CHAPTER 7

Third-Party Risk Management

This chapter covers Domain 7, “Third-Party Risk Management,” of the HCISPP certification. After you read and study this chapter, you should be able to:

• Inventory third parties that handle sensitive information for the organization

• Design and conduct third-party risk assessments when required

• Respond to information privacy and security events caused by external suppliers

• Integrate privacy and security requirements in establishing third-party arrangements

• Understand the role in third-party risk mitigation activities

• Establish and enforce secure external information disclosures such as breach notifications

The healthcare organization cannot possibly provide all products and services required to deliver patient care and sustain business operations. Numerous third parties are essential to augmenting and supporting a healthcare organization’s activities. For example, medical coding and billing are commonly accomplished by an external organization under contract to the healthcare organization. In the United States, third parties, or business associates, can be contracted to handle protected health information (PHI) on behalf of the healthcare organization. With the data flow for sensitive health information extending beyond the healthcare organization to third parties, new vulnerabilities are present. Add to this the growing mandate from regulators and payers alike to share more data, even among competitors. For a healthcare organization to have a firm information protection program in place, it must know its third parties and conduct periodic reviews to determine how well third parties handle PHI. This chapter illustrates why information risk management for third parties is important in the context of scenarios common to healthcare operations.

Managing risk when using third parties is subject to legal restrictions in countries with privacy and security regulations, but it also follows the leading privacy and security frameworks. According to the Generally Accepted Privacy Principles (GAPP), a healthcare organization “may outsource a part of its business process and, with it, some responsibility for privacy; however, the [healthcare] organization cannot outsource its ultimate responsibility for privacy for its business processes. Complexity increases when the entity that performs the outsourced service is in a different country and may be subject to different privacy laws or perhaps no privacy requirements at all.”1 In all circumstances, the organization that outsources a business process will need to ensure that it manages its privacy responsibilities appropriately. The healthcare organization (prior to sharing sensitive personal information with a third party) must share its expectations, policies, or other specific requirements for handling protected health information. In return, the third party must provide written agreement to adhere to these requirements.

If you have a friend or colleague who works in a healthcare organization in a department called Vendor Management, or something similar, ask him or her about third-party management. Many healthcare organizations must manage several hundred to perhaps a thousand third parties. In short, managing the organization’s contractual agreements is daunting, and so are the information and privacy concerns with the relationships that include handling PHI. These concerns are within the realm of your responsibilities and are covered in this chapter.

Understand the Definition of Third Parties in the Healthcare Context

Healthcare organizations are typically large employers in a community. Doctors, nurses, administrative personnel, and maintenance workers alike live and raise families in the same community in which they work. Even with the sizeable workforce the healthcare organization employs, it probably requires many external partners to supply, provide, or support the organization with products and services. Within the United States, this business agreement is established through a business associate agreement (BAA), which contracts with a third party to handle PHI on behalf of the healthcare organization (the “Covered Entity,” as defined in HIPAA). In other countries, the same type of arrangement should be outlined in contractual agreements with terms and conditions that outline the expectations for proper information use.

Knowing what a third-party organization is and the significance of the relationship is important for several reasons:

• Assessment of third parties is a preventive security control to help reduce risks.

• Data shows that 23 percent of data breaches happen because of a third-party action to some extent.2

• Healthcare organizations may suffer reputational and financial loss, even if the third party causes the data breach.

• Studies indicate that business associate data breaches tend to involve more affected individuals.3

In Chapter 1, you learned that the reason the term “third party” is used to define the relationship is because the first two parties are the patient and the healthcare organization. Third parties are organizations that provide services in support of the first two parties.

Maintain a List of Third-Party Organizations

The process of managing the risk of third-party relationships begins with having an accurate and comprehensive inventory of the third-party organizations the healthcare organization uses. It is vital that you create and maintain an up-to-date inventory of third-party vendors, suppliers, and contractors with which your organization has business and clinical agreements. Due diligence requires initial review of the terms and conditions of any agreement as well as assessment of the privacy and security practices of the third party. The healthcare organization has an obligation to make sure the third-party organizations they work with have privacy and security controls in place. With that information, you can establish and maintain a database or inventory of the third parties that handle sensitive information.

Within the inventory, you should categorize the third parties according to the levels of risk they present for the healthcare organization. Depending on your organization, you may use categories such as criticality of the relationship, which would consider the size or value of the engagement; the volume and types of PHI the third party handles; and the cost of replacement of the vendor considering competition or proprietary capabilities. Criticality also depends on the location of the third party. The third party could work within the healthcare organization or at another location, including in a foreign country. Some of the impacts of criticality categorization are listed here:

• Frequency of risk assessment of the third-party relationship

• Types of documents required by the third party to demonstrate good security controls (such as SOC 2 reports, ISO certifications, or external penetration testing results)

• Transfer of risk through additional contractual terms and conditions such as increased limits of liability or proof of cybersecurity insurance by the third party

Your inventory of third-party risk management must also consider third parties that use other third parties. This is complicated and hard to determine sometimes, so maintaining the inventory can help. As part of the assessment process, you will ask the third party to disclose any of these downstream business relationships. HIPAA defines the downstream third parties as subcontractors to the business associates.4 Obligations included in the BAA along with any additional terms and conditions in contracts should flow through to the subcontractors.

Third-Party Role and Relationship with the Organization

We covered third parties in healthcare in Chapter 1. In this chapter, we focus specifically on the risks the relationships present as well as your role in assessing and mitigating those risks. Third-party business and clinical relationships expand the capabilities of the healthcare organization and reduce costs—at least those are the objectives. When the objectives are not realized because of an information security event or a data breach, the benefits are quickly eroded. The HIPAA Privacy Rule identifies the reality that healthcare organizations cannot provide all healthcare services and actions autonomously. The Privacy Rule establishes provisions for healthcare organizations to share protected healthcare information with third parties, aka business associates, if there were assurances that the business associate would also protect the healthcare information. The Privacy Rule also stipulates the strict conditions for the information use. The business associate can use the information only in support of the healthcare organization, not for any other use, especially uses in support of the business associate’s other activities, such as marketing.5

Third-party staff may or may not actually perform the work outside of the healthcare organization. Some third-party employees work right beside the employees of the organization, sometimes doing the same work. For example, because many healthcare organizations have implemented electronic health records (EHRs), the work required to connect any existing data systems, engineer the local area network, and prepare physical environments to house the equipment often require additional staffing. Healthcare organizations need to procure the services of contracted staff to help the current workforce accomplish EHR implementation in a timely, cost-effective manner. Some of these services are provided by consultants working onsite, and some are handled remotely by experts who can provision services or transfer data as required.

A sizeable number and/or variety of third parties can support the healthcare organization through a contract or financial agreement while not actually employed by the healthcare organization. Several types of third parties require more explanation, because their relationships with healthcare organizations create impactful scenarios. Within these scenarios, some interesting concerns arise that those who protect healthcare information must appreciate.

