5. Keeping Conflict Constructive

“Anybody can become angry, that is easy; but to be angry with the right person, and to the right degree, and at the right time, and for the right purpose, and in the right way, that is not within everybody’s power. That is not easy.”

—Aristotle

In the 1950s, comedian Sid Caesar starred in one of the most popular programs on television—Your Show of Shows. The program’s success may be credited to the remarkable team of comedy writers that collaborated to write each week’s script. Many of the team members became comedic legends in their own right—Mel Brooks, Larry Gelbart, Neil Simon, Woody Allen, and Carl Reiner, to name just a few. They spent day and night together in the “Writers’ Room”—a place where the ideas flowed freely, people competed fiercely with one another, and creative genius emerged from contentious disagreement.1

Producer Max Liebman often stressed that “from a polite conference comes a polite movie.”2 The young writers certainly took his advice to heart. In his autobiography, Sid Caesar recalled the mighty struggles that took place in the Writers’ Room: “Chunks of plaster were knocked out of walls; the draperies were ripped to shreds; Mel Brooks frequently was hanged in effigy by the others.”3 Nevertheless, the writers produced legendary skits week after week, worked effectively together for years, and remained friends and collaborators for decades. Somehow, the heated arguments represented what writer Mel Tolkin described as “good creative anger.”4

Imagine, however, if a stranger walked into the Writers’ Room one day, not knowing anything about the team’s history, and he witnessed the madness that Caesar and others have described. Naturally, one might have a hard time believing that this group could produce such a spectacular show or that the members would enjoy working together for years. Tomorrow, if you tried to emulate this pattern of behavior with your management team, you might very well have a disaster on your hands. However, in the Writer’s Room, the heated nature of the conflict did not become a liability for the group. With astute leadership over a long period of time, Caesar had created an atmosphere, as well as a creative decision-making process, in which the writers could argue in a passionate yet productive fashion. He had created a context in which hanging a team member in effigy did not represent aberrant or dysfunctional behavior, but rather a healthy and “normal” way of coping with cognitive conflict. This chapter examines how leaders can act before, during, and after a decision-making process to ensure that conflict within their management teams remains vigorous yet constructive. This chapter does not advocate direct emulation of the antics of Caesar and friends, but we develop a set of principles that applies in settings ranging from the Writers’ Room to the boardroom.

Diagnosing the Debate

In many organizations, debates become dysfunctional before the leader recognizes the warning signs. Diagnosing these situations as they unfold is a critical leadership capability. How does a leader discern whether a passionate debate among his advisers and subordinates stands on the verge of becoming dysfunctional? Imagine two scenarios. In one instance, individuals continue to raise interesting questions that provoke novel lines of collective discovery. People try to understand others’ positions, and they remain open to new ideas. The search for creative new options persists. In another scenario, people repeat the same worn-out arguments, opposing camps have dug in their heels, and the loudest voices dominate the discussion. People stop trying to comprehend one another; they simply strive to persuade. Conflict proves constructive as long as it propels a process of collective problem-solving and exploration. It serves little purpose if people simply want to prove their point rather than discover solutions collectively.5

Leaders need to be especially attuned to the reasons opposing camps have formed. Sometimes, people simply take different sides in a debate, and they become very entrenched in their positions on the issues. On other occasions, polarized camps form for different reasons that may pose more serious problems. Researchers have shown that teams sometimes fracture along what they call “fault lines.” In other words, individuals affiliate with team members who are similar to them along certain demographic attributes (such as gender, race, functional background, education) or because members work in different business units or geographic locations. As a result, leaders may find that multiple small cells have formed within a team, and friction has emerged between these camps. When fault lines emerge, teams can have a very hard time keeping conflict constructive.6

As debates drag on, leaders must be aware that their well-intentioned efforts to maintain a constructive dialogue between people with entrenched positions may do more harm than good. For instance, many leaders believe that they can reach a compromise between opposing camps if they simply keep the debate focused on the facts, while ensuring that everyone has equal access to relevant information. Indeed, my research, as well as a number of studies by Kathleen Eisenhardt and her colleagues, shows that the tactic of focusing on facts tends to be helpful during contentious debates.7 However, unintended consequences may arise when two groups with opposing views attempt to interpret a common set of information.

One fascinating experimental study highlights the hidden dangers of “fact-based problem solving.” Psychologists Charles Lord, Lee Ross, and Mark Lepper once asked a group of death-penalty supporters to examine two empirical studies regarding the deterrent efficacy of capital punishment. One study confirmed their existing beliefs, whereas the other offered disconfirming data. The researchers also presented the two studies to a group of death-penalty opponents. After each side analyzed identical sets of data, their views on capital punishment did not converge. In fact, increased polarization of opinion occurred! What happened? People assimilated the data in a biased manner, placing more weight on the evidence that supported their initial position. As the researchers commented, it seems that people “are apt to accept confirming evidence at face value while subjecting disconfirming evidence to critical evaluation.”8

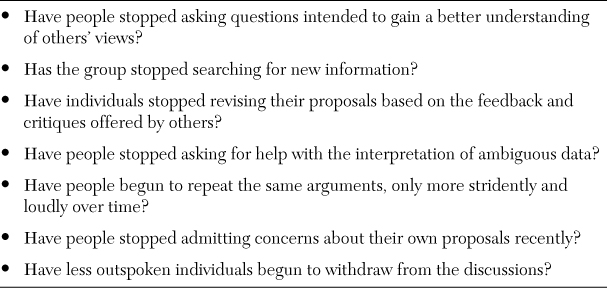

The lesson for leaders is clear: Focusing on the facts does not always yield the intended results. Polarization can occur even when a group appears to be pursuing an “objective and rational” decision-making process. Not surprisingly, a number of warning signs often appear as debates begin to become dysfunctional. By asking themselves a set of simple questions, such as those found in Table 5.1, leaders can monitor the “health” of a debate and intervene before too much damage is done.

Affective Conflict

The most glaring sign of trouble during a debate may be the emergence of affective, or interpersonal, conflict. This conflict often goes hand in hand with the emergence of dueling camps and the polarization of views. People may cross the line from issue evaluation to personal criticism in these situations. Perception often matters more than intention in these circumstances. Individuals may not intend to attack others personally when discussing a contentious issue. However, a blunt and forceful critique of others’ ideas can stir feelings of distress and anxiety, stimulate defensive behavior, and spark emotional counterattacks.

As noted in Chapter 1, “The Leadership Challenge,” most managers have a difficult time engaging in task-oriented debate without sparking anger, personality clashes, and personal friction. That appears to be true whether we observe managers making decisions in real organizations, performing experimental studies, or asking students to evaluate their experiences after debating one another in a simple classroom exercise.9 The latter results may be the most startling. Affective conflict does not emerge simply because the stakes are high or because managers have a great deal of political capital tied up in a particular issue. It emerges even when individuals seemingly have little to gain or lose, at least of a material nature, by virtue of the outcome of a debate.10

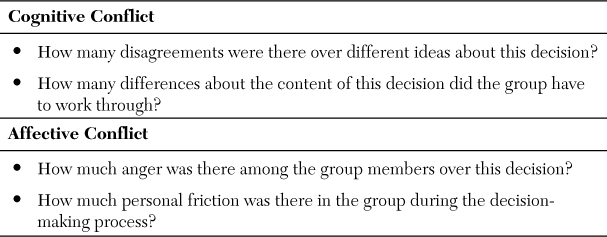

How does a leader know whether he has managed conflict effectively during a decision process? A simple diagnostic exercise can be helpful. Think for a moment about a recent high-stakes decision that you have made. Now consider the questions shown in Table 5.2, and ask others involved in that decision to share their responses with you. Be sure to ask people to cite specific examples of affective conflict and to explain why they believe interpersonal disagreement emerged.

