2. Deciding How to Decide

“Chance favors the prepared mind.”

—Louis Pasteur

In April 1961, President John F. Kennedy made the decision to authorize U.S. government assistance for the Bay of Pigs invasion—an attempt by 1,400 Cuban exiles to overthrow the Castro regime. Three days after the brigade of rebels landed on the coast of Cuba, nearly all of them had been killed or captured by Castro’s troops. The invasion was a complete disaster, both in terms of the loss of life and the political damage for the new president. Nations around the world condemned the Kennedy administration’s actions. As the president recognized the dreadful consequences of his decision to support the invasion, he asked his advisers, “How could I have been so stupid to let them go ahead?”1

The president and his advisers certainly did not lack intelligence; David Halberstam once described them as “the best and the brightest” of their generation.2 Nevertheless, the Bay of Pigs decision-making process had many flaws.3 Veteran officials from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) advocated forcefully for the invasion, and they filtered the information and analysis presented to Kennedy. The proponents of the invasion also excluded lower-level State Department officials from the deliberations for fear that they might expose their plan’s weaknesses and risks. Throughout the discussions, the president and his Cabinet members often deferred to the CIA officials, who appeared to be the experts on this matter, and they chose to downplay their reservations about the invasion. Kennedy did not seek out unbiased experts to counsel him. Arthur Schlesinger, a historian serving as an adviser to the president at the time, later wrote that the discussions about the CIA’s plan seemed to take place amid “a curious atmosphere of assumed consensus.”4

In the absence of vigorous dissent and debate, the group did not examine multiple alternatives. Instead, it framed the issue as a “go versus no-go” decision. Many critical assumptions remained unchallenged. For instance, the CIA officials argued repeatedly that Cuban citizens would rise up against the Castro government as soon as the exiles landed at the Bay of Pigs, thereby weakening the Communist dictator’s ability to repel the invading force. No such domestic uprising ever took place. Proponents also contended that the exiles could retreat rather easily to the mountains nearby if they encountered stiff opposition upon landing on the shore. However, the invading force would need to travel over rough terrain for nearly 80 miles to reach the safety of those mountains.5

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara explained that, before making the final decision, Kennedy went around the room and asked each adviser, “Should we do it or not?” Not one Cabinet member expressed opposition. McNamara commented, “I don’t think Secretary of State Dean Rusk and I were enthusiastic, but we didn’t say no, don’t do it. Hell, I didn’t know my way around the Pentagon at that point, much less to take exception to this CIA operation.” McNamara described the pressure that he felt to go along with the CIA plan: “Even though some had thoughts that it was an irrational or unreasonable operation, there was great pressure to support it.”6

After the botched invasion, President Kennedy addressed the nation and took full responsibility for the terrible decisions that had been made. McNamara offered to appear on television shortly after Kennedy’s speech. He wanted to explain to the American people that the Cabinet had done the president a great disservice, that many officials had not expressed their concerns and reservations about the CIA plan. The president rejected McNamara’s offer: “No, no, Bob. It was my responsibility. I didn’t have to take the advice. I have to stand up and take responsibility.”7

After the speech, Kennedy conducted an evaluation of his foreign policy decision-making process and instituted several key improvements. In October 1962, when Kennedy learned that the Soviets had placed nuclear missiles in Cuba, he assembled a group of advisers to help him decide how to proceed, and he put these process improvements into action.8 This group, known as Ex Comm (an abbreviation for Executive Committee of the National Security Council), met repeatedly throughout the Cuban missile crisis.9 McNamara described the president’s directive to his advisers:

He appointed a select group. He said, “Don’t tell anybody, not your closest associates, about these photographs we have of the missiles there. We don’t want outside pressures on us until we’ve thought through what to do, debated it, and come to some conclusions.” He told this small group, consisting of thirteen to fifteen people: “I want you to meet, I won’t be there, and I want you to debate with each other what you think ought to be done.” So, we met without him many times for essentially a week. He knew what was important. That’s the way to get your people to be frank.10

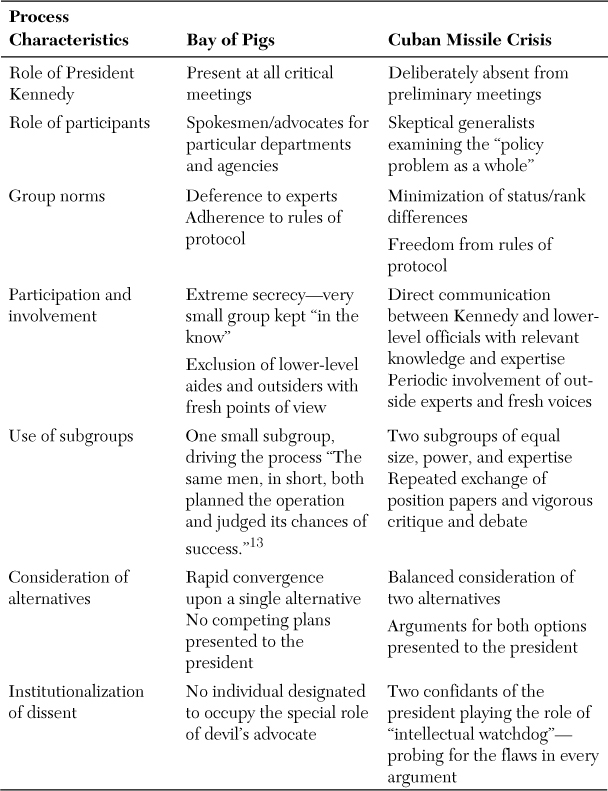

What process changes did Kennedy enact? First, the president directed the group to abandon the usual rules of protocol and deference to rank during meetings. When he did not attend meetings, the group operated without an official chairman. He did not want status differences or rigid procedures to stifle candid discussion. Second, Kennedy urged each adviser not to participate in the deliberations as a spokesman for his department; instead, he wanted each person to take on role of a “skeptical generalist.” Kennedy directed each adviser to consider the “policy problem as a whole, rather than approaching the issues in the traditional bureaucratic way whereby each man confines his remarks to the special aspects in which he considers himself to be an expert and avoids arguing about issues on which others present are supposedly more expert than he.”11 Third, the president invited lower-level officials and outside experts to join the deliberations occasionally to ensure access to fresh points of view and unfiltered information and analysis. Fourth, members of Ex Comm split into subgroups to develop the arguments for two alternative courses of action. One subgroup drafted a paper outlining the plan for a military air strike, while the other articulated the strategy for a blockade. The subgroups exchanged memos and developed detailed critiques of one another’s proposals. This back-and-forth continued until each subgroup was prepared to present its arguments to the president. Fifth, Robert Kennedy and Theodore Sorensen, two of the president’s closest confidants, were assigned to play the role of devil’s advocates during the decision-making process. Kennedy wanted them to surface and challenge every important assumption as well as to identify the weaknesses and risks associated with each proposal. Sixth, the president deliberately chose not to attend many of the preliminary meetings that took place, so as to encourage people to air their views openly and honestly. Finally, Kennedy did not try to make the decision based upon a single recommendation put forth after his advisers had discussed and evaluated the situation. Instead, he asked that his advisers present him with arguments for alternative strategies, and then he assumed the responsibility for selecting the appropriate course of action.12 For a summary of the differences between the two decision-making processes, see Table 2.1.

