14 Why unemployment insurance can increase economic efficiency

Introduction

The conventional wisdom argues that unemployment insurance serves to increase the rate of unemployment by various means. Unemployment rates are said to increase by attracting in to the labor market individuals who intend to quit their new jobs so as to collect this benefit, by increasing the voluntary job search time of those unemployed workers who are already in the labor force, by inducing increasing quit rates of the currently employed so that they search for better jobs, and by increasing the market wage thereby increasing the price of labor and reducing the overall competitiveness of the economy. Moreover, following upon the efficiency wage literature, unemployment insurance is expected to reduce the effort incentive effect of a given rate of unemployment, both forcing up real wages to compensate and, thereby, increasing the unemployment rate. It is further assumed that the marginal worker maximizes utility or economic well-being at low levels of real income thus allowing unemployment insurance to serve as a utility maximizing “wage of being unemployed.” Thus, some workers maximize their utility by getting themselves laid off so as to take advantage of unemployment insurance.

The available empirical evidence provides no unambiguous support for the conventional proposition that unemployment insurance damages the economy. It is critically important from both an analytical and public policy perspective to develop a theoretical framework that incorporates the empirics suggesting that unemployment insurance generates no long- run negative economic effects. Important aspects of such a theoretical revision rest upon the target theory of labor supply presented in Chapter 13. Situating itself in the context of the debate, this chapter is most concerned with critically evaluating the assumptions underlying the theory based arguments that various supply-side attributes of unemployment insurance increase the trend unemployment rate. To the extent that any of these assumptions are false, the negative analytical predictions that flow from standard analysis tend to be undermined, even prior to adjusting the basic model for institutional details and demand-side effects. Such adjustments, by themselves, would cast some considerable doubt on the validity of the conventional negative view of unemployment insurance (Atkinson and Micklewright 1991).

Focusing on the theoretical underpinnings of the conventional wisdom is critical since, without a convincing theoretical alternative, scholars and policy makers tend to doubt the validity or representativeness of empirical results that speak against the theory. Moreover, empirical studies examining the impact of unemployment insurance on unemployment rates are constructed such that the variables selected for the regression analyses and the expected results are conditioned by the theoretical worldview of the analyst. The door is open to spurious correlations and omitted variable problems. Thus, theory either implicitly or explicitly plays a determining role in the empirical research program and in the results generated. As one scholar remarks: “We need to be honest about the fact that theory plays a disturbingly large part in informing discussion about the impact of unemployment insurance on the labour market” (Manning 1998, p. 145). Using a flawed theory can therefore generate inaccurate and misleading empirical results which in turn can impact on public policy.

I find that in terms of theory, the negative conventional view of voluntary search unemployment holds only in the short run, at best. A dynamic modeling of the problem suggests a potential negative impact of unemployment insurance on voluntary search unemployment. In other words, unemployment insurance can be expected to reduce the rate of quits and dismissals in the long run even if it increases the length of time devoted to job search in the short run. Moreover, the related analytical prediction that individuals quit their jobs as a consequence of unemployment insurance also hinges upon the assumption that individuals have an unbending preference for leisure. However, when demand for employment is driven largely by an individual’s target income rather than leisure-seeking behavior, the latter analytical prediction loses much of its theoretical weight and precision. In addition, a behavioral modeling of the firm suggests that higher wage rates induced by unemployment insurance need not cause more unemployment and higher production costs in the long run. This follows if such higher wage rates positively affect efficiency and technological change. Under these more realistic alternative assumptions, there is no reason to expect that unemployment insurance will yield a less competitive economy with higher rates of unemployment. Indeed, unemployment insurance can serve to reduce the long- run unemployment rate as well as to increase firm efficiency even from a strictly narrow microeconomic perspective, which abstracts from the institutional parameters within which unemployment insurance is configured and applied.

An empirical context to the debate

The questions raised in this chapter should be placed in the context of existing empirical studies for developed market economies which largely suggest that unemployment insurance has little net impact on the rate of unemployment (Burtless 1987; Atkinson and Micklewright 1991; Blank 1994; Card and Freeman 1994). For example, Atkinson and Micklewright conclude from a survey of the literature on the empirical relationship between unemployment insurance and unemployment in OECD countries, based on conventional theoretical assumptions:

As far as policy is concerned, unemployment benefit has not had a good press in recent years, with stress being placed on its negative effects on employment and the labor market operation. Our review of the evidence leads us to conclude that there may be adverse effects on the incentive for the unemployed to leave unemployment but that these are typically found to be small and that there is little ground for believing that much voluntary quitting is induced by the unemployment insurance system.

(1991, p. 1722)

In an earlier more detailed analysis covering fewer countries, Burtless (1987) concludes:

A simple model linking generous unemployment pay to high joblessness must clearly be rejected. For two decades jobless benefits have been less generous in the United States than in Europe, as measured by typical replacement rates and the percentage of unemployed receiving payments. . . . Yet for most of the past twenty years, unemployment has been higher in the United States than Europe. In more recent years, Sweden has enjoyed low unemployment despite offering very generous income support to the unemployed. Furthermore, the trends in joblessness within individual countries do not correspond well to trends in the generosity of benefits.

