CHAPTER 6

Risk Management and Risk Assessment

This chapter covers Domain 6, “Risk Management and Risk Assessment,” of the HCISPP certification. After you read and study this chapter, you should be able to:

• Understand risk management concepts, leading frameworks, and relevant processes

• Be able to assess risk management controls for effectiveness and efficiency

• Differentiate between quantitative and qualitative approaches to measuring risk

• Conduct risk management activities relevant to role and position in the organization

• Evaluate risk and support risk treatment decisions such as risk avoidance, mitigation, or transfer of residual risk in the organization

Healthcare information privacy and security has evolved from solely the pursuit of regulatory and standards compliance to risk reduction and information protection controls maturity. Compliance with laws and standards are still important, but our profession has advanced to be better aligned to clinical and business enablement. That requires a proficiency in risk management.

The concept of risk in healthcare organizations has several definitions depending on where you work. From a clinical perspective, risk is the measurement of the quality and safety of healthcare provided. Risks that put patients at harm are identified, and actions are taken to prevent or control the risks. Because we are concerned with information protection, risk is the measure of the potential harm caused by a purposeful or accidental event that negatively impacts the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of information assets. Information risk can also result in patient harm.

As you read this chapter, note that the use of the term “risk” will apply to information risk unless otherwise specifically mentioned. We cover the organized, systematic approach to managing risk and decision-making in information protection. There are several frameworks for doing this important work. Once you understand what your risks are, you can begin to decide what you want to do about it. We cover several approaches to managing risk. For example, organizations must decide whether to mitigate, accept, or transfer risk. We’ll also introduce a few other approaches to managing risk. In the end, your role is to measure the risk and communicate the alternatives to leadership with regard to how information protection integrates with business strategy, clinical practices, and third-party relationships.

Understand Enterprise Risk Management

Making decisions about managing information risk requires a systematic and organized approach. Otherwise, emotions or personal preferences can influence actions and may even increase the chances of an event happening or increase the extent of the impact. In a healthcare setting, we see this when clinical expediency is not balanced against risk of unauthorized information disclosure. There are many frameworks and a few different methodologies to use to assess and measure risk to help you make decisions. It is important to determine which fits best in your organization.

Before we introduce some of the leading risk frameworks, we need to define the following terms that are used in discussing frameworks and methodologies:

• Threat A source of potential information loss or damage relevant to your organization

• Vulnerability A weakness that may expose the organization unnecessarily to a threat

• Probability The likelihood that a threat can happen (increased based on vulnerability)

• Impact The extent of damages expected by a threat event happening

• Mitigation and controls Actions or processes put in place to either prevent (control) or lessen (mitigate) the impact of exploited threats

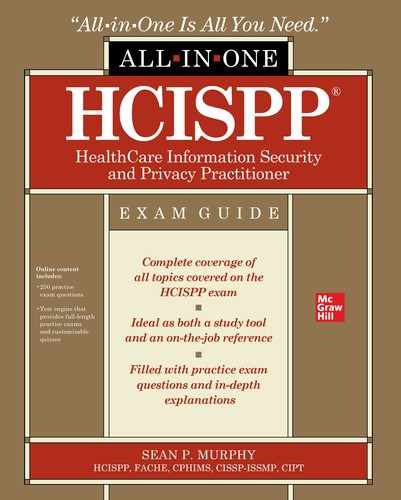

Figure 6-1 introduces the overall concepts underlying decision-making using risk measurement to choose between alternatives; this is a foundational concept behind any information risk management framework.

Figure 6-1 Simple risk-based decision tree

Measuring and Expressing Information Risk

We have to admit there is no perfect security strategy that eliminates all chances that an organization will experience an event. Some say it is not a matter of “if,” but “when.” Therefore, we focus on reducing the risk of adverse events as much as possible. To do that, we have to measure and express risk in an understandable format. Here are some risk equations you may be familiar with:

Risk = Likelihood × Impact

Risk = Threat × Vulnerability × Impact

Risk = Probability of Event × Measures of Consequences

These risk equations do not imply that risk is always measured in objective terms (numbers, percentages, data results, and so on). These measures relate to quantitative risk evaluations. Risk can also be expressed in subjective terms, such as a management value or priority measurement (low, medium, high, and so on). In healthcare, the impact of risk may be measured in monetary cost, reputation loss, and (most importantly) adverse patient events. As an illustration, an organization called Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) is a leading body of standards-setting organizations and experts from around the world. The organization uses a combination of simple measures to calculate risk. Based on subjective values (0–9, with 9 being the highest), assessments are made against threats and vulnerabilities to achieve an estimation of impact.1 These notional values are plotted on a chart to help you quickly identify the level of overall risk severity of the issue (Figure 6-2).

Figure 6-2 OWASP methodology for making risk-based decisions

Generally speaking, the common points made by almost all credible information risk management frameworks highlight these important steps:

1. Identify a person or people who are responsible for privacy and security issues.

2. Perform an information risk assessment (using a standards-based framework).

3. Have up-to-date policies that cover the proper use of sensitive information assets.

4. Charter a formal board or committee that oversees information risk management.

5. Communicate findings and remediation progress through that group to senior leadership (and the entire organization, as needed).

6. Manage third-party risk by assessing their proper use of sensitive information.

7. Maintain an active privacy and security awareness training program for employees.

8. Have an obvious incident reporting process for employees to follow.

Your organization can take several approaches to measure and evaluate risk. Many organizations may opt to combine approaches based on their mission, asset valuation, risk tolerance, or cost–benefit of conducting the analyses. We will discuss these approaches throughout this chapter. For now, here is a quick introduction to these approaches to demonstrate the types of outcomes you may have using risk evaluation and measurement tools and techniques:

• Quantitative approach This includes the use of objective data such as financial impacts, revenue losses, historical frequency and probabilities, and risk scores associated with vulnerability management. Because data can be difficult to obtain, this approach is sometimes used in conjunction with qualitative methods.

• Qualitative approach The components of the risk equations are valued at levels such as high, medium, and low. Subjective factors are used to measure and evaluate risk. This approach is particularly useful when the assessment must be made in a short period of time or the assessors are familiar with the subjects of the assessment (such as systems, processes, vendors, or applications).

• Hybrid or semi-options In some scenarios, a combination of both qualitative and quantitative approaches is used together. These approaches may be used sequentially. For example, a qualitative assessment begins the assessment, and a quantitative assessment follows to provide projected financial losses or magnitudes of severity of a threat. Alternatively, the approaches can be used in tandem with frequency, for example, being quantified while impact on intangible assets being assessed on a qualitative scale of high, medium, and low.

Identifying Information Assets

To begin an assessment and measurement process to evaluate risks to the organization, you must identify the information assets to be assessed. In this effort, you should be concerned with hardware and software for systems, devices, and appliances owned and operated within the organization. This will include identifying locations of systems and data storage for electronic protected health information (PHI). Both GDPR and HIPAA require organizations to have and maintain data inventories. With this information, you can initiate those healthcare information risk assessments that consider the threats or impacts to sensitive healthcare information.

