14. Advice for Nonprofits, Healthcare, Education, and Political Campaigns

This chapter synthesizes many of the earlier concepts and talks about how we can apply them specifically to nonbusiness settings. Instead of repeating what we have already covered in previous chapters, we focus on real case studies and expert perspectives on how the social Web has been used in education, healthcare, nonprofit, and political campaigns. In these situations—in which the stakes are not money, but instead social return, and people are even more swayed by each other’s opinions—Facebook and Twitter are potentially more important channels for influencing and organizing.

We focus less on LinkedIn in this chapter because these public-sector initiatives most closely resemble business-to-consumer (B2C) marketing, although some situations (such as executive headhunting) are certainly similar to the business-to-business (B2B) instances, in which our earlier discussions on LinkedIn would apply.

Nonprofits

Nonprofit organizations can use Facebook and Twitter to manage different stakeholder groups, such as to mobilize donors and volunteers. As with any “product” that you are trying to sell, a combination of Twitter, Facebook Pages, ads, and events can be effective in seeding interest, engaging audiences, and facilitating word-of-mouth.

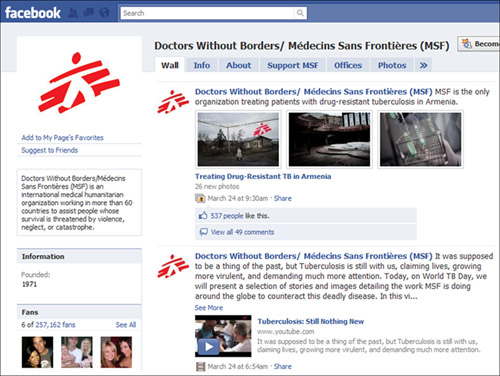

First, create a Facebook Page that represents your cause. Include photos and video. Tell a story that will cause people to form an emotional connection and feel a sense of urgency to help. With so many worthwhile causes competing for the same pool of charity dollars, even the most results-oriented donors end up contributing to the causes that resonate with their personal morals and emotions. Create a memorable and compelling experience for these individuals so that they can grasp the full impact of helping your organization and your clients and rise to the occasion, as Doctors Without Borders has done with its Facebook Page (shown in Figure 14.1).

Figure 14.1

Doctors Without Borders has amassed more than 250,000 followers on Facebook through up-to-the-minute news, photos, and video of its healthcare initiatives around the world.

Reprinted by permission

To seed interest, you can explore using Facebook ads targeted at your ideal audience profile. If you are an education nonprofit, target people who are passionate about education. If your nonprofit is dedicated to animal rescue, target people who love dogs and cats. You can also target by stage of life—for example, college students might not have much disposable income to make donations, but they could potentially devote significant amounts of time to volunteering.

The team at Camp Amelia (now SearchLit.org), a nonprofit that I helped found in 2003 (I now serve on the board), has run Facebook ads for the last few years looking for donors and volunteers. We find a nine times or better response rate when we target ads at individuals who are college graduates and live within a 10-mile radius of the low-income neighborhoods we serve with our after-school and summer programs for children.

When people show interest and “like” your Facebook Page, keep them engaged with a stream of updates from the field. Don’t just tell them—show them—how their dollars are making a difference. In the nonprofit world, people donate because they believe in the cause and think it’s the right thing to do. Help them feel more emotionally connected to the cause, and you will get repeat donors who also tell their friends to get involved.

As the 2008 Barack Obama presidential campaign taught us, people are wary of being asked for money outright. They are open to a nonmonetary call to action first, such as signing a petition or volunteering, especially if it includes a social element. When you get people involved with taking action, not only are they more likely to donate, but they will also rally their friends around the cause because they feel more invested. Facebook Events are a good way to bridge your offline and online efforts with events, fundraisers, and volunteer meetings, and to encourage people to invite friends.

