CHAPTER 2

Ethical Hacking and the Legal System

We currently live in a very interesting time. Information security and the legal system are being slammed together in a way that is straining the resources of both systems. The information security world uses terms like “bits,” “packets,” and “bandwidth,” and the legal community uses words like “jurisdiction,” “liability,” and “statutory interpretation.” In the past, these two very different sectors had their own focus, goals, and procedures and did not collide with one another. But, as computers have become the new tools for doing business and for committing traditional and new crimes, the two worlds have had to independently approach and then interact in a new space—a space now sometimes referred to as cyberlaw.

In this chapter, we’ll delve into some of the major categories of laws relating to cybercrime and list the technicalities associated with each individual law. In addition, we’ll document recent real-world examples to better demonstrate how the laws were created and have evolved over the years. We’ll discuss malware and various insider threats that companies face today, the mechanisms used to enforce relevant laws, and federal and state laws and their application.

We’ll cover the following topics:

• The rise of cyberlaw

• Understanding individual cyberlaws

The Rise of Cyberlaw

Today’s CEOs and management not only need to worry about profit margins, market analysis, and mergers and acquisitions; now they also need to step into a world of practicing security with due care, understanding and complying with new government privacy and information security regulations, risking civil and criminal liability for security failures (including the possibility of being held personally liable for certain security breaches), and trying to comprehend and address the myriad of ways in which information security problems can affect their companies. Business managers must develop at least a passing familiarity with the technical, systemic, and physical elements of information security. They also need to become sufficiently well-versed in relevant legal and regulatory requirements to address the competitive pressures and consumer expectations associated with privacy and security that affect decision making in the information security area—a large and ever-growing area of our economy.

Just as businesspeople must increasingly turn to security professionals for advice in seeking to protect their company’s assets, operations, and infrastructure, so, too, must they turn to legal professionals for assistance in navigating the changing legal landscape in the privacy and information security area. Legislators, governmental and private information security organizations, and law enforcement professionals are constantly updating laws and related investigative techniques in an effort to counter each new and emerging form of attack and technique that the bad guys come up with. This means security technology developers and other professionals are constantly trying to outsmart sophisticated attackers, and vice versa. In this context, the laws being enacted provide an accumulated and constantly evolving set of rules that attempts to stay in step with new types of crimes and how they are carried out.

Compounding the challenge for business is the fact that the information security situation is not static; it is highly fluid and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Networks are increasingly porous to accommodate the wide range of access points needed to conduct business. These and other new technologies are also giving rise to new transaction structures and ways of doing business. All of these changes challenge the existing rules and laws that seek to govern such transactions. Like business leaders, those involved in the legal system, including attorneys, legislators, government regulators, judges, and others, also need to be properly versed in developing laws and in customer and supplier product and service expectations that drive the quickening evolution of new ways of transacting business—all of which can be captured in the term cyberlaw.

Cyberlaw is a broad term encompassing many elements of the legal structure that are associated with this rapidly evolving area. The increasing prominence of cyberlaw is not surprising if you consider that the first daily act of millions of American workers is to turn on their computers (frequently after they have already made ample use of their other Internet access devices and cell phones). These acts are innocuous to most people who have become accustomed to easy and robust connections to the Internet and other networks as a regular part of life. But this ease of access also results in business risk, since network openness can also enable unauthorized access to networks, computers, and data, including access that violates various laws, some of which we briefly describe in this chapter.

Cyberlaw touches on many elements of business, including how a company contracts and interacts with its suppliers and customers, sets policies for employees handling data and accessing company systems, uses computers to comply with government regulations and programs, and so on. A very important subset of these laws is the group of laws directed at preventing and punishing unauthorized access to computer networks and data. This chapter focuses on the most significant of these laws.

Security professionals should be familiar with these laws, since they are expected to work in the construct the laws provide. A misunderstanding of these ever-evolving laws, which is certainly possible given the complexity of computer crimes, can, in the extreme case, result in the innocent being prosecuted or the guilty remaining free. And usually it is the guilty ones who get to remain free.

Understanding Individual Cyberlaws

Many countries, particularly those whose economies have more fully integrated computing and telecommunications technologies, are struggling to develop laws and rules for dealing with computer crimes. We will cover selected U.S. federal computer-crime laws in order to provide a sample of these many initiatives; a great deal of detail regarding these laws is omitted and numerous laws are not covered. This chapter is not intended to provide a thorough treatment of each of these laws, or to cover any more than the tip of the iceberg of the many U.S. technology laws. Instead, it is meant to raise awareness of the importance of considering these laws in your work and activities as an information security professional. That in no way means that the rest of the world is allowing attackers to run free and wild. With just a finite number of pages, we cannot properly cover all legal systems in the world or all of the relevant laws in the United States. It is important that you spend the time necessary to fully understand the laws that are relevant to your specific location and activities in the information security area.

The following sections survey some of the many U.S. federal computer crime statutes, including:

• 18 USC 1029: Fraud and Related Activity in Connection with Access Devices

• 18 USC 1030: Fraud and Related Activity in Connection with Computers

• 18 USC 2510 et seq.: Wire and Electronic Communications Interception and Interception of Oral Communications

• 18 USC 2701 et seq.: Stored Wire and Electronic Communications and Transactional Records Access

• The Digital Millennium Copyright Act

• The Cyber Security Enhancement Act of 2002

• Securely Protect Yourself against Cyber Trespass Act

18 USC Section 1029: The Access Device Statute

The purpose of the Access Device Statute is to curb unauthorized access to accounts; theft of money, products, and services; and similar crimes. It does so by criminalizing the possession, use, or trafficking of counterfeit or unauthorized access devices or device-making equipment, and other similar activities (described shortly), to prepare for, facilitate, or engage in unauthorized access to money, goods, and services. It defines and establishes penalties for fraud and illegal activity that can take place through the use of such counterfeit access devices.

The elements of a crime are generally the things that need to be shown in order for someone to be prosecuted for that crime. These elements include consideration of the potentially illegal activity in light of the precise definitions of “access device,” “counterfeit access device,” “unauthorized access device,” “scanning receiver,” and other definitions that together help to define the scope of the statute’s application.

The term “access device” refers to a type of application or piece of hardware that is created specifically to generate access credentials (passwords, credit card numbers, long-distance telephone service access codes, PINs, and so on) for the purpose of unauthorized access. Specifically, it is defined broadly to mean:

...any card, plate, code, account number, electronic serial number, mobile identification number, personal identification number, or other telecommunications service, equipment, or instrument identifier, or other means of account access that can be used, alone or in conjunction with another access device, to obtain money, goods, services, or any other thing of value, or that can be used to initiate a transfer of funds (other than a transfer originated solely by paper instrument).

