6 Culture as a determinant of material welfare

Introduction

The potential role of values and norms and, more generally, of cultural factors as causal variables affecting the path and pattern of economic growth and development has become subject to considerable debate in academic circles and among public policy experts. Economic theory, however, especially the dominant neoclassical variant, does not well incorporate cultural factors as independent and causally substantive variables with respect to economic growth and development. Rather, strictly economic variables such as capital stock, technological change, and human capital are touted as being the major explanatory variables affecting growth and development irrespective of cultural setting. Articulating the cultural setting of an economy and, more specifically, of economic agents, is assumed not to add substantively to either the predictive or explanatory power of economic theory. For this reason, the conventional economic wisdom pays little heed to cultural factors in developing explanations of economic problems (Jones 2006).

In this chapter culture is introduced into a behavioral model of the firm as a causal variable in the growth and development process and, more specifically, as a determinant of labor productivity and thereby of the level of gross national domestic product. In this sense it introduces culture as an additional variable in the production function, not unlike what Max Weber in effect does in his classic, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1958). This does not deny the fundamental importance of economic variables to the process of economic growth and development. It is only argued that cultural variables must be treated as one of the potentially important causal variables. In this sense, the circumstances under which culture is of causal significance are articulated. Following from this, a fundamental question in economics of the long- run survivability of inefficient economic entities in a competitive environment is addressed. Is it possible for low productivity economic regimes, which are low productivity for cultural reasons, to survive in the marketplace? Under what circumstances can one expect such inefficient economic regimes to survive? Only if such circumstances are not exceptional, can it be concluded that cultural variables are substantively important to the development and growth process.

In the behavioral model of the firm discussed in this chapter (for more details see Chapters 2 and 3), inappropriate cultures can be a cause of economic inefficiency and appropriate cultural precepts become necessary but not sufficient conditions for economic efficiency. This raises the issue of how can economic entities imbued with inefficient cultures and which are, therefore, inefficient themselves survive in the long run. Should not superior economic cultures drive out the inferior? I argue that this need not be the case even if economic agents are assumed to be rational utility maximizers in the Beckerian sense, that individuals do their best to maximize their utility as they conceive it in a consistent and forward- looking manner given the constraints that they face.1 Although culture can be causally important to both the growth and development process, the adoption of cultural norms and mores most conducive to maximizing productivity and therefore material welfare is far from inevitable. If the appropriate cultural environment to maximize material welfare is inevitable, as is assumed in the conventional wisdom, than the cultural attributes of a society related to economic questions cannot be subject of debate. If, on the other hand, the invisible hand does not inevitably and invariably produce efficient cultures, the question of the development and immutability of those cultural attributes that either enhance or hinder the development process come front and center both for analytical and public policy reasons. This would be true for scholars and public policy makers of differing ideological perspectives. As Daniel Patrick Moynihan put it: “The central conservative truth is that culture, not politics, determines the success of a society. The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself ” (Harrison 1992, p. 1).

What is culture?

One economist examining the role of culture in the growth and development process argues that “It can define group or national value systems, attitudes, religious and other institutions, intellectual achievement, artistic expression, daily behavior, customs, lifestyle, and many other circumstances” (Harrison 1992, p. 9). With respect to the question of the relationship between culture and development culture can be more narrowly defined as “a coherent system of values, attitudes, and institutions that influences individual and social behavior in all dimensions of human experience” (Harrison 1992, p. 9). Harrison refers specifically to the sense of community, the rigor of the ethical system, the manner in which authority is exercised in a society, and individual attitudes toward work, innovation, saving, and profit, as being of critical importance to an appreciation of the importance of culture to the process of development. Cultural attributes, for Harrison, can change even in short shrift and, therefore, being ahead or behind of the economic game for cultural reasons is no guarantee of future success or future failure. (See also, Harrison and Huntington, 2000.)

