1 Welcome to Film Land

Some 15 years ago, I picked up my first real camera and started shooting. I was a teenager in middle school. It was a Canonet 28, a cool camera from the 1970s that was mass-produced as a quick and easy camera to use. It had a built in meter, but more importantly, it was fully manual. For the first time, I could focus on what I wanted and not have the camera choose for me—as is the case with point-and-shoots. I took this camera everywhere I went, and soon I wanted more.

Why Film?

I moved up to a Canon Rebel G after seeing my high school instructors use it on field trips. Moving up from a 1970s rangefinder camera to a modern autofocus SLR was a huge jump for me. Soon I was shooting film by the caseload. I would go to Costco or Sam’s Club and buy the film in the 10- and 20-packs they sold, shoot it, bring it back, and get prints made. At that time, I was shooting almost 10 rolls per week—learning, trying new things, and always looking at my prints to see what I was doing wrong and what I was doing right.

SLR versus Rangefinder

On an SLR (Single Lens Reflex) camera, when you look through the viewfinder, you see through the lens of the camera, and you see exactly what will be recorded on your negative. This is done through a mirror in the camera that reflects the light coming through the lens to your eye. A rangefinder, on the other hand, doesn’t have this mirror. You look through a viewfinder that doesn’t reflect exactly what your lens is seeing. The viewfinder usually has bright lines to show you what your lens is seeing and marking to correct for the parallax, or spacing between the viewfinder image and what the lens is really seeing. Rangefinders are generally smaller and lighter than SLR cameras and can be shot handheld at slower shutter speeds, because there is no vibration from the camera’s mirror flipping to let light pass to the shutter.

“This was slide film. It blew my mind.”

Gradually, I wanted to shoot more and more slide film and less negative film. This way, I could share my work with more people in the form of slideshows. With negative film, I got back negatives, but you couldn’t really see the actual image in a negative because it was, well, negative! Slide film, on the other hand, produced a positive image, so people could look right at the frame and see the image. I could mount the frame in a slide case and show it on a projector to a large audience. I was sold.

I joined a local camera club and was soon bombarded weekly with amazing travel images, landscapes, and stories from mostly retired folks who were traveling the world and shooting the amazing things they saw. Seeing the national parks on huge 50-foot screens in total darkness just amazed me. You were there at the parks, among the trees, in the snow. You were there. This was slide film. It blew my mind.

From that point on, I was shooting slide film, buying it in bulk at Costco and Sam’s Club, and putting together my portfolio. I must have shot thousands upon thousands of slides, each time trying something new or seeing how I could shoot better. At the time, National Geographic was all slide film, and that was a huge inspiration for me. Seeing what photography was all about and getting the image right the first time, in camera, was what I was after. After all, digital correction was not available at the time for the public, just in high-budget movies and magazines. Besides, slide film offered instant gratification. I could just look at my image frame, hold it up to a light or place it on a light box, and see the image. I didn’t have to print it to see what the color and contrast looked like. I could see what all my shots looked like right away.

“Slide film offered instant gratification.”

This shot is a flower outside my house after a rainy night, shot with Fuji Velvia. I love the way Velvia captures color and detail. Velvia is an ultra-saturated film; it’s high contrast and great for producing vivid images with little to no grain. I wouldn’t shoot people with this film, because it could make them a bit orange depending on their skin color, but it’s the best for nature!

When I went out to shoot, I didn’t generally go to national parks and such. I was in Boston and limited to where my family went on vacation or my school took me. Hence, my slide photos are not national park images—but they’re still fun!

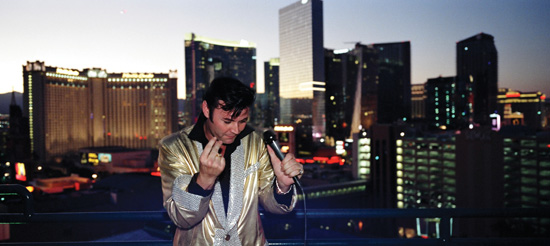

This was shot on Ektachrome 100VS (vivid and saturated). I was hiking around Red Rock Canyon, and I wanted a film that would capture the awesome color and details I was seeing so I could do a slideshow when I got back home. I love the way this film makes the sky so blue—just how it looked with my sunglasses on.

