CHAPTER 2

Information Governance in Healthcare

This chapter covers Domain 2, “Information Governance in Healthcare,” of the HCISPP certification. After you read and study this chapter, you should be able to:

• Comprehend the general categories of information governance frameworks

• Differentiate between privacy and security governance components

• Recognize key information governance roles and responsibilities

• Understand the main information security and privacy policies, standards, and procedures

• Recognize and follow a code of conduct or code of ethics as a healthcare information protection professional

The implementation of information governance in an organization is meant to establish and manage clearly defined principles for acceptable behavior for information collection, use, and disposal. The governance process exists to provide structure to help the organization measure good information handling practices as well as manage oversight of any violations. The bottom line is this: governance is the foundation of an organization’s comprehensive and proactive approach toward security and privacy efforts protecting information assets. As an HCISPP, you are expected to understand and be able to support (sometimes establish) the organization’s information governance framework of structure, policies, procedures, and standards.

The need for information governance is established by leading information protection regulations in many countries. Some prominent examples are the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Organizations that have sufficient information governance structures in place for security and privacy functions tend to comply with these regulatory requirements more effectively. Adherence to the information protection guidance through information governance can assist in maintaining high-quality standards for information handling and in maintaining information confidentiality, integrity, and availability.

Governance is applicable across the entire enterprise and filters down to each individual department. A key outcome of a good governance function is to impose accountability for the management of information assets. There should be an alignment between information governance and the organization’s clinical and business strategies. Information governance, when applied, should guide an organization to fulfill its goals. In the healthcare industry, some of the goals are patient-care focused. A governance framework that in practice limits data availability or slows clinical process, for example, must be avoided.

As we move to the next sections of this chapter, we will distinguish between information security and information privacy governance. In many organizations, these governance structures are evolving into a more singular organizational structure, such as information protection governance. This is worth noting because there is overlap and interdependence in privacy and security functions. The primary information security function is focused on defending data and networks. In addition to this function, the effort includes protecting confidentiality (privacy) of sensitive employee and customer information. With the increasing digitization of information and IT capabilities of healthcare organizations, protection of patient privacy is impossible without sufficient information security processes and procedures. For now, we will continue to explore these governance frameworks separately, knowing they work best when they function together. In your organization, you may already see the integration of privacy and security governance into a single enterprise governance structure.

As part of the information governance function, various official groups or teams will be established within the organization. The group may be considered a committee, a council, or maybe a working group. Each comes with a degree of formality. A committee is typically the most formal of these and may require a charter, which is a document that is created at the inception of the committee and updated regularly upon review by committee members. The document outlines the committee’s mission, authority and responsibilities, and composition; how and when meetings will be held; as well as how meeting minutes will be written and approved. It also describes any reporting relationships to other organizational management or a board of directors. Having a charter helps to keep the formally established group aligned with its intended purpose. Other less formal groups may use a charter for similar reasons, such as for documenting purposes, but that is an optional step. If a charter is typical for groups identified in this section, it will be noted.

Security Governance

With the evolution from paper-based information to more and more digital data there is the need to have a well-understood structure for information security processes and functions. The security governance in a healthcare organization describes how strategic oversight of information protection happens. The performance of the governance functions is important. Healthcare organizations collect, use, transfer, store, and dispose of sensitive data that could be valuable to criminals and is vital to patient care. The conceptual framework for the information security governance consists of important individual roles and groups.

Information security governance is a strategic imperative and needs support from management at all levels of the organization. It requires commitment, resources, and assignment of responsibility for those in key positions. The governance function must also be able to demonstrate that it is effective through measurement and reporting to senior levels of the organization and the board of directors. The likelihood of information security governance being successful is related to the involvement of senior management in areas such as approving policy, providing appropriate oversight, and offering direction when measures and analysis warrant.

At a general level applicable to almost every organization, information security governance is needed for several significant reasons:

• Prepares the organization for potential risks

• Improves coordination and integration at all levels through setting responsibilities

• Protects substantial investments in information technology and data assets

• Supports cultural and organizational factors while enabling business needs

• Establishes and enforces organizational rules and priorities

• Assists in building trust with required supplier relationships and interconnections

• Results in a credible information security program

Healthcare information security is not a concern or a function that can be relegated to IT. Clinical and business leaders throughout the organization must come together to solve information protection issues. When that happens, good governance is a natural outcome of the leadership of the organization’s security consciousness and actions. There can be too much governance, however. In an effort to satisfy compliance measures and implement visible information governance teams, process can overtake progress. This happens when governance becomes unidirectional and the system users or information handlers themselves have no input in the process. The number of teams and bureaucracy can become too much to satisfy. The communication loop of sender, receiver, understanding, and feedback underlies the information governance structure in a well-run organization.

Board of Directors

Governing boards of healthcare organizations may not traditionally be included in discussions about information security governance. Organization management has held the roles and performed the responsibilities of information security governance; however, with rapid increase in the frequency and impact of data breaches and cybersecurity events, more boards are interested and involved in the sufficiency of the information security program. Directors need to understand and approach cybersecurity as an enterprise-wide risk management issue, not just an IT issue. The board should be involved in information security concerns such as organizational risk tolerance, cybersecurity insurance options, and how management is reducing risk for the organization. The high-level information security functions for the board should include the following activities:

• Ensure the organization has information security leadership in positions of authority.

• Review plans for the information security program and receive regular input from the information security leadership.

• Oversee and approve relevant information security policies and evaluate effectiveness.

• Designate a board committee for the responsibility to perform these functions (such as an audit committee).

A principal responsibility for the board of directors is to provide a requirement for organizational management to implement an information security program that is aligned to a risk management focus. The board must also expect management to properly resource the information security program with budget and personnel. The National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) is a source for board direction. Its handbook specifically mentions the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF) as a favorable option for boards to expect. This is because of the NIST CSF purpose and intent to enable “organizations—regardless of size, degree of cybersecurity risk, or cybersecurity sophistication—to apply the principles and best practices of risk management to improve the security and resilience of critical infrastructure.”1

Another purview of the directors should be the reporting structure of information security leadership to management and to the board. Many organizations align information security with IT. That may be the right answer for some organizations, but impacts of information security are organization-wide, not just in IT. Information security takes a risk reduction or management focus, while IT has different perspective. Some argue that IT is focused on innovation, advancement, or progress, which may seem like risk-inducing activities. In any case, the skillsets needed to manage risks and deal with issues that are organization-wide need to be independent from those required for organizational reporting structures. Boards are starting to require the senior-most information security professional—in most cases, the chief information security officer (CISO)—to provide a periodic, unfiltered view of the information security maturity of the organization and the information security governance process. Boards are being told by groups such as the NACD that burying information security in IT is a mistake. Without a clear line of communication with the CISO, the board must recognize the risk it faces by being uninformed.

