Can you recall the hours you spent in math courses working practice problems both in class and afterward as homework assignments? Practice exercises matched to the learning objectives are one hallmark of effective courseware. For example, in an early draft of our demonstration lesson on Excel formulas, we assigned learners six different scenarios for practicing constructing formulas. Effective practice exercises that require learners to process content deeply also impose considerable load on working memory. For novice learners who need to devote working memory capacity to building new schemas, working many practice problems slows learning by overloading working memory. The good news is that recent research offers proven techniques to achieve the same learning in less time by starting with worked examples that transition gradually into practice exercises. You will see in our CD demonstration asynchronous load managed e-lesson that we replaced many of our practice assignments with worked examples!

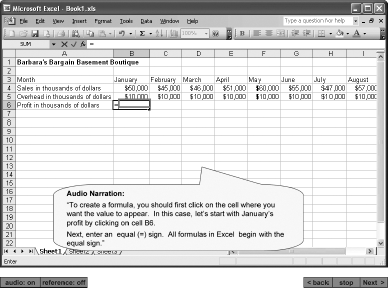

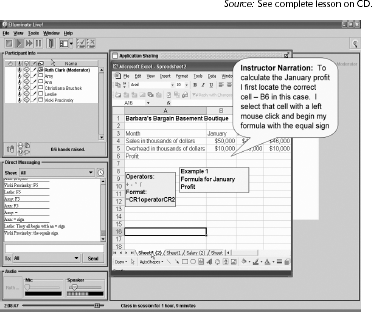

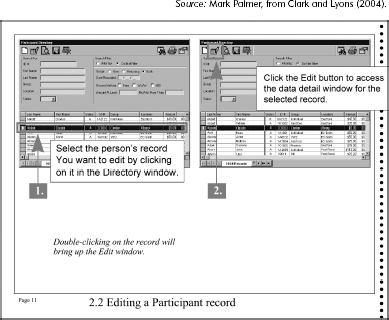

A worked example is a step-by-step demonstration of how to perform a task or solve a problem. For example, Figure 8.1 shows one screen with the beginning of a worked example from our asynchronous Excel formula demonstration lesson on the CD. For procedures, worked examples typically take the form of a demonstration that illustrates the steps to complete the task.

Worked examples may be presented in diverse formats and modalities, including text in books such as the algebra worked example shown in Figure 8.2 or in a narrated animation such as the Excel worked example shown in Figure 8.1. Examples are nothing new, since good instruction has always used them. However, what is new is the proven effectiveness of examples to replace practice and get equivalent learning results in less time and with less learner effort! In this chapter we help you apply four guidelines for design and display of worked examples in ways that will accelerate expertise. You will see how worked examples should be modified as a lesson progresses and your learners gain expertise.

Suppose your lesson ends with eight practice problems that require the learner to apply the lesson guidelines, such as analyze a loan application or construct a control chart. Your practice problems require learners to apply the lesson skills or guidelines to diverse work situations. For example, among the loan applicant problems, some scenarios involve applicants with a previous bankruptcy, while others include diverse income levels. To apply Guideline 17, instead of assigning eight practice problems, you would instead create four worked examples and four practice exercises. We call these versions worked example-problem pair lessons. The lesson alternates worked examples with a similar practice problem. Thus a worked example involving a bankruptcy case would be followed by a practice problem with a different bankruptcy scenario.

While the replacement of some practice with worked examples looked promising, it was important to see whether these findings applied to actual classrooms. The experimental lessons described previously were quite brief—lasting approximately forty minutes. How would worked examples fare in an actual classroom with longer lessons and different topics? Zhu and Simon (1987) report one field trial conducted in Chinese middle schools in which a traditional three-year course consisting of two years of algebra and one year of geometry were successfully completed in two years by replacing some practice with worked examples! Here we see real-world evidence of acceleration of expertise through a cognitive load reduction technique.

In summary, the laboratory research showed that learning time could be saved under controlled conditions by substituting some practice with worked examples, and the field trials showed that this technique could be adapted to actual classrooms.

It comes as no surprise that actively solving practice problems imposes much more mental work than reviewing worked examples that illustrate how to solve those problems. When studying worked examples, limited working memory capacity can be devoted to building a schema of how to perform the task. Having a worked example to study just prior to solving a similar problem provides the learner with an analogy available while solving the problem. When having to actively solve a problem without the benefit of an analogous example, most working memory capacity is used up in figuring out the best solution approach, with little remaining for building a schema.