For Thomas Sowell, one of the foremost advocates for the importance of culture to the development process, the most relevant aspects of culture for the question of economic progress are: “those aspects of culture which provide the material requirements of life itself—the specific skills, general work habits, saving propensities, and attitudes towards education and entrepreneurship—in short, what economists call ‘human capital’ ” (Sowell 1994, p. 12). Some cultural attributes are more conducive to economic development than others and, for Sowell, cultural attributes tend to be relatively immutable even the long run. Therefore, little can be done to affect to the economic standing of individuals or groups whose differential economic standing is a product of their particular cultural attributes. His cultural factors tend to override the economic-political environment in which individuals and groups are situated. Individuals are a product or a prisoner of their cultural heritage that changes, if at all, slowly over time. Both Harrison and Sowell attempt to explain persistent economic differences between individuals, groups of individuals, and nations that appear to be most strongly correlated to cultural heritage or attributes and which apparently cannot be accounted for by economic factors alone.2

At a more general level Max Weber, writing in 1904 and 1905, regarded his longstanding classic study of the potential linkage between religion and capitalism as a modest “contribution to an understanding of the manner in which ideas become effective forces in history” (Weber, 1958, p. 90). This does not deny the importance of economic variables to the determination of development. Weber writes:

Every such attempt at explanation must, recognizing the fundamental importance of the economic factor, above all take account of the economic conditions. But at the same time the opposite correlation must not be left out of consideration. For though the development of economic rationalism is partly dependent on rational technique and law, it is at the same time determined by the ability and disposition of men to adopt certain types of practical rational conduct. When these types have been obstructed by spiritual obstacles, the development of rational economic conduct has also met serious inner resistance. The magical and religious forces, and the ethical ideas of duty based upon them, have always been among the most important formative influences on conduct.

(1958, pp. 26–27)

Those ideas or cultural attributes which are most conducive to capitalist development and to ultimate improvements in material welfare are not immutable to Weber, but are rather subject to change over time, education being of a fundamental engine of cultural change (Weber 1958, Ch. 2). A particular cultural heritage can either facilitate or impede certain behavior, but culture can change in response to changing circumstances including the economic environment.3

Weber’s conception of the relationship between culture and economics is notable given this chapter’s focus on the relationship between culture and material welfare. Weber writes:

capitalism is identical with the pursuit of profit, and forever renewed profit, by means of continuous, rational, capitalistic enterprise. For it must be so: in a wholly capitalistic enterprise which did not take advantage of its opportunities for profit-making would be doomed to extinction [or at least must not rise (ibid., p. 72)]. We will define a capitalistic economic action as one which rests on the expectation of profit by the utilization of opportunities for exchange, that is on (formally) peaceful chances of profit.

(1958, p. 17)

Moreover, in capitalism everything is done with an eye to profit and, “So far as the transactions are rational, calculation underlie every single action of the partners” (pp. 18–19). Such calculations need not be accurate, but simply the best possible given the circumstances which include, in the language of modern economics, imperfect information, transaction costs, and the level of human capital endowment. Also (pp. 21–22), rational industrial organization embedded in the marketplace requires the separation of the business from the household plus rational book-keeping. For Weber, rational capitalist behavior requires that individuals pursue the maximization of income or wealth as a “calling” for and of itself. In effect, individuals are instilled with a particular work ethic. Therefore, such individuals would contribute toward maximizing labor productivity and material welfare. But wealth maximization as a calling is facilitated by certain cultures (or religious orientations) and deterred by others. Although, according to Weber, as capitalism becomes the predominant mode of production, all economic agents are pressured into becoming wealth maximizers; that is into opting for the dominant economic mentality.4 Therefore, inefficient cultures cannot survive the onslaught of market forces, at least in the long run. But in the very important short run, cultural factors play an important role in determining the path and pattern of economic development (see Jones 2006, 2010, for a contemporary rendition of this perspective, albeit with a much stronger emphasis on cultural convergence).

The Weberian notion of economic rationality fits into the variant of conventional economic theory which presumes that rational utility maximizing economic agents are, at all times, in market economies, working as hard and as well as possible by dint of market forces. This worldview assumes that economic agents and, therefore, the economies of which they are part, are operating along the production possibility frontier. They are, in effect, maximizing output per unit of labor by maximizing the quantity and quality of output per unit of time. In neoclassical theory, economic agents maximize output per unit of labor given the implicit behavioral assumption that the cultural prerequisites for efficient levels of output (production possibility frontier output) are in place a natura. Ultimately, economic agents who are not productivity maximizers are doomed to extinction and economy becomes dominated by the productivity maximizing economic agents (Altman 1999d; Reder 1982).

The notion that culture can serve to facilitate or to impede economic efficiency (productivity maximization) is inconsistent with the conventional wisdom. For this reason it pays no heed to the role of culture in generating economic efficiency. Cost minimization whose flip side is productivity maximization is assumed to come naturally as a byproduct of rational behavior. Rational behavior, joined with long-run competitive market forces, are assumed to force the economy to produce along the production possibility frontier. Cultural differences can, therefore, not explain differences in productivity that are not expected to persist over time in a relatively competitive environment. Economies are expected to converge in terms of productivity and wages over time as a consequence of competitive pressures. A critical problem with this analytical prediction is that it has not been realized. Convergence has not taken place in a fashion predicted by the conventional wisdom (Altman 1999b; Baumol 1986; Baumol and Wolff 1988; DeLong 1988; Pritchett 1997).

