2

ELECTRONIC HEALTH INFORMATION, HEALTHCARE SYSTEM INTEROPERABILITY, MOBILE HEALTH, AND THE FORMATION OF A COMMUNITY OF HEALTH AND WELLNESS

Contents

Role of Electronic Health Data and Information Systems

The Role of Advanced and Predictive Data Analytics

Establishing a Data-Driven Community of Health

Healthcare reform is not new. As a nation we have been experimenting with different types of care delivery models, reimbursement methods, and the design of treatments and procedures to align with best outcomes for decades. The seeds of our current national healthcare transformation were planted in the 1970s when the medical community recognized that improving healthcare across the entire population required a primary accountable source for the healthcare of individuals.1 This resulted in the concepts of primary care providers, healthcare homes, managed care, and community-oriented care, to name a few. These concepts are well known in theory but little understood in practice. It is clear, though, that the systems in which these concepts must operate are exceptionally complex and extremely resistant to change.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) was signed into law on March 23, 2010. However, two Acts passed before PPACA, (1) the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in 1996 and (2) the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) in 2009, led to significant changes in the healthcare industry regarding patient information and electronic health records (EHRs). The HIPAA Privacy Rule protects an individual’s confidential health records from misuse and, after nearly 10 years, is generally understood throughout the healthcare community.2 While providing federal protection of individually identifiable health information, HIPAA also provides a framework to allow covered entities and business associates to disclose health information necessary for patient care coordination and other beneficial purposes. More recently, the HITECH Act was enacted to promote meaningful use of EHRs. According to the Act, there are three components of meaningful use: (1) use of a certified EHR in a meaningful way, (2) electronic exchange of health information to improve quality of healthcare, and (3) use of certified EHR technology to submit clinical quality and other measures. Organizations that achieved meaningful use by 2014 were eligible for incentive payments, while those that failed to reach those standards by 2015 would be penalized.3 Providers must demonstrate that they have complied with the meaningful use requirements to receive incentives. With these recent regulations imposed on healthcare information privacy and meaningful use, there is a greater need for methods and processes that leverage the use of data and health information technology (HIT) to document compliance and produce benefits for healthcare providers.

Currently, the Affordable Care Act is one of the most discussed and debated issues in the United States.4 This debate is vitally important because it affects every man, woman, and child both today and tomorrow. Major drivers for healthcare reform are (1) the increasingly poor health of our citizens and (2) the fragmented and mismanaged provider community.

Unhealthy patients may be:

• Difficult to diagnose

• Expensive to treat

• Unproductive at work

• Unmotivated to take care of themselves

• Unintentionally affecting the economy through poor health choices and suboptimal care

• Inadvertently affecting future generations by creating a culture of illness

Healthcare providers are often:

• Burdened with administrative and bureaucratic

• Unable to easily coordinate between primary care providers and specialists

• Pressed to see more patients or provide more services with less time and support

• Pressured to increase revenue and salaries year over year

• Unable to obtain patient information in a timely, cost-effective way

• Confused about how they will be “graded” on the quality of care given to their patients

Adding to this complexity, hospitals, health plans, third-party administrators, and self-insured employer groups are facing an increasingly competitive market landscape demanding price transparency, program safeguards, disease management, health and wellness programs, and a more expansive provider network. These known challenges as well as new challenges that are developing nearly every day as we gain more experience with the Affordable Care Act create innumerable opportunities for healthcare informatics groups to:

• Analyze stakeholder behaviors and experiences

• Define the challenges

• Research the issues

• Refine the problems

• Develop the solutions

• Track the outcomes

Finally, providers must now make the difficult shift away from volume-based healthcare toward value-based healthcare because of recent changes in the healthcare industry.5 Beginning in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) made changes to provider reimbursement policy by advocating alternative payment models like those used by Medicare Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations (MSSP ACO).6,7 Providers who participate in these programs are held accountable for both the quality and cost of care and are rewarded for value, improving health outcomes, and reducing costs. The goal is to have 30% of Medicare payments tied to these models by the year 2016, increasing to 50% of payments by the year 2018. This new payment system has already produced a significant increase in quality and reduction in spending with a Medicare savings of $417 million.8

Despite these challenges, changes in the healthcare landscape have also produced many opportunities. The increasing use of EHRs and other health information technologies (HITs) provides opportunities to leverage health data to develop and implement community-based health and wellness initiatives. One of the most promising of these initiatives is the formation of Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) that are designed to collect, store, and share data that can be used to develop actionable information for healthcare and social service providers as well as to empower consumers to improve their own health and wellness. To achieve these goals HIEs must assimilate disparate sources of data into information technology solutions that interface with a variety of systems used by healthcare providers, social service agencies, and consumers. One method of HIE provision involves the creation of a single-source information platform to which multiple providers and community organizations contribute and from which those same organizations extract more comprehensive patient and/ or client information than each could individually acquire. In this chapter we examine the use of electronic health data and information technology to support accountable care. In other words, accountable care that is reinforced by health information exchanges, data integration, and interoperable systems to support a community of health.