Paas (1992) found that worked examples were superior to straight practice for learning of statistical concepts mean, median, and mode. As part of his experiment he asked the participants to rate the amount of invested effort on a scale ranging from very, very low to very, very high. Not surprisingly, participants rated the lessons with worked examples as significantly less difficult than the lessons with all practice, which suggests that the benefit of worked examples is due to reduced cognitive load.

Although the use of worked examples to replace some practice proved effective in a number of experiments, there is a potential drawback to worked examples. To be effective, a worked example must be studied. An example ignored won't promote learning. Some learners may be tempted to either skip the worked examples completely or to give them a cursory review and thus miss the benefits they offer. In contrast, practice problems demand deep processing for solution. In fact, many practice assignments ask learners to "show their work" as evidence of this deep processing. Deeper processing leads to better learning. One way to minimize learners ignoring worked examples is to replace worked examples with completion examples.

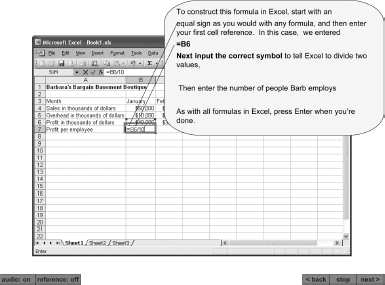

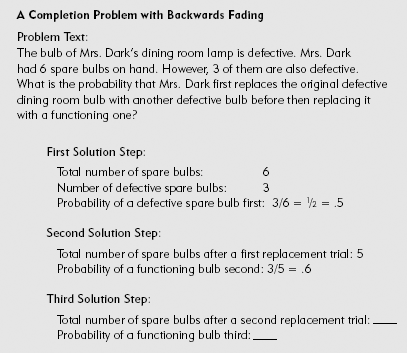

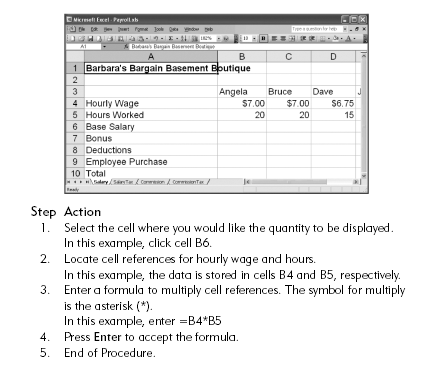

A completion example is a hybrid between a practice assignment and a worked example. In a completion example, some of the steps are demonstrated as in a worked example and the other steps are completed by the learner as in a practice problem. Figure 8.3 shows an Excel worked example from our CD converted to a completion example. The first step is done for the learner, and the learner must complete the next step himself. In order to complete the problem, the learner will have to actively process the worked out portion and then overtly respond to the open portion.

Like worked examples, completion examples reduce cognitive load because schemas can be acquired by studying the worked-out portions. Requiring the learner to finish the worked example ensures that she will process the example deeply. Research has shown that learners who process examples more deeply learn more. Chi and her colleagues (1989) asked college students to talk aloud as they studied worked examples of physics problems. They compared the "self-talk" of students who scored higher with those who scored lower on a test. They found that the high scoring learners had not only more self-explanations but that the quality of their self-explanations was better.

The more effective self-explanations:

Focused on when and why physics solution equations were used

Connected specific solution steps to the problem

Included more self-monitoring such as: "I don't see why this example used this equation at this stage in the solution"

In summary, a completion example offers psychological balance. It reduces cognitive load by incorporating some worked-out elements and it fosters deep processing by requiring completion of the remaining elements.

So far we have seen that you can increase the efficiency of your lessons by replacing some practice with either worked examples or completion examples. This technique manages cognitive load of novice learners by freeing up working memory capacity to build new schemas by study of examples. However, as learners gain expertise during their training, eventually worked examples actually become detrimental and learners are better off with lessons in which they work all the problems. This is because once a learner has acquired a basic schema for the skill or concept, he learns best by applying the schema to problems, rather than investing redundant effort in studying more worked examples.