For example, phreakers (telephone system attackers) use a software tool to generate a long list of telephone service codes so they can acquire free long-distance services and sell these services to others. The telephone service codes that they generate would be considered to be within the definition of an access device, since they are codes or electronic serial numbers that can be used, alone or in conjunction with another access device, to obtain services. They would be counterfeit access devices to the extent that the software tool generated false numbers that were counterfeit, fictitious, or forged. Finally, a crime would occur with each undertaking of the activities of producing, using, or selling these codes, since the Access Device Statute is violated by whoever “knowingly and with intent to defraud, produces, uses, or traffics in one or more counterfeit access devices.”

Another example of an activity that violates the Access Device Statute is the activity of crackers, who use password dictionaries to generate thousands of possible passwords that users may be using to protect their assets.

“Access device” also refers to the actual credential itself. If an attacker obtains a password, credit card number, or bank PIN, or if a thief steals a calling-card number, and this value is used to access an account or obtain a product or service or to access a network or a file server, it would be considered a violation of the Access Device Statute.

A common method that attackers use when trying to figure out what credit card numbers merchants will accept is to use an automated tool that generates random sets of potentially usable credit card values. Two tools (easily obtainable on the Internet) that generate large volumes of credit card numbers are Credit Master and Credit Wizard. The attackers submit these generated values to retailers and others with the goal of fraudulently obtaining services or goods. If the credit card value is accepted, the attacker knows that this is a valid number, which they then continue to use (or sell for use) until the activity is stopped through the standard fraud protection and notification systems that are employed by credit card companies, retailers, and banks. Because this attack type has worked so well in the past, many merchants now require users to enter a unique card identifier when making online purchases. This identifier is the three-digit number located on the back of the card that is unique to each physical credit card (not just unique to the account). Guessing a 16-digit credit card number is challenging enough, but factoring in another three-digit identifier makes the task much more difficult without having the card in hand.

Another example of an access device crime is skimming. Two Bulgarian men stole account information from more than 200 victims in the Atlanta area with an ATM skimming device. They were convicted and sentenced to four and a half years in federal prison in 2009. The device they used took an electronic recording of the customer’s debit card number as well as a camera recording of the keypad as the password was entered. The two hackers downloaded the information they gathered and sent it overseas—and then used the account information to load stolen gift cards.

A 2009 case involved eight waiters who skimmed more than $700,000 from Washington, D.C.–area restaurant diners. The ringleaders of the scam paid waiters to use a handheld device to steal customer credit card numbers. The hackers then slid their own credit cards through a device that encoded stolen card numbers onto their cards’ magnetic strips. They made thousands of purchases with the stolen card numbers. The Secret Service, which is heavily involved with investigating Access Device Statute violations, tracked the transactions back to the restaurants.

New skimming scams use gas station credit card readers to get information. In a North Carolina case, two men were arrested after allegedly attaching electronic skimming devices to the inside of gas pumps to steal bank card numbers. The device was hidden inside gas pumps, and the cards’ corresponding PINs were stolen using hidden video cameras. The defendants are thought to have then created new cards with the stolen data. A case in Utah in 2010 involved about 180 gas stations being attacked. In some cases, a wireless connection sends the stolen data back to hackers so they don’t have to return to the pump to collect the information.

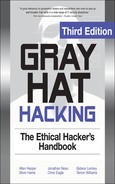

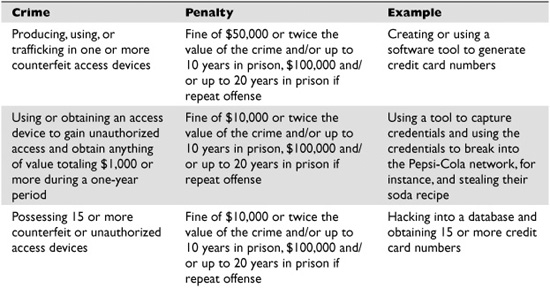

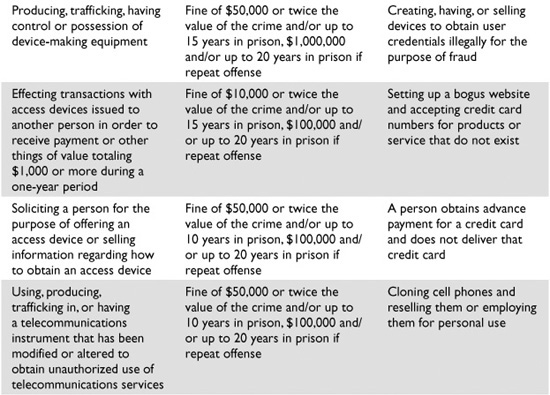

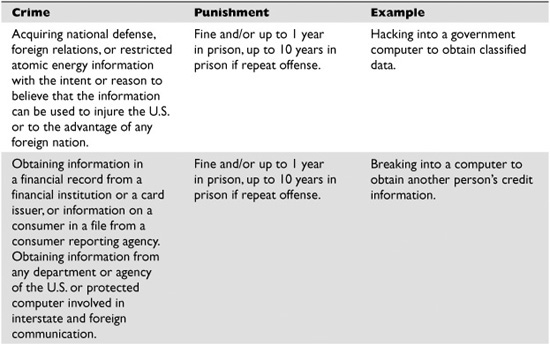

Table 2-1 outlines the crime types addressed in section 1029 and their corresponding punishments. These offenses must be committed knowingly and with intent to defraud for them to be considered federal crimes.

Table 2-1 Access Device Statute Laws

A further example of a crime that can be punished under the Access Device Statute is the creation of a website or the sending of e-mail “blasts” that offer false or fictitious products or services in an effort to capture credit card information, such as products that promise to enhance one’s sex life in return for a credit card charge of $19.99. (The snake oil miracle workers who once had wooden stands filled with mysterious liquids and herbs next to dusty backcountry roads now have the power of the Internet to hawk their wares.) These phony websites capture the submitted credit card numbers and use the information to purchase the staples of hackers everywhere: pizza, portable game devices, and, of course, additional resources to build other malicious websites.

Because the Internet allows for such a high degree of anonymity, these criminals are generally not caught or successfully prosecuted. As our dependency upon technology increases and society becomes more comfortable with carrying out an increasingly broad range of transactions electronically, such threats will only become more prevalent. Many of these statutes, including Section 1029, seek to curb illegal activities that cannot be successfully fought with just technology alone. So basically you need several tools in your bag of tricks to fight the bad guys—technology, knowledge of how to use the technology, and the legal system. The legal system will play the role of a sledgehammer to the head, which attackers will have to endure when crossing these boundaries.