It is not trivial to mention the legal and regulatory liability individual board members and senior management have in the aftermath of information security events. This reality should underscore the involvement of the board in information governance. Directors have increasing ethical as well as fiduciary accountability. Executive management and board members are being held accountable for many high-profile breaches, and in many cases, losing their positions while their companies lose revenue. In 2014, for example, a data breach at retail giant Target cost CEO, President, and Chairman Gregg Steinhafel his job.2 When Equifax was breached in 2017 and 143 million US consumers’ records were potentially compromised, the public backlash and prospect of regulatory intervention resulted in CEO Richard Smith stepping down. These high-profile events, accompanied by very likely civil and criminal liability, easily explain why board members insist on periodic review of comprehensive risk assessments and business impact analyses. Board members should be validating and ratifying the information security governance process for the organization they oversee.

Information Security Program

The first step in applying internal organizational policies against external regulations is to create a robust privacy and security management process. The information security program must be tailored and implemented based on organizational variables such as size, mission, key assets, and risk tolerance. Key elements of the program will be risk analysis and risk management procedures. These are important because standard information security best practices have demonstrated benefits in protecting sensitive information. Healthcare organizations are required to have proactive policies and procedures that implement appropriate information security controls. At the same time, cost and mission requirements must be factored into any information protection efforts. The information protection program will be a component of the information governance framework and will help identify key information security roles and responsibilities. The information security team will influence information security policy development and oversight. Its leadership will monitor ongoing activities and ensure success. Some of the other topics that the information protection program documentation will cover are the continuity of operations, personnel security procedures, and disposal of equipment, to name a few.

Using ISO/IEC 27001 as a guide, we can explore a general framework for an information security program or management system. Figure 2-1 depicts categories of the program along with descriptions of the purpose for the components—in other words, the who, what, how, and why pieces for the program.

Figure 2-1 Components of an information security management system

The information security program should focus on supporting business processes and initiatives. How the business manages risk, responds to incidents, or assigns responsibility for various information security requirements provides value to the business. The ISO/IEC 27001:2013 standard provides a way for organizations to establish, operate, review, and measure information security management systems (ISMSs).3 The ISMS includes the information security program and provides guidance for the overall governance. The standard is comprehensive and emphasizes areas such as senior management involvement in the information security program, recommends roles and responsibilities, and underscores the need for risk management to support business. It is important to understand the general intent of this standard is to do the following:

• Properly evaluate information risk by considering the interaction of threats, vulnerabilities, likelihood, and impact across the organization.

• Address risks by using a comprehensive approach of security controls tailored to the organization’s size, mission, and risk tolerance. Where specific security controls are not reasonable or appropriate, implement other risk mitigation tactics, such as cyber insurance.

• Perform ongoing review of the information security control process for operational effectiveness; continual improvement is a goal and risk levels change.

ISO/IEC 27001:2013 is a proven tool for information security professionals to use to significantly improve the establishment of a proper sense of ownership of both the risks and security controls in an organization. Specific to the information security program, any organization could use the accompanying standard ISO/IEC 27002, Code of Practice for Information Security Controls. This standard includes all the security control objectives and recommendations for specific security controls an organization can implement. For healthcare organizations, there are additional considerations: a necessary standard is ISO 27799:2016, Health informatics – Information security management in health using ISO/IEC 27002.

Information Security Steering Committee

Creating a culture of security requires positive influences at multiple levels within an organization. This includes an information security steering committee chartered to provide a forum to communicate, discuss, and debate on security requirements and business integration. The committee also encourages colleagues, coworkers, subordinates, and business partners to respect the importance of information security, which is given the same level of respect as other fundamental drivers and influencing elements of the business. It serves in an advisory capacity with regard to the implementation, support, and management of the information security program, its alignment with business objectives, and its compliance with all applicable state and federal laws and regulations. The steering committee also provides an open forum where business initiatives and security requirements can be discussed.

The membership of the committee must include a diverse representation of senior leadership from information security, information technology, business operations, clinical departments, and privacy. The CISO is most likely the most appropriate person to lead the committee. In larger organizations or where information security is more established, the group would benefit from additional members from other parts of the organization like ancillary services, human resources, or public relations. Regular committee meetings can ensure that there is ongoing adherence to the organization’s security policies. For example, if a new security policy is created, business unit representatives and/or department heads who are part of the steering committee can make sure their teams implement the policy.

Configuration Control Board

The configuration control board (CCB), aka configuration management board, should play an essential role in how an organization implements and manages its information technology asset. This board is listed as a security control in prevailing standards and policies, such as NIST, HIPAA, FISMA, ISO, and so on. The asset can include the local area network, any endpoint devices (including medical devices), and the various applications that are in operation. The chief information officer (CIO) or another senior information technology official is usually the chair of the group because the CCB focuses on technology. However, having voting members from just about every department in the healthcare organization is crucial.

The CCB is most effective in establishing the baseline configuration of the information asset, but this does not mean the organization must have a standard configuration. Most healthcare organizations have legacy systems (especially medical devices) that cannot meet current standards. Often, the budget does not allow rapid upgrades or modernization to the extent you might desire. Nevertheless, the CCB strives to know exactly what resides on the network. From there, controlling changes through a systematic process will help avoid vulnerability exploitations; whether that involves a patch or an addition of an entirely new system, the CCB is integral in making proper maintenance happen. To that end, the CCB has an eye on security, and members should take every opportunity to address security concerns during every phase of configuration management.

Information Management Council

Information governance is usually managed by an information management council (IMC) chartered to consider management and organizational issues as well as technical concerns. The requirement to have a group like an IMC is something leading auditors and industry evaluators want to see in healthcare organizations. The IMC will have a focus on information use and the impacts that concerns such as privacy and security have. In contrast to groups like the CCB, the IMC will not focus solely on technical issues. As a governance function, the IMC will be a central leadership committee that should have interaction with, and in best cases representation from, other groups such as data governance, the CCB, and enterprise risk management. IMC will concentrate on issues related to the access to information, how technology impacts information use, and the oversight of information policies and procedures. The IMC acts a conduit for senior IT and business leadership on matters of the organization’s information assets. It often informs senior leadership groups on use of resources to protect the organization’s information by reviewing particular initiatives related to the information security program.

The review of the information security initiatives by the IMC is an example of implementing a culture in an organization in which security is not just the job of IT. All current and planned initiatives, projects, and information capabilities lead by the security team are systematically addressed as enterprise projects. This means the organization realizes there is a shared responsibility for succeeding in the completion of the various projects. Some projects can be conducted within the structure of information technology leadership, but many cannot. Think of a commercially available application that a physician in the emergency room purchases and wants implemented in her department. Imagine, as it turns out, the application is not capable of interfacing with any legacy systems in the hospital. This may be an issue the CCB would address; or, depending on the cost, impact, and perceived value of the application working properly, the IMC could have prevented this scenario by managing it as part of the entire portfolio or list of approved projects. This scenario hints at how culture changes when security is recognized as an enterprise effort. The ability to quantify previously informal efforts based on having the IMC prioritize and value each initiative gives senior leadership an idea of investment and return on investment.

