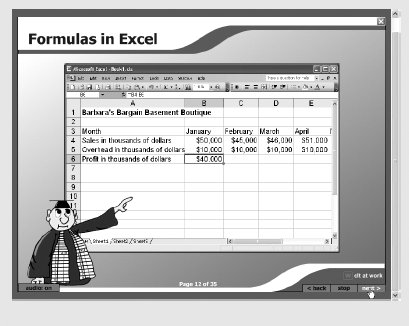

Imagine that you are developing an e-lesson on how to use a computer application such as how to input a formula into a spreadsheet. You've designed an animated demonstration showing how to activate the correct cell in the spreadsheet, type the formula in it, and press enter to see the result. You could explain the animated demonstration with either on-screen text or with audio narration. Which would be more efficient? What research do we have about the best ways to use visuals and audio for performance and for learning?

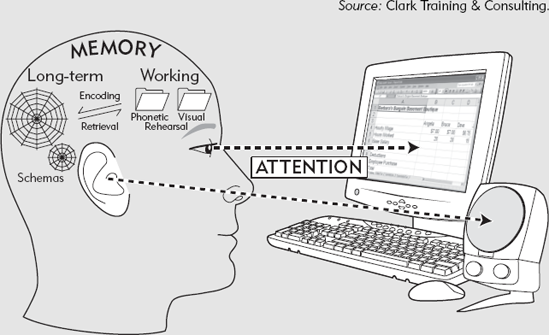

As we have discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, cognitive load refers to the amount of work imposed on working memory. One factor that determines cognitive load is the complexity of the content—what instructional scientists call element interactivity. Complex content or instructional goals require learners to devote working memory capacity to coordinate multiple elements. For example, when learning from instructional materials that teach a new computer application like Excel, you must coordinate several actions on the keyboard and mouse with the screen formats. One way to accelerate expertise when your instructional goals involve coordination and integration of several elements is to exploit two subcomponents of working memory: the auditory (phonetic) center and the visual center. This is the first of three chapters on how to best make use of auditory and visual modalities to extend the limited capacity of working memory.

In this chapter we will look at evidence-based ways to accelerate learning through judicious use of visual modalities including graphics and diagrams as well as auditory modalities such as narration. Our guidelines regarding diagrams apply to any instructional medium that can display visual information including computer screens, white boards in physical or virtual classrooms, and workbooks. Our guidelines regarding audio apply to any instructional medium that can deliver sound including instructors in classrooms, computers used for e-learning, and video. We begin with evidence-based guidelines for the best use of visuals followed by a discussion of how to maximize learning by describing visual information with audio narration.

