CHAPTER 7

The Safety Standard

7.0 Introduction

In Chapters 4–6, we explored the logic of controlling pollution at an efficient level. The efficiency approach emphasizes trade-offs—pollution control has opportunity costs that must be weighed against the benefits of environmental protection. This is not, however, the kind of language one hears in everyday discussions of pollution control. Instead, pollution is more generally equated with immoral or even criminal behavior, a practice to be stamped out at all costs. In this chapter, we explore the pros and cons of a safety standard that, as much popular opinion, rejects a benefit–cost approach to making decisions about the “correct” level of pollution.

The safety standard fundamentally springs from fairness rather than efficiency concerns. Recall that the efficiency standard makes no distinction between victims and perpetrators of pollution. Instead, efficiency weighs the dollar impact of pollution on victims’ health against the dollar impact on consumers’ prices and polluters’ profits. Each is considered to have an equal say in the matter, based on the reasoning that, in the long run, most people will benefit as consumers from the larger pie made possible via efficient regulation. Advocates of a safety approach, on the other hand, contend that our society has developed a widespread consensus on the following position: People have a right to protection from unsolicited, significant harm to their immediate environment. Efficiency violates this right and is thus fundamentally unfair.

Curiously, there is also an efficiency argument to be made in favor of relying on safety standards. We know that the efficiency standard requires that the costs and benefits of environmental regulation be carefully measured and weighed. However, as we saw in Chapters 5 and 6, many important benefits of protection are often left out of the benefit–cost analyses because they cannot be measured. Moreover, as discussed in Chapter 11, material growth in our affluent society may primarily feed conspicuous consumption, fueling a rat race that leaves no one better off. If the measured costs of protection are overstated by this rat-race effect, while the benefits are understated because they cannot be quantified, then safe regulation may in reality be subjected to a benefit–cost test. Having said this, however, safety is more often defended in terms of basic rights rather than on efficiency grounds.

7.1 Defining the Right to Safety

There is a saying that the freedom to wave your fist ends where my nose begins. In a similar vein, many Americans believe that the freedom to pollute the environment ends where a human body begins. Preventing positive harm to its citizens is the classic liberal (in modern parlance, libertarian) justification for governmental restraint on the liberties of others. In the extreme, permitting negative externalities that cause discomfort, sickness, or death might be looked upon as the equivalent of permitting the poisoning of the population for material gain.

The safety standard can thus be defended as necessary to protect personal liberty. Viewed in this light, we require that pollution should be reduced to levels that inflict “minimal” harm on people. What constitutes minimal harm is, of course, open to debate. In practice, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) appears to consider risks below 1 in 1 million for large populations to be acceptable or “below regulatory concern.” On the other hand, the EPA and other federal agencies tend to take action against risks greater than 4 in 1,000 for small populations and 3 in 10,000 for large populations. Risks that fall in between are regulated based on an informal balancing of costs against benefits and statutory requirements. Regulators pursuing safety are thus expected to take technological and economic factors into account, but to make continual progress, reducing the damage to the environment and human health to “minimal” levels.1

Based on this real-world experience, for the purposes of this book, we can define safety as a mortality risk level of less than 1 in 1 million; risks greater than 1 in 10,000 are unsafe, and risks in between are up for grabs. (For comparison, police officers bear a risk of about 1 in 10,000 of being killed on the job by a felon.) Cancer risks are the most common health risks that are quantified this way.

Of course, many other health risks besides cancer are associated with pollution, such as impacts on the immune, nervous, and reproductive systems. However, the risks in these areas are much difficult to quantify, and as yet, there is no social consensus, as reflected in a judicial record, about exposure levels. Because noncancerous, nonfatal health risks are not well understood, and because cancer risks can be estimated only with a substantial margin of error, the safety standard can be quite nebulous. As a result, the precise definition of safety must often be determined on a case-by-case basis through the give-and-take of politics. (As we saw in Chapter 4, pinning down the efficient pollution level can be quite difficult as well!)

Despite this uncertainty, however, a safety standard in fact remains the stated goal of much environmental policy. As we explore further in Chapter 13, the basic antipollution laws covering air, water, and land pollution require cleanup to “safe” levels, period. There is no mention of a benefit–cost test in the legislation. Similarly, the international climate agreement calls for nations to prevent “dangerous” disruption of the climate.

Ultimately, however, cost considerations must play a role in the political determination of safe pollution levels. Attainment of “objectively” safe standards in some areas would be prohibitively expensive. Indeed, while U.S. courts have thrown out regulatory standards for safety legislation based solely on benefit–cost analysis, at the same time, they have allowed costs of attainment to be considered as a factor influencing the stringency of regulation. They also have interpreted safe to mean not the absence of any risk, but the absence of “significant” risk. On the other hand, the courts have not allowed costs to be a factor in the determination of significant risk.

