CHAPTER 1

Healthcare Industry

This chapter covers Domain 1, “Healthcare Industry,” of the HCISPP certification. After you read and study this chapter, you should be able to:

• Understand the general organization of the United States healthcare system as well as select international healthcare delivery systems.

• Recognize the roles that make up the healthcare delivery system and how these interact with the information security professional.

• Understand the systems and taxonomies used to provide coding of healthcare information and to facilitate exchange of information in patient care delivery and payment.

• Be aware of the financial components of delivering and sustaining healthcare operations.

• Comprehend privacy and security aspects within health information management.

• Describe the information protection implications of third-party relationships in healthcare organizations.

• Appreciate the relationship between information privacy and security concepts with respect to foundational health data management approaches.

• Identify the standards and formats for data interoperability and exchange in clinical operations.

Over the past few decades, the complexity of a typical healthcare organization has increased. Beginning with the earliest hospitals and clinics, operations included direct patient care, hospitality, food service, janitorial, and engineering, to name a few ancillary functions. While those functions may be provided by third-party suppliers today, they are still imperative to caring for patients. Today, the complexity is increased as organizations form into integrated delivery systems where payers, providers, and other components are organized into one entity. This results in a very diverse workforce.

In many communities, the healthcare systems that reside in the area are primary employers or sources of income. This is important to know from a healthcare information protection perspective because the stakes are high and the organization must remain solvent. A data breach or cybersecurity event can erode trust or cause financial penalties that shift resources from patient care.

An extremely rich mixture of highly educated and talented physicians, nurses, administrators, and medical technicians provide direct and indirect patient care. Adding to the complexity, the numerous environments in which healthcare is delivered bring even more diversity to the categories of caregivers and support personnel that are necessary. Healthcare is delivered in hospitals, clinical offices, specialty diagnostic centers, and even the home. The challenges are equally complex for those of us who are charged with protecting the information privacy and security along with these medical professionals in the multitude of environments. One solution does not fit all scenarios to safeguard individually identifiable health information. This chapter will introduce and provide a brief overview of these categories of healthcare organization staff and their various qualifications.

Along with the complexity of the healthcare organizations, the reliance on third-party relationships has increased. This chapter presents an overview of the role and impact that third-party organizations play in healthcare. From suppliers of services to emerging technologies that augment employed staff and increase capabilities, the healthcare organization has many external relationships. A significant number of these are considered critical to operations. Relationships can be established by contracts, partnerships, or subsidiaries to the organization. It becomes interesting when the third party serves multiple industries, with healthcare being only one of them. Cloud service providers are a great example of a third party that has become integral to healthcare organizations. The growing pains for both sides have provided learning examples.

We will start with an introduction to the types of third-party relationships and related services on which healthcare organizations depend. Later, we will focus on the management processes available to address third-party–supplier risk to the healthcare organization.

Types of Organizations in the Healthcare Sector

From the origins of sanitariums and spas, which were more like warehouses for the sick and dying, our modern healthcare system has evolved rapidly into a very complex, highly technical, and essential component of communities and public health. Healthcare is less about a place than a process today. It can be delivered in hospitals, homes, and via mobile phones. Patients expect access to care in multiple settings and on-demand. Providers’ expectations and demands are increasingly decentralized, digital, and instantaneous. Those who work in the healthcare sector understand the current reality of what a healthcare organization can be, compared to what a healthcare organization was only two or three decades ago.

Let’s start with an overview of the major participants in the delivery of healthcare, which involves distinct groups: patients, providers, payers, and external stakeholders (such as suppliers, regulators, and the surrounding community). These groups play key roles that distinguish them from others even as the point of care may evolve.

Patients

No discussion about healthcare and healthcare information security and privacy starts without an acknowledgment of the patient. In the simplest terms, the patient is why we do what we do. A patient is a person who seeks assistance with matters of health (physical and mental), improvement of health status, or treatment of illness. The care patients seek can be preventative in nature, interventional, rehabilitative, or in recovery from a previous incident.

People can serve different roles on behalf of a patient. Proxies and advocates often assist the patient in navigating the provider and payer systems. These individuals may be family members, members of volunteer organizations, or commercial business entities. The key point is that these entities act primarily on behalf of the patient because the patient care system is complex, or the individual patient needs assistance to participate in their care. The central transaction in healthcare is the conversation between provider and patient. We protect information to ensure that the interchange is complete, protected, and maintained for all the different, legitimate uses of the information.

A patient can have an inpatient or an outpatient status. An inpatient is administratively admitted to the healthcare organization for 24 hours or more. In these cases, a bed is traditionally the unit of measure for occupancy rates. For periods of less than 24 hours, the patient is considered in outpatient status. Outpatient status is also known as ambulatory. In some cases, a patient may be admitted in an observation status, which can last up to 48 hours without formal admission as an inpatient. Many patients enter the healthcare system through the emergency department. Typically, the admission status of these patients is determined once they are stabilized. For example, a patient who visits an emergency room is considered an outpatient status if the patient is released within 24 hours.

Outpatient care is provided in numerous types of healthcare settings, including hospitals, medical clinics, associated facilities, and even their own home environments. Increasingly, many surgical and treatment procedures are safe and possible outside of the traditional hospital setting. Advances in technology have reduced the need for inpatient admissions. This evolution has fostered changes in where care can be provided. Today you can find urgent care centers in shopping centers, and patients can undergo some surgical procedures outside a hospital facility. This evolution has been fostered by changes in favorable regulatory guidance and reimbursement rules.

The patient can also be viewed through the lens of the data that constitutes a healthcare facility’s identity. This is important, because a protecting a patient’s identifiable information is significantly different from information protection and other security and privacy concerns applicable and important in other industries. For example, a patient can be identified by his or her name, date of birth, Social Security number, or home address. These identifiers are similar across other data collection activities of personally identifiable information (PII). However, patients can also have unique information referencing genetic code, billing codes, treatment codes, and images, to name just a few data elements. If PII is disclosed in an unauthorized manner or to an unauthorized viewer, the disclosure violates patient privacy and can also be used to fraudulently receive medical services or alter a medical record. Such disclosure can be a problem in terms of identity theft, financial impact to a patient and a provider organization, and patient safety.

Compounding the issue is that, unlike PII, most protected health information (PHI) is difficult to change (if not impossible) if it has been corrupted or misused in some way. For example, a bank account or even a Social Security number can be replaced, although the unauthorized disclosure of this information is a problem. The disclosure of a patient’s medical history, however, is far more difficult to remedy. If the information is spoofed by someone in order to fraudulently receive healthcare services, the actual patient will have difficulty fixing the problem. In some cases, the imposter receives care, and that care is integrated into the victim’s medical record. The addition of this information could result in patient safety and care issues (such as blood type mismatches, drug interactions, and so on). If certain diagnoses such as mental health issues or highly sensitive diseases are disclosed, that element of privacy and confidentiality cannot be regained or remedied.

Providers

“Provider” is a broad term that may refer to a single healthcare provider, such as a physician, nurse, or therapist who helps in identifying, preventing, or treating an illness or injury. The term can also describe an organization that employs, contracts, or organizes people who deliver services to patients. Various types of organizations deliver healthcare as providers, such as hospitals, specialized clinics, and even home healthcare agencies. As mobile applications and cloud-based technologies become more advanced, virtual healthcare provider organizations are emerging. In these virtual organizations, caregivers are linked with patients without regard to geographic location. The technology platform is the healthcare organization. By 2022, the virtual healthcare market in the United States is anticipated to earn revenues of $3.5 billion.1

When multiple types of provider organizations, both inpatient and outpatient services, are organized into a coordinated system of clinics and hospitals, they are called integrated delivery systems. These systems can be organized into a single corporate structure, or the systems can provide care, services, or supplies under terms of contracts and other legally binding agreements. The systems are established to increase efficiency and reduce redundancy in providing quality healthcare.