(p. 153)

Examining 1985–1990 data for the OECD family of nations, Schmid (1995) finds:

Common sense would suggest that the more a country spends per unemployed, the higher the unemployment rate would be. The reason is that higher payment levels will induce people to stay on the unemployment rolls longer. However, this assumption is not supported by a cross-sectional comparison of countries . .. there is virtually no correlation between the level of unemployment and the generosity of the payment systems.

(p. 83)

In a more recent study Strom (1998) argues that:

Neither microeconometric nor macroeconometric results give strong and/or convincing support to the predictions of a strong positive relationship between unemployment and unemployment insurance as indicated in microeconomic and macroeconomic theory. Moreover, there is no strong support for the strong beliefs, held by many economists and others, of a strong positive relationship between unemployment benefits and duration of unemployment.

(pp. 151–152)

It should also be noted that one potential cost of unemployment insurance is the cost incurred by the firm when it is obliged to finance a portion of the unemployment insurance premium. However, although unemployment insurance is often financed out of payroll taxes, the evidence strongly suggests that this has little effect on employment since workers tend to regard the expected insurance benefits as part of their pay package, thus allowing their wages to be adjusted in a manner that offsets any negative employment effect which such taxes might otherwise have had. This is especially true when payroll taxes are experience rated—assessed on the basis of average firm specific unemployment. Thus, if payroll taxes yield an inward shift in the demand curve for labor, a fall in wages yields an offsetting effect. This theoretical proposition has strong empirical backing (Hamermesh and Rees 1988, pp. 171–172, 219–221), and is consistent with the evidence that unemployment insurance tends to have limited, if any negative effects on the economy.1

Overall, although there are studies which do suggest that unemployment insurance, on average, might negatively impact on the economy, these results tend to be weak and far from conclusive or definitive.2 It is critically important for economic theory to explain such seemingly counterintuitive stylized facts.

It is also of importance to recognize the demand-side effects of unemployment insurance. There is strong evidence suggesting that unemployment insurance plays a key role in narrowing the peak–trough cyclical range of unemployment rates through its role as an automatic stabilizer (Sheffrin 1988; Altman 1992c; Stokes 1995; Bougrine and Seccareccia 1999). But there is little evidence to suggest that the demand-side effect of unemployment insurance reduces the trend unemployment rate, which is the focus of much of the debate on unemployment insurance. Nevertheless, in a world without unemployment insurance, irrespective of its supply-side effect, there would be many more people unemployed during the trough of the business cycle. And this would be one of the costs of eliminating or weakening unemployment insurance, absent any countervailing measures taken on the demand side.

There remains a further dimension to unemployment insurance that goes largely unmentioned in the debate. This relates to its safety net effect. If individuals lose their jobs, and there exists no unemployment insurance, the income of the newly unemployed drop to the level of their nonlabor income. This income cushion typically does not compensate for lost income especially as unemployment duration increases. Without unemployment insurance, the unemployed would be even more hard pressed to meet current financial obligations resulting in the liquidation of assets (including the loss of homes or the deterioration of rental accommodations) and savings, reduction in food consumption, health expenditures, and educational investments, and the like. Unemployment insurance reduces the probability that unemployment will impose such significant long-run social costs on the unemployed, which are often a consequence of short- run economic events. Thus, one cost of reducing or eliminating unemployment insurance is the social costs experienced by the families of the unemployed due to the loss of employment income. Another cost generated by the reduction or elimination of unemployment insurance is the depletion of human capital stock (inclusive of psychological dimensions) that is incurred by the income loss due to unemployment. As J.M. Clark (1923) argued, there are constant or overhead costs incurred in maintaining labor’s human capital stock whether or not labor is employed, similar to those incurred with regards to capital. But once labor is unemployed these costs are external to the firm. Unemployment insurance is a means of covering these costs thus preventing the depletion of human capital stock, which represents a social cost.3

It is important to note that the empirical results referred to above are built on models derived from conventional theory, which ignores the potential offsets to any negative effects which unemployment insurance might otherwise have on the economy. This is apart from such models typically abstracting from the institutional detail of particular unemployment insurance programs, where the latter often plays a determining role in structuring the incentive effects of unemployment insurance. Finally, any positive relationship between unemployment insurance and unemployment need not be a causal one. An increase in unemployment might be independent of any contiguous increase in benefits. Indeed, it is always possible that improvements in benefits follow increases in unemployment (Holmlund 1998; Manning 1998; Strom 1998). Given the conventional theoretical wisdom, some may doubt the validity or the robustness of such contrary empirical findings and search for evidence that unemployment insurance has not been effectively employed, thereby explaining the absence of any strong negative impact of unemployment insurance on employment. On the other hand, the empirical literature raises questions as to the validity of the conventional economic theory as it relates to an analysis of unemployment insurance. Can economic theory be rigorously reconfigured or amended so as to better explain the stylized facts specific to the relationship between unemployment insurance and unemployment? I argue below that such a reconfiguration is possible and necessary and carries with it important implications for economic analysis and public policy.

