23

Institutional Research 101

By Benjamin Ee1

This chapter is focused on how alpha researchers can add institutional research sources to their toolkit for generating new trading ideas.

Part 1 provides a “tourist guide” of sorts to the various streams of academic research on financial markets that have been energetically developed over the previous few decades. Part 2 is a general overview of analyst research and stock recommendations that researchers may encounter frequently in financial media. We talk about how to access analyst recommendations, as well as address the all-important question of how they can help to inspire systematic trading ideas.

ACADEMIC RESEARCH ON FINANCIAL MARKETS – NEEDLE MEETS HAYSTACK?

How should you find ideas for new market strategies? Inspiration can come from many sources including discussions with classmates, colleagues or friends, the financial press, seminars, books, and so on. In this chapter, we introduce another source for idea generation that the researcher can add to her toolkit: freely available academic papers on financial markets.

At first glance, the explosion of publicly available finance research by professors, graduate students, various market commentators, and others over the last few decades can make navigating existing works a daunting task for any newcomer. A search for “corporate finance” and “asset pricing” on Google Scholar in December 2014 yielded about 1.5 million and 1.3 million results, respectively; paring down the search to something far more specific, say the “cross-section of stock returns,” yields close to 10,000 results, including material from one of the 2014 Nobel Prize laureates.

A digestion of all existing works may therefore not be the best way to get quick inspiration.

This section attempts to provide a “rough and ready” guide for the newcomer to quickly start adding academic papers as a great source of ideas to their toolkit. Papers can be accessed via several means, some of which cost only as much as an internet connection. One important distinction is between “vetted” sources such as journals, and “open” sources.

Journals

Formal academic journals are where professors and professional researchers publish their results. Papers in formal journals have undergone a rigorous peer-review process, where other researchers critique them. Consequently, research that survived this process will usually be free of serious methodological errors. You may be able to get inspiration, not just for trading ideas, but also for new methodologies.

The topics discussed in these publications are usually representative of what the academic community judges to be “important” at the time of publication. This may only overlap partially with the priorities of a market strategist. The primary focus of the academic community is not to search for market strategies, but to understand the underlying forces governing economic interactions. There is a significant overlap between the two, but not every paper will be relevant. One easy way to understand the difference is by analogy to similar situations in the physical sciences – e.g. between investigating the fundamental laws of electromagnetism on the one hand, and building an MRI machine on the other.

Papers with conclusions that are more “general” are typically published in journals with a higher impact factor, and these will also be papers that the community pays more attention to. This has pluses and minuses for the strategist who wishes to make use of conclusions in such papers. There will be more work for you to do, going from a discussion on general economic forces such as “moral hazard,” to specific strategies. The discussion in journals may be a step removed from markets, and you might need to connect the dots yourself. On the other hand, there could be valuable economic ingredients in these, improving many strategies that you construct. Designing a new strategy by yourself based on inspiration from fundamental forces, as opposed to directly replicating applied findings, also makes it likely that your strategy will be different from other market participants. Table 23.1 shows some “general interest” journals in economics and finance that we have found useful in the past. If you have the time, it would be useful to check some of them out.2

Table 23.1 General interest economics and finance journals

| Journal | Link | 2014 RePec rank (impact factor) |

| The Quarterly Journal of Economics | qje.oxfordjournals.org | #1 (66) |

| Econometrica | http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1468-0262 | #3 (57) |

| Journal of Financial Economics | http://jfe.rochester.edu/ | #5 (40) |

| Journal of Political Economy | http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/journals/journal/jpe.html | #7 (34) |

| Review of Financial Studies | http://rfs.oxfordjournals.org/ | #10 (31) |

| American Economic Review | https://www.aeaweb.org/aer/index.php | #12 (29) |

| Journal of Finance | http://www.afajof.org/view/index.html | #15 (25) |

If you have time, also check out some of the other top journals in economics and finance at https://www.idea.repec.org/top/top.journals.simple.html.