Accepting that some danger to human health is inevitable does not require abandoning the safety standard. For example, it is commonly accepted that we have a right to live free from violent behavior on the part of our neighbors. Now this right, as most others, is not enforced absolutely: we are willing to fund the police departments, the court system, the construction of new jails, educational and job programs, and drug rehabilitation centers only to a certain level. Moreover, poor people receive much less protection than wealthy people do. Ultimately, the decision about how much violence to live with is a political one, influenced, but not solely determined, by willingness to pay.

One could characterize this approach as declaring the protection of all individuals from violent crime to be a societal right and then backing away from such a goal on a case-by-case basis in the face of rising cost. This results in a substantially different standard than would determining the police departments’ homicide budget based on a benefit–cost analysis. In particular, the former approach generally results in less violent crime. Returning to environmental concerns, a safety target of a maximum 1 in 1 million cancer risk may not always be economically feasible. But, relaxing a safety standard that is too costly is quite different from adopting an efficiency standard.

In the real world, the safe level will certainly be influenced by the associated sacrifices in consumption. Nevertheless, safety advocates would argue that in the arena of environmental protection, costs are not, and should not be, a dominant factor in people’s decision-making process.

Survey research seems to find widespread support for this claim. Most Americans consistently agree with statements such as “protecting the environment is so important that requirements and standards cannot be too high, and continuing improvements must be made regardless of the costs.”2 This is a strong position. Efficiency proponents suggest that it represents softheaded thinking, and if the remark is taken literally, obviously, it does. But a less harsh interpretation of this survey data is that people feel that, because current levels of pollution significantly affect human health and well-being, cleanup is justified regardless of the cost within the relevant range of possibilities.

To illustrate this, one study asked residents of a community in Nevada about their willingness to accept annual tax credits of $1,000, $3,000, and $5,000 per person in exchange for the siting of a potentially dangerous hazardous waste facility nearby. Contrary to the author’s expectations, increases in the rebate had no measurable impact on approval of the facility. The results were “consistent with a threshold model of choice, whereby individuals refuse to consider compensation if the perceived risk falls in the inadmissible range. For those respondents where the risk was perceived to be too high, the rebates offered were not viewed as inadequate, but as inappropriate…most of the Nevada sample viewed the risks as inherently noncompensable….”3

Behavior such as this suggests that one important benefit of environmental protection—the right not to be victimized—is unmeasurable. Casting this argument in terms of our social welfare function, in the interests of personal liberty, safety advocates place very strong weights on injuries to human health arising from pollution. To illustrate this, let us return to our example in Chapter 4, in which Brittany and Tyler were wrangling over smoking in the office. To a safety advocate, the social welfare function might look like this:

where the weight given to the negative impact of smoke on Brittany is a very big number, one that may well justify banning smoking altogether.4

Should smoking be banned in public places under a safety standard? This is a question for voters and courts to decide. One feature of the safety standard is its imprecision. No right is absolute, as rights often come in conflict with one another, and the political arena is where the issue is ultimately decided. What the safety standard maintains is that, in the absence of a “compelling” argument to the contrary (which may include, but is not limited to, cost of attainment), damage to human health from pollution ought to be minimal. Individuals have a right to be free from the damage that secondary smoke inflicts.

7.2 The Safety Standard: Inefficient

The first objection to the safety standard is that it is, by definition, inefficient. Efficiency advocates make the following normative case against safety: Enshrining environmental health as a “right” involves committing “too many” of our overall social resources to environmental protection.

As a result of pursuing safe levels of pollution, regulators and voters have often chosen pollution-control levels that may be “too high” based on a benefit–cost or efficiency standard. Consider, for example, the air toxics provision of the Clean Air Act Amendments, designed to control the emission of hazardous air pollutants. When the law was passed in 1990, the EPA estimated that at 149 industrial facilities nationwide, cancer risks to the most exposed local residents from airborne toxics were greater than 1 in 10,000; at 45 plants, risks were greater than 1 in 1,000. The law required firms to impose control technology that, it was hoped, would reduce risks to below the 1 in 10,000 level.

While the costs and benefits of the legislation were difficult to pin down precisely, economist Paul Portney estimated that when the program was fully phased in, the total costs would be $6 to $10 billion per year (about $60 to $100 per household). He also estimated that the total benefits would be less than $4 billion per year ($40 per household). Thus, “If these estimates are even close to correct, Congress and the President…[shook hands] on a landmark piece of legislation for which costs may exceed benefits by a substantial margin.”5

In other cases besides air toxics, pursuing safety undoubtedly generates a high degree of inefficiency. For example, consider the EPA’s regulations for landfills mentioned in Application 2.0. In this case, even with the new regulations, just under 10 percent of landfills will still pose what the EPA considers to be a “moderate” health risk for individuals who depend on contaminated groundwater: a greater than 1 in 1,000,000 (but less than 1 in 10,000) increase in the risk of contracting cancer. However, because very few people actually depend on ground water within leaching distance of a landfill, the new regulations were predicted to reduce cancer by only two or three cases over the next 300 years. Potential benefits of the regulation not quantified by the EPA include increased ease of siting landfills, reduced damage to surface water, fairness to future generations, and an overall reduction in waste generation and related “upstream” pollution encouraged by higher disposal costs.