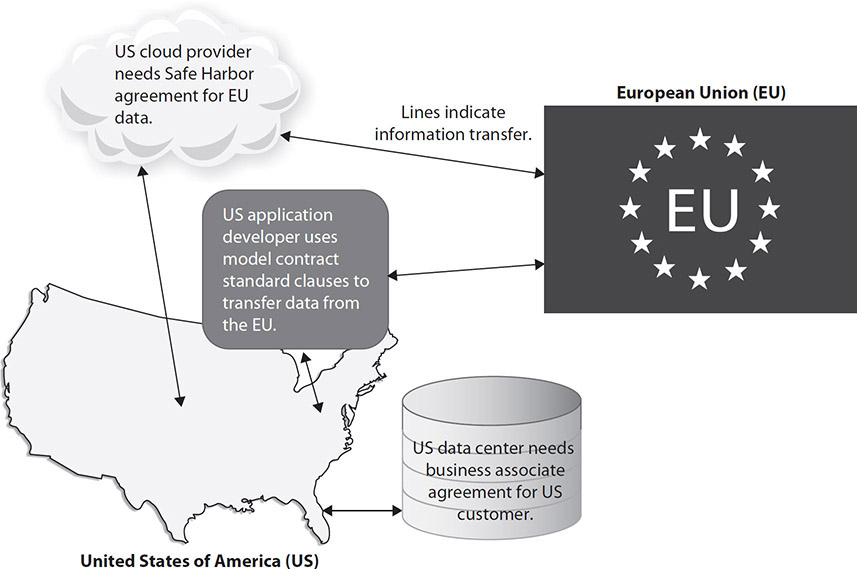

A third-party company in a European Union (EU) healthcare setting can provide services or products for a data controller. Under the EU Data Protection Directive (DPD), this is an allowable relationship as long as a Safe Harbor treaty is in place (for data flow outside of the European Union) or a model contract is in place with already approved clauses from the data authority.6 In the United States, the relationship is focused on the healthcare sector and formalized using a BAA.

Our review of this information here is important, because the relationship between the third party and the healthcare organization may be unusual from the third party’s perspective. If, for example, the third party provides similar services to other industries or handles nonpersonal information, the requirements of regulatory guidance such as HIPAA and the EU DPD can be challenging to meet. Figure 7-1 shows how transferring information within US borders is controlled via BAAs. Transferring data across US and EU borders requires another type of administrative agreement, previously covered by Safe Harbor and model contract standard clauses and now Privacy Shield provisions.

Figure 7-1 Third parties in healthcare providing international support

Outsourcing

Outsourcing services, functions, and products is widely used in most organizations. Internationally, forecasts say outsourcing of healthcare information technology will exceed $61 billion in revenue in the United States by 2023.7 Outsourcing enables healthcare organizations to focus more on their core mission, to reduce costs, and to increase access to highly skilled staff. While the outsourced model extends beyond information technology, a majority of healthcare information privacy and security concerns with third parties resides in the outsourcing of information technology processes.

The model for outsourcing consists of completely transitioning responsibility for the performance of key objectives to a third party. That does not, however, mean the healthcare organization can transition responsibility for privacy and security concerns to the third party. In some cases, the outsourcing is so extensive that the only employee of the healthcare organization who has any contact with the third party is a management staff member. A single healthcare organization employee may be responsible for managing the information risk relative to sharing protected health information. In other cases, the third party is directed by a healthcare organization employee who has the relative qualifications to accomplish the same tasks, but the third party is in place to augment that capability. A great example is a chief information officer who manages the contract and the third-party personnel who provide the entire information technology function for the healthcare organizations. Another example is a patient administration director who oversees all the patient billing functions and accomplishes the process by using a third-party vendor.

The other variance in the total outsourced model is whether the vendor works onsite or offsite. Using the patient billing scenario, it’s likely that the billers work from a location other than that of the healthcare organization. In fact, it is increasingly probable that they work from home. Another information security–related example is the managed security service provider (MSSP) that is hired to provide outsourced monitoring and management of security devices and systems, such as firewalls and intrusion prevention appliances. Revisiting the outsourced information technology example, help desk personnel and network administrators better serve the organization when they are onsite staff. This would facilitate attendance at information governance meetings, which would be appropriate from time to time. Some tasks require the information technology staff to be present rather than remotely accessing the local area network or end-user device.

Staff Augmentation

In addition to totally outsourced services, healthcare organizations can contract for support in a more tailored fashion. The reason staff augmentation is mentioned here is because in some cases, contract employees are viewed more as the healthcare organization’s workforce members. They receive all the same training as staff, and access to information systems is administered along with employed staff. The covered entity (the healthcare organization) may be liable for employees’ actions as well as those of any contract staff supplied by a business associate. Like the rest of the covered entity’s workforce, the covered entity is responsible for the business associate’s adherence with many of the security and privacy controls that are components of the covered entity’s information security program. In other words, the contractor takes day-to-day direction from the healthcare organization rather than from his or her company.

Entry security badging, network access, use of a company-owned computer, and receipt of periodic security awareness communications are all examples of how a contract staff member uses the same security and privacy controls used by employees of the organization. Staff augmentation could comprise a consultant hired to help a healthcare organization implement a clinical application, possibly in the emergency department. The contracted employee may accomplish tasks based on the direct supervision of the shift supervisor. Terrific examples of these types of arrangements are contracted nursing personnel and temporary employees.

An important distinction and implication between an outsourced third-party arrangement and a staff augmentation contract is in how a data breach may be viewed from a regulator’s point of view. A data breach caused by a contract staff member, who is considered a workforce member under US law, may be a liability for the healthcare organization, not the third-party company. To illustrate this, consider another example: a nursing agency that supplies a nurse temporarily to a hospital may not by liable under HIPAA if that nurse causes a data breach; instead, the healthcare organization itself may be deemed liable for the breach. These complicated distinctions require legal review and interpretation. The intent of introducing them here is to emphasize the importance of managing (and assessing) the risk introduced by third parties and how third-party support is delivered.

Outside Legal Counsel

Many healthcare organizations employ lawyers with and without specific healthcare background or experience as part of their internal staff. But even when organizations have employed legal representation, they may choose to retain (on a contract) the services of legal counsel not employed by the organization; these are called outside legal counsel. These legal professionals and firms perform many different types of services, from reviewing contract language and the content of compliance programs (such as the information risk management program), to reviewing other administrative controls the healthcare organization wants to make sure it is properly managing. Outside legal counsel may also help the organization defend itself in malpractice claims, defend against data breach cases (in the United States), perform forensic investigations, and otherwise represent the healthcare organization in litigation. In the context of managing outside counsel as a third party to the healthcare organization, the same types of risk management review must be done for any outside counsel that handles PHI as for any other third party performing similar data use services. (And a good outside legal counsel will advise their customers to do as much!)

Third-Party Risk in the Cloud

Beginning with one of the emerging third-party relationships in healthcare, the cloud provider example enables you to examine several important considerations. Think about a cloud service provider that supports a healthcare customer as well as customers in retail, banking, or education. If the transfer of data includes collecting, storing, or transmitting protected health information, the cloud provider must meet HIPAA compliance standards in the United States. It must also be able to provide documentation of its independent audit report. This is in addition to any requirements the cloud provider may or may not have with its other customers.

The move to cloud services for healthcare organizations is happening internationally. There are good reasons for this, such as unprecedented pressures to reduce costs, improve health outcomes, and respond to regulatory changes, to name a few concerns. Cloud solutions promise to help healthcare organizations implement complex health information technology (IHIT) systems at a fraction of the cost. NIST SP 800-144, Guidelines on Security and Privacy in Public Cloud Computing, provides a terrific synopsis of the upsides and downsides of cloud computing from a privacy/security perspective.8 Benefits include improved staff specialization and resource availability, while Internet-facing systems and multinet hosting arrangements introduce new vulnerabilities (for some customers).