At this point, you know the central transaction in healthcare. The interaction between provider and patient is foundational to the entire system. Understanding the fundamental importance of patient-provider communications can help guide information security professionals. Our role is to look for solutions that improve the communications while maintaining security. At the same time, we must avoid actions that negatively impact the physician-patient interactions.

If you walk into any provider organization, you will notice a wide variety of occupations involved. There are people performing roles ranging from janitorial services to open-heart surgery. There are teams cleaning rooms and others delivering babies. People perform clinical, administrative, or support services to care for patients. The variety of occupations and different levels of education and competency that exist in healthcare differentiates the healthcare industry from many other industries. The US government identifies almost 50 different categories of healthcare practitioners, technologists, and healthcare support occupations.2 This is in addition to the numerous business and information technology types of professionals that constitute the healthcare organization workforce that must work together efficiently and effectively. From the lowest skilled, entry-level employee to the most senior executive or seasoned physician, the entire organization works in an interconnected way to provide patient care. The following sections cover several of the major categories of healthcare organization occupations you should know about.

Nurses

Nursing is the largest occupational category in any healthcare provider organization. Nursing staff serve a variety of roles and responsibilities, and more than half of US nurses work in provider organizations. In the United States, almost 3.5 million nursing professionals are in the workforce today, accounting for nearly three of every five healthcare professional and technical jobs in the country.3 Nurses are a professional category of caregiver, with many countries requiring specific education and licensing requirements. Although there are millions of nurses in the workforce, the demand for nursing remains unmet. Presently, there may be as many as 200,000 unfilled nursing jobs in the United States, primarily because of the lack of nursing educators and education resources. In 2018, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing reported that US nursing schools turned away more than 75,000 qualified applicants from baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs because of an insufficient number of faculty, clinical sites, classroom space, and clinical preceptors, as well as budget constraints.4 General categories of nursing include nurses’ aides, licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and nurse practitioners.

Nurses are essential and influential in the delivery of healthcare. They have impressive levels of education, training, and certification and are indispensable in every aspect of clinical workflow. Beyond direct patient care, nurses are also invaluable when serving in administrative and executive functions of the healthcare business. In the healthcare industry, nurses are prominent in the exam room as well as in the board room. Nursing professionals are highly sought after, and many nurses serve in areas outside of direct patient care. Nurses working in health education roles, in privacy and security areas, and in data analytics are not uncommon.

Nurses’ Aides Nurses’ aides provide a great deal of patient care in a variety of healthcare settings from the physician’s office, to the hospital, to long-term care environments. As an occupation that is related to hospital orderlies and attendants, nurses’ aides perform services that include moving, repositioning, and lifting patients. They may also provide numerous patient services related to personal care, feeding, bathing, comforting patients, and keeping patients at ease. The education level of most nurses’ aides is post-high school (a diploma or certificate). It is not uncommon for healthcare organizations to require at least a competency exam that the nurses’ aide also needs to pass.

Registered Nurses and Certified Registered Nurses The care that registered nurses (RNs) provide is more directly involved in coordinating with physicians and other healthcare providers. Whether in an emergency room (ER) or an intensive care unit (ICU), RNs are working at the front lines of patient care. RNs also have a large role in educating patients and the public about health status, post-discharge instructions, and a variety of other concerns related to healthcare. Of course, RNs work in the same environments as all other nurses, but because of their additional education, training, and credentialing, RNs can work independently in some nontraditional healthcare environments such as correctional facilities, schools, and summer camps. Most commonly, RNs receive a bachelor’s degree in nursing. It is possible, however, to obtain RN licensure with an associate degree in nursing or a diploma from select nursing programs. All RNs must obtain a license by passing a national RN licensing exam.

An advanced registered nursing career track is the certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). These nurses can provide anesthesia to patients for any surgery or procedure that requires it. Whereas this responsibility was previously reserved for physicians, CRNAs enable small-market and rural hospitals to control costs by reducing staffing expense while maintaining the standard of care. To become a CRNA, the process includes obtaining a bachelor’s degree in nursing or an equivalent, often obtaining a master of science degree in nursing (MSN), and being a licensed RN. Additionally, a CRNA must have clinical experience in an acute care setting. They need to demonstrate one year of experience in an area such as the ICU as opposed to long-term care or rehabilitation units. In addition to all this, they also must complete an accredited nurse anesthesia educational program. Finally, they are required to pass a national certification examination.

A second example of an advanced registered nurse specialty is the certified nurse midwife (CNM). This nurse usually has completed a bachelor’s degree and an MSN program. The board certification is in the profession of midwifery. CNMs specialize in providing care such as birthing services for women who are not experiencing high-risk pregnancies.

Nurse Practitioners Within the nursing profession, the role of nurse practitioner (NP) has emerged to extend and expand the capabilities of caregivers due to workforce shortages and advances in medicine. RNs may undergo additional training to be able to diagnose medical conditions, order treatment, prescribe drugs, and make referrals much as a physician would. To become an NP, one must first be an RN. Then, after additional, advanced classroom and clinical education, the RN is credentialed as an NP. The types of practices in which NPs work are almost limitless. They serve in primary care settings such as pediatrics, family practice, and geriatrics and in specialty care areas such as OB/GYN, oncology, dermatology, and pain management.

To become an NP, the RN must obtain an MSN or the doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree. Then the candidate must pass a national board certification exam. The NP will take the exam based on the specific clinical focus area of their educational program—in other words, if the program concentrated on geriatrics, the certification exam would do the same. Once these hurdles are cleared, the board-certified NP can apply for additional credentials, such as a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) registration number to be able to prescribe controlled substances in addition to the medications the NP licensing allows.

Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses A licensed practical nurse (LPN) or a licensed vocational nurse (LVN) works under the supervision of an RN. The choice of occupational title depends on the US state in which the nurse is employed. The duties and qualifications are the same for LPN and LVN. These nurses must complete a year-long (typically) certified educational program. Often these programs are affiliated with a teaching hospital that provides some hands-on experience for the students. After they complete the program, students must pass an additional licensing exam. LPNs and LVNs work in every area of healthcare provision—in hospitals, of course, but they also may provide care in skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, or even a patient’s home. Through home healthcare, the continuum of care extends from the hospital back into the patient’s normal living environment, which has a demonstrated positive impact on outcomes.

Physicians

Physicians have been providing healthcare since as far back as time has been recorded. Hippocrates, in around 350 BC, is considered the “father of modern medicine.”5 In contrast, modern nursing began in the nineteenth century—although the services of nursing in patient care have certainly taken place as long as people have been sick and injured.

From the very beginning to today, the central relationship in healthcare has been between the doctor and the patient. A physician’s main role is to diagnose and treat injuries and illnesses for their patients. Surgeons, who are a specialized type of physician, treat patients by operating to treat injuries, diseases, and deformities. Almost all physicians obtain a bachelor’s degree and then complete four more years in an accredited medical school. There has always been a measure of importance placed on applied performance under the guidance of a current physician. So, after medical school, on-the-job training continues as an intern for a year. Then the student must complete a residency, usually focusing on a specialty or area of increased proficiency, such as cardiology or internal medicine.