In aggregate, the regulations are expensive: about $5.8 billion or approximately $2 billion per cancer case reduced. On a per household basis, this works out to an annual cost of $4.10 in increased garbage bills over the 20-year life of a landfill. An efficiency proponent would say that it is simply crazy (horribly inefficient) to spend so much money to reduce risk by so little. The $4.10 per year per household is an unjustified tax.

The landfill and air toxics cases both illustrate a more general point: regulations that protect small groups of people from risk will almost always be inefficient, because even relatively high risks will not generate many casualties. Here is a classic situation in which efficiency and fairness (measured as equal risk protection for small and large groups) conflict. Economists, perhaps due to their professional training, are often efficiency advocates, so one will often find economists leveling normative criticisms at safety-based environmental protection laws. Economists are not wrong to level efficiency criticisms at safety standard environmental legislation; in some cases, particularly when marginal benefits of further regulation are very close to zero, the argument may be quite convincing. It is, however, important to remember that economists have no special authority when it comes to proscribing what the appropriate target of pollution control should be.6

Efficiency criticisms of safety are most persuasive when they suggest that an actual improvement in the quality of life of the affected people will result from a move from safety to efficiency. One group of economists, for example, argue: “Since there are a variety of public policy measures, both environmental and otherwise, which are capable of preventing cancer at much lower costs [than the $35 million per life saved from pesticide regulation], we might be able to reduce the cancer rate through a reallocation of resources [i.e., by relaxing pesticide regulations].”7

The problem with this line of reasoning is that the resources freed up from less-stringent pesticide regulation, to the extent they are properly estimated, would reemerge as higher profits for pesticide manufacturers and lower food prices for consumers. They would not likely be channeled into other “public policy measures” to improve environmental health. Thus, only a potential and not an actual Pareto improvement would emerge by relaxing pesticide regulations to achieve efficiency gains.

7.3 The Safety Standard: Not Cost-Effective

The second, and perhaps most telling, criticism leveled at the safety standard is its lack of cost-effectiveness. A cost-effective solution achieves a desired goal at the lowest possible cost. In pollution control, this goal is often defined as “lives saved per dollar spent.” The cost-effectiveness criticism is not that safety is a bad goal per se but that it provides no guidance to ensure that the maximum level of safety is indeed purchased with the available resources. If safety is the only goal of pollution control, then extreme measures may be taken to attack “minimal” risk situations.

For example, the EPA, following its mandate from the Superfund legislation, has attempted to restore the groundwater at toxic spill sites to drinking-level purity. Tens of millions of dollars have been spent on such efforts at a few dozen sites, yet cleanup to this level has proven quite difficult. Marginal costs of cleaning dramatically rise as crews try to achieve close to 100 percent cleanup. Critics have argued that rather than restoring the water to its original safe drinking quality, the goal should be simply to contain the contaminants. EPA’s limited resources could then be redirected to preventing future spills.

More generally, economist Lester Lave points out that children have about a 5 in 1 million chance of contracting lung cancer from attending a school built with asbestos materials. This is dramatically less risky compared to the threat of death from other events in their lives, and Lave suggests that, if our interest is in protecting lives, we would do better by spending money to reduce other risks, such as cancer from exposure to secondary cigarette smoke, auto accidents, or inadequate prenatal nutrition and care.8

A safety proponent might argue in response that devoting more resources to each of the first three problems would be a good idea. And in fact, the limits to dealing with them are not fundamentally limited resources, but rather a lack of political will. More generally, a safety advocate would respond that Lave’s comparison is a false one, as funds freed up from “overcontrol” in the pollution arena are more likely to be devoted to increasing consumption of the relatively affluent than to saving children’s lives. Taxpayers do put a limit on governmental resources for dealing with environmental, traffic safety, and children’s welfare issues. Yet, safety proponents ultimately have more faith in this political allocation of funds than in an allocation based on a benefit–cost test.

That said, it is clear that the politically determined nature of the safety standard can also set it up to fail from a cost-effectiveness perspective. Determining “significant harm” on a case-by-case basis through a political process is a far from perfect mechanism in which money and connections may play as large a part as the will of the electorate regarding environmental protection.

Chapter 12 of this book, which examines the government’s role in environmental policy, also considers measures to correct this kind of government failure. For now, safety proponents can respond only by saying that imperfect as the political process is, voting remains the best mechanism for making decisions about enforcing rights. Moreover, as we have seen, the benefit–cost alternative is certainly not “value-free” and is arguably as subject to influence as the political process itself.