Risk Management Steering Committee

This chartered committee is included in this discussion because it may be the source of governance of third-party information sharing, which incurs a great deal of risk in the healthcare organization. The topic of vendor management may be included in other committee charters, as long as the risks are addressed and governed in alignment with risk tolerance and business strategy. The risk management steering committee is also included here to underscore the integration of governance, risk, and compliance entities with information security and privacy.

The charter and the composition of this committee is selected by senior management. Members represent areas of the organization with significant or impactful risk exposure. The committee reports outcomes to senior management. Some specific components of the committee charter should be the inclusion of specific risks, such as third-party risk, that are within the group’s purview. The committee’s deliverables include establishing the organization’s risk tolerance, which must be approved by senior management and the audit committee of the board of directors. The committee may also create and approve the organization’s risk management policy, key performance measures, and its own reporting requirements. A foundational responsibility of the risk management steering committee is to approve results of compliance reviews by internal audits or independent third parties. The committee provides tracking and oversight on remediation of reported deficiencies and provides governance for organizational issues that may unnecessarily increase information security risk.

Data Incident Response Team

Another security control required by various standards and policies such as HIPAA, NIST, ISO, and FISMA, the incident response team should be chartered prior to any data loss or breach occurring. Unfortunately, too many organizations fail to have an active or tested incident response team before an incident actually occurs. According to recent surveys, 77 percent of organizations do not even have a plan for responding to security incidents.4 Once there is a potential for a breach or an actual breach has happened, there is little time to pull together the right team members and conduct an investigation. Having a team ready to go when needed, with members who know their roles, enables an organization to respond in an accelerated, effective, and organized way when it is needed. Not all reports of data loss are matters that require reporting outside of the organization, such as reporting to government regulators or to patients themselves, but all suspected data losses must be investigated and the outcomes documented. An effective data incident team can prevent a serious loss of profits, public confidence, and/or information assets.

The CISO or senior physical security official likely heads the team. Other members of the team will come from information technology, legal, finance, senior medical representatives, risk management, internal auditing, human resources, and public relations. Of course, based on your organization, it may be important to augment this core group with subject-matter experts in data forensics, health information management, patient admissions, and so on. Ultimately, those who are selected as members of the team must understand their written roles and responsibilities, which should be tested via periodic mock data loss exercises. Prior to actual events, team members must be given the necessary authority to control resources that help them carry out their duties.

Privacy Governance

Personal information continues to be a monetizable asset, identity fraud a profitable crime, and confidentiality a difficult obligation. As a healthcare information security and privacy professional, you must be able to understand and apply governance to protect the privacy of individually identifiable information. Numerous regulatory and organizational implications provide mandates and requirements in this area. Similar to information security requirements, privacy governance can vary depending on jurisdiction per geography or industry.

The governance functions of information privacy within an organization are related and complementary to the information security governance. It is important to note that the relationship is reflective of the evolution of information security and privacy into important disciplines and concerns with increasing overlap. Traditionally, information privacy and security have been siloed. Mature information governance programs are integrating the multiple governance structures, if you include related disciplines such as enterprise risk management, compliance, legal, and audit. Our scope includes only information privacy and security.

Following is the preferred outcome of the integrated governance approach:

• Improved e-discovery, compliance, audit, recordkeeping, and regulatory obligations

• Better data breach prevention, detection, and response

• Enhanced protection of the privacy of employees, customers, and other stakeholders

• Increased linkage with information use and governance, and strategic alignment with business initiatives

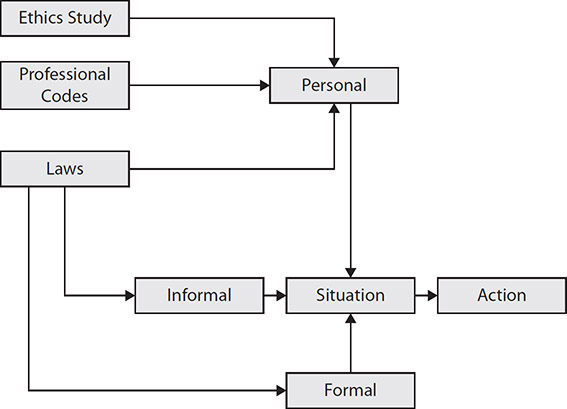

Governance promotes and ensures responsible behavior to protect the privacy of all associated individuals. The three lines of defense model, shown in Figure 2-2, can be should be used for information privacy governance and should be tailored to enhance the understanding of information privacy as part of risk management. This framework is from an auditing standard, the Internal Control – Integrated Framework from the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO).5 (In the COSO model for enterprise risk management, a key distinction is the second line of defense, which includes compliance, risk, legal, security, and privacy. This is simplified to use for a privacy governance model. As COSO mentions, “depending on the organization’s size and industry, the composition of the second line can vary significantly.”) Although many organizations use this model for enterprise risk management, it is applicable to our scope as well. The framework is used to outline and clarify roles and responsibilities. When used for information privacy governance, the model guides oversight of the functions from the board of directors and reduces gaps in roles and responsibilities through layers of oversight, which is required for effective information privacy governance. Figure 2-2 depicts a general structure for the three lines of defense model.

Figure 2-2 Three lines of defense model

The following provides a brief overview of the three lines of defense structures (they are not prescriptive because organizations may customize them based on unique requirements):

• First line This includes the information or data owners who create and use the assets. They are responsive to the data users to make sure data is accurate and complete. They have primary responsibility to ensure the organization meets regulatory requirements.

• Second line This includes a centralized information privacy office with chartered committees and groups to create policies and procedures relating to organizational data. These groups also provide oversight and management. Policies or procedures that are not operating effectively are escalated to this line of defense within the governance structure. This function provides strategic perspective for the use of data and investment in information assets.

• Third line This is a final backup mechanism within the organization that has accountability directly to the board of directors (typically through the audit committee) and sometimes directly to government oversight entities. This is usually the internal audit group. Its principal role is the review and assessment of data management and organizational policy effectiveness.

Generally Accepted Privacy Principles

Generally accepted privacy principles (GAPP) are rooted in the principles established by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and by ISO guidance. They attempt to regulate the collection and use of personally identifiable information (PII) in adherence with fair information practices and prevailing laws. One of the biggest proponents of GAPP are Canadian privacy practitioners, which is likely related to the fact that the principles were developed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA).

