1. The Fourth Revolution

“In the technology industry, people always overestimate

what you can do in one year and underestimate what you

can do in one decade.”

—Marc Benioff, founder and CEO, Salesforce.com

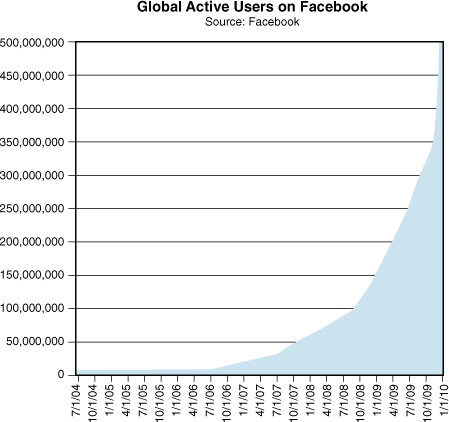

Approximately once a decade, a new technology platform emerges that fundamentally changes the business landscape. In each case, regardless of prior competitive dynamics, businesses that understand and appropriately adopt the technology win, while those that fail to do so lose relevance. In the 1970s, this was mainframe computing. In the 1980s, it was the PC. In the 1990s, it was the Internet. And today it is the social Web (see Figure 1.1).

The social Web revolution is already well underway. More than 750 million people around the world are on social networking sites. And not only are they signing up for accounts, but they are also logging in, spending more than 20 billion minutes a day on Facebook alone. More than half of Facebook users log in at least once a day. That is a tremendous amount of attention from a tremendous number of people. Many are using social networking sites as their main entry point to the Web, choosing content based on what appears in their Twitter stream and Facebook news feed. Facebook is the new Internet portal.

The social Web is not just Facebook, of course—it also includes Twitter, LinkedIn, MySpace, Renren in China, Mixi in Japan, Odnoklassniki in Russia, and hundreds of others. I simply refer to the current state of the Internet as “the Facebook Era” because Facebook is the largest social networking site globally by an order of magnitude. Facebook recently even beat out Google in becoming the most trafficked site on the Internet, according to Hitwise and other sources.

Figure 1.1

Facebook has had spectacular growth both in the United States and globally, recently topping 500 million users worldwide.

As you decide where to invest in building a presence, it’s important to think about where your target audiences are spending time. Of the college students we surveyed for the first edition of this book, 94% said they do not use email on a regular basis. They prefer text messages and Facebook Wall posts. What happens when these cohorts of individuals graduate and become the people you are trying to hire, manage, and market to?

But not just college students use the social Web. More than 60% of Facebook users are older than 25. The largest increase in Facebook and Twitter users actually comes from users aged 35–49. And surprisingly, the fastest-growing audience on Facebook is women over 55, an impressive feat considering that this group traditionally tends to be technophobic. People are increasingly relying on social networking sites as a primary means to communicate with friends and get the news. As companies, we need to be where the customers are and communicate through the channels they prefer, and a growing number of people are preferring social networking sites.

Why? The social Web appeals to innate human desires for self-expression, human connection, and a sense of belonging. These desires are especially strong online. Before social networking sites, many users found the Internet overly vast, unnavigable, and anonymous. Social networking sites such as Facebook capture our pictures, feelings, and relationships, and make the Web feel human again.

In the following guest expert sidebar, Don Tapscott, best-selling author of 14 books on business and society, including Wikinomics and Grown Up Digital, offers some historical context on social networking and describes what’s in store for the future.

Social Networking Has Been a Long Time Comin’

Don Tapscott

I remember my first job at Bell Northern Research in the late 1970s. I worked with a team of technologists and social scientists whose task was to understand what was then called “The Office of the Future.” Our group was trying to understand how multifunction workstations connected to a vast network of networks would change the ways people communicated. At the time, only programmers used computers.

I was fortunate enough to collaborate with some of the pioneers of the digital age, such as Stanford Research Institute’s Douglas Englebart. I’ll never forget him showing me his “augmented knowledge workshop” complete with hypertext, collaboration tools, and a strange device he called a “mouse.” One of the applications we created was something called “computer conferencing”—the forerunner to today’s social networks. From the experience, I became convinced that collaborative computing would change the world.

But when I wrote a book on the topic in 1981, critics told me this idea of everyone using computers to communicate would never happen, giving a most bizarre reason—managers would never learn to type. No one could have predicted that not only would managers learn to type, but they would type with their thumbs.

The ideas of Englebart and other pioneers were ideas-in-waiting—waiting for a number of technological, social, economic, and demographic conditions to mature.

One of the developments these ideas were waiting for was Facebook. My son and daughter, whose email addresses ended in “.edu” at the time, gave me a demo. When I saw it, I knew this would change the world.

Flash forward a few years, and what we see today is nothing less than a social revolution. Social networks are becoming the new operating system for a business, changing the metabolism of work, innovation, customer interaction, and performance for the better.

