Chapter 8

Writing Good or Well: Adjectives and Adverbs

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Distinguishing between adjectives and adverbs

Distinguishing between adjectives and adverbs

![]() Deciding whether an adjective or an adverb is appropriate

Deciding whether an adjective or an adverb is appropriate

![]() Selecting articles: a or an or the

Selecting articles: a or an or the

![]() Choosing good or well and bad or badly

Choosing good or well and bad or badly

![]() Creating comparisons with adjectives and adverbs

Creating comparisons with adjectives and adverbs

Do you write good or well — and what’s the difference? Does your snack break feature a apple or an apple or the apple? Is your cold worse or more bad? If you’re stewing over these questions, you have problems … specifically, the problems in this chapter. Here you can practice choosing between two types of descriptions, adjectives and adverbs. This chapter also helps you figure out whether a, an, or the is appropriate in any given situation. Finally, here you practice making comparisons with adjectives and adverbs.

Identifying Adjectives and Adverbs

Adjectives describe nouns — words that name a person, thing, place, or idea. They also describe pronouns, which are words that stand in for nouns (other, someone, they, and similar words). Adjectives usually precede the word they describe, but not always. In the following sentence the adjectives are italicized:

The rubber duck with his lovely orange bill sailed over the murky bath water. (Rubber describes duck; lovely and orange describe bill; murky and bath describe water.)

An adverb, on the other hand, describes a verb, usually telling how, where, when, or why an action took place. Adverbs also indicate the intensity of another descriptive word or add information about another description. In the following sentence the adverbs are italicized:

The alligator snapped furiously as the duck quite violently flapped his wings. (Furiously describes snapped; violently describes flapped, quite describes violently.)

When you’re speaking or writing, you should take care to use adjectives and adverbs correctly. But first you have to recognize them. To locate an adjective, check each noun and pronoun. Ask which one? what kind? how many? about each noun or pronoun. If you get an answer, you’ve found an adjective. To locate an adverb, first check every verb. Ask how? when? where? why? If you get an answer, you’ve identified an adverb. Also look at the adjectives. Does any word intensify (very, for example) or weaken (less, perhaps) that description? That’s an adverb at work.

Q. Underline every adjective or adverb in each sentence. Write ADJ above an adjective and ADV above an adverb.

Q. Underline every adjective or adverb in each sentence. Write ADJ above an adjective and ADV above an adverb.

Debbie slowly crosses the dark street followed by three little dogs.

A. slowly (ADV), dark (ADJ), three (ADJ), little (ADJ). How does Debbie cross? Slowly. Slowly is an adverb describing the verb crosses. What kind of street? The dark street. Dark is an adjective describing the noun street. In case you're wondering, the is also a type of adjective — an article. You can find out more about articles later in this chapter. For now, ignore a, an, and the. What kind of dogs? Little dogs. Little is an adjective describing the noun dogs. How many dogs? three dogs. Three is an adjective describing dogs.

1 Slipping onto her comfortable, old sofa, Lola quickly grabbed the black plastic remote.

____________________________________________________

2 “I arrived early, because I desperately want to watch that new motorcycle show,” she said to George.

____________________________________________________

3 George, who was intently watching the latest news, turned away silently.

____________________________________________________

4 Everyone present knew that Lola would get her way. She always did!

____________________________________________________

5 George struggled fiercely, but he was curious about the show, which featured a different motorcycle weekly.

____________________________________________________

6 If he held out a little longer, he knew that Lola would offer something nice to him.

____________________________________________________

7 Lola's purse always held a few goodies, and George was extremely fond of chocolate brownies.

____________________________________________________

8 He could almost taste the sweet, hazelnut flavor that Lola sometimes added to the packaged brownie mix.

____________________________________________________

9 George sighed loudly and waved a long, thin hand.

____________________________________________________

10 “You can watch anything good,” he remarked in a low, defeated voice, “but first give me two brownies.”

____________________________________________________

The Right Place at the Right Time: Placing Adjectives and Adverbs

You don’t need to stick labels on adjectives and adverbs, but you do need to send the right word to the right place in order to avoid arrest by the grammar police. A few wonderful words (fast, short, last, and likely, for example) function as both adjectives and adverbs, but for the most part, adjectives and adverbs are not interchangeable. In this section you choose between adjectives and adverbs and insert them into sentences.

Q. The water level dropped (slow/slowly), but the (intense/intensely) alligator-duck quarrel went on and on.

A. slowly, intense. How did the water drop? The word you want from the first parentheses must describe an action (the verb dropped), so the adverb slowly wins the prize. Next up is a description of a quarrel, a thing, so the adjective intense does the job.

11 The alligator, a (loyal/loyally) member of the Union of Fictional Creatures, (sure/surely) resented the cartoon duck’s presence near the drainpipe.