GAPP is founded on the following privacy objective: “Personal information must be collected, used, retained, and disclosed in compliance with the commitments in the entity’s privacy notice and with criteria set out in GAPP issued by the AICPA/CICA.”6

From that AICPA/CICA guidance, the following are the ten GAPP privacy principles:

• Management The entity defines, documents, communicates, and assigns accountability for its privacy policies and procedures.

• Notice The entity provides notice about its privacy policies and procedures and identifies the purposes for which personal information is collected, used, retained, and disclosed.

• Choice and consent The entity describes the choices available to the individual and obtains implicit or explicit consent with respect to the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information.

• Collection The entity collects personal information only for the purposes identified in the notice.

• Use, retention, and disposal The entity limits the use of personal information to the purposes identified in the notice and for which the individual has provided implicit or explicit consent. The entity retains personal information for only as long as necessary to fulfill the stated purposes, or as required by law or regulations, and thereafter appropriately disposes of such information.

• Access The entity provides individuals with access to their personal information for review and update.

• Disclosure to third parties The entity discloses personal information to third parties only for the purposes identified in the notice and with the implicit or explicit consent of the individual.

• Security for privacy The entity protects personal information against unauthorized access (both physical and logical).

• Quality The entity maintains accurate, complete, and relevant personal information for the purposes identified in the notice.

• Monitoring and enforcement The entity monitors compliance with its privacy policies and procedures and has procedures to address privacy-related complaints and disputes.

Data Governance Committee

Within the organization, the chief data officer (discussed later in the chapter) leads a separate, centralized department that focuses on data governance. Although data governance does concern itself with information privacy and security, there are other important domains in data governance activities: Data governance administers policies and procedures for data usability, consistency, and quality. The function oversees data management practices, strategy, and structure so that the organization can transform data into meaningful information. In today’s healthcare organization, the importance of data governance as a component of the information protection capabilities is increasing. To perform data use and analytics functions, the healthcare organization must implement data governance. In fact, healthcare organizations find it difficult to adhere to regulatory guidance and compliance directives across the globe, such as HIPAA and GDPR, without data governance.

A data governance committee will help guide efforts and oversee issues. Membership includes key people often appointed by the CEO or the board of directors. Its charter is to ensure that data is treated like an asset, and that through proper use, it becomes meaningful information. The committee in a healthcare organization should comprise a multidisciplinary group of decision-makers, including a chief data officer, chief analytics officer, chief financial officer, chief medical officer, chief information officer, and chief operating officer. Along with these senior leaders, representation from specific clinical departments, such as radiology or the emergency department, can be valuable. Participants may also come from business and operational areas, at the discretion of the organization. Healthcare organizations can realize a significant benefit from a data governance committee that consists of clinical, operational, and financial leadership, which intends to transform the data asset into a single definition of truth or, again, meaningful information.

The charter of the data governance committee would include some specific technical considerations. The committee establishes and ensures maintenance of metadata definitions that help with data usability. The group also ensures that business rules for access and use are followed. The integration with information privacy and security include ensuring that appropriate levels of data privacy and security audits are conducted.

The responsibilities and charter of the data governance committee extend beyond the data asset itself and include how the data is used. The committee defines and establishes certain roles such as the data steward in the organization. There should be transparency in data flow where data is shared between organizations. The committee has oversight for review and approval of strict data access monitoring as well as reporting policies and procedures. Additional, unique responsibilities include implementing specifications of data extraction, data transformation, and data loads. Of course, the integration of adequate data security and privacy measures is a shared area of responsibility with the types of committees previously mentioned in this section.

Audit Committee (Board of Directors)

As mentioned, the board of directors has a governance role in information protection. It is certainly true that the board’s role is not constrained to information security; it also includes information privacy, risk, audit, and compliance. However, depending on the industry, a component committee of the board often has a more specific role in reviewing control effectiveness in information protection. The audit committee of the board is mentioned here because this group has traditionally had purview over information privacy. As data breaches and cybersecurity events have elevated information security to the level of full board concern, the audit committee remains relevant to information privacy governance.

An audit committee is usually appointed by the board and is a minimum of three independent directors with no connection to organization management. The primary charter for the committee is responsibility for internal controls and financial reporting oversight. An example of information shared with the audit committee is a report on data breaches and notifications in a specified period of time. This helps to satisfy the committee’s responsibility for overseeing the organization’s system of internal controls and compliance with laws and regulations.

Institutional Review Board

If you work in a dedicated healthcare research organization or in an organization that conducts research as part of its academic mission, you will interact with an institutional review board (IRB), also called independent ethics committees or ethical review boards. These are formal, chartered committees that approve, monitor, and review biomedical and behavioral research involving humans. Their primary purpose is to protect human subjects from physical or psychological harm. Much like the first rule of privacy is to determine not to collect information unless you need it, the first rule of research is to determine whether the research should be done. The IRB determines this for the organization through a risk–benefit analysis.

The following are the guiding principles of any IRB according to the Belmont Report:7

• Respect for people People should be treated as autonomous agents (individuals), and those with diminished autonomy must be protected.

• Beneficence The well-being of study participants should be protected by adhering to “do no harm” and maximizing benefits while minimizing potential damages.

• Justice Participants should have equal opportunity to be selected, because even if there is a benefit, there is probably a burden some people will have to bear.

Information Governance Roles and Responsibilities

The information governance structure in each organization will vary. That is acceptable; drawing from the NIST definition of information governance, you can understand why multiple structures and frameworks can apply to an organization. The purpose of information security governance is to ensure that agencies are proactively implementing appropriate information security controls to support their mission in a cost-effective manner, while managing evolving information security risks. As such, information security governance has its own set of requirements, challenges, activities, and types of possible structures.8

Two components of information governance are the definition of key roles and the identification of relevant responsibilities. Common to all information governance structures are activities that support decision-making, defined processes, and personal accountability within the governance framework. This section discusses some common information governance roles and responsibilities you should see in your organization, especially in a healthcare organization.

Chief Information Security Officer

It is popular to say that “information security is everyone’s job,” but in many organizations, leadership and responsibility ultimately reside within the job description of one individual—the chief information security officer (CISO). In larger organizations, the role is likely represented in the senior executive management team. As healthcare organizations evolve to more digital capabilities with numerous interconnections with external partners, the need for a CISO is an imperative. In smaller organizations, the function may be delegated or assigned to an individual who is a non-executive, such as an information security officer (ISO). As the role increases in importance and impact, even smaller organizations should be recognizing the need for specialized, senior-level competence at this leadership level; otherwise, the source of conflict in many companies between IT and information security will continue, and that scenario increases overall information security risk. It makes sense to reiterate that the appropriate segregation of duties for the ISO or CISO is becoming a security standard.9 In some organizations, the CISO or ISO reports directly to a senior functional executive other than the chief information officer (CIO), such as the CEO, the COO, the CFO, or general counsel. In any case, the senior subject matter expert (ISO or CISO) should be directly accountable to the governing board. Of course, this supposes that the individual has sufficient knowledge, background, and training to be effective and successful.