The next step is social networks becoming a new mode of production. Anthony Williams and I discussed this in our book Wikinomics, and as evidence of the widespread interest in the topic, the book was the best-selling management book of 2007. Social networking is becoming social production. We’re in the early days of profound changes to the deep structure and architecture of the corporation and most other institutions in society. Buckle up.

Don Tapscott (@dtapscott) is the best-selling author of 14 books on technology, business, and society, including the upcoming MacroWikinomics: Rebooting Business and the World (Penguin Group, September 2010).

Yes, definitely buckle up. This chapter provides important context for understanding the Facebook Era by looking at the technologies that led up to online social networking, comparing different social networking sites, and explaining the significance of social network platforms, including Facebook for Websites.

Today’s Social Customer

In previous eras, the workplace prompted the adoption of new technologies. Online social networking is different. It is a movement that affects us personally first, professionally second. Most of us get on Facebook to connect with friends before thinking about using it for business purposes. In some cases, the lines blur between our personal and professional worlds: We befriend colleagues and customers, refer friends for jobs at our employer, and make business purchase decisions based on a friend’s recommendation.

The role of the customer is changing, too. Customers used to be passive recipients, waiting for new products to come out or waiting on hold to speak to a call center rep. Today they are waiting no longer. Every customer and employee suddenly has a voice, and what they say matters. Whether companies like it (or even know about it), customers are demanding to become active participants across your business. They want to contribute new product and feature ideas, and receive an instantaneous response when something goes wrong. If you can win over this new breed of customers, they will become your volunteer sales force (spreading the gospel of your company to friends) and support staff (answering questions from other customers on Twitter).

Companies have no choice but to become transparent, responsive, and collaborative, or else risk going out of business. Everything is changing around customer expectations, customer participation, and how companies are organized. As we saw with the Internet, PC, and Mainframe Eras before it, mastering the Facebook Era has become the new competitive advantage for businesses. Just as ten years ago we had to learn how to Google and email, today we have to learn Facebook and other social technologies to be effective in our personal and professional lives.

Déjá Vu: What We Can Learn from the Internet Era

How things have changed in the 15 years since the Internet went online! The previous decade revolutionized how we live and work with the World Wide Web of information— linking Web pages, indexing content, and searching for information.

This decade, a World Wide Web of people has emerged—linking individuals, indexing the social network map of who is connected to whom and how, and delivering the right experience to the right person at the right time. The Internet Era connected all our machines and content pages. The current digital revolution is in capturing and using information about how we as individuals are connected. Metadata about Web pages, such as headings, keywords, and links, has been crucial for enabling us to manage and navigate an eruption of content on the Web. Similarly, metadata from the social Web about individuals—such as what networks they belong to, how we know them, and who we know in common—has become crucial for enabling us to manage many different kinds of relationships with large numbers of people. It took five years for the Internet to reach 350 million users. The same is true for Facebook.

Similar to how the Internet enabled businesses and individuals to access, consume, and manage far more information than previously possible, the social Web is enabling businesses and individuals to access and manage far more people and relationships than in the past to become more empowered and productive. In Chapter 3, “How Relationships and Social Capital Are Changing,” we discuss the implications for personal networks, professional ties, and social capital.

But merely signing up for an account on Facebook won’t revolutionize your business. Success requires patiently persevering, planning strategically, and applying the new technologies in the appropriate ways. We can learn a lot from studying how companies went through the sometimes painful process of adapting to the Internet Era a decade ago. The following sidebar walks through Bloomingdale’s department store’s attempt to get online. We can apply the same lessons Bloomingdale’s learned about the Internet to how companies today approach opportunities on the social Web.

Internet Sales at Bloomingdale’s Department Store, Take Two

In 1999, Federated Department Stores (FDS, now Macy’s, Inc.), which owns Bloomingdale’s, acquired e-commerce and online catalog company Fingerhut for $1.7 billion in what was seen as one of the most aggressive Internet plays in the industry. FDS planned to use Fingerhut’s technology to create Bloomingdales.com, an online version of its Bloomingdale’s By Mail paper catalog.

But just a few years later, they had very little to show. Customers did not see any benefit to shopping on the Web site, which was just an online replication of the print catalog. They were also not accustomed to making purchases on the Internet. Company executives decommissioned the e-commerce site, writing it off as a very expensive failure.

After a brief hiatus from Internet sales, Bloomingdales.com was reincarnated with a new approach that took advantage of the unique power and capabilities of the Internet. The new site was dynamic, engaging, and easy to search or browse in multiple different ways—by brand, size, genre, color, material, and price. Sophisticated online search marketing and email marketing campaigns now drive traffic and track each Web visit. All these were missing from the first version of the site and are simply not possible in a print catalog.

Now the fastest-growing part of the business, Bloomingdales.com has enabled the company to better engage its traditional customer base and reach new audiences while reducing costs. It has been so successful that Macy’s, Inc., has decided to discontinue the Bloomingdale’s By Mail paper catalog, previously a hallmark of the company, to focus the direct-to-consumer strategy entirely online.

