SECTION 3.0

Study One: The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence Abilities, Project Management Competences, and Transformational Leadership Behaviors

3.1 Introduction

Given that the interest in the concept of emotional intelligence is rather a recent phenomenon, it is surprising that the importance of emotionally associated abilities or skills in project management was recognized over three decades ago. Hill (1977) identified how high-performing project managers were more likely to adopt greater listening and coaching behaviors, as well as facilitate openness and emotional expression. More recently, these skills or abilities have again been the focus of attention within project management, driven by the wider research in emotional intelligence and the increasing literature voicing concerns over the appropriate knowledge and skill base required for effective project management (Crawford, Morris, Thomas & Winter, 2006; El-Sabaa, 2001; Sizemore, 1988; Zimmerer & Yasin, 1998). Writers such as Winter et al. (2006), for example, have suggested that emotional competences are associated with the intuition and skills necessary for project managers to become reflective practitioners. As a result, project managers with high emotional intelligence should be better equipped to solve new challenges and problems that each new project brings. There have also been concerns that the training offered to project managers remains heavily weighted towards the hard, technical skills of the role, while the human skills have received far less attention (Pant & Baroudi, 2008). Although there is a growing body of research into the role that emotional intelligence plays in teams and in underpinning effective leadership, both of which are highly relevant for project working, the literature specifically examining emotional intelligence in projects is only just emerging.

In terms of empirical work investigating the role of emotional intelligence specifically in projects, our knowledge in this area remains fairly limited. Findings from recent studies examining emotional intelligence within a project management context would appear to confirm findings from studies more widely in the leadership literature that have found emotional intelligence to be a significant area of individual difference associated with effective leadership and, more specifically, transformational leadership (Butler & Chinowsky, 2006; Leban & Zulauf, 2004; Muller & Turner, 2007; Sunindijo, Hadikusumo, & Ogunlansa, 2007). However, a significant limitation of these studies is that, in either instance, there was no attempt to control for personality effects. Given that the measures of emotional intelligence used in almost every case (c.f. Leban & Zulauf, 2004) have received criticism for sharing some overlap with existing measures of personality, it becomes difficult to isolate the actual contribution that emotional intelligence may be making in relation to its underpinning particular behaviors or competences considered important for working in projects.

Given these limitations, this study aims to make a contribution to our understanding of the role emotional intelligence may play in projects by presenting findings from a pilot study that examined relationships between emotional intelligence, project management competences, and transformational leadership. Importantly, this study is an advance on previous research in this area by specifically controlling for both cognitive ability and personality. In so doing, the actual contribution of emotional intelligence in explaining variation in particular project management behaviors can be more clearly determined. The study is also the first to specifically identify which areas of project management practice, as outlined by current perspectives on project manager competences, are likely to be influenced by emotional intelligence using an ability measure of the construct. Given criticisms of other EI models that have been used in research to date within the project management field, this again offers a more targeted focus for identifying the specific contribution emotional intelligence may make within a project management context. Based on a sample of project managers in the UK, the findings suggest that emotional intelligence abilities and empathy may be a significant aspect of individual difference that contributes to behaviors associated with competences in the areas of teamwork, attentiveness, and managing conflict in projects.

3.2 Findings From Previous Studies Examining Emotional Intelligence in Projects

To date, only five studies have appeared in the literature specifically investigating emotional intelligence in project contexts, all of which have examined relationships between emotional intelligence and either leadership or project management competences Table 1). Four of these studies examined leadership in projects. Leban and Zulauf (2004) conducted a study of 24 project managers from six different organizations drawn from a wide range of industries. Data on the project manager's leadership style was obtained from team members and stakeholders, while the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso-Emotional Intelligence Ability Test (MSCEIT; Mayer & Salovey 1997) was used to assess the emotional intelligence of project managers. Overall emotional intelligence scores and the ability to understand emotions were found to be significantly related with the inspirational motivation dimension of transformational leadership.

Butler and Chinowsky (2006) investigated the relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership among senior level (vice-president or above) construction executives; however, this study used Bar-On's (1997) model of emotional intelligence, the EQ-i. This is a multifactorial model of emotional, personal, and social abilities that include the five EI domains of interpersonal skills, intrapersonal skills, adaptability, stress management, and general mood. Collecting data from 130 executives, they found a significant relationship between the total EQ-I score and transformational leadership. Of significance, this accounted for 34% of the variance of transformational leadership behavior. Of all the emotional intelligence dimensions they examined, interpersonal skills were found to be the most significant.

Muller & Turner (2007) sought to determine whether different types of leadership were more important depending upon the type of project. In a survey of 400 project management professionals, they identified which sorts of leadership competences were associated with success in different project types. Their overall results point to the variegated nature of leadership and how different sets of competences are appropriate for leadership in projects depending upon its degree of complexity (high, medium, or low), and the application area (e.g., engineering and construction, information systems, business). However, they used an additional model of emotional intelligence to underpin their study, drawing upon Dulewicz and Higgs’ (2003) 15 leadership competences. Within this EI model, 15 leadership competences are identified. Seven of these competences are categorized as emotional leadership competences which encompass (1) motivation, (2) conscientiousness, (3) sensitivity, (4) influence, (5) self-awareness, (6) emotional resilience, and (7) intuitiveness. Among their results, they found that the leadership competences of emotional resilience and communication accounted for most success in projects of medium complexity, while the emotional competency of sensitivity was found to be most important for high complexity projects. They also found that the emotional competency of conscientiousness was associated with success throughout all stages of the life cycle of projects. Different competences were also found to be associated with greater success, dependent upon the application area in which the project was based. For example, the emotional competences of conscientiousness and motivation were found to be most important for engineering projects, while self-awareness alongside communication was most important in information systems projects. Together the findings are significant in that they suggest differing leadership styles may be associated with varying project contexts. Further, also that differing emotional competences drawn from the EI model they used, are associated with each of the differing leadership styles. They concluded that project managers who possess a wider set of these emotional intelligence competences are more likely to be able to adopt their styles and behaviors to differing project conditions.