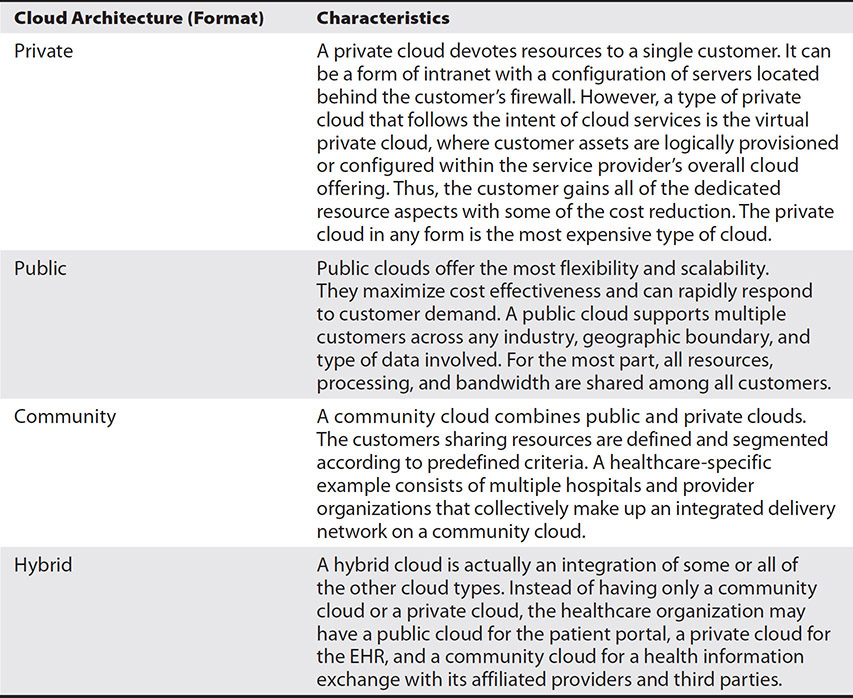

Table 7-1 describes common examples of cloud computing service delivery models to help illustrate the variety of products and services available in cloud computing. Table 7-2 describes the formats that cloud computing can take. In sum, cloud computing offers convenience, rapid innovation, and lower total cost of ownership.

Table 7-1 Cloud Computing Models

Table 7-2 Cloud Computing Formats

With an understanding of the types of cloud offerings, you can look at some scenarios in which healthcare organizations may face challenges using them. This means that information privacy and security issues arise when you consider a third party and a type of cloud to use, and as you evaluate that relationship over time.

Although it’s true that cloud providers introduce levels of risk to healthcare organizations in terms of information privacy and security, as described in Chapter 5, the risk can be worth it because cloud computing does offer measurable benefits. Most healthcare organizations do not have or desire to have in house the capabilities that cloud providers can quickly provide (such as large storage facilities, processing power, resource provisioning, and network redundancy). Although healthcare organizations need to understand the cloud computing process to assess risks, many cloud providers do not fully understand the unique privacy and security pressures for healthcare. This lack of understanding can be a source of information risk. The healthcare organization needs to ensure the cloud provider can meet applicable regulatory standards. If it cannot, the organization must continue to evaluate cloud providers until it finds one that can comply and deliver all the benefits and standards required.

In sum, healthcare organizations must carefully consider the issues and evaluate potential cloud solutions before leaping into binding agreements. Healthcare organizations that do not heed this advice will encounter problems when regulators remind them that compliance cannot be outsourced to a third party—in this case, to the cloud. What your cloud provider does or does not do will be your responsibility in terms of privacy and security of sensitive information.

Third-Party Risk in Data Disposition

In the information management lifecycle, destroying or disposing of data is the final step. It is also one of the most vulnerable processes.9 When data is no longer needed, it often receives less protection because the organization tends to relax control. In many cases, the data disposition, destruction, or disposal process is conducted by an outsourced company that specializes in this function. Some examples include paper shredding, electronic media erasure, and hardware recycling.

Whether the data is in a paper or an electronic format, a healthcare organization needs to ensure that the PHI it marks for disposition is safeguarded all the way through the final steps of making it unreadable and indecipherable. Otherwise, theft and unauthorized disclosure can occur as PHI is taken from loading docks, where medical records await pickup from the data disposition company, for example. As many personal computers are donated to community organizations and schools, a data disposition company may have authority to make the donation, but any sensitive information must be completely removed from the hard drives. A healthcare organization must conduct third-party risk assessment and auditing oversight to make sure its sensitive data is not disclosed under these types of scenarios. A certification of destruction from the third party would be required when data is disposed.

Third-Party Risk in Nonmedical Devices

A special category of third party has evolved as printers, faxes, and scanners have become commonplace in healthcare environments. If an organization is not careful, these devices can be sources of a data breach. Because these devices copy, e-mail, and transmit data by changing paper documents into electronic images, they often store data on local storage media. A third-party company contracted to maintain and service these devices may not know the nature of the data the hard drives contain. But if it is PHI, that data may leave the healthcare organization as the devices move to be serviced or replaced. Similar to the data disposition companies, nonmedical device repair and supply companies must be under contractual obligation to protect the healthcare information that may be present on these devices. This means proper destruction, disposal, and reuse provisions must be in place. It also means the healthcare organization has risk management responsibilities with respect to the third party that manages nonmedical devices that includes auditing compliance with the use of PHI.

Health Information Use: Processing, Storage, Transmission

Your role includes helping to establish and monitor the technology and procedures used for processing, storage, and transmission of any PHI that a third party may handle for your organization. In some cases, the responsibility will entail designing interconnections and implementing new security controls. In other scenarios, you may need to review and evaluate already existing safeguards implemented by the third party.

In all cases, the third-party entity will receive terms and conditions in contracts or legally binding documents. In addition to ensuring that your organization and third parties adhere to all applicable regulatory requirements, you will be responsible for informing and enforcing the requirements to the organization as well as the third party. For example, the authorization for access to data and systems must be limited based on your organization’s requirements.

To emphasize the important concepts here with a practical example, we’ll add another common third-party relationship. Using HIPAA as a regulatory guide, a covered entity is required to enter into a BAA with a cloud service provider. It does not matter what type of service model the covered entity uses, because the principles remain the same. The cloud service provider is a business associate and is subject to HIPAA regulations, just like the covered entity.10

Additional contractual obligations can be made where the cloud service provider must ensure services in a service level agreement, often supplemental to BAA terms and conditions, to include the following:11

• Availability of data and systems.

• Business resiliency and support of contingency operations.

• Performance of backup sufficient to restore and recover successfully from disasters.

• Terms for data disposal or return to customer after the agreement ends or when the data is no longer needed. In HIPAA and GDPR, for example, the requirement for adequate information protection by the third party extends beyond the contract life if the third party has to maintain the data for a valid reason.

• Expectations for third-party security responsibilities.

• Limited use and authorized disclosure provisions as well as retention guidelines.

If you are working for the covered entity, the considerations outlined here are expected to be part of your ongoing risk assessments and risk management program. In international healthcare organizations, the practice of assessing risk and outlining the expectations of the third party to adhere to at least the same regulatory and organizational policies you, as the customer, does is nonetheless imperative.

International Regulations for Data Transfer to Third Parties

Related to international trade implications, the variations in regulatory standards pose concern for healthcare organizations transferring information to third parties internationally. US healthcare organizations are subject to HIPAA even if PHI is stored by a third party (including cloud providers) in another country that may not have the same data geographic restrictions, auditing, and breach notification requirements. According to the EU DPD, and later in GDPR, international concerns for auditing and monitoring are similar, in that data controllers must request the logging of processing operations performed by the provider.

