5.1.4 Empirical Evidence on Top Incomes and Top Tax Rates

Micro-Level Tax Reform Studies. A very large literature has used tax reforms and micro-level tax return data to identify the elasticity of reported incomes with respect to the net-of-tax marginal rate. Those studies typically compare changes in pre-tax incomes of groups affected by a tax reform to changes in pre-tax incomes of groups unaffected by the reform. Hence, such tax reform-based analysis can only estimate short-term responses (typically 1–5 years) to tax changes. This literature, surveyed in Saez, Slemrod, and Giertz (2012), obtains three key conclusions that we briefly summarize here. First, there is substantial heterogeneity in the estimates: Many studies finding relatively small elasticity estimates (below 0.25), but some have found that tax reform episodes do generate large short-term behavioral responses, which imply large elasticities, particularly at the top of the income distribution. Second however, all the cases with large behavioral responses are due to tax avoidance such as retiming or income shifting. To our knowledge, none of the empirical tax reform studies to date have shown large responses due to changes in real economic behavior such as labor supply or business creation.65 Furthermore, “anatomy analysis” shows that the large tax avoidance responses obtained are always the consequence of poorly designed tax systems offering arbitrage opportunities66 or income retiming opportunities in anticipation of or just after-tax reforms.67 When the tax system offers few tax avoidance opportunities, short-term responses to changes in tax rates are fairly modest with elasticities typically below 0.25.68 Therefore, the results from this literature fit well with the tax avoidance model presented above with fairly small real elasticities and potentially large avoidance elasticities that can be sharply reduced through better tax design.

International Mobility. Mobility responses to taxation often loom larger in the policy debate on tax progressivity than traditional within country labor supply responses.69 A large literature has shown that capital income mobility is a substantial concern (see e.g. the chapter by Keen and Konrad in this volume). However, there is much less empirical work on the effect of taxation on the spatial mobility of individuals, especially among high-skilled workers. A small literature has considered the mobility of people across local jurisdictions within countries.70 While mobility costs within a country may be small, within country variations in taxes also tend to be modest. Therefore, it is difficult to extrapolate from those studies to international migration where both tax differentials and mobility costs are much higher. There is very little empirical work on the effect of taxation on international mobility partly due to lack of micro data with citizenship information and challenges in identifying causal tax effects on migration. In recent decades however, many countries, particularly in Europe, have introduced preferential tax rates for specific groups of foreign workers, and often highly paid foreign workers (see OECD, 2011c, chap. 4, Table 4.1, p. 138 for a summary of all such existing schemes). Such preferential tax schemes offer a promising route to identify tax induced mobility effects, recently exploited in two studies.

Kleven, Landais, and Saez (2013) study the tax induced mobility of professional football players in Europe and find substantial mobility elasticities. The mobility elasticity of the number of domestic players with respect to the domestic net-of-tax rate is relatively small, around .15. However, the mobility elasticity of the number of foreign players with respect to the net-of-tax rate that applies to foreign players is much larger, around 1. This difference is due to the fact that most players still play in their home country. Kleven et al. (in press) confirm that this latter result applies to the broader market of highly skilled foreign workers and not only football players. They show, in the case study of Denmark, that the preferential tax scheme for highly paid foreigners introduced in 1991 doubled the number of high earning foreigners in Denmark. This translates again into an elasticity of the number of foreign workers with respect to the net-of-tax rate above one.

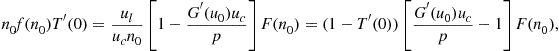

Those results imply that, from a single country’s perspective, as the number of foreigners at the top is still relatively small, the migration elasticity ![]() of all top earners with respect to a single net-of-tax top rate is still relatively small, likely below .25 for most countries. This is the relevant elasticity to use in formula (10). Hence, the top income tax rate calculation is unlikely to be drastically affected by migration effects. However, this elasticity is likely to grow overtime as labor markets become better integrated and the fraction of foreign workers grows. Nevertheless, because the elasticity of the number of foreign workers with respect to the net-of-tax rate applying to foreign workers is so large, it is indeed advantageous from a single country perspective to offer such preferential tax schemes. This could explain why such schemes have proliferated in Europe in recent years. Such schemes are typical beggar-thy-neighbor policies which reduce the collective ability of countries to tax top earners. Hence, regulating such schemes at a supranational level (for example at the European Union level for European countries) is likely to become a key element in tax coordination policy debates.

of all top earners with respect to a single net-of-tax top rate is still relatively small, likely below .25 for most countries. This is the relevant elasticity to use in formula (10). Hence, the top income tax rate calculation is unlikely to be drastically affected by migration effects. However, this elasticity is likely to grow overtime as labor markets become better integrated and the fraction of foreign workers grows. Nevertheless, because the elasticity of the number of foreign workers with respect to the net-of-tax rate applying to foreign workers is so large, it is indeed advantageous from a single country perspective to offer such preferential tax schemes. This could explain why such schemes have proliferated in Europe in recent years. Such schemes are typical beggar-thy-neighbor policies which reduce the collective ability of countries to tax top earners. Hence, regulating such schemes at a supranational level (for example at the European Union level for European countries) is likely to become a key element in tax coordination policy debates.

Cross Country and Time Series Evidence. The simplest way to obtain evidence on the long-term behavioral responses of top incomes to tax rates is to use long time series analysis within a country or across countries. Data on top incomes overtime and across countries have been compiled by a number of recent studies (see Atkinson et al., 2011 for a survey) and gathered in the World Top Incomes Database (Alvaredo, Atkinson, Piketty & Saez 2011. A few recent studies have analyzed the link between top income shares and top tax rates (Atkinson & Leigh, 2010; Roine, Vlachos, & Waldenstrom, 2009; Piketty et al., 2011).

There is a strong negative correlation between top tax rates and top income shares, such as the fraction of total income going to the top 1% of the distribution. This long-run correlation is present overtime within countries as well as across countries. As an important caveat, the correlation between top tax rates and top income shares may not be causal as other policies potentially affecting top income shares, such as financial or industrial regulation or policies affecting Unions, may be correlated with top tax rate policy, creating an omitted variable bias. Alternatively and in reverse causality, higher top income shares may increase the political influence of top earners leading to lower top tax rates.71

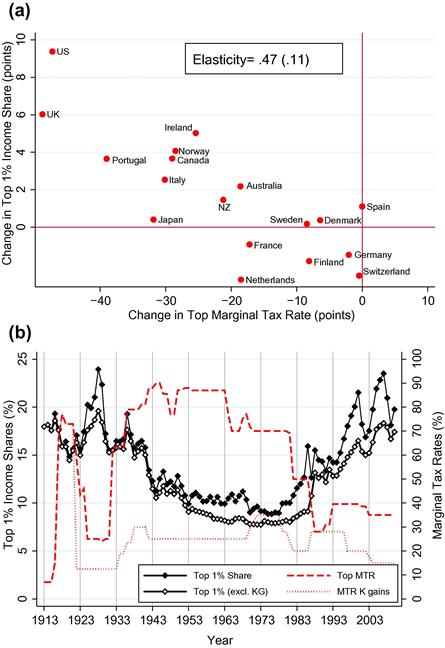

Panel A in Figure 5 illustrates the cross-country evidence. It plots the change in top income shares from 1960–1964 to 2004–2009 (on the y-axis) against the change in the top marginal tax rate (on the x-axis) for 18 OECD countries. The figure shows a very clear and strong correlation between the cut in top tax rates and the increase in the top 1% income share with interesting heterogeneity. Countries such as France, Germany, Spain, Denmark, or Switzerland which did not experience any significant top rate tax cut did not experience large changes in top 1% income shares. Among the countries which experienced significant top rate cuts, some experience a large increase in top income shares (all five English speaking countries but also Norway and Finland) while others experience only modest increases in top income shares (Japan, Italy, Sweden, Portugal, and the Netherlands). Interestingly, no country experiences a significant increase in top income shares without implementing significant top rate tax cuts. Overall, the elasticity implied by this correlation is large, above 0.5. However, this evidence cannot tell whether the elasticity is due to real effects, tax evasion, or rent-seeking effects.