12 “How dare you invade my (personal/personally) plumbing?” inquired the alligator (angry/ angrily).

13 “You don’t have to be (nasty/nastily)!” replied the duck.

14 The two creatures (swift/swiftly) circled each other, both looking for a (clear/clearly) advantage.

15 “You are (extreme/extremely) territorial about these pipes,” added the duck.

16 The alligator retreated (fearful/fearfully) as the duck quacked (sharp/sharply).

17 Just then a (poor/poorly) dressed figure appeared in the doorway.

18 The creature whipped out a bullhorn and a sword that was (near/nearly) five feet in length.

19 When he screamed into the bullhorn, the sound bounced (easy, easily) off the tiled walls.

20 “Listen!” he ordered (forceful/forcefully). “The alligator should retreat (quick/quickly) to the sewer and the duck to the shelf.”

21 Having given this order, the (Abominable/Abominably) Snowman seemed (happy/happily).

22 The fight in the bathtub had made him (real/really) angry.

23 “You (sure/surely) can’t deny that we imaginary creatures must stick together,” explained the Snowman.

24 Recognizing the (accurate/accurately) statement, the duck apologized to the alligator.

25 The alligator retreated to the sewer, where he found a (lovely/lovingly) lizard with an urge to party.

26 “Come (quick/quickly),” the alligator shouted (loud/loudly) to the duck.

27 The duck left the tub (happy/happily) because he thought he had found a (new/newly) friend.

28 The alligator celebrated (noisy/noisily) because he had discovered an enemy (dumb/dumbly) enough to enter the sewer, the alligator’s turf.

29 “Walk (safe/safely),” murmured the gator, as the duck entered a (particular/particularly) narrow tunnel.

30 The duck waddled (careful/carefully), beginning to suspect (serious/seriously) danger.

How’s It Going? Choosing Between Good/ Well and Bad/Badly

For some reason, adjective and adverb pairs that pass judgment (good and well, bad and badly) cause a lot of trouble. Here’s a quick guide: Good and bad are adjectives, so they have to describe nouns — people, places, things, or ideas. (“I gave a good report to the boss.” The adjective good describes the noun report. “The bad dog ate my slippers this morning.” The adjective bad describes the noun dog.) Well and badly are adverbs used to describe action. (“In my opinion, the report was particularly well written.” The adverb well describes the verb written. “The dog slept badly after his slipper-fest.” The adverb badly describes the verb slept.) Well and badly also describe other descriptions. In the expression a well-written essay, for example, well describes written, which describes essay.

When a description follows a verb, danger lurks. You have to decide whether the description gives information about the verb or about the person/thing who is doing the action or is in the state of being. If the description describes the verb, go for an adverb. If it describes the person/thing (the subject, in grammatical terms), opt for the adjective.

Q. The trainer works (good/well) with all types of dogs, especially those that don’t outweigh him.

A. well. How does the trainer work? The word you need must be an adverb because you’re giving information about an action (work), not a noun.

31 My dog Caramel barks when he’s run (good/well) during his daily race with the letter carrier.

32 The letter carrier likes Caramel and feels (bad/badly) about beating him when they race.

33 Caramel tends to bite the poor guy whenever the race doesn’t turn out (good/well).

34 Caramel’s owner named him after a type of candy she thinks is (good/well).

35 The letter carrier thinks high-calorie snacks are (bad/badly).

36 He eats organic sprouts and wheat germ for lunch, though his meal tastes (bad/badly).

37 Caramel once caught a corner of a dog-food bag and chewed off a (good/well) bit.

38 Resisting the urge to barf, Caramel ate (bad/badly), according to his doggie standards.

39 Caramel, who didn’t feel (good/well), barked quite a bit that day.

40 Tired of the din, his owner confiscated the kibble and screamed, “(Bad/Badly) dog!”

Mastering the Art of Articles

Three little words — a, an, and the — pop up in just about every English sentence. Sometimes (like my relatives) they show up where they shouldn’t. Technically, these three words are adjectives, but they belong to the subcategory of articles. As always, forget about the terminology. Just know how to use them:

- The refers to something specific. When you say that you want the book, you’re implying one particular text, even if you haven’t named it. The attaches nicely to both singular and plural words.

- A and an are more general in meaning and work only with singular words. If you want a book, you’re willing to read anything. A precedes words beginning with consonants and words that begin with a long u sound, similar to what you hear when you say “you.” An comes before words beginning with vowels (an ant, an encyclopedia, an uncle) except for the long u sound (a university). An also precedes words that sound as if they begin with a vowel (hour, for example) because the initial consonant is silent.

