1

LEVEL ONE—DEFENSIVE

IN THE GOLD rush days of more than a century and a half ago, “Forty-Niners” learned there were different levels of value to be obtained from gold mining. The first of these involved staking and defending a claim. Today too, the first step is protection. This is the spirit of the Value Hierarchy's Level One: Defensive shown in Exhibit 1.1.

Defense of intellectual property—including patents, trademarks, and copyrights, as well as ownership offered through various types of agreements—is a necessary and desirable activity. Indeed, protection is the foundation of value. For example, patents give inventors adequate time to apply and market an idea before others do.

Much as a miner must stake a claim in the land containing gold, or a shareholder must hold a stock certificate, a patent holder must own a patent. Only after staking claims can the owner of the intellectual property actually achieve the other levels of intellectual property value. To continue the “gold rush” metaphor, these might be seen as panning (Level Two, the initial savings of cost control), mining (Level Three, deeper profit-seeking), processing (Level Four, integration with other operations), and, finally, sculpting into new forms (Level Five, Visionary). These five levels constitute an overall process for the management of intellectual property—a process that depends on the foundation of defense of ownership.

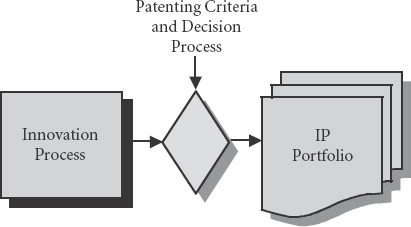

We begin our discussion of best practices by focusing attention on the companies at the first level of IP management—the Defensive Level. Level One firms are concerned with the creation and management of sufficient numbers of patents protecting the firm's technologies to ensure defense against potential infringers. Companies at this level typically see the role of intellectual property as purely defensive. The primary concerns for companies at this level are the classical defensive objectives: protection, litigation minimization, and design freedom. Companies at this level are often focused on accruing a sufficient number and breadth of patents to provide the desired protection. These companies are involved with creating and implementing processes for identifying technologies offering patenting opportunities, screening these opportunities against the company's vision and strategy, prosecuting the patents through issuance, and enforcing the patents against infringers.

WHAT LEVEL ONE COMPANIES ARE TRYING TO ACCOMPLISH

At Level One, companies are trying to accomplish five things:

- Generate a significant number of patents for their IP portfolio

- Ensure that their core business is adequately protected

- Initiate basic processes to facilitate patent generation and maintenance

- Initiate basic processes for enforcing patents

- Ensure that their technical people have freedom to innovate

Management activities for Level One companies often are pointed toward getting the largest number of applicable patents as quickly as resources will allow. Companies at this level are concerned with the quantity and quality of patent output (effectiveness). While costs are a natural concern, they are usually of lesser importance than the need to obtain the desired protection. According to Joe Villella, a partner with the Palo Alto law firm of Gray Cary Ware & Freidenrich, “Very often, companies at this stage are playing catch-up as they realize that their competitors have patent portfolios and they don't. Sometimes this point is driven home when they're on the wrong side of a license agreement and have to pay royalties to someone against whom they're competing in the marketplace.”

At Level One, companies are concerned with only the portions of the IP Management System that are the province of the IP attorneys (see Exhibit 1.2).

IP attorneys at smaller Level One companies typically spend time with the innovative R&D people to learn what kind of new ideas or projects they are considering. Through informal conversations, IP attorneys seek out ideas that are patentable, and then gather them into a prioritized list. They give the highest ranking to ideas related to the company's key innovations, and to those covering tactical or business opportunities. At larger companies, attorneys tend to branch out more, according to Henry Fradkin, Director, Technology Commercialization, Ford Global Technologies, Inc. (a wholly owned subsidiary of Ford Motor Company), “Attorneys may spend time with key client groups. They may also serve on patent committees to decide whether an invention should be patented. Attorneys may give presentations to draw out new invention disclosures.”

This direct, dynamic approach to prioritizing and patenting the company's innovations has both advantages and disadvantages. On the advantage side, the method is simple, direct, inexpensive, and efficient—there is very little wasted effort. Nevertheless, there are some disadvantages that need to be mentioned. The process relies heavily on the IP attorneys' ability to know what is valuable to the firm—including what is strategic, tactical, and/or marketable. Further, it assumes that the IP attorneys are fully aware of competitors' business and patenting strategies, and can effectively use the company's patent creation process to neutralize competitor IP actions. Finally, the Level One approach assumes that the attorneys are constantly apprised of any changes in company strategy and tactics so that they may revise the criteria used to screen innovations for patentability.

All these expectations are worthy, but hardly realistic—especially in companies operating exclusively at Level One. Such companies are interested in IP primarily as a means to protect the ideas embedded in the products and services that they sell. Here intellectual property is used as a legal means to keep others out of their markets. Indeed, intellectual property in Level One companies is viewed as a legal asset. Fortunately, thanks to the progress made in the past few decades of patent law, IP can indeed be such an asset. (See Exhibit 1.3.)

EXHIBIT 1.3 A U.S. Example: The Federal Circuit

Defense is integral to IP management in any company. Fortunately, in many countries, staking a claim in intellectual property is easier today than ever before, especially where patents are concerned. In the United States, for example, patent appeals are now centralized in one court: the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, known as the “Federal Circuit,”1 which has exclusive jurisdiction over all patent appeals from other federal courts.

