IN THIS CHAPTER

Web development is more than just creating web pages.

Firefox, as a browser, can affect what a web page will look like. (To an extent, so can Internet Explorer; however, the user has no control over the appearance of a web page. In contrast, Firefox provides control.)

So you are going to look at web development with Firefox. You are not going to develop a website—that’s not the purpose of this chapter. If you want to develop websites, there are many good references on the topic, including those listed in the following note.

You can use these capabilities to help you design Firefox themes, extensions, and web pages. An example is a typical Firefox or Thunderbird theme that can consist of Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), images, and supporting files.

An extension might have all the same files that a theme has, plus you will also find JavaScript in it. If you are planning to develop themes or extensions, everything in this chapter will prove useful.

Web page and HTML developers will find that they need to use HTML, CSS, and a scripting language—usually JavaScript.

Hopefully, after you finish this chapter, you’ll understand how to use Firefox’s tools and the techniques necessary to be a successful web developer. You will also understand the ideas behind CSS.

This chapter covers

Issues such as Firefox’s compliance with web standards

Some of the tools available to developers

JavaScript and the JavaScript console

CSS, the standards, how they are supposed to work, and how you can use them

Firefox’s use of CSS

The document object model (DOM) inspector, a tool that helps you learn how a page is laid out

Note

If you want some good references on website building, two interesting titles are

Sams Teach Yourself Web Services in 24 Hours by Stephen Potts and Mike Kopack, Sams Publishing (ISBN: 0-672-32515-2).

Special Edition Using Microsoft FrontPage 2003 by Paul Colligan and Jim Cheshire, Que Publishing (ISBN: 0-7897-2954-7).

Both Que and Sams offer other similar books as well.

Let’s start with web page compliance.

Does Firefox comply with all the web standards? No. But then, neither does Internet Explorer, Mozilla, Opera, or any other web browser! No browser is 100% compliant with the standards.

It is my hope that Firefox is better than other browsers with regard to the standards. And, maybe it is. However, there is a lot of subjectivity in that it is often a case of comparing apples to oranges with compliance and standards. One browser complies with standard A, and the other with B. Which is better? Standard A is different from standard B, so they cannot be meaningfully compared.

First, what are these mythical standards? There is no government-appointed web standards organization—the Internet is strictly hands off with regard to the government (and that includes any government!). Instead, these standards come from many places. General Internet standards are set by the following:

Internet Architecture Board (IAB)

Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA)

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)

The Internet Research Task Force (IRTF)

RFC Editor (requests for comments describe how Internet standards are created)

That’s a lot of alphabetic soup—and this list is not exhaustive. However, for web standards, a few organizations are critical to our usage of the Web. The main web standards authority is the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

W3C defines standards, including

Cascading Style Sheets—CSS is used to add styles for web HTML documents. With CSS, you can set styles and override existing styles as desired.

DOM—Document object model.

Extensible Hypertext Markup Language—XHTML is the next step beyond HTML. Looked at as simply as possible, XHTML is HTML wrapped in XML.

Extensible Markup Language—XML is a data format that enables the intelligent transfer of information from one point to another.

Hypertext Markup Language—HTML is the primary language standard for the Web. There are three main versions of HTML: 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0. There are subreleases of these versions as well.

Internationalization—Deals with differences in locations, such as language.

Uniform resource identifier—URIs are sometimes called uniform resource locators (URLs), but the correct term is URI.

Web Services Description Language—WSDL uses XML to transfer data or procedures between two points.

As stated at the beginning of this chapter, we are most interested in CSS and the DOM inspector.

There are some developer tools that you, as a Firefox developer, will find useful. Refer to Chapter 8, “Making Extensions Work for You,” and review the developer tools available as extensions.

On the Mozilla add-ons web page, http://addons.mozilla.org/developers, is a hyperlink labeled Developers (see Figure 14.1). The developer section at Mozilla requires that you be a registered developer. If you have not registered, you can do so easily. All you need is your name, an email address, and a password. Register, and Mozilla will send a confirmation email to your email address, which will contain a link to the confirmation page for your developer account. The entire registration process takes but a few seconds.