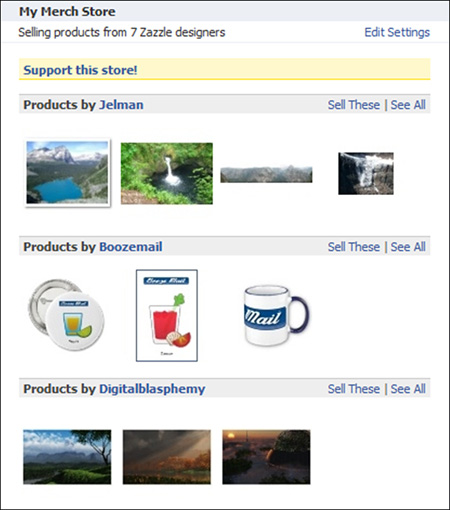

When you have set up a Facebook Page, the most popular applications for nonprofits on Facebook are My Merch Store, CafePress Listings, and Causes. Both My Merch Store (powered by Zazzle) and CafePress Listings let you and your community create and sell customized T-shirts, cards, posters, mugs, hats, and so on to promote your cause (see Figure 14.2). Especially if you have great designs that people will be proud to wear and use, these product stores can be a great way to generate revenue while building your organization’s brand and buzz.

Figure 14.2

My Merch Store lets you create, display, and sell custom products promoting your nonprofit on your Facebook Page. You can add the application at http://apps.facebook.com/merchstore.

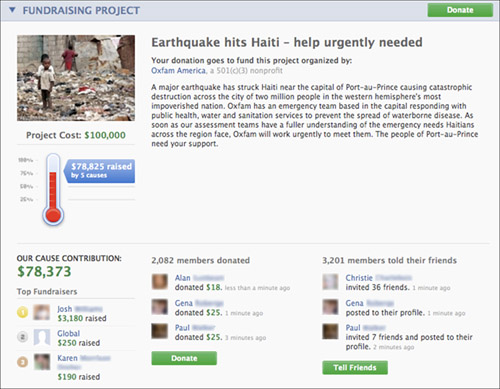

Causes enables Facebook users to create a cause about something they feel passionately about. Nearly 25 million people have installed Causes, which helps them set goals and tasks, spread awareness, facilitate dialogue, sign petitions, recruit friends, and raise money on behalf of any U. S. -registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit or Canadian registered charity. The application tracks and recognizes individuals who create causes, recruit others, and successfully take action for the cause (shown in Figure 14.3).

Figure 14.3

Causes is a popular application on Facebook for nonprofits and political campaigns that enables individuals to rally friends toward a particular cause in one of ten areas: animals, arts and culture, education, the environment, healthcare, human services, international issues, political campaigns, public advocacy, or religion. You can add the application at http://facebook.com/causes.

The following guest expert sidebar features practical advice from Causes cofounder Joe Green and nonprofit director Matt Mahan on how nonprofits can best take advantage of Facebook.

Five Tips for How Nonprofits Can Use Facebook

Joe Green and Matt Mahan

Nonprofits use Facebook for a variety of reasons, ranging from building community and listening to supporters, to cultivating donors and advocating their cause. Although the social media terrain is new and rapidly changing, effective nonprofits use time-tested organizing strategies to be successful:

1. Be accessible—Most nonprofits use Facebook because it’s “where people are.” But to join the conversation, you must integrate Facebook into what you do. Start by using Causes and Facebook Pages, Groups, Events, and ads to achieve some of your existing goals. Communicating with your employees and core supporters through Facebook makes it easier for them to activate their friend networks on your organization’s behalf. When talking about what you do and why, craft a message that helps people personally connect with your organization, and don’t be afraid to let your brand recede to the background. Remember that people don’t join Facebook to interact with an institution, as much as they join to interact with friends, ideas, and resources.

2. Tell stories—Contextualize your message by couching it within a broader narrative about what’s happening in our world and how your organization is taking action. What is your theory of change? Enable your supporters to play a role in producing the happy ending you work toward each day. Remember that stories have a beginning, middle, and end: Convey your mission, talk about your campaigns and projects, and explain the real impact of that work. Post photos, videos, and links to tell a fuller and more compelling story.

3. Focus on impact—At the end of the day, supporters and donors want to understand what their time and money are making possible and how it translates into social good. How do you define success? How do you know that you are succeeding? What does the “human face” of success look like? Use rich media and consistent messaging to convey these answers to your supporters. Enable the beneficiaries of your work to speak to your impact through Facebook’s various communication media, such as Causes and Pages.

