Chapter 15

Charities

Chapter Contents

First Requirement of Charitable Status: There Must Be a Charitable Purpose

Second Requirement of Charitable Status: There Must Be Public Benefit

Third Requirement of Charitable Status: The Objects Must Be Exclusively Charitable

This chapter considers an application of the law of trusts to a concept that has existed from at least the seventeenth century: charity. It is suggested that most people would believe that charities exist with the broadest purpose of doing good in society. This chapter looks at how charities exist in law and illustrates how charities in law are not limited to the everyday examples (such as the RSPCA or Cancer Research UK) with which you may be familiar.

As You Read

Look out for the following key issues:

![]() how charities are administered and the advantages of having charitable status; and

how charities are administered and the advantages of having charitable status; and

![]() the three essential requirements that an organisation must possess to be defined as a charity under the Charities Act 2011. These are that the organisation must:

the three essential requirements that an organisation must possess to be defined as a charity under the Charities Act 2011. These are that the organisation must:

– have a charitable purpose (as defined under s 3(1) of the Act);

– be shown to benefit the public (as required under s 2(1)(b) of the Act); and

– be wholly and exclusively charitable.

Background

The first example of Parliament recognising what was, at the time, a charity, was set out in the Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses Act 1601 (sometimes colloquially known as the ‘Statute of Elizabeth’). This Preamble contained a list of what was, in Elizabethan times, seen to be charitable although, as Lord Macnaghten pointed out in The Commissioners for Special Purposes of the Income Tax v Pemsel,1 the courts had recognised that charities could exist long before the 1601 Act. The courts used the Preamble to recognise those organisations or gifts as having charitable status if they either fell within the list contained in it, or fell within the ‘spirit and intendment’ of that list.

Making connections

You should remember from your studies of the English legal system that it is, of course, not usual for the Preamble of an Act to have such a prominent role as the one to the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 enjoyed. The Preamble to an Act usually has no legal status and is usually an explanation of why the Act was enacted. But not only did the courts define whether an organisation or gift had charitable status by considering whether it fell within the definition in the Preamble, they also asked whether organisations or gifts of a similar nature to those set out in the Preamble could have charitable status.

Perhaps even more surprising is that the Preamble has been repealed (by the Charities Act 1960) and yet it is still referred to in the most modern of legislation: see s 1(3) of the Charities Act 2006.

Nowadays whether something enjoys charitable status is governed by the requirements of the Charities Act 2011. Section 2(1) sets out that, to enjoy charitable status, two requirements must be satisfied: (i) there must be a charitable purpose permitted by law; and (ii) there must be an element of benefit to the public in the work the organisation will undertake.

Charity Administration

Charities are an important part of today’s society. There are, as of 2012, over 161,000 charities registered with the Charity Commission.2 As will be shown, not all charities have to be regis-tered with the Charity Commission, so the total number of charities will be even higher.

The advantages of enjoying charitable status

There are several advantages of having charitable status, the most important being (i) taxation and (ii) legal.

Taxation

Generally, any income received by individuals or companies in England and Wales is subject to taxation. The rates of tax may change in the annual Budget delivered by the Chancellor of the Exchequer. For example, if you are in paid employment and earn over £8,1053 you will have to pay tax on that income. Similarly, if you own shares and the company declares a dividend, that will result in income being paid to you, which again will be taxed.

Charities enjoy substantial tax relief on income they receive, provided that income is used for charitable purposes. For example, if a charity holds land which it rents out (such as, for instance, the National Trust), no tax will be payable on the income, provided it is only used for charitable purposes. Likewise, a charity’s income from money it may hold in a bank account is not subject to tax. Charities may also receive dividends from any company shares they own free from income tax.

Have you ever been asked to ‘gift aid’ a donation to a charity? Gift aid enables a charity to reclaim basic rate tax that a taxpayer making the donation will have paid on their income.

For example, suppose Scott goes to a National Trust property and there is a ? entrance charge. He may be asked if he wishes to take advantage of the ‘gift aid’ scheme. It costs Scott no additional money. The entrance fee is then treated as a donation upon which the National Trust can reclaim the basic rate of tax (currently 20 per cent) that Scott will have been charged when he earned his salary. That means that the National Trust may reclaim a further 20 per cent (£1.25) from HM Revenue & Customs.

Charities enjoy other taxation exemptions and reliefs too. For example, the charity will not be charged capital gains tax (CGT) on any gains it makes, provided that the monetary gain is used for charitable purposes. When buying land, the charity will be able to purchase it free of stamp duty land tax (SDLT). If it has premises, the charity will pay lower business rates than a non-charitable organisation.

All of these reliefs and exemptions from taxation make charitable status attractive for an organisation or gift.

Legal advantages

Charities may exist under one of several different legal structures. For example, a charity may take the form of:

[a] A company limited by guarantee. This is where a limited company is formed to manage the charity and directors are appointed to run it. The company’s liability is limited by a guarantee provided by those individuals establishing it. No shares in the company are issued.

[b] An unincorporated association. This is a club or society where its members hold property on the basis of a contract between themselves (see Chapter 6 for further discussion).

[c] An express trust.

It is the concept of establishing a charity by an express trust that is of the most interest here and, generally, the discussion in this chapter will now proceed as though an express trust has been chosen as the medium to establish a charity.

As you know, express trusts have to be both declared and constituted.4 Charities are, however, allowed to deviate from several of the usual requirements needed to declare an express trust:

[a] To a certain extent, charitable trusts can deviate from the usual rules of certainty required when a trust is established.5 Usually there must be certainty of intention, subject matter and object when an express trust is established. Certainty of intention and certainty of object do not need to be complied with as rigidly in a charitable trust, because defined individuals are not intended to benefit from the trust: the trust is instead being established to benefit a purpose. Instead of specifying precisely who will benefit from the charitable trust, it is possible to state that the charity will exist for one or more of the general charitable purposes set out in s 3 of the Charities Act 2011.

Having said that, however, there are limits as to how far the rules of certainty can be disapplied, as shown in Chichester Diocesan Fund & Board of Finance (Incorporated) v Simpson.6

In his will, Caleb Diplock left his residuary estate (approximately £250,000) to ‘such charitable institution or institutions or any other charitable or benevolent object or objects in England’ as his executors should choose. The executors asked the court whether such a gift was valid as a charitable one or whether it was void for uncertainty. By a bare majority, the House of Lords held that it was void for uncertainty.

The key focus for the House of Lords was on the phrase ‘charitable or benevolent’. These words were seen by the majority to be disjunctive (not connected to each other). If necessary, the court could administer a trust for a charitable purpose, as the court could decide what a charitable purpose is in law. But the court could not administer a trust for a benevolent purpose. A benevolent purpose might be wider or narrower than a charitable purpose: it was impossible to say. By the use of the key word ‘or’ in his will, Mr Diplock had not demonstrated sufficient intention to benefit only a charitable object.

A different decision had been reached by the High Court in Re Best.7 The decision illus-trates how vital the use of the word ‘and’ can be instead of ‘or’. Thomas Best left his residuary estate to the Lord Mayor of Birmingham to be used for ‘charitable and benevolent’ purposes in the city of Birmingham and the wider counties in the Midlands. Farwell J held that the gift was a valid charitable gift. Mr Best had clearly stated an intention that his estate should only go to charities and he had simply limited those charities who could benefit by stating that they also had to have a benevolent purpose.