The regulations do not prohibit manual approaches to establishing an inventory. Depending on organization size and complexity, you may be able to document asset inventory using project archives, interviews, and physical location by observation. More realistically, most organizations will need to use technology in the form of asset scanning tools to identify information assets. Numerous tools are available to perform different functions. A couple of examples of tools and scanning approaches you may consider for use are listed here:

• Passive scanning The approach typically scans network traffic for metadata contained in the packets that identify the assets and particular attributes of the assets. This information populates the inventory. Passive scanning does not adequately identify assets that do not communicate but are attached to the network. It can also miss some network and security appliances that operate only at the physical or data link layers.

• Active scanning On-demand scanning of the network can improve inventory of assets and information about the assets. This approach attempts to reach every asset on the network regardless of whether or not the asset is communicating. A downside to this approach is the risk of creating downtime as the network resources are taxed, or the individual assets possibly crashing as a result of the scan.

Asset Valuation Methods

Information asset valuation is a process that ascribes worth to data and technologies within the organization. Assets in a healthcare organization support important areas such as patient care activities, the operations of the organization, and research initiatives. The value of the assets will be specific to the organization as variables such as sensitivity, criticality, and strategic benefit will factor into the level of protection the assets require. Part of the measure of an asset’s value is the cost or other impacts to the organization if the asset is lost or unavailable for a period of time.

To begin an asset valuation exercise, we have to explore a couple of ways of gathering the data about the assets. When we discussed risk assessments earlier in this chapter, we featured two approaches, quantitative and qualitative. In conducting asset valuation, there is a similar differentiation in approaches—one is based on objective measures and the other is based in subjective analysis. Here are the two basic approaches:

Descriptive Approach

This subjective approach is obtained through structured and unstructured data collection tools such as interviews, surveys, checklists, and comment forms. The values may also come from focus group sessions with subject matter experts and stakeholders to establish baselines and develop indicators to monitor that value is gained. This type of valuation estimates the following:

• Intrinsic value This describes how accurate, comprehensive, beneficial, and exclusive the assets are.

• Business value This measures the relevancy of the assets and their usefulness for business purposes.

• Performance value This refers to the utility of the assets to drive key business or clinical indicators and initiatives.

Metric Approach

These measures are objective, or based in statistics, financial data, historical records, clinical outcomes, or economic rates. Calculations may come from external sources such as the costs to replace the assets, or from regulatory actions such as fines and penalties. Other sources of this data are asset logs, annual expenditures, return on investment calculations, or depreciation rates. Here are some of the categories of metric asset valuations:

• Cost value This is the cost to the organization resulting from loss of the asset and the associated expense of replacing it.

• Market value This is associated with the worth of the asset (such as a system, data, or technology) based on selling it or providing it as a service to another organization.

• Economic value This relates to the importance or direct influence the asset has on increasing revenue or reducing costs.

Using Valuation Approaches with Tangible and Intangible Assets

Assets can be categorized as tangible or intangible. You can use descriptive and metric approaches to measure each of these categorizations. Let’s take a closer look.

Measuring the Value of Tangible Assets Tangible assets are generally things you can touch. The word “tangible” means perceptible to touch. Assets such as office buildings, hardware, data centers, and some computer systems are often tangible assets.

To measure the value of these, a primary approach is a metric evaluation of original cost of the asset minus depreciation. Depreciation is a valuation of the reduction in value of an asset as it is used over time, presuming assets lose value even with normal use. Normally, an asset is valuable at least until the depreciation reaches a zero financial balance. Some assets exceed that timeframe, however, and can remain valuable for more years.

You can also determine tangible asset value by assessment of replacement costs. Those values can be obtained through market comparisons of competing suppliers and other sellers of similar products.

Measuring the Value of Intangible Assets These assets are property of the organization but are not physical assets, though they do have value and are often subject to regulatory requirements that necessitate investment in safeguards. Examples of intangible assets are goodwill, reputation, brand, licenses, patents, trademarks, and copyrights.

Healthcare organizations can generate a tremendous amount of intellectual property in clinical practices, research outcomes, and business models that have tremendous value. Most importantly to our learning in this area is that PHI is a source of intangible value to the organization in that it can be used to improve the clinical practices, reach research outcomes, and help develop new business models.

Measuring intangible asset values is difficult. There may not be a true original cost, depreciation estimates are not applicable, and replacement costs are not a possibility, particularly where the intangible asset is unique to the organization (such as patents, reputation, business process). Several approaches can be used to value intangible assets, including the following:

• Cost When applicable, the original cost of the asset can be compared against replacement cost. The drawback is that an intangible asset is usually worth much more than the cost required to develop or obtain it. Replacement costs generally do not provide a true representation of comparative value. This may foster risk assessment decisions to accept more risk than the high value of the asset would require.

• Capitalization of historical profits Intangible assets can lead to increased revenue and market share. Accounting for the costs of the intangible assets are changed from an expense to an asset and spread out over time associated with the returns on the investment. You can also refer to this approach simply as an income approach to valuation of the asset.

• Cost avoidance or savings Reputation or favorable brand recognition provides a good example of an intangible asset benefit that can be measured in the reduced risk of a data breach, a reduction in potential fines and penalties, and the prevention of lost revenue from abnormal patient churn to competing healthcare organizations.

• Market Some intangible assets are similar between organizations, such as copyrights or franchise licenses. If there is enough similarity, one company can estimate the value of its intangible asset based on the terms of a sale of a similar asset between two other companies.

Risk Components

The components of risk are the separate factors that can be measured to help predict the chance, cost, and magnitude an adverse event may have. It may be obvious, but risk is specific and unique to each organization. To sufficiently evaluate risk, apply adequate security controls, and treat the risks appropriately, all components need to be included. Think about a risk evaluation that includes an estimate of $4M due to a flood. The chance, however, of a flood in the location of the hospital is a once-every-100-years occurrence. Without the inclusion of frequency or likelihood, the impact of a $4M loss might be overestimated. Each component can and should be assessed individually as well as multiplied together to reach a measurement that can be trusted and useful. In these next sections, we will discuss important factors of information risk.

Exposure

Exposure is related to the concept of vulnerabilities in the context of information security. An exposure is a measure of the potential for occurrence as part of a vulnerability. You may see this term expressed as a predisposing condition in sources such as NIST SP 800-30 Rev. 1, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments. As an HCISPP, you will understand that the environment you work in involves the use of PHI with a high degree of information sharing. This is an example of a predisposing condition or an exposure that will help you risk assess various vulnerabilities. Other sources view exposure, in part, as the existence of misconfigured systems or defects in software applications that can increase likelihood and impact of a vulnerability that an attacker exploits.

Likelihood

The probability, or likelihood, that a vulnerability will be exploited is an important component of the risk equation. We can evaluate the likelihood from the perspective of the attacker or adversary. This view includes consideration of adversary attributes, including capabilities, skills, persistence, and objectives that increase or decrease the chance the attacker could exploit a vulnerability. Another angle to use to measure likelihood is through historical data. For example, the likelihood that natural disasters could occur can be predicted based on past occurrence of the events. You could add a measure such as service level agreement (SLA) compliance with patch management to a likelihood measure. If the organization typically does not meet SLA requirements, the likelihood of vulnerabilities being exploited increases without any increase in adversary attributes.