When you click the Developers link, you go to your own private developer web page (see Figure 14.2). At this page you can publish your extensions and themes. You can also modify your profile, which you created when you registered.

You might find the following developer tools useful when developing extensions or themes. For more information on these tools, visit Mozilla’s website.

The DebugLogger tool is designed for extension developers. This extension provides a way to get information about your extension as you develop it, without resorting to dump() calls. The nice thing about DebugLogger is that it enables you to debug multiple projects at the same time. This is useful when you have an interaction bug, where an extension fails due to another extension’s presence.

This extension adds a new tab called Cookies to the Page Info dialog box. This tab displays every cookie belonging to the page and shows the page’s cookies, but globally and in detail.

Figure 14.3 shows the cookies for Google. It can be seen that the name of the cookie is PREF and the value consists of identifiers, an equals sign, and a value. For example, NR=100 says that I wish to see 100 results per search page (the default is 10).

The View Rendered Source tool is used to help debug a number of object types. This handy extension displays HTML that is color-coded, styled, and formatted. It also displays the source exactly as Firefox would display it. Those who are developing the following code should check out View Rendered Source:

CSS

HTML

JavaScript

XML

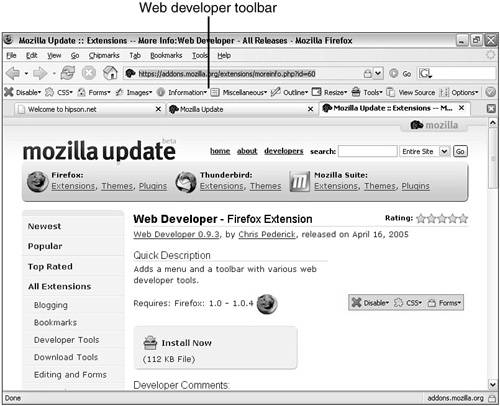

The Web Developer extension adds both a menu and a toolbar with web development tools. Figure 14.4 shows the installed Web Developer toolbar.

Figure 14.4. Much of what the toolbar does is always available, but the Web Developer toolbar makes accessing it easier.

The Web Developer extension makes HTML development much easier, although more advanced websites will also want to use scripting—the topic for our next section.

Some tools and preferences are very helpful to developers. One such tool is the JavaScript console, which is installed with JavaScript. A number of JavaScript-related preferences (some of which exist in about:config and some of which must be added) improve the usability of JavaScript debugging tools.

The JavaScript Console is a window (separate from Firefox’s browser window) that displays error messages generated in JavaScript code. In Figure 14.5, you can see that the JavaScript Console started after opening Firefox and showed several errors in JavaScript code while running and a final error at shutdown.

The Venkman extension is a powerful JavaScript debugger. Programmers familiar with systems such as Microsoft Visual Basic 6, Visual C/C++, and other programming development tools will be familiar with Venkman. The Venkman extension does the following:

Enables you to continue from the current point, perform single-step execution, step over a subfunction call, or step out of a subfunction call.

Profiles code, showing which parts seem to be consuming the most time. This gives information about which parts of the script should be optimized if possible.

Saves and restores settings such as breakpoints and variable watches. Venkman enables you to automatically save settings upon exit.

Opens both a web page and files. Most are displayed in tabs in the source code window, allowing you to easily navigate between each.

Venkman is the most powerful JavaScript development tool. It works well with other JavaScript tools and preferences (our next section).

When developing JavaScript, several preferences should be set to maximize the JavaScript Console’s effectiveness:

browser.dom.window.dump.enabled = true—This causes Firefox to enable thedump()statement, which prints to the standard console. You must start Firefox with the--consoleparameter.javascript.options.showInConsole = true—This tells Firefox to log chrome file errors to the JavaScript Console.javascript.options.strict = true—With thestrictpreference, this tightens the limits on error collection. This increases the number of logged warnings; you will see warnings in your code as well as in other code.nglayout.debug.disable_xul_cache = true—This tells Firefox to disable the XUL cache. If the XUL is cached, Firefox must be restarted for any changes to be effective.