Source: A. Amason. (1996). “Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making,” Academy of Management Journal. 39(1): pp. 123–148.

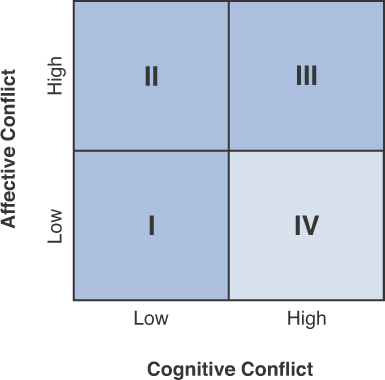

You may find it helpful to present the group with the matrix shown in Figure 5.1, and ask the group to locate the decision-making process in one of the four quadrants. Perhaps some of you will be fortunate enough to discover that the group believes the process fits in Quadrant 4. Unfortunately, my research, teaching, and consulting work indicate that most groups find themselves in one of the other three quadrants. Each of those, of course, tends to lead to suboptimal decision making, either because not enough dissent has surfaced (Quadrant I) or too much interpersonal tension has emerged (Quadrants II and III). If you find that many of your decision processes fit in one of these three quadrants, do not be disheartened. Getting to Quadrant IV might not be easy, but leaders can take action to move their teams in that direction. Diagnosing the problem—and developing a shared understanding of it within your organization—represents an important first step in the improvement process. Let’s now turn to the strategies that leaders may employ to manage conflict effectively.

Curbing Affective Conflict

Sometimes people believe that regulating affective conflict entails a dispassionate, unbiased approach to decision making. Yet eliminating passion and emotion from the decision-making process may not only be nearly impossible but also counterproductive. In the Writer’s Room, Caesar’s team achieved success in part because everyone came to the table with great zeal and excitement for their ideas. The same can be said for the process of creating new video games at Electronic Arts. Bruce McMillan, a former senior executive at the firm, explains that passion and emotion play a critical role in business decisions. He wants proponents of an idea to display ardor and enthusiasm because he knows that those feelings will fuel a powerful drive to execute the product development project successfully. One cannot—and should not—simply ask people to put aside their passion. McMillan likens the situation to a disagreement with your wife. As he says, “Imagine saying to your wife, ‘Honey, let’s take the emotion out of this issue for a moment.’ What do you think her reaction would be?”11 Effective leaders channel others’ emotions; they do not eliminate them.

Indeed, emotions and feelings can play a critical role in helping us make better decisions. Sometimes we make an intuitive judgment without quite knowing why we have arrived at that conclusion. Our brain may recognize a threat or see a problem. That recognition triggers a certain feeling or emotion. Those feelings may drive us toward making a very good choice in difficult and ambiguous circumstances, even before we have a conscious understanding of the situation.

Army researcher Steve Burnett has studied how hundreds of soldiers detected improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in Iraq and Afghanistan. Some men and women outperformed others. These soldiers could not always explain why they made certain choices. Sergeant Edward Tierney described one incident: “My body suddenly got cooler; you know, that danger feeling.” When asked to explain what tipped him off about a nearby roadside bomb, he said, “I can’t point to one thing. I just had that feeling you have when you walk out of the house and know you forgot something.”12

University of Southern California Professor Antonio Damasio has conducted landmark studies on the role of emotion in decision making. He explained why emotions cannot be dismissed simply as elements of an irrational decision-making process:

Not long ago, people thought of emotions as old stuff, as just feelings—feelings that had little to do with rational decision making, or that got in the way of it. Now that position has reversed. We understand emotions as practical action programs that work to solve a problem, often before we’re conscious of it. These processes are at work constantly, in pilots, leaders of expeditions, parents, all of us.13

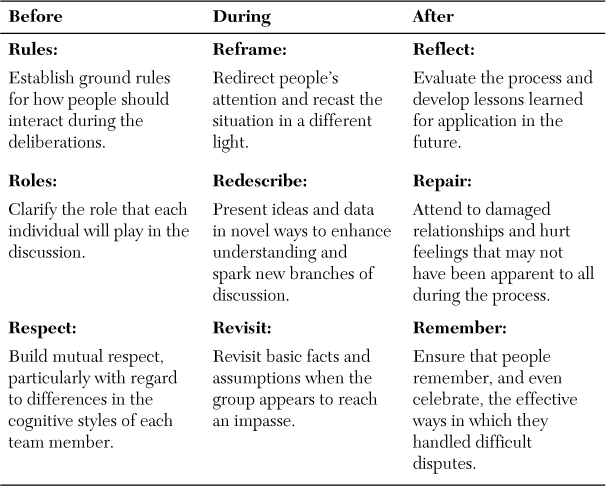

How then does one regulate affective conflict without squelching people’s passion for their ideas or downplaying intuitive feelings? A successful approach involves a concrete set of actions undertaken before, during, and after the decision-making process (see Table 5.3). Before a group begins to debate an issue, effective leaders establish ground rules, clarify roles and responsibilities, and build mutual respect among team members. These preliminary steps create the context in which people will behave. During the deliberations, as affective conflict begins to bubble up, leaders can reframe the debate, redescribe important ideas in novel ways, and revisit underlying facts and assumptions to help the group resolve disputes and break stalemates. After the decision process, effective leaders take the time to reflect and learn, repair damaged relationships or hurt feelings, and ensure that people remember the ways in which they worked through disputes constructively. Each of these steps requires careful forethought on the part of leaders; they must prepare themselves—and their teams, in some instances—to employ these strategies. Once again, we find that making upfront process choices enhances a leader’s effectiveness.

Before the Debate

What can leaders do before people commence deliberations on an issue? The steps outlined in this section often serve to raise shared awareness about several dimensions of interpersonal and group behavior. That awareness tends to facilitate conflict management.

Ground Rules

When a group becomes engaged in a difficult dispute, individuals often revert to certain well-established routines—habitual patterns of behavior that have become deeply ingrained in the organizational culture over time. For instance, when Paul Levy took over as CEO at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in January 2002, he found that the department heads—highly accomplished doctors who were world leaders in their respective fields—often behaved very consistently, yet unproductively, when contentious issues arose. They remained silent during the CEO’s staff meeting when, in fact, they objected to a course of action under consideration. Then they tried to undercut that plan outside the meeting, often lashing out at administrators who did not agree with their concerns. Affective conflict tended to swamp task-oriented disagreement.