Ultimately, however, given the limited resources available for controlling pollution, safety alone is clearly an inadequate standard for making decisions. Requiring regulatory authorities to ensure a safe environment may lead them to concentrate on eradicating some risks while ignoring others. To deal with this problem, so-called risk–benefit studies can be used to compare the cost-effectiveness of different regulatory options. The common measure used in this approach is lives saved per dollar spent. This kind of cost-effectiveness analysis can be a useful guide to avoid an overcommitment of resources to an intractable problem. However, adopting a cost-effective approach does not mean backing away from safety as a goal. Rather, it implies buying as much safety as possible with the dollars allocated by the political process.

To summarize the previous two sections, critics charge safety standards with two kinds of “irrationality”: (1) inefficiency, or overcommitment of resources to environmental problems; and (2) lack of cost-effectiveness in addressing these problems. Criticism (1) is fundamentally normative and thus is a subject for public debate. In this debate, benefit–cost studies can be useful in pointing out just how inefficient the pursuit of safety might be. Criticism (2), however, does not question the goal of safety. Rather, it suggests that blind pursuit of safety may in fact hinder the efforts to achieve the highest possible level of environmental quality given the available resources.

7.4 The Safety Standard: Environmental Justice or Regressive Impact?

The final objection to a safety standard is based on income equity. Safety standards will generally be more restrictive than efficiency standards; as a result, they lead to greater sacrifice of other goods and services. Quoting efficiency advocate Alan Blinder: “Declaring that people have a ‘right’ to clean air and water sounds noble and high-minded. But how many people would want to exercise that right if the cost were sacrificing a decent level of nutrition or adequate medical care or proper housing?”9

Blinder is worried that a fair number of people will in fact fall below a decent standard of living as a result of overregulation. While such dramatic effects are unlikely, given the level of hunger, poverty, and homelessness in our society, it is possible that stringent environmental standards are something poor people may simply not be able to afford. Suppose that by moving from a safety standard to an efficiency-based standard, we as a country spent $30 billion less on environmental improvement. Would the poor be better off?

The first issue: Who ultimately pays the hypothetical extra $30 billion for pollution control? It does appear that because much pollution is generated in the production of necessities—basic manufactured goods, garbage disposal, food, drinking water, electric power, and transport—the cost of environmental regulation is borne unevenly. In general, pollution control has a regressive impact, meaning that the higher prices of consumer goods induced by regulation take a bigger percentage bite of the income of poor people than of wealthier individuals.

As an example, one study looked at the impact of proposed taxes on global warming pollution. A carbon tax of $70 per ton would increase the expenditures on energy by 11 percent for the bottom 10 percent of households but increase the expenditures by only 5 percent for the top 10 percent of families. At the same time, because they consume so much more, rich people would pay a lot more in absolute terms of the carbon tax: $1,475 versus $215 per person.10 This kind of regressive pattern is fairly typical and extends economy-wide to the general impact of pollution-control measures.

On the other hand, while poor and working-class people may pay a higher proportion of their income, they also generally benefit more from pollution control than the relatively wealthy. In the case of air pollution, for example, urban rather than suburban areas have been the primary beneficiaries of control policies. The effects are further magnified because those in the lower half of the income distribution have a harder time buying their own cleaner environment by way of air and water filters and conditioners, trips to spacious, well-maintained parks, or vacations in the country. Dramatic evidence of unequal exposure to pollution based on income—and also race—came to light in 2015 with the terrible situation in the predominantly African-American and low-income town of Flint, Michigan.11 Due both to budget cutbacks and a loss of local political control over their water supply, Flint’s residents had their drinking water switched by the state government to a source that was so polluted that General Motors would not even use it for industrial purposes in their manufacturing plants. The corrosive water also released high levels of lead from the town’s water pipes, exposing thousands of residents to additional dangerous pollutants. Despite widespread complaints from residents about the quality of their water, officials failed to conduct legally required testing, so residents were exposed to high levels of drinking water contamination for over a year.

This general phenomenon, when communities of color experience higher exposure to pollution than do nonminority groups, is called environmental racism. Activists seeking to rectify such situations, as well as to promote equal environmental protection for low-income people generally, pursue what is called environmental justice.

Another area where there is a clear link between not only income but also race and pollution exposure is in the location of hazardous waste facilities. Table 7.1 reports on recent research exploring the demographics of the neighborhoods surrounding the nation’s 413 hazardous waste facilities. As one moves closer to a facility, the population clearly becomes significantly less wealthy and also much less white. This pattern has also been documented for exposure to toxics from manufacturing plants, air pollution from motor vehicles, and other pollutant pathways. In most studies, race does appear as an important, independent factor explaining pollution exposure.12

TABLE 7.1 Race, Poverty, and Hazardous Waste Facilities

Source: Bullard et al. (2007, Table 7).