Firefox supports a number of command-line options. These are sometimes referred to as command-line parameters— either terminology is acceptable. These options are documented at http://www.mozilla.org/docs/command-line-args.html. This page references Mozilla Suite, not Firefox, but most options listed there work with Firefox.

Chapter 6, “Power Firefox Tricks and Techniques,” introduced CSS. CSS are an important part of both the Web and Firefox. Without CSS web pages, the Internet pages would not be as consistent as they are today.

There are two levels of CSS: CSS-1 and CSS-2.1. The next level, CSS-3, is under development. With style sheets, you can define the look and feel of web documents. A style sheet can define fonts, colors, character size and spacing, and style definitions that contain a complex number of effects. In fact, CSS are similar to Microsoft Word’s style sheets.

In Microsoft Word, a style sheet defines a paragraph’s formatting, including

Paragraph formatting such as line spacing, space above and below, indents, text alignment, and so on

Font specifications, such as type face, size, color, and so on

Tabs, both the type and location

Borders, such as width, style, color, and so on

Frames, such as location, size, and so on

Numbering and bullet style

The first CSS standard is called Level 1. This standard was created in late 1996 and later revised in 1999. When it was revised, no revision indicator was used. CSS-1 is rather simple and easy to use. It requires that you know basic HTML and understand the concepts and components of style. Some of the major parts of CSS-1 are discussed next. The following items are part of the standards created by W3C.

Note

Throughout this chapter, the term selector is used. A selector is the mechanism to select or group elements together to allow them to be styled as a single object.

Pseudo means false or not real. CSS uses pseudoclasses and pseudoelements to allow the definition of items that are not part of HTML’s classes or elements:

Anchor pseudoclasses—A link on a document is technically referred to as an anchor. An anchor that has been visited (this information is usually contained in the history list) can be colored or formatted differently than a link that has not been visited.

Typographical pseudoelements—The first-line and first-letter pseudo elements are defined as typographical pseudo elements:

First-line pseudoelements—The first line of a block (paragraph) might be formatted differently from following lines. This effect is flexible, in that as the line length varies, the rendering engine compensates for this variation.

First-letter pseudoelements—Frequently you see the first letter in a paragraph printed as a drop capital. This is where the letter is actually two lines high, spanning the start of both the first and second lines. This is an example of first-letter formatting. The first-letter pseudoelement allows this type of formatting. First-letter formatting is not restricted to drop capitals but can be any valid character-level formatting.

It is expected that more than one CSS will be used to format a given object in the rendered document. Several simple rules define cascading inheritance.

A style sheet need not be complete. Several partial style sheets can be combined to create a complete style sheet. Both authors and viewers can define style sheets (the author is the person who has written the web page, for example, whereas the viewer is the person using Firefox).

Note

A style sheet definition can be declared with the !important keyword, making that style override definitions that are not defined with !important.

An author’s !important overrides any preceding normal or important definitions and any following normal definitions.

A viewer’s !important overrides an author’s normal definition but not an author’s !important definition.

Cascading order says that style definitions follow these rules, in this order:

Rank definitions by important or normal. Any important definition always overrides normal definitions.

Then rank definitions by source, either author or viewer. Any author important definition overrides a viewer important.

Next, rank the definitions by scope. More specific scope overrides less specific scope.

If two definitions carry the same weight at this point, pick the last one (later definitions override earlier definitions).

The CSS formatting model includes the following classes of formatting:

Block-level elements

Vertical formatting

Horizontal formatting

List-item elements

Floating elements

Inline elements

Replaced elements

The height of lines

The canvas

BR elements

Various properties that can be set with CSS- 1 include notation for property values and how these properties are specified. Additional specifications are

Font properties—These describe the font’s look and formatting and include

font,font matching,font-family,font-style,font-variant(such as italic),font-weight(light, bold, or normal, for example), andfont-size.Color and background properties—These include

background,color,background-color,background-image,background-repeat,background-attachment, andbackground-position.Text properties—These are properties such as

word-spacing,letter-spacing,text-decoration,vertical-align,text-transform,text-align,text-indent, andline-height.Box properties—These include

margins,padding,border,width,height,float, andclear.Classification properties—These include

display,white-space,list-style-type,list-style-image,list-style-position, andlist-style.

