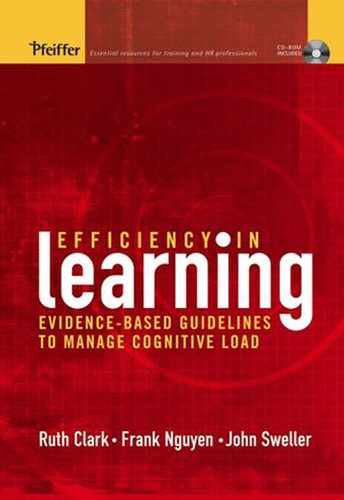

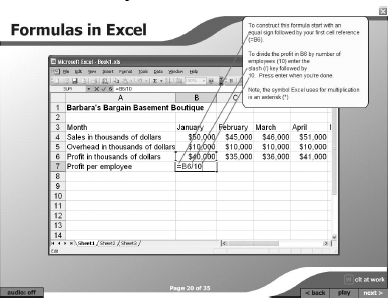

It's a common misconception that the more you give learners the better. Figure 5.1 shows a typical example. On this e-learning screen from our overloaded Excel lesson on the CD, we have explained the spreadsheet example with text on the screen and also with audio narration of that same text. The rationale for delivering content in dual modes is that they offer twice the learning opportunity. In addition, many believe that two modes accommodate learners who have visual learning styles as well as learners who have auditory learning styles. Another related misconception is that we can improve motivation and learning by adding interesting information to our basic instructional materials. Unrelated themes and games are commonly added to e-learning as a countermeasure for high dropout rates and to accommodate younger learners raised on computer games. An example of irrelevant information is found in Figure 5.1 in the "Did You Know" box in the lower left corner.

In this chapter we review evidence that recommends a lean approach to your training materials by eliminating extraneous content in the form of pictures, words, or audio that may be related to the main topic but is not relevant to the instructional goal. We also recommend eliminating multiple modes of expression that communicate the same information, such as the text and audio shown in Figure 5.1. Mayer and Moreno (2003) recommend weeding as a solution to over-inflated instruction. Alternatively, you can avoid weeding by simply avoiding extraneous content or modes of expression in the original course design.

By paring your content and delivery modes down to the essentials, you not only make learning more efficient, but you save development time as well. No need to spend extra resources on those entertaining but extraneous motivational stories or themes. No need to invest in redundant displays of content when one will do the job better. We know that working memory has a very limited capacity and we need to reserve those resources for learning. The most effective approach is to simply present the learner with the minimum required to achieve the instructional goals.

Guideline 8 recommends two ways to limit your words to the minimum needed to present the content related to the learning goal: (1) write concise instructional materials and (2) eliminate or resequence technical details.

Vigorous writing is concise (Strunk & White, 2000). Technical writers have long known that succinct rendering of content is more effective than verbose versions. In the 1980s, John Carroll (1992), as a result of many usability tests, designed and recommended computer manuals that he termed minimalist. In developing effective computer reference materials, he recommends that "One must deliberately not explain everything, only what must be explained. . . . Perhaps most important, when there is a problem one must not automatically add functions or build additional training modules; one must consider removing the function or documentation material associated with the problem" (p. 344).

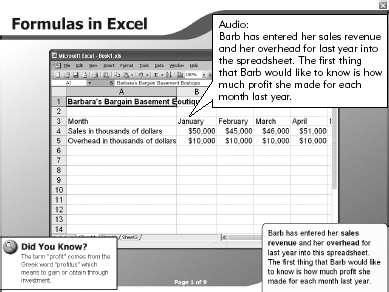

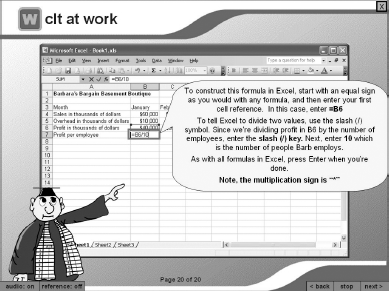

In concise writing every word contributes to the sentence and every sentence contributes to the learning goal. For example, Figures 5.2 and 5.3 show a flabby and a lean text version from our Excel load managed e-lesson on the CD. As you can see, our lean screen includes thirty fewer words than the inflated example. By ensuring that all your materials are as concise as possible, you can save instructional time and get better learning results!

