5

Values and their influence on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing

Values and their impact on behaviors and wellbeing outcomes have been a fruitful area of research in the social sciences. During the 1960s and 1970s, Rokeach (1968, 1973) asserted that values was an important component of the research on culture, society, social attitudes and behavior. In his research on lifestyles, Mitchell (1983, p. vii) defined values as “the whole constellation of a person’s attitudes, beliefs, opinions, hopes, fears, prejudices, needs, desires, and aspirations that, taken together, govern how one behaves.” Values premised on religious beliefs also have a significant influence on individuals and communities.

Many country-level and region-level studies (e.g., The European Social Survey and our QOL Surveys in Singapore) have incorporated measures on values in their data collection. One of the largest studies related to values is the World Values Survey, a global network of social scientists that has been studying changing values and their impact on social and political life since 1981. To date, more than 400 publications using the World Values Survey (WVS) have contributed substantially to our understanding of how value systems influence various aspects of our lives. Similar to previous waves, the questionnaire for the most recent WVS Wave 7 data collection comprises 290 questions and measures “cultural values, attitudes and beliefs towards gender, family, and religion, attitudes and experience of poverty, education, health, and security, social tolerance and trust, attitudes towards multilateral institutions, cultural differences and similarities between regions and societies” and includes new topics such as “justice, moral principles, corruption, accountability and risk, migration, national security and global governance.”

Researchers have conceptualized and developed various measures on values for use in these large-scale surveys. For the 2016 QOL Survey, we used the List of Values (Kahle 1983, 1996) and the Portrait Values Questionnaire (Schwartz 2007). The List of Values (LOV) measure has been used in many contexts and “a large body of research has documented its reliability and validity” (Stockard et al. 2014, p. 230). The Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) (Schwartz 2007) is also an established scale that has been validated and widely used (e.g., in the World Values Survey and many other studies).

In this chapter, we assess the importance of certain personal values to Singaporeans and specific demographic groups by age, gender, education, monthly household income and marital status. In addition to tracking changes in the LOV over time, we also conduct regression analyses to examine the impact of the values in the LOV and the PVQ on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing.

List of values

In this section, we examine how Singaporeans felt about some personal values using the LOV. There are nine items in this measure: (1) Sense of Belonging, (2) Security, (3) Self-respect, (4) Warm Relationships with Others, (5) Fun and Enjoyment in Life, (6) Being Well-respected, (7) Sense of Accomplishment, (8) Self-fulfillment, and (9) Excitement (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 List of values

| Value | Description |

|

|

|

| Sense of belonging | To be accepted and needed by your family, friends, and community. |

| Security | To be safe and protected from misfortune and attack. |

| Self-respect | To be proud of yourself and confident with who you are. |

| Warm relationships with others | To have close companionships and intimate friendships. |

| Fun and enjoyment in life Being well-respected | To lead a pleasurable life. To be admired by others and to receive recognition. |

| Sense of accomplishment Self-fulfillment | To succeed at whatever you do. To find peace of mind and to make the best use of your talents. |

| Excitement | To experience stimulation and thrills. |

Source: Kahle (1996)

In Singapore, the LOV was used in nationwide surveys conducted in 1996, 2001, 2011 and 2016. In all four surveys, respondents were asked to rate the nine values in the LOV on a 6-point scale (“1 = not important at all”; “6 = very important”). The mean score of each value was used to rank the values from the most important to the least. The 1996 survey was conducted by a reputable market research agency, using a stratified random sampling approach, resulting in a total of 1525 valid responses. The sample was found to be biased toward younger and more educated individuals and underrepresented older and less educated individuals. To achieve representativeness of the national population, the sample was weighted by age and education using the 1995 Census data (see Kau et al. 1998). Hence for this analysis, we used the weighted sample for 1996 data. The 2001 survey was similarly conducted by a professional research agency using the same stratified random sampling approach. The final sample of 1500 was found to be representative of the national population (see Kau et al. 2004). The 2011 and 2016 QOL Surveys were conducted by the same agency that conducted the 2001 survey, and the final samples of 1500 and 1503 (respectively) were similarly found to be representative of the national population. In the 1996 and 2001 surveys, the LOV was administered to both Singapore citizens and Permanent Residents, whereas in the 2011 and 2016 QOL Surveys, only Singapore citizens responded to the survey. Hence, for comparison, only responses of Singapore citizens were considered in the analyses across demographic groups. The nationally representative samples of the 1996 (weighted), 2001, 2011 and 2016 surveys enabled us to do the comparisons across time.