4. Solicit broad participation—Being accessible helps, but you also need to explicitly ask people to get involved. Remember that your supporters come to you from a variety of starting points. Some want to learn more, and others want to have a direct impact. Some want to help from a computer, and others want to volunteer in person. Use your public posts and events to offer diverse and concrete opportunities for supporting your organization. Aim to slowly move people from lower-impact actions (such as commenting on a post or viewing a media item) to higher-impact actions (such as volunteering, signing a petition, or donating money).

5. Empower core supporters—Organizations of all sizes have passionate supporters who want to share their time, relationships, and ideas. Although your paid-staff time is finite, you can use Facebook to identify and share certain responsibilities with avid supporters. Many of our nonprofit partners regularly communicate with supporters who manage “local chapter” causes, share and comment on media items, and promote fundraising and advocacy campaigns. Come up with creative titles, assign useful tasks, and recognize your online volunteers’work.

Joe Green (@causes) is the cofounder and Matt Mahan (@matthewmahan) is the nonprofit director at Causes.

To complement these tactics from the Causes team, Jennifer Aaker, the General Atlantic professor of marketing at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, has developed a useful model for thinking about how organizations can apply the social Web to social good. She shares four steps for getting your cause off the ground.

The Dragonfly Effect: Four Ways to Use Social Media to Change the World

Jennifer Aaker

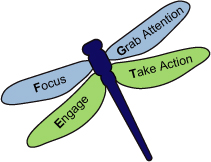

The Dragonfly Effect is a model that emanated from “The Power of Social Technology,” a class I teach at the Stanford School of Business. The framework—focus your goal, grab attention, engage others, and take action—taps social media and consumer psychological insights to create change. Named for the only insect that is able to move in any direction when its four wings are working in concert, the Dragonfly Model has four “wings” that work together to use social media to achieve unprecedented social good and customer loyalty (see Figure 14.4).

Figure 14.4

Stanford Graduate School of Business professor Jennifer Aaker’s Dragonfly Model illustrates using social media for social good.

Reprinted by permission

Consider these four tips on how to get your goal off the ground:

• Wing 1: Focus—How you identify a single concrete measurable goal.(Quick tip: Make it small, concrete, and measurable.)

• Wing 2: Grab attention—How to catch someone’s eye; it’s similar to standing in the middle of a busy street, activating your target’s fight-or-flight survival-based neurons. (Think of it as, “Made you look!”)

• Wing 3: Engage—How to create a personal connection by accessing higher emotions, compassion, empathy, and happiness. It’s about empowering the audience to care enough to want to do something themselves—and then actually do it. (Think of it as forging a connection that’s deep and real.)

• Wing 4: Take action—Enable and empower others to take action. It’s about creating, deploying, and continuously tweaking tools and programs designed to take audience members from customers to team members, furthering the cause beyond themselves. (Think of it as enlisting and enabling an army of evangelists.)

Onward and upward! To succeed in a sustainable way, we need to make it a group effort. Al Gore, the former vice president and master viral message maker (and possible inventor of the Internet), once said, “If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. ” Small acts create big change, and working in concert maximizes our capability to go farther faster in any direction that we choose. So enlist your friends, empower your followers, and get started.

Jennifer Aaker (@aaker) is the General Atlantic professor of marketing at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and coauthor of The Dragonfly Effect: Quick, Effective, and Powerful Ways to Use Social Media to Drive Social Change (Jossey-Bass, September 2010).

Healthcare

Perhaps one of the most obvious applications of social networking sites is in health epidemics, which is where we got the notion of “viral” in the first place. In the previous section, we talked about how organizations can use the social Web to reach and influence donors and volunteers. In healthcare especially, Facebook and Twitter have proven to be extremely effective in reaching and influencing clients.

The following case study showcases how an AIDS awareness campaign sponsored by the Kaiser Family Foundation has gained a strong grassroots following and is successfully spreading knowledge and social acceptance for victims of the disease in Latin America.

Case Study: Pasión por la Vida

Pasión por la Vida, or Passion for Life, is an HIV/AIDS awareness campaign across Latin America sponsored by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Fundación Huesped. Every day, more than 150 people die from AIDS-related diseases in the region. However, stigma and discrimination have kept people from talking openly about the issue in their communities.