One final part of CSS-1 is conformance. Conformance specifies how a user agent (such as a browser rendering engine) would conform to the standard.

Conformance also specifies that parsing be forward compatible; that is, any user agent that is compatible with later versions of CSS must also support earlier versions. Thus, a user agent that supports CSS Level 2.1 will also support CSS Level 1.

With CSS-2 (and 2.1, which soon followed it), some important functionalities were added. CSS Level 2.1 is the current standard; CSS-3 won’t be a standard for some time, most likely.

In addition to the functionality found in CSS-1, there is some new functionality:

Media types—. Describe the media that will display the content. Some examples are

print(where the content will be sent to a printer),screen(content is displayed on the screen), andBraille. This example shows both print and handheld media is used:media="print, handheld"

Inheritance—. This is where a child element inherits its parent element’s attributes when no matching attribute is specified. For example, in

<H1>The headline <EM>is</EM> important!</H1>, the subelementiswould inherit the parent (containing) element’s styles such as color, font, and so on.Page—. This specifies that the media will be paged and is often used with printed output (refer to the previous bullet about media types).

@page { size 8.5in 11in; margin: 4cm }specifies that the page is letter size, with a 4cm margin. The mixing of units of measure (English and metric) is acceptable but perhaps not recommended.Aural or sound—. Indicates a style sheet that will be aural (sound-based). Within aural are items such as

volume,voice,pause, and other attributes and styles. For example,H1{volume: x-loud}indicates that the sound will be very loud.Internationalization—. Virtually all operating systems and computers take into consideration that styles vary from country to country, so it is important that your style sheets be able to do so as well. CSS-2 includes support for various national and language requirements.

Font support—. CSS includes better matching of fonts when a specified font is unavailable, as well as other support. As an example,

BODY { font-family: Baskerville, "Phaisarn" }specifies that Baskerville will be used for Latin characters and that Phaisarn will be used for Thai fonts.Tables—. These are often used to categorize or group data, adding a powerful layout tool. Tables have rows, columns, headers, and borders.

Positioning—. Enables content to be positioned to absolute, relative, floating, or fixed. Using relative positioning, related elements can be positioned based on their relationships. As an example, a child element can be positioned relative to its parent or sibling elements.

Boxes—. Can be created with backgrounds, content, padding borders, and margins. Boxes serve to set content elements apart or to draw attention to important elements.

Overflow—. Used with boxes, this defines how any child element of a box will be treated should it overflow the box’s borders. Overflow can occur under a number of conditions, such as lines that can not be broken because there is no white space in the line. Or, the box might be ill-defined. Overflow values include

visible,hidden,scroll,auto, andinherit.Visual aspects—. For example, minimum and maximum height and widths might be set with visual aspects.

Selectors—. These include

descendant,child,adjacent, andattributeselectors. For example,H1 { color: green } EM { color: red }are selectors and the element<H1>This headline is <EM>very</EM> important</H1>displays the text in green, with the exception of the wordvery, which will be red.Automatically generated conten—. Lets you create content that is automatically numbered (such as page, chapter, or section numbers).

Shadows—. Used to make text stand out. An interesting effect is to set the text color to the same color as the background and the shadow color to a contrasting color. This displays only the shadow outlining the text (while the text, being the same color as the background, becomes invisible).

Pseudoclasses—. These are elements such as

:first-child,:hover,:focus, and:lang. They allow content to dynamically respond to user input. As an example,:hovermight specify a different color for an element when the mouse pointer is held over the element.Color and font—. These add new system colors and fonts and make defining colors that match those that the system uses easier. Color definitions are similar to those in the Windows Display Properties, Appearance tab. However, the names used are not identical to those in Windows.

Cursor—. Enables the specifying of a cursor(s) for the document being displayed. Cursors are defined in a cursor resource URL (such as

cursor : url("first.cur"), url("second.csr"). If it’s a system-defined cursor, such ascrosshair,pointer, ormove, it can be defined in lieu of a cursor file.Outlines—. Can be drawn around an object, with the color, style, and width specified. Outlines take no space and need not be rectangular in shape.