General comparisons for choices and ranks

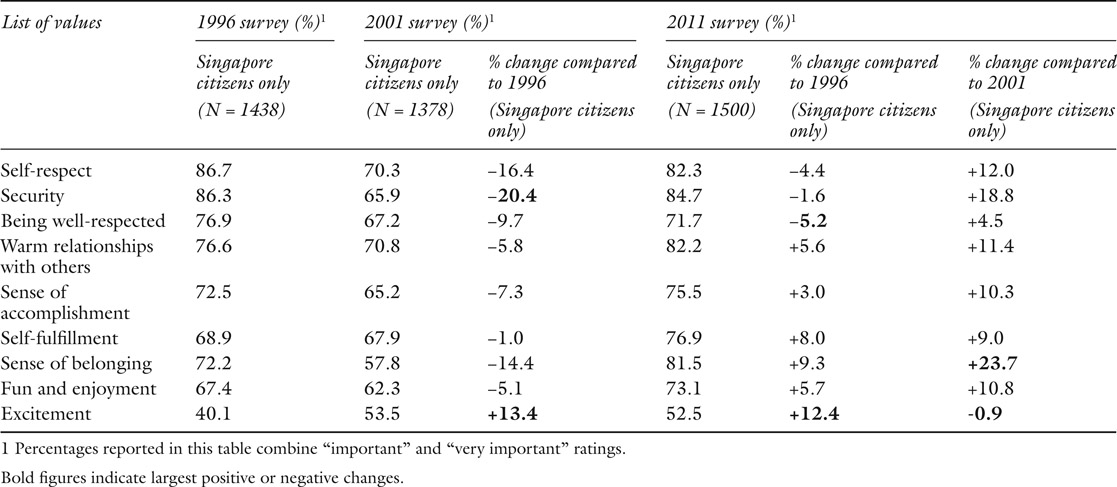

In Table 5.2a and Table 5.2b, we report the percentages of respondents who picked a particular value as “important” or “very important.” As shown in the tables, there were changes in the choice of important values over the past two decades. However, no definite positive or negative trend was observed. Comparing 2001 with 1996 data (see Table 5.2a), all but one value declined in importance, with Security having the largest drop in importance. The only value that had a positive trend was Excitement. Comparing 2011 with 1996 data (see Table 5.2a), the upswing for Excitement continued, while the negative trend for some values was reversed. For instance, Warm Relationships with Others, Sense of Accomplishment, Self-fulfillment, Sense of Belonging, and Fun and Enjoyment achieved increases in importance. Comparing 2011 data with 2001 data revealed a different trend (see Table 5.2a). All values showed a positive improvement in importance except for Excitement, which showed a decline in importance. Sense of Belonging registered the largest percentage increase in importance, followed by Security.

Comparing the 2016 data with those of 1996, 2001 and 2011 data (see Table 5.2b), no definite positive or negative trend was observed, but some changes were notable. Comparing 2016 and 1996 data, we noticed that Being Well-respected had been given less emphasis (5.6 percent decrease in responses that the value is considered “important” and “very important”) over the past 20 years, while Self-fulfillment has been given more consideration (11 percent increase). Comparing 2016 against 2001 data, it appeared that Security had been given much greater emphasis (25 percent increase in responses that the value is “important” and “very important”), while Excitement had been given lesser emphasis (8.4 percent decrease). Comparing 2016 against 2011 data, Security continued to be given more importance (6.2 percent increase), while Excitement continued its decline in importance (7.4 percent decrease).

Despite the absence of significant trends in the choice of important values over the past two decades, the rankings of the values’ importance means did reveal some interesting insights (see Table 5.3). A higher mean indicates that a particular value is considered more important. The top three values have seen

Table 5.2a List of values for the 1996, 2001 and 2011 QOL Surveys

Table 5.2b List of values for the 2016 QOL Survey

| List of values |

2016 survey (%)

1

|

|||

|

Singapore citizens only (N = 1503) |

% Change compared to 1996 (Singapore citizens only) |

% Change compared to 2001 (Singapore citizens only) |

% Change compared to 2011 (Singapore citizens only) |

|

|

|

||||

| Self-respect | 85.8 | −0.9 | +15.5 | +3.5 |

| Security | 90.9 | +4.6 | +25 | +6.2 |

| Being well-respected | 71.3 | −5.6 | +4.1 | −0.4 |

| Warm relationships with others | 84.3 | +7.7 | +13.5 | +2.1 |

| Sense of Accomplishment | 74.1 | +1.6 | +8.9 | −1.4 |

| Self-fulfillment | 79.9 | +11 | +12 | +3 |

| Sense of belonging | 82.1 | +9.9 | +24.3 | +0.6 |

| Fun and enjoyment | 72.1 | +4.7 | +9.8 | −1 |

| Excitement | 45.1 | +5 | −8.4 | −7.4 |

1 Percentages reported in this table combine “important” and “very important” ratings.

Bold figures indicate largest positive or negative changes.

Table 5.3 List of values (ranking of importance means)

| List of values | 1996 (rank) | 2001 (rank) | 2011 (rank) | 2016 (rank) |

|

|

||||

| Self-respect | 5.40 (1) | 4.83 (1) | 5.03 (2) | 5.06 (2) |

| Security | 5.28 (2) | 4.72 (5) | 5.09 (1) | 5.19 (1) |

| Being well-respected | 5.10 (3) | 4.77 (3) | 4.88 (7) | 4.75 (8) |

| Warm relationships with others | 5.08 (4) | 4.83 (1) | 4.99 (3) | 5.02 (3) |

| Sense of accomplishment | 4.94 (5) | 4.70 (6) | 4.90 (6) | 4.82 (6) |

| Self-fulfillment | 4.83 (6) | 4.76 (4) | 4.93 (5) | 4.93 (5) |

| Sense of belonging | 4.94 (7) | 4.60 (8) | 4.98 (4) | 4.97 (4) |

| Fun and enjoyment | 4.79 (8) | 4.65 (7) | 4.85 (8) | 4.80 (7) |

| Excitement | 4.01 (9) | 4.49 (9) | 4.44 (9) | 4.14 (9) |

Note: Means of scale ranging from “1 = Not important at all” to “6 = Very important.”

some changes over the past 20 years. In 1996, the top three values were Self-respect, Security and Being Well-respected. However, five years later (2001), Self-respect and Warm Relationships with Others both became top ranked, followed by Being Well-respected, while Security was ranked 5th. Ten years later in 2011, Security became the most important value, followed by Self-respect and Warm Relationships with Others. Being Well-respected, which was ranked 3rd in 1996 and 2001, became less important and ranked 7th out of nine values. Five years later in 2016, the top two values remained the same as those in 2011, but Being Well-respected further declined to being ranked 8th out of nine values. Another noticeable change in ranking over the past 20 years is that Sense of Belonging has improved in rank, from being ranked 7th and 8th in 1996 and 2001 respectively, to 4th in 2011 and 2016. Some consistency is also being observed in Singaporeans’ ranking of the importance of the nine values, with Fun and Enjoyment being ranked either 7th or 8th, and Excitement always ranked last over the past 20 years.