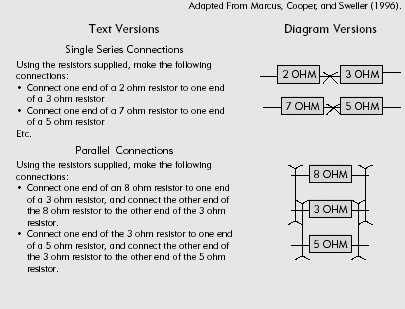

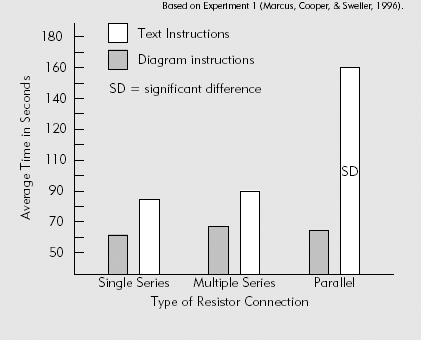

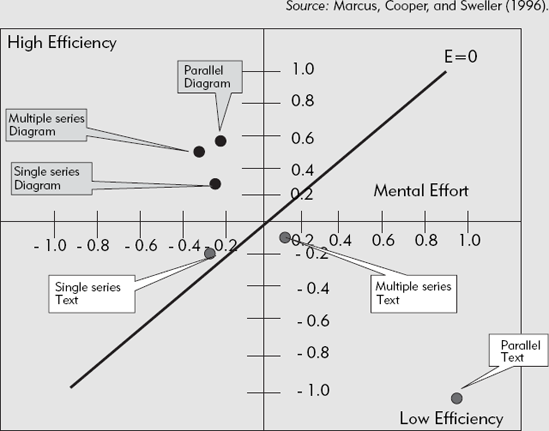

Whether assembling your child's bicycle or clearing a jam in the copy machine, all of us have faced tasks requiring us to manipulate objects. Commonly we refer to working aids with instructions to help us complete these kinds of tasks. Under what circumstances do diagrams aid performance on such spatial tasks? Research shows that we perform spatial tasks faster when we refer to self-explanatory diagrams than when we refer to text descriptions. This guideline applies primarily to individuals who are new to the task and to tasks involving relatively complex spatial relationships.

The research supporting Guideline 1 shows that performance aids using diagrams are more efficient than aids using text. In other words, diagrams can serve as psychological equalizers by allowing you to complete high complexity tasks in about the same amount of time as low complexity tasks with less mental effort.

What is it about diagrams that make them easier to process psychologically? All elements in a visual can be viewed simultaneously, unlike sentences, which must be processed sequentially one at a time. This leads to a lower visual search for tasks that involve coordination of multiple spatial elements. Greater psychological processing efficiency is the result. Likewise, diagrams provide more explicit representations of spatial tasks. A diagram requires fewer inferences because it shows spatial relationships that must be inferred from textual descriptions (Larkin & Simon, 1987). There is a closer correspondence between the diagram and the requirements of the task.

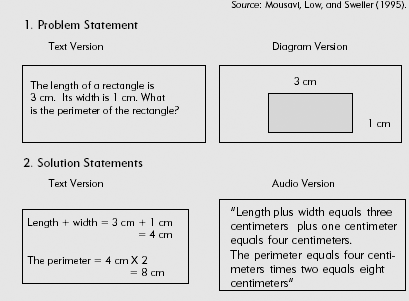

For Guideline 1, we reviewed evidence that working aids for assembly tasks that used diagrams resulted in faster performance than aids that used textual instructions. The focus in that section was performance, rather than learning. In other words, the goal was to accomplish a task while using the aid, rather than to store new knowledge or skills in memory. Guideline 2 rests on evidence that diagrams support learning of content involving spatial relationships better than text does.

Taken together, the research supporting Guidelines 1 and 2 tells us that:

Diagrams enhance performance and learning efficiency.

Diagrams lead to greatest efficiency for spatial tasks of medium to high complexity.

For tasks of lower complexity, text representations are usually less expensive to produce and are as efficient for performance aids and instructional materials.

We recommend diagrams for both performance aids and for training materials in most situations.

So far we have seen that materials with diagrams alone can serve as better performance or learning aids than materials with text alone, especially with more complex content. Guideline 3 is concerned with problem-solving instructional goals that require a deep understanding of the content.

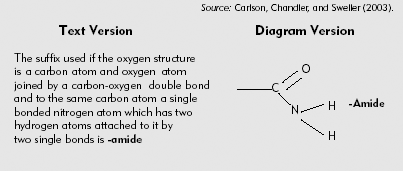

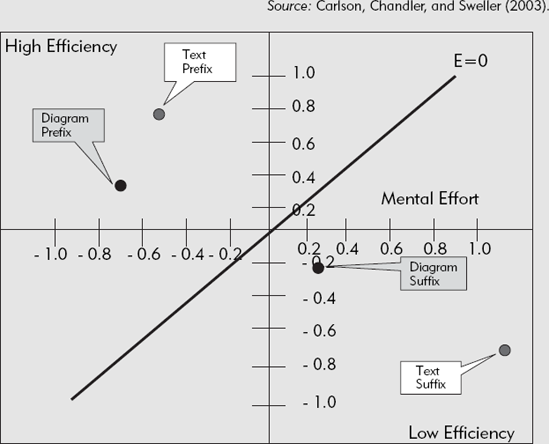

Workers are often faced with challenging situations that require some degree of problem solving. For example, when troubleshooting equipment or when writing employee performance appraisals, workers must generate somewhat novel solutions to each situation. In order to perform novel tasks effectively, the worker must be able to call on a schema of sufficient flexibility that it can be applied to a variety of situations. For example, in a troubleshooting task, to isolate the fault the worker must apply knowledge of how the system works, along with a systematic troubleshooting process. A number of studies have shown that adding a relevant visual to explanatory text helps learners build a deeper understanding of the content that will aid problem solving.

