4. Stimulating the Clash of Ideas

“Truth springs from argument amongst friends.”

—David Hume

If an organization has become saddled with a culture of polite talk, superficial congeniality, and low psychological safety, how can a leader spark a heightened level of candor? What specific tools can leaders employ to ignite a lively, yet constructive scuffle? To answer this question, let us begin by examining the story of how one chief executive created a decision process that was “confrontational by design.”1

In early 1997, Steven Caufield, the CEO of a leading shipbuilding firm, began to consider the formation of a strategic alliance that would strengthen his firm’s ability to win the intense competition to design and build a new generation of vessels for the U.S. Navy. He wanted to move quickly, having learned his lessons from a bidding war several years earlier. His firm had been “left at the altar” during that competition, when industry teams formed rather quickly, leaving him with few choices for strategic partners. As Caufield and his management team began to discuss potential alliances this time, he became concerned that everyone seemed to be focusing quite narrowly on two options. Moreover, people’s biases, prior allegiances, and emotional feelings about various firms seemed to be taking the place of careful critical thinking. Caufield decided to create a forum for thoughtful deliberation and debate; in short, he set out to start a good fight.

As it turns out, a modest degree of forethought regarding the decision process provided the fuel that ignited a vigorous and thoughtful debate. After spirited deliberations, Caufield struck boldly and quickly to form a powerful three-firm alliance—a move that caught rivals by surprise. The partners went on to win several key contracts. Caufield reflected on how he set the stage for some productive wrangling:

We did a lot of hard work before the key offsite meetings. That was the key. I think my colleagues and I really had some strong brainstorming sessions in which we discussed who the participants should be, what should their roles be, who would facilitate, what process we would use, and what my role would be during the meetings. Going into those meetings, we had a clear understanding of the roles that we were going to be playing, and we knew the process that we were going to follow.

Caufield’s Story

Because a few early signals suggested that the U.S. Navy soon would launch a competition for the design and construction of a new warship, Caufield began to work with several colleagues to design a process for choosing alliance partners. The group decided to invite a select set of company managers as well as outside consultants and aerospace industry experts to a series of offsite meetings. They chose participants carefully to bring together a range of relevant expertise, ensure a diversity of opinions and perspectives, and create a healthy blend of personalities. The group elected two people to serve as facilitators during the offsite sessions, while determining that Caufield should absent himself from the early sessions for fear of inhibiting candid discussion. Caufield wanted the participants to evaluate a range of options and present him with a ranking of the top three potential alliances. He intended to critique the group’s work, ask probing questions, and test their assumptions. Then he hoped to work together with the participants to refine their recommendations and come to a consensus regarding which firm or firms to approach regarding a partnership. Caufield explained his role:

I like to challenge my team to brainstorm in a free and open session, and sometimes when the boss is there, it’s not as free and open as it can be. Then, I can come in and review the process that they went through very quickly and examine their recommendations. I’m now challenging their thought process, and in turn, I’m inviting them to challenge mine.

Having defined people’s roles, Caufield and his colleagues set out to develop a wide-ranging list of alternatives that should be discussed at the meeting, knowing that earlier discussions had been overly constrained. After consultation with people throughout the organization, the group came up with nine possible combinations, including a few that appeared rather unlikely to succeed, at least at first glance. The facilitators also developed a list of criteria for evaluating each alternative. Caufield clearly wanted multiple criteria to be evaluated simultaneously at the offsite sessions. He had become frustrated with earlier discussions in which each executive tended to focus on a single issue of importance to him, and therefore, would jump quickly to an option that performed well along that narrow dimension. In the end, the group agreed on a list of six key evaluation criteria. For instance, the delivery criterion focused on a potential partner’s track record in delivering products on schedule and under budget, and the “impact to other work” criterion examined how each potential alliance might affect the firm’s relationships with partners and subcontractors on other programs.

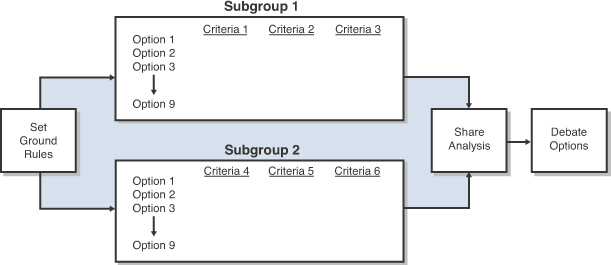

As for how to debate the options, Caufield and his colleagues made a decision to create two subgroups, although these teams operated a bit differently than those in the Kennedy case. The first subgroup evaluated all nine alternatives along three specific criteria, whereas the second examined the options based on the other three factors. By designing the process this way, Caufield and his colleagues hoped that the two teams would bring different information and perspectives to a final debate. Moreover, they wanted each subgroup to listen to how the other side had evaluated each alternative before becoming wedded to a particular course of action. After the teams had narrowed the field to a few preferred options, Caufield joined the participants to listen, probe, and question all conclusions. He explained the rationale for selecting this approach:

We selected the individuals on the two groups to give a spread of expertise and viewpoints, so that we wouldn’t get a pre-ordained answer [out of either subgroup]....The mission was to try to remove as much of the bias and emotion as we could...By forcing people to take each of these criteria and discuss them, we felt that we could at least force people to render an honest perspective, to engage in an honest debate. But in order to get everybody on the same baseline, we decided that we had to define each one of these factors or criteria.

Indeed, at the outset of the meetings, the facilitators distributed detailed definitions of each criterion to all the participants, and they established a simple 1-to-5 rating system for evaluating the options along each dimension. These actions constituted a concerted effort to ensure that people spoke a common language rather than “talking past one another.”

Perhaps most importantly, the facilitators laid out a process roadmap at the outset (see Figure 4.1), including a set of ground rules to guide behavior. They encouraged people to listen carefully, “pull no punches” during the debates, offer unvarnished opinions to Caufield, and stick to fact-based arguments with concrete supporting evidence. Caufield initially set the tone by asking everyone not to try to anticipate what he wanted to hear. He reminded participants that they were asked to participate because he valued their expertise and judgment. He wanted all the risks and weaknesses on the table before making a decision. Caufield’s rallying cry: “I want everything on the table. No idea is a stupid idea. Every idea is a good idea.”

