INTRODUCTION

THE EDISON PROPHECY

If the world wages on for many thousand years more, there would seem to be no reason why men should not go on discovering and inventing. No reason to doubt that new tricks and arrangements will be made so that Nature may work to man's advantage. The scientific journals will go on publishing… It is [for] the unreasonable men today to be afraid that they cannot find out any more; that all has been found. Men are just beginning to propose questions and find answers, and we may be sure that no matter what question we ask, so long as it is not against the laws of nature, a solution can be found.1

CORPORATIONS ARE ALWAYS on the lookout for exciting, new, novel, and discontinuous innovations. The light bulb, telephone, automobile, and personal computer are all examples of legally protected technology innovations that have created corporate empires and changed the course of history. In fact, the light bulb and its inventor, Thomas Alva Edison, have become synonymous with innovation. When we think of a bright idea, it is symbolized by a drawing of a light bulb. When we think of prolific inventors, Edison is usually at the top of the list. In today's world, innovation drives corporate profits and competitive advantage. Yet innovation, though key to the real “business” of most companies, has generally been treated as a separate activity.

In many companies, the research and development or “R&D” function, has been literally a “black box.” Inventors—whether engineers, scientists, or web developers—have received special treatment—often keeping odd hours and receiving incentives for their ideas. Innovation has seemed like a magical event—the elusive “Eureka!” resounding at the birth of a new idea. It has been up to the business folks on the other side of the wall—or even in a different building altogether—to shape and refine that idea into a saleable product or service that can generate revenue. Functions such as legal, or marketing, or finance, or strategy have been tasked with creating linkages between ideas and cash flow.

For centuries, companies have linked ideas and money by embedding their new ideas (legally protected or not) into products to be sold or bartered. Today, however, an exciting new concept is revolutionizing the way companies extract value from their ideas: an idea no longer needs to be embedded into a product or service to create value. Today ideas are licensed, sold, or bartered in their raw state for great value. IBM currently receives $1.5 billion in revenue a year from licensing its intellectual property, unrelated to its manufacturing of a single product! More and more companies are intrigued with this notion of turning their legal departments (where intellectual property is housed) from cost centers to profit centers. And an increasing number of pioneers are doing just that.

So how are companies getting value out of their ideas? In a phrase, they are getting value through intellectual property management (IPM). This book describes the unfolding of IPM through a series of true stories—beginning with the story of how the IPM movement began in the first place.

A BRIEF HISTORY

In October 1994, Tom Stewart of Fortune magazine published an influential article on intellectual capital (“IC”), which he defined as the intangible assets of skill, knowledge, and information. In late 1994, ICMG began contacting all the companies who were actively trying to manage their intangible assets. In January 1995, representatives from seven of these companies assembled for a meeting to share what their IC efforts entailed. At that first meeting, the group defined intellectual capital as “knowledge that can be converted to value.” They also determined that IC has two main components: human capital (HC—ideas we have in our heads) and intellectual assets (IA—ideas that have been codified in some manner). Within intellectual assets, there is a subset of ideas that can be legally protected, called intellectual property (IP). (See Exhibit 1.)

The original group of seven companies that met in January 1995 has now grown to over 30 companies from around the world. Members meet three times a year to create, define, and benchmark best practices in the emerging area of ICM. This group is collectively known as the ICM Gathering. The Gathering has spent the past six years working on creating and defining systems and processes for companies to routinely create, identify, and realize value from intellectual assets.

When the principals of ICMG first met with Julie Davis of Andersen, they learned a great deal from each other. ICMG through the Gathering had discovered and tested best practices. For her part, Julie and her Andersen colleagues had developed a framework for organizing and using the best practices. Together, ICMG and Julie had been looking at patterns of behavior that helped to describe some of the activities leading-edge companies used in their quest for better ways to realize value—patterns that came to be known as the Value Hierarchy. Edison in the Boardroom melds these two sets of know-how. Now for the first time, by reading this book, companies can do three things. First, they can identify their current level of activity. Second, they can target the level they want to achieve. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, they can learn directly from other companies what systems and processes they need to put in place to get to their desired level.