Q. When Lulu asked to see ________________ wedding pictures, she didn’t expect Annie to put on ________________ twelve-hour slide show.

A. the, a. In the first half of the sentence, Lulu is asking for something specific. Also, wedding pictures is a plural expression, so a and an are out of the question. In the second half of the sentence, something more general is appropriate. Because twelve begins with the consonant t, a is the article of choice.

41 Although Lulu was mostly bored out of her mind, she did like ________________ picture of Annie’s Uncle Fred snoring in the back of the church.

42 ________________ nearby guest, one of several attempting to plug up their ears, can be seen poking Uncle Fred’s ribs.

43 At Annie’s wedding, Uncle Fred wore ________________ antique bow tie that he bought in ________________ department store next door to his apartment building.

44 ________________ clerk who sold ________________ tie to Uncle Fred secretly inserted ________________ microphone and ________________ miniature radio transmitter.

45 Uncle Fred’s snores were broadcast by ________________ obscure radio station that specializes in embarrassing moments.

46 Annie, who didn’t want to invite Uncle Fred but was forced to do so by her mother, placed ________________ buzzer under his seat.

47 Annie’s plan was to zap him whenever he snored too loudly; unfortunately, Fred chose ________________ different seat.

For Better or Worse: Forming Comparisons

If human beings weren’t so tempted to compare their situations with others’, life (and grammar) would be a lot easier. In this section, I tell you everything you need to know about creating comparisons, whether they show up as one word (higher, farthest) or two words (more beautiful, least sensible). For information on longer comparisons, see Chapter 19.

Visiting the -ER (and the -EST): One- or two-word comparisons

Adjectives and adverbs serve as the basic construction material for comparisons. Regular unadorned adjectives and adverbs are the base upon which two types of comparisons may be made: the comparative and the superlative. Comparatives (dumber, smarter, neater, more interesting, less available, and the like) deal with only two elements. Superlatives (dumbest, smartest, neatest, most interesting, least available, and so forth) identify the extreme in a group of three or more. To create simple comparisons, follow these guidelines:

- Tack -er onto the end of a one-syllable descriptive word to create a positive comparative form. When I say positive, I mean that the first term of the comparison comes out on top, as in “parakeets are noisier than canaries,” a statement that gives more volume to parakeets. Occasionally a two-syllable word forms a comparative this way also (lovelier, for example).

- To make the comparative forms of a word with more than one syllable, you generally use more or less, not -er. This guideline doesn’t hold true for every word in the dictionary, but it’s valid for most. Therefore, you’d say that “canaries are more popular than parakeets,” not “canaries are popularer.” Just to be clear: popularer isn’t a word!

- Glue -est to one-syllable words to make a positive superlative. A positive superlative gives the advantage to the element cited in the comparison. For example, canaries have the edge in “canaries are the finest singers in the bird world.” Also, a few two-syllable words use -est to create a superlative (such as loneliest).

- Add most or least to longer words to create a superlative. Again, the definition of longer isn’t set in stone, but a word containing two or more syllables, such as beautiful, generally qualifies as long. The superlative forms are most beautiful or least beautiful.

- Negative comparative and superlative forms always rely on two words. If you want to state that something is less or least, you have to use those words and not a tacked-on syllable. Therefore, “the canary’s song is less pretty when he has a head cold,” and “my parakeets are least annoying when they’re sleeping.”

- Check the dictionary if you’re not sure of the correct form. The entry for the plain adjective or adverb normally includes the comparative and superlative forms, if they’re single words. If you don’t see a listing for another form of the word, take the less/more, least/most option.

A few comparatives and superlatives are irregular. I discuss these in the next section, “Going from bad to worse (and good to better): Irregular comparisons.”

Q. Helen is the __________________ of all the women living in Troy, New York. (beautiful)

A. most beautiful. The sentence compares Helen to other women in Troy, New York. Comparing more than two elements requires the superlative form. Because beautiful is a long word, most creates a positive comparison. (Least beautiful is the negative version.)

48 Helen, who manages the billing for an auto parts company, is hoping for a transfer to the Paris office, where the salaries are __________________ than in New York but the night life is __________________. (low, lively)

49 Helen’s boss claims that she is the __________________ and __________________ of all his employees. (efficient, valuable)

50 His secretary, however, has measured everyone’s output of P-345 forms and concluded that Helen is __________________ and __________________ than Natalie, Helen’s assistant. (slow, accurate)

51 Natalie prefers to type her P-345s because she thinks the result is __________________ and __________________ than handwritten work. (neat, professional)

52 Helen notes that everyone else in the office writes __________________ than Natalie, whose penmanship has been compared to random scratches from a blind chicken; however, Natalie types __________________. (legibly, fast)