When viewed in light of nearly 200 years of patent law evolution, the Federal Circuit is relatively new—just two decades old. It was created with the merger of the U.S. Court of Claims and the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals—a consolidation ordered as part of the Federal Courts Improvements Act of 1982.2 The courts certainly did need improving from a patent law perspective. Indeed, before 1982, it was not only ineffective to defend a patent by suing over infringement; it was plain risky. In the so-called Black-Douglas era (named for the Supreme Court Justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas), the courts feared the monopoly potential of patents and discouraged them accordingly. In this era “the chances of a patent being held valid, infringed, and enforceable, were one in three,” ICMG cofounder Patrick Sullivan has noted.3

The courts, rather than focusing on the wrongdoing of the infringer, tended to focus on the protectability of the allegedly infringed patent, and often declared patents invalid. Consider the classic case of Westinghouse. Long before its restructuring and merger into CBS and later Viacom, the electronics giant sought to protect its circuit-breaker patents. In 1979, it petitioned the International Trade Commission to block imports on the grounds that Hitachi was infringing one of its patents. The federal courts ruled that the Westinghouse patent was not valid.4 Westinghouse's attempt to defend its own rights caused those rights to be taken away.

This sad era in patent law is now long gone. The Federal circuit of today is handing down decisions more favorable to patent holders—making defense more worthwhile than ever. The protectability of intellectual ideas is a new and valuable notion, says Mark Radcliffe, a senior partner with the Palo Alto-based Gray Cary Ware & Freidenrich: “It has only been in the last 20 years that intellectual property and especially patents were regarded in U.S. courts, not as the tools of monopolists, but as critical to national economic well-being. Furthermore, it is now generally accepted that such innovation cannot occur unless companies that succeed in the marketplace can recoup their research, development, and marketing costs. The upshot is that intellectual property is now viewed as playing a key role in developing technologies for the next century.”

BEST PRACTICES FOR THE DEFENSIVE LEVEL

What, then, is the best way to defend IP assets? The current practice of defense is adequate, but not ideal. Having an exclusive, permanent defensive mentality can cause companies to incur unnecessary costs and forsake opportunities for revenue. To be an “Edison in the Boardroom” requires a pragmatic approach—one that adopts certain best practices.

So let us look at the practical application of defensive IP management, and examine some of the best practices used by other defenders.

In our work, we have seen five best practice areas at this level. They are listed in Exhibit 1.4.

Best Practice 1: Take Stock of What You Own

The value of research and development (R&D) is often invisible—not only to outsiders, but to IP managers as well. That great new technology just perfected by your R&D department and patented by your legal group will never appear as an asset on your company's balance sheet because it was internally generated, rather than purchased from someone else. Will you remember that it is there?

It is not unusual for us to interview corporate officers and find that they have no idea how many patents their company owns. Even with the few who do, it is often the case that they have no real understanding of what resides in their portfolios. This is not surprising. Prior to introduction of recent computer software programs designed to help manage intellectual property, the only way for a company to really understand what comprised its patent portfolio was to read each individual patent.

Some time ago, the authors met with the new licensing manager at an electronic components company that held 700 patents. We asked him how he was planning to “get his arms around” the portfolio and learn its contents. He replied that he planned to read each of the patents in full. “How long do you expect that to take?” we asked. “Well,” he replied, “I think I'll be able to make it through about two patents a week.” He was in for several long years of work! In another instance, when we met with the chief patent officer of a Fortune 500 firm, and asked what was contained in his portfolio, he sighed and pointed to some 20 file cabinets containing all of his company's patents.

EXHIBIT 1.4 Defensive IP: Best Practices

Best Practice 1: Take stock of what you own.

Best Practice 2: Obtain intellectual property while ensuring design freedom.

Best Practice 3: Maintain your patents (don't let the good ones lapse).

Best Practice 4: Respect the IP rights of others.

Best Practice 5: Be willing to enforce, or don't bother to patent at all.

Companies are now able to download the contents of their patent port-folios from a variety of online sources. If nothing else, companies should create a list of all of their intellectual property that has been granted, filed, and is currently pending.

According to John Cronin, CEO of ipCapital Group, Inc., a professional services firm specializing in creating and executing intellectual property strategies and portfolios, “We need to remember that intellectual property is not just patents. The way we help our clients think about intellectual property is to visualize it in terms of protected innovation, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.5 by a set of concentric circles.

The inner circle illustrates trade secrets. We always recommend that inventors maintain some portion of their invention as a trade secret. A trade secret is a company's know-how, in other words a combination of things that individually are well-known but in combination are not known and provide leverage, but would not be patented because the patent would expire before the product leaves the market (like Coca Cola®) or by the time a patent would issue, the technology would change again. In terms of defensively protecting your intellectual property, this is core to a good strategy. If you have patents, and you don't have a formalized trade secret program, then chances are the company doesn't understand the elements that make up a comprehensive and wells-protected IP system. This is key, because in our experience, too many people patent an invention without reserving the appropriate piece as a trade secret. To maximize the value of the patent, you always want to patent what no one else can do, and you never want to give away the complete recipe.