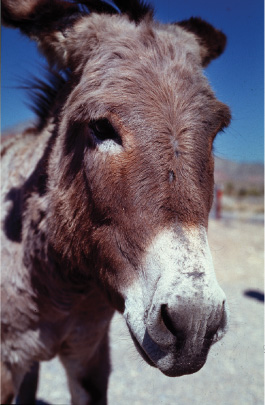

On the same hike in Red Rock Canyon, I encountered some wild burros. Just look at the color and the detail of his hair in the midday sun! Love it.

Don’t be afraid to shoot film. Yes, there’s no LCD to see what you just shot, but trust me—you’ll live.

Around 1999, I got offered a job shooting for a local newspaper. The newspaper was all about color and required that I shoot color negatives they could process and scan in about an hour. Slide film had to be sent out; the paper didn’t have the equipment available for me to shoot assignments on it, so I was back to shooting color negatives. I was given rolls of film and sent out all over. Little League games, murder trials, political debates—I was at them all with a bag full of film. Here, I was first introduced to what has now been coined the hybrid workflow. After getting the negatives back from the lab, we would look at them on a light box, the editors would pick what they wanted (even though they couldn’t see the real image, they looked for focus and shape), and then the negatives would be scanned to JPEGs on a Nikon CoolScan.

At the time, the newspaper was being digitally designed with QuarkXPress, so they needed digital files to lay out in the paper. At the time, digital cameras cost about $25,000, had about 2-megapixel resolution, and didn’t shoot well in low light.

Pro Film versus Consumer Film

Pro films are lower contrast and finer grained but are consistent for a certain time. They need to be refrigerated, and they have an expiration date. Consumer films are generally higher contrast and produce more vivid prints. They don’t have to be refrigerated, and they have a longer shelf life. However, if you were to shoot a few rolls of consumer film and compare the images, they all might be a little different, whereas images shot on pro film should look the same.

(Facing page) I was shooting the Charles Regatta on an overcast day. I must’ve shot 10 rolls or more of men and women racing, but then I saw this man coming down the river by himself. It was my favorite shot of the day. This was shot on Ektachrome 100, low saturation and low contrast. It’s not that great in low light, but it’s all I had with me that day.

When I was a newspaper shooter, I got to cover many cool events. This image is from the opening games of women’s major league soccer, featuring the Boston Breakers. I was sent to cover the event because local kids from the Revere Youth League went to cheer them on, and I got a cool story. This shot was taken with a 300mm lens on my Canon Elan IIe on Fujicolor Press 800 film, at about 1/250 at f/2.8. I clearly remember seeing photographers from the Associated Press shooting on some of the new Kodak hybrid digital cameras (which cost $25,000 at the time), and I wonder where their photos are now—probably on a floppy disk somewhere!

These images from 2001, shot on Kodak Royal Gold 100, were taken on my Canon Elan IIe as well. I was assigned to shoot a Native American festival in one of the town parks. It was noontime and direct light, but the film captures all the details of the image without blowing out any highlight details, and it still retains awesome shadow details. Because it was shot on consumer film, this image has slightly higher contrast then pro film would, but it looks awesome nonetheless.

These images were shot on Fuji Pro 160 film at the 2001 Boston Marathon. It was a cloudy day and the light was very flat, which I thought was perfect to show these runners in their best form. I positioned myself near the end of the race, hoping to get images of the runners in their most tired state, yearning for that finish line. I shot these images with my Canon 300mm f/2.8, on my Canon Elan 7. Once again, the film captured great detail in both the subject’s shadow and highlight areas. There is great range from shadow area to the direct-sun areas. If I’d shot digital, the highlights would have been blown out, and the color and details would’ve been lost.

This image was shot on Fujicolor Press 800 in about 2001, when I was assigned to shoot a local boxer fighting. This was a major victory for him, and I shot it with just ambient light. I love how the film captures good contrast and color throughout the image, even under television lights. I used a Tokina 20mm–35mm lens at f/2.8.