Finally, Sunindijo, Hadikusumo, and Ogunlansa (2007) investigated the relationship between emotional intelligence competences and leadership styles in 54 projects based in Bangkok. They identified 13 leadership behaviors from the literature and collected usable data on four dimensions of emotional intelligence from 30 project managers and engineers (PMEs). They also collected data on their leadership behaviors from their supervisors. This time, they used a fourth differing model of emotional intelligence to underpin their study, an instrument they obtained commercially which they suggest was based upon Goleman's (1995) EI competency model. Their results showed that those PMEs with higher EI mean scores demonstrated a greater frequency in the use of key leadership behaviors compared to PMEs with low EI scores. This included behaviors such as stimulating, rewarding, delegating, leading by example, open communication, listening, participating, and proactive behavior. However, it is important to note that statistically significant differences were only found for the leadership behavior of open communication and proactive behavior, and these were both at the 10% level of significance.

The final study, located in the literature in this area, focused instead on examining relationships between emotional intelligence and project management competences. Mount (2006) presented results from a study that was designed to identify the job competences that were associated with superior performance in a major international petroleum corporation. Using a range of data collection techniques including focus groups, interviews, surveys, as well as data from critical incidents, data were collected on job roles performed among other staff groups on74 asset construction project managers. The roles these project managers occupied was under transition, moving from a traditional engineering role to one that was more strategically aligned to individual business units. Using Goleman's (1995) set of emotional competences, they found that seven emotional competences (influence, self-confidence, teamwork, organizational awareness, adaptability, empathy, and achievement motivation), accounted for 69% of the skill set these project managers considered to be the most significant for their success on projects.

Together these studies suggest a significant role for emotional intelligence in terms of underpinning both leadership and important behaviors that have been suggested as associated with successful outcomes in projects. Supporting findings obtained from the wider literature, emotional intelligence in these studies was found to be significantly associated with dimensions of transformational leadership. Previously, transformational leadership had been found to be associated with significant performance in organizations (Lowe, Kroeck, & Sivasubramiam 1996; Yammarino, Spangler, & Bass 1993), and had also been suggested as the most appropriate leadership style for project management given its close association with leading successful change (Herold, Fedor, Caldwell, & Liu, 2008; Leban & Zulauf, 2004). However these EI and project studies do suffer a number of major limitations. The first of these relates to criticisms associated with the validity of the particular EI measures used. Both Goleman's and Bar-On's measures of emotional intelligence used in two of the EI project studies discussed earlier contain a number of dimensions (such as achievement, motivation, and organizational awareness in relation to the former; and assertiveness, stress management, and general mood in relation to the latter), which have been argued as technically not falling within the EI domain. The use of such measures to capture emotional intelligence have led a number of authors to raise serious doubts as to whether these conceptualizations and measures of EI are able to offer anything new over other existing measures already well known in the literature (Conte, 2005; Locke, 2005). Instead, the ability model of emotional intelligence and its associated measure have received far greater support as offering a more valid and conceptually distinct approach to considering the EI construct (Brackett & Mayer, 2003; O’Connor & Little, 2003). Studies using this measure of EI within the project management field may therefore be able to more clearly delineate the specific contribution of emotional intelligence.

A further significant limitation of these studies is that there was no attempt to control for either general ability or personality. In terms of individual differences, cognitive ability is widely recognized as perhaps the most important predictor of performance across a wide range of job contexts (Schmidt & Hunter 1998). In terms of leadership too, cognitive abilities have been found to be significant predictors of leadership performance (Antonakis, 2003; Judge, Bono, Ilies, & Gerhardt, 2002). Leadership, like project management, involves many behaviors that are likely associated with its effectiveness. However emotional intelligence is likely to be more relevant depending upon how far the particular behaviors associated with leadership and competences in project management involve getting things done through people relationships (Jordan & Troth, 2004; Offerman, Bailey, Vasilopoulos, Seal, & Sass, 2004). A number of writers have argued that the significance of emotional intelligence, particularly in leadership, is dependent upon leadership that is seen fundamentally as a relational activity (Prati, Douglas, Ferrus, Ammeter, & Buckley, 2003; Zhou & George, 2003). It is therefore important that studies control for both cognitive ability and personality, if the additional contribution EI makes is to be determined. For example, the emotional competence of conscientiousness found to be significant for leadership in differing project types and complexity by Muller and Turner (2007) may well be tapping into the similarly named personality factor found in the Big 5 (McCrae & Costa, 1987).

We are also still some way from gathering findings from research specifically within the project management field, that may lend support for key arguments outlined earlier by Druskat and Druskat (2006) suggesting why EI may be particularly important within project contexts. Despite the limitations from the use of the particular EI measure used, Mount's (2006) study, which examines the relationship between emotional intelligence and the skills for successful project management, does offer some preliminary signs that emotional intelligence may be important for a wide range of behaviors considered necessary for working in project management contexts. However, to date, no studies have yet to appear in the literature that have examined relationships between emotional intelligence and those specific behaviors suggested as significant by Druskat and Druskat (2006) as key to working in projects.

3.3 Focus of the Current Study

Given the limitations with some of the previous studies examining emotional intelligence in projects, this study seeks to build on the current literature in two major ways: (a) through investigating whether emotional intelligence is associated with a number of behaviors posited as key for successfully working in project contexts; and (b) by using an ability-based model of emotional intelligence and controlling for both cognitive ability and personality.

Regarding the investigation of whether emotional intelligence is associated with a number of behaviors as key for successfully working in project contexts, Druskat and Druskat (2006) suggested that the specific characteristics of projects are unique from other forms of work organization that place an additional premium on the importance of emotional intelligence. They identified four specific characteristics alongside specific project manager behaviors that are necessary for successful project management. Firstly, the temporary nature of projects places considerable emphasis on communication skills. Secondly, the uniqueness of every project requires well-developed teamwork skills. Thirdly, the complexity of projects requires highly developed skills to involve other project members and respond to their concerns. Finally, the requirements for inter-organizational and international collaboration associated with many projects requires skills in cross-cultural management, particularly those relating to conflict management. However much of this has yet to receive any empirical support based upon research in projects.

This first component of the pilot study therefore sought to address the following two objectives:

(1)To identify the relationships between emotional intelligence abilities and specific project manager competences identified as critical within project contexts.

(2)To identify relationships between emotional intelligence and transformational leadership behaviors.