To promote personal action in response to the epidemic, Pasión por la Vida has developed a successful Facebook Page (shown in Figure 14.5). The Page features 13 real testimonies of people living with HIV describing their passions and how they deal with the disease. The campaign Wall is updated frequently with related videos, photos, testimonies, news, tasks, and discussions from the community. The Page advances the idea that each one of us has a role to play in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

Figure 14.5

The Pasión por la Vida campaign’s Facebook Page is a success story in the making of how nonprofit and grassroots initiatives can tap into the social nature of Facebook to connect people with knowledge, information, and one another. The Page URL is www.facebook.com/pasionporlavida.

Within four months, the Page had 9,000 fans representing every country in Latin America. These fans were remarkably all interacting openly about a traditionally taboo topic. The campaign used these steps:

• Cross-promotion—The campaign’s Web site permanently and prominently links to Facebook from every page. Pasión por la Vida´s blog also promotes the Facebook Page and imports directly into the Facebook feed.

• Targeted recruiting—The campaign personally messages HIV/AIDS activists in countries with low participation. The campaign also runs Facebook Ads targeting friends of fans in those countries where penetration is low.

• Redefining fans—The Page refers to active fans as “2.0 volunteers.” Deeming fans 2.0 volunteers catapulted the total number of fans from 1,500 to 3,000 in just 3 days. The title elevated fans from passive commentators to proactive advocates for HIV/AIDS awareness.

• Calls to action—The campaign poses interactive tasks for 2.0 volunteers. For International Women’s Day, as an example, fans were encouraged to upload videos about their passions and HIV. Breaking the silence about HIV/AIDS, 40 women shared their story.

• Active participation—The 13 individuals featured in the campaign and the campaign staff keep the Facebook Page present and personal. They continually update the Page, delivering engaging and pertinent content.

The Page has become a community hub for all things related to HIV and AIDS. Users come to the Page to ask basic questions or share life stories. Facebook is the perfect platform for building this community—placing this conversation in a public space and enabling real people to do their part to fight HIV/AIDS.

Wall post:Thank you for fighting for me …. I do not live in fear or with shame. I live with PASSION!

Despite the tremendous potential utility of the social Web for healthcare applications, we first need to answer important questions regarding patient privacy and confidentiality, and the accuracy of health-related information. In the following guest expert sidebar, healthcare industry veteran Daniel Chao walks us through some of the biggest challenges currently preventing drug and medical device companies from investing in Facebook and Twitter initiatives.

Drug Companies and Social Networking—The Next Frontier

Daniel S. Chao, M. D., M. S.

The pharmaceutical industry spends $4 billion to $5 billion per year on direct-to-consumer marketing, yet it has been relatively absent from the world of social media and all the advantages discussed in this book.

Why? The answer lies in industry regulation (or lack thereof). The promotion of healthcare products is highly regulated, and regulatory violations by drug companies have resulted in massive fines. Last year, Pfizer was fined a record $1. 19 billion for the improper promotion of Bextra, a pain medication used to treat arthritis. Not only was this a hit to Pfizer financially, but it also has contributed to growing public distrust of the healthcare industry.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has largely remained silent on the topic of drug companies using social media. Most companies have decided to play it safe until the rules are clear, given the possible risks with patient confidentiality, healthcare misinformation, and so on.

In November 2009, the FDA convened public hearings on social media to give experts and the public a chance to shape the regulatory landscape. Two main issues came to the forefront:

• Off-label promotion—When the FDA approves drugs and devices, they are approved for a specific “indication.” It is legal for physicians to prescribe a drug for use that is not part of the drug’s official indication—this is known as off-label use. However, drug and device manufacturers are not allowed to actively promote off-label use.

However, if a patient or physician specifically asks the company for information about an off-label use, certain company representatives—typically those not tied to sales or other commercial functions—are allowed to respond. But what happens when a patient asks the company about an off-label use on Facebook? Is the company allowed to respond? Are other patients and physicians allowed to respond?

• Managing information—Say a patient posts a question on a drug company’s Facebook Page. A doctor responds, as does another patient. Neither of the responses is exactly correct. One of the responses contains information that is potentially dangerous. What does the company do? Delete the thread, or respond with accurate information? How quickly is the company expected to react to such a situation? Who is liable if others provide inaccurate information that results in harm?