What is the long-run unemployment rate?

Any theoretical discussion of the relationship between the long-run or trend unemployment rate and unemployment insurance requires a clear understanding and definition of the components of the unemployment rate. The unemployment rate is defined as the number of individuals who are unemployed divided by the number of people who are employed plus those who are unemployed. The unemployment rate is therefore affected by the determinants of the flow of individuals into the ranks of the unemployed either through layoffs or job quits and through the entry of individuals outside the labor market into the labor market in search of work. The rate of unemployment is also affected by the flow of individuals into the ranks of the employed. A key question for this chapter relates to the purported impact of unemployment insurance upon these labor flows. Individuals who are not in the labor force, voluntarily or involuntarily, for whatever reason, are not part of the unemployment rate calculation. The rate of unemployment can be expressed as:

where U is the number of unemployed and E is the number of employed per unit of time respectively. U + E equal the labor force. From the perspective of the conventional theory, the flows into U and E depend in part upon the level and duration of unemployment insurance.

The rate of unemployment is not simply a product of the number of individuals counted as being unemployed and employed. It is also a function of the duration of the unemployment spell. Ceteris paribus, the lengthier the spell, the higher is the measured rate of unemployment. The conventional theory assumes that U is positively affected by unemployment insurance through its positive impact upon the search period of the unemployed. The latter point is important and the technicalities of it should be clarified if one is to critically assess the conventional view of unemployment insurance. But it is also important to note is that the duration of employment is, implicitly, also an important variable in the unemployment rate equation. The conventional modeling simply assumes that unemployment insurance has no effect on employment duration. But it is possible for unemployment insurance to positively affect employment duration. With this point in mind, equation (14.1) is modified to incorporate the duration of unemployment and employment, where the modified equation refers to the average annual rate of unemployment:

DU and DE are the duration coefficients for unemployment and employment respectively. These coefficients can be interpreted as index numbers that change in the direction of unemployment and employment duration. It is clear that, ceteris paribus, any increase in DU increases the rate of unemployment. Thus, if the currently unemployed spend more time unemployed searching for a job as a consequence of unemployment insurance or improvements in benefits, which is what the conventional wisdom assumes, the rate of unemployment will increase. On the other hand, if employment duration increases, ceteris paribus, the rate of unemployment falls. This latter point, ignored in the literature, is of considerable importance since if unemployment insurance positively affects employment duration, this effect potentially neutralizes the positive effect which unemployment insurance is assumed to have upon unemployment duration.

To the extent that employment duration increases to the same extent (percentage wise) as unemployment duration, there is no increase in the rate of unemployment. Even if rational unemployed agents choose to invest more time in job search as unemployment insurance increases, if these efforts yield employment of longer duration through locating jobs which better fit their needs, desires, and qualifications, the long term effect of unemployment insurance on the unemployment rate might be zero. It is also possible for the employment duration effect to outweigh the unemployment duration effect, yielding lower long term unemployment rates as a consequence of improvements in unemployment benefits. The potential impact of improvements in employment duration on the long-run rate of employment is ignored in theoretical literature and as a consequence in the empirical literature. But the evidence suggests that unemployment insurance serves to increase the duration employment (Schmid 1995).

Another important technical issue that needs addressing is the distinction between trend or structural unemployment and cyclical unemployment. The literature is largely focused on determining the impact of unemployment insurance on the trend unemployment rate, which abstracts from cyclical factors. It is, therefore, important not to confuse cyclical movements in the unemployment rate with trend changes when attempting to determine the impact of unemployment insurance regime changes upon the trend unemployment rate. If there is an improvement in the unemployment insurance regime and this coincides with a trend increase in the unemployment rate, one can argue that unemployment insurance might have generated an increase in the trend unemployment rate. Of course, even in this scenario, other variables might be the ultimate cause of the trend change in the unemployment rate. If, on the other hand, this increase in unemployment insurance coincides with a peak to trough increase in the unemployment rate one cannot argue that improved unemployment insurance benefits caused more unemployment. Moreover, if a reduction in unemployment benefits coincides with a trough to peak reduction in the unemployment rate one cannot argue that this change in the unemployment insurance regime reduced the unemployment rate.

Search unemployment

According to the conventional theory, the duration and extent of search behavior are expected to be affected by unemployment insurance by influencing the behavior of the already unemployed, the currently employed, and those individuals currently out of the labor force. With respect to those individuals already unemployed, it is assumed that the duration of search activity is increased as the duration and level of unemployment benefits increase. This is a product of the predicted direct impact of these benefits on search behavior and on the predicted impact of these same benefits on the consumption of leisure time on the part of the unemployed.

Underlying search theory is the assumption of imperfect information (Stigler 1962) with regards to the availability of jobs, job characteristics including wage rates, and the location of jobs. If information was perfect the duration of job search would approach zero. Given imperfect information, job search takes time and can be affected by unemployment insurance if there is some variation in job types given the capabilities of the job searchers. If all available jobs as per the capabilities of individual job searchers are identical, there is zero variation in relevant job types, and search time would also approach zero, but will be positive and contingent upon the time required to locate the first job offer which will be accepted given that any future job offers will be identical to the first job offers. In this case, unemployment insurance cannot affect the duration of job search.