Five specific hypotheses were tested in the study to address these two objectives. Each of these and their rationales are included herein. Teamwork skills have been identified in a number of studies as among the “critical success factors” of projects (Rudolph, Wagner, & Fawcett, 2008; Tisher, Dvir, Shenhar, & Lipovetsky, 1996). Many authors have suggested that emotional intelligence is either responsible for, or underpins an individual's ability to engage in social interactions (Caruso & Wolfe, 2001; Lopes, Salovey, & Strauss, 2003) such that it may well be an underlying construct of social skills (Fox & Spector, 2000). This is based on the premise that emotions are key components of both how we communicate and can facilitate socialization within groups (Keltner & Haidt, 2001; Lopes et al., 2004). Supporting this proposition have been a number of studies which have demonstrated significant relationships between EI measures and a range of social interaction indices, including more positive social interactions with peers and friends (Brackett, Mayer & Warner, 2004). Individuals scoring higher on the emotional ability to manage emotions, for example, have reported more satisfying interpersonal relationships (Lopes et al., 2003). Elsewhere, research examining emotional intelligence within a team context has found positive relationships between EI and propensity for teamwork (Ilarda & Findlay, 2006) and EI and interpersonal team processes (Clarke, in press). This, therefore, leads to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Emotional intelligence abilities and empathy will be positively associated with the project management competence of teamwork.

Differences in individuals’ emotional skills have long been suggested as accounting for variations in the extent to which they are able to decode nonverbal and emotional communication (Friedman & Riggio, 1981; Hall & Bernieri, 2001; Riggio, 1986; Rosenthal, 1979). Both emotional intelligence abilities and empathy have been identified as underpinning more effective communication (Ickes, 1997; Riggio, Riggio, Salinas, & Cole, 2003). Project manager communication skills and the quality of communication in projects have been found to contribute to project outcomes (Drouin, Bourgault, & Bartholomew-Saunders, 2008) Previously, Sunindijo, Hadikusumo, and Ogunlana (2007) found a positive relationship between emotional intelligence competences and project manager competences that included communication. This gives rise to the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Emotional intelligence abilities and empathy will be positively associated with the project management competence of communication.

Addressing the individual needs and concerns of team members and involving them in decisions have long been recognized as key aspects associated with team effectiveness (Dyer, 1995) and important behaviors associated with effective leadership of teams (Adair, 1979; Fleishman, 1974). These attentiveness behaviors have been identified as important for relationship building, social integration, enhancing group identification, and developing commitment and trust, all seen as key elements associated with the effectiveness of teams (Bishop & Scott, 2000; Cohen & Bailey, 1997). More recently these behavioral dimensions of project managers have also been suggested as important to success in projects (Drouin et al., 2008; Dvir, Ben-David, Sadeh, & Shenhar, 2006; Lester, 1998; Randolph & Posner, 1988; Strohmeier, 1992; Taborda, 2000). These attentiveness behaviors are likely to assist project managers to build high-quality inter-personal relationships within short periods of time, which is important given the unique and temporary nature of projects (Druskat & Druskat, 2006). Emotional sensitivity and emotional expression are key aspects associated with emotional intelligence and empathy that have been suggested as associated with performing attentiveness behaviors (Feyerherm & Rice, 2002; Rapisarda, 2002; Riggio & Reichard, 2008). Previous research has also found a positive relationship between the two emotional abilities, using emotions to facilitate thinking and managing emotions and attentiveness behaviors associated with interpersonal team processes (Clarke, forthcoming). This give rise to the third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Emotional intelligence abilities and empathy will be positively associated with the project management competence of attentiveness.

Conflict between partners and members has often been cited as a major factor undermining effectiveness or contributing to failure in projects (Nordin, 2006; Sommerville & Langford, 1994; Terje & Hakansson, 2003) and is widely recognized as a consistent feature associated with working in projects (Lazlo & Goldberg, 2008; Terje, 2004). Previous research has found relationships between emotional intelligence and better conflict management strategies in team settings (Ayoko, Callan & Hartel, 2008; Jordan & Troth, 2004); however, these studies used team level measures. Rahim and Psenicka (2002) reported findings which examine emotional intelligence and conflict management strategies at the individual level using Goleman's model (1998) of EI. They found that self-awareness was associated with self-regulation and empathy. Empathy was associated with Goleman's motivation measure, which in turn was positively associated with more effective approaches to conflict management. A positive relationship between self-regulation and the use of positive approaches to managing conflict have also been found using a trait measure of EI (Kausahal & Kwanters, 2006). Although no studies to date have investigated relationships between emotional intelligence and conflict management using the ability model of emotional intelligence at the individual level, a number of authors have suggested that emotional abilities should assist individuals to better regulate their emotional responses in conflict situations, which would prevent them from spiraling out of control. Similarly, individuals with a better understanding of how circumstances and situations cause both positive and negative emotional responses should be better at recognizing potential conflict flashpoints and successfully dealing with conflict at earlier stages so it might be used more creatively rather than become destructive (Zhou & George 2004). This gives rise to the fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Emotional intelligence abilities and empathy will be positively associated with the project management competence of conflict management.

Transformational leadership (Bass & Alvolio, 1994) comprises the four key dimensions of (1) idealized influence, (2) inspirational motivation, (3) intellectual stimulation, and (4) individualized consideration. This type of leadership is associated with higher levels of motivation in the followers through activating their higher-level needs and generating a closer identification between leaders and followers. A number of authors have suggested that underpinning transformational leadership is the enhanced emotional attachment to the leader (Ashkanasy & Tse, 2000; Dulewicz & Higgs, 2003) that arises as a result of leaders using emotional intelligence. By accurately identifying emotions in followers, leaders are able to respond more effectively to their needs. Through expressing emotions effectively, leaders can generate compelling visions for followers and gain greater goal acceptance (George, 2000; Sosik & Megerian, 1999). The use of positive affect can also influence followers’ mood states which then impact on different outcomes (Sy, Cote, & Saavedra, 2005). A number of studies previously have found significant relationships between emotional intelligence and transformational leadership (Barling, Slater, & Kelloway, 2000; Downey, Papageorgiou, & Stough, 2005; Mandell and Pherwani, 2003) as well as a number of studies specifically within project contexts (Butler & Chinowsky, 2006; Leban & Zulauf, 2004). This gives rise to the fifth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: Emotional intelligence abilities will be positively associated with project management transformational leadership.

