2 Cameras: Tools of the Trade

So now that you’re shooting film, your doors are open to literally hundreds (if not more) of types of cameras to shoot with. No longer are you relegated to only a 35mm-based sensor digital SLR, whether it be Canon, Nikon, or one of the other digital SLR makers. Now you’re in a world where megapixels are not needed. You can shoot anything from 35mm to 8×10 cameras with the current films available. In the following pages, I will go over some of my favorite cameras and how I use them—and as an added bonus, some other photographers will weigh in on their favorites as well. There are so many cameras that I can’t talk about all of them, but I’ll touch on cameras that are useful and powerful imaging tools.

All film cameras function primarily the same way that digital cameras do, except instead of a CCD or CMOS sensor, there is a film chamber and film. They both have shutter and aperture control and ISO settings, but some film cameras can function entirely without a power source, such as a lithium ion battery. So, if you’re on a long trip and you don’t have access to a place to charge your batteries, you can still shoot. Most modern film cameras with matrix/evaluative metering and motor drives will require batteries, but in the film world there are cameras for everything.

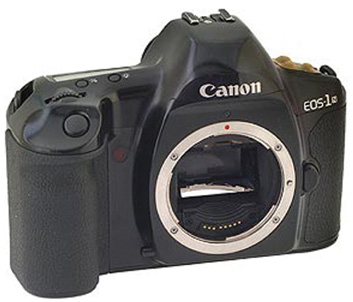

Canon EOS

My first SLR camera was a Canon Rebel G that I bought in 1999. It was my entry into the world of EOS, the Canon film system. With a huge selection of lenses, flashes, and cameras, the EOS system is just as powerful as Nikon when it comes to 35mm SLR shooting.

Since 1989, Canon has released many cameras, all autofocus and very reliable.

Canon 1V

This camera is the top of the line of film cameras for Canon. It was the last pro film camera released by Canon before they went all digital. I shot this camera many times, and it never failed me. With 45 autofocus points, a super-fast motor drive, and selective metering patterns from spot to matrix, I never missed a shot.

Canon 1N

Before the 1V there was the 1N—a mighty camera in its own right and very fast. Lighter than the 1V and just a bit smaller, the 1N still has all the same functions. However, instead of the 45-point auto-focus, it has 5.

Both the 1N and the 1V run on regular AA batteries and can shoot many rolls before you have to replace them. Both have TTL (through the lens) metering for flash, with the 1V having E-TTL (a more advanced version of the metering system). I would recommend either camera to anyone wanting to shoot fast and with a pro-level body. The 1V costs more—maybe even double—but it’s not twice as good as the 1N. Both take awesome shots.

“My first SLR camera was a Canon Rebel G that I bought in 1999.”

Images taken with my Canon 1V.

A cheaper way to get into the EOS system is with a non-pro body, such as the Elan II or Elan 7. I think the Elan 7 is a great camera, with insanely fast autofocus and almost every feature that the 1V has, save for the weather-proofing and motor drive. I used the Elan 7 for years as a newspaper photographer and also took it on many international trips. It never failed me.

“I used the Elan 7 for years as a newspaper photographer and also took it on many international trips. It never failed me.”

The Canon Elan 7.

I took these photos with my Elan 7 with a Tokina 80–200mm f/2.8 while in the Dominican Republic. I shot on Kodak slide film. The camera’s meter never failed me, and the autofocus let me take these shots from the backseat of a moving Jeep as we drove through a sugarcane plantation. There was no way for me to manually meter and focus everything when we were moving at such a high speed, and the light was so different everywhere that I had to rely on the camera in Shutter Priority mode with the metering set to matrix.

Canon EOS-3

There is also the EOS-3. It’s a powerhouse and a pro camera in a small package. The EOS-3 has 45-point autofocus and all the bells and whistles of the 1V. I’ve never used this camera myself, but many people swear by it. For its price, it’s supposed to be a great camera.

The Canon EOS-3.

Ingrid’s Turn

I shoot all my weddings with the EOS-3. It’s a great professional camera that is quick and user friendly. I have four bodies, which you can buy used pretty cheaply nowadays.