Figure 5.3. A Concise Version of the Text in Figure 5.2 from Our Excel Load Managed Lesson on Our CD.

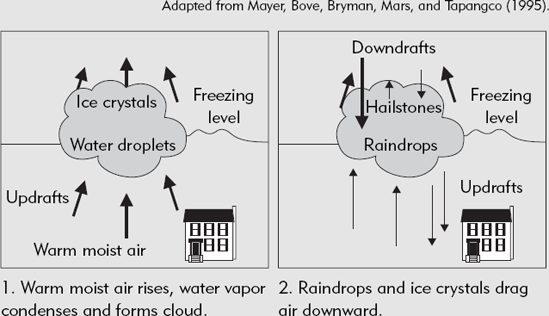

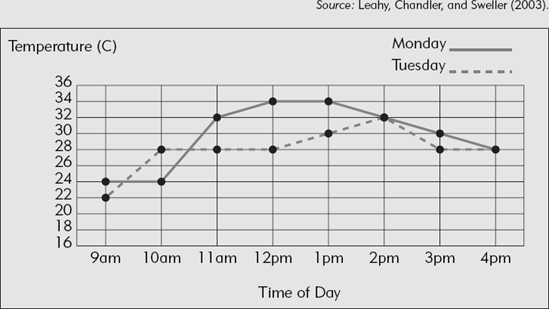

The best approach is to provide just enough content, that is, words and pictures, needed to help the learner build the desired schemas. While in the weather lesson, only a few pictures and words were sufficient, other instructional goals might require more.

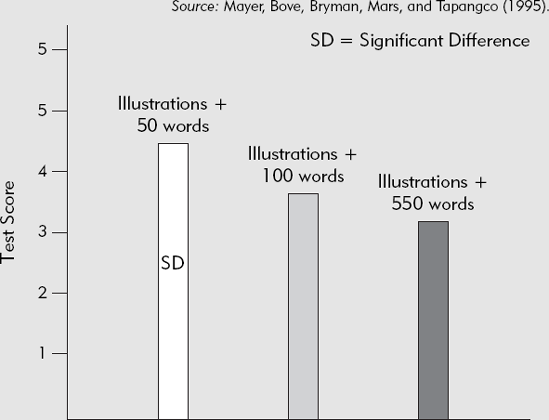

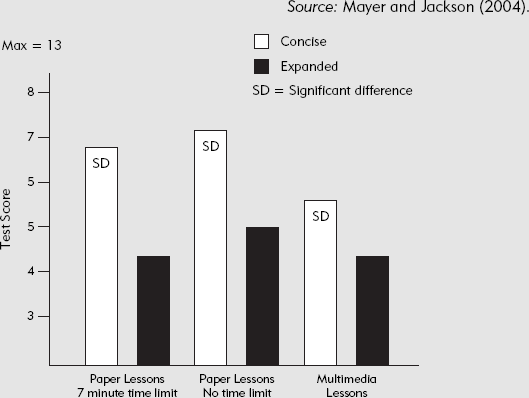

An effective summary is one which is concise, coherent, and coordinated (Mayer, Bove, Bryman, Mars, & Tapangco, 1995). That is, it uses fewer words to present the content, the words and pictures relate to each other, and, in combination, the words and pictures are directly relevant to the instructional goal. In the above research, all learners were given the same amount of study time. However, if learners had been allowed to study until they understood the material, it is highly likely that the concise versions would have required less study time than the more verbose. Therefore more concise text not only leads to better learning but would save instructional time as well. Since the most expensive element of any training program is the time learners spend away from the job, saving instructional time will directly contribute to cost benefit.