Levy needed to disrupt this ineffective routine. He needed to override the “unwritten rules” that typically guided behavior. To accomplish that, he took a number of steps, beginning with the distribution of a set of “meeting rules” that described how he expected people to behave within his senior team.14 Note the similarity to the approach employed by Steven Caufield, as described in the example in Chapter 4, “Stimulating the Clash of Ideas.” He used an explicit set of process guidelines to help govern behavior during his firm’s debate about a critical strategic alliance decision. In that case, executives told me that Caufield and the process facilitators invoked the ground rules repeatedly when the debate seemed to veer off track or turn too personal. Alan Mulally’s “working together behaviors” served a comparable function at Ford, reminding the team how to curb affective conflict.

At the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Levy’s ground rules were by no means revolutionary; they included simple axioms such as “state your objections” and “disagree without being disagreeable.” Of course, Levy knew that simply offering these tenets to the group would not improve its ability to handle conflict. What purpose, then, did the explicit establishment of these ground rules serve? Social psychologists Connie Gersick and Richard Hackman argue that interventions such as this one can lead to learning and improvement by heightening people’s awareness of their habitual, yet problematic, patterns of action.15 Indeed, after distributing the list, Levy led a discussion about the new ground rules, during he which he modeled many of the prescribed behaviors. Over time, he referred to the list during contentious decision processes, and he “called people on bad behavior” when they violated the basic tenets that he had established. In short, the ground rules became a benchmark or yardstick by which the group could reflect upon its behavior, evaluate its decision processes in real time, and enact corrective action.

At IDEO, a clear set of ground rules govern the firm’s brainstorming sessions. For instance, one rule states: “Encourage wild ideas.” IDEO’s leaders do not want people to dismiss seemingly outlandish concepts in the early stages of a team discussion. Another rule states: “One conversation at a time.” IDEO understands that multiple side conversations can be very distracting. A team meeting can become unproductive very quickly if people are not listening carefully to one another. A third rule reminds people to “be visual.” Sometimes people disagree because they simply do not understand one another. Displaying an idea in a simple sketch can be very helpful at times. Facilitators discuss and enforce these strong shared norms on a regular basis. IDEO has even mounted posters on the walls to remind everyone of these critical rules of engagement.16

Roles

Chapter 4 discussed how role playing can help stimulate divergent thinking. It turns out that it also can be helpful as leaders try to minimize affective conflict and resolve intense disputes. By putting individuals in others’ shoes, a leader can help them to understand better the motivations and interests of people with different views on a contentious issue. Moreover, it stimulates people to listen more closely to one another, because individuals are less likely to simply repeat tired old arguments, or apply their usual analytical frameworks, when they are asked to take on a different role. Renowned negotiation scholars Roger Fisher and William Ury argue that conflict often becomes highly dysfunctional if people focus on their respective positions, rather than trying to understand one another’s interests. They explain:

Positional bargaining becomes a contest of will....Anger and resentment often results as one side sees itself bending to the rigid will of the other while its own legitimate concerns go un-addressed. Positional bargaining thus strains and sometimes shatters the relationship between the parties....Bitter feelings generated by one such encounter may last a lifetime.17

At Sun Life Financial, business unit leader Kevin Dougherty used assigned roles to both stimulate cognitive conflict and help executives understand the interests and goals of their peers in other units of the organization. As mentioned in Chapter 4, he broke his management staff into four-person teams during a two-day strategy formulation meeting in the fall of 2000. He structured the session as a competition among the teams, with each seeking to develop the best concept for a new venture at the firm. Within the groups, he assigned each member to play a specific role during these sessions. The four roles were the new venture’s CEO, COO, CFO, and vice president of marketing. Each role came with a different mission. For instance, the vice president of marketing examined the value proposition for the customer, while the COO analyzed how the new venture leveraged existing resources and evaluated how the business should be structured and organized. Dougherty asked individuals to play a role different from the one to which they were accustomed. For instance, he asked individuals from the marketing staff to play the role of CFO in their groups.

The meetings produced a great deal of divergent thinking; the management team developed some innovative ideas regarding how to grow the firm’s revenues and expand into new lines of business. Debates among team members became lively, as the competitive juices flowed and as some proposals challenged longstanding beliefs about how to compete in the marketplace. Nevertheless, interpersonal friction remained at a low level. When asked to explain why, managers pointed out that they had been forced to move beyond their “own little silos,” and they began to understand why others often raised a particular type of objection or assessed alternatives differently during key decisions. They took greater care trying to support their arguments, because they were operating in an area in which they were less familiar. Finally, people found themselves becoming much more cognizant of their own biases and predispositions.18

Dougherty’s approach may seem rather elaborate, and perhaps overly structured for some situations. In that case, leaders might adopt a simpler approach; they can ask individuals to evaluate and defend a position that they do not support. At New Leaders for New Schools, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to train exceptional new principals for urban schools, the management team needed to make a critical strategic choice during the firm’s startup phase. After much discussion, the group remained split on how the firm should proceed. Monique Burns, a co-founder and the company president, recalls that the debate seemed to go back and forth without any progress or resolution. The team decided to ask each side in the debate to write up a complete strategic plan—roughly 10 pages in length—that outlined and advocated for the strategy that they had not endorsed to that point. That experience sharpened people’s understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of each option. It made them more tolerant of opposing views, largely because individuals gained a much better understanding of why others made particular arguments. Ultimately, the group selected a strategy with little rancor and solid buy-in from all members.19

Respect

Few people would disagree that a high degree of mutual respect among team members tends to enhance their ability to disagree with one another in a constructive manner. Individuals listen more carefully and give more weight to opposing views if they value the capabilities and expertise of their colleagues and if they have a high regard for the manner in which fellow team members tend to conduct themselves. However, if leaders want to minimize affective conflict, they need to be attuned to yet another dimension of mutual respect. They must cultivate a shared understanding and mutual appreciation of the different cognitive styles that individuals possess. One should not be surprised that Caesar’s writers had immense respect for one another, and, perhaps more importantly, they recognized and appreciated the different ways that individuals approached the creative writing process.

Psychologist Mark Tennant defines cognitive style as “an individual’s characteristic and consistent approach to organizing and processing information.”20 Many different measures and typologies of cognitive style have been developed. Most people are familiar with the Myers-Briggs personality type indicator—a simple instrument that has been used for decades to help people think about how they process information and solve problems. For instance, Myers-Briggs distinguishes between individuals who tend to make decisions based on logic and objective analysis and those who tend to employ subjective value systems.21 Teams need not employ a formal survey instrument such as the Myers-Briggs to assess each member’s cognitive style, although many groups find it beneficial to do so. Frequent interaction and thoughtful reflection about these issues often proves to be nearly as enlightening.22