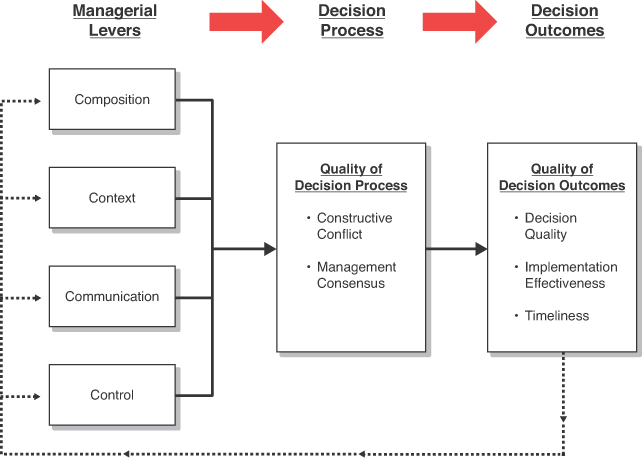

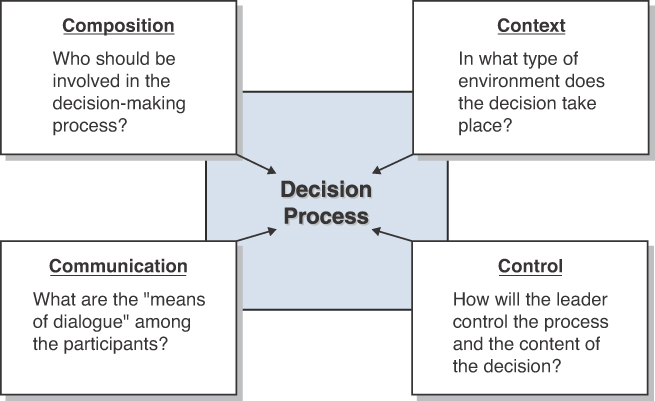

This case demonstrates how leaders can learn from failures and then change the process of decision making that they employ in the future. Here, we see President Kennedy identifying the flaws in the processes employed in the Bay of Pigs and then deciding how to decide in critical foreign policy situations going forward. Kennedy recognized that the Bay of Pigs deliberations lacked sufficient debate and dissent and that he had incorrectly presumed that a great deal of consensus existed, when, in fact, latent discontent festered within the group. Perhaps more importantly, Kennedy understood that he had not given much thought to how the Bay of Pigs decision should be made before plunging into deliberations. Consequently, ardent advocates of the invasion took control of the process and drove it to their preferred conclusion. By making key process design choices at the outset of the Cuban missile crisis, Kennedy shaped and influenced how that decision process unfolded, and in so doing, he enhanced the quality of the solution that he and his team developed. This chapter takes a closer look at the managerial levers that leaders can use to set the stage for an effective decision-making process and introduces a conceptual framework to help leaders think about the impact of those levers (see Figures 2.1 and 2.2).

Managerial Levers

A leader makes four important sets of choices that affect his ability to cultivate constructive conflict and build enduring consensus. First, a leader determines the composition of the decision-making body. Who should have an opportunity to participate in the process? What should drive those choices? Second, he shapes the context in which deliberations will take place. What norms and ground rules will govern the discussions? Third, a leader determines how communication will take place among the participants. How will people exchange ideas and information, as well as generate and evaluate alternatives? Finally, a leader must determine the extent and manner in which he will control the process and content of the decision. What role will the leader play during discussions, and how will he direct the process? As we shall see, Kennedy’s process improvements after the Bay of Pigs entailed changes in each of these four areas.

Composition

When making strategic choices, most executives do not simply consult with the set of direct reports with whom they meet on a regular basis, nor should they expect that this particular group is well suited to make all high-stakes decisions. Like President Kennedy, one should assemble a decision-making body based upon an assessment of the needs of the situation at hand. For instance, Ex Comm included many, but not all, members of the president’s Cabinet. It also contained individuals who did not report directly to the president and who did not participate regularly in Cabinet meetings. In most instances, leaders need to be willing to draw upon people at multiple levels of the organization as the decision process unfolds. Naturally, a leader must act with care when bypassing senior staff members to speak with individuals at lower levels. Being open and transparent about such communications is a must.

Every leader faces a crucial decision about the size of the team that he should assemble to examine a crucial decision. Many leaders bring together teams that are far too large. Advertising executive Ken Segall worked with Steve Jobs for many years. He helped developed the iMac branding strategy and the “Think Different” advertising campaign. Segall notes that he learned the virtue of small teams while working with Apple. Steve Jobs believed that large teams easily become unfocused. He felt that motivation, information sharing, and coordination problems cause large teams to underperform their potential. Segall even recalls one day when Jobs began a meeting by asking someone to leave because he did not deem that person’s contribution essential to the task at hand. Segall explains the virtue of keeping teams small:

Start with small groups of smart people—and keep them small. Every time the body count goes higher, you’re simply inviting complexity to take a seat at the table....The idea is pretty basic: Everyone in the room should be there for a reason. There’s no such thing as a “mercy invitation.” Either you’re critical to the meeting or you’re not. It’s nothing personal, just business.14

Google’s Larry Page has directed managers to keep the head count at decision-oriented meetings to 10 or fewer people.15 Brad Smith, CEO of Intuit, believes in the virtues of small teams as well. He explained that product development teams at Intuit adhere to the “Two Pizza Rule.” In other words, the teams must be small enough to be fed with two large pizzas. If everyone eats two slices of pizza, that rule tends to limit teams to about 8 members.16 While a relatively simple heuristic, the “Two Pizza Rule” reminds everyone that groups can easily become cumbersome and unwieldy.

Interestingly, Maria Guadalupe, Hongyi Li, and Julie Wulf have conducted a study of the changing size and composition of senior management teams. The scholars compiled a dataset of U.S. firms from 1986 to 2006. They found that the size of the typical top management team doubled during this 20-year period, from 5 to 10 members.17 Wharton’s Jennifer Mueller conducted an interesting study on the effects of team size. She found that relationships among team members may not be as strong in larger groups and that this can decrease individual performance. She explained, “There are costs to collaborating. In larger teams, one of those costs is that people may not have the time and energy to form relationships that really help their ability to be productive.”18

Leaders need to think about the type of people that they want involved in a decision, not simply the size of the group. Job titles, positions in the organizational hierarchy, and considerations of status and power within the firm should not be the primary determinants of participation in a complex high-stakes decision-making process. Instead, the leader should consider four other factors—access to expertise, implementation needs, the role of personal confidants, and the effects of demographic differences—when selecting who should become involved in a set of deliberations.19

First, people should participate if they have knowledge and expertise that is relevant to the situation at hand. When scanning potential participants, the leader ought to ask himself “Can a particular individual provide data or information that others do not possess?” Beyond that, one should consider whether an individual might be useful to offer a fresh point of view during deliberations or perhaps to counter the conventional wisdom that prevails among most of the apparent experts on the matter. In the Bay of Pigs invasion, President Kennedy failed to ensure that key players from the State Department, with deep knowledge of the Cuban government and society, participated in the Cabinet-level discussions regarding the CIA’s invasion plan. In contrast, Kennedy reached down below the level of his direct reports during the Cuban missile crisis to ensure that he had access to unfiltered information from people with knowledge pertinent to the situation.

