In 1972 an Eastern Airlines flight crashed in the Florida Everglades as a result of cockpit distractions. The crew became so preoccupied with a malfunction that no one noticed the altimeter reading or warnings until it was too late to make a correction. While attention failures during learning will not have as severe consequences, the loss in instructional efficiency from instructional environments that fail to support attention can be costly.

Sternberg (1996) defines attention as "the phenomenon by which we actively process a limited amount of information from the enormous amount of information available through our senses, our stored memories, and our other cognitive processes" (p. 69). Attention helps learners filter out irrelevant data and focus on the important elements in the instructional environment.

There are two sides to the coin when it comes to supporting attention during training. On the one side, you can use instructional methods called cues and signals to direct attention to the important elements of the training. On the other side, you can use instructional methods to minimize extraneous cognitive load arising from split attention. In this chapter we will look at evidence-based ways to do both in order to free up as much working memory as possible for learning processes.

Support for attention will be most important when the learners are novices, when the learning content is complex, and when the training materials are presented dynamically, requiring immediate processing. A narrated animated sequence presented in a multimedia lesson as well as a classroom lecture are two examples of dynamic delivery formats. Both deliver content at a rate outside of the control of the learner and demand extra attentional support. In contrast, content presented in a workbook is static and typically can be reviewed and revisited at the learner's own pace.

Guideline 5 recommends the use of cues such as arrows and lines to draw attention to critical portions of complex visual displays as well as signals such as italics or vocal emphasis to draw attention to important words or sections presented as text or as audio narration.

Because audio explanations are transient, extra cuing of related visuals is needed when the visuals are complex. Whether teaching in the classroom or online, the use of highlighters, red circles, or arrows are common methods used to direct learner attention to a relevant section of a complex visual display.

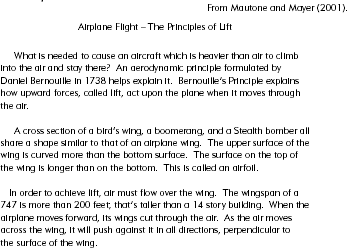

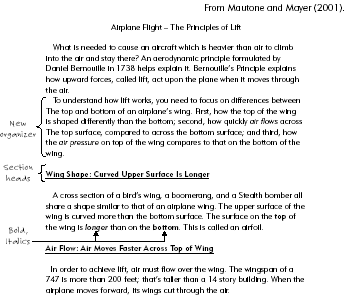

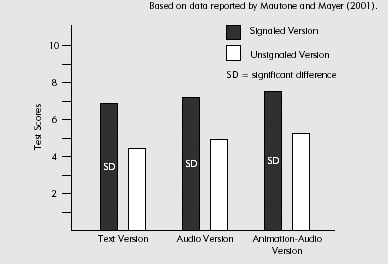

From Ezines to email to traditional print publications, professionals are inundated with textual information. One way to help readers find and process textual information efficiently is to provide signals. Signals in text are analogous to arrows and circles used to focus attention in visual displays. Signals include paragraph headings, bolding and italicizing of important words, signal phrases, and topical overviews written as content previews. A signal phrase is a short sentence or two that explicitly points out the relevance of the words to follow such as: "The following four methods are the most significant among the many techniques researched." To see some examples of signals, compare a section from an unsignaled and a signaled text on airplane lift shown in Figures 4.1 and 4.2. In the signaled version italics and bolding draw attention to individual words. Paragraph headers are used to alert the reader to the new topic. In addition, the writer added two sentences as organizers just prior to the main text content.

Research studies have demonstrated that signals are most useful for lengthy and complex texts. Likewise, signals in the form of structured abstracts have been shown to speed reader access to technical information.

Complex Texts Need Signals. Signals will benefit learning when the text is long and complex. Lorch and Lorch (1996) compared learning from signaled and unsignaled texts—half of which were simple and half complex. They found that signals did not influence learning from simple texts but were beneficial for more complex texts. Simple texts do not need extra attentional support to make sense, as working memory can readily process unsignaled simple texts. In contrast, more complex texts make additional demands on working memory and adding signals helps to offload some of those demands.

Of course, we need to keep in mind that what constitutes simple or complex material will depend not just on the material but also on the expertise of the learners. With relatively high levels of expertise, signals that aid novices may be redundant for more knowledgeable learners. Chapter 10 discusses how to adjust training materials for learner expertise.