According to the traditional literature, in a world of imperfect information and variation in jobs and related job characteristics, the typical rational individual will search for a job such that his or her utility is maximized, where utility is typically defined in terms of the material benefits and costs generated through the job search process. Utility is maximized when the net expected present value of benefits of a job search is maximized. The job search process is stopped once the marginal expected present value of benefits and costs are equalized. Equalizing the expected present value of marginal costs to benefits is equivalent to the asking or reservation wage of the job searcher (the lowest wage that he or she is willing to accept) equaling the market wage offer. The traditional theory inserts unemployment insurance into this model as a variable that reduces the cost of job search by reducing the opportunity cost of unemployment. Alternatively, unemployment insurance increases the asking wage of the job seeker. This, in turn, increases the optimal duration of job search and, thereby, the rate of unemployment.

The traditional model of job search does not incorporate the notion of target income into the utility function of the job searcher in spite of the fact that the realization of target income can play an important role in the decision making process of the individual or household (Altman 2001c; see Chapter 13). If the job searcher’s utility is maximized by realizing a particular minimum target income today as a consequence, for example, of the desire to meet the basic needs of family members such as for shelter, food, health, and clothing related expenditures, the job searcher can be expected to accept a job offer even if, based on the traditional model, the marginal benefits of engaging in further job search exceed the marginal costs. Where target income is important, the individual, in effect, heavily discounts any expected future income above the income expected to be generated by the current job offer—the individual is characterized by a relatively high rate of time discount.

In this amended version of the traditional model, the heavily discounted expected present value of marginal benefits should equal the expected present value of the marginal costs of job search. Job search can be of a much shorter duration than in the traditional model because of the heavy discounting of the expected marginal benefits of job search when target income matters. In this scenario, when unemployment insurance is introduced into the picture, it need not affect the duration of job search, unless it equals or exceeds target income which is typically not the case for the previously employed given that unemployment insurance only covers a percentage of income loss that is a consequence of unemployment. Clearly the extent to which unemployment insurance affects the extent of job search is determined by the discount rate employed by the unemployed job searcher, which can be influenced by the gap between unemployment insurance payments and target income. However, in the conventional model of labor supply there is no such discount rate that is a product of target income being an argument in the job searcher’s objective function. Thus, the target income approach to “income—leisure choice” suggests a much less significant effect of unemployment insurance upon job search duration.

The impact which unemployment insurance can be expected to have on the duration of job search also depends on the structure of unemployment insurance, such as whether individuals can collect benefits if he or she rejects a “reasonable" job offer. Most unemployment insurance programs disqualify individuals who reject such job offers, whereas economic theory typically assumes that no such penalty exists (Atkinson and Micklewright 1991, p. 1688). In this instance, for reasons of the structure of the unemployment insurance program, the incentives are such that the expected time allocated to job search by the unemployed would be the same in a world with or without unemployment insurance, since the unemployment insurance program is designed only to cushion the income loss resulting from unemployment and not to subsidize job search. In other words, with this rather typical program design, unemployment insurance does not affect the marginal costs of job search and, therefore, does not affect the duration of job search, apart from those instances where the unemployed job searchers can systematically violate the rules of the game.

Given the design of typical unemployment insurance programs, conventional economic theory cannot predict increasing job search related unemployment as a consequence of improvements in unemployment insurance. One should also not expect much if any impact of unemployment insurance on job search related unemployment if minimum target income is important to the objective function of the unemployed job searcher. A priori, economic theory cannot predict a large positive impact of unemployment insurance on the duration of job search of those individuals who are already unemployed.

But even if there was a large positive impact, this cannot easily translate into an increase in the long-run or trend rate of unemployment. As previously discussed, to the extent that longer search duration yields a better match between the job related characteristics of the job searcher and the job characteristics, it may yield longer job duration (Schmid 1995). This longer job duration can serve as a countervail to any short term increase in job search duration. In this instance, more extended job search duration need not generate a higher rate of trend unemployment. Indeed, it is even possible that increased job search duration so increases the efficiency of job search that it yields a lower trend unemployment rate than what is possible with the shorter duration of job search. In this case, unemployment insurance if structured to subsidize job search might have the opposite effect on the unemployment rate from what is predicted in the traditional model, which ignores the potential long term consequences of increasing job search duration in the short term.

Of lesser importance to the debate surrounding unemployment insurance is the question of the impact of unemployment insurance on the job search behavior of the employed. The conventional wisdom predicts employed individuals, on the margin, will quit their jobs so as to engage in more efficient job search. The institutional problem immediately arises that the typical unemployment insurance program is designed to disqualify individuals who engage in voluntary quits or who are fired for just cause. In this case, by definition, unemployment insurance cannot be the cause of individuals quitting their jobs to engage in more effective search. This institutional datum fits the empirics of there being no evidence that unemployment insurance has induced quits geared toward engaging in more efficient search activity (Atkinson and Micklewright 1991). To the extent that unemployment insurance was designed to subsidize search activity, which it is not, the argument developed with regard to the already unemployed would apply here. Unemployment insurance would, in this case, reduce the cost of unemployed job search thereby inducing some voluntary job separations or quits which would, in turn, increase the rate of unemployment. To the extent that this increases the duration of the new jobs, the long term unemployment rate need not be affected. Moreover, to the extent that minimum target income is of importance to the prospective unemployed job searcher, this individual will not quit his or her job if the current job just yields the minimum target income.