Impact

Risk decisions cannot be made without a realistic estimation of the effects or consequences of a security event. Overestimation can lead to overly restrictive and costly actions to avoid or minimize the outcome of a security risk. Underestimation can have the opposite effect, as the organization may not prepare adequately. Think of impacts such as having to limit healthcare operations to emergency care only because computing capabilities and access to data are blocked by a successful ransomware attack. Natural disasters, such as hurricanes and tornados, can render information technology unavailable and data access impossible. During such events, the unavailability of data to healthcare providers poses a significant negative impact on patient care and patient safety.

Impacts are measured by the quantitative and qualitative harm they bring to the organization. As a reminder, quantitative measures, such as financial losses, are objective. Qualitative impacts could be loss of reputation, a subjective assessment. Keep in mind that assessing impact is unique to each organization. An impact to one organization may not be equally harmful to another. Decision-makers will differ in accepting or rejecting projections of the harm the organization assets will sustain.

Threat

Threats are dangerous events or circumstances that are caused by a source attempting to exploit a security vulnerability. A threat exploits a vulnerability to cause impact. Cyber-attackers, malicious insiders, and untrained employees can all pose information security threats. Natural disasters are also potential threats to the protection of information. For example, firewall security logs (or, more likely, the dashboard reporting of the firewall tool of your choice) identify significant traffic coming from geographic locations that are known cyber-espionage havens. Those IP addresses may belong to nation-state actors who are threats to your organization. In the same way, because untrained employees are more likely to click links in phishing e-mails, they can serve as threats to the security of the organization.

Vulnerability

If you have worked in IT and security for any amount of time, you’ve most likely heard about vulnerabilities. We will formalize that understanding as a component of risk. In simple terms, a vulnerability is a weak point in software applications or program codes that can be exploited by a threat. A vulnerability can also be an area of susceptibility for the organization, such as a lack of tested disaster recovery plans. In the event of a natural disaster, the vulnerability is exploited—not by an attacker, but by the natural threat event happening.

Evaluating Risk Components

We have introduced equations to determine risk earlier in this chapter. We have defined each of the components that make up risk. When you pull it all together, you can see how risk is a measure, quantitative or qualitative, of how likely a threat is to expose a vulnerability in an organization, and to what extent a successful event will result in negative consequences. You should be familiar with a couple of other topics related to risk as well.

First, information risk is an independent subcategory of overall organizational risk, also known as enterprise risk. However, in the subcategories of enterprise risk, information security is often a consideration. For example, in operational risk, revenue projections may be at risk for a variety of factors, one of which could be information security events. We have discussed earlier how information security events can impact the organization’s reputation. That said, information security events are one component of the overall reputational risk factors (such as a malpractice lawsuit).

Another topic within information risk, a strategic view of information of risk includes a process to assign prioritization of assessed risks. Budgets, time, and staffing are limited. Along with treatment of risks, which we discuss a little later in this chapter, information risks that the organization decides to mitigate must be prioritized. Related to prioritization, some risks are related to others, or a mitigation of one is also a mitigation of the other. This is particularly true when individual risks are low priority by themselves, but when several risks are considered together, the cumulative risk elevates the priority. Aggregation of specific risks can improve cost effectiveness in reducing risk—for example, reducing risks in vulnerable software, network monitoring gaps, and inconsistent service account management through investment and corrections to the IT asset management system.

Employing Security Controls

To protect information, the organization must employ security controls, such as standards or technologies that are generally accepted as effective at reducing information risk. Cost is a concern in that a security control is not effective if it costs more to implement and maintain than the value of information asset it protects. Controls outlined in HIPAA, NIST guidance, and ISO publications meet the requirement for properly implementing security controls.

The nature or function of these controls is organized into the following categories:

• Administrative Also termed management, these controls are focused on operation of an information security program with governance implementing and enforcing required policies and procedures.

• Technical Also called logical controls, these controls are technologies including hardware, software, and other IT solutions used to ensure information protection capabilities.

• Physical These controls are barriers, deterrents, and impediments that prevent or alert against unauthorized entry or access to property and information assets.

• Operational Sometimes referred to as procedural security, these controls are characterized by people conducting some routine, practice, or technique. Examples of operational controls are incident response plans, clean desk policies, and disaster recovery plans.

Another way of categorizing the security controls is according to the security phase the control is meant to impact. To illustrate, here is a list of security control phases and their benefit:

• Direct Describe what the expected user actions are.

• Deter Discourage attacks and violations.

• Prevent Attempt to avoid the incident.

• Detect Identify the event as it happens.

• Correct Rectify the situation as quickly as possible.

• Recover Restore operations safely.

• Compensate Provide alternative or complementary controls.

You will notice that leading security control frameworks have thousands of security controls. When you have knowledge of the sources, categories, and benefits of security controls, you have a foundation for making decisions about which of the thousands of security controls are applicable to your organization. Trying to implement all of them will fail, and some controls are not applicable to every organization based on mission, size, and risk tolerance, to name a few considerations. At this point, you have the context for how to shape, or incorporate, information safeguards in an organization with these overarching concepts and taxonomies. Figure 6-3 depicts these groupings of security controls as well as their overlap with regard to integrating and serving multiple control functions.

Figure 6-3 Overlap of security control categories and functions

Compensating Controls

In healthcare, it is often the case that prescribed controls and even alternative controls are not feasible to implement. One of the most prevalent examples of this scenario occurs within medical device management. Some medical devices are imperative in diagnosing and treating patients, yet these devices may not adhere to some of your information security requirements. In some cases, the device manufacturer has evaluated and approved only one version of an operating system that is considered obsolete for regular office automation. Additionally, the same medical device may not be able to accept software vulnerability patches because they negatively impact the device. In this case, the healthcare organization cannot knowingly allow the medical device to operate on the local area network. Disconnecting the device or upgrading it without manufacturer approval is also not an option for the healthcare organization. This example demonstrated the need for compensating controls.

A compensating control is a safeguard or a combination of approaches used in place of a prescribed security control. Compensating controls are valid deviations. They are neither shortcuts to compliance nor approaches used to help avoid implementing a control. Before implementing a compensating control, you should conduct a risk analysis to document the legitimate need for a deviation (legitimate technological or documented business constraint). In the medical device scenario, the alternative controls of private network segmentation and manual patch management would be legitimate deviations. In addition to these examples for medical devices, other examples of compensating controls are backup generators, hot sites for continuing IT operations, and sensitive information server isolation. The intent of the original, prescribed control is met, but the bona fide considerations are addressed to balance both information protection and patient care.

In sum, a valid compensating control offers several distinct elements:

• It satisfies the original requirement and is as thorough as the prescribed control.

• It provides a similar level of defense as the original requirement.

• It is acceptable if the compensating control is actually more stringent than the prescribed control.

• If any additional risk is present because of the compensating control, the compensating control must meet cost–benefit or risk–reward criteria.

• If the compensating control is temporary, it should be removed when no longer required.

No one should view compensating controls as a shortcut to compliance. In healthcare, nevertheless, it is common to meet resistance to implementing compensating controls. Some clinicians and healthcare providers will argue that a prescribed information asset control “negatively impacts patient care,” so it should not be implemented. Although negative impact is always a primary concern in the cost–benefit analysis of any information protection decision, that does not excuse a reliance on overly relaxed controls or standards. The goal of having a healthcare-specific information privacy and security curriculum is to learn to integrate the valid concerns of caregivers with the imperatives of providing healthcare information privacy and security. This balancing act makes understanding the proper use of compensating controls a key skill to master.