Like a nurse, a doctor must obtain a license to practice and hold the credential of doctor of medicine (MD) or doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO). It is also common for MDs and DOs to take additional exams for board certification. There are board certifications (sometimes more than one) for all the various specialties. After training and licensing is completed, physicians are permitted to prescribe medications and order, perform, and interpret diagnostic tests independently. In addition, each physician is also required to be credentialed specifically to practice in a particular hospital or healthcare organization. This is an internal function of the healthcare organization. Organization personnel verify the background and qualifications of the physician and grant the physician privileges to practice medicine within the organization.

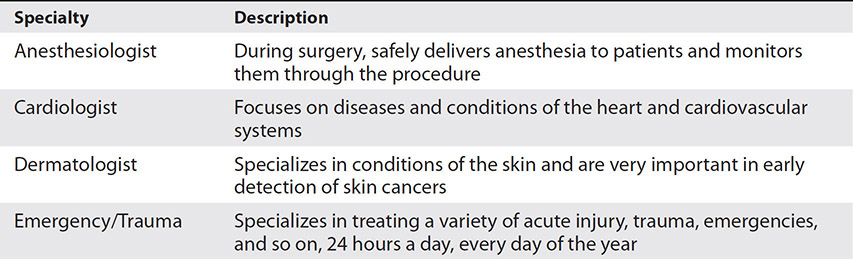

As mentioned, a physician can be a general practitioner with responsibilities in family medicine, internal medicine, or other primary care types of areas. Otherwise, based on additional, focused training and experience, physicians and surgeons (called specialists) can concentrate on an individual disease or condition, or on a specific physiologic system. To help illustrate the number and variety of these specialties, Table 1-1 contains some of the most common specialties with a brief description. The specializations listed in Table 1-1 are not comprehensive. There is variation internationally as countries may differ in how they subdivide and recognize specialty practices. The common factor for determining specialization, however, is according to the defined group of patients, diseases, skills, or philosophy on which the physician focuses.

Table 1-1 List of Specialist Physicians with Descriptions

Physician Assistants

The physician assistant (PA) is another provider role that has evolved separately by broadening the nursing role. Collectively, the NP, CRNA, and PA are often called “physician extenders” because they have absorbed traditional roles and responsibilities reserved for physicians to help increase the availability of advanced care. Physician extenders have also proven invaluable by often improving quality (certainly not lessening it), reducing costs, and increasing access. The PA is recognized as another general category of healthcare professional or staff who also has a license to practice medicine under the guidance of a physician. This recognition is not universal across international health systems. Primarily a US healthcare physician extender, the PA may not be recognized in other countries.

Most often, a candidate for PA already has a bachelor’s degree, but some programs confer one as part of completing the PA curriculum. In any case, PA programs typically require approximately two to three years of schoolwork with clinical rotations in all areas of PA practice, such as internal medicine, family practice, emergency medicine, and so on. In some cases, a graduating PA decides to specialize in a specific clinical area and obtains additional training and experience. This process is similar to physicians gaining experience through specialty rotations but involves a much shorter length of time. PAs provide the same patient care functions as a physician, but they must work under the direction and oversight of a physician. One difference is in performing surgery: a PA can aid a physician-surgeon but cannot conduct the surgery independently. As with all nurses and physicians, there is a licensing requirement for PAs.

Medical Technicians

When you hear someone referred to as a medical technician, it is similarly overarching, like doctor or nurse. There are numerous subcategories of medical technicians that fully describe the expertise and technical aptitude of any particular area. First, the general category of medical technician describes the kind of work done in clinical laboratories performing tests and exams. A medical technician has practical knowledge and ability in a particular clinical area. They also must be able to understand medical data produced by their specific equipment and how it relates to the patient. They are the first line of interpreters of results. While they do not make diagnoses, they can certainly reduce error and rework when they recognize inaccuracies in data, such as in a blood bank or microbiology laboratory. Another type of medical technician operates medical devices in support of performing procedures in the specific clinical practice. This would include diagnostic imaging, cardiac catheterization, and hemodialysis. The reports and findings of tests and examinations made by all of these different types of medical technicians are used by physicians to diagnose and treat patients. It is important to note that even with sophisticated testing technologies and highly skilled medical technicians, the actual interpretations and diagnoses remain the role of the physician.

Biomedical Technicians and Clinical Engineers Biomedical technicians and clinical engineers are the personnel who maintain (and operate) medical devices. One of the key differences between these types of medical technicians and the technicians discussed in the preceding section is that biomedical technicians and clinical engineers typically do not require extensive training on human anatomy, physiology, and clinical technique. With respect to education, clinical engineers have an educational requirement that exceeds that for a biomedical technician, including a four-year degree at least. A biomedical technician, much like other medical technicians, may have a two-year degree or a certificate of training from a healthcare vocational training program. In any case, both clinical engineers and biomedical technicians work in conjunction with other medical technicians to operate and maintain all of the various medical devices and technologies safely in the healthcare organization.

Other Provider Types with Specific Access

Based on how they provide clinical services to the patient, several other healthcare providers and support personnel handle protected health information. All the following providers require varying levels of licensure and certification requirements as well. Some jurisdictions internationally still require physicians to serve in these roles.

• Emergency medical technicians EMTs require special training to provide first response to emergency situations and handle traumatic injuries and medical care at accident scenes and other locations.

• Social workers This profession concentrates on patients’ quality of life and subjective wellbeing and administer to individuals, groups, and communities. Areas of practice include research, counseling, crisis intervention, and teaching.

• Psychologists A medical professional, they provide patient care with respect to behavior and mental processes and counselling services, and they may conduct research within academic settings.

• Psychiatrists An MD that focuses on examining and treating disorders of the mind or mental health. They can prescribe medication. Their evaluation of the patient consists of a consideration of symptoms and complaints to determine if the origin is physical illness or injury, mental disorders, or a combination.

• Pharmacists These professionals are responsible for dispensing medications and ensuring their proper and safe use. They are an integral part of the healthcare team in that they often provide meaningful education and counseling for patients who are receiving medication. A doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degree from an accredited pharmacy program is required. This is followed by successfully passing licensure exams.

Administration

No healthcare organization could succeed without another significant part of the healthcare workforce—the administration. There are many examples of providers who perform administrative roles in the organization, such as chief medical officer physicians or department managers who started their careers as medical technologists. However, many administrative positions are held by people not trained as providers but with education and experience focused on clerical, managerial, and executive competencies.

Administration describes all the various people that administratively support the provision of healthcare. At every level of the healthcare organization, from the chief executive officer to the ward clerk, administrative individuals provide appropriate levels of management and leadership. At the most senior level, administration refers to the management of internal and external forces to achieve specific goals. One of the key responsibilities for senior administrators is to recruit and retain quality physicians, to ensure appropriate staffing levels, and to manage performance. Below this level, the administration strives to achieve their objectives and allocate resources appropriately. Much like all the other healthcare professions, administrators can have a general focus across many areas, such as a chief operating officer or a physician’s office manager. On the other hand, many administrators specialize in a given area, such as information technology or finance.

In terms of education and training, the path to administrative positions mirrors that of other healthcare professions and categories. For more senior-level positions, at least a bachelor’s degree is needed. In many cases, especially in a specialty area such as information technology or finance, a graduate degree is often preferred. It is also preferred that administrators in these positions have previous experience working in healthcare organizations. For other administrative positions, a combination of a high school diploma and on-the-job training is required. Board certification is available to administrators of all types, from general administrators, to information technology, to finance. The certification of administration personnel provides a common framework for peer-to-peer relationships with healthcare provider colleagues.