In the United States, HIPAA codifies the requirements a bit more in that the healthcare organization must ensure that third parties adhere to security controls for authentication, error reporting, breach notification, and accounting of disclosures. The healthcare organization must ensure that any international third party follows applicable regulations if a breach of data occurs. The HIPAA requirement for patient notification in certain circumstances, for example, is not relaxed simply because a healthcare organization stores data outside of HIPAA jurisdiction.

Canadian and EU healthcare organizations have additional privacy concerns even beyond the need for Safe Harbor or model contract language. These governments and their domestic healthcare organizations in particular have expressed concern with cloud providers that collect, store, and transfer information to and from the United States. The US Patriot Act makes it undesirable—and even illegal—for Canadian and EU healthcare organizations to use US-based cloud service providers, because US law allows authorities to look at their PHI in certain circumstances. The 2001 US Patriot Act was fortified by the 2018 Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act. With respect to the current GDPR, EU citizens’ data stored in US cloud provider computers is subject to US government access on demand.12 That said, remember that under all leading privacy and security regulations, access to PHI has provisions for legal authorities to access with additional patient consent. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Regulatory of Investigatory Powers Act, much like the US Patriot Act, mandates similar levels of government access.13

Unauthorized Disclosure of Data Transferred to Third Parties

This may seem obvious, but third parties have a significant impact on healthcare organizations because they cause a high percentage of data loss and data breach. Even with robust risk management from the healthcare organization, unauthorized disclose still happens. With proper contracts and legal agreements in place, financial liability can be properly applied to the third party. But from a reputational perspective, the healthcare organization is still affected negatively. For instance, a patient billing company receives files and has access to databases of healthcare information. If the third-party offices are burglarized and computer equipment is stolen, the third party may have to pay the fines and penalties for a breach. But patient notification will be done by the healthcare organization. Patients will probably not make the distinction between responsible parties.

Apply Management Standards and Practices for Engaging Third Parties

NIST refers to the management of third-party risk as “Cyber Supply Chain Risk Management” (C-SCRM).14 The process is similar to overall risk management lifecycles that include identifying, assessing, and mitigating information risks. In this case, risk management is tailored to address risks incurred by outsourcing and contractual relationships that support the healthcare organization. A simple way to start this discussion is to remember that building security controls into the relationships at all phases of the third-party arrangement or supply chain lifecycle is much better than trying to address issues after the contract or agreement is in place. Some general phases in the lifecycle include the following, which are depicted in Figure 7-2:

Figure 7-2 General phases in third-party risk management lifecycle

1. Planning Understand the business requirements and help design the data use specifications with any information transfer needs.

2. Selection Perform due diligence initial risk assessment activities during evaluation of third parties.

• Make sure the third party has an information protection program aligned with privacy and security regulations (HIPAA, EU DPD, ISO, PCI, and so on).

• Make the effort to review any objective assessments by qualified auditors (SOC2 HITRUST, ISO 27001 and so on).

• Check reference accounts to understand past performance for the third party.

• Visit the third party’s facilities.

3. Implementation Select connection controls or a trust model for the interconnection, including secure data transfer technical controls such as encryption plus identity and authentication management.

4. Monitoring Assess compliance with the contract terms that will consist of periodic risk assessments, reviews of service level agreements, and performance satisfaction ratings. As part of the contract, a right to review and audit should be present.

5. Termination As third-party relationships end, security and privacy concerns must be included in the decommissioning of systems and disposition of any data that the third party no longer has authorization to access or store.

Relationship Management

In addition to risk management frameworks that help healthcare organizations oversee third parties that handle PHI, several other types of documents and agreements are necessary. These help the healthcare organization communicate requirements, evaluate performance, and hold all parties accountable for compliance. Without the use of one or more of these administrative controls, healthcare organizations have little reason to expect a third party will apply appropriate safeguards or be responsive enough, particularly if a healthcare organization’s expectations exceed those of the third party’s customers from other industries. We outlined some examples of the major types of relationship management tools in Chapter 3, including SLAs, contracts, and interconnection security agreements.

We have introduced and explained several leading risk management frameworks that healthcare organizations can use to evaluate and manage internal risk. These same tools can be used to evaluate and manage third-party vendors. The same risk assessment and remediation work should be done for each external vendor with respect to their processes, policies, and controls in place to protect your information. We will not repeat the information here concerning the leading risk management tools such as the NIST RMF, HITRUST CSF, or the ISO 27000 family of standards, but keep in mind that these tools can all be applied to third parties that handle PHI for your organization.

One leading risk management framework that is presented as a vendor risk-specific framework is the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) in the US Department of the Treasury.15,16 We mention this because the framework is used by many leading assessment organizations internationally, such as the Santa Fe Group’s Shared Assessments. Shared Assessments was established in 2005 and is present in more than 115 countries worldwide (mostly in the financial industry).17 It specializes in assessing third-party vendors that handle sensitive information. You can see some similarities in its lifecycle risk management model compared to those already discussed. A couple of differences are in contract negotiations (SLAs, for example) and in the termination phases. The OCC lifecycle (see Figure 7-3) also integrates some overarching concepts that fit into the other risk management frameworks we have covered. Here are some examples:

Figure 7-3 OCC risk management lifecycle

• Oversight and accountability Of course, someone from the healthcare organization must be responsible for the contract. They should be accountable for results and be integrated into the information governance structure of the healthcare organization.

• Documentation and reporting As part of the information governance structure, the accountable person must be able to communicate relevant details, events, and performance measurements. All of this must be documented and the documents retained.

• Independent reviews In addition to periodic assessments and audits, both onsite and remotely through vendor self-assessment, an objective independent assessment is a best-practice idea as well. Remember that a solid risk management component is to access and review all objective audits of the third party that they already maintain. For example, give credit for FISMA ratings, ISO certifications, SOC 2 assessments, and HITRUST audit results.

Determine When a Third-Party Assessment Is Required

Each organization will need to determine when and how it wants to assess its third parties. Of course, some regulatory pressures may influence the frequency. We have established that an initial assessment is essential. After that, most third-party relationship frameworks indicate that an annual frequency for review is sound practice. In any event, organizational standards for vendor management will set the expectations, which will factor criticality of the service, sensitivity of the data, or level of risk to the healthcare organization because of the third-party relationship. The conduct of the assessment can vary as well. The organization may choose to allow a self-assessment reported to the healthcare organization via a questionnaire or an interview through a remote assessment, or the healthcare organization may insist on an onsite audit. In all cases, updating and provisioning of a current copy of any information risk–related assessment documents such as the SOC 2, ISO 27001, or an external firm’s penetration test reports would also be necessary.

Organizational Standards

The proper approach for managing third-party information risk is to start with an enterprise-inclusive perspective. This means that although information protection experts may lead or design the processes, it takes many stakeholders from within the organization to establish a strong third-party information risk program. Personnel from clinical and business functions, along with corporate departments such as finance and procurement, must join together to create a program that builds in risk management rather than bolting it on after a third party has been selected (or worse, after the contract is signed). Add to this multidisciplinary team legal and vendor management functions, and you can meet the objectives of good risk management in this area. This team, which can include people from areas not specifically mentioned and based on specific third-party relationships, will contribute to development of the request for proposals, contract terms and conditions, and business and clinical objectives for the relationship.

Here are some specific components of the organizational standards:

• Be practical. Overly complicated processes may be seen as an impediment, and some stakeholders may be motivated to circumvent the process or parts of it.