We can learn a few important lessons. First, even a technology revolution as powerful as the Internet (or now, Facebook) cannot in and of itself transform businesses. Success requires both a well-thought-out strategy and a market ready for the technology. Today people are finally ready and willing to buy online. Bloomingdale’s uses sales data and customer segmentation to determine what merchandise to sell via which channel. Second, you gain from the new technology only if you use it to accomplish something that was not possible before. Merely posting a digital version of a static print catalog on its Web site was not transformative. But creating a new catalog experience with dynamic images, hyperlinks, and related item recommendations has paid off with real results.

What behaviors and interactions are your customers ready for and expecting from your company’s social presence? In what new and creative ways will you engage them, instead of re-creating the same possibilities from the Internet Era inside the new social medium? The next chapters strive to help inspire answers to these questions.

The Evolution of Digital Media

Along with each digital revolution comes new forms of media. For example, look at how encyclopedias have evolved. In two decades, we have gone from heavy, leather-bound World Book volumes, to the Microsoft Encarta CD-ROM, to user-generated Wikipedia online, to the real-time messaging service Aardvark.im that connects people seeking information with knowledgeable experts in their network. Over time, new technologies are making it easier to deliver the right content in the right context at the right time while reaching larger audiences at a lower cost.

Mainframes digitized media, making it vastly more efficient and less expensive to store. Software on PCs has made it easy for anyone to create personalized digital content. The Internet has become a powerful distribution mechanism for media, which provides incentives for people to get involved in creating content and publishing their work. The result has been an information explosion.

During the last 15 years, we have been fighting a seemingly endless uphill battle against spam in our inboxes. When searching for information, we wade through pages of search results that are out of context. Annoying floating banners that are irrelevant to us block the screen showing the online article we are trying to read.

But all hope is not lost. The social Web might provide an opportunity to align what publishers and advertisers want to show with what users want to see. Technology companies have spent several years developing different ways of filtering the massive amount of information, such as content aggregation, search, and behavioral targeting. With the social Web, we can improve on this further by using friends, people who “like” our Facebook Page or @mention us, and people we follow as “social filters” for making sense of the vast amount of content on the Web.

Digital media is getting smarter. With technologies such as Facebook for Websites (explained later in the section on social network platforms), businesses are rethinking and redesigning the Web experiences they provide customers and prospects to become social, personalized, and real-time. Already, their efforts are paying off with improved engagement, sales, and loyalty.

Social Networking Versus Social Media

People often use the terms social networking and social media interchangeably. Social networking often facilitates many forms of social media, but a lot of social media also exists outside of social networking sites.

Social media (or user-generated content) includes blogs, wikis, voting, commenting, tagging, social bookmarking, photos, and video. Social media is all about content. People are secondary; they just happen to interact with the content by posting, commenting, tagging, voting, and so on.

Social networking sites turn the content-centric model on its head. Every social networking site has two components: profiles and connections. Facebook and LinkedIn, in particular, are all about people and relationships. Now most social networking sites also have features that also enable user participation such as tagging, commenting, voting (known as “liking” on Facebook), or posting photos. But on social networks, the content is secondary and temporary to the people.

The distinction between social networking and social media might seem trivial, but it’s not. Even the most viral of videos on YouTube eventually falls out of favor. Content gets stale, but people never tire of seeing updates from friends and sharing about themselves. Social networking sites bring social media to life by enabling people to easily share media to entertain, inform, and connect with friends, customers, and others.

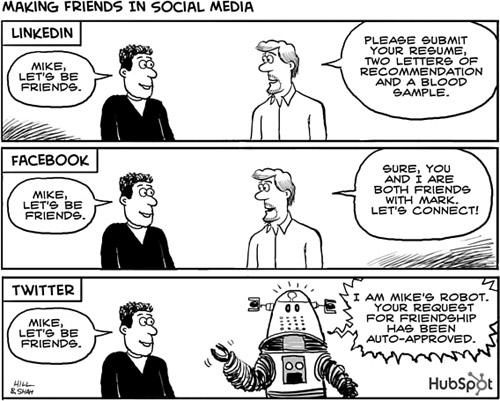

Facebook Versus Twitter and LinkedIn

People always ask if they should be on Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn—the top three social networking sites in North America. The answer is that it depends on what you are looking to get out of being on a social networking site. The answer might be that you need to be on all three, each for different reasons and perhaps with different levels of investment (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2

Making friends in social media

This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.

At the risk of overgeneralizing, here are some factual and reputational differences of these top social networking sites.

Comparing Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn

Audience size and composition:

• With 500 million active members, Facebook is by far the largest global social networking site, in terms of both the number of users and time spent on the site. Facebook users span every age group and demographic, but the site is especially popular among college students and recent graduates. Facebook tends to be oriented toward personal friends and relationships, which presents both unique opportunities and challenges to businesses.

• Twitter has approximately 50 million users, although critics question how many are active or spammer accounts. Twitter strives to keep its service simple by limiting updates to 140 characters in length. It is heavily used by media and celebrity personalities but is going mainstream. Unlike the more enclosed environments on Facebook or LinkedIn, most messages on Twitter are public and searchable.