Environmental Services

Without janitorial or housekeeping services, a healthcare organization could not open its doors. The regulatory and patient safety issues that healthcare organizations face make environmental concerns very important, especially because these types of services, including maintenance, alterations, and construction, happen in areas where patients are or will be.

Environmental service personnel also provide laundry operations and linen distribution. Coupled with housekeeping services, these personnel integrate in the overall management of beds within the organization. How quickly a room or a bed can be made ready after a patient is discharged can mean significant added revenue, but if this is done incorrectly, patient safety, satisfaction, and outcomes can suffer because rooms are transitioned quickly, but they lack cleanliness, for example. Infection control plays a large role and can be a huge revenue drain on healthcare organizations considering the number of hospital-acquired infections and readmissions that can result from a lack of proper cleanliness.

Healthcare Clearinghouse

A medical claims clearinghouse is a third-party system that interprets or “scrubs” claim data between US provider systems and private insurance payers. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, a healthcare clearinghouse is a “public or private entity, including a billing service, repricing company, or community health information system, which processes non-standard data or transactions received from one entity into standard transactions or data elements, or vice versa.”6 The electronic claims submission clearinghouse intermediates between provider financial charges and insurers’ denial or acceptance of the claims for payment. Providers can submit bills directly to health insurers, but many choose to deal with clearinghouses in the middle to increase efficiency. Healthcare clearinghouses are subject to HIPAA and have an important role in addressing information privacy and security during electronic data interchanges.

Healthcare Organizational Behavior

Now that we have discussed the healthcare players and their roles, let’s briefly look at how they interact (and why that matters to us). In short, you will want to acknowledge the power and politics in healthcare organizations. As noted in the specific professions, these roles have long histories, and their relationships and interactions have been influenced by political factors as well as clinical practices. Before the mid-twentieth century, the predominant healthcare roles were doctors and nurses. The relationship between the two professions is so intense that a Wisconsin physician, Leonard Stein, famously coined the term “Doctor-Nurse Game” in 1967 to help explain and understand the relationship. The major (and not complimentary) objectives of the game demonstrate the underlying communication problems between doctors, nurses, and, by extension, all allied health professions.7 Some debate that the game has ended as nursing professions have advanced in status and power within healthcare organizations, but others are not ready to declare that victory.8

The evolution of the healthcare workforce has led to complex organizational behavior dynamics. The need for a variety of allied healthcare professions, such as specialized medical technicians and myriad administrative personnel, came from the reliance on and success of clinical and information technology. Healthcare organizations must now more than ever work together.

The connection between organizational behavior and understanding information protection in healthcare is about knowing your customer. The healthcare organization is unlike any other customer or end user a security professional will serve. The interaction of nurses, physicians, administration, and medical technicians consists of multiple perspectives and priorities. Healthcare security professionals must take it all into account with respect to protecting information. You cannot apply information privacy and security in healthcare exactly as it is applied in other critical infrastructure organizations, such as telecommunications or industrial control system industries. To understand why is to master the power and politics at play.

We’ve established that healthcare starts with the patient, and the central relationship in healthcare is the doctor–patient relationship. Anything that interferes with that relationship must be clinically reasonable (and legally defensible). A successful healthcare information security and privacy practitioner must account for this. For instance, installing the latest vulnerability update for an operating system considered a critical fix is a top priority in most organizations with information systems. The edict to stop work and push out the patch remotely from information technology servers may well be the industry best practice. But in healthcare, that edict may interfere with patient care and can cause patient safety issues. Remember that medical devices are increasingly networked and will require the same vulnerability updates. Imagine what would happen if an automatic push across the organization caused a cardiac catheterization lab system to reboot in the middle of a patient procedure; patient safety could be at risk. (This is one over-simplified example.)

Safely implementing health information technology and security is already identified as a potential issue in healthcare-adverse events (those related to patient safety).9 The key concept is that a healthcare organization chart, a seniority list, or a corner office will not always illustrate the power within the healthcare organization. When developing and implementing an information protection strategy, you must consider and include input from physicians (who may or may not be employees of the organization), nurses, and anyone else who is providing direct patient care.

Health Insurance

Whether healthcare is funded by a public source, such as the government, or reimbursed by private entities, such as health insurers, someone has to pay the bill for services rendered. Both in the United States and internationally, it is uncommon for an individual to “self-pay,” so most payers are commonly described as third parties. In sum, a payer is almost always someone other than the patient who finances or reimburses the cost of healthcare.

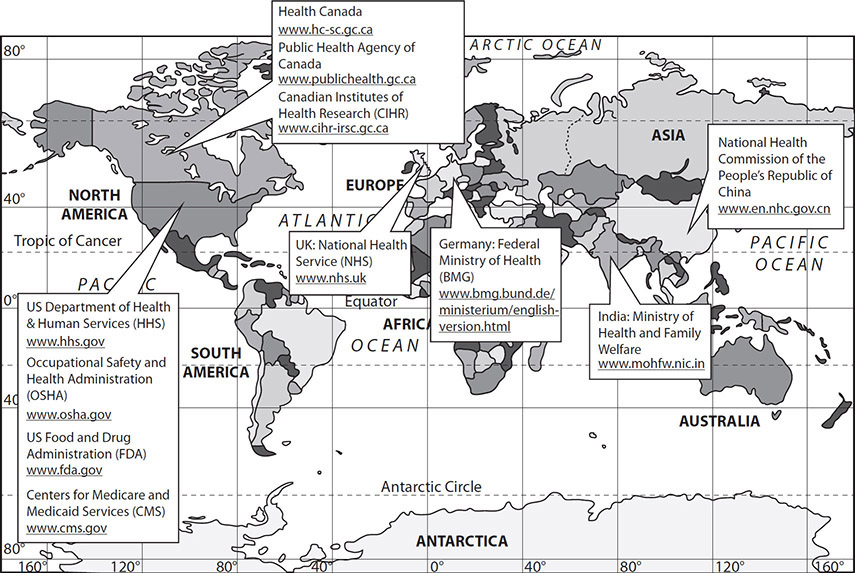

Healthcare Across the Globe

Healthcare delivery has patients, providers, and payers in every model in countries around the world. To highlight this, we present several major healthcare systems. Our starting point is the US healthcare system. You will observe a contrast with the US private and public payers with the rest of the global healthcare delivery systems. As a security professional, you are not expected to have a deep understanding of international healthcare systems; a high-level understanding of major components is enough. You may begin to put privacy and security issues into context based on knowing who pays for healthcare and how providers are regulated. There is intentionally no evaluation of one delivery system over another in this book; each has its own merits and opportunities for improvement.

United States

The US healthcare system consists of both private payers and public insurers. What sets the United States apart from the rest of the world is the extent to which healthcare costs are met by private payers, or health insurance companies. Health insurance is a way for individuals to be protected against large medical expenses by joining a larger population where the risk of medical expenses is estimated for the entire group. The insurance company charges a monthly premium applicable to the entire target population. In this way, the costs of medical care are spread out across the group. Under the heading of “private payer,” several considerations are described in the following sections.

Indemnity Insurance

This model for insurance payment is based on fee-for-service. A patient receives healthcare services, pays for it at the point of care, and then submits a claim to the insurance company for reimbursement. In this scenario, the patient has the maximum freedom of choice in physicians and other services. Of course, this scenario also results in the highest cost. Indemnity plans usually have an out-of-pocket maximum. Once the beneficiary reaches their annual limit for medical expenses, the insurer pays the entire bill. There is no patient payment for services unless the provider charges more than the usual and customary fee. The patient will be responsible for charges above that amount.