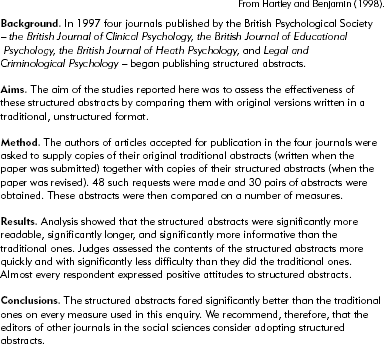

Signals Aid Access to Technical Information. Signals in the form of structured abstracts can also speed reader access to a series of texts written by different authors. Figure 4.4 shows a structured abstract from research reported by Hartley and Benjamin (1998) that compared the readability of structured with unstructured journal article abstracts. The structured abstract uses bolded section heads to focus attention to each section of the abstract. As a whole, the structured abstract provides an organizer for the body of the article. If all authors use the same structure, all abstracts will be more consistent.

Hartley and Benjamin (1998) found that structured abstracts offer readers more information in a more accessible form than do unstructured abstracts. In an age of high information density, knowledge workers must routinely skim large quantities of text materials. A structured abstract preceding a long technical article serves as a gateway into the article by helping the reader quickly determine whether the article is relevant to their needs and also by providing a preview of the article.

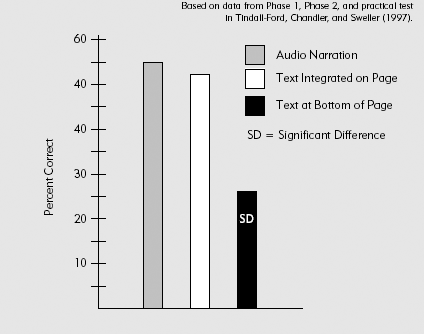

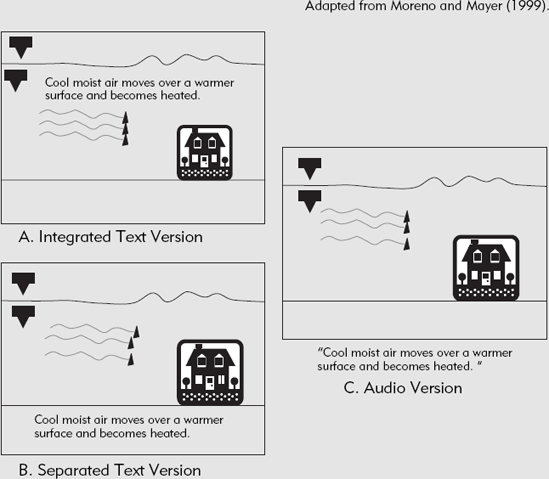

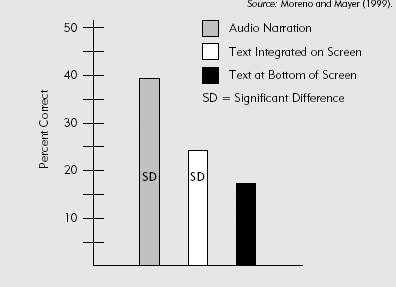

Have you ever read a book in which the text describes a visual located on the back of the page? In order to make sense of the information you need to read the text, turn over the page to study the visual, and then turn the page back again to review the text. The annoyance you feel is your working memory complaining about extraneous cognitive load needed to search for and integrate related information that is physically separated. When dependent information is laid out in separate locations, additional mental energy must be devoted to integrating the separated information sources. This additional mental effort caused by split attention takes a toll on limited working memory capacity and increases extraneous cognitive load of the materials. Learning complex information is degraded when studying materials that lead to split attention.