Canon Lenses

Canon lenses are nothing to ever think twice about. Canon has some of the fastest and sharpest lenses I have ever used. If you read my previous book, Fearless Photographer: Weddings (Course Technology PTR, 2010), you know that I primarily shot all my weddings with just two lenses: the 35mm f/1.4 and the 85mm f/1.2. These lenses did everything I needed and allowed me to rock whatever I was shooting. Everything from Canon’s prime lenses to their amazing zooms is top-notch.

“Canon has some of the fastest and sharpest lenses I have ever used.”

In my mind, these are two of the best lenses ever manufactured for SLR cameras. With blazing autofocus and full-time manual control and sharpness across their aperture spectrum, they are great tools.

The Nikon System

I am a convert. I can’t lie. I have used only Canon cameras since the 1990s. But when I went back to film, I switched over to Nikon. I did this for one main reason: I wanted to use a system that would let me shoot film in bulk loads so that I could shoot on motion-picture films. Canon and other manufactures do offer bulk-load cameras, but none of them took modern lenses or had autofocus, so Nikon got my vote.

With Nikon, you can pretty much use any lens on any camera ever made in their system. I could use an older film camera with modern autofocus lenses and interchange them with modern autofocus cameras, such as my F5.

I was sold.

I currently shoot with a Nikon F3 and a Nikon F5. My F3 has the MZ-4 250 bulk pack that lets me shoot rolls of 250 shots instead of the normal 36-exposure rolls. It’s a big camera, and I have to load the film cassettes for it in a darkroom. The F3, like every other F camera in the Nikon system, is a pro camera with parts built to last and to be interchanged. I have customized the camera to make it work best for me, with an HP (High Point, for eyeglass-wearers) prism, a non-split prism focus screen, and the MD-4 motor drive. I love shooting on it. It may not have autofocus and all the metering options of my F5, but I’ve never missed a shot with it.

My F5, on the other hand, is a different breed of camera. Born in the autofocus age, it’s the smartest and fastest camera I have ever used. The motor drive can rip through a roll of film in seconds, and its focus tracking is spot-on. It has some of the most advanced matrix metering I have ever used, but what I love most about it is the TTL flash metering with D-type lenses. It’s always perfect. Yes, part of this is because film has great latitude, but I know the camera and flash are doing most of the work.

“With Nikon, you can pretty much use any lens on any camera ever made in their system.”

A Nikon F3 with a 250 bulk pack and a Nikon F5.

I use these two cameras 90 percent of the time. They aren’t necessarily the best or the only Nikon cameras out there, but they’re what I use and find to be excellent products.

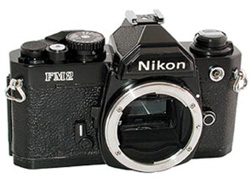

Other awesome Nikon film cameras include the F2, F4, F6, N90, F100, and FM2—the list goes on and on.

If you’re just starting out and want something cheap but awesome, look at the N90. I bought my assistant one for $59 at www.keh.com (the best place to find film gear), and it’s a great camera. Quick autofocus, a built-in motor drive, metering modes—it’s a pro camera.

More excellent Nikon film cameras.

At a recent camera tradeshow, I was able to play with a Nikon FE. It’s a small, light, fast manual-focus camera. It is now on my list to get. This camera was made to carry with you and street-shoot. My 85mm lens may be bigger than it, but the camera is still 35mm and accurate.

Flashes

Because you’re shooting with film cameras, you won’t need the new super-expensive Speedlights that fire a pre-flash to determine exposure for digital images. You can use almost any flash Nikon has ever made on pretty much any film body. (The exception is the newest flashes that are digital only.) I use the SB-80DX flash because it is small and powerful and offers manual control and wireless flash control. I can have my on-camera flash control my off-camera flash, which I can set up where I need it.