The role of the CISO is to coordinate and manage security efforts across the company. A CISO also realizes the role includes transforming organizational culture to integrate and engineer information security into business, IT, and clinical processes. The most successful CISOs successfully balance security, productivity, and innovation and act as leaders, teachers, evangelists, and domain experts. The CISO must be an advocate for security as a business executive while being mindful of the need to protect the organization from potential risks; the role comes with opportunities to enable business strategies, but at times, risk management dictates caution. The CISO may not be the most popular executive, and this is why good security decision-making within organizations is not forced on one individual alone: the CISO or ISO must be supported by the governance process consisting of a multidisciplinary committee that represents functional and business units.

Several regulatory requirements relate to the need for a CISO. Although the leading standards stop short of specifying and mandating a CISO, the position satisfies the requirement and is a best practice in these times when information security is paramount for healthcare organizations. Here are some examples of directives drawn from various regulations and standards calling for senior-level information security expertise in an organization:

• Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) “In order to develop, implement, and maintain your information security program, you shall (a) Designate an employee or employees to coordinate your information security program.”

• HIPAA/HITECH Security Rule section “Identify the security official who is responsible for the development and implementation of the policies and procedures required by this subpart [the Security Rule] for the entity.”

• Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DDS) “Assign to an individual or team the following information security management responsibilities: establish, document, and distribute security policies and procedures; monitor and analyze security alerts and information, and distribute to appropriate personnel; establish, document, and distribute security incident response and escalation procedures to ensure timely and effective handling of all situations; administer user accounts, including additions, deletions, and modifications; monitor and control all access to data.”

Chief Privacy Officer

The CPO is assigned responsibility for handling and disclosure policies and procedures for personal information, including PII and PHI. CPOs make sure personal information is collected, used, retained, disclosed, and disposed of in conformity with the commitments in the organization’s privacy notice and with criteria set forth in best practice, such as GAPP, and in compliance with state, federal, and international law and customs. CPOs also manage organizational processes for identifying data breaches and potential data breaches. They are the central point of contact in providing breach notification and other data incidents to the board of directors, executives, regulators, and government officials. The responsibility extends to reporting breaches that happen at third-party vendors and suppliers as well.

As you can imagine, the impact and weight of these communications have significant impact on an organization. This is one reason why many CPOs are licensed, practicing attorneys with many years of experience, especially in healthcare law. However, a CPO can be successful without being an attorney. In the European Union, a data protection officer (DPO) is analogous to a CPO and is mandated in the GDPR. The GDPR does not specify the DPO’s qualifications, but the DPO must have professional expertise in national and European data protection laws and practices and an in-depth understanding of the GDPR.10

Privacy law is relatively extensive internationally. To provide evidence of this, consider the following list of leading international privacy laws that some healthcare privacy officers need to discern:

• Canada Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) governs how you can collect, store, and use information about users. It applies to online information shared in the course of commercial activity. PIPEDA mandates that data collectors disclose privacy policies and make them publicly available to customers.

• European Union The GDPR became enforceable in 2018 and is to date the most robust privacy protection law in the world.11 The GDPR replaced the Data Protection Directive and has become a model for other nations’ legislation concerning individual privacy. Key features of GDPR are the two types of fines it introduces for noncompliance. The first fine is up to €10 million, or 2 percent of the company’s global annual revenue of the previous financial year, whichever is higher. The second is up to €20 million, or 4 percent of the company’s global annual turnover of the previous financial year, whichever is higher.

• Hong Kong The Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (PDPO) applies to public and private entities. It states that users must be informed of the purpose of any personal data collection and with whom the data may be transferred, including third-party vendors and suppliers. PDPO requires that all personal data policies and practices be made publicly available. Those who breach the PDPO can incur financial penalties, which include fines up to HK$50,000 and up to two years in prison. Civil suits by impacted individuals are also permissible against companies that violate the ordinance.

• India Privacy protections are included in the Information Technology Act, which requires every business to have a privacy policy published on its web site. Whether or not the organization collects sensitive data, it is required to have a privacy policy that lists data collected, the purpose of the data, any third parties data might be disclosed to, and what security practices are used to protect the data. Users have to consent explicitly to some types of data use. For example, if the organization is collecting passwords or financial information, consent must be given to the organization.

• South Korea An example of South Korea’s national legislation to protect the privacy of citizens is in the telecommunications industry. Communication service providers have to obtain consent before collecting sensitive information to adhere with the Act on Promotion of Information and Communications Network Utilization and Data Protection. The privacy notification must provide the user with information about their rights concerning their own data.

• United States The legislative environment for information privacy in the United States is extensive, but it is regulated mostly at a state or industry level. There are federal laws, but not as many as exist in some other nations. It is valid to conclude that US information privacy laws are a confusing mess of rules and regulations that you must navigate. Following are some pertinent federal and state legislative sources of information privacy protections:

• The FTC (Federal Trade Commission) regulates business privacy laws. It doesn’t require privacy policies per se, but it does prohibit deceptive practices.

• HIPAA deals with health-related information.

• The New York State Personal Privacy Protection Law (PPPL) protects individuals from the random collection of personal information by state agencies. The law enables a person to access and correct information on file about themselves. It also regulates disclosure of personal information to persons authorized by law to have access for official use.

• The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) is modeled to a certain extent on the European Union’s GDPR. The regulation enhances privacy rights and consumer protection for residents.

• United Kingdom To uphold the information rights in the public interest, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office authored the Data Protection Directive. This legislation requires fair processing of personal data. Those who collect personal data must be transparent with regard to the collection purpose and use.

Chief Data Officer

The chief data officer is a senior executive who can support information security and privacy programs through responsibility for the use and governance of data across the organization. A succinct way to think of this important role is as the “voice of the data” for the organization in an era when data is an organization’s most valuable asset. The chief data officer oversees a range of data-related functions that may include data management, ensuring data quality, and creating data strategy. Additional roles include oversight of data analytics and business intelligence.

Information System Owner

In the organization, information systems can be centrally managed in IT or decentralized and managed by business and clinical personnel. Some common titles for the information systems owner position are system administrator, product owner, or program manager, depending on how an organization identifies roles and responsibilities. The information systems owner is responsible for applying the principles, policies, and procedures for the overall procurement, development, integration, modification, or operation and maintenance of an information system.12 This professional is responsible for the security controls needed to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, availability, and privacy of data in all forms throughout the systems development life cycle (SDLC) and data lifecycle for data the system uses.

Data Owner

The data owner helps design policies and procedures regarding how information is used and where it resides. This person oversees information throughout the data’s lifecycle and is involved in data-quality management, data security, auditable compliance with privacy and disclosure guidelines, information life cycle management (ILM), and business-continuity planning and disaster recovery. They classify and categorize the information, as PHI or sensitive, for example, because of their knowledge of the assets. This role plays a significant part in safeguarding information assets.