53 Helen has been angry with Natalie ever since her assistant declared that Helen’s coffee was __________________ and __________________ than the tea that Natalie brought to the office. (drinkable, tasty)

54 Helen countered with the claim that Natalie brewed tea __________________ than the office rules allow, a practice that makes her __________________ than Helen. (frequently, productive)

55 Other workers are trying to stay out of the feud; they know that both women are capable of making the work day __________________ and __________________ than it is now. (long, boring)

56 The __________________ moment in the argument came when Natalie claimed that Helen’s toy duck “squawked __________________ than Helen herself.” (petty, annoyingly)

57 That duck was the __________________ and __________________ toy in the entire store! (expensive, cute)

58 Knowing about Helen’s transfer request, I selected a duck that sounded __________________ and __________________ than the average American rubber duck. (international, interesting)

59 The clerk told me my request was the __________________ he had ever encountered, but because he holds himself to the __________________ standards of customer service, he did not laugh at me. (silly, high)

60 I replied that I preferred to deal with store clerks who were __________________ and __________________ than he. (snobby, knowledgeable)

61 Anyway, Helen’s transfer wasn’t approved, and she is in the __________________ mood imaginable, even __________________ than she was when her desk caught fire. (nasty, annoyed)

62 We all skirt Natalie’s desk __________________ than Helen’s, because Natalie is even __________________ than Helen about the refusal. (widely, upset)

63 Natalie, who considers herself the __________________ person in the company, wanted a promotion to Helen’s rank or an even __________________ job. (essential, important)

64 Larry is sure that he would have gotten the promotion because he is the __________________ and __________________ of all of us in his donations to the Party Fund. (generous, creative)

65 “Natalie bakes a couple of cupcakes,” he commented __________________ than a boxing champion, “and the boss thinks she’s executive material.” (forcefully)

66 “I, on the other hand, am the __________________ of the three clerks in my office,” he continued, “and I am absent __________________ than everyone else.” (professional, often)

67 When I left the office, Natalie and Larry were arm wrestling to see who was __________________, and Helen was surfing Internet job sites __________________ than usual. (strong, carefully)

Going from bad to worse (and good to better): Irregular comparisons

A couple of basic descriptions form comparisons irregularly. Irregulars don’t add -er or more/less to create the comparative form, a comparison between two elements. Nor do irregulars tack on -est or most/least to point out the top or bottom of a group of more than two, also known as the superlative form of comparisons. (See the preceding section, “Visiting the -ER (and the -EST),” for more information on comparatives and superlatives.) Instead, irregular comparisons follow their own strange path, as you can see in Table 8-1.

Table 8-1 Forms of Irregular Comparisons

|

Description |

Comparative |

Superlative |

|

Good or well |

Better |

Best |

|

Bad or ill |

Worse |

Worst |

|

Much or many |

More |

Most |

Q. Edgar’s scrapbook, which contains souvenirs from his trip to Watch Repair Camp, is the __________________ example of a boring book that I have ever seen. (good)

A. best. Once you mention the top or bottom experience of a lifetime, you’re in the superlative column. Because goodest isn’t a word, best is the one you want.

68 Edgar explains his souvenirs in __________________ detail than anyone would ever want to hear. (much)

69 Bored listeners believe that the __________________ item in his scrapbook is a set of gears, each of which Edgar can discuss for hours. (bad)

70 On the bright side, everyone knows that Edgar’s watch repair skills are __________________ than the jewelers’ downtown. (good)

71 When he has the flu, Edgar actually feels __________________ when he hears about a broken watch. (bad)

72 Although he is only nine years old, Edgar has the __________________ timepieces of anyone in his fourth grade class, including the teacher. (many)

73 The classroom clock functions fairly well, but Ms. Appleby relies on Edgar to make it run even __________________. (well)

74 Edgar’s scrapbook also contains three samples of watch oil; Edgar thinks Time-Ola Oil is the __________________ choice. (good)

75 Unfortunately, last week Edgar let a little oil drip onto his lunch and became sick; a few hours later he felt __________________ and had to call the doctor. (ill)

76 “Time-Ola Oil is the __________________ of all the poisons,” cried the doctor. (bad)

77 “But it’s the __________________ for watches,” whispered Edgar. (good)