3.4 The Study and Methods

Sixty-seven project managers were recruited from two organizations based in the UK and from the UK chapter of the Project Management Institute to take part in the study. Both organizations were actively engaged in projects as their major form of work process. The first was a national arts organization involved in commissioning and developing projects within the cultural sector. The second was a national organization comprising a number of divisions ranging from construction, research and development, and professional services, working across a range of differing business sectors. The average age of participants was 39.6 years (SD 7.9), and ages ranged from 23 to 58 years old. Eighteen of these participants (27%) were qualified in project management. Participants identified their core job function as follows: general management 20 (30%), marketing/sales 2 (3%), HRM/training 3 (4.5%), finance 2 (3%), R&D 2 (3%), technical 6 (9%) and other 32 (47.5%). The relatively large number of participants identified in the other category can be explained by the significant number of participants working in specialist fields in either education or the arts. Table 2 illustrates the nature of project management experience possessed by those taking part in the study. Here we can see that more than half of the participants taking part in the study had experience working in projects associated with organizational change followed by information technology. When asked to describe the degree of complexity associated with these projects, they were usually involved; just over 75% rated these as either medium or high complexity.

3.4.1 Procedure

All participants were asked to complete on-line instruments to assess emotional intelligence, empathy, cognitive ability, personality, transformational leadership, and project management competences within a 2-week period in 2008.

3.4.2 Measures

3.4.2.1 Independent Measures:

(1) Emotional Intelligence. Emotional intelligence was measured using the MSCEIT V2.0 available from MHS Assessments. The MSCEIT V2.0 consists of 141 items divided into eight sections or tasks that correspond with the four branches or abilities of Mayer and Salovey's (1997) ability model of emotional intelligence: (a) perceiving emotions (B1), (b) using emotions to facilitate thinking (B2), (c) understanding Emotions (B3), and (d) managing emotions in oneself and others (B4).

Participants completed the assessment online, and scores for each of the branches were computed by the test administrators (MHS Assessments). Scores were standardized in relation to a normative sample of over 5,000 individuals with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15. Reliabilities for the scales were previously reported as 0.90, 0.76, 0.77, 0.81, and 0.91 for each of the four branch scales and the full scale, respectively (Mayer et al., 2002). Reliabilities obtained here for each of the four branches were 0.88, 0.69, 0.90, and 0.55 respectively, and 0.92 for the full scale (total EI).

(2) Empathy. Mehrabian and Epstein's (1972) 33 items of emotional empathy were used to assess empathetic tendency. Responses to each item were scored on a scale ranging from +4 (very strong agreement) to –4 (very strong disagreement). Scores on 17 items were negatively scored in that the signs of a participant's response on negative items were changed. A total empathy score was then obtained by adding all 33 items. Sample items include (1) (+) “It makes me sad to see a lonely stranger in a group,” and (24) (–) “I am able to make decisions without being influenced by people's feelings.” The scale authors previously reported on the split-half reliability for the measure was 0.84. Here the Spearman-Brown split-half coefficient was found to be 0.82, suggesting good reliability.

3.4.2.2 Dependent Measures

(1) Project Manager Competences. An instrument for measuring four project management competences posited to be associated with emotional intelligence was constructed. Each project management competence contained three or more behaviors within an overall scale. Participants were asked to rate how well they performed each behavior in the last project they were involved in. Each item was assessed using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “1= not at all well” to “7= very well.” Scores for each competence were then obtained by adding all relevant behavioral items and then obtaining the mean score for each scale. Details of scale validation are provided below. Sample items for each of the four scales and reliability coefficients obtained are as follows:

A. Communication (alpha 0.70). Sample items included (1) understood the communication from others involved in the project; and (2) maintained informal communication channels.

B. Teamwork (alpha 0.78). Sample items included (1) helped to build a positive attitude and optimism for success on the project; and (2) helped others to see different points of view or perspectives.

C. Attentiveness (alpha 0.68). Sample items included (1) responded to and acted upon expectations, concerns, and issues raised by others in the project; and (2) actively listened to other project team members or stakeholders involved in the project.

D. Managing Conflict (alpha 0.86). Sample items included (1) helped to solve relationship issues and problems that emerged on the project; and (2) managed ambiguous situations satisfactorily while supporting the project's goals. All scales were found to have good reliabilities (Nunally & Bernstein, 1993).

(2) Project Managers’ Transformational Leadership. The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Form 5X (Bass & Avolio, 1997) was used to measure transformational leadership behaviors. All of the MLQ-5X responses are made on a five-point scale ranging from “0 = Not at all” to “4 = Frequently, if not always.” Transformational leadership is measured by four subscales: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Items from these subscales were added and then the mean was used to provide a total score for each scale. Previous research has shown good reliability and validity for the total scales and subscales ranging from 0.74 to 0.94 (Bass & Avolio, 2000). Reliabilities for each of the subscales obtained here were 0.68, 0.52, 0.85, and 0.55 for idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration, respectively. Reliability for the overall scale was 0.84.

(3) Control Variables. Control variables were as follows:

A. Personality. Personality was assessed using the Individual Perceptions Inventory (IPI; Goldberg, et al., 2006). This is based upon McCrae and Costa's Big 5 personality characteristics and consists of a 50-item questionnaire designed to capture the personality dimensions of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness. Previous studies have shown the IPI to have strong convergent validity with other personality measures such as the 16PF and the NEO-PI (Goldberg, 1999). Scale reliabilities were found here to be extraversion (0.89), agreeableness (0.83), conscientiousness (0.78), emotional stability (0.84), and openness (0.81).

B. General Mental Ability. General Mental Ability (GMA) was measured using the 50-item Wonderlic Personnel Test (WPT; Wonderlic & Associates, 1983). Participants completed the timed test online and a single score was provided, indicative of an individual's overall level of GMA. Reported reliabilities for the Wonderlic test ranged from 0.78 to 0.95 and have been shown to have good convergent validity with other measures of intelligence such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS, Wonderlic & Associates, 1983).

C. Project Management Qualification. Previous certification in project management is likely to have familiarized participants with those competences that were being self-assessed in the study and might therefore influence more positive responses. In order to control for the effects of familiarity with project management competences, certification in project management was entered as a further control variable. This was similarly entered as a simple dichotomous coding with “1 = certified in project management” and “0 = not certified.”

3.4.3 Procedure for Validation of Project Manager Competence Scales

Clarke (in press) previously suggested that studies should theoretically justify which aspects of behaviors, associated with working in projects or teams, one would expect emotional intelligence to be associated with prior to examining relationships. Druskat and Druskat (2006) put forward arguments suggesting that the characteristics of projects placed particular emphasis on project manager behaviors associated with communication, teamwork, building interpersonal relationships (attentiveness), and managing conflict. Based on the rationales outlined above, significant relationships should be expected between emotional intelligence and these project manager competences. In order to ground behavioral items associated with these competences within project management, items were initially selected from the Project Manager Competency Development Framework (PMI, 2007), which appeared to correspond with these four competences. Although project type and characteristics are acknowledged as perhaps placing more emphasis on some competences over others, the competences identified within the framework are suggested as having a broad application. The competency framework categorizes two groups of competences as those pertaining to performance and personal dimensions. Personal competences are those identified as capturing the specific sets of skills to “enable effective interaction with others” (PMI, 2008, p. 23). These are further arranged into six unit areas (communicating, leading, managing, cognitive ability, effectiveness, and professionalism), containing 25 elements overall.