What is clear, therefore, is that certainty of intention must still be present in a charitable trust in that the settlor must show a clear intention to benefit a charity. The precise objects — as to which particular type of charity may benefit — may be dispensed with, as long as the court can construe an intention to benefit a charitable purpose as now defined in the Charities Act 2011;

[b] Generally speaking, English law discourages the use of purpose trusts.8 Yet charities are, by their very nature, examples of trusts established for a purpose as opposed to benefiting an individual. English law not only permits this, but actively encourages it, through the taxation reliefs and exemptions discussed. The rather cynical reason for this is that if the law stuck rigidly to its beliefs in that all trusts must benefit an individual, an increased burden would result on the government to take the place of providing all of the good works currently undertaken by charities which would result in an increased taxation burden to society in general;

[c] The beneficiary principle9 need not be met. Beneficiaries generally have a dual role: they not only enjoy the trust property but they also act as ‘enforcers’ of the trust against the trustee. They ensure the trustee administers the trust for their benefit and not his own. The beneficiary principle is, however, dispensed with in the case of a charitable trust. Bespoke enforcers of each charitable trust are not required because it is the Charity Commission’s role to take enforcement action10 against the charity trustees if they breach the terms of the trust; and

[d] Charitable trusts need not comply with the Rules against Perpetuity.11 Section 4 of the Perpetuity and Accumulations Act 2009 provides that the only perpetuity period permitted for trusts is a fixed period of 125 years. Broadly, this means that the property of the trust must vest in the beneficiaries within that time to prevent the trust being void. Charities do not suffer from such a requirement and may exist in perpetuity. For example, Thomas Barnardo started his work in 1867 and his charity still exists today.

The Charity Commission

The Charity Commission was formed by the Charities Act 2006.12 Prior to that Act, the Charity Commissioners13 had exercised the same roles as the Commission.

The Charity Commission has two main roles.14 The first is to keep a list of ‘registered’ charities. In doing this, it must decide whether charitable status can be granted to the organ-isation. The Charity Commission must base its decision on the definition of ‘charity’ in s 1 of the Charities Act 2011 and case law both prior to, and since, the enactment of that Act. The Charity Commission’s second function is to police charities. This means, to give just two examples, that it is responsible for ensuring that (a) a charity makes an annual return demonstrating its public benefit, and (b) that the trustees of the charity are administering the charity’s property correctly towards the aims of the charity and for the benefit of the public.

The Charity Commission’s two main functions are summarised in Figure 15.1.

Certain charities cannot have ‘registered’ status with the Charity Commission.15 These include those charities:

[a] with an annual income ofless than £5,000. Many local charities will fall into this category;

[b] known as ‘excepted’ charities providing that they have an annual income of £100,000 or less. Excepted charities are those which remain regulated by the Charity Commission but may not be registered unless their annual income exceeds £100,000. Excepted char-ities are so called because they are excepted from registration either by an order made by the Charity Commission or specific legislation. Such charities would, for instance, include Scout and Girl Guide groups; and

[c] known as ‘exempt’ charities. Exempt charities fall into two groups: those with a principal regulator and those without. Those with a principal regulator are regulated not by the Commission but by that regulator,16 which has usually been appointed by Parliament. Housing Associations often fall into this category.17 The regulator also ensures that the charity complies with its obligations under the Charities Act 2011 so there is no need for the Charity Commission to provide a second layer of regulation. Some exempt charities have no principal regulator,18 but these charities’ status is now being changed to ‘excepted’. This means that the Charity Commission will regulate all of this group but only those with an annual income exceeding £100,000 will have to register with the Charity Commission.

The Charity Commission will, therefore, regulate the vast majority of charities. In turn, the vast majority of charities will be registered.

On a day-to-day basis, however, it is the charity’s trustees who manage the trust property and administer the trust, just as in the case of any express trust. Under s 34(3)(a) of the Trustee Act 1925, there is no limit to the number of trustees of a charitable trust where the trust property includes land, unlike that of a non-charitable trust where the maximum number is limited to four.19

Definition of a Charity

Key Learning Point

There are three main requirements to be a charity in law:

(a) the trust must be for a charitable purpose;

(b) the trust must be for the public benefit, either as a whole or a sufficiently large section of it such that it can be seen to be benefiting the public; and

(c) the purposes of the trust must be wholly and exclusively charitable.

‘Charity’ in law is not defined in any popular sense. As Lord Simonds said in relation to its derived term ‘charitable’ in Chichester Diocesan Fund & Board of Finance (Incorporated) v Simpson,20 ‘it is a term of art with a technical meaning’. That ‘technical meaning’ is today to be found in s 1 of the Charities Act 2011, which provides that a charity:

[a] is established for charitable purposes only, and

[b] falls to be subject to the control of the High Court in the exercise of itsjurisdiction with respect to charities.

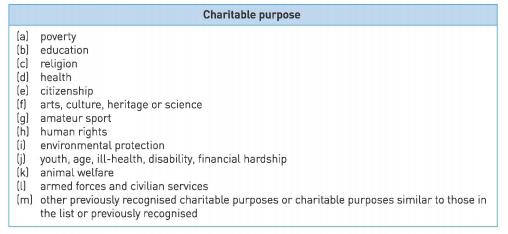

Section 2 states that a charitable purpose must be one falling within s 3(1) and be one which benefits the public. Section 3(1) sets out a list of 13 charitable purposes which are illustrated in Figure 15.2.

Section 2(1) of the Charities Act 2011 sets out categorically that not only must there be a charitable purpose, but that any organisation wishing to claim charitable status must also be for the benefit of the public. The enactment of this requirement and the earlier Charities Act 2006 was the first time that this public benefit requirement was enshrined in legislation.

The Charities Act 2006 was not the first time that ‘charitable purpose’ was defined in law. The first recognition of what a charitable purpose could be was in the Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601, but it was effectively the opinion of Lord Macnaghten in The Commissioners for Special Purposes of the Income Tax v Pemsel21 which provided a more modern definition of the phrase by summarising those charitable purposes under four main heads; this definition lasted until the Charities Act 2006.

The facts of the case concerned land left on trust in 1813 for the Moravian Church. One-half of the profits made from the land were instructed by the settlor to be used to maintain and support missionary work in other nations in order to convert people to Christianity. Relief from income tax for profits made from land owned for charitable purposes had been enacted under the Income Tax Act 1842.

Until 1886, the Inland Revenue had duly refunded income tax that the Church had paid on the profits it made from the land. In that year, however, the Revenue refused, claiming that the lands were not held on trust for ‘charitable purposes’. The Revenue’s view was that ‘charitable purposes’ revolved around how ‘charity’ would be defined in popular meaning which, in turn, meant solely the relief of poverty. That was the only sense in which most people would define ‘charity’. There was, the Revenue argued, no charitable purpose here as it was not necessarily the case that the money made from the land was to be used to relieve poverty.

By a majority, the House of Lords held that the phrase ‘charitable purpose’ was not restricted solely to the relief of poverty; instead the phrase had to be given its much wider legal meaning. The land was used for charitable purposes, so the relief from income tax should be reinstated by the Inland Revenue.

The case is known for the decision of Lord Macnaghten. He explained that the Court of Chancery:

has always regarded with peculiar favour those trusts of a public nature which, according to the doctrine of the Court derived from the piety of early times, are considered to be charitable.22

Later, the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 was enacted to deal with abuses of charities. In order to do so, the Preamble to that Act had contained a definition of charitable purpose. This definition was ‘so varied and comprehensive that it became the practice of the court to refer to it as a sort of index or chart’.23 Successive courts viewed the list as a not exhaustive definition of what a charitable purpose could be; according to Lord Cranworth LC in University of London v Yarrow,>24 those charitable purposes in the Preamble were ‘not to be taken as the only objects of charity but are given as instances’. In turn, that meant that the courts saw purposes which were similar to those listed in the Preamble as deserving of charitable status. As Chitty J put it in Re Foveaux:25

Institutions whose objects are analogous to those mentioned in the statute are admitted to be charities; and, again, institutions which are analogous to those already admitted by reported decisions are held to be charities.