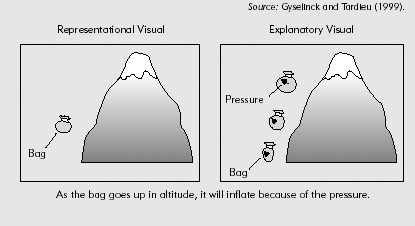

Not all visuals are equally effective. Different types of visuals are best suited for various instructional goals (Clark & Lyons, 2004). For example, a representational visual is a diagram that illustrates the appearance of an object. In contrast, explanatory visuals show relationships among the content elements. Some examples of explanatory visuals include organizational maps and bar charts to show qualitative and quantitative relationships and interpretive diagrams to illustrate abstract relationships and principles. When the learning goal requires a deep understanding, explanatory visuals that show relationships work best.

As we discussed in Chapter 2, expertise is based on a rich bedrock of schemas resident in long-term memory. Schemas are formed when new information entering the eyes and ears is integrated into prior knowledge. This process is called encoding. According to a theory called dual encoding, learning can be deeper when participants have multiple opportunities to encode information.

When studying materials such as those on the right side of Figure 3.8, learners have the opportunity to encode information in two ways—through the words and through the visuals. Learners read the words and view the visual and then integrate those two sources of information into a coherent explanation. Learners have two opportunities to build a new schema: one from the text and one from the visual representation. However, the extra work imposed on working memory to integrate the two sources of information will increase the cognitive load of materials that include text and related visuals.

Since the added load results in deeper learning, this is a form of useful load—the kind we called germane. Since these types of lessons are more demanding of limited working memory capacity, we need to offset this germane load by finding ways to present the visuals and the words in the most cognitively efficient manner possible. We will look at ways to do this under Guideline 4 and in Chapters 4 and 5.