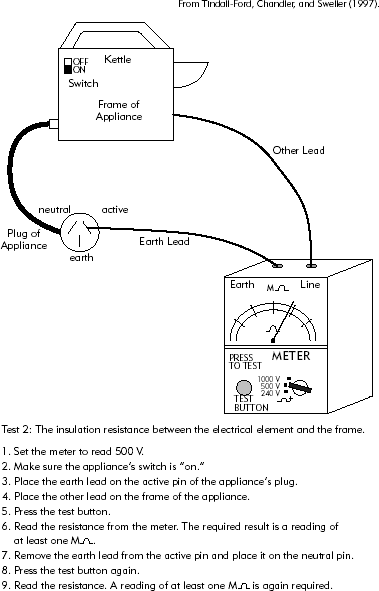

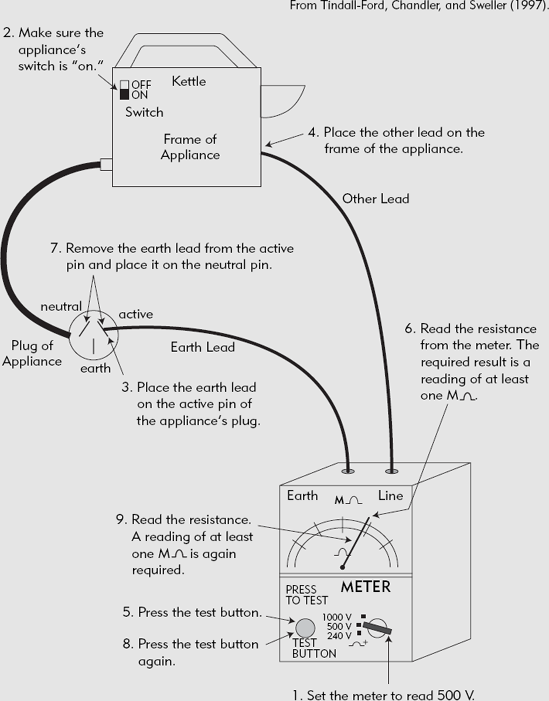

Split attention occurs when two mutually dependent visual sources of information are laid out in a format that requires the learner to mentally integrate them. Split attention frequently arises from training materials in which a step-by-step text procedure for equipment or computer operation is displayed at a distant location from a visual of the equipment or application screen. An example is shown in Figure 4.5. Here, the text under the diagram lists nine steps for conducting an electrical test on the kettle. Neither the text nor the diagram is self-explanatory. To make sense of the procedure, the learner must read the step and then search for the relevant section of the diagram. Searching for referents and then mentally integrating them increases working memory load but does not contribute to learning.

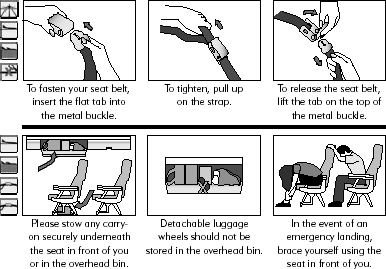

In contrast, when either the text or the visual is self-explanatory, split attention will not occur. For example, the visual on the airline safety card shown in Figure 4.6 is self-explanatory. The reader can perform the procedure simply by referring to the visual. This example would not lead to split attention because understanding the visual is not dependent on reading the text. In fact, as we will see in Chapter 5, the visual alone minus the text would be the optimal way to display this content.

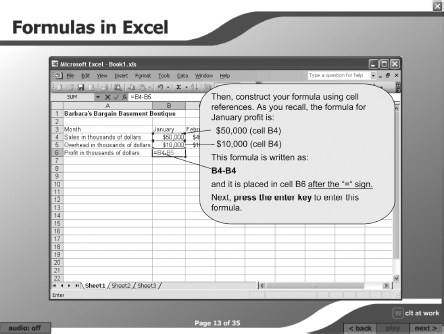

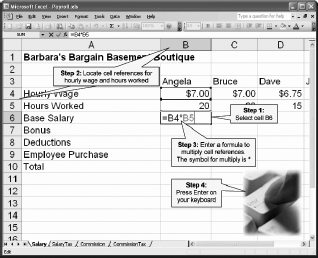

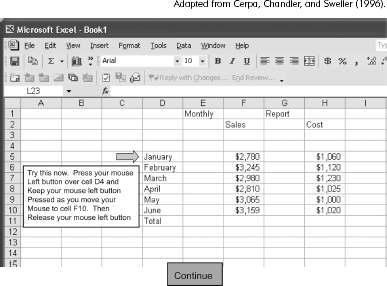

Instructional layouts that lead to split attention are quite common. In multimedia for example, mutually referring dependent text and visuals are sometimes placed on upper and lower segments of a scrolling screen or on two different screens. Likewise, it's common to place explanatory text in the corner or bottom of the screen physically distant from the visual display. When describing on-screen visuals with dependent text, place the text near the relevant portion of the visual and, when needed, use cues to link specific text to different elements in the visual display. For example, in our asynchronous Excel e-lesson on the CD, we inserted lines from specific sentences to the relevant portion of the spreadsheet, as shown in Figure 4.12. These types of integrated layouts are most important when explaining complex tasks.