Role of Electronic Health Data and Information Systems

Amazingly, electronic healthcare data in the United States exceeded 150 exabytes (one exabyte equals one billion gigabytes) in 2011 and was predicted to increase annually at a rate of 1.2 to 2.4 exabytes. The use of electronic healthcare data has the potential to lower costs and increase the quality of healthcare by substantially improving the ability to make informed decisions. The benefits to healthcare of electronic data–supported decision making include early detection of diseases, population health management, fraud and abuse detection, and more accurate clinical predictions and financial forecasts. By applying analytics to these data, providers can detect diseases and chronic conditions sooner, thereby increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of patient treatment. For example, Premier, a healthcare alliance network, has estimated that insights provided by electronic healthcare data have resulted in approximately 29,000 lives saved and $7 million in reduced spending, demonstrating that data accessibility can be crucial to providing quality care to patients.9

Managing population health through the integration of multiple, disparate data sources is essential to delivering a more complete view of the patient to providers. As illustrated in Figure 2.1, the sources of information available for a single member within a medical home (i.e., an accountable care scenario) range from primary and specialty care to behavioral health and nurse advice services. In turn, each type of service benefits from the availability of far more complete information regarding a particular member’s situation that is derived from the contributions of all service types.

Figure 2.1 The complexity of electronic data integration in healthcare.

The use of HIEs plays a major role in supporting this data-driven comprehensive portrait of individual patients. HIEs are networks that facilitate the integration and sharing of relevant patient-level health information between patients and their providers. For example, the purpose of an HIE is to manage all of the electronic data collected and stored by a patient’s many care providers such as (1) medical providers, (2) healthcare facility providers, (3) clinic and health center providers, (4) transportation and durable medical equipment providers, and (5) social service and behavioral health providers. This creates a data environment that supports the exchange of health information that providers can use to provide the best possible care based on the most current health-related information about the patient. When used appropriately, HIEs can improve the quality, cost, effectiveness, and efficiency of healthcare.

In particular, as healthcare transitions from volume-based to value-based delivery, hospitals and providers will increasingly depend on HIEs to make this transition. HIEs are critical to the success of value-based healthcare because they:

• Create a foundation for data integration and interoperability

• Provide more efficient physician referral processes

• Enable providers to obtain a more complete understanding of their patients

• Enable broader provider networks

• Support the business transformation of health systems10

Value-based healthcare would have difficulty succeeding without a standardized, interoperable HIE that uses the latest HIT, analytics, management solutions, and reporting capabilities.

Although there are a variety of methods for sharing, storing, and retrieving patient data, we advocate a data integration model that relies on a single, interoperable platform that supports the information systems required to acquire, integrate, and store the different data types that are necessary to build a complete health profile for an individual.

The Role of Advanced and Predictive Data Analytics

Advanced data analytics provide risk-bearing healthcare organizations actionable information designed to help key stakeholders better understand the populations they serve by delivering understandable, consistent information to all levels of an organization. Analytics are generated by incorporating multiple data sources, such as healthcare claims data, electronic health records, survey and assessment data, as well as others. This ensures data-driven, reliable care—the hallmark of successful and sustainable healthcare programs. Some of the most common complaints against population health analytic solutions are that:

• They provide too much data which overwhelms the user.

• Data and results are not presented in a user-friendly format to the typical physician and his/her staff.

• Data and results are not easily actionable, especially at the patient level.

Consequently, a strong analytics platform should include the following features: (1) identification of the risks and risk drivers for the managed population/s; (2) creation of actionable intelligence for better decision making; (3) simplification of the complexity of managing atrisk populations by means of understandable, consistent information; (4) use of best-practice clinical documentation; (5) correct assignment of an individual patient’s healthcare risk; and (6) evaluation of the medical necessity of available healthcare services.

