Throughout this book we have summarized instructional methods to avoid cognitive overload by accommodating working memory capacity limits. The methods include use of audio and visual modalities to maximize working memory resources, techniques to focus attention and to minimize split attention, and the elimination of redundant content and delivery modalities. Another strategy you can use to preserve limited mental resources is to reduce working memory load by providing external memory supports. Many job tasks do not require workers to perform or access knowledge from memory. Instead, they can use various reference resources to supplement their internally stored knowledge and skills.

External memory supports can be used during training and after training on the job. These memory supports are commonly known as performance aids. In some cases a performance aid may replace training altogether; in other cases performance aids are used during and after the learning event. In this chapter we summarize guidelines on the design of performance aids useful for the work environment as well as the instructional environment. Compared to instructional materials, there is a paucity of research on the efficiencies of performance aids. However, many of the guidelines summarized in previous chapters apply to performance aids. Therefore this chapter offers an opportunity to review what you have read to this point in the context of performance aids.

Under Guideline 11 we define performance aids and discuss situations that can benefit from performance support, either in the workplace or in an instructional setting.

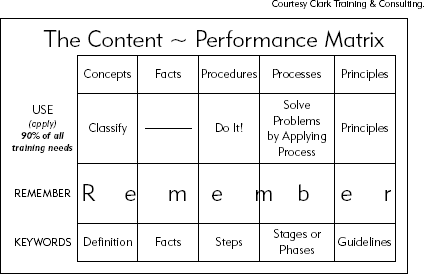

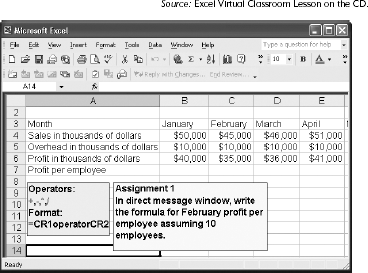

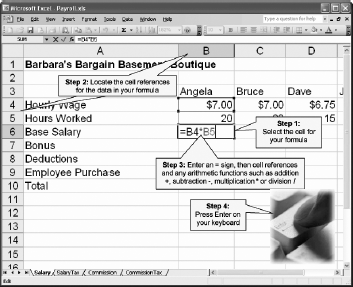

Performance aids package content required for task completion in a format that is readily accessible when needed in the work and learning environment. Factual information and procedure guides are the most common types of content included on performance aids. Some different types of performance aids include working aids, reference guides, wall charts, and "cheat sheets" in lesson materials. Figure 6.1 shows a working aid you have all most likely encountered—an airplane safety card. The goal of the aid is to illustrate critical procedures required of passengers. The wall chart shown in Figure 6.2 is a performance aid used in a seminar on instructional design. It summarizes five major types of content (concepts, facts, procedures, processes, and principles) and two levels of learning (remember and use) addressed in the seminar. During the class it serves as a presentation resource when the instructor explains the content and as memory support when learners are completing exercises and tests based on the content. Figure 6.3 illustrates a memory support placed on an exercise worksheet used in our synchronous virtual classroom Excel lesson on the CD. The operators and generalized format for Excel formulas are displayed in the left-hand box as a resource for learners during demonstrations and initial practice exercises. Performance aids delivered electronically are also called electronic performance support systems (EPSS). A familiar example is the step-by-step assistance offered by "Clippy" in Microsoft applications such as Word® and PowerPoint®. In all of these examples, information that is essential to achieve a work or learning task is displayed in a format that is readily accessible to the performer while working on the task.

There are a number of occasions that benefit from external memory support. In some situations it is neither necessary nor practical to train skills needed to perform a task. All airlines provide safety briefings during which the safety card is pointed out. However, training of passengers on emergency procedures is not practical. First, the need for safety procedures is rare and consequently, any skills learned would be soon forgotten. Second, it's not practical to give all passengers hands-on practice opening the emergency door. When training is neither needed nor practical and yet tasks must be performed, an effective working aid can offer a good solution. Even when training is provided, there are usually many tasks included in the training that are performed so rarely on the job that they will be forgotten. Working aids can offer a useful reminder for procedures once learned but rarely practiced after the class.

Performance aids are also useful as memory support during and after training. Most organizational training courses incorporate much more content than human working memory can process in the time allotted. Very little time is available for building strong schemas in long-term memory. Commonly, many training courses offer little or no practice opportunities. At best in most situations, learners may have an opportunity to practice new skills one time. To help workers access the large amount of knowledge and skills typically transmitted but not learned, we recommend that you use performance aids to provide essential performance-related content.