Data Steward

A data steward has a level of responsibility for the quality of data that surpasses that of the data owner. Stewards are not direct owners of the data, but they are selected as caretakers. Data stewards draft the data quality rules for data, while a data owner approves those rules. Data stewards come from the business side and understand the business, and they are responsible for the data within their area of expertise, which they fully understand. In many cases, a data steward helps with training data owners and users concerning data management and analytics issues.

Data Controller

In the GDPR, data controllers are people or organizations that collect personal data from EU residents. It can refer to an entity located in the European Union or any other country that collects EU residents’ data. For example, if a US-based web site is accessed by an EU resident, and the web site collects or tracks personal information through saved cookie files, tokens, or by direct input from the end user, GDPR requirements would likely apply. The data controller role determines the purpose for the information and how it will be used throughout its lifecycle.

Data Processor

A data processor is related to the data controller, but the two are not the same. In the GDPR, the data processor role may be an organization external to that of the data controller and is used to carry out authorized required actions. The data processor cannot change the purpose for which the data was collected. This role is charged with accomplishing data processing activities according to the directions provided by the data controller. Entities such as medical billing companies and cloud service providers may fall into the category of data processors if they are third-party suppliers or vendors for the data collector.

Data Custodian

A data custodian can be a person or team that owns documents or electronic files. It describes the individuals or entities with responsibility for protecting information through access control and through maintaining administrative, physical, and technical controls for information protection. A key difference between a data custodian and a data steward is that a data custodian is responsible for protection from a technical perspective. A data steward focuses on the business rules or authorized use of the data. A data custodian deals with issues such as security, accuracy, backups, ability to restore, and maintenance of technical standards. The data custodian would provision or deprovision access to data at the direction of the data steward.

End User

An end user of an information system with regard to the governance structure is admittedly a liberal interpretation of guidance on the topic. An end user is any employee or actor, who, on behalf of the organization, creates, transmits, stores, or deletes an organization’s information. Add to that definition the policies and procedures we expect end users to know and follow because of end user information protection training. Together, these elements constitute a responsibility for end users that really does integrate into overall information governance. Each end user plays a critical role in protection of information.

Information Security and Privacy Policies and Procedures

Documentation and doctrine for the information governance processes and programs must be in place in any organization that collects data and provides benefits ranging from regulatory compliance to end-user training. The leading information governance programs have documented policies, standards, and procedures that are available for organizations to reference internally as well as to external reviewers, such as auditors, when required. Creating organizational policies that align with well-known standards and procedures provides the following benefits:

• Consistency in structures and procedure to maintain expectations and quality

• Guidance for employee behavior and performance in uncertain processes and scenarios

• Guidance in decision-making in routine situations and clarity during chaotic times

• Fairness and equality demonstrated through adherence to internal regulations

• Just administration of employee misconduct or malicious acts

• A framework for delegation and communication for roles and responsibilities

• The ability to demonstrate a measure of due care and diligence for information protection

It is also important that you align policy and procedures based on relevant national and international laws. On a daily basis, most of us do not refer to national or international laws to do our jobs. It is far more likely that you take actions related to information sharing and protection as a result of what your organization’s internal guidance tells you to do, versus citing HIPAA or GDPR. You must be able to determine what internal policies and procedures your organization needs, which must also be consistent with the laws that govern your industry. Lastly, you must be able to apply the internal guidance documents to your daily work while being able to clearly articulate why the proper actions are being conducted.

Although you won’t refer directly to national and international law on a daily basis, you can defend the need for organizational policy and procedure on regulations. An overarching control found in almost every regulation is a legal obligation for each healthcare organization to have its own internal guidelines to prevent, detect, contain, and correct information protection violations. Data protection laws mandate that healthcare organizations ensure the confidentiality of its patients. National and international regulations must be customized to reflect your organization’s policies and enforcement abilities. You must be able to apply regulation to operations of your organization and assign responsibilities according to various positions in the organization.13 For instance, the owner of each policy must be identified. That entity, then, will have the responsibility of monitoring the effectiveness of the guidance and making periodic updates as needed. Senior-level officials such as the CIO or CPO may have assigned responsibilities as well. These individuals may enact procedures to commit resources or administer corrective actions when things do not go according to plan.

Policies

Policies offer guiding principles to help in decision-making. These clear, simple, and broad statements regarding how your organization conducts business and healthcare operations can consist of a few paragraphs that cover the various expectations for certain actions. For the most part, organizations use the terms “directives,” “regulations,” and “plans” interchangeably with “policies.” No matter its name, a policy in any form should have the following identifiable elements:

• Supplemented Policies tend to be broad statements, so proper implementation usually requires procedures, forms, and other types of direction that can be used by staff to clarify them. Also, rather than reissuing policies, it is often more feasible to supplement a policy with recent improvements or additional parameters using a versioning process. Here’s an example: The policy is created and issued as version 1. After reviewing the policy according to how often policies are reviewed for currency (such as every two years), management decides to add responsibilities for a CISO. Rather than completely republish the policy, the relevant information concerning the CISO position can be added as a supplement, or version 2. This also introduces a related element common to all policies: they must be dated.

• Visible All policies must be made available, via a web portal or intranet, for example At the least, members of the organization who are responsible in any way for complying with the policies will need to be able to access them. Training related to a policy is also important in making it visible and communicated.

• Supported by management This almost goes without saying, but a policy must be supported by management or it will not be followed. More to the point, management must also support the policy by overt action; they cannot circumvent the policy or ignore it and expect hospital staff to comply.

• Consistent Unless there is some unique aspect to the healthcare organization, such as its geographic location or community, the likelihood is that any policy will have an origin in a public law or government directive. A policy should not conflict or guide employees to violate these laws. That said, when developing a policy, you should consider references beyond legal ones, such as organizational culture and organizational mission, when writing the expectations.

Your concern is primarily information protection policies. These types of policies will have varying levels of focus within the organization. At one level, a policy is used by management to create privacy and security programs, establish goals, and assign responsibilities. Policies can also be system-specific rules of operation, or they can simply guide managerial decisions concerning one particular issue such as e-mail privacy policy or release of information policy. According to NIST SP 800-15, Generally Accepted Principles and Practices for Securing Information Technology Systems, which draws upon the OECD’s guidelines for the security of information systems, your organization should have examples of policies at all levels—some governing programs, some system-specific, and some issue-specific.