Modeling culture

Culture has been explicitly introduced into the modeling of the rational utility maximizing economic agent by Gary Becker (1996) as one component of an individual’s social capital, where social capital, “incorporates the influence of past actions by peers and others in an individual’s social network and control system” (1996, p. 4). Social capital can have either a positive or a negative effect on utility where the sign of the effect depends on the type of social capital. Culture is that component of social capital which changes at a relatively slow pace and is largely given to individuals over their lifetimes. Individuals have some choice over their social capital and even over its cultural component to the extent that they can choose the social network or control system of which they are part (Becker 1996, Ch. 1).

Moreover, social capital is introduced into the economic agent’s preference function and is thereby explicitly introduced as a possible determinant of behavior. Becker’s modeling narrative, therefore, opens the door to modeling culture as a determinant of effort inputted into the production process; a move which Becker himself does not make.

Harvey Leibenstein’s (1966, 1978, 1987, x-efficiency theory and extensions to it (Altman 1996; Chapter 2 and 3)), serve as the basis for a behavioral model of the economic agent and of the firm where culture counts as a substantive determinant of material welfare. Developing his concept of x-inefficiency, Leibenstein argues that economic agents are typically producing less than they would under a relatively ideal set of circumstances, For Leibenstein, maximum productivity requires a cooperative system of industrial relations. Therefore, maximum productivity does not arise a natura. This view has received considerable support from ongoing industrial relations research (Altman 2002; Ichniowski et al. 1996; Levine and D’Andrea Tyson 1990). Leibenstein maintains that for individuals to produce below their potential or x-inefficiently, they must have the capacity to choose (effort discretion) the quantity and quality of effort which they input into the process of production, where effort discretion is a product, for example, of the costs of drawing up, signing, monitoring, and enforcing contracts.5 Firms producing below potential are assumed to be x-inefficient as opposed to being x-efficient.

According to Leibenstein, this type of behavior can persist only when firms and, thereby, economic agents are somehow protected from competitive pressures. This must be true since x-inefficient firms are producing at above the average cost generated in the relatively x-efficient firm according to Leibenstein's argument. Average costs are given by the following basic equation assuming, for simplicity, that labor is the only input into the production function:

where AC is average costs and w is rate of labor compensation, L is labor input, and Q is output. This equation can be rewritten as:

Average costs are determined by labor productivity and the wage rate. Ceteris paribus, the lower is labor productivity (the less x-efficient is the firm) the higher are the average or unit costs of production.

In a behavioral model of the economic agent developed in some detail elsewhere (Altman 1996; see also Chapters 2 and 3), economic agents are assumed to be rational utility maximizers from the perspective of the conventional wisdom (Stigler 1976; Becker 1996). In contrast to Leibenstein’s modeling, behaving in a manner that is consistent with x-efficient production need not be the standard for rational and utility maximizing behavior from the perspective of workers, managers, or owners given the constraints which they face and the arguments contained in their respective objective functions. Only under very specific industrial relations conditions would it be optimal or utility maximizing for rational economic agents, together, as members of a firm, to choose to perform x-efficiently.6

A fundamental underlying assumption of this model is that effort is a discretionary variable in the production process and is affected specifically by the work environment, which includes working conditions and wage rates, and, more generally, by the larger cultural environment of which economic agents are part. In other words, effort inputted into the process of production is not assumed to be fixed at some maximum, independent of the industrial relations and cultural milieu of the economic agent. Indeed, x-efficiency in production is achieved only in a relatively cooperative work environment, one which is thought to be the most conducive to workers maximizing their effort inputs into the process of production (Altman 2002; Chapter 1). In this model, labor costs, which incorporate wages plus all other costs related to the employment of labor and the construction and maintenance of a particular work environment, are positively correlated with labor productivity—an empirically based assumption rooted in the x-efficiency and efficiency wage literature.7 In this case, lower x-inefficient levels of output need not result in higher unit costs, nor need higher more x-efficient levels of production result in lower unit costs. In other words, higher labor costs offset higher productivity whereas lower labor costs compensate for lower productivity. Under these assumptions it is possible for the x-inefficient firm to remain competitive, in terms of average costs, at relatively low wage rates when wages are low enough to compensate for relatively low levels of productivity (equation (6.2)). In other words, firms comprising utility maximizing economic agents, can remain competitive in long-run equilibrium irrespective of their level of x-efficiency and even in the absence of protection proffered by monopolistic market structures, tariffs, subsidies, transportation costs, and the like. Moreover, under these conditions, members of the firm hierarchy do not gain materially from increasing or reducing the level of x-efficiency since changes in labor benefits both motivate changes in the level of x-efficiency and neutralize any impact that these changes might otherwise have on unit costs and profits. Of course, the extent to which changes in labor costs neutralize changes in productivity is an empirical question and is related to the structure of the production function.