This approach effectively continues to this day as s 3(1)(m)(ii) of the Charities Act 2011 gives the court the ability to recognise as charitable anything which is either ‘analogous to, or within the spirit of’ any of the main charitable purposes listed in s 3(1) of the Act.

Think about the phrase ‘analogous to, or within the spirit of’ any of the main charitable

purposes listed in s 3(1) of the Charities Act 2011.

Suppose a celebrity chef opens a cookery school. He charges a fee for each participant to attend and learn from him. Could he claim that it is analogous to, or within the spirit of, the advancement of education and so claim charitable status for this activity?

Could the grower of a plantation of genetically modified crops claim that it is analagous to, or within the spirit of, advancing science?

It is questions such as these that the courts have had to wrestle with over centuries to decide whether to grant charitable status. These conundrums are set to continue due to the need to retain flexibility in the courts’ approach of being able to grant charitable status to purposes similar to those which already enjoy such status.

Lord Macnaghten set out his definition of the charity:

‘Charity’ in its legal sense comprises four principal divisions: trusts for the relief of poverty; trusts for the advancement of education; trusts for the advancement of religion; and trusts for other purposes beneficial to the community, not falling under any of the preceding heads.26

This definition was described by Wilberforce J in Re Hopkins’ Will Trusts as ‘the accepted classifica-tion into four groups of the miscellany found in the Statute of Elizabeth’.27

Lord Macnaghten’s summary of charity lasted until the Charities Act 2006 was enacted to consolidate the earlier Charities Act 1993 and other Acts relating to charity law. However, the first three heads of charity under s 3(1) of the Charities Act 2011 are practically the same as those enunciated by Lord Macnaghten. His final head has, arguably, been split up by the Act into the remaining ten heads listed in that subsection which perhaps give the definition of charity a more contemporary flavour. Those modern charitable purposes must now be examined.

The statutory definitions of ‘charity’ and ‘charitable purpose’ enacted for the first time in the 2006 Act were probably overdue. The Preamble was, by that stage, over 400 years old and its acknowledgement of charitable purposes reflected those prevalent in the time of Elizabeth I. The courts, by recognising further purposes as charitable by whether that new purpose was analogous to those listed in the Preamble, had created case law which was, at times, inconsistent. The new statutory definition of charity, including modern-day charitable purposes, was at least an attempt to bring charity law up-to-date and into the twenty-first century.

First Requirement of Charitable Status: There Must Be a Charitable Purpose

Each charitable purpose will be examined in the same order as it appears in s 3(1) of the Charities Act 2011.

The prevention or relief of poverty

The Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 referred to the relief of the aged, impotent (disabled) or poor.

In his opinion in The Commissioners for Special Purposes of the Income Tax v Pemsel, Lord Macnaghten showed that relieving poverty was essentially the only meaning the Victorians gave to charity. Lord Macnaghten argued persuasively that a charitable purpose could have other meanings, which he then defined.

Until the 2006 Act, this charitable head was concerned merely with relieving poverty. This head suggested any charity would have to demonstrate that it reacted to poverty by seeking to ameliorate it. The 2006 Act retained this definition, but also added to it by providing that charities under this head could, for the avoidance of doubt, act proactively. This charitable purpose would also include preventing poverty and not just relieving it. The 2011 Act retains this definition.

Do you think that the words of the 2006 Act changed this charitable purpose substantively? Is there, in practical terms, a great deal of difference between the prevention or relief of poverty? It is surely unlikely that the Charity Commissioners before the 2006 Act was enacted would have refused to register a charity which sought merely to prevent, as opposed to relieve, poverty.

In Attorney-General v Charity Commission for England and Wales,28 Warren J thought that there could, in theory, be a difference between preventing and relieving poverty. He gave the example of a charity providing money management advice as being one that could exist solely to prevent poverty. Yet, practically, in most cases charities will have objects that are for both the prevention and relief of poverty.

If a charity’s purpose must be the ‘prevention or relief’ of poverty, what is meant by ‘poverty’?

‘Poverty’ was defined by Evershed MR in Re Coulthurst.29 John Coulthurst declared a discretionary trust of £20,000 in his will and directed that his trustee should pay an allowance to any widows and orphaned children of either officers or ex-officers of Coutts & Co as the trustees thought were ‘most deserving of assistance’, according to their financial circumstances.

The Court of Appeal held that the trust was charitable, as it existed to relieve poverty. It did not matter that the trust did not precisely spell out that its objective was to relieve poverty. The court would look at the purpose of the trust as a whole and, if its aim was to relieve poverty, that would be sufficient to ensure that it could attain charitable status under this head. The decision may thus be seen as an application of the maxim that equity looks to the substance of the testator’s aim and not to the precise form of the words he chose to use.

Evershed MR went on to define ‘poverty’:

poverty does not mean destitution; it is a word of wide and somewhat indefinite import; it may not unfairly be paraphrased for present purposes as meaning persons who have to ‘go short’ in the ordinary acceptation of that term, due regard being had to their status in life, and so forth.30

The very nature of this trust suggested that its aim was to relieve poverty. It only benefited widows and orphaned children who were ‘most deserving of [financial] assistance’.

The notion that poverty is a relative concept may be shown by considering the facts of Re de Carteret.31

Here, the Right Reverend Frederick de Carteret, formerly the Bishop of Jamaica, declared a trust in his will of £7,000 which was to be invested and the income generated by it to be used to pay an annuity of £40 each to widows or spinsters living in England with a preference for those widows who had young dependent children. But the trust had a condition placed on it: to receive this annual sum, the widows or spinsters had to have an annual income of between £80 and £120. This level of minimum income meant, of course, that the potential recipients of the money were perhaps not poor by the standards of the 1930s. Again, the issue was whether such a trust could be valid as a charitable trust for, if not, it would be void as infringing the rules against perpetuity.

Maugham J held the trust was charitable. He stressed that poverty did not mean absolute destitution. A trust could be held to be charitable for the relief of poverty if its aim was to relieve people of limited means who were obliged to incur expenses as part of their ‘duties as citizens’.32 He said that, effectively, the widows had to have young dependent children to receive the annuity.

Whilst this decision affirms that poverty does not mean absolute destitution, it is suggested that it is, in some ways, a strange decision for the court to reach. Maugham J effectively reinterpreted the trust. The testator had placed a preference on widows with dependent children to benefit from the gift, but there was no compulsion on the trustees to distribute the money solely to these individuals. It may well be that the testator intended that widows without dependent children or spinsters could have benefited from his generosity. These two groups would not have had to incur the type of expenses in raising their children to which Maugham J referred as justifying his decision. His only way around this was to restrict the trust set up by the testator to widows with dependent children; it must be questioned whether restricting the testator’s trust truly reflected the testator’s wishes.

Whilst these decisions illustrate that the trust does not have to mention ‘poverty’ expressly to be considered charitable under this head, trusts are not usually charitable unless they are restricted to benefiting those who are poor. Where anyone can benefit from the trust, it will probably not be held to be charitable, as Re Sanders’ Will Trusts33 illustrates.

William Sanders created a discretionary trust over one-third of his residuary estate in his will so that his trustee could provide housing for the ‘working classes and their families’ who lived in the area of Pembroke Dock, Wales.