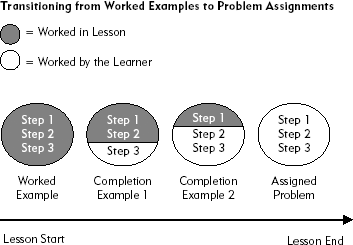

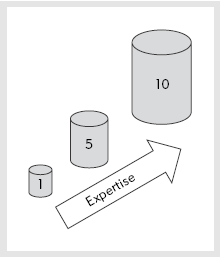

The best way to accommodate learners as they build expertise is through a process called backwards fading of worked examples. In lessons that apply backwards fading, worked examples transition gradually into practice problems coincident with a gain in learner proficiency. Fading techniques allow you to accommodate a gradual learning process. Initially learners should devote as much working memory capacity as possible to building a schema that will underpin the new skills. As they gain expertise, understanding is promoted as they do more and more work. In more advanced stages of learning, learners need to build high competency levels by solving many practice problems themselves.

Fading is a process in which completion examples evolve into full problem assignments by a gradual increase in the number of steps that must be completed by the learner. The lesson begins with a full worked example that provides a model for the learner. The next few worked examples are completion examples in which more and more of the work is done by the learner. By the end of the lesson, full problems are assigned.

Figure 8.4 shows a faded completion problem from our asynchronous Excel lesson on the CD. In this example the instruction fills in the first step and the learner completes the remaining three steps. A faded worked example sequenced just prior to this one would demonstrate how to complete the first two steps and then ask the learner to complete the last two steps. In backwards fading, the instruction fills in the first steps and the learner finishes the problem starting from the end. Thus in a five-step problem, the first completion problem shows Steps 1 through 4 worked out and the learner fills in Step 5. In the next completion example, Steps 1 through 3 are worked out and the learner fills in Steps 4 and 5. At the end of the sequence, the learner is solving a full problem. Figure 8.5 conceptually illustrates backwards fading. As you can see, a sequence of examples (circles) requires greater and greater learner input (white portion of circle) to complete. In this way, instructional support is faded gradually as the learner gains expertise.

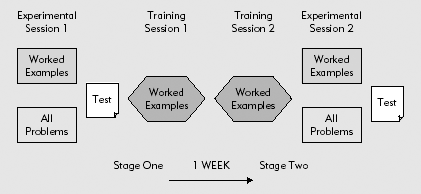

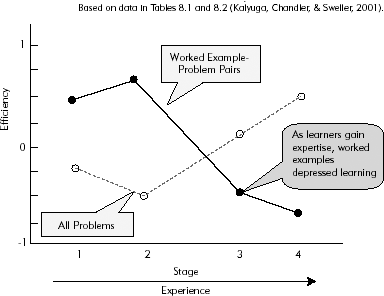

As you can see in Figure 8.7, the worked example-problem pair lessons resulted in more efficient learning during initial stages of learning. This result replicates the beneficial effect of worked examples problem pairs that we summarized previously. However, as the learners gained experience, the all-problem lessons became more efficient. That is, they yielded equivalent or better learning with less effort. The authors conclude that: "Differing levels of learner experience should be taken into account when designing instruction using worked examples and problems. A series of worked examples should be presented first. After learners become more familiar with the domain, problem solving (as well as exploratory learning environments) can be used to further enhance and extend acquired skills" (p. 588). Instructional methods that manage load effectively for novices are no longer needed once learners gain more expertise. We discuss the changing needs of experts in greater detail in Chapter 10.

The research reviewed in the preceding paragraphs suggests that novice learners who are most susceptible to cognitive overload will benefit the most from worked examples. As learners gain expertise, worked examples can actually depress learning because it requires more mental effort for an experienced learner to study a worked example than to simply work a problem herself. This is because a learner who has built a schema for working problems can best solidify his or her schema by exercising it. Having to study a worked example, once a schema has been established, becomes a redundant mental activity and learning is disrupted. We discuss the adjustments you need to make as learners gain expertise in Chapter 10.

Taken together, the experiments on worked examples recommend that you:

Begin your lessons with worked examples followed by a similar problem.

Follow the first worked example with a series of completion examples in which the first steps are worked out and the final steps are left for the learner to complete.

End the lesson with full practice assignments.

This transition from worked example to practice by way of backwards faded completion examples provides learners with a smooth trajectory from novice to expert.

We have seen that worked example-problem pairs and completion examples are more efficient vehicles for learning than assigning all problems. However, a poorly formatted worked example can add extraneous cognitive load and thus negate its potential benefits. To be effective, worked examples should be formatted in ways that minimize cognitive load.