The first stage involved selecting items for inclusion in each of the four competence areas from the complete range of behaviors identified in the framework, which on face content appeared to be associated with the four project manager competences that are the focus of the study. This resulted in 24 project management behaviors that were grouped into the four project manager competence domains. These are shown in Table 3 mapped against the specific PMI competence elements listed in the PMI framework. Face validity of these items was then further investigated with a small group of six project managers not participating in the research. This resulted in all 24 items being retained for each of the competences as follows: communication (4 items), teamwork (7 items), attentiveness (5 items) and managing conflict (8 items).

All 24 items were then organized into an instrument that formed a part of a larger questionnaire which participants completed online. Participants responses were then subject to an exploratory factor analysis using principal components with a varimax rotation. The rotation converged in 15 iterations resulting in a six-factor solution, accounting for 36.4%, 9.6%, 7.5%, 5.6%, 4.6%, and 4.5% of the variance, all with Eigen values greater than 1. The factor loadings are presented in Table 4. Items were retained for factors where weights were greater than 0.40, where there was no cross loading, and where items appeared to be theoretically consistent. Nearly all items retained on scales were consistent with those initially identified through face validity. The major exceptions were from the teamwork scale, where only one item was retained from those initially posited and two further items were drawn from the attentiveness and managing conflict behavioral domains. These three items were determined to have theoretical integrity when compared to the literature relating to effective teamwork behaviors, and so they were retained (Cohen & Bailey, 1997; Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001; Rickards, Chen, & Moger, 2001; Salas, Sims, & Burke, 2005).

Table 3. Grouping PMI project Management Competence Elements into Key project Management Competence Measures

| Project Manager Competences | PMCD Framework element |

| Communication | |

1. Understood the communication from others involved in the project? |

6.1 |

2. Maintained formal communication channels? |

6.2 |

3. Maintained informal communication channels? |

6.2 |

4. Communicated appropriately with different audiences? |

6.4 |

| Teamwork | |

5. Encouraged teamwork consistently? |

8.1 |

6. Shared your knowledge and expertise with others involved in on the project? |

8.1 |

7. Maintained good working relationships with others involved on the project? |

8.1 |

8. Worked with others to clearly identify project scope, roles, expectations, and tasks specifications? |

8.2 |

9. Built trust an,d confidence with both stakeholders and others involved on the project? |

11.4 |

10. Helped to create an environment of openness and consideration on the project? |

11.4 |

11. Helped to create an environment of confidence and respect for individual differences? |

11.4 |

| Attentiveness | |

12. Responded to and acted upon expectations, concerns and issues raised by others in the project? |

6.1 |

13. Actively listened to other project team members or stakeholders involved in the project? |

6.1 |

14. Expressed positive expectations of others involved on the project? |

7.3 |

15. Helped to build a positive attitude and optimism for success on the project? |

7.3 |

16. Engaged stakeholders involved in the project? |

10.2 |

| Managing Conflict | |

17. Helped others to see different points of view or perspectives? |

8.3 |

18. Recognized conflict? |

8.3 |

19. Resolved conflict? |

8.3 |

20. Worked effectively with the organizational politics associated with the project? |

9.1 |

21. Helped to solve relationship issues and problems that emerged on the project? |

10.1 |

22. Attempted to build consensus in the best interests of the project? |

10.2 |

23. Managed ambiguous situations satisfactorily while supporting the project's goals? |

10.3 |

24. Maintained self-control and responded calmly and appropriately in all situations? |

11.3 |

3.4.3.1 Data Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 15. Initial tests began by performing bivariate correlations in order to explore initial relationships between variables measured in the study. This was then followed by conducting a series of regression analyses where each of the four project manager competences was regressed in turn against emotional intelligence measures and empathy. The next set of analyses followed the same procedure, but instead regressed each of the four dimensions of transformational leadership. Both investigations were undertaken by entering IQ, personality measures, and certification as control variables in the first step, followed by the four EI branch scores, total EI score, and empathy in the second step.

3.5 Results

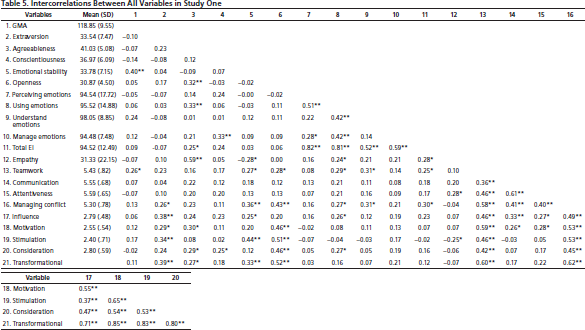

Correlational analyses were used as an initial examination of relationships between the variables studied. Table 5 summarizes the means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among all the variables used in the study. Total EI was significantly correlated with all four of its constituent branches: perceiving emotions (r = 0.82, p < 0.01), using emotions to facilitate thinking (r = 0.81, p < 0.01), understanding emotions (r = 0.52, p < 0.01), and managing emotions (r = 0.59, p < 0.01). The significant correlations found were as expected, if these individual branches are part of a much wider overall construct of emotional intelligence. A number of significant correlations were found between EI measures and the dependent measures examined in the study. Branch 2, using emotions to facilitate thinking, Branch 3, understanding emotions, and the overall EI score were all found to positively correlate with the project manager competence of managing conflict (r = 0.27, p < 0.05), (r = 0.31, p < 0.05), and (r = 0.30, p < 0.05), respectively. Both of the abilities, using emotions and understanding emotions, also positively correlated with the project manager competence of teamwork (r = 0.29, p < 0.05) and (r = 0.31, p < 0.05). Using emotions to facilitate thinking was the only EI ability found to have any significant correlation with transformational leadership and this was in relation to the two dimensions of idealized influence (r = 0.26, p < 0.05) and individualized consideration (r = 0.27, p < 0.05). Both total EI and branch scores showed minor correlations with personality, offering further support for the predominantly independent nature of these two aspects of individual difference. Only three positive correlations were found and these were between conscientiousness and managing emotions (r = 0.33, p < 0.05), and agreeableness with using emotions to facilitate thinking (r = 0.33, p < 0.01) and the overall EI score (r = 0.25, p < 0.05). Previously, agreeableness, emotional stability, and extraversion were found to be related to dimensions of EI (Day & Carroll, 2004; Lopes, Salovey, & Strauss, 2003). A positive relationship to agreeableness is often found given that this scale is often seen as reflecting compassion and cooperation. The positive relationship with conscientiousness is possibly explained given that conscientiousness is often thought to capture aspects of personality associated with self-discipline rather than acting spontaneously (Hogan & Ones, 1997). These are behaviors closely associated with impulse control, and this forms a key part of managing one's own emotions.