It’s widely anticipated that sometime in the coming months, the FDA will issue guidelines on how companies can use social media for their products, finally addressing questions such as these. When this happens, expect a wave of activity from drug companies expanding onto Facebook, Twitter, and other social networking sites to communicate with their customers.

Daniel Chao, M. D., M. S., is an entrepreneur in the San Francisco Bay area.

Education

Given Facebook’s origins in college dorm rooms across the country and the social nature of school environments, another logical application for the social Web is in education. A number of educational institutions are already using Facebook and, to a lesser extent, Twitter, for a wide range of applications:

• Student groups and sports teams—Facebook is ideal for rallying students, parents, teachers, staff, and alumni around fundraising efforts, events, photos, and announcements for student groups and sports teams (see Figure 14.6).

• Incoming freshmen—At a growing number of schools, including Stanford, incoming freshmen are encouraged to join a Facebook Page or Group to receive official announcements, discover what the school has to offer, and meet their classmates before even setting foot on campus in the fall.

• Alumni—Facebook has long been a popular place for people to reconnect with their old friends and classmates. Alumni associations are also using it in a more official capacity to organize reunions and fundraising campaigns (see Figure 14.7).

Figure 14.6

This Facebook Page belongs to the Columbia High School football team in Lake City, Florida, where sports are a clear priority and matter of pride.

Figure 14.7

This Facebook event was created for the Buffalo Grove High School Class of 2000’s ten-year reunion.

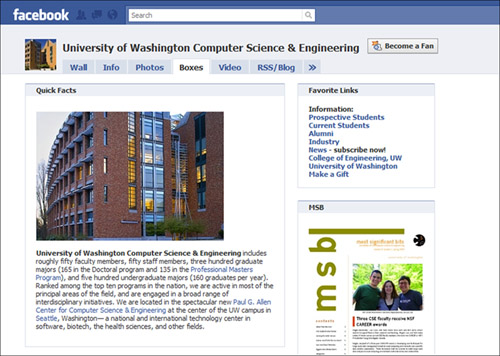

• Courses, departments, and majors—At the university level, departments, majors, and even courses are creating their own Facebook Pages and Groups to organize students and faculty. The University of Washington Computer Science and Engineering Department has done a great job on its Facebook Page, which has more than 1,000 fans and features announcements, a semiannual newsletter, videos of students and faculty talking about the department, and research updates (see Figure 14.8).

Figure 14.8

This Facebook Page belongs to The University of Washington Computer Science and Engineering Department.

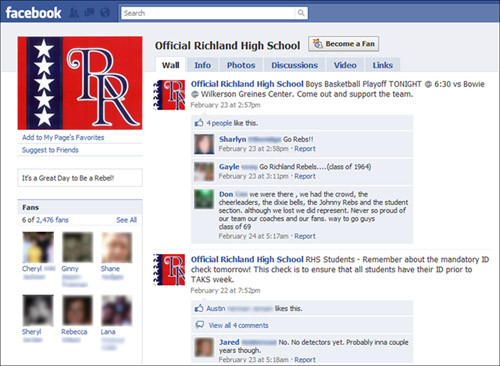

Social science teacher Daryll Johnson and high school principal Shawn Roner, who have a blog about the use of technology in education, suggest how educational groups can use Facebook to build a sense of community and improve communication in primary and secondary schools.

Using Facebook to Build Community and Improve School Communication

Shawn Roner and Daryll Johnson

Facebook has become an essential tool for people to stay in contact with friends and family, and to create a sense of community with their peers. With effective communication increasingly difficult in today’s noisy world, it makes sense for school administrators to consider using Facebook to improve communication with parents and students, and to create an interactive experience for the entire school community.

From an educator’s perspective, the ability for users to participate and help create a vibrant online community makes Web 2.0 technologies appealing. Facebook is an effective tool for school administrators because most parents and students already have accounts and log in on a regular basis. This means school administrators have a powerful communication tool at their fingertips that they can use to share all kinds of information—event updates, safety information, sports team scores, announcements, photographs, and videos.

Creating a Facebook Page or Group provides parents and students with an easy way to quickly get information, see new announcements, and connect with one another. Creating Facebook Events associated with a Page or Group enables school administrators to invite and remind people of important meetings, school functions, and other events (see Figure 14.10). For administrators who have the time, the Facebook Notes feature can provide periodic blog updates on important issues and events that give valuable information to parents. As students have long discovered, Facebook presents an exciting opportunity to improve the way we communicate—now educators and administrators just need to catch up.