Procedures

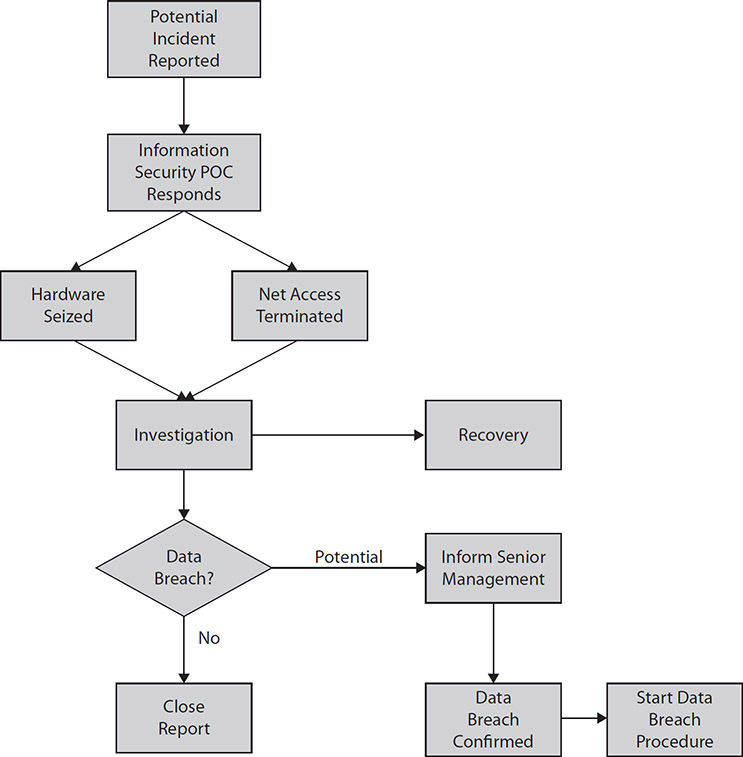

Sometimes called standard operating procedures (SOPs), an organization’s procedures describe how each policy will be implemented. These are written instructions, illustrated flowcharts, and/or checklists that cover a routine or repetitive activity. Figure 2-3 illustrates an example of a procedure flowchart for actions that should happen once a data incident or potential data breach is reported. SOPs should not replace policies but should supplement them, or at least the SOP steps should reference the governing policies. You may encounter terms such as “protocols,” “algorithms,” “instructions,” and “tasks” used in place of “SOP.” As long as the content is routine and repetitive and covers how the activity is carried out, these terms are synonymous.

Figure 2-3 Example of flowchart of initial data incident investigation procedure

The benefit of having SOPs to clarify policies at the varying levels is to reduce uncertainty and variation in performance. To be most effective, an SOP must accomplish the actions required by the policies, at a minimum. Like policies, SOPs must be visible (maybe even more so), supported by management, and consistent. If they are not or if they seem to contradict the policies, caregivers and business staff will likely create alternative workflows that may or may not be effective and efficient.

Notable Policies and Procedures

There are almost infinite numbers of policies and procedures that could exist in your organization. Rather than attempt to compile a list, which would ultimately be insufficient, we cover a few important policies and procedures that you will most likely encounter. Keep in mind that this is a small sample, and throughout the text we will address numerous other policies and procedures that are indispensable.

Information Protection Program

The first step in applying internal organizational policies against external regulations is having a robust privacy and security management process. Key elements of the program will be risk analysis and risk management procedures. These are important because standard information security best practices have demonstrated benefits in protecting sensitive information. Healthcare organizations are required to have proactive policies and procedures that implement appropriate information security controls. At the same time, cost and mission requirements have to be factored into any information protection efforts. One of the most important structures established by the information protection program will be an information governance framework that identifies key information security roles and responsibilities. This team will influence information security policy development and oversight. Its leadership will monitor ongoing activities and ensure success. Some of the other topics that the information protection program documentation will cover are the continuity of operations, personnel security procedures, and disposal of equipment, to name a few.

Release of Information

The need for a policy regarding the release of information is rooted in law. In the United States, HIPAA requires healthcare organizations to have a written policy in place. You will find the requirement internationally as well; for example, the United Kingdom and Australian legislative institutions have ordained laws and policies concerning the disclosure and release of health information.14 Hospitals in these countries must develop policies and procedures based on relevant laws. The policies need to be consistent with applicable privacy rights for patients. Of course, since the release of information is a common, recurring daily task, a written policy also controls the process so that information is not handled incorrectly.

Although each organization’s release of information policy will differ because local workflow is unique to each, every release of information policy should follow these basic principles:

• Use and disclosure This includes how the information is normally shared, with whom, and when specific patient consent would be needed. Otherwise, information will be released without requiring a patient signature or additional authorization. You also need to include any situations where information cannot be shared.

• Minimum necessary rules Healthcare organizations must make efforts to disclose only what is needed. If, for example, only one specific encounter is under review, the entire legal medical record probably is not needed for disclosure.

• Patient rights The healthcare organization must inform patients about what rights they have concerning their information and how it is released to other entities.

• Organizational controls and safeguards The release of information policy will include contingency and risk management information concerning how protected health information will be secured during business and clinical workflow interruptions.

• Right to revoke or opt out In many countries, the release of information policy must allow the patient to change their disclosure preferences and provide information as to how to indicate their changing preference.

The challenge for you may be in helping your organization keep their release of information policy current against ever-changing standards and regulatory guidance. This can be mitigated by ensuring that this specific policy is created and reviewed by several people in the organization who have privacy and security responsibilities and backgrounds. This is not a policy to be created by one person.

Notice of Privacy Practices

Several laws and regulatory recommendations internationally, including HIPAA in the United States, the Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) in Canada, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Europe, have provisions for notifying individuals of the organization’s privacy practices. The notifications should clearly identify collection and use practices and must also cover the privacy rights individuals have with respect to their personal health information.

The notice of privacy practices is similar to the release of information policy, because both include many of the same components. Where they differ is in how they are implemented. To start, there is typically a requirement for the notice of privacy practices to mention specifically that the healthcare organization is obligated by law (if applicable) to protect the information. Under HIPAA and PHIPA, this is the case. Other differences are in data dissemination. Most often, a new patient receives a copy of the notice at the first service encounter or appointment. If the treatment is under emergency conditions, the notice is given to the individual as soon as possible after the emergency is over. The organization must have a notice of privacy practices identified and displayed in their organization for patients to view.

Beyond that, the healthcare organization provides this notice at several times. For instance, in the United States, it is provided at the time of enrollment in a health plan. Every three years, or sooner, the notice is sent as a reminder or upon request. Finally, the notice is to be prominently displayed on the organization’s web site for patients to access. As you can see, the notice of privacy practices is not as incident-specific as the release of information policy.

User Agreements

“User agreement” is a general term that you will see in the form of confidentiality agreements, end user license agreements (EULAs), or personal accountability documents. Typically, to instill a level of semiformal accountability in policies and procedures, staff members (users) are required to acknowledge understanding and willingness to comply with training, policy, or other regulatory requirements in a user agreement.