Facts and procedure steps are the most frequent content included on performance aids. For example, in new product training for sales staff, the product specifications can be summarized and packaged in easily accessible resources. Rather than devoting time to an extensive review of detailed product specifications, limited training time can be spent helping sales staff make use of the reference resource in the context of the sales process. In computer classes, learners should have access to a performance aid with the steps needed to complete all major procedures. Give learners an opportunity to try out the main procedures during training by following the directions on the performance aids. As a result of gaining familiarity with and confidence in the support resources during training, there is a higher probability they will use them on the job.

The use of memory support in classes can lead to a confluence of reference and training. Reference materials should be designed as effective memory aids organized around the context of work tasks—not product features. Training classes should integrate reference materials by requiring learners to use them as performance aids in order to complete class assignments such as case studies. Design reference and training to complement each other and to be used together. The integration of training and performance aids is called reference-based training. Reference-based training is especially useful in courses that incorporate a large number of facts or procedures to complete tasks. Software training is a common instance. In reference-based training, lesson materials include supporting information, worked examples, and case studies. When it's time to practice in-class exercises, learners use the reference as their guide. When reference-based training is successful, workers will rely on the reference guide in the workplace after training is completed.

When effective performance aids are readily available, workers do not usually commit the content to memory during training. In that sense they will not "learn" the facts or steps in the aid. A failure to learn should have no adverse consequences for infrequently used content for which workers can rely on performance aids as reminders. However, in some situations relying on a performance aid can be counterproductive. Some tasks need to be completed quickly and accurately for safety or effectiveness. Taking time to locate and study an aid could lead to serious adverse consequences. Landing an aircraft is one example. There is too much incoming data the pilot must attend in a short time frame during landing to also be referencing a working aid. The procedures required for landing must be stored in memory. Face-to-face sales situations may also suffer from too much reliance on performance aids. Better client response might result from an uninterrupted discussion of relevant product features. In work situations requiring immediate responses, the performance goal is better served by building knowledge and skill automaticity, as discussed in Chapter 9.

Keep in mind the "dumbing down" potential of working aids. When workers use performance aids, in most cases they are following step-by-step directions in a rote fashion and may not build any understanding. In many cases, that is fine. It does not matter to me how my cell phone works as long as I can set it up to perform the functions I need. On the other hand, it might matter to a cell phone technician doing diagnostic and repair tasks. When the instructional goal involves tasks that require judgment, you will need to build knowledge and skills in memory based on understanding. At best, a performance aid could serve as a reminder of skills practiced in training and committed to memory.

No matter when or where you plan to use external memory support resources, for best results you need to design them by applying the cognitive load management guidelines we have discussed in previous chapters. The majority of cognitive load research has been conducted in the context of learning—not performance support. In other words, in most experiments subjects are given time to study lesson materials and then are tested afterward without access to those materials. To measure performance, we need research that shows the influence of different types of performance aids on time and accuracy to complete a task while referencing the aid. Since there are few studies on performance aids, most of our guidelines related to design of performance aids will draw on research that measured learning. As more research on performance aids accumulates, we will adjust our guidelines accordingly. In the next section we offer design guidelines for creating effective working and training aids.

Under Guideline 12 we show how to apply evidence-based guidelines described in previous chapters specifically to design performance aids.

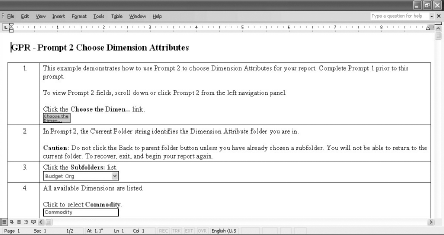

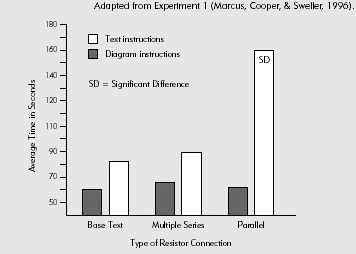

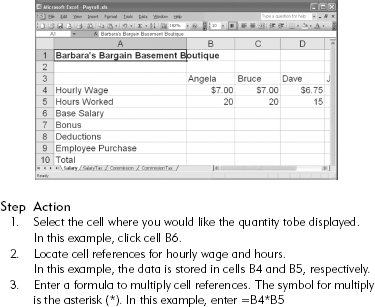

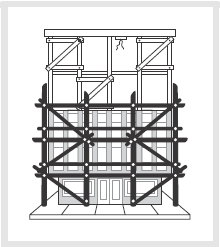

Since text is so easy to construct, a common error is to design text-dominant working aids with few or no visuals to represent tasks involving spatial work interfaces. For example, in Figure 6.4 we show part of a working aid developed to support a computer procedure. Note that the aid is mostly text. Instead, when the work task involves visual interfaces such as computer screens or equipment, use a graphic representation of that interface as the predominant, and if possible, only display.