Monique Burns’s experience demonstrates that teams can benefit from having a candid discussion of how different members prefer to process information and make decisions. She points out that the core management team at her organization initially consisted of six individuals: two businesspeople, one political policy expert, and three teachers. As you can imagine, these individuals had what Burns described as “very different approaches to problem solving.” At first, the diversity of cognitive styles proved to be a formidable challenge for the team. Individuals seemed to have difficulty understanding how people came to a particular view on an issue. At times, they appeared to be talking past one another; finding common ground proved rather challenging. People definitely brought a great deal of passion and emotion to the debates. Burns and her colleagues did not initially recognize the problem. The potential for affective conflict rises substantially in these types of situations. Fortunately, her two co-founders, Jon Schnur and Ben Fenton, began to realize that the wide diversity of cognitive styles had become a barrier to effective communication within the team. They initiated an open discussion of this challenge facing the group, and they helped everyone understand and appreciate these important differences within the team. With heightened awareness and mutual respect for their differences, the team members found it easier to engage in productive debate on new issues going forward.23

Mutual respect and understanding extend beyond the issue of cognitive style, of course. Among other things, leaders must cultivate an appreciation of cultural differences. They must do more than address issues of language and custom, though. Team members must understand cultural differences specifically with regard to choice. In the book The Art of Choosing, Columbia Professor Sheena Iyengar describes several critical cultural differences in how individuals make decisions. She makes one broad distinction in cultures around the world: individualism versus collectivism. Some cultures, such as the United States, are much more individualistic, while other cultures, such as Japan, tend to be more collectivist. These cultures differ in a number of ways. For instance, individualistic cultures emphasize the freedom to choose. Collectivist cultures tend to emphasize one’s duty.

Iyengar has conducted some fascinating studies to identify cultural differences in decision making. Consider one study of young children (seven to nine years old), half of whom were Asian-American and half of whom were Anglo-American. She assigned the students randomly to three different groups. One group looked at some anagrams and colored markers. She told them, “Here are six piles of word puzzles you can choose from. Which one would you like to do? It’s your choice.” Children could choose which category of anagrams to work on and which color marker to use. She told a second group of children to work on a particular category of anagrams and to use the blue marker. She informed the third group that their mothers wanted them to work on a particular category of anagrams and to use a particular color marker. Interestingly, the Anglo-American children performed best when given total freedom to choose. The Asian-American children solved more anagrams when they felt that their mothers had chosen for them. These children also spent more time playing with the anagrams than those children who had chosen for themselves. The Anglo-American children, in contrast, reacted with embarrassment when told their mothers had been consulted about the exercise!24

This experiment demonstrates that many people in individualistic cultures tend to value autonomy and choice very highly. Many individuals in collectivist cultures tend to focus on shared goals and objectives and a sense of duty. Recognizing these crucial differences can be very helpful as a global management team tackles an important decision.

During the Deliberations

So you have prepared thoroughly before a debate begins—thinking carefully about roles, rules, and respect for diverse cognitive styles and cultural attitudes about choice. Nevertheless, a moment arrives when managers find themselves locked in rigid camps with seemingly little inclination to compromise with others. Arguments perhaps begin to cross the line from the substantive to the personal. What do you do now?

Reframe

When individuals seem to be locked into their positions, leaders need to find a way to alter the way that people perceive the situation. Too often, when debates get heated, individuals begin viewing the situation as a contest to be won or a test of wills. They believe that they are playing a zero-sum game, when, in fact, win–win solutions still may be achievable. Individuals stop thinking about new sources of information that might be examined or the possibility of new alternatives that might prove superior to any of the options currently being debated. They begin to worry more about losing face if the decision does not go their way rather than being concerned about the impact on the organization. In these circumstances, leaders need to shift the focus back to the problem that needs to be solved. Negotiation expert William Ury calls this “changing the frame.” He explains the dynamic:

Reframing means redirecting the other side’s attention away from positions and toward the task of identifying interests, inventing creative options, and discussing fair standards for selecting an option...Instead of rejecting their hard-line position, you treat it as an informative contribution to the discussion. Reframe it by saying, “That’s interesting. Why do you want that? Help me understand the problem you are trying to solve.” The moment they answer, the focus of the conversation shifts from positions to interests. You have just changed the game.25

The infamous teleconference that occurred on the eve of the ill-fated Challenger space shuttle launch in 1986 represents a powerful example of the lost opportunity to reframe a debate.26 During that meeting, Roger Boisjoly, an engineer at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol, tried to express his concerns about the potential for O-ring failure in the shuttle’s solid rocket booster at the cold temperatures expected on launch day. The mood became confrontational, as Boisjoly stuck to his position that the shuttle should not be launched, while NASA managers remained firmly opposed to a delay. They demanded scientific proof to support Boisjoly’s concerns. Unable to provide such evidence, Boisjoly resorted to repeating his basic argument with growing exasperation. The two sides became locked into their positions, and people became frustrated. Affective conflict began to surface. At one point, George Hardy, deputy director of science and engineering at Marshall Space Center, commented forcefully that he was shocked at the recommendations for a delay by the Morton Thiokol engineers. Imagine how people perceived that reaction to a well-intentioned, logical argument against launching the shuttle. Showing his frustration at one point, Marshall’s Larry Mulloy asked whether Morton Thiokol wanted him to wait months to launch.27 Clearly, the debate had become unproductive.

My colleague Amy Edmondson has pointed out that the meeting participants could have avoided dysfunctional debate—and perhaps prevented the disaster—by reframing the discussion as a collective-learning and problem-solving process. She points out that people did not ask inquisitive questions during the debate but repeatedly defended their own positions. Individuals did not try to understand each other’s thinking. The lack of inquiry meant that people did not learn from one another and leverage the collective expertise in the room. They simply became frustrated and emotional. If participants had refocused on the problem—trying to understand whether there was a correlation between O-ring failure and temperature—they might have recognized that they did have access to data that might have convinced everyone to delay the launch. During the meeting, Boisjoly presented data on the temperatures at launch for past flights that had had O-ring incidents. The evidence showed no apparent correlation between temperature and O-ring failure; thus, managers remained unconvinced of the threat. However, if the group had added all flights to the graph, including those without O-ring incidents, the participants would have recognized very quickly that a correlation did exist. No one asked for more data of this kind during the debate.28

Edmondson stresses the power of asking curious, nonthreatening questions to help reframe a contentious debate and break a stalemate. For instance, she points out that someone could have asked Mulloy, “What kind of data would you need to change your mind and postpone the launch?” Edmondson argues that the likely response to that question (“I would need data that suggests a correlation between temperature and O-ring erosion on past shuttle launches”) would have spurred a great deal of further investigation and learning within the group. Specifically, group members together may have uncovered the correlation data that would have convinced senior NASA executives to delay the launch.29

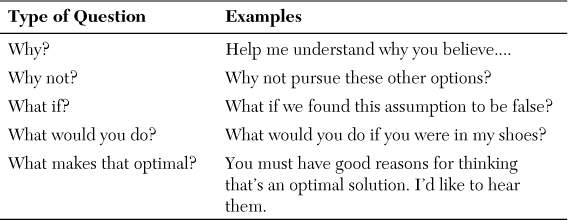

Ury concurs with this prescription for reframing a contentious deliberation: “The most obvious way to direct the other side’s attention toward the problem is to tell them about it. But making assertions can easily arouse their resistance. The better approach is to ask questions.”30 Unfortunately, people locked in a heated argument often stop asking questions and resort to pointed assertions. Worse yet, they stop listening altogether. For this reason, the leader of a decision-making process must take the initiative; he needs to spot the opportunity to shift the group into a collective inquiry mode by querying people about their goals, assumptions, rationale, and supporting evidence. Effective leaders take great care in formulating and articulating these questions. Language makes a difference when it comes to managing conflict. Leaders can model the way in which they want people to select words that are less likely to trigger defensive responses (see Table 5.4). They should not make questions sound confrontational (“Why do you keep saying that?”); instead, they ought to present inquiries as a personal desire to develop a better grasp of others’ thinking (“Help me understand...”). The tragic Challenger story reminds us that leaders would be well served to remember Peter Drucker’s sage advice: “The most common source of mistakes in management decisions is the emphasis on finding the right answer rather than the right question.”31

Source: Adapted from W. Ury. (1993). Getting Past No: Negotiating Your Way from Confrontation to Cooperation. New York: Bantam Books.