Section 1029 addresses offenses that involve generating or illegally obtaining access credentials, which can involve just obtaining the credentials or obtaining and using them. These activities are considered criminal whether or not a computer is involved—unlike the statute discussed next, which pertains to crimes dealing specifically with computers.

18 USC Section 1030 of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) (as amended by the USA Patriot Act) is an important federal law that addresses acts that compromise computer network security. It prohibits unauthorized access to computers and network systems, extortion through threats of such attacks, the transmission of code or programs that cause damage to computers, and other related actions. It addresses unauthorized access to government, financial institutions, and other computer and network systems, and provides for civil and criminal penalties for violators. The act outlines the jurisdiction of the FBI and Secret Service.

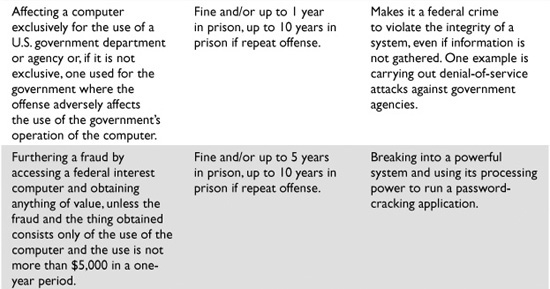

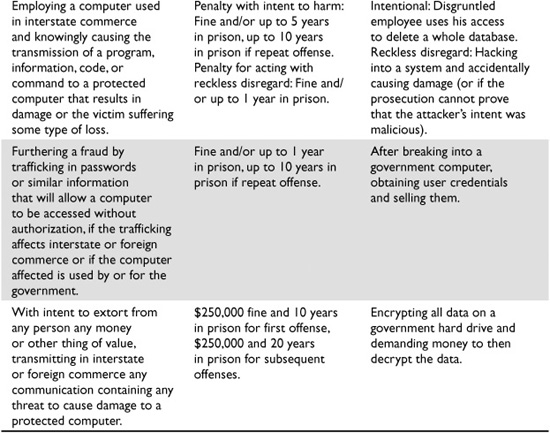

Table 2-2 outlines the categories of crimes that section 1030 of the CFAA addresses. These offenses must be committed knowingly by accessing a computer without authorization or by exceeding authorized access. You can be held liable under the CFAA if you knowingly accessed a computer system without authorization and caused harm, even if you did not know that your actions might cause harm.

Table 2-2 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act Laws

The term “protected computer,” as commonly put forth in the CFAA, means a computer used by the U.S. government, financial institutions, or any system used in interstate or foreign commerce or communications. The CFAA is the most widely referenced statute in the prosecution of many types of computer crimes. A casual reading of the CFAA suggests that it only addresses computers used by government agencies and financial institutions, but there is a small (but important) clause that extends its reach. This clause says that the law applies also to any system “used in interstate or foreign commerce or communication.” The meaning of “used in interstate or foreign commerce or communication” is very broad, and, as a result, CFAA operates to protect nearly all computers and networks. Almost every computer connected to a network or the Internet is used for some type of commerce or communication, so this small clause pulls nearly all computers and their uses under the protective umbrella of the CFAA. Amendments by the USA Patriot Act to the term “protected computer” under CFAA extended the definition to any computers located outside the United States, as long as they affect interstate or foreign commerce or communication of the United States. So if the United States can get the attackers, they will attempt to prosecute them no matter where in the world they live.

The CFAA has been used to prosecute many people for various crimes. Two types of unauthorized access can be prosecuted under the CFAA: These include wholly unauthorized access by outsiders, and also situations where individuals, such as employees, contractors, and others with permission, exceed their authorized access and commit crimes. The CFAA states that if someone accesses a computer in an unauthorized manner or exceeds his or her access rights, that individual can be found guilty of a federal crime. This clause allows companies to prosecute employees who carry out fraudulent activities by abusing (and exceeding) the access rights their company has given them.

Many IT professionals and security professionals have relatively unlimited access rights to networks due to their job requirements. However, just because an individual is given access to the accounting database, doesn’t mean she has the right to exceed that authorized access and exploit it for personal purposes. The CFAA could apply in these cases to prosecute even trusted, credentialed employees who performed such misdeeds.

Under the CFAA, the FBI and the Secret Service have the responsibility for handling these types of crimes and they have their own jurisdictions. The FBI is responsible for cases dealing with national security, financial institutions, and organized crime. The Secret Service’s jurisdiction encompasses any crimes pertaining to the Treasury Department and any other computer crime that does not fall within the FBI’s jurisdiction.

NOTE

The Secret Service’s jurisdiction and responsibilities have grown since the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was established. The Secret Service now deals with several areas to protect the nation and has established an Information Analysis and Infrastructure Protection division to coordinate activities in this area. This division’s responsibilities encompasses the preventive procedures for protecting “critical infrastructure,” which include such things as power grids, water supplies, and nuclear plants in addition to computer systems.

Hackers working to crack government agencies and programs seem to be working on an ever-bigger scale. The Pentagon’s Joint Strike Fighter Project was breached in 2009, according to a Wall Street Journal report. Intruders broke into the $300 billion project to steal a large amount of data related to electronics, performance, and design systems. The stolen information could make it easier for enemies to defend against fighter jets. The hackers also used encryption when they stole data, making it harder for Pentagon officials to determine what exactly was taken. However, much of the sensitive program-related information wasn’t stored on Internet-connected computers, so hackers weren’t able to access that information. Several contractors are involved in the fighter jet program, however, opening up more networks and potential vulnerabilities for hackers to exploit.

An example of an attack that does not involve government agencies but instead simply represents an exploit in interstate commerce involved online ticket purchase websites. Three ticketing system hackers made more than $25 million and were indicted in 2010 for CFAA violations, among other charges. The defendants are thought to have gotten prime tickets for concerts and sporting events across the U.S., with help from Bulgarian computer programmers. One important strategy was using CAPTCHA bots, a network of computers that let the hackers evade the anti-hacking CAPTCHA tool found on most ticketing websites. They could then buy tickets much more quickly than the general public. In addition, the hackers are alleged to have used fake websites and e-mail addresses to conceal their activities.

Worms and Viruses and the CFAA

The spread of computer viruses and worms seems to be a common occurrence during many individuals’ and corporations’ daily activities. A big reason for the increase in viruses and worms is that the Internet continues to grow at an unbelievable pace, providing attackers with new victims to exploit every day. Malware is becoming more sophisticated, and a record number of home users run insecure systems, which is just a welcome mat to one and all hackers. Individuals who develop and release this type of malware can be prosecuted under section 1030, along with various state statutes. The CFAA criminalizes the act of knowingly causing the transmission of a program, information, code, or command, without authorized access to the protected computer, that results in intentional damage.