| Within 1 km | Between 1 km and 3 km | Between 3 km and 5 km | Beyond 5 km | |

| Percent people of color | 47.70% | 46.10% | 35.70% | 22.20% |

| Percent poverty rate | 20.10% | 18.30% | 16.90% | 12.70% |

| Mean household income | $31,192 | $33,318 | $36,920 | $38,745 |

An important question emerges from this data: do polluting industries locate in poor and minority communities, taking advantage of less effective political resistance and/or cheaper land? Or, do low-income people choose to locate close to hazardous facilities because rents are cheaper there? One analysis specifically looked at five hazardous waste sites in the Southern United States. Researchers found that in the location decision, firms were able to deal with a predominantly white political power structure that was able to disregard the needs of a disenfranchised black majority. A survey of the African-American neighbors of the five toxic facilities revealed substantial majorities who felt that the siting process had not been fair. And in four of the five communities, a clear majority disagreed with the statement that the benefits of the facilities outweighed the costs; the community was split in the fifth case.13

Regardless of the causes, the inequities in pollution exposure are now clearly documented and have been dubbed environmental racism. They have also sparked political engagement demanding stronger enforcement of safety-based laws called the environmental justice movement. As a result, some of the staunchest advocates of strong, safety-based regulations have emerged from low-income and minority communities.

Because poor, working-class, and minority people, relative to their income, both pay more for and receive more from pollution control, it is difficult to evaluate its overall distributive impact. Thus, one cannot conclusively argue whether pollution control imposes net benefits or net costs on the lower half of the income distribution. Nevertheless, in important cases such as a carbon tax to slow down global warming, which would raise the price of necessities, distributional issues need to be weighed carefully. Here, as noted in Chapter 1, economists have recommended that much of the revenue raised from the tax be rebated as tax cuts disproportionately to those in the lower half of the income distribution.

Beyond the issue of distributional effects, efficiency critics of the safety standard correctly point out that the additional costs imposed on society are real. It is certainly possible that the money saved under an efficiency standard could, as Blinder implies it will, be used to fund basic human needs: nutrition, adequate medical care, and housing. However, safety proponents might argue in response that the funds would more likely be funneled into consumption among the middle and upper classes.

The previous three sections have looked at criticisms of the safety standard—inefficiency, potential for cost-ineffectiveness, and the charge of regressive distributional impacts. All have some merit. And insofar as safe regulations are regressive in their net effect, safety advocates lose the moral high ground from the claim that their approach is “fairer” than efficiency. Yet, as we have seen, the alternative efficiency standard is open to its own criticisms. Perhaps, no issue dramatizes the differences between these two standards better than the disposal of hazardous wastes.

7.5 Siting Hazardous Waste Facilities: Safety versus Efficiency

In an infamous internal memorandum to his staff, Lawrence Summers—then chief economist at the World Bank and most recently economic adviser to President Obama—wrote: “Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging more migration of the dirty industries to the [less developed countries]?…I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest-wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that.” The memo, leaked to The Economist magazine, stirred considerable controversy. Brazil’s environment minister, responding to Summers’s blunt analysis, said, “It’s perfectly logical but perfectly insane,” and called for Summers’s dismissal from the Bank.

Summers, in a letter to the magazine, maintained that his provocative statements were quoted out of context. “It is not my view, the World Bank’s view, or that of any sane person that pollution should be encouraged anywhere, or that the dumping of untreated toxic wastes near the homes of poor people is morally or economically defensible. My memo tried to sharpen the debate on important issues by taking as narrow-minded an economic perspective as possible.”14 This “narrow-minded” view is what we have characterized as the efficiency perspective. However, we also know that the efficiency perspective—in this case, trade in waste—can be defended both morally and economically, as it provides an opportunity for making all parties better off. The morality of the trade depends on the degree to which this promise is fulfilled.

Disposing of waste—hazardous, radioactive, or even simple nonhazardous municipal waste—has become an increasingly vexing and expensive problem. Such “locally unwanted land uses” (LULUs) impose negative externality costs on their immediate neighbors, ranging from the potential hazards of exposure to decreased land values, for the benefit of the broader society. This is true even when very expensive protective measures are undertaken to reduce the expected risk. For someone with a waste dump in his or her backyard, an “adequate” margin of safety means zero risk. By definition, communities do not want LULUs for neighbors, and the wealthier (and better organized) the community, the higher the level of safety the community will demand.

Because the benefits to the broader society of having toxic facilities are great, one possible solution to the problem of siting is to “compensate” communities with tax revenues, generated by the facility, which would pay for schools, hospitals, libraries, or sewer systems. Poorer communities, of course, would accept lower compensation levels; thus, to reduce disposal costs, some (including Summers) have argued that government policy should promote this kind of “trade” in LULUs. Should poor communities (or countries) be encouraged to accept dangerous facilities in exchange for dollars? The dumping controversy provides a classic example of the conflict between the efficiency and safety positions on pollution control. Both sides maintain that their policy promotes the overall social welfare.

First, let us consider the logic of the efficiency position. Summers defends his trade-in-toxics stance on two counts. First, if the physical damages arising from pollution rise as it increases, then pollution in cleaner parts of the world will cause less physical damage than comparable discharges in dirty areas. In other words, Summers assumes the standard case of decreasing marginal benefits of cleanup. As he puts it: “I’ve always thought that underpopulated countries in Africa are vastly underpolluted,” relative to Mexico City or Los Angeles.