Figure 5 Top marginal tax rates and top incomes shares. This figure is from Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2011). Panel A depicts the change in pre-tax top income shares against the change in pre-tax top income tax rate from 1960–1964 to 2005–2009 based on data for 18 OECD countries (exact years depend on availability of top income share data in the World Top Incomes Database (Alvaredo et al., 2011)). Panel B depicts the pre-tax top 1% US income shares including realized capital gains in full diamonds and excluding realized capital gains in empty diamonds from 1913 to 2010. Computations are based on family market cash income. Income excludes government transfers and is before individual taxes (source is Piketty and Saez (2003), series updated to 2010). Panel B also depicts the top marginal tax rate on ordinary income and on realized long-term capital gains.

Panel B in Figure 5 illustrates the time series evidence for the case of the United States. It depicts the top 1% income shares including realized capital gains (pictured with full diamonds) and excluding realized capital gains (the empty diamonds) since 1913, which marks the introduction of the US federal income tax. Both top income shares, whether including or excluding realized capital gains, display an overall U-shape over the century. Panel A also displays (on the right y-axis) the federal individual income top marginal tax rate for ordinary income (dashed line), and for long-term realized capital gains (dotted line). Two important lessons emerge from this panel. Considering first the top income share excluding realized capital gains which corresponds roughly to income taxed according to the regular progressive schedule, there is a clear negative overall correlation between the top 1% income share and the top marginal tax rate, showing again that the elasticity of reported income with respect to the net-of-tax rate is large in the long run. Second, the correlation between the top 1% income share and the top tax rate also holds for the series including capital gains. Realized capital gains have been traditionally tax favored (as illustrated by the gap between the top tax rate and the tax rate on realized capital gains in the figure) and have constituted the main channel for tax avoidance of upper incomes.72 This suggests that, in contrast to short-run tax reform analysis, income shifting responses cannot be the main channel creating the long-run correlation between top income shares and top tax rates.73

If the long-term correlation between top income shares and top tax rates is not driven by tax avoidance, the key question is whether it is driven by real supply side responses or whether it reflects rent-seeking effects whereby top earners can gain at the expense of others when top rates are low. In principle, the two types of behavioral responses can be distinguished by looking at economic growth as supply-side responses affect economic growth while rent-seeking responses do not. Piketty et al. (2011) analyze cross-country time series for OECD countries since 1960 and do not find any evidence that cuts in top tax rates stimulate growth. This suggests that rent-seeking effects likely play a role in the correlation between top tax rates and top incomes, and therefore that optimal top tax rates might be substantially larger than what it commonly assumed (say, above 80% rather than 50–60%). In our view, this is the right model to account for the quasi-confiscatory top tax rates during large parts of the 20th century (particularly in the US and in the UK; see Figure 1 above). Needless to say, more compelling empirical identification would be very useful to cast further light on this key issue for the optimal taxation of top earners.74

5.2 Optimal Nonlinear Schedule

5.2.1 Continuous Model of Mirrlees

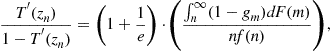

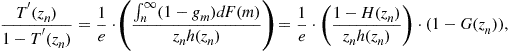

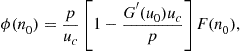

It is possible to obtain the formula for the optimal marginal tax rate ![]() at income level

at income level ![]() for the fully general nonlinear income tax using a similar variational method as the one used to derive the top income tax rate. To simplify the exposition, we consider the case with no income effects, where labor supply depends solely on the net-of-tax rate

for the fully general nonlinear income tax using a similar variational method as the one used to derive the top income tax rate. To simplify the exposition, we consider the case with no income effects, where labor supply depends solely on the net-of-tax rate ![]() .75 We present in the text a graphical proof adapted from Saez (2001) and Diamond and Saez (2011) and we relegate to the appendix the formal presentation and derivation in the standard Mirrlees model with no income effects (as in the analysis of Diamond, 1998).

.75 We present in the text a graphical proof adapted from Saez (2001) and Diamond and Saez (2011) and we relegate to the appendix the formal presentation and derivation in the standard Mirrlees model with no income effects (as in the analysis of Diamond, 1998).

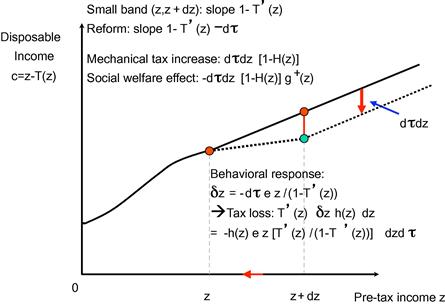

Figure 6 depicts the optimal marginal tax rate derivation at income level ![]() . Again, the horizontal axis in Figure 6 shows pre-tax income, while the vertical axis shows disposable income. Consider a situation in which the marginal tax rate is increased by

. Again, the horizontal axis in Figure 6 shows pre-tax income, while the vertical axis shows disposable income. Consider a situation in which the marginal tax rate is increased by ![]() in the small band from

in the small band from ![]() to

to ![]() , but left unchanged anywhere else. The tax reform has three effects.

, but left unchanged anywhere else. The tax reform has three effects.

Figure 6 Derivation of the optimal marginal tax rate at income level ![]() . The figure, adapted from Diamond and Saez (2011), depicts the optimal marginal tax rate derivation at income level

. The figure, adapted from Diamond and Saez (2011), depicts the optimal marginal tax rate derivation at income level ![]() by considering a small reform around the optimum, whereby the marginal tax rate in the small band

by considering a small reform around the optimum, whereby the marginal tax rate in the small band ![]() is increased by

is increased by ![]() . This reform mechanically increases taxes by

. This reform mechanically increases taxes by ![]() for all taxpayers above the small band, leading to a mechanical tax increase

for all taxpayers above the small band, leading to a mechanical tax increase ![]() and a social welfare cost of

and a social welfare cost of ![]() . Assuming away income effects, the only behavioral response is a substitution effect in the small band: The

. Assuming away income effects, the only behavioral response is a substitution effect in the small band: The ![]() taxpayers in the band reduce their income by

taxpayers in the band reduce their income by ![]() leading to a tax loss equal to

leading to a tax loss equal to ![]() . At the optimum, the three effects cancel out leading to the optimal tax formula

. At the optimum, the three effects cancel out leading to the optimal tax formula ![]() , or equivalently

, or equivalently ![]() after introducing

after introducing ![]() .

.

First, the mechanical tax increase, leaving aside behavioral responses, will be the gap between the solid and dashed lines, shown by the vertical arrow equal to ![]() . The total mechanical tax increase is

. The total mechanical tax increase is ![]() as there are

as there are ![]() individuals above

individuals above ![]() .

.

Second, this tax increase creates a social welfare cost of ![]() where

where ![]() is defined as the average (unweighted) social marginal welfare weight for individuals with income above

is defined as the average (unweighted) social marginal welfare weight for individuals with income above ![]() .

.

