4

LEVEL FOUR—INTEGRATED

COMPANIES THAT HAVE achieved the fourth level have come to understand the strategic implications of intellectual property for their firm. They look beyond defense, costs, and profits. (See Exhibit 4.1.) They realize that IP can be used to position them broadly in their marketplace as well as providing tactical positioning. They also see that IP may be used as an effective weapon against competitors. While profits may be made directly from their IP, companies at Level Four realize there are still greater opportunities. IP is now viewed as an integrated business asset that can be used in a broad range of ways: as a negotiating tool, as a way of positioning the company strategically, or even as a way of affecting stock price.

In addition, the Integrated Level marks a shift in the nature of the IP function. At this level, the IP function starts looking outside its own walls to integrate its expertise and resources with those of the rest of the company. It becomes more innovative and looks for ways to help other parts of the organization reach their goals.

WHAT LEVEL FOUR COMPANIES ARE TRYING TO ACCOMPLISH

Companies at Level Four see their IP as a set of strategic as well as tactical assets. At this level, companies are usually interested in IP as a set of business assets. Their IP management objectives include:

- Extracting strategic value from their IP

- Integrating IP awareness and operations throughout all functions of the company

- Becoming more sophisticated and innovative in managing and extracting value from the firm's IP

With these objectives in mind, Level Four companies are now interested in adding IP to their portfolio so that it can be used more strategically. In part, the selection of what to include in the portfolio is heavily influenced by a more sophisticated and complex understanding of competitor IP strategies and portfolios. As a result, Level Four companies often invest in developing comprehensive IP competitive assessment capabilities.

Whereas Level Three companies are focused on learning the tactical possibilities that IP makes available to them, Level Four companies are more intrigued with the strategic possibilities. By Level Four, companies have come to understand the fundamental importance of knowledge and information to their long-term benefit. With this in mind, Level Four companies begin to change the ways in which they deal with their human capital and tacit knowledge. At this level, company managers realize that they don't own the tacit knowledge of their employees and that they should be finding ways of codifying and developing ownership of this important resource.

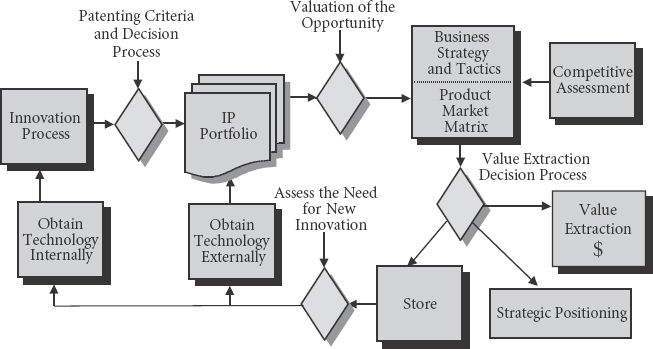

At Level Four, companies are concerned with more than the portions of the IP management decision system that are the province of the IP attorneys (see Exhibit 4.2). IP is now critical to deciphering competitive actions and the firms' reactions as well as finding ways to maneuver strategically in the market. No longer is the firm dependent on its own IP creation, now the company begins actively seeking outside innovations wherever possible in order to save time to market and fill in portfolio gaps. Thus the technical, marketing, and finance functions become more actively involved in the business decisions involving IP.

BEST PRACTICES FOR THE INTEGRATED LEVEL

As in other levels, solutions abound. Exhibit 4.3 contains five best practices for better IP integration in corporations.

Best Practice 1: Align IP Strategy with Corporate Strategy

The basic strategy guiding IP integration can be described in one word: connection.

First, and most fundamentally, there is a connection between IP and the very direction the company is headed. At the risk of overusing the word strategy, we would say that in a company operating at Level Four, the IP strategy must be fully aligned with the corporate strategy. At Level Three, we learned how to monetize intellectual property that already existed in our patent portfolio. The next question is obvious. “What new intellectual property do we want to create?” To answer that question it is important to understand where the company is going strategically and what are its corporate goals, in order to understand the roles that IP can play in enabling those goals.

EXHIBIT 4.3 IP Integration—Best Practices

Best Practice 1: Align IP strategy with corporate strategy.

Best Practice 2: Manage IP and intellectual assets across multiple functions.

Best Practice 3: Conduct competitive assessment.

Best Practice 4: Codify IP knowledge and share it with all business units.

Best Practice 5: Focus on strategic value extraction.

We cannot stress enough that the value of a firm's intellectual property depends not only upon the kind of value desired but also upon the company's context. In fact, we have learned that the company's context provides a new and very useful measuring stick that can be used to determine the relative importance of innovations to the firm or to calculate the value of the firm's intangibles. The value companies place on their innovative ideas largely depends on the firm's view of itself, and on the reality of its marketplace. Put another way, each firm exists within a context that shapes its view of what is or is not of value. Context may be defined as the firm's internal and external realities. Internal realities concern direction, resources, and constraints. They define the firm's strengths and weaknesses as well as its capabilities for competing in its external world. The external realities concern opportunities and threats and focus on the fundamental forces affecting the long-term viability of the industry as well as the immediate opportunities available to the firm.

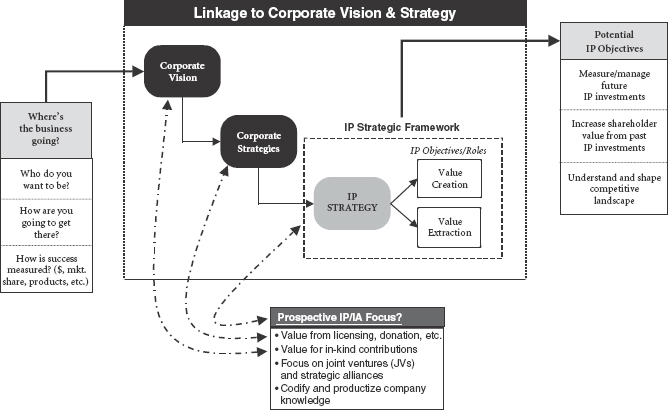

For most firms, their context is expressed through the firm's vision of what it wishes to become and the strategy it selects for achieving that vision. Companies that have defined a vision and outlined the strategy for achieving it, are in a position to now determine the roles their intellectual property can play in leveraging the strategy and in achieving the vision.