One of the best uses of a user agreement is to authorize a specific user to access an application or clinical system, such as the EHR. In such an agreement, you will find the following general terms and conditions:

• Access to protected health information is intended only for authorized users and for legitimate purposes. All other access is prohibited.

• Users consent to monitoring and auditing of their use of the application or the system.

• Users will protect and not share their access credentials (user ID and password, for example), which would allow someone else to access the system under their login or authentication. Some user agreements specifically mention that users maintain responsibility for any access that occurs using their access credentials.

• If there are specific actions that are worth mentioning concerning user behavior, they can be outlined in the user agreement. Here are examples:

• Downloading protected health information to external devices may be prohibited.

• Transporting external media from the healthcare organization may not be allowed.

• Fully powering off computer systems when not in use to ensure full disk encryption is required.

• Following data incident reporting procedures according to relative policy is required.

• Users will complete any training that is required prior to accessing the system, and they will provide proof of completion (certificate) to appropriate personnel.

User agreements can certainly include more elements than these. They should be customized based on local requirements, and they can be updated. For instance, leadership may want to allow protected health information to be downloaded by some users on external USB drives (thumb drives). The user agreement can be revised to make this allowance (and perhaps prohibit it for some users).

Incident Reporting Policy

Despite robust prevention and monitoring procedures, data loss can happen. As a point of reference, almost 800 data breaches involving 500 or more individual records have occurred since 2009. This has resulted in a total of almost 30 million records, according to reports received by US Health and Human Services (HHS).15 It is estimated that all other types of breaches of a single record up to 499 records have accounted for about 80,000 events in the same period of time.

An organization that is prepared for potential and actual data loss incidents improves its overall privacy and security program, even if it cannot eliminate the risk. Knowing how to handle escalation of events and coordination among the right people is the framework of an incident reporting policy. Incidents are managed according to identified roles and responsibilities. An incident reporting process is required to avoid disruptions in patient care or business processes. In addition, every effort must be made to preserve the evidence of an incidence to allow for proper forensics and analysis. The positive outcome of the policy would be to enable healthcare organizations to improve their information protection based on lessons learned from these events.

The incident reporting policy guides the organization through some general phases. First, the incident is suspected or detected. Here’s an example of an incident: An intensive-care nurse notices that his computer has been accessed because he stepped away and left it accessible. When he returns, the screen is on a web site he had never visited. Unfortunately, he was also logged into and using the EHR before he stepped away. Now there is a chance someone else has viewed the record and possibly accessed any number of other records in the database.

Following the detection phase, the nurse escalates the event via the alert phase. This is where the right people are identified for internal notification. This will include the hospital’s identified privacy officer and probably the senior information security official. After they are alerted, others who have responsibilities in hospital privacy policy may be included. This action will move the process into triage and response phases.

In leading healthcare organizations, the incident reporting policy enacts a team responsible for conducting actions, including triage and response. The team may include the privacy officer and the senior information security official as well as senior members of the information technology department. Other additions to the team could be the physical security officer, empowered business area leaders, and possibly someone to represent clinical interests. During the triage and response phase, the committee should include interested individuals who have sufficient organization authority to facilitate the completion of the investigation. Keep in mind that as the investigation proceeds, it gets costly, resources may be needed, and senior leadership, including the governing board, may need to be notified.

Once the team confirms the event and takes actions to respond, the goal is to contain the incident and eradicate the cause. From there, the team begins the recovery process and schedules follow-up tasks. These tasks would lead to external notification actions taken by third-party partners that specialize in data loss or breach notification. It may also include making a claim against any existing cybersecurity indemnity insurance the organization may have. In any case, the follow-up actions integrate into additional policies the organization has that are likely outside of the incident reporting policy.

Sanction Policy

In the United States, HIPAA specifically requires healthcare organizations to have and demonstrate how to follow a sanction policy to discipline employees who violate procedures for handling PHI. A sanction policy can be an extension of an organization’s incident reporting policy. Once an incident is reported and investigated, data loss is resolved, and any external notification is done, the organization must take the next step and apply the appropriate and consistent discipline.

A good sanction policy will contain two basic components: the type of offense and the type of sanction or punishment. Management would have the flexibility to examine the nature of the offense, any previous offense, or the intent behind the offense. Then management could look at a variety of predetermined discipline actions that fall within a minimum and maximum, depending on the offense. The action could range from a verbal reprimand, to a written admonishment, to suspension and ultimately termination.

In the end, the key points are that this type of policy provides management with a tool to make objective decisions absent of the appearance of impropriety or favoritism. The sanctions provided are not arrived at on a whim or based on emotion. They are included within a written policy, which strengthens the organization against any dispute from an employee who is disciplined. Most importantly, the organization can demonstrate that for particular offenses, equivalent sanctions are applied to all. Of course, organizations do not want to have a lot of sanctions to demonstrate compliance; it’s better to have few incidents. Any sanction policy should be communicated to employees during the new-hire orientation process and then annually during retraining. An added measure to gain acknowledgment is to have employees sign a policy document to indicate their understanding of the policy and their obligations to comply.

Configuration Management Plan

In a complex healthcare information technology environment, there must be an organized, coordinated policy and a process to plan, implement, maintain, and decommission information technology assets, including hardware and software. You will find a complex information technology environment in healthcare, where the state-of-the-art medical devices interface with homegrown systems and applications. Often, because of the proprietary manufacturing of certain medical systems, a platform may lag behind the latest supported platform that is preferred. When there is a patient safety risk of replacing the outdated platforms or updating them or when it costs too much to do so, healthcare information technology leaders may be forced to maintain and interconnect the platforms with mitigating controls for privacy and security.

Configuration management is important for information assurance to provide confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data used in healthcare. It is used to manage the security features of hardware and software by controlling changes through the lifecycle of the assets. Not only do the changes need to be managed, but documentation must be updated accordingly. The plan must include provisions for testing proposed changes to the baseline configuration prior to implementation. In fact, many plans include scenarios or regression test cases, which will help ensure that proposed changes, even vulnerability patching, are accomplished safely and efficiently.

You will encounter several common activities in the configuration management process:

• Planning The organization will require the objectives and strategies to be documented and available for personnel to use.

• Classifying and recording A good configuration management plan (and a good information security program) always starts with a proper inventory to determine the baseline configuration. As the baseline changes, the inventory process continues to document the new normal configuration.

• Monitoring and control The change request process must mandate that changes are controlled by a disciplined process of request, testing, approval, and then implementation. Further, those responsible for maintaining the baseline must monitor the process to ensure unauthorized changes are not made.

• Release management Within the control function, release management is the orderly process by which new or modified changes that have been fully tested and approved are installed into the business or clinical system. Releases are classified and recorded based on whether they are major, minor, or emergency releases.

• Auditing To verify that configuration remains at a state that matches the current documentation, you must perform random and routine audits.