The next circle illustrates another layer of strategic protection: defensive publishing. We believe the concept of prior art management and defensive publishing will continue to grow as a focused strategy primarily because companies are constantly in the position of having to incrementally justify the cost of the volume of patents it believes it needs. By integrating defensive publications into the picture, a company can employ a tactic that strengthens the position of its basic patents by publishing—in volumes if necessary—around the patents.

Next is the circle containing all the enabled documentation, which is really where it all begins. Nothing can progress to a patent, a publication, a trade secret, or any other intellectual property instrument unless you have the enablement documented. In any IP portfolio there will be some initiatives that are documented, but not converted to trade secrets or patents or publications. They are documented, nonetheless, as confidential subject matter.

The outer circle illustrates an emerging best practice called IP insurance. Surveys of CEO's around the globe demonstrate that they all agree on one major issue: Creative ideas rapidly converted into enabled innovation are mandatory to success. And no matter how well you cover the bases, mistakes will be made. We believe that IP insurance will continue to grow as a standard risk management best practice.”

As a part of this inventory, companies should also look beyond the narrow definition of intellectual property to include IP-related documents such as license agreements. A license agreement, often referred to simply as a license, is an agreement between two parties (companies and/or individuals) regarding the use of intellectual property. License agreements can be for an in-license or an out-license. An in-license agreement means that one company can use, adapt, sell, or otherwise benefit from another company's invention. An out-license does the opposite. The inventory of licensing agreements should include both “in” licenses, requiring the company to pay for another party's intellectual property, and “out” licenses. Some companies engage in numerous cross-licenses—discussed further below.

Licenses are essential to the ability of a corporation to continue to conduct its business. Therefore, the IP function should ensure that all such necessary licenses are current and in good order. In order to use licenses effectively, a company should review the proper documents pertaining to licenses, including:

- All intellectual property licenses where the company is a licensee, including names of parties, dates of expiration, rights granted, and any pertinent restrictions such as territory or transferability.

- All intellectual property licenses where the company is licensor, including names of parties, dates of expiration, rights granted, and any pertinent restrictions.

In addition, the inventory needs to take into account nondisclosure and noncompete agreements, joint venture agreements, and any partnerships related to the exchange of intellectual property.

EXHIBIT 1.6 An Intangibles Audit List

- All inventions that are not the subject of issued patents, but may be the subject of patent applications, or where the company may be able to establish dates for invention, discovery, or reduction to practice dates.

- All software developed by or for the company

- All known trade secrets from which the company derives economic benefit by keeping it secret

- Documents reflecting the company's policies and procedures relating to the creation, maintenance and protection of trade secrets, such as the company's written confidentiality policies and nondisclosure agreements

- Documents relating to hiring and exit interviews of technology and other sensitive personnel

- Nondisclosure agreements (often called NDAs) with R&D staff

- All license agreements whether the company is the licensor or licensee

- Any documentation relating to proprietary know-how such as a description and the place or person in whom it resides

According to Gray Cary's Villella; “The first step in getting a handle on your intellectual property, is to know what you own. We advise companies to inventory their intellectual property that has been granted, filed and is currently in process and update it routinely.” For a more detailed description, see Exhibit 1.6.

Best Practice 2: Obtain Intellectual Property while Ensuring Design Freedom

Whether your inventory turns up only a few patents or many, it is wise to encourage the creation of more patents. This means, in part, encouraging innovation—an important aspect of patent acquisition. (In addition, patents can be acquired from other companies, but this is not always possible or optimal.)

Jim O'Shaughnessy, Vice President and Chief Intellectual Property Counsel, Rockwell International, believes strongly in the importance of not only generating but also protecting new technology. His company has not always emphasized protection, however. “Think about what Rockwell has always been—at least within our lifetime. It's been a pioneer in air and space. We are the company that made B-1 bombers and space shuttles.” With such grand programs, sometimes patents got overlooked, he notes wryly. “It was more important to know four-star generals than to know the top patent attorneys.”

In 1996, Rockwell sold its aerospace and defense operations to Boeing Company. The remaining company had to build on its nondefense technology—which required an expansion of its IP profile. At first, many managers thought that they could simply go out and buy the technology. But recently, the company has come to realize the importance of generating technology at home. “We will continue to buy, but we will buy with one hand, and build and protect with the other,” says O'Shaughnessy.

As IBM's top inventor and, now, as a CEO of an intellectual property professional services firm, John Cronin has been able to live every step of the creative process that goes into building new technology. “I firmly believe that at the core of all well protected innovation is understanding what an invention is, and then understanding the supporting elements that must be included in the documentation. More opportunity is lost and liabilities incurred because people don't pay enough attention to the art of documenting invention. If it's a publication, it must be documented as ‘enabled prior art.’ A trade secret, same thing. It is the ability to enable and document invention, including never losing sight of the constantly evolving requirements of IP, that creates the envelope of protection. No matter what strategy you employ, no matter how vision you are, no matter what your licensing-out program is, it never gets anywhere, really, unless the core engine of intellectual property is the inventor documenting his invention. We tell our clients, if you do this one thing well, you will be miles ahead of every company. In fact, we advise our clients, as an exercise in due diligence, to include in the process of a product release one last look at the thinking that went into the product, at the inventions surrounding the product, the publications, the trade secrets and most importantly, the credibility of the documentation. I have yet to meet a company that has the required discipline built into its product release cycles, not one. Unfortunately, I've met many companies who wish they had, so we have a long way to go.”