• LinkedIn focuses exclusively on business professionals. It has approximately 50 million members, mostly in the United States and Europe. Users tend to skew older, with an average age of 40. The site is used heavily for recruiting and business-to-business (B2B) business development. Users typically don’t spend time engaging on the site, but instead log in occasionally to accept or initiate a connection request, search for people, or send a message.

How businesses typically engage:

• Facebook ads; Facebook applications; Facebook Business Pages (which are similar to Facebook profile pages for businesses and are used for sharing updates, special offers, video, photos, events, and applications).

• Twitter streams (sharing updates, special offers, and discounts or answering customer support questions).

• LinkedIn Pro and LinkedIn Recruiter enable enterprise-grade search and communication to individuals of a certain profile for recruiting or business development purposes; advertisting.

Best suited for:

• Facebook: Business-to-consumer (B2C); both big brands and SMB.

• Twitter: News and media companies; B2C; customer service.

• LinkedIn: Recruiting, B2B products and services.

Concerns:

• Facebook: Strict privacy policies limit access to people’s data, and platform advanced programming interfaces (APIs) are constantly changing.

• Twitter: Spam.

• LinkedIn: Insufficient audience size and engagement.

How to determine business fit:

• Check your audience size on Facebook. Go to http://facebook.com/ads/create. Ignore all the instructions around creating an ad. Scroll down to Step 2 (where it says “targeting”) and select criteria that best describes your target audiences. Near the bottom of Step 2, you will see an estimate from Facebook showing how many Facebook members fit the profile you specified. If it is a significant number (say, over 10% of your current or target customer base), then you should be on Facebook.

• Checking audience size and relevance on Twitter is less of a science. Go to http://search.twitter.com and search on your business name, competitors, and keywords relating to your business. If you get a sizable number of search results, then you should consider getting on Twitter.

• Check your audience size on LinkedIn. Go to www.linkedin.com/directads and fill out test data for Step 1. Under Step 2, specify audience category criteria and LinkedIn will display how many of its members fit your desired profile. If it is a significant number, then you might want to advertise on LinkedIn.

Why Facebook Won

As early as 1995, online social networking pioneers such as Classmates.com and SixDegrees.com introduced the notion of profile pages and friend connections. Next came Friendster, Orkut, MySpace, Bebo, and Hi5. These early social networking sites were tremendously popular, attracting tens of millions of users (or, in MySpace’s case, more than 100 million users) but have largely disappeared from the scene or been forced into certain regions or niches.

Why did this happen? How did Facebook grow from a dorm room project to overtake MySpace and now dominate the social networking space by an order of magnitude? Two reasons: user trust and engagement.

First, Facebook’s founders realized early on that people would log in only if the social networking site contained valuable information, and people would share valuable information only in an environment they trusted. During the last several years, the site introduced a number of features that have helped create a trusted environment on Facebook. Most of the other social networking sites don’t have any of these features.

• Email domain authentication—Facebook doesn’t allow you to join a college or employer network unless you can authenticate with an email address in that network. For example, to join the Harvard network, you have to sign up with an @harvard.edu email address. This makes it much harder for people to pretend to be someone they are not.

• Real relationships—From the beginning, Facebook was designed around real-world networks such as schools, employers, and other organizations. Facebook has always encouraged people to initiate and accept friend requests only from real people they actually know. In contrast, no such norms existed on Orkut or Friendster, so many people began accepting random friend requests from strangers. When strangers outnumbered friends on these sites, people no longer felt comfortable sharing personal information and stopped logging in.

• Privacy settings—Facebook also was the first to introduce privacy settings that enable users to categorize friends under lists and choose to share different amounts of information with different groups of people. Knowing that they can restrict others’ access to all or certain parts of their profile gives Facebook users the confidence to share more about themselves.

• Exclusiveness—Initially, Facebook was available at Harvard only. Then it spread to other Ivy League schools. Its gradual expansion to other colleges and eventually to the public created a certain cachet of exclusiveness that made it seem more trusted and desirable. Adding only a few schools at a time also enabled Facebook to grow smoothly and predictably. In comparison, rapid growth on Friendster and Orkut often brought down those sites, turning off many of their users.

The final secret to Facebook’s success has been keeping its users engaged on a continual basis. Its news feed, which broadcasts updates such as new photos and links posted, likes, comments, and event RSVPs, really set Facebook apart from the other social networking sites. Each person’s news feed appears on his or her profile page, and a summary of feeds from all your friends appears on the home page when you first log in. It’s ironic that the news feed, which has been instrumental to Facebook’s longevity and has become a core feature of Internet applications today (including the basis for Twitter), was initially a huge source of controversy around privacy issues. In contrast, Friendster, Orkut, and Classmates.com fell out of popularity after the initial thrill of reconnecting with old friends wore off.

And what about the future of Facebook? At this point, all bets are on Facebook. In the social networking world, success begets more success. The more people are on a social networking site, the more people join. If all your friends and customers are on Facebook, you feel pressure to also be on Facebook to participate. You are less likely to join a different social network that contains fewer people and is therefore less valuable. Although Facebook might not be around forever, it seems likely to be here for quite some time.