Using a translated version of the LOV, Grunert and Scherhorn’s (1990) study in West Germany found that Sense of Belonging was rated highest in importance among the 1008 subjects surveyed, followed closely by Security. Self-fulfillment and Excitement were ranked second to last and last in importance. Their results were similar to our 1996 survey as far as the lowest-ranked value of Excitement, lower-ranked (6th) value of Self-fulfillment and 2nd-ranked value of Security were concerned, except for Sense of Belonging which was ranked 7th by Singaporeans.

In their study of changes in social values in the United States over 30 years from 1976 to 2007, Gurel-Atay et al. (2010) found that values such as Self-respect, Fun and Enjoyment, and Excitement showed the greatest gain in importance, with Self-respect as the most important value in 2007. Warm Relationships with Others and Self-fulfillment were close seconds in order of importance. The values of Security and Sense of Belonging demonstrated the most decline in importance. They also found that there was a reverse pattern in importance placed on different values; more important values in 1986 were perceived as less important in 2007. Their results contrasted with what we have found in the three surveys between the years 1996 and 2011 (Tambyah and Tan 2013). In Singapore, Fun and Enjoyment and Excitement have consistently been ranked last or second to last among the nine values over the three periods, while Security and Sense of Belonging have risen to top positions over this period. However, like the Americans, Singaporeans valued Self-respect, Warm Relationships with Others and Self-fulfillment over the years 1996 to 2011.

Sources of individual differences in LOV

Age

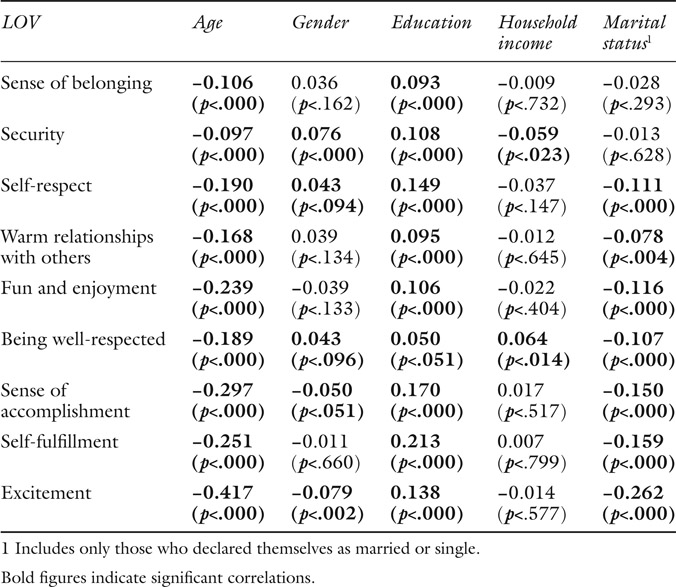

As shown in the second column of Table 5.4, age had a negative and significant correlation with all nine values in LOV, implying that older Singaporeans regarded these values as less important compared to their younger counterparts. Our results about older Singaporeans contrasted with findings from research on LOV of older persons in other parts of the world, some of which examined both chronological age as well as cognitive or self-perceived age. For instance, in a study involving 356 Australian seniors ranging in age between 56 and 93 years, Cleaver and Muller (2002) found that those who had younger self-perceived age placed more importance on Fun and Enjoyment, while those who had older self-perceived age placed greater importance on Security.

Table 5.4 Correlations of LOV with age, gender, education, income and marital status (2016)

In a study involving 650 older consumers (above 50 years of age) in the United Kingdom, Sudbury and Simcock (2009) found that the most important value to older consumers was Self-respect, followed by Security, Warm Relationships with Others, and a Sense of Accomplishment, with Being Well-respected the least important value. However, in terms of self-reported cognitive age, Sudbury and Simcock (2009) found that while Self-respect is of greatest importance to the older cognitive age groups (40s, 50s and 60s), the youngest cognitive age group (30s) placed the greatest importance on Warm Relationships with Others. Strong negative correlations were found between cognitive age and Warm Relationships with Others, Fun and Enjoyment, and Self-fulfillment. Strong positive correlations were found between cognitive age and Security, Sense of Accomplishment, and Sense of Belonging.

Gender

As far as Sense of Belonging, Warm Relationships with Others, Fun and Enjoyment, and Self-fulfillment are concerned, there were no gender differences (see Table 5.4 third column). However, female Singaporeans tended to hold values such as Security, Self-respect and Being Well-respected as more important than male Singaporeans, whereas male Singaporeans placed more emphasis on values like Sense of Accomplishment and Excitement. We have not found any extant studies that examined gender differences in LOV.

Education

Education had an unanimous positive and significant correlation with all nine values in LOV (see fourth column in Table 5.4), implying that as Singaporeans became more educated, they placed more importance on these nine values. We have not found any extant studies that examined differences between LOV and education.