Harman J held that the trust was not charitable. It could not fall under this charitable head because it was not restricted to those people who were poor. As he put it, ‘[a]lthough a man might be a member of the working class and poor, the first does not at all connote the second’.34 ‘Working classes’ had no connection to the concept of poverty.

The decision could be distinguished from the earlier cases of Re de Carteret and Re Coulthurst. Both of those decisions concerned widows and/or orphaned children, where poverty could, apparently, be readily inferred. Mr Sanders’ trust was simply for the ‘working classes’, which were ‘merely men working in the docks and their families’.35

The decision in Re Sanders’ Will Trusts was, however, distinguished by Megarry V-C on not dissimilar facts in Re Niyazi’s Will Trusts.36

Mehmet Niyazi was originally a Turkish Cypriot. He left his £15,000 residuary estate on trust for the construction of a ‘working mens hostel’ (sic) in Famagusta, Cyprus. The issue was whether such trust could be charitable, considering the earlier decision of Harman J in Re Sanders’ Will Trusts.

Whilst acknowledging that the case was ‘desperately near the borderline’,37 Megarry V-C held that the trust was charitable. ‘Working men’ impliedly contained within its definition a reference to lower incomes. The use of the word ‘hostel’ was key to distinguishing the decision from Re Sanders’ Will Trusts. A hostel connoted a form of basic accommodation that only those who were poor would use, especially when prefixed by the phrase ‘working mens’. Re Sanders’ Will Trusts referred to ‘dwellings’ where those who were better off financially could live; the better off would be unlikely to benefit from the hostel in this trust.

Megarry V-C thought that he should take into account the comparatively small amount of money left by the testator for the project. Such a sum was unlikely to build the hostel by itself or, if it did, it would be a very modest one. In the latter case, only the poor would wish to live in it. Second, he thought that where a trust was to benefit a particular area, he should take the conditions in that area into account. He thought that:

a trust to erect a hostel in a slum or in an area of acute housing need may have to be construed differently from a trust to erect a hostel in an area of housing affluence or plenty. Where there is a grave housing shortage, it is plain that the poor are likely to suffer more than the prosperous …38

Re Sanders’ Will Trusts and Re Niyazis Will Trusts seem to give different decisions on what is meant by ‘working’ classes. Do you think the decisions can be reconciled? If so, how?

Charitable trusts for the relief of poverty used not to be required to show that they bene-fited either the public as a whole or a section of it.39 This was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Re Scarisbrick.40 Neither is it a requirement that a charitable trust be perpetual in nature, even though the majority of them are.

Dame Bertha Scarisbrick left the remainder interest in half of her residuary estate (some £6,000) to be paid to her relatives who were in ‘needy circumstances’. The issue for the Court of Appeal was whether this could be construed as for the relief of poverty and thus be charitable. The difficulty with this phraseology was that it did not carry with it any objective standard of poverty and it did not limit the trustees to relieving the poverty of the relatives.

Evershed MR held that ‘needy circumstances’ could mean poverty. He pointed out that poverty was not an ‘absolute standard’41 and the recipients falling into such category had to be chosen. Those choosing had to do so honestly and the power of choice was a fiduciary discre-tion, so it had to be exercised in good faith.

Charitable status could be given even though it was the relatives of the testatrix whose poverty was being relieved. As will be discussed,42 public benefit must generally be demon-strated by a charity. A trust in favour of poor relations was an exception to this principle. Additionally, there was no requirement that the trust had to be perpetual in nature. Charitable trusts often were but if the trust fund was exhausted by making donations to those relatives in need, that did not mean to say that the trust was not charitable.

The issue of what is meant by relieving poverty needs to be addressed. Relieving poverty will, of course, often be undertaken by handing out monetary gifts, as demonstrated in a number of cases considered so far. Yet this is not the only way in which poverty can be relieved, as shown in Joseph Rowntree Memorial Trust Housing Association Ltd v Attorney-General.43

The claimant desired to build small flats or bungalows which it would then lease out to elderly people on a long lease in return for the person making a capital payment. Each resident would pay 70 per cent of the cost of the property; the remaining amount would be paid by a housing association grant. The properties were effectively what is known as ‘sheltered accommodation’ where a warden is also present to liaise with the elderly residents as and when required.

The Charity Commissioners argued that such a scheme was not charitable. They said that any benefits were provided by contract with the owners of the dwellings, not by way of outright gift, which was needed to relieve poverty and which gift could not be withdrawn, even if the people ceased to meet the qualifying criteria. Second, the scheme benefited private individuals as opposed to a class. Third, they also said that such a scheme could not be charitable, as it would result in the people making a profit on their dwellings as the amount of their investment rose with general property prices.

Peter Gibson J held that the scheme was charitable.

It was not necessary under the Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses that beneficiaries should have to prove that they were aged, impotent and poor. Those words had to be read disjunctively. It was enough that beneficiaries fell into one of those three categories. He defined ‘relief’ as meaning:

the persons in question have a need attributable to their condition as aged, impotent or poor persons which requires alleviating and which those persons could not alleviate, or would find difficulty in alleviating, themselves from their own resources.44

Peter Gibson J therefore considered that the need of the recipients had to have a causal connection to the generosity of the trust in order for their need to be relieved. On the facts, the recipients’ needs were due to their being elderly which could be relieved by the provision of housing accommodation. Such a trust could be considered charitable. The fact that the elderly people received their accommodation under a contract as opposed to pure gift was irrelevant to whether the trust could be charitable.

The scheme was for the benefit of a class of people: it was for the benefit of the class of people who were aged who had particular accommodation needs. Nor did it matter that the residents might receive a profit should the value of their properties increase: this was an inci-dental benefit to the charitable purpose as opposed to the main objective of the scheme. As such it was of no consequence. In addition, it was not as though the residents profited at the scheme’s expense.

Relief of poverty does not, therefore, entail simply handing out money to recipients. It can entail providing any relief to a condition caused by poverty.

The advancement of education

The Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 referred to charitable uses at the time being ‘Schools of Learning, Free Schools and Scholars in Universities’ as well as for the ‘Education and Preferment of Orphans’.

These original purposes continue to be charitable today. Most universities have charitable status as do some private schools.

The issue of whether independent schools should have charitable status and therefore enjoy tax reliefs and exemptions has long troubled politicians.

Guidance given by the Charity Commission in 2008 provided that to continue to receive charitable status, independent schools had to demonstrate that they benefited the public. Such benefit could, for example, mean that they formed partnerships with state schools to share learning resources with them, or perhaps opened their sporting facilities to the local community at weekends.

A recent decision45 of the Upper Tribunal has, however, cast doubt on whether the Charity Commission can force independent schools to demonstrate such a level of public benefit. The Charity Commission is currently rewriting its guidelines as to what level of public benefit private schools must show to enjoy charitable status.

To be seen to be charitable under this head, the key feature seems to be that the organisation must demonstrate that it is involved in the development of knowledge. This is why universities and schools may enjoy charitable status, as well as institutions such as zoos and museums46 and even the Boy Scouts.47 All are involved with the generation and dissipation of knowledge.

Given the restrictive nature of the list of charitable purposes in the Preamble, a number of previous cases featured attempts by parties to try to show that their purpose fell under this particular charitable head. The usual attempt was for the party to demonstrate that there was the development of knowledge involved in their purpose and hence it could be seen to be for the advancement of education.

Games …

An example of this occurred in Re Mariette.48 Edgar Mariette left a legacy of £1,000 in his will to the Aldenham School for the construction of Eton fives courts or squash courts. The issue for the High Court was whether such a gift was charitable, or whether it was void as for infringing the rules against perpetuity.