Figure 14.9

This Facebook Page belongs to Richland High School in North Richland Hills, Texas. It’s a great example of using Facebook to build community and improve school communication with parents, students, teachers, alumni, and others.

It should be noted again that the minimum age to use Facebook is 13 (generally seventh grade and up), so primary school communications for grades K–6 have to be limited to parents only. Teachers and school administrators who are on Facebook should also take extra care to configure their privacy settings so that students, parents, and colleagues have an appropriate level of access (see Chapter 10, “How To: Build and Manage Relationships on the Social Web,” for how to do this).

Shawn Roner (@shawnroner) is a high school principal and Daryll Johnson (@darylljohnson) is a middle school social science teacher. They are coeditors of EDBuzz.org, a blog about using technology in education.

Political Campaigns

As in nonprofit campaigns, constituent marketing for political candidates is a perfect example of hypertargeting on the social Web. In Applebee’s America (Simon & Schuster, 2007), authors Ron Fournier, Douglas Sosnik, and Matthew Dowd make the compelling case that George W. Bush won the 2004 presidential election in large part because of his team’s marketing savvy and knowledge of “the customer.” The Bush team conducted the most extensive demographics and market research in campaign history, segmented different constituents of voters, and targeted each group with messages and promises that resonated with their “gut values.” And that was when Facebook had eight million users, before anyone had ever heard of hypertargeted ads.

The Obama 2008 team understood this and did an even better job of targeting voters— aided in no small part by Facebook cofounder Chris Hughes, who took a sabbatical at the company to work for Obama’s presidential campaign. The following case study walks through how the 2008 McCain and Obama campaigns differed in their use of social media.

Case Study: 2008 U. S. Presidential Campaign

Ray Valdes

When first hearing about social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter, many people remark, “Social networking seems like light-hearted fun-and-games— which is all well and good, but what is the tangible business value? What real-world impact can result from these mostly trivial online interactions?”

One can respond to this question by pointing to the 2008 U. S. presidential election as a case study in effective use of social media. In that campaign, social networking and social media techniques played a major role in determining the outcome. It’s hard to find an event in our society that has greater impact on business and finance than the outcome of this election, no matter what country you live in. And a pragmatic footnote is to point out that not just the votes, without obvious world-historical impact, but also $700 million in political contributions directly resulted from social media—a number that surely gets the attention of any businessperson.

This is not to assert that a hugely complex and multidimensional phenomenon such as the presidential election was determined by a single factor. Without getting into detailed political analysis (which is always subject to debate), it’s clear that a large set of diverse factors played a role: highly entangled issues—such as the economy, the war, political parties, and interest groups—and the complex interplay of candidates’ responses to events.

Having said that, take a moment to tune out the labyrinth of factors, set aside your political leaning, and look at the valuable lessons for business—in terms of both defensive maneuvers and aggressive offense.

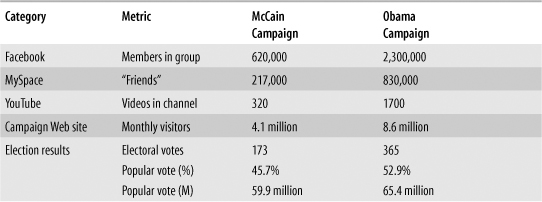

Table 14.1 is a social media scoreboard for the two campaigns, McCain versus Obama in 2008.

Table 14.1 Social Media Activity—2008McCain Versus Obama Campaigns

As you can see, Obama outpaced McCain in every metric relating to social media by anywhere from 2:1 to as much as 6:1. This led to a decisive victory in terms of state-by-state electoral votes and a healthy margin in terms of popular votes.

It’s fair to ask the chicken-and-egg question: Aren’t these social media metrics a mere reflection of broad public sentiment? What makes you think they’re a driving factor?

In the 2008 campaign, it’s clear that the participation in social media was both a leading indicator of later shifts in public opinion and a driving force in raising money and moving people to act. The Obama campaign was able to get 100,000 people to show up at a rally in St. Louis by getting the word out through inexpensive and fast social media channels. In the course of the campaign, it amassed a list of eight million supporter names and mobile phone numbers, and sent them emails, text messages, Twitter status messages, and Facebook updates.