WHY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY IS IMPORTANT

IPM guidance is particularly valuable in the current era. Coming up with the “million-dollar idea” seems to be a global pastime these days. We have watched as companies from the new and old economies alike—Dow Chemical and IBM, to name just a couple—have made hundreds of millions of dollars on the basis of their ideas. Now is the time to join them—and our book is here to help.

We feel privileged to have worked in the field of patents over the past 10 years, during the greatest patent boom in U.S. history. We call it a “boom” because in the past full decade (1990–1999), the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has issued more than 1 million patents—or about 100,000 per year. This rate of patent issuance is nearly triple the overall historical rate of patent issuance (36,000 per year on average since 1836). This does not count reissues, which have also grown in number (now numbering some 40,000 in total). In late 1999, the USPTO issued its 6 millionth patent.2

The current patent boom extends beyond the United States—a trend revealed in A Technology Assessment and Forecast Report, a March 1999 USPTO report available at uspto.gov. In 1998, the most recent year for which international data are available, organizations around the world filed a total of 147,520 patents in countries disclosing patent filings.

Of these patents, organizations in the U.S. filed 80,294—a majority, but not an overwhelming one. And of the 67,226 patents with non-U.S. origin, 30,841 were filed by Japanese organizations, and 16,233 by organizations in Germany, France, and the U.K. combined. Organizations in South Korea and Taiwan filed an additional 6,359 (over 3,000 each), and Canadian organizations filed another 1,582. All of these countries have active cultures of innovation in their leading companies.

The global nature of the patent boom also shows itself in a recent study by the Council on Competitiveness, a Washington, D.C. think tank. The Council has created a National Innovation Index, measuring real and projected innovations per million residents. In 1995, the U.S. ranked number one in this index. The Council now foresees the U.S. as number five on the index by 2005, and predicts that Japan will take the primary spot, with the U.S. falling behind to the sixth spot after several smaller nations, including Finland. And year after year, when the USPTO ranks companies most active in seeking U.S. patents, Japanese companies join U.S. firms at the top of the list.

The present rate of growth in patents is likely to continue in the new economy which is based in large part on new technology employed in a global marketplace. Moreover, this intense pace is overtaking the entire realm of intellectual property, including not only patents but also copyrights and trademarks—as well as trade secrets—as described in Exhibit 2.

This jump in the value of patents is being reflected in the bottom line. Corporations define value according to the standards put in place by the accounting profession. In accounting, value is not “accounted for” until it is realized or a transaction has occurred. Yet we all know that in-process R&D—as well as the entire patent portfolio—has immense value to the firm, even though it does not show up on balance sheets. Our view of the world has been shaped by double-entry accounting, which was first created in 1494 by Luca Pacioli, an Italian monk. This is fundamentally the same accounting system that is used by global corporations around the world today to calculate and report revenues, profits, and expenses, and make decisions about resource allocations, risk management, and investment returns. While accounting is very good at recording transactions that have occurred in the past, it is not good at predicting future revenue streams. In addition, accounting only records events and transactions, so financial statements routinely exclude ideas that have not yet manifested themselves in a transaction.

In recent years the percentage of company value attributable to intellectual capital has increased dramatically, according to one prominent source. In a study of thousands of nonfinancial companies over a 20-year period, Dr. Margaret Blair, of the Brookings Institution,4 reported a significant shift in the makeup of company assets, which she measured by comparing market value to book value. She studied all of the nonfinancial publicly traded firms in the Compustat database. In 1978, her study showed that 83 percent of the firms' value was associated with their tangible assets, with 17 percent associated with their intangible assets. By 1998, only 31 percent of the value of the firms studied was attributable to their tangible assets, while a stunning 69 percent was associated with the value of their intangibles.