Eve J held that he had to consider not only the gift itself, but also the recipient of the gift, which was itself a charitable institution. The object of the school was to educate boys between 10 and 19 years old. The gift to the school could be seen as advancing that charitable purpose:

No one of sense could be found to suggest that between those ages any boy can be properly educated unless at least as much attention is given to the development of his body as is given to the development of his mind.49

Providing games for the pupils was as much a part of advancing their education as undertaking classroom-based studies. It made no difference that the testator had spelt out specifically the precise purpose for which the legacy should be used.

Re Mariette was applied by the House of Lords in Inland Revenue Commissioners v McMullen.50

Here, the Football Association decided to declare a trust called ‘The Football Association Youth Trust’. The purpose of the trust was said to be the ‘furtherance of education’ in schools and universities by encouraging pupils and students to play football. The Inland Revenue disputed that such a trust could have charitable status.

The House of Lords held that the trust was charitable. Lord Hailsham LC expressly approved the decision of Eve J in Re Mariette, a decision which he found ‘stimulating and instructive’.51 Even though the facts in Re Mariette concerned a gift left to a particular institution, the decision could be applied in a wider context as on the present facts where money was being left to schools and universities in general. Lord Hailsham LC believed that education could be seen to be a balanced process of ‘instruction, training and practice’52 which should not be confined to the classroom or lecture theatre but also to playing fields.

Lord Hailsham also pointed out that ‘education’ was not a concept fixed at any particular point in time but which varied as time went on. This would mean, for example, that what was seen not to be educational 100 years ago might well be seen to be educational now.

What was important in the decision in the case was that the trust was established to benefit pupils and students at schools and universities.

A prize fund for a game which may generally be seen to be of a more educational character — chess — was held to be charitable in Re Dupree’s Deed Trusts.53 Vaisey J felt that the facts were ‘a little near the line’54 and remarked that ‘[o]ne feels, perhaps, that one is on a rather slippery slope. If chess, why not draughts?’55

Unless, however, the game is educational in itself, or there is a link to an educational establishment, a trust purely for sporting or games could not be charitable, as Re Nottage56 demonstrates.

Here, George Nottage left £2,000 to the Yacht Raching Association of Great Britain for them to hold on trust to invest the money and to use its proceeds to establish an annual competition with the prize of ‘The Nottage Cup’ for the best yacht of each season. His will stated that the purpose behind the establishment of the competition was to encourage the sport of yacht racing. The issue was whether this could be a valid bequest. If it was to avoid infringing the rules of perpetuity, it had to be charitable.

Both Kekewich J, at first instance, and all of the members of the Court of Appeal held that the gift was not charitable. As Lindley LJ put it rather succinctly, ‘[i]t is a prize for a mere game’.57

The decision in Re Nottage demonstrates that sport in itself was not charitable where there was no link to it being educational or, as was argued in the case itself, where it could not be said to be a for a purpose beneficial to the community. The decision in the case would probably be different now. Section 3(1)(g) of the Charities Act 2011 provides that a charitable purpose can be the ‘advancement of amateur sport’. This is considered in more depth below.58

Research …

Trusts for the purpose of research can be charitable under this head providing, again, that there can be shown to be some link to education as opposed to conducting research for its own sake. This appears to be the conclusion from the decisions of the High Court in Re Hopkins’ Will Trusts59 and Re Shaw.60

In Re Hopkins’ Will Trusts, Evelyn Hopkins left one-third of her residuary estate to the Francis Bacon Society Inc to be held on trust by it and used for the purpose of finding the original manuscripts of those Shakespearean plays that some people believe were written by Francis Bacon. The society itself was charitable, but the issue was whether the trust was in its favour, or whether it was void for perpetuity.

Wilberforce J held that the trust was charitable. Searching, finding and researching into the original manuscripts of the Shakespearean plays would be of great value to both history and literature.

In contrast, Harman J held that a trust to conduct research into a new alphabet was not charitable in Re Shaw.61

George Bernard Shaw established a trust of his residuary estate in his will and directed his trustees to hold the money on trust to conduct research into how practical a new, 40-letter alphabet would be. He also instructed his trustees to translate his play Androcles and the Lion into the new alphabet’s form and to use the translation to promote the new alphabet’s use.

Harman J held that the trusts were not charitable. He said that, to be charitable, a trust for the promotion of research had to be ‘combined with teaching or education’.62 There was no teaching or education involved in this trust. It was merely to enable research to be undertaken into whether a new alphabet would save time and then to promote that new alphabet, by way of propaganda, to the public. Such purposes could not be charitable. Neither could the research fall into Lord Macnaghten’s fourth head of being beneficial to the community. Advertising and promoting a new alphabet could not be seen to benefit the community, who might prefer to remain with the usual English alphabet.

In Re Hopkins’ Will Trusts, Wilberforce J considered the view of Harman J that charitable trusts for the advancement of education had to have some link with teaching or education. He did not feel that was necessarily the case. Academic research could be seen to be charitable even though the researcher was not linked either to the teaching profession or an educational estab-lishment.

Wilberforce J said that research could be charitable under this head, or if it could other-wise be seen to be for the benefit of the community. ‘Education’ had to be given a wide meaning. This meant the research could be:

of educational value to the researcher or must be so directed as to lead to something which will pass into the store of educational material, or so as to improve the sum of communicable knowledge in an area which education may cover.63

Naturally, there had to be some public benefit to this research as he held that private research, the results of which were made known only to the members of a society, would not be charitable.

Alternatively, he said that research could be charitable if it fell under Lord Macnaghten’s fourth charitable head — for the benefit of the community. In this case, ‘beneficial’ would be given a wide interpretation, to mean not just of material benefit (Wilberforce J gave the example of medical research giving a material benefit to the community as a whole) but also of intellectual or artistic benefit to the community.

These two decisions can be reconciled in that a trust for genuine research, improving knowledge with dissemination to show a public benefit, can be seen to be charitable either under this head, or for a purpose beneficial to the community (perhaps now under s 3(1)(f) of the Charities Act 2011 — a purpose which is for the advancement of the arts, culture, heritage or science). On the other hand, a trust for research conducted to promote one’s own subjective point of view, as opposed to increasing knowledge objectively, will not be seen to be charitable.

Music …

A society formed to advance choral singing in London was held to be charitable under this head in Royal Choral Society v Commissioners of Inland Revenue.64 The society argued that its objectives were charitable: to provide choral concerts in the Royal Albert Hall, London and to encourage choral singing generally.

The Court of Appeal held that the society was charitable under this head. Providing music educated the listener. Lord Greene MR said he did not accept the view that ‘education’ had to be defined as narrowly as teaching when considering ‘aesthetic education’.65 The society, he thought, had been established for educational purposes because it was of the utmost relevance that the ‘education of artistic taste is one of the most important things in the development of a civilised human being’.66 Improving artistic taste of the general public was just as educational, he thought, as lecturing or teaching. The fact that entertainment was a by-product of the society was not important — its overall objective was to educate.

The advancement of religion

At first glance, perhaps oddly, the advancement of religion never featured as a charitable use within the Preamble. It was mentioned by Lord Macnaghten as his third charitable head in Pemsel and has been enshrined in s 3(1)(c) of the Charities Act 2011.

Section 3 (2) (a) of the Charities Act 2011 provides guidance as to what is meant by ‘religion’. It states that a religion may involve believing in more than one god. It also states that a religion may involve not believing in a god at all.

Established religions such as Christianity, Judaism and Islam67 are all encompassed within the term ‘religion’ and so trusts to benefit such religions can be charitable in nature, provided public benefit is also demonstrated either by the religion or by the trust. The provision that religion may involve believing in more than one god would now specifically mean that trusts in favour of such religions as Hinduism and Shintoism could also be charitable.