Lenses

With Nikon, I can use almost any lens ever made for Nikon—film or digital era, autofocus or manual focus. The lens mounts are universal. The only lenses that can’t be used on some of the bodies are the newer, more cheaply made G lenses. These lenses don’t have an aperture ring, so they can’t be used on bodies that don’t have digital aperture control, such as on the F5, F100, and newer autofocus bodies. But it’s really not a problem, because there are more non-G lenses than there are G lenses.

My favorite Nikon lens is the 85mm f/1.4. It may not be as fast as the Canon 85mm f/1.2 in terms of aperture speed, but it blows the Canon out of the water in terms of autofocus. When I’m shooting in low light and shooting moving subjects, the autofocus counts.

My favorite Nikon lens—the 85mm f/1.4

645 and 6×7

My camera bag contains many cameras, usually one of which is a medium-format camera, such as the Pentax 645 or 6×7. Medium format offers a much larger negative than standard 35mm. The image size of a normal 35mm image is 24×36mm, whereas 645 is 56×42mm and 6×7 is 56×72mm—that’s more than double the image size. So what does that mean? It means that more image detail is being recorded, along with less grain and a shallower depth of field. Think of it this way: If you took a 35mm image on ISO 400 film and had the same shot with the same film taken on 645, and then you printed both images to an 8×10, the image taken with the 645 would be sharper and would have less grain.

By the same token, with a larger film plane, you will have shallower depth of field to that of the same aperture, lens, and distance to subject on 35mm. So, if you had an 80mm lens at f/2.8 on a 35mm body, and next to it you had a 645 camera with an 80mm lens at f/2.8, the depth of field would be greater in the 35mm frame than in the 645 frame.

The area of viewing is also about 50 percent compared to a 35mm lens, meaning an 80mm 645 lens gives you about the same view as a 45mm lens on a 35mm camera.

There are many, many 645 cameras, ranging from top-of-the-line autofocus bodies, such as the Contax 645 series, to more stealthy and smaller rangefinder models (with no mirror box, so they are smaller and lighter than SLR bodies, such as the Pentax or Contax 645), such as the Mamiya 6 and 7. These cameras take incredible images that you can blow up to billboard-size prints if needed.

I haven’t had the chance to use as many 645 and 6×7 cameras as I would like; to be honest, they cost a lot! I would love to own the Mamiya 7—it’s super-light and has manual focus with great metering and quick action. I’ve had the chance to use it at tradeshows, and it’s just a perfect lightweight, high-quality camera.

The Pentax 6×7 and Pentax 645.

The Contax 645 and the Mamiya 6.

“I would love to own the Mamiya 7.”

The Mamiya 6 and 7 are both super-light rangefinders. I’ve been dying to own one for many years, but I ended up in the Pentax system. The Mamiya system is fast, light, and very customizable. The camera fits well in your hand, and because it’s a rangefinder, there is no mirror slap. The meters on the both cameras are accurate as well. I personally still like to meter with my handheld Sekonic, but with a little time I’m sure I could learn the ways these cameras meter and mold it to my style.

There are many more medium-format cameras available—too many to talk about in this book. Just take a look online, and you’ll find the one that works best for you. The ones I have just written about are some of my favorites.

NOFEAR

Just shoot. Don’t be afraid.

Leica

To some, there is only one real camera: the Leica. Strong, well-built, fast, and small, it’s one of the most sought-after and dreamed-about cameras for many photographers. It’s also very expensive. With some of the fastest lenses ever made, such as the 50mm f/0.95 lens (which runs $10,000), it’s a true professional camera system. With rangefinder focusing and bodies with TTL and non-TTL metering, there’s pretty much a camera for everyone. I’m more of an SLR type of guy, and I never really got into the Leica system (plus, I love big cameras), but the Leica system—from the M4 to the M7—has truly awesome cameras. These cameras don’t need batteries or power of any kind (unless you want to power the meter in the newer models) and will keep working no matter how far away the next battery store is.

“To some, there is only one real camera: the Leica.”

Leica makes excellent cameras.