Both using emotions to facilitate thinking (r = 0.24, p < 0.05), and total EI (r = 0.28, p < 0.05), were found to be positively correlated with empathy. Given that empathy involves having to think about emotions in order to respond empathically, these results are consistent with a number of other previous studies showing that ability EI measures can correlate with self-judgments of empathetic feeling (Brackett, Rivers, Shiffman, Lerner, & Salovey, 2006; Caruso, Mayer, & Salovey, 2002; Ciarrochi, Chan, & Caputi, 2000). Significant positive correlations were also found between empathy and the personality dimension of agreeableness (r = 0.59, p < 0.01) and between empathy and the project manager competence of attentiveness (r = 0.28, p < 0.05). This again appears to support previous findings in the literature that show a significant relationship between empathy and displaying considerate or prosocial behaviors (Eisenberg & Miller, 1987). The significant negative correlation between empathy and the transformational leadership dimension of intellectual stimulation (r = –0.25, p < 0.05) was unexpected and seemed counter-intuitive to the prevailing view that transformational leadership is based upon a strong emotional relationship between leaders and followers. There was also a negative correlation obtained between empathy and emotional stability (r = 0.28, p < 0.05). Both of these findings may be due to the empathy measure used here, capturing emotional rather than cognitive dimensions of empathy with a particular emphasis on elements relating to individual's emotional responses to others in distress. Previously, this aspect of empathy was found to be negatively associated with transformational leadership (Skinner & Spurgeon, 2005).

It should also be noted that that there were a number of positive correlations found between personality measures and the project manager competence of managing conflict: extraversion (r = 0.26, p < 0.05), emotional stability (r = 0.36, p < 0.01), and openness (r = 0.43, p < 0.01). Openness was also found to positively correlate with the project manager competence of teamwork (r = 0.28, p < 0.05). In addition, personality measures accounted for the largest number of both high and significant correlations with transformational leadership dimensions here. Extraversion correlated with influence (r = 0.385, p < 0.01), motivation (r = 0.29, p < 0.05) and stimulation (r = 0.34, p < 0.01). Emotional stability correlated with influence (r = 0.25, p < 0.05) and stimulation (r = 0.44, p < 0.01). Openness correlated with motivation (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), stimulation (r = 0.51, p < 0.01), and consideration (r = 0.46, p < 0.01). Four of the five personality dimensions were found to have positive and significant correlations with the overall transformational leadership scale: extraversion (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), agreeableness (r = 0.27, p < 0.05), emotional stability (r = 0.33, p < 0.01), and openness (r = 0.52, p < 0.01). Finally, it is worth commenting that cognitive ability was found to correlate positively with the project manager competence of teamwork (r = 0.26, p < 0.05) but not with any of the remaining competences, nor with any transformational leadership measures. This may suggest that both personality and aspects of EI have far more salience in underpinning these particular competences and leadership behaviors than cognitive ability.

Results of the first set of hierarchical regressions are shown in Table 6. The emotional intelligence ability, understanding emotions, was found to be significantly associated with the project manager competence of teamwork (β = 0.28, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.07). The two personality dimensions of openness and emotional stability together accounted for 13% of the variation for this competence, with this EI ability explaining a further 7%. Partial support was therefore found for hypothesis 1. None of the relationships with EI measures or empathy with the project manager competence of communication were found to be significant (F [6,61] = 0.85, p > n.s.), providing no support for hypothesis 2. Empathy was found to be significantly associated with the project manager competence of attentiveness (β = 0.28, p < 0.05). However, no significant relationships were found between this project manager competence and any of the EI measures. Partial support was therefore found for hypothesis 3. Of note, neither cognitive ability nor personality was found to be associated with this competence, with empathy solely accounting for a 7% variation in this competence.

The overall EI score was also found to be significantly associated with the project manager competence, managing conflict (β = 0.26, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.06). Again both the personality dimensions of emotional stability and openness were found to account for most variation in the project manager competence, jointly accounting for a significant 30% with the overall EI score explaining the additional 6%. Partial support was therefore found for hypothesis 4. Finally, the emotional ability, using emotions to facilitate thinking was found to be significantly associated with the transformational leadership dimensions of idealized influence (β = 0.23, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.04) and individualized consideration (β = 0.26, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.06).

Significantly, the personality dimensions of emotional stability (β = 0.31, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.08), and openness (β = 0.26, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.06) were also both found to be positively associated with teamwork and similarly with managing conflict (emotional stability [β = 0 .27, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.15]; openness [β = 0.38, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.08]). Openness was also significantly related to the project management competence of attentiveness (β = 0.79, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.04), explaining an additional 4% variation. Partial support was therefore found for hypothesis 5.

In addition it should be noted that personality attributes were found to be significantly associated with all four transformational leadership dimensions. Both extraversion (β = 0.39, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.13) and conscientiousness (β = 0.25, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.06) were significantly associated with idealized influence. Extraversion (β = 0.22, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.03) and openness (β = 0.42, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.20) were strongly associated with inspirational motivation. Openness (β = 0.48, p < 0.000, ΔR2 = 0.24), emotional stability (β = 0.44, p < 0.000, ΔR2 = 0.20), and extraversion (β = 0.24, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.04) were strongly associated with intellectual stimulation. Openness (β = 0.47, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.20) and conscientiousness (β = 0.27, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.06) were both significantly associated with individualized consideration. Four out of the five measures of personality were found to be associated with the overall transformational leadership scale: openness (β = 0.48, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.26), emotional stability (β = 0.31, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.10), extraversion (β = 0.31, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.08), and conscientiousness (β = 0.20, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.03). Together personality characteristics were found to account for 26% variation in the measure of overall transformational leadership behavior.