EXHIBIT 2 Intellectual Property: The Big Three-Plus

Patents. A patent is typically defined as a government grant extended to the owner of an invention (the individual inventor, or an entity that owns the invention) that excludes others from making, using, or selling the invention, and includes the right to license others to make, use, or sell the invention. Patents are protectable under the U.S. Constitution, and under the Patent Cooperation Treaty of 1970, in Title 35 of the U.S. Code. Patent protection can be extended to inventions that are novel (new and original), useful, and not obvious. Some corporations have patentable inventions but choose to protect some of them as trade secrets, rather than filing for a patent.*

Patents may be issued for four general types of inventions/discoveries: compositions of matter, machines, man-made products (including bioengineering), and processing methods (including business processes). To obtain a patent, the inventor must send a detailed description of the invention (among other formalities) to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which employs examiners who review applications. The average time between patent application and issuance is about two years, although the process may be much shorter or longer, depending on the invention.

Under U.S. patent law, patents are issued for a nonrenewable period of 20 years measured from the date of application. Inventors being granted patents in the United States must pay maintenance fees. Federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over disputes involving patents.

Trademarks. A trademark is a name associated with a company, product, or concept, as well as a symbol, picture, sound, or even smell associated with these factors. The mark can already be in use or be one that will be used in the future. A trademark may be part of a trade name, which is the name a company uses to operate its business. Trademarks may be protected by both Federal statute under the Lanham Act, which is part of Section 15 of the U.S. Code, and under a state's statutory and/or common law. Trademark status may be granted to unique names, symbols, and pictures, and also unique building designs, color combinations, packaging, presentation and product styles (called trade dress), and even Internet domain names. Trademark status may also be granted for identification that does not appear to be distinct or unique, but that over time has developed a secondary meaning identifying it with the product or seller.

The owner of a trademark has the exclusive right to use it on the product it was intended to identify and often on related products. Service marks receive the same legal protection as trademarks but are meant to distinguish services rather than products. A trademark is indefinite in duration, so long as the mark continues to be used on or in connection with the goods or services for which it is registered, subject to certain defenses. Federally registered trademarks must be renewed every 10 years. Trademarks are protected under state law, even without federal registration, but registration is recommended. Most states have adopted a version of the Model Trademark Bill and/or the Uniform Deceptive Trade Practices Act.

Copyrights. A copyright is the right of ownership extended to an individual who has written or otherwise created a tangible or intangible work, or to an organization that has paid that individual to do the work while retaining possession of the work. Copyright protection grew out of protection afforded by the U.S. Constitution to “writings.” Subsequent law (U.S. Copyright Act, U.S. Code in Title 17, Section 106) has extended this right to include works in a variety of fields, including architectural design, computer software, graphic arts, motion pictures, sound recordings (for example, on CDs and tapes), and videos. Any type of work may be copyrighted, as long as it is “original,” and in a “tangible medium of expression.” (Computer software, although intangible, is considered a tangible medium.)

A copyright gives the owner exclusive rights to the work, including right of display, distribution, licensing, performance, and reproduction. A copyright may also grant to the owner the exclusive right to produce (or license the production of) derivatives of the work. A copyright lasts for the life of the owner, plus 70 years. “Fair use” of the work is exempt from copyright law. The fairness of use is judged in relation to a number of factors, including the nature of the copyrighted work, purpose of the use, size and substantiality of portion of copyrighted work used in relation to that work as a whole, and potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. Copyrights are protected under both state and federal law, with federal law superseding. A number of organizations promote the protection of intellectual property, including the World Intellectual Property Organization, which covers copyrights, patents, and trademarks.

* A trade secret is “information, including a formula, pattern, compilation, program, device, method, technique, or process” that is kept a secret and that derives value from being kept secret.3 Many states have adopted the Uniform Trade Secrets law to govern this area.

Why do intangibles now account for such a high percentage of company value? Reasons abound, but here are a few of the most pressing causes.

The changing legal environment. In countries around the world, there is a growing awareness of intellectual property rights. In the United States, the creation of the new Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in 1982 has had an immeasurably positive effect on the value of patents, one of the major forms of intangible assets in U.S. firms. The relatively high number of decisions in favor of the holder of intellectual property rights since the court's creation has made patent-holder rights more enforceable and therefore of greater value.6 And around the world, companies are battling the menace of counterfeits with new strategies of prevention, recovery, and lobbying.