Third, there is a behavioral response to the tax change. Those in the income range from ![]() to

to ![]() have a behavioral response to the higher marginal tax rate, shown by the horizontal line pointing left. Assuming away income effects, this is the only behavioral response; those with income levels above

have a behavioral response to the higher marginal tax rate, shown by the horizontal line pointing left. Assuming away income effects, this is the only behavioral response; those with income levels above ![]() face no change in marginal tax rates and hence have no behavioral response. A taxpayer in the small band reduces her income by

face no change in marginal tax rates and hence have no behavioral response. A taxpayer in the small band reduces her income by ![]() where

where ![]() is the elasticity of earnings

is the elasticity of earnings ![]() with respect to the net-of-tax rate

with respect to the net-of-tax rate ![]() . As there are

. As there are ![]() taxpayers in the band, those behavioral responses lead to a tax loss equal to

taxpayers in the band, those behavioral responses lead to a tax loss equal to ![]() .76

.76

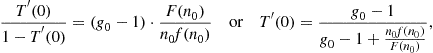

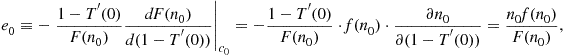

At the optimum, the three effects should cancel out so that ![]() . Define the local Pareto parameter as

. Define the local Pareto parameter as ![]() .77 This leads to the following optimal tax formula

.77 This leads to the following optimal tax formula

![]() (11)

(11)

Formula (11) has essentially the same form as (7). Five further points are worth noting.

First, the simple graphical proof shows that the formula does not depend on the strong homogeneity assumptions of the standard Mirrlees model where individuals differ solely through a skill parameter. This implies that the formula actually carries over to heterogeneous populations as is the case of the basic linear tax rate formula (3).78

Second, the optimal tax rate naturally decreases with ![]() , the average social marginal welfare weight above

, the average social marginal welfare weight above ![]() . Under standard assumptions where social marginal welfare weights decrease with income,

. Under standard assumptions where social marginal welfare weights decrease with income, ![]() is decreasing in

is decreasing in ![]() . With no income effects, the average social marginal welfare weight is equal to one (see Section 3.1) so that

. With no income effects, the average social marginal welfare weight is equal to one (see Section 3.1) so that ![]() and

and ![]() for

for ![]() . This immediately implies that

. This immediately implies that ![]() for any

for any ![]() , one of the few general results coming out of the Mirrlees model and first demonstrated by Mirrlees (1971) and Seade (1982).79 A decreasing

, one of the few general results coming out of the Mirrlees model and first demonstrated by Mirrlees (1971) and Seade (1982).79 A decreasing ![]() tends to make the tax system more progressive. Note that the extreme Rawlsian case has

tends to make the tax system more progressive. Note that the extreme Rawlsian case has ![]() for all

for all ![]() except at

except at ![]() (assuming realistically that the most disadvantaged are those with no earnings). In that case, the formula simplifies to

(assuming realistically that the most disadvantaged are those with no earnings). In that case, the formula simplifies to ![]() and the optimal tax system maximizes tax revenue raised to make the lump sum demogrant

and the optimal tax system maximizes tax revenue raised to make the lump sum demogrant ![]() as large as possible.

as large as possible.

Third, the optimal tax rate decreases with the elasticity ![]() at income level

at income level ![]() as a higher elasticity leads to larger efficiency costs in the small band

as a higher elasticity leads to larger efficiency costs in the small band ![]() . Note that this elasticity remains a pure substitution elasticity even in the presence of income effects.80

. Note that this elasticity remains a pure substitution elasticity even in the presence of income effects.80

Fourth, the optimal tax rate decreases with the local Pareto parameter ![]() which reflects the ratio of the total income of those affected by the marginal tax rate at

which reflects the ratio of the total income of those affected by the marginal tax rate at ![]() relative to the number of people at higher income levels. The intuition for this follows the derivation from Figure 6. Increasing

relative to the number of people at higher income levels. The intuition for this follows the derivation from Figure 6. Increasing ![]() creates efficiency costs proportional to the number of people at income level

creates efficiency costs proportional to the number of people at income level ![]() times the income level

times the income level ![]() while it raises more taxes (with no distortion) from everybody above

while it raises more taxes (with no distortion) from everybody above ![]() . As shown on Figure 4 for the US case, empirically

. As shown on Figure 4 for the US case, empirically ![]() first increases and then decreases before being approximately constant in the top tail. Hence, when

first increases and then decreases before being approximately constant in the top tail. Hence, when ![]() is large, formula (11) converges to the optimal top rate formula (7) that we derived earlier.

is large, formula (11) converges to the optimal top rate formula (7) that we derived earlier.

Fifth, suppose the government has no taste for redistribution and wants to raise an exogenous amount of revenue while minimizing efficiency costs. If lump sum taxes are realistically ruled out because those with no earnings could not possibly pay them, then the optimal tax system is still given by ( 11) with constant social marginal welfare weights and hence constant ![]() set to exactly raise the needed amount of exogenous revenue (Saez, 1999, chap. 3).

set to exactly raise the needed amount of exogenous revenue (Saez, 1999, chap. 3).

Increasing Marginal Tax Rates at the Top. With an elasticity ![]() constant across income groups, as

constant across income groups, as ![]() decreases with

decreases with ![]() and

and ![]() also decreases with

also decreases with ![]() in the upper part of the distribution (approximately the top 5% in the US case, see Figure 4), formula (11) implies that the optimal marginal tax rate should increase with

in the upper part of the distribution (approximately the top 5% in the US case, see Figure 4), formula (11) implies that the optimal marginal tax rate should increase with ![]() at the upper end, i.e., the income tax should be progressive at the top. Diamond (1998) provides formal theoretical results in the Mirrlees model with no income effects.

at the upper end, i.e., the income tax should be progressive at the top. Diamond (1998) provides formal theoretical results in the Mirrlees model with no income effects.

Numerical Simulations. For low ![]() decreases but

decreases but ![]() increases. Numerical simulations calibrated using the actual US earnings distribution presented in Saez (2001) show that the

increases. Numerical simulations calibrated using the actual US earnings distribution presented in Saez (2001) show that the ![]() effect dominates at the bottom so that the marginal tax rate is high and decreasing for low

effect dominates at the bottom so that the marginal tax rate is high and decreasing for low ![]() . We come back to this important issue when we discuss the optimal profile of transfers below. Therefore, assuming that the elasticity is constant with

. We come back to this important issue when we discuss the optimal profile of transfers below. Therefore, assuming that the elasticity is constant with ![]() , the optimal marginal tax rate in the Mirrlees model is U-shaped with income, first decreasing with income and then increasing with income before converging to its limit value given by formula (7).

, the optimal marginal tax rate in the Mirrlees model is U-shaped with income, first decreasing with income and then increasing with income before converging to its limit value given by formula (7).

5.2.2 Discrete Models

Stiglitz (1982) developed the 2 skill-type discrete version of the Mirrlees (1971) model where individuals can have either a low or a high wage rate. This discrete model has been used widely in the subsequent literature because it has long been perceived as more tractable than the continuous model of Mirrlees. However, the discrete model is perhaps deceiving when it comes to understanding optimal tax progressivity. Indeed, the zero top marginal tax rate result implies that the marginal tax rate on the highest skill is zero and hence lower than the marginal tax rate on the lowest skill, suggesting that the marginal tax rate should decrease with earnings. Furthermore, it is impossible to express optimal tax formulas in the Stiglitz (1982) model in terms of estimable statistics and hence to quantitatively calibrate the model.

More recently, Piketty (1997) introduced and Saez (2002a) further developed an alternative form of discrete Mirrlees model with a finite number of possible earnings levels ![]() (corresponding for example to different possible jobs) but a continuum of individual types so that the fraction of individuals at each earnings level is a smooth function of the tax system. This model generates formulas close to the continuum case, and can also be easily extended to incorporate extensive labor supply responses, as we shall see.

(corresponding for example to different possible jobs) but a continuum of individual types so that the fraction of individuals at each earnings level is a smooth function of the tax system. This model generates formulas close to the continuum case, and can also be easily extended to incorporate extensive labor supply responses, as we shall see.