Pulling All the Right Levers

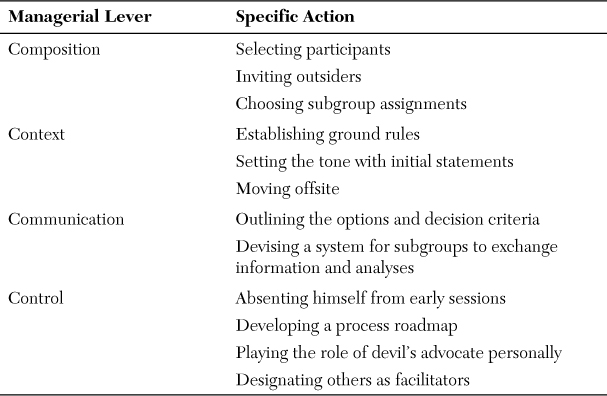

Caufield’s story demonstrates how a leader can use each of the four Cs—composition, context, communication, and control—to sow the seeds for a fruitful debate and an effective decision-making process (see Table 4.1). With regard to composition, Caufield took great care selecting the participants, even working with the facilitators to think about whom to assign to each subgroup. Caufield did not limit membership to his direct reports. Moreover, he did not define diversity in terms of demographic differences; instead, he thought carefully about the proper balance of insiders versus outsiders, the range of expertise upon which to draw, and the mix of personalities around the table. Caufield sought true diversity of cognitive style and perspective, not simply a heterogeneous set of résumés and biographies.2

Setting the right context became a critical part of the process design. Moving offsite helped eliminate distractions and create an open atmosphere. By not attending the early sessions, Caufield signaled his desire to foster a candid discussion. His initial statements—such as “no idea is a bad idea”—further emphasized his willingness to hear unconventional or unpopular views. The ground rules reminded participants what was expected of them during the process.

By creating subgroups, outlining the options, and defining the evaluation criteria, Caufield and his colleagues determined how participants should communicate with one another. Their process choices spurred a great deal of divergent thinking in the early stages. In many cases, managers foster conflict to ensure the generation of multiple alternatives. Interestingly, in this situation, that dynamic functioned in reverse: Caufield put a wide range of options on the table and asked participants to consider each one carefully in order to spur a greater divergence of thought and perspectives than had occurred in earlier discussions. By asking the group to even consider some options that seemed highly unlikely, Caufield hoped to move people outside their comfort zones and encourage the generation of some altogether new options—an event that did transpire during the deliberations. The criteria definitions facilitated smooth communication during the oft-heated debates by ensuring that everyone was “speaking the same language” and “comparing apples to apples” when arguing about the alternatives.

Finally, Caufield chose to take control of how the debate should take place, but he did not constrain the content of the deliberations a great deal. He welcomed a lot of input regarding the list of options and evaluation criteria, and at the outset, he chose not to express his own views about how to proceed. Moreover, Caufield defined his own role very clearly. He set the tone early and then absented himself for awhile before returning to play the devil’s advocate. By designating two facilitators, he ensured that others would be drawing out comments from those who might be more reluctant to offer dissenting views, while not putting himself in a highly interventionist role. Finally, Caufield made it clear that he would seek consensus within the group but that ultimately, he would make the call if people could not reach agreement.

Here then, we have a vivid example of how a leader can develop a clear roadmap for a decision process in a manner that encourages vigorous debate rather than making people feel as though he aspires to reach a predetermined outcome. One should note that Caufield did not perform this critical design work alone. He gathered input from many people and gave the facilitators the freedom to guide the debate. Perhaps most importantly, all participants understood the goals and stages of the process, as well as how they were expected to behave.

The Leader’s Toolkit

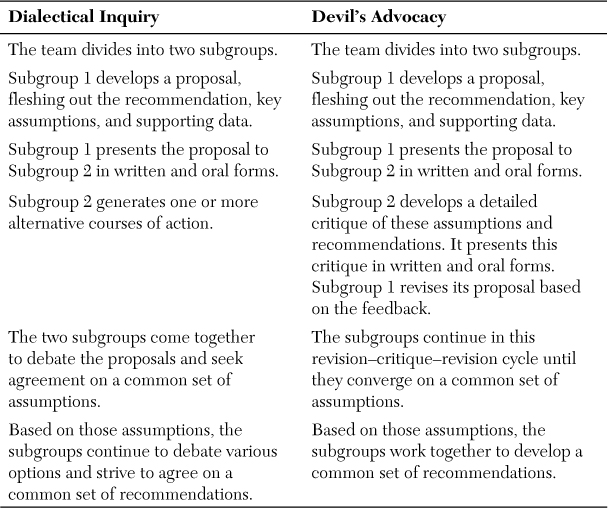

Setting the stage for a vigorous debate requires leaders to take a holistic view—pulling multiple levers simultaneously to shape an effective process. Having said that, we have seen that specific tools and techniques—such as Dialectical Inquiry or Devil’s Advocacy—can play a particularly important role in helping to foster conflict and debate. Often, leaders begin by deciding on a particular technique that they wish to employ, and then they build the rest of the process around that creative mechanism for sparking divergent thinking.

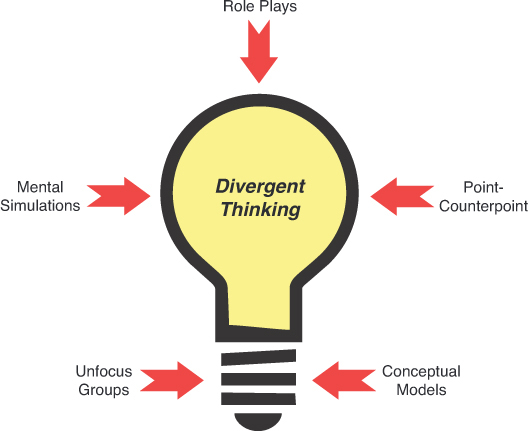

What, then, are some of the techniques that leaders may employ? In general, leaders may draw upon five types of tools to encourage divergent thinking, which often naturally leads to more conflict and dissent (see Figure 4.2). First, they can use role-play methods to ask managers to put themselves in others’ shoes. Second, leaders may employ mental simulation techniques, in which they encourage people to imagine the future and think through how events may unfold in different ways over time. Third, leaders can conduct an “unfocus group” to explore a challenging question or topic. Fourth, leaders can ask people to examine an issue using a diverse set of conceptual models and frameworks. Finally, leaders may create a point–counterpoint dynamic of some kind, much like Kennedy and Caufield chose to do. As leaders employ these techniques, they must remember that some methods will work better than others in particular settings and with specific individuals. They must evaluate the situation and the group with whom they are working and then select the techniques that they believe will work best in those circumstances.3