Google Buzz

Just when we thought it was mostly down to Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn, Google has jumped into the race with Buzz, a new social sharing service for Gmail users. (It has approximately 176 million users worldwide, compared to 500 million Facebook users.) Google Buzz enables users to turn Gmail contacts into a social network and post status updates, photos, and links (similar to Facebook), but according to a one-way follower model (similar to Twitter).

Google Buzz is still a young technology, but it has potential. Google has a lot of smart people, a lot of resources, a lot of our data, and instant distribution to more than a billion users across its Web properties and applications. Buzz has three big areas of opportunity. First, Google could use email contacts as a more accurate and up-to-date implicit social graph, versus the Facebook/Twitter/LinkedIn social graphs that are all explicit. (Users must initiate and accept each connection.) Second, Google could leverage its breadth to weave a much richer social experience across a lot of applications including mobile, maps, search, email, YouTube, Picasa, and Google Reader. Thus far, the other social network ecosystems are not nearly as robust. Finally, Google could mesh multiple communication modes, including voice, chat, email, status updates, and documents or spreadsheets.

It’s probably too early for most businesses to focus on Google Buzz (and a related technology, Google Wave), but I recommend keeping an eye out for developments.

Private Social Networks

Besides public, all-purpose social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter, it is also worth discussing private social networks, such as those hosted on company Web sites or on Ning. Private networks tend to be affinity- or association-based networks instead of purely social networks in which people connect with the friends they choose.

Many larger organizations, in particular, have added community and networking capabilities to their Web sites to better engage visitors or improve search engine rankings. Certainly, this makes sense if at least one of the following is true:

![]() Your site offers something that people are willing to sign up and log in to obtain.

Your site offers something that people are willing to sign up and log in to obtain.

![]() You are able to drive a lot of traffic to your site.

You are able to drive a lot of traffic to your site.

![]() You want to remain exclusive instead of driving as much traffic as possible.

You want to remain exclusive instead of driving as much traffic as possible.

If you check all these boxes, then it probably makes sense for you to build your own online community, perhaps in addition to having a presence on Facebook and Twitter. You might consider using Facebook Platform’s social plugins (described later in this chapter) to establish crossover points between your Web site and Facebook.

“Dogs are people, too,” Del Monte’s invitation-only online community for dog lovers, is a good example of a private network. By creating an exclusive environment for dog lovers to meet and discuss their passion for dogs, Del Monte has been able to effectively conduct market research and generate new ideas for their Snausages products while cultivating a loyal, passionate customer base. Other good examples include ESPN’s fantasy football league Web site, Pampers’ community for new mothers, and Groupon’s Web site for daily deals.

A number of technology platforms on the market offer Web community and social networking features, including Lithium, Jive, Telligent, Pluck, KickApps, and Drupal, which is open source. The easiest private social networking service to get started with is Ning, which lets anyone create a social networking site in a few minutes, using point and click.

For example, John F. Kennedy High School in New Orleans, Louisiana, used Ning to create a comprehensive site for alumni, parents, and students featuring school news and events, the capability to connect with classmates and teachers, photos, videos, and fund-raising (see Figure 1.3). Thanks to Ning’s Web tools and ready-made templates, high school administrators were able to get a site up and running in a fraction of the time. The school’s private social network was especially important for the Kennedy community after Hurricane Katrina forced students to evacuate at the beginning of the 2005–2006 academic year. The site enabled parents and administrators to support one another, share information, and help facilitate transfers to other schools.

Figure 1.3

New Orleans, Louisiana–based John F. Kennedy High School’s specialized social network community hosted on Ning

Other examples of organizations that have created Ning networks include The Epilepsy Foundation, Essence Magazine, and the Boston Chapter of the American Marketing Association. Today Ning hosts hundreds of thousands of specialized networks on its free, ad-supported version.

Should you create your own social network or go with Facebook Pages and Twitter? It’s a trade-off. With your own network, you get to control the full experience and own the data, but you face the problem of getting traffic. With Facebook and Twitter, you can reach half a billion people, but you give up some control and risk getting lost in the crowd. Ultimately, the key questions are “Is your site compelling enough for people to visit and continually return to?” and “How much money and energy are you willing to invest to retain control?”

Social Network Platforms

The first online social networks were just Web sites. Today they are software platforms, which means that, in addition to the Web site Facebook creates and maintains, third-party software developers can build new applications that extend Facebook’s functionality. Social networking platforms expose data, tools, and screen real estate to developers. We saw a similar phenomenon during the PC Era when Microsoft exposed its Windows platforms so that third-party developers such as Adobe, Lotus, and Frame Technology could create applications such as Photoshop, Lotus 1-2-3, and Framemaker. In an ideal scenario, the platform ecosystem is a win–win–win for everyone: Users have access to more functionality, software developers have access to data and users, and the social network becomes more interesting, valuable, sticky, and engaging.