The fact that ‘religion’ can now include a religion which does not involve believing in any god would suggest that the decision of the High Court inRe South Place Ethical Society68 would be decided differently today.

The trustees of the South Place Ethical Society held its property on trust, the stated objective of the society being ‘the study and dissemination of ethical principles and the cultivation of a rational religious sentiment’. The society’s members were agnostics, who held meetings on Sundays at which the public could attend. Their beliefs involved, according to Dillon J, ‘the belief in the excellence of truth, love and beauty but not belief in anything supernatural’.69 The trustees sought a declaration that their objects were charitable.

Dillon J held that the objects of the trust were not charitable under the advancement of religion head. To Dillon J, ‘two of the essential attributes of religion are faith and worship; faith in a god and worship of that god’.70 The society did not believe in a god and did not worship that god. Dillon J held, however, that the society’s objects could be seen to be charitable under Lord Macnaghten’s fourth head — that they were beneficial to the community.

Following the enactment of the Charities Act 2006, the objects of the society would undoubtedly be classed as religious. The definition in s 3(2)(a) of the 2011 Act widens out ‘religion’ considerably.

A more difficult issue remains with whether Scientology would be considered a religion.

Scientology involves a belief in the writings of an American named L Ron Hubbard. This involves the notion that everyone was placed on earth by aliens. Devotees of this faith include a number of celebrities such as Tom Cruise and John Travolta.

Traditionally, the English courts have not viewed Scientology as a religion.71 This was largely due to the view of the courts, set out by Dillon J in Re South Place Ethical Society, that reli-gion had to involve believing in a god. The cases on Scientology were all decided before the Charities Act 2011 was enacted, however, so it might be that a different conclusion would now be reached.

Support for Scientology being seen to be a religion for taxation purposes can be gained from the decision of the High Court of Australia in Church of New Faith v Commissioner of Pay-Roll Tax (Victoria).72 There the Church of New Faith followed the writings of L Ron Hubbard and its followers were Scientologists. The High Court of Australia held that the beliefs and practices of the church did fall into the definition of ‘religion’. The High Court thought that religion should not be confined to those religions which believed in a god.

Having said this, even if Scientology was held to fall within the definition of ‘religion’ set out in the Charities Act 2011, it is suggested that it is unlikely it would be held to be charitable in England and Wales. This is because the second requirement of having charitable status — that of benefiting the public — is not satisfied by Scientology. Its practices benefit its members alone and it is, perhaps, more akin to a private club or society which benefits only its members rather than the general public.

The advancement of health or the saving of lives

The Preamble contained reference only to the ‘Maintenance of Sick and Maimed Soldiers and Mariners’.

The 2011 Act contains a much wider definition, not limiting this head to those servicemen mentioned in the Preamble. Section 3(2)(b) refers to this head including ‘the prevention or relief of sickness, disease or human suffering’. It seems that a charitable purpose could be the advancement of mental, as well as physical, health. For instance, Mind would be an example of a charity for the promotion of mental health in England and Wales that could now fall under this head.

The advancement of health or the saving of lives was a new separate charitable head under the 2006 Act, but this purpose was seen as charitable under case law decided before the Act. In Re North Devon and West Somerset Relief Fund Trusts,73 a trust to help save lives was recognised as charitable by Wynn-Parry J.

On 15 August 1952, torrential rain poured down over North Devon and West Somerset, causing severe flooding. An appeal was made by the Lord Lieutenants of both Devon and Somerset for donations to be made to a fund to be used to help both the inhabitants of the counties and visitors who had been affected by the rain. One issue for the High Court was whether this trust could be held to be charitable.

Wynn-Parry J held that it was. Its objective was to provide financial assistance to those who had been affected by the floods. It was designed to help those who had suffered and its aim was to help save lives.

Whilst the Preamble spoke specifically of maintaining sick and maimed servicemen, in truth this charitable head has probably always existed but as part of the more general relief of poverty purpose. In cGovern v Attorney-General,74 Slade J accepted the analysis that poverty itself was probably merely a species of a more general charitable head which included the ‘relief of suffering and distress in all the various forms enumerated’.75 If this is right, the addition of this specific head in the 2006 Act (re-enacted in the 2011 Act) adds little to pre-existing charity law.

The advancement of citizenship or community development

The Preamble took a pragmatic approach to what might nowadays be referred to as ‘community development’. It referred to charitable purposes being the ‘Repair of Bridges, Ports, Havens, Causeways, Churches, Sea-banks and Highways’.

Section 3(2)(c)(i) states that this charitable head would continue to include physical projects by describing ‘rural or urban regeneration’ as falling within section 3(1)(e).

It is not necessary for the advancement of citizenship or community development to consist of building or repair works to community structures. Section 3(2)(c)(ii) states that this head would also include ‘the promotion of civic responsibility, volunteering, the voluntary sector or the effectiveness or efficiency of charities’.

The notion that rewarding the community could consist of something other than physical construction was shown in Re Mellody.76 There money was left on trust to provide an annual treat to schoolchildren in Turton. Eve J held that the trust could be seen to be charitable on two grounds: (i) for the advancement of education, and (ii) for the benefit of the community. The schoolchildren were a ‘large and important section’77 of the community who might be benefited by, for example, being taken out of their school and shown the countryside.

A more modern example of a trust which was to benefit the community was considered by the High Court in Re Harding.78

Sister Joseph Harding made a will in which she left all of her property to the ‘Diocese of Westminster to hold in trust for the black community of Hackney, Haringey, Islington and Tower Hamlets’. Sister Joseph made no provision of what she expected the Diocese of Westminster to do with her property so that the black community of those London areas would benefit, but it appears it was intended for that community’s general development.

Lewison J held that the trust was valid as a charitable trust. It did not matter that Sister Joseph had not set out precisely how she expected the Diocese to apply the property.

Both decisions concerned charitable trusts benefiting large sections of the community so it would appear that, to fall under this charitable head, the trust need not seek to advance the entire community.

The advancement of the arts, culture, heritage or science

Many of the decisions already considered as falling into Lord Macnaghten’s fourth charitable head as being for the benefit of the community would now most likely be held to be charitable under this particular head. Cases that have already been considered which would now fall into this category include the provision of choral music to the public in Royal Choral Society v Inland Revenue Commissioners and also research in Re Hopkins’ Will Trusts. The research into the true author of the Shakespearean plays would now be seen to be for the advancement of the arts, culture and/or heritage.

There are many organisations with charitable status that would now fall under this charitable head. These could include museums, libraries and galleries, all of which exist to promote any or all of the parts of this charitable head.

The advancement of amateur sport

It will be remembered that before the Charities Act 2006 was enacted, sport itself was not a charitable purpose.79 Sport could only be charitable if it was linked in some way to another charitable head, such as education or for the benefit of the community.

The Charities Act 2006 marked a shift in thinking that had occurred since Re Nottage. Perhaps concerned to promote exercise and physical activity, the advancement of amateur sport is now a charitable head in its own right and there is no need to show any link with any other charitable purpose.

In guidance produced in April 2003, however, the Charity Commission80 had already confirmed that playing sport in its own right with no link to education could be charitable. Its guidance was based on the fact that the playing of sport could fall into Lord Macnaghten’s fourth head, so that playing sport as part of the community could be seen to be charitable. The guidance focuses on the need for the sport to be healthy. ‘Healthy’ is defined to mean ‘those sports which, if practised with reasonable frequency, will tend to make the participant healthier, that is, fitter and less susceptible to disease’.81 In turn, ‘fitness’ could be met by the sport helping to increase ‘stamina, strength and suppleness’82 albeit that only one of those three criteria is required for a sport to be recognised as advancing fitness. Having said that, in a note at the front of the guidance, the Commission does accept that the promotion of health does not just have to be the promotion of physical health, but can also include the promotion of mental skill. The provision for chess in Re Dupree’s Deed Trusts83 might, if decided today, be seen to be charitable under this head.