Although we have emphasized alignment of visuals and text in our discussion, the split attention principle also applies to two sources of mutually referring text. For example, text may be needed to present a scenario or factual data for an online case study or text may be used to present feedback to on-screen text questions. In all cases, the screens should be designed to place related information in an integrated format. Avoid layouts like the one in Figure 4.13 that require the learner to page back to it in order to access information essential to the exercise.

Split attention is also common in training developed for print media. For example, it's common to present procedural steps under (or worse, on a separate page from) related visuals. When planning materials for print-based working aids, workbooks, or handouts, consider the real estate limits and options of your delivery medium. For example, you might want to lay out visuals horizontally across a two-page spread or vertically along the sides of the page. In classroom presentations, you can use wall charts that duplicate commonly used visuals to minimize paging back to those visuals in the training materials. See Clark and Lyons (2004) for additional guidelines on design and layout of visuals in instructional materials.

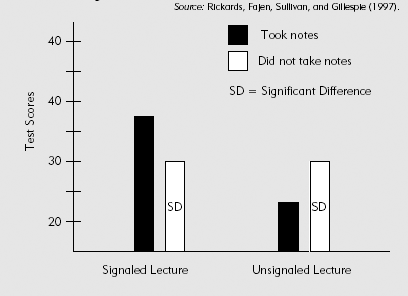

Split attention caused by taking notes from a lecture may reduce learning. The cognitive effort required to take notes reduces mental capacity that could be devoted to processing the content in ways that lead to learning. Note-taking does not benefit higher order learning (compared to recall learning) of older learners (Kobayashi, 2005). We recommend that limited working memory resources be utilized in more productive ways than taking notes from a lecture. For example, written content summaries can be provided to learners and the instructional time used for practice exercises or discussions of the content.

In summary, the research on Guideline 6 tells us that:

Text explaining a visual should be placed near the visual and additional cues such as lines or arrows used to integrate the text to the relevant portion of the visual.

Text and related visuals should not be separated on a page, on different pages or screens.

Note-taking during a lecture demands considerable cognitive resources and should be minimized.

When note-taking during a lecture is unavoidable, use signals in the lecture to minimize split attention.

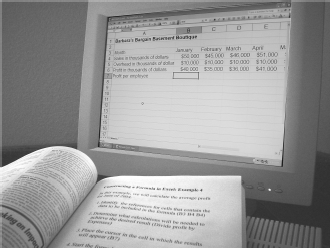

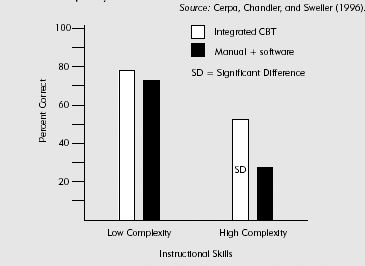

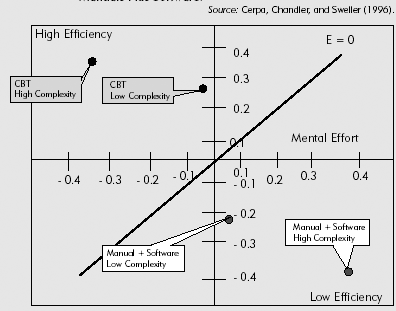

Under Guideline 6 we saw that it's important to place dependent text and visuals near each other on pages or screens to avoid split attention. A common violation of split attention that occurs in training on computer applications or equipment is to present related information in two different media. For example, procedure steps are written in text in a manual and the learner simultaneously applies those steps to a computer or equipment. For example, in Figure 4.14 you see a typical computer training manual that includes steps needed to create a formula in Excel. This layout requires the learner to read each step in the manual, find the relevant portion of the screen on the computer and integrate the two. For a simple step such as "Place the cursor in Cell B2," the cognitive load would not be great and the split manual-computer format would not cause a problem. However, consider a more complex step such as "To calculate projected profit per employee, enter the formula in cell B8 using parentheses to tell Excel to perform the addition first and then a slash to tell Excel to divide the sum by the number of employees. "To apply this step the learner must read the text in the manual, find the correct entry cell on the computer screen, locate the correct cell reference to use in the formula, and apply the order of operations rule. This is a demanding task for a new Excel user, and trying to integrate the text in the manual with the various on-screen elements will add extraneous cognitive load.