• Be consistent. Exceptions should not become the rule. If there is a perception of favoritism or excessive waivers for certain business or clinical areas, this may become another justification for working around the standards.

• Streamline use of third parties. Many organizations have large portfolios of vendors. Where one vendor can satisfy multiple stakeholders’ requirements, the costs of risk assessments and oversight can be reduced. Overall risk can be reduced where high performing vendors are used for multiple requirements too.

• Set good standards. Choose those standards that are aligned with industry frameworks such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework that includes supply chain management and ISO 27001 third-party and processor controls. This helps the organization meet or exceed regulatory requirements too.

• Follow the third-party risk management lifecycle. Remember that the process begins with planning, goes through termination, and begins again with a replacement solution. Information protection has a role in every phase of the lifecycle.

This approach describes how an organization can establish processes that align to internal policies. However, the emphasis is not on fitting a third-party relationship selection into an information protection constraint. It is the opposite. By involving multiple stakeholders in the organization and conducting due diligence, understanding the risks incurred, performing ongoing monitoring, and being ready for unintended incidents, the business and clinical stakeholders can obtain the products and services they need. At the same time, the risk to the healthcare organization can be reduced to a tolerable level.

Triggers of a Third-Party Assessment

Throughout this chapter, we covered several routine times when a third-party assessment would be required or beneficial. In addition to regularly scheduled events initially and annually, sometimes an out-of-cycle assessment may be needed. Keeping in mind considerations for the costs of additional assessments, criticality of the third party, and the sensitivity of the information that is exchanged, the following are some events that can trigger a third-party assessment:

• Failure to perform to the contract or SLA

• A data breach relative to another organization

• New personnel in key positions

• Information outage and unsatisfactory disaster recovery

• Leadership inquiry or interest item

• Possible recompete for a new provider

These triggers are facilitated by ensuring that a right to audit is included in contractual terms and conditions. The BAA should include this condition for US healthcare organizations.

Support Third-Party Assessments and Audits

A primary role of a healthcare information privacy and security professional is to help organize and conduct the required assessments and audits of third parties. The overall consideration for a third-party audit will be whether the activity will be conducted. Based on factors such as how much risk the third party introduces or how familiar the third party is to the organization, one of the following assessment approaches may be useful:

• Self-assessment The vendor responds to a survey provided by the healthcare organization.

• Onsite The healthcare organization’s employee observes and interviews the vendor onsite.

• Remote With or without a self-assessment, the third-party vendor is reviewed using relevant third-party material such as past performance attestations, marketing material, any legal proceedings against the third party, and other considerations.

• Hybrid This uses a combination of onsite and offsite approaches.

These approaches can be useful for the initial assessment in the planning or selection phase and in the annual or periodic assessment process. If a third-party vendor triggers an out-of-cycle assessment because of a potential data loss incident, a different approach from these assessments can certainly be chosen. That said, because the SLA or contract is a risk transference vehicle, it can help determine the appropriate type of assessment approach.

The next step may be your biggest obstacle in participating in the third-party risk assessment process. Even though the third party is not part of the healthcare organization, no special considerations apply to reduce standards that apply internally to the organization. The third party must have all the controls in place that are required by contract and by law. For instance, if there are information security and privacy training requirements, it is not acceptable to excuse the vendor from them. Sometimes healthcare organizations are tempted to give credit to the vendor for training provided by the healthcare organization. Unfortunately, under most circumstances, that does not meet requirements.

Remember, for example, that a component of the required training deals with the third-party organization’s policies and procedures, not those of the healthcare organization. Another example is not having access to the third party’s facilities. If within the contractor SLA the negotiated terms and conditions permit access by the healthcare organization to visit the third party’s onsite premises and conduct an inspection, that should be part of the audit. Relaxing that standard because of reluctance of the third party to support the inspection adds undue risk to the healthcare organization.

When faced with third-party vendors that do not comply with assessment and audit requirements, your role in the organization will be to document findings and communicate them to more senior leadership. This is an incredibly important role. Properly organizing these types of assessments (using the correct approach, using valid assessment tools, following contracts, and communicating all findings) is a linchpin to reducing the risk of third-party data breaches. Once again, you know that the results of several industry surveys demonstrate that third parties commonly cause data breaches. The underlying causes tend to be the lack of oversight we have just described and desire to avoid.

Information Asset Protection Controls

During the risk assessment process, the effort will be to understand the security and privacy controls the third party uses. This can come from assessment documents or audits that detail the frameworks or control sets. You may also choose to use a survey to ask about the frameworks or to obtain answers about specific controls. Regardless of your chosen approach, particularly the survey, you should be aware that vendors are asked to fill out a lot of questionnaires. If you use a standard questionnaire, the vendor may have already completed it for another customer.

Here are some valid and popular risk assessment tools:

• Center for Internet Security (CIS) Critical Security Controls This tool is effective because it seeks information from the third party based on security controls that mitigate the most common or prevalent attacks. The selection of the Top 20 controls is based on historical data and firsthand knowledge of security experts concerning what security controls reduce the most risk. The Critical Security Controls are drawn from the leading industry resources, including the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, NIST SP 800-53, ISO 27000 series, and regulations such as PCI-DSS, HIPAA, and FISMA.

• Consensus Assessments Initiative Questionnaire (CAIQ) The Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) developed the CAIQ to assess the information protection controls specific to cloud service providers and third parties that host data centers.

• ISO 27001 Questionnaire A precursor to ISO 27001 certification, organizations may have completed the questionnaire based on the ISO 27001 body of controls, yet did not seek certification. This completed questionnaire would be sufficient to document a robust information protection program provided the responses were satisfactory.

• NIST SP 800-171 Rev. 2 This publication is applicable because NIST SP 800-171 Rev. 2, Protecting Controlled Unclassified Information in Nonfederal Systems and Organizations, is a standard for government agencies to use a commercial third-party entity as a supplier of information services. Used with NIST SP 800-171A, Assessing Security Requirements for Controlled Unclassified Information, the guidance extends requirements such as NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 4, Security Controls, to nongovernmental agencies in a manner that translates to the commercial sector while maintaining confidentiality, integrity, and availability to sufficient standards for the government agency.

• Standardized Information Gathering (SIG) Questionnaire An industry consortium of accounting firms, corporations, and information technology firms make up the Shared Assessments group, which authored the SIG questionnaire to provide a standardized, repeatable, and reusable assessment document that appraises 18 different risk domains.

• Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (PCI DSS) Questionnaire In organizations that handle credit cards or are considering establishing a third-party relationship for such services, the PCI DSS questionnaire can help gather data about security controls relevant to the PCI standards.

Healthcare information is a valuable commodity. With the reliance on third parties to handle PHI on behalf of the healthcare organization and the fact that so many data breaches result from third-party mishaps, their proper assessment is vital. The use of one or more assessment tools may make it a little easier for the third party to comply. However, in reality, the industry-tested and validated questionnaire can assist you with the daunting task of initial assessment, ongoing monitoring, and periodic reassessment, because it is probably ready when you need it.

Compliance with Information Asset Protection Controls

The healthcare organization needs to assess whether or not the third party is adhering to information asset controls. As we have described earlier, the healthcare organization may choose to use a questionnaire to survey the third party to assess compliance. Questionnaires have a drawback, however, in that they may lack objectivity because third parties themselves are filling them out. Because the healthcare organization must conduct due diligence to assess compliance with information protection, a questionnaire may be insufficient based on the criticality of the vendor, the sensitivity of the information, and the value of the engagement.