The XPan

This Hasselblad is one of my personal favorite cameras. I drooled about owning one before I got it. The Xpan is a unique rangefinder camera. It allows you to take panoramic images across the space of two normal 35mm frames, so you get double the detail. On a 36-exposure roll, you would get 18 shots. I love the perfect straight framing of this lens and the cinematic look I achieve with it—very much like the super widescreen movies you see with a 2:35:1 ratio, a very wide view. It also allows you to switch back to standard 35mm frames with the flip of a switch.

The Xpan is a rangefinder camera.

The camera focus is not as fast as most rangefinders and not the best for action. I’ve tracked subjects with it, but it takes some practice. The XPan runs on batteries and needs them to power the motor drive, as there is no manual advance. To be honest, I wish there was—this camera sucks batteries dry after a few rolls. I always have this camera or my Lomo swing-lens camera with me. There is no digital camera with a panoramic-sized sensor that is equal to the frame size of the XPan. There are cameras that stich images together as you pan, and there is software that lets you stich photos together, but none can capture a panoramic in one single shutter click

Images of New York City taken with my XPan.

The Horizon Perfekt

The Horizon Perfekt is a fun and truly amazing panoramic camera from the USSR. Made in Kiev, Ukraine, this Soviet-era camera is now sold in the United States by Lomography. This is one of the most wicked cameras ever made. It takes no batteries, doesn’t meter, and is all manually controlled.

What makes this 35mm camera even more amazing is how it takes panoramic images. It has a swing lens. The lens rotates in a splash of a second from left to right, exposing a frame and a half-size image, yielding about 23 to 24 frames on a 36-exposure roll. The swing lens creates a unique, almost curved world because of the lens’ rotation. If you’re not holding the camera level, you’ll get a very fisheye look to your images. I love this camera and try not to hold it level—otherwise, I’d just shoot with my XPan all the time. I love the unique look that I get from the Perfekt.

The camera doesn’t really look like a camera, so it’s great for street shots or for places where you don’t want to be seen with a camera and you want to be more discreet. With its 28mm f/2.8 lens, you can easily take shots from your hip and just fire it off and capture unsuspecting life around you. It’s great for city shooting.

Images shot with my Horizon Perfekt.

“I love the unique look that I get from the Perfekt.”

Lomography

Lomography is a society and a company. They sell film cameras of all shapes and sizes, and they have a site where users can share their work and talk tips and ideas. It’s a great place to look for some cool cameras and to learn about doing some neat camera tricks.

The Horizon Perfekt.

Spinner 360

The Spinner 360 is a new addition to my camera bag—and to the camera world, for that matter. Released in the fall of 2010 by Lomography, this camera is something that no one else has. It features 360-degree image capture. With two settings—f/11 and f/16—and a ripcord, there are no settings or focus controls to play with. You simply hold out the camera, pull the cord, and let ’er rip. Presto—the camera spins around, and you have an endless panoramic.

This camera doesn’t need batteries—just a roll of film and lots of sunshine. Not a camera for night shooting or dark days, the Spinner 360 is best used with 400 or above film and lots of light with its f/11 or f/16 setting.

Scanning the images is a bit more challenging. Most labs can’t scan the images with your normal film, so you either have to pay the lab to scan the images a frame at a time on a flatbed or do it yourself. Lomography also offers mail-in processing and scanning for the Spinner 360, and that’s probably your best bet unless you want to scan the long frames yourself.

Oh yeah—this camera exposes the sprocket holes, too! (Sprockets are the “teeth” that grip the holes on both sides of a roll of film to advance it through the camera.)

The Spinner 360.

“You simply hold out the camera, pull the cord, and let ’er rip.”

You pull the string, and whip! The camera spins 360 degrees and gets everything around you in the shot.

Canonet QL17

“I call this camera a poor man’s Leica because it’s about the same size and about one tenth (or less) of the price.”

This is a tiny Canon rangefinder from the 1970s. The QL stands for quick loading, and this camera does load fast. Simply pull the leader through the film take-up reel, close the film back, advance about three times, and the camera is ready to go. I call this camera a poor man’s Leica because it’s about the same size and about one tenth (or less) of the price.