!important—. In CSS-1, an author’s!importanttakes precedence over the viewer’s!important. In CSS-2, though, the viewer’s!importantreigns supreme, taking precedence over the author’s.

In CSS-1, display has an initial value of block. In CSS-2, display’s initial value is inline.

There are other changes too technical to document in this book. It can be useful to visit W3C’s web page and read the standards.

Firefox uses CSS in its basic installation set (see Firefox’s res folder) and with user profiles (userChrome.css and userContent.css).

All user profiles contain userChrome-example.css and userContent-example.css. Firefox keeps a standard version of both of these files in the Firefox installation folder (defaultsprofilechrome). Firefox itself ignores both of these files, so they must be copied (or renamed) to be recognized by Firefox. (userChrome-example.css should become userChrome.css, and userContent-example.css should become userContent.css.)

Also found in the Firefox installation folder is a subfolder named res. In res are eight .css files:

EditorOverride.cssandEditorContent.css—These control the editor’s WYSIWYG appearance when in Browser Preview mode.forms.css—This contains styles for old GFX forms widgets.html.css—This is the overall style sheet for HTML.mathml.css—This specifies the formatting of math.platform-forms.css—This loadsforms.css.quirk.css—This describes quirks mode, in which Firefox emulates many of Netscape Navigator’s and Internet Explorer 4’s nonstandard behaviors.ua.css—This is the style sheet that controls the mapping of HTML elements as block or inline.viewsource.css—This defines how source looks when edited in Firefox.

These are style sheets used by default in Firefox. However, the important style sheets are those that define themes. Because themes are packaged as JAR files, you don’t usually see the .css files that make up a theme. A typical complete theme that is well-designed might contain as many as 100 CSS files, along with image files for each visual object (such as buttons, backgrounds, and so on) and other files. In fact, a well-done theme will have 300 or more files. Most of the files for themes are image files (either .gif or .png files).

In Chapter 15, “Creating Your Own Theme,” you will create a simple theme. The theme you create won’t have this many files and CSS, however.

The two CSS files users might find they want to make changes in are userChrome.css and userContent.css.

The userChrome.css file is the easiest tool for you to modify the way Firefox looks. Almost anything you might want to set to quickly modify the look of Firefox can be set in this file.

Mozilla provides a sample userChrome.css file (see Listing 14.1). This sample file has a few modifications already written for you. You can take a look at this file and see exactly how the CSS affects the way Firefox looks. (I have reformatted comment lines in the listing to make it more readable.)

Example 14.1. userChrome.css

/* Edit this file and copy it as userChrome.css into your profile-directory/chrome/ */ /* This file can be used to customize the look of Mozilla's user interface * You should consider using !important on rules which you want to override defaultsettings. */ /* Do not remove the @namespace line — it's required for correct functioning */ @namespace url("http://www.mozilla.org/keymaster/gatekeeper/there.is.only.xul"); /* set default namespace to XUL */ /* Some possible accessibility enhancements: */ /* Make all the default font sizes 20 pt:* * * { * font-size: 20pt !important * } */ /* * Make menu items in particular 15 pt instead of the default size: * * menupopup > * { * font-size: 15pt !important * } */ /* * Give the Location (URL) Bar a fixed-width font * * #urlbar { * font-family: monospace !important; * } */ /* * Eliminate the throbber and its annoying movement: * * #throbber-box { * display: none !important; * } */ /* For more examples see http://www.mozilla.org/unix/customizing.html */

Taking a close look at the listing, you see that you can set the font size for everything:

{

font-size: 20pt !important

}

In this small piece are two important parts of a CSS. The first is a definition of the font size (font-size: 20pt), and the other is the !important that specifies that this particular setting must be used unless you (the user) say otherwise in another setting.

The same is true for this part of the CSS file:

menupopup > * {

font-size: 15pt !important

}

The first line specifies that you are modifying the pop-up menu font size, setting it to 15 points, from whatever the default was (see Figure 14.6). This only affects the pop-up menus, and not the top-level menu, as Figure 14.6 shows.