3.6 Discussion

The results from this study take forward our understanding of the role that emotional intelligence may play in projects in two major ways. The first concerns the demonstration of relationships between aspects of the individual differences associated with emotional intelligence and project manager competences that have been suggested to be important for successful outcomes in projects. Both the emotional intelligence ability, using emotions to facilitate thinking, and an overall measure of EI ability were found to be associated with the project manager competences of teamwork and managing conflict, respectively. Previously Druskat and Druskat (2006) have suggested that competences in these two areas are especially important for successful project outcomes due to the specific nature of projects. More significantly, they suggested that emotional intelligence is likely to underpin behaviors associated with these competences. This study is the first to offer some empirical support for this proposition. Of importance, both of these areas of emotional intelligence were found to provide additional explanatory power in these competences after controlling for both cognitive ability and personality, with the ability, using emotions to facilitate thinking, and overall EI ability accounting for an additional 7% and 6% variation in teamwork and managing conflict competences, respectively.

These findings are also in broad support of previous findings in the literature that have found significant relationships using ability conceptualizations of emotional intelligence and the use of better conflict management strategies (Jordan & Troth, 2004) as well as the few studies that have investigated their relationships with key behaviors associated with teamwork (Clarke, forthcoming; Ilarda & Findlay, 2006). Ilarda and Findlay (2006), for example, conducted a study of 134 individuals working in teams across a range of industrial sectors and found that emotional intelligence was significantly associated with a propensity for teamwork. More recently, Clarke (forthcoming), found significant relationships between the two emotional intelligence abilities, using emotions to facilitate thinking and managing emotions, and interpersonal team behaviors (associated with managing conflict and promoting positive affect) in a student population. Importantly, that study also found no significant relationship between these interpersonal team behaviors and cognitive ability as measured by a student's grade point average scores. The finding obtained from this current study, that cognitive ability was not associated with either of these two project manager competences, would therefore seem to offer some support for the view that cognitive ability plays a far more limited role in these particular relationship management behaviors.

The study also found a significant positive relationship between empathy and the project manager competence of attentiveness. This competence captures key behaviors associated with: engaging with project members in order to build strong relationships, responding to their concerns, and building positive attitudes for project success. The significance of empathy for developing close interpersonal bonds and supportive relationships has been recognized in the psychology literature for some time (Gladstein, 1983; Goldstein & Michaels, 1985; Rogers, 1975). More recently, it has also been linked to effective leader behaviors, such as showing consideration and attentiveness to the needs of followers (House & Podsakoff, 1994; Yukl, 1998). A number of authors have suggested that emotional abilities, such as perceiving and understanding emotions in others, may underpin empathy (Ashkanasy & Tse, 2000; Cooper & Sawaf, 1997). It may well be that the failure to find any significant relationships between emotional intelligence abilities and this project manager competence is due to the fact that they are mediated by empathy. The failure to find any significant relationships between personality and attentiveness was surprising since openness and agreeableness might be expected to be associated with showing considerate and attentive behaviors. Both of these personality dimensions have also been shown to be moderately related to empathy (Davies, Stankov, & Roberts, 1998). It is possible that the relatively small sample in the study placed constraints on the statistical tests used, thereby accounting for the failure to determine any effects.

This could similarly explain the failure to find any significant relationships between any of the independent and control variables and the project manager competence of communication. The measure used was found to have good reliability (α = 0.70) and captured behaviors associated with both informal communication and understanding communication from others involved in the project. Emotional intelligence abilities are believed to be associated with more effective communication through emotional expressivity and in recognizing the emotional content of others’ communication (emotional sensitivity) (Morand, 2001; Riggio & Reichard, 2008). Communication has been identified as a chief factor associated with successful outcomes in projects (Kerzner, 2001; Lester, 1998; Munns & Bjerimi, 1996) associated with a wide range of project manager behaviors. These extend far beyond face-to-face communication and involve a myriad of communication modes available. It may be that the measure of project manager competence utilized here is far too broad in its domain to sufficiently capture the type of communication more likely to be associated with either emotional intelligence or empathy. Previous research of relationships between personality and nonverbal forms of communication has also been mixed (Cunningham & Elmhurst, 1977; Gillford, 2006), which could also explain the failure to find any relationships in relation to the personality measures here.

The second major contribution of the study is that this is the first study to show a relationship between emotional intelligence abilities and transformational leadership, after controlling for both cognitive ability and personality. Whereas a number of studies have previously found a significant relationship between EI and transformational leadership (e.g,. Barling, Slater, & Kelloway, 2000; Butler & Chinowsky, 2006; Mandell & Pherwani, 2003; Sivananthan & Fekken, 2002) most of these have used mixed model measures of EI that have been criticized for sharing a considerable degree of overlap with existing personality measures (Brackett & Mayer, 2003; Dawda & Hart, 2000). To date, only four studies have appeared in the literature that have used an ability-derived measure of emotional intelligence to examine relationships with leadership (Downey, Papageorgiou, & Stough, 2005; Kerr, Garvin, Heaton, & Boyle, 2006; Leban & Zulauf, 2004; Rosete & Ciarrochi, 2005). Of these, only the study by Leban & Zulauf (2004) examined the relationship with emotional intelligence and transformational leadership measures and this was in a project management context. They found a significant relationship between participants’ overall EI score and the transformational leadership dimension of inspirational motivation. Again, a limitation with the study was the failure to control for both cognitive ability and personality. This is problematic since a wide range of personal characteristics have previously been found to be associated with transformational leadership (Atwater & Yammarino, 1993; Bommer, Rubin, & Baldwin, 2004; Bono & Judge, 2004).

Indeed, significant relationships were also found between personality measures and transformational leadership. Extraversion and conscientiousness were associated with the dimension of idealized influence. Extraversion and openness were associated with the dimension of inspirational motivation. Extraversion, emotional stability, and openness were associated with intellectual stimulation. Finally, conscientiousness and openness were associated with the fourth dimension of individualized consideration. It is important to note that the emotional ability, using emotions to facilitate thinking, was found to account for a further 4% in variation of both the transformational leadership dimensions of idealized influence and individualized consideration after first controlling for personality.