Security Categorization

To determine what controls should or should not be implemented, the organization must shape its approach around the types of information it collects and uses. According to FIST PUB 199, Federal Information Processing Standards: Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems, security categorization is a process of evaluating the information against confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA).2 You can use a simple low, medium, or high valuation reflecting the importance of each component to determine a subjective score. For example, if you believe availability is the most important component of CIA for PHI, you might use an equation like this:

Security categorization = Confidentiality (low) + Integrity (low) + Availability (high)

This valuation may lead an organization to provide controls that ensure availability, such as investing in a generator and providing continuous power to information systems. In this case, investment in confidentiality and integrity controls may be secondary and more conservative. Figure 6-4 illustrates a simple process to provide information security categorization. To determine the security categorization in healthcare, you can use the equation for PHI and for personally identifiable information (PII) after you identify where this data is and how it moves through the organization. At that point, the information is categorized and you can determine the level of protection that is required.

Figure 6-4 Categorizing information for safeguarding

Now that you have a basic understanding of how information security levels are categorized, it’s important to acknowledge the complexity of the categorization process. As noted in NIST SP 800-60 Vol. 1 Rev. 1, Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories, a certain system may actually use various types of data with multiple levels of impact to the organization if the data is breached.3 The electronic health record (EHR), for instance, includes PHI, insurance data, and contact information. Some occupational health services will even include employment records in PHI. The categorization formula remains the same: using the categories of confidentiality, integrity, and availability, the organization must assess each type of information in the same way, albeit independently for high, medium, and low values, depending on their criticality in each of these three areas. When it comes to an organization’s EHR system, this is a team effort. Representatives from clinical service departments, finance, IT, and clinical engineering (medical devices) should be included to ensure the best outcome. Categorizing information security is a means of taking inventory for sensitive data and facilitates other risk management activities.

Assessing Residual Risk

A residual risk is a portion of a risk that remains after a risk assessment has been conducted and mitigated to the best extent possible. It is important to note that some residual risk may be accepted, while other residual risk may be transferred or avoided. To help you understand the response to risk an organization will take, a key factor to remember is the residual risk tolerance. In short, this is the level of comfort an organization has for the likelihood and potential impact of a threat that exploits a vulnerability. Closely related to risk tolerance is the concept of risk appetite. You should understand the slight differences between the two because each has usefulness in managing information risks:

• Risk tolerance The degree of risk or uncertainty that is acceptable to an organization, usually defined at the operational or system level.4

• Risk appetite The types and amount of risk, on a broad level, an organization is willing to accept in its pursuit of value. It is generally defined at the organizational level.

Among the considerations are how the response to the risk fits with the organizational mission and objectives. A point we make often in this book is that the healthcare industry is different from other industries with information privacy and security concerns. Residual risk tolerance is a prime example of where this is true. For instance, in managing networked computing equipment, a proper risk management approach is to load software, particularly antivirus management software, on devices as part of a standard configuration. With this software, vulnerability patches can be pushed out remotely and automatically by system administrators. Computing devices stay at protected levels, keeping risk of virus infiltration low at a reasonable cost to the organization. However, with medical devices such as digital X-ray systems and smart infusion pumps also connected to the network, it’s important that any additional software not be loaded on the machines. Each device manufacturer must test and approve software additions, updates, and deletions to these special computing devices, which typically cannot be included in the automated patch management process. This does not mean they cannot be secured, however. There must be an alternative process available that reflects the concept of residual risk tolerance, because the organization accepts that one size does not fit all. Perhaps the medical devices can be segmented into a private networking scheme or enclave. Maybe software patches can be loaded manually only. This may inflate cost and level of effort, but it is an effort required within a healthcare-savvy information protection program. An organization may have to accept more risk, or a higher risk tolerance, for medical devices as a trade-off for the patient care benefits provided by the technology.

Based on the residual risk tolerance, you can take several approaches to address the risks found in the risk assessment:5

• Avoid The least tolerance for these categories of risk causes the organization to try to sidestep the risk completely. Alternatives to the original process or technology must be found and implemented. As a simple example, imagine a healthcare organization that assesses the risk of a legacy IT system as high or above the established risk tolerance level. To avoid the risk, the healthcare organization would upgrade or replace the legacy system to address the risk.

• Transfer Two approaches to this category are prevalent. First, the organization shifts the risk to a third party. This is usually as a function of a contractual document or language in an agreement that holds harmless the healthcare organization from any exploitation of a risk. This risk transfer process is termed indemnification. The second risk transfer approach is to buy an insurance policy to cover the financial costs relative to the impact of the breach. In US healthcare organizations, cybersecurity insurance is used to help defray the financial burden of conducting investigations, notifying patients, and doing things such as providing credit monitoring patient credit histories. In fact, depending on the type of cybersecurity insurance, the coverage can include paying fines and penalties. Of course, cybersecurity insurance cannot reimburse an organization for costs related to lost business, damaged reputation, and time wasted on breach remediation. All of this must factor into the approach to addressing risk.

• Mitigate If you cannot avoid the action that increases risk, you may choose to mitigate the chances of negative impact. Implementing administrative, physical, and technical controls such as those discussed in in NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 4, Security and Privacy Controls in Federal Information Systems and Organization, enables you to use information privacy and security to mitigate risk. There is no way to eliminate risk completely through the use of security controls. Mitigations will always lead to a level of residual risk that the organization will have to accept, albeit a low level well under risk tolerance thresholds.

• Accept There are situations in which you can accept risk. After considering avoidance, transfer, and mitigation options, you must simply accept some risks. This may even happen when the residual risk exceeds the risk tolerance levels, though these cases should be rare. Nevertheless, when the benefit of accepting the risk outweighs the potential for harm, risk can be accepted. When an organization chooses to accept risk, it still must document this measured decision and continue to assess the risk as options change or risk increases.

Accepting Risk

A risk acceptance decision is a conscious choice to expose the organization to negative impacts based on a comparison of the risk assessment with the benefits that are expected. Unless a risk is avoided, you will always have some level of risk acceptance after transfer and mitigation efforts are implemented. Risk acceptance must be based on informed decision-making through a process to identify the risk and assess the options. When all of these factors have been addressed and it has been determined that the risk is acceptable, assignment of risk ownership and documentation is needed.

Risk is dynamic, as we have noted. Over time, risks can increase or decrease. Ownership of the risk is a process of assigning the responsibility to maintain any conditions that permitted acceptance of the risk. For example, consider a limited use of videoconference capabilities as an acceptable information security risk when they are used only for a small pilot group involving no transfer of PHI. Ownership of this risk may be assigned to the marketing team that wanted to use the technology to conduct focus groups for a new clinical service in development. The team would be primarily responsible for acceptable use of the technology. If the team expanded its use of the collaboration tool, as the risk owner, it would be responsible for initiating a new assessment. Not reviewing the conditions and increasing exposure and risk would be a violation of security controls.