Leaders need to be willing to communicate directly with people several levels down in an organization when making critical decisions. Otherwise, they will be relying on data and analysis that often has been summarized and packaged for presentation in a way that distorts the true picture of the situation. Information often becomes massaged and filtered on its way up the hierarchy. Consequently, leaders often find themselves confronted with a set of analyses that downplays important risks, fails to acknowledge conflicting interpretations of the data among lower-level officials, and offers a slanted argument in defense of a particular proposal.20

In the Columbia space shuttle tragedy, we see a vivid example of how executives can fail to assess a dangerous threat accurately because they have not been presented with all the information required to make a sound decision. After the foam strike during the launch of Columbia, some lower-level engineers became extremely concerned about the possibility of catastrophe upon reentry into the earth’s atmosphere. As we now know, those engineers exchanged an extensive series of e-mails, questioning the judgment put forth by respected technical experts and managers that the foam strike did not present a “safety of flight” issue. However, senior executives at NASA did not become aware of these concerns, nor of the extensive disagreement among lower-level officials, until after the tragedy took place. NASA managers relied too much on job titles and the rules of protocol to dictate patterns of involvement and participation in the decision process. They should have actively solicited the views of knowledgeable individuals at lower levels of the hierarchy, and they should have probed further to ensure that they understood the uncertainties, presumptions, and conflicting interpretations associated with the analysis of the debris strike that occurred during launch.21

Of course, expertise alone should not dictate participation in a strategic decision-making process. Leaders also need to consider how a decision will be implemented across the organization. If managers know that someone will play a critical role during the implementation process, it may make sense to solicit that person’s advice during the decision process. The involvement of key implementers has two obvious advantages. First, it enables senior executives to incorporate into their decision process detailed information about the costs and challenges of carrying out each alternative course of action. As a middle manager at one aerospace firm told me, he became involved in a high-level business restructuring decision because, as someone who would be ultimately responsible for enacting critical facets of the decision, he could “work a straw man implementation plan that we could cost to come up with what investment would be required to execute particular alternatives.” Second, executives build commitment and shared understanding throughout the organization by involving key implementers in the decision-making process. Individuals often become disenchanted if they are asked to carry out a plan for which they have had little or no opportunity to provide input. Giving implementers a voice in the decision process enables executives to build a sense of collective ownership of the plan. When individuals feel that it is “their decision” as opposed to “management’s decision,” they are more likely to go the extra mile during the implementation process.22

Personal relationships also can and should shape the composition of the decision-making body that a leader assembles when faced with the need to make an important strategic choice. No, one should not rely on cronies or sycophants when making key decisions. However, leaders can benefit by drawing on people with whom they have a strong personal bond, characterized by mutual trust and respect, to help them think through complex issues. In fact, in an insightful study of top management teams in the computer industry, Stanford University professor Kathleen Eisenhardt found that the more successful chief executives consistently utilized a few close confidants as sounding boards on strategic issues.23 She described these individuals as “experienced counselors” who met with the leader privately, listened to his doubts and concerns, and offered candid advice. Whereas Eisenhardt’s study showed that the “oldest and most experienced executives filled the counselor role,”24 my own research across many different types of organizations shows that leaders tend to select confidants not according to seniority, but because they admire the personal character, intelligence, and integrity of the individuals, and they have a strong prior working relationship with them. The president of a defense contractor explained, “He and I tend to go off-line with each other. At 7:30 in the morning or 6:00 in the evening, we compare notes and do sanity checks with one another. He and I have worked together and known each other for a long time, and we have a great mutual respect for each other.”25

These confidants play a particularly important role when managers operate in turbulent and ambiguous environments because most leaders face a few critical moments of indecision and doubt prior to making high-stakes choices.26 Eisenhardt’s research shows that confidants not only offer solid advice and a fresh point of view to leaders, they also help them overcome last-minute misgivings and protect against the pernicious tendency toward indecisiveness, delay, and procrastination that often prevails in organizations faced with high environmental ambiguity and turbulence.27

Leaders also can draw upon close personal confidants to play special roles in decision-making processes. For example, President Kennedy asked Ted Sorensen and his brother, Robert, to play the role of the devil’s advocate during the Cuban missile crisis. At first glance, it may seem odd that the attorney general and a speechwriter were involved at all in such a momentous foreign policy decision. Their positions in the bureaucracy certainly did not dictate their involvement in the process. However, the president trusted these two men a great deal and valued their judgment. Kennedy knew that others would not be quick to dismiss critiques offered by these two individuals because of the well-known personal bond between them and the president. In addition, Kennedy recognized that these two men would be more comfortable than most other advisers when it came to challenging his own views and opinions.

Finally, as leaders select people with whom to advise and consult, they should consider how demographic similarities and differences among participants shape the nature and quality of decision-making processes. Does one want to bring together a highly diverse group of people, or should a leader surround himself with people of similar backgrounds? The answer may seem obvious, but before we accept the conventional wisdom, we ought to examine the research findings on this issue.

A long stream of research on top management teams has explored the question of whether demographic heterogeneity enhances team and organizational performance. By demographic heterogeneity, researchers mean differences among team members in age, gender, team and organizational tenure, functional background, and the like. Many scholars have argued that heterogeneous groups should outperform more homogenous ones because the former ought to exhibit greater cognitive diversity. In other words, groups benefit from give-and-take among people with different perspectives, expertise, talents, and approaches to problem solving. Historians too have argued that leaders can benefit from diverse teams of advisers. In her book Team of Rivals, Doris Kearns Goodwin explained that President Abraham Lincoln appointed several key political competitors to his Cabinet, and he benefited greatly from their advice and counsel during the Civil War.28

Empirical studies, however, have produced conflicting results regarding the impact of demographic heterogeneity on senior team and organizational performance. How do we explain these contradictory findings? Diverse groups tend to generate higher levels of cognitive conflict, but as argued in Chapter 1, “The Leadership Challenge,” intense debates often lead to affective conflict. Moreover, high levels of heterogeneity sometimes can be associated with less-frequent communication among members, lower levels of cohesiveness, weaker identification with the group, and enhanced coordination challenges. Consequently, diverse groups may find it difficult to keep conflict constructive and build management consensus.29

Leaders should not conclude from this analysis that they should refrain from building diverse teams. Instead, as they assemble groups of advisers, they need to be aware of the needs of their situation. If the decision at hand requires a great deal of novel and creative thinking, and if the leader’s usual group of advisers occasionally falls in the trap of thinking alike, he may want to strive for increased heterogeneity. In contrast, if the decision implementation necessitates frequent communication and intense coordination, and the usual set of advisers has encountered difficulty reconciling starkly contrasting views of the world, the leader may lean toward a bit more homogeneity. Perhaps more important than trying to achieve the optimal level of diversity, leaders should begin each decision process by surveying the demographic similarities/differences among key participants, and then seek measures to counterbalance the pitfalls associated with high levels of either homogeneity or heterogeneity.30

Context

Ensuring that the appropriate mix of individuals becomes involved in an issue represents just a small portion of the challenge for managers trying to develop a high-quality decision process. Managers also have an opportunity to shape and influence the context in which that process takes place. Context affects behavior in very powerful ways, and it has two distinct dimensions. Structural context consists of the organization’s reporting relationships, monitoring and control mechanisms, and reward and punishment systems.31 The psychological context consists of the behavioral norms and situational pressures that underlie the decision-making process.