The Charity Commission provided a list of some sports which it did not feel met its definition of ‘healthy’. These included angling, pool, snooker and any form of motor sport.

Dangerous sports will not generally be seen to be charitable, as the Commission’s view is that their danger outweighs any health benefits the sport may generate. If the dangers can be reduced, it may be that the Commission would recognise the sport as charitable, for it would then be focusing primarily on promoting health rather than being dangerous. It seems that risks must be reduced severely, however. The Commission gives the example84 of amateur boxing and suggests that if risks were mitigated to an ‘absolute minimum’, it would consider recognising such a club for the promotion of that sport as charitable.

The Commission’s guidelines state that they are being revised to take into account this charitable head. Although issued before the enactment of the 2006 Act, the guidelines in some ways pre-empted it. Section 3(2)(d) confirms that ‘sport’ in s 3(1)(g) means ‘sports or games which promote health by involving physical or mental skill or exertion’. The Commission’s suggestions of those sports which would not be charitable must almost certainly continue to be correct, due to the statutory requirements in the Act itself of the requirements needed for sports to be charitable.

The advancement of human rights, conflict resolution or reconciliation or the promotion of religious or racial harmony or equality and diversity

This, together with the next charitable head in s 3(1) of the 2011 Act, may arguably be seen to be the two most contemporary charitable purposes set out in the Act.

It will now be seen to be charitable to undertake any or all of these purposes set out in this paragraph, but a settlor must take care to ensure that his charitable purpose is not political in any way. A trust for a political purpose cannot be charitable. This was set out by Slade J in McGovern v Attorney-General.85

The facts concerned a trust established in 1977 by Amnesty International.

Amnesty International itself was formed in 1961 with the purpose of ensuring that every country in the world observed the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Specifically, Amnesty International was — and is — concerned about political prisoners: people who might be summarily arrested and held without trial and perhaps even executed in countries simply for holding political beliefs. Amnesty International seeks the abolition of such practices, by working for political prisoners to be released, helping their families and generally seeking to persuade public opinion throughout the world that such practices should be abolished.

Amnesty International never considered itself to be charitable, but it received advice that some of its purposes could be. It therefore decided to filter out what it considered to be its charitable purposes into a Declaration of Trust. The trust document said that the trustees were to hold money on trust for the following purposes:

[a] the relief of certain categories of’needy persons’ (e. g. political prisoners or their relatives or dependants);

[b] to try to secure the release of political prisoners;

[c] to procure the abolition of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment;

[d] to research into human rights; and

[e] to disseminate the reserach undertaken into human rights.

The Charity Commissioners’ view was that the trust was not charitable as its objects were not ‘exclusively charitable’. The only purpose likely to be charitable was (a). The remainder were not charitable as they were of a political nature.

Slade J referred to the two decisions of the House of Lords in Bowman v Secular Society Ltd86 and National Anti-Vivisection Society v Inland Revenue Commissioners.87 Both decisions had held that trusts for political purposes could not be charitable. The purposes both involved procuring a change of the law in England. Slade J explained that there were two reasons why such a trust could not be charitable: (i) there will not usually be any evidence available to the court to decide if the change in the law is for the benefit of the public or not, and (ii) even if there is evidence, it is for Parliament (and not the court) to decide if a change in the law is needed and to modify the law as required.

The same reasons could be made for a trust to procure the law being changed in a foreign country. A further reason, based on public policy, existed in the case of such a trust — such a trust might have an adverse impact on relations between the UK and that foreign country.

A trust for political purposes could not, therefore, be charitable. But Slade J did not just feel that political purposes involved procuring a change of law in this country or abroad. Political purposes could also entail trying to reverse government policy or change administra-tive decisions of governmental authorities. Political purposes could also involve furthering the interests of a political party.88

Trusts seeking to advance any of these purposes as their main objective would also not be charitable. The reasons were exactly the same: the court could not assess if these purposes were of any benefit to the public and in promoting such trusts as charitable, the court would be encroaching on the government’s role.

The main purposes of Amnesty International’s trust deed were political. Each of the objectives listed above (with the exception of (a)) sought to bring pressure to bear on governments to reverse their policy on each particular matter. As each of the purposes could not be separated from one another, the entire trust was political and not charitable.

This does not mean that any tainting of a trust with some degree of political purpose will render the trust non-charitable. The focus is on the main objective of the trust. If any of the trust’s main objectives are political in nature, the trust cannot be charitable. But if a political objective of the trust is subsidiary to an otherwise charitable main purpose, the trust can still be charitable. Similarly, a trust could still be charitable if it set about achieving its charitable purpose by campaigning for a change in the law: the campaigning would be subsidiary to achieving its charitable objective.

McGovern v Attorney-General was, of course, decided prior to the implementation of the new charitable purposes in the 2006 Act. In Hanchett-Stamford v Attorney-General,89 the issue arose as to whether, by the specific enacting of new, more diverse, charitable heads in the 2006 Act, some arguably with political overtones in them, it could be said that the Act had impliedly consented to political purposes now being deemed to be charitable.

The facts in Hanchett-Stamford concerned an application for an unincorporated association to be recognised as charitable under s 2(2)(k) of the Charities Act 2006 (now s 3(1)(k) of the Charities Act 2011) but the decision concerning political purposes is relevant to any trust or organisation claiming charitable status.

Mrs Hanchett-Stamford was the last surviving member of the Performing and Captive Animals Defence League, an unincorporated association originally formed in 1914 in order to prevent the use of animals performing in circuses or in films. The Inland Revenue’s view was that the League’s main purpose was to try to change the law in the UK, so it could not be charitable.

The league had had many members, particularly during the 1960s, but slowly membership had declined to where the claimant was the only member. She was elderly and lived in a nursing home. The league, however, still had assets worth over? million and she wanted to transfer them to another charity promoting animal welfare under the doctrine of cy-près.90 To transfer the entire amount, she needed the league to be recognised as having charitable status.

Lewison J held that the league was not charitable when it was originally established, as its main purpose was to change the law to ban performing animals. Such a purpose was political in nature.

Lewison J rejected the view that the Charities Act 2006 had changed the law to permit trusts with political objectives to be regarded as charitable. It was, he said, a ‘fundamental principle’91 that if at least one of the objectives of the trust was political, it could not be charitable. As the last surviving member of this non-charitable unincorporated association, the assets belonged to Mrs Hanchett-Stamford absolutely and not on any charitable trust.

It is, therefore, possible to establish a charitable trust with the objective of advancing any or all of the purposes listed under s 3(1)(h). Yet as neither the Charities Act 2006 nor its 2011 successor have altered the key rule that a charity’s main purpose must not be political, it is suggested that perhaps more care needs to be taken under this head than any other that that rule is not infringed.

The advancement of environmental protection or improvement

This is, again, a reflection of modern concerns to protect the environment. There are a number of well-known charitable organisations which would now be seen to fall under this head, such as Friends of the Earth.

The relief of those in need by reason of youth, age, ill-health, disability, financial hardship or other disadvantage

As discussed, in McGovern v Attorney-General,92 Slade J accepted the proposition that the ‘relief of suffering and distress’ had always formed part of the charitable head of the relief of poverty.93 There are many organisations which may fall under this specific head today (for example, youth clubs and well-known organisations such as Help the Aged). Section 3(2)(e) states that ‘relief’ under this head may include the provision of care or accommodation to those categories of person described.