It's a common tendency of subject-matter experts to want to tell it all. As experts, they are not subject to the same cognitive load that novices will experience. Therefore, often they don't even realize they have overloaded their instruction with way too much content for the audience and for the instructional goal. Good instructional design sorts out the need-to-know from the nice-to-know and tosses out the nice-to-know. Here we look at research that shows that omitting technical content that is not required to understand the lesson improves learning.

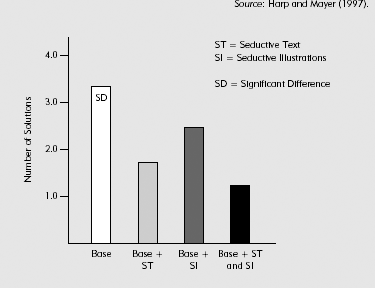

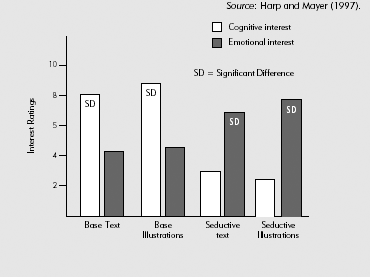

Under Guideline 8, we recommended writing concisely. We also recommended omitting technical content not needed to achieve the instructional objective. Now we turn to extraneous content that is used primarily to add interest to lessons. Under Guideline 9 we review evidence recommending omission of words, pictures, and audio added primarily for the purpose of interest or appeal. While well intended, such adjuncts run the risk of depressing learning.

e-Learning has been widely acknowledged for its high rate of dropout. Some suggest that younger learners weaned on computer games are especially prone to drop out from multimedia instruction that is devoid of the motivational elements contained in such games. As a countermeasure, some instructional programs have adopted an approach called edutainment. In edutainment adjunct graphics, music, themes, vignettes, and games designed to make the instruction more appealing are added to the basic instructional materials. Some adjuncts are completely unrelated to the content, such as embedding technical computer training in a "Tomb Raiders" game theme augmented with high end graphics and music. Other adjuncts are related to the content but unnecessary to the instructional goal. For example, the box in the lower left corner of the screen in Figure 5.1 is an adjunct that we created to add interest to our Excel lesson.

In keeping with our chapter theme of less is more, you won't be surprised that evidence shows that adding motivational content—even content topically related to the lesson—depresses learning. The good news is that you can save the resources required to create these additions and the learner's time invested in interacting with them. Instead of edutainment, you can invest your resources in promoting what instructional psychologists call cognitive motivation.

Related or unrelated themes, vignettes, or games added to technical materials in order to increase appeal are examples of emotional sources of motivation. These kinds of high-appeal additions are based on the theory that increasing the emotional impact of technical instruction by adding humor or interest leads to increased student engagement with the lesson and subsequently greater learning. In contrast, cognitive sources of motivation include instructional methods added to support the basic learning processes summarized in Chapter 2. Some examples include graphic organizers placed at the start of a lesson to preview the relationships among the content, an effective worked example to aid learners in building a mental model, as well as the many instructional methods we recommend throughout this book to manage cognitive load. Research we review next suggests that you omit additions designed to increase emotional motivation and invest your resources in cognitive motivational elements instead.

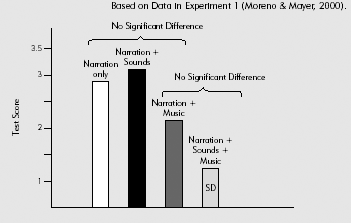

Many people prefer to study or work in the presence of background music. Likewise, music is often added to multimedia programs for the same reasons that seductive text and visuals are added—to increase lesson appeal. What is the effect of added audio either in the form of music or sounds related to the content? Here we review evidence regarding the effect of background music on learning, reading, and writing.