Tom Colson, CEO of IP.com, a popular repository for prior art management, adds, “We created IP.com as the world headquarters for prior art management because we knew that the number one challenge that goes hand-in-hand with patenting is that it is extremely expensive to protect all corporate innovation with patents alone. But we also know that it is potentially far more expensive to go without patenting. As the patent race becomes more and more aggressive, patenting becomes more and more expensive. After you add up the legal fees, government fees, maintenance fees, translation fees, inventors' time, and more legal fees, it's hard to believe that anyone can afford to file patents for even a small fraction of their inventive ideas. And when you consider that the number of inventive ideas in most companies is approximately 10 times the number of developers, engineers, and researchers per year, it becomes clear that patenting all corporate innovation is an impossibility.”

“But, what if you don't patent? And worse, what if your competitors patent the innovation that you leave in a drawer? Now the costs get out of control: litigation fees (Average legal fees for a patent infringement case in the US are over $1.5M, regardless of the outcome.), adverse verdicts (It is now common to see eight and nine figure verdicts, and recently there have been a few 10 figures verdicts.), royalty payments to your competitors, downstream redesign (sometimes post product launch), and lost time to market (preliminary injunctions, wasted time of developers in depositions and trial, and permanent injunctions).

“So how do you protect your freedom to practice without patenting? You can publish defensively, an activity that is becoming increasingly important to the overall strategy of protected innovation.”

So how exactly can an organization obtain intellectual property by encouraging innovation? One source of good ideas is the Human Capital division of Andersen, which has worked with many companies seeking to encourage innovation through their systems for employee management, recognition, and reward.6 Here are some techniques companies are using.

- Institute a formal “innovation initiative.” Senior management can adopt a slogan or phrase that expresses a commitment to the continuous generation of ideas that can be brought to market. One famous example of this is the new Hewlett-Packard logo, which shows an imperative slogan, “INVENT,” under the HP signage.

- Dedicate resources to innovation—including the resource of time and a climate of cooperation. Some of the biggest killers of innovation are inhuman workloads and an excessive degree of interdepartmental competition.

- Ensure employees' intellectual development by instituting a program for training and job transfers. Nothing dulls creativity like routine; and nothing enhances it more than new challenges. Do not let your employees get in a professional rut.

- Encourage work groups. Structuring work groups not only improves performance but also contributes to self-esteem and sense of empowerment.

- Communicate, communicate. Organizations can encourage innovation by showcasing successful innovations through vehicles such as company newsletters, press releases, and rallies. If senior management sees barriers to innovation in the organization, the communications can explore these as well.

- Include innovation in the company's appraisal program. Leadership skills, technical competence, relationships with others, judgment, and creativity, can all be measured, coached, communicated, and encouraged. Such attributes should be a part of the assessment of all employees, especially those who are managing R&D staff.

- Support “intrapreneurs.” If an employee goes against the grain, others may chafe. Senior managers must look beyond criticism based on personality clashes and see if the individual's ideas have merit worthy of financial support.

- Design an innovation reward and recognition program. Compensation literature is full of ideas for how to incentivize behavior—and creative behavior is no different. Employees respond to nonmonetary as well as monetary awards.7

On this last point, most companies offer incentives to encourage their scientists, engineers, and other inventors to notify the IP function of potentially patentable discoveries. Indeed, all but one of the companies we interviewed used some sort of patent incentive system. ICMG's benchmarking studies on incentives have found this typical pattern for incentive programs:

- $25 to $100 for each disclosure submittal

- $500 to $1,500 for each inventor upon submittal of patent filing

- $500 and/or a plaque upon patent issuance

And some companies also increase the reward to their inventors by adding an extra incentive for company usage of the new technology.

Not all companies reward their inventors in dollars. Most companies combine dollars and peer recognition as integral parts of their incentive structure. The ultimate determination of the incentive structure should be based on the culture of the firm and also recognition of whether patenting is in the job descriptions of the technical personnel. (See Exhibit 1.7.)

As the scope of what is patentable continues to increase (now including business methods, for example) incentive systems may need to be broadened as well to include nontechnical (i.e., business and administrative) personnel under the heading of “innovators.” In doing so, a company may need to mount a strong IP education and process to indoctrinate nontechnical personnel into the ways of intellectual property.

EXHIBIT 1.7 Recognizing and Rewarding Innovation

An innovation reward and recognition program might contain the following elements:

Nonmonetary awards

- Extravagant luncheons or dinners celebrating innovation

- Gift certificates or catalogue gift awards

- Plaques, ribbons, and other recognition awards

- Honorable mention in the company newsletter

- Free time off

- Free educational courses

- Election to an Innovation Circle or Innovation Committee

- Innovation trips (offsite meetings focusing on innovation)

Monetary awards

- Raises in base salary (better annual pay for successful inventors)

- Cash bonuses (awarded to individuals or teams for successful inventions)

- Promotions (granting a better title to inventors)

- Phantom stock (paying “dividends” on increasing value of innovation)

- Gain sharing (group shares in income from their invention)

- Funded pools (setting aside revenues from invention for key individuals only)

- Performance incentives (same as gain-sharing, but tied to efforts at commercialization)

Adapted from HR Director: The Arthur Andersen Guide to Human Capital (New York: Profile Pursuit, 1999), pp. 142–144.