Different companies will determine different roles for their intellectual property. Indeed, it is unusual to find two companies with exactly the same roles for their intellectual property simply because no two companies have exactly the same context (vision and strategy). For example, for some product design and manufacturing companies the role for intellectual property may be to create the innovations that will become the firm's products and services of the future. In other manufacturing companies, where the firm's value added involves assembly and integration of components to create products and services, the intellectual property may focus on integrating the innovations of others and adding value through low-cost manufacturing or distribution. In still other companies, the intellectual property may be integral to creating a reputation or image that the company uses to differentiate itself in its marketplace. IBM fits this last profile. It is at its core a technology company. Year after year it ranks number one in U.S. patent acquisition as well as patent and technology licensing. This ranking builds and supports the company's reputation for technology leadership, which in turn adds to the demand for IBM's products and services embodying that technology.

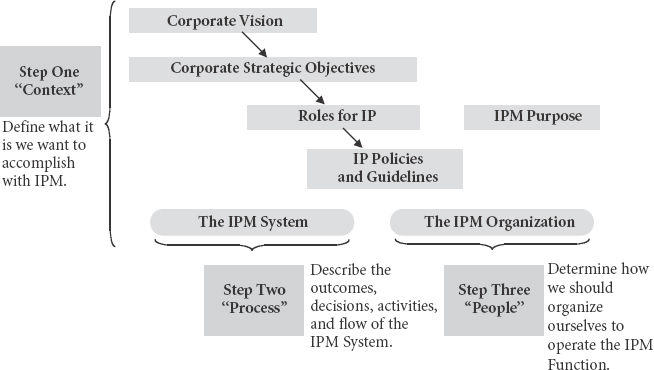

The set of roles any one company selects for its intellectual capital depends largely on the kind of firm it is, its vision for itself, and the strategy it has chosen. The flow of thought for aligning the vision, strategy, and intellectual capital are displayed in Exhibit 4.4.

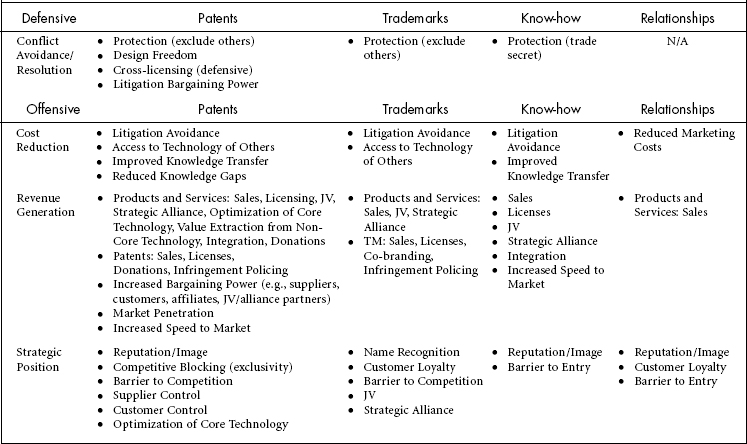

Roles for Intellectual Property. Companies ascribe a range of roles for value extraction from their intellectual property. While most people tend to think quickly of the revenue-generating role, there is a range of others that are employed. Exhibit 4.5 represent some of the most often mentioned ones.

But how do companies actually align their IP strategy and corporate strategies? Joe Daniele discussed how this is done. (See Exhibit 4.6.)

If a company has multiple units, then each unit may have its own unit strategy. The IP strategy for each unit will differ accordingly. SC Johnson operates this way (see Exhibit 4.7).

Few line managers like to create strategy documents. Most of our clients want to leap immediately into actionable things relating to IPM, not create a strategy and align it with the corporate goals. And yet, there is perhaps no other best practice as important as this one. If the IP strategy is not aligned with the corporate strategy and goals, then you will have wasted time, money, and resources. Ad hoc IP systems without a view to the needs of the entire enterprise are likely to fail miserably, as Jim O'Shaughnessy of Rockwell explains:

The day I showed up, we were targeted as a defendant in a number of different patent infringement lawsuits. If you aggregated all of the claims for all of these lawsuits, the financial demands on our company considerably exceeded $1 billion. It's difficult to achieve this kind of result without a nearly total systemic breakdown.

In particular, people throughout the company didn't regard IP very highly in terms of using it as a business tool or lever. There was little connection between the patent department and the business unit. And there was a fairly large disconnect between the patent department and the rest of the law department. Very little articulation of goals and objectives means that common strategies cannot be developed, let alone implemented.

But, beneath the turmoil, we had a lot of people who were very creative. Keep in mind, we pioneered the Space Shuttle program and brought some fantastic technology to American society. But then there was a slip between the lip and cup when it came to capitalizing on the technology as a basis for real competitiveness. It became apparent that we had to transition, and think more strategically.

S.C. Johnson's Bill Frank makes a key point:

It is important to look closely at the relationship between IP and the businesses. IP activities should be aligned with your strategic plan both overall and for each of the businesses within an organization. Accordingly, each business should have its own intellectual property strategy.

Exhibit 4.7 shows our view of the IPM creation context, process, and people.

EXHIBIT 4.6 Aligning Corporate and IP Strategies

How does one develop an intellectual property strategy that is consistent and aligned with the strategy of the corporation so as to support the corporation's goals? First thing you've got to do is know what the corporation's goals are. Where is the corporation going and what is the technical strategy of the corporation, because intellectual property tends to be primarily technical, at least in the sorts of firms we're talking about here. Then you break this technology strategy up into various technical categories in order to reflect what the market is calling for in these various categories. These are technical categories that related to the company's products or services. You want to understand how well aligned your current portfolio is with the products you're looking to deliver over the next five or ten years, because most intellectual property, patents in particular, have a pretty long lifetime. It's around for 20 years. So everything you've got now is going to be supporting the future for roughly the next ten years, (if you take the average life of a portfolio).

It's obviously going to vary if you've been doing something strange like sitting on a portfolio and not doing anything strategic for the last 10 years. For example, if you have a portfolio that is heavily into optics and your future is in digital electronic network areas, you might find that you don't have that close an alignment, in which case you might have a desired state that's pretty high. You might have 2 percent of your portfolio in networks and yet 30 percent or 40 percent of your future products are in networks, just to give an extreme example. You look out five years to your best guess of where your products are going. You lay out what your product strategy is. Then your portfolio should reflect that product and technical strategy.