Summers’s second point is that people “value” a clean environment less in poorer countries. In his words: “The concern over an agent that causes a one-in-a-million change in the odds of prostate cancer is obviously going to be much higher in a country where people survive to get prostate cancer than in a country where the under-five mortality is 200 per thousand.” This difference in priorities shows up in the form of a much lower monetary value placed on all environmental amenities, including reduced risk of death. Thus, trading waste not only reduces the physical damage to the environment but also results in (much) lower dollar damages measured in terms of the fully informed willingness of the community to accept the waste. Firms will be able to dump their waste at a lower cost, even including compensation costs, thus freeing up resources to increase the output and raise the gross global product.

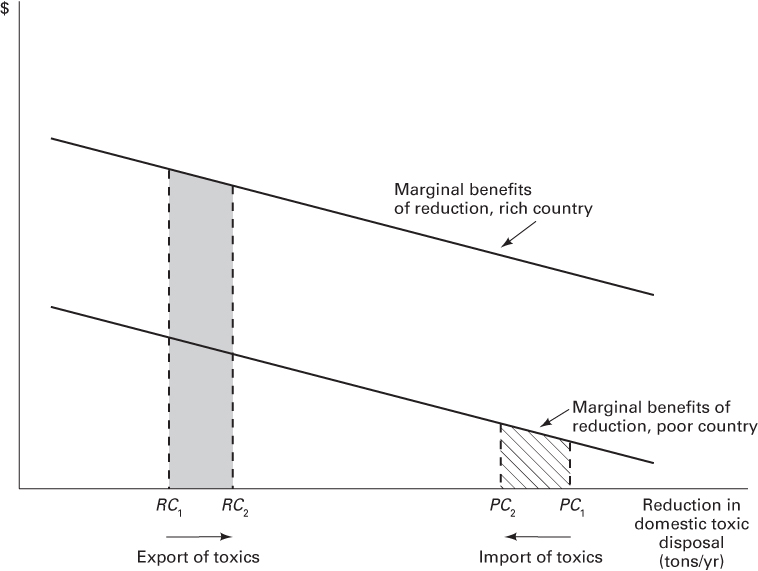

Figure 7.1 presents a graphical analysis of Summers’s position. Due to lower incomes (and lower population densities in some cases), the poor country has a marginal benefit of cleanup schedule lying below that of the rich country. In addition, because current pollution levels are relatively low in the poor country ( versus ), the marginal benefits of cleanup are also low relative to the rich country. Transferring 10 percent of the waste from the rich country to the poor country reduces monetary damages (in the rich country) shown by the shaded area and increases damages (in the poor country) shown by the hatched area. Overall, monetary damages from the pollution have been reduced by the trade.

FIGURE 7.1 Efficiency and Toxic Trade

Clearly, there will be winners and losers in such a process. The winners include those in wealthy countries no longer exposed to the waste, those around the world who can buy products more cheaply if the output is increased, firm managers and stockholders who reap higher profits, and those in the poor countries who obtain relatively high-wage work at the dump sites or benefit from taxes levied against the dumping firms. The losers will be those poor-country individuals—alive today and as yet unborn—who contract cancer or suffer from other diseases contracted from exposure and those who rely on natural resources that may be damaged in the transport and disposal process.

Because dumping toxics is indeed efficient, we know that the total monetary gains to the winners outweigh the total monetary loss to the losers. Thus, in theory, the winners could compensate the losers, and everyone would be made better off. A higher risk of cancer in poor countries from exposure to waste might be offset by reduced risk of death from unsafe drinking water if, for example, revenues from accepting the waste were used to build a sewage treatment facility. In practice, however, complete compensation is unlikely. Thus, as we saw in Chapter 4, toxic dumping—like as any efficient strategy—is not “socially optimal”; it can only be defended on utilitarian grounds if, over time, the great majority of the population benefits from the action. Summers clearly believes that it is in the interests of the people of poor countries themselves to accept toxic wastes.

The first response to this argument: what kind of world do we live in when poor people have to sell their health and the health of their children merely to get clean water to drink? Shouldn’t there be a redistribution of wealth to prevent people from having to make this kind of Faustian bargain? But, an efficiency defender might note that socialist revolution is not a current policy option. Given that rich countries or individuals are not likely to give up their wealth to the poor, who are we to deny poor people an opportunity to improve their welfare through trade, if only marginally?

A more pragmatic response to the Summers argument is that, in fact, most of the benefits from the dumping will flow to the relatively wealthy, and the poor will bear the burden of costs. The postcolonial political structure in many developing countries is far from democratic. In addition, few poor countries have the resources for effective regulation. One could easily imagine waste firms handsomely compensating a few well-placed individuals for access while paying very low taxes and ignoring any existing regulations. In fact, as we noted earlier, a similar process may well explain the racial disparities in toxic site locations in the United States.