The rise of YouTube is a good example of how this works. An important precursor to social platforms was the capability to embed YouTube videos on MySpace pages. Before MySpace, YouTube struggled to hit a tipping point and really take off. It had a small and scattered community of fans that used its video-sharing service as one-offs. Joining forces with MySpace changed everything. Overnight, YouTube found itself with a large global audience and infrastructure for word-of-mouth distribution. MySpace, in turn, saw its Web traffic go way up and its pages come to life with rich, multimedia video.

Facebook took this idea of embedded video further when it created the first social networking platform in May 2007 that enabled users to create any type of application (not just video) inside Facebook. Today Facebook has more than 500,000 platform applications (see the full list at http://facebook.com/apps). More than two-thirds of Facebook users have installed at least one platform application. Shortly after Facebook unveiled its platform, MySpace, Bebo, Hi5, Friendster, and eventually LinkedIn followed suit with their own platforms. Twitter is also famously easy to integrate with. Its application programming interface (API) has spawned a number of popular client and Web-based applications, including TweetDeck, Twitterholic, Digsby, Seesmic Desktop, and Twitpic (see the full list at http://oneforty.com). More than twice as many people interact with Twitter via a platform application than on Twitter.com.

Platform Applications

When social networking platforms emerged, most of the early applications were games. For example, companies such as Zynga, Playdom, and Playfish (acquired by Electronic Arts) have created applications that let Facebook users challenge friends to games such as math puzzles, trivia, or checkers. Many of the newest and most popular social games— such as FarmVille, Café World, Restaurant City, Mafia Wars, and Texas Hold ’Em—involve virtual goods in which players exchange real money for virtual items such as farm animals, restaurant equipment, and poker chips for use in games. Despite the fact that users can never exchange these virtual goods back to real money, people love social games. Games have become the most installed applications on Facebook. On Facebook alone, the virtual goods economy is expected to surpass half a billion dollars this year.

Whereas Facebook and Twitter’s platforms are open to any developer to build applications, LinkedIn has restricted its platform to a handful of select partners. The most popular LinkedIn apps today are Slideshare (displays Slideshare presentations on user profiles), Amazon Reading List (enables users to share reading lists with networks and connections), and WordPress (enables users to display blog posts on their profiles).

But it’s not just technology and games companies that are successfully building platform applications on social networking sites. Traditional businesses are also starting to explore the benefits of plugging into the online social graph with their own platform applications. Pizza Hut has developed an application that Facebook members can install on their profile page. Visitors to the page can order pizza delivery directly from within Facebook.

Another example comes from FamilyLink, a genealogy database company that provides ancestry-tracking tools to approximately 20,000 subscribers. FamilyLink developed a Facebook app, We’re Related, that lets people indicate who they are related to on Facebook and create family tree visualizations. In less than two years, 18 million Facebook members have signed up for We’re Related, enabling FamilyLink to promote its brand to a far greater audience than its original customer base.

Certainly for companies such as Pizza Hut and FamilyLink, Facebook applications have nicely complemented their marketing efforts. How might platform applications increase Facebook audience engagement for your business? Chapter 11, “How To: Engage Customers with Facebook Pages and Twitter,” explains your options and helps you decide what makes the most sense for your company and goals.

Expanding the Social Web

So far, we have talked exclusively about applications that appear inside social networking sites. Some companies (especially small businesses) are ditching the idea of having a separate Web site and are using a combination of Facebook Pages and applications. Although these continue to grow in number, most applications and Web sites today are still not on Facebook. And sometimes it doesn’t make sense for a particular application to live inside Facebook.

The Faceconnector application that Todd Perry and I developed, which integrates Facebook and Salesforce (actually created before Facebook Connect or Facebook for Websites), is one such example. Faceconnector pulls real-time Facebook profile and friend information into Salesforce. (Chapter 4, “Sales in the Facebook Era,” talks more about how this application is used). Designing this application the other way (pulling Salesforce information into Facebook) might not be the best idea because that could expose highly confidential customer data to all your Facebook friends.

Facebook for Websites (also known as Facebook Connect and Facebook Open Graph) is a technology that enables companies to integrate Facebook data, stream, and login information with their own Web sites and applications. Visitors to Web sites that have implemented Facebook for Websites can log in to the site with single sign-on, using their Facebook username and password. They can view which of their Facebook friends have also visited or interacted with the site, or are currently logged in. And when visitors engage with the site, such as posting a comment or photo, they can choose to share this activity with friends on Facebook via the news feed.

Today nearly 100,000 Web sites and devices have implemented Facebook for Websites, including these most popular and interesting examples:

• Eventbrite—People registering for events can see which of their Facebook friends are also planning to attend.

• Citysearch—Web site visitors can filter by restaurant and nightlife reviews written by friends.

• CNN The Forum—People watching the streaming video feed of President Obama’s inauguration on CNN.com could chat in real-time with their Facebook friends (see Figure 1.4).