Understand Information Risk Management Framework

A risk management framework is effective only if it drives organizational decisions and behavior. Running decisions through the framework to categorize information assets and identifying levels of risk are the first steps. This data must progress to the next steps. The organization needs to identify and prioritize the actions it will take to address the risk it has identified. An organization that stops at this point of identifying risk is probably going to be considered negligent by regulators. In the event of data loss and one or more of the identified risks being exploited when the organization failed to implement a response to the risk, the organization can expect increased fines and penalties.

At a high level, NIST builds a risk management framework around the activities of a risk management program. The best use of the information in this chapter about risk management frameworks is to recognize how each framework approaches one of the most foundational concepts of healthcare information privacy and security: information risk. You will see that no matter what tool you desire to use, the objective is to measure risk by identifying vulnerabilities, assigning a likelihood of occurrence, and assigning a value of the impact to your organization. From there, you can begin to design and implement controls to mitigate the likelihood of risk, minimize the impacts, and thereby manage risk.

NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF)

One of the most commonly cited risk management sources is the risk management process defined in NIST SP 800-39, Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View. However, that does not preclude the use of other credible sources. The choices depend on your organization’s mission, scope, and tolerance for information risk. NIST approaches risk management as a holistic process that must take the entire organization into account. At a high level, NIST builds a risk management framework around the activities of a risk management program.6 Over the years, the risk management framework that NIST has developed has evolved from a concept of ideas that should work for all organizations to a well-defined framework that is malleable to be used in most sectors. Following are high-level steps identified by the NIST RMF:

• Framing risk What is the organization’s risk tolerance, and how does it make decisions about risk?

• Assessing risk What are the values for the risk equation, and what are the results?

• Responding to risk Based on the organization’s risk tolerance, what alternatives will be chosen to address risk?

• Monitoring risk How will the organization oversee changes and respond to any impacts of risk mitigation activities? This is a continuous process.

Keep in mind that these four steps are interconnected by as much information and communication flow as possible. The process is continuous, so the information and communication flow must contain feedback and improvement concerns.

A second source you should be familiar with is NIST SP 800-37 Rev. 2, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy. While the guide is intended for use in US federal agencies, the concept of a risk management framework is important to commercial businesses, including healthcare organizations. The NIST RMF is a disciplined, organized, and repeatable process for achieving information protection of information systems. When comparing the information in NIST SP 800-37 Rev. 2 with a similar framework in NIST SP 800-39, Managing Information Security Risk, for example, you can see overlap. Both are lifecycle concepts with continuous monitoring and improvement as a central concept. NIST SP 800-37 Rev. 2 specifies as one of its stated purposed that senior leaders must be provided “the necessary information to make cost-effective, risk-based decisions with regard to the organizational information systems supporting their core missions and business functions.”7

The two models presented in SP 800-37 Rev. 2 and SP 800-39 are not redundant and can work in tandem. The more detailed nature of the RMF enables flexibility to adapt the framework to industry-specific standards and guidelines. In sum, the RMF provides organizations with the flexibility needed to apply the right security controls to the right information systems at the right time to manage risk adequately. In the United States, many of the HIPAA Security Rule standards and implementation specifications correspond to the steps of the NIST RMF.8 Approaching risk management using these NIST frameworks will help any healthcare organization comply with its risk management strategy.

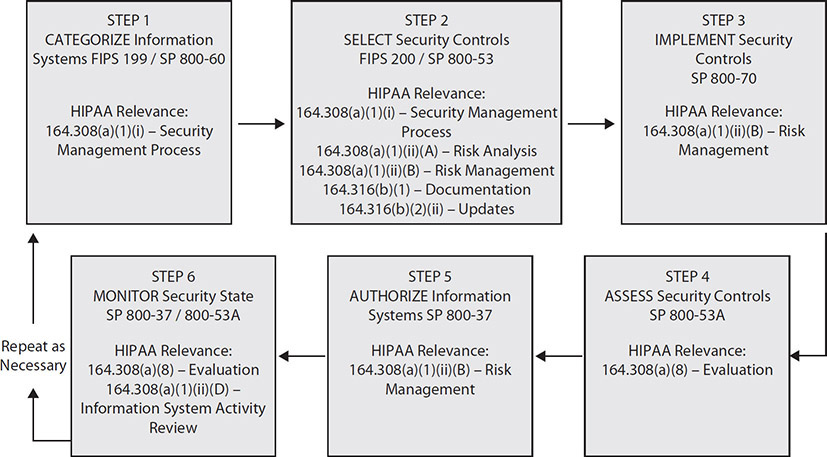

Within the NIST RMF are specific steps organizations should take to manage their risk, not only at system and application levels, but also organizational level risks associated with the collective risk from systems and applications. In NIST SP 800-37 Rev. 2, the RMF consists of six steps, as displayed in Figure 6-5. Each step has multiple tasks that should be completed in the order outlined to meet the requirements of a fully effective risk management process. Organizations historically did not fully implement all aspects of the framework, resulting in unidentified or unmitigated risks caused data loss or exposure. Effective implementation is not always easy, inexpensive, or even understood by all functional areas in an organization. The organization must have a governance structure that supports this effort.

Figure 6-5 NIST risk management framework steps and tasks

International Organization for Standardization

We discussed the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) earlier in Chapter 4 in the context of its role in developing governance guidelines. Here, it is discussed in the context of how it approaches information risk management. For those who work outside of the United States or in US healthcare organizations that do business internationally, having an awareness of ISO standards is important. Since 1947, when the ISO was created, the organization has published 19,500 standards for business and technology industries.

From an information risk management perspective, two leading standards apply. The first, ISO/IEC 27001, Information security management, presents best-practice information about security management principles, a framework, and a process for managing risk. These guidelines are applicable to any organization or mission regardless of its size, activity, or sector. This standard approaches risk by focusing improvement of objectives by identifying opportunities and threats. From there, the organization can allocate resources to deal with the risk effectively. If you use ISO/IEC 27001 or any of the ISO/IEC 27000 family of standards, you will learn to define risk not as a chance or probability of loss, but by means of the effect uncertainty has on your objectives.

The ISO 27000 family of standards also introduces the final step in the risk management process: risk treatment. Adapting risk treatment actions from this guidance, you will realize that you have some familiar risk mitigation options for your organization to address risk:

• Avoid Do not do the action causing the risk.

• Accept The probable cost of the occurrence is less than the value of the objective.

• Retain Provided informed consent and potential loss are minimal, you can budget for risk.

• Remove Eliminate the vulnerability or source of risk.

• Change Adjust the likelihood of occurrence or the consequences (mitigation).

• Share Transfer the cost through insurance, contracting, or other third-party agreement (outsource).

The second major ISO source for information risk management is ISO/IEC 27005, Information technology – Security techniques – Information security risk management. Every source of risk management guidance should have risk assessment at the core of the processes. However, keep in mind that risk assessment is only a piece of the entire risk management process. ISO/IEC 27005 focuses on risk in information systems and expands on effectively and efficiently conducting just the risk assessment. Starting with selecting the proper risk assessment techniques, this standard guides the assessor through the proper steps.