The basic criticism of the efficiency perspective is that the potential for a Pareto improvement is an insufficient condition to increase the overall welfare. This is especially apparent in the case of international trade in toxics, where the benefits are likely to accrue to the wealthy in both rich and poor countries while the costs are borne by poor residents of poor countries. By contrast, we expect pollution policy to actually improve the welfare of most of those affected by the pollution itself.

On the other hand, safety proponents face a difficult issue in the siting of LULUs. A politically acceptable definition of safety cannot be worked out, because a small group bears the burden of any positive risk. Nobody wants a LULU in his or her backyard. As a result, compensation will generally play an important role in the siting of hazardous facilities. And firms and governments will tend to seek out poorer communities where compensation packages will be lower. Yet, there are at least two preconditions for ensuring that the great majority of the affected population in fact benefit from the siting. The first of these is a government capable of providing effective regulation. The second is an open political process combined with well-informed, democratic decision-making in the siting process.

The siting of a LULU presents a case in which the important insight of efficiency proponents—that something close to a Pareto improvement is possible—can be implemented. But, to do so requires that the enforceable pollution standard be quite close to safety. It also requires an informed and politically enfranchised population.

7.6 Summary

In the previous four chapters, we have wound our way through a complex forest of arguments to examine two different answers to the question, “How much pollution is too much?” Table 7.2 summarizes their features.

TABLE 7.2 Comparing Efficiency and Safety

| 1. | SOCIAL GOAL | |

| EFFICIENCY: | Marginal benefits equal marginal costs | |

| SAFETY: | Danger to health and environment “minimized” | |

| 2. | IMPLIED SOCIAL WELFARE FUNCTION | |

| EFFICIENCY: | ||

| SAFETY: |

Weights; |

|

| 3. | ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES | |

| EFFICIENCY: | Maximizes measurable net monetary benefits; relies heavily on assumptions of benefit–cost analysis | |

| SAFETY: | Seems to be consistent with public opinion; often cost-ineffective and may be regressive | |

The first standard, efficiency, relies heavily on benefit–cost estimates. In theory, it requires precise calculation of marginal benefits and costs and leads to maximization of the net monetary benefits to be gained from environmental protection. In practice, as we have seen, benefit–cost analysts can only roughly balance benefits and costs. The efficiency standard requires a belief that intangible environmental benefits can be adequately measured and monetized. This in turn sanctions a “technocratic” approach to deciding how much pollution is too much.

By contrast, the safety standard ignores formal benefit–cost comparisons to pursue a health-based target defined by an explicitly political process. In theory, under a safety standard, regulators are directed to achieve as close to a 1 in 1 million cancer risk as they can while also pursuing more nebulous noncancer safety goals, all conditional on the funds allocated to them by the political system. In practice, regulators often back away from safety when faced with high compliance costs.

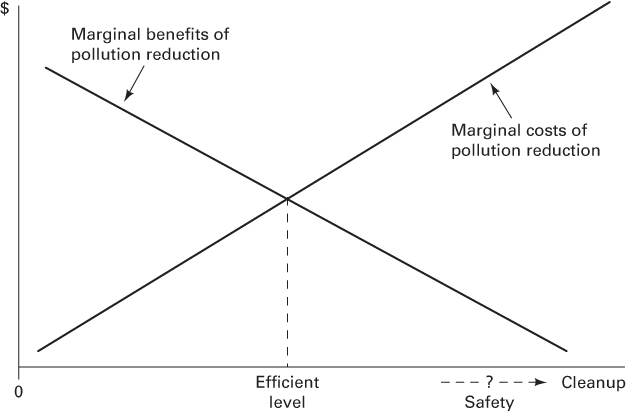

The social welfare function for the safety standard relies on a liberty argument, putting heavy weights on the welfare reduction from pollution. Consequently, as illustrated in Figure 7.2, a stricter pollution standard is called for than is implied by the efficiency standard. Efficiency proponents attack the “fairness” defense of safety with the charge that it is regressive, but this claim is difficult to either verify or refute in general.

FIGURE 7.2 Costs, Benefits, Efficiency, and Safety

One point not highlighted in Table 7.2 is that the choice between the two standards does not affect the long-run employment picture. As discussed in the previous chapter, the more stringent safety standard may result in slightly more short-run structural job loss; yet, it also creates more jobs in the environmental protection industry. The real trade-off is between increased material consumption and increased environmental quality.

Beyond concerns of fairness, the choice between the safety and efficiency standards also depends on a key assumption: more is better. Recall that the underlying premise of benefit–cost analysis is that modern societies are made better off as income and consumption rise. But, what real benefits would we gain from the increased consumption that is sacrificed by tighter environmental controls? If benefit estimates leave out much that is difficult to quantify, or if increased material consumption just feeds a rat race that leaves no one any happier, then safety may be “more efficient” than efficiency! We explore this idea later in the book.

Before that, however, the next three chapters will consider a problem we have so far left off the table: sustainability. How should we incorporate the interests of future generations into environmental protection measures taken today?