Taken together, the research supporting Guidelines 8 and 9 suggest that you:

Write concisely using only the number of words needed to convey the content.

Omit nice-to-know information in technical lessons.

Start technical lessons by building a qualitative mental model before adding quantitative details.

Eliminate visual or audio materials included to add interest.

Study, read, or write in quiet environments.

It is a common misconception that explaining content with multiple modes such as with text and audio narration of that text helps learning. One rationale for this misconception is that by using multiple modes of expression such as on-screen text and audio narration of that text you accommodate both visual and verbal learning styles. Counter to this folk wisdom, we have evidence that multiple content expressions actually overload working memory and depress learning!

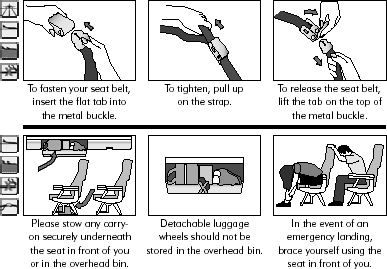

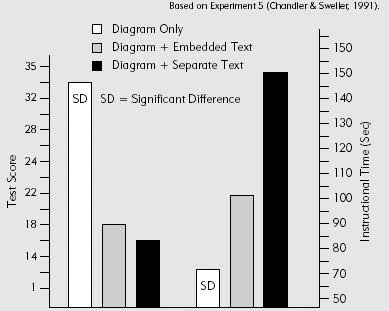

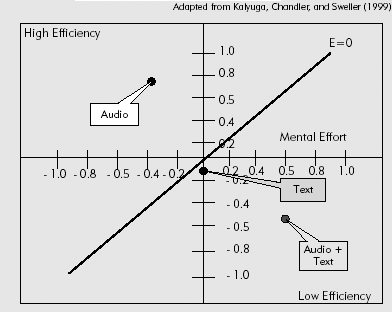

Redundancy in training refers to providing more expressions of content than needed for understanding. For example, in our airline safety card shown in Figure 5.10, the illustrations are clear and understandable in themselves. Adding explanatory text would be redundant. Or in a screen from our Excel overloaded example on the CD shown in Figure 5.1, the visual is explained by audio narration to leverage the modality effect. By adding on-screen text that replicates the audio narration, we have created a redundant expression of content. In Guideline 10 we review research related to redundancy as it applies to visuals alone, to narrated visuals and text, and to training of computer applications.