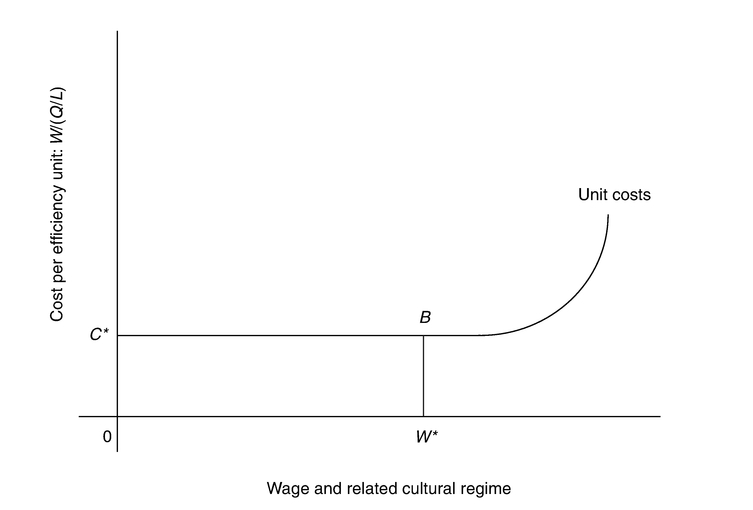

This is illustrated in Figure 6.1, where a unique unit labor cost 0C* is associated with an array of wage rates or labor compensation packages up a point W*, beyond which the quantity and quality of effort cannot be increased sufficiently to compensate for increased labor costs.8 The introduction of technical change into this model only serves to reinforce these results. When technological change is induced by changes in the cost of labor, the ability of high wage firms to survive on a competitive market is enhanced by increasing the firm’s productivity so as to compensate for the increasing cost of labor (Altman 1996, 1998, 2000b). In Figure 6.1, if the old technology yields a maximum wage of W* consistent with C* unit cost, technological change serves increases the maximum wage to W**. The cost curve shifts from 1 to 2. In this behavioral model, coupling x-efficiency and culture, we are assuming that the relatively efficient cultural regime is causally related to the relatively high wage economy, as illustrated in Figure 6.1. In this diagram an array of cultural regimes are coupled with an array of wage rates and these yield a unique unit cost up to point W*, given technology. These various cultural regimes are cost competitive because of the differential levels of x-efficiency with which they are causally related. The more efficient cultural regime would dominate all others if it yields a relatively lower unit cost.

In this specification of a behavioral model of the economic agent and the firm, cultural factors can be explicitly introduced into the production function to help explain, not only the productivity differentials between economies embodying different cultural regimes, but also that between firms, where firm size can range from one to a multiperson firm of a size consistent with a particular production function. Economies can comprise both relatively x-efficient and x-inefficient firms predicated upon different sets of values and norms. These values and norms are part and parcel of an individual’s social capital and can be either firm specific or part of an individual’s larger social environment. The importance of

Figure 6.1 Wages and cost.

culture, as a determinant of success on the marketplace, is only superficially consistent with the conventional wisdom. It assumes that the Weberian work ethic to be a natural attribute of born men and women and therefore not worth much talking about.

In the behavioral model, cultural factors become important as either facilitators or impediments to x-efficient production since they affect the choices made by the economic agent with respect to the quantity and quality of work effort.9 X-efficient production would not be possible without the appropriate cultural environment in place. Under different sets of norms and mores utility maximizing economic agents choose to work at different levels of efficiency. X-efficient behavior, one consistent with the Weberian work ethic, is only one possible long- run competitive result. To the extent that cultural variables are determinants of work effort, culture is important to economic well-being since it can contribute toward making economic agents more or less productive and, therefore, the economy of which they are part relatively more or less productive. Culture thereby affects whether or not an economy operates along its production possibility frontier. In a word, culture can affect the level of per capita real output produced in an economy and therefore the level of per capita material wealth produced in an economy as well as differences in the per capita wealth achieved by different economies at any given point in historical time. Efficient cultures serve to shift outward the familiar production possibility frontier.