In contrast with “general interest” journals, there are also “investments focused” journals, where work is more firmly aligned with describing strategies, or methodologies that are directly relevant in finding strategies. In some cases, it is more likely that you will be able to directly code up and replicate the strategy discussed. As mentioned above, the downside is that strategies may be described in such detail that the rest of the world could also be doing this. Nevertheless, once you have the core of a strategy coded up and tested, you can think about using it as a basis for further innovation. This might be easier than starting from square one. Table 23.2 lists some recommendations based on a listing from the CFA Institute.

Table 23.2 “Investments focused” journals

If academics have viable market strategies, why would they not keep them secret and trade the strategies themselves? Possible responses to this question include:

- One of their objectives could be to demonstrate the plausibility of theories about economic interactions, and the fact that their framework is consistent with market reactions is one of several pieces of evidence.

- Execution matters: Developing the infrastructure for efficient execution of otherwise excellent market strategies is a non-trivial undertaking, costly in terms of both time and capital.

- Career and reputational considerations: The expected benefit from publishing, e.g. in terms of the intellectual impact to one’s field, media mentions, potential consulting contracts, might factor into the decision to share the information.

- Lag time: It can take several years for a new academic paper to make it from conception to polished product in a journal. If the paper describes a highly actionable strategy, it will likely already have been picked up and implemented by other market participants in the meantime.

- Cost: Academic journals are expensive; you may be able to access these papers via your university/local library, or, in some cases, email the authors directly for a copy. Most academic authors are happy to send out copies of their papers.

Open Sources

These are repositories of papers that are generally free to access and, occasionally, free to contribute to. One implication of the latter feature is that papers may not have gone through the traditional peer-review process. In many cases, they may be early versions of formal academic papers, and so are written with the intention of ultimately passing review. Examples of open sources include papers on SSRN or arXiv. Once you have developed your own list of favorite academic authors, also check out the working papers section of their websites.

Table 23.3 lists open sources of papers.

Table 23.3 “Open” sources

| Name | Link |

| SSRN | http://www.ssrn.com/en |

| arXiv | http://arxiv.org |

| NBER website(working papers are only provided free of charge if downloaders meet specified criteria) | http://www.nber.org |

| CFA Institute website | http://www.cfainstitute.org/learning/tools/Pages/index.aspx |

Characteristics of open sources:

- Lower lag time: The latest research, by definition, will usually be a working paper rather than a published article. Capacity-limited market strategies are best implemented as soon as possible.

- Generally free: Working papers may generally be distributed by their authors for free, and most authors have an incentive to maximize ease of distribution.

- Greater variety: Formally reviewed journals represent the priorities of the communities whose work they chronicle. As with all fields, some subareas get greater prominence and discussion from time to time. There is no guarantee the contemporary focus of formal journals will be of the greatest interest to market strategists. However, a broader array of work can be found on SSRN or arXiv, where authors have greater latitude; the downside is that readers need to be more discerning in trying to decide how to spend their time.

- No peer review (yet): No peer review generally means that there is no real guarantee that the paper does not contain serious errors on methodology. Definitely exercise judgment on the subject matter; there are also several simple heuristics one can apply:

- Has the author published in peer-reviewed papers before?

- Is the paper intended for peer review (they may say “submitted to XYZ journal” on their website or in footnotes).

- Are conclusions based on commonly-used datasets (e.g. Compustat, CRSP), or rare/self-collected data. If the authors’ findings are based on rare data, is there any way to replicate the essence of their theories using commonly available data? You will usually need to do so in order to create a viable market strategy anyway.

- Is the methodology commonly used and intuitive?

A final source of research papers worth investigating are papers commissioned or released by market data vendors. These are papers that demonstrate viable strategies based primarily on the data being sold by the company in question (e.g. CRSP, WRDS, etc.), and therefore serve a marketing purpose, at least in part. Nonetheless, these can help you get up to speed on a new dataset quickly, and the strategies may also be transferrable. Examples include OptionMetrics (http://www.optionmetrics.com/research.html) and Ravenpack (http://www.ravenpack.com/research/white-papers/).

Following the Debate

One nice thing about publicly-shared research is that it invites debate. Other researchers write follow-up papers to critique and improve upon already published work. Following this debate may be useful if you are trying to figure out how to improve upon an existing framework, or would like to know what most people say about its strengths and weaknesses.