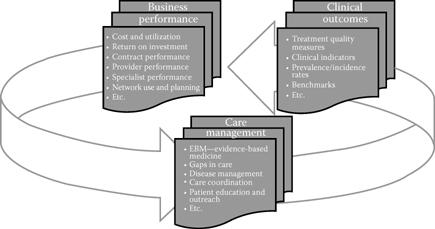

As illustrated in the preceding text, there is a strong link between care management, clinical outcomes, and business performance (Figure 2.2). It is well known that 20% of an ACO’s members will generate at least 80% of healthcare costs in a given year.11 The formula for program success is the ability to identify which members will be among the high cost 20% of members during the next 12 months in the absence of appropriate care management and intervention. Improved predictive accuracy involves going well beyond standard episodic, grouper-based analysis (e.g., Episode Treatment Groups) or utilization-based models (e.g., Diagnostic Cost Groups). The key to better patient identification and targeting is a better understanding of how psychosocial factors along with clinical indicators influence the behaviors that result in either good or bad health outcomes. In its simplest form, the ability to incorporate life circumstances data (e.g., living below the poverty level), lifestyle demographic data (e.g., divorced and living alone), personal behavioral data (e.g., depression and stress) with cost, utilization, and clinical data result in a highly accurate approach to patient targeting and resource allocation. This approach provides actionable information—information providers and caregivers know how to use to help their patients.

Figure 2.2 Linkage of care management, clinical outcomes, and business performance.

Establishing a Data-Driven Community of Health

There are significant community health challenges in many areas of the United States, especially rural regions. According to the Health Resources and Services Administration division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 19.3% of the population was rural as of the last Census.12 Eighty-two percent of rural counties are classified as Medically Underserved Areas, with only 9% of physicians practicing in these areas. To make matters worse, rural areas depend on primary care physicians, but only around 2% of medical students plan to specialize in primary care.13 Clearly, these workforce shortages cannot be resolved quickly, underscoring the need to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare services in these economically distressed, rural communities.

Rural healthcare challenges also result from a number of population characteristics, including financial factors and the employment status of citizens in these areas. The number of self-employed workers in rural areas has increased by 240% since 1969. With lower rates of employer-sponsored insurance, rural citizens have significantly higher rates of un-insurance as well as under-insurance, around 70% higher than in urban areas.14 To meet these challenges rural healthcare providers (e.g., hospitals, clinics, and practices) are developing Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs), and community-based health and wellness initiatives. To improve the healthcare in a rural community, these providers must find ways to increase community engagement/awareness, develop and implement population-based health strategies, and work with nontraditional partners such as churches, community centers, and schools.

Given the difficulty delivering optimal healthcare in a rural setting, the importance of secure, interoperable health information technology and tools to support providers and caregivers is paramount. The goal is to create an environment where health information is available to all care providing organizations, thereby supporting rural citizens in establishing and sustaining a community of health. However, one of the major obstacles to realizing this goal is the current lack of integration of data from the various provider types essential to the formation of a community of health. Examples of common provider types in rural communities are small hospitals, primary care provider groups, Federally Qualified Health Clinics (FQHCs), health departments, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, emergency medical services, behavioral health providers, and social service agencies. Providing the foundation and framework for the sharing of health information crucial to the health and wellness of the region requires open-source, interoperable health IT tools. These tools can be used to implement or to support and extend existing health information exchange solutions in a scalable, replicable, and transferable way.

As shown in Figure 2.3, to support the data integration and systems interoperability needed in a rural setting we advocate an IT infrastructure consisting of a centralized data repository with integration tools designed to execute automated ETL (extract/transform/load) functions with data (e.g., medical claims, electronic medical/health records, behavioral health claims, and social service agencies) from multiple sources. After the data are moved from their sources they are remodeled to fit a standardized framework necessary for analysis and reporting. Secure, HIPAA compliant, database servers store the data. A business intelligence and reporting system is used to present users with summary financial and clinical reports via a web interface. The system is designed to provide improved patient/client information, leading to health improvements as well as cost efficiencies, such as closing referral gaps.15

Figure 2.3 Information flow in a general health information exchange framework.

Mobile Health in the Pipeline

Another area that is quickly evolving in the healthcare arena that shows great promise in not only addressing the issue mentioned in the preceding text (e.g., rural health) but for the entire industry, is wireless mobile health technologies. Advancements in wireless capabilities; data storage, processing, and communication; and software applications (apps) have enabled individuals of all walks to communicate and tap into information through mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets.

Mobile devices, enabling texting, emails, access to the web, and use of apps, provide the platform to information access, retrieval, and communication in near real time. Industries of all types have tapped into this electronic highway for marketing, supply chain, customer service, sales, customer relationship management, production, workflow, and so forth. This second wave of the information economy has transformed global commerce.16 the communication evolution not only has transformed traditional operations of business, but with the vast adoption of mobile devices, social media has impacted behavioral attributes of society as well.