In 2009, a federal grand jury indicted a hacker on charges that he transmitted malicious script to servers at Fannie Mae, the government-sponsored mortgage lender. As an employee, the defendant had access to all of Fannie Mae’s U.S. servers. After the hacker (a contract worker) was let go from Fannie Mae, he inserted code designed to move through 4,000 servers and destroy all data. Though the malicious script was hidden, another engineer discovered the script before it could execute.

In U.S. vs. Mettenbrink, a Nebraska hacker pled guilty in 2010 to an attack on the Church of Scientology websites. As part of the “Anonymous” group, which protests Scientology, the hacker downloaded software to carry out a DDoS attack. The attack shut down all of the church’s websites. The defendant was sentenced to a year in prison. The maximum penalty for the case, filed as violating Title 18 USC 1030(a)(5)(A)(i), is ten years in prison and a fine of $250,000.

Blaster Worm Attacks and the CFAA

Virus outbreaks have definitely caught the attention of the American press and the government. Because viruses can spread so quickly, and their impact grow exponentially, serious countermeasures have been developed. The Blaster worm is a well-known worm that has impacted the computing industry. In Minnesota, an individual was brought to justice under the CFAA for issuing a B variant of the worm that infected 7,000 users. Those users’ computers were unknowingly transformed into drones that then attempted to attack a Microsoft website. Although the Blaster worm is an old example of an instance of malware, it gained the attention of high-ranking government and law enforcement officials.

Addressing the seriousness of the crimes, then–Attorney General John Ashcroft stated,

The Blaster computer worm and its variants wreaked havoc on the Internet, and cost businesses and computer users substantial time and money. Cyber hacking is not joy riding. Hacking disrupts lives and victimizes innocent people across the nation. The Department of Justice takes these crimes very seriously, and we will devote every resource possible to tracking down those who seek to attack our technological infrastructure.

So, there you go, do bad deeds and get the legal sledgehammer to the head. Sadly, however, many of these attackers are never found and prosecuted because of the difficulty of investigating digital crimes.

The Minnesota Blaster case was a success story in the eyes of the FBI, Secret Service, and law enforcement agencies, as collectively they brought a hacker to justice before major damage occurred. “This case is a good example of how effectively and quickly law enforcement and prosecutors can work together and cooperate on a national level,” commented U.S. District Attorney Tom Heffelfinger.

The FBI added its comments on the issue as well. Jana Monroe, FBI assistant director, Cyber Division, stated, “Malicious code like Blaster can cause millions of dollars’ worth of damage and can even jeopardize human life if certain computer systems are infected. That is why we are spending a lot of time and effort investigating these cases.” In response to this and other types of computer crime, the FBI has identified investigating cybercrime as one of its top three priorities, just behind counterterrorism and counterintelligence investigations.

Other prosecutions under the CFAA include a case brought against a defendant who tried to use “cyber extortion” against insurance company New York Life, threatening to send spam to customers if he wasn’t paid $200,000 (United States vs. Digati); a case (where the defendant received a seven-and-a-half year sentence) where a hacker sent e-mail threats to a state senator and other randomly selected victims (United States vs. Tschiegg); and the case against an e-mail hacker who broke into vice-presidential nominee Sarah Palin’s Yahoo! account during the 2008 presidential election (United States vs. Kernell).

So many of these computer crimes happen today, they don’t even make the news anymore. The lack of attention given to these types of crimes keeps them off the radar of many people, including the senior management of almost all corporations. If more people were aware of the amount of digital criminal behavior happening these days (prosecuted or not), security budgets would certainly rise.

It is not clear that these crimes can ever be completely prevented as long as software and systems provide opportunities for such exploits. But wouldn’t the better approach be to ensure that software does not contain so many flaws that can be exploited and that continually cause these types of issues? That is why we wrote this book. We illustrate the weaknesses in many types of software and show how these weaknesses can be exploited with the goal of the motivating the industry to work together—not just to plug holes in software, but to build the software right in the first place. Networks should not have a hard shell and a chewy inside—the protection level should properly extend across the enterprise and involve not only the perimeter devices.

Disgruntled Employees

Have you ever noticed that companies will immediately escort terminated employees out of the building without giving them the opportunity to gather their things or say goodbye to coworkers? On the technology side, terminated employees are stripped of their access privileges, computers are locked down, and often, configuration changes are made to the systems those employees typically accessed. It seems like a coldhearted reaction, especially in cases where an employee has worked for a company for many years and has done nothing wrong. Employees are often laid off as a matter of circumstance, not due to any negative behavior on their part. Still, these individuals are told to leave and are sometimes treated like criminals instead of former valued employees.

Companies have good, logical reasons to be careful in dealing with terminated and former employees, however. The saying “one bad apple can ruin a bushel” comes to mind. Companies enforce strict termination procedures for a host of reasons, many of which have nothing to do with computer security. There are physical security issues, employee safety issues, and, in some cases, forensic issues to contend with. In our modern computer age, one important factor to consider is the possibility that an employee will become so vengeful when terminated that he will circumvent the network and use his intimate knowledge of the company’s resources to do harm. It has happened to many unsuspecting companies, and yours could be next if you don’t protect yourself. It is vital that companies create, test, and maintain proper employee termination procedures that address these situations specifically.

Several cases under the CFAA have involved former or current employees. A programmer was indicted on computer fraud charges after he allegedly stole trade secrets from Goldman Sachs, his former employer. The defendant switched jobs from Goldman to another firm doing similar business, and on his last day is thought to have stolen portions of Goldman Sachs’s code. He had also transferred files to his home computer throughout his tenure at Goldman Sachs.

One problem with this kind of case is that it is very difficult to prove how much actual financial damage was done, making it difficult for companies injured by these acts to collect compensatory damages in a civil action brought under the CFAA. The CFAA does, however, also provide for criminal fines and imprisonment designed to dissuade individuals from engaging in hacking attacks.

In some intrusion cases, real damages can be calculated. In 2008, a hacker was sentenced to a year in prison and ordered to pay $54,000 in restitution after pleading guilty to hacking his former employer’s computer systems. He had previously been IT manager at Akimbo Systems, in charge of building and maintaining the network, and had hacked into its systems after he was fired. Over a two-day period, he reconfigured servers to send out spam messages, as well as deleted the contents of the organization’s Microsoft Exchange database.

In another example, a Texas resident was sentenced to almost three years in prison in early 2010 for computer fraud. The judge also ordered her to pay more than $1 million in restitution to Standard Mortgage Corporation, her former employer. The hacker had used the company’s computer system to change the deposit codes for payments made at mortgage closings, and then created checks payable to herself or her creditors.