Structural context remains relatively stable over time, although seemingly subtle changes can have a profound impact on managerial behavior. Leaders typically do not change incentive schemes or alter the organization chart on a frequent basis. They certainly would not want to modify the structural context for each high-stakes decision that comes along. In that sense, it does not represent a lever that managers can change easily as a means of influencing how a particular decision-making process will unfold. However, leaders need to be mindful of how the structural context will shape individual and collective behavior during the process of problem solving and negotiation.

Psychological context can be more fluid. Situational pressures certainly vary across decisions. One might assume that variables such as time pressure and the sense of urgency remain outside an executive’s control. However, leaders typically have the opportunity to make time pressure more or less salient for their subordinates, perhaps by stressing the first-mover advantages that a competitor has achieved or even by establishing deadlines and milestones for the decision process. Leaders often heighten the sense of urgency within their organizations as a means of stimulating change.32 Naturally, accentuating these types of situational pressures can be risky. Stress, anxiety, and arousal can diminish the cognitive performance of decision makers.33 In particular, research on firefighters suggests that less-experienced individuals may be particularly susceptible to the negative effects of stress.34 Leaders must consider these risks as they accentuate situational pressures as a means of pushing for faster and higher performance.

Shared norms also may exhibit fluidity. They may differ across groups or units within the organization, and they can be altered explicitly as well as implicitly based on a leader’s behavior at the outset of a decision process. For instance, President Kennedy made a clear and explicit attempt to recast the behavioral norms that governed the actions of his advisers during the Cuban missile crisis.

What types of behavioral norms should a leader try to foster among participants in a decision-making process? As psychologist Richard Hackman has pointed out, many groups establish ground rules that seek to ensure smooth and harmonious interaction among participants. However, he stresses that being polite and courteous to one another—not interrupting others, for example—certainly does not ensure successful performance!35

What, then, should leaders strive to achieve when shaping the psychological context in which decisions are made? My colleague Amy Edmondson has shown how the creation of a climate of psychological safety stimulates collective problem solving and learning within organizations. She defines psychological safety as the “shared belief that a group is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.”36 It means that individuals feel comfortable that others will not rebuke, marginalize, or penalize them based upon what they say during a group discussion. When this shared belief exists, people will take a variety of interpersonal risks. They will share private information, admit mistakes, request assistance or additional data, surface previously undiscussable topics, and express dissenting views.37 Alan Mulally clearly established a new set of norms and a more psychologically safe environment at Ford. As described in Chapter 1, he acted quite explicitly to make it safe for people to share bad news and discuss problems openly.

It can be difficult to enhance psychological safety, particularly in hierarchical organizations characterized by substantial status differences among individuals. However, leaders can take steps to change the climate within their decision-making bodies. For instance, they can lead by example, acknowledging their own fallibility and admitting prior errors as a means of encouraging people to take interpersonal risks of their own. In an award-winning article titled “The Failure-Tolerant Leader,” Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes offer a plethora of examples of leaders who successfully broke down communication barriers and encouraged more divergent thinking in their organizations by openly talking about their own mistakes. For instance, they write, “The late Roberto Goizueta got years of one-liners from the New Coke fiasco that he sponsored. Admitting his mistake conveyed to his employees better than a hundred speeches or a thousand memos that ‘learning failures,’ even on a grand scale, were tolerated.”38

Leaders also can alter the language system typically employed within an organization. At times, commonly used words can attach a stigma to important learning behaviors, such as the admission of a mistake. For instance, Julie Morath, chief operating officer at Children’s Hospital and Clinics in Minneapolis, recognized that the language system in her organization attached a stigma to those who surfaced and discussed medical errors. Consequently, the organization could not improve patient safety, because many accidents or near-miss situations remained unidentified. Therefore, she created a list of “words to work by”—explicit do’s and don’ts regarding language—as a means of encouraging people to talk more openly about patient safety failures. Many employees noted that this effort helped to create a different atmosphere within the hospital and made people more willing to discuss and learn from failures.39

Communication

Communication mechanisms represent the third major lever that leaders can employ to enhance the quality of decision-making processes. Managers face a choice regarding the means of dialogue that they want to employ. In other words, they can determine how ideas and information are exchanged, as well as how alternatives are discussed and evaluated. To put it simply, leaders can choose between two distinct approaches to shaping the avenues of dialogue and communication. They can adopt a structured approach, dictating quite specifically the procedures by which participants should offer viewpoints, compare and contrast alternatives, and reach a set of conclusions. Alternatively, leaders can employ a largely unstructured approach, whereby they encourage managers to discuss their ideas freely and openly without adherence to well-defined procedures for how the deliberations should take place.

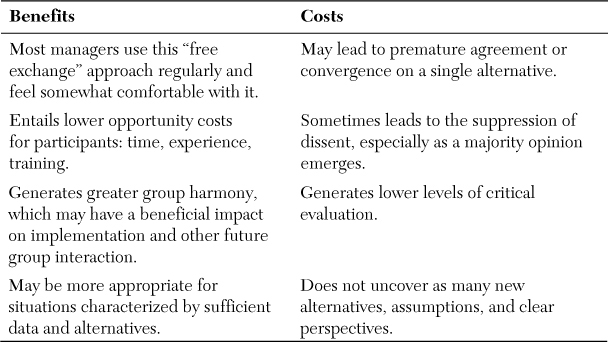

In a typical unstructured discussion, leaders guide the deliberations with a light touch. They encourage participants to engage in a free exchange of ideas and opinions, while ensuring that each person has an adequate opportunity to express his or her views. They encourage individuals to support their recommendations with sound logic and compelling data, and to try to convince others of the merits of their proposals while recognizing and respecting other perspectives. Ultimately, leaders encourage participants to reconcile opposing views and find common ground. Scholars have dubbed this approach the “consensus method” because of its emphasis on reaching a solution that all members can accept and because it tends to foster high levels of commitment and group harmony.40 See Table 2.2 for a summary of the benefits and costs of this approach to decision making.

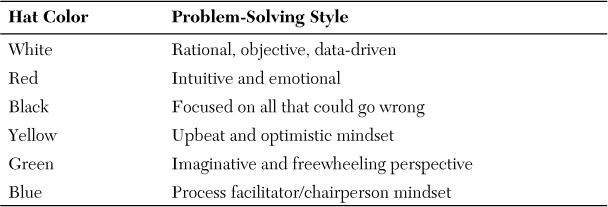

Too much convergent thinking, of course, can be a dangerous thing. Left to their own devices, groups all too often find themselves prematurely honing in on a single alternative. Therefore, leaders may need to introduce structured procedures to foster more creative and divergent thinking, as well as enhanced conflict and debate. Scholars and consultants have developed numerous mechanisms for organizing a discussion so as to promote a combination of imaginative and critical thinking. For instance, Edward de Bono invented a procedure called “Six Thinking Hats” to help groups consider a problem from multiple perspectives (see Table 2.3). With this technique, participants examine a decision using a variety of thinking styles. For instance, when “wearing the white hat,” individuals must employ an objective, data-driven approach to the decision. In contrast, those donning the “red hat” use intuition and emotion to examine the situation. Many groups find this technique useful as a way of pushing individuals to move beyond their usual problem-solving habits and routines, while encouraging everyone to think “outside the box.”41