Income

Household income had a negative and significant relationship with Security (see fifth column in Table 5.4) implying that Singaporeans tended to place less importance on Security as their income increased. However, income had a positive and significant relationship with Being Well-respected, implying that Singaporeans tended to value Being Well-respected more as their income increased. We have not found any extant studies that examined differences in LOV for income.

Marital Status

Marital status had a negative and significant relationship with Self-respect, Warm Relationships with Others, Fun and Enjoyment, Being Well-respected, Sense of Accomplishment, Self-fulfillment and Excitement (see sixth column in Table 5.4). This means that singles were significantly better off than married Singaporeans in these areas. We have not found any extant studies that examined differences in LOV for marital status.

Impact of LOV on subjective wellbeing

To assess the impact of LOV on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing, we conducted a series of regression analyses, using the nine LOV items as independent variables. The subjective wellbeing indicators selected as dependent variables in the regression analyses are happiness (“All things considered, would you say that you are happy these days?” on a 5-point scale of “1 = very unhappy” to “5 = very happy”), enjoyment (“How often do you feel you are really enjoying life these days?” on a 4-point response scale of “1 = never” to “4 = often”), achievement (“How much do you feel you are accomplishing what you want out of life?” on a 4-point scale of “1 = none” to “4 = a great deal”), level of control (“How much control do you feel you have over important aspects of your life?” on a 4-point scale of “1 = none” to “4 = a great deal”), sense of purpose (“All things considered, how much do you feel you have a sense of purpose in your life?” on a 4-point scale of “1 = none” to “4 = a great deal”), satisfaction with life (factor scores for responses to five statements: “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal,” “The conditions of my life are excellent,” “I am satisfied with my life,” “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life” and “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing” on a 6-point scale “1 = strongly disagree” to “6 = strongly agree”), satisfaction with overall quality of life (“Your overall quality of life” on a scale of “1 = very dissatisfied,” “2 = dissatisfied,” “3 = somewhat dissatisfied,” 4 for “somewhat satisfied,” “5 = satisfied” and “6 = very satisfied”) and satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore (on a scale of “1 = very dissatisfied,” “2 = dissatisfied,” “3 = somewhat dissatisfied,” “4 = somewhat satisfied,” “5 = satisfied” and “6 = very satisfied”).

LOV and happiness

As shown in the second column of Table 5.5, out of the nine values, only Sense of Belonging had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ happiness.

LOV and enjoyment

Sense of Belonging, Self-respect, and Fun and Enjoyment were the three LOV items that had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ enjoyment level, while Being Well-respected had a negative and significant impact, as shown in the third column of Table 5.5.

LOV and achievement

Table 5.5 (fourth column) shows that Sense of Belonging, Fun and Enjoyment, and Self-fulfillment had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ sense of achievement, while Excitement exerted a negative and significant impact.

LOV and control

For a sense of control over important aspects of Singaporeans’ life, Security, Fun and Enjoyment, and Self-fulfillment played positive and significant roles, as shown in the fifth column of Table 5.5, while Excitement significantly took away something from this impact.

LOV and purpose

As shown in the sixth column six of Table 5.5, Sense of Belonging and Self-Fulfillment contributed positively and significantly toward Singaporeans’ sense of purpose in life, but Being Well-respected had a negative significant impact.

Table 5.5 Impact of LOV on happiness, enjoyment, achievement, control and purpose

LOV and satisfaction with life

Having a Sense of Belonging, Warm Relationships with Others, and Being Well-respected had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ satisfaction with life, but Sense of Accomplishment had a significantly negative impact, as shown in Table 5.6 (second column).

LOV and satisfaction with overall quality of life

Sense of Belonging, Warm Relationships with Others, and Fun and Enjoyment had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ satisfaction with their overall quality of life, as shown in Table 5.6 (third column).

Table 5.6 Impact of LOV on satisfaction with life, satisfaction with overall quality of life and satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore

| LOV items |

Unstandardized beta

|

||

| Satisfaction with life1 | Satisfaction with overall quality of life 2 | Satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore 3 | |

|

|

|||

| (Constant) | 2.576 (p<.000) | 2.860 (p<.000) | 2.777 (p<.000) |

| Sense of belonging | 0.160 (p<.000) | 0.129 (p<.000) | 0.118 (p<.001) |

| Security | 0.007 (p<.871) | 0.038 (p<.314) | 0.081 (p<.040) |

| Self-respect | -0.015 (p<.748) | 0.004 (p<.926) | 0.041 (p<.327) |

| Warm relationships with others | 0.086 (p<.046) | 0.098 (p<.008) | 0.089 (p<.022) |

| Fun and enjoyment | 0.060 (p<.065) | 0.085 (p<.003) | 0.004 (p<.899) |

| Being well-respected | 0.110 (p<.001) | 0.044 (p<.129) | 0.086 (p<.005) |

| Sense of accomplishment | -0.113 (p<.004) | -0.030 (p<.379) | -0.010 (p<.784) |

| Self-fulfillment | 0.061 (p<.145) | 0.028 (p<.437) | -0.018 (p<.642) |

| Excitement | -0.011 (p<.592) | -0.024 (p<.184) | -0.019 (p<.321) |

LOV and satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore

Finally, Sense of Belonging, Security, Warm Relationships with Others, and Being Well-respected had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore, as shown in Table 5.6 (fourth column).