Redescribe

Sometimes conflict becomes dysfunctional because one set of individuals tries hard to convey an important idea, but they cannot present the supporting evidence in a persuasive manner. They become increasingly frustrated because they do not understand why others do not find the data compelling. It seems so obvious to them! Soon they begin to attribute the others’ inability to comprehend their argument to a personal deficiency on the part of those they have failed to persuade. They think, “How could an intelligent person not understand this point?”

Cognitive psychologist Howard Gardner, a pioneer in the study of the multiple dimensions of human intelligence, has argued that people can avoid these frustrating situations through a strategy that he calls redescription. Gardner writes, “Essentially the same semantic meaning or content, then, can be conveyed by different forms: words, numbers, dramatic renditions, bulleted lists, Cartesian coordinates, or a bar graph....Multiple versions of the same point constitute an extremely powerful way in which to change minds.”32

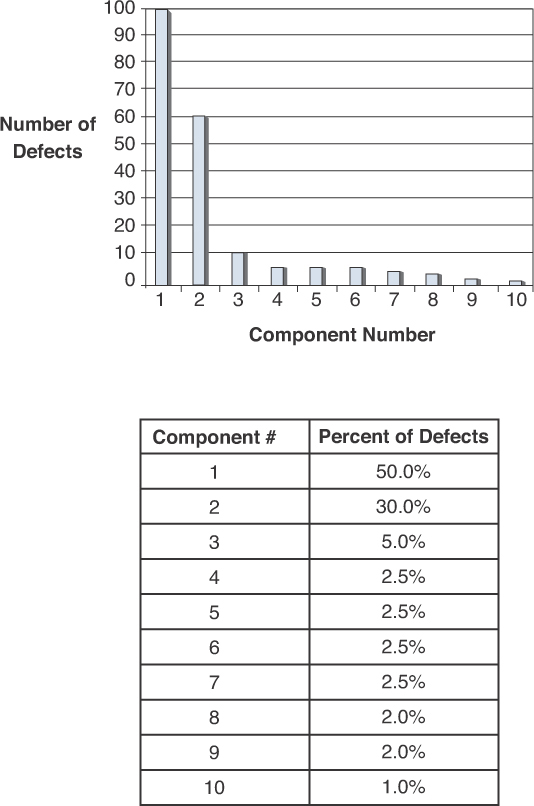

Gardner uses a simple example to illustrate his point. Many people initially approach a particular task by focusing roughly equal amounts of time and effort on each of its elements. Gardner calls this the “50/50 principle”—a notion that he believes we adopt in our early childhood. Contrast that with the Pareto principle—the so-called 80/20 rule. For instance, 20% of the components may be the cause of 80% of the defects in a particular product. The Pareto principle proves to be applicable to a wide range of tasks and situations, yet Gardner points out that people’s behavior in life often remains steadfastly consistent with the 50/50 principle. How might people be convinced to change their behavior? Gardner argues that one might describe the 80/20 principle using a variety of data formats. Tables, Cartesian grids, bar graphs, and even cartoons might be used to describe the concept. As the number of formats increases, the concept becomes more compelling. See Figure 5.2 for an example of how to demonstrate the Pareto principle using two different presentations of the same set of data.33

Source: Adapted from R. Koch. (1998). The 80/20 Principle. New York: Currency/Doubleday.

Figure 5.2 Illustrating the Pareto principle: Same content, different format

Redescription works in practice as well as in theory. In one of my classes several years ago, two students locked horns about a set of issues in a case study that I had assigned. As the debate began to heat up, another student realized that one might look at the data in a different way. This redescription helped one combatant understand the point that his opponent had been trying to make. With that new insight, frustrations eased, even though the debate continued on many fronts. Fortunately for me, their fellow student’s timely intervention had defused the potential for affective conflict.

On some occasions, people disagree because they cannot effectively picture the pros and cons of various options. You may redescribe ideas by building mock-ups of different options. Consider the example of the Boeing 747. Joe Sutter led the design team for this path-breaking jumbo jet during the 1960s. Pan American Airways, one of the prominent international airlines of that era, urged Boeing to launch this development project. Juan Trippe, Pan Am’s legendary CEO, wanted a jet that could carry 350 passengers—more than twice as many as the largest jet in service at the time.

Trippe envisioned a double-decker airplane. He figured that adding a second deck would provide the easiest mechanism for increasing passenger capacity substantially. When the design work began, Sutter and some of his engineers began to have doubts about the double-decker configuration. They began to explore an alternative—a very wide single-deck plane. To make the plane capable of carrying large amounts of cargo, engineers put the flight deck above the main deck. The idea met strong opposition at first. Some people had become very locked into the double-decker concept. They worried about how Trippe would react to this deviation from his initial vision.

Juan Trippe, John Borger, and other senior Pan Am executives came to Boeing for a crucial meeting. Sutter notes, “They arrived with dubious expressions and were a bit less cordial than usual.”34 He knew that they had serious doubts about the single-deck design. Sutter recalls that “tensions ran high” at that time. Sutter and his team decided to build two rough mock-ups. They wanted to show Trippe the look and feel of the two options. Sutter’s team built the simple mock-ups quickly and inexpensively. Sutter describes Pan Am’s reaction:

Borger and others peered into the crude mock-up’s lower hold. They knew already that double-deckers don’t offer much room for passenger baggage and revenue cargo, but there’s nothing like seeing it for yourself. I saw disappointment in their faces....I watched from below as the party inspected the lower passenger deck. Taking in the surroundings, they looked less than thrilled by the airplane’s proportions.35

Then the group of Pan Am executives moved over to the mock-up of the single-deck jet. They became intrigued by the bulge at the front of the plane, with the flight deck above the main portion of the fuselage. They recognized that this option could carry more revenue-generating cargo and that it would be safer for disembarking passengers during an emergency.

Trippe asked about the space behind the flight deck. Sutter explained that crewmembers could rest in this space during long international flights. Trippe came up with the idea of putting a small business class section in that space. He had begun to embrace an alternative to his original vision. The mock-ups relieved the tension between Boeing and its most important customer. Bringing the options to life had resolved key differences of opinion before affective conflict derailed the project and fractured this important relationship between the two parties.