Most academic researchers in a university environment usually know what the community is saying about their latest paper. The same may not apply to you, sitting in your office or at home, reading the latest issue of Journal of Finance. How can you find out what other professional researchers are saying about the article you just read?

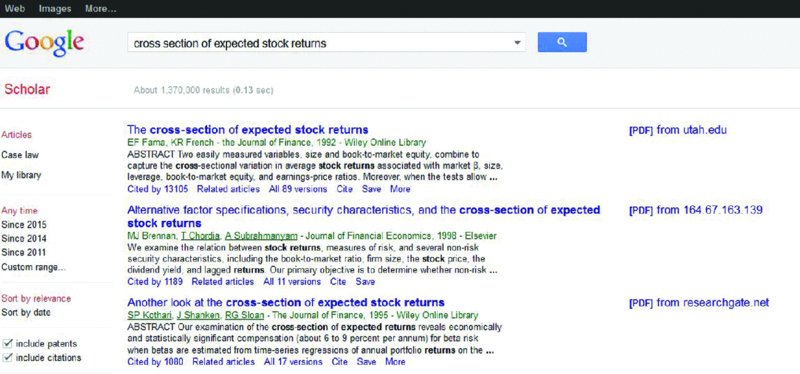

One way to do so is by following the citations of a paper. Citations are other academic papers that contain references to the paper that you just read. Often, they may discuss improvements, tweaks, or critiques. Contemporary information technology has made it fairly easy to follow these citations. Take any given paper, say “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns” (not an entirely bad starting point for a novice strategist). Entering this into Google Scholar (this is different from regular Google; use http://scholar.google.com), we get Figure 23.1.

Figure 23.1 The search result of “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns” on Google Scholar

Source: Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.

Immediately we see that the paper has been cited by more than 10,000 other papers as of December 2014. Clicking on the link that says “Cited by XXX” (highlighted by the black box in the figure), Google Scholar very helpfully returns a listing of papers that make some reference to the aforementioned paper as seen in Figure 23.2.

Figure 23.2 The detailed citation history of the paper “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns” on Google Scholar

Source: Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.

Following citations is a great way to find out everything that has been said about a given topic, and to figure out what has already been discussed as viable improvements and critiques of published ideas. As they say, no point reinventing the wheel!

Do the Authors of Academic Research Actually Believe Viable Market Strategies are Possible?

Congratulations! You have successfully made it to this part of a chapter discussing academic research, no small accomplishment.

Saving the most difficult questions for last, we may ask:

- Do academic researchers actually think it is possible to write down viable market strategies?

- Why are we even reading what these guys write, anyway, if they do not think that it is possible?

Both are fair questions. If you have any interest at all in markets, you have probably, at some point or another, engaged in debate with your college professors about beating the market. The words “efficient markets hypothesis” (EMH) and “not possible” may even come to mind, and the debate can be frustrating, not in the least because market returns on some days feel like a 10 mph speed limit on the interstate.

I would guess that academic researchers take the EMH so seriously not because it is an unbreakable law to be placed in the same category as the laws of gravity or motion. Rather, it is because market anomalies do, in fact, exist, but they need to be examined, checked, and double checked with extremely great care. On the one hand, market anomalies3 resulting from a variety of historical, institutional, legal, political, or economic reasons provide opportunities for profit; on the other hand, history is filled with investors who confused market anomalies with risk factors, and paid dearly.

In Summary

- It may be worth adding sources of academic research to your toolkit for finding new ideas.

- There have been countless papers written in finance research over the last few decades.

- A strategy for navigating these is essential. Established and well-regarded peer-reviewed journals can serve as potential starting points. Grouping papers into “conversation threads” by following citations is another complementary strategy, where you only follow the threads that you are interested in.

- The EMH is not an unbreakable law, but it deserves to be taken seriously.

ANALYST RESEARCH

“Goldman Sachs upgrades Netflix”

– TheStreet.com, July 2014

“Morgan Stanley downgrades technology sector”

– Yahoo Finance, December 2014

“Citigroup maintains rating on Alcoa Inc.”