Schwartz’s Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ)

For the 2016 QOL Survey, we provided Singaporeans with 21 descriptions of different individuals and asked the respondents to indicate to what extent they are like the persons described (“1 = not like me at all” to “6 = very much like me”). These 21 statements were from the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ), which is a shorter version of the original Schwartz Values Survey (SVS) that had 56 or 57 items (Schwartz 2012). The PVQ was used in the European Social Survey (ESS) to measure basic human values in 20 countries in Europe (Schwartz 2007). Each of the 21 statements was indexed to ten basic values identified by Schwartz (2007) as Self-direction, Stimulation, Hedonism, Achievement, Power, Security, Conformity, Tradition, Benevolence and Universalism. The basic value of Self-direction was measured by one statement relating to being creative and doing things in his or her own ways and by another statement relating to being free and being independent. Stimulation was measured by one statement relating to seeking and doing new/different things in life and by another statement relating to being adventurous and risk seeking. Hedonism was measured by two statements relating to self-indulgence in fun and pleasure. Achievement was measured by two statements relating to showing abilities and being admired and being successful and recognized for his or her achievement. Power was measured by two statements relating to having wealth and authority. Security was measured by two statements relating to living in a secure and safe environment and national security. Conformity was measured by two statements relating to being obedient and exercising self-discipline. Tradition was measured by two statements relating to respect for tradition, and being humble and modest. Benevolence was measured by two statements relating to being helpful and loyal. And Universalism was measured by three statements relating to being broadminded, believing in equality and caring for nature.

A factor analysis of the 21 statements showed that there were four factors (known as Higher Order Values) with the following dimensions: Openness (or Openness to change), Conservation, Self-transcendence and Self-enhancement (Schwartz 2007). The Openness dimension includes the basic values of Stimulation, Self-direction, and Hedonism. The Conservation dimension includes the basic values of Conformity, Tradition and Security. The Self-transcendence dimension includes the basic values of universalism and benevolence. The Self-enhancement dimension includes the basic values of Achievement and Power.

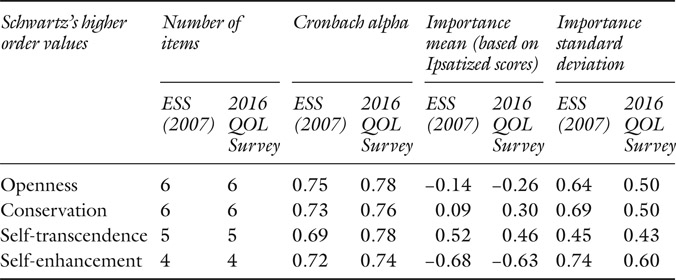

Table 5.7 Cronbach alpha reliabilities, means and standard deviations of the four Higher Order Values for the 2016 QOL Survey and the European Social Survey

Table 5.7 shows the factor analysis results for the four Higher Order Values for the 2016 QOL Survey compared to results for the ESS as reported in Schwartz (2007). As shown in Table 5.7, the reliability ratios (Cronbach alphas) for the Higher Order Values of the Singapore sample (2016 QOL Survey) were higher than those for the ESS sample.

Value priorities

The importance means for the 2016 QOL sample are in line with the ESS sample, as shown in Table 5.7. The means for the ESS sample show that the European countries gave high priority to Self-transcendence and low priority to Self-enhancement (Schwartz 2007). Singaporeans also gave higher priority to Self-transcendence and to Conservation, which the Europeans gave lower priority to (Schwartz 2007). Unlike the Europeans, Singaporeans gave even lower priority to Openness (−0.26 versus −0.14), although Singaporeans gave almost as low a priority to Self-enhancement as the Europeans (−0.63 versus −0.68).

Sources of individual differences in Higher Order Values

Age

Researchers have posited that, as people age, “they tend to become more embedded in social networks, more committed to habitual patterns, and less exposed to arousing and exciting changes and challenges” (Glen 1974; Tyler and Schuler 1991). Thus it was implied that Conservation values should increase with age, while Openness should decrease (Schwartz 2007). This was supported by Doran and Littrell’s (2013) online survey of 440 White, non-Hispanic American adults, which found that older subjects reported significantly lower means for Stimulation and Hedonism (values in the Openness factor).

Researchers also found that once people started having families of their own and achieving good positions in their careers, “they tend to become less preoccupied with their own strivings and more concerned with the welfare of others” (Veroff et al. 1984). Thus it was implied that Self-transcendence values should increase with age and Self-enhancement values should decrease (Schwartz 2007). The 20 European countries in the ESS showed that “all the observed correlations confirm the expected associations and support the probable processes of influence” (Schwartz 2007, p. 180). This was also supported in the American sample in Doran and Littrell (2013). They found that older participants had significantly lower means for achievement (a value in the Self-enhancement factor).

As shown in Table 5.8, age was negatively correlated with Openness and Self-enhancement and positively correlated with Conservation for Singaporeans, similar to the ESS sample. However, unlike the Europeans, age was negatively correlated with Self-transcendence.

Gender

Although many theories of gender differences led researchers to postulate that “men emphasize ‘agentic-instrumental’ values such as power and achievement, while females emphasize ‘expressive-communal’ values such as benevolence and universalism” (Schwartz and Rubel 2005), most theories expect the differences to be small (Schwartz 2007). In the ESS, Schwartz (2007) found this expectation held true for gender. Doran and Littrell (2013) found that females had significantly higher-value means for universalism and benevolence (the Self-transcendence factor) and males had significantly higher means for Self-direction and Stimulation (the Openness factor) and Achievement and Power (the Self-enhancement factor).