• Xbox Live—Gamers can link their Facebook profile to their gamertag, update their Facebook status from within Xbox, and post gaming milestones to their Facebook news feed.

• Virgin Airlines—Flyers are able to see which Facebook friends are on the same flight and even send them a drink.

Figure 1.4

CNN.com’s live coverage of President Obama’s inauguration in January 2009, with Facebook for Websites social plugin (previously known as Facebook Connect and Facebook Open Graph) discussion widget

The major drawback of Facebook for Websites, of course, is that you become beholden to Facebook for interactions with and data about your Web site visitors. You are also giving Facebook visibility into these logins and interactions. This can be problematic for some companies that are accustomed to being able to capture and store more data about Web visitors, or that do not feel comfortable sharing site data with a third party such as Facebook.

But in many cases, the benefits of a frictionless login experience and vast distribution outweigh the inconvenience. There are five major components to Facebook for Websites:

• Single sign-on—You can can replace the registration process on your Web site with Facebook for Websites’ single sign-on feature. Once a user logs into your site with his or her Facebook account, you can access their account information from Facebook. They are logged into your site as long as they are logged into Facebook (and vice versa). Behind the scenes, Facebook Platform uses the OAuth 2.0 protocol standard for authorizing users.

• Social plugins—Social plugins are embeddable social features that can be easily integrated onto any Web site with a single line of HTML. These plugins are hosted by Facebook and are therefore automatically personalized for any user visiting your site who is logged into Facebook, even if the user has not yet signed up for your site. Examples include the Like button, which enables users to post and associate with pages on your Web site back to their Facebook profile with one click, as well as the activity feed plugin and recommendations plugin.

• Account registration data—Facebook for Websites also provides easy access to basic account registration data which you would typically need to request via a sign-up form on your Web site, including name, email address, profile picture, and birthday. By using Facebook instead of a Web form, you can more easily ask a user for all of this information within a single dialog box and no typing required.

• Server-side personalization—When you have implemented Facebook for Websites single sign-on, Facebook makes it easy to personalize the content and experience on your Web site to each user who visits, such as referring to a user’s friends when the user is on your site.

• Analytics—Facebook for Websites also provides detailed analytics about the demographics, sharing, and interactions of your users.

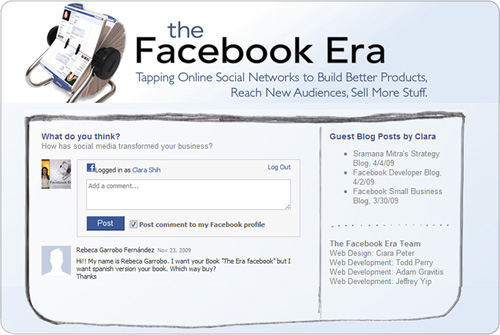

For example, when my friends and I built The Facebook Era Web site, we wanted to make it easy for people to interact with the site without having to sign up for yet another account. Implementing Facebook for Websites social plugins dramatically reduced the barrier to engagement for Web site visitors and still allowed me visibility into who was engaging with the content (see Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5

Facebook for Websites discussion widget on The Facebook Era Web site

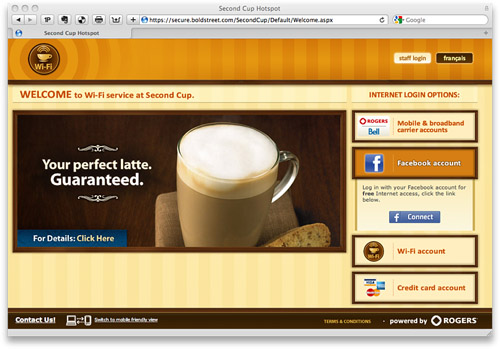

Even Second Cup, the largest coffee retailer in Canada, offers Facebook single sign-on as an authentication option to access free Wi-Fi in its stores (see Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6

Facebook for Websites single sign-on login option to access free Wi-Fi in a Second Cup coffee shop location

In the following guest expert sidebar, entrepreneur Gregg Spiridellis explains why he chose to implement Facebook single sign-on as the primary login mechanism for his popular site.

Why JibJab Connects to the Facebook for Websites

Gregg Spiridellis

JibJab was founded back in the digital dark ages—1999. Huddled around our blueberry iMacs, we put low-cost production software in the hands of great artists and set about distributing our work to a worldwide audience on the Web.

We had only email-based viral tools available back then, including the capability to send to a friend and sign up for our newsletter. It took us eight years to reach 1.5 million registered users. It took us only five months to achieve that milestone using Facebook single sign-on. How did we do it? We identified four ways to leverage Facebook’s data and tools to enhance our user experience:

1. Publishing—Facebook for Websites is the most powerful way to get your audience to share your content. Presenting users a list of their friends, as opposed to presenting an email form field, reduces the friction of having to remember email addresses.

2. Sign-on—We subordinated our direct registration system in favor of Facebook. Why? Because a Facebook for Websites user comes with an audience of 130 friends, whereas a directly registered user comes with zero.