Effects of the Internet and information technology. The rapid rise of the Internet in parallel with the exponentially growing capabilities of information technology (computers, communications, and so forth) has effectively moved the industrialized world into a new economic paradigm: the economics of abundance. In the industrial era, tangible assets were the major source of value, and their value depreciated with use. In the “information age,” by contrast, most value comes from information, which increases in value the more people use it.

The leverage of intellectual capital. Intellectual capital is often the “hidden value” within a firm. It involves the firm's knowledge, know-how, relationships, innovations, and structure. It comprises both the firm's tacit and codified knowledge. It is the engine behind a firm's ability to create new products, business processes, and business forms. In addition, intellectual capital can increase exponentially. We notice that companies today are upgrading their products by adding information and capability to them. For example, we often see companies providing more intelligence in the same amount of product volume, or providing the same amount of intelligence in a smaller amount of product volume. Examples of products containing more and more information per unit of volume are: telephones, computers, appliances, children's toys, credit cards with embedded chips, bar codes on retail products, and office copiers that self-diagnose their own operating problems—to name just a few.

THE EDISON MINDSET

The growing emphasis on ideas is not new to the times. Looking back over the last century we see a similar pattern emerging at the end of the nineteenth century. In Thomas Edison's time, the key inventions were related to the airplane, light bulb, telegraph, telephone, and automobile. Today inventions are emerging around the Internet, software, and business processes.

Thomas Edison may have marked a turning point in the history of innovation when he said (as quoted on page 1):

Men are just beginning to propose questions and find answers, and we may be sure that no matter what question we ask, so long as it is not against the laws of nature, a solution can be found.5

The “we” here was no mere rhetorical device, but a new way of thinking. Thomas Edison is often romanticized as a lone inventor—the creator of the light bulb, the motion picture, the microphone, and a myriad of other technologies. Less well known is his invention of the modern research laboratory using teams of inventors.

To be sure, Edison will forever be the very symbol of brainpower. In his lifetime, he would obtain 1,093 patents, including one for the incandescent electric lamp—a prototype of the “light bulb” that would come to symbolize the “bright” idea. Other patents included those for the phonograph, the microphone, and the motion picture projector—technologies that would shape a century.

But despite the brilliance of these inventions, one might well say that Thomas Edison's greatest contribution to society was not any particular invention, but rather the creation of the world's first research laboratories—in fact, two of them, in Menlo Park and West Orange, New Jersey. As one source notes, his workshops were “forerunners of the modern industrial research laboratory, in which teams of workers, rather than a lone inventor, systematically investigate a problem.”6 Edison, more than any other scientist of his day, knew that to generate ideas and successfully commercialize them required sustained and methodical effort. The history of the light bulb proves this point. (See Exhibit 3.)