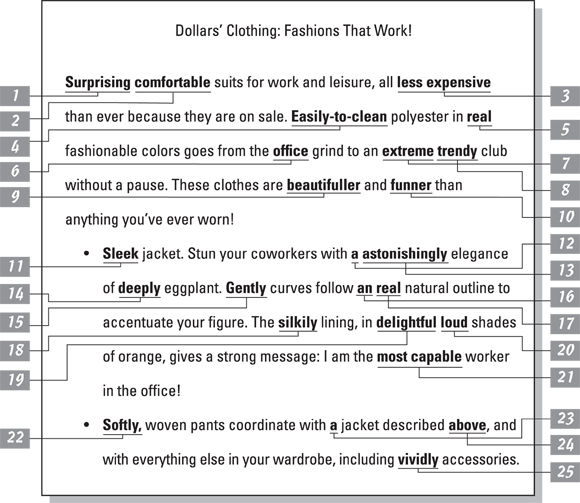

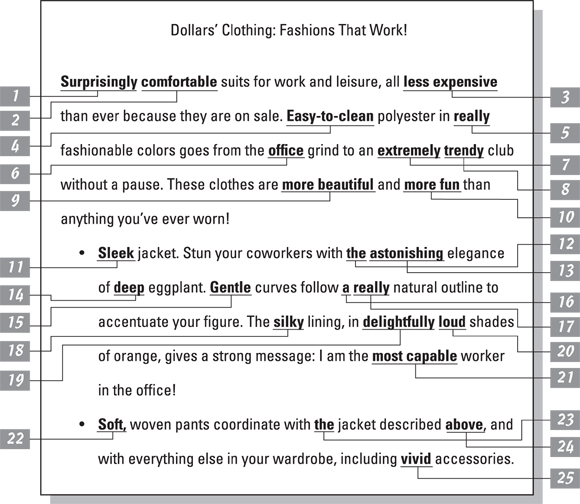

Calling All Overachievers: Extra Practice with Descriptors

Answers to Adjective and Adverb Problems

I hope the challenging exercises in this short chapter on descriptive words didn’t give you too much trouble. Find out how you did by comparing your work to the following answers.

1 comfortable (ADJ), old (ADJ), quickly (ADV), black (ADJ), plastic (ADJ). The adjectives comfortable and old tell you what kind of sofa. The adverb quickly tells you how Lola grabbed. The adjectives black and plastic tell you what kind of remote.

2 early (ADV), desperately (ADV), new (ADJ), motorcycle (ADJ). The adverb early tells you when she arrived. The adverb desperately tells you how she wanted. The adjectives new and motorcycle answer the question what kind of show?

3 intently (ADV), latest (ADJ), away (ADV) silently (ADV). The adverb intently answers the question watching how? Latest, an adjective, tells you what kind of news. Away and silently, both adverbs, answer turned how?

4 present (ADJ) always (ADV). Present is an adjective describing the pronoun everyone. This adjective breaks the pattern because it appears after the word it describes, not before. It also doesn't fit perfectly into the adjective questions (how many? which one? what kind?), but it serves the same purpose. It limits the meaning of everyone. You aren't talking about everyone in the universe, just everyone present. Always answers the question did when? and is therefore an adverb. You may be wondering about her. Her is a possessive pronoun, not an adjective.

5 fiercely (ADV), curious (ADJ) different (ADJ), weekly (ADV). Fiercely, an adverb, answers the question struggled how? Curious is an adjective appearing after a linking verb (was). Curious describes the pronoun he. Different is an adjective answering the question which motorcycle? Weekly, an adverb, answers the question features when?

6 little (ADV), longer (ADV), nice (ADJ). The adverb little changes the intensity of another adverb, longer. Together they answer the question held out when? Nice, an adjective, describes the pronoun something.

7 few (ADJ), extremely (ADV), fond (ADJ), chocolate (ADJ). How many goodies? A few goodies. Few is an adjective. (A is an article, which is technically an adjective.) The adverb extremely intensifies the meaning of the adjective fond. Fond, which appears after a linking verb, describes George. Extremely answers the question how fond? The adjective chocolate answers what kind of brownies?

8 almost (ADV) sweet (ADJ), hazelnut (ADJ) sometimes (ADV), packaged (ADJ), brownie (ADJ). The adverb almost answers the question taste how? What kind of flavor? Sweet, hazelnut. Both are adjectives. Added when? Sometimes — an adverb. What kind of mix? Packaged, brownie mix. Both packaged and brownie are adjectives.

9 loudly (ADV), long (ADJ), thin (ADJ). Loudly, an adverb, answers sighed how? Long and thin, adjectives, tell you what kind of hand.

10 good (ADJ), low (ADJ), defeated (ADJ), first (ADV), two (ADV). Good is an adjective describing the pronoun anything. Low and defeated are adjectives answering what kind of voice? First is an adverb answering give when? Two is an adjective answering how many brownies?

11 loyal, surely. What kind of member is the alligator? A loyal member. Because you’re describing a noun (member), you need the adjective loyal. In the second part of the sentence, the adverb surely explains how the duck’s presence was resented. Resented is a verb and must be described by an adverb.

12 personal, angrily. In the first part of the sentence, personal describes a thing (plumbing). How did the alligator inquire? Angrily. The adverb tells about the verb, inquire.