These are just a few of the many attacks performed each year by disgruntled employees against their former employers. Because of the cost and uncertainty of recovering damages in a civil suit or as restitution in a criminal case under the CFAA or other applicable law, well-advised businesses put in place detailed policies and procedures for handling employee terminations, as well as the related implementation of access limitations to company computers, networks, and related equipment for former employees.

Other Areas for the CFAA

It’s unclear whether or how the growth of social media might impact this statute. A MySpace cyber-bullying case is still making its way through appeal courts at the time of writing this book in 2010. Originally convicted of computer fraud, Lori Drew was later freed when the judge overturned her jury conviction. He decided her case did not meet the guidelines of CFAA abuse. Drew had created a fake MySpace account that she used to contact a teenage neighbor, pretending she was a love interest. The teenager later committed suicide. The prosecution in the case argued that violating MySpace’s terms of service was a form of computer hacking fraud, but the judge did not agree when he acquitted Drew in 2009.

In 2010, the first Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) hacking case was prosecuted against a man who hacked into VoIP-provider networks and resold the services for a profit. Edwin Pena pleaded guilty to computer fraud after a three-year manhunt found him in Mexico. He had used a VoIP network to route calls (more than 500,000) and hid evidence of his hack from network administrators. Prosecutors believed he sold more than 10 million Internet phone minutes to telecom businesses, leading to a $1.4 million loss to providers in under a year.

State Law Alternatives

The amount of damage resulting from a violation of the CFAA can be relevant for either a criminal or civil action. As noted earlier, the CFAA provides for both criminal and civil liability for a violation. A criminal violation is brought by a government official and is punishable by either a fine or imprisonment or both. By contrast, a civil action can be brought by a governmental entity or a private citizen and usually seeks the recovery of payment of damages incurred and an injunction, which is a court order to prevent further actions prohibited under the statute. The amount of damages is relevant for some but not all of the activities that are prohibited by the statute. The victim must prove that damages have indeed occurred. In this case, damage is defined as disruption of the availability or integrity of data, a program, a system, or information. For most CFAA violations, the losses must equal at least $5,000 during any one-year period.

This sounds great and may allow you to sleep better at night, but not all of the harm caused by a CFAA violation is easily quantifiable, or if quantifiable, might not exceed the $5,000 threshold. For example, when computers are used in distributed denial-of-service attacks or when processing power is being used to brute force and uncover an encryption key, the issue of damages becomes cloudy. These losses do not always fit into a nice, neat formula to evaluate whether they total $5,000. The victim of an attack can suffer various qualitative harms that are much harder to quantify. If you find yourself in this type of situation, the CFAA might not provide adequate relief. In that context, this federal statute may not be a useful tool for you and your legal team.

An alternative path might be found in other federal laws, but even those still have gaps in coverage of computer crimes. To fill these gaps, many relevant state laws outlawing fraud, trespass, and the like, which were developed before the dawn of cyberlaw, are being adapted, sometimes stretched, and applied to new crimes and old crimes taking place in a new arena—the Internet. Consideration of state law remedies can provide protection from activities that are not covered by federal law.

Often victims will turn to state laws that may offer more flexibility when prosecuting an attacker. State laws that are relevant in the computer crime arena include both new state laws being passed by state legislatures in an attempt to protect their residents and traditional state laws dealing with trespassing, theft, larceny, money laundering, and other crimes.

For example, if an unauthorized party accesses, scans, probes, and gathers data from your network or website, these activities may be covered under a state trespassing law. Trespass law covers not only the familiar notion of trespass on real estate, but also trespass to personal property (sometimes referred to as “trespass to chattels”). This legal theory was used by eBay in response to its continually being searched by a company that implemented automated tools for keeping up-to-date information on many different auction sites. Up to 80,000 to 100,000 searches and probes were conducted on the eBay site by this company, without eBay’s consent. The probing used eBay’s system resources and precious bandwidth, but was difficult to quantify. Plus, eBay could not prove that they lost any customers, sales, or revenue because of this activity, so the CFAA was not going to come to the company’s rescue and help put an end to this activity. So eBay’s legal team sought relief under a state trespassing law to stop the practice, which the court upheld, and an injunction was put into place.

Resort to state laws is not, however, always straightforward. First, there are 50 different states and nearly that many different “flavors” of state law. Thus, for example, trespass law varies from one state to the next, resulting in a single activity being treated in two very different ways under state law. For instance, some states require a demonstration of damages as part of the claim of trespass (not unlike the CFAA requirement), whereas other states do not require a demonstration of damages in order to establish that an actionable trespass has occurred.

Importantly, a company will usually want to bring a case to the courts of a state that has the most favorable definition of a crime so it can most easily make its case. Companies will not, however, have total discretion as to where they bring the case to court. There must generally be some connection, or nexus, to a state in order for the courts of that state to have jurisdiction to hear a case. Thus, for example, a cracker in New Jersey attacking computer networks in New York will not be prosecuted under the laws of California, since the activity had no connection to that state. Parties seeking to resort to state law as an alternative to the CFAA or any other federal statute need to consider the available state statutes in evaluating whether such an alternative legal path is available. Even with these limitations, companies sometimes have to rely upon this patchwork quilt of different non-computer-related state laws to provide a level of protection similar to the intended blanket of protection provided by federal law.

TIP

If you are considering prosecuting a computer crime that affected your company, start documenting the time people have to spend on the issue and other costs incurred in dealing with the attack. This lost paid employee time and other costs may be relevant in the measure of damages or, in the case of the CFAA or those states that require a showing of damages as part of a trespass case, to the success of the case.

A case in Florida illustrates how victims can quantify damages resulting from computer fraud. In 2009, a hacker pled guilty to computer fraud against his former company, Quantum Technology Partners, and was sentenced to a year in prison and ordered to pay $31,500 in restitution. The defendant had been a computer support technician at Quantum, which served its clients by offering storage, e-mail, and scheduling. The hacker remotely accessed the company’s network late at night using an admin logon name and then changed the passwords of every IT administrator. Then the hacker shut down the company’s servers and deleted files that would have helped restore tape backup data. Quantum quantified the damages suffered to come to the more than $30,000 fine the hacker paid. The costs included responding to the attack, conducting a damage assessment, restoring the entire system and data to their previous states, and other costs associated with the interruption of network services, which also affected Quantum’s clients.

As with all of the laws summarized in this chapter, information security professionals must be careful to confirm with each relevant party the specific scope and authorization for work to be performed. If these confirmations are not in place, it could lead to misunderstandings and, in the extreme case, prosecution under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act or other applicable law. In the case of Sawyer vs. Department of Air Force, the court rejected an employee’s claim that alterations to computer contracts were made to demonstrate the lack of security safeguards and found the employee liable, since the statute only required proof of use of a computer system for any unauthorized purpose. While a company is unlikely to seek to prosecute authorized activity, people who exceed the scope of such authorization, whether intentionally or accidentally, run the risk being prosecuted under the CFAA and other laws.