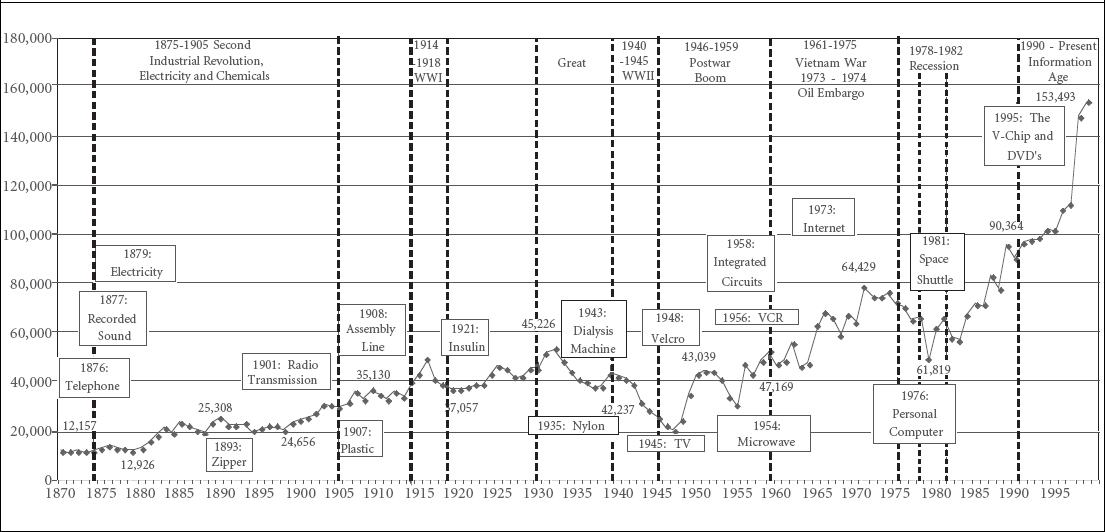

Edison made his optimistic prediction about inventions in 1878, exactly four years before the beginning of a steady rise in patents that would continue for the next 120 years, boosted by innovations in telegraphy, electricity, automobiles, airplanes, synthetics, aerospace, and most recently, high technology including computers, computer software, and the new Internet economy they have spawned (as seen in Exibit 4).

At both our firms, we work with clients who hunger to find new sources of value—but where? Companies have already been reengineered, reorganized, and restructured. Their workforce has been downsized, right-sized, and empowered. Their inventory is just-in-time. Their core competencies have been benchmarked and noncore functions outsourced. And companies have streamlined their factory operations, introduced many quality initiatives, and partnered with suppliers, customers, and communities. There are no more stones to turn—or so they think.

EXHIBIT 3 The Light Bulb: A Brief History

The light bulb may symbolize the quick flash of invention, but it also represents the long, slow process of bringing an idea to the marketplace. Known technically as the incandescent lamp, a light bulb is simply a glass bulb enclosing an electrically heated filament that emits light. As simple as it may sound, this object was very difficult to produce, and had a significant impact on society. Today, light bulbs are one of only two major sources of electric light. The other source, fluorescent light, is generally considered to be inferior for ordinary use.

Before Thomas Edison began working on the light bulb, 20 inventors had similar insights, but nothing significant came of their efforts. For example, in 1802, Humphry Davy passed an electric current through a platinum wire and lit it up, but he did not protect or pursue this invention. In 1845, American J.W. Star received an English patent for a “continuous metallic or carbon conductor intensely heated by the passage of electricity for the purpose of illumination.” Building on Star's invention, Joseph Swann experimented with lamps between 1848 and 1860, but never produced anything practical until 1877, when he renewed his efforts at exactly the same time that Thomas Edison was turning his attention to electricity.

Edison was by far the most persistent of this line of inventors. He experimented with a variety of materials—including mandrake bamboo from Japan— before he finally hit on a solution: the use of a filament made of carbonized cotton sewing thread. Edison patented this procedure, but lost a patent infringement case initiated by Swan. In order to make peace, the two men formed the Edison and Swan United Electric Light Company Limited in 1883. The company acquired several other companies and renamed itself Edison Electric. It eventually merged with another company, renaming itself General Electric, or GE in 1892.

Interestingly, it was a GE scientist who finally made the commercial breakthrough. Irving Langmuir tackled a persistent problem with the light bulb—the tendency of the filament to crumble, and the bulb to blacken, after short use. After three solid years of experimentation, Langmuir solved the problem in GE labs, and won the Nobel Prize for his discovery.7

In our work together, we share the mindset of Thomas Edison. We agree with him that inventiveness will never end, but more important, we agree that it is hard work and perseverance that have fueled this continuing flow of invention. This is a message that companies today can take to heart as they develop, protect, and enhance their intellectual assets day in and day out—for months, for years, and for generations.

The answer for our clients then and now has been a rediscovery of intellectual assets—current and future, legally protected or not. Intellectual assets are codified knowledge, which may or may not be protected by such laws. Know-how, brands, contracts, and architectural drawings are all examples of intellectual assets. Legal protection comes from patent, trademark, and copyright laws, as well as laws protecting trade secrets.

In our joint work with companies around the world, we have developed an appreciation for the best practices in the management of intellectual assets—and how those practices yield results that affect both profits and shareholder value. From working behind the scenes, we know from experience that the real value in intellectual assets lies not only in the inspiration that gives it life, but also in the perspiration that fully develops it and extracts its value. That is why Edison's oft-quoted maxims appeal to us.