Revisit

When stalemates emerge and heated debates appear ready to boil over, leaders also can ask participants to revisit key facts and assumptions. Here, leaders hope that they can get people to step back from the positions that they have taken and help them discover precisely how and why they disagree about the appropriate course of action for the organization. Often, that process of reexamining underlying presumptions fuels new avenues for information gathering and analysis. Like the other techniques described here, circling back in this manner serves the purpose of trying to help people find some element of common ground. If individuals can surface and resolve a disagreement about a key assumption in an amicable manner, it may serve as a catalyst for more effective interpersonal communication later in the deliberations. In short, improved interpersonal relationships often begin to develop through the brokering of small agreements about a particular piece of analysis or a specific assumption.36 Such “small wins” also help move groups to closure, as discussed in more detail in Chapter 9, “Reaching Closure.”

One defense industry executive described how he handled difficult moments during a critical strategic choice:

Usually, people disagreed because they either thought something was different than perhaps somebody else did in terms of data, or they assumed that the customer wanted something different than what was being presented. And generally, we decided to check that out. Go see if the customer really wants that. Go see if that data is really different.

This executive pointed out that this disciplined return to the data and the assumptions on numerous occasions enabled him to navigate a rather controversial issue without any major personal friction among his colleagues. In some sense, practice made perfect. As people focused on small areas of disagreement and managed to resolve those disputes, they developed a capability to deal with conflict in a constructive manner. The capability served them well as they approached the ultimate decision facing the organization. Instances of interpersonal tension seemed to diminish as the decision process unfolded.

Sometimes a team needs to do more than revisit key data or assumptions. It may need to turn to the organization’s core values as a guide to making tough choices. At Annie’s Homegrown, John Foraker describes how the firm always has had a strong set of values. Founder Annie Withey had inculcated these principles throughout the organization. When Foraker arrived as CEO, the firm did not have a formal document explaining those values, though many early employees clearly had a strong sense of the founder’s core beliefs. Foraker asked his team to craft an explicit statement of the firm’s values. He felt that the management team could apply those standards and principles when making difficult decisions. The team could ask: Does this alternative promote our values? Should we reject certain options because they are not consistent with our core beliefs? Revisiting core values sometimes brings clarity to a contentious discussion. It may help people look at a set of options in a very different light.37

After the Decision

Now the decision has been made. The debate has ended. If you are fortunate, the entire team has committed fully to the selected course of action. Even with such strong buy-in, your job remains incomplete. To manage debates effectively over time, leaders need to take certain steps at the end of a decision process to ensure that they will continue to develop and enhance their personal and organizational capabilities to deal with affective conflict successfully.

Reflect

Winston Churchill once said, “I am always ready to learn although I do not always like being taught.” Learning from our failures indeed can be a painful experience.38 If a group has struggled with affective conflict during a decision process, the members probably will not enjoy reviewing their missteps. However, as a leader, you need to make disciplined reflection an important part of the follow-up to each decision process. Looking back on a particular dispute, after tempers have cooled, often elicits some important lessons about how the conflict could have been managed more effectively.

Lessons-learned exercises often work best if they are conducted in a systematic manner and if groups make them a habit over time. Although many firms employ them to study large projects, one can and should adopt a similar approach to assessing decision-making processes. David Garvin’s research shows that the U.S. Army has done a particularly good job of developing a routine mechanism for reflecting on past experience.39 The Army conducts after-action reviews after every mission. The discussion proceeds in four stages, each focused on a specific question:

1. What did we set out to do?

2. What actually happened?

3. Why did it happen?

4. What are we going to do next time?

In many organizations, people begin their reflection and review of past experience by jumping to Questions 3 and 4. They want to discuss what went wrong and how to fix it. However, the Army has found that it is critical to spend a substantial amount of time on the first two questions. People need to have a clear understanding of the goals and of the standards used to measure the achievement of those objectives. Here, you will want to have a candid discussion about your criteria for judging the quality of a decision process. You should share what you hoped to achieve during a particular debate. The Army also has found that people need to develop a shared understanding of what happened in a particular situation before they can try to draw lessons from it. Think about a decision process in your organization. Do all the participants agree on how and why a particular dispute emerged during the deliberations? Did everyone perceive the interpersonal tension in a similar manner? Perhaps some people did not even attend the specific meeting in which tempers flared. Everyone needs a complete map of the territory if they are to contribute to the learning process.40 Having accomplished this, you then can turn to analysis of why the conflict unfolded as it did and how the group should change its approach in the future.

In many organizations, people conduct post-mortems—that is, think about the need for reflection and review—only when they fail. The Army takes a different approach; it examines all missions, regardless of the degree of success or failure. The Army recognizes that, amid a largely successful mission, many mistakes occur. Likewise, even when a mission fails to achieve its primary goals, some things go right.41 Leaders should adopt a similar approach when reflecting on past decision processes. Regardless of the overall outcome, instances of effective and ineffective conflict management may have occurred. Leaders need to capitalize on each of those moments as learning opportunities.

Repair

When decision-making processes end, it may not always be apparent to a leader, or even to some of the participants, that one or more individuals feel that they were criticized personally. Some people may believe that the conflict remained constructive, whereas others do not. People’s feelings may be hurt, and bitterness may linger after a particularly ardent disagreement, yet they may keep those feelings largely to themselves. Leaders must take great care not to presume that everyone perceived the conflict as they did. Silence does not necessarily denote a uniformly positive affect about the decision process. Leaders should probe for negative emotions, damaged self-esteem, and frayed interpersonal relationships.

If leaders discover that some fallout has taken place after a difficult debate, they need to shift into repair mode. They need to address those issues head on before another contentious decision process takes place. If not, the personal friction among a few individuals may spill over and disrupt the entire team or even the organization as a whole. At Emerson Electric, Chuck Knight adopted a simple technique for keeping tabs on people’s feelings and emotions after a tough debate. When one of his highly confrontational strategy reviews ended, he always tried to sit next to the business unit president at the dinner that immediately followed the conclusion of the meetings. Of course, that individual typically bore the brunt of the critical questioning from the corporate staff, including himself. He wanted to use the dinner conversation to assess whether the business unit president felt negatively about the discussions that had taken place earlier in the day. If Knight felt that he had damaged their working relationship in any way, he began to work on a plan to repair that connection.42

Knight’s direct approach may not always unearth negative emotions. People may recoil further in some circumstances, seeking to suppress their feelings for fear that disclosure may harm their reputation in some way. They may not want to be perceived as “soft” or “thin-skinned.” For that reason, leaders need to look for subtle signals of lingering interpersonal tensions. They might search for disruptions in the usual patterns of social interaction among their colleagues. Similarly, they might keep an eye out for sudden changes in the level of participation by a particular manager. A typically talkative person suddenly becoming rather quiet during meetings may be a cause for concern. Similarly, if a rather reserved individual seems to be more argumentative than usual, one might pay a bit more attention to how past disputes may have affected him. In many instances, if leaders begin to look for these danger signs, they will find that the signals are not all that subtle. Leaders simply needed to become a bit more attuned to changes in people’s usual patterns of behavior.