Figure 14.6. Notice the size difference between the word View in the top-level menu and the items in the pop-up menu.

This change makes things quite large, so a bit of fine-tuning is in order. You could also specify a color:

menupopup > * {

font-size: 15pt !important;

color: red !important

}

Although it’s difficult to see in the figure, the pop-up menu items are in red. Notice how we separated each of the attributes we set with a semicolon. Also, each attribute name has a colon following it, and each attribute has its own !important specification.

Following the same concept one step further, consider this code:

menupopup > * {

font-size: 15pt !important;

background: green !important;

color: red !important

}

Now the pop-up menus will be red text on a green background. Perhaps that’s a bit hard to read (both colors have about the same luminosity, or brightness). Therefore, you might be more inclined to make the background a lighter gray and the text a darker color.

The supplied userContent.css example (userContent-example.css) lets you change the way default items in a web page appear. Again, in Listing 14.2, I’ve reformatted the comments so the listing won’t be too large.

Example 14.2. userContent-example.css

/* Edit this file and copy it as userContent.css into your profile-directory/chrome/ */

/* Each example is commented out in this example */

/* This file can be used to apply a style to all web pages you view

* Rules without !important are overruled by author rules if the author sets any.

* Rules with !important overrule author rules. */

/* example: turn off "blink" element blinking

*

* blink { text-decoration: none ! important; }

*

*/

/* example: give all tables a 2px border

*

* table { border: 2px solid; }

*/

/* example: turn off "marquee" element

*

* marquee { -moz-binding: none; }

*

*/

/* For more examples see http://www.mozilla.org/unix/customizing.html

*/

Looking at this example, the first change it makes is to the blink tag. Perhaps you don’t like blinking text on web pages. If you’re an Internet Explorer user, you probably don’t (yet) know what blink is because Internet Explorer does not support blinking text. But, you can set blink to off:

* blink { text-decoration: none ! important; }

First, you have the tag’s keyword, blink. Then you set text-decoration to none. You can set text-decoration to any of these values:

none—Specifies that the text won’t have any special attributes.underline—The text will have an underline.overline—The text will have an overline.line-through—The text will have a line through it.blink—The text will blink.

Not all these values are exclusive; the text could blink and have an underline, overline, or line-through. Naturally, setting text-decoration to none precludes setting any of the other attributes.

Another example from userContent.css is shown here:

/* example: turn off "marquee" element

*

* marquee { -moz-binding: none; }

*

*/

This example deserves special attention because it has a nonstandard setting: "-moz-binding:". This property is used to associate a URI and is used to specify that the property is to be inherited, or is set to none.

The document object model (DOM) is an interface standardized by W3C to allow programmers a methodology to create dynamic content. This is referred to as Dynamic HTML (DHTML) by some. DOM includes such functionalities as CSS, HTML, XML, and other components.

Figure 14.7 shows the DOM Inspector window. In this figure you are looking at eBay’s home page.

Figure 14.7. The web page is shown in the bottom pane, with DOM Inspector information in the upper two panes.

The DOM Inspector is useful to show the layout and hierarchy of your document’s code.

Here are a few ideas from the experts:

Firefox attempts to comply with all web standards. However, just like all other browsers, there are areas that do not comply.

Firefox has a basic built-in developer interface. Additionally, a number of extensions can be used to improve the developer support.

CSS are the way that documents appear. Both the document’s author and the viewer can apply style sheets to modify the document’s appearance.

Firefox uses CSS for the browser’s look and feel and for content. All styles are created using CSS and images.

Chrome refers to how the program (Firefox) appears to the user. When a custom style is used, the Chrome is modified.

Content refers to the content displayed by Firefox. You can either accept the author’s styles or apply your own styles to content.

CSS allows multiple levels of styles to be applied. Styles loaded later can take precedence over earlier styles.

You can use

!importantto signify a style that must be adhered to. Of course, the last loaded!importantoverrides earlier occurrences of!important.The Firefox DOM Inspector allows viewing the document hierarchy and object properties.