Formally, individual ![]() has a utility function

has a utility function ![]() defined on after-tax income

defined on after-tax income ![]() and job choice

and job choice ![]() . Each individual chooses

. Each individual chooses ![]() to maximize

to maximize ![]() where

where ![]() is the after-tax reward in occupation

is the after-tax reward in occupation ![]() . For a given tax and transfer schedule

. For a given tax and transfer schedule ![]() , a fraction

, a fraction ![]() of individuals choose occupation

of individuals choose occupation ![]() . It is assumed that the tastes for work embodied in the individual utilities are smoothly distributed so that the aggregate functions

. It is assumed that the tastes for work embodied in the individual utilities are smoothly distributed so that the aggregate functions ![]() are differentiable. Denoting by

are differentiable. Denoting by ![]() the occupational choice of individual

the occupational choice of individual ![]() , the government chooses

, the government chooses ![]() so as to maximize welfare

so as to maximize welfare

![]()

Even though the population is potentially very heterogeneous, as possible work outcomes are in finite number, the maximization problem is a simple finite dimensional maximization problem. The first order condition with respect to ![]() is

is

(12)

(12)

Hence, ![]() is the average social marginal welfare weight among individuals in occupation

is the average social marginal welfare weight among individuals in occupation ![]() .81

.81

This model allows for any type of behavioral responses. Two special cases are of particular interest: pure intensive responses as in the standard Mirrlees (1971) model and pure extensive responses. We consider in this section the intensive model case and defer to Section 5.3.2 the extensive model case.

The intensive model. The intensive model with no income effects (first developed by Piketty, 1997) can be obtained by assuming that the population is partitioned into ![]() groups. An individual in group

groups. An individual in group ![]() can only work in two adjacent occupations

can only work in two adjacent occupations ![]() and

and ![]() . For example, with no effort the individual can hold job

. For example, with no effort the individual can hold job ![]() and with some effort the individual can obtain job

and with some effort the individual can obtain job ![]() .82 This implies that the function

.82 This implies that the function ![]() depends only on

depends only on ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Assuming no income effects, with a slight abuse of notation,

. Assuming no income effects, with a slight abuse of notation, ![]() can be expressed as

can be expressed as ![]() . In that context, we can denote by

. In that context, we can denote by ![]() the marginal tax rate between earnings levels

the marginal tax rate between earnings levels ![]() and

and ![]() and by

and by ![]() the elasticity of the fraction of individuals in occupation

the elasticity of the fraction of individuals in occupation ![]() with respect to the net-of-tax rate

with respect to the net-of-tax rate ![]() . The optimal tax formula (12) can be rearranged as:

. The optimal tax formula (12) can be rearranged as:

![]() (13)

(13)

The proof is presented in Saez (2002a). Note that the form of the optimal formula is actually very close the continuum case where the marginal tax rate from Eq. (11) can also be written as: ![]() .

.

5.3 Optimal Profile of Transfers

5.3.1 Intensive Margin Responses

It is possible to obtain a formula for the optimal phase-out rate of the demogrant in the optimal income tax model of Mirrlees (1971) where labor supply responds only through the intensive margin.

Recall first that when the minimum income ![]() is positive, the optimal marginal tax rate at the very bottom is zero (this result was first proved by Seade, 1977). This can be seen from formula (11) as

is positive, the optimal marginal tax rate at the very bottom is zero (this result was first proved by Seade, 1977). This can be seen from formula (11) as ![]() .83

.83

However, the empirically relevant case is ![]() with a non-zero fraction

with a non-zero fraction ![]() of the population not working and earning zero. In that case, the optimal phase-out rate

of the population not working and earning zero. In that case, the optimal phase-out rate ![]()

at the bottom can be written as:

![]() (14)

(14)

where ![]() is the average social marginal welfare weight on zero earners and

is the average social marginal welfare weight on zero earners and ![]() is the elasticity of the fraction non-working

is the elasticity of the fraction non-working ![]() with respect to the bottom net-of-tax rate

with respect to the bottom net-of-tax rate ![]() with a minus sign so that

with a minus sign so that ![]() .84 This formula is proved by Saez (2002a) in the discrete model presented above.85

.84 This formula is proved by Saez (2002a) in the discrete model presented above.85

The formula also applies in the standard Mirrlees model although it does not seem to have been ever noticed and formally presented. We present the proof in the standard Mirrlees model in the appendix. In the text, we present a simple graphical proof adapted from Diamond and Saez (2011) using the discrete model with intensive margin responses presented above.

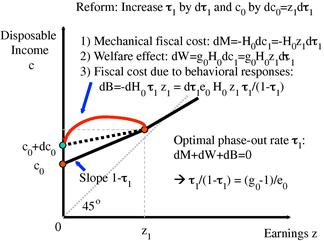

As illustrated on Figure 7, suppose that low ability individuals can choose either to work and earn ![]() or not work and earn zero (

or not work and earn zero (![]() ). The government offers a transfer

). The government offers a transfer ![]() to those not working phased-out at rate

to those not working phased-out at rate ![]() so that those working receive on net

so that those working receive on net ![]() . In words, non-workers keep a fraction

. In words, non-workers keep a fraction ![]() of their earnings should they work and earn

of their earnings should they work and earn ![]() . Therefore, increasing

. Therefore, increasing ![]() discourages some low income workers from working. Suppose now that the government increases both the

discourages some low income workers from working. Suppose now that the government increases both the ![]() by

by ![]() and the phase-out rate by

and the phase-out rate by ![]() leaving the tax schedule unchanged for those with income equal to or above

leaving the tax schedule unchanged for those with income equal to or above ![]() so that

so that ![]() as depicted on Figure 7. The fiscal cost is

as depicted on Figure 7. The fiscal cost is ![]() but the welfare benefit is

but the welfare benefit is ![]() where

where ![]() is the social welfare weight on non-workers. Because behavioral responses take place along the intensive margin only in the Mirrlees model, with no income change above

is the social welfare weight on non-workers. Because behavioral responses take place along the intensive margin only in the Mirrlees model, with no income change above ![]() , the labor supply of those above

, the labor supply of those above ![]() is not affected by the reform. By definition of

is not affected by the reform. By definition of ![]() , a number

, a number ![]() of low income workers stop working creating a revenue loss of

of low income workers stop working creating a revenue loss of ![]() . At the optimum, the three effects sum to zero leading to the optimal bottom rate formula (14). Three points are worth noting about formula (14).

. At the optimum, the three effects sum to zero leading to the optimal bottom rate formula (14). Three points are worth noting about formula (14).

Figure 7 Optimal bottom marginal tax rate with only intensive labor supply responses. The figure, adapted from Diamond and Saez (2011), depicts the derivation of the optimal marginal tax rate at the bottom in the discrete Mirrlees (1971) model with labor supply responses along the intensive margin only. Let ![]() be the fraction of the population not working. This is a function of

be the fraction of the population not working. This is a function of ![]() , the net-of-tax rate at the bottom, with elasticity

, the net-of-tax rate at the bottom, with elasticity ![]() . We consider a small reform around the optimum: The government increases the maximum transfer by

. We consider a small reform around the optimum: The government increases the maximum transfer by ![]() by increasing the phase-out rate by

by increasing the phase-out rate by ![]() leaving the tax schedule unchanged for those with income above

leaving the tax schedule unchanged for those with income above ![]() . This creates three effects which cancel out at the optimum. At the optimum, we have

. This creates three effects which cancel out at the optimum. At the optimum, we have ![]() or

or ![]() . Under standard redistributive preferences,

. Under standard redistributive preferences, ![]() is large implying that

is large implying that ![]() is large.

is large.