Role-Play Methods

In professional football, teams put themselves in their rivals’ shoes all the time. During a typical week of practice, the players in the starting lineup practice against a “scout team” consisting of second stringers who simulate the plays and schemes typically utilized by the upcoming opponent. As practice takes place, the coaches often gain a better understanding of what works and does not work against that rival. They invent improved strategies, scrap certain plays, and think of new ways to surprise the opponent during the game. Coaches and players often marvel at the benefits of having someone who can imitate a rival to near perfection. For instance, after the New England Patriots defeated the Indianapolis Colts in a critical 2004 playoff game, the winning coach, Bill Belichick, praised a team member who never stepped on the field that day; he singled out backup quarterback Damon Huard, who simulated the behavior of Colts’ star quarterback Peyton Manning during the entire week of practice. With Huard’s help, the coaches devised some “new wrinkles” on defense that confused Manning during the game.4 After the victory, Belichick told the press, “I thought one of the most valuable players in the game for us didn’t play, and that was Damon Huard. I thought the look he gave us in the scout team for our defense was fabulous.”5

Business executives can role play their competitors as well. My research suggests that these exercises often lead to new ways of thinking about the firm’s competitive strategy and a much richer debate.6 For instance, when one of the country’s leading armored combat vehicle manufacturers began thinking about the formation of an international joint venture, a group of executives tried to simulate the actions of a set of firms that might form a competing alliance. The exercise sparked new debate, shed light on their own venture’s weaknesses, and generated new insights about rival behavior. One manager even made the analogy to the scout team in professional football:

We actually had someone role play the other alliance that was forming, and they did a competitive assessment of us, just like a football team. You know, you scrimmage using the other guy’s plays. The results portrayed the other alliance’s view of us, and it was very revealing.

Role-play exercises need not focus strictly on the notion of stepping into a rival’s shoes; often, it helps to imagine someone moving into your office and taking your job. In the early 1980s, Intel experienced a substantial decrease in its market share in the memory-chip business; soon, the financial losses began to mount. However, senior executives remained highly committed to the product line; they had cut their teeth in that business as Intel became a leader in the industry. Memory chips represented a core aspect of the firm’s identity and, to some extent, the identity of the managers who built that business. As the losses escalated, company President Andrew Grove sat in his office with Chairman and CEO Gordon Moore. Grove looked out at a Ferris wheel in a nearby amusement park, and he asked Moore: “If we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO, what do you think he would do?”7 Soon, the two men realized that they were throwing good money after bad in the memory-chip business. They had become overly committed to a product line in which they had invested a great deal of money as well as much of their own time and personal reputation. Grove and Moore decided to exit the memory-chip business. Grove explained how the simple role-play exercise encouraged them to think differently, question many of their assumptions, and explore new strategic alternatives:

New managers come unencumbered by such emotional involvement....They see things much more objectively than their predecessors did. If existing management want to keep their jobs when the basics of the business are undergoing profound change, they must adopt an outsider’s intellectual objectivity....That’s what Gordon and I had to do when we figuratively went out the door, stomped out our cigarettes, and returned to do the job.8

Research shows that getting out of our own shoes can help us think more creatively. Consider a fascinating experiment conducted by scholars Evan Polman and Kyle Emich. They gave over 100 undergraduate students this tough riddle to solve:

A prisoner was attempting to escape from a tower. He found a rope in his cell that was half as long enough to permit him to reach the ground safely. He divided the rope, tied the two parts together, and escaped. How could he have done this?9

The scholars asked half of the students to imagine themselves in this predicament. The other half tried to picture someone else trying to escape the tower. Amazingly, a much higher percentage of students solved the puzzle when trying to imagine someone else trapped in the tower. Polman and Emich contend that we adopt a narrower perspective and think very concretely when solving our own problems. We look at problems from many different vantage points and think more abstractly when placed in others’ shoes.10

Oral Roberts Professor David Burkus has discovered one leader who developed a technique for forcing people to step out of their own shoes. Burkus describes how consultant Lisa Bodell runs an exercise called “Kill the Company.” Many executives ask their teams to conduct a traditional SWOT analysis, whereby they generate lists of the competitive threats and opportunities facing the firm. Bodell takes a different approach. She will ask a management team to imagine a rival that is almost identical to their firm. Then she directs them to think about the threats and opportunities facing that hypothetical company. She asks them how that firm could end up bankrupt. Like people imagining someone else trapped in a tower, the executives who conduct the “Kill the Company” exercise tend to generate many more interesting ideas than those who simply perform a traditional SWOT analysis.11

Mental Simulation

Psychologist Gary Klein has found that many people simulate future scenarios rapidly in their mind as they make critical decisions. For instance, he found that firefighters often do not have the time to compare and contrast multiple alternatives while in the midst of battling a raging blaze. However, they often identify a plausible course of action and then mentally simulate how events will unfold if they pursue that strategy for fighting the fire. If the simulation yields a favorable result, they take action; if not, they search for a new alternative.12

It turns out that asking people to imagine different future states and to discuss those mental pictures with one another can be a powerful tool for sparking debate within organizations. Many managers have heard about scenario planning, a formal strategic planning technique practiced and refined for years by firms such as Royal/Dutch Shell. It involves a structured method for thinking about how industry conditions might unfold in very different ways in the future, and then considering how a variety of strategic alternatives might play out under those contrasting conditions. At Royal/Dutch Shell, it meant conceiving divergent paths for global energy markets, and then thinking about how those changes would affect oil prices, consumption patterns, and rival behavior.13 Stanford Professor Kathleen Eisenhardt has argued that scenario thinking fosters constructive conflict within top management teams. She explains that “scenario thinking forces executives to start with the future and think backward to the present. This reversal of normal linear thinking provides an alternative lens and yields an unusual and unexpected perspective on strategic issues.”14 University of Virginia Professors Leslie Grayson and James Glawson acknowledge that scenario building may not tell managers which strategy to pursue, but it does spark new debate and causes people to surface and reexamine many basic assumptions.15

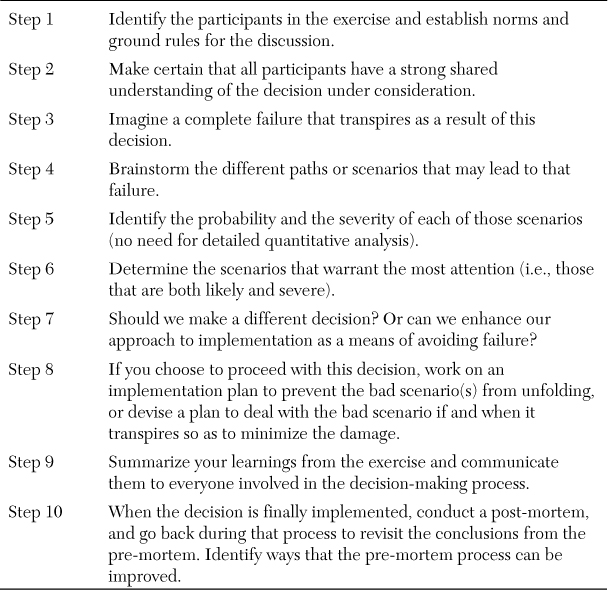

Klein has taken a different, but equally effective, approach to using mental simulation as a mechanism for encouraging divergent thinking within organizations. He advocates the use of a simple “pre-mortem” exercise to help people test one another’s beliefs regarding the risks and obstacles that may occur if the firm chooses a particular course of action. Here’s how it works. You begin by picturing what complete failure would look like. Then you imagine the different paths that may lead to that total failure and consider the probability that each of these scenarios might actually take place. This discussion should generate a prioritized list of the most substantial concerns and risks associated with the decision. Finally, the group must determine whether these pitfalls can be avoided or whether the organization should choose an entirely different course of action.16 Like Klein, I have found that this simple, structured exercise often makes people feel more comfortable critiquing their colleagues’ ideas and plans, particularly if a firm adopts this approach on a routine basis. For more on how to perform a pre-mortem, see Table 4.2.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) uses a variation of the pre-mortem exercise when conducting intelligence analysis. The CIA calls it “thinking backwards.” Analysts imagine that some unexpected event has taken place in the future. Then they reason backward, considering the events that must have transpired leading up to that event. What might have taken place six months earlier to precipitate this unlikely incident? What chain of events over time could lead to this surprising result in the future? Remember that many leaders focus on trying to predict the future. In a thinking backwards exercise, intelligence analysts do not begin by debating the likelihood that certain dangerous situations will emerge in the future. They do not jump into the prediction game. Instead, analysts try to understand how a variety of treacherous scenarios might unfold, even if initial assessments indicate that those scenarios are unlikely to transpire. The exercise tends to open their minds to new possibilities that they may not otherwise have considered.17

Amazon employs its own version of this exercise. They call it “working backwards.” Ian McAllister of Amazon explains:

There is an approach called “working backwards” that is widely used at Amazon. We try to work backwards from the customer, rather than starting with an idea for a product and trying to bolt customers onto it. While working backwards can be applied to any specific product decision, using this approach is especially important when developing new products or features. For new initiatives a product manager typically starts by writing an internal press release announcing the finished product. The target audience for the press release is the new/updated product’s customers, which can be retail customers or internal users of a tool or technology. Internal press releases are centered around the customer problem, how current solutions (internal or external) fail, and how the new product will blow away existing solutions.18

Amazon imagines the future by writing that press release. Managers must envision what the key product features will be, how they will market the product in a compelling way, what the target market will be, and how customers and competitors will respond. They do not simply write one press release. Managers engage in multiple iterations, based on the feedback and input they receive from others in the organization. This imaginative, iterative process yields many new options and ideas for various products and services. The process also sharpens ideas. Mangers must communicate their concepts crisply and concisely. If they cannot, then they come to the realization very quickly that they do not have a clear strategy.

The Unfocus Group

Many companies employ focus groups during the product development process. Focus group sessions may help you refine some ideas, particularly if you are considering incremental changes to existing products. However, traditional focus groups rarely help you produce breakthrough concepts. They often fail to generate creative inspiration. Participants can react to something tangible and incremental, but they have a much harder time envisioning and discussing a radical break from the status quo.

IDEO, a product design firm, tends to eschew the traditional focus group for these reasons. It prefers to conduct observations and interviews of people in their natural environments. IDEO designers derive inspiration from watching how people actually behave rather than listening to them in a sterile and artificial setting. However, IDEO has created a technique that founders David and Tom Kelley call the “unfocus group.” This concept promotes divergent and potentially breakthrough thinking. Traditional focus groups consist of “typical” users of a product or service. For an unfocus group, IDEO invites people who are anything but normal. The firm describes these people as “extreme users.” Tom Kelley explains how IDEO used this technique to design a new shoe for a client:

Among others, we included in the “unfocus” group someone who had a shoe fetish and someone else who was a dominatrix. Clearly they aren’t in the wide part of the random bell curve commonly known as “normal.” The process involved having these very unusual people tell their stories, and think out loud about what kind of new products or services they would like to have. By looking at the needs of people at the edge of the distribution curve we sometimes find hints and clues about how we can ratchet their ideas back a bit and serve the big market in the center of the distribution curve. The “unfocus” group is not going for normalcy, not going directly for the center of the distribution curve. It’s going for the tails but getting insights that can be applied to the big markets in the center.19

These users certainly sound quite unusual, but the insights derived from this type of research often prove illuminating. The folks in the tails of the distribution often exhibit incredible passion about a product, and they have extensive knowledge about the features that they look for as they make purchase decisions. You must remember, though, that you should not expect them to provide you the next big product idea. What these abnormal users suggest often will not help you appeal to a mainstream audience. However, the unfocus group can provide inspiration. Its members can help you think differently.

Conceptual Models

Occasionally, leaders may find it useful to introduce a simple set of models or frameworks that may be applied to a particular business problem and then designate people to use these different lenses during the decision-making process. The objective is to induce each person to launch his inquiry from a different vantage point. When people come together to share their ideas and analysis, they often discover that they have arrived at different conclusions regarding how the firm should proceed.

Kevin Dougherty, the head of Sun Life’s Canadian Group Insurance subsidiary, adopted a version of this technique several years ago. At the time, Sun Life executives worried a great deal about how the Internet might revolutionize the way that consumers procured insurance and other financial-management products. Unfortunately, Dougherty and his management team did not have a great deal of expertise in the area of e-commerce. Most managers seemed to think of the Web as a useful tool for making business processes more efficient, but they had not considered how it might lead to fundamentally different business models in the financial-services industry.

Dougherty asked a consultant to provide his management team with a broad overview of e-commerce trends. Then the consultant described four e-commerce business models. For example, he explained the auction models employed successfully by firms such as eBay and Priceline.com. Then Dougherty divided everyone into four teams, and he assigned each group to consider how one particular model might apply to the insurance business. He also asked them to investigate how that model might present a strategic opportunity or threat for Sun Life. Based on what they learned from this evaluation, each team had to develop a proposal for a new venture, product, or service. Bruce Kassner, assistant vice president of underwriting, explained his experience with the process: “Forcing me to stay within a specific model made me think a bit differently than I would have otherwise. It made me see some value in a model that I wouldn’t have seen value in, had I been free to generate any type of business idea.”20

Some managers see this technique as overly directive because it ties them to a particular conceptual lens. Thus, leaders may try a variation of this technique, in which they ask people to apply a variety of conceptual lenses to an issue, without constraining each individual to one specific problem-solving approach.21 While some may still feel that this approach channels people’s thinking too much, it may be necessary in cases where managers need some help getting started with their analysis or where everyone seems to be thinking in lock step with one another at the outset. Moreover, leaders need to remember that this technique provides a useful way to jumpstart debate, but they need not remain wedded to the approach throughout the process.

Point–Counterpoint

The Kennedy and Caufield examples show the power of employing variants of the Dialectical Inquiry and Devil’s Advocacy methods described in detail in Chapter 2, “Deciding How to Decide.” (For details on how to employ these two techniques, see Table 4.3.) Indeed, many successful leaders have adopted similar techniques because they provide a very direct way to induce conflict. For instance, at Polycom, CEO Robert Hagerty occasionally has employed “red teams” and “blue teams” to scrutinize a potential acquisition. As Hagerty says, “I assign a red team to come up with the reasons why we shouldn’t do the deal. The blue team presents the argument for the acquisition. It is an effective way to institutionalize naysayers.”22

In some organizations, leaders have chosen to institutionalize the point–counterpoint approach. They have built it in to the organizational structure so that a natural tension exists between people who occupy different positions within the firm. Consider, for example, how Electronic Arts, a leader in the video-game industry, manages the product development process. Most of its rivals appoint one person with total responsibility for overseeing the design of a new game. Electronic Arts has created two separate leadership roles. Each person maintains distinct areas of accountability. The producer focuses on product quality, building a creative game that can be enjoyable for consumers to play. The development director tries to come in under budget and on schedule. Paul Lee, former chief operating officer of Worldwide Studios at the firm, describes the purpose of this unique organizational structure:

We have created a system of checks and balances or creative conflict. The producer focuses on ensuring that the game design is the best....The development director focuses on project management, budget, schedule, on-time delivery, etc. And they clash. We force that conflict and that discussion so that the team will push the envelope.24

Electronic Arts did not invent the concept of designing conflict into the organization, nor is the technique confined to business enterprises. In fact, President Franklin Roosevelt took the practice to quite an extreme in the 1930s. He often provided subordinates with overlapping assignments and jurisdictions so as to induce competition and conflict. Moreover, he intentionally provided Cabinet heads and advisers with ambiguous definitions of their roles in his administration. Political scientist Alexander George has written that this organizational model sparked some very creative debates within the Roosevelt administration, but it also fostered an environment that appeared chaotic at times.25 For that reason, leaders should mimic Roosevelt’s extreme approach at their own peril. Only someone with Roosevelt’s masterful political skills could manage such a complex set of relationships. Nevertheless, the core concept of building tension into the design of job responsibilities merits close attention.

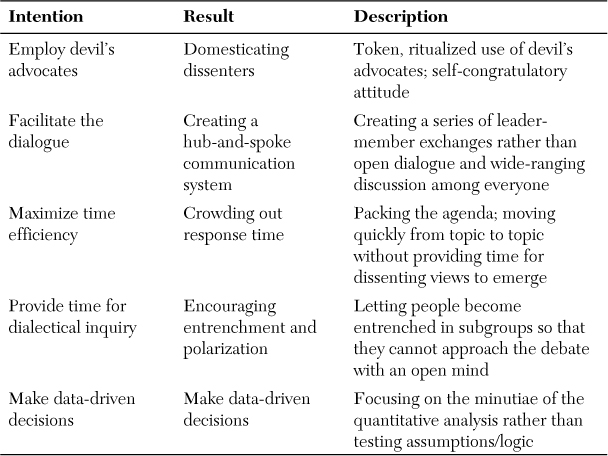

“Watch Out” Situations

As leaders strive to create a process characterized by vigorous debate, they undoubtedly encounter a number of pitfalls—situations that seem to scream “watch out!” In many instances, leaders take some care to “decide how to decide” before trying to tackle the problem. They even employ many of the techniques that we have discussed for stimulating divergent thinking. However, despite good intentions in many cases, leaders manage to send the wrong signals to their advisers, and they fail to realize the full potential of the techniques they have chosen to employ. Worse yet, they may handle situations so poorly that they squelch dissent going forward. Let’s take a look at a few of these common mistakes that leaders make (see Table 4.4).

Domesticating the Dissenters

In James Thomson’s insightful analysis of President Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam, he argues that several key advisers played the role of devil’s advocates, but they became “domesticated” over time. For instance, Johnson used to refer to Thomson, who served in the administration, as his “favorite dove.” Over time, Johnson’s warm and humorous treatment of Thomson’s strongly held views neutralized his effectiveness as an ardent critic of the administration’s policy. Johnson gave several dissenters—George Ball, Bill Moyers, and Thomson—the opportunity to speak their minds on a regular basis, but he seemed to treat them as “token” dissenters. Turning to the devil’s advocate became an empty ritual during meetings. Johnson seemed to enjoy having them occupy the designated role of a devil’s advocate, as if it made him and other proponents feel good to have created an institutionalized mechanism for the expression of dissent.26 As Irving Janis has written, it was as if Johnson and his supporters could “pat themselves on the back for being so democratic about tolerating open dissent.”27 The use of devil’s advocates enhanced the legitimacy of their decision process, even though it was not contributing to better-quality decisions.

Learning from this tragic situation, leaders need to be mindful of the ritual use of devil’s advocates, particularly if the same person occupies that role over time. It can become a routine exercise to satisfy a procedural requirement rather than a legitimate attempt to hear dissenting views. Janis has suggested that leaders can avoid this pitfall by rotating the role of devil’s advocate within an executive team.28 Alternatively, the leader may occupy the role at times, as Caufield did in the strategic alliance decision.

Creating a Hub-and-Spoke System

When leaders spark debate within their management team, they need to be mindful of how they position themselves within the flow of dialogue. Leaders can choose a “hub-and-spoke” model of communication, in which people aim their arguments at the leader during a debate, trying primarily to persuade him of the merits of their positions. Managers do not actually engage in give-and-take; instead, the dialogue becomes a series of leader–member conversations. The debate becomes a fragmented series of one-on-one dialogues. Subordinates begin to frame their comments in anticipation of what the leader wants to hear, or they become silent if they worry excessively about having to engage in a direct exchange with their boss.

Alternatively, a leader can employ a “point-to-point” system of communication, in which he encourages advisers to interact repeatedly with one another rather than routing their arguments through him. The latter system often creates a much more creative exchange of ideas, and it enables the leader to step back, hear the give-and-take among advisers, and compare and contrast the arguments with some objectivity. Subordinates tend to listen more carefully to one another, and they improve their own proposals based upon the critiques posed by others. The debate moves more quickly, and people tend to build off each other’s ideas quite effectively. During the Cuban missile crisis, Kennedy fostered a great deal of point-to-point communication among his staff members. Contrast that with Lyndon Johnson’s approach to decision-making about Vietnam, in which advisers often focused nearly all their attention on the president, seeking to persuade him to adopt their point of view.

Crowding Out Response Time

Leaders often find themselves trying to run meetings as efficiently as possible, given their hectic schedules and the multitude of topics that need to be covered at each gathering. Unfortunately, agenda overload, coupled with the quest for efficiency, often works against a leader’s best efforts to stimulate debate.29 Efficiency goals must be balanced with the objectives of making a high-quality decision and building commitment to the chosen course of action.

Why does efficiency crowd out debate? For some dissenters, it takes some time to gather the courage to express their views or to determine precisely how they would like to articulate their point. Others may want to listen to others and gain a better understanding of the issues before offering their views. The rapid pace of the discussion may become discouraging to those who are not comfortable “shooting from the hip” as soon as a new topic opens.

The Columbia space shuttle incident provides a vivid example of this phenomenon. The Mission Management Team meetings moved quickly from one topic to another during Columbia’s final mission. Each meeting had a packed agenda. The leader asked for input but often coupled that with a statement of her beliefs on the subject, while not waiting more than a few moments to allow people raise questions or concerns.30 Brigadier General Duane Deal, a member of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, has noted that the pace and tone of the meetings became intimidating to employees who had some concerns but were struggling to process confusing and ambiguous information.31

Encouraging Entrenchment and Polarization

Some leaders overcompensate when it comes to the efficiency of the decision process. When employing competing teams in a Dialectical Inquiry type of process, leaders often make the mistake of allowing managers to spend too long in their subgroups prior to bringing everyone together to debate all the options. The leaders mean well; they simply want to provide participants ample opportunity to investigate a particular alternative and to consider its pros and cons thoroughly. Unfortunately, over time, people become heavily invested, cognitively and emotionally, in the option that they have been examining.32 Naturally, they find themselves less willing to entertain other options or to hear criticism of their proposals. Furthermore, as people work closely together over time, they may begin to associate more closely with their subgroups as opposed to the full team. They may start to perceive subgroup members in a very positive light, while taking a more critical view of those colleagues who are members of the other subgroup. Those distinctions can impede communication and make it difficult for people to reach compromises. Debates can become highly contentious.33

Wharton scholars Jennifer Mueller and Julia Minson conducted an interesting study regarding the tendency of small groups to become insular and reject outside advice. They compared how pairs of people, as opposed to individuals working alone, responded to outside input. The individuals and the pairs in the study gave initial responses to a series of questions such as “What percentage of members of Congress are Catholic?” Then they had an opportunity to revise their estimate based on outside input. As expected, the pairs demonstrated higher accuracy during their initial responses. Two heads indeed proved better than one. However, the discrepancy in accuracy disappeared after the opportunity to incorporate outside input. Why? The individuals working alone tended to adjust their responses more so than the pairs. The scholars conclude that small groups can be inward focused at times and, thus, they can reject good outside advice. Why? One reason may be that an in-group versus out-group dynamic emerges. People develop an affinity with fellow members of their small subgroup. Those group members spend time bolstering each other’s confidence in the initial judgments they have made. As a result, they marginalize or dismiss the views of outsiders.34

This dynamic emerged quite vividly during a leadership development program in which I was involved several years ago. Amy Edmondson, the facilitator for this particular session, invited a small group of participants to the front of the room to conduct a team exercise called the Electric Maze. The Electric Maze consists of a carpet with a battery-powered programmable alarm module. Each square in the carpet has pressure-sensitive switches. For most squares, an alarm will sound when a person steps on it. However, one safe path exists from one side of the carpet to another, whereby an individual can walk only on squares that will not sound an alarm. The small group needed to determine the safe path and get all members to traverse it. Edmondson gave the group members some time to discuss their strategy. Then she gave the others in the room an opportunity to give the group at the front some advice and input. By that point, the small group had become quite fixated on the strategy that they had begun to devise. The planners at the front paid very little attention to the others’ suggestions! Some members continued to talk to each other rather than listen to the outsiders’ ideas. Others responded defensively, in a rather knee-jerk fashion, with reasons why the suggestions did not make sense. An in-group versus out-group dynamic prevented a productive exchange of ideas from occurring.

Striving for False Precision

Many organizations perform a great deal of formal analysis during critical decision-making processes. If possible, managers try to quantify as many of the costs and benefits associated with alternative courses of action as they can. Quantitative data can certainly facilitate the comparison of various options, and they can help ensure that debates remain fact based and logical rather than degenerating into purely emotional confrontations. Moreover, quantitative analysis tends to lend an air of legitimacy to the decision-making process; it helps convince others inside and outside the organization that managers went through a thoughtful analysis prior to choosing a course of action.35

Unfortunately, the strong desire to quantify as many aspects of a decision as possible occasionally distracts people from the real issues. Managers begin to argue about minor differences of opinion regarding the numbers rather than addressing fundamental problems associated with one or more alternatives. People’s time becomes consumed with attempting to generate as precise a number as possible. However, the high degree of uncertainty about future events makes such efforts at precision rather futile and perhaps even counterproductive.

Think for a moment about a typical acquisition decision. Managers often spend an inordinate amount of time trying to perfect the financial model that forecasts the cash flow in the years ahead. However, as Polycom Chief Financial Officer Mike Kourey has said, “At the end of the day, many discounted cash-flow models turn out to be bogus. With the right assumptions, any deal can appear promising. That is why we test the assumptions carefully.”36 Unfortunately, many firms tinker endlessly with the financial model, without probing the underlying strategic and operational premises that lie behind the cash-flow forecasts. As attention focuses on minor variations of a financial forecast, those who may have questions regarding the strategic logic behind the acquisition may not feel comfortable raising those questions. They may conclude that the decision has been made to go forward, and managers are now simply trying to determine the right price to pay for the target firm.37

Practice Makes Perfect

Encouraging conflict can indeed be a tricky endeavor; as we have seen, leaders often inadvertently discourage dissent and diminish the effectiveness of a debate. Fortunately, practice does make perfect—or at least substantial improvement—when it comes to managing conflict. Researchers David Schweiger, William Sandberg, and Paula Rechner have examined how groups perform as they employ the Devil’s Advocacy and Dialectical Inquiry techniques repeatedly over time. As you may expect, groups benefited from experience in this experimental study. As teams utilized the techniques more often, they engaged in higher levels of critical evaluation and made better-quality decisions (as measured by a panel of expert judges). The time required to reach a decision diminished with experience. Furthermore, people expressed a higher level of satisfaction with the processes, fellow team members, and final decisions as they gained more experience with these techniques.38

Several very successful business leaders, such as Jack Welch and Chuck Knight, have demonstrated how important it is to make vigorous debate the norm, rather than the exception, within an organization. As people engage in debate on a regular basis, in a wide range of settings within the firm, they become more comfortable with conflict. At General Electric, everyone quickly came to understand the type of dialogue that Welch intended to foster, and they learned how to engage in a heated, yet productive, debate with him. Colleagues recognized that “Jack will chase you around the room, throwing objections and arguments at you” and that “If you win [an argument], you never know if you’ve convinced him or if he agreed with you all along and he was just making you strut your stuff.”39 Welch reinforced these impressions by declaring “constructive conflict” one of GE’s core values, something about which he talked early, loudly, and often.40

Chuck Knight, Emerson Electric’s long-time CEO, designed confrontation into the company’s infamous strategic planning process. The planning conferences represented the focal point of this process. At a series of one- or two-day meetings, Knight and several other corporate officers met with the managers of each division at the firm. During those conferences, Knight pushed people very hard to defend their strategies. Over time, the combative mood of these conferences became part of company folklore. Knight even coined a phrase to describe the process that he often used to stimulate divergent thinking. The “logic of illogic” referred to how Knight asked unconventional, even illogical, questions to test the assumptions and the logic behind every strategic plan. Over Knight’s nearly 30-year tenure as chief executive, the confrontational mood of the planning conferences became part of the culture. That is, it became one of the “taken-for-granted” assumptions about “how we do things around here”—not simply in planning conferences but in all forums for dialogue and deliberation. Knight maintains that managers became more comfortable with the confrontational nature of the planning process as they gained experience with it. They learned how to prepare for the meetings, how to respond to critiques of their plans, and how to handle contentious situations. They learned how to use conflict to make better decisions.41

Knight and Welch made conflict a way of life in their organizations. Unfortunately, some leaders try to draw upon techniques for stimulating divergent thinking on a few special occasions, perhaps when the stakes are unusually high. In most other instances, they run fairly low-key, polite meetings in which their employees feel quite comfortable. When they try to ignite a vigorous debate, without much personal or organizational experience in this area, they either fail to generate conflict as they intended to do, or the dispute becomes highly dysfunctional.

Edwards Lifesciences, a leading manufacturer of heart valves, recognized several years ago that it needed to create a safer environment for people to engage in candid give-and-take. CEO Mike Mussallem and Human Resources Vice President Rob Reindl believed that constructive conflict could stimulate innovation and enhance product quality at the firm. Mussallem did not just apply a technique here or there during a few crucial meetings to induce more debate. He did not only stimulate conflict when it came to momentous decisions about the firm’s future. He wanted the concept of “creative debate” to permeate the organization. It became a core value of the firm. Mussallem and Reindl discussed the issue at senior team meetings, invested in leadership development programs on the subject, and surveyed employees to discover whether they felt comfortable disagreeing with superiors. Performance evaluations included an assessment of whether leaders stimulated creative debate within their teams.42 Edwards even created a reminder for all employees in every conference room. Mussallem explained,

We actually have created a small glass piece that we have in all of our conference rooms—that has a little tornado and a heart in the center—that’s the symbol of creative debate for Edwards Lifesciences. It’s a reminder to us that we encourage creative debates—please speak your mind.43

Great organizations and great leaders practice the use of conflict on a regular basis. They exhibit patience and persistence in applying many of the techniques described here. They work diligently to make certain that conflict becomes embedded in the processes and values of the firm. Their experiences demonstrate what Aristotle taught us so many years ago when he said, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

Endnotes

1. The term confrontational by design has been used by Charles Knight, former chairman and CEO of Emerson Electric, to describe the strategic planning process that he created and led for many years at his firm. See C. Knight. (1992). “Emerson Electric: Consistent profits consistently,” Harvard Business Review. 70(1): pp. 57–70.

2. As noted in an earlier chapter, building a more diverse team—one with more demographic heterogeneity—may increase cognitive conflict, though it could spark affective conflict as well. For an example of the empirical research on the link between demographics and cognitive conflict, see D. C. Pearce, K. G. Smith, J. Olian, H. Sims, K. A. Smith, and P. Flood. (1999). “Top management team diversity, group process, and strategic consensus,” Strategic Management Journal. 20: pp. 445–465. One should note, however, that demographic heterogeneity certainly may be helpful, but naturally, it does not guarantee a higher level of cognitive diversity or divergent thinking. In fact, one study showed that group process was a stronger predictor of top management team performance than demographic composition. See K. G. Smith, K. A. Smith, J. Olian, H. Sims, D. O’Bannon, and J. Scully. (1994). “Top management demography and process: The role of social integration and communication,” Administrative Science Quarterly. 39(3): pp. 412–438.

3. Naturally, as mentioned in the preface, leaders also need to take into account the national culture in which they are working. Some would argue that certain principles regarding conflict are not universal; that is, certain national cultures tend to deal with conflict differently, people in some countries tend to be more averse to conflict in group settings, etc. Because I have not conducted a great deal of research in non-Anglo Saxon cultures, I have chosen not to speculate in this book regarding cultural differences. In my view, some cultural differences do exist, although it is not clear to me that the typical stereotypes about certain countries are always accurate. There is certainly a need for more academic research on cultural differences in this area.

4. D. Scott. “Hot off his Manning impersonation, Huard now mimics Delhomme,” The Charlotte Observer. January 24, 2004.

5. M. Reiss, “Ryan Mallett Mimics Peyton Manning.” October 6, 2012. http://espn.go.com/boston/nfl/story/_/id/8467974/ryan-mallett-helping-new-england-patriots-defense-prepare-denver-broncos-mimicking-peyton-manning, accessed January 4, 2012.

6. Eisenhardt and her colleagues also have written about the importance of role-play exercises. See Eisenhardt, Kahwajy, and Bourgeois. (1998).

7. Grove. (1996). p. 89.

8. Grove. (1996). pp. 92–93. For an insightful academic analysis of Intel’s exit from the DRAM business, see R. Burgelman. (1994). “Fading memories: A process theory of strategic business exit in dynamic environments,” Administrative Science Quarterly. 39(1): pp. 24–56. In this work, Burgelman describes how middle managers gradually shifted resources at Intel from the DRAM business to microprocessors, thereby altering the firm’s competitive strategy. During this time, senior management continued to maintain that DRAMs represented a core element of Intel’s corporate strategy; by the time Moore and Grove came to their epiphany, the organization’s strategy had already been altered substantially. They were, in a sense, engaging in post hoc rationalization of the new strategy that had taken hold at lower levels.

9. E. Polman and K. Emich. (2011). “Decisions for others are more creative than decisions for the self,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 37(4): p. 493.

10. E. Polman and K. Emich. (2011). “Decisions for others are more creative than decisions for the self,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 37(4): pp. 492-501.

11. www.creativitypost.com/business/why_thinking_of_others_improves_our_creativity, accessed August 3, 2012.

12. G. Klein. (1999). Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; G. Klein. (2003). Intuition at Work: Why Developing Your Gut Instincts Will Make You Better at What You Do. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

13. P. Wack. (1985). “Scenarios: Uncharted waters ahead,” Harvard Business Review 63(5): pp. 72–79; P. Wack. (1985). “Scenarios: Shooting the rapids,” Harvard Business Review. 63(6): pp. 139–150.

14. Eisenhardt, Kahwajy, and Bourgeois. (1998). p. 163.

15. J. Glawson and L. Grayson. (1996). “Scenario planning,” Darden Business Publishing No. UVA-G-0260.

16. Klein. (2003).

17. R. J. Heuer. (1999). Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. CIA Center for the Study of Intelligence, Langley, VA.

18. www.quora.com/What-is-Amazons-approach-to-product-development-and-product-management, accessed September 18, 2012.

19. www.designthinkingblog.com/?s=unfocus+group, accessed January 4, 2010.

20. M. Roberto. (2001). “Strategic Planning at Sun Life,” Harvard Business School Case No. 301-084.

21. The problem, of course, is that the selection of a particular conceptual lens entails the implicit selection of a frame for the problem at hand. How one frames a problem, of course, drives the type of solutions that are generated and considered. Therefore, scholars often advocate the explicit generation and consideration of multiple frames. See Schoemaker and Russo. (1989).

22. M. Roberto and G. Carioggia. (2003). “Polycom’s Acquisition Process,” Harvard Business School Case No. 304-040.

23. Schweiger, Sandberg, and Ragan. (1986). For more information, see also Garvin and Roberto (1996) and Garvin and Roberto (2001).

24. M. Roberto and G. Carioggia. “Electronic Arts: The Blockbuster Strategy,” Harvard Business School Case No. 304-013.

25. A. George. (1980). George’s comments build on the work of Richard Tanner Johnson, who wrote a book about different presidential decision-making styles. He described Franklin Roosevelt’s style as a “competitive” model of decision making. Johnson contrasted Roosevelt’s approach with the “formalistic” model adopted by presidents such as Eisenhower and Truman. That style emphasized the hierarchical flow of information by well-defined channels and procedures. Subordinates had clearly defined roles and areas of expertise, and the president synthesized the input received from various advisers. Kennedy, in contrast, employed a “collegial” model of decision making. According to Johnson, this approach emphasized a team-oriented approach to problem solving in which a great deal of informal communication occurred. Moreover, advisers behaved more as generalists than as specialists expected only to provide input on matters related to a narrow domain of expertise. The president did not receive information filtered through and synthesized by one Cabinet head or by the chief of staff but rather worked closely with the whole group to hear the debate among his advisers. See Johnson. (1974).

26. J. Thompson, Jr. (1968). “How could Vietnam happen?—An autopsy,” The Atlantic Monthly. 221(4): pp. 47–53. Thompson provides an insightful analysis of the decision making about the conflict in Vietnam, writing with the perspective of having spent five years working in the White House and State Department for Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. For instructors wanting to teach about the Johnson administration’s decision-making processes with regard to the war in Vietnam, I highly recommend asking students to view the movie Path to War, produced by HBO. The film provides an up-close look at how Johnson drew upon the input and counsel of his staff to make important decisions. I have written a brief orientation guide that I ask students to read before watching the movie. The guide provides a bit of background about the conflict, and it provides brief biographies of Johnson and each of his key advisers. See M. Roberto. (2004). “Orientation for Viewing ‘Path to War,’” Harvard Business School Case No. 304-088.

27. Janis. (1982). p. 115.

28. Ibid.

29. Jeffrey Pfeffer has pointed out that agenda control represents an important lever by which managers exert power. Moreover, he notes that some managers may purposefully crowd an agenda so as to avoid an intense focus on a subject about which they do not want lengthy debate. See Pfeffer (1992) and J. Pfeffer (1981). Power in Organizations. Marshfield, MA: Pitman Publishing.

30. The adoption of a production, or routine operational, frame provides a powerful explanation of the organization’s behavior during the Columbia recovery window (Deal, 2004). That framing partially explains why NASA emphasized schedules and deadlines as much as it did. Moreover, it contributes to our understanding of why Mission Management Team meetings were run in a very regimented, orderly, and efficient manner; after all, in a routine production environment, meetings are typically conducted in that manner. In short, Ham led the meeting in a manner consistent with the “operational frame” in which the shuttle program was organized. Her behavior is partially a product of the context in which she worked. That argument fits with Vaughan’s analysis of the organization; as she said, “This was no personality problem. This was a structural and a cultural problem. And if you just change the cast of characters, the next person who comes in is going to be met with the same structure, the same culture, and they’re going to be impelled to act in the same way.” Vaughan interview (2004). For a lengthier discussion of the impact of the operational framing of the shuttle program, see Edmondson, Roberto, Bohmer, Ferlins, and Feldman. (2005).

31. Deal. (2004).

32. My colleague David Garvin has often pointed out that the subgroups in the Cuban missile crisis spent only a few days together, not many weeks or months. The limited time frame may explain, in part, why people did not become so wedded to their subgroup positions as to induce a great deal of affective conflict and/or impede implementation of the final decision.

33. Lengthy time spent in subgroups may induce and accelerate social categorization processes, in which individuals may adopt highly positive perceptions about their in-group (their own subgroup) and negative perceptions about their out-group (the other subgroup). As Polzer and his colleagues have noted, such categorization activity can have a detrimental effect on team communication, conflict management, and performance. See Polzer, Milton, and Swann. (2002).

34. Minson, J., Mueller, J. (2012). The cost of collaboration: Why joint decision-making exacerbates the rejection of outside information. Psychological Science, 23(3), 214-219.

35. Langley. (1989).

36. M. Roberto and G. Carioggia. (2003). “Polycom’s Acquisition Process,” Harvard Business School Case No. 304-040.

37. A related problem in acquisition decision making concerns the effects of momentum. Scholars Philippe Haspeslagh and David Jemison have described how many acquisition decision processes take on a “life of their own.” In that atmosphere, it becomes difficult to question the strategic logic of a deal that appears destined to be completed, and for which all debates seem only about the fine points of the quantitative analysis. See P. Haspeslagh and D. Jemison. (1991). Managing Acquisitions: Creating Value Through Corporate Renewal. New York: Free Press.

38. D. Schweiger, W. Sandberg, and P. Rechner. (1989). “Experimental effects of dialectical inquiry, devil’s advocacy, and consensus approaches to strategic decision making,” Academy of Management Journal. 32: pp. 745–772.

39. Bower and Dial. (1994). p. 4.

40. Welch. (2001).

41. Knight. (1992).

42. Interview with Rob Reindl, December 7, 2006.

43. G. Hall. “Edwards’ Mussallem Sees Success in Failure.” May 24, 2007. www.ocregister.com/articles/people-8747-fail-mussallem.html, accessed November 4, 2012.