The criteria used to screen patents should be a part of any incentive program the company may have to generate patents. Most companies will typically offer incentives to encourage their scientists, engineers, and other inventors to notify the IP function of potentially patentable discoveries.

According to John Cronin of ipCapital Group, “When I was an inventor at IBM, we surveyed 30,000 employees/inventors. And we tried to determine the number one reason why inventors invented. Out of 30,000 people, do you know what the number one response was? Most inventors invent because they like to solve problems—intrinsic motivation! They like the challenge, OK? But you know the number one reason why people actually wrote the patent up? For the money. The remuneration we gave them was considered compensation for the administrative efforts they had to go through to submit the patent. The real self-satisfaction came from solving problems, but we still needed the inventors to write up the invention, and to care about doing it right.”

At IBM, the screening process determines the award given for each disclosed invention. A small award is given even for invention disclosures that ultimately result only in defensive publications. Larger awards are given for disclosures deemed patent-worthy by the screening process. Plateau awards sit atop the individual filing awards, and factor in both invention disclosures rated for publication and those rated for patenting, encouraging disclosure generally, quality in particular, and “repeat” business. The program has helped IBM generate thousands of invention disclosures and thousands of patent applications a year.

Rockwell, for example, has abandoned its old incentive approach that rewarded engineers and managers for filing a large number of patents. Instead, the company is focusing on the quality of the innovations. It is currently working on a plan to offer nonvoting restricted stock keyed to the value of the innovation, according to Rockwell's Jim O'Shaughnessy. A unique approach used at Avery Dennison was to issue gold and silver coins. Paul Germeraad, former VP and Director, Corporate Research explains “issuing collectable coins was a clear statement that the true value of an asset extends well beyond its face value. The coins had face values of one dollar, but a market value of between $10 and $150 depending on the date and precious metal content. These coins were valued more highly than any of the cash awards we offered.”

Some companies worry that incentive programs for innovators can become entitlements. Steve Fox of HP has found a way around that. “We try to avoid having the incentive become an entitlement, so we say the incentive program is for a one-year period and renewable for a subsequent one-year period upon the decision of the general manager of the business based on what he or she sees as the results of the program. This permits the manager to stand up in a coffee talk and say ‘Our program did great last year, we're going to renew it; and this coming year we'd really like to see more invention disclosures in such and such an area.’ You'll pick a technology—let's say Internet interface printers—and the incentive program permits you to steer inventions into that area.”

Even aside from the commercial value of patents, obtaining patents can be valuable as a potential counterdefense. Having a great number of patents helps shield a company from lawsuits by giving it the wherewithal to countersue. Competitors think twice before filing a patent infringement lawsuit against a company that could turn around and sue them on a different patent. When filing for patents, one need not stop at one. The great defenders develop a literal “thicket” of patents surrounding single inventions. Gillette is famous for utilizing this practice to sustain a market choke hold. According to John Bush, Gillette's former vice president of R&D,

We patented the key design features in the cartridge, the springs, the angle of the blades, that sort of thing. There were also patents covering the handle and some of its characteristics. We even patented the container that had the proper masculine sound and feel as it was ripped. We covered all the features that we thought would be of value to the consumer. We created a patent wall with those 22 patents. And they were all interlocking so that no one could duplicate the product.8

Lee Benkgay, general counsel for the biotechnology firm Incyte, likens patents to a “protective” shield and, furthermore, to money: “Patents are like currency,” he says. “The more, the better.”9

For attorney Joe Villella; “One approach to building a portfolio is known as the “coal pile” approach. If the coal pile is big enough, there's bound to be a diamond or two somewhere in the coal pile.” Villella continues:

A problem with this approach occurs when you're dealing with a sophisticated potential licensee who actually searches through your coal pile and doesn't find any diamonds. Companies are not willing to pay diamond prices for chunks of coal. It can also be more than a little embarrassing when you have to tell your CEO that despite all the patents that you've been able to obtain, not a single one of them covers the products of your biggest competitor.

To ensure broad coverage, Hewlett-Packard initiated a program to increase its pace of patenting in 1996. In two years' time, the program achieved a 60 percent increase in the number of patents issued. The program, now five years old, pays various awards to inventors. There is a small cash award on submitting an invention disclosure, and then a larger cash award when the patent application is filed. A personalized plaque is presented when the patent is granted. The company also recognizes its inventors in public gatherings such as coffee talks or annual banquets. Financial aspects of the program are handled by the R&D functions, while the legal department identifies the inventors and handles the creation of the plaques.10 Ford Motor Company has a similar program that also has been very successful in soliciting new ideas and inventions for quality patents.

HP is not the only company that has made valiant efforts to increase the level of its patented inventions. This is one of Microsoft's keys to marketplace success. At the beginning of 1990, the company had only five patents. The leadership team, headed by CEO Bill Gates, made a strategic decision to increase the number of patents. By the end of 2000 Microsoft owned nearly 1,500 patents.11

Yet another example of a proactive patenter is Celera. Robert Millman, Celera's general counsel, regularly attends research meetings to discuss genetic inventions, helping engineers to decide which are worth patenting, and which would receive better protection as trade secrets.12

Setting goals for a high number of patents can have negative (but preventable) side effects. A single patent attorney working in a corporation cannot do it all. In the words of Bill Frank, chief patent counsel for S.C. Johnson:

The patent lawyers will put a lot of time into intellectual asset management. When they do, they will recognize that they also cannot file “x” number of patent applications that year. If they are trying to accomplish both tasks, the “x” will usually win, and the asset management will fall by the wayside. You have to give them relief on that and allow them to use outside counsel.