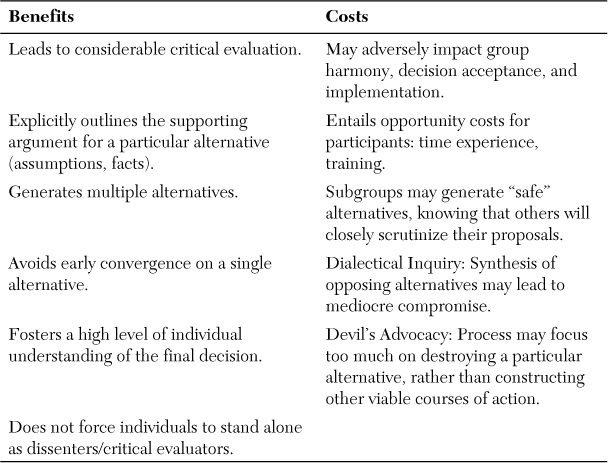

In the Cuban missile crisis, we see variants of two longstanding, very effective procedures for fostering divergent thinking and vigorous debate. Scholars have termed these approaches the “Dialectical Inquiry” and “Devil’s Advocacy” methods. Although the names may frighten you by implying rather complex and arcane procedures, there is no reason to be alarmed. These approaches, in fact, represent simple mechanisms for nurturing cognitive conflict. Each entails dividing a decision-making entity into two subgroups. In the Dialectical Inquiry method, one subgroup develops a detailed proposal and presents it to the others, preferably in written as well as oral form. They, in turn, generate an alternative plan of action. The two subgroups then debate the competing proposals, and they seek agreement on a common set of facts and assumptions before trying to select a course of action. Ultimately, the subgroups focus on reconciling divergent viewpoints and selecting a course of action consistent with the agreed-upon set of facts and assumptions. During this final stage of the process, the subgroups often generate new options as a means of moving beyond the original points of contention between the competing camps.

The Devil’s Advocacy approach works in a similar fashion. One subgroup develops a comprehensive plan of action and describes it to the other subgroup. However, the other subgroup does not attempt to generate competing options. Instead, it builds a detailed critique of the first subgroup’s proposal. Again, both subgroups should strive to present their arguments in written form and oral form for maximum effectiveness. The first subgroup then returns to the drawing board to modify its plan or perhaps invent a new option as a means of addressing the criticisms and feedback received. An iterative process of revision and critique then takes place until the two subgroups feel comfortable agreeing, at a minimum, on a common set of facts and assumptions. After reaching agreement on these issues, the subgroups work together to craft a plan of action that each side can accept.

These two structured decision-making procedures have many advantages (see Table 2.4).42 They tend to generate a great deal of cognitive conflict, and they stimulate the generation of multiple alternatives. Moreover, they help decision makers identify the flaws and weaknesses inherent in any plan, and they focus explicit attention on the underlying assumptions held by various participants. Naturally, one could achieve some of these same benefits by designating an individual to occupy a special role, either as the devil’s advocate or as the person responsible for inventing creative options. However, by directing people to work in subgroups, these procedures make it easier for an individual with dissenting views to put forth his ideas. After all, it tends to be quite difficult for one person, standing in opposition to the majority, to avoid the pressures for conformity that often emerge within groups.43 One should note, for instance, that Kennedy assigned two people to serve as devil’s advocates in the Cuban missile crisis, perhaps recognizing that a single critic/dissenter would find it quite difficult to confront the other members of Ex Comm.

Although these procedures offer many benefits for leaders interested in cultivating creative thinking and vigorous debate, they are not free of risks. Naturally, affective conflict can emerge. Subgroups may become so entrenched in their competing positions that they cannot reconcile divergent views and find common ground. Polarization of opinion may even occur, imperiling a leader’s ability to build commitment and shared understanding. Critics can become so effective at dissecting every proposal put forth by others that the decision makers become convinced that no identifiable course of action will meet the organization’s needs, resulting in a frustrating period of indecision. Alternatively, subgroups may adopt seriously flawed compromise solutions when faced with an impasse.

In light of these potential problems, leaders must use these procedures with great care, and they ought to assess whether a situation warrants taking such risks. Consider, for instance, a situation in which a leader knows that a strong coalition of managers supports a particular course of action, and he fears that they may stream roll the others into accepting this plan. Such a circumstance appears suitable for the application of one of the structured procedures outlined here. Similarly, a leader may be wary of how cohesive and seemingly like-minded his relatively homogenous group of subordinates has become. That particular state of affairs also may warrant the use of a structured mechanism for stimulating dissent and debate. In sum, leaders need not enter each decision process with the intent of empowering subordinates to shape and determine the means of dialogue, nor should they impose procedures in a top-down fashion regardless of the circumstances. They should strive to match the process of communication with the needs created by the situation at hand.44

Control

When shaping how strategic choices are made, the final lever at a leader’s disposal concerns the crafting of his distinctive position in the decision process. A leader must decide the extent to which he intends to control both the process and the content of the decision. Perhaps most importantly, he must determine whether to “step out of the room” at times, as John Kennedy did during the Cuban missile crisis, to encourage frank and open discussion. In terms of his active participation, the leader has choices to make along four dimensions. First, he must decide how and when to introduce his own views into the deliberations. Second, he needs to consider the extent and manner in which he will intervene actively to direct discussion and debate. Third, the leader has an opportunity to play a special role during the decision process. For instance, he might consistently occupy the position of the “futurist,” looking far beyond the time horizon considered by his advisers. Alternatively, he might personally adopt the responsibility for playing the devil’s advocate. Finally, the leader must determine how he will attempt to bring closure to the process and reach a final decision.

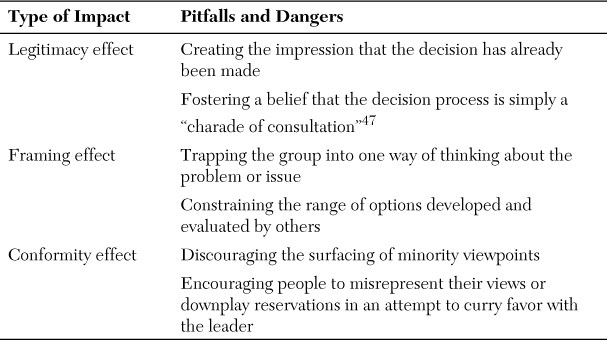

Leaders must choose whether to reveal their views at the start of a decision process. When a leader begins by arguing for a particular course of action, he shapes the way that others define the problem at hand, search for alternatives, and express their ideas and opinions. In some cases, it creates a perception that the leader has already made up his mind and, therefore, that the team members do not have a genuine opportunity to influence the final decision. In fact, the early declaration of a leader’s position may have several adverse effects on the decision-making process (see Table 2.5).45

A leader may create the impression that the decision has already been made and that he is unlikely to change his mind. In this case, team members may become frustrated if they believe that the leader simply wants to create the appearance of a consultative process. In addition, he may frame the issue in a manner that constricts the range of alternatives that are generated by participants. Decision frames are “mental structures people create to simplify and organize the world.”46 Frames shape the way that people think about a problem. They can be useful because they enable individuals to cope with complexity. However, frames also constrain the range of options that are considered and distort how people interpret data. When a leader announces his position in the early stages of a decision process, he imposes a particular frame and, consequently, may inhibit the group from exploring other ways of thinking about the problem. Finally, announcing an initial position may discourage individuals from expressing dissent and offering minority views. As pointed out earlier, when a leader states his opinion forcefully, it can be difficult for others to disagree with him publicly.