Next you look at a basic gap analysis. What have you got today? And where do you need to be? You do that in your major product lines. At Xerox when we looked at the technical strategy, there were a number of areas that reflected the technology supporting our products. We did a gap analysis. We looked at what our current portfolio was. We reflected percentage-wise what the portfolio should look like in the future. We included a growth factor assuming we would grow the portfolio at a certain rate per year. Growth of the portfolio is mainly a financial decision because it costs a lot of money to invent, do the filings and maintain the patents. So you need to understand how much you want to spend. It can get very expensive.

In summary, you look at where your portfolio is today, and where you expect to be tomorrow. Then you've got to go out and go into the various technical groups and set goals and targets—and make inventory and filing of patents in specific areas part of their goals for the next year and the next five years.

Joe Daniele, SAIC, formerly of Xerox

The first step is to define the context, determine what it is the company wants to accomplish with IPM. Once you understand what you want to accomplish, then it is helpful to look at where you are today and determine what elements need to be created, reorganized, or redefined. The next step is to create the process that involves describing the activities, decisions, outcomes, and flow of the IPM system. And finally, the last step relates to people, determining how best to organize to achieve the above two objectives. It is at this stage that executives begin to understand how IP connects with every important operating function of the company.

In Exhibit 4.8, Jane Robbins of Sprint Communications Corporation describes how Sprint executives began to understand this.

Best Practice 2: Manage IP and Intellectual Assets Across Multiple Functions

So how can the IP be leveraged across the enterprise? The following discussion shows how this works in a number of areas.

“It all started with candles,” says Jeff Weedman, Vice President of Global Licensing and External Ventures for Procter & Gamble. “That's when we began connecting sciences.” Connecting sciences?

EXHIBIT 4.8 Strategy Link at Sprint

At an important point in our company's history, an inflection point of sorts, we took a critical look inward at our intellectual property management function and asked: How and where does this strategically fit into Sprint? Why does this fit? And why now? At that time, we wanted to find an executive to head up a comprehensive intellectual property management function at Sprint with responsibility across the entire intellectual property value chain—from IP creation/generation to IP protection and maintenance, and IP value extraction. But this wasn't just an HR hiring issue: we first needed restated, actionable, strategic objectives for the intellectual property management function. As well, these restated strategic objectives had to align with and support our larger corporate strategic objectives and underlying vision. Further, these restated strategic objectives had to be linked with a redefined intellectual property role as to value creation and extraction. We wondered whether all of this should be accomplished before we ever hired this executive?

However, we wanted to give the person charged with heading up a redesigned IP management function at Sprint the opportunity to make his or her mark on the function, to mark a course for the future. It was a Catch-22 situation. Also, there were lingering questions about where this person would fit organizationally within Sprint given the multifunctional nature of the position. What kind of reporting relationships would this individual have and how would he or she be linked to the leaders of other impacted organizations at Sprint? We quickly realized we weren't just hiring another vice president in the Law Department with intellectual property authority. We knew the redesigned intellectual property management function would involve our network engineering and planning groups, our tax and finance organizations, our various business development groups, as well as our larger corporate development and strategic planning organization.

Indeed, it didn't take long before we realized that, to move forward, we had to back up from the tactical hiring decision-making. Thus, we first had to broaden our focus to encompass the preliminary strategic planning work. Then, we could propose a redesigned intellectual property management function to enable execution of our reformulated strategic objectives. Finally, with the revised objectives and redesigned function in mind, we could concentrate on hiring the right personnel and best organizing them to realize maximum value from Sprint's intellectual property portfolio. Pursuing this more strategic approach, in our view, would position Sprint to build an intellectual property function and portfolio that best reflects the company we are today and strive to be in the future.

Jane Tishman Robbins, formerly of Sprint

Weedman explains that candles, P&G's original business in 1837, provided the technology base for making soap. “That brought us fundamental expertise in fats and oils, which led to the creation of Crisco shortening.”

Crushing oilseeds gave P&G researchers expertise in plant fibers, which led to insights into paper and absorbent products, like disposable diapers (Pampers) and bathroom tissue (Charmin).

“Fats and oils are also a fundamental base for surfactants, the technology used to produce detergents, like Tide,” Weedman says. “Making detergents, in turn, gave us experience with hard water and calcium. That helped us understand how to improve oral health, through products like Crest, and overall bone health, through products like Actonel, our new prescription drug for preventing and treating osteoporosis.”

Most people may think about P&G as a premier products marketer. “At our core, though, we're a technology company,” Weedman says. “Connecting technologies to create products to better meet consumers' needs is both our history and our future. It's what we're all about.”

Weedman refers to the Swiffer Wet Jet as one of P&G's most recent examples of integrating their IP strategies across multiple functions. (See Exhibit 4.9.)

Research and Development. It goes without saying that the IP function should be linked to R&D. Yet many companies could benefit from strengthening this link. One way to do so is to provide mechanisms to share knowledge across business unit boundaries so that R & D does not have to waste time solving problems already solved elsewhere in the company. This can be done with cross functional and organizational patent committees, interlinked planning processes, or as in the case of Avery Dennison, making the same Director responsible for strategic planning and intellectual property management.

- Avoid spending time and money on projects where IP protection will not be available or, worse yet, where a competitor already holds a blocking patent.

- Monitor competitors' patent filings to provide a window into competitors' strategies and new product developments. A case in point is Avery Dennison. In 1994, one of its units developed a new film that could be used to label products. Procter & Gamble had granted the company a contract to provide the product for its shampoo bottles. But Avery knew that Dow had its eye on this market as well. Rather than compete, sue, and countersue, Avery went to Dow, showed its patent filings, and asked Dow not to enter the market. Dow saw the writing on the wall, and wisely redirected its R&D into other areas.1

- Assist in gap analysis providing insight as to what technologies the company is weak in and how or where it might obtain such technologies without building its own capability. S-3, a small chip design firm, acquired a key patent from Exponential Technologies in order to stall its largest competitor, Intel. The acquired patent predated Intel's Merced chip patent, and could have prevented Intel from using it. S-3 used its patent position to negotiate a lucrative cross-licensing agreement.2

EXHIBIT 4.9 Product Development at P&G

Swiffer WetJet fuses the best of Procter & Gamble's technologies to alleviate one of consumers' most detested chores—mopping. This idea first took shape at the “Seminar of Dreams,” a session which brought together the company's best technologists to “cross-fertilize” many of the company's core competencies. Combining the insight from HomeCare, that the mop can do as much cleaning as the cleaning chemistry we provide to the consumer, with the competency we have in the Paper Division, to create disposable, absorbent cleaning structures, was the seminal moment. From there, Corporate New Ventures picked up the idea, learning that mopping is one of the most despised household tasks, and it has not changed for generations. Corporate New Ventures completed an Attractiveness Assessment in which the consumer, technical, and business model began to take shape. Ultimately, the Fabric & HomeCare GBU took the lead to complete the consumer-technical-business model and then to commercialize this idea as the “Swiffer WetJet.”