Remember

Finally, leaders want their organization to remember particularly striking examples of constructive conflict management. They want to celebrate those instances and build them in to the treasure chest of “classic stories” that people tell about the historical development of the organization. Leaders should do that as a reward for those who dealt with the disagreement in a positive manner. Moreover, they should encourage others to emulate that behavior. Individuals may not always feel very positive about a contentious debate, even if they managed to keep affective conflict reasonably in check. The simple fact that they engaged in a rather confrontational discussion with a colleague—and perhaps danced close to the edge regarding personal criticism—may make them feel a bit uncomfortable. The leader ought to tell the story to others, showcasing it as an example of desirable behavior, to lessen people’s anxiety about expressing dissent, particularly if the organization has had a “polite” culture in the past.

As noted earlier, Paul Levy took charge of an organization where people typically did not express dissent openly during meetings, and they did not effectively handle conflict when it did emerge. He desperately wanted to change that culture. During one committee meeting in his first few months on the job, it became apparent to him that two individuals disagreed strongly about a particular issue, yet the dispute bubbled beneath the surface. He intentionally sparked a fight between the two individuals. The rest of the group sat rather shocked and appalled that these people were shouting at one another. At the end of the meeting, Levy acknowledged their dismay, but he noted that he was glad that the disagreement had come to the surface and been discussed openly. The two sides worked through their disagreement very constructively, with his help, and they had arrived at a good solution for the organization by the next meeting. At that time, Levy again acknowledged the discomfort that many individuals felt about the contentious disagreement, but he asked the two “combatants” if they were glad to have addressed the dispute as they had. The two individuals responded that they were satisfied.

One of them actually concluded the meeting by singing a song that he had composed about the incident. He sang to the tune of “Down by the Levy”—a cute play on the CEO’s name. Levy, of course, knew that the story of this wonderful resolution to the conflict would spread throughout the organization. He simply accelerated the dissemination of the story, and he made it clear that he was thrilled by how these individuals had handled the conflict. With that, he sent a strong signal to the organization about how he wanted it to deal with conflict in the future. He used this rather vivid memory as a powerful teaching moment.43

Building a Capability

This chapter has examined a number of mechanisms for alleviating or preventing affective conflict. We have learned that conflict management requires a substantial amount of skill and a great deal of forethought. Leaders must be adept at diagnosis, mediation, coaching, and facilitation. Often, they need to become personally involved to resolve heated disputes between managers in their organizations. We have argued that practice makes perfect; in other words, leaders become more adept at dispute resolution over time. Conflict management can become a personal capability that individuals feel quite comfortable drawing upon to ensure that decisions are made in a timely and efficient manner.

Consultants Charles Raben and Janet Spencer point out, however, that conflict management should not remain simply a personal competency of the leader. Leaders must coach their team members so that they become adept at managing disagreements constructively. Conflict management must become a shared responsibility, and ultimately, an organizational capability—not simply a personal one. Leaders cannot micromanage each disagreement. The authors write in reference to CEO behavior, but their argument applies to leaders at all levels:

The CEO must develop competency in the area of coaching and facilitation....In order to be a successful coach and facilitator, a CEO must be motivated by a genuine desire to help others become more adept at resolving conflicts. A CEO whose overarching concern is resolving the conflict at hand and getting everyone back to business as usual will lack the patience and commitment to see the process through to a successful conclusion. CEOs are, by nature, impatient and action-oriented; they see a problem, they want it solved. To develop competency as a coach/facilitator, then, often requires the CEO to develop new skills and adopt a new perspective.44

Freedom and Control

Leaders certainly cannot resolve every dispute that arises during a complex decision-making process. They need help. They must develop the skills of their subordinates. Moreover, after a leader unleashes the power of divergent thinking, he inherently gives up some control over the ideas and options that are discussed. Yet leadership always entails a broad responsibility for establishing the context in which people behave, as well as the processes that groups employ to initiate and resolve conflict. Leaders can and should shape and guide how people disagree, as well as the atmosphere in which that debate takes place. Along these lines, Larry Gelbart once reflected back on Sid Caesar’s leadership of the wildly creative process in the Writers’ Room. Gelbart remarked, “He had total control, but we had total freedom.”45

Endnotes

1. This account of the Caesar comedy-writing team draws from an Institute for Management Development case study about the group, as well as Sid Caesar’s autobiography. See B. Fischer and A. Boynton. (2002). “Caesar’s Writers,” IMD Case No. 3-1206, and S. Caesar. (1982). Where Have I Been? New York: Crown.

2. Fischer and Boynton. (2002). p. 7.

3. Caesar. (1982). p. 5.

4. Fischer and Boynton. (2002). p. 8.

5. My colleague David Garvin and I have described these two modes of decision making as advocacy and inquiry. See Garvin and Roberto. (2001). Chris Argyris and his colleagues have described advocacy vs. inquiry in a slightly different way in their work on group process and learning. See C. Argyris, R. Putnam, and D. Smith. (1985). Action Science: Concepts, Methods, and Skills for Research and Intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

6. See D. Lau and K. Murnighan. (1998). “Demographic diversity and faultlines: The compositional dynamics of organizational groups,” Academy of Management Journal. 23: pp. 325–340, and J. Polzer, C. B. Crisp, S. Jarvenpaa, and J. Kim. (2006). “Extending the faultline model to geographically dispersed teams: How collocated subgroups can impair group functioning,” Academy of Management Journal. 49(4): pp. 679–692.

7. M. Roberto. (2004). “Strategic decision-making processes: Moving beyond the efficiency–consensus tradeoff,” Group and Organization Management. 29(6): pp. 625–658; K. Eisenhardt, J. Kahwajy, and L. Bourgeois. (1997). “How management teams can have a good fight,” Harvard Business Review. 75(4): pp. 77–85.

8. C. Lord, L. Ross, and M. Lepper. (1979). “Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37: p. 2098.

9. Many studies have reported a relationship between cognitive and affective conflict. For instance, see Amason. (1996) and Pelled, Eisenhardt, and Xin. (1999).

10. My colleague David Garvin and I created a set of group decision-making exercises modeled after the experiments found in Schweiger, Sandberg, and Ragan. (1986). See Garvin and Roberto. (1996). When we conduct these exercises with MBA students and executive education students at Harvard Business School, cognitive conflict often leads to affective conflict despite the fact that teams discuss simple, disguised case studies in their decision-making processes, and of course, the choices do not pertain to real issues in their own organizations.

11. Interview with B. McMillan conducted August 19, 2002. See also M. Roberto and G. Carioggia. (2003). “Electronic Arts: The Blockbuster Strategy,” Harvard Business School Case No. 304-013.

12. B. Carey. (2009). “In battle, hunches prove to be valuable,” New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2009/07/28/health/research/28brain.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0, accessed December 5, 2012.

13. B. Carey. (2009). “In battle, hunches prove to be valuable,” New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2009/07/28/health/research/28brain.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0, accessed December 5, 2012.