A leader can avoid these detrimental effects by choosing not to reveal his preferred solution during the early stages of the group discussions. Alternatively, a leader may offer a tentative proposal but emphasize that he is quite open to differing views and willing to modify his position if superior solutions emerge during the discussion. In either case, the leader should stress that he will try to keep an open mind as he listens to each person’s ideas and recommendations. This approach will foster a belief that participants have the potential to influence the final decision in a substantial way.

When deliberations begin, a leader may or may not intervene actively to direct the pattern of participation and involvement. My colleagues Amy Edmondson and Michael Watkins and I have distinguished between an activist model of process facilitation/intervention and a more laissez-faire approach.48 In the interventionist model, leaders guide the timing and extent of participation by various individuals involved in the deliberations. They invite specific participants to offer their views, and they inquire repeatedly as to where individuals stand on specific topics. They pose follow-up questions for clarification purposes and play back people’s statements to ensure that they have been interpreted correctly. Moreover, they emphasize points that they deem important, but which perhaps have been a bit misunderstood or marginalized. The contrasting leadership mode calls for a much less directive approach to discussion facilitation. Leaders allow participants to enter and exit the deliberations more freely, and they do not try to control where people focus their attention.

The activist mode functions quite effectively when participants in a decision process possess a great deal of private information (that is, data to which others do not have access and about whose existence they may not even be aware). Why is this so? Group members tend to discuss commonly shared information a great deal during decision-making processes while paying less attention to privately held data.49 The failure to surface this private information can lead to suboptimal, or even fundamentally flawed, decisions. By intervening actively, leaders can ensure that people have ample opportunity to disclose unshared information and that participants have an adequate chance to recognize the revelation of important private information.50 Because the activist mode can create discomfort among some participants and perhaps slant the discussion in unforeseen ways, leaders should be cautious about its utilization. For those reasons, leaders should adopt a much less interventionist approach when all participants share a common pool of pertinent information and expertise.

In addition to deciding how to facilitate the decision process, leaders must determine whether they want to occupy a special role during the deliberations. Kathleen Eisenhardt’s research suggests that a useful technique for nurturing healthy debate is “cultivation of a symphony of distinct roles.”51 She found that effective senior management teams tend to fall into habitual patterns of behavior in which certain members occupy informal, yet commonly understood, roles on a rather consistent basis. Leaders not only can encourage subordinates to take on certain roles, they can occupy those positions themselves if necessary.

Eisenhardt and her colleagues found that a number of management teams have an individual who serves as the “futurist”—a person who acts as a visionary who pushes the team to examine long-term strategic trends and market developments when the team gets bogged down in short-term operational issues. Others serve repeatedly as “steadying forces” who temper overconfidence and remind people not to get caught up in circumstances of “irrational exuberance.” Leaders can occupy two other roles as well. They may serve as a devil’s advocate, and they can be the person pushing frequently for an “action orientation”—challenging inertia and indecisiveness while reminding people constantly of the recent moves that competitors have made to establish a market advantage. Although Eisenhardt’s work stresses the permanence of role structures within some teams, leaders need not always occupy the same role in every process to be effective decision makers. They may find it useful to shift roles over time as different threats and opportunities emerge.

Perhaps the most important dimension of control concerns how the leader intends to bring closure to the decision-making process. Edmonson, Watkins, and I identify two distinct approaches to selecting a course of action along with a group of advisers. On the one hand, the leader may serve as a mediator, “trying to bring team members with different views together to arrive at a mutually acceptable solution.”52 The leader does not impose his will on the group in this mode; rather, he facilitates deliberations in an effort to find common ground among multiple parties. The leader may weigh in on the matter with his own views, but he does not use his power and rank to dictate the outcome. In contrast, the leader may adopt an arbitrator orientation, “listening to competing arguments and selecting the course of action that he believes is best for the organization.”53 President Kennedy operated in this mode during the Cuban missile crisis. He made it clear that he wanted to hear the opposing sides present their proposals to him, and then he would go off on his own to evaluate the arguments and make a final decision.

A leader may begin by trying to serve as a mediator among players with competing goals and interests, and then shift to the arbitrator orientation if the group cannot reach an agreement on a mutually acceptable course of action. Indeed, Eisenhardt’s research suggests that many effective leaders employ just such a blended approach. She described the phenomenon as “consensus with qualification.” In this mode, leaders try to bring people along until they can find a solution that everyone finds satisfactory. If time runs short, tempers flare repeatedly, or the parties simply cannot reach common ground, the leader can take sole responsibility for selecting a course of action.54

When deciding how to operate in a particular situation, executives must consider a number of factors, including their personal leadership style, the extent to which time pressure exists, the personalities of the parties involved, and the extent to which the interests of various players are diametrically opposed. Perhaps more important than selecting the optimal mode for a given situation, a leader needs to be very clear about how he intends to behave when disagreements emerge and a decision must be made. Individuals can become readily disenchanted if a leader’s approach to reaching closure does not conform to their prior expectations. Providing a clear process roadmap in this regard serves a leader well if he hopes to build commitment among all parties involved.

The Power to Learn

President Kennedy demonstrated during the Cuban missile crisis that a leader has many levers available to affect the quality of a high-stakes decision-making process. Moreover, he showed that leaders have the opportunity to learn from prior failures and use those lessons to modify the process choices that they make in the future. Of course, it takes a certain mindset to acknowledge one’s failures and invite others to provide advice regarding how to change going forward. The culture in many organizations also inhibits productive learning. As organizational learning expert David Garvin has noted, many firms have a culture that regards learning as an activity that distracts resources and attention from the “real work” that needs to be done.55

President Kennedy’s actions demonstrate another important distinction regarding the learning process that takes place after critical choices are made. When decision failures occur, many executives focus on the issues involved, and they seek to identify the mistaken judgments and flawed assumptions that they made. However, many leaders do not push further to investigate why they made these errors. Too many of them engage only in content-centric learning. By that, I mean that they search for lessons about how they will make a different decision when faced with a similar business situation in the future. For instance, an apparel executive reported to me about a decision to move into a new product category. When the decision proved to be a failure, he reflected back and concluded that the firm did not have the skills and capabilities to succeed in a fashion-driven market segment. He resolved to never invest in a fashion-oriented business again.

Kennedy adopted a different learning orientation. He engaged in process-centric learning, meaning that he thought carefully about why the Bay of Pigs decision-making procedures led to mistaken judgments and flawed assumptions. He did not simply draw a series of conclusions about how to handle future choices regarding U.S. policy toward Cuba or the support of rebel movements in other countries. He searched for lessons about how to employ a different process when faced with tough choices in the future.56

The power of process-centric learning can be remarkable. Consider that apparel executive once again. His conclusion about fashion-driven product categories proved to be a solid example of productive content-centric learning. Yet he did not rest having derived those lessons from the failure. Reflecting back, that manager also concluded that he had become too emotionally attached to his original idea, and consequently he discounted a series of warning signs, focused on confirmatory information, and failed to listen to dissenting voices. How many times did that apparel executive apply the lesson regarding fashion-driven product categories? The answer: much less than the number of occasions on which that same executive benefited by adopting a different approach to the collection and interpretation of information during a high-stakes decision-making process.