You should be familiar the following information regarding the risk assessment steps according to ISO:

1. Define the risk method you will use. There is no specific template to follow, but you will need to make sure you have security benchmarks, risk measurement values, risk tolerance levels, and what the ISO/IEC 27001 terms a “scenario-based” or “asset-based” risk assessment.

2. Inventory your information assets. This is particularly important for an asset-based assessment. Document information assets including IT hardware, software, intellectual property, and medical devices.

3. Identify threats and vulnerabilities. As with other frameworks for risk assessment, you need to understand what manmade and natural threats are possible. Vulnerabilities that can result in those threats being realized must be cataloged too.

4. Estimate the likelihood and impact amounts. This is another common step among frameworks. It is important to estimate the potential for a threat to happen and the resulting consequences.

5. Reduce risk through mitigation to acceptable residual risk levels. ISO/IEC 27001 includes a variation of the risk handling taxonomy. To avoid risk is to terminate it. Applying security controls is to treat the risk, compared to mitigating it. ISO/IEC 27001 also uses the term “transfer” to describe shifting risk to a third party. The action to accept risk is called “tolerate.”

6. Assemble reports to communicate risks. Two examples of reports that are used for compliance with ISO/IEC 27001 as well as certification are a Statement of Applicability (SoA) and a Risk Treatment Plan (RTP).

7. Review, monitor, and audit. A continuous risk assessment process with revisions to improve the processes is required to stay current with ever-changing elements that determine risks.

Going back to the risk management process focusing on objectives, risk assessment helps risk managers recognize the risks that could affect the achievement of objectives as well as the adequacy of the controls already in place. Keep in mind that like all good processes, the system needs constant communication to and from stakeholders, and it is cyclical. Once the last step of the risk management process, risk treatment, is completed, it is time to begin again with establishing the baselines. In all of the better risk management processes, always start with a baseline assessment or an inventory. As you can see, the ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 27005 standards are no different.

A component of ISO guidance that differs from other frameworks is that certification is available by qualified assessors. Organizations can voluntarily choose to achieve ISO/IEC 27001 certification to demonstrate compliance and competency. It is possible that certification helps to assure customers of trustworthiness of the organization to protect information.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), an operating division of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), combines the oversight of the Medicare program, the federal portion of the Medicaid program and State Children’s Health Insurance Program, the Health Insurance Marketplace, and related quality assurance activities. This represents the healthcare coverage for more than 100 million people in the United States.9

CMS Risk Management

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has developed its own risk management framework, which closely follows the NIST framework.10 Because CMS is specifically a healthcare-sector support agency, it has worked to ensure that compliance with HIPAA and other legislative requirements applicable to healthcare are addressed in its framework. Much like NIST, the framework follows these steps:

1. Categorize the system based on the information (data) types in use.

2. Select security controls.

3. Implement security controls.

4. Assess security controls.

5. Authorize the information system.

6. Monitor security controls.

Understand Risk Management Process

Whatever process you determine fits your organization and satisfies any regulatory requirements, your risk management process must accomplish a full assessment of risks and minimization of uncertainty. In healthcare information privacy and security, we want to use a risk management process that integrates security, privacy, and enterprise risk. Outcomes will include proper decisions for control choices and risk treatment. Starting with an authoritative source such as NIST SP 800-30 Rev. 1, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments, the process for managing risk consists of four phases:12

• Framing The strategy for how risk decisions will be made in an organization. The process is related to the organization’s perceived tolerance for risk.

• Assessing The determining of risk based on a measure of the threats, vulnerabilities, likelihoods, and impacts the organization faces.

• Responding The generation and implementation of options to address assessed risks based on how you decide to frame risk decisions.

• Monitoring The continuous observance of the effectiveness of risk management activities in place and adaptation to changes in the environment. This phase includes ensuring that risk management approaches are aligned with industry standards and regulatory requirements.

These four phases are guided by continual information flow throughout the process. Each phase is connected and integrated. In fact, information is shared to inform each phase. For example, in the framing stage, the board of directors may indicate a low tolerance for financial and regulatory risks. That information is very important to inform how the organization may respond to risks; it may opt for more stringent controls above regulatory requirements. Another example, given the same risk tolerance levels, auditing of security controls with findings of ineffective operations may need elevation to the board as significant. In organizations with a higher tolerance for risk, those same findings may not receive the same sense of urgency.

When structuring a decision that measures risk around these components, you can use a risk management framework, discussed earlier in this chapter, to weigh cost against benefit or risk versus reward. In all cases, you can ensure that you are implementing controls that are relevant and cost-effective to the assets you are trying to protect.

Risk management processes are the combination of three key activities. Those distinct activities are assessment of risk, management or treatment of risk, and monitoring of risk. In healthcare, information risk management is so important because in addition to financial and operational risks, healthcare risk management must include patient care and patient safety risks. The process must include stakeholders from departments throughout the organization, not just information security personnel. The results must be shared throughout the organization as well to reduce risk, improve patient care, and enhance business processes. A good definition of the risk management process includes prioritization of risk treatment options.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Approaches

You have been introduced to approaches to measuring and expressing information risk in this chapter. In the section “Measuring and Expressing Information Risk,” we differentiated between quantitative and qualitative approaches. Here we examine more specific uses of the two approaches.

Starting with a quantitative approach, you remember that objective data such as financial measures or historical trends are the goal. Here are some common financial variables to consider:

• Exposure factor (EF) Expressed as a percentage between 0 and 100 percent. It estimates the value of an asset that is lost due to a risk occurrence.

• Single loss expectancy (SLE) The asset value multiplied by the exposure factor as a one-time occurrence.

• Annualized rate of occurrence (ARO) The likely occurrence per year of an incident. If the threat may occur once every five years, the ARO is 0.2. If the threat happens five times in one year, the ARO is, of course, 5.

• Annualized loss expectancy (ALE) This equation is derived from the others. It is the SLE multiplied by the ARO.

Let’s take a look at a fictitious example. If a ransomware attack risk is being calculated, the variables could include a database asset that is valued by the organization at $100,000. In a ransomware attack, we can imagine a 50 percent loss of the asset due to incomplete backups for this scenario. In this organization, the estimate is one successful ransomware attack in any five-year period. Therefore, we can provide a quantitative risk assessment that indicates the following:

• Exposure factor (EF): = 50%

• Single loss expectancy (SLE): $100,000 × 0.50 = $50,000

• Annualized rate of occurrence (ARO): = 0.20

• Annualized loss expectancy (ALE): $50,000 × 0.20 = $10,000

Now we can examine an approach using qualitative analysis. This example includes information from the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS). You may be familiar with CVSS, the open framework for vulnerability ratings that is used by the National Vulnerability Database (NVD). The NVD is a joint effort between NIST and the US Department of Homeland Security. The CVSS consists of three metric groups that you can use to make a qualitative assessment of a specific risk factor:13

• Base metric Components that are able to be exploited and impacted

• Temporal metric Vulnerability attributes that may change over time

• Environmental metric Unique vulnerabilities relevant to a single organization

We can use another fictitious scenario to construct a qualitative assessment and score it with the CVSS. We will illustrate the base metric here. In practice, the base metric score is often sufficient to make our point and for you to make a threat assessment that can be used with other variables to come to a good risk decision. The base metric is fundamental and unchanging over time to determine severity. If you desire, you can expand the use of CVSS to examine mitigations using a second component, the temporal metric formula. The third component, the environmental metric, can also be added to assess the pervasiveness of a vulnerability throughout the organization. For purposes of illustrating the use of a validated qualitative risk management processes, we will spare you the increased complexity of the CVSS calculator.