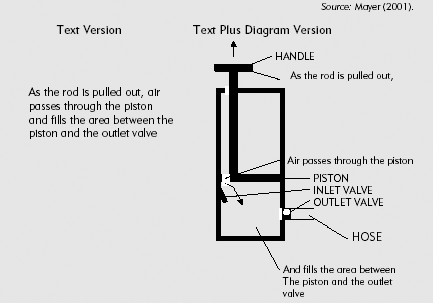

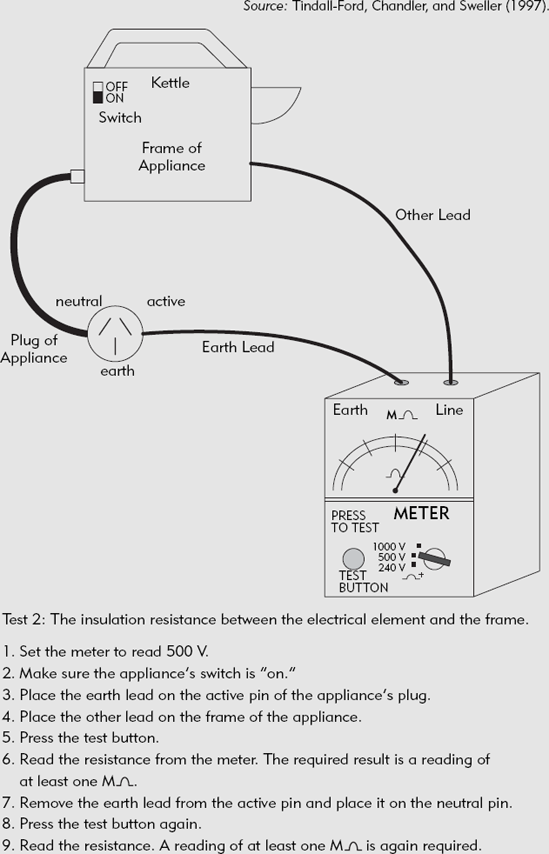

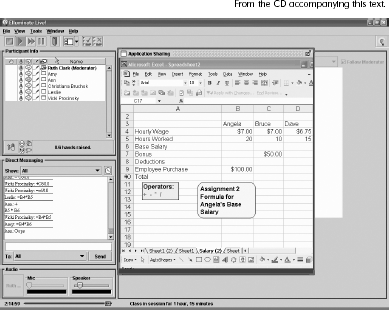

One way to reduce load imposed by the need to coordinate visuals and words is to divide the new incoming content among the two storage areas in working memory—the visual and the auditory. In our CD asynchronous demonstration lesson on creating Excel formulas, our default version uses audio narration to explain animated demonstrations. However, if the delivery platform does not have sound capability or some learners have hearing impairments, the audio can be turned off and is replaced by on-screen text. Research has indicated that the default version using audio narration results in more efficient learning. Cognitive efficiency gained when visuals are explained by auditory narration is referred to as the modality effect.

Taken together the research supporting the modality effect tells us that:

When a visual requires an explanation, learning is more efficient when the explanation is provided with audio narration rather than with text.

Both still and animated visuals benefit from an audio explanation.

Providing content in a complementary visual and auditory format reduces cognitive load by dividing content between the visual and auditory centers in working memory.

Of course not all situations lend themselves to using audio, and research shows that, even when it is available, it is not always beneficial. We recommend that you describe diagrams using audio narration rather than text when: (1) the delivery medium can support audio; (2) learners are not hearing impaired; (3) the instructional goal requires higher levels of mental work; (4) learners are novice to the skills being trained; (5) the diagram and/or text require an explanation; and (6) learners will not need reference to the content. In this section we discuss each of these conditions that will influence your decision to use audio narration.

Naturally your delivery medium has to be able to carry audio. Probably the two most common settings where audio can be used to describe visuals are multimedia training delivered on computer and instructor-led training either in actual or virtual classroom sessions. For example, in a synchronous web cast, learning is most effective when the instructor explains a relevant visual, as shown in our Excel virtual classroom lesson on our CD. If the instruction is delivered in books, you will most likely want to use other proven methods to effectively reduce load. We describe these in the next chapter.

Many organizations require that all training programs accommodate learners with visual and auditory impairments. For these situations, secondary text explanations should be available to replace the audio. As we will see in Chapter 5, you should not present the same explanations in both audio and text simultaneously. Identical text and audio are redundant and depress learning by overloading working memory with unnecessary information.

Audio narration will be most helpful when the cognitive load is highest. If the instructional goal and/or content are relatively simple, presenting words with text will be as effective for learning as presenting words with audio narration.

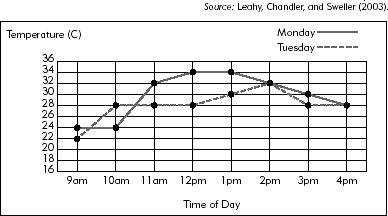

For example, consider the graph shown in Figure 3.12. Suppose you were asked to find the average rate of temperature change on Tuesday between 12 p.m. and 2 p.m.? How much mental effort would you need to answer this question compared to finding the times on Monday that had a zero average rate of change? In order to find a time that has a zero average rate of change for any given day, the student needs only to locate the correct day and look at the time periods for a flat line. In contrast, in order to find an average rate of temperature change for a given day and time the student must (1) locate the correct day, (2) locate the first time period, (3) identify the temperature for that time, (4) locate the second time period, and (5) identify the temperature for that time. Next the student must (6) subtract the lowest temperature from the highest temperature, (7) subtract the earlier time from the later time and divide the answer for Step 5 by the answer for Step 6. As you can see, the average rate of change question requires you to identify a number of different variables on the graph and to perform several mathematical operations. In contrast, the zero rate of change question only requires you to identify straight line segments and associate them with specific hours.