14. David Garvin and I have developed an innovative multimedia case study about Levy’s turnaround of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The research’s distinguishing feature is that we were able to track the turnaround in real time; in fact, we conducted lengthy (over two hours) video interviews with Levy every two to four weeks during the first six months of the turnaround. The multimedia case study includes clips from those interviews, internal e-mails and documents, and articles that appeared in the press—all of which document the turnaround in great depth. The material has been organized in a calendar, where students can see the major activities that took place each month and then drill down deeper to hear Levy’s comments about the event, read e-mails and other internal documents that may pertain to it, and examine press accounts as well. The case also presents a representative week from Levy’s actual calendar/schedule so that students can understand precisely what he does on a day-to-day basis as he launches the turnaround. See D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (2003). “Paul Levy: Taking Charge of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center,” Harvard Business School Multimedia Case No. 303-058. A detailed teaching note explains how to teach this multimedia case. In addition, we have written an article examining some of the leadership lessons from this story. See D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (2005). “Change through persuasion,” Harvard Business Review. 83(2): pp. 104–113.

15. C. Gersick and J. R. Hackman. (1990). “Habitual routines in task-performing groups,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 47: pp. 65–97.

16. T. Kelley. (2001). The Art of Innovation. New York: Currency Doubleday.

17. R. Fisher and W. Ury. (1991). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 6–7.

18. M. Roberto. (2001). “Strategic Planning at Sun Life,” Harvard Business School Case No. 301-084.

19. Interview with Monique Burns, conducted September 12, 2003.

20. M. Tennant. (1988). Psychology and Adult Learning. London: Routledge. p. 89.

21. For more information about the Myers-Briggs personality types, see I. Myers Briggs and P. Myers. (1995). Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type. Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black Publishing.

22. It is interesting to note, however, that first-year students at Bryant University, students in the MBA and advanced management program (executive education) at Harvard Business School, and students at many other institutions often complete the Myers-Briggs test soon after arriving on campus. Perhaps discussion of the survey results enhances people’s respect for others’ cognitive styles, and thereby improves our ability to stimulate constructive debates in our classrooms. To my knowledge, we have not examined the impact of the Myers-Briggs evaluations on subsequent student interaction in our classrooms, but I believe that this question may warrant further investigation.

23. Interview with Burns. (2003).

24. S. Iyengar. (2010). The Art of Choosing. New York: 12.

25. W. Ury. (1993). Getting Past No: Negotiating Your Way from Confrontation to Cooperation. New York: Bantam Books. p. 78.

26. See Vaughan (1996) for a detailed description of the events that took place during the teleconference prior to the final launch of the Challenger space shuttle. See also Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident. (1986). Report to the President by the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Many different analyses of this teleconference have been done, from various conceptual angles. For instance, James Esser and Joanne Lindoerfer argued that the managers and engineers engaged in “groupthink” during the critical prelaunch meeting. See J. Esser and J. Lindoerfer. (1989). “Groupthink and the Space Shuttle Challenger accident: Toward a quantitative case analysis,” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2: pp. 167–177. Vaughan, however, argues that many of these other analyses do not offer either accurate or complete explanations of the accident. For instance, she makes the case that the groupthink hypothesis does not fit the facts with regard to what took place at the teleconference. See Vaughan. (1996). p. 525.

27. Vaughan. (1996). p. 6.

28. A. Edmondson and L. Feldman. (2003). “Group Process in the Challenger Launch Decision (A), (B), (C), and (D) (TN),” Harvard Business School Teaching Note No. 604-032. For educators who are interested in teaching these concepts, Edmondson’s teaching note explains how she uses an ABC film (Challenger—a 1990 movie directed by Glenn Jordan) to stimulate discussion about the Challenger launch decision. In class, she then conducts a role play of the deliberations that took place at the midnight teleconference on the eve of the launch. As students engage in the role play, she encourages them to think about how posing the right type of questions can foster an inquiry orientation and more effective collaborative learning process. She also describes how certain types of comments simply lead to a hardening of positions and more affective conflict.

29. Edmondson and Feldman. (2003). p. 14.

30. Ury. (1993). p. 80.

31. P. Drucker. (1954). The Practice of Management. New York: Harper & Row. p. 351.

32. H. Gardner. (2004). Changing Minds: The Art and Science of Changing Our Own and Other People’s Minds. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. pp. 11, 14. Gardner’s book provides a useful framework for thinking about how to engage in effective persuasion during a situation in which others disagree with you. Specifically, Gardner identifies seven levers that one can use to convince others to reconsider their position on a subject. The book builds upon Gardner’s earlier work on the nature of human intelligence. See H. Gardner. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

33. In Changing Minds, Gardner’s description of the power of representational redescription uses the example of the Pareto principle, and it includes graphs such as those shown in Figure 5.2. Gardner draws his example from a book about the Pareto principle. See R. Koch. (1998). The 80/20 Principle. New York: Currency/Doubleday.

34. J. Sutter. (2007). 747: Creating the World’s First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation. New York: Harper. p. 100.

35. J. Sutter. (2007). 747: Creating the World’s First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation. New York: Harper. pp. 101–102.

36. K. Weick. (1984). “Small wins: Redefining the scale of social problems,” American Psychologist. 39(1): pp. 40–49.

37. J. Foraker. (2010). Speech at Bryant University, February 25, 2010.

38. In some organizations, finger-pointing and the designation of blame crowd out learning opportunities when failures take place. Moreover, individuals often do not want to talk about their failures because they are embarrassed or because they do not want to admit their mistakes in a public forum. For more on how to enhance tolerance of failure in organizations, see Farson and Keyes. (2002). For additional insight into why organizations do not learn effectively from failure, see A. Tucker and A. Edmondson. (2003). “Why hospitals don’t learn from failures: Organizational and psychological dynamics that inhibit system change,” California Management Review. 45(2): pp. 55–72.

39. Garvin. (2000). Garvin’s book, Learning in Action, provides a detailed analysis of the U.S. Army’s after-action reviews. For additional information about this learning process, see D. Garvin. (1996). “Putting the Learning Organization to Work,” Harvard Business School Publishing Video.

40. At Children’s Hospital and Clinics in Minnesota, the staff have come to a similar conclusion with regard to how they conduct “focused event studies”—lessons-learned exercises that take place after a medical accident has taken place. The doctors, nurses, and administrators at Children’s Hospital have discovered that a focused event study must begin with a detailed mapping of the events that took place leading up to the accident, before people turn to a discussion of the causes of the failure. In part, staff members have come to this conclusion because each individual often does not know the full chain of events that took place. A similar situation may exist with regard to a complex decision-making process. For more details on focused event studies at Children’s Hospital, see Edmondson, Roberto, and Tucker. (2002).

41. Garvin. (2000).

42. C. Knight. (2004). Discussion during Harvard Business School class, February 23, 2004.

43. D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (2003). “Paul Levy: Taking Charge of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center,” Harvard Business School Multimedia Case No. 303-058.

44. C. Raben and J. Spencer. (1998). “Confronting senior team conflict: CEO choices,” in D. Hambrick, D. Nadler, and M. Tushman, eds., Navigating Change: How CEOs, Top Teams, and Boards Steer Transformation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. p. 188.

45. Boynton and Fischer. (2002). p. 1.