The product development required the floor cleaning understanding of the HomeCare group combined with the best technologies of the Paper Divisions—Tissue & Towel, Diapers and Feminine Protection sectors—to make this big idea a reality. The HomeCare group led the consumer research efforts to understand today's habits & practices and to develop the conceptual positioning: “Swiffer WetJet revolutionizes the wet floor cleaning process reducing the time, mess and effort.” To jump start the technical development process, Paper Technologists were actually transferred into the HomeCare organization to lead this work. These technologists were able to design the product from the ground up to best meet the consumer need. The final cleaning pad re-applied some of the best materials and design thinking from Diapers, Tissue-Towel, and Feminine Protection. For example, the pad's super-absorbency is based on the same super-absorbent polymers used in diapers, the stay-clean topsheet re-applies aperture, formed films from FemPro. Meanwhile the cleaning solution was developed, building upon cleaning models and chemistry familiar to the team in HomeCare.

The implement design and sourcing required that we look outside, to learn and to create new competencies. We sought out expertise for the design and manufacturing of the implement, since we had never made such a durable good before. The final implement design uses a battery-powered pump to dispense cleaning solution onto the floor where the absorbent cleaning pad can then remove the dirt from the floor. The design and quality of this implement are best-in-class.

As a result of connecting technologies, along with exceptional marketing and branding strategies, Swiffer WetJet was recognized as one of the most innovative new products in 2000.

Jeff Weedman, Procter & Gamble

“We've been around since 1837,” says Jeff Weedman, Vice President of Global Licensing and External Ventures for Procter & Gamble. “In that time, we've probably made billions of business decisions. But we've made only a handful that have been so visionary, so revolutionary, that they've dramatically changed our company and our culture.”

One of those decisions, Weedman says, was made in 1998. P&G decided to break with its long tradition of holding its patented technologies close—in some cases, even long after the patents themselves had expired.

Instead, P&G adopted a new policy: all of its technologies could be sold or licensed five years after the initial patent was granted or three years after market introduction—whichever comes first.

“This may not seem like such a big deal,” Weedman says. “But, at P&G, it's nothing short of a revolution. Now, instead of locking up our 27,000 patients in a vault, we're making them available to others, even our competitors.”

Weedman says the impact within P&G has been striking. “Suddenly, our R&D community realized that we really do need continuous innovation if we want to stay ahead of competitors. And our commercial folks knew they needed to get our best technologies in the marketplace and around the world fast if they want to maintain a competitive edge. It also made these groups realize that they'd better work closely together.”

As for Weedman's organization: “It created an inventory of valuable technologies unmatched by even the most advanced technology companies. In an instant, it also said, ‘We're open for business.’”

For IBM, a continued emphasis on IPM has created a need for the R&D group to continually innovate to stay ahead of the competition. Fred Boehm and Jerry Rosenthal of IBM elaborate:

We feel IP is the core of our business. We exist because we make great inventions that customers have a need for. We think the heart of any company in this industry is to be making and protecting the inventions they make. We also believe that because of our willingness to license patents to others at reasonable terms, the IT industry has grown to the size it has as fast as it has. We did it earlier than anybody else. There are industries that don't license at all. But in our industry and in our company, licensing provides the challenge for us to stay one step ahead of competition and that is what drives our engineers to do the great things they do.

Finance and Tax. The finance department also benefits from the efforts of a Level Four IP function. Properly handled, IP can also be used to create important tax benefits for the organization, potentially putting millions of dollars into after-tax income. A popular tactic for lessening the tax liabilities associated with licensing revenues has been to create domestic or foreign holding companies for a company's intellectual property and intellectual assets, as Ford Global Technologies Inc. has done. Often it is the finance function of the organization that is best positioned to evaluate the need for IP insurance. Several carriers now offer different products in the two broad areas of “pursuit” insurance and “defense” insurance. Pursuit insurance is offered to companies who wish to cover the out-of-pocket costs associated with enforcing their intellectual property. Defense insurance is offered for those companies who fear that intellectual property infringement actions may be filed against them. In both cases, the insurers conduct a complete evaluation of the risks before taking on the company as an insured. Also, as mentioned in Level Three, a company can use IP donations as charitable contributions to achieve tax savings. Forward-thinking companies are starting to utilize IP information more strategically in M&A transactions, divestitures, and as collateral for borrowings. (See Best Practice 5, on page 119.)

Human Resources. HR benefits from integration with the IP function by building awareness of the technology gaps that need to be filled in the IP portfolio, so that they can be on the lookout to recruit talented scientists or engineers to add to the company's breadth of technical expertise. The HR function also benefits from training about IP for employees throughout the company. Such training is typically designed to familiarize employees with the policies and procedures used to protect corporate trade secrets and codify ideas. The training should also help explain the importance of knowledge so that it is not inadvertently squandered or given to suppliers, customers, or, worse yet, competitors.3

Having an integrated HR function enables identification and retention of key inventors through revised compensation and other award systems. This increased focus on IP by the human resources personnel helps prevent unplanned “brain drain” caused when such inventors are offered early retirement or other severance packages in connection with downsizings or mergers.

The HR function may also be responsible for putting in place programs to motivate and reward new discoveries. Motivational tools include formal “innovation initiatives,” innovation training programs, innovation work groups, and inclusion of innovation in all major aspects of company life, including the company's communication, job design, performance appraisal, and compensation programs. Andersen regularly details these best practices in its annual publication, HR Director.

Marketing. In the marketing arena, companies can generate significant revenue once they understand how to market their intellectual assets to the right buyer. Dave Kline of Litton emphasizes the connection between marketing and IP. He says it goes far beyond mere patent mining:

There is a great deal of focus on the front end of the process, i.e., patent mining. Many managers are caught up in the patent “churning” process, but as with any other business, marketing is the toughest part of this business. Many people in this business have appeared to underestimate this at the start and have had difficulty. Identifying the customer, getting to the right people or organizations and getting them engaged is “where it's at.” The real payback in this goes right back to basic business: how do you find a customer and generate deals?