18 USC Sections 2510, et. Seq., and 2701, et. Seq., of the Electronic Communication Privacy Act

These sections are part of the Electronic Communication Privacy Act (ECPA), which is intended to protect communications from unauthorized access. The ECPA, therefore, has a different focus than the CFAA, which is directed at protecting computers and network systems. Most people do not realize that the ECPA is made up of two main parts: one that amended the Wiretap Act and the other than amended the Stored Communications Act, each of which has its own definitions, provisions, and cases interpreting the law.

The Wiretap Act has been around since 1918, but the ECPA extended its reach to electronic communication when society moved in that direction. The Wiretap Act protects communications, including wire, oral, and data during transmission, from unauthorized access and disclosure (subject to exceptions). The Stored Communications Act protects some of the same types of communications before and/or after the communications are transmitted and stored electronically somewhere. Again, this sounds simple and sensible, but the split reflects a recognition that there are different risks and remedies associated with active versus stored communications.

The Wiretap Act generally provides that there cannot be any intentional interception of wire, oral, or electronic communication in an illegal manner. Among the continuing controversies under the Wiretap Act is the meaning of the word “interception.” Does it apply only when the data is being transmitted as electricity or light over some type of transmission medium? Does the interception have to occur at the time of the transmission? Does it apply to this transmission and to where it is temporarily stored on different hops between the sender and destination? Does it include access to the information received from an active interception, even if the person did not participate in the initial interception? The question of whether an interception has occurred is central to the issue of whether the Wiretap Act applies.

An example will help to illustrate the issue. Let’s say I e-mail you a message that must be sent over the Internet. Assume that since Al Gore invented the Internet, he has also figured out how to intercept and read messages sent over the Internet. Does the Wiretap Act state that Al cannot grab my message to you as it is going over a wire? What about the different e-mail servers my message goes through (where it is temporarily stored as it is being forwarded)? Does the law say that Al cannot intercept and obtain my message when it is on a mail server?

Those questions and issues come down to the interpretation of the word “intercept.” Through a series of court cases, it has been generally established that “intercept” only applies to moments when data is traveling, not when it is stored somewhere permanently or temporarily. This gap in the protection of communications is filled by the Stored Communications Act, which protects this stored data. The ECPA, which amended both earlier laws, therefore, is the “one-stop shop” for the protection of data in both states—during transmission and when stored.

While the ECPA seeks to limit unauthorized access to communications, it recognizes that some types of unauthorized access are necessary. For example, if the government wants to listen in on phone calls, Internet communication, e-mail, network traffic, or you whispering into a tin can, it can do so if it complies with safeguards established under the ECPA that are intended to protect the privacy of persons who use those systems.

Many of the cases under the ECPA have arisen in the context of parties accessing websites and communications in violation of posted terms and conditions or otherwise without authorization. It is very important for information security professionals and businesses to be clear about the scope of authorized access provided to various parties to avoid these issues.

In early 2010, a Gmail user brought a class-action lawsuit against Google and its new “Google Buzz” service. The plaintiff claimed that Google had intentionally exceeded its authorization to control private information with Buzz. Google Buzz, a social networking tool, was met with privacy concerns when it was first launched in February 2010. The application accessed Gmail users’ contact lists to create “follower” lists, which were publicly viewable. They were created automatically, without the user’s permission. After initial criticism, Google changed the automatic way lists were created and made other changes. It remains to be seen how the lawsuit will affect Google’s latest creation.

Interesting Application of ECPA

Many people understand that as they go from site to site on the Internet, their browsing and buying habits are being collected and stored as small text files on their hard drives. These files are called cookies. Suppose you go to a website that uses cookies, looking for a new pink sweater for your dog because she has put on 20 pounds and outgrown her old one, and your shopping activities are stored in a cookie on your hard drive. When you come back to that same website, magically all of the merchant’s pink dog attire is shown to you because the web server obtained that earlier cookie it placed your system, which indicated your prior activity on the site, from which the business derives what it hopes are your preferences. Different websites share this browsing and buying-habit information with each other. So as you go from site to site you may be overwhelmed with displays of large, pink sweaters for dogs. It is all about targeting the customer based on preferences and, through this targeting, promoting purchases. It’s a great example of capitalists using new technologies to further traditional business goals.

As it happens, some people did not like this “Big Brother” approach and tried to sue a company that engaged in this type of data collection. They claimed that the cookies that were obtained by the company violated the Stored Communications Act, because it was information stored on their hard drives. They also claimed that this violated the Wiretap Law because the company intercepted the users’ communication to other websites as browsing was taking place. But the ECPA states that if one of the parties of the communication authorizes these types of interceptions, then these laws have not been broken. Since the other website vendors were allowing this specific company to gather buying and browsing statistics, they were the party that authorized this interception of data. The use of cookies to target consumer preferences still continues today.

Trigger Effects of Internet Crime

The explosion of the Internet has yielded far too many benefits to list in this writing. Millions and millions of people now have access to information that years before seemed unavailable. Commercial organizations, healthcare organizations, nonprofit organizations, government agencies, and even military organizations publicly disclose vast amounts of information via websites. In most cases, this continually increasing access to information is considered an improvement. However, as the world progresses in a positive direction, the bad guys are right there keeping up with and exploiting these same technologies, waiting for the opportunity to pounce on unsuspecting victims. Greater access to information and more open computer networks and systems have provided us, as well as the bad guys, with greater resources.

It is widely recognized that the Internet represents a fundamental change in how information is made available to the public by commercial and governmental entities, and that a balance must be continually struck between the benefits and downsides of greater access. In a government context, information policy is driven by the threat to national security, which is perceived as greater than the commercial threat to businesses. After the tragic events of September 11, 2001, many government agencies began to reduce their disclosure of information to the public, sometimes in areas that were not clearly associated with national security. A situation that occurred near a Maryland army base illustrates this shift in disclosure practices. Residents near Aberdeen, Maryland, had worried for years about the safety of their drinking water due to their suspicion that potential toxic chemicals were leaked into their water supply from a nearby weapons training center. In the years before the 9/11 attack, the army base had provided online maps of the area that detailed high-risk zones for contamination. However, when residents found out that rocket fuel had entered their drinking water in 2002, they also noticed that the maps the army provided were much different than before. Roads, buildings, and hazardous waste sites were deleted from the maps, making the resource far less effective. The army responded to complaints by saying the omission was part of a national security blackout policy to prevent terrorism.