13 nasty. The adjective nasty describes you. Of course I don’t mean you, the reader. You earned my undying affection by buying this book. The you in the sentence is nasty!

14 swiftly, clear. The adverb swiftly describes the action of circling. The adjective clear explains what kind of advantage the creatures were seeking.

15 extremely. The adverb extremely clarifies the intensity of the descriptive word territorial. (If you absolutely have to know, territorial is an adjective describing you.)

16 fearfully, sharply. Both of these adverbs tell how the actions (retreated and quacked) were performed.

17 poorly. The adverb poorly gives information about the descriptive word dressed.

18 nearly. This was a tough question, and if you got it right, treat yourself to a spa day. The expression five feet is a description of the sword. The adverb nearly gives additional information about the description five feet in length.

19 easily. The adverb easily describes the verb bounced.

20 forcefully, quickly. The adverb forcefully tells how he ordered, a verb. The adverb quickly describes how the alligator should retreat.

21 Abominable, happy. You can cheat on the first part of this one just by knowing the name of the monster that supposedly stalks the Himalayas, but you can also figure out the answer using grammar. A snowman is a thing (or a person) and thus a noun. Adjectives describe nouns, so abominable does the trick. In the second half you need an adjective to describe the snowman, who was happy. You aren’t describing the action of seeming, so an adverb isn’t correct.

22 really. This sentence presents two commonly confused words. Because angry is an adjective, you need an adverb to indicate its intensity, and really fills the bill.

23 surely. That horse in the fifth race might be a sure thing, because thing is a noun and you need an adjective to describe it. But the verb deny must be described by an adverb, so surely is the one you want.

24 accurate. Statement is a noun that must be described by the adjective accurate.

25 lovely. A lizard is a noun, which may be described by the adjective lovely but not the adverb lovingly. Incidentally, lovely isn’t an adverb, despite the fact that it ends with -ly.

26 quickly, loudly. The adverb quickly describes the verb come, and the adverb loudly describes the verb shouted.

27 happy, new. This sentence presents a puzzle. Are you talking about the duck’s mood or the way in which he left the tub? The two are related, of course, but the mood is the primary meaning, so the adjective happy is the better choice to describe duck. The adjective new describes the noun friend.

28 noisily, dumb. The adverb noisily tells you how the alligator celebrated. Because celebrated is a verb, you need an adverb. The adjective dumb tells you about the noun enemy. Most, but not all, adjectives are in front of the words they describe, but in this case the adjective follows the noun.

29 safely, particularly. The adverb safely tells you about the verb walk. The second answer is also an adverb, because particularly explains how narrow the tunnel is.

30 carefully, serious. The adverb carefully explains how the duck waddled, and waddled is a verb. Danger, a noun, is described by the adjective serious.

31 well. The adverb well tells you how Caramel has run.

32 bad. This sentence illustrates a common mistake. The description doesn’t tell you anything about the letter carrier’s ability to feel (touching sensation). Instead, it tells you about his state of mind. Because the word is a description of a person, not of an action, you need an adjective, bad. To feel badly implies that you’re wearing mittens and can’t feel anything through the thick cloth.

33 well. The adverb well describes the action to turn out (to result).

34 good. What is her opinion of chocolate caramels? She thinks they are good. The adjective is needed because you’re describing the noun candy.

35 bad. The description bad applies to the snacks, not to the verb are. Hence, an adjective is what you want.

36 bad. The description tells you about his meal, a noun. You need the adjective bad.

37 good. The adjective (good) is attached to a noun (bit).

38 badly. Now you’re talking about the action (ate), so you need an adverb (badly).

39 well. The best response here is well, an adjective that works for health-status statements. Good will do in a pinch, but good is better for psychological or mood statements.

40 Bad. The adjective bad applies to the noun dog.

41 the. The sentence implies that one particular picture caught Lulu’s fancy, so the works nicely here. If you chose a, no problem. The sentence would be a bit less specific but still acceptable. The only true clinker is an, which must precede words beginning with vowels (except for a short u, or uh sound) — a group that doesn’t include picture.

42 A. Because the sentence tells you that several guests are nearby, the doesn’t fit here. The more general a is best.

43 an or the, the. In the first blank you may place either an (which must precede a word beginning with a vowel) or the. In the second blank, the is best because it’s unlikely that Fred is surrounded by several department stores. The is more definitive, pointing out one particular store.

44 The, the, a, a. Lots of blanks in this one! The first two seem more particular (one clerk, one tie), so the fits well. The second two blanks imply that the clerk selected one from a group of many, not a particular microphone or transmitter. The more general article is a, which precedes words beginning with consonants.