IBM has struck this balance using an entity it refers to as the “virtual law firm.” The company recruits its retiring patent attorneys, along with nonretirement eligible attorneys seeking a stay-at-home work/life balance. It associates these proven performers with one of its outside counsel, and guarantees them levels of patent filing and prosecution work at fixed fees. The win-win generates a large stable of company-savvy, technology-experienced patent practitioners at rates untouchable in a traditional law firm relationship. It is one of the cornerstones of IBM's push for a high-quality, cost-effective filing strategy.

Companies working to build up a large number of patent applications would be wise to heed Bill Frank's advice—and look for quality as well as quantity. One company that has mastered the high-quality or “strategic” patent is Hitachi. In 1980, the company suffered a “bitter lesson” when it lost a countersuit against Westinghouse. A recent article about Hitachi tells the tale:

Patents are valuable, of course, when the company uses them, but their true value shows up when other companies have no choice but to use them. Hitachi realized there was no point in obtaining a mountain of patents if they were not going to give the company any competitive leverage in crunch situations.13

In short, not every invention should be patented. Indeed, to paraphrase William Shakespeare's Hamlet, To patent or not to patent? That is the question. Unfortunately, it is a question that is not asked often enough in the halls of the great defenders. The mentality in such companies was born in a time when the best defense was a good offense—ownership of as many inventions and patents, in as many areas as possible.

Rather than patenting everything, it may be best to consider a spectrum of patenting options—including patenting nothing at all (which may be a valid strategy for some businesses at certain times).

Here are the main choices, based on our experience with a variety of companies:

- Do not patent anything.

- Patent the occasional discovery of quite exceptional importance.

- Patent discoveries that have a clear application to your own company's products or processes.

- Patent discoveries that have a strong chance of technical success regardless of potential business application or use.

- Patent discoveries that might block or delay products implementing similar later discoveries by other companies within or outside one's industry—“strategic patents.”

- Patent in order to have a portfolio with which to negotiate business agreements (licenses, joint ventures, alliances, and so forth) with other companies.

- Patent everything that is patentable.

This leads us to another important aspect of encouraging invention. As much as technologists would like to design every aspect of the company's products and technologies, no one company can design everything relating to their products. According to Jerry Rosenthal, Vice President of Intellectual Property and Licensing at IBM,

Cross-licenses are very valuable to IBM. We can't invent everything. It is important to keep your business growing. To grow in the IT industry you need to have access to inventions of others. We have patents that our competitors need, and they in turn have patents we need. We view cross-licensing as a strategic opportunity rather than a compromise. For example, we make inventions in businesses we are not in or won't go into. We use these inventions not only for revenue generation, but also to gain access to others' portfolios outside the core of the IT industry.

According to Steve Fox, Associate General Counsel of Hewlett-Packard:

Getting patents does two things for you: not only does it establish your prowess in the business, but it also gives you trading material so that if somebody else happens to be better at a disruptive technology than we are—for example some smaller start-up companies who can move very quickly—they may wind up with patents in key areas in disruptive technologies and beat us to the punch. But on the other hand, it is only a matter of time before this start-up company moves into our competitive space, infringing our patents, and then we often end up agreeing to cross-license.

So what does it mean to ensure design freedom and have access to the technology of others? Well, it means that a company's technical team can invent in a given area without the threat of infringement from a third party. It also means that a company can be immune from litigation, as we learned from Fred Boehm, chief patent counsel for IBM:

Back in the early 1970s we did a cross-license agreement with RCA. We did a cross-license and had a valuable patent portfolio and it turned out that RCA had some very basic patents that went to what is known today as the TFT/LCD architecture and displays on your laptop. This was before there were displays. Even before PCs.

We formed a joint venture called DTI with Toshiba in 1989 to make these displays. They make them according to IBM's design specifications and so all they are is a manufacturing facility. RCA still had some old but very valuable patents and went out to DTI and they said we are licensing everybody in the world to these patents and you will have to pay significant amounts of money.

Of course, they called us up and called Toshiba up and told us about this. I reminded RCA that under the license agreement we had these products were being built for IBM and also Toshiba. They were covered under the license agreement we signed in 1981. Although RCA was able to collect significant royalties from the entire industry, the IBM products DTI builds for us that go into our displays today are covered by that old agreement. This has given us a significant advantage in the marketplace.

Best Practice 3: Maintain Your Patents (Don't Let the Good Ones Lapse)

Check to make sure all maintenance fees have been paid, so that all the patents you own are truly active. If a patent lapses, you can lose it. Consider the loss this represents for a company that has made substantial investments in research and development.

Achieving strong defense does not require any complicated systems. As mentioned earlier, one can use a simple docketing system—a tickler file to remind the company of when to pay the maintenance fees. Without these basic docketing systems, there is always the risk that patents can be accidentally abandoned, because the company fails to pay the fee on time. However, larger and worldwide portfolios require more sophistication. IBM has created an end-to-end patent management system it calls WPTS—worldwide patent tracking system. Among its many functions, WPTS automatically tracks patent aging in all countries in which a patent family has issued, ensuring timely payment of maintenance fees with sensitivity to currency factors and deposit accounts available in some major patent offices.