– MarketWatch.com, December 2014

Research by sell-side analysts on firms and entire industries feature prominently in financial newspapers, conferences, blogs, and databases. It is not unusual to see analyst recommendations, upgrades, downgrades, or price target changes feature prominently in explanations of major stock price movements. Numerous studies by industry associations and academics have found that there is, indeed, valuable information contained in analyst research (see Francis et al. (2002) and Frankel et al. (2006)).

Nevertheless, “stock analyst” conjures up images of sophisticated researchers from Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan conducting high-powered earnings calls with Fortune 500 CEOs to gather information, and then presenting their findings to multibillion-dollar institutional funds. Against this image, how can you, as a new alpha researcher (with slightly less than a few billion dollars at your disposal), access this valuable body of analysis? Just as importantly, why should a researcher who is interested in constructing systematic market strategies be equally interested in what is typically company-specific analysis?

Accessing Analyst Research (for Free, of Course)

One interesting fact about stock analyst research is that some of it is surprisingly accessible, with the financial media acting as a valuable intermediary. “Financial media” in this case includes not only traditional sources like The Wall Street Journal or Bloomberg, but also aggregator websites such as Yahoo Finance and Google Finance. The latter are particularly useful in looking up analyst analysis, estimates, or questions during earning calls. As with academic research, most of these websites have at least some free/open content, and can be accessed from the comfort of your study.

To be Sure, You will Not be Able to Access All (or Even Most) Bank Analyst Research on a Company via Public Sources

Sell-side analysts can perform analyses that are extremely costly, sophisticated, and time consuming, and they naturally want to provide first access to valued clients. Nevertheless, the portion of analyst research that finds its way to public access media can be a valuable learning tool for new alpha researchers.

Looking Up Analyst Discussions and Estimates on Finance Portals

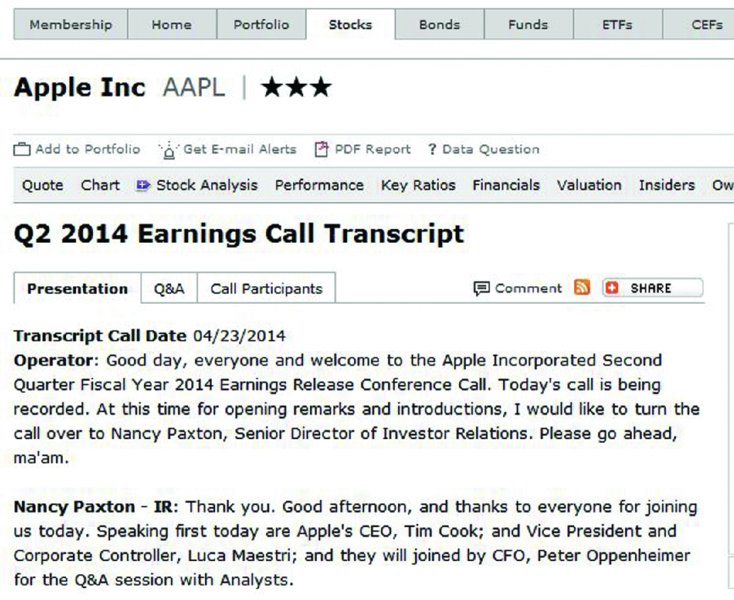

Given the proliferation of mentions in the financial media regarding analyst research, pulling up some mention of analyst research on a company is often as easy as entering that company’s stock ticker into your favorite finance portal. For instance, entering Apple’s stock ticker “AAPL” into Yahoo Finance’s portal turns up the headlines in Figure 23.3 in December 2014.4

Figure 23.3 Screen shot of search result for “AAPL” on Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo Finance © 2014. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

On the left of the screenshot, it is not difficult to quickly spot headlines and links to articles that draw upon analyst research. On the right side of the page, Yahoo Finance also has very helpfully summarized analyst estimates on AAPL’s earnings per share and average analyst recommendation (e.g. strong buy, sell, etc.). Clicking on the highlighted links above will generally lead to a description of a specific analyst’s view on AAPL, his thought process and data for arriving at such a view, caveats, as well as price targets and recommendations.

At the same time, you may wish to try out this process on other portals such as Google Finance, Bloomberg.com, and others, before picking the one that works best for yourself. When all else fails, try search engines directly (Google for “aapl analyst reports,” for instance).