This incident was just one example of a growing trend toward information concealment in the post-9/11 world, much of which affects the information made available on the Internet. All branches of the government have tightened their security policies. In years past, the Internet would not have been considered a tool that a terrorist could use to carry out harmful acts, but in today’s world, the Internet is a major vehicle for anyone (including terrorists) to gather information and recruit other terrorists.

Limiting information made available on the Internet is just one manifestation of the tighter information security policies that are necessitated, at least in part, by the perception that the Internet makes information broadly available for use or misuse. The Bush administration took measures to change the way the government exposes information, some of which drew harsh criticism. Roger Pilon, Vice President of Legal Affairs at the Cato Institute, lashed out at one such measure: “Every administration over-classifies documents, but the Bush administration’s penchant for secrecy has challenged due process in the legislative branch by keeping secret the names of the terror suspects held at Guantanamo Bay.”

According to the Report to the President from the Information Security Oversight Office Summary for Fiscal Year 2008 Program Activities, over 23 million documents were classified and over 31 million documents were declassified in 2005. In a separate report, they documented that the U.S. government spent more than $8.6 billion in security classification activities in fiscal year 2008.

The White House classified 44.5 million documents in 2001–2003. Original classification activity—classifying information for the first time—saw a peak in 2004, at which point it started to drop. But overall classifications, which include new designations along with classified information derived from other classified information, grew to the highest level ever in 2008. More people are now allowed to classify information than ever before. Bush granted classification powers to the Secretary of Agriculture, Secretary of Health and Human Services, and the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. Previously, only national security agencies had been given this type of privilege. However, in 2009, President Obama issued an executive order and memorandum expressing his plans to declassify historical materials and reduce the number of original classification authorities, with an additional stated goal of a more transparent government.

The terrorist threat has been used “as an excuse to close the doors of the government” states OMB Watch Government Secrecy Coordinator Rick Blum. Skeptics argue that the government’s increased secrecy policies don’t always relate to security, even though that is how they are presented. Some examples include the following:

• The Homeland Security Act of 2002 offers companies immunity from lawsuits and public disclosure if they supply infrastructure information to the Department of Homeland Security.

• The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) stopped listing chemical accidents on its website, making it very difficult for citizens to stay abreast of accidents that may affect them.

• Information related to the task force for energy policies that was formed by Vice President Dick Cheney was concealed.

• The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) stopped disclosing information about action taken against airlines and their employees.

Another manifestation of the Bush administration’s desire to limit access to information in its attempt to strengthen national security was reflected in its support in 2001 for the USA Patriot Act. That legislation, which was directed at deterring and punishing terrorist acts and enhancing law enforcement investigation, also amended many existing laws in an effort to enhance national security. Among the many laws that it amended are the CFAA (discussed earlier), under which the restrictions that were imposed on electronic surveillance were eased. Additional amendments also made it easier to prosecute cybercrimes. The Patriot Act also facilitated surveillance through amendments to the Wiretap Act (discussed earlier) and other laws. Although opinions may differ as to the scope of the provisions of the Patriot Act, there is no doubt that computers and the Internet are valuable tools to businesses, individuals, and the bad guys.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

The DMCA is not often considered in a discussion of hacking and the question of information security, but it is relevant. The DMCA was passed in 1998 to implement the World Intellectual Property Organization Copyright Treaty (WIPO Treaty). The WIPO Treaty requires treaty parties to “provide adequate legal protection and effective legal remedies against the circumvention of effective technological measures that are used by authors,” and to restrict acts in respect to their works that are not authorized. Thus, while the CFAA protects computer systems and the ECPA protects communications, the DMCA protects certain (copyrighted) content itself from being accessed without authorization. The DMCA establishes both civil and criminal liability for the use, manufacture, and trafficking of devices that circumvent technological measures controlling access to, or protection of, the rights associated with copyrighted works.

The DMCA’s anti-circumvention provisions make it criminal to willfully, and for commercial advantage or private financial gain, circumvent technological measures that control access to protected copyrighted works. In hearings, the crime that the anti-circumvention provision is designed to prevent was described as “the electronic equivalent of breaking into a locked room in order to obtain a copy of a book.”

Circumvention is to “descramble a scrambled work...decrypt an encrypted work, or otherwise...avoid, bypass, remove, deactivate, or impair a technological measure, without the authority of the copyright owner.” The legislative history provides that “if unauthorized access to a copyrighted work is effectively prevented through use of a password, it would be a violation of this section to defeat or bypass the password.” A “technological measure” that “effectively controls access” to a copyrighted work includes measures that, “in the ordinary course of its operation, requires the application of information, or a process or a treatment, with the authority of the copyright owner, to gain access to the work.” Therefore, measures that can be deemed to “effectively control access to a work” would be those based on encryption, scrambling, authentication, or some other measure that requires the use of a key provided by a copyright owner to gain access to a work.

Said more directly, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) states that no one should attempt to tamper with and break an access control mechanism that is put into place to protect an item that is protected under the copyright law. If you have created a nifty little program that will control access to all of your written interpretations of the grandness of the invention of pickled green olives, and someone tries to break this program to gain access to your copyright-protected insights and wisdom, the DMCA could come to your rescue.

When down the road, you try to use the same access control mechanism to guard something that does not fall under the protection of the copyright law—let’s say your uncopyrighted 15 variations of a peanut butter and pickle sandwich—you would get a different result. If someone were willing to extend the necessary resources to break your access control safeguard, the DMCA would be of no help to you for prosecution purposes because it only protects works that fall under the copyright act.

These explanations sound logical and could be a great step toward protecting humankind, recipes, and introspective wisdom and interpretations, but this seemingly simple law deals with complex issues. The DMCA also provides that no one can create, import, offer to others, or traffic in any technology, service, or device that is designed for the purpose of circumventing some type of access control that is protecting a copyrighted item. What’s the problem? Let’s answer that question by asking a broader question: Why are laws so vague?

Laws and government policies are often vague so they can cover a wider range of items. If your mother tells you to “be good,” this is vague and open to interpretation. But she is your judge and jury, so she will be able to interpret good from bad, which covers any and all bad things you could possibly think about and carry out. There are two approaches to laws and writing legal contracts:

• Specifying exactly what is right and wrong, which does not allow for interpretation but covers a smaller subset of activities.

• Writing a more abstract law, which covers many more possible activities that could take place in the future, but is then wide open for different judges, juries, and lawyers to interpret.

Most laws and contracts present a combination of more- and less-vague provisions, depending on what the drafters are trying to achieve. Sometimes the vagueness is inadvertent (possibly reflecting an incomplete or inaccurate understanding of the subject), whereas, at other times, the vagueness is intended to broaden the scope of that law’s application.

Let’s get back to the law at hand. If the DMCA indicates that no service can be offered that is primarily designed to circumvent a technology that protects a copyrighted work, where does this start and stop? What are the boundaries of the prohibited activity?