One major company discovered during one patent maintenance review that it had allowed 10 percent of its patents to lapse. We know of another company executive who learned, while drafting a license for one of its foreign patents, that his company no longer owned those patent rights because it had failed to pay the maintenance fees on time. In a third more fortunate circumstance, one of our clients discovered that a competitor's patent on an important diesel engine technology had been allowed to lapse. Our client is now using that technology to compete in a new and profitable market.

Fradkin notes that the flip side to this is that a “good” company should have a process to evaluate the strategic and the tactical values of their patents. A default of “renew unless you hear otherwise” can lead to an expensive carrying of patents that have no value to the company and should be sold, donated or abandoned (see Level Three).

Best Practice 4: Respect the IP Rights of Others

The topic of ensuring ownership leads naturally to the subject of compliance with the law. This is another obvious best practice to pursue at the defensive level. A company must be careful not to infringe patents, trademarks, and copyrights held by others—otherwise, its ability to protect its own intellectual property will be weakened.

It is not always possible to avoid patent infringement, since inventions may occur simultaneously. However, by keeping a lab book and other records, a company can show that the infringement was unwitting—that is, that it stemmed from a simultaneous invention, not from an attempt to copy someone else's proprietary technology.

Note that patent, trademark, and copyright law are not all-inclusive when it comes to compliance. Companies must also be sensitive to trade secrets. That is, if one company uses a trade secret from another company without authorization, it may be guilty of theft under common law of “misappropriation.”

The information taken in both cases is considered proprietary, even if it is not protected under patent, trademark, and copyright law. Some companies opt not to obtain patents and instead rely on the laws enforcing trade secrets.14

As a part of compliance, companies should avoid obtaining trade secrets by hiring employees or subcontractors from other organizations considered to be competitors. If the departing employee or the subcontractor brings valuable technical knowledge, it is important to make sure the employee owns that knowledge, and that it is not a trade secret proprietary to the previous employer. As such, employers should be aware of assignments and transfers of intellectual property to or from employees and subcontractors. These documents include:

- Documents showing assignments of intellectual property to or from the company, including grants of security interests

- Documents showing the recording of assignments of applications for intellectual property rights, including grants of security interests

- Documents showing releases of security interests in intellectual property, as well as the recording of such releases

- Agreements with persons or entities that may create, work with, or have access to the company's intellectual property (including employees and independent contractors), showing assignment to the company of rights in intellectual property and confidentiality of trade secrets

- Agreements relating to data base, processing services, and/or software

- Agreements pertaining to know-how, research and development, and technology

- Joint venture, partnership, and strategic alliance agreements

- Government grants and related agreements

- Agreements pertaining to domain names, source codes, and the like

- Noncompete and nonsolicitation agreements 15

One good way to avoid lawsuits is to use product clearance techniques. The defense-savvy company is constantly exercising a product clearance process to avoid spending hundreds of millions of dollars of R&D to develop a new product only to find that it cannot lawfully sell the product because it is covered by someone else's patent. Early detection of these issues prior to the marketing of the final product ordinarily provides an opportunity to license-in any necessary patents at more favorable terms than might be available when the product's success is more evident.

New technology offers improved ways to avoid infringement. General Electric—heir to the Edison legacy—stays cautious by using Patent Adviser, its own proprietary version of the new “Jnana” software developed by New York-based litigator Frederic Parnon. The basis for Jnana software is a decision tree (if/then) that simulates legal questions. GE's version is used to avoid patent infringement. The computer queries the user about a proposed invention, and then searches a series of databases to find conflicting patents. It then assesses the level of infringement danger for the proposed patent or patents.16

IBM uses Delphion, an Internet-based company housing the entire repository of modern U.S. patents, along with patents issued in other major countries. Through traditional keyword/Boolean searching, as well as more sophisticated data-mining and mapping techniques available through Delphion, adverse patents are identified prior to product introduction.

Using Delphion, IBM has taken the clearance process a step further by integrating it into the patenting process. When an invention disclosure is searched for existence of close prior art, the prior art works both as a check against patentability and as a caution flag signaling adverse patent problems. This level of integration is in turn made possible by close correspondence between invention disclosures and products. IBM's WPTS system ensures and documents correspondence by prompting for relevant product data during disclosure submission. WPTS also includes an expert software component called the Patent Value Tool (PVT). The PVT poses a series of structured questions for use by investors and evaluators to determine the likely licensing value of an invention. Included in the PVT are questions directed to use in current or future IBM products. Actual or likely use results in a higher PVT score, increasing the likelihood of the invention being selected for patent protection. Thus, from a disclosure submission forward, IBM's IP system interlocks to integrate the clearance process (defensive) with the patenting process.

Such a product clearance process is not easy to implement but it only takes one big “find” for it to pay for itself. General Electric is now able to avoid a repeat of the patent litigation brought by Fonar years ago on one of GE's important new MRI products. The lawsuit itself resulted in an adverse judgment of nearly $129 million. And that figure does not include attorney fees or the costs of the time and energy invested in the R&D effort to develop the product and launch it commercially.