A complementary approach is to use external audits or results of assessments of the third party. These results can increase confidence in the information protection programs of the third parties. Here are some examples of external assessments and audits you may look for and accept in addition to or in place of a questionnaire:

• Service Organization Controls (SOC) report This series of assessments designed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) is meant to demonstrate the effectiveness of security controls. A SOC 2 is most likely the type of SOC report you will see, because it provides a view of security control effectiveness over a period of time. It can be used to address privacy, security, availability, processing integrity, and confidentiality individually or in combinations that can include all components. There are other versions of SOC—SOC 1 and SOC 3. The SOC 1 involves primarily financial controls and evaluates control functionality at a particular point in time. The SOC 3 is the same assessment as the SOC 2 with the same components, but the report is suited for a general audience.

• ISO certification Some companies want to demonstrate trustworthiness to signal that their commitment to information protection exceeds the satisfaction of the ISO 27001 assessment tool mentioned earlier. These organizations seek certification by external certification bodies under the ISO information security certification process.

• Health Information Trust Alliance (HITRUST) Within US healthcare organizations, including business associates, HITRUST Common Security Framework (CSF) certification has grown in recognition and credibility. The CSF is aligned with the top information security frameworks and standards created by NIST, ISO, and HIPAA. HITRUST also incorporates relevant Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), PCI DSS, and several US state information security and privacy laws, for example. As more healthcare organizations use and require the CSF certification, the tool is useful as a benchmark in the industry. The CSF can be used to self-assess, and through certification, an external assessment can be made by a qualified assessor.

Some organizations maintain a need to conduct a self-designed questionnaire in light of the examples of standard tools. There are reasonable concerns with using the tools or accepting completed questionnaires that appear to be generic responses. In such cases, a combination of self-created questionnaires and acceptance of precompleted assessments from external entities can be an acceptable compromise. The key consideration is that the healthcare organization achieves the objective of gaining confidence that the third party is capable of compliance with information protection requirements.

Communication of Results

During the risk assessment process, you may find issues. There are two distinct lines of communication you will use to communicate these results. First, the stakeholders in the activity will need to be informed of security control findings, lack of assessment material, or unacceptable contractual language. These gaps may indicate increased risks, and in some cases, the findings may prevent or prohibit the organization from entering into a third-party relationship with the supplier or vendor. That may be unpopular, but it’s better to know early in the planning phase before selection.

The other communication requirement is with the third party itself. As you uncover issues, it is best to share concerns with the third party. The intention is to gain clarity if there are questions and to determine if remediation is possible to facilitate selection of the third party for contracted services. It is frustrating when a third party disagrees with your findings. However, if you base your requirements on industry validated assessment tools such as those described in this chapter, you can be confident in your assessments. That resolve leads us to the topic of remediation efforts in which you, as an HCISPP, will participate.

Participate in Third-Party Remediation Efforts

At times, you may be required to participate in third-party remediation efforts, such as remediation efforts that result from the risk assessment process. When you find issues and communicate them with the third party, the remediation process begins, and you will be required to track the items to completion. The third party may need assistance in designing proper controls or finding solutions to close controls gaps. As an HCISPP, you may be able to provide recommendations based on your subject matter expertise; there may be debate, however, as to whether the recommendations equate to free consulting services. The remediation of findings ultimately benefits your organization, in that a third-party relationship is established with sufficient information protection controls in place. As we have mentioned, this reduces risk and lowers potential for negative financial, operational, reputational, and clinical impacts.

Another opportunity for third-party remediation activities is after a cybersecurity event or a data breach occurs. These events are characterized by a higher sense of urgency and priority. Your role in these events will be aligned with contractual and legal obligations. Starting with a third party’s requirement to notify your organization of a breach, remediation begins immediately. Coordination to contain the crisis and notification of your patient population should be part of the process. Assuming that the event prompts an out-of-cycle risk assessment to determine root cause and discover any security control ineffectiveness, your role will begin to resemble the routine remediation procedures we described in the preceding paragraph. Tracking and closing security control findings will be required. However, in contrast with routine risk assessment and control remediation, with remediation efforts post breach or after a cyber-attack, the pressures to remediate the issue to the satisfaction of your organization and external regulatory agencies add pressure, scrutiny, and importance.

In some cases, an official remediation order from the government, legal authorities, or regulators will dictate the actions and pace of change the third party must satisfy. Your role may be to participate in assuring that your organization is informed of progress. Of course, that is assuming that after a breach or cyber-attack, your organization did not cancel the contract and end the relationship with the third party. In that case, you may be called upon to assess and recommend continuing the relationship or ending it through the use of a contract termination clause (that you may have helped negotiate, by the way).

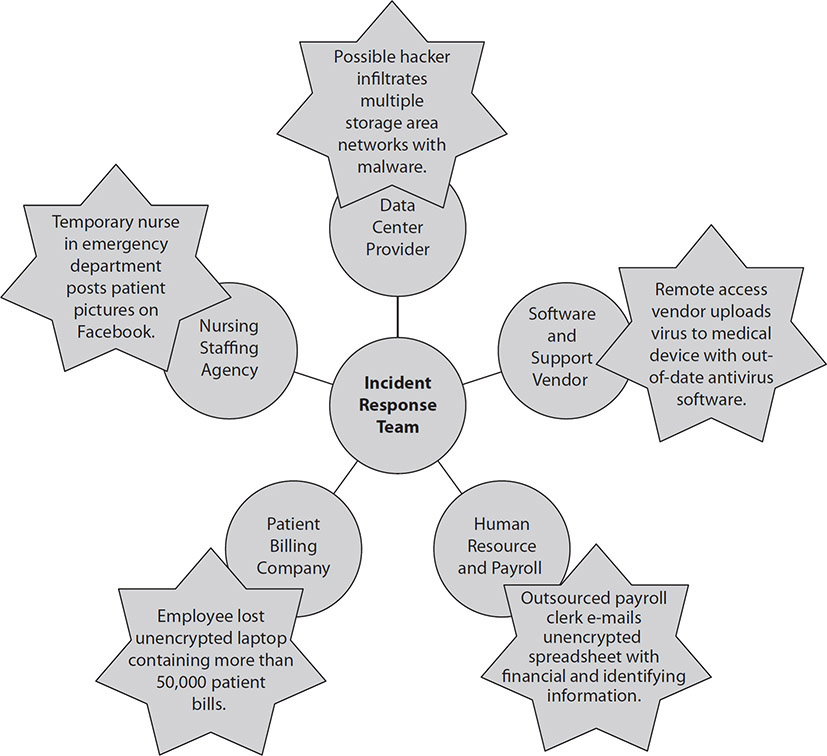

Respond to Notifications of Security/Privacy Events

For incidents caused by third parties, the HCISPP will be expected to lead or participate in the healthcare organization’s response, communication, and remediation activities. A large percentage of incidents are caused by improper handling of PHI by a third party. According to the Ponemon Institute (a privacy and information management research firm), in its 2015 “Fifth Annual Benchmark Study on Privacy and Security of Healthcare Data,” third-party organizations accounted for 39 percent of all breach cases.18 These remain the most costly form of data breaches because of additional investigation and consulting fees. The prevalence of third parties causing data breaches has been noted around the globe. Keep in mind that the healthcare organization’s incident response team may activate and oversee the overall incident investigation. Based on contractual obligations and legal requirements, the third party will have significant responsibility and should bear the costs of the investigation (and notifications, if required). Figure 7-4 depicts the coordination with third parties that the incident response team may need to oversee.