Also of peripheral concern to the literature on unemployment insurance is the impact which unemployment insurance has upon inducing individuals into the labor market in search of jobs thereby increasing the rate of unemployment. Individuals are induced into the labor market to obtain a job that the new job searcher, formerly a nonlabor market participant, will quit in due course so as to collect unemployment insurance. There exists no evidence to support this proposition (Strom 1998). Perhaps one reason for this is that, as already mentioned, in terms of the institutional design of unemployment insurance, voluntary job separations or quits or being fired with just cause is enough to warrant disqualification from obtaining unemployment insurance benefits. If unemployment insurance programs were not so structured it is quite possible that on the margin some individuals would be attracted into the job market by the introduction of or increases in unemployment insurance. To what extent this would increase the trend rate of unemployment would depend on the rate of employment absorption of the new entrants and the rate of job quits further down the road. The net result from the point of view of theory is ambiguous; and this result applies only to an unemployment insurance program that does not penalize voluntary job quits. Moreover, from the perspective of traditional economic theory, increasing the supply of labor, ceteris paribus, can be expected to have a negative impact on the wage rate and thus a positive effect on employment. From this perspective, traditional economic theory cannot clearly and unambiguously predict that unemployment insurance will increase the rate of unemployment by drawing individuals into the labor market. Finally, to reiterate, in the real world the incentives embedded in the typical unemployment insurance program cannot be expected to draw individuals into the labor market.

Unemployment insurance and income—leisure choice

Even if unemployment insurance has no effect on job search related unemployment, traditional economic theory predicts that the duration of unemployment and thus the rate of unemployment will increase through the income effect which unemployment insurance is expected to have upon the unemployed individual’s demand for leisure, which is assumed to be a normal good. Following the theory of income–leisure choice, which remains at the core of most economists’ understanding of labor supply, unemployment insurance can be expected to induce quits on the margin and increase the duration of already existing unemployment allowing the unemployed to consume more leisure time. This would, in turn, increase the unemployment rate. But this argument does not hold if unemployment insurance programs do not allow for collection of benefits after quitting one’s job, which is typically the case.

What the theory of income–leisure choice, itself, fails to take into account is that an individual’s labor supply is not simply a function of the wage rate and nonmarket income, such as unemployment insurance. It also critically depends on the target income of the individual (Kaufman 1999; Altman 2001c; see Chapter 13). As discussed above, if an individual’s target income is above what is generated by unemployment insurance, a rational utility maximizing individual will not consume more leisure time as a consequence of the introduction of or increases to unemployment insurance benefits. In the ranking of the hierarchy of needs, the realization of target income has priority over increasing the consumption of leisure time. The income effect with respect to the consumption of leisure time can be realized only once target income is realized. It is therefore possible for unemployment insurance to induce a longer duration of unemployment independent of job search considerations. But this critically depends on the target income of the unemployed.

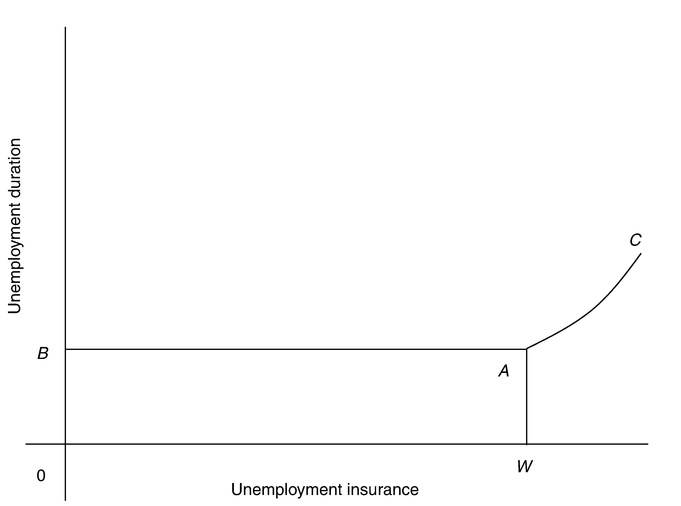

In Figure 14.1, unemployment duration is fixed at B over a wide array of unemployment insurance benefits levels, 0W. Unemployment insurance can be

Figure 14.1 Target income and unemployment duration.

expected to yield increases in unemployment duration when the level of unemployment insurance benefits exceeds an individual’s target income, such as 0W. Moreover, to the extent that target income increases as unemployment insurance increases, increasing the level of unemployment insurance benefits above the traditional target income need not yield increases in unemployment duration. In this modeling of labor supply, labor supply and thus the demand for leisure or nonmarket time is a function of target income in contrast to it being a function of the wage rate and nonwage income as in the traditional neoclassical model (Altman 2001c; see also Chapter 13).4 Unlike in the traditional modeling of labor supply, the target income approach to labor supply, predicated upon more realistic behavioral assumptions, does not predict that nonwage income must generate an increase in the demand for leisure. For this reason, economic theory, per se, cannot unambiguously predict that the introduction of nonmarket income will automatically generate an increase in the demand for leisure and thereby an increase in the trend unemployment rate.