Another example of film’s ability to take beautiful images in the harshest light. This was taken during a local fireworks display on Revere Beach. I had my camera on a tripod loaded with 400 speed film. I just set the camera to bulb mode and f/16 and let the shutter stay open while the fireworks exploded overhead. The film recorded the explosions and the people in the foreground without loss of details. The ground is cast in green due to the city lights, which must have been some type of fluorescent bulbs.

“In essence, my hours tripled for the same pay.”

Film was the only option until about 2003, when Canon and Nikon both released dSLR pro bodies that cost less than $5,000. The newspaper jumped at this. No more lab bills! The newspaper I worked for (and most around the country) bought (or had their photographers buy) digital bodies and then sent them out in the field. After that, we were required to shoot more and spend hours on the computer sorting and color-correcting the images to the newspaper specs. A once simple job of shooting and dropping off the negatives now became a nightmare. I had to sit at a laptop for hours and edit and adjust images. At the time, digital cameras still didn’t do well in low light or with flash—the images just looked bad, grainy and muddy. We started using Photoshop actions and noise-removal applications to make the images better, so that the paper could save money by not paying for film or a lab bill. In essence, my hours tripled for the same pay.

Eventually I got laid off, as did many photographers around the country. Digital online news was killing the newspaper industry. I actually didn’t care at that point; I had lost my love for the industry long before. But that’s another story....

At that point, I was 100-percent digital and shooting weddings to pay my bills. I sold all my film gear and was now at the mercy of Photoshop. It’s lucky that I love weddings, because from 2004 to 2009, that’s all I did. All on Canon digital cameras. How many hours of my life did I spend editing all those Raw images? Each wedding had me at my computer for about 10 hours, editing away in Aperture. And every time I got a new camera, I had to upgrade my computer to handle the new Raw format or the larger file size. It was a vicious cycle. I longed for the days of shooting and just getting prints back, but I nearly forgot what it was like to be a film shooter and just accepted things for what they were.

That all changed in early 2009, when people started talking about film again. I heard about this thing called Lomography in New York City and a new film from Kodak called Ektar 100. Many people were whispering about film; it was an underground movement, and members didn’t want others to know that they were starting to shoot it. Well, okay, that’s a bit of an overstatement—but it felt that clandestine!

“I longed for the days of shooting and just getting prints back...”

I picked up a few rolls of the Ektar and fell in love instantly. I started shooting it for myself. I even picked up a Russian panoramic camera from the Lomography store in New York City and started shooting my trips all on film. I would shoot, drop off the film at the lab, and get high-resolution scans of my images back on a disc with the negatives, and only sometimes prints. I was blown away when I opened the files. The color, the look, no Photoshop needed—these images were good to go.

Photo from trips shot on my Horizon Perfekt.

I started bringing my film cameras to weddings. I wanted to see how weddings would look on film, because at that point I had only professionally shot weddings on digital. I shot film at weddings years before, but that was long before digital, so I needed to compare my results.

I was blown away. Every frame was amazing. Black-and-white, color—it made no difference. I was getting the shot, the image was captured, and the exposures were perfect. With digital I had to shoot like slide film—there was no room for error. You blow the highlights, and you’re done—they’re gone. With negative film, the highlights were there, as were the shadow details. The negative is like a super Raw format—it captures the light and records it. There are no compression algorithms or loss of data, just a chemical recording of what you captured. It’s analog, and I was sold. I slowly traded in my digital gear, and by the summer of 2010, I was shooting 100 percent film. I would shoot, drop off the film at the lab, and get back awesome scans. All I had to do was sort them and put them online. I had more time to blog and market myself—and to live my life.

“I was blown away. Every frame was amazing.”

These tests are by the Brothers Wright studio in LA. ©Brothers Wright. The image shows highlights and shadows on digital (Nikon D300) versus film (Fuji 645 with Fuji Reala 100 film). The first test (this page) shows normal exposure, and the second and third images (next page) show two stops over and two stops under, respectively. Notice the sky and the loss of the highlight detail in the digital images, whereas with film the sky, highlights, and subject are all exposed nicely. Thank you to the Brothers Wright for these images.

“Film reopened my eyes and allowed me the freedom to be more creative in what I was doing.”