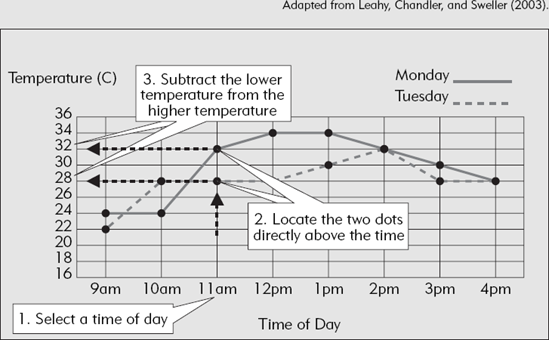

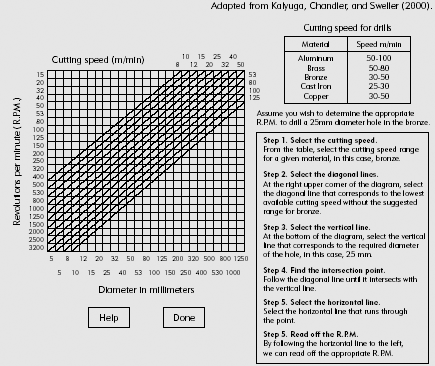

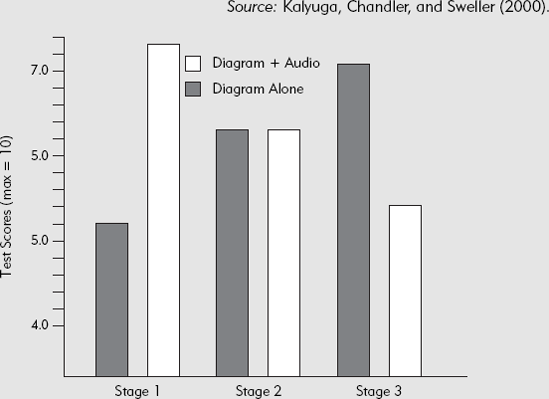

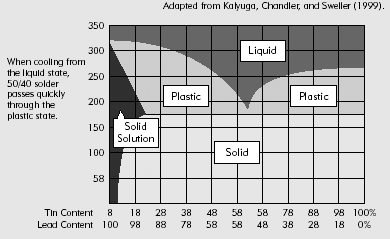

A visual may be self-explanatory for one of several reasons. In some cases, such as the airplane safety card, the drawing itself is inherently self-explanatory to anyone on the aircraft. In other cases a drawing may include some brief embedded text that makes the drawing understandable. Finally, a graphic that is not inherently self-explanatory may be familiar to a specific audience with previous experience using that graphic. In all of these situations, adding words in the form of either text or audio narration is redundant and will depress learning because working memory is better off with just the minimum amount of information needed for understanding. As with all cognitive load management guidelines, redundancy is most detrimental when high demands are made on working memory, such as when the content is complex and the learners are novices.

From this research, we see that audio explanations aided learning only when the tasks were more complex and only for visuals that were not self-explanatory. Therefore, you cannot universally apply a rule such as "Explain visuals with audio narration." Instead, you must consider the complexity of the task and the meaningfulness of the visual. Of course, the extent to which a visual is self-explanatory can depend on the experience of the learners. We discuss this issue next.

Taken together, the research supporting Guideline 10 suggests that:

Visuals may be self-explanatory because they visually incorporate all needed information; text is added to the visual; or the audience is familiar with the visual.

When visuals are self-explanatory, adding more explanations in the form of text or audio narration depresses learning.

When a visual does require an explanation, use audio (modality principle) or integrated text (to avoid split attention).

If you have to design training for a mixed audience that includes both experienced and novice learners, we recommend violating the split-attention guideline and placing explanatory text underneath the diagram. Although it adds a split-attention processing burden to novice learners, this format will allow more experienced learners to easily bypass the text and avoid a redundancy effect. Alternatively, if using audio narration to explain an on-screen visual, provide options for the audio to be suppressed by more experienced learners.

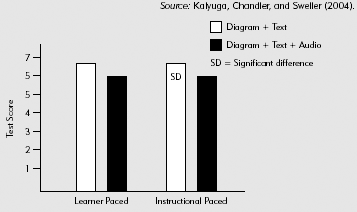

In e-learning, it's common practice to include a combination of on-screen text and audio narration of that text to describe an on-screen visual. For example, in Figure 5.1 from our overloaded Excel lesson demonstration on the CD, a visual of a spreadsheet is explained by on-screen text and audio narration of that same text. This presentation is redundant. A similar redundancy occurs in the classroom or synchronous e-learning when the instructor projects a slide containing a visual and text and reads the text to the class. Incorporating redundant words in visual and auditory form is based on misconceptions that receiving the same message twice will enhance learning and/or that some learners benefit more from visual representations and some from auditory representations so it's best to provide both. Both of these assumptions ignore working memory capacity limits.

Evidence we summarize below consistently suggests that, when describing a graphic, a single representation of words—either in text or in audio—leads to better learning than a dual representation. In our Excel Load Managed asynchronous e-lesson on the CD, on some screens we use just audio narration to explain the content and on other screens we use just text. In contrast, in our overloaded lesson, we violate the redundancy principle by using both text and audio.