As with analyst research, it is possible to get transcripts of company’s earning calls, as well as stock analyst questions and responses to those questions during the call, via finance portals. In the next example, we will use another finance portal called MorningStar, at http://www.morningstar.com (2014). This is one of the many places on the internet where you can find such information. Other examples include the SeekingAlpha website, at http://seekingalpha.com (2014), stock exchange websites (such as http:://www.nasdaq.com), and the investor relations section of company websites. Some of these also contain a fair amount of discussion from non-bank market commentators on specific industries as well as stocks. The discussion on these sites may be analogous to research from stock analysts, touching on points such as firm-specific fundamentals, macroeconomics, geo-politics and market conditions. Table 23.4 provides additional examples of such market commentary/finance blog sites.

Table 23.4 Market commentary and blogs on economics and finance

| Market commentary sites | Link |

| Bloomberg | http://www.bloomberg.com |

| Wall Street Journal | http://www.wsj.com |

| SeekingAlpha | http://www.seekingalpha.com |

| MorningStar | http://www.morningstar.com |

| TheStreet.com (only some content is free) | http://www.thestreet.com |

| Examples of finance blogs – by academic researchers, market analysts/commentators | Link |

| Econbrowser | http://econbrowser.com/ |

| Free Exchange | http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange |

| Zero Hedge | http://www.zerohedge.com/ |

| CXO Advisory | http://www.cxoadvisory.com/blog/ |

| Freakonomics | http://freakonomics.com/ |

| Marginal Revolution | http://marginalrevolution.com/ |

Note: In many places, our listing coincides with a ranking compiled by Time magazine. URL is http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/completelist/0,29569,2057116,00.html.

See if you can find AAPL’s Q2 2014 earnings call transcript with Analyst Q&A on the MorningStar website. If you are trying this in your browser, the important links to click on are highlighted with black rectangles (see Figure 23.4).

Figure 23.4 Screen shot of Apple Inc. on MorningStar.com with highlights

Source: © 2014 Morningstar, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

So Far, So Good. But Why Should You Care?

Good question. Most analyst reports (or market commentaries) focus on a single stock or industry, while you, as an alpha researcher, are looking for systematic market strategies that trade tens of thousands of stocks each day. So what if some analyst from Bank XYZ likes a particular company? How do we go from this to trading thousands of companies in 20 different stock exchanges across the world?

Here is why we think researchers looking for systematic market strategies can learn from reading stock analyst reports:

- Far more important than any specific “buy” or “sell” recommendation is the analyst’s thought process. Did he decide to upgrade AAPL because of industry-specific reasons (e.g. “the market for smartphones has been growing at triple digits”), or was it because of firm-specific reasons (net margins have been increasing over the last four quarters), or something more general, such as the company having a lower price/earnings ratio compared to the rest of the industry? Regardless of the reason, one interesting question is: Can I apply this to other companies, too? For instance, if the analyst says he likes AAPL because the CEO has been buying stock in the company, should this logic be applied only to AAPL, or to publicly-listed companies in general? This line of reasoning has been known to yield a new strategy idea or two.

- Analysts usually ask really good questions during earnings calls. They should, since they are paid a lot to do so. For a new researcher trying to figure out how to make sense of the dense collection of numbers that is a modern corporation’s financials, these questions can be a life saver. More information is not always better, especially if you have 20 pages of numbers per company, and are trying to separate signal from noise. How should you understand which accounting item is important? One clue is to think about which numbers or trends analysts focus on, and what they may be driving at with their questions. Are they puzzled by the extremely large and unseasonal change in inventories from one quarter to the next? Why is this important? As always, we can ask if it is something that is important beyond the company under discussion.

- Analysts have detailed industry knowledge. Industry-specific expertise has been cited, as Larrabee (2014) points out, as one of the most important attributes (and competitive advantages) of stock analysts. The best sell-side analysts are even able to move stock prices with their stock ratings and forecasts, and this effect is stronger among analysts with industry experience. This is relevant to researchers because there is much about methodology to be learnt from analyst work. For instance:

- Valuation methodologies vary across industries. Constructing a discounted cash flow may be very different for the manufacturing sector compared to financials for cyclical firms, compared to non-cyclicals, etc. Analysts may focus on different valuation metrics such as price/earnings ratio for one industry, and price/book ratio for another. To the alpha researcher, it is important to understand the underlying reasons for these differences in order to generalize to the universe of tradable issues.