I also wasn’t limited to just shooting the 35mm format size or restricted to just Canon or Nikon. I now had an entire world of cameras and formats open to me. Film reopened my eyes and allowed me the freedom to be more creative in what I was doing.

NOFEAR

Don’t be afraid to use a camera you’ve never heard of or are unfamiliar with. You don’t need to stick with Nikon or Canon. There are many film cameras from the past 50+ years that rock!

Since then, Kodak has released new films, which I will cover in depth in later chapters, that have given film a new life and have pretty much blown away what 90 percent of digital cameras (and Photoshop) can do. The dynamic range of film—its ability to be properly exposed and let you capture an image even if your exposure is way off—is what makes it special to me.

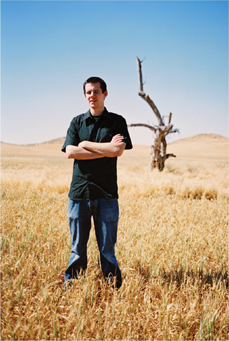

I recently shot this image at 1/60 and f/2.8 on ISO 160 film. The subject was in the shade under a deck; behind him was the beach in full sunlight, which was about 1/100 at f/16. When I went to scan the negative, I realized that all the detail was there—the beach to the subject at f/2.8. That’s five stops. Try that on your digital camera!

I’d like to add another viewpoint to the “Why film?” question. I, too, have been shooting film for a very long time. I got my first film camera when I was 10 years old. It was a little red point-and-shoot. I have no idea who made it or what became of it, but I do have memories of taking photos with it, sending the film away to be developed, and waiting impatiently for it to come back in print form. And that is the main reason why I still shoot film today. Yes, I agree with all the technical and time-saving aspects that Joe pointed out earlier, but for me, the magic of film will always remain in that anticipatory aspect of not knowing exactly what you’ve got until the images are developed. The whole of photography for me is in the waiting. You wait for moments to unfold before your eyes, the film waits for light to hit it through shutter and aperture, and the exposed film waits for chemicals to bring it to life. None of that chemistry happens with pixels. Anticipation and mystery become part of the art form itself.

Some may argue that as a professional photographer, you should want to be 100 percent sure for your clients, but I have to say that shooting film actually strengthens my abilities to see what is happening before me and not on a little LCD screen. Your shooting approach changes when you shoot film. There is no checking on the back of your camera; there is only looking at your scene and your subjects through your viewfinder. Over the years, this has made me very attuned to the subtle moments and the quickness of passing time. It encourages you to slow down to capture something that happens very quickly. It forces you to become a better observer.

Event photographers are often hired to record people’s personal histories. I like how film has a permanence of taking these moments and freezing them onto a strip of film. I have seen many digital photographers delete files moments after they’ve taken them, either to free up space or because they saw that the image wasn’t perfect. This actually changes your perception of history. With film, you tend to get the perfect moments alongside a set of outtakes. In 20 years or so, what will we look back to? A history with no closed eyes, no human errors? I love how film holds onto that instant of truth with a little more tenacity. Yes, all photography is subject to interpretation and perception, but film seems to hold a bit more authenticity in the long run. (There will be an assignment at the end of this book that urges you to shoot one roll of film over the course of a day—print that contact sheet, and you’ll see what I mean.)

Candid moments captured on film.

Film also pushes you to be a little more watchful and practiced due to the cost. Unlike a digital shooter, who can basically keep a finger on the shutter button in rapid fire, we film shooters have to capture the moments with a human eye and one click. Each time we press the shutter release, we know there will be a small cost. It makes you care about each individual shot, and if you don’t know your film, your equipment, and your lighting, your photos won’t come out on a consistent basis.

So why film? Use it because it will give you magic and make you a better visual spectator.

Digital and Film Differences

“If you like the way film looks as prints, then shoot film.”

I’m not a scientist or a numbers guy. I can’t tell you scientifically why I believe film is better, but I can offer my viewpoint as a professional photographer.

Digital images are made up of ones and zeros, composed of compression algorithms and computer files. Film is chemical. Does this matter? Perhaps. Pixels, which make up digital images, are square; whereas film grain is kind of round. The round shape of grain is perhaps more organic and pleasing to the eye than the harsh square pixels of digital.