Marching in step with Edison, we believe that inventions will continue to stream forth, and that each and every one of them will require hard work to bring into full value. Our own systematic work in investigating the extraction of value from patents (as a prototypical type of intellectual property) has led us to study their “sweat” component—the hard, methodical work of defending ownership, controlling costs, extracting profits, integrating with other aspects of a business, and, finally, mapping out a future strategy. We have identified the best practices of leading companies that relate to the realization of value from their intellectual assets.

We have found, though, that benchmarking best practices without any regard for the underlying culture of the firm can be problematic. For example, many firms want to make money from licensing fees. We have met many IP executives who have been told by their CEOs, “If IBM can make $1.5 billion dollars in royalties, by golly, so can we,” and then in the next breath have also said, “but don't come back here and tell me I need to hire any more lawyers!” The point, of course, is that IBM makes a substantial investment in both R&D and legal resources to generate that royalty stream. Most CEOs are not prepared to make a similar investment. So we realized that it was important for companies to understand where they were in their awareness of IP as a business asset, and to create a way for them to articulate where they want to be, and then identify best practices to allow them to get there.

We call this the “hierarchy of value” for intellectual property (see Exhibit 5)—a model created at Andersen and developed further with ICMG.

THE VALUE HIERARCHY

The Value Hierarchy comes from our study of and work with many companies around the world. From that work we have developed an appreciation for the best practices in the management of intellectual assets, especially intellectual property, and how those practices yield results that affect both profits and shareholder value. The collective learnings of these companies are the foundation for the best practices of this book. But just a raw list of best practices is relatively difficult for companies to integrate into their existing processes and decision systems. And so the Value Hierarchy was born.

Think of the Value Hierarchy as a pyramid with five levels. Each level represents a different expectation that the company has about the contribution that its IP/IA function should be making to the corporate goals. Each higher level on the pyramid represents the increasing demands placed upon the IP function by the executive team and the board of directors. Like building blocks, each higher level relies on the foundation of the lower levels. Mastery of the practices, characteristics, and activities of the prior levels builds the foundation for greater increases in shareholder value. The more one builds on intellectual property on Level One, the better one is able to enhance the value of all intellectual assets—and more broadly, intellectual capital—at the higher levels.

- Level One of the Value Hierarchy is the Defensive Level. If a corporation owns an intellectual asset (such as a great business concept), it can prevent competitors from using the asset. By “staking a claim” on its valuable intellectual assets, a company builds a base from which to obtain more value from them. This is the most fundamental of the IP functions, which is why it is at the base of our pyramid. At this level, the IP function provides a patent shield to protect the company from litigation. By stockpiling patents, companies can not only gain valuable IP, but also shield themselves from litigation because they will be able to negotiate cross-licenses rather than go to court. The IP function of companies involved heavily in this level tends to be run by the company's intellectual property counsel, who often has experience in litigation. (IBM is a rare exception to this rule; its IP function has always been headed by a business person.) Companies at this level generally view IP as a legal asset.

- Level Two is the Cost Control Level, in which companies focus on how to reduce the costs of filing and maintaining their IP portfolios. Well-executed strategies in this area can save the company millions of dollars annually. Companies focusing on this activity may still put the function under the control of a defense-minded attorney, but he or she is more likely to have a background in business. Intellectual property is still viewed primarily as a legal asset.

- Level Three of the Value Hierarchy is the Profit Center Level. Having learned how to control many of their patent-related costs, companies at this level turn their attention to more proactive strategies that can generate millions of dollars of additional revenues while further continuing to trim costs. Passing from the previous levels of activity to this one requires a major change in a company's attitude—and even its organization. In such a company, IP may have its own function, and the individual in charge may even become an IP “czar” as Vice President–IP. It is at this level that companies begin to view IP as a business asset, rather than just a legal asset.