Employer-Based Insurance

The reliance on health insurance in the United States is a relatively recent development. The growth can be directly traced to employers offering coverage as an employment benefit, in addition to salary and other enticements. This may be related to federal government’s regulatory pressures to freeze wages during World War II. Employer-based healthcare became increasingly common as a result. Employer-based coverage comes in two types: fully insured plans and self-funded plans. Each version has legal and tax incentives for both employers and employees. The US Census Bureau reported that, in 2015, about 67 percent of the population was covered by private health insurance, and about 56 percent of that group was covered by employer-based health insurance.10 Figure 1-1 depicts the narrative in the next few paragraphs of US healthcare expenditures by payer type: self-pay, private insurance, Medicare and Medicaid, and other (third-party payers such as non-custodial parental support, state workers compensation, court settlements from a liability insurer, and so on).

Figure 1-1 Distribution of US healthcare expenditures in 2018, by payer (Source: Office of the Actuary in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services)

Fully Insured Health Plans In this type of fee-for-service plan, the employer purchases government-licensed insurance that is regulated at the state level depending on the states in which the insurer operates. The federal government has jurisdiction as well. The insurance company collects premiums and bears the financial risk if what the company pays out goes beyond the collected premiums.

There are three primary types of government-licensed health insurance organizations:

• Commercial health insurers In some cases, these companies, called indemnity insurers, may be owned by stockholders or policyholders (as a mutual insurance company). Aetna is an example of a stock company version of a commercial health insurer.

• Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans (BCBS) About 90 million people are covered by a BCBS plan. Traditionally, they were not-for-profit plans, and many still are today. Some BCBS have organized to be more like commercial, for-profit entities under special state laws by state hospital (Blue Cross) and state medical (Blue Shield) associations. Most plans offer managed care plans, such as health maintenance organization (HMO) and preferred provider organization (PPO) plans, as well as traditional insurance plans.

• Health maintenance organizations HMOs cover approximately 70 million people today. HMOs usually are licensed under special state laws that recognize that HMOs tightly integrate health insurance with the provision of healthcare. HMOs are both provider and payer. Examples include Kaiser Permanente and Harvard Pilgrim.

Self-Funded Employee Health Benefit Plans In these plans, the employer has the responsibility of paying directly for healthcare services. Funds are reserved to pay claims, and the employer contracts with one or more third parties to administer the insurance benefits. With a self-funded plan, the employer bears most of the financial risk. The employer can contract with an entity called a third-party administrator that specializes in this business. The other options are to contract with health insurers or HMOs to manage the benefits for the employer.

Managed Care

As a mechanism to control cost, improve quality, and increase access, managed care has evolved from an unproven concept almost 50 years ago to a major component of healthcare delivery and resourcing today. The key feature of managed care is in the integration of healthcare provision and payment within one organization. Virtually all private health coverage now involves some aspect of managed care. The managed care organization develops financial incentives to drive patient behavior and provider treatment decisions. At the same time, the managed care organizations rely on objective data analysis to develop treatment protocols that are shared to improve provider practices. Although also intended to control costs and increase efficiency, managed care organizations rely on controlling access to limit waste. Part of this process is a requirement for patients and referring providers to obtain prior authorizations for certain services. Some argue the gatekeeping function of referral management and prior authorizations can be an intrusion into the patient–provider relationship.

The following are the four main types of managed-care options:

• Health maintenance organization Patients are enrolled by paying the HMO a monthly or annual fee. They are then eligible to receive care from providers that have aligned with the HMO. The patient typically has a low or no deductible, but instead a small copayment for each service.

• Preferred provider organization This is a fee-for-service health plan with several providers that have aligned with the PPO. If the patient chooses a participating provider, the cost of medical care is discounted to the enrollee. If not, the health plan pays a lower amount for the provider’s service and the patient pays the rest. The patient may incur higher deductibles and coinsurance payments with a PPO. The result is more choice for the patient, yet at a higher cost.

• Point-of-service (POS) This type of plan combines the most attractive elements of both HMOs and PPOs. In exchange for a deductible and higher coinsurance payment on a one-time basis, an HMO enrollee can choose to use a service that is outside the HMO plan. This is in contrast to a strict HMO policy of not reimbursing care received out of network (under the HMO-only model).

• High-deductible health plan with savings option (HDHP/SO) This type of plan usually takes the form of a health savings account (HSA). For a relatively low premium, an enrollee gets catastrophic insurance coverage. For all healthcare received up to catastrophic care, the enrollee must pay a high deductible. To offset this, enrollees are able to save wages before tax in a special type of account to be used to pay any deductibles.

The government is the primary payer in most developed countries and is integral to the overall provision of healthcare. In contrast to other countries, government spending for healthcare in the United States is designed to address populations not served by private insurance. These government-sponsored plans are also typically structured in a managed-care design:

• Medicaid Each US state allocates the money it receives from the federal government to provide medical assistance primarily to the elderly, poor, and disabled. For the most part, recipients are pregnant women, children and babies, people with disabilities, and, in some cases, the elderly poor.

• Medicare Medicare provides insurance coverage for individuals age 65 and older or those who are younger than 65 but have long-term disabilities. It is funded and administered by the federal government. There is no qualification related to income level, only age or disability status.

• Department of Defense Military Health System (MHS) The federal government provides funding for health benefits for active-duty service members and retired service members, as well as their dependents, through the MHS. This network has aspects of direct care (military hospitals) but also purchases healthcare from the commercial sector through a managed-care network called TRICARE.

• Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Veterans of US military service are eligible for care through the federal VHA program, which operates a network of hospitals and treatment centers that provide care specifically to this population.

• Indian Health Service (IHS) Eligible Native Americans may receive care through the IHS within IHS facilities. They may also receive care at non-IHS facilities with payment provided by the federal government.

Depending on what services are covered and the level of reimbursement, many Americans pay premiums for more than one health insurance plan. Often plans overlap. For this reason, healthcare financing in the United States is a complex assortment of programs that can be integrated. A significant concern with the financing system is that it leaves still millions of Americans with too little or no health insurance coverage.

To address the uninsured and underinsured in America, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) was enacted in 2010. The law is often abbreviated to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or nicknamed “Obamacare.” The ACA was the most significant reform of US healthcare since Medicare and Medicaid were started in 1965.11 The exact numbers are hard to obtain, but sources indicate that more than 20 million people have benefitted from the regulatory reform, about half of the estimated population without insurance or enough coverage. The ACA continues to be a hotly debated political topic, even though it was passed into law. Several unsuccessful attempts were made to challenge the act in US courts. Another source of concern is that some studies showed that premiums paid by individuals increased dramatically post-implementation. Figure 1-2 offers a state-by-state view of the changes in how much an individual must pay annually. The sweeping nature of the ACA will continue to drive ongoing changes in the structure and financial operation of healthcare organizations in the United States.