KEY IDEAS IN EACH SECTION

- 7.0 This chapter defines and then critically examines a safety standard for pollution control. Safety standards are defended primarily on fairness grounds. However, if unquantified benefits are large and/or the true costs of protection are overstated due to “rat race” effects, then safe regulations may be more efficient than those passing a conventional benefit–cost test.

- 7.1 Safety standards are defended on personal liberty grounds. A political consensus has developed that environmental cancer risks less than 1 in 1 million are considered safe, while risks greater than 1 in 10,000 are generally unsafe. There is no consensus on whether risks lying in between are safe. A precise safety standard cannot yet be defined for noncancer risks or ecosystem protection. In these areas, safe levels are politically determined on a case-by-case basis.

- 7.2 The first criticism of the safety standard is that it is often inefficiently strict. This is a normative criticism and is thus a proper subject for political and moral debate.

- 7.3 The second criticism of the safety standard is that it fails to provide sufficient guidance to ensure cost-effectiveness. Cost-effectiveness is often measured in dollars spent per life saved. If regulators pursue safety at every turn, they may devote too many resources to eradicating small risks while ignoring larger ones. This problem can be alleviated by using risk–benefit analysis. The cost-effectiveness criticism is not that too many resources are being devoted to environmental protection, but rather that these resources are not being wisely spent.

- 7.4 The final criticism of the safety standard is that it might have a regressive impact. While poor people do pay a higher percentage of their income for pollution control than do rich people, the poor, working-class, and minority communities also benefit disproportionately. The greater exposure borne by minorities is referred to as environmental racism, and folks who seek to reduce exposure to pollution in communities of color and low-income communities pursue what is called environmental justice. Thus, the overall impact of environmental regulation on income distribution is uncertain. Moreover, it is not clear that freeing up resources from environmental control would in fact lead to improvement in well-being among the poor.

- 7.5 The siting of a LULU is used to compare and contrast efficiency and safety standards for pollution control. In such a case, efficiency is a difficult standard to implement because it ignores fairness issues. Thus, something similar to a safety standard is generally enforced. If a basic level of “safe” protection is afforded through effective regulation, however, Pareto-improving compensation schemes can result in some movement toward efficient regulation.

REFERENCES

- Blinder, Alan. 1987. Hard heads, soft hearts. New York: Addison-Wesley.

- Boyce, James, and Matthew Riddle. 2008. Cap and dividend: How to curb global warming while promoting income equity. In Twenty-first century macroeconomics: Responding to the climate challenge, ed. Jonathan Harris and Neva Goodwin, 191–222. Cheltenham and Northampton, U.K.: Edward Elgar.

- Bromley, Daniel. 1990. The ideology of efficiency: Searching for a theory of policy analysis. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 19(1): 86–107.

- Bullard, Robert D. 1991. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class and environmental quality. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Bullard, Robert, Paul Mohai, Robin Saha, and Beverly Wright. 2007. Toxic wastes and race at twenty: 1987–2007. Cleveland, OH: United Church of Christ.

- Burtraw, Dallas, Alan Krupnick, Erin Mansur, David Austin, and Deidre Farrell. 1998. Reducing air pollution and acid rain. Contemporary Economic Policy 16(4): 379–400.

- Burnett, Jason, and Robert Hahn. 2006. Drinking water standard for arsenic. AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies. www.aei-brookings.org/admin/authorpdfs/page.php?id = 54.

- Cropper, Maureen L., William N. Evans, Stephen J. Berardi, Marie M. Ducla-Soares, and Paul R. Portney. 1991. The determinants of pesticide regulation: A statistical analysis of EPA decision making. Discussion paper CRM 91-01. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- Flint Water Advisory Task Force. 2016. Final report Flint, MI: Office of the Governor. http://www.michigan.gov/documents/snyder/FWATF_FINAL_REPORT_21March2016_517805_7.pdf

- Goodstein, Eban. 1994. In defense of health-based standards. Ecological Economics 10(3): 189–95.

- Greider, William. 1992. Who will tell the people? The betrayal of American democracy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Kneese, Alan V., and William D. Schulze. 1985. Ethics and environmental economics. In Handbook of natural resource economics. Vol. 1, ed. A. V. Kneese and J. L. Sweeney. New York: Elsevier.

- Kunreuther, Howard, and Douglas Easterling. 1990. Are risk benefit trade-offs possible in siting hazardous facilities? American Economic Review 80(2): 252–56.

- Lave, Lester. 1987. Health and safety risk analyses: Information for better decisions. Science 236: 297.

- Palmer, Karen, and Jhih-Shyang Shih. 2007. The benefits and costs of reducing emissions from the electricity sector. Journal of Environmental Management, 83: 115–130.

- Portney, Paul. 1990. Policy watch: Economics and the Clean Air Act. Journal of Economic Perspectives 4(4): 173–82.

- WSJ Online. 2005. Nearly half of Americans cite “too little” environment regulation. Wall Street Journal, 13 October. http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB112914555511566939.html.