Unemployment insurance, the market wage, and unemployment

A critical point made in the unemployment insurance literature, apart from the discussion on search unemployment, is that unemployment insurance positively affects the market wage thereby increasing production costs and the rate of unemployment. In effect, unemployment insurance provides workers with the means to demand higher wages by strengthening their bargaining power. However, economic theory, per se, provides no insight as to the elasticity of the market wage to unemployment insurance benefits. The increased market wage, by increasing production costs, serves to make the economy less competitive, which underlies the reduction in employment. This point is further illustrated in equation (14.3) where, for simplicity, it is assumed that labor is the only factor input in the production process:

where AC is average cost, w is the wage rate, Q is real output, and L is labor inputs measured by hours worked. Any increase in labor costs is assumed to increase average production costs. Firms experiencing these increased labor costs would be relatively less competitive. Where market wages increase in the same fashion across all firms as a consequence of the introduction or improvements to unemployment insurance, such firms can be expected to lose their competitive edge against economies with less generous unemployment insurance programs. Moreover, firms experiencing unemployment insurance induced higher wages would be able to hire fewer workers even in a closed economy.

The extent to which costs can be expected to increase, in the conventional model, as a consequence of unemployment insurance depends critically on the elasticity of the market wage to unemployment insurance benefits as well as upon the share of wage costs in the total costs of the firm. Equation (14.4) illustrates the latter point:

where dAC is the change in average cost, dw is the change in the wage rate, and NLC is nonlabor costs. If for example, the wage rate is increased

by 10 percent and wage costs w*L represent 100 percent of total costs, average costs increase by 10 percent. However, if wage costs represent only 50 percent of total costs, average costs increase by only 5 percent. In the real world the elasticity of wages to unemployment insurance benefits can be expected to be less than one and the share of wage costs to total costs can be expected to be less than 100 percent. Thus the size effect of unemployment insurance upon production costs is far from clear.

Let’s clarify this narrative with a few numbers. Let’s say that the share of labor to total costs is 50 percent (a pretty high number) and the above elasticity is 10 percent (another pretty high number). In this case, for every 10 percent increase in unemployment insurance benefits, the wage rate goes up by 1 percent. If unemployment insurance benefits increase by 10 percent, average cost would up by only 0.5 percent (50 percent times 1 percent). If unemployment insurance benefits increase by 50 percent, average cost would go up by 2.5 percent (50 percent times 5 percent). Average costs would go up by only 0.25 percent and 1.25 respectively, if the share of labor to costs is 25 percent (a more realistic number).

Whatever the expected increase in market wage as a consequence of unemployment insurance, the prediction that such a wage increase will necessarily increase production costs and reduce employment, is based on the simplifying but not very realistic assumption embedded in the conventional model that the economic agents of the firms are always producing efficiently. Firms are, therefore, operating along their production possibility frontier. This assumption flows from a long tradition in modern economic theory which assumes that the market forces individuals to behave in this manner and, moreover, the self- interest of individuals bent on maximizing material gain only adds weight to the push of market forces toward economic efficiency (Friedman 1953; Reder 1982; McCloskey 1990; Altman 2001c, ch. 3; see also Chapter 2). From equation (14.1), if firms were not being efficient, productivity would be less than it could be and costs would be higher making firms relatively less competitive. Even if individuals happen not to be naturally or socially predisposed toward efficient behavior within the firm, market forces are expected to act as a corrective, at least in the longer run.

The assumption of efficiency in production in the conventional modeling of the firm presumes that individuals always work as hard and as well as they can no matter the circumstances which they face within the firm and no matter the social and cultural milieu in which they are embedded. More specifically, it is assumed that economic agents are maximizing both the quantity and quality of effort inputs into the process of production and, therefore, effort discretion does not exist—workers, managers, or owners, have no choice over how hard or well they work. They are always doing their best by assumption. Harvey Leibenstein refers to this type of efficiency as x-efficiency (see Chapter 2). Given x-efficiency in production, any particular shock to the system, such as an increase in the wage rate induced by unemployment insurance benefits, can only serve to increase production costs, as per equation (14.1).