- Each industry may have its own unique driver or measure of operational performance that usually features prominently in analyst reports. Dot coms used to look at “eyeballs” back in the late 1990s (perhaps they still do to some extent); airlines think about “passenger-miles”; while biotech companies may focus on drugs in the pipeline or drug trials. Understanding the key drivers of operational performance in each industry may help the alpha researcher trying to figure out inter-industry variations in her strategy performance.

- Analyst research can provide valid trading signals. As a bonus, analyst research can move stock prices on occasion. You may have seen headlines attributing a large price bump or fall in a specific ticker to an analyst upgrade or downgrade, increase in price targets, etc. There is an extensive body of academic research showing a link between analyst research and stock returns, which can be found on Google Scholar (2014) under “stock analyst research.” A better understanding of analyst recommendations may help you make better use of this information in constructing strategies.

Things to Watch Out for in Reading Analyst Research

Whether you are reading analyst research to look for inspiration on new market strategies, or wanting to use their recommendations and targets directly in strategy construction, it may help to keep in mind some of the pros, cons, and idiosyncrasies of analyst research.

- Positive bias. While different banks may have different approaches, academic researchers have argued that stock analysts, as a group, could exhibit positive bias. One possible implication is that the distribution of analyst recommendations may be skewed. For example, if we think about “buy,” “hold,” and “sell” recommendations, there might be far more “buy” than “sell” recommendations. Academic researchers have further studied reasons for this, as argued by Michaely and Womack (1999) and Lin and McNichols (1998), which question whether banks are inclined to issue optimistic recommendations for firms that they have relationships with.

- Herding. Herding refers to the theory that analysts try not to be too different from one another in their public recommendations and targets. As the theory goes, part of the reason for this may be behavioral. Making public stock price predictions (or “targets,” in analyst speak) is a risky endeavor with career implications. All else being equal, there may be some safety in numbers from going with the crowd. A corollary to this is that analysts who are more confident, or have established reputations, are usually willing to deviate more from consensus.

- Behavioral reasons aside, there may be sound reasons for analysts to arrive at similar conclusions – e.g. most might be working off the same sources of information. Hence, it might be interesting to understand major analyst deviations from consensus, what is unique about their analysis methods or data sources, and if this can be “systematized.”

Why do Stock Analysts Talk to the Financial Media?

If you were to invest significant time and energy into detailed analysis that produces wonderful trading ideas, your first impulse may not be to pick up the telephone and tell a bunch of reporters about it. After all, many ideas are capacity limited – only so many people can trade them before the price starts to move significantly and the chance for profit disappears.

Yet we find mention of analyst research in publicly accessible media reports all the time. In fact, we may even rely on this to some extent, since it allows us to peek into the world of analyst research at almost no cost. What explains this accessibility? Possible reasons include:

- Some meetings between stock analysts and the companies they cover are open to members of the public, and often covered by the financial press. One example of this is earnings calls, which are available through publicly available transcripts. A possible reason (at least in the United States) is SEC Regulation Fair Disclosure, known as FD (www.sec.gov, 2015), which states that non-public information disclosed by issuers to investment professionals must also be made available to all market participants. This includes analysts working for huge multibillion-dollar banks as well as members of the investing public.

- Some publicity probably does not hurt a stock analyst’s career. Media mentions and interviews may increase demand for an analyst’s research among investor clients, and high profile recommendations that are proven right (e.g. “calling” the market bottom in 2008) may fast track an analyst’s career. These are only possible if analysts go public with some of their research.

In Summary

- Analyst research may be accessible via the financial media.

- The methodologies and reasoning processes used by analysts in arriving at their recommendations may be a source of ideas for alpha researchers.

- Analyst recommendations and targets may be trading signals in their own right.

- Positive bias and analyst herding are two caveats to keep in mind.