Alternatively, a company can gather both business and technical information about its competitors to predict future products, markets, and technology platforms planned by competitors—and either get there first or throw a wrench in their plans. Bill Frank, Chief Patent Counsel of S.C. Johnson, uses this external focus as a kind of early alert system.

All of a sudden competitor “x” is starting to pick up patents in your area. This can be a scary or interesting proposition, depending on how you react to it. It is scary if you learn about it too late. It is interesting if you find out about it early through competitive assessment. Of course, competitive assessment is not easy. It is like looking for golden needles in big haystacks. But the effort is worth it—and it is better than hindsight, which is easy but worthless. They are pretty good-sized needles sometimes. You just have to look for them. You can do something about competitive threats if you have a year or two advance warning before a product hits the shelves.

Information Technology. At the integration-minded company, operating at Level Four or above, the information management system (or systems) devoted to IP tend to be more user-friendly because it must be accessible and useful to numerous constituents outside the IP function—including managers, engineers, scientists, and other employees. The system now offers access to information about the company's competitors' products and IP, not just its own. Such access is on an as-needed basis, with careful attention to appropriate security.

The systems used by the Level Three company can be used as the starting point for the Level Four system we are describing here. However, whereas the typical Level Three system would only contain information about the company's own patents and products, the Level Four system would contain further information traditionally considered to be well beyond the scope of a Level Three system. Such information might include data on worldwide markets, products, and related technologies. Also, unlike the Level Three system, the Level Four system likely contains information about competitors' patents, products, and technologies. Such information is particularly useful in a company that emphasizes market share in its corporate strategy.

Having a widely shared IP information system can save time and money. Recently, a division manager of a Fortune 50 company with several thousand patents was asked how his engineers and product development people avoided recreating the wheel in their efforts to develop new technologies. After all, wasn't it possible that their particular problem had been solved previously, somewhere else in the company? His answer was that they had to walk down the hall and inquire, hoping that someone was either around at the time or happened to remember seeing it in the patent portfolio. How many millions of dollars are wasted in today's corporations in an effort to locate what should be readily accessible information?

Rockwell has designed an extensive portfolio database. The database has numerous uses at all levels of the Value Hierarchy (for example, cost reduction), but one important use is the ability of the database to group patents by class of product, and by competitive impact. For details on the database, see Exhibit 4.10.

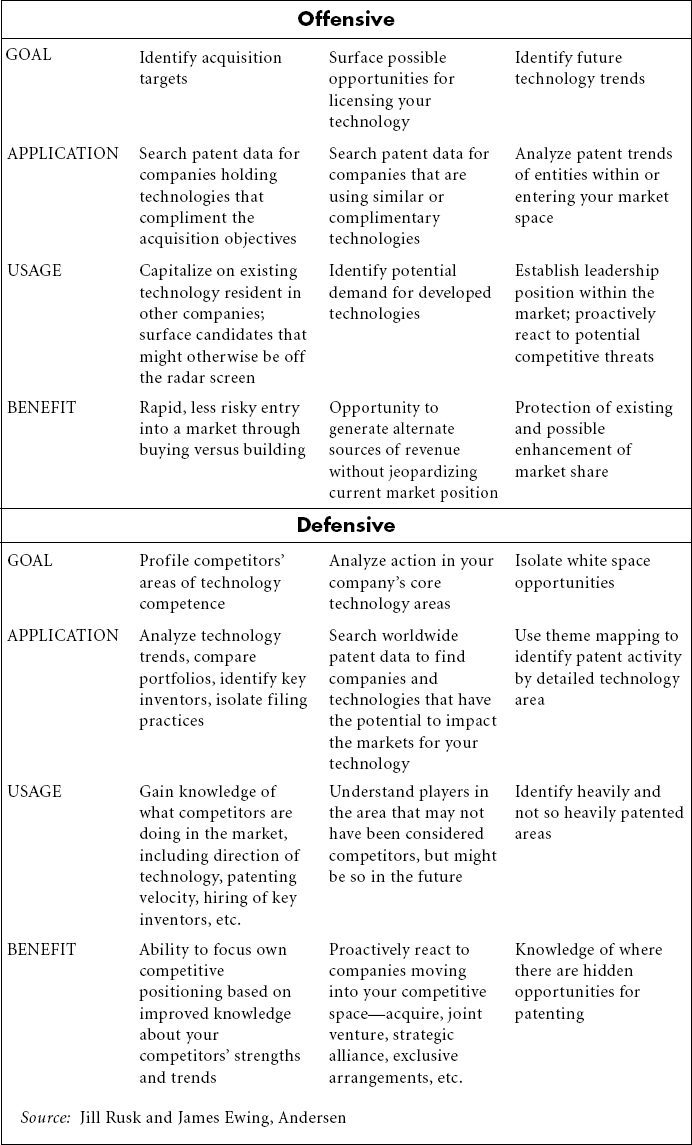

Best Practice 3: Conduct Competitive Assessment

Until now, the company has been focused on an inward view of intellectual property management. How can the company better utilize its existing IP for value? At Level 4, however, the IP focus shifts to an external view: what IP should we create for additional value? Now, the company is focused on looking outward at its current and future competitors to determine where they are currently positioned and where they are likely to move in the future. Once this information is known, the company is in a better position to create and utilize its intellectual assets to stop or preempt a competitor. We call this external viewpoint Competitive Assessment.

Many companies are already practicing competitive intelligence—collecting information about their business competitors. Competitive assessment now adds technology competitors into the mix, because today with the increase of individual inventors and start-ups, technology competitors are more difficult to detect and ignorance of who they are can have devastating results.

EXHIBIT 4.10 Designing an Intellectual Property Data Base— Rockwell's Guidelines

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of developing a database is determining where to start: should the databases be built from existing databases, or should the company make a clean start? Before making this decision begin by focusing on the end uses of the database. Here are the objectives we set forth at Rockwell when we were building our database.

- The database should readily identify patents that have value but that are not being used by the corporation (i.e., good licensing candidates).

- The database should allow its administrators to easily identify nonperforming assets so that they can be sold or abandoned.

- The database should be designed so that it can dynamically reflect and accommodate the strategic direction of the company.

- The database should provide access to the costs associated with maintaining the portfolio and individual assets.

- The database should provide the users with the ability to easily group patents comprising similar technologies.

- Within a technology area, patents should be easily grouped and identified as being fundamental versus iterative in nature.

- Where a particular asset is iterative in nature, it should be easily grouped with patents that are fundamental within the same technology group.

