting infrastructure recommendations |

Core blockers removed with interventions now focused on the blockers behind the blockers |

|||

|

BEANs |

One to three “good enough” BEANs are identified and launched |

Initial BEANs are refined and strengthened; new BEANs are launched |

BEAN-creation methodology is codified and distributed |

|||

|

Infrastructure and environment |

None |

Recommendations for developing supporting systems and structures |

Recommendations for supporting systems and structures in the process of being implemented |

|||

|

Supporting resources |

One to two ad-hoc catalysts |

An emerging catalyst team |

A formal catalyst team |

|||

|

Supporting documentation |

None |

A draft of a “culture playbook” (including an inspirational description of the tomorrow culture) |

The finalized culture playbook |

|||

|

Length |

Four to six weeks |

Two to three months |

Ongoing |

Chapter Summary

- A sprint is a powerful way to create an alpha version of a culture of innovation within a team, group, or department.

- The core of a culture sprint is a two-day activation session. Day one of the session provides an opportunity for attendees to “live” the desired behaviors, while day two focuses on BEANstorming.

- The activation session should be preceded by focused activities to define desired behaviors that make sense in a particular context, to identify blockers, and to create customized BEANstorming stimuli.

- Driving toward impact after the activation session requires focused resources that cultivate and nurture existing BEANs and create new ones. It also requires a concerted movement to spread, scale, and reinforce the culture change.

1. BEANstorm really wants a trademark on it, doesn’t it?

2. “Most detailed” is code for “longest.” This clocks in at more than 8,000 words, so grab your beverage of choice and nestle in!

3. Thanks to our favorite reviewer Thomas for suggesting these visuals and helping us to keep all of these pieces straight!

4. For example, one large healthcare company wanted to focus on accountability, agility, and entrepreneurship, which we deemed to be more than good enough to start.

5. One hundred one BEANs appear in this book. Forty-two are described in depth in parts I and II (MOJO in chapter 2, our five favorite BEANs and two Innosight BEANs in chapter 3, three BEANs in the Hyderabad case study, a Singtel and a DBS BEAN in chapter 4, and twenty-nine BEANs in part II), and the “Bag of BEANs” in the appendix has another fifty-nine. During workshops, we print simple cards that describe the BEANs. We have been amazed at how excited people get about these cards. You can find versions of them at www

.eatsleepinnovate ..com 6. Generic versions of all of this material are available at www

.eatsleepinnovate . Let’s be honest: we’d be happy if some of you called Innosight and asked for our help (well, that matters less to Paul, but he still likes the Innosight team, so he would be happy for his three coauthors), but one of our core values is transparency, so we believe openly sharing our tools and methods is the right thing to do!.com 7. Careful readers might wonder why the order of behaviors here differs from that in chapter 1. The list presented in chapter 1 follows the general process of innovation: being curious kicks off the process, being customer-obsessed surfaces the problems to solve, being collaborative aids in developing solutions, being adept in ambiguity refines those solutions, and being empowered helps to launch and scale innovation. However, we have found that it “feels right” to have collaboration come first in a workshop context as it helps groups orient for the day.

8. It also can uncover largely irrelevant but humanizing facts, like one author’s (nearly) unblemished track record at Whack-a-Mole. Okay, it’s Scott. Bring it on!

9. Again, generic versions of these can be found online. And, of course, there are lots of other good tools and templates out there that overlap with what we did on day one. Use what works for you!

10. In Immunity to Change, professors Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey call this a “competing commitment” and note that it is often done for very rational reasons to protect people from shame and guilt. Humans, as always, are complicated.

11. There’s a great term in the psychology literature that relates to this: social loafing.

12. A couple of years ago, Scott was at a conference where someone said the word “priority” had been singular only until about a hundred years ago. Indeed, the dictionary definition of “priority” references “being regarded or treated as more important than others.” Of course, today, we all have multiple priorities, including ones that seem to be in conflict. So our rule of thumb here is to designate at least one person to have “Driving BEANs forward” as their most important project.