45 an. Because the radio station is described as obscure, a word beginning with a vowel, you need an, not a. If you inserted the, don’t cry. That article works here also.

46 a. The word buzzer doesn’t begin with a vowel, so you have to go with a, not an. The more definite the could work, implying that the reader knows that you’re talking about a particular buzzer, not just any buzzer.

47 a. He chose any old seat, not a particular one, so a is what you want.

48 lower, livelier. The comparative form is the way to go because two cities, Paris and New York, are compared. One-syllable words such as low form comparatives with the addition of -er. Most two-syllable words rely on more or less, but lively is an exception.

49 most efficient, most valuable. In choosing the top or bottom rank from a group of three or more, go for superlative. Efficient and valuable, both long words, take most or least. In the context of this sentence, most makes sense.

50 slower, less accurate. Comparing two elements, in this case Helen and Natalie, calls for comparative form. The one-syllable word takes -er, and the longer word relies on less.

51 neater, more professional. Here the sentence compares typing to handwriting, two elements, so the comparative is correct. The one-syllable word becomes comparative with the addition of -er, and the two-syllable word turns into a two-word comparison.

52 more legibly, faster. After you read the word everyone, you may have thought that superlative (the form that deals with comparisons of three or more) was needed. However, this sentence actually compares two elements (Natalie and the group composed of everyone else). Legibly has three syllables, so more creates the comparative form. Because fast is a single syllable, -er does the job.

53 less drinkable, less tasty. In comparing coffee and tea, go for the comparative form. Both more drinkable and less drinkable are correct grammatically, but Helen’s anger more logically flows from a comment about her coffee’s inferiority. Negative comparisons always require two words; here, less tasty does the job.

54 more frequently, less productive. The fight’s getting serious now, isn’t it? Charges and countercharges! Speaking solely of grammar and forgetting about office politics, each description in this sentence is set up in comparison to one other element (how many times Natalie brews tea versus how many times the rules say she can brew tea, Natalie’s productivity versus Helen’s). Because you’re comparing two elements and the descriptions have more than one syllable, go for a two-word comparative.

55 longer, more boring. When you compare two things (how long and boring the day is now and how long and boring it will be if Natalie and Helen get angry), go for the comparative, with -er for the short word and more for the two-syllable word.

56 pettiest, more annoyingly or less annoyingly. The argument had more than two moments, so superlative is what you want. The adjective petty has two syllables, but -est is still appropriate, with the letter y of petty changing to i before the -est. The second blank compares two (the duck and Helen) and thus takes the comparative. I’ll let you decide whether Natalie was insulting Helen or the duck. Grammatically, either form is correct.

57 most expensive, cutest. A store has lots of toys, so to choose the one that has the highest price (the meaning that fits the sentence), go for superlative. Because expensive has three syllables, tacking on most is the way to go. The superlative for a single-syllable word, cute, is formed by adding -est.

58 more international, more interesting. Comparing two items (the sound of the duck you want to buy and the sound of the “average American rubber duck”) calls for comparative, which is created with more because of the length of the adjectives international and interesting.

59 silliest, highest. Out of all the requests, this one is on the top rung. Go for superlative, which is created by changing the y to i and adding -est (resulting in silliest) and adding -est to high, a one-syllable word.

60 less snobby, more knowledgeable. Two elements (he and a group of store clerks, with the group counting as a single item) are being compared here, so comparative is needed. The add-on less does the job for the first answer; more is what you want for the second comparison.

61 nastiest, more annoyed. I can imagine many moods, so the extreme in the group calls for the superlative. The final y changes to i before the -est to create nastiest; in the second blank, more creates a two-word comparative form.

62 more widely, more upset. Employee habits concerning two individuals (Natalie and Helen) are discussed here; comparative does the job.

63 most essential, more important. Natalie is singled out as the extreme in a large group. Hence superlative is the one that fits the first blank. Three-syllable words need most to form the superlative most essential. In the second blank, two jobs are compared — one of Helen’s rank and one that is more important, the comparative form of a long word.

64 most generous, most creative. All includes more than two (both is the preferred term for two), so superlative rules. Go for the two-word form because generous and creative are three-syllable words.

65 more forcefully. This sentence compares his force to that of a boxer. Two things in one comparison give you comparative form, which is created by more.

66 most professional, less often. Choosing one out of three in the first part of the sentence calls for superlative. In the second part of the sentence, the speaker is comparing himself to every other employee, one at a time. Therefore, comparative is appropriate. Because the speaker is bragging, less often makes sense.

67 stronger, more carefully. Natalie and Larry are locked in a fight to the death (okay, to the strained elbow). In the first part of the sentence, the comparison of two elements requires comparative. Because strong is a single syllable, tacking on -er does the trick. The second part of the sentence also compares two elements — the way Natalie usually surfs job sites and the way she surfs in this situation. Go for more carefully, the comparative form.