One thing I do know is that I have yet to see a digital camera capture the highlight and shadow detail that an image shot on negative can. Yes, with digital you can take multiple shots and align them on a computer (using HDR, or high dynamic range photography), but negatives pretty much get everything on one shot.

For me, a lot of it is workflow and image quality. With digital, I was spending more time editing and backing up images onto multiple hard drives and discs than I was shooting. With film, I shoot the film with the look I want, and then I just have to sort the scans to a storytelling structure when I get them from my lab. I back them up once, knowing that I have physical negatives to turn to if my hard drives should fail. And trust me, they do fail. So not only am I getting image quality that I believe is more pleasing to the eye, I am also getting to spend more time living my life instead of messing around in Photoshop, applying effects to make my shots look like film. After all, why would I want to do that? If you like the way film looks as prints, then shoot film.

The other big reasons why I love film are exposure and flash tolerance. With digital, it’s like shooting slide film: Up or down even a third of a stop, and there is a noticeable difference in your image. Yes, you could correct in Raw digital images in your editing software, but that takes time. With film, I can shoot a 400-speed film anywhere from 200 to 1600 and process it normally, and I get great shots. I don’t have to worry about whether my exposure is dead on; I can just shoot. Of course, I always try to make sure it’s dead on, but sometimes life moves pretty quickly or lighting changes, and I don’t have time to change things and just shoot. With flash I can also feel safer, knowing that even if I overexpose with it, my subjects won’t be blown out. In effect, film loves light—it loves more light than it needs.

The image on the top shows the film exposed to only my on-camera flash, set to bounce, and the ambient exposure. The image on the bottom is with the studio strobes going off by accident and overexposing the negative—and giving a much better image.

These images were taken with 400-speed Kodak Portra 400 film, rated at 1600, in camera and processed normally. They were not push-processed. (We’ll discuss push processing later in this book.) In essence, I underexposed each frame by two full stops—three in some.

Case in point: I was in a portrait room, shooting some family members during a winter wedding. I had my camera set to about 1/30 at f/1.4 with ISO 800 film loaded. The room also contained my studio lighting setup that I had just used to shoot some group shots at f/8 with ISO 100 film. What I didn’t realize is that the studio strobes were set to slave mode (to fire when they see a flash), so when I fired off shots of people in the room with my on-camera flash, with the ISO 800 film and my lens wide open, I had no idea I was setting off the studio strobes! You might think that these shots would’ve been ruined, but they weren’t. They came out great, as you can see here! With film, I’m also set free to shoot larger formats than 35mm frames, so I can shoot higher-speed films on larger negatives and get images that look like they were shot at lower ISO settings, with even less grain and more details. Whether you’re shooting film or digital, the larger the capture area size, the more detail and light you’re utilizing to record your image. I can easily shoot medium format at a wedding and get highly detailed images that burst with color and detail, even at high ISOs.

In the following chapters, I will talk all about everything from choosing cameras and films, to processing and special processing, to getting your images scanned, and I’ll provide you with a number of assignments that should open your eyes, get you into the film workflow, and improve your photography skills.

Images were shot on Ilford 3200, a high-speed BW film, in a dark reception hall.

For me, the differences between film and digital are about the artistic approach and process more than about the technical aspects. Shooting film forces you to trust in the unknown a bit more. When you shoot in film, there isn’t any instant gratification (unless you’re shooting with instant Polaroid or Fuji stuff, and that’s an entirely different realm). You trust in the moment and trust in what you see when looking through the viewfinder. I’ve found that the trial-and-error period with film is lengthened over the course of time it takes to shoot, develop, and print. The learning curve with digital is much shorter because you can see when you like something or when something doesn’t work, and you can alter it immediately. This has definite perks, and I’m not saying that isn’t a strong plus for shooting digital. I mean, who really has time for anything these days, let alone learning? But something happens to us in the interim, when we step away from the shoot and come back to try again. I think there is growth in the “in between” and reflection. When discovering your craft, you may stumble across your personal style quite by accident or spend months and months experimenting with a certain film, developing, and light combination until you find exactly what you want (if that ever happens). I repeat: Waiting for something makes it more special.