First, if society values redistribution toward zero earners, then ![]() is likely to be large (relative to 1). In that case,

is likely to be large (relative to 1). In that case, ![]() is going to be high even if the elasticity

is going to be high even if the elasticity ![]() is large. For example, if

is large. For example, if ![]() and

and ![]() then

then ![]() , a very high phase-out rate. The intuition is simple: increasing transfers by increasing the phase-out rate is valuable if

, a very high phase-out rate. The intuition is simple: increasing transfers by increasing the phase-out rate is valuable if ![]() is large, the fiscal cost due to the behavioral response is relatively modest as those dropping out of the labor force would have had very modest earnings anyway. The phase-out rate is highest in the Rawlsian case where all the social welfare weight is concentrated at the bottom.86

is large, the fiscal cost due to the behavioral response is relatively modest as those dropping out of the labor force would have had very modest earnings anyway. The phase-out rate is highest in the Rawlsian case where all the social welfare weight is concentrated at the bottom.86

Second and conversely, if society considers that non-workers are primarily free-loaders taking advantage of transfers, then ![]() is conceivable. In that case, the optimal phase-out rate is negative and the government provides higher transfers for low income earners rather than those out-of-work. Naturally, this cannot happen under the standard assumption where social marginal welfare weights decrease with income.

is conceivable. In that case, the optimal phase-out rate is negative and the government provides higher transfers for low income earners rather than those out-of-work. Naturally, this cannot happen under the standard assumption where social marginal welfare weights decrease with income.

Finally, note that it is not possible to obtain an explicit formula for the optimal demogrant ![]() as the demogrant is determined in general equilibrium. This is a general feature of optimal tax problems (in the optimal linear tax rate, the demogrant was also deduced from the optimal tax rate

as the demogrant is determined in general equilibrium. This is a general feature of optimal tax problems (in the optimal linear tax rate, the demogrant was also deduced from the optimal tax rate ![]() using the government budget constraint).

using the government budget constraint).

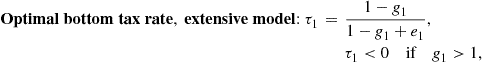

5.3.2 Extensive Margin Responses

The optimality of a traditional means-tested transfer program with a high phase-out rate depends critically on the assumption of intensive labor supply responses. Empirically however, there is substantial evidence that labor supply responses, particularly among low income earners, are also substantial along the extensive margin with less compelling evidence of intensive marginal labor supply response.87 In that case, it is optimal to give higher transfers to low income workers rather than non-workers, which amounts to a negative phase-out rate, as with the current Earned Income Tax Credit (Diamond, 1980; Saez, 2002a).

To see this, consider now a model where behavioral responses of low- and mid-income earners take place through the extensive elasticity only, i.e., whether or not to work, and that earnings when working do not respond to marginal tax rates. Within the general discrete model developed in Section 5.2.2, the extensive model can be obtained by assuming that each individual can only work in one occupation or be unemployed. This can be embodied in the individual utility functions by assuming that ![]() for all occupations

for all occupations ![]() except the one corresponding to the skill of the individual. This structure implies that the fraction of the population

except the one corresponding to the skill of the individual. This structure implies that the fraction of the population ![]() working in occupation

working in occupation ![]() depends only on

depends only on ![]() and

and ![]() for

for ![]() . As a result, and using the fact that

. As a result, and using the fact that ![]() , and defining the elasticity of participation

, and defining the elasticity of participation ![]() , Eq. (12) becomes,

, Eq. (12) becomes,

![]() (15)

(15)

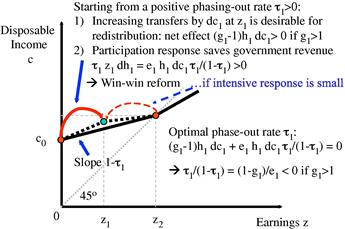

To obtain this result, as depicted on Figure 8, suppose the government starts from a transfer scheme with a positive phase-out rate ![]() and introduces an additional small in-work benefit

and introduces an additional small in-work benefit ![]() that increases net transfers to low income workers earning

that increases net transfers to low income workers earning ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the fraction of low income workers with earnings

be the fraction of low income workers with earnings ![]() . The reform has again three effects.

. The reform has again three effects.

Figure 8 Optimal bottom marginal tax rate with extensive labor supply responses. The figure, adapted from Diamond and Saez (2011), depicts the derivation of the optimal marginal tax rate at the bottom in the discrete model with labor supply responses along the extensive margin only. Starting with a positive phase-out rate ![]() , the government introduces a small in-work benefit

, the government introduces a small in-work benefit ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the fraction of low income workers with earnings

be the fraction of low income workers with earnings ![]() , and let

, and let ![]() be the elasticity of

be the elasticity of ![]() with respect to the participation net-of-tax rate

with respect to the participation net-of-tax rate ![]() . The reform has three standard effects: mechanical fiscal cost

. The reform has three standard effects: mechanical fiscal cost ![]() , social welfare gain,

, social welfare gain, ![]() , and tax revenue gain due to behavioral responses

, and tax revenue gain due to behavioral responses ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() implying that

implying that ![]() cannot be optimal. The optimal

cannot be optimal. The optimal ![]() is such that

is such that ![]() implying that

implying that ![]() .

.

First, the reform has a mechanical fiscal cost ![]() for the government. Second, it generates a social welfare gain,

for the government. Second, it generates a social welfare gain, ![]() where

where ![]() is the marginal social welfare weight on low income workers with earnings

is the marginal social welfare weight on low income workers with earnings ![]() . Third, there is a tax revenue gain due to behavioral responses

. Third, there is a tax revenue gain due to behavioral responses ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . In that case, if

. In that case, if ![]() , then

, then ![]() , implying that

, implying that ![]() cannot be optimal. The optimal

cannot be optimal. The optimal ![]() is such that

is such that

![]()

implying that the optimal phase-out rate at the bottom is given by:

(16)

(16)

Intuitively, starting with a transfer system with a positive phase-out rate as depicted on Figure 8 and ignoring behavioral responses, an in-work benefit reform depicted on Figure 8 is desirable if the government values redistribution to low income earners. If behavioral responses are solely along the extensive margin, this reform induces some non-workers to start working to take advantage of the in-work benefit. However, because we start from a situation with a positive phase-out rate, this behavioral response increases tax revenue as low income workers still end up receiving a smaller transfer than non-workers. Hence, the in-work benefit increases social welfare implying that a positive phase-out rate cannot be optimal.88 Another way to see this is the following. Increasing ![]() distorts the labor supply decision of all types of workers who might quit working. In contrast, increasing

distorts the labor supply decision of all types of workers who might quit working. In contrast, increasing ![]() distorts labor supply of low-skilled workers only. Hence an in-work benefit is less distortionary than an out-of-work benefit in the pure extensive model.

distorts labor supply of low-skilled workers only. Hence an in-work benefit is less distortionary than an out-of-work benefit in the pure extensive model.

5.3.3 Policy Practice

In practice, both extensive and intensive elasticities are present. An intensive margin response would induce those earning slightly more than the minimum to reduce labor supply to take advantage of the in-work benefit, thus reducing tax revenue. Therefore, the government has to trade off the two effects. If, as empirical studies show (see e.g., Blundell & MaCurdy, 1999 for a survey), the extensive elasticity of choosing whether to participate in the labor market is large relative to the intensive elasticity of choosing how many hours to work, initially low (or even negative) phase-out rates combined with high positive phase-out rates further up the distribution would be the optimal profile.

In recent decades in most OECD countries, a concern arose that traditional welfare programs overly discouraged work and there has been a marked shift toward lowering the marginal tax rate for low earners through a combination of: (a) introduction and then expansion of in-work benefits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit in the United States or the Family Credit in the United Kingdom;89 (b) reduction of the statutory phase-out rates in transfer programs for earned income as under the U.S. welfare reform; and (c) reduction of payroll taxes for low income earners.90 Those reforms are consistent with the logic of the optimal tax model we have outlined, as they both encourage labor force participation and provide transfers to low income workers seen as a deserving group. As we saw on Figure 2, the current US system imposes marginal tax rates close to zero on the first $15,000 of earnings but significantly higher marginal rates between $15,000 and $30,000.