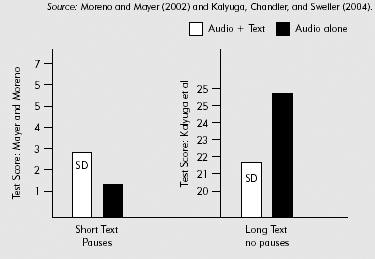

Some very recent experiments have evaluated the effects of first explaining a visual with audio narration followed by displaying the narrated words in text. By displaying the text after the narration, it is possible that a negative redundancy effect is reduced or even eliminated!

When explaining a complex visual in asynchronous e-learning, you may want to first present the audio followed by on-screen text. When using this technique, the textual presentation provides a review opportunity for those wanting more study time but can be quickly bypassed by those not needing the additional support.

In the research discussed under Guideline 10, words were used to describe a visual that was not self-explanatory. In other words, the visual required a verbal description. The findings recommend that, when describing such visuals, you should stick with audio alone rather than audio plus identical text presented simultaneously. What do we know about the effects of narration of on-screen text when there is no other visual? For example, in the classroom a PowerPoint® slide presents a sentence of text and the instructor reads that text to the class. Alternatively, an e-learning screen displays three sentences and audio narration reads the same words.

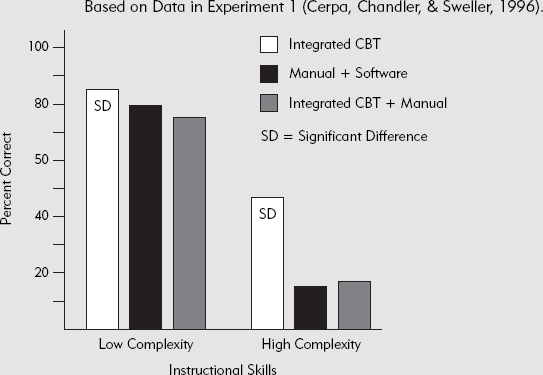

In Chapter 4, we recommended that you integrate step-by-step computer instructions onto screen simulations of the application and present the instruction wholly on the computer. Often new computer application training programs will present the steps and visuals on the computer and replicate them in a manual for reference. Having exactly the same content duplicated in two media, that is, on the computer and in a manual, is a redundant expression of content and will lead to less efficient learning!

An optimal format for learning computer applications is one that incorporates all instruction into the computer screens and omits either a redundant version that duplicates the screens in a manual or a split attention version that includes textual directions in the manual. In short, drop the manual.

There are solid research and psychological reasons for recommending that you offer less rather than more in your training by:

Writing concise text to present your content

Omitting words, visuals, or audio that do not contribute to understanding

Building a qualitative mental model first in technical lessons and adding quantitative details later

Avoiding redundant words, modalities, and delivery media

The benefits of a less-is-more approach can be realized in decreased time for development of instruction, reduced learning time, and better outcomes. In short, a lean approach is an efficient approach!

Chapter 5: Weed Your Training to Manage Limited Working Memory Capacity. John begins by defining the redundancy effect followed by a discussion of repetition versus redundancy, redundancy in computer training, and redundancy in instructor presentations.

Compare our Before: Overloaded Excel Web-Based Lesson to the After:

Load-Managed Excel Web-Based Lesson for the following elements:

The use of audio and text: Redundant in the Before version and not redundant in the After version.

Insertion of extraneous animation and content in the Before version removed from the After version.

All content is included in the computer lesson; no reference to an adjunct manual is made.

Notice that in the synchronous e-learning virtual classroom example:

Instructor does not read on-screen text to the class.

All content is included in the computer lesson.

The lesson content is succinct and relevant to the instructional goal.

In the past three chapters we have focused on ways to manage cognitive load by (1) making best use of the visual and phonological centers in working memory via the modality principle; (2) maximizing limited working memory capacity by focusing attention and avoiding split attention; and (3) streamlining lessons in ways that take a minimalist approach to instructional materials and interfaces.

In the next chapter we suggest that in some situations you can manage load by providing well-designed working aids to support learning and performance.