- The database should have a mechanism to allow its users to group patents that might be applied to a particular product or class of products.

- The database should identify competitors and potential competitors for each patent.

- The database should be designed so that it is easily (if not automatically) appended with new information from a variety of sources.

- The database must be designed with hierarchical access control, so that only those with a “need to know” have access to sensitive information.

- Each patent should identify alternatives to itself and the associated costs (advantages and disadvantages) of each.

- The database should be a constantly updated (interactive) source of information on individual assets.

- Procuring the information required for the database must add little or no extra burden to inventors or to their management.

Kelly Hale, Rockwell International. Reprinted with permission from Profiting from Intellectual Capital: Extracting Value from Innovation, by Patrick Sullivan (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998).

Avery Dennison was once precluded from a significant market because it was unable to detect a small technology competitor who was able to patent a key technology first, thereby rendering millions of dollars of R&D useless. Joe Daniele of SAIC notes that this inward focus can be a large problem for many companies:

A big mistake companies make in this area is to overly focus themselves inward and a lot of them do it. They are looking at protecting what they have and may not be aware of what their competition is doing and often they don't know why they are creating these patent rights. They don't know what they will do with them. It is not until companies start looking at what their competitors are doing and what direction they are going that they are playing the patent game the way it should be played.

Exhibit 4.11 highlights many uses for competitive assessment. When thinking defensively, companies want to understand where their competitors are currently strong and where they are likely to move in the future. More importantly, it is important to know where their competitors are currently not inventing, which we call “white space.” One of our clients related a story where an inventor approached the patent attorney and asked him to tell the inventor where to invent: “It would be a whole lot easier if you would just tell me where the white space is so I can focus there.”

When a company is looking to use its IP offensively, competitive assessment can help identify possible targets for IP monetization; determine the technology trajectory of a competitor and determine whether the company or its competitor is likely to patent first; and finally identify in-licensing and M&A opportunities. Dow believes very strongly in competitive assessment and Bruce Story, Intellectual Asset Director for the Dow Polyolefins and Elastomers business group, describes how competitive assessment provided a significant competitive advantage for Dow. (See Exhibit 4.12.)

Best Practice 4: Codify IP Knowledge and Share It with All Business Units

To date this book has been focused on extracting value from IP. However, in order to legally protect an idea, it must first be codified. How do companies determine which knowledge to codify? Lew Platt, former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, once said, “If HP knew what HP knows we would be three times as profitable.” As Daniele of SAIC points out; “Knowledge is continuously created in an organization, and if not sorted and captured in some way, whether by formal or informal processes, or by the nature of groups or organizational dynamics, this knowledge simply dissipates into the ether.”

EXHIBIT 4.12 Competitive Assessment Case Study

I'm the Intellectual Asset Director for the Polyolefins and Elastomers business group, which is one of the largest business groups within Dow. That includes products like polyethylene and polypropylene and SARAN* and a number of other related packaging-type resins. It's a global business with manufacturing and sales and development people in every area of the globe. There are R&D people, as well, in most areas of the globe. The intellectual asset strategy became an integral part of the business strategy from the very beginning of this project. Our strategy has been largely driven by the competitive assessment that we did.

Recently, new catalyst technology has revolutionized this business, and our competitors had a lot of activity in the intellectual property front in this area. So we were going to have to make sure that we also had both intellectual property as well as the right to practice, so that we could commercialize and extract all the value possible from this new technology. Not only Dow but a number of our competitors were racing along the same or a similar development path to come up with these new kinds of catalysts for the polyolefin industry.

We were able to jump ahead of everyone else when we had our first patent and technology published, back in 1989. So it's only been 11 years since the first patent was filed. Now we have hundreds of patents in that field. We have introduced one new product per year for the last eight years, based upon this new technology. In addition, we have formed a billion-dollar joint venture and have licensed this technology to several world-class companies.

That very first patent was filed 14 days before a very similar patent by Exxon was filed. The patented technology is called INSITE*. Now you have to realize that we had spent over twenty years and several hundred million dollars in R&D to create the Insite technology, so I can only imagine that Exxon had a similar development cost, and clearly the design around cost was not insignificant.

For us the key was focusing on intellectual asset management principles and being able to clearly articulate the white space within which we wanted to innovate. By looking outward we had a good sense of who was going where and what they were doing, and that enabled us to craft broad patent protection for INSITE to maximize value for Dow. At Dow the competitive assessment process is a combination of patent and technology information combined with individual knowledge and publicly available information from press releases and articles in the trade press. Being able to collect all of that in one place and being able to analyze it was very, very helpful to us. That process has allowed Dow to develop a pretty significant business.

Bruce Story, Dow

Many people confuse knowledge, information, and data. Karl Eric Sveiby, who has authored numerous books on managing tacit knowledge, explains: “Data when compiled can become information. Information, when combined with experience, becomes knowledge. On their own, data and information do not represent knowledge. It is the internalization of information that turns it into knowledge.” For example, parents always tell children not to play with fire because they will get hurt. Children generally do not understand this warning until they have in fact gotten burned.

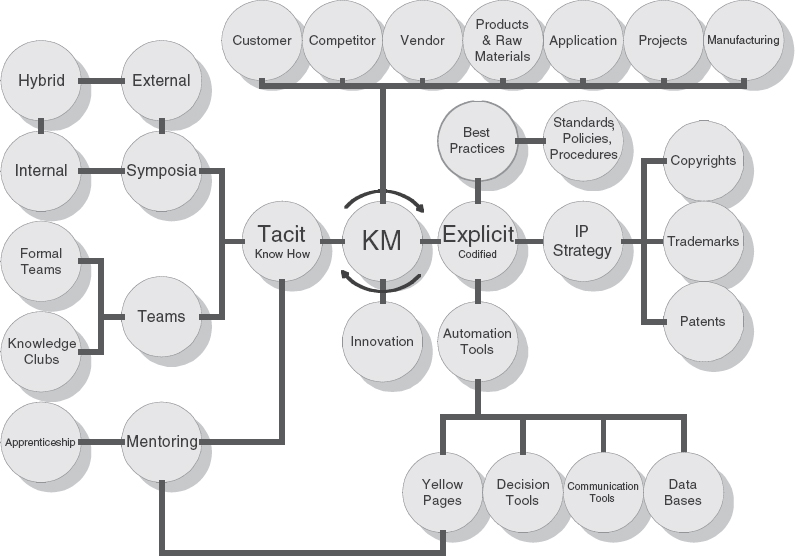

Here experience combined with information generates knowledge. When companies and consultants speak of Knowledge Management, they are talking about the codification of data and information, not of knowledge. H.B. Fuller realized that its employees were knowledge-rich and sought to create a way to capture and leverage that tacit knowledge, as Exhibit 4.13 explains.