Take note that this CVSS example shows that qualitative or subjective values can be associated with numerical values to provide a semi-objective measure rooted in expert opinion or observations; this helps to address perceptions of qualitative measures as less reliable or less valuable in decision-making as quantitative measures. As you remember, there are times when quantitative values are best to use and other times when qualitative measures are more appropriate. Sometimes, a combination of both could be the best option.

In our next scenario, an organized group of cybercriminals constructs a multiple-source botnet attack that can overload and organization’s public web pages and results in an embarrassing and costly distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack. Figure 6-6 depicts the choices and selections that are available in the CVSS calculator for the basic metric.

Figure 6-6 CVSS calculator example of assessment score

Presuming that selections made in the basic metric area could be based on opinion or subjective estimation, you may differ with the responses indicated in the figure. As noted in the figure, all of the base metric components are required to achieve a base score. Here’s an explanation of the base score metrics:

Exploitability Metrics

• Attack vector (AV) = Network (AV:N)

A DDoS attack is remotely conducted against a network, although no network access is required.

• Attack complexity (AC) = Low (AC:L)

The attacker does not need special access or tools. Repeated attacks can be expected to also be successful.

• Privileges required (PR) = None (PR:N)

The attack is initiated by an unauthorized actor.

• User interaction (UI) = None (UI:R)

In our scenario, no user needs to be involved for a successful attack.

• Scope (S) = Unchanged (S:U)

The attack is concentrated within a single organization.

Impact Metrics

• Confidentiality impact (C) = None (C:N)

There is a low risk of loss of confidentiality due to a disruptive DDoS attack.

• Integrity impact (I) = None (I:N)

No data or system integrity is expected.

• Availability impact (A) = High (A:H)

A successful denial of service would be highly likely to cause complete loss of data and system availability over a period of time.

Included in the figure is a set of graphs of each base metric and their respective scale (0–10). Additionally, within the calculator, each component becomes a vector. In this case, the vector is AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:N/I:N/A:H. From the vector, the CVSS calculator is able to execute an algorithm to result in a total CVSS score of 7.5 based on our scenario and subjective assessment of each component of the base metric elements. To interpret the significance and risk level of a score of 7.5, you would consult with the CVSS standards user guide that is available.14

Intent

Whether you choose to implement a risk management process that is entirely quantitative or totally qualitative in focus or a combination, the intent of the process is the same. You can determine that one assessment framework works better for your organization over another. However, the objective is constant. A risk management process is meant to minimize risks to the organization by understanding threats, vulnerabilities, likelihoods, and impacts and reducing or mitigating potential negative outcomes. Keep in mind that the three principle reasons information risk management is so important to you as an HCISPP is that the process is your central competency to help your organization:

• Stay current with regulatory and legal requirements, as risk management is a necessity.

• Apply and enforce security and privacy controls to ensure confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information.

• Provide relevant and essential input to influence and support risk management decisions.

Information Lifecycle and Continuous Monitoring

Risk management has to be integrated into the entire lifecycle of information technology and data assets. In general, information goes through several phases, and in each phase there are privacy and security requirements. Assessing and managing risk must occur when information is created or received, shared, handled, stored, and disposed of when it is no longer needed. For example, in the last chapter, we discussed security categorization, which is a process that should occur no later than in the creation or receipt phase of the information lifecycle. Destruction of a computer hard drive with PHI stored on it would occur in the disposal phase, for example.

In each phase, risk management actions are required of the information owner. As a security professional, you probably are not the information owner, but you will have a significant role in assessing risk levels, informing risk decisions, and assuring that risk treatment is accomplished by the information owner. Within a healthcare organization, the chief executive officer (CEO) or authorized delegates are designated formal information ownership responsibility. That may seem excessive, but the formal assigning is in reference to international standards and regulations such as the GDPR that define information owners and are explicit on accountability at the most senior levels of the organization. In the United States, you may find information ownership assigned at different levels in the organization. However, this does not devalue the roles and the impact they have on risk management during the information lifecycle. Information owners are expected to do the following:

• Provide for the privacy and security of the information under their control.

• Understand the value of the information and replacement costs.

• Estimate the impact of information loss or tampering.

• Maintain appropriate safeguards to protect the information.

• Report incidents in a timely manner upon occurrence.

• Allow access on a strict business or clinical “need to know” basis.

• Determine when information is no longer needed and assist in secure disposal.

You may have heard that risk assessments and risk management planning are annual requirements. That would be incorrect. HIPAA, for example, requires risk assessments conducted “continuously to identify when updates are needed.”15 In some organizations, a complete assessment could be done annually or biannually. In others, the timing may be more often based on how things change in the environment with added policies, new systems, and interconnections, particularly with external entities. In all cases, expect risk management processes to be ongoing and not single events with specific start and stop dates.

Tools, Resources, and Techniques

The use of tools, resources, and techniques to conduct and document risk assessments and risk treatment decisions helps in a variety of ways. You may have heard the expression, “Not documented equals not done.” Auditors and regulators across the globe will require proof of compliance for risk management activities. Admittedly, the existence of a reasonably simple set of file folders with up-to-date risk assessments, policies, and corrective actions plans would probably suffice. There are, however, several tools available that can assist. Based on complex regulatory requirements, these tools also serve to guide completeness in terms of what auditors and regulators may inspect.

The use of a tool can make assessing and managing risk easier. You must keep in mind that tools for risk management are only beneficial if the underlying methodology is sound. For example, US healthcare organizations would prefer tools that follow a process or methodology such as NIST SP 800-30 Rev. 1, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments, depicted in Figure 6-7, which includes these steps:16

Figure 6-7 NIST risk assessment steps

1. Prepare for the assessment. Be thoughtful and comprehensive in determining the requirements, approaches, scope, assumptions, constraints, and models. During this phase, you will identify and categorize threats, likelihood, and impact information that will support the assessment.

2. Conduct the assessment. As shown in Figure 6-7, this step comprises several key tasks. These tasks are at the heart of determining and evaluating the components that constitute the risk equation (for example, risk = likelihood × impact):

a. Identify threat sources and events. Describe the hazards or dangers, including capability, intent, and targeting characteristics, for adversarial threats and a range of effects for nonadversarial threats.

b. Identify vulnerabilities and predisposing conditions. Evaluate the weaknesses and exposures that influence likelihood that a negative event will happen.

c. Determine the likelihood of occurrence. Using vulnerability information and best-available data about attackers and the possibility that a threat would happen, estimate the probability of an occurrence.

d. Determine the magnitude of impact. Specify the severity and effects based on the mitigations and controls in place in response to an attack against the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of critical and sensitive information assets.

e. Determine risk. Factor in current mitigating controls and other risk treatments, analysis, or calculations to assess the likelihood and impact of a risk. Again, risk equals likelihood measures multiplied by impact measures.