One benefit of social media has been to lend visibility to campaigns at critical times. For example, the Facebook Group for the Obama campaign was very helpful when the campaign was getting started. Months later, the independently produced “Obama Girl” music video spread virally on YouTube and broadened the scope of the campaign’s visibility. Finally, the well-crafted My. BarackObama.com portal (based, in part, on the MovableType blogging platform) proved effective in mobilizing supporters for get-out-the-vote efforts on an unprecedented geographic scale. More than visibility, a key factor was the capability to solicit funds: Obama’s campaign reportedly raised $638 million from more than three million individual donors, with an average donation of less than $200.

The campaign social toolbox not only included a Facebook Group and Twitter account, but also an iPhone app that provided up-to-the-minute news and event information. As the political stakes get higher, campaigns rely on skilled staff and specialist contractors who have innovated their own proprietary techniques. For example, MoveOn.org released an effective get-out-the-vote message that integrated email, Web, and highly personalized video to create a compelling experience for the targeted recipient (see www.cnnbcvideo.com).

Ray Valdes (@rayval) is the vice president of research at Gartner Group.

Other political campaigns are starting to take notice. Last year, political rookie Patrick Mara used Facebook hypertargeting to defeat 16-year incumbent Carol Schwartz in a Washington, DC, city council primary. He used this targeting strategy:

• Gays and lesbians—Mara’s team pushed information about his stance supporting gay marriage to everyone on Facebook who listed their sexual orientation as gay.

• Parents—Mara’s team pushed ads about the public school system and education reform to everyone on Facebook with kids.

• Republicans—Mara’s ads to self-identified Republicans on Facebook were about tax cuts, school vouchers, and other conservative darlings.

• Location—All of Mara’s ads were location-targeted to people in the Washington, DC, area.

By directing specific messages that hit home with each of his voting constituents, Mara was able to establish the “gut values” connection that Fournier and his colleagues describe to defy all odds and win the election. Not only did Mara succeed in winning votes, but his hypertargeted messages helped recruit volunteers and grassroots donations.

In the following guest expert sidebar, Ray Valdes from Gartner Group explains why political campaigns are the ultimate marketing and branding exercise.

Political Candidates: The Ultimate “Considered Purchase”

Ray Valdes

Strong similarities exist between promoting a candidate and promoting a brand or product. In political campaigns, the candidate is being sold—the “product” that is being marketed to voters. This is a transaction whose economics are based not on money, but instead on the currency of trust, perception, and reference.

You can view the election of a president as the ultimate “considered purchase,” in which prospective buyers invest a lot of time and effort in weighing alternatives before choosing. The presidential campaign process spans a multiyear time frame and, for 2008, consumed $2.5 billion in aggregate spending, ultimately resulting in a single “transaction”—actually, 130 million individual transactions (votes) executed on a single day.

As with any considered purchase, prospective buyers go through these decision phases:

• Awareness

• Consideration

• Transaction

• Fulfillment

• Loyalty

• Evangelism

The political sphere is unique because after an individual voter makes the purchase decision, no feedback loop is available about the outcome of that purchase to others considering the same item. This is different than a consumer decision to go to a movie, for example. In that scenario, the past experience of others with the same product provides valuable feedback for those who haven’t yet made the choice. In the case of presidential elections, such post-sale feedback is not available, so the decision process must be based on perception instead of reality.

Therefore, political campaigns place an inordinate emphasis on less tangible aspects, such as branding, competitive positioning, and endorsements by trustworthy authorities. Successful candidates establish a distinctive brand, position it favorably, and also attempt to reposition their competitors in an unfavorable light. They use a wide range of media—paid media, “earned media”(conventional mainstream news), and social media—to communicate both factual information and content that works at the emotional level. In the presale phase, social media can be tremendously effective in shaping perception because of aspects that are personalized, participatory, peer-to-peer, and authentic.

Social sites and services enable campaigns to directly communicate in a personalized manner to an audience, and also enable “unofficial” communications (peer-to-peer instead of brand-to-consumer) that are often perceived to be more relevant, authentic, and credible than the official sources—and, therefore, are more effective in communicating the brand.