An Integrated company will make knowledge about its IP portfolio available to other company functions. In the Level Four culture, knowledge sharing is encouraged. Examples of companies practicing knowledge-sharing abound. Xerox and S.C. Johnson have systems to share knowledge. The Dow Chemical Company, as shown in the case at the back of this book, also provides an example.

H.B. Fuller exemplifies the Integrated practice. If individuals or groups need more knowledge in a particular area, H.B. Fuller encourages apprenticeship and mentoring. It has formal programs for both these activities. It also believes strongly in the value of educational workshops, external, internal, and “hybrid.” In the last case, the company has used a strategy to merge external symposia with internal symposia to create a highly practical learning opportunity. Paul Rothweiler explains:

Like many companies we often send several people from around the world to trade association meetings. While there, Fuller's employees use the opportunity to learn from colleagues from other parts of industry. They also take advantage of having a number of Fuller people together in the same place, who may not normally meet because they work in various parts of the world. This then becomes an opportunity to have an internal symposium right then and there. Sure, they're not within the physical confines of the H.B. Fuller Company, but why should that stop us? We have the opportunity, for no additional cost, to come together at these external symposia and share what we've learned at the symposia and what we are working on back home. This exercise also allows the employees to reinforce and validate what they have learned at the symposia before returning home to share with others. Finally, these symposia are a great opportunity to meet and share with customers and vendors because many of them attend the same symposia.

We can all relate to the fact that by meeting with someone in person, we can exchange the equivalent amount of information contained in a small book in about twenty minutes. Getting together is still by far the most efficient method for exchanging knowledge. Even though we can justify this strategy based solely on what is gained, we can also see how it reduces the travel time and cost that would otherwise have to be incurred to achieve the same outcome. This is an example of where people need to look around and take the opportunities presented to them. We have gotten a lot of mileage from these “hybrid” external/internal experiences.

EXHIBIT 4.13 Balancing Innovation and Profits

An Interview with Paul Rothweiler at H.B. Fuller

Q: How would you describe the management of IP at H.B. Fuller?

A: H.B. Fuller is a specialty chemical company and historically our primary focus was on selling adhesives, sealants and coatings. Our understanding has changed and we now see that we are a provider of not only a material, but also a provider of knowledge around materials, manufacturing, and processing. We have come to realize that what we know has great value.

Several years ago our then CEO, Walter Kissling, decided to put together a project called P2K, which was short for Project 2000. One part of P2K was a project we called TKS, which is an acronym for Technical Knowledge System. It was during the design of TKS that I became aware of all the areas that are involved in managing intellectual capital. (See graphic at the end of this chart.) You might say that while working on the project, I codified what we were attempting to codify.

Every company has knowledge about customers, competitors, its products, and projects. These items typically fit on the right side of the chart because what is known about these topics is usually codified so that it can be shared amongst other communities. On the left side of the chart we have tacit knowledge, that is rich in texture and can't easily be codified so that it can be shared with others in the corporation and/or the company can't ‘afford’ to codify. Many companies shy away from attempting to formally manage tacit knowledge because we're now talking about things that rely on human dynamics, human relationships in order to be managed. There is also a tendency for some to deny that it is possible to influence/manage tacit knowledge because they just haven't taken the time to think about how to go about it. It's much easier to conceptualize and deal with the things on the right (codified knowledge), because we are familiar with how to manage it through computer systems and documents. It's easy to populate and its distribution does not rely on human dynamics.

From the very beginning we had a three-word phrase, ‘capture, distill, distribute.’ At the heart of it all was the commitment to generating and leveraging knowledge. Because the system is a loop, there must be a balance between managing tacit and explicit knowledge in order for a knowledge management program to perpetually create value. You can also think of it as a balance sheet, with an investment in time and resources to create ‘potential value’ in the form of tacit knowledge' innovation, with activities for turning the potential into kinetic value and revenues.

Once H.B. Fuller addressed its need to design a global system for codifying knowledge, we then started to pursue ways to improve the management of our tacit knowledge. A team was put together with representatives from various parts of the company to determine H.B. Fuller's needs and propose a series of programs, starting with the introduction of a ‘yellow pages’ of tacit knowledge. The intent of building a yellow pages was to make it possible for people to find other people who have common interests; somebody who would have experience on a particular topic regardless of what division or country they were in. From this discovery process communities of practice would then naturally be allowed to form, resulting in increased efficiencies in problem-solving abilities and an increase in the quality and rate of innovation.

Taking all this into consideration, Fuller decided to pursue the codification of knowledge. While I support the decision, there is a part of me that would have preferred to shift the balance of our efforts a little more toward augmenting existing tacit exchange programs, and introducing new ones. The reason I feel this way is because it is the rich, tacit knowledge that has the large return on investment, whereas the codification of information and data. At best, it creates incremental improvements. Innovation is going to happen more often while managing tacit knowledge.

The balance is going to be different in every company and each needs to find the right balance for their situation. The fulcrum point will also change over time due to external and internal forces. Seeking that balance is the ultimate journey.

Q: Once Fuller made the investment, how did you put the product in place?

A: TKS was designed in modules which included training on how to use the tools, the ‘dance steps’ people were to perform in the form of work instructions, the definitions in the form of standards, metrics, and additional behavioral information in the form of ‘best practices.’ Each of the divisions was given essentially the same package to implement and each assigned an Implementation Manager to assist them in the preparation and implementation of the modules.

The Implementation Managers were very important throughout; they provided input during the design phase, tested the tools and processes, provided counsel to the divisions' management team, delivered training and closed the feedback loop to the design team. The Implementation Managers made sure there was a handshake between the design team, line management, and the users.

Q: So is it safe to say that a company has to decide ahead of time why it wants to codify knowledge?

A: Yes, to make sure there's a return on the investment. Before starting the codification process, the business needs to decide what value the codification will bring and to fully understand the intentional and unintentional outcomes from the proposed processes. Reasons for codifying knowledge include creating a broader understanding of new and existing products/services that the company sells in order to improve overall performance. The intention may be to improve learning, to increase the speed and/or reduce the cost of delivery. A company may also decide to codify for revenue generation purposes, to sell the know-how. All three things have very different returns on the investment.