3. Communicate results. Document and share the risk assessment report. Complete risk prioritization and evaluation of additional countermeasures and risk treatment. The results will support the overall risk management process.

4. Maintain the assessment. Update residual risks in a risk register or other repository for archiving risk methodologies and decisions used by the organization. Keep the risk assessment current by having a continuous risk management policy and adhering to it.

ONC-OCR HIPAA Security Toolkit Application

This tool is offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), in collaboration with the HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR).17 It was designed by a committee of industry volunteers and experts to help organizations assess their compliance to the HIPAA Security Rule. The survey asks hundreds of questions, and each question provides the types of documents or actions that would count as evidence of compliance. An organization can choose to upload the documents into the tool for archiving and quick future retrieval, or it can simply provide a link or note about the file location. The tool is extensive, and healthcare organizations of significant size and mission may utilize the entire database. Smaller organizations can tailor the survey according to their environment. The Security Risk Assessment (SRA) Toolkit resides on a personal computer or shared network drive as an application. It is not web based or networked to a central ONC or NIST database. It is not dependent on a specific hardware or software platform: Windows, Red Hat Linux, and macOS are all supported. The tool can be used and reused.

HIMSS Risk Assessment Toolkit

Primarily for HIPAA compliance in the United States, the Health Information Management Systems Society (HIMSS) has published a risk assessment (RA) toolkit to help providers conduct a full risk assessment. It incorporates many of the popular risk management frameworks and is intentioned for smaller sized healthcare provider organizations with limited resources for privacy and security activities. The toolkit includes a set of templates, whitepapers, analyses, best practices, and other reference materials that can help you comply with the guiding regulations in managing and securing PHI. It can also help you establish a comprehensive risk management program that would start with the risk assessment. This tool is created and maintained by HIMSS member volunteers and is intentionally vendor-agnostic.

The Data Security and Protection Toolkit

In the United Kingdom, the DSP Toolkit from the National Health Service (NHS) integrates the legal requirements and guidance into an information governance application. This tool enables organizations under the purview of the DSP requirements to perform self-assessments of their compliance. Using the toolkit, healthcare organizations in the United Kingdom can demonstrate that they properly maintain the confidentiality and security of personal information.18 The toolkit helps them control variance and partial compliance, and remediation activities can be documented, tracked, and communicated. This effectively supports UK healthcare organizations’ information governance compliance through continuous improvements. According to the UK NHS, using the DSP toolkit helps healthcare organizations evaluate themselves against regulatory standards and demonstrate their trustworthiness to their patients.

Desired Outcomes

Conducting risk assessments and implementing a good risk management program requires budget, time, and expertise. The results that come from assessments and analyses are valuable. The protection of healthcare information is without question the principle desired outcome of a risk management program. Several other desired outcomes or additional benefits maximize the usefulness of the risk management process. Information that is used to formulate a risk assessment will help the organization maintain a full accounting of its assets. Understanding the threats the organization faces along with the likelihood of occurrence can assist in business resiliency, which includes disaster recovery and business continuity planning. In fact, risk management information should be used to help business and clinical leaders develop a risk strategy. For initiatives that use cloud service providers or contemplate increased data sharing initiatives with external parties for healthcare improvements, knowing the risks and how such strategic imperatives may be helped or hindered by can save the organization time, money, and energy.

Role of Internal and External Audit and Assessment

Within the organization, the use of auditors who are competent in information technology and security is an imperative to providing assurance to the executive leadership and the board of directors. In the three lines of defense security model, introduced in Chapter 2, you should recognize the internal audit function as a third-line function. Information owners are the first line, and you, as a security professional, are second line. The auditors perform assessments to review proper implementation and operation of security controls. The internal audit function can strengthen an information security and privacy governance. In US healthcare organizations, an internal auditor typically reports directly to the audit committee of the board. The auditor is nonetheless an employee of the healthcare organization. The direct reporting to the board ensures objectivity in the auditor’s observations and opinions. The oversight that is provided may identify inefficiencies, poorly designed controls, and ineffective processes.

The role of oversight is just one valuable contribution of the auditor role; the same auditor can also serve the organization in more of a consultant role. This distinction does not change the reporting relationship to the board. The expertise and perspective of an auditor can be extremely helpful to management. When acting in the consultant role, an auditor can participate in projects, contribute to meetings, and otherwise give advice and suggest changes to improve the healthcare organization. The auditor should not blur the lines between consulting and oversight roles, however. When acting as a consultant, she should not use information gained in working internal issues to formulate an internal audit finding or observation. As an example of the consultant role, an internal audit can help your organization conduct a risk assessment. However, the auditor cannot identify, assess, evaluate, and respond to risk. Those are your responsibilities along with organization management. Some of the other tasks in which internal audit cannot participate are determining risk tolerances, making risk treatment decisions, and accepting accountability for risk management processes.

An effective organizational audit process includes a combination of external and internal audit teams in a comprehensive oversight program. External auditors would not act in a consultant role or as advocates for any management actions to manage risk. Information security risk is a complex and extensive profession with many specialized competencies. It is often necessary to get specific expertise from an external auditor to augment internal audit review. A good example of this is penetration testing using external suppliers who specialize in ethical hacking and conducting simulated attacks on the organization.

Another consideration for using external auditors is that over time, internal auditors can increase risk resulting from gaps in control assessments. This is potentially because of cumulative expectations from previous audits or because of shortcuts taken based on perceived understanding of organizational constructs. In short, internal auditors may develop bias, positive and negative, in overseeing the same program over many years. Although internal audit is not responsible for the information security risk assessments, external auditors can be used successfully to conduct a risk assessment, and that assessment and related auditor work papers that the external auditor agrees to share can be used to inform an internal audit. This may facilitate less costly and inefficient internal audits. In fact, the integration of external audits of information risk can permit internal auditors to focus review in areas where the external audit expressed findings, identified control weaknesses, or made observations.

If an organization does not consider using internal auditors and outsources the audit function, there are significant drawbacks. Using only external audits can be highly costly and inefficient because of the auditors’ unfamiliarity with the organization. Information gathering and coordination of resources can be a problem. An outsider’s view can potentially lead to misunderstandings when internal processes or management risk decisions are inaccurately judged or estimated. In reviewing security control effectiveness, the data is often persuasive but not conclusive.

Auditor professional judgement that provides meaning to results based on sampling or relatively subjective observations is always a factor with both internal and external audits. Internal auditors may provide a more applicable perspective in evaluation of control effectiveness. When used together, external and internal auditors reduce duplication of effort, strengthen the weak points, and reduce gaps to achieve the greatest level of assurance.

Identify Control Assessment Procedures Using Organization Risk Frameworks

You have a variety of choices when selecting a risk assessment procedure as part of a risk management process. Considerations include constraints on time and resources, along with the organization’s mission and size. Fortunately, leading examples of risk frameworks have several points in common, which makes them useful candidates because they can be customized to fit within your constraints. Additionally, you can use ISO/IEC 27014, Information technology – Security techniques – Governance of information security, as a guide, which offers some other common attributes:

• Consistent Control of specifications and how they are measured must remain constant to build trust and value for control owners and executive leadership.

• Measurable The risk management system must be able to demonstrate baseline and progress toward risk reduction and information security maturity objectives.