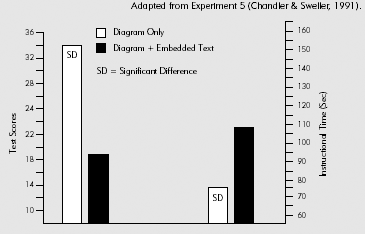

Visuals are more efficient psychologically because they can be processed holistically, whereas words require serial processing. In addition, for tasks involving two- and three-dimensional interfaces, a visual provides a more direct and psychologically efficient representation. Words describing physical interfaces will require a mental transformation from text into a spatial representation (Clark & Lyons, 2004).

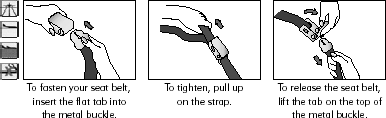

In the resistor performance aids, learners were able to connect the resistors by just using visuals alone. Adding explanatory text would be redundant. For example, the airline safety card shown in Figure 6.6 is not as effective as the version shown in Figure 6.1 because it adds words to diagrams that are self-explanatory. Adding more information than needed for understanding leads to redundancy and lower efficiency.

The research we have on use of visuals and text in performance aids recommends that you:

Use graphics alone when the task can be effectively communicated visually.

Use arrows or other motion cues rather than text to depict motion.

Design the graphic to reflect the visual perspective of the performer to minimize cognitive work needed to translate from one perspective to another.

Of course in many cases, a visual alone is not sufficient to adequately communicate task performance. For example, most performance aids designed to support computer tasks require screen shots with actions explained by text. In Chapter 4 we summarized research by Tindall-Ford, Chandler, and Sweller (1997) showing that apprentices learned electrical test procedures more effectively from instructional materials that integrated steps into the diagram than from materials that presented steps under the diagram. Similar results were reported by Moreno and Mayer (1999) when comparing e-learning versions in which explanatory text was integrated near the visuals or placed at the bottom of the screen.

In these research studies, learners did not have access to the instructional materials when they were tested. Therefore, the conclusions apply most directly to learning from instructional materials rather than performing tasks using work aids. Nevertheless, we recommend that split attention be minimized in performance aids as well as in instructional materials. We predict that performance aids with integrated text will lead to faster and more accurate task completion.

Figure 6.8 shows a poorly designed performance aid for a computer procedure in which the explanatory steps are located underneath the diagram at the bottom of the page. The performer will have to invest additional cognitive effort associating related text to the appropriate location in the screen. Figure 6.9 shows an improved version in which we integrated the text steps into the screen illustration.

Split attention is minimized when performance aids are co-located with the work interface. For example, some computer support aids are packaged in manuals or cards. Other computer support aids integrate help into the computer and/or into the application. Cognitive load theory recommends that you integrate procedural help as closely as you can into the application. First, design the performance aid to be delivered on the computer. Second, when possible, design the performance aid to be integrated into the application.

This experiment focused on learning. We need research to verify that performance support directions that are integrated with the interface would lead to faster and more accurate performance. However, until we have more research on best design of performance aids, based on current research, we recommend that you use an integrated approach.

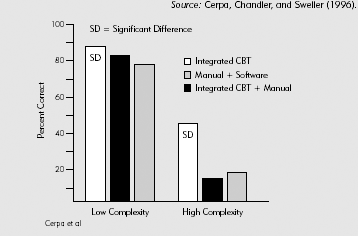

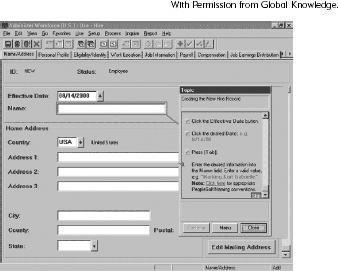

Global Knowledge designed the two online performance aids in Figures 6.11 and 6.12. Both aids are displayed in the computer application and thus avoid split attention between a manual and a computer screen. However, the aid shown in Figure 6.11 does a better job of integrating the steps presented in text to the relevant portion of the screen. The system tracks the user's progress through the procedure and automatically checks off steps in the instructional text. It also paints a red box that acts as a visual cue to focus the user's attention to the proper location on the screen. The version shown in Figure 6.12 does not integrate text with the software application. As a result, the users must manually advance the online performance aid as they complete the task, thereby splitting attention between the performance aid and software application. Unlike Figure 6.11, it does not provide an on-screen cue to indicate the location of the current task. Instead, it provides a small screen shot of the software application. This layout forces the user to manually match the content in the performance aid with the software application; it also offers a redundant visual display, thereby increasing cognitive load.