In this type of modeling, unlike what is analytically predicted by Weber or by the conventional wisdom, the more efficient economies need not prevail over the less efficient economies, where relative efficiency is a product of particular sets of cultural norms and mores. This is point has been well made by Douglas North (1990, 1994; see also, Olson 1996), who argues that efficient institutions need not dominate the less efficient institutions for transaction costs reasons. The less efficient economies would include societies where wealth creation is built upon violence (Lane 1958) or slavery or serfdom (Domar 1970), as well as democratic societies built upon low wages and low productivity (Altman 1996; Gordon 1996). In the model presented in this chapter, the x-inefficient economies and corresponding cultures can remain competitive even under conditions of perfect product market competition. The x-inefficient economy, built upon a low wage regime, passes the neoclassical survival test, as does the x-inefficient firm. Market forces, therefore, do not necessarily result in economic agents adopting the Weberian work ethic.10

Culture is important when different cultural regimes, having differential and independent effects on the x-efficiency of their respective economies, can survive simultaneously over time. Market forces need not drive all economic agents and, therefore, the economies of which they are part into adopting norms and mores that are maximally conducive to x-efficient production. One culture can overwhelm another in long-run competitive equilibrium only if it serves to increase productivity in one economy such that its unit cost falls below the unit cost for like output produced in a competing and relatively x-inefficient economy under a different cultural regime. The latter approaches the world of the conventional economic wisdom.

The x-inefficient economy can remain intact in the face of unbridled competition from the more efficient economy in the absence of cultural change only if labor costs can be reduced without a compensating decrease in labor productivity. If one relaxes the assumption of competitive product markets, the x-inefficient economy along with its concomitant culture can survive if it is protected by monopolistic structures, tariffs and subsidies, and the like. In a competitive environment, the opportunity cost of maintaining economically inefficient cultures is a lower level of per capita material welfare and more specifically lower rates of labor compensation broadly defined. The latter are required to keep the x-inefficient economy cost competitive.

Conclusion

Conventional economic reasoning has paid little heed to culture as a determinant of wealth creation because it is assumed that cultural regimes that are not consistent with economic efficiency will not survive on the market at least over the long haul. However, in the behavioral model presented in this chapter, reasonable conditions are established whereby cultures conducive to either x-efficiency or x-inefficiency in production persist over the long run. The more efficient economic regime and the cultural infrastructure within which it is embedded need not possess a cost advantage over the less efficient regime. For this reason, culture can affect the level of economic well-being achieved by an economy or by a firm. Therefore, the behavioral model of the economic agent and the firm suggests that there are no good theoretical reasons to expect that the facets of contrasting cultures that are most closely related to work performance need converge toward representations consistent with x-efficient production, as predicted by the conventional wisdom. In such a world culture is of substantive importance and, therefore, understanding the intricacies of different cultures can contribute toward a better understanding of the economy.

If a particular cultural regime generates an x-inefficient economy, the opportunity cost of not engaging in some form of cultural change that is more conducive to increasing the economy’s level of x-efficiency, is the reduction of the average level of material well- being of members of such an economy. In other words, it might be possible to achieve higher levels of material well- being only at the expense of changing the values and norms of a firm or of the larger society so that they conform to those of the more x-efficient economy. This follows if a different set of norms and values are necessary to the achievement of a particular level of x-efficiency. In this sense, increasing the efficiency of a firm or of a society requires choosing one set of norms and values as opposed to some other. This is not to say that a utility maximizing individual will choose the more x-efficient society, especially if he or she places a relatively heavy weight on the cultural regime most consistent with the relatively x-inefficient economy. The preference for the x-inefficient cultural regime can be realized over the long term in a competitive environment, however, only if a low wage regime is accepted as a direct complement of such a cultural regime. A social dilemma arises if individuals want both the cultural milieu consistent with x-inefficiency in production and the material benefits that flow from an x-efficiency economy. Such a choice is not globally possible given a trade- off between a desired cultural regime and the level of x-efficiency. For this reason, it is critically important to appreciate and clearly articulate the opportunity cost involved in choosing one cultural regime over another.