Figure 1-2 Premium growth after ACA (2015–2016) (Source: Business Insider)12

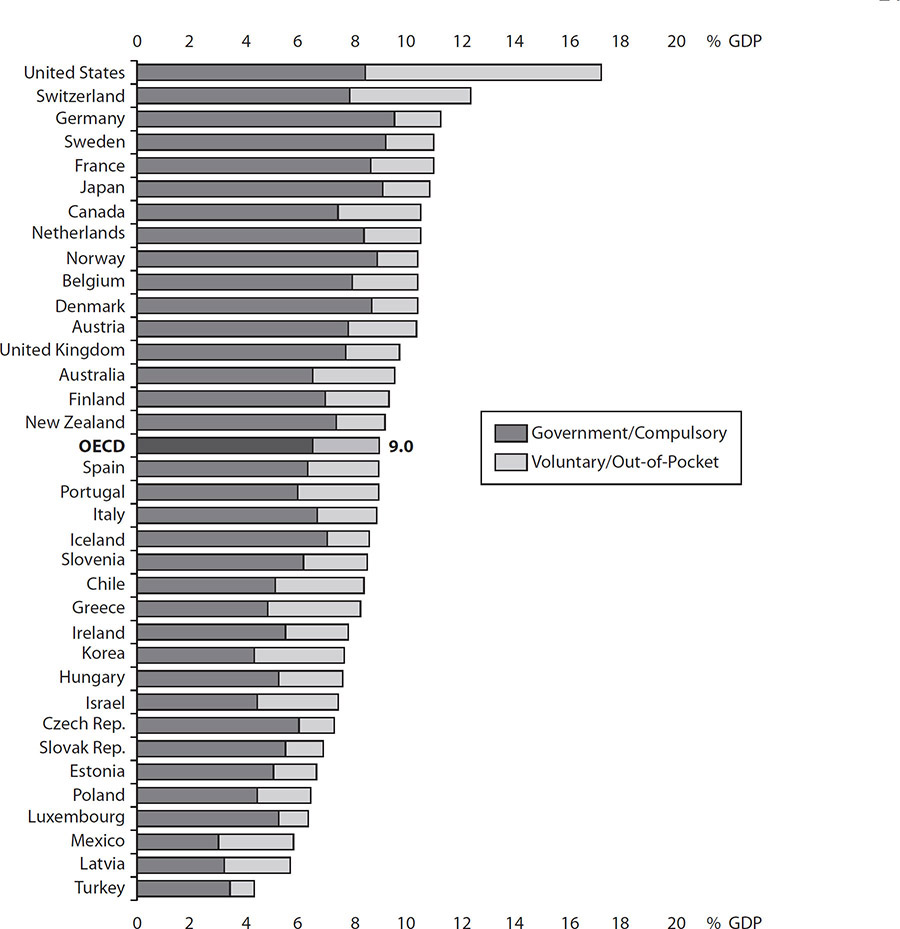

Internationally, a single-payer system financed by government (public) funds is most common. However, private insurance or self-pay options do exist for some countries. Depending on the country or healthcare system, providers may be able to choose to accept both private and public funds. In some systems, the two types of financing sources operate separately. A select few of those systems are presented in the following sections. Common among these, the government (with few exceptions) collects all healthcare fees and pays all healthcare costs. In short, providers in these countries bill one entity (not the patient) for their services. It is important to understand the financing systems for healthcare delivery on an international level compared as a percentage of each country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Figure 1-3 is authored by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and demonstrates overall spending by government and private sources on healthcare.

Figure 1-3 Health spending in OECD countries, 2016 (Source: Health at a Glance 2017, OECD Indicators)

Canada

Canada’s healthcare system is an example of a single-payer system in which the government offers universal coverage. The system is funded through taxes collected. The physicians delivering the care, however, are not government employees and provide services under a fee-for-service model. Canada has a publicly funded Medicare system, with most services provided by the private sector. In this single-payer system, basic services are provided by private doctors (since 2002 private doctors have been allowed to incorporate), who submit claims to the government (payer) for services rendered. The entire fee is paid by the government at the same rate. Each province may opt out of the program, though none currently does.

To be compliant with government mandates, all health plans in Canada must be

• Available to all residents of Canada

• Comprehensive in coverage

• Accessible without financial and other barriers

• Portable within the country and while traveling

• Publicly administered

United Kingdom

The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) is a government agency that is organized and resourced to provide universal health coverage. NHS is publicly funded via taxes and is founded on the belief that all citizens have an entitlement to healthcare. Healthcare services include basic services, primary care, specialty care, and inpatient care, along with radiology and laboratory services. That said, private insurance also exists because some types of services are not covered by NHS—usually elective conditions. Approximately seven million people, or 12 percent of the population, are covered by private plans.

In terms of out-of-pocket costs, there are only a few cost-sharing arrangements for publicly covered services. Patients may pay a prescription drug copayment per prescription, while all drugs prescribed for inpatient care in NHS hospitals are free to the patient. NHS dentistry services are also subject to copayments.

European Union

The European Union (EU) does not have any administrative or authoritative role in healthcare. Although each health system is run at an individual member-nation level, the systems are primarily publicly funded through taxation. For the most part, healthcare in the EU is considered universal healthcare. This includes larger systems in Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. There is private funding for healthcare, which is a personal contribution toward meeting anything not funded by taxpayer contribution. This can be totally private funds paid either out-of-pocket or by personal- or employer-funded insurance. Membership in the EU enables citizens to carry a European health insurance card and provides reciprocal emergency healthcare funding for citizens who are visiting other member nations. In fact, this benefit extends to several other European nations that are not currently in the European Union.

Japan

There is measurably more government control of healthcare in Japan, which also has a universal health coverage model. At a national level, in this model, the pricing of services is set by the government, which also subsidizes local governments, third-party payers, and providers for the cost of providing healthcare (which does not actually equal what the government sets as a fee). The government does this to help these entities implement national-level policies. Japan has 47 prefectures (regions) and 1742 municipalities that operate the nation’s healthcare system. However, all of these local healthcare entities adhere to detailed regulations set and enforced at a national level. Although funding is provided by the government, there are gaps in coverage; for instance, some hospitalization costs are not fully covered. Therefore, supplementary private health insurance is held by most of the adult population.

Stakeholders

The healthcare information protection practitioner may require an understanding of the broad impacts of negative events, such as a cybersecurity attack, that can affect entities beyond the healthcare organization. These entities, or stakeholders, have an interest in or an impact on the healthcare organization, and they are also affected by events that occur within the healthcare organization. Stakeholders can be many and diverse, from individuals to entire corporations.

Healthcare organizations are critical to the infrastructure of communities. In many communities, the local healthcare organization is probably one of the central institutions in the area and is likely a major employer as well. It is also likely that it is one of the most prevalent buyers and users of services, supplies, and products that are either directly related to patient care or indirectly related to supporting patient care operations.

Local government is also considered a stakeholder, because it has a direct impact on operations in the healthcare organization and is also responsive to things that happen with the facility. In other words, for example, a hospital that shuts down a service such as the emergency room and institutes an alternative care strategy may impact local public administration and policy.

Coding and Classification Systems and Standards

Coding is the transformation of clinical workflow from any type of description in narrative or words into numerical data sets, or codes, that are used for documenting disease descriptions, injuries, symptoms, and conditions. Think of coding in healthcare as a form of translation, from language to numbers. There are many reasons this translation has to be done. One of the most important reasons is the amount of information that is found in healthcare information stores like medical records and billing reports. Using codes to standardize and organize helps providers describe the care they deliver. The translation also assists reimbursement and data surveillance activities by creating and using a taxonomy that contains common meaning.

Related to the use of codes, classification systems facilitate the terminology and taxonomy to be further organized for ease of use. Some of the leading examples of classification systems, such as DRGS and ICD-10, are described in this section. Because the terminology of diagnosis and treatment is so complex, classification systems bridge the gaps in understanding what clinical information means.

The compilation of codes and classification systems culminates in various standards for the common formats and definitions for important data. With all of the complexity between healthcare information technologies, interoperability and systems integration depend on sharing information and collaboration. Standards for the data include rules and procedures that organizations must adopt to share the information appropriately and efficiently. HIPAA is an example of a large set of standards meant to secure and control information exchanges of PHI.

Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG)

A DRG is a classification system used for quality of care and reimbursement matters. It is the basis of the US healthcare system reimbursement under Medicare plans. Patients are classified using DRGs, which helps to identify and organize the types of patients and conditions a healthcare organization treats into cohorts of common diagnoses, also known as a case mix. The DRG classification system can standardize the costs incurred by a provider, which influences billing and reimbursements. The following components are used to determine case mix as defined by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS):

• Severity of illness A measure of the mortality or incapacity for a patient with a specific disease.

• Prognosis A prediction of the likely outcome of a diagnosis. Included in the prognosis is any probability for changes in severity, positive or negative. Prognosis also consists of an estimate of the patient’s quality of life and estimated chances for survival.

• Treatment difficulty Consideration for the complexity or inability for a provider to accurately provide prognosis when examining a patient. The case mix considers the problems that result in treatment including the need to care for the patient very closely until more certainty is obtained.

• Need for intervention The possible outcomes if no intervention to the illness happens.

• Resource intensity Based on a specific illness, the amount of diagnostic, therapeutic, and bed services that are needed to properly treat the patient.

DRGs are designed to replace reimbursement based on fee-for-service billing with the Prospective Payment System (PPS), which uses DRGs and predetermined reimbursement rates for hospitals for services and treatment of specific conditions and to help determine prospective payment rates. There are more than 500 DRG classifications—for example, hernia procedures for a patient age 0 to 17 and fracture of femurs are two examples of DRG classifications. Within a DRG, services and processes should be similar and standard across any group of patients with a particular condition. Adjustments are made for the hospital’s case mix, as mentioned earlier, which is a way to account for differences in consumption of resources. Provider organizations are expected to adjust practice patterns to reduce variations that have minimal, if any, demonstrated clinical value. The provider assumes risk for any additional costs that exceed the DRG rate.

Because of concerns with PPSs, other arrangements have been formulated. For example, because of claims that hospitals were discharging patients too early because of DRG guidelines, financing mechanisms known as bundled payments emerged. In this model, payers and providers share risk at a more episodic level or per clinical case, tailoring the reimbursements to a specific patient care experience. Another example of a compromise between fee-for-service and lump-sum DRG reimbursements is Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). In the ACO model, a willing coalition of physicians, healthcare organizations, and other provider groups agree to work together to deliver high-quality care and share financial risk for a common group of patients. ACOs were endorsed by the ACA, and CMS administers the reimbursement program. The ACO is a fee-for-service model, but the use of quality indicators and cost-savings approaches are rewarded with financial incentives such as bonuses for providers.

International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, commonly abbreviated to ICD, is the foremost and most widely known hierarchal medical classification system. It is managed under the purview of the World Health Organization (WHO) to categorize diseases so that morbidity and mortality rates can be tracked and reported. The use of ICD codes—14,000 in total—is significant in the digitization of healthcare records and electronic record systems.

For example, code 382.9 is used for “unspecified otitis media,” a disorder characterized by inflammation, swelling, and redness in the middle ear. Instead of having to provide all that verbiage, medical billers can communicate the details of the diagnosis for the purposes of payment with a simple number up to six digits long that is internationally understood. Beyond facilitating the reimbursement of healthcare services, standardized codes make data analysis possible by providers and payers alike. ICD classifications of diagnoses and procedures are also suited for output reporting to regulators and for data analysis functions, where data aggregation is advantageous. The resource use and quality of healthcare can be improved by using ICD codes and data analytics to reduce unnecessary tests and services, and health status outcomes can be obtained and compared.

CMS mandated ICD-10 (tenth revision) adoption in the United States as of October 2015. However, because of concerns about the amount of codes, complexity, and cost of implementation, the United States uses a modified version of ICD-10. Published as “ICD-10 Clinical Modification” (ICD-10-CM) and a procedural classification called “ICD-10 Procedure Coding System” (ICD-10-PCS), these variations were developed by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). In 2019, WHO approved ICD-11, which will go into effect in January 2022.

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT)

Another type of coding standard prevalent in healthcare is SNOMED CT. This is a repository of healthcare terms that is multilingual so it can be used worldwide. It facilitates a capability called semantic interoperability, which is important to the connection of SNOMED CT content to ICD-10, along with other coding standards. The repository contains over 311,000 discrete elements that are used to support accurate coding, retrieval, and analysis to comprehensively support clinical practices.

SNOMED CT is designed for the electronic exchange of clinical health information and is a required standard in the US Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) for certification of health information technology (health IT). A key use of SNOMED CT is to create interoperability between electronic health records (EHRs). In contrast to ICD, SNOMED CT is specifically used to describe extensive clinical terminology that is meant more as machine language to construct the EHR. ICD codes are useful for outputs such as medical billing and reporting in public health surveillance. SNOMED CT is a detailed terminology framework of concepts, descriptions, and relationships that works better for developing inputs into healthcare systems, which resemble data flow diagrams or flowcharts. Efforts are underway to integrate SNOMED CT and ICD, possibly when the ICD-11 standard is published.

Additional Coding Systems

Several other coding systems and standards have complementary or specific uses in healthcare. The following sections provide an introductory view of several that serve an administrative and clinical purpose for classification of payment, treatment, and healthcare operations. These may also be imperative for the continued digitization of healthcare information.

Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC)

LOINC is a widely accepted coding system specially formulated for identifying laboratory and clinical observations. To be able to exchange observations and measurements electronically across multiple independent lab systems, LOINC uses a universal code system with a maximum field size of seven characters. This results in more than 71,000 LOINC values, which enable data transfer among providers, clinical laboratories, and public health authorities.

Ambulatory Patient Group (APG)

This classification system is used in outpatient services reimbursement. Hospitals may use it for emergency room care that does not become an inpatient admission. Otherwise, the system is used in settings such as same-day surgery clinics and primary care offices. It classifies patients into more than 300 outpatient services. The purpose of the APG system is to outline the resources required to provide necessary care. It is analogous to DRG, which classifies inpatient services.

Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC)

APC is mainly a US coding system that is used for Medicare reimbursement. It is applicable only to hospitals and is used as an outpatient prospective payment system. As the DRG system is used to bill inpatient services, when an emergency room or hospital-based service does not lead to a patient admission, outpatients services are billed to Medicare using the APC system. The APC system accounts for every resource used in the outpatient visit. The standard is being considered for wider use in US states under Medicaid reimbursement as well as some private third-party insurers.

Resource Utilization Groups (RUG)

These are commonly used in US long-term care or skilled nursing facilities reimbursed by Medicare and Medicaid. The RUG system consists of categories that reflect levels of resource needs to facilitate risk adjustment and complexity of care factors specific to long-term care. The primary use is for insurance billing purposes. There are 44 classifications that describe variables affecting care, such as patient status and the care needed by activity levels, underlying illnesses, the complexity of the care, and patient cognitive status.

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT)

The CPT system is used by all US healthcare payers and providers to document and report medical, surgical, radiology, laboratory, anesthesiology, and evaluation and management (E/M) services. The CPT is a five-character code that supports reimbursement by listing services provided. The initial version was published by the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1966, and the codes are updated every year. The rules for assigning CPT codes are complex, and there can be variation in how much a provider is reimbursed based on the accuracy and completeness of CPT coding. There are three categories of CPT codes:

• Category I Numeric codes that start at 00100 and end at 99499 and describe a healthcare service and procedure.

• Category II Alphanumeric codes that assist with measuring clinical performance if used. They are not mandatory.

• Category III Provisional codes used to track emerging technology, procedures, and services.