68 more. Two elements are being compared here: the amount of detail Edgar uses and the amount of detail people want. When comparing two elements, the comparative form rules.

69 worst. The superlative form singles out the extreme (in this case the most boring) item in the scrapbook.

70 better. The sentence pits Edgar’s skills against the skills of one group (the downtown jewelers). Even though the group has several members, the comparison is between two elements — Edgar and the group — so comparative form is what you want.

71 worse. Two states of being are in comparison in this sentence, Edgar’s health before and after he hears about a broken watch. In comparing two things, go for comparative form.

72 most. The superlative form singles out the extreme, in this case Edgar’s timepiece collection, which included a raw-potato clock until it rotted.

73 better. The comparative deals with two states — how the clock runs before Edgar gets his hands on it and how it runs after.

74 best. To single out the top or bottom rank from a group of more than two, go for superlative form.

75 worse. The sentence compares Edgar’s health at two points (immediately after eating the oil spill and a few hours after that culinary adventure). Comparative form works for two elements.

76 worst. The very large group of poisons has two extremes, and Time-Ola is one of them, so superlative form is best.

77 best. The group of watch oils also has two extremes, and Time-Ola is one of them, so once again you need superlative.

Here are the answers to the “Overachievers” extra practice:

1 Surprisingly. The adverb surprisingly is what you need attached to the description comfortable, an adjective.

2 Correct. The adjective comfortable answers what kind of suits? Suits is a noun.

3 Correct. Less expensive is a negative comparison, which is always formed with two words. Less is better than least, the superlative form, because you’re comparing two things — how expensive these suits were before with how expensive they are now.

4 Easy-to-clean. Easily is an adverb, but the three-word description is attached to a noun, polyester. Easy is an adjective and is the word you want here. Are you wondering why this phrase is hyphenated? Check Chapter 12 for more information.

5 really. The adjective fashionable is intensified by the adverb really. Real, an adjective, is out of place here. By the way, if it were an adjective describing colors, real would be separated from the next adjective by a comma. For more information on commas, turn to Chapter 11.

6 Correct. Office can be a noun, but here it functions as an adjective, describing the noun grind.

7 extremely. How bright? Extremely bright. Intensifiers are adverbs.

8 Correct. The adjective trendy describes the noun club.

9 more beautiful. Beautiful is a long word. To form a correct comparison, use more, most, less, or least. In this sentence, more is better than most because two things are being compared: this outfit with the group of clothes you’ve previously worn.

10 more fun. Fun is a short word, but its comparative form is more fun or less fun.

11 Correct. Sleek, an adjective, describes the noun jacket.

12 the. Elegance is defined in a specific way in this sentence. It’s deep eggplant. Because you’re being specific, the is the best article here.

13 astonishing. Astonishing is an adjective attached to the noun elegance.

14 deep. To refer to the noun eggplant, which is a color here and not a vegetable, use the adjective deep.

15 Gentle. Gentle is an adjective, just what you need to describe the noun curves.

16 a. Before a word beginning with a consonant, such as r, place a.

17 really. Natural is an adjective, which you intensify with the adverb really.

18 silky. Lining is a noun, so you describe it with the adjective silky.

19 delightfully. To intensify the adjective loud, use the adverb delightfully.

20 Correct. This adjective describes the noun shades.

21 Correct. Many people work in an office, so the superlative form of comparison is what you want here. Because capable is a long word, the two-word comparison is needed.

22 Soft. You’re describing how the clothing feels, not how it was made. The adjective soft describes the noun pants. (The comma is a clue that you have two adjectives; turn to Chapter 11 for more information.)

23 the. The text makes it clear that you’re talking about the “sleek jacket” that has already been identified. To refer to that specific jacket, use the.

24 Correct. The adverb above works perfectly here to explain where the jacket is described.

25 vivid. You need an adjective, vivid, to describe the noun accessories.

Sometimes when you ask the adjective or adverb questions, the answer is a group of words. Don’t panic. You’ve probably found a prepositional phrase (see

Sometimes when you ask the adjective or adverb questions, the answer is a group of words. Don’t panic. You’ve probably found a prepositional phrase (see  Most adverbs end in -ly, but some adverbs vary, and adjectives can end with any letter in the alphabet, except maybe q. If you’re not sure which form is an adjective and which is an adverb, check the dictionary. Most definitions include both forms with handy labels telling you what’s what.

Most adverbs end in -ly, but some adverbs vary, and adjectives can end with any letter in the alphabet, except maybe q. If you’re not sure which form is an adjective and which is an adverb, check the dictionary. Most definitions include both forms with handy labels telling you what’s what.