To be sure, this camera is nowhere near as good as a Leica, but it still takes great photos and is small, light, fully manual, and sharp. With a 40mm f/1.7 lens made of rare earth glass, I can use this camera in low light and get great shots. The lens has nowhere near the quality of today’s new lens optics, but I like the magical look it gives me as it renders things. The QL17 is a low-fi camera that will create very unique-looking photos. I highly recommend it if you like the Lomo look.

I often find myself taking the QL17 out for just fun trips, when I don’t want to carry my F5 or F3 with me. I can toss this camera in my glove box, and it fits fine. I love it.

The Canonet QL17.

Images shot with my Canonet QL17.

Plastic cameras have become very popular over the past few years because of websites such as Lomography.com and because of social media sites and blogs dedicated to the toy camera movement. The great fun with toy cameras is that they are relatively cheap, lightweight, and fun to shoot with. They give a very distinct look because of the simple plastic lenses. Many describe the photos as dreamlike or vintage because the focus tends to be a bit soft and have a vignette.

A few popular cameras that I have personally shot with include the Holga 120mm, the Holga 35mm, and the Diana Mini. I tend to do more with the 35mm cameras, because I always have plenty of that film lying around. The cameras are small enough to fit in a purse and so lightweight that you can put one around your neck and barely notice it’s there. This encourages you to have one with you at all times and play with it. It’s a true toy camera.

The Diana Mini allows you to shoot single frame or half frame, turning a regular 36-exposure roll into a possible 72-exposure roll with the flick of a switch. You can blend the images or push the film to advance more to create a dividing line, depending on what you are looking for. Like other toy cameras, the Diana Mini allows you to choose a sun setting or a cloud setting for exposure and select the focal distance. It’s meant to be used with 100 ISO film in daylight or on an overcast day, but you can easily use 400 ISO color negative film because of the wide exposure latitude and get great results, even under darker conditions. There is also a bulb setting for longer exposures, should you want that.

Large Format

With film, you’re not limited to sensor size. Film can be cut to almost any size. 35mm is great, and medium format is awesome, but if you want even bigger images, you need to shoot 4×5 or 8×10. These truly massive cameras take photos that will wow you with the limited depth of field and the intense detail rendered from the large negative.

I’ve never shot these cameras myself, as I find them too big and bulky for my kind of wedding and fashion work, but I have many friends who use them, and they produce some truly amazing images. If you want to get the best image possible and you don’t mind spending a lot of time getting your camera in position, locked down, and focused for a shot, then large format is the way to go.

Despite all the effort and time you will put into using a view camera, the results will be unlike anything else you can produce photographically and well worth the investment

A 4×5 camera.

“These truly massive cameras take photos that will wow you with the limited depth of field and the intense detail rendered from the large negative.”

Barry S. Kaplan on Large-Format Shooting

A tripod; a dark cloth covering the back of a toaster-sized box made of metal, leather, and glass; two legs; and a bent-over human descended from this odd shape, perhaps with one or both arms reaching around to the front. That was state-of-the-art photography in the 19th century, and for some it remains the highest form of photographic capture today.

The view camera in its basic state evolved from the camera obscura, the dark box of Alhazen and Niépce. When light-sensitive coatings were applied to metal, glass, and eventually film and inserted in the path of the light coming through the other end of the box, an image could be recorded and saved for others to see. To refine the quality of the image, lenses of glass and shutters with variable apertures and timers were placed into the front panel (standard) of the box. A light, tight, spring-loaded slot in the rear standard was made to securely hold the film during lengthy exposures. Film emulsions were slow, and subjects had to hold still for many seconds to prevent their likeness from being blurred. A simple but bulky mechanism was born that most people today would consider primitive in its lack of anything automatic. There was no meter to measure the light, no focus except looking through the ground glass on the back of the camera directly out through the lens, and only one shot of film at a time—and that had to be prepared carefully in total darkness. Why would anyone bother spending the time and effort to take one picture? In a word, f/64. And in other words, control of perspective, capture of detail, and ability to control the range of contrast and exposure on a sheet-by-sheet basis (Ansel Adams’ Zone System), all to present the viewer with a sense of being there.