If economics agents are not efficient from the get go, that is if some effort discretion exists, increasing wage rates need not generate higher average costs (Altman 1992c, 1998, 2003a, 2002; see also Chapter 2). This would be the case if labor productivity increases sufficiently to offset the increase in wages. Unemployment insurance induced increases in wage rates need not generate more unemployment when increasing wage costs are offset by increasing efficiency. If labor is the only input in the production process, labor productivity would have to increase in the same proportion as wages, as per equation (14.1). If, on the other hand, labor is not the only factor input and wage costs do not comprise 100 percent of total costs, labor productivity need only increase by a lesser percentage than the wage increase, as per equation (14.2). To the extent that the assumption of slack in effort inputs is a reasonable one, the prediction that unemployment insurance induced wage increases will necessarily generate higher production cost and lower levels of employment loses much of its analytical weight. This would also be true of the argument that unemployment insurance related costs such as payroll taxes, when not compensated for by anticipated offsetting reductions in wage rates, will generate higher production costs.5

This effort variability based argument extends the work of Leibenstein (1957, 1966, 1979) and Akerlof (1982, 1984), Akerlof and Yellen (1986) and Stiglitz (1987) on x-efficiency and efficiency wage theories respectively which challenge the assumption that effort discretion does not typify the production process. Leibenstein refers to the difference between the level of output produced efficiently (or x-efficiently) and the level of output produced when the quantity and quality of effort inputs are below the maximum as the degree of x-inefficiency. A basic assumption of the behavioral model detailed in Altman (1992b, 1998, 2003a; see also Chapters 2 and 3) is that effort inputs are positively affected by the level of labor compensation, inclusive of wage rates, as well as by the entire package of industrial relations of which labor compensation is but one component. This assumption is a well-documented one as is the fact that firms similar in technology and output type adopt a range of industrial relations structures, ranging from low wage–poor working conditions to high wage–high quality working conditions structures of industrial relations (Altman 2002; Ichniowski et al. 1996). This behavioral modeling of the firm has important implications for an understanding of the potential impact of unemployment insurance on the rate of unemployment.

In this modeling of the firm, unit costs of production need not change at all as labor costs vary, inclusive of unemployment insurance induced costs, as long as effort inputs change just sufficiently to offset changes in labor costs. This is clear from equation (14.1). Also, in Figure 14.2, there is a unique average cost, 0A, consistent with a range of labor costs, inclusive of wage rates up to point W. Up to this point labor productivity can be increased sufficiently to compensate for increases in labor costs.

There is a range of labor costs consistent with firms achieving competitive average costs, such as B. For this reason, a range of unemployment insurance rates is consistent with firms remaining competitive. Only at point W is the firm or firms approaching x-efficiency in production. Beyond point W, effort inputs relative to rates of labor compensation and working conditions enter into the realm of diminishing returns, yielding less than proportional increases in productivity relative to increases in labor compensation. Below point W, the relatively x-inefficient firms can compete on the basis of low wage and poor working conditions whereas high wage firms, where high wages can be a product of more generous unemployment insurance packages, can compete on the basis of relative x-efficiency in production generated by paying and treating workers better. For this reason there can simultaneously exist, even in a highly competitive

Figure 14.2 Average costs and alternative rate of labor compensation.

environment, a multiplicity of firms characterized by a multiplicity of pay rates and working conditions each characterized by different levels of x-efficiency and quality of output. In this model, within a particular range of labor costs, an offsetting relationship between wage rates and working conditions and labor productivity is assumed. This allows for a range of labor costs to be consistent with a unique average cost, as productivity changes offset changes in labor costs. In contrast, in the efficiency wage literature there is only one rate of labor compensation, the efficiency wage, consistent with minimizing average cost. This is given by point W and curve ACC in Figure 14.2.6

To the extent that unemployment insurance positively impacts upon the wage rate, the behavioral model suggests that this need not result in higher production costs contrary to what is predicted in the traditional model. Indeed, higher wages can simply have the effect of inducing more x-efficient production in the firm. Ceteris paribus, an economy with unemployment insurance and, therefore, with higher wage rates, can be expected to be more productive than an economy without unemployment insurance and lower wage rates. From the perspective of an open economy competing with economies characterized by lower levels of unemployment insurance benefits, the behavioral model predicts that the high unemployment insurance economy need not be at a competitive disadvantage to the extent that it can compensate for its relatively higher unemployment insurance induced wage rates with higher levels of x-efficiency. Thus, as unemployment insurance benefits become more generous and extensive and this positively affects the wage rate, the economy so affected need not lose its competitive edge. Moreover, the impact of the wage increase would be Pareto improving in the sense that certain individuals, the wage earners affected by the unemployment insurance related wage hike, are made materially better off without anyone else made worse off.

What is clear from this analysis is that, at a minimum, the conventional model exaggerates the extent to which increasing the market wage reduces the level of employment, by ignoring the x-efficiency effect induced by the increase in the wage rate. The conventional analysis also assumes away the possibility that the x-efficiency effect might suffice to prevent employment from falling at all. In addition, the conventional analysis precludes an analysis of those conditions necessary to generate such an offsetting x-efficiency effect.

This argument assumes no technological change effect induced by increasing wages. In the conventional modeling, technological change is assumed to be exogenous or at least not affected by movements in the wage rate or other factor prices. At best, a change in the wage rate induces firms to choose a more cost efficient factor input mix along the production isoquant and thus does not prevent average cost from rising as wage rates rise. Increasing wages is assumed not to have any causal effect on the position of the isoquant or production function which, strictly defined, is what technological change is all about. In contrast, in a behavioral modeling of technical change developed in detail elsewhere, economic agents respond to increasing labor costs by either developing new technology or adopting known existing technology that becomes cost effective in the context of higher labor costs (Altman 1998, 2003a; see also Chapter 3).