Healthcare has not ignored this second wave of the information economy as the impact of technologies currently deployed in healthcare and the prospects of technologies in the pipeline are impressive. Wireless medical sensors have been deployed to monitor and help track chronic conditions such as diabetes. These devices monitor patients’ vital signs (glucose levels, blood pressure, etc.); alerting systems help enhance patient adherence to medications; and portals provide preventative care and care maintenance information. Communication devices such as Fitbit® provide health consciousness consumers with information on calories burned, intensity of physical activity such as walking, and sleep quality. However, the true potential of these initial applications have not nearly been achieved. Issues such as data quality and consistency (e.g., the reliability of data feeds from sensors placed on the body and how metrics are reported), privacy/security, analytics, and network effects must evolve to create a more robust mobile health environment.

Some individuals remain skeptical of the presence of a full-blown mobile health platform given issues just mentioned. However, one must keep in mind the recent evolution of the e-based world that now exists. In the “old days” dating back about a decade ago, it was hard to imagine a phone that could search the web, provide voice based applications, take quality photos, record streaming video, optimize travel activities, and enhance purchase activities to name a few. Nor could many envision the societal adoption of social media and its corresponding functionality and impacts on consumption, marketing, politics, news, and so forth. Just a few years can bring about dramatic change to the world we live in, given the rate of technological innovation.

This time healthcare does not look to be far behind.17 Some of the promise of mobile health functionality made possible by the development of apps, wireless communication, smartphones, and mobile sensing devices have already been achieved. Today, the utilization of mobile health has been more for providing information and education to patients regarding self-care, treatment, and prescriptions through available web information resources and messaging. However, the future should shift more toward improving communication between patients and their care professionals regarding health status and treatment; improving awareness through self-monitoring; and facilitating social support and knowledge exchange between patients, peers, and providers.18 Some devices that are in use so far either in actual commercial applications (e.g., glucometers) or in pilot testing include devices that monitor patient information (weight, glucose levels and other vital signs) which can be connected to care providers which provide analytics, which is beneficial for treatment of important chronic ailments such as diabetes and CHF.19 These devices provide a data feed to care providers that can combine current data with existing medical records on EHRs, and with the incorporation of analytics including visual capabilities, provide an information source to portals that are accessed by mobile devices and enable patients and care providers to interact and exchange messages. Figure 2.4 provides a simplistic but important illustration of the mobile process. Other examples of applications in the pipeline include decision support devices that cover heart and vascular conditions for cardiac patients and workflow apps that enhance scheduling times for patients seeking care at the emergency room (ER). By communicating patient data such as symptoms and accessing workflow activities at an ER (e.g., patient volume, staff) more accurate expected ER service time can be arranged. With the emergence of accountable care organizations, the demand for mobile health intensifies, as the ACO platform involves the use of patient care coordinators who need to communicate with patients in a non-physical remote fashion to manage cases.20

Growing demand for mobile service from all areas of healthcare, in conjunction with major organizations providing supportive technologies (e.g., Google Fit, Apple HealthKit, AT&T ForHealth) along with government funding to maintain a stable development environment, and the widespread and growing adoption of mobile devices by individuals on a global spectrum, have spurred the supply of technological innovation to eventually create a robust platform for mobile health. The barriers of such a platform such as data quality, consistency, and security; integration between technological components; quality and reliability of reporting capabilities and behavioral issues such as individual adoption of devices, must be overcome. The results could be far reaching with potential cost savings resulting from a reduction in physical meetings and examinations between provider and patient; reduction in readmit rates due to more effective, ongoing care management; reduction in the number of developed cases of chronic diseases; more timely treatment at the episode level; enhanced workflow optimization by providers, and the list goes on.

Figure 2.4 Simple but important illustration of mobile health process.

For further details on the evolution of wireless devices in healthcare, see Chapter 9.

Conclusions

Coordination of care refers to “the integration of care in consultation with patients, their families, and caregivers across all of the patients’ conditions, needs, clinicians and settings.”21 To create a community of health and wellness, one of the foremost challenges is how to coordinate the care of individuals across many different provider types, hospitals and other in-patient facilities, government agencies, and social service organizations, as well as other organizations that serve the population. HIEs provide a framework for data integration and interoperability. However, HIEs do not ensure coordination of care unless all healthcare constituents are aware of and actively use the systems.

While the use of EHRs provides a framework to collect, organize, and store healthcare data, significant issues remain that must be resolved to create actionable information at the individual patient level. Many provider groups have difficulty recruiting employees with the appropriate information technology training required to keep these systems operable to meet both the current and future needs of their organizations.22 Furthermore, once EHRs are operational, the lack of standardization among different EHR software solutions makes it difficult or impossible for multiple sites to efficiently share information, thus falling short of the need for usability, portability, and ease of communication between all constituents.