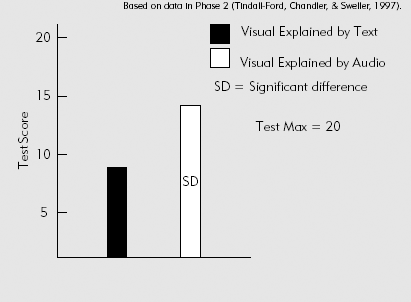

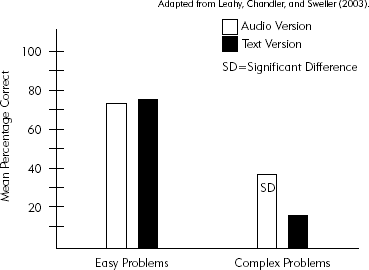

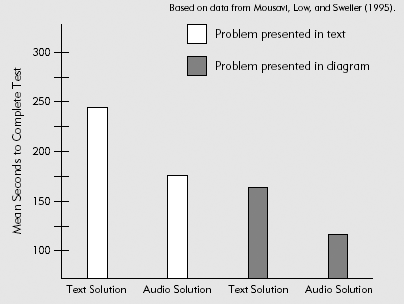

Leahy, Chandler, and Sweller (2003) compared a text explanation with an audio explanation of this graph on high and low complex questions such as the ones we just described. Figure 3.13 shows the results. As you can see, there are no real differences for the easy questions. As we would expect, the audio version helped learning on the more complex operations and had little effect on questions that did not require much mental effort.

A third factor to consider is the experience of the learner. Novices are most subject to cognitive overload. As learners gain experience, we would expect that the modality effect would taper off. In fact, Kalyuga, Chandler, and Sweller (2000) found that, as learners became more experienced as they progressed through a series of lessons, the effectiveness of the audio versions decreased. Once learners were quite experienced, the diagram alone was the most effective treatment. At this point, the experienced learners understood how to use the diagram and adding audio explanations was counterproductive. This is another demonstration of the expertise reversal effect that we describe in Chapter 10.

Naturally, audio narration will reduce load only in situations in which the language used in the instruction corresponds to the native language of the learner. In cases in which there is a mismatch in delivery and native language, a text version is likely to impose less load.

Note that the superiority of audio-visual instruction over visual-only instruction (the modality effect) is only obtainable when neither the diagram nor the text can be understood without the other. For example, in our Excel demonstration lessons on the accompanying CD, neither the visual animated demonstration nor the descriptive words is self-explanatory. Learners need both for understanding.

You will need to apply different guidelines when, for example, a text redescribes a diagram that is self-explanatory. In these situations the text and the diagram become redundant. We describe how to deal with this situation in Chapter 5.

Although audio explanations of a relevant visual can reduce extraneous cognitive load, there are times that presenting information in audio might add extraneous load. Because audio is a transient modality, any content that must be referenced during the training should be available in a text format. Directions or data needed to complete an exercise are two common examples. For example, in our demonstration Excel virtual classroom lesson on the CD, the instructor writes the exercise directions on the spreadsheet for learners to reference, as shown in Figure 3.14.

All of the studies we've described on the modality effect so far focused on the use of audio to explain diagrams. However, the same benefits are realized when the material being explained is in the form of text. If you have written text that requires an explanation, it is better to provide the explanation in spoken rather than written form.

There are solid research and psychological reasons for recommending that you:

Use diagrams in place of text to support performance of tasks involving spatial relationships when the diagram is self-explanatory

Add explanatory diagrams to words when the goal is to help learners build a deep understanding

Explain visual content—either diagrams or text with words presented in audio narration when the tasks or content is complex

All of the above recommendations apply to workers or learners who are novice to the task or content as well as to tasks that are more complex.

Chapter 3: Using Visuals and Audio Narration. John describes the best techniques for display and explanation of spatial information using graphics and audio.

The asynchronous lesson illustrates effective use of visuals, audio, and text.

Note the use of:

Relevant visuals to illustrate procedures.

Audio narration as the default modality to explain visuals.

Text on screens that require learner responses.

The synchronous lesson Virtual Classroom Example illustrates effective use of visuals, audio, and text, including instructor explanations of relevant visuals on the white board and use of text to display directions.

In this chapter we have summarized basic guidelines for use of visuals and explanations of visuals using audio narration in ways that best manage cognitive load. In the next two chapters we will expand on these guidelines. In some cases your delivery medium will not have audio capability and you will have to rely on text to explain visuals. In Chapter 4 we describe ways to manage cognitive load by focusing learner attention to relevant portions of visual or text displays and to avoid split attention by integrating text close to the visuals. In Chapter 5 we review research recommending a minimal display of content needed for understanding. The guidelines in Chapter 5 mitigate against describing a visual with both text and audio.