National Drug Code (NDC)

As required by the US Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), drug products are assigned a unique code—an NDC—that is ten or eleven digits in three distinct segments. The codes and corresponding drug identifications are listed in a repository called the NDC Directory, which is maintained by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The information in the NDC Directory is updated every day and is used worldwide to identify specific products and sizes by manufacturer. Not every drug has a corresponding NDC; only those that are submitted to the directory and marketed for human use.

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS)

The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) is used much like the ICD system to accomplish medical coding. HCPCS (nicknamed “hick picks”) is an outpatient system used to ensure that hospital procedures and physician services are reported and processed in an orderly and consistent manner. (The ICD system is used in some outpatient scenarios, but all inpatient coding.) There are two levels of HCPCS codes. Level 1 codes are, in essence, CPT codes which, as explained earlier, describe products and services healthcare providers deliver. Level 2 codes are used for additional procedures and materials that are not included in Level 1 codes. Examples of items included in Level 2 codes are medical equipment, medical devices, or medical transport.

Revenue Cycle

An understanding of the financial components of healthcare delivery may help you better understand and build security cost–benefit analyses in your organization. The revenue cycle in healthcare includes billing, payment, and reimbursement. Without attention to resource allocation and fair compensation for healthcare services, these services would not happen—at least they would not happen to the extent that the healthcare system of today would have state-of-the-art technology, highly trained professionals, and well-apportioned facilities available.

Claims Processing and Third-Party Payers

If a third party is the payer for healthcare services, claims processing comes into play. For example, in a simplified patient-provider transaction, the provider may charge $100 for a service, and the patient may pay a $25 copay. The remainder of the bill, $75, is sent to the third-party payer as a claim against the insurance or government reimbursement.

The claims process actually begins prior to the patient’s appointment. Preapproval is often required, in which the third-party payer must authorize the doctor visit, all or a portion of the services, and any of the recommended follow-up care. Without preapproval, third-party payers can reduce the amount of reimbursement owed, or they may even deny the claim. The patient would then become fully responsible for paying the bill in its entirety.

With preapproval, the normal process for claims would include the physician sending the bill (after copay) to the third-party claims-processing center. Although providers can submit claims manually on paper forms, they more commonly file the claims electronically. Estimates show that electronic claims are three times less expensive than submitting via paper. However, securing the electronic transaction is a concern for healthcare information privacy and security. The claims-processing center compares the patient information and any relevant documentation of the services provided to the explanation of benefits (the policy terms and conditions). Once the third party determines all preapproved services were delivered and covered in the policy, it will submit payment for the remaining balance to the physician.

Payment Models

In the healthcare revenue cycle, claims processing leads to payment or reimbursement for services. The models for these payments have distinct features. In the dominant model, fee-for-service, providers are paid for each service rendered to a patient. This model is used in managed-care plans or when a government payer is involved. Without reiterating how those models work, variations of the fee-for-service model exist and should be understood by healthcare employees. These are discussed in the following sections.

Bundled Payment

Bundled payment is a more predetermined payment model than fee-for-service. In this model, a healthcare provider is compensated based on expected costs for each acute-care episode, not necessarily the actual costs. The parameters of the event, however, are determined by clinical judgment. The episode must have a clear beginning and end, require defined services, and have established clinical guidelines that allow for best practices. Conditions such as cataract surgery, services for end-stage renal disease, and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) to improve blood flow to the heart are bundle payment candidates. Bundled payments are central to any healthcare reform debate (in the United States) because of their ability to help reduce healthcare costs, and they are championed by physicians and administrators alike.

Capitation

An even more predetermined compensation model, capitation is a payment arrangement of a set amount for each person covered by the third-party payer. Providers agree in advance to accept a capitated amount, which is a fixed and predetermined payment amount for each person, based on a specified time period in which that person seeks care. A common way to describe this is “per member, per month” system for the provisions of capitation and coverage to which a healthcare provider agrees. To be clear, capitation does not relate to a specific episode of care or event, like fee-for-service and bundled payments. The average expected amount of care for each member that the payer disburses is calculated, and the payer enlists providers that agree to accept this payment. Providers accept a level of risk that they will be able to provide adequate care at some funding amount less than the capitated amount to therefore make a profit. If the amount of care exceeds the capitated amount, the provider takes the loss for excess spending—even if the care was clinically necessary.

The US Evolving Payment Model

Even with alternatives to fee-for-service, additional models of payment (sometimes discussed as part of healthcare reform in the United States) are worth mentioning. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) and the accountable-care organization (ACO) models are presented here.

In the PCMH model, patient treatment is coordinated by a primary-care manager who makes sure the patient receives appropriate levels of care. This can mean that clinically necessary referrals to specialists or diagnostic tests are vetted by the primary-care manager. As they are approved, these treatments, tests, and referrals are explained to the patient to reduce confusion and help increase the likelihood of patient compliance. Confusion and lack of patient compliance are issues that increase waste and redundancy.

PCMH has a goal of building a relationship for the benefit of the patient that includes physicians, selected family members, and the patient. There is a high degree of integration of information technology and health information exchange (requiring privacy and security considerations). All of these attempt to provide the right care at the right time at the best value from both the perspective of the patient and the provider (healthcare organization).

Physicians, hospitals, and other relevant health service professionals are testing a model that joins them together contractually to provide a broad set of healthcare services. This is an ACO, which is formally organized and applicable currently to Medicare patients only. Even though the ACO may not consist of organizations within the same corporate structure, the intent is to deliver seamless, coordinated care. In fact, as the name states, within the framework of the ACO contract, this organization is accountable to providing such care.

The payment model in healthcare must change from fee-for-service to something more efficient and effective. Churning out services for chronic diseases without regard to improving outcomes can no longer be reimbursed. An ACO (and the PCMH) model strives to improve quality and reduce hospital admissions (and readmissions) and emergency-room visits. In return, costs are contained, and the participating providers can share in the savings.

Medical Billing

An important component of the healthcare revenue cycle, medical billing is how healthcare providers initiate the process for payment. A claim is generated based on the services and products provided and a medical billing professional sends the payment request to payers, typically a healthcare insurance company, the government, or the individual. Providers may employ a couple different strategies in submitting their bills (or claims for payment). Depending on the size of the provider organization, larger practices tend to submit bills electronically to the payer. In smaller practices, it is more common for the forms to be completed on paper. Because the analog data must be converted to digital before submission, an entity called a clearinghouse receives these paper forms from multiple small practices, converts them to digital files, and submits them to the various payers.

A clearinghouse is not a healthcare provider; it is an entity that works in the middle of the transaction between a healthcare provider and whomever is providing payment or reimbursement. The clearinghouse function is not limited to changing paper-based information to digital. It also serves to improve handling claims and revenue collection of the provider by simplifying the process. For a small practice, having most, if not all, bills rejected because the data fields do not conform to the payers’ proprietary format can cause significant financial distress, maybe even bankruptcy. Clearinghouses can serve a significant role in increasing efficiency and reducing errors.

Assuming the data elements are all present and in the correct formatting, another hurdle that providers must overcome in the billing process is medical necessity. Payers review bills to make sure the patient was covered and the services were a medical necessity. The guidelines for medical necessity are established by different state agencies and even by each payer, but all should be located in the federal Medicare statute, which outlines what is reasonable and necessary. In the event a service is deemed not a medical necessity, the claim is denied or rejected, and the provider is notified, usually in the form of explanation of benefits (EOB) or electronic remittance advice (ERA), which also explains why the claim was returned unpaid.

It is clear that in the United States, medical billing is a complex process with almost countless payers and oft-changing regulations. Many argue that this results in measurable additional administrative waste generated in the healthcare system. The administrative burden is necessary, however, and securing these transactions starts with understanding the importance of the interconnections.

Transaction Standards