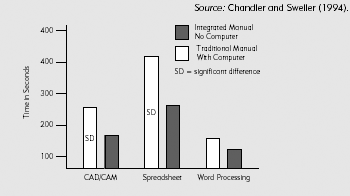

Instead, the instructional materials should perform the integration for the learner by placing all of the content into one delivery medium. In an integrated format either all of the content is placed in the manual and no computer is used or all of the content is placed on the computer screen and no manual is used. Figure 4.15 shows an example of an integrated manual in which all relevant visual and textual information is contained in the manual. Figure 4.16 shows one screen from a lesson in which all of the content is integrated on the computer.

Figure 4.15. A Computer Training Manual That Minimizes Split Attention by Integrating Text and Visuals.

Figure 4.16. A Computer-Based Training Lesson That Minimizes Split Attention by Integrating Text and Visuals on the Computer.

According to Guideline 7, when training computer tasks that involve interactions among several components such as the keyboard and on-screen elements, learning is faster and better when learners study from an integrated manual that is self-contained. That is, the manual includes all the necessary visual and textual information and the learner does not need to divide mental resources between the manual and the computer.

Naturally, any training situation in which acquiring a new motor skill is an essential part of the task will require hands-on practice. Motor skills such as typing or performing surgery cannot be learned by studying a manual. However, in situations for which learners already have the requisite motor skills, that is, they are familiar with manipulations involving keyboards and the mouse, learning computer procedures can be more effective in the absence of the computer!

In our discussion of Guideline 7 to this point, we saw that learning was faster when participants studied computer procedures from an integrated manual with no computer than when they used a traditional manual with hands-on computer practice. Alternatively, you can get efficient learning by integrating all of the instruction on the computer screen.

While the integrated manual and integrated computer-based training both proved more effective for learning than dividing content between a manual and a computer, we recommend that when possible you integrate content on the computer. In our experience, learners are eager to work with the computer as much as possible and many learners will lose motivation if required to learn many computer tasks from an integrated manual without a computer. In addition, most computer training classes incorporate many tasks and insufficient time is available to commit all of the steps to memory by studying an integrated manual. Instead, a more active and motivational environment can be realized by presenting text and visuals on the computer.

Nevertheless, if you do provide a manual, make sure it uses a physically integrated, self-contained format that does not require the equipment to be present.

There are solid research and psychological reasons to recommend that you:

Help learners focus their attention with cues for visuals and signals for text and auditory materials

Use cues and signals when the content is more complex and when the instruction is delivered dynamically, such as in classroom or synchronous e-learning

Minimize cognitive load from divided attention by physically integrating mutually referent content such as text and graphics on the page or screen

Minimize cognitive load imposed by note-taking during lectures by providing learners with content summaries and using class time for learning activities

Minimize cognitive load by integrating computer training on the computer so that attention is not split between a manual and the computer

Chapter 4: Focus Attention and Avoid Split Attention. John discusses the following issues related to attention: focusing attention, avoiding split attention, note-taking and attention, as well as split attention in computer training.

The asynchronous Load-Managed Excel Web-Based Lesson illustrates effective use of cues and signals to focus attention and to minimize divided attention. To view the text version, turn off the audio default option. Note the following:

Use of red circles to cue learners to relevant portion of the visual.

Use of underlining, bolding and italics in text.

Placement of text boxes and use of lines to link text to relevant portions of the spreadsheet.

The synchronous Virtual Classroom Example illustrates effective uses of cues and signals to focus attention and to minimize divided attention during the presentation. Note:

Instructor use of highlighter to draw attention to relevant portions of spreadsheet.

Instructor ground rules to minimize split attention during presentations.

Placement of exercise directions in text on the same screen as the exercise.

The asynchronous Overloaded Excel Web-Based Lesson fails to support attention effectively as a result of:

Lack of cues and signals in the graphics and text.

Placement of text at the bottom right-hand side of the screen with no lines or arrows to indicate links between text and visuals.

In this chapter we looked at ways to help learners attend to the most important information in the lesson. In the next chapter we will look at additional strategies for reducing the amount of content presented to working memory by weeding out related but unnecessary lesson content, by concise writing, and by avoiding redundant content displays.