Figure 7-4 Incident response team and third parties

Internal Processes for Incident Response

If the third party suspects a data incident is underway that has originated in its organization, as it complies with contractual obligations and legal requirements, it must ensure that initial reports are sent to the healthcare organization in the prescribed timeframes. These reports may incite the healthcare organization to activate its incident response team. Additional responsibilities the healthcare information security and privacy professional can expect to perform are as follows:

• Coordinating with the third party during the investigation

• Corroborating any findings of the third party against the healthcare organization’s environment

• Identifying, in the case of malware, infiltration of the healthcare organization, which may also be evident as attackers target multiple hosts

• Escalating the incident within internal reporting processes (senior leadership, vendor management, and so on)

• Assisting the third party with all communications to be made in community updates and notification activities to the media, regulators, and affected individuals

• Leading the notification responsibilities or delegating the actions to the third party

• Ensuring that third-party actions adhere to contractual obligations and legal requirements

• Making sure notifications are made in the prescribed manner

• Minimizing disruptions in services

As with an incident that originates inside the healthcare organization, the third party will progress to the containment, eradication, and recovery phases. The healthcare organization will closely monitor the progress. Whether the incident response team is activated or a third party determines whether the evidence indicates a data breach, communication with the healthcare organization must continue. Other pertinent responsibilities in monitoring the third-party progress may include the following:

• Assisting with digital forensics to preserve evidence

• Continuing to coordinate any media press releases and notices to regulators and affected individuals once the incident is determined to be a data breach

• Vulnerability scanning to ensure proper eradication and recovery if there are interconnections of systems between the third party and the healthcare organization

• Documenting costs to the healthcare organization as they apply to any downtime, assisting in managing the third-party activities, and checking performance against service level agreements

When the incident occurs, the third party should follow a process that is similar to that of the healthcare organization. Lessons learned and additional training on previous events should be incorporated into the organization’s risk assessments and information security programs. Doing this may help to prevent the next problem and reduce incidents by third-party organizations.

Following are some responsibilities to consider in the post-incident phase:

• Including previous incidents in the next risk assessment done by the healthcare organization

• Updating any contractual documents and service level agreements

• Providing any financial data relative to investigation, oversight, and downtime to internal management for possible reimbursement from the third party

• Incorporating third-party incidents into healthcare organization training and awareness as well as incident response team training scenarios

As much as possible, an incident response plan must integrate procedures that handle events originating at a third-party supplier with a holistic perspective. Consider the third party as an extension of your organization. The incident response plan that integrates internal stakeholders inside of business continuity plans, disaster recovery, or organizational crisis management teams is not just for internal events. It is common to activate internal response teams to manage the organization through an event that happens to a third-party supplier.

Relationship Between Organization and Third-Party Incident Response

There is an old proverb that we can paraphrase: “The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second-best time is today.” Drawing from the proverb, the relationship between the organization and third-party incident response must be established and tested before the need for the incident response occurs. A plan is needed that assigns clear roles and responsibilities for key personnel who are leading the incident response for each organization. The plan should be part of the overall negotiation and review before a contract is signed. If that did not happen in your organization when the third-party contract was signed, plant the “tree” today: Develop the plan and a schedule to test the plan with your current critical third-party suppliers before you need to respond to an incident. It is chaotic and ineffective to develop procedures and assign roles and responsibilities during a cyber event or data breach.

Make sure that you actually review the current plans for incident response that the third party uses. You need to understand who is responsible for certain actions and when those actions may occur. For example, a security manager may be the responsible party to notify you when the third party suspects a potential or actual data breach. A senior manager in the third-party organization may have the role of escalating communications to regulators or other external entities, including the public media. You should ensure that your and the third-party’s plans align with regard to the timing of incident responses and input from your organization. Imagine a third party announcing a data breach to the local news station before you have had the chance to activate your organization’s incident response team and escalate communication!

Breach Recognition, Notification, and Initial Response

A third party is probably not going to notify you of a security issue until they are sure that a data breach has occurred. They may be contractually obligated and otherwise legally obligated to notify your organization, but the reality is that they are probably going to do some initial investigation and containment before they notify you. Breach recognition requires some certainty. Making notifications and sharing information only to determine there was no unauthorized access or data loss may sound like good news, but after the process has started for initial response, frustration increases, costs are incurred, and credibility is diminished. In sum, make sure a breach has actually occurred before you announce it.

In the European Union under GDPR, Article 33, the notification rules stipulate that data controllers must notify the data protection authority within 72 hours. The same section mandates that data processors, third parties to the data controller, must make notification to the data controller immediately upon determination of a data breach.19 If doing that is infeasible, some exceptions exist, but the reasons for delay must be disclosed. The imperative to notify individuals is less stringent. The data controller is permitted to determine whether the data breach is likely to affect the privacy of the individual adversely. If the breach has adverse impact, Article 33 directs the data controller to notify the affected individual “as soon as possible.” The data authorities intend to keep individual notifications to those with adverse impact versus over-notifying individuals and creating notification fatigue.

HIPAA poses similar timeframes and guidelines for initial notification of data breaches. The law adds complexity around the size of the data exposure. If it involves more than 500 records, the healthcare organization must notify the HHS OCR within 60 days, or sooner. Notification of affected individuals must also fit within that timeframe. When less than 500 records are involved, the notification starts with the affected individuals within the 60-day timeframe. For volumes of data breaches under 500, each one is reportable to the OCR, but only on an annual basis at the beginning of the calendar year. For any amount of records, a third party or business associate must notify the covered entity healthcare organization within 60 days.20

As we move into the next section, we will explore notification more thoroughly. It is important to consider and determine who will actually do the notification. This happens at or before contract signature in the best case. Going back to the point made in the first paragraph of this section, you must be certain that a data breach has occurred before the required notifications occur. In addition, determining who is responsible for making notifications depends on who is being notified—external regulatory agencies, the media, or affected individuals. The fact is that notification may be the responsibility of a third party other than your organization. Many cybersecurity insurance policies include provisions for these services and they are prenegotiated. The costs of making notifications will also need to be understood and written into the contracts, particularly when those services are not covered in cybersecurity insurance policies or when no policy exists.

Respond to Third-Party Requests Regarding Privacy/Security Events

Responsibilities may be limited to internal activities culminating with notification of senior management. Regardless of the limitations, your understanding of how the healthcare organization leadership must interact with external agencies during and after an incident will be valuable. What follows is an overview of how that interaction should happen and under what conditions.

Law Enforcement

Once an incident is determined to be a crime, senior leadership will notify law enforcement. In the United States, this includes authorities such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Secret Service as well as local and state agencies. Internationally, relevant law enforcement agencies will have jurisdiction and should be notified. Law enforcement can assist in the investigation and advise the organization on evidence collection. Law enforcement also can help determine when additional notification actions may take place, such as delaying notification if it would interfere with an ongoing investigation.

EU Data Authorities

The notification responsibilities in the European Union relate to electronic information and are founded in telecommunication industry regulations. This is changing as notification has been integrated into Europe’s overall privacy doctrine. Currently, when a data breach occurs, the data controller (healthcare organization) is mandated to notify the appropriate EU nation’s supervisory data authority of the personal data breach. When it is determined that the breach presents a high risk to the affected individual, the data controller is required to make personal notifications.