In this model, as labor costs increase, firms engage in technical change, which increases labor productivity by more than it would be by simply raising the capital intensity of production. New technology is developed and adopted so as to keep unit costs from rising in the face of increasing labor costs. Such technical change complements increases in the level of x-efficiency induced by increases in these costs. To the extent that technical change is endogenous, as it is assumed to be in the behavioral model, one can expect that a given level of average costs would be consistent with an even wider array of labor costs than would be the case if one only brought effort discretion into the analytical framework. As illustrated in Figure 14.2, the average production cost curve shifts from BAC to BAD as technology improves as firm decision makers respond to the challenge of increasing labor costs. Therefore, introducing endogenous technological change into the analysis provides firms with an additional degree of freedom with which to respond to the challenge of unemployment insurance induced wage increases. That firms might respond to wage increases through the avenue of technological change further reduces the probability, from a theoretical perspective, that unemployment insurance must be expected to increase the rate of unemployment through its impact on the market wage. Some of the core arguments of the behavioral model can be further illustrated in Figure 14.3

Figure 14.3 The labor market and unemployment insurance.

which models firm level labor demand and supply. The conventional model assumes that any improvement in unemployment insurance shifts inward the market supply curve of labor thereby increasing the price of labor to the firm from W0 to W1, for example, and reducing employment from L0 to L1. But if there is an efficiency effect induced by the increased wage this shifts the demand curve for labor outward (build upon the marginal revenue product of labor) to D1, offsetting the potential negative impact of increasing wages on employment. At the new equilibrium, E*, the wage rate is W1 and employment is restored to L0. Thus unemployment insurance can have a net efficiency and welfare enhancing effect on the economy, depending upon the elasticity of productivity changes to wage changes. But this net efficiency effect is not at the expense of increasing the rate of unemployment.

Conclusion

Conventional economic theory has had a powerful impact on analyses of the economic impact of unemployment insurance both in terms of its analytical predictions and through its effect on the empirical analyses of the subject. Key predictions of the theory are that unemployment insurance negatively impacts the economy through its positive effect on market wages and thereby upon average costs and unemployment; through its positive effect upon search unemployment; and through making unemployment more affordable to individuals with a strong leisure preference amongst potential labor force participants and the currently employed.

These predictions have not obtained strong, if any, support in the empirical literature. Yet, the theoretical predictions of the conventional wisdom still profoundly influence public policy in part for lack of a viable theoretical alternative. These predictions are further sustained by a poor understanding and appreciation of the actual structure of unemployment insurance programs which, in turn, impacts on the labor market incentives generated by unemployment insurance.

The manner in which unemployment insurance programs are typically configured make it unlikely that unemployment insurance would produce more unemployment by inducing increased quit rates or by increasing the labor force participation rate of individuals who simply seek employment so that they can quit their job so as to collect unemployment insurance. Moreover, the theoretical arguments presented in this chapter suggest, at a minimum, that there is no good reason to expect that unemployment insurance should negatively impact the economy to the extent that the conventional wisdom predicts.

Of critical importance is that the analytical predictions of the alternative theoretical framework presented here are consistent with the empirics of unemployment insurance that find, at a minimum, no strong support for the negative narrative flowing from the conventional theories. More specifically, as discussed above, the theoretical propositions presented in this chapter have empirical backing. Even if the duration of search unemployment increases, as unemployment insurance benefits increase, thereby increasing the unemployment rate in the short run, this increased search time makes the search process more efficient thereby increasing the duration of employment, where the latter effect can balance out if not outweigh the short- run effect. Also, to the extent that target income enters into the utility function of the individual there is no good reason to expect that unemployment insurance should induce people to quit their jobs or increase their duration of unemployment so as to increase their leisure time, even if unemployment insurance were structured to provide such individuals with unemployment insurance, which it is not. Finally, to the extent that firms are not perfectly efficient from the get go—the conventional wisdom assumes such perfect efficiency as a working hypothesis—higher wages induced by unemployment insurance need not increase production costs or unemployment. This would be as a consequence of induced countervailing efficiency effects which would also serve to improve the level of material well-being in society, especially that of workers and their families.

From the vantage point of a different and, I believe, a more realistic theoretical light, unemployment insurance should not be simply viewed as a policy instrument which, at best, provides the unemployed with some protection from the vicissitudes of the labor market. Indeed, these specific benefits are typically ignored in the conventional literature. Rather unemployment insurance should be regarded as a vital policy instrument that can potentially contribute toward constructing a more vibrant and efficient labor market and market economy. This suggests that unemployment insurance should not be modeled as it has been, at best as a zero-sum game. Rather, it might be more fruitful to analyze unemployment insurance as a positive- sum game in a dynamic setting where unemployment insurance has both short- and long-run consequences in terms of its impact on search behavior and economic efficiency and technical change.