Infringement, unwitting or otherwise, costs money. For many companies, the corporate focus is on speed to market. Therefore many R&D and marketing folks are loath to engage the patent attorneys in the product development process until the very end because they perceive the legal process as “slowing everything down.” As Kevin Rivette and David Kline note in Rembrandts in the Attic,

Perhaps a better question to ask is, Who has the time (or the million-plus dollars) it takes to defend against a patent suit? And who can afford to devote a year or more of R&D effort on a product only to have to abandon it later because of an infringement problem that could easily have been spotted and designed around early in the process?17

A clear benefit of all this compliance activity is avoidance of payment to litigants in intellectual property lawsuits. It is also now possible to buy insurance to cover the company in the event of patent litigation. (See discussion of Finance and Tax in Best Practice 2 of Chapter 4.)

Best Practice 5: Be Willing to Enforce, or Don't Bother to Patent at All

A final defensive Best Practice. Once you obtain the patents, you must be willing to enforce them. Otherwise, don't patent at all. (What is the point of patenting if you are not willing to make the patent stick?) Remember, a patent is only worth what you are willing to spend to enforce it. This does not of course mean that every patent must be enforced. According to Steve Fox, Associate General Counsel and Director of Intellectual Property for Hewlett-Packard:

We have had to struggle with our “Boy Scout” reputation. Other companies thought they could infringe our patents with impunity—and over the years it made litigation more expensive. Now we have a rather aggressive defensive posture—and also a rather aggressive offensive posture in certain areas—to protect our patents through litigation.

In addition Fox notes:

There are some neophytes out there who hear about intellectual property management and suddenly say “Wow, I've got a patent—I'm going to go out and assert it!” And the next thing they know is that they get sued on counter claims by the party they asserted against and they get embroiled in a huge legal battle that may be difficult to get out of. For example, Xerox sued HP a couple of years ago on a single inkjet patent and they asked for a lot of money. So we went through our portfolio and found a patent they infringed and we sued them back. Then Xerox went back into their portfolio and found another patent they thought we infringed and sued us. All in all there were six lawsuits pending before we got finished with it. And there would have been more had we not settled it, because we could have gone on endlessly based on all the patents we could choose from. A large, broad, and deep portfolio is really useful in those kinds of situations.

The goal of enforcement is for the company to create a reputation of willingness to litigate, balanced with an awareness of the rising costs of litigation. Often managers' pay is tied to division profitability, so they are reluctant to litigate in case there is a negative impact to the bottom line. Alternatively, the corporation does not want to be perceived as being unwilling to litigate.

Today, patent infringement is an increasingly significant issue, both in number and dollar amount of judgments awarded.18 (See Exhibit 1.8.)

CONCLUSION: BUILDING BEYOND THE DEFENSIVE LEVEL

Defense is necessary and desirable. Indeed, as a basis for future activities, defense can be a valuable way to gain IP territory for future development. And there are times for any company when the majority of attention and energy must be devoted to defense. But companies should not get “stuck” at Level One, refusing to operate outside it. Instead, they should use defense pragmatically, as one of many activities.

The five best practices in defense described in this chapter—taking stock of what you own, obtaining patents while ensuring design freedom, maintaining patents, respecting the rights of others, and being willing to enforce your patents—all can help a company stake a claim in its own future.

Claim-staking is a wise move for all kinds of companies—not just the companies with a high percentage of intangibles on their balance sheets. True, intangibles-rich companies are more successful in the current environment, as noted in our introduction. But this is partly because the managers of these companies spend the necessary time and energy creating or acquiring those intangibles, and then claiming and protecting them in order to develop them.

Any company can do this! Returning to our opening metaphor of a gold rush, it is useful to note that James Marshall, the man first credited with spotting gold in California, spotted it while on the job in a sawmill. He recognized its value, and immediately reported it to his employer. The rest is history.

In a similar vein, the “sawmills” of today need to be on the lookout for intellectual assets. We will see this more clearly in the next five chapters as we move beyond Level One defensive activities to review activities in the other levels: Level Two (cost control), Level Three (profit center), Level Four (integration with other operations), and Level Five (visionary).

Yes, even sawmill businesses and similar “old economy” businesses have assets that require protection. In fact, ICMG cofounder Patrick Sullivan often tells the story about a client of his:

The CEO of a forest products company once lamented to me about the lack of intellectual capital in his industry. He defined intellectual capital as some form of sophisticated technology. In an effort to impress me with his company's attempts to fill this IC void, he told me that his firm had recently purchased and installed some sophisticated computer-controlled machinery for milling logs, but that it had been unable to produce the same amount of usable lumber per log as the company's human sawmill operators. When I pointed out to him that the mill hands and their knowledge and know-how were the very essence of intellectual capital for his firm, he looked surprised, and then acknowledged that he had never considered intellectual capital in that way.

As in the “gold rush” that started more than a century and a half ago, the most important step is protection—the staking of a claim. So before going off into your next “gold rush,” make sure that your company has staked its proper claims. Like James Marshall of Sutter's Mill, and like Thomas Edison—who followed in Marshall's claim-staking footsteps—keep your eyes open for hidden value, and then secure ownership of that value for a more prosperous future. To build that future, continue on the journey toward the boardroom, moving to the next step, cost-cutting.