It must be asked if this charitable head was specifically needed in the Act at all. Almost all of the other heads under s 3(1) either added to, or clarified, pre-existing charitable purposes. Given that purposes considered charitable before the Act was enacted will continue to be charitable94 and the comments of Slade J in McGovern v Attorney-General, it is doubtful that this head adds anything except, perhaps, for the addition of ‘other disadvantage’. It is unclear what this phrase would encompass although any charitable object would need to be analogous to the other definitions in this paragraph.

The advancement of animal welfare

The advancement of animal welfare has long been seen to be charitable. The reasoning behind this was discussed in Re Wedgwood.95

Frances Wedgwood made a will in which she appeared to leave her residuary estate to Cecil Wedgwood absolutely. Evidence arose, however, that she had actually declared a fully secret trust in which she had appointed Cecil her trustee to hold the property on trust for the benefit and protection of animals. The Court of Appeal held that there was, in fact, a secret trust. Following earlier authorities,96 it held that a trust for the benefit and protection of animals could be said to be charitable.

Swinfen Eady LJ explained that the trust would fall under Lord Macnaghten’s fourth head in Pemsel, as one being for the benefit of the community. The trust could:

stimulate humane and generous sentiments in man towards the lower animals, and by these means promote feelings of humanity and morality generally, repress brutality, and thus elevate the human race.97

In Hanchett-Stamford v Attorney-General,98 Lewison J did not think that the enactment of a bespoke charitable head, in what is now s 3(1)(k) for the advancement of animal welfare, had made any substantial change in the law.99

The promotion of the efficiency of the armed forces of the Crown, or of the efficiency of the police, fire and rescue services or ambulance services

This paragraph concerns both the military and civilian services and ‘rescue services’ would undoubtedly include particular services which are not mentioned specifically under the head, such as the coastguard. The Preamble mentioned only military services and then only the ‘Maintenance of Sick and Maimed Soldiers and Mariners’. The promotion of the efficiency of the armed forces and civilian forces was, however, recognised by subsequent decisions as being within the spirit and intendment of the Preamble.100

Quite what ‘efficiency’ means in this paragraph is open to debate. ‘Efficiency’ usually entails reducing something in terms of time or cost. So could, for example, a trust receive charitable status if it was established to produce nuclear weapons as those would, on a rather Machievellian analysis, be more efficient for the armed forces to use than conventional weapons? It would be rather surprising if this was the case. Perhaps, therefore, ‘efficiency’ in terms of the armed forces would have to be restricted to their administrative operations.

Other purposes

Paragraph (m) provides three further categories of recognised charitable purpose:

[a] any previously existing purpose declared charitable by statute or case law which does not fall within paragraphs (a)-(l);101

[b] any purpose that may reasonably be seen to be ‘analogous to, or within the spirit of’ any of the above 12 purposes;102 and

[c] any purpose that may reasonably be seen to be ‘analogous to, or within the spirit of’ any previously recognised charitable purpose.103

The overall aim of these provisions is that the law will continue to recognise as charitable any previous charitable purpose or any purpose of a similar nature to it. This means that preexisting case law deciding charitable purposes as being within the spirit and intendment of the Preamble will continue to be good and may continue to be followed.

Second Requirement of Charitable Status: There Must Be Public Benefit

Section 2(1)(b) of the Charities Act 2011 provides that the charity must benefit the public. ‘Public benefit’ carries with it the meaning that has evolved in case law decided before the Act was enacted.104

This second requirement of charitable status is just as important as the first: the charitable trust must benefit the public or a sufficiently large section of it so that it can be said that the public is benefiting. As Dillon J put it in Re South Place Ethical Society:105

One of the requirements of a charity is that there should be some element of public benefit in the sense that it must not be merely a members’ club or devoted to the self-improvement of its own members.

In Hanchett-Stanford v Attorney-General, Lewison J recognised that public benefit could be direct or indirect. Direct public benefit is where there is a clear benefit to the public by the use to which the trust property is put. Indirect public benefit exists where the public will not directly benefit from the trust property, but where it can be showed that the public will benefit simply by virtue of the trust being created. In the case of trusts against animal cruelty, for example, the public benefit is indirect: the trust property is not being used to benefit the public, but the public benefits spiritually from knowing that animals will be better treated.

The ‘personal nexus’ test: Oppenheim v Tobacco Securities Trust Co Ltd106

Mr and Mrs Phillips created a trust in 1930 under which they granted a remainder interest107 in certain property to Tobacco Securities Trust Co Ltd. The income from it was to be used to educate the children of employees, or ex-employees, of British American Tobacco Ltd, or any of its subsidiary companies. The issue was whether the trust was valid. As in so many other cases, it could only validly take effect as a charitable trust, as it would otherwise infringe the rules against perpetuity.

By a majority, the House of Lords held that the trust was not charitable because it did not benefit the public. It undoubtedly had a charitable purpose to it — to advance education — but that was not enough in itself to make the trust charitable. It also had to benefit the public.

In giving the leading speech of the majority, Lord Simonds emphasised that, to be charitable, the trust had to benefit either the community as a whole, or a section of it. ‘Section of the community’ had two parts to it, both of which had to be satisfied:

[a] that the number of possible beneficiaries could not be ‘numerically negligible’;108 and

[b] that the attribute that distinguished the section of the community from the community as a whole could not be a quality which rested on their relationship to a particular individual. In other words, there could be no personal nexus — or connection — which linked all of those in the section of the community with a particular individual.

On the facts, the number of possible children who could benefit from the trust was not numerically negligible. There were over 110,000 current employees of the companies mentioned in the trust deed so the number of their children (together with the children of the ex-employees) who could benefit from the trust must have been far higher. But the trust fell down on Lord Simonds’ second requirement. Those benefiting from the trust could only benefit because their parents worked at one of a few companies. All of the beneficiaries had to have that connection between them to be eligible to benefit from the trust. As such, they could not constitute either the community itself (where everyone would have to benefit) or a section of it.

Dissenting, Lord Macdermott would have held that the trust was valid. He thought that, as the trust was for a charitable purpose and did benefit a large number of beneficiaries, there should be an assumption that the trust was charitable unless evidence was led to the contrary. He pointed out that he thought the requirement that there must be no personal nexus between the beneficiaries was illogical and would lead to different results on substantially similar facts. One of his examples was a trust set up to benefit coal miners. Such a trust could be valid if the miners had no connection to one another. Yet when the coal mines were nationalised after World War II, the miners would have had a connection to each other as they were then all employed by the National Coal Board. It was odd that a trust could be valid prior to, but not after, the nationalisation of the coal industry.

Despite the (valid) doubts expressed by Lord Macdermott, the views of the majority do, of course, represent the law and the majority decision was applied by the Court of Appeal in Inland Revenue Commissioners v Educational Grants Association Ltd.109 What was interesting about the latter case was that not all of the beneficiaries shared the same connection.

John Ryan was a director of Metal Box Co Ltd. He was interested in education and helping out individuals who had difficulty in educating their children at private schools, colleges or universities, if they did not receive a grant from their local authority. He persuaded his company to set up the Educational Grants Association Ltd which would pay scholarships to such students. Metal Box Co Ltd would fund the Association. This money was held on trust by the Association for the benefit of the children. The aim of the Association was to provide grants primarily for the children of the employees of Metal Box Co Ltd. The Association claimed it administered a charitable trust; the Inland Revenue argued to the contrary.