In Singapore, the gender effect was not significant for the values of Self-transcendence and Conservation (see Table 5.8), while Openness and Self-enhancement were negatively correlated with gender (meaning that males emphasized these values more than females). Although Conservation had a positive relationship with gender in Singapore (meaning that females placed more emphasis on this value than males), the relationship was not statistically significant.

Education

Although educational experiences can increase openness to nonroutine ideas and activities central to Stimulation values, they can challenge an unquestioning acceptance of prevailing norms, expectations, and traditions, thereby undermining Conformity and Tradition. The increasing competencies to cope with life that people acquire through education may also reduce the importance of Security values (Schwartz 2007). The ESS showed a positive relationship between years of education and Openness values and a negative association with Conservation values (Schwartz 2007). Additionally, Schwartz (2007) found that “education was positively associated with achievement values,” while this linear relationship did not apply to Universalism. The positive correlation applied only to postsecondary education and was substantially higher for university educated people. In America, Doran and Littrell (2013) found that the more highly educated subjects in their study had significantly lower means for Conformity, Tradition, Security (values in the Conservation factor) and Hedonism (a value in the Openness factor). As shown in Table 5.8, education was positively correlated with Openness, Self-enhancement and Self-transcendence in Singapore, similar to what was found for the European countries. Although Conservation had a negative relationship with education in Singapore, this relationship was not statistically significant.

Income

According to Schwartz (2007), higher income was expected to promote the prioritization of the Stimulation, Self-direction, Hedonism and Achievement values over the Security, Conformity and Tradition values. In his analysis of the 20 countries in the ESS, Schwartz (2007) found that income contributed to higher Stimulation, Hedonism and Self-direction (Openness factor) and to Achievement and Power (Self-enhancement factor). In America, Doran and Littrell (2013) found that higher-income subjects in their study had significantly higher-value means for Power (Self-enhancement factor) and Security (Conservation factor) but significantly lower means for Universalism (Self-transcendence factor).

Table 5.8 Correlations of the four Higher Order Values with age, gender, education, income and marital status (2016)

Similar to the case of the European countries, income had a positive relationship with Openness in Singapore (see Table 5.8). Like the European countries and America, income had a positive relationship with Self-enhancement in Singapore. However, unlike the case of Europe and America, income had a positive relationship with Self-transcendence, and as in the case of America, income had a positive relationship with Conservation in Singapore, although the relationship was not statistically significant.

Marital status

In the case of Singapore, marital status had a negative and significant relationship with Openness, Self-enhancement and Self-transcendence (see sixth column of Table 5.8). However, marital status had a positive and significant relationship with Conservatism. This means that married people placed less emphasis on Openness, Self-enhancement, and Self-transcendence but more emphasis on Conservatism compared to the singles. Note that we have not found any extant studies that examined the relationship between the Higher Order Values and marital status.

Impact of Schwartz’s Higher Order Values on subjective wellbeing

To assess the impact of Schwartz’s Higher Order Values on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing, we conducted a series of regression analyses, using the factor scores for the four factors forming the four Higher Order Values as independent variables. The subjective wellbeing indicators selected as dependent variables in the regression analyses are the same as those for the Personal Values analyses: happiness, enjoyment, accomplishment, control, purpose, satisfaction with life, satisfaction with overall quality of life and satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore.

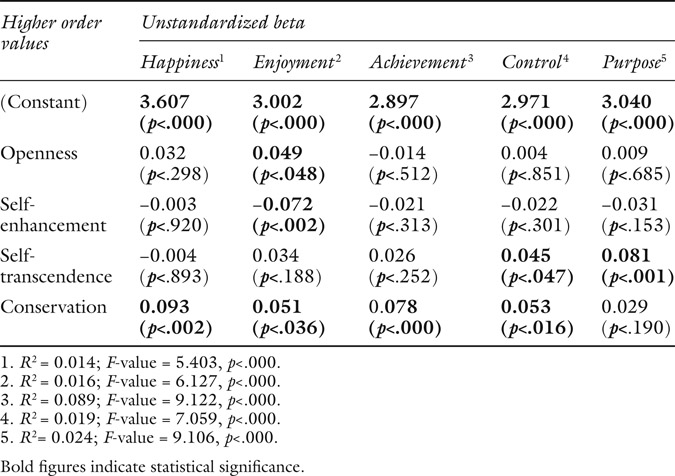

Impact of Higher Order Values on happiness, enjoyment, achievement, control and purpose

As shown in the second column of Table 5.9, of the four Higher Order Values, only Conservation had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ Happiness. Openness and Conservation had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ Enjoyment, while Self-enhancement had a negative and significant impact (Table 5.9, third column). Conservation had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ Achievement (see Table 5.9, fourth column).

Self-transcendence and Conservation had a significant and positive impact on Control (see Table 5.9, fifth column), while only Self-transcendence had a positive and significant impact on Purpose (see Table 5.9, sixth column).

Table 5.9 Higher Order Values and happiness, enjoyment, achievement, control and purpose

Impact of Higher Order Values on satisfaction with life, satisfaction with overall quality of life and satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore

For satisfaction with life, only Conservation had a positive and significant impact (see Table 5.10 second column). For satisfaction with overall quality of life, Self-transcendence and Conservation had a positive and significant impact (see Table 5.10, third column). Finally, for satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore, Openness had a negative and significant impact, while Self-transcendence and Conservation had a positive and significant impact (see Table 5.10 fourth column).