How can we explain however that means-tested social welfare programs with high phase-out rates were widely used in prior decades? Historically, most means-tested transfer programs started as narrow programs targeting specific groups deemed unable to earn enough such as widows with children, the elderly, or the disabled. For example, the ancestor of the traditional US welfare program (Aid for Families with Dependent Children, renamed Temporary Aid for Needy Families after the 1996 welfare reform) were “mothers’ pensions” state programs providing help primarily to widows with children and no resources (Katz, 1996). If beneficiaries cannot work but differ in terms of unearned income (for example, the presence of a private pension), then the optimal redistribution scheme is indeed a transfer combined with a 100% phasing-out rate. As governments expanded the scope of transfers, a larger fraction of beneficiaries were potentially able to work. The actual tax policy response to this moral hazard problem over the last few decades has been remarkably close to the lessons from optimal tax theory we have outlined.

Note that following the Reagan and Thatcher conservative revolutions two other elements likely played a role in the shift from traditional means-tested programs toward in-work benefits. First, it is conceivable that society has less tolerance for non-workers living off government transfers because it believes, rightly or wrongly, that most of such non-workers could actually work and earn a living on their own absent government transfers. This means that the social welfare weights on non-workers has fallen relative to the social welfare weights on workers, and especially low income workers. This effect can be captured in our model simply assuming that social welfare weights change (see Section 7 for a discussion of how social welfare weights could be formed in non-utilitarian contexts). Second and related, the perception that relying on transfers generates negative externalities on children or neighbors through a “culture of welfare dependency” might have increased. Such externalities are not incorporated in our basic model but could conceivably be added. In both cases, perceptions of the public and actual facts do not necessarily align (see e.g., Bane & Ellwood, 1994 for a detailed empirical analysis).

6 Extensions

6.1 Tagging

We have assumed that ![]() depends only on earnings

depends only on earnings ![]() . In reality, the government can observe many other characteristics (denoted by vector

. In reality, the government can observe many other characteristics (denoted by vector ![]() ) also correlated with ability (and hence social welfare weights), such as gender, race, age, disability, family structure, height, etc. Hence, the government could set

) also correlated with ability (and hence social welfare weights), such as gender, race, age, disability, family structure, height, etc. Hence, the government could set ![]() and use the characteristic

and use the characteristic ![]() as a “tag” in the tax system. There are two noteworthy theoretical results.

as a “tag” in the tax system. There are two noteworthy theoretical results.

First, if characteristic ![]() is immutable then there should be full redistribution across groups with different

is immutable then there should be full redistribution across groups with different ![]() . This can be seen as follows. Suppose

. This can be seen as follows. Suppose ![]() is a binary 0–1 variable. If the average social marginal welfare weight for group 1 is higher than for group 0, a lump sum tax on group 0 funding a lump sum transfer on group 1 will increase total social welfare.

is a binary 0–1 variable. If the average social marginal welfare weight for group 1 is higher than for group 0, a lump sum tax on group 0 funding a lump sum transfer on group 1 will increase total social welfare.

Second, if characteristic ![]() is not immutable, i.e., it can be manipulated through cheating,91 then it is still desirable to make taxes depend on

is not immutable, i.e., it can be manipulated through cheating,91 then it is still desirable to make taxes depend on ![]() (in addition to

(in addition to ![]() ). At the optimum however, the redistribution across the

). At the optimum however, the redistribution across the ![]() groups will not be complete. To see this, suppose again that

groups will not be complete. To see this, suppose again that ![]() is a binary 0–1 variable and that we start from a pure income tax

is a binary 0–1 variable and that we start from a pure income tax ![]() . As

. As ![]() is correlated with ability, the average social marginal welfare weight for group 1 is different from the one for group 0. Let us assume it is higher. In that case, a small lump sum transfer from group 0 to group 1 increases social welfare, absent any behavioral response. As

is correlated with ability, the average social marginal welfare weight for group 1 is different from the one for group 0. Let us assume it is higher. In that case, a small lump sum transfer from group 0 to group 1 increases social welfare, absent any behavioral response. As ![]() is no longer immutable, this small transfer might induce some individuals to switch from group

is no longer immutable, this small transfer might induce some individuals to switch from group ![]() to group

to group ![]() . However, because we start from a unified tax system, at the margin those who switch do not create any first order fiscal cost (nor any welfare cost through the standard envelope theorem argument).92

. However, because we start from a unified tax system, at the margin those who switch do not create any first order fiscal cost (nor any welfare cost through the standard envelope theorem argument).92

Those points on tagging have been well known in the literature for decades following the analysis of Akerlof (1978) and Nichols and Zeckhauser (1982) for tagging disadvantaged groups for welfare benefits. It has received recent attention in Mankiw and Weinzierl (2010) and Weinzierl (2011) who use the examples of height and age respectively to argue that the standard utilitarian maximization framework fails to incorporate important elements of real tax policy design.

Indeed, in reality, actual tax systems depend on a very limited set of characteristics besides income. Those characteristics are primarily family structure (in particular the number of dependent children), disability status (for permanent and temporary disability programs). Hence, characteristics used reflect direct “need” (for example, the size of the household relative to income), or direct “ability-to-earn” (as is the case with disability status). To the best of our knowledge, the case for using indirect tags correlated with ability in the tax or transfer system has never been made in practice in the policy debate, implying that society does have a strong aversion for using indirect tags. We come back to this issue in Section 7 when we discuss the limits of utilitarianism.

6.2 Supplementary Commodity Taxation

The government can also implement differentiated commodity taxation in addition to nonlinear income taxes and transfers. The usual hypothesis is that commodity taxes have to be linear because of retrading (see e.g., Guesnerie, 1995, Chapter 1). The most common form of commodity taxation, value added taxes and general sales taxes, do display some variation in rates across goods, with exemptions for specific goods, such as food or housing. Such exemptions are in general justified on redistributive grounds. The government also imposes additional taxes on specific goods such as gasoline, tobacco, alcohol, airplane tickets, or motor vehicles.93 Here, we want to analyze whether it is desirable to supplement the optimal nonlinear labor income tax with differentiated linear commodity taxation.

Consider a model with ![]() consumption goods

consumption goods ![]() with pre-tax prices

with pre-tax prices ![]() . Individual

. Individual ![]() derives utility from the

derives utility from the ![]() consumption goods and earnings supply according to a utility function

consumption goods and earnings supply according to a utility function ![]() . The question we want to address is whether the government can increase social welfare using differentiated commodity taxation

. The question we want to address is whether the government can increase social welfare using differentiated commodity taxation ![]() in addition to nonlinear optimal income tax on earnings

in addition to nonlinear optimal income tax on earnings ![]() . Naturally, adding fiscal tools cannot reduce social welfare. However, Atkinson and Stiglitz (1976) demonstrated the following.

. Naturally, adding fiscal tools cannot reduce social welfare. However, Atkinson and Stiglitz (1976) demonstrated the following.

Atkinson-Stiglitz Theorem. Commodity taxes cannot increase social welfare if utility functions are weakly separable in consumption goods vs. leisure and the subutility of consumption goods is the same across individuals, i.e., ![]() with the subutility function

with the subutility function ![]() homogenous across individuals.

homogenous across individuals.

The original proof by Atkinson and Stiglitz (1976) was based on optimum conditions and not intuitive. Recently, Laroque (2005) and Kaplow (2006) have simultaneously and independently proposed a much simpler and intuitive proof that we present here.

Proof. The idea of the proof is that a tax system ![]() that includes both a nonlinear income tax and a vector of commodity taxes can be replaced by a pure income tax

that includes both a nonlinear income tax and a vector of commodity taxes can be replaced by a pure income tax ![]() that keeps all individual utilities constant and raises at least as much tax revenue.

that keeps all individual utilities constant and raises at least as much tax revenue.

Let ![]() subject to

subject to ![]() be the indirect utility of consumption goods common to all individuals. Consider replacing

be the indirect utility of consumption goods common to all individuals. Consider replacing ![]() with

with ![]() where

where ![]() is defined such that

is defined such that ![]() . Such a

. Such a ![]() naturally exists (and is unique) as

naturally exists (and is unique) as ![]() is strictly increasing in

is strictly increasing in ![]() . This implies that

. This implies that ![]() for all

for all ![]() . Hence, both the utility and the labor supply choice are unchanged for each individual

. Hence, both the utility and the labor supply choice are unchanged for each individual ![]() .