Ray Valdes (@rayval) is the vice president of research at Gartner Group.

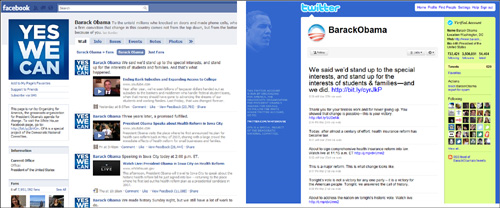

Not only is the social Web valuable during the campaign process, but also elected officials such as President Obama are continuing to use Facebook and Twitter post-election to stay connected to voters. Nearly 8 million people “like” Obama’s Facebook Page and 3.5 million people follow him on Twitter (both managed by Organizing for America, a grassroots organization for Obama’s agenda), and he uses these as important channels to provide policy updates; rally support for bills; encourage people to vote in city, state, House, and Senate elections; share videos of speeches; and highlight issues that are personally important to him (see Figure 14.10).

Figure 14.10

President Obama has continued to use social media channels such as Facebook and Twitter while in office to communicate and connect with his constituents.

![]() As powerful as the social Web can be, you should view it as only one part of an integrated multichannel strategy that includes email, phone, print, and face-to-face interactions with your stakeholders and constituents.

As powerful as the social Web can be, you should view it as only one part of an integrated multichannel strategy that includes email, phone, print, and face-to-face interactions with your stakeholders and constituents.

![]() A vast majority of the same concepts, strategies, and tactics covered in the earlier chapters for businesses apply to nonprofits and political campaigns. The biggest difference is that, instead of optimizing for monetary value, there’s a second bottom line of public good and social return.

A vast majority of the same concepts, strategies, and tactics covered in the earlier chapters for businesses apply to nonprofits and political campaigns. The biggest difference is that, instead of optimizing for monetary value, there’s a second bottom line of public good and social return.

![]() Nonprofit and political advocacy are especially well suited for the social Web because of their highly personal, social, and emotional nature.

Nonprofit and political advocacy are especially well suited for the social Web because of their highly personal, social, and emotional nature.

![]() The Dragonfly Model is a helpful framework for launching social causes. The four steps are focus, grab attention, engage, and take action.

The Dragonfly Model is a helpful framework for launching social causes. The four steps are focus, grab attention, engage, and take action.

![]() Political campaigns can take a cue from Barack Obama and Patrick Mara on how to use Facebook hypertargeting to reach and appeal to different constituents of voters based on their “gut values.”

Political campaigns can take a cue from Barack Obama and Patrick Mara on how to use Facebook hypertargeting to reach and appeal to different constituents of voters based on their “gut values.”

> > > TIPS and TODO’s

![]() Come up with a marketing and branding plan for your nonprofit or political candidate just as you would for a product or company in the for-profit sector.

Come up with a marketing and branding plan for your nonprofit or political candidate just as you would for a product or company in the for-profit sector.

![]() Don’t ask for dollars off the bat. Start by getting people involved with their time and energy, such as signing petitions, attending events, wearing your merchandise, and volunteering. Check out popular Facebook applications for nonprofits and political campaigns, including Causes, My Merch Store, and CafePress Listings.

Don’t ask for dollars off the bat. Start by getting people involved with their time and energy, such as signing petitions, attending events, wearing your merchandise, and volunteering. Check out popular Facebook applications for nonprofits and political campaigns, including Causes, My Merch Store, and CafePress Listings.

![]() Use the rich multimedia capabilities on Facebook for sharing videos and photos to tell a story and create an emotional connection with audiences.

Use the rich multimedia capabilities on Facebook for sharing videos and photos to tell a story and create an emotional connection with audiences.

![]() Manage your Facebook and Twitter privacy settings to make sure you are not oversharing personal information (especially if you are a teacher, social worker, politician, or other public figure).

Manage your Facebook and Twitter privacy settings to make sure you are not oversharing personal information (especially if you are a teacher, social worker, politician, or other public figure).

![]() If you are a political candidate or political support organization, maintain your presence on social networks even after winning an election to stay close, connected, and communicating with your constituents.

If you are a political candidate or political support organization, maintain your presence on social networks even after winning an election to stay close, connected, and communicating with your constituents.