Conclusion

Table 5.10 Higher Order Values and satisfaction with life, satisfaction with overall quality of life and satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore

| Higher order values |

Unstandardized Beta

|

||

| Satisfaction with life1 | Satisfaction with overall quality of life2 | Satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore3 | |

|

|

|||

| (Constant) | 4.287 (p<.000) | 4.725 (p<.000) | 4.657 (p<.000) |

| Openness | 0.026 (p<.361) | 0.027 (p<.296) | −0.074 (p<.006) |

| Self-enhancement | 0.002 (p<.932) | −0.035 (p<.151) | 0.005 (p<.856) |

| Self-transcendence | −0.005 (p<.879) | 0.056 (p<.035) | 0.075 (p<.007) |

| Conservation | 0.222 (p<.000) | 0.102 (p<.000) | 0.087 (p<.001) |

Our investigation of Singaporeans’ ranking of the importance of the nine values in the LOV showed that there were no significant shifts in value importance over the past two decades (1996 to 2016) compared to what was found in America (e.g., Gurel-Atay et al.’s (2010) study of Americans for the period 1976 to 2007). In terms of top-ranked and lowest-ranked values, it was interesting to note that, unlike their Western counterparts, Singaporeans had consistently placed lowest importance on values like Fun and Enjoyment, and Excitement. The lack of emphasis on these values seemed to reflect the Confucian nature of Singaporean society where diligence takes precedence over play in work attitudes. Singapore is one of the societies belonging geographically to “Confucian Asia,” a region infused with the norms and values taught by Confucius and Mencius (Slingerland 2003).

In 2016, age and education were the most important sources of individual differences across all nine values in LOV (Sense of Belonging, Security, Self-respect, Warm Relationships with Others, Fun and Enjoyment, Being Well-respected, Sense of Accomplishment, Self-fulfillment, and Excitement), followed closely by marital status, which had differential impacts on seven values (Self-respect, Warm Relationships with Others, Fun and Enjoyment, Being Well-respected, Sense of Accomplishment, Self-fulfillment, Excitement). Household incomes had the least impact, only contributing to individual differences on the value of Security.

We have shown that older Singaporeans (in terms of chronological age) did not share the same value importance as their younger counterparts. It would be interesting if we had also examined cognitive or self-perceived age besides chronological age because some of the research in the West has shown that using cognitive age could provide valuable insights (Sudbury and Simcock 2009). More insights could be drawn if there were cross-country studies that would allow us to make comparisons with our findings on the significant demographic differences.

In 2016, different values of LOV have differential effects on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing. Sense of Belonging, Fun and Enjoyment, and Self-fulfillment were three values that had the most significant influence on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing. Sense of Belonging had a positive influence on Singaporeans’ Happiness, Enjoyment, Achievement and Purpose, while Fun and Enjoyment and Self-fulfillment both had a positive influence on Enjoyment, Achievement, Control and Purpose. It is interesting to note that the next most important value of Excitement was also a value that had a negative impact on Singaporeans’ Achievement, Control and Purpose. Warm Relationships with Others and Sense of Accomplishment had no impact at all on Singaporeans’ Happiness, Enjoyment, Achievement, Control and Purpose. The absence of any significant impact on happiness of values such as Fun and Enjoyment and Excitement is in line with what Shin and Inoguchi (2009) found in a survey of seven Confucian societies, including Singapore, that feelings of enjoyment alone do not lead to a happy life among the vast majority of the people living in these societies, but only when these people experience enjoyment together with achievement of goals and/or the satisfaction of desires and needs would they be happy or very happy with their lives.

When examining the impact of LOV on subjective wellbeing in terms of life satisfaction, Sense of Belonging, and Warm Relationships with Others were the two most important values that had a positive influence on Singaporeans’ satisfaction with life, satisfaction with overall quality of life, and satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore. Security positively influenced only Singaporeans’ satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore, while Sense of Accomplishment positively influenced only Singaporeans’ satisfaction with life. The values of Self-respect, Self-fulfillment, and Excitement had no significant roles to play on Singaporeans’ life satisfaction.

We used Schwartz’s PVQ for the first time in our 2016 QOL Survey and found that the 21 values from Schwartz’s PVQ fitted well into the four Higher Order Values of Openness, Conservation, Self-transcendence, and Self-enhancement, with better reliability than the ESS for 20 European countries (Schwartz 2007).

Europeans and Singaporeans were alike in terms of according high priority to Self-transcendence and low priority to Self-enhancement. However, unlike the Europeans, Singaporeans gave high priority to Conservation and Openness. Perhaps more cross-country and cross-cultural studies could be done to develop more insights into these similarities and differences.

In 2016, demographics contributed as sources of individual differences in all four Higher Order Values, with the exceptions of gender and education for two of the values. Gender had a positive but not significant correlation with Self-transcendence in Singapore, unlike the case of Europe and America. Education had a negative but not significant correlation with Conservation for Singaporeans, unlike America where higher education was linked with the lower importance placed on Conservation.

The four Higher Order Values had differential effects on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing. Conservation had the most wide-ranging impact on seven out of eight wellbeing indicators, followed by Self-transcendence for four wellbeing indicators (including Control and Purpose). Understandably, Self-enhancement and Openness had an impact on enjoyment. In noting these effects, we also observed some convergence with the effects of the LOV on subjective wellbeing for the wellbeing indicators of Enjoyment and Control and, to a lesser extent, on satisfaction with the overall quality of life and satisfaction with the quality of life in Singapore.