.

By definition of an indirect utility, attaining utility of consumption ![]() at price

at price ![]() costs at least

costs at least ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the consumer choice of individual

be the consumer choice of individual ![]() under the initial tax system

under the initial tax system ![]() . Individual

. Individual ![]() attains utility

attains utility ![]() when choosing

when choosing ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() . As

. As ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() , i.e., the government collects more taxes with

, i.e., the government collects more taxes with ![]() which completes the proof. QED.

which completes the proof. QED.

Intuitively, with separability and homogeneity, conditional on earnings ![]() , the consumption choices

, the consumption choices ![]() do not provide any information on ability. Hence, differentiated commodity taxes

do not provide any information on ability. Hence, differentiated commodity taxes ![]() create a tax distortion with no benefit and it is better to do all the redistribution with the individual nonlinear income tax. With the weaker linear income taxation tool, stronger assumptions on preferences, namely linear Engel curves uniform across individuals, are needed to obtain the commodity tax result (Deaton 1979).94 Intuitively, in the linear tax case, unless Engel curves are linear, commodity taxation can be useful to “non-linearize” the tax system.

create a tax distortion with no benefit and it is better to do all the redistribution with the individual nonlinear income tax. With the weaker linear income taxation tool, stronger assumptions on preferences, namely linear Engel curves uniform across individuals, are needed to obtain the commodity tax result (Deaton 1979).94 Intuitively, in the linear tax case, unless Engel curves are linear, commodity taxation can be useful to “non-linearize” the tax system.

Heterogeneous Preferences.Saez (2002b) shows that the Atkinson-Stiglitz theorem can be naturally generalized to cases with heterogeneous preferences. No tax on commodity ![]() is desirable under three assumptions: (a) conditional on income

is desirable under three assumptions: (a) conditional on income ![]() , social marginal welfare weights are uncorrelated with the levels of consumption of good

, social marginal welfare weights are uncorrelated with the levels of consumption of good ![]() , (b) conditional on income

, (b) conditional on income ![]() , the behavioral elasticities of earnings are uncorrelated with the consumption of good

, the behavioral elasticities of earnings are uncorrelated with the consumption of good ![]() , and (c) at any income level

, and (c) at any income level ![]() , the average individual variation in consumption of good

, the average individual variation in consumption of good ![]() with

with ![]() is identical to the cross-sectional variation in consumption of good

is identical to the cross-sectional variation in consumption of good ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

Assumption (a) is clearly necessary and might fail when earnings ![]() is no longer a sufficient statistic for measuring welfare. For example, if some individuals face high uninsured medical expenses due to poor health, then this assumption would not hold, and it would be desirable to subsidize health expenditures.95 However, when heterogeneity in consumption reflects heterogeneity in preferences and not in need, assumption (a) is a natural assumption.

is no longer a sufficient statistic for measuring welfare. For example, if some individuals face high uninsured medical expenses due to poor health, then this assumption would not hold, and it would be desirable to subsidize health expenditures.95 However, when heterogeneity in consumption reflects heterogeneity in preferences and not in need, assumption (a) is a natural assumption.

Assumption (b) is a technical assumption required to ensure that consumption of specific goods is not a tag for low responsiveness of labor supply to taxation. For example, if consumers of luxury cars happened to have much lower labor supply elasticities than average, it would become efficient to tax luxury cars as a way to indirectly tax more the earnings of those less responsive individuals. In practice, too little is known about the heterogeneity in labor supply across individuals to exploit such possibilities. Hence, assumption (b) is also a natural assumption.

Assumption (c) is the critical assumption. When it fails, the thought experiment to decide on whether commodity ![]() ought to be taxed is the following. Suppose high ability individuals are forced to work less and earn only as much as lower ability individuals. In that scenario, if higher ability individuals consume more of good

ought to be taxed is the following. Suppose high ability individuals are forced to work less and earn only as much as lower ability individuals. In that scenario, if higher ability individuals consume more of good ![]() than lower ability individuals, then taxing good

than lower ability individuals, then taxing good ![]() is desirable. This can happen for two reasons. First, high ability people may have a relatively higher taste for good

is desirable. This can happen for two reasons. First, high ability people may have a relatively higher taste for good ![]() (independently of income) in which case taxing good

(independently of income) in which case taxing good ![]() is a form of indirect tagging of high ability. Second, good

is a form of indirect tagging of high ability. Second, good ![]() is positively related to leisure, i.e., consumption of good

is positively related to leisure, i.e., consumption of good ![]() increases when leisure increases keeping after-tax income constant. This suggests taxing more holiday-related expenses and subsidizing work-related expenses such as child care.

increases when leisure increases keeping after-tax income constant. This suggests taxing more holiday-related expenses and subsidizing work-related expenses such as child care.

In general the Atkinson-Stiglitz assumption is a good starting place for most goods. This implies that lower or zero VAT rates on some goods for redistribution purposes is inefficient (in addition to being administratively burdensome). Under those assumptions, eliminating such preferential rates and replacing them with a more redistributive income tax and transfer system would increase social welfare.96

6.3 In-Kind Transfers

As we discussed in Section 3, the largest transfer programs are in-kind rather than cash. OECD countries in general provide universal public health care benefits and public education. They also often provide in-kind housing or nutrition benefits on a means-tested basis.

As is well known, from a rational individual perspective, if the in-kind benefit is tradable, it is equivalent to cash. Most in-kind benefits however are not tradable. In that case, recipients may be forced to overconsume the good provided in-kind and would instead prefer to receive the cash equivalent value of the in-kind transfer. Therefore, from a narrow rational individual perspective, cash transfers dominate in-kind transfers. From a social perspective, three broad lines of justification have been provided in favor of in-kind benefits.97

1. Commodity Egalitarianism: A number of goods, such as education or health care are seen as rights everybody in society is entitled to.98 Those goods are hence put in the same category as other rights that democratic governments offer to all citizens without distinction such as protection under the law, free speech, right to vote, etc. The difficulty with this view is that it does not say which level of education or health care should be seen as a right.

2. Paternalism: The government might want to impose its preferences on transfer recipients. For example, voters might support providing free shelter and free meals to the homeless but would oppose giving them cash that might be used for alcohol or tobacco consumption. In that case, recipients would rather get the cash equivalent value of the non-cash transfers they get but society’s paternalistic views prevail upon recipients’ preferences. Those arguments have been developed mostly by libertarians to criticize in-kind benefits (e.g., Milton Friedman was favorable to basic redistribution through a negative income tax cash transfer rather than in-kind benefits).

3. Individual Failures: Related, recipients could themselves realize that, if provided with only cash, they might choose too little health care, education, or retirement savings for their long-term well being, perhaps because of lack of information or self-control problems (e.g., hyperbolic discounting is an elegant way to model such self-control issues). In this case, recipients understand that non-cash benefits are in their best interest. Hence, recipients would actually support getting such non-cash benefits instead of the equivalent cash value. This type of rationalization for non-cash transfers hence differs drastically from the paternalistic view. The fact that all advanced economies systematically provide large amounts of non-cash benefits universally (retirement, health, education) through a democratic process is more consistent with the “individual failures” scenario than the “paternalism” scenario. The case of education, and especially primary education, is particularly important. Children cannot be expected to have fully forward looking rational preferences. Parents make educational choices on behalf of their children and most—but not all—parents have the best interests of their children at heart. Compulsory and free public education is a simple way for the government to ensure that all children get a minimum level of education regardless of how caring their parents are.