3. Media access—JibJab’s Starring You product enables users to upload photos and put themselves and friends into personalized videos. Users previously needed to have a photo on their computer. Today users can access their own photos and also friends’ photos on Facebook from within our product. Less friction in finding the right photo of the right person leads to more engagement and makes for an awesome customer experience.

4. Data—Facebook for Websites offers a treasure trove of user data. The question you need to ask yourself is, which data enriches your product experience? At JibJab, the answer was easy: friends’birthdays. The ability to show users which of their friends is having a birthday is an opportunity for us to create user-specific intent which that greatly increases the likelihood that someone will send a card or become a customer.

Facebook for Websites does come with some risks, as is the case when you are dependent on someone else’s platform. When Facebook is slow, so are you. When it changes its APIs (which it does often) you have to divert engineering resources to maintaining products instead of building new products. For JibJab, the rewards of our Facebook for Websites integration have far outweighed these costs.

Gregg Spiridellis (@jibjab) is cofounder and CEO of JibJab Media.

A Promising New Era

We have come a long way since the heyday of mainframe computing, even since the early days of the Internet 15 years ago. On Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn, companies have many exciting new opportunities today to meaningfully engage with customers, prospects, partners, and employees in ways that simply weren’t possible before the social Web. Facebook applications and Facebook for Websites applications enrich Facebook Pages and company Web sites with rich functionality, social context, and easy ways to engage audiences.

The Web used to be isolated and anonymous. Now it is social and personalized. Facebook and other social networking sites seem to have figured out the Holy Grail every business has been seeking to replicate online with their customers—trust and engagement.

Once again, we are this decade at the cusp of a massive paradigm shift. We are moving from technology-centric applications to people-centric applications. We are improving the World Wide Web of information with a World Wide Web of people and relationships. The social Web is enabling a fundamentally new Web experience that enables us to bring our online identities and friends with us to whatever site or application we choose to visit on the Internet. It is the end of the anonymous Web, and it is already transforming the way we work, learn, and interact across every aspect of our lives.

![]() “The Facebook Era” refers not just to Facebook, but also Twitter, LinkedIn, MySpace, Renren in China, Mixi in Japan, Odnoklassniki in Russia, and hundreds of others around the world.

“The Facebook Era” refers not just to Facebook, but also Twitter, LinkedIn, MySpace, Renren in China, Mixi in Japan, Odnoklassniki in Russia, and hundreds of others around the world.

![]() In the Facebook Era, companies have no choice but to become transparent, responsive, and collaborative, or else risk going out of business.

In the Facebook Era, companies have no choice but to become transparent, responsive, and collaborative, or else risk going out of business.

![]() Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn enable us to use friends as “social filters” for navigating the incredible amount of content on the Web.

Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn enable us to use friends as “social filters” for navigating the incredible amount of content on the Web.

![]() Private social networks such as Ning might make sense when your site has a compelling enough offer that people are willing to create an account, you are able to drive substantial traffic to your site, or you purposely want to remain exclusive.

Private social networks such as Ning might make sense when your site has a compelling enough offer that people are willing to create an account, you are able to drive substantial traffic to your site, or you purposely want to remain exclusive.

![]() Facebook quickly differentiated itself from its predecessors by focusing on status updates and the user privacy model to build trust and engagement. Before you build a Facebook presence for your company, you need to build a Facebook presence for yourself and understand the dynamics of how people interact and engage on social networking sites.

Facebook quickly differentiated itself from its predecessors by focusing on status updates and the user privacy model to build trust and engagement. Before you build a Facebook presence for your company, you need to build a Facebook presence for yourself and understand the dynamics of how people interact and engage on social networking sites.

> > > TIPS and TODO’s

![]() Decide which social networks you will invest in building a presence on, based on not only where your current customers are, but also where your target prospects like to spend time.

Decide which social networks you will invest in building a presence on, based on not only where your current customers are, but also where your target prospects like to spend time.

![]() Study existing Facebook for Websites such as Citysearch, Live Nation, and Eventbrite to understand how the technology works.

Study existing Facebook for Websites such as Citysearch, Live Nation, and Eventbrite to understand how the technology works.

![]() Consider implementing Facebook for Websites on your own Web site (or a subset of your Web site) to increase user engagement and insights about your visitors.

Consider implementing Facebook for Websites on your own Web site (or a subset of your Web site) to increase user engagement and insights about your visitors.

![]() Think about how you can apply lessons learned from the Internet Era to the Facebook Era. For example, brainstorm with your team about what new Facebook and Twitter initiatives you can launch to take advantage of the unique capabilities of the social Web instead of just rehashing existing online efforts.

Think about how you can apply lessons learned from the Internet Era to the Facebook Era. For example, brainstorm with your team about what new Facebook and Twitter initiatives you can launch to take advantage of the unique capabilities of the social Web instead of just rehashing existing online efforts.

![]() Check out what applications are already available on Facebook (facebook.com/apps) and Twitter (oneforty.com) so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

Check out what applications are already available on Facebook (facebook.com/apps) and Twitter (oneforty.com) so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel.