7. The Dynamics of Indecision

“Deliberate often. Decide once.”

—Latin proverb

In 1996, a merger took place between the Beth Israel and the Deaconess hospitals, two large and well-respected health-care institutions in Boston, Massachusetts. The merged entity brought together more than 1,000 highly accomplished physicians and had revenues of nearly $1 billion. Senior executives at the newly formed Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) hailed the merger as a “good fit” and cited the potential for “tens of millions of dollars” in cost savings.1 Not everyone remained convinced that the deal would pan out. The Boston Globe commented, “The concept is attractive; the reality may be a bit messy.”2

The early years of the marriage did not go smoothly, to say the least. The financial losses escalated rapidly, topping $50 million per year in fiscal years 1998 through 2001. Several CEOs tried and failed to execute a turnaround. The Massachusetts attorney general began to pressure the board of directors to consider selling the institution to a for-profit health-care firm. Amid this turmoil, Paul Levy took over as chief executive in January 2002. As Levy assessed the situation, he noted that prior management had done a great deal of work analyzing the hospital’s problems and discussing alternative proposals designed to restore the organization’s financial health. Several consulting firms had performed extensive studies, and they had provided sound recommendations to the medical center’s senior management team. Yet substantive organizational changes never materialized. The organization seemed to be “all talk, no action.” Levy explained:

This was not a question of not knowing what to do. Everyone knew what had to be done. This was an absolute failure to execute, which, ultimately, is a failure of leadership....BIDMC leadership was simply unable to reach an agreement on a programmatic plan for the hospital....I define the problem of the BIDMC as a curious inability to decide.3

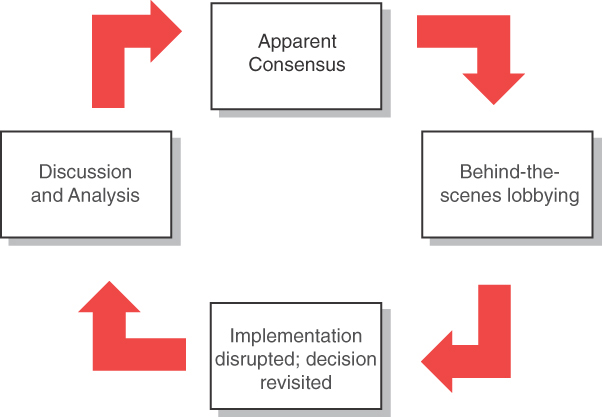

The BIDMC may sound like a particularly dysfunctional organization, but in fact, many organizations are plagued by the “curious inability to decide.” In some cases, managers engage in plenty of debate, and they simply can never come to a consensus. The leader fails to bring deliberations to a close, make a decision, and move forward with a plan of action. The organization remains frozen in its tracks, while competitors gain the upper hand. The management team becomes a “debating society” or finds itself embroiled in “analysis paralysis.”4 In other instances, a sense of false consensus emerges during decision processes. That is, people tend not to voice objections during meetings. Instead, they work around the decision process, laboring behind the scenes to kill projects or derail decisions in the early stages of implementation. The leader thinks a decision was made and is being implemented, but soon he discovers that the course of action has not been enacted. In these organizations, decisions are apparently made, but they don’t survive long enough to be executed.

Napoleon Bonaparte once said, “Nothing is more difficult, and therefore more precious, than to be able to decide.” He recognized that many leaders find themselves unable to take decisive action when confronted with ambiguous information, dynamic environmental conditions, and conflicting advice from others. They cannot bring debates to a close, choose a course of action in a timely manner, and build the commitment and shared understanding required to implement their plans effectively. In this chapter, we examine why organizations experience the “curious inability to decide.” Specifically, we examine the patterns of behavior, often deeply embedded in an organization’s culture and processes, that create a systematic inability to reach closure in the decision-making process. In the two chapters that follow, we examine how leaders can overcome these barriers, build commitment and shared understanding, and reach closure in a timely manner.

A Culture of Indecision

People often conclude that organizational indecisiveness and inaction simply reflect the problematic leadership style or personality of a particular executive. They point to managers being irresolute, undisciplined, and/or overly cautious. Those descriptors may very well apply to some executives who find it difficult to reach closure on critical decisions. However, the phenomenon of a “curious inability to decide” often stretches far beyond the leadership capabilities of a particular individual. In many cases, it is a pattern of behavior that permeates the entire organization. Groups cannot arrive at consensus because dysfunctional habits of dialogue and decision making have become second nature to many members of the organization. Those habits manifest themselves through the manner in which dialogues and deliberations take place at all levels of the firm, in many different types of formal and informal teams and committees.

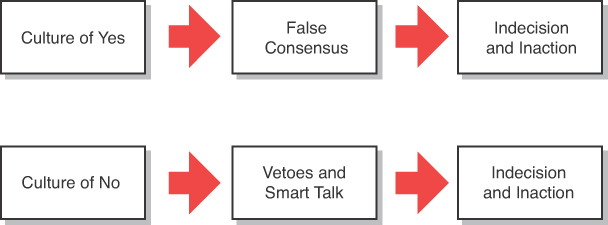

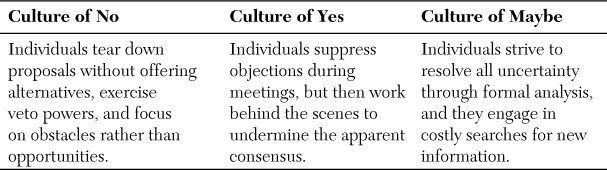

Ram Charan, a renowned adviser to the CEOs of many Fortune 500 firms, describes the problem as a “culture of indecision.”5 By culture, I mean the often taken-for-granted assumptions of how things work in an organization, of how members approach and think about problems.6 In other words, certain patterns of behavior gradually become embedded in the way that work gets done on a daily basis, and sometimes those patterns lead to a chronic inability to reach closure on critical decisions. Over time, those patterns of behavior become taken for granted, and people engage in them without much forethought. In my research, I have found that such dysfunctional decision-making cultures come in three forms: a culture of no, a culture of yes, and a culture of maybe. Each comes with its own predictable and easily identifiable patterns of interaction and dialogue, and each has its own underlying causes. Yet they all lead to a similar outcome—a chronic inability to move from conflict to consensus, from deliberation to action.

The Culture of No

When Louis Gerstner became IBM’s CEO in 1993, he faced an enormous challenge. The company’s performance had declined dramatically, after decades as the dominant behemoth in the computer industry. The company’s share price had declined by 70% over the preceding 6 years. Mainframe revenues—once the company’s mainstay—had dropped by nearly 50% since 1990. The firm lost $8.1 billion in 1993 alone. Prior to Gerstner’s arrival, the board of directors had even discussed the possibility of breaking up the company into several smaller independent firms.7

Gerstner set out to diagnose the problems at IBM, and he soon discovered that many problems were rooted in the firm’s culture. Once a competitive strength, the IBM culture had become insular and rigid. The firm had not kept pace with the dynamic changes taking place in the computing industry. It did not have deep insights regarding its customers’ needs nor a solid grasp of how rivals had a competitive edge in many areas.

Gerstner described one of IBM’s problems in the early 1990s as “the culture of no.” A cross-functional group could spend months working on a solution to a problem, but if a manager objected because of the deleterious impact on his business unit, he could obstruct or prevent implementation. In the IBM vernacular, a lone dissenter could issue a “nonconcur” in this type of situation and stop a proposal dead in its tracks. Gerstner discovered that IBM managers had actually designed a formal nonconcur system into the company’s strategic planning process. In a rather incredible memo that Gerstner uncovered, an executive went so far as to ask each business unit to appoint a “nonconcur coordinator” who would be responsible for blocking projects and proposals that would conflict with the division’s goals and interests. Gerstner described the “culture of no” as follows:

One of the most extraordinary manifestations of this “no” culture was IBM’s infamous nonconcur system....The net effect was unconscionable delay in reaching key decisions; duplicate effort, as units continued to focus on their pet approaches; and bitter personal contention, as hours and hours of good work would be jeopardized or scuttled by lone dissenters. Years later, I heard it described as a culture in which no one would say yes, but everyone could say no.8

A culture of no goes far beyond the notion of cultivating dissent or encouraging people to play the role of devil’s advocate. In fact, it undermines many of the principles of open dialogue and constructive debate that we have espoused. It means that dissenters have veto power in the decision-making process, particularly if those individuals have more power and/or status than their peers.9 A culture of no enables those with the most power or the loudest voice to impose their will.

A culture of no need not manifest itself in a formal system by which people issue objections, such as the bureaucratic procedures at IBM in the early 1990s. It can simply permeate the informal incentive structures and patterns of communication within an organization. Some cultures, for instance, reward people as much for what they say as for what they do. People garner attention and acclaim when they sound intelligent and insightful during meetings. Delivering a “gotcha” during a presentation becomes a badge of honor in such organizations. Group discussions become forums for impressing others rather than a means of accelerating action on a key issue.

Scholars Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutton describe this phenomenon as the “smart-talk trap.” Their research shows that “people who talk frequently are more likely to be judged by others as influential and important—they’re considered leaders.”10 At first glance, that finding may not alarm you. Leaders do need the ability to articulate their ideas in a concise and persuasive way in public settings. However, Pfeffer and Sutton also have discovered that “smart talk” tends to be overly negative and complex. When people strive to impress others in meetings, they tend to explain how and why a proposal will not work rather than describe why it might succeed. Why the persistent emphasis on negativity? Based on the findings from field and experimental research, Pfeffer and Sutton argue that an individual is more likely to bolster others’ perceptions of his intelligence by offering critiques rather than positive pronouncements about proposals and ideas under consideration. They find that many organizations encourage “the tendency to tear an idea down without offering anything positive in its place.”11 Smart talk becomes an impediment to open, constructive dialogue and an obstacle that prevents firms from moving from analysis to action. The behavior persists and even spreads throughout firms because individuals believe, often rightfully, that smart talk helps them get ahead. Unfortunately, many organizations do not understand how their reward structure—particularly the institution’s informal reward and punishment system—promotes the development of a dysfunctional “culture of no.”12

The Culture of Yes

Paul Levy faced a problem a bit different than the one encountered by Gerstner at IBM. Dissenters did not openly express their objections at the hospital. Nothing similar to the nonconcur system existed, and smart talk did not characterize the dialogue within the organization. Doctors gained prestige and power based upon the groundbreaking research that they published, not the clever pronouncements they offered during meetings. The physicians often sat quietly during discussions of administrative issues; nevertheless, the organization found it difficult to reach closure on critical decisions. Levy traced the problem to a dysfunctional pattern of behavior that had become routine at the hospital:

People will not tell the truth during meetings about how their department would react to a given proposal....They will sit there quietly and you won’t find out until a week later that they object to something....This behavior had become standard practice. If you object to a proposal, you get quiet during the meeting. Then later, when you leave the room, you undercut the consensus that appeared to have emerged.13

A new manager in these circumstances might assume that silence means assent. However, Levy found that the hospital’s culture discouraged those who said “no” during a meeting with their peers and superiors. Instead, people felt more comfortable conveying a sense of “yes” during group meetings, while working behind the scenes, often in one-on-one conversations, to convey their concerns and objections. Because of the lack of open and honest dialogue, the hospital executives found themselves constantly revisiting decisions that apparently had been made. Over time, new employees at the hospital learned how to behave in conformance with the cultural norms simply by observing others. A strong tacit understanding of accepted practice began to shape individual behavior.

Many firms find themselves in a similar predicament. (See Figure 7.1 for a depiction of the dynamics of indecision.) Reflecting on his experiences in executive suites around the world, Ram Charan points out that he has observed many instances in which “The true sentiment in the room was the opposite of the apparent consensus.”14 He argues that an overemphasis on hierarchy, excessive process formality, and a lack of interpersonal trust contribute to the problem. To be honest, I can recall a number of faculty meetings characterized by the very same dynamic; let’s just say that management professors do not always practice what they preach!

Simply raising people’s awareness of such dysfunctional behavior typically does not alter the “culture of yes.” Several years ago, I conducted a full-day workshop on decision making with senior executives at a successful investment-banking firm. We spent much of the day talking about how to encourage more open dialogue and constructive dissent. The group performed a thoughtful diagnosis of the organization’s approach to decision making, and it concluded that the “culture of yes” characterized some discussions within the firm. At the end of the day, the top executive at the session put forth a proposal for how to implement some changes based on what they had learned during the workshop. He asked the group members whether they concurred with his recommendation, and no one raised any objections. Soon thereafter, he concluded the day’s session. By the very next morning, he had received a deluge of phone calls and e-mails from individuals expressing their concerns with the proposal!

Some leaders foster a “culture of yes” through the design of their decision processes. That is, they develop routine procedures for analyzing and reviewing alternative courses of action that actually encourage managers to work behind the scenes to block decisions with which they do not agree. Take the example of Don Barrett, a division president at All-Star Sports, a discount sporting goods retailer. Barrett’s direct reports described him as someone who strove to build consensus on most important issues. However, even Barrett acknowledged that his management team often found it difficult to reach closure: “We tend to allow issues to resurface....If people don’t agree with a decision, then they tend to think they can keep bringing it up over and over, and this will lead to a change in the decision.” His direct reports concurred. As one team member pointed out, “Something prevents us from actually reaching a definitive conclusion on issues.”15

What caused the problems at All-Star Sports? Barrett had a fairly large senior team, with 12 members besides himself. Decision making could become rather cumbersome and slow in such a large group, and the prospect of affective conflict concerned Barrett. Therefore, the team developed a habit of asking a small subgroup to take contentious issues “offline” for further analysis. The subgroup worked closely with Barrett to examine multiple alternatives. After completing extensive analyses, the subgroup presented Barrett with a tentative recommendation. He reviewed the analysis, discussed the subgroup’s assumptions, and often requested additional work. Dissent and debate flowed freely during these sessions. Finally, Barrett and the subgroup together selected a particular course of action that they would recommend to the full management team, which had responsibility for ratifying the decision.

Barrett expected the large team to raise questions about the recommended course of action, yet such inquiries and objections rarely surfaced. People felt that the subgroup’s recommendations represented a fait accompli because of the earlier communications with Barrett. Given the knowledge that he had endorsed the subgroup’s conclusions, they withheld their concerns during the group meeting. However, conflict often emerged through informal channels after the meeting. People often found themselves asking, “Didn’t we make this decision already?” Backroom lobbying became the norm at All-Star Sports. As one manager observed, “People don’t invest heavily in what goes on in the room....The meeting is the wrong place to object, so people work around it.” In sum, despite their good intentions, Barrett and his staff had designed a fairly rigid decision-making procedure that cultivated a “culture of yes.”16 Figure 7.2 summarizes how the “culture of yes” and the “culture of no” arrive at a similar undesirable outcome by taking different paths.

The Culture of Maybe

Some organizations have highly analytical cultures. Managers in these firms strive to gather extensive amounts of objective data prior to making decisions. They try to apply quantitative analysis whenever possible, and they make exhaustive attempts to evaluate many different contingencies and scenarios. Scholars James Fredrickson and Terence Mitchell describe these decision-making processes as highly comprehensive. Naturally, this approach to decision making has its strengths. In their research, Frederickson and Mitchell try to confirm that comprehensiveness leads to higher firm performance. They find that it does so in organizations operating in relatively stable environments, but it has a negative relationship with performance for firms competing in relatively unstable environments. The scholars postulate that comprehensiveness slows down decision-making processes and, therefore, becomes a perilous handicap for firms competing in dynamic markets.17

Some organizations and their leaders find it difficult to cope with the uncertainty that characterizes turbulent environments. They go to great lengths to gather more information and perform additional formal analysis, in hopes of reducing the ambiguity associated with various options and contingencies. They strive for certainty in an inherently uncertain world—to turn every maybe into a simple yes or no. Indecision and a lack of closure result if managers cannot recognize the costs of trying to gather a more and more complete set of information.

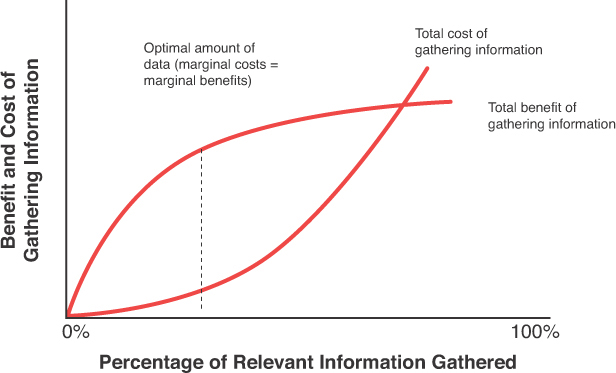

Stanley Teele, a former dean of Harvard Business School, once said, “The art of management is the art of making meaningful generalizations out of inadequate facts.” Yet certain organizational cultures discourage managers from drawing conclusions based upon limited datasets. A “culture of maybe” prevails, in which people find themselves endlessly pursuing every unresolved question rather than weighing the costs and benefits of gathering more information or performing more analysis. Many organizations do not recognize when the incremental, or marginal, value of additional information search has begun to decline. They continue to gather information even when the marginal costs of new data begin to rise dramatically, while the incremental benefits become very small.

Figure 7.3 shows a conceptual description of the information search problem that managers face. As the graph shows, when organizations gather the first bits of information associated with a decision, the incremental benefits are large, whereas the costs are low. As firms try to gather more information, the search becomes increasingly difficult and time-consuming. The incremental costs of an additional piece of information eventually begin to rise dramatically, while the marginal benefits of extra data diminish over time (that is, the total cost curve in the chart begins to steepen, while the total benefit curve starts to flatten). An optimal level of information gathering occurs when the biggest gap exists between total costs and total benefits. When firms move beyond that point, the incremental costs of additional information exceed the marginal benefits.18 Naturally, firms do not have a magic formula for calculating the value of information search or for plotting it on a graph, as in Figure 7.3. We have provided the chart for the purpose of making a critical conceptual point. However, managers can recognize the dynamic depicted in the chart and raise others’ awareness of the value creation or destruction taking place as an organization searches for higher and higher levels of certainty and unassailable proof before taking action.

Source: Adapted from F. Harrison. (1996). The Managerial Decision-Making Process, 4th edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 49.

Figure 7.3 Optimal information search activity

When managers have gathered a great deal of information, they sometimes become overwhelmed by all the data. They cannot discern the information that is most valuable and relevant. They do not know where to focus their attention. Some organizations seek to establish “dashboards” that provide quick, concise snapshots of the health of a business. A dashboard tracks the key performance indicators for a company. Over time, though, many dashboards become increasingly complex. With each shortfall in performance, executives pile on new metrics, charts, and analyses. Decision making becomes bogged down because people can no longer discern the areas that need the most attention. The Corporate Executive Board offers some advice for how to avoid analysis paralysis:

Unclutter dashboards for managers: Even the most relevant and informative survey data won’t get very far in your organization if managers cannot readily access them. Our research shows that managers who transform data into usable information for their teams can increase business performance by 24 percent. So, focus managers on what matters by providing them with personalized views of the data they need to be effective. Streamlined online dashboards provide managers with instant access to aggregate survey results from their team and organization overall. Ideally, they highlight areas of strong performance and opportunities for improvement for each manager, and equip them with the resources to improve.19

Many factors explain why organizations become embroiled in a “culture of maybe” when faced with ambiguity and environmental dynamism. For starters, some firms have many members whose personality and cognitive style tend to favor rational and objective methods of problem solving. Moreover, management education and training programs tend to preach the value of systematic analytical techniques. Employees often fall back on those methods when faced with complex problems.

Digging deeper, one finds that a natural human tendency also explains why many organizations place such emphasis on analysis and information gathering, even when the costs of doing so become prohibitive. Psychologists Irving Janis and Leon Mann argue that many individuals experience anticipatory regret when they make critical decisions. In other words, people become anxious, apprehensive, and risk averse as they imagine the negative emotions that they may experience if the decision does not transpire as expected. High levels of anticipatory regret can lead to indecision and costly delays.20 Scholars have found that this anxiety and lack of confidence even affect very accomplished leaders, from U.S. presidents to top executives in Silicon Valley.21 In some organizations, managers consistently fall back on formal analysis, planning systems, and intensive market-research studies in order to overcome anticipatory regret. They find cognitive and emotional comfort in the quantification and analytical rigor that characterize such efforts. Unfortunately, managers often arrive at a false sense of precision in these circumstances, and these tactics exacerbate delays in the decision-making process, without truly resolving many outstanding questions.22

Surprising new research suggests that taking too much time to make a decision may increase the likelihood of ethical transgressions. How could that be? The University of Toronto’s Chen-Bo Zhong and several co-authors have conducted experimental research on the impact that lengthy deliberation can have on ethical behavior. They developed a series of vignettes covering a broad range of circumstances. Each vignette came with several options from which to choose. Independent raters evaluated the extent to which each option was ethical.

The experiment began by asking 140 people to read 12 vignettes. Then the scholars asked each subject to make decisions immediately with regard to the first 4 vignettes. They requested that the participants take some time to think about the other 8 cases. Two weeks later, the scholars requested a decision on 4 of those vignettes and asked participants to continue deliberating about the remaining cases. Finally, they collected the decisions on the remaining 4 vignettes after another two weeks had transpired.

Zhong and his colleagues discovered an unexpected pattern. People made more ethical choices on the first 4 vignettes than on the later cases. As people had more time to deliberate, they made choices that were less ethical. Why? The scholars suggest that many of us will arrive at an ethical decision if we make our choices intuitively and automatically. However, when we take time to deliberate, we think about our past behavior. We reflect upon the good ethical decisions we have made. Pondering those good choices makes us feel good about ourselves. We give ourselves “morality credits” for our ethical decisions. However, we also may become more comfortable making a less ethical decision in the current circumstance because perhaps we see it as just drawing upon the credits that we have earned over time. We may come to think of making less ethical choices as akin to withdrawing from a savings account that we have accumulated. In short, taking too much time to deliberate may enable us to rationalize unethical decisions.23

Another stream of research suggests that individuals have a tendency to overcomplicate easy decisions. Scholars Rom Schrift, Oded Netzer, and Ran Kivetz have found that individuals tend to feel that a certain amount of effort should be associated with making a decision. The notion comes from people’s beliefs that hard work pays off and that a lack of effort may have dire consequences. If a decision appears rather easy, we sometimes conclude that the preferred option may be “too good to be true.” Therefore, we overcomplicate the choice to make ourselves feel as though we spent the appropriate time and effort during the decision-making process. Unfortunately, we waste time and energy by overcomplicating some decisions. We might end up selecting a suboptimal option. Even if we do make the right call, we may move far too late and miss a golden opportunity.24

For a brief summary of the three dysfunctional dynamics of indecision described in the preceding pages, see Table 7.1.

Seeking Shortcuts

As executives become frustrated with the tendency for inaction within their organizations, they naturally search for strategies to accelerate decision making. Some managers conclude that decision complexity and ambiguity have paralyzed the organization, and therefore they adopt techniques for simplifying the situation so that they can make a judgment more quickly and easily. For instance, they reason by analogy, apply simple rules of thumb, and imitate other successful organizations. These strategies may help managers make accurate judgments amid a great deal of ambiguity, and they can provide a creative way to break stalemates or open up new ways of thinking about a problem. Moreover, these techniques do not require an overwhelming amount of formal analysis, yet even highly rational and analytical thinkers tend to find these decision-making strategies appealing.

Unfortunately, each of these strategies has serious drawbacks as well. When employing these techniques, many leaders draw the wrong conclusions, make biased estimates, pursue flawed policies, or impede the development of commitment within their management teams. Perhaps more importantly, these decision-making shortcuts do not tackle the fundamental cultural problems that consistently lead to indecision and inaction within an organization. They may enable an organization to arrive at one particular decision quite readily, but in the future, the same dysfunctional patterns of behavior tend to persist.25

Reasoning by Analogy

Business leaders often draw analogies to past experiences when faced with a complex problem for which the organization cannot seem to gain traction or arrive at a solution. They draw comparisons to similar situations or circumstances from their own past or from the history of other organizations, and they induce certain lessons from those experiences.

Consider the case of Lexicon, a firm that creates brand names for client companies around the world. Lexicon-created brands generate more than $250 billion in revenue. Clients look to Lexicon because of its creativity, understanding of consumer trends, and expertise in linguistics. How does Lexicon do its work? Dan Heath and Chip Heath describe how the creative teams examined analogies for inspiration during a project for Levi’s jeans:

Lexicon’s leaders often create three teams of two, with each group pursuing a different angle. Some of the teams, blind to the client and the product, chase analogies from related domains. For instance, in naming Levi’s Curve ID jeans, which offer different fits for different body types, the excursion team dug into references on surveying and engineering.26

John Rau, a former CEO and business school dean, argues that analogies provide a wealth of information: “The fundamental laws of economics, production, financial processes and human behavior and interaction do not change from company to company or industry to industry. Reading about other companies makes me a better decision maker because it provides a store of analogies.”27 Indeed, researchers have shown that people in a variety of fields, from foreign policy to firefighting, reason using analogy. Analogies are especially useful when decision makers do not have access to complete information and do not have the time or ability to conduct a comprehensive analysis of alternatives. They enable people to diagnose a complex situation quickly and to identify a manageable set of options for serious consideration.

Unfortunately, most analogies are imperfect. No two situations are identical. Many decision makers quickly spot the similarities between situations, but they often ignore critical differences. In foreign policy, officials often refer to the “Munich analogy” when making decisions. When confronted with international aggression, many world leaders argue against appeasement by drawing comparisons to Hitler’s belligerence during the 1930s. They argue that British Prime Minister Chamberlain’s decision to appease Hitler in 1938 actually encouraged him to pursue further expansion. Political scientists Richard Neustadt and Ernest May point out, however, that not every situation parallels the circumstances in Europe in the late 1930s. For example, they argue that President Truman would have been well served to identify the differences, as well as the similarities, between Korea in 1950 and Czechoslovakia in 1938. Ignoring these distinctions may have impaired the U.S. strategy during the Korean conflict.28

Business leaders often draw imperfect analogies as well. Take the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, for example. Several market-research firms projected the growth of online advertising by drawing analogies between the Internet and other forms of media. They examined the historical growth in advertising in these industries, and they projected Internet growth by selecting the analogy that they deemed most appropriate. In doing so, they failed to recognize critical differences between the Web and other forms of media, such as television and radio. Similarly, many research firms project the demand for new technologies by drawing analogies to the adoption rates for videocassette recorders, personal computers, and cell phones. Again, the differences between these technologies are often rather striking, yet they receive scant attention.

Strategy researchers Jan Rivkin and Giovanni Gavetti argue that business leaders encounter great difficulty when they begin with “a solution seeking a problem.” Instead of using analogies to search for a solution to a particular problem, executives sometimes begin with a preferred solution in mind. They have a specific framework or model that has worked well for them in the past. Then they try to find new domains in which they can apply their favorite solution. At times, though, they force that solution into situations that are not at all analogous to the circumstances of their prior success.29

Several years ago, former Emerson Electric Chairman and CEO Chuck Knight visited my MBA class. Emerson tended to compete in mature, relative stable markets with proven technologies. The firm had a track record of driving consistent productivity gains in those industries. During his tenure as chief executive, Emerson grew from $1 billion in revenue to over $15 billion. It enjoyed 27 years of consistent profitable growth. Knight attributed the firm’s success to its disciplined strategic planning process. During his presentation to my class, a student asked Knight: “If you were to be hired today by a high-growth firm in Silicon Valley, would you implement Emerson’s management system?” Knight responded that he would be very tempted to apply those proven techniques in Silicon Valley. He explained that you tend to go with what has worked for you in the past. Knight further commented that succumbing to that temptation would likely lead to a terrible failure. He recognized that drawing analogies to his past experience might be enticing, but the competitive and organizational environments simply were too dissimilar.

In sum, reasoning by analogy can be a quite powerful tool. Managers encounter problems not because they choose to reason in this manner but because they often do not select the appropriate analogies.30

Rules of Thumb

In many situations, managers seek to adopt a rule of thumb, or heuristic, to simplify a complicated decision. These shortcuts reduce the amount of information that decision makers need to process, and shorten the time required analyze a complex problem.31 Often, an entire industry or profession adopts a common rule of thumb. For example, mortgage lenders assume that consumers should spend no more than 28% of their gross monthly income on mortgage payments and other home-related expenses. This provides a simple method for weeding out consumers with high default risk. (Abandoning that rule got many lenders in trouble in the years leading up to the 2008 housing market crash). Computer hardware engineers and software programmers have adopted many rules of thumb to simplify their work. Many of us are familiar with one such rule, Moore’s law, which predicts that the processing power of computer chips will double approximately every 18 months.32 Finally, the conventional wisdom in the venture capital industry used to suggest that firms should demonstrate four consecutive quarters of profits before an initial public offering. Alas, many venture capitalists regret having abandoned this rule during the dot-com frenzy of the late 1990s.

In most cases, heuristics enable managers to make sound judgments in an efficient manner. Rules of thumb can be dangerous, however. They do not apply equally well to all situations—there are always exceptions to the rule. Whereas industries and firms employ many idiosyncratic rules of thumb, researchers also have identified several more general heuristics that can lead to systematic biases in judgment. Let’s consider two prominent shortcuts: availability and anchoring. Individuals typically do not conduct a thorough statistical analysis to assess the likelihood that a particular event will take place in the future. Instead, they tend to rely on information that is readily available to them to estimate probabilities. Vivid experiences and recent events usually quickly come to mind and have undue influence on people’s decision making. This availability heuristic usually serves people well. However, in some cases, easily recalled information does not always prove relevant to the current situation and may distort our predictions.

When making estimates, many people also begin with an initial number drawn from some information accessible to them at the time, and they adjust their estimate up or down from that starting point. Unfortunately, the initial number often serves as an overly powerful anchor and restrains individuals from making a sufficient adjustment. Researchers have shown that this “anchoring bias” affects decision making even if people know that the initial starting point is a random number drawn from the spin of a roulette wheel! In sum, many different rules of thumb provide a powerful means of making decisions rapidly, but they also impair managerial judgment when people do not recognize their drawbacks and limitations.33

Imitation

Some business leaders emulate the strategies and practices of other highly successful firms when faced with contentious and complex decisions. After all, why reinvent the wheel? One way to simplify a complex problem is to find out whether someone else has already solved it. Learning from others can pay huge dividends. At General Electric, former CEO Jack Welch launched a major “best practices” initiative in 1988. He credits this initiative with fundamentally changing the way that GE does business and producing substantial productivity gains. Welch and his management team identified approximately 20 organizations that had long track records of more rapid productivity growth than GE. For more than a year, GE managers closely studied a few of these firms. They borrowed ideas liberally from these organizations and adapted others’ strategies and processes to fit GE’s businesses. For instance, they learned quick market intelligence from Wal-Mart and new product development methods from Hewlett-Packard and Chrysler. Over time, imitating others became a way of life at GE, and it produced amazing results.34

All this learning sounds wonderful, but imitation has drawbacks. In many industries, firms engage in “herd behavior.” They begin to adopt similar business strategies rather than develop and preserve unique sources of competitive advantage. Take, for example, the credit-card industry. Many firms have tried to emulate the highly successful business model developed by Capital One. Over time, company marketing and distribution policies have begun to look alike, rivalry has intensified, and industry profitability has eroded. Consider too the many instances in which a leading firm decides to merge with a rival, touching off a wave of copycat acquisitions throughout an industry.35

At times, executives may feel safe imitating their rivals rather than going out on a limb with a novel business strategy. However, the essence of good strategy is to develop a unique system of activities that enables the organization to differentiate itself from the competition or to deliver products and services at a lower cost than its rivals. Simply copying the strategies and practices of rival firms will not produce a unique and defensible strategic position.36 It takes great courage to stand alone when rivals engage in herd behavior, but it can pay huge dividends. Being different does not mean that a firm refuses to learn from others. For instance, General Dynamics studied its rivals very closely during the turmoil in the defense industry in the early 1990s and observed that many firms had decided to pursue commercial diversification to compensate for diminishing military spending. The company’s historical analysis indicated that aerospace firms had not fared well during past diversification efforts. Therefore, it chose to focus on defense despite the precipitous decline in industry demand. Many rivals ridiculed this strategy at the time, yet for the decade that followed, General Dynamics generated shareholder returns well in excess of most large competitors.37

Failing to Solve the Underlying Problem

These decision-making shortcuts—reasoning by analogy, applying rules of thumb, and imitating others—clearly have merits. Despite some limitations and pitfalls that we have identified, these strategies often serve a useful purpose for managers trying to make complicated decisions with incomplete information. However, these techniques do virtually nothing to alter the culture of indecision that often proves to be the true barrier to timely and effective execution within organizations. Tackling a culture of indecision requires leaders to focus not simply on the cognitive processes of judgment and problem solving but also the interpersonal, emotional, and organizational aspects of decision making. Leaders need to change the fundamental way that people interact with one another, both in and out of meetings, if they want to change a culture of indecision. They must teach others how to engage in more constructive and efficient dialogue and deliberation. They also must lead the decision process in a way that fosters commitment and shared understanding—a critical topic that the next chapter addresses.

The Origins of Indecisive Cultures

This chapter has discussed the different patterns of behavior that constitute cultures of indecision. Leaders should keep in mind that those behaviors may contribute to poor performance in the present, but the roots of a culture of indecision often can be traced back to a time when the organization performed remarkably well. Indeed, the very same behaviors that contributed to the firm’s past achievements may have become problematic as internal and external conditions changed.

How does this transformation from a decisive culture to an indecisive one take place? Where do dysfunctional behaviors emerge from similar, yet constructive, patterns of interaction that took place in the past? Take, for a moment, the example of Ken Olsen—the founder and long-time CEO of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). In his fascinating inside look at the company’s history, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Edgar Schein describes Olsen’s decision-making philosophy:

I also observed over many meetings that Olsen had a genuine reluctance to say no. He preferred the group or the responsible manager to make the decision....It was pointed out over and over again in interviews that many of DEC’s innovations were not Olsen’s ideas but that Olsen created a climate of support for new ideas so that subordinates felt empowered to try new and different things.38

Olsen liked to think of the company as a marketplace of ideas, and he felt that the best strategies and decisions would emerge from the conflict and competition in that marketplace. He enjoyed playing the devil’s advocate and probing people’s thinking, but he did not want to dictate choices to his people. Olsen let his people hash out their own differences. The culture embodied Olsen’s management philosophy and style; in other words, his approach to decision making permeated all levels of the firm. The DEC style of decision making worked well during the early years, when the company had little hierarchy and few lines of business, and when everyone knew one another quite well. Over time, however, multiple organizational units emerged, and their interests diverged. People did not know others who worked in different functional areas. The marketplace of ideas began to break down; good concepts had trouble achieving priority and garnering resources, and bad ideas seemed to never die. Affective conflict, political stalemates, and endless recycling of ideas and proposals began to characterize the firm’s decision-making processes. In short, the culture created by Olsen had become rigid, and it did not adapt as needs and pressures from the external environment and internal organization changed.39

Don Barrett experienced a similar problem at All-Star Sports. When Barrett launched the catalog division for the retailer, he had a small management team consisting of people with similar backgrounds and cognitive styles. He could tackle a complex issue one on one with an executive and then bring it back to the team for discussion and ratification, and the others had little reluctance expressing their concerns and objections candidly during staff meetings. However, as the catalog division grew rapidly, the organization became more complex. Through acquisition, the division grew to have multiple lines of business. The management team grew in size, and it eventually had members with different backgrounds, personalities, and leadership styles. When Barrett and others employed the decision-making approach that had worked so effectively in the past, it backfired. The newer members of the management team did not feel comfortable with the online/offline approach, and the group found it difficult to reach closure in a timely manner. The context had changed, and the decision-making culture had not adapted.

This chapter argued that chronic indecisiveness does not simply reflect a problematic leadership style or personality deficiencies of an organization’s leader. The problem tends to be deeply rooted in the tacit, often taken-for-granted, assumptions that people hold about how to work and interact with one another. Indecision often occurs at multiple levels of the firm and across many different functional units or lines of business. Habitual patterns of dialogue and interpersonal interaction are deeply rooted in an organization’s history, perhaps stretching all the way back to the influence of its founders. Such patterns are difficult to change, in part because a variant of that behavior contributed to the firm’s prior success.

As a new leader takes charge and witnesses a tendency for indecision in an organization, he can take the first steps toward transforming the culture by examining how he interacts with his own senior management team. One can begin to alter the culture by modeling desired behaviors as he leads the top team’s decision-making processes, fosters constructive conflict, and yet still achieves closure in a timely and efficient manner. Group members take their cues from those dialogues and deliberations. With some deft coaching and timely feedback, those managers can begin to change how they interact with their subordinates as well. As Ram Charan writes, “By using each encounter with his employees as an opportunity to model open, honest, and decisive dialogue, the leader sets the tone for the entire organization.”40 What, then, are these behaviors that leaders should model for others? How does one foster commitment and shared understanding and ultimately enhance the likelihood of achieving timely closure on contentious issues? For the answer to these critical questions, one must turn the page.

Endnotes

1. M. Gendron. “Beth Israel, Deaconess to merge,” Boston Herald. February 24, 1996.

2. Editorial, Boston Globe. October 8, 1996.

3. Levy’s description of the merger and the subsequent problems at the hospital leading up to his hiring are described, in his own words, in a brief paper case that accompanies the multimedia study that David Garvin and I have developed about the turnaround at the BIDMC. See D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (2003). “Paul Levy: Taking Charge of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (A),” Harvard Business School Case No. 303-008.

4. Russo and Schoemaker (1989) employ the term debating society in their book.

5. R. Charan. (2001). “Conquering a culture of indecision,” Harvard Business Review. 79(4): pp. 74–82.

6. This definition of culture has been developed by Ed Schein, an expert on the subject who teaches at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. See Schein. (1992).

7. L. Gerstner, Jr. (2002). Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? Inside IBM’s Historic Turnaround. New York: Harper Business.

8. Gerstner. (2002). pp. 192–193.

9. The exercise of power plays a vital role in a culture of no. At IBM, the heads of the various business units had a great deal of power, and they could exercise it in the nonconcur process. In some organizations, of course, power is highly centralized, with a large gap between the CEO’s power and that of others on the senior team. In others, the business unit chiefs operate independent fiefdoms, control a vast amount of resources, and they have a large degree of independence. The culture of no is more likely to exist in the latter case.

10. J. Pfeffer and R. Sutton. (1999). “The smart-talk trap,” Harvard Business Review. 77(3): pp. 134–142. Interestingly, the authors argue that management education may encourage smart talk in organizations. They point out that students in MBA programs are rewarded for making clever comments, and they are especially lauded if they offer contrarian views and sharp critiques of ideas presented in the case or by others in the class. Furthermore, Pfeffer and Sutton highlight the fact that the students do not need to implement their ideas to be successful in MBA programs; they need only formulate ideas that sound smart and sophisticated.

11. Pfeffer and Sutton. (1999). p. 138. One interesting study that the authors cite in their article was conducted by Teresa Amabile. She found that book reviewers who offered negative critiques were viewed by others as more intelligent than those who issued positive evaluations. See T. Amabile. (1983). “Brilliant but cruel: Perceptions of negative evaluators,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 19: pp. 146–156.

12. An interesting example of “smart talk” may be the interaction that took place between the finance executives and the manufacturing and engineering managers at Ford in the 1950s. Ford President Robert McNamara had recruited a cadre of “whiz kids”—highly intelligent young people, with stellar academic credentials, who were adept at employing sophisticated quantitative techniques to analyze business issues. In David Halberstam’s book about the auto industry, The Reckoning, he argues that the finance managers were adept at critiquing the plans and ideas of the “car guys,” but their strictly analytical approach also may have stifled innovation and adaptation to the changing business environment in later years. See Halberstam. (1986).

13. Levy speaks about the decision-making problems at the hospital in great detail in a section of the multimedia case study that we have developed. He explains why decisions were not made effectively in the past, as well as how he overcame the “curious inability to decide.” Later chapters of the book explain, in part, how he addressed the problem of indecisiveness at the hospital. D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (2003). “Paul Levy: Taking Charge of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center – Multimedia Case Study,” Harvard Business School Multi-Media Case 303-058.

14. Charan. (2001). p. 76.

15. For more detail on this example, see D. Garvin and M. Roberto. (1997). “Decision-Making at the Top: The All-Star Sports Catalog Division,” Harvard Business School Case No. 398-061. Please note that the names of the company and executives in this case study have been disguised.

16. Jon Katzenbach offers a similar example in his book on senior management teams. See the example about CEO Winston Newberry of Best Fuel Distribution Corporation (disguised case) in Chapter 3 of his book: J. Katzenbach. (1998). Teams at the Top: Unleashing the Potential of Both Teams and Individual Leaders. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

17. A pair of articles describes these findings regarding the link between comprehensiveness and performance in stable vs. unstable environments. See J. Fredrickson. (1984). “The comprehensiveness of strategic decision processes: Extension, observations, and future directions,” Academy of Management Journal. 27: pp. 445–466; J. Fredrickson and T. Mitchell. (1984). “Strategic decision processes: Comprehensiveness and performance in an industry with an unstable environment,” Academy of Management Journal. 27: pp. 399–423. I should note that other scholars disagree with these findings. For instance, Bourgeois and Eisenhardt found that, “In high velocity environments, effective firms use rational decision-making processes.” See Bourgeois and Eisenhardt. (1988): p. 827. However, in subsequent work, Eisenhardt argues that the high-performing microcomputer firms in her sample did not become handicapped by the comprehensiveness of their decision-making processes because they examined real-time information, rather than relying on elaborate planning systems. Moreover, the effective firms examined a wide range of options, but they worked through them simultaneously so as to conserve time. Less-effective firms moved through different alternatives in a sequential fashion. In short, high-performing firms in a turbulent environment tended to act rationally or comprehensively, but they chose strategies that economized on time without compromising decision quality. See Eisenhardt. (1989).

18. Harrison. (1996). The type of marginal analysis described here is often used in economics. For instance, economic theory posits that competitive firms will maximize profits at the point at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In other words, if the incremental revenue of producing one more unit of good does not exceed the incremental cost required to produce it, then the firm will not manufacture that additional unit. For more on the cost of gathering additional information, as well as the optimal level of information search, see K. Brockhoff. (1986). “Decision quality and information,” in E. Witte and H. Zimmerman, eds., Empirical Research on Organizational Decision Making. New York: Elsevier Science Publishers.

19. The Staff of the Corporate Executive Board. “Preventing Analysis Paralysis.” December 20, 2011. www.businessweek.com/management/preventing-analysis-paralysis-12202011.html, accessed December 21, 2011.

20. Janis and Mann. (1977).

21. See George. (1980) and Eisenhardt. (1989).

22. Henry Mintzberg has described the reliance on planning systems in many organizations, as well as the problems associated with an emphasis on formal planning as a means of making strategic decisions. See H. Mintzberg. (1994). The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. New York: Free Press.

23. C.-B. Zhong, G. Ku, R. Lount, Jr., and J. K. Murnighan. (2010). “Compensatory Ethics.,” Journal of Business Ethics. 92: pp. 323–339.

24. R. Y. Schrift, O. Netzer, and R. Kivetz. (2011). “Complicating choice: The effort compatibility hypothesis,” Journal of Marketing Research. 48(2): pp. 308–326.

25. This section draws heavily upon an article that I wrote several years ago about how managers cope with ambiguity in decision making. See M. Roberto. (2002). “Making difficult decisions in turbulent times,” Ivey Business Journal. 66(3): pp. 15–20.

26. D. Heath and C. Heath. (2011). “How to pick a perfect brand name,” Fast Company. www.fastcompany.com/1702256/how-pick-perfect-brand-name, accessed February 15, 2011.

27. J. Rau. (1999). “Two stages of decision making,” Management Review. 88(11): p. 10.

28. Neustadt and May offer an extensive and insightful analysis of the promise and peril of reasoning by analogy, with many vivid historical examples. They also offer a useful framework to help decision makers scrutinize their analogies carefully, so as to avoid drawing inappropriate parallels to past situations. See R. Neustadt and E. May. (1986). Thinking in Time: The Uses of History for Decision-Makers. New York: Free Press.

29. G. Gavetti and J. Rivkin. (2005). “How strategists really think: Tapping the power of analogy,” Harvard Business Review. 83(4): 54–63.

30. My colleagues Jan Rivkin and Giovanni Gavetti have begun exploring the use of analogies in the formulation of competitive strategy within firms. See G. Gavetti and J. Rivkin. (2004). “Teaching students to reason well by analogy,” Journal of Strategic Management Education. 1(2): pp. 431–450.

31. Russo and Schoemaker. (1989); See also M. Bazerman. (1998). Judgment in Managerial Decision Making. Fourth edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

32. G. Moore. (1965). “Cramming more components on to integrated circuits,” Electronics. 38(8): pp. 114–117.

33. Russo and Schoemaker. (1989); Bazerman. (1998).

34. Bower and Dial. (1994).

35. In relation to the pervasive tendency for firms to imitate one another, strategy expert Gary Hamel once offered this rather humorous observation: “In nearly every industry, strategies tend to cluster around some central tendency of industry orthodoxy. Strategies converge because success recipes get lavishly imitated....Aiding and abetting strategy convergence is an ever-growing army of eager young consultants transferring best practice from leaders to laggards....The challenge of maintaining any sort of competitive differentiation goes up proportionately with the number of consultants moving management wisdom around the world.” See G. Hamel. (2000). Leading the Revolution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. p. 49. Many firms do imitate others because they seek to find and emulate best practices. However, sociologists have offered alternative explanations for why imitation of strategies, structures, and processes occurs. They describe the phenomenon by which organizations begin to look more alike as isomorphism. See J. Meyer and B. Rowan. (1977). “Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony,” American Journal of Sociology. 83: pp. 340–363; P. DiMaggio and W. Powell. (1983). “The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields,” American Journal of Sociology. 48: pp. 147–160.

36. M. Porter. (1996). “What is strategy?” Harvard Business Review. 74(6): pp. 61–78.

37. I worked as a financial analyst at the nuclear submarine division (Electric Boat) of General Dynamics Corporation during this time. Many people expressed serious doubts about the strategy pursued by CEO William Anders at the time. They attributed his desire to focus on defense, while gradually selling off units of the aerospace conglomerate, as a strategy being pursued to maximize his compensation under a highly controversial pay-for-performance plan put in place when he was hired. Although Anders did make a great deal of money, the firm also performed remarkably well. Meanwhile, many competitors struggled mightily as they pursued commercial diversification strategies and mega-mergers. General Dynamics has continued to perform near the top of its industry since Anders’s departure, and it is still focused almost entirely on defense. For more on Anders’s controversial tenure at the firm, see K. Murphy and J. Dial. (1993). “General Dynamics: Compensation and Strategy (A) and (B),” Harvard Business School Case Nos. 494-048 and 494-049.

38. E. Schein. (2003). DEC Is Dead, Long Live DEC: The Lasting Legacy of Digital Equipment Corporation. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. pp. 64, 69.

39. Schein (2003) provides a fascinating account of DEC’s rise and fall, combining academic insights with first-hand observations based upon his time as a consultant to the organization over many years.

40. Charan. (2001). p. 76.