4. Second-best Efficiency: A number of studies have shown that, with limited information and limited policy tools, non-cash benefits can actually be desirable in a “second-best” equilibrium. In-kind benefits can be used by the government to relax the incentive constraint created by the optimal tax problem. This point was first noted by Nichols and Zeckhauser (1982) and later developed in a number of studies (see Currie & Gahvari, 2008 and Boadway, 2012, Chapter 4 for detailed surveys). Those results are closely related to the Atkinson and Stiglitz (1976) theorem presented above. If the utility function is not separable between consumption goods and leisure, then we know that commodity taxation is useful to supplement optimal nonlinear earnings taxation. By the same token, it can be shown that providing an in-kind transfer of a good complementary with work is desirable because it makes it relatively more costly for high skill people to work less. Although such “second-best” arguments have attracted the most attention in the optimal tax literature, they are second order in the public debate which focuses primarily on the other justifications we discussed above.

6.4 Family Taxation

In practice, the treatment of families raises important issues. Any tax and transfer system must make a choice on how to treat singles vs. married households and how to make taxes and transfers depend on the number of children. There is relatively little normative work on those questions, in large part because the standard utilitarian framework is not successful at capturing the key trade offs. Kaplow (2008), Chapter 8 provides a detailed review.

Couples. Any income tax system needs to decide how to treat couples vs. single individuals. As couples typically share resources, welfare is best measured by family income rather than individual income. There are two main treatments of the family in actual tax (or transfer) systems. (a) The individual system where every person is taxed separately based on her individual income. In that case, couples are treated as two separate individuals. As a result, an individual system does not impose any tax or subsidy on marriage as tax liability is independent of living arrangements. At the same time, it taxes in the same way a person married to a wealthy spouse vs. a person married to a spouse with no income. (b) The family system where the income tax is based on total family income, i.e., the sum of the income of both spouses in case of married couples. The family system can naturally modulate the tax burden based on total family resources, which best measures welfare under complete sharing within families. However and as a result, a family tax system with progressive tax brackets cannot be neutral with respect to living arrangements, creating either a marriage tax or a marriage subsidy. Under progressive taxation, if the tax brackets for married couples are the same as for individuals, the family system typically creates a marriage tax. If the tax brackets for married couple are twice as wide as for individuals, the family system typically creates a marriage subsidy.99

Hence and as is well known, it is impossible to have a tax system that simultaneously meets three desirable properties: (1) the tax burden is based on family income, (2) the tax system is marriage neutral, and (3) the tax system is progressive (i.e., the tax system is not strictly linear). Although those properties clearly matter in the public debate, it is not possible to formalize their trade off within the traditional utilitarian framework as the utilitarian principle cannot put a weight on the marriage neutrality principle.

If marriage responds strongly to any tax penalty or subsidy, it is better to reduce the marriage penalty/subsidy and move toward an individualized system. This issue might be particularly important in countries (such as Scandinavian countries for example), where many couples cohabit without being formally married and as it is difficult (and intrusive) for the government to observe (and monitor) cohabitation status.

Traditionally, the labor supply of secondary earners—typically married women—has been found to be more elastic than the labor supply of primary earners—typically married men (see Blundell & MaCurdy, 1999 for a survey). Under the standard Ramsey taxation logic, this implies that it is more efficient to tax secondary earners less (Boskin & Sheshinski, 1983). If the tax system is progressive, this goal is naturally achieved under an individual-based system as secondary earners are taxed on their sole earnings. Note however that the difference in labor supply elasticities between primary and secondary earners has likely declined over time as more and more married women work (Blau & Kahn, 2007).

In practice, most OECD countries have switched from family based to individual-based income taxation. In contrast, transfer systems remain based on family income. It is therefore acceptable to the public that a spouse with modest earnings would face a low tax rate, no matter how high the earnings of her/his spouse are.100 In contrast, it appears unacceptable to the public that a spouse with modest earnings should receive means-tested transfers if the earnings of his or her spouse are high. A potential explanation could be framing effects as direct transfers might be more salient than an equivalent reduction in taxes. Kleven, Kreiner, and Saez (2009b) offer a potential explanation in a standard utilitarian model with labor supply where they show that the optimal joint tax system is to have transfers for non-working spouses (or equivalently taxes on secondary earnings) that decrease with primary earnings. The intuition is the following. With concave utilities, the presence of secondary earnings make a bigger difference in welfare when primary earnings are low than when primary earnings are large. Hence, it is more valuable to compensate one earner couples (relative to two earner couples) when primary earnings are low. This translates into an implicit tax on secondary earnings that decreases with primary earnings. Such negative jointness in the tax system is approximately achieved by having family based means-tested transfers along with individually based income taxation.

Children. Most tax and transfer systems offer tax reductions for children or increases in benefits for children. The rationale for such transfers is simply that, conditional on income ![]() , families with more children are more in need of transfers and have less ability to pay taxes. The interesting question that arises is how the net transfer (additional child benefits or reduction in taxes) per additional child should vary with income

, families with more children are more in need of transfers and have less ability to pay taxes. The interesting question that arises is how the net transfer (additional child benefits or reduction in taxes) per additional child should vary with income ![]() . On the one hand, the need for children related transfers is highest for families with very small incomes. On the other hand, the cost of children is higher for families with higher incomes particularly when parents work and need to purchase childcare.

. On the one hand, the need for children related transfers is highest for families with very small incomes. On the other hand, the cost of children is higher for families with higher incomes particularly when parents work and need to purchase childcare.

Actual tax and transfers do seem to take both considerations into account. Means-tested transfers tend to offer child benefits that are phased-out with earnings. Income taxes tend to offer child benefits that increase with income for two reasons. First, the lowest income earners do not have taxable income and hence do not benefit from child-related tax reductions. Second, child-related tax reductions are typically a fixed deduction from taxable income which is more valuable in upper income tax brackets. Hence, the level of child benefits tends to be U-shaped as a function of earnings. Two important qualifications should be made.

First, as mentioned in Section 5.3.3, a number of countries have introduced in-work benefits that are tied to work and presence of children. This tends to make child benefits less decreasing with income at the low income end. In the United States, because of the large EITC and child tax credits and small traditional means-tested transfers, the benefit per child is actually increasing with family earnings at the bottom. Second, another large child benefit often subsidized or government provided is pre-school child care (infant child care, kindergarten starting at age 2 or 3, etc.). Such child care benefits are quantitatively large and most valuable when both parents work or for single working parents. Hence, economically, they are a form of in-kind in-work benefit which also promotes labor force participation (see OECD, 2006, chap. 4, Figure 4.1, p.129 for an empirical analysis). It is perhaps not a coincidence that cash in-work benefits for children are highest in the US and the UK, countries which provide minimal child care public benefits. Understanding in that context whether a cash transfer or an in-kind child care benefit is preferable is an interesting research question that has received little attention.

Child-related benefits raise two additional interesting issues.

First, families do not take decisions as a single unit (Chiappori, 1988). Interestingly, in the case of children, cash transfers to mothers (or grandmothers) have larger impacts on children’s consumption than transfers to fathers. This has been shown in the UK context (Lundberg, Pollak, & Wales, 1997) when the administration of child tax benefits was changed from a reduction in tax withholdings of parents (often the father) to a direct check to the mother. Similar effects have been documented in the case of cash benefits for the elderly in South Africa (Duflo, 2003). This evidence suggests that in-kind benefits (such as child care or pre-school) might be preferable if the goal is to ensure that resources go toward children. As mentioned above, primary education is again the most important example of in-kind benefits designed so that children benefit regardless of how caring parents are.

Second, child benefits might promote fertility. A large empirical literature has found that child benefits have sometimes positive but in general quite modest effects on fertility (see Gauthier, 2007 for a survey). There can be externalities (both positive and negative) associated with children. For example, there can be congestion effects (such as global warming) associated with larger populations. Alternatively, declines in populations can have adverse effects on sustainability of pay-as-you-go pension arrangements. Such externalities should be factored into discussions of optimal child benefits.

6.5 Relative Income Concerns