The inability to coordinate care may also exacerbate another chronic problem faced by healthcare providers. Providers spend an inordinate amount of time and money attempting to effectively treat noncompliant patients, who come into the office suffering from acute or chronic conditions, only to return repeatedly for the same issues. Noncompliance with treatment is often framed as a patients’ resistance or inability to care for themselves once they are no longer under the direct supervision of their providers. Newer perspectives in healthcare focus on the importance of patient-centered care, and, ultimately, the engagement of patients, to improve the ability of individuals to actively participate in healthcare along with their care providers. Research shows that encouraging patients to be active consumers of healthcare results in increased engagement and greater responsibility for their own health and wellness. To lessen the occurrence of noncompliance and increase patient engagement with their healthcare it is essential for all types of care providers to share information with each other and with the patient to track and provide support for patient adherence to medical advice.23

HIEs facilitated by data integration and interoperable systems are necessary to support a sustainable community of health. Giving providers a more complete, whole health, picture of their patients reduces redundancy, improves efficiency, and builds patient confidence and engagement, all of which can contribute to cost reductions across the continuum of care. By integrating multiple sources of data, such as behavioral and physical health providers, along with information about the life circumstances that affect patients’ healthcare behaviors, improvements for individual patients will result in better health of the community. Ultimately, electronic health information and healthcare system interoperability will contribute to building a learning health system by providing timely and actionable information that allows each stakeholder to continuously improve his or her care and contribute to the usefulness of the system as a whole. Better informed decisions will result, reducing the duplication of services, improving patient education, decreasing chronic health conditions, and, finally, decreasing the cost of care.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank contributions from Tennessee Tech University graduate students Zach Budesa and Shannon Cook.

References

1. Fox PD, Kongstvedt PR. 2007. An overview of managed care. In The essentials of managed health care (pp. 3–18). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

2. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/.

3. http://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives.

4. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/.

5. Miller HD. 2009. From volume to value: Better ways to pay for health care. Health Affairs, 28(5), 1418–28.

6. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html?redirect=/sharedsavingsprogram/.

7. Gold J. 2015. Accountable Care Organizations, Explained. Kaiser Health News. Available at: http://khn.org/news/aco-accountable-care-organization-faq/, September 14.

8. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2015pres/01/20150126a.html.

9. Raghupathi W, Raghupathi V. 2014. Big data analytics in healthcare: Promise andpotential. Health Inf Sci Syst 2(3), doi:10.1186/2047-2501-2-3.

10. McNickle M. 2012. 5 reasons HIEs are critical to the success of ACOs. Healthcare IT News August 7, 2012.

11. Robertson T, Lofgren R. 2015. Where population health misses the mark: Breaking the 80/20 rule. Acad Med 90(3):277–78.

12. http://www.hrsa.gov/ruralhealth/policy/definition_of_rural.html.

13. Bailey JM. 2009. The top 10 rural issues for health care reform. Lyons, Nebraska: Center for Rural Affairs, March.

14. Ziller EC, Coburn AF, Yousefian AE. 2006. Out-of-pocket health spending and the rural underinsured. Health Aff 25(6):1688–99.

15. Ham N. 2014. Closing the gap on tarnsitions of care. Becker’s Hospital Review. Available at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/quality/closing-the-gap-on-transitions-of-care.html, Oct.

16. Kudyba S. 2014. Big data mining and analytics: Components of strategic decisions. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

17. What is healthcare informatics? Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pzS—PaGC9o.

18. McKesson (Editorial Staff), 2015. Major shift coming in the use of mobile health technologies. Available at: http://www.mckesson.com/blog/changing-trends-in-mobile-health-technology/.

19. Steakley L. 2016. Harnessing mobile health technologies to transform human health. Stanford Medicine. Available at: http://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2015/03/16/harnessing-mobile-health-technologies-to-transform-human-health/.

20. Conn J. 2014. Going mobile: Providers deploy apps and devices to engage patients and cut costs. Modern Health. Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141129/MAGAZINE/311299980.

21. O’Malley AS, Grossman JM, Cohen GR, Kemper NM, Pham HH. 2010. Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Intern Med 25(3):177–85.

22. Walker J, Pan E, Johnston D, Adler-Milstein J, Bates DW, Middleton B. 2005. The value of health care information exchange and interoperability. Health Aff (Millwood), Jan–Jun; Suppl Web Exclusives: W5-10-W5-18.

23. Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. 2001. Patient adherence to treatment: Three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther 26(5):331–42.