Finally, when thinking about learning from past decisions, consider how you select the past experiences upon which to reflect. The conventional wisdom suggests that we learn more from our failures than from our successes. In reality, people learn effectively when they compare success and failure. Tel Aviv University scholars Schmuel Ellis and Inbar Davidi performed an interesting study regarding how the Israeli military forces tried to learn from past experiences. They compared soldiers who performed post-event lesson-learned exercises after their failures with those who analyzed all past experiences, good or bad. These scholars found that the soldiers who compared and contrasted successes and failures performed better on subsequent missions than those who studied only failures. These soldiers developed more hypotheses about the drivers of performance, and they constructed richer mental models of cause and effect.57

The Prepared Mind

Louis Pasteur once said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Indeed, the prepared mind of an effective leader thinks carefully about the type of decision-making process to employ before he immerses himself in a particular business problem. Moreover, the prepared mind searches constantly for the opportunity to learn from past successes and failures, and then improves the way it goes about making crucial choices in the future.

Endnotes

1. T. Sorensen. (1966). Kennedy. New York: Bantam. p. 346.

2. D. Halberstam. (1972). The Best and the Brightest. New York: Random House. As an example of the caliber of the intellects gathered in the White House at that time, consider McGeorge Bundy—Kennedy’s national security adviser. He received tenure at Harvard after only two years on the faculty, and he was appointed dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences in 1953 at the remarkably young age of 34.

3. This account of the Bay of Pigs decision draws upon two critical sources: A. Schlesinger, Jr. (1965). A Thousand Days. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; I. Janis. (1982). Groupthink. Second edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

4. Schlesinger. (1965). p. 250.

5. The Bay of Pigs decision represents one of the classic cases of “groupthink” described by Irving Janis. According to Janis, groupthink is “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ striving for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.” Janis. (1982). p. 9.

6. Former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s visit to my class in the spring of 2005.

7. Ibid.

8. For a discussion of the changes Kennedy made after the Bay of Pigs failure, see Janis. (1982). In addition, see Schlesinger. (1965); R. Johnson. (1974). Managing the White House: An Intimate Study of the Presidency. New York: Harper & Row; A. George. (1974). “Adaptation to stress in political decision making: The individual, small group, and organizational context,” in G. Coelho, D. Hamburg, and J. Adams, eds., Coping and Adaptation. New York: Basic Books.

9. For a detailed, firsthand account of the decision making that took place during the Cuban missile crisis, see R. Kennedy. (1969). Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York: W.W. Norton.

10. Former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s visit to my class in the spring of 2005.

11. Janis. (1982). p. 141.

12. This analysis of the two decisions draws heavily upon a discussion in D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (2001). “What you don’t know about making decisions,” Harvard Business Review. 79(8): pp. 108–116.

13. Schlesinger. (1965). p. 248.

14. www.fastcodesign.com/1669936/meetings-are-a-skill-you-can-master-and-steve-jobs-taught-me-how, accessed June 13, 2012.

15. www.thinkwithgoogle.com/quarterly/speed/start-up-speed-kristen-gil.html, accessed January 24, 2012.

16. D. K. Williams. (2012). “Brad Smith, Intuit CEO: ‘How to be a great leader: Get out of the way’” www.forbes.com/sites/davidkwilliams/2012/06/25/growing-a-company-qa-with-brad-smith-intuit-ceo-remove-the-barriers-to-innovation-and-get-out-of-the-way/, accessed July 11, 2012.

17. M. Guadalupe, H. Li, and J. Wulf. (2012). “Who Lives in the C-Suite? Organizational Structure and the Division of Labor in Top Management,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 12-059.

18. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2928, accessed August 29, 2011.

19. The material that follows draws heavily upon empirical research reported in M. Roberto. (2002). “The stable core and dynamic periphery in top management teams,” Management Decision. 41(2): pp. 120–131.

20. For more on the filtering of information and its potentially detrimental effect on organizational decision making, see A. George. (1980). Presidential Decision Making in Foreign Policy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. The book provides an excellent analysis of the dynamics of decision making at the most senior levels of government, but the conceptual ideas also apply to many other types of complex organizations.

21. For a conceptual analysis of why NASA downplayed the risks associated with the foam strike that took place during the Columbia’s launch in January 2003, see A. Edmondson, M. Roberto, R. Bohmer, E. Ferlins, and L. Feldman. (2005). “The recovery window: Organizational learning following ambiguous threats,” in M. Farjoun and W. Starbuck, eds., Organization at the Limit: NASA and the Columbia Disaster. London: Blackwell. In that chapter, we define the concept of a recovery window as the finite time period between a threat and a major accident (or prevented accident) in which constructive collective action is feasible. We argue that executives do not downplay threats such as the foam strike simply because of negligence or incompetence; instead, we propose that organizations are naturally predisposed to downplay threats when they are ambiguous. That predisposition to under-respond derives from certain factors related to human cognition, team design and dynamics, and organizational structure and culture. The paper also outlines an alternative, learning-oriented approach to addressing ambiguous threats that leaders can employ to reduce the risk of catastrophic failures.

22. For more about involving people responsible for implementation in the strategic decision-making process, see L. J. Bourgeois and K. Eisenhardt. (1988). “Strategic decision processes in high velocity environments: Four cases in the microcomputer industry,” Management Science. 34(7): pp. 816–835. The authors explain how the CEOs of successful firms in their study tended to consult people responsible for implementation during the decision process, and in particular, involved them deeply in the development of execution triggers, defined as the stream of “subsequent decisions to be triggered by a schedule, milestone, or event” in the initially chosen course of action (pp. 829–830).

23. K. Eisenhardt. (1989). “Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments,” Academy of Management Journal. 12: pp. 543–576.

24. Eisenhardt. (1989). p. 559.

25. M. Roberto. (2002). “The stable core and dynamic periphery in top management teams,” Management Decision. 41(2): pp. 120–131.

26. Irving Janis and Leon Mann describe the apprehension and anxiety that individuals sometimes experience before making a consequential decision as “anticipatory regret.” For a detailed discussion of the concept and its impact on decision makers, see I. Janis and L. Mann. (1977). Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment. New York: Free Press.

27. Eisenhardt. (1989).

28. D. K. Goodwin. (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon and Schuster.

29. For a thoughtful summary and analysis of the research on demographic heterogeneity, see K. Williams and C. O’Reilly. (1998). “Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research,” in B. Staw and R. Sutton, eds., Research in Organizational Behavior. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 77–140. It should be noted that many scholars have criticized the literature on top management team demographics for reasons beyond the fact that it has produced a series of conflicting findings. For instance, my 2002 article in Management Decision shows that strategic choices are not made by a stable top team within a firm, but by a dynamic blend of participants depending on the situation at hand. Therefore, it becomes hard to argue that the demographic attributes of the top team can accurately predict organizational outcomes. Other scholars have pointed out that most demographic studies cannot determine the direction of causality, pay insufficient attention to intervening team processes which some data suggest matter more than structural attributes, and fail to account for situation-specific factors that affect team process and performance. For an insightful critique of the research on top management team demographics, see A. Pettigrew. (1992). “On studying managerial elites,” Strategic Management Journal. 13: pp. 163–182.

30. Leaders also should consider the power structure within a top management team and its effects on the decision-making process. Recent studies suggest that scholars who have focused on demographic heterogeneity may not have accounted sufficiently for power imbalances within top management teams. For an insightful study that looks at both power structure and demographics within senior teams over time, see P. Pitcher and A. Smith. (2001). “Top management team heterogeneity: Personality, power, and proxies,” Organization Science. 12(1): pp. 1–18.