This is the first study then that has shown the additional predictive power of emotional intelligence abilities to account for variations in these transformational leadership dimensions after personality. Rosete and Ciarrochi (2005) also found the emotional ability, perceiving emotions, to account for an additional variation of 10% in leadership scores after controlling for personality (using the 16PF). However, this was based on performance management ratings of leadership and not specifically transformational leadership behaviors. The ability to use emotions to facilitate thinking may be important in order to foster high-quality, interpersonal relationships between leaders and followers (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). This ability should enable the project manager to better discern the emotional climate among other project members, and then assist them in thinking how best to respond to their needs and concerns, for example, through promoting more positive feelings of optimism and excitement after a setback. This capacity for promoting positive affect is seen as a key element associated with building trust (Jones & George, 1998). The transformational leadership behavior dimensions of both individualized consideration and idealized influence would seem to be closely associated with both of these areas (Bass, Avolio, Jung, & Berson, 2003; Gardner & Avolio, 1998). The finding here that the emotional ability, Using Emotions to Facilitate Thinking, accounts for incremental variation in these transformational leadership behaviors after personality, is therefore significant.

3.7 Conclusions

To date, only five studies have appeared in the literature investigating the concept of emotional intelligence specifically within the context of projects. In these studies, emotional intelligence has been suggested as particularly important in projects due to the nature of this form of work organization. This places specific emphasis on project manager behaviors associated with communication, teamwork, attentiveness, and managing conflict as being important to successful project outcomes. This is the first study to use the ability measure of EI and examine its relationship with specific behaviors that are associated with project manager competence in these areas. Both the emotional intelligence ability, using emotions to facilitate thinking, and the participants’ overall EI scores were found to be significantly associated with the competences of teamwork and managing conflict, respectively. Project managers’ empathy was also found to be significantly associated with the competence of attentiveness. In addition, the emotional intelligence ability was also found to be significantly associated with the transformational leadership dimensions of idealized influence and individualized consideration. In each instance, these EI dimensions were found to offer additional predictive capacity in both the competence and leadership behavioral domains after controlling for both cognitive ability and personality.

The results suggest that emotional intelligence abilities and empathy offer a means to further explain aspects of individual differences between project managers that can influence their performance in projects. However, the results need to be interpreted within the limitations associated with the study. The most significant concern is the approach used to measure both project manager competences and transformational leadership behaviors. This relied on self-report ratings from those taking part in the study. Subjective self-ratings of performance have consistently been found to be more lenient than those provided by observers (Atwater & Yammarino, 1992; Carless, Mann, & Wearing, 1998; Mabe & West, 1982) and a number of authors have urged caution in relying upon such measures within organizational research (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998; Spector, 1994). This has often resulted in researchers using peer report measures, believing these offer improved validity in performance measures. However, recent research suggests that the picture is somewhat more complicated. Recent research by Atkins and Wood (2002) comparing self, peer, and supervisor ratings of performance with objective measures of performance in an assessment center found that peer and supervisor ratings of performance were not always predictive of objective performance measures. In particular, the highest peer ratings were found to be associated with poor performance. Higher self- and peer ratings were also predictive of higher supervisor ratings. However, when compared to the objective measure of performance, both the supervisors and peers overestimated performance. Instead, highest performance was associated with low self-scores and modest peer scores. It is not all clear that using aggregated peer measures of either project manager competence or transformational leadership behavior would necessarily have given more valid performance scores than those of self-ratings. Nonetheless, the constraints imposed in conducting a pilot study precluded the use of more objective performance measures which suggest the findings should be treated as only suggestive at this stage.

A further major limitation of the study is again the problems of validity due to common method variance (Spector, 1987). However, following recommendations by Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Podsakoff, and Lee (2003), a number of procedural strategies were used to attempt to minimize these effects. The first of these related to a proximal separation of measures. Measures were obtained from participants who completed two tests and one questionnaire. The two tests measured EI and cognitive ability, and presented items in a different format to the questionnaire. In addition, where scales were used to assess differing measures, these varied in length including 5, 7, and 9-point scales. A psychological separation was also made between these measures in that individuals had to log into three different websites each with their own pass codes in order to complete each measure. Instructions given to respondents were to complete each of the instruments at different sittings over the 2- week data collection period, thereby also providing a temporal separation between measures. Assurances of confidentiality were also made in order to reduce problems associated with social desirability in answering. It should also be borne in mind that the study only used cross-sectional data to analyze relationships between emotional intelligence and dependent measures, thus precluding any definitive statements relating to causality.

The final set of limitations relates to both the measures used and the sample. Relatively low reliabilities were found for a number of scales used in the study. A reliability coefficient of only 0.55 was obtained for the managing emotions ability branch of EI. This is lower than has been reported in previous studies and suggests that there were problems encountered here with the validity of this measure. Previously Clarke (2006a) raised concerns specifically regarding the use of a test to satisfactorily capture an ability, such as managing emotions, where strategies used are so varied and dependent on context. This may represent a wider problem with the measure itself or may be related to the particular sample. The low reliability may then have accounted for the failure to detect and significant relationships with this particular branch of EI. In addition, the two measures of transformational leadership dimensions representing inspirational motivation and individualized consideration similarly were found to have low reliabilities of 0.52 and 0.55, respectively. The use of self-report measures may well account for these low reliabilities. However, it does suggest that the significant relationship found between the emotional ability, using emotions to facilitate thinking, and individualized consideration should be treated with some degree of caution. It should also be noted that no significant correlations were found between general mental ability and any of the emotional intelligence measures used in the study. Previous researchers have reported significant moderate correlations between intelligence and EI ability measures (Lopes, Salovey, & Strauss, 2003) and Rode et al. (2007) reported a correlation of r = 0.20, p < 0.01 between GMA and the total EI ability score using the same GMA measure used herein. The failure to find any significant relationships, therefore, raises some concern. One potential explanation could lie with the measure of IQ used in the study. A number of participants in the study indicated that they had problems with the American English used on the test, particularly in the verbal reasoning domains which they believed impeded their performance in this time-constrained test. This may suggest that the general ability scores obtained are subject to some bias and may not reflect accurate measures of ability.

In addition, the relatively modest sample size of 67 is also a limitation here. This may have increased the risk of statistical Type I errors where results are found to be significant. Finally, some further mention should be made of the population upon which this study is based. These were drawn from two organizations involved in arts, education, research and development, and construction, as well as a small number from the UK Chapter of the Project Management Institute who are predominantly involved in consultancy and professional services. This arguably represents a far more diverse project management base than had been traditionally studied. In addition, just over a quarter of these (27%) were certified in project management. The extent to which the results found here are able to be generalized beyond this particular sample to project managers more widely operating in traditional project management industries and sectors is therefore unknown.