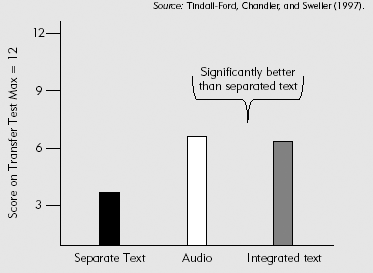

In Chapters 3 and 4 we discussed the use of audio (modality effect) and use of integrated text formats that minimize split attention. The modality effect applies to multimedia or classroom instruction and recommends that you describe on-screen visuals with words presented in audio narration rather than with text. Presenting content in complementary visual and auditory modes distributes the load between the visual and auditory storage centers of working memory. The use of integrated text applies to either multimedia or paper-based materials and recommends that text that describes visuals be physically integrated nearby the visual. This reduces visual search by doing the integration work for the learner. These principles apply to worked examples that use visual illustrations.

Figure 8.9 shows a screen capture from our demonstration Excel virtual classroom e-lesson on the CD. In this segment of the lesson, the instructor describes how to enter a correct formula while demonstrating the procedure in the application. The use of audio that describes the actions demonstrated in the application sharing window minimizes load for novice learners.

If the same procedure is being presented in a paper medium, words must be presented in text. Figures 8.10 and 8.11 contrast an effective and ineffective way to explain such a worked example. The efficient example (Figure 8.10) integrates the steps into a visual that uses the two-page spread of the book to show the application screens. The inefficient example (Figure 8.11) explains screens with words in text placed under the visual that require the learner to expend extra mental effort to do the integration himself.

Audio narration is more transient than text. When using audio to describe a visual, we recommend that some form of visual cueing be used to draw the eye to the portion of the visual being described by the audio. Jeung, Chandler, and Sweller (1997) found that when the visual component of the instruction is complex and it is explained by audio, it was only effective when a cueing device such as color, an arrow, or subtle animation was used. For example, in our asynchronous Excel lesson on the CD we used a red circle to draw attention to the portion of the spreadsheet being explained. In the virtual classroom lesson on the CD, the instructor used a highlighter to focus attention to the relevant portion of the spreadsheet. Second, when you are using faded completion examples, present the example with integrated text rather than audio so the learners can refer to it as they finish it. You will note in our asynchronous CD demonstration lesson that our full worked examples are described with audio narration, whereas our completion examples are presented with on-screen text.

There are solid research and psychological reasons for recommending that you:

Help novice learners build robust schemas by pairing worked examples with practice assignments.

Ensure that learners study worked examples by using completion examples.

Transition gradually from worked examples to full practice as learners gain expertise.

Use backwards faded completion examples to transition from worked examples to practice.

Format worked examples in ways that manage cognitive load in multimedia through audio narration of steps and cueing of related visuals and in print media through integration of text nearby the visual.

Format completion examples with text that is integrated into the visual to avoid split attention.

Chapter 8: Transition from Worked Examples to Practice to Impose Mental Work Gradually. John describes the best ways to use worked examples in training followed by a description of how examples should be altered as learners gain expertise as well as how to display worked examples effectively.

In the Load-Managed Excel Asynchronous Web-Based Lesson note the following:

Each topic begins with a worked example and progresses to completion examples and then to full practice assignments.

Full worked examples are described with audio narration; completion examples and practice are described with on-screen text.

Full worked examples described with audio narration are cued with red circles to help learners see the relevant portions of the spreadsheet as they are described.

On-screen text explaining examples is aligned close to the relevant portions of the spreadsheet.

In the Virtual Classroom Example note the following:

Worked examples are explained by instructor narration.

The instructor engages all learners in completion examples by ask them to respond in the chat window.

Practice problem directions remain in text on the screen.

In Part II of the book, we have summarized a number of proven techniques for reducing extraneous cognitive load in your instructional and performance support materials. Reducing extraneous cognitive load increases instructional efficiency so learning can be faster. But the real reason to reduce extraneous load is to free working memory capacity for more effortful mental processing that results in better learning. Cognitive load that results from instructional strategies that augment learning is called germane load.

Part III of the book includes Chapter 9, in which we continue our story about worked examples as we look at ways to use worked examples to increase germane load and thus improve learning. It also discusses germane load that arises from rehearsals that lead to automaticity of new schemas.