In H.B. Fuller's case we used a corporate strategy to guide us in what we would codify in addition to an internal team of subject matter experts from various parts of the company to verify our decisions. If we hadn't used this process we could have superseded the corporate strategy with our own unintended strategy, which would have lengthened the time to implement the corporate strategy.

Best Practice 5: Focus on Strategic Value Extraction

Having a truly integrated Level Four IP function can also help in the merger, acquisition, divestiture, and joint venture activities of the company. It can also help with commercialization.

When companies at the Integrated Level acquire assets or entire companies, the IP function is equipped to value the intellectual property included in the transaction. The well-integrated company can identify potential acquisition candidates by studying their IP portfolios. Texas Instruments' acquisition of Amati is a case in point. TI paid $400 million for a company with $40 million balance sheet value in order to gain access to valuable DSL patents. Similarly, in the mid-1980s, SGS Thomson purchased a company called Mostek from United Technologies for $71 million, and within seven years generated $450 million in licensing revenues.4

Jim O'Shaughnessy of Rockwell observes:

In buying and selling companies, we do a strength/weakness analysis. ‘I have these complementary assets over here. What do I need in order to create intellectual assets that are optimal for the mix I have and for the way I see it evolving?’ We ask these questions when we start to do an acquisition. ‘What are we going to get? What is the new company going to look like when we're through?’; We're buying human capital. ‘How do we keep it here?’ Our corporate development team has adopted an analytical way to look at innovation, and is seeking to develop complementary assets of the right type.

Often we are just given a portfolio of patents and maybe copyrighted information, and we'll go back and try and understand what else are we getting or what else should we be looking for? For example if it were a small company, what's the real critical nexus of knowledge in that company? If you find out it is in two scientists, the patents are nice but they are not worth anything without those two scientists. Then the deal better include some way of keeping these two scientists.

In addition to its ordinary acquisitions, a well-managed Level Four IP function is constantly alert for opportunities to acquire IP from troubled companies or bankruptcy trustees at a fraction of original cost.

The Level Four IP function is also integrally involved in the divestiture of corporate assets or divisions. It can be the responsibility of the IP function to be sure that all IP assets are properly linked with the appropriate business units. When there is an overlap of patent use between divisions or business units, the IP function can ensure that valuable assets are not mistakenly sold with the divestiture.

Here are some cases in point:

- One well-known consumer products company accidentally sold one of its patents as part of a divestiture, only to learn after the fact that the same patent protected an important product line within the core business of the company. To its dismay, it had to license the patent back from its new owner. Had the IP function of that company been fully integrated into the rest of the company's operations, that unfortunate event would likely not have happened.

- Another consumer products company spun off a paint brand without realizing the trademark they were giving away was more valuable than the entire purchase price they'd negotiated.

All these tales can be warnings to acquirers and sellers of company units.

The Level Four company also relies upon its IPM function to assist in the identification and design of joint venture activities. Many of today's largest companies are entering into joint venture arrangements with each other and with much smaller organizations. Often the most important contribution to the assets of the joint venture is the IP and know-how provided by one or more of the partners. Procter & Gamble recently announced its joint venture Emmperative—an online company that would enable multinational corporations to manage their global marketing campaigns through the Net. Emmperative estimates that the market demand for these services might be worth two to five billion dollars over the next few years. P&G's contribution to the joint venture is its substantial marketing know-how. P&G estimates that the venture's online format could enable a firm to launch a brand from scratch 30 percent faster. P&G has spent the last 160 years honing its marketing expertise across a product line that now contains about 300 household brands, including Tide, Pampers, and Pringles.5 The Level Four company counts on its IPM function to help minimize the investment and maximize the return on those joint venture contributions.

As O'Shaughnessy from Rockwell elaborates:

The one thing that I did was work with our senior executives to convert them in small steps. The idea that ultimately resonated was that value is now a function of both intellectual capital and financial capital. If we don't build a fund of intellectual capital, all we're doing is putting a lot of pressure on our balance sheet and making financial capital carry all the water. It's unwise. You can create a fund of intellectual capital for about one-tenth the cost in the same sense that I used in our earlier example of a million-dollar problem to solve, or a million-dollar opportunity to seize. In the past at Rockwell, you passed the hat in order to find a million dollars to solve your problem or seize your opportunity.

Level Four companies look beyond IP to IA to extract more from their IP revenues. They are interested in directly commercializing their know-how. For example, DuPont for many years has had a stellar safety reputation and expertise. Many companies interested in having world-class safety processes would go and benchmark with DuPont. In 1999, DuPont spun-out its safety knowledge into a free-standing business. Now it is generating revenue directly from its know-how. Daniele of SAIC explains his views on know-how commercialization.

At SAIC, I have tried to create a framework for how management should think about know-how commercialization and the risk/reward trade-off. The goal is to reduce risk and add value at each stage or event. By so doing, your options open up. We always convince people who come to us with a technology commercialization idea, to put together a business plan, and we help them do it. As a precursor to every technology commercialization activity, the questions we ask are very simple. First, does the technology work, and second, does anyone want to buy it now? We ask these questions until we understand the answers. Given a business plan, even a short, simple one, you can then go out and speak to customers and get some feedback on your products, markets and approach. If you can't get some initial customer interest, the market may be telling you something. Maybe you are going in the wrong direction. Maybe the packaging is wrong, or it is ahead or behind its time, or it adds insufficient value. If you have some customer interest, then you have choices. You can sell it yourself, spin it out, license, or partner.

You sometimes need to start thinking about complimentary assets. You have to understand what is missing. When we go visit with customers we always try to learn something. Most don't buy initially, but you always try and find out why. You always ask their opinion of the technology or product or its downsides and problems. We use the feedback that we get.

We had a case of a B2B start-up where we got customer and VC feedback early on, and it substantially changed the plan and created a much more valuable business as a result. At each decision point, moving ahead with customer feedback adds value to the bottom line and it also opens up options. The key is to add value through every commercialization event from business planning through customer feedback and product delivery.

CONCLUSION: ON THE BRINK OF VISION

Journeying forward with Thomas Edison, we have covered four of the five levels of the Value Hierarchy. If you have read this book thoroughly to this point, you now know how to move your IP function from the Defensive Level, up to the Cost Control Level, on to the Profit Center Level, and to the Integrated Level. You have also seen some of the best practices used at all these levels.

Are you ready for the Visionary Level—the fifth, and most valuable level?