31. Joseph Bower introduced the concept of structural context in his study of resource allocation processes within multidivisional firms. See J. Bower. (1970). Subsequent studies by many of Bower’s doctoral students have further explored how structural context shapes strategic decision making within firms. For example, see C. Christensen and J. Bower. (1996). “Customer power, strategic investment, and the failure of leading firms,” Strategic Management Journal. 17: pp. 197–218.

32. J. Kotter and D. Cohen. (2002). The Heart of Change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

33. Janis and Mann. (1977).

34. F. Fiedler. (1992). “Time-based measures of leadership experience and organizational performance: A review of research and a preliminary model,” Leadership Quarterly. 3(1): pp. 4–23.

35. J. R. Hackman. (2002). Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

36. A. Edmondson. (1999). “Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly. 44: p. 354.

37. For more details regarding the impact of psychological safety on team learning and performance, see A. Edmondson, R. Bohmer, and G. Pisano. (2001). “Disrupted routines team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals,” Administrative Science Quarterly. 46: pp. 685–716; A. Edmondson. (2003). “Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams,” Journal of Management Studies 40(6): pp. 1419–1452.

38. R. Farson and R. Keyes. (2002). “The failure-tolerant leader,” Harvard Business Review. 80(8): p. 67.

39. A. Edmondson, M. Roberto, and A. Tucker. (2002). “Children’s Hospital and Clinics,” Harvard Business School Case No. 302-050.

40. Experimental studies have been conducted that compare the different group decision-making procedures discussed in this section (Consensus vs. Dialectical Inquiry vs. Devil’s Advocacy). The analysis in these pages draws upon the results of that research. For instance, see D. Schweiger, W. Sandberg, J. Ragan. (1986). “Group approaches for improving strategic decision making,” Academy of Management Journal. 29: pp. 51–71. My colleague David Garvin and I have developed a set of group exercises, based on these experimental studies, that enable students to experience these different approaches to decision making, and to compare and contrast their evaluations of the three methods. See D. Garvin and M. Roberto (1996). Decision-Making Exercises (A), (B), and (C). Harvard Business School Cases No. 397-031, 397-032, 397-033. The teaching note accompanying those exercises examines these three methods in depth. Moreover, we discuss these approaches in D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (2001). “What you don’t know about making decisions,” Harvard Business Review. 79(8): pp. 108–116.

41. E. De Bono. (1985). Six Thinking Hats. Boston: Little, Brown.

42. For a more in-depth discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of each method, see the following articles: D. Schweiger, W. Sandberg, J. Ragan. (1986); R. Priem, D. Harrison, and N. Muir. (1995). “Structured conflict and consensus outcomes in group decision making,” Journal of Management, 21(4): pp. 691–710; A. Murrell, A. Stewart, and B. Engel. (1993). “Consensus vs. devil’s advocacy,” Journal of Business Communication. 30(4): pp. 399–414.

43. Recall, for instance, the finding of Solomon Asch in his famous experiments conducted in the early 1950s. He exposed an individual to a group that was instructed to unanimously articulate a position in clear violation of the facts. The individual often experienced enormous pressures to conform. However, when the experimenter introduced a second person unaware of the experimenter’s instructions for the majority, Asch found that the two individuals tended to be less likely to succumb to conformity pressures. See S. Asch. (1951). “Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments,” in H. Guetzkow, ed., Groups, Leadership, and Men. New York: Russell and Russell. pp. 177–190.

44. Priem, Harrison, and Muir. (1995); Murrell, Stewart, and Engel. (1993).

45. I have created a set of group exercises that explore the impact of a leader announcing an initial position at the outset of a meeting. See M. Roberto. (2001). “Participant and Leader Behavior: Group Decision Simulation (A)-(F),” Harvard Business School Case Nos. 301-026, 301-027, 301-028, 301-029, 301-030, 301-049. The teaching note accompanying those exercises describes the legitimacy, conformity, and framing effects, and it provides sample data pertaining to the impact that taking an initial position has on perceptions of fairness, levels of commitment, etc.

46. J. Russo and P. Schoemaker. (1989). Decision Traps: The Ten Barriers to Brilliant Decision-Making and How to Overcome Them. New York: Fireside. p. 15.

47. My colleague, Michael Watkins, has coined the phrase “charade of consultation.”

48. A. Edmondson, M. Roberto, and M. Watkins. (2003). “A dynamic model of top management team effectiveness: Managing unstructured task streams,” Leadership Quarterly. 14(3): pp. 297–325.

49. G. Stasser and J. Davis. (1981). “Group decision making and social influence: A social interaction model,” Psychological Review (88): pp. 523–551; G. Stasser and W. Titus. (1985). “Pooling of unshared information in group decision making: Biased information sampling during discussion,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. (48): pp. 1467–1478; G. Stasser. (1999). “The uncertain role of unshared information in collective choice,” in L. Thompson, J. Levine, and D. Messick, eds., Shared Cognition in Organizations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 49–69.

50. An experimental study by University of Illinois–Chicago Professor Jim Larson and his colleagues supports the proposition that a more activist leadership style may induce people to share more private information. See J. Larson, P. Foster-Fishman, and T. Franz. (1998). “Leadership style and the discussion of shared and unshared information in decision-making groups,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 24(5): pp. 482–495.

51. K. Eisenhardt, J. Kahwajy, and L. J. Bourgeois. (1998). “Conflict and strategic choice: How top management teams disagree,” in D. Hambrick, D. Nadler, and M. Tushman, eds., Navigating Change: How CEOs, Top Teams, and Boards Steer Transformation. p. 141–169. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

52. Edmondson, Roberto, and Watkins. (2003). p. 312. We draw our definitions of mediation and arbitration from D. Lax and J. Sebenius. (1986). The Manager as Negotiator: Bargaining for Cooperation and Competitive Gain. New York: Free Press.

53. Edmondson, Roberto, and Watkins. (2003). p. 312.

54. Eisenhardt. (1989). Note that authors, researchers, and managers have used the term consensus in many different ways. It might be useful at this point to recall that we have defined consensus in this book as the combination of commitment and shared understanding. That definition differs from the use of the term employed by Eisenhardt, in which it refers to agreement among group members. It is important to point out that one could employ the approach to reaching closure described by Eisenhardt, which many leaders do, but not achieve high levels of commitment and common understanding.

55. D. Garvin. (2000). Learning in Action: A Guide to Putting the Learning Organization to Work. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

56. It should be noted that former President Dwight Eisenhower may have encouraged President Kennedy to engage in process-centric learning after the Bay of Pigs failure. In late April 1961, Eisenhower traveled to Camp David, at Kennedy’s request. Kennedy explained his views regarding the causes of the failure: faulty intelligence, tactical mistakes, poor timing, and so on. According to historian Stephen Ambrose, Eisenhower offered the following inquiry: “Mr. President, before you approved this plan did you have everybody in front of you debating the thing so you got pros and cons yourself and then made your decision, or did you see these people one at a time?” Apparently, Kennedy acknowledged that he and his advisers had not debated the plan openly in a full team meeting. See S. Ambrose. (1984). Eisenhower: The President, Volume 2. New York: Touchstone. p. 638.

57. S. Ellis and I. Davidi. (2005). “After-event reviews: Drawing lessons from successful and failed experience,” Journal of Applied Psychology. 90(5): pp. 857–871.