Affected Individuals

In the United States, healthcare organizations must notify individuals (of any number) once the incident has been evaluated and there has been sufficient risk of disclosure. The organization determines the risk of disclosure through a specific risk assessment process, described later in this chapter in the section “Risk Assessment Activities.” If the risk analysis confirms that the incident is in fact a data breach, healthcare organizations in the United States are mandated to notify affected individuals. Even the form of the notice is prescribed. The individual notice must be made within 60 days and must be in written form, delivered by first-class mail or, alternatively, by e-mail if the affected individual has agreed to receive such notices electronically. When the contact information is out of date or incorrect for 10 or more people, the healthcare organization must take alternative measures. It can post the notice on the organization’s web site or engage the media to broadcast the information.

The notice in any format must include the following elements:

• A description of the breach

• Types of information that were involved

• What affected individuals can do to reduce chances of additional harm

• Recommendation to obtain a credit report, monitor bank accounts, and so on

• A brief description of what the healthcare organization is doing to investigate the breach, mitigate the harm, and prevent further breaches

• Contact information for the covered entity, including a toll-free number for individuals to call to determine whether they were affected by the breach

In the European Union, as the proposed notification rules gain acceptance, the imperative will be to notify the supervisory authorities within 24 hours. The imperative to notify individuals is less stringent, however. The data controller is permitted to determine whether the data breach is likely to affect the privacy of the individual adversely. If the breach has adverse impact, the data controller may notify the affected individual. The data authorities intend to limit individual notifications to those with adverse impact versus over-notifying individuals and creating notification fatigue.

Media

The media plays a role in broadcasting the nature and extent of the breach. It will also help notify individuals and the community about actions they can take to protect themselves. In the United States, healthcare organizations are required to notify the media (newspapers, television stations, and so on) when the breach impacts 500 residents of a state or jurisdiction. The media press release must be issued within 60 days of breach discovery. The content of the media notification will be the same as the elements included in the notification to affected individuals.

Public Relations

While the incident is ongoing, the healthcare organization will continue to interact with the media and the community. Typically, one person serves as the spokesperson for the healthcare organization in front of the media. This helps ensure continuity and reliability of messaging and proper dissemination. Public relations personnel will create press releases to update the media and community continually. These updates may be placed in local newspapers, periodicals, and social media outlets. The public relations personnel may oversee the content that is placed on any web site created and dedicated to communicating data breach issues with affected individuals and other interested parties. In some cases, the lessons learned from the data breach can be shared with other healthcare organizations. Public relations personnel may contribute to this process to help develop the message for others to present or deliver it firsthand at professional organizations’ meetings, seminars, and other educational events.

Health Information Exchanges

In some circumstances, a data breach by a healthcare organization may result in the need to notify other external stakeholders. For instance, if a healthcare organization participates in a health information exchange (HIE), the healthcare organization may need to notify the exchange or other member institutions. HIEs exchange identifiable patient information for clinical care purposes. Because of the organizational relationships resulting from HIEs, healthcare organizations may incur new notification responsibilities.

Organizational Breach Notification Rules

Remember that under HIPAA, the risk of disclosure threshold is important to determine whether the data incident is a breach under the law (impermissible use). According to the US HHS, “a breach is, generally, an impermissible use or disclosure under the Privacy Rule that compromises the security or privacy of the protected health information.”21

Unless the healthcare organization can show through a risk of disclosure assessment that the PHI has a low probability of compromise or further disclosure, the disclosure is considered a data breach. The components of that type of risk assessment are as follows:

• The identifying elements that may constitute PHI and the potential elements that can be used to reidentify the information

• The person who handled the information through unauthorized disclosure or access

• A determination of whether the information was retained and viewed by the person

• An evaluation of mitigations resulting from exposure of the PHI

In the analysis, the organization may determine that notification actions are not required. In addition to the risk assessment determination, three disclosure scenarios would also serve as exceptions to the Breach Notification Rule in HIPAA:

• A person working for a covered entity or business associate inadvertently obtains or views PHI. Although the access is unauthorized, it is accidental and the person acted within the authority of the covered entity or business associate.

• An inadvertent disclosure occurred between two people authorized to access PHI in general, but not the information exchanged at that particular time. For example, a physician sends an e-mail to another physician with patient information. The sending physician misaddressed the e-mail. The receiving physician normally has authorization to view PHI, but not specifically for this patient or in this case. The information cannot be disclosed by the parties beyond that exchange.

• The unauthorized recipient would not have been able to read or maintain the PHI.

This definition describes organizational breach notification considerations based on US healthcare organizations. Of course, healthcare organizations around the globe have similar procedures and requirements. The following section will examine some examples.

International Breach Notification

By now, you should be convinced of the importance of notification of affected individuals, regulators, and the media to help preserve the privacy and security of PHI even after the data has been breached. After a data breach in the United States, the notification effort is intended to minimize damage and harm. This is true in other countries as well, where the external reporting requirements vary, but have the same general intention to minimize the harm to affected individuals. Here are some of the notification procedures:

• Canada According to PIPEDA, the external notification of the affected individuals and the privacy commissioner is mandatory for organizations subject to the law. In select provinces, such as Alberta and Ontario, rules are in place to make external notification mandatory as well.22

• People’s Republic of China China’s Cybersecurity Law (2017) requires that in the event of a suspected or actual data breach of personal information, an organization must mitigate the impacts and notify affected individuals. The government requires timely notification to the proper agency. However, the regulation and relevant specification guidance for implementation does not dictate an actual timeline for notification.

• Israel The enactment of the Privacy Protection Regulations (Data Security), 5777-2017, in 2018 interestingly does not require organizations to notify affected individuals unless the regulatory authority, called a Database Register, specifically determines notification is necessary. The determination is based on a categorization of databases that hold sensitive information as either a high or an intermediate level of security. If the data breach involves these categories of databases, it is designated as a serious security incident. The Database Register will also confer with the head of the Israel National Cyber Authority to decide whether notification is warranted because of the potential harm to the data subject.

Organizational Information Dissemination Policies and Standards

You should keep in mind several guidelines when you are participating in a data breach response and notification action. We have covered external communication, but internal communication is also important. A data breach may involve a relatively small portion of the organization in containment, investigation, remediation, and notification, but you can be certain that many more people in the organization are aware of the event. Unfortunately, these people do not always have the best view or the most accurate information. What they share with one another and outside the organization can detract from your official notification processes.

Here are some suggestions for creating internal communication to help keep staff members informed:

• Employees should receive practical and frequent communication. Rumors and gossip will happen relatively quickly. Start communication as soon as possible to counteract this.

• Honest communication that is authentic is best. Employees can be a terrific source of public relations advocates for the organization during this setback. Give them information they can share with friends, family, and the general public at home and online where possible.

• Stay connected with employees. Maintain regular communications, with accurate and official updates.

• Authorize managers at all levels to share approved communications. The sense of order that leaders can instill will be beneficial in an otherwise chaotic event.

• Allow for feedback from employees. In particular, employees who serve customers or patients can provide valuable information that helps improve notification expectations.

As the incident response team follows the established procedures and the external notifications are underway, internal communications done correctly will help the organization reduce the impact of a data breach. Brand and reputational impacts can also be lessened. Of course, even with internal communications, the information that you share should be appropriate for public disclosure—absent specific attack information or exposed vulnerabilities, for example. Focus on providing information to help employees answer the types of questions they may be asked.

In addition to details provided in public notifications, you may want to ensure that employees know the following:

• The steps the organization is taking to recover

• Assurance of continued business operations and safe patient care

• Actions affected individuals can take and who to contact

• A point of contact for employees to ask additional questions