The fear of many in the information security industry is that this provision could be interpreted and used to prosecute individuals carrying out commonly applied security practices. For example, a penetration test is a service performed by information security professionals where an individual or team attempts to break or slip by access control mechanisms. Security classes are offered to teach people how these attacks take place so they can understand what countermeasures are appropriate and why. Sometimes people are hired to break these mechanisms before they are deployed into a production environment or go to market to uncover flaws and missed vulnerabilities. That sounds great: hack my stuff before I sell it. But how will people learn how to hack, crack, and uncover vulnerabilities and flaws if the DMCA indicates that classes, seminars, and the like cannot be conducted to teach the security professionals these skills? The DMCA provides an explicit exemption allowing “encryption research” for identifying the flaws and vulnerabilities of encryption technologies. It also provides for an exception for engaging in an act of security testing (if the act does not infringe on copyrighted works or violate applicable law such as the CFAA), but does not contain a broader exemption covering a variety of other activities that information security professionals might engage in. Yep, as you pull one string, three more show up. Again, you see why it’s important for information security professionals to have a fair degree of familiarity with these laws to avoid missteps.

An interesting aspect of the DMCA is that there does not need to be an infringement of the work that is protected by the copyright law for prosecution under law to take place. So, if someone attempts to reverse-engineer some type of control and does nothing with the actual content, that person can still be prosecuted under this law. The DMCA, like the CFAA and the Access Device Statute, is directed at curbing unauthorized access itself, not at protecting the underlying work, which falls under the protection of copyright law. If an individual circumvents the access control on an e-book and then shares this material with others in an unauthorized way, she has broken the copyright law and DMCA. Two for the price of one.

Only a few criminal prosecutions have been filed under the DMCA. Among these are:

• A case in which the defendant pled guilty to paying hackers to break DISH network encryption to continue his satellite receiver business (United States vs. Kwak).

• A case in which the defendant was charged with creating a software program that was directed at removing limitations put in place by the publisher of an e-book on the buyer’s ability to copy, distribute, or print the book (United States vs. Sklyarov).

• A case in which the defendant pled guilty to conspiring to import, market, and sell circumvention devices known as modification (mod) chips. The mod chips were designed to circumvent copyright protections that were built into game consoles, by allowing pirated games to be played on the consoles (United States vs. Rocci).

There is an increasing movement in the public, academia, and from free speech advocates toward softening the DCMA due to the criminal charges being weighted against legitimate researchers testing cryptographic strengths (see http://w2.eff.org/legal/cases/). While there is growing pressure on Congress to limit the DCMA, Congress took action to broaden the controversial law with the Intellectual Property Protection Act of 2006 and 2007, which would have made “attempted copyright infringement” illegal. Several versions of an Intellectual Property Enforcement Act were introduced in 2007, but not made into law. A related bill, the Prioritizing Resources and Organization for Intellectual Property Act of 2008, was enacted in the fall of 2008. It mostly dealt with copyright infringement and counterfeit goods and services, and added requirements for more federal agents and attorneys to work on computer-related crimes.

Cyber Security Enhancement Act of 2002

Several years ago, Congress determined that the legal system still allowed for too much leeway for certain types of computer crimes and that some activities not labeled “illegal” needed to be. In July 2002, the House of Representatives voted to put stricter laws in place, and to dub this new collection of laws the Cyber Security Enhancement Act (CSEA) of 2002. The CSEA made a number of changes to federal law involving computer crimes.

The act stipulates that attackers who carry out certain computer crimes may now get a life sentence in jail. If an attacker carries out a crime that could result in another’s bodily harm or possible death, or a threat to public health or safety, the attacker could face life in prison. This does not necessarily mean that someone has to throw a server at another person’s head, but since almost everything today is run by some type of technology, personal harm or death could result from what would otherwise be a run-of-the-mill hacking attack. For example, if an attacker were to compromise embedded computer chips that monitor hospital patients, cause fire trucks to report to wrong addresses, make all of the traffic lights change to green, or reconfigure airline controller software, the consequences could be catastrophic and under the CSEA result in the attacker spending the rest of her days in jail.

NOTE

In early 2010, a newer version of the Cyber Security Enhancement Act passed the House and is still on the docket for the Senate to take action, at the time of this writing. Its purpose includes funding for cybersecurity development, research, and technical standards.

The CSEA was also developed to supplement the Patriot Act, which increased the U.S. government’s capabilities and power to monitor communications. One way in which this is done is that the CSEA allows service providers to report suspicious behavior without risking customer litigation. Before this act was put into place, service providers were in a sticky situation when it came to reporting possible criminal behavior or when trying to work with law enforcement. If a law enforcement agent requested information on a provider’s customer and the provider gave it to them without the customer’s knowledge or permission, the service provider could, in certain circumstances, be sued by the customer for unauthorized release of private information. Now service providers can report suspicious activities and work with law enforcement without having to tell the customer. This and other provisions of the Patriot Act have certainly gotten many civil rights monitors up in arms. It is another example of the difficulty in walking the fine line between enabling law enforcement officials to gather data on the bad guys and still allowing the good guys to maintain their right to privacy.

The reports that are given by the service providers are also exempt from the Freedom of Information Act, meaning a customer cannot use the Freedom of Information Act to find out who gave up her information and what information was given. This issue has also upset civil rights activists.

Securely Protect Yourself Against Cyber Trespass Act (SPY Act)

The Securely Protect Yourself Against Cyber Trespass (SPY Act) was passed by the House of Representatives, but never voted on by the Senate. Several versions have existed since 2004, but the bill has not become law as of this writing.

The SPY Act would provide many specifics on what would be prohibited and punishable by law in the area of spyware. The basics would include prohibiting deceptive acts related to spyware, taking control of a computer without authorization, modifying Internet settings, collecting personal information through keystroke logging or without consent, forcing users to download software or misrepresenting what software would do, and disabling antivirus tools. The law also would decree that users must be told when personal information is being collected about them.

Critics of the act thought that it didn’t add any significant funds or tools for law enforcement beyond what they were already able to do to stop cybercriminals. The Electronic Frontier Foundation argued that many state laws, which the bill would override, were stricter on spyware than this bill was. They also believed that the bill would bar private citizens and organizations from working with the federal government against malicious hackers—leaving the federal government to do too much of the necessary anti-hacking work. Others were concerned that hardware and software vendors would be legally able to use spyware to monitor customers’ use of their products or services.

It is up to you which side of the fight you choose to play on—black or white hat—but remember that computer crimes are not treated as lightly as they were in the past. Trying out a new tool or pressing Start on an old tool may get into a place you never intended—jail. So as your mother told you—be good, and may the Force be with you.