Conservation was the only Higher Order Value that had an influence (positive) on Singaporeans’ happiness. Openness and Conservation contributed positively toward Singaporeans’ Enjoyment, but Self-enhancement had a negative impact. The Higher Order Value of Openness included values of Stimulation and Hedonism, and their positive impact on Enjoyment was also in line with our findings that Fun and Enjoyment (from the LOV) had a positive and significant impact on Enjoyment. The Higher Order Value of Self-enhancement included the value of Achievement and Power, and their negative impact on Singaporeans’ Enjoyment was in line with our findings that Being Well-respected and Sense of Accomplishment (from the LOV) had a negative impact on Enjoyment (although it was not significant for Sense of Accomplishment). Conservation was the only higher order value to have an influence (positive) on Singaporeans’ Achievement.

Conservation and Self-transcendence were two Higher Order Values that had an influence (positive) on Singaporeans’ control over important aspects of their life. This finding about the Security component in Conservation corresponded to what we found about Security (from the LOV) having a positive influence on Singaporeans’ control over life’s important events. The only Higher Order Value that had an influence (positive) on Singaporeans’ sense of purpose in life was Self-transcendence, which included values of universalism and benevolence.

Conservation was the only Higher Order Value having an influence (positive) over Singaporeans’ satisfaction with life. Self-transcendence and Conservation were two Higher Order Values influencing (positively) Singaporeans’ satisfaction with overall quality of life and Singaporeans’ satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore, although Openness had a negative influence only on satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore. Given that Self-transcendence included the value of Benevolence, these findings corresponded partially to our finding on LOV that maintaining Warm Relationships with Others, among other values, had a positive and significant impact on Singaporeans’ satisfaction with their overall quality of life, as well as satisfaction with overall quality of life in Singapore.

In conclusion, values, whether in terms of the nine-item List of Values or the four-dimensional Schwartz’s Higher Order Values, have a significant influence on Singaporeans’ subjective wellbeing. Our findings also showed that certain values in LOV could be mapped to some of the basic values in Schwartz’s PVQ (Schwartz 2007). Taken together, these two value systems provided a more holistic picture of the relationship between values and subjective wellbeing in Singapore.

References

Cleaver, M., and Muller, T.E. (2002), ‘I want to pretend I’m eleven years younger: Subjective age and seniors’ motives for vacation travel’, Social Indicators Research, 60, 227–241.

Doran, C.J., and Littrell, R.F. (2013), ‘Measuring mainstream US cultural values’, Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 261–280.

Glen, N.D. (1974), ‘Aging and conservatism’, Annuals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 415, 176–186.

Grunert, S.C., and Scherhorn, G. (1990), ‘Consumer values in West Germany underlying dimensions and cross-cultural comparison with North America’, Journal of Business Research, 20, 97–107.

Gurel-Atay, E., Xie, G.X., Chen, J., and Kahle, L.R. (2010), ‘Changes in social values in the United States, 1976–2007’, Journal of Advertising Research, 50(1), 57–67.

Kahle, L.R. (1983), Social values and social change: Adaptation to life in America, New York, NY, USA: Praeger.

Kahle, L.R. (1996), ‘Social values and consumer behavior: Research from the list of values’, in The psychology of values: The Ontario symposium, edited by C. Seligman, J.M. Olson and M.P Zanna, Vol. 8, Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kau, A.K., Jung, K., Tambyah, S.K., and Tan, S.J. (2004), Understanding Singaporeans: Values, lifestyles, aspirations, and consumption behaviors, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

Kau, A.K., Tan, S.J., and Wirtz, J. (1998), Seven faces of Singaporeans: Their values, aspirations and lifestyles, Singapore: Prentice Hall.

Mitchell, A. (1983), The nine American lifestyles, New York, NY, USA: Macmillan.

Rokeach, M. (1968), Beliefs, attitudes, values, San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass.

Rokeach, M. (1973), The nature of human values, New York, NY, USA: Free Press.

Schwartz, S.H. (2007), ‘Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations’, in Measuring attitudes cross-nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey, edited by R. Jowell, C. Roberts, R. Fitzgerald and G. Eva, London, UK: Sage, 169–203.

Schwartz, S.H. (2012), ‘An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values’, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116.

Schwartz, S.H., and Rubel, T. (2005), ‘Sex differences in value priorities: Cross-cultural and multi-method studies’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 1010–1028.

Shin, D.D., and Inoguchi, I. (2009), ‘Avowed happiness in Confucian Asia: Ascertaining its distribution, patterns, and sources,’ Social Indicators Research, 92, 405–427.

Slingerland, E. (2003), Confucius analects, Indianapolis, IN, USA: Hackett Publishing.

Stockard, J., Carpenter, C., and Kahle, L. (2014), ‘Continuity and change in values in midlife: Testing the age stability hypothesis’, Experimental Aging Research, 40(2), 224–244.

Sudbury, L., and Simcock, P. (2009), ‘Understanding older consumers through cognitive age and the list of values: A U.K.-based perspective’, Psychology and Marketing, 20(1), 22–38.

Tambyah, S.K., and Tan, S.J. (2013), Happiness and wellbeing: The Singaporean experience, London, UK: Routledge.

Tyler, T.R., and Schuler, R.A. (1991), ‘Aging and attitude change’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 689–697.

Veroff, J., Reuman, D., and Feld, S. (1984), ‘Motives in American men and women across the adult life span’, Developmental Psychology, 20, 1142–1158.

World Values Survey. www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp (accessed November 17, 2017).