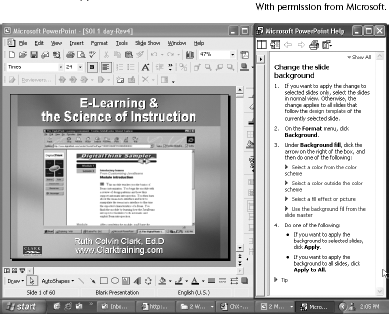

Of course it may not be practical to create customized performance support. For example, PowerPoint® is a highly flexible software tool that offers numerous features. Microsoft online support presents text instructions for various tasks co-located next to a reduced version of the running application. Figure 6.13 shows an example. In addition to cognitive load issues, designers have to factor in time, cost, and technical constraints when designing performance aids.

The research we have on display of steps to guide performance in computer applications recommends that you:

Place performance support on the computer rather than in a manual to avoid inefficiencies arising from split attention.

Integrate computer support into the application as much as possible given budget and technological constraints.

Your instructional environment—no matter what the topic or delivery media—can also benefit from memory support. By integrating memory support into your instructional materials, you can increase efficiency during learning. For example, if you are teaching how to use formulas in Excel, place a small reminder of the correct format on the page or screen where learners are required to apply that knowledge in a practice exercise, such as the example from our virtual classroom lesson on the CD shown in Figure 6.3. In this lesson, we created a small text box showing the formatting guidelines and positioned it close to the cell where the formula should be entered. When delivering training with a manual, consider placing performance aids on the same page or on a facing page as pages that display a related exercise. Alternatively, if the content will be used in many places throughout a course, display it on a wall chart or reference card allowing learners flexible access throughout the course. Although memory support on a card or wall chart will lead to divided attention between the manual and the aid, it is better than not providing any memory support or providing it on a page in the manual in a way that prevents the learner from easily viewing the aid and the exercise simultaneously.

If your final instructional goal requires learners to complete tasks from memory, you should fade the memory support as training progresses. For example, your first performance aid might show the entire format for an Excel formula. Later, you might reduce this to a reminder to start formulas with an equal sign. By the end of the training, you might remove all memory support. The decision regarding fading of support will depend on the extent to which effective job performance relies on learned skills and the extent to which those skills need to be built during training rather than later on the job. With the exception of safety-related training, most organizational training does not allow sufficient time for workers to practice enough to acquire new skills. Instead, they rely on work experience to complete the learning process. Of course, if memory supports are unavailable or unusable in the work environment, learning a task during training to the point where it can be performed without the memory support is essential.

Although there is a dearth of controlled research on performance aids, we apply cognitive load principles derived from research on instructional materials to recommend that you:

Provide workers and learners with external sources of content in the form of performance aids.

Avoid redundancy in performance aids by including the minimum needed to convey the content.

Integrate text into the visuals, if visuals require explanations.

Display performance aids for computer applications on the computer and into the application as much as is feasible.

As more research accumulates, we will modify our guidelines accordingly. At this point, we consider it highly likely that exactly the same cognitive load principles will apply to supporting performance as to learning.

Our sample synchronous Excel Virtual Classroom Lesson contains performance aids for use during instruction:

Onscreen reminders of formats for formulas placed close to formula location

Memory support faded as the lesson progresses

In Chapter 5 we recommended weeding out extraneous content not directly related to the instructional objective. Even so, you are likely to have a great deal of relevant content to convey to your learners. In the next chapter we look at design strategies you can use to spread that content out in a lesson or course to avoid imposing it on working memory all at once.

Training Design and Cognitive Load

Guideline 13: Teach System Components Before Teaching the Full Process

What Is Process Knowledge?

How to Segment and Sequence Process Content

How to Design Process Lessons

Guideline 14: Teach Supporting Knowledge Separate from Teaching Procedure Steps

What Are Procedures?

How to Segment and Sequence Procedure Content

Applying the Research

Design Alternatives at the Course Level

Guideline 15: Consider the Risks of Cognitive Overload Before Designing Whole Task Learning Environments

What Is Whole Task Learning?

Tradeoffs for Whole Task Instruction

Guideline 16: Give Learners Control Over Pacing and Manage Cognitive Load When Pacing Must Be Instructionally Controlled

Applying the Research

The Bottom Line

On the CD

John Sweller Video Interview

Sample Excel e-Lessons