Using all the options available to him, the large-format photographer can present us with a view of the world beyond what our eyes and brain might have seen and processed in person. And the photographer is rewarded too, because in the process of choosing where and when to use this camera, there comes a necessary patient creativity, which is satisfying in and of itself before the shutter is ever released.

Large-format cameras are designed to use sheets of film or digital scanning backs from 4×5 inches to 8×10 inches. Larger formats are made for special purposes, but the 4×5 is the most typical format and the easiest to find film for.

The studio version of such a camera has all the controls to tilt the front and back standards, shift these standards up and down, and swing the standards around their central pivot point. All of these movements can help adjust for off-plane perspectives, place the image precisely on the film, and control focus and depth of field, or acceptable focus. The science behind how the light rays are bent is based on the Scheimpflug principle.

The field version has limited controls because it is designed to fold into itself for portability and light weight. Press photographers of the mid 20th century used a popular field camera made by the Graflex company. The large film size meant that contact prints could be made quickly and easily in a darkroom without the need for enlarging, a must for the fast pace of news photography in those days. Beautifully made field cameras of wood and brass with finely made controls are prized for their looks and utility.

Lenses are mounted to boards that are inserted into the front standard and held in place with sliding clips. A wide variety of wide-angle to telephoto lenses are available, and you can experiment with mounting a lens designed for a different type of camera or application with creative or satisfactory results. Most lenses have shutters built in, and as with any lens, the sharpest, best-designed ones are highly prized and hold their value.

Due to the size of the film and the need to bring a large image circle through the lens to cover the entire face of the film, these lenses are large, heavy, and not able to be designed with relatively wide apertures, compared to their small-format cousins. The result is that it takes a much smaller aperture to achieve a large depth of field than it does with smaller cameras that use 35mm or even 120 film. So while it may be common to see possible apertures of f/45 or f/64 on a lens barrel, in practice it will require a fairly long exposure and a stable tripod to use these settings to maximum advantage.

Most film types are available, including the new Kodak 10 sheets. Some films are prepackaged so you don’t need to load individual holders, but these may be limited in choice and supply. There are also 4×5 backs that hold medium-format rolls of film for the dual convenience of having multiple shots on a roll and the use of the camera controls. A smaller film size will also have the effect of enlarging the apparent focal length of the lens (for better or worse), as the image circle will then cover far more than the size of the film. There are still some instant films that provide very good ways to check exposure and some that have their own artistic look and feel. These require a film holder made specifically for them by Polaroid or Fuji.

Joe has given quite a bit of information on each of the individual systems. If you’re just starting to get back into film shooting, you should ask yourself several questions before you buy. It’s also a good idea to rent a few different cameras to see what suits you best.

Choosing equipment can be a very personal decision. What feels good in your hand? Do you like to hold the camera up to your eye, or do you see things differently when you look down into a waist-level viewfinder? Do you like a lightweight camera, or do you want to feel something sturdy and powerful? Maybe you prefer a square format or the more common rectangle. Are you a quick shooter or methodical? Some will randomly choose a system, get to know and master it, and never switch. Others go through cameras like underwear and buy and sell bodies on eBay every other day. Who are you? And what tools will allow your vision to materialize?

Getting to know your equipment is key to being a good photographer because you really want the tool to be an extension of your mind and eye. You don’t want to fuss with thinking too much about technical information when you’re in the moment. You should know what to do intuitively and just let your fingers find the correct shutter and aperture.

You might have different cameras for different assignments. I personally like to use my EOS 3 cameras for 95 percent of my work with weddings and children. The quick, light 35mm cameras are great choices for the quickly changing conditions of a wedding or chasing down toddlers. I like to shoot instant film when I’m with friends because its immediate results allow for fun participation. I like to shoot my heavier Mamiya RZ67 camera when doing more planned, conceptual, or portrait work. And I take my plastic Diana Mini with me everywhere.

I shot the image on the left with my EOS 3 and the image on the right with my Mamiya RZ67.