- Level Four is the Integrated Level. In this level the IP function ceases to focus exclusively on self-centered activities and reaches outwardly beyond its own department to serve a greater purpose within the organization as a whole. In essence, its activities are integrated with those of other functions and embedded in the company's day-to-day operations, procedures, and strategies—much as quality programs have been embedded in companies that previously treated them as a separate function. Here the focus is on the process, not just IP. Hence the “process czar” in such a company will often hold a senior vice president title in a broad area such as strategy, information, or R&D.

- Level Five, the final level, is the Visionary Level. Few companies have reached this level of looking outside the company and into the future. In this level, the IP function, having already become deeply ingrained in the company, takes on the challenge of identifying future trends in the industry and consumer preferences. It anticipates technological revolutions and actively seeks to position the corporation as a leader in its field by acquiring or developing the IP that will be necessary to protect the company's margins and market share in the future. The IP function here is often headed by the director of business development or strategic planning—or a similarly future-oriented role.

Few, if any, corporations in the world have mastered all five levels and extracted maximum value from their intellectual assets. Not every corporation needs to do so. But every corporation has room for improvement. Every corporation has an opportunity to increase shareholder value by strengthening and building on its intangible assets.

Keep in mind that each of the levels on this pyramid serves as the foundation or building block for levels above it. Many, if not most, companies may actually be engaging in activities from several different levels. These same companies, though, can benefit by candidly assessing where they stack up compared to others. It is not a “bad” thing to recognize that your company may only be functioning in the bottom levels. It simply means that you have a greater opportunity to really make a difference and influence shareholder value in a noticeable way.

Moving from one level to the next in the Value Hierarchy requires discipline, organization, and leadership. And it requires a road map to avoid the mistakes made by similar organizations in the past. It is important for a company to know the best practices used by other IP leaders, both inside the company's industry as well as in other industries. By mastering all five levels, a company can get the most out of all its intellectual capital—including, perhaps most importantly, its patents.

In this book, we will focus on patents—but we will put them in a broader context. We know full well that intellectual property represents only a small fraction of all of the ideas and innovations of a firm. As mentioned earlier, intellectual capital includes human capital, intellectual assets, and, within that group, intellectual property.

The value hierarchy discussed in this chapter applies to the entire spectrum of intellectual capital, not just the intellectual property. In this book, however, we will focus on intellectual property, especially patents.

Of all types of intellectual property, the quintessential one is the patent. Indeed, it bears the very name of public protection. The term patent derives from litterae patentes, meaning something that is disclosed, rather than secret. By publishing—or rendering “patent”—an invention, the inventor protects his or her rights to it. The patent is also the most common form of intellectual property in most businesses, and as we say, “is the most tangible of the intangibles.” Also, the protection it grants is arguably the strongest.

THE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

To fully understand the Value Hierarchy, one should have a way of viewing the systems used by companies to manage and extract value from their intellectual assets. Such a system can be referred to as the Intellectual Property Management System (IPMS). The following exhibit (Exhibit 6) depicts a generic IPMS as visualized by the Gathering companies.

Although no one company uses a system identical to the one shown below, the Gathering companies have agreed that if they were to start all over again, they would each likely design a system with the components described in the box below. In the chapters to follow, we focus on these components as they relate to the best practices detailed for each level of the Hierarchy. (See Exhibit 7 for further detail.)

Each firm involved in extracting value from its intangible assets inevitably uses a set of activities and decisions similar to that described below. Each such firm tailors the activities and decisions to suit its individual context. In addition to tailoring the activities and decisions involved in the management of the firm's intangible assets, there are also significant issues surrounding how a firm will organize itself to operate and manage this set of decisions and activities.

EXHIBIT 7 The Innovation Process

All firms have their own approach and method for developing new or innovative ideas that create value. For many technology companies the innovation process is an R&D activity; service companies, on the other hand, often have a creativity department; still others rely on their employees in the field to produce innovative ideas. Whatever the firm's source of new innovations, the generic system calls this the innovation process. This process has both decisions (represented by diamonds) and activities (represented by squares).

![]() Patent Criteria and Decision Process

Patent Criteria and Decision Process

Most firms have a method for evaluating the innovative ideas that emerge from the innovation process. Innovations that pass the screening—those that are deemed likely to be useful to the company in pursuit of its strategy—are selected for inclusion in the company's portfolio of intellectual assets. Some companies use the screening process to determine which innovations will be patented; the decision to patent requires an investment of at least $200,000 to obtain and maintain worldwide legal protection for an innovation over its 20-year life. This decision is important for all companies because it separates ideas that are of particular interest to the firm from ideas that, though they may be good and interesting, are not aligned with the firm's strategy. (When a firm decides not to patent, it often maintains an innovation as the know-how of its employees, sometimes formally protecting this knowledge as a trade secret.)

![]() The Intellectual Asset Portfolio

The Intellectual Asset Portfolio

The intellectual asset portfolio is in fact a series of portfolios containing the firm's different kinds of intellectual assets. Some of the portfolios may contain intellectual properties; others may contain documents of potential business interest (e.g., customer lists, price lists, business practices, and internal processes); and others may contain ideas or innovations that are in the portfolio because of their potential to create profits.

![]() Coarse Valuation of Opportunity

Coarse Valuation of Opportunity

Each innovation of potential interest should be “valued” before it is reviewed for use. “Valuation” in this sense is a bifurcated process. The first part of the valuation process is to narratively describe how the intellectual property is expected to bring value to the firm. Following this qualitative valuation, and where it is possible to do so, the firm should attempt to quantify the amount of value it expects the innovation to provide.

![]() A Simple Competitive Assessment

A Simple Competitive Assessment

While competitive assessments in business are commonplace, the competitive assessment contemplated here is one that is focused on the intellectual property of the competitition.

![]() Business Strategy/Tactics/Product-Market Matrix

Business Strategy/Tactics/Product-Market Matrix

This portion of the intellectual property management system involves a review of intellectual properties of interest matched with the firm's business strategy, tactics, and product/market mix. The outcome of this review is an assessment of the fit between this asset and the organization's strategy, and a decision about how to use or dispose of the intellectual property under review.

![]() The Value Extraction Decision Process

The Value Extraction Decision Process

The decision concerning the disposition of reviewed intellectual properties may have several possible outcomes. The intellectual property may be commercialized, used to gain strategic position, or stored until another innovation is developed that makes the first one more marketable.

![]() Assess the Need for New Innovation

Assess the Need for New Innovation

This decision process is invoked where it has been decided that a new innovation should be sought to add to an existing innovation to make the first more marketable. In this case, the question is whether to seek the new innovation from inside or outside the company (through, e.g., in-licensing, acquisition of a company, etc.).

CONCLUSION

We agree with Pat Sullivan of ICMG when he says, “Intellectual capital is the creator of cash flow!” Certainly a firm's market value includes the present value of the future cash flows the firm is expected to generate from its intellectual assets.

So the question really is, how exactly can a company convert its intellectual assets—particularly intellectual property—into the greatest amount of cash over time? As recently as five years ago, we would be hard-pressed to answer that question without resorting to generalities. Today, however, we have a wealth of best-practice knowledge about value extraction.

In our consulting careers we have been privileged to meet individuals who are clearly “ahead of their time” when it comes to realizing value from their companies' innovations and ideas. As mentioned earlier, we have learned much by working with the members of the Gathering. This book is a collection of their learnings, along with success stories of other leading companies we have encountered in our work with clients who were striving to do a better job in leveraging and monetizing their intellectual assets.

Like Edison, these practitioners are at the forefront of this value realization revolution. Many of the individuals we interviewed were tapped by their CEOs to find value—usually cash—in activities previously seen as little more than necessary cost. Many were expected to fail, but most succeeded. Like Thomas Edison the man, and like the companies he founded, the companies in this book uphold the value of sustained, collective effort. It was this kind of effort that would eventually enable Edison to create and realize value from his innovations, showing that the place for value creation and realization is not only the laboratory but also the boardroom.

In the following pages, we will help you use a forward-looking, yet methodical approach worthy of the Man from Menlo Park. For the remainder of this book, we authors, joined by the spirit of Thomas Edison, will travel with you as we build a Value Hierarchy for your company's intellectual property—